Submitted:

14 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Background and Petrology

3. Analytical Methods

3.1. REE-Bearing Minerals

3.2. Zircon U-Pb Dating

3.3. Whole-Rock Major and Trace Element Analyses

3.4. Whole-Rock Sr-Nd Isotopic Analyses

3.5. Zircon Hf isotopic Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of REE-Bearing Minerals

4.2. Zircon U-Pb Dating Results

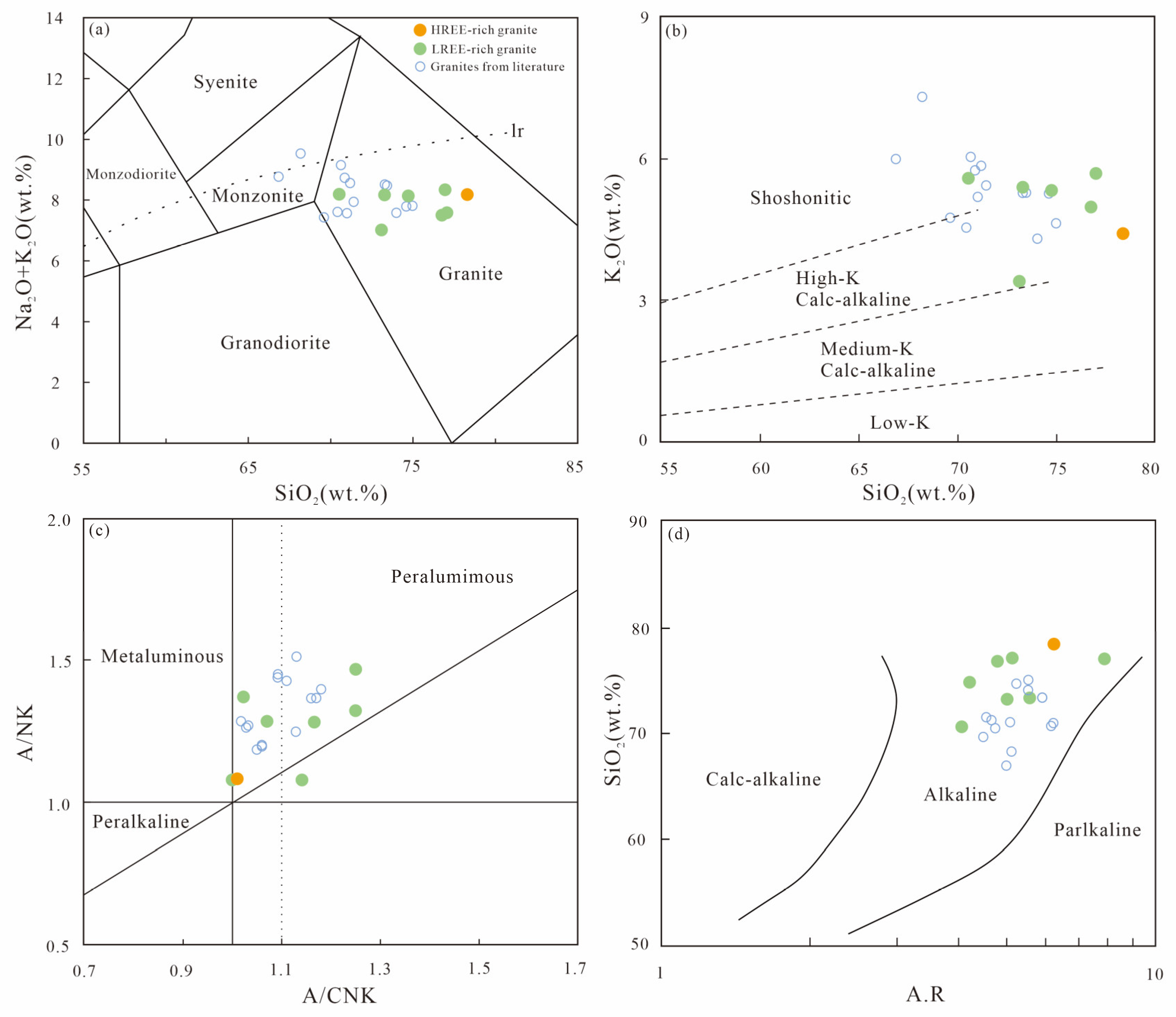

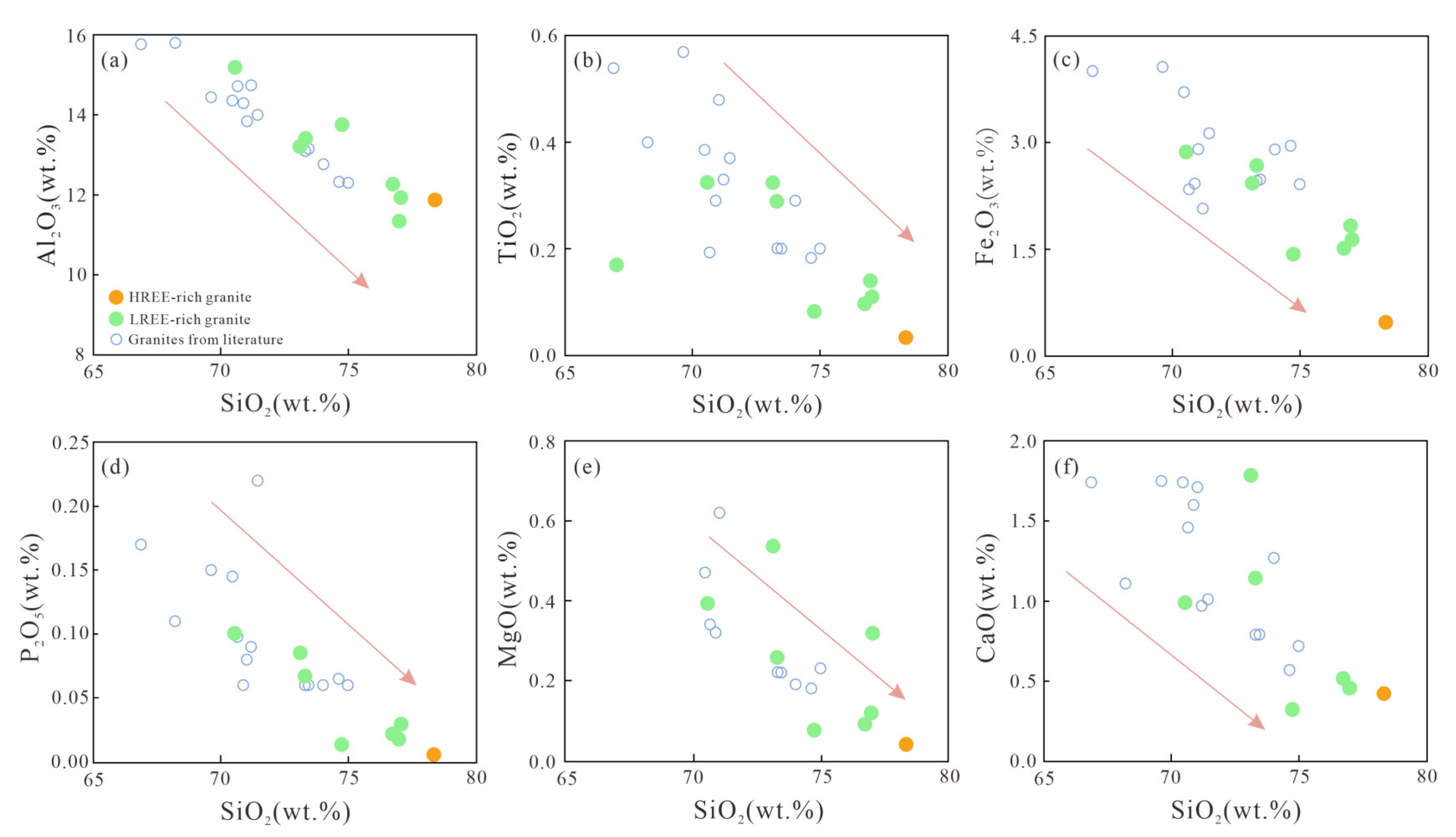

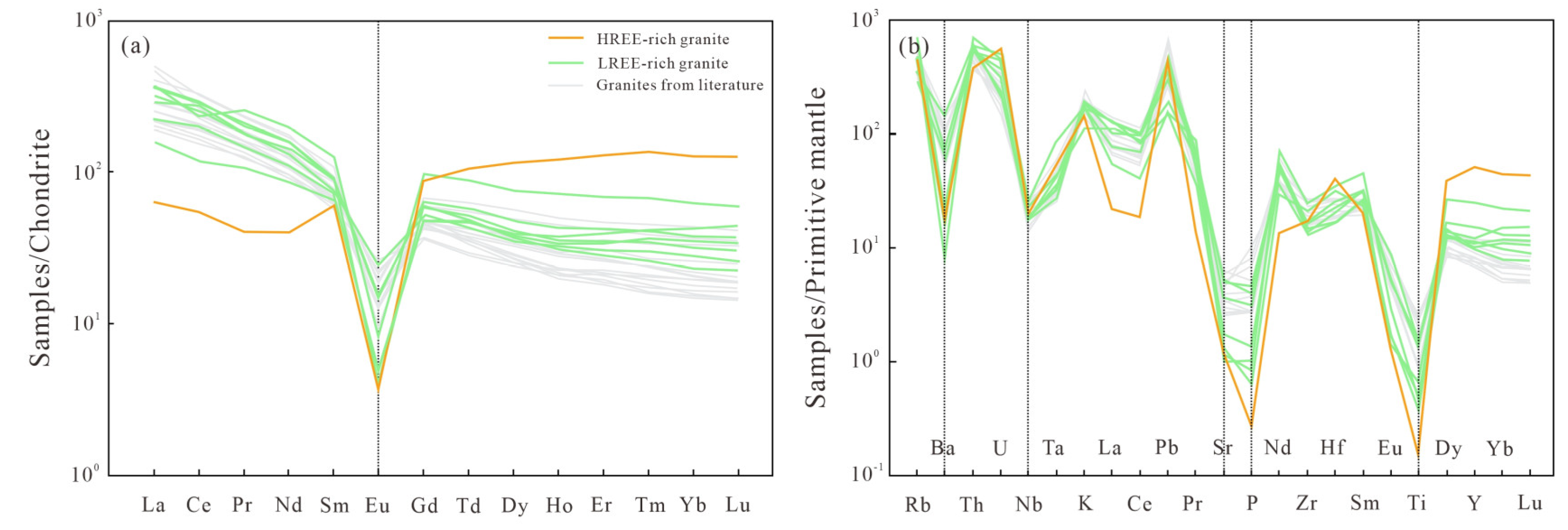

4.3. Whole-Rock Major- and Trace Element and REE Compositions

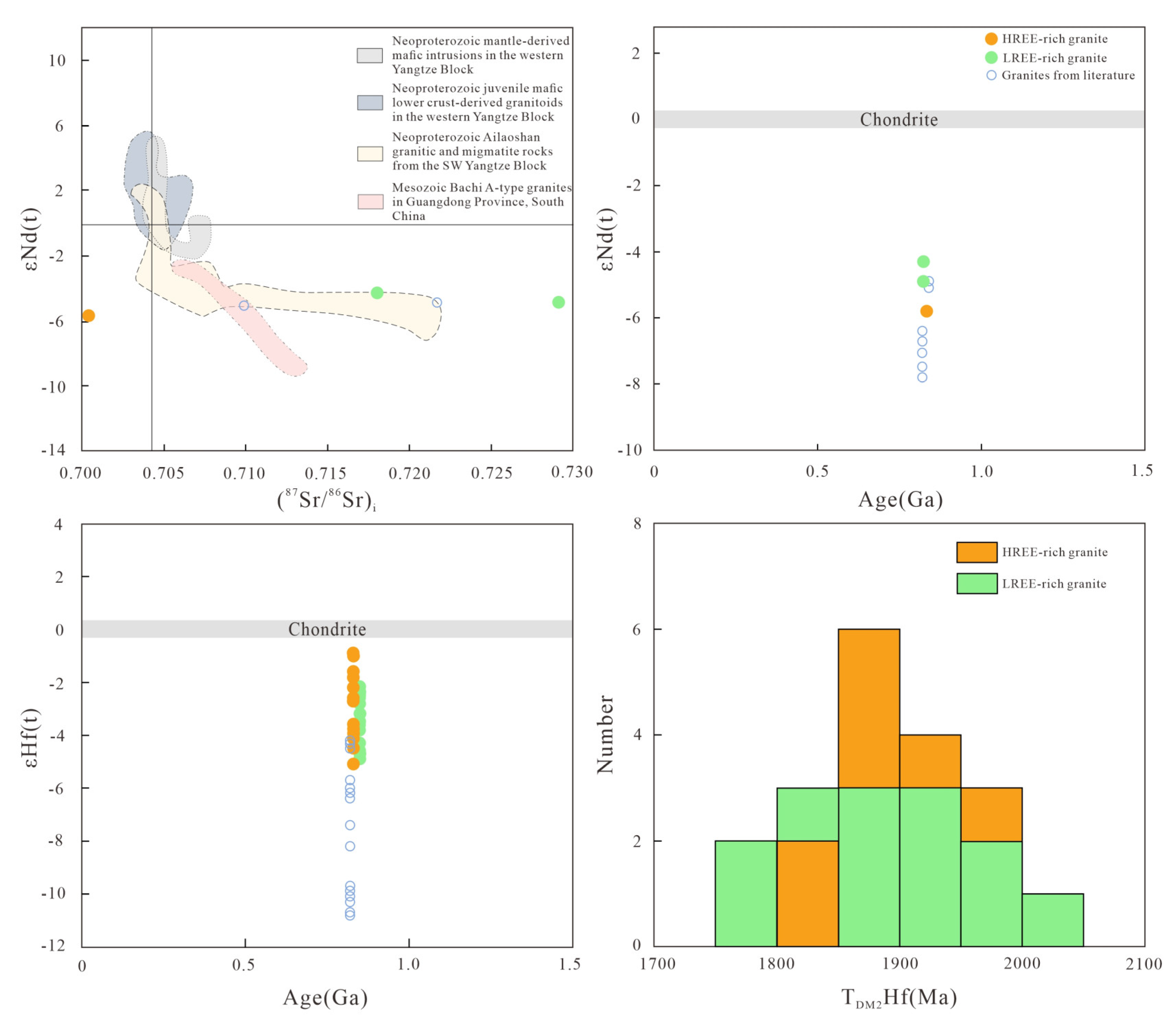

4.4. Whole-Rock Sr-Nd Isotopic Results

4.5. Zircon Hf Isotopic Results

5. Discussion

5.1. REE Enrichment in the Mosuoying Granites

5.2. Metallogenetic Process of REE in the Parent Rock

5.2.1. Genetic Type

5.2.2. Petrogenesis and REE Origin

5.2.3. Formation Process of REE-Rich Granites

