Submitted:

14 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Qualitative Assays of HBV Serological Markers

2.3. Quantitative Assays of Anti-HBs and HBsAg

2.4. Measurement of Serum Viral Loads

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Study Subjects

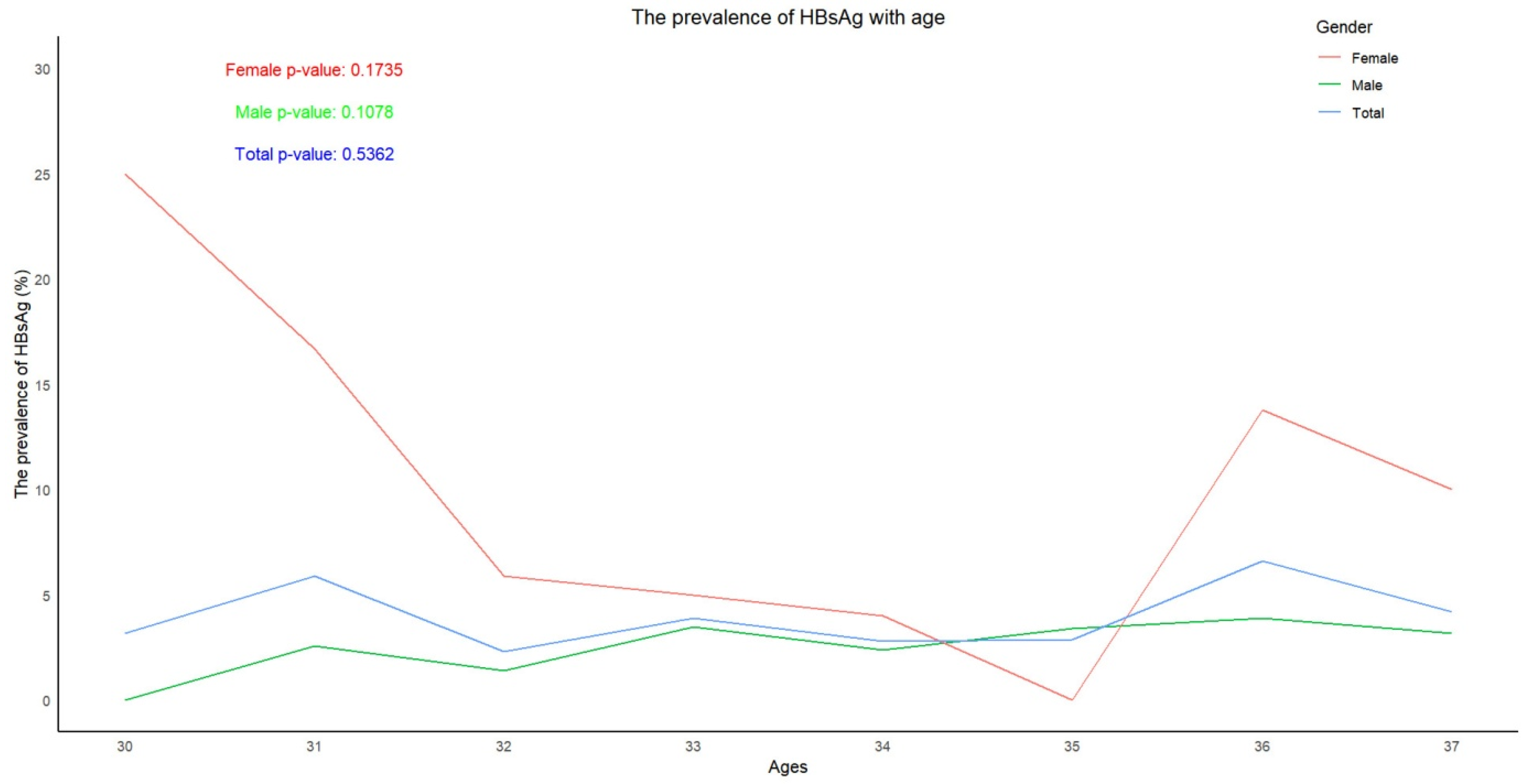

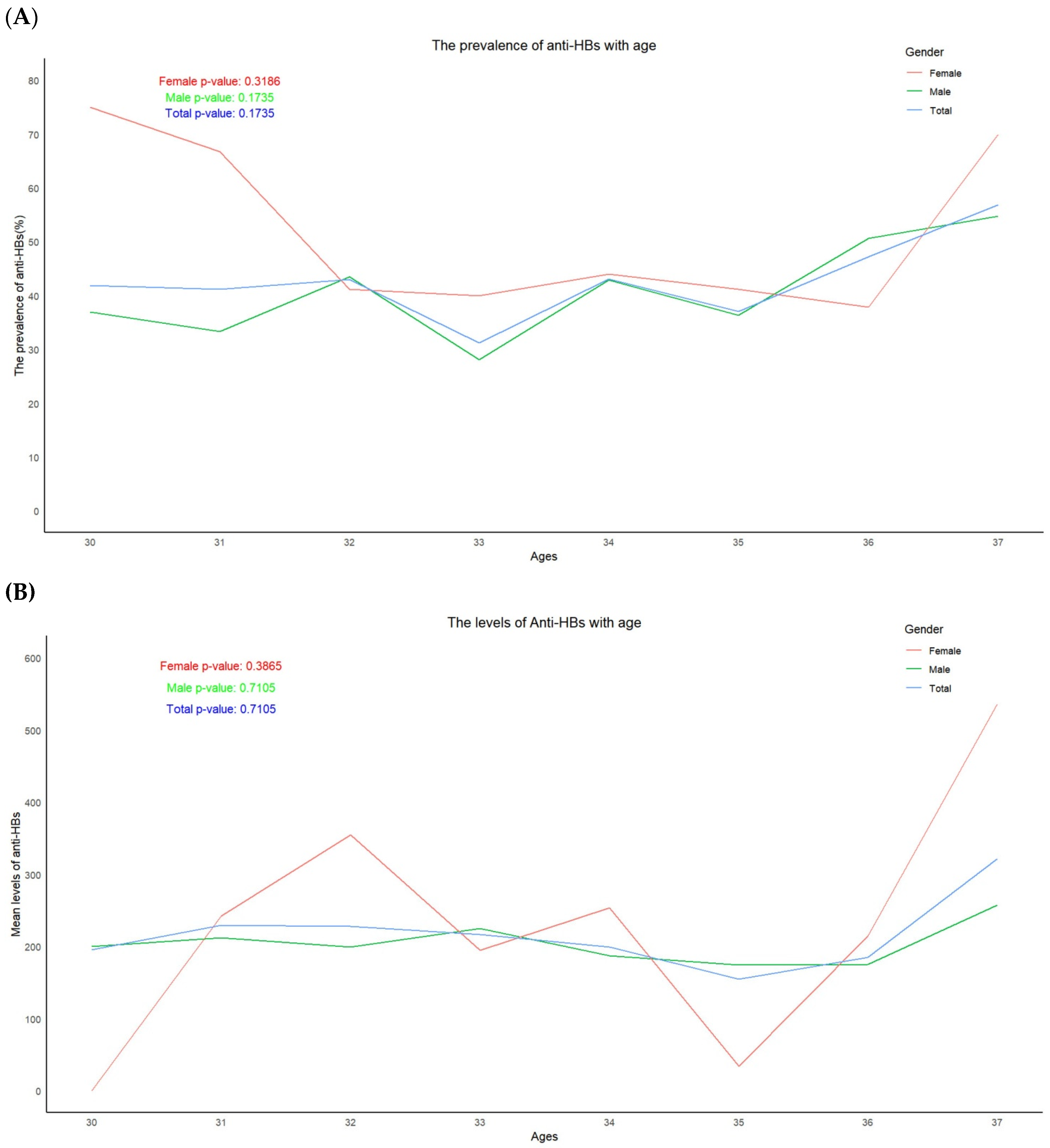

3.2. Trend in the Prevalence of HBsAg and the Positive Rates and Levels of Anti-HBs, According to Age

3.3. Trend in the Prevalence of Anti-HBc According to Age

3.4. Characteristics of Subjects Positive for HBeAg

3.5. Comparison of the Prevalence of HBsAg, Anti-HBs and Anti-HBc from the Same Subject, Previously and Currently (2024)

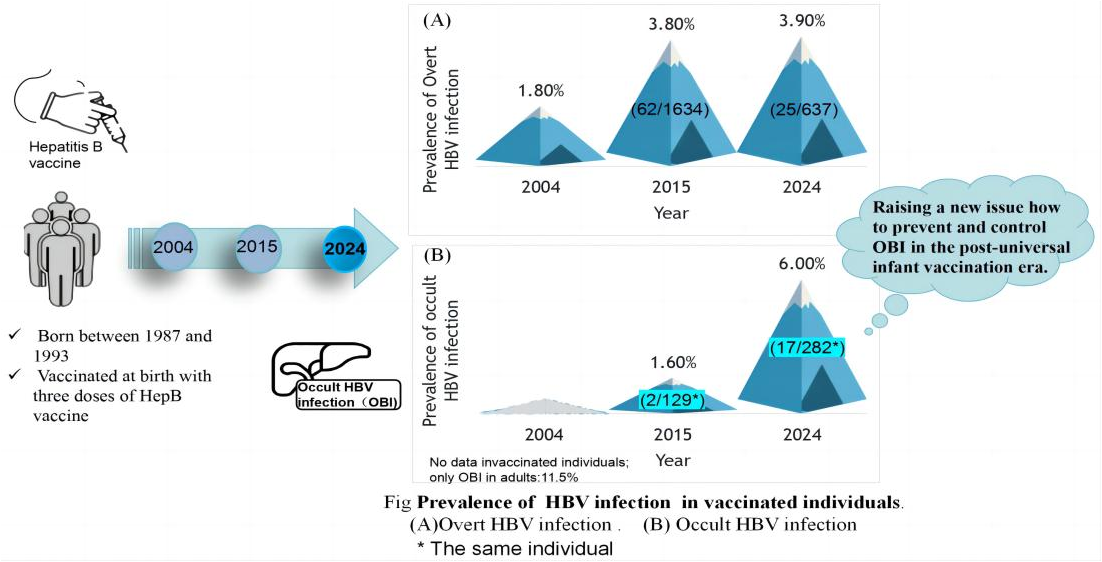

3.6. Comparison of Occult Infection Between Subjects Recruited in 2017 and 2024

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boora S.; Sharma V.; Kaushik S.; Bhupatiraju AV.; Singh S.; Kaushik S. Hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma: a persistent global problem. Braz J Microbiol. 2023, 54, 679–689. [CrossRef]