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balaram, V. Rare earth elements: A review of applications, occurrence, exploration, analysis, recycling, and environmental impact. Geoscience Frontiers 2019, 10, 1285–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Hecai, N.; Xiaochun, L.; Kuifeng, Y.; Zhanfeng, Y.; Qiwei, W. The types, ore genesis and resource perspective of endogenic ree deposits in china. Chinese Science Bulletin 2020, 65, 3778–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampides, G.; Vatalis, K.I.; Apostoplos, B.; Ploutarch-Nikolas, B. Rare earth elements: Industrial applications and economic dependency of europe. Procedia Economics and Finance 2015, 24, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simandl, G.J. Geology and market-dependent significance of rare earth element resources. Mineralium Deposita 2014, 49, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kynicky, J.; Smith, M.P.; Xu, C. Diversity of rare earth deposits: The key example of china. Elements 2012, 8, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Zhao, Z. Geochemistry of mineralization with exchangeable rey in the weathering crusts of granitic rocks in south china. Ore Geology Reviews 2008, 33, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.M.; Zhao, W.W.; Zhou, M.F. Nature of parent rocks, mineralization styles and ore genesis of regolith-hosted ree deposits in south china: An integrated genetic model. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2017, 148, 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Li, N.B.; Jiang, Y.H.; Zhao, X. Geochemical differences of parent rocks for ion-adsorption lree and hree deposits: A case study of the guanxi and dabu granite plutons. Geotectonica et Metallogenia 2024, 48, 232–247. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Li, N.B.; Huizenga, J.M.; Yan, S.; Yang, Y.Y.; Niu, H.C. Rare earth element enrichment in the ion-adsorption deposits associated granites at mesozoic extensional tectonic setting in south china. Ore Geology Reviews 2021, 137, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, N.B.; Marten Huizenga, J.; Zhang, Q.B.; Yang, Y.Y.; Yan, S.; Yang, W.b.; Niu, H.C. Granitic magma evolution to magmatic-hydrothermal processes vital to the generation of hrees ion-adsorption deposits: Constraints from zircon texture, u-pb geochronology, and geochemistry. Ore Geology Reviews 146, 104931. [CrossRef]

- Sanematsu, K.; Watanabe, Y. Characteristics and genesis of ion adsorption-type rare earth element deposits. In Rare Earth and Critical Elements in Ore Deposits, Society of Economic Geologists: Rev. Econ. Geol, 2016; Vol. 18, pp 55-79.