- Patel A.; Dossaji Z.; Gupta K.; Roma K.; Chandler T-M.; Minacapelli CD.; Catalano K.; Gish R.; Rustgi V. The Epidemiology, Transmission, Genotypes, Replication, Serologic and Nucleic Acid Testing, Immunotolerance, and Reactivation of Hepatitis B Virus. Gastro Hep Adv. 2023, 3, 139–150. [CrossRef]

- Hepatitis B Fact Sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/.2021,.

- Hsu Y-C.; Huang DQ.; Nguyen MH. Global burden of hepatitis B virus: current status, missed opportunities and a call for action. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023, 20, 524–537. [CrossRef]

- Zhao H.; Zhou X.; Zhou Y-H. Hepatitis B vaccine development and implementation. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020, 16, 1533–1544. [CrossRef]

- Davis JP. Experience with hepatitis A and B vaccines. Am J Med. 2005, 118 Suppl 10A, 7S-15S. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Implementation of newborn hepatitis B vaccination--worldwide, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008, 57, 1249–1252.

- Scheifele DW. Will Infant Hepatitis B Immunization Protect Adults? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019, 38, S64–S66. [CrossRef]

- Boccalini S.; Bonito B.; Zanella B.; Liedl D.; Bonanni P.; Bechini A. The First 30 Years of the Universal Hepatitis-B Vaccination-Program in Italy: A Health Strategy with a Relevant and Favorable Economic-Profile. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 16365. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y.; Liu L. Changes in the Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Asia. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14, 4473. [CrossRef]

- Phattraprayoon N.; Kakheaw J.; Soonklang K.; Cheirsilpa K.; Ungtrakul T.; Auewarakul C.; Mahanonda N. Duration of Hepatitis B Vaccine-Induced Protection among Medical Students and Healthcare Workers following Primary Vaccination in Infancy and Rate of Immunity Decline. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10, 267. [CrossRef]

- Wu J.; He J.; Xu H. Global prevalence of occult HBV infection in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Hepatol. 2024, 29, 101158. [CrossRef]

- Hsu H-Y.; Chang M-H.; Ni Y-H.; Chiang C-L.; Wu J-F.; Chen H-L.; Chen P-J.; Chen D-S. Chronologic changes in serum hepatitis B virus DNA, genotypes, surface antigen mutants and reverse transcriptase mutants during 25-year nationwide immunization in Taiwan. J Viral Hepat. 2017, 24, 645–653. [CrossRef]