- Zhao, X.; Li, N.B.; Niu, H.C.; Jiang, Y.H.; Yan, S.; Yang, Y.Y.; Fu, R.X. Hydrothermal alteration of allanite promotes the generation of ion-adsorption lree deposits in south china. Ore Geology Reviews 2023, 155, 105377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, N.B.; Niu, H.C.; Wang, J.; Yan, S.; Yang, Y.Y.; Fu, R.X.; Huizenga, J.M. Hree enrichment during magmatic evolution recorded by apatite: Implication for the ion-adsorption hree mineralization in south china. Lithos 2022, 432-433, 106896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Xu, C.; Shi, A.; Smith, M.P.; Kynicky, J.; Wei, C. Origin of heavy rare earth elements in highly fractionated peraluminous granites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2023, 343, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Kynický, J.; Smith, M.P.; Kopriva, A.; Brtnický, M.; Urubek, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; He, C.; Song, W. Origin of heavy rare earth mineralization in south china. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 14598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.Z.; Wang, Y.; Tan, W.; Song, Z.Z. Mechanism of ree enrichment in granitic bedrocks of the ion-adsorption ree deposits in the nanling mountain range, south china. Geotectonica et Metallogenia 2024, 48, 200–212. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, D.; Bagas, L.; Chen, Z. Geochemical and ree mineralogical characteristics of the zhaibei granite in jiangxi province, southern china, and a model for the genesis of ion-adsorption ree deposits. Ore Geology Reviews 2022, 140, 104579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.H.; Liu, T.Q.; Yin, C.; Yang, W.; Tan, H.Q.; Zhou, J.Y.; Wang, C.H. First discovery of ion adsorption-type (medium—heavy) ree depositin the panzhihua—xichang area, sichuan province, and its significance. Geological Review 2022, 68, 1540–1543. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J.Z.; Fei, N.; Guo, J.C. New discovery of ion-absorption type ree mineral occurrence in the mianning-dechang area, sichuan province. Geology in China 2023, 50, 648–649. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.H.; Liu, T.Q.; Yin, C.; Duan, L.; Yang, W.; Wang, C.; Li, N.; Wang, C.H.; Tan, H.Q. Geological characteristics and metallogenic factors of the kuanyu ion adsorption-type ree deposit in the panzhihua-xichang district, sichuan, sw china and its prospecting potential. Geology in China 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.L.; Wang, D.H.; Chen, Y.C.; Zhao, Z.G.; Wang, Y.B.; Fu, X.F.; Fu, D.M. Shrimp u-pb zircon ages and major element, trace element and nd-sr isotope geochemical studies of a neoproterozoic granitic complex in western sichuan: Petrogenesis and tectonic significance. Acta Petrologica Sinica 2007, 2457–2470. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.B.; Shi, C.L.; Liu, P.W.; Liu, Y.X.; Ding, X.Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.M.; Qian, B. Neoproterozoic slab window in the western yangtze block, south china: Evidence from adakitic granodiorites, gabbro-diorites and high-k granites in the panxi arc belt. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2024, 259, 105859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Lai, S.C.; Qin, J.F.; Zhu, R.Z.; Zhang, F.Y.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Zhao, S.W. Neoproterozoic peraluminous granites in the western margin of the yangtze block, south china: Implications for the reworking of mature continental crust. Precambrian Research 333, 105443. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Q.; Ren, J.S.; Jiang, C.F.; Zhang, Z.M.; Xu, Z.Q. An outline of the tectonic characteristics of china. Acta Geologica Sinica 1977, 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Z.; Tian, S.; Xie, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Yin, S.; Yi, L.; Fei, H.; Zou, T.; Bai, G. , et al. The himalayan mianning–dechang ree belt associated with carbonatite–alkaline complexes, eastern indo-asian collision zone, sw china. Ore Geology Reviews 2009, 36, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Yan, B.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yin, C.; Zhu, L.; Tan, S.; Ding, D.; Jiang, H. Geochemical and mineralogical characteristics of ion-adsorption type ree mineralization in the mosuoying granite, panxi area, southwest china. Minerals 2023, 13, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabi, A.W.; Yang, Z.X.; Zhang, M.C.; Wen, D.K.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, X.Y. Two types of granites in the western yangtze block and their implications for regional tectonic evolution: Constraints from geochemistry and isotopic data. Acta Geologica Sinica(English Edition) 2018, 92, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sláma, J.; Košler, J.; Condon, D.J.; Crowley, J.L.; Gerdes, A.; Hanchar, J.M.; Horstwood, M.S.A.; Morris, G.A.; Nasdala, L.; Norberg, N. , et al. Plešovice zircon — a new natural reference material for u–pb and hf isotopic microanalysis. Chemical Geology 2008, 249, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.R. Isoplot 3.00: A geochronological toolkit for microsoft excel: Berkeley geochronology center. Special Publication 2003, No. 4.