- Zhou S.; Li T.; Allain J-P.; Zhou B.; Zhang Y.; Zhong M.; Fu Y.; Li C. Low occurrence of HBsAg but high frequency of transient occult HBV infection in vaccinated and HBIG-administered infants born to HBsAg positive mothers. J Med Virol. 2017, 89, 2130–2137. [CrossRef]

- Eilard A.; Andersson M.; Ringlander J.; Wejstål R.; Norkrans G.; Lindh M. Vertically acquired occult hepatitis B virus infection may become overt after several years. J Infect. 2019, 78, 226–231. [CrossRef]

- Mak L-Y.; Wong DK-H.; Pollicino T.; Raimondo G.; Hollinger FB.; Yuen M-F. Occult hepatitis B infection and hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology, virology, hepatocarcinogenesis and clinical significance. J Hepatol. 2020, 73, 952–964. [CrossRef]

- Xia R.; Peng J.; He J.; Jiang P.; Yuan C.; Liu X.; Yao Y. The Serious Challenge of Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma in China. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 840825. [CrossRef]

- Ding ZR. Distribution of viral hepatitis B infection in Guangsi Province. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 1982, 3, 84–87.

- Wang F.; Shen L.; Cui F.; Zhang S.; Zheng H.; Zhang Y.; Liang X.; Wang F.; Bi S. The long-term efficacy, 13-23 years, of a plasma-derived hepatitis B vaccine in highly endemic areas in China. Vaccine. 2015, 33, 2704–2709. [CrossRef]

- Li H.; Li GJ.; Chen QY.; Fang ZL.; Wang XY.; Tan C.; Yang QL.; Wang FZ.; Wang F.; Zhang S.; et al. Long-term effectiveness of plasma-derived hepatitis B vaccine 22-28 years after immunization in a hepatitis B virus endemic rural area: is an adult booster dose needed? Epidemiol Infect. 2017, 145, 887–894. [CrossRef]

- Wang X.; Chen Q.; Li H.; Wang C.; Hu L.; Yang Q.; Ren C.; Liu H.; Zheng Z.; Harrison TJ.; et al. Asymptomatic hepatitis B carriers who were vaccinated at birth. J Med Virol. 2019, 91, 1489–1498. [CrossRef]

- Asamoah Sakyi S.; Badu Gyapong J.; Krampah Aidoo E.; Effah A.; Koffie S.; Simon Olympio Mensah O.; Arddey I.; Boakye G.; Opoku S.; Amoani B.; et al. Evaluation of Immune Characteristics and Factors Associated with Immune Response following Hepatitis B Vaccination among Ghanaian Adolescents. Adv Virol. 2024, 2024, 9502939. [CrossRef]

- Miao N.; Zheng H.; Sun X.; Zhang G.; Wang F. Protective effect of vaccinating infants with a 5 µg recombinant yeast-derived hepatitis B vaccine and the need for a booster dose in China. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 18155. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi FP.; Gallone MS.; Gallone MF.; Larocca AMV.; Vimercati L.; Quarto M.; Tafuri S. HBV seroprevalence after 25 years of universal mass vaccination and management of non-responders to the anti-Hepatitis B vaccine: An Italian study among medical students. J Viral Hepat. 2019, 26, 136–144. [CrossRef]

- Bruce MG.; Bruden D.; Hurlburt D.; Morris J.; Bressler S.; Thompson G.; Lecy D.; Rudolph K.; Bulkow L.; Hennessy T.; et al. Protection and antibody levels 35 years after primary series with hepatitis B vaccine and response to a booster dose. Hepatology. 2022, 76, 1180–1189. [CrossRef]

- Wang R.; Liu C.; Chen T.; Wang Y.; Fan C.; Lu L.; Lu F.; Qu C. Neonatal hepatitis B vaccination protects mature adults from occult virus infection. Hepatol Int. 2021, 15, 328–337. [CrossRef]

- Xu L.; Wei Y.; Chen T.; Lu J.; Zhu C-L.; Ni Z.; Huang F.; Du J.; Sun Z.; Qu C. Occult HBV infection in anti-HBs-positive young adults after neonatal HB vaccination. Vaccine. 2010, 28, 5986–5992. [CrossRef]

- Lu Y.; Liu Y-L.; Nie J-J.; Liang X-F.; Yan L.; Wang F-Z.; Zhai X-J.; Liu J-X.; Zhu F-C.; Chang Z-J.; et al. Occult HBV Infection in Immunized Neonates Born to HBsAg-Positive Mothers: A Prospective and Follow-Up Study. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0166317. [CrossRef]