- Hoskin, P.W.O.; Schaltegger, U. The composition of zircon and igneous and metamorphic petrogenesis. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 2003, 53, 27–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.X.; Yuan, W.M. Zircon characteristics of different genetic types and their geochronological significance. China Mining Magazine 2021, 30, 204–207. [Google Scholar]

- Rubatto, D.; Gebauer, D. Use of cathodoluminescence for u-pb zircon dating by ion microprobe: Some examples from the western alps. Cathodoluminescence in Geosciences 2000, 373–400. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherill, G.W. Discordant uranium-lead ages, i Transactions, American Geophysical Union 1956, Vol.37, 320-326.

- Middlemost, E.A.K. Naming materials in the magma/igneous rock system. Earth-Science Reviews 1994, 37, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccerillo, A.; Taylor, S.R. Geochemistry of eocene calc-alkaline volcanic rocks from the kastamonu area, northern turkey. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1976, 58, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniar, P.D.; Piccoli, P.M. Tectonic discrimination of granitoids. GSA Bulletin 1989, 101, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.B. A simple alkalinity ratio and its application to questions of non-orogenic granite genesis. Geological Magazine 1969, 106, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun; Publications, M.J.G.S.L.S. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: Implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol. Soc., London, Spec. Publ. 1989, 42.

- Bai, G.; Wu, C.Y.; Ding, X.S.; Yuan, Z.X.; Huang, D.H.; Huang, P.H. Genesis and spatial distribution of ion-adsorption type ree deposit in nanling region. Institute of Ore Deposit Geology, Beijing, p, 1989; Vol. 105.

- Lu, L.; Wang, D.H.; Wang, C.H.; Zhao, Z.; Feng, W.J.; Xu, X.C.; Chen, C.; Zhong, H.R. The metallogenic regularity of ion-adsorption type ree deposit in yunnan province. Acta Geologica Sinica 2020, 94, 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Z.W.; Lu, Y.X.; Luo, J.H.; Tang, Z.; Yu, H.J.; Su, X.Y.; Yang, Q.B.; Fu, H. Ree distribution characteristics of the yingpanshan ion adsorption type rare-earth deposit in the longchuan area of western yunnan. Geology and Exploration 2021, 57, 784–795. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, D.H.; Chen, Z.H.; Chen, Z.Y. Progress of research on metallogenic regularity of ion-adsorption type ree deposit in the nanling range. Acta Geologica Sinica 2017, 91, 2814–2827. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.M. Using rare earth elements (ree) to decipher the origin of ore fluids associated with granite intrusions Minerals 2019, 9, 426.

- Candela, P.A. A review of shallow, ore-related granites: Textures, volatiles, and ore metals. Journal of Petrology 1997, 38, 1619–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migdisov, A.A.; Williams-Jones, A.E.; Wagner, T. An experimental study of the solubility and speciation of the rare earth elements (iii) in fluoride- and chloride-bearing aqueous solutions at temperatures up to 300°c. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2009, 73, 7087–7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choppin, G.R. In Factors in the complexation of lanthanides. In: Lundin c e, ed, Proc of the Rare Earth Res Conf, 12th, Vail, CO, USA, 1976; Vail, CO, USA, pp 130-139.

- Huang, D.H., Wu, Cheng Y, Han, JiuZhu Ree geochemistry and mineralization characteristics of the zudong and gnanxi granites, jiangxi province. Acta Geologica Sinica(English Edition) 1989, 139-157.