- Foaud H.; Maklad S.; Mahmoud F.; El-Karaksy H. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in children born to HBsAg-positive mothers after neonatal passive-active immunoprophylaxis. Infection. 2015, 43, 307–314. [CrossRef]

- Pondé RAA. Molecular mechanisms underlying HBsAg negativity in occult HBV infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015, 34, 1709–1731. [CrossRef]

- Fang Z-L.; Zhuang H.; Wang X-Y.; Ge X-M.; Harrison T-J. Hepatitis B virus genotypes, phylogeny and occult infection in a region with a high incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 3264–3268. [CrossRef]

- Pollicino T.; Raffa G.; Costantino L.; Lisa A.; Campello C.; Squadrito G.; Levrero M.; Raimondo G. Molecular and functional analysis of occult hepatitis B virus isolates from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007, 45, 277–285. [CrossRef]

- Liu B.; Yang H.; Liao Q.; Wang M.; Huang J.; Xu R.; Shan Z.; Zhong H.; Li T.; Li C.; et al. Altered gut microbiota is associated with the formation of occult hepatitis B virus infection. Microbiol Spectr. 2024, 12, e0023924. [CrossRef]

- Hu L-P.; Liu D-P.; Chen Q-Y.; Harrison TJ.; He X.; Wang X-Y.; Li H.; Tan C.; Yang Q-L.; Li K-W.; et al. Occult HBV Infection May Be Transmitted through Close Contact and Manifest as an Overt Infection. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0138552. [CrossRef]

- Yip TC-F.; Wong GL-H. Current Knowledge of Occult Hepatitis B Infection and Clinical Implications. Semin Liver Dis. 2019, 39, 249–260. [CrossRef]

- Gerlich WH.; Bremer C.; Saniewski M.; Schüttler CG.; Wend UC.; Willems WR.; Glebe D. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: detection and significance. Dig Dis. 2010, 28, 116–125. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q.; Klenerman P.; Semmo N. Significance of anti-HBc alone serological status in clinical practice. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017, 2, 123–134. [CrossRef]

- Kramvis A. The clinical implications of hepatitis B virus genotypes and HBeAg in pediatrics. Rev Med Virol. 2016, 26, 285–303. [CrossRef]

- Chen P.; Xie Q.; Lu X.; Yu C.; Xu K.; Ruan B.; Cao H.; Gao H.; Li L. Serum HBeAg and HBV DNA levels are not always proportional and only high levels of HBeAg most likely correlate with high levels of HBV DNA: A community-based study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017, 96, e7766. [CrossRef]

- Lai M-W.; Chang Y-L.; Cheng P-J.; Chueh H-Y.; Chang S-C.; Yeh C-T. Absence of chronicity in infants born to immunized mothers with occult HBV infection in Taiwan. J Hepatol. 2022, 77, 63–70. [CrossRef]

| Groups | Males | Females | Total | ||||||

| No | Positive | Rate (%) (95% CI△) |

No | Positive | Rate (%) (95% CI) |

No | Positive | Rate (%) (95% CI) |

|

| HBsAg | 503 | 14 | 2.8 (1.5-4.1) |

134 | 11 | 8.2 (6.1-10.3) |

637 | 25 | 3.9 (2.4-5.4) |

| Anti-HBs | 503 | 210 | 41.7 (37.9-45.5) |

134 | 62 | 46.3 (42.4-50.2) |

637 | 272 | 42.7 (38.9-46.5) |

| Anti-HBc | 503 | 207 | 41.2 (36.9-45.5) |

134 | 70 | 52.2 (43.7-60.7) |

637 | 277 | 43.5 (39.7-47.3) |

| Levels of Anti-HBs | Mean*± SD# | Mean ±SD | Mean ±SD | ||||||

| 200.9±323.2§ | 266.8±353.2 | 215.5±330.4 | |||||||

| Codes | Gender | Ages | HBsAg | anti-HBs | HBeAg | anti-HBe | anti-HBc | Viral loads |