- Rolland, Y.; Cox, S.; Boullier, A.M.; Pennacchioni, G.; Mancktelow, N. Rare earth and trace element mobility in mid-crustal shear zones: Insights from the mont blanc massif (western alps). Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2003, 214, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.A. The aqueous geochemistry of the rare-earth elements and yttrium: 1. Review of available low-temperature data for inorganic complexes and the inorganic ree speciation of natural waters. Chemical Geology 1990, 82, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bern, C.R.; Yesavage, T.; Foley, N.K. Ion-adsorption rees in regolith of the liberty hill pluton, south carolina, USA: An effect of hydrothermal alteration. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2017, 172, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.W.; Fu, J.M.; Xing, G.F.; Cheng, S.B.; Lu, Y.Y.; Zhu, Y.X. The petrogenetic differences of the middle-late jurassic w-, sn-, pb-zncu-bearing granites in the nanling range, south china. Geology in China 2022, 49, 518–541. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, B.W.; White, A.J.R. Two constrasting granite types. Pacific Geology 1974, 8, 173–174. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, B.W.; White, A.J.R. I- and s-type granites in the lachlan fold belt. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 1992, 79, 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.Y.; Li, X.H.; Yang, J.H.; Zheng, Y.H. Discussions on the petrogenesis of granites. Acta Petrologica Sinica 2007, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Whalen, J.B. Geochemistry of an island-arc plutonic suite: The uasilau-yau yau intrusive complex, new britain, p.N.G. Journal of Petrology 1985, 26, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, B. A-type granites and related rocks: Evolution of a concept, problems and prospects. Lithos 2007, 97, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, G.N. The a-type granitoids: A review of their occurrence and chemical characteristics and speculations on their petrogenesis. Lithos 1990, 26, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.L.; White, A.J.R.; Chappell, B.W.; Allen, C.M. Characterization and origin of aluminous a-type granites from the lachlan fold belt, southeastern australia. Journal of Petrology 1997, 38, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, J.B.; Currie, K.L.; Chappell, B.W. A-type granites: Geochemical characteristics, discrimination and petrogenesis. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1987, 95, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, X.; Ji, W.; Wang, J.M.; Yang, L. Highly fractionated granites: Recognition and research. Science China Earth Sciences 2017, 60, 1201–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.W.; Mo, X.X.; Zhao, Z.D.; Zhu, D.C. A discussion on how to discriminate a-type granite. Geological Bulletin of China 2010, 29, 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, E.B.; Harrison, T.M. Zircon saturation revisited: Temperature and composition effects in a variety of crustal magma types. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1983, 64, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Long, X.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Sun, M.; Xiao, W. Petrogenesis of late paleozoic diorites and a-type granites in the central eastern tianshan, nw china: Response to post-collisional extension triggered by slab breakoff. Lithos 2018, 318-319, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsli, O.; Aydin, F.; Uysal, I.; Dokuz, A.; Kumral, M.; Kandemir, R.; Budakoglu, M.; Ketenci, M. Latest cretaceous “a2-type” granites in the sakarya zone, ne turkey: Partial melting of mafic lower crust in response to roll-back of neo-tethyan oceanic lithosphere. Lithos 2018, 302-303, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; Peate, D.W. Tectonic implications of the composition of volcanic arc magmas. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 1995, 23, 251–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R.; Gao, S. The role of lower crustal recycling in continent formation. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2003, 67, A403. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Lai, S.C.; Qin, J.F.; Zhu, R.Z.; Zhang, F.Y.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Gan, B.P. Petrogenesis and geodynamic implications of neoproterozoic gabbro-diorites, adakitic granites, and a-type granites in the southwestern margin of the yangtze block, south china. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 183, 103977. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Q.; Li, X.H.; Li, W.X.; Li, Z.X. Formation of high δ18o fayalite-bearing a-type granite by hightemperature melting of granulitic metasedimentary rocks, southern china. Geology 2011, 39, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, J.D.; Holloway, J.R.; White, A.J.R. Origin of an a-type granite; experimental constraints. American Mineralogist 1986, 71, 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, W.J.; Beams, S.D.; White, A.J.R.; Chappell, B.W. Nature and origin of a-type granites with particular reference to southeastern australia. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1982, 80, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Fu, L.; Wei, J.; Selby, D.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y. Proto-tethys magmatic evolution along northern gondwana: Insights from late silurian–middle devonian a-type magmatism, east kunlun orogen, northern tibetan plateau, china. Lithos 2020, 356-357, 105304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, C.D.; Frost, B.R. On ferroan (a-type) granitoids: Their compositional variability and modes of origin. Journal of Petrology 2011, 52, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño Douce, A.E. Generation of metaluminous a-type granites by low-pressure melting of calc-alkaline granitoids. Geology 1997, 25, 743–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaser, R.A.; Price, R.C.; Wormald, R.J. A-type granites revisited. Assessment of a residual-source model. Geology 1991, 19, 163–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Zhao, T.; Peng, T. Age and geochemistry of the early mesoproterozoic a-type granites in the southern margin of the north china craton: Constraints on their petrogenesis and tectonic implications. Precambrian Research 2016, 283, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, P.J. Post-collisional strongly peraluminous granites. Lithos 1998, 45, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiter, K. Nearly contemporaneous evolution of the a- and s-type fractionated granites in the krušné hory/erzgebirge mts., central europe. Lithos 2012, 151, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño Douce, A.E. What do experiments tell us about the relative contributions of crust and mantle to the origin of granitic magmas? Geological Society, London, Special Publications 1999, 168, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.Y. The differentiation mechanism of rare earth elements in parent rocks of ion adsorption-type rare earth element deposits D, China University of Geosciences Beijing, 2020.