| AWL120 | M* | 33 | - | 16.428 | + | - | - | Undetectable |

| AWB133 | F# | 32 | - | - | + | - | - | Undetectable |

| ATZ196 | M | 33 | - | - | + | - | - | Undetectable |

| ATX297 | M | 34 | - | 334.995 | + | - | + | Undetectable |

| ATX289 | M | 35 | - | - | + | - | - | Undetectable |

| ATX261 | F | 33 | - | - | + | - | - | Undetectable |

| ATW230 | M | 34 | - | 190.843 | + | - | - | Undetectable |

| ATT524 | M | 37 | - | >1000.000§ | + | - | - | Undetectable |

| ATM174 | M | 33 | - | >1000.000 | + | - | + | Undetectable |

| ATL181 | M | 31 | - | - | + | - | - | 80.009△ |

| ATL143 | M | 31 | - | 78.288 | + | - | + | Undetectable |

| ATF074 | M | 32 | - | 98.957 | + | - | + | Undetectable |

| AQT182 | M | 35 | - | >1000.000 | + | - | - | Undetectable |

| APP045 | M | 35 | - | - | + | - | - | Undetectable |

| ACS020 | M | 31 | - | 482.039 | + | - | - | Undetectable |

| 09LA1043 | M | 34 | - | 35.529 | + | - | + | Undetectable |

| 09LA0167 | M | 34 | - | >1000.000 | + | - | - | Undetectable |

| Marker | No | Status (positive or negative) unchanged | Became positive | Became negative | |||

| No | Rate (%) (95% CI*) |

No | Rate (%) (95% CI) |

No | Rate (%) (95% CI) |

||

| HBsAg | 637 | 630 | 98.9 (98.1-99.7) |

1 | 0.2 (-0.1-0.5) |

6 | 0.9 (0.1-1.6) |

| Anti-HBs | 637 | 576 | 90.4 (88.1-92.7) |

26 | 4.1 (2.6-5.6) |

35 | 5.5 (3.7-7.3) |

| Anti-HBc | 637 | 454 | 71.3 (67.8-74.8) |

157 | 24.6 (21.3-27.9) |

26 | 4.1 (2.6-5.6) |

| Groups | No | Positive | Rate (%) | 95% CI* |

| 2024 | ||||

| Negative for all serological markers | 62 | 1 | 1.6 | -1.5-4.7 |

| anti-HBc(+) only | 89 | 7 | 7.9 | 2.3-13.5 |

| anti-HBc(+) with anti-HBs(+) or anti-HBe(+) or HBeAg(+) |

104 | 7 | 6.7 | 1.9-11.5 |

| anti-HBc(-) with anti-HBs(+) or anti-HBe(+) or HBeAg(+) |

27 | 2 | 7.4 | -2.5-17.3 |

| Total | 282 | 17 | 6.0 | 3.2-8.8 |

| 2015 | ||||

| Negative for all serological markers | 53 | 1 | 1.9 | -1.8-5.6 |

| anti-HBc(+) only | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| anti-HBs(+), anti-HBc(+) | 29 | 1 | 3.4 | -3.2-10.0 |

| Total | 129 | 2 | 1.6 | -0.6-3.8 |

| Code | Gender | Ages | HBsAg | anti-HBs | HBeAg | anti-HBe | anti-HBc |

HBV DNA (IU/ml) |

| 09LA1051 | M△ | 34 | - | 248.835§ | - | - | + | 157.965§ |

| 09LA1073 | F# | 32 | - | - | - | - | + | 102.424 |

| 09LA3607 | M | 34 | - | - | - | - | + | 253.2 |

| ADH140* | F | 33 | - | - | - | - | - | 41192.4 |

| ADH140 | F | 33 | - | - | - | - | - | 267.372 |

| ADJ006 | F | 36 | - | 243.483 | - | - | + | 1842.646 |

| ADJ102 | M | 32 | - | - | - | - | + | 223.013 |

| ADK129 | M | 37 | - | 435.870 | - | + | + | 49.213 |

| ADK130 | M | 37 | - | - | - | + | - | 447.401 |

| AGM067 | F | 33 | - | - | - | - | + | 180.14 |

| AGM098 | M | 35 | - | - | - | - | + | 307.819 |

| AGM212 | M | 36 | - | 337.604 | - | - | + | 436.139 |

| AGZ078 | M | 36 | - | - | - | - | + | 108.223 |

| ATJ035 | M | 32 | - | 944.213 | - | - | + | 263.29 |

| ATL181 | M | 31 | - | - | + | - | - | 80.009 |

| ATW293 | M | 36 | - | - | - | - | + | 695.963 |

| ATW295* | M | 32 | - | + | - | - | + | 96.331 |

| ATW295 | M | 33 | - | 269.656 | - | - | + | 212.238 |

| ATZ238 | M | 37 | - | 595.325 | - | - | + | 65.842 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).