- Anenburg, M.; Mavrogenes, J.A.; Frigo, C.; Wall, F. Rare earth element mobility in and around carbonatites controlled by sodium, potassium, and silica. Science Advances 2020, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eby, G.N. Chemical subdivision of the a-type granitoids: Petrogenetic and tectonic implications. Geology 1992, 20, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.X.; Wang, X.G.; Zhang, D.F.; Zhang, Y.W.; Gong, L.X.; Zhong, W. Petrogenesis and ree mineralogical characteristics of shitouping granites in southern jiangxi province: Implication for hree mineralization in south china. Ore Geology Reviews 2024, 168, 106011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.S.; Zhao, K.; He, Z.Y.; Liu, L.; Hong, W.T. Cretaceous volcanic-plutonic magmatism in se china and a genetic model. Lithos 2021, 402-403, 105728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, G.; Chen, H.; Feng, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, C.-K. Are south china granites special in forming ion-adsorption ree deposits? Gondwana Research 2024, 125, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Th | U | Th/U | U-Th-Pb isotopic ratio | Age (Ma) | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | ppm | 207Pb/206Pb | 1σ | 207Pb/235U | 1σ | 206Pb/238U | 1σ | 208Pb/232Th | 1σ | 207Pb/206Pb | 1σ | 207Pb/235U | 1σ | 206Pb/238U | 1σ | 208Pb/232Th | 1σ | |||||||

| KY-05 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 01 | 193 | 296 | 0.65 | 0.06626 | 0.00127 | 1.28018 | 0.02483 | 0.14000 | 0.00120 | 0.04314 | 0.00066 | 815 | 39 | 837 | 11 | 845 | 7 | 854 | 13 | |||||

| 02 | 90.2 | 132 | 0.68 | 0.07042 | 0.00170 | 1.35085 | 0.03499 | 0.13908 | 0.00161 | 0.04179 | 0.00083 | 943 | 45 | 868 | 15 | 839 | 9 | 828 | 16 | |||||

| 03 | 166 | 291 | 0.57 | 0.06700 | 0.00130 | 1.34231 | 0.02597 | 0.14533 | 0.00124 | 0.04469 | 0.00073 | 839 | 40 | 864 | 11 | 875 | 7 | 884 | 14 | |||||

| 04 | 246 | 671 | 0.37 | 0.06642 | 0.00096 | 1.30827 | 0.02109 | 0.14263 | 0.00141 | 0.04322 | 0.00075 | 820 | 30 | 849 | 9 | 860 | 8 | 855 | 15 | |||||

| 05 | 104 | 148 | 0.70 | 0.07064 | 0.00168 | 1.34409 | 0.03524 | 0.13753 | 0.00163 | 0.04243 | 0.00080 | 946 | 48 | 865 | 15 | 831 | 9 | 840 | 15 | |||||

| 06 | 141 | 177 | 0.79 | 0.06764 | 0.00138 | 1.30692 | 0.02830 | 0.14003 | 0.00159 | 0.03985 | 0.00064 | 857 | 42 | 849 | 12 | 845 | 9 | 790 | 12 | |||||

| 07 | 126 | 174 | 0.72 | 0.06565 | 0.00177 | 1.28525 | 0.03574 | 0.14213 | 0.00187 | 0.04327 | 0.00079 | 794 | 56 | 839 | 16 | 857 | 11 | 856 | 15 | |||||

| 08 | 207 | 312 | 0.67 | 0.06636 | 0.00134 | 1.29893 | 0.02785 | 0.14171 | 0.00149 | 0.04262 | 0.00073 | 817 | 43 | 845 | 12 | 854 | 8 | 844 | 14 | |||||

| 09 | 183 | 248 | 0.74 | 0.06552 | 0.00149 | 1.29019 | 0.02838 | 0.14323 | 0.00158 | 0.04216 | 0.00068 | 791 | 48 | 841 | 13 | 863 | 9 | 835 | 13 | |||||

| 10 | 131 | 218 | 0.60 | 0.06518 | 0.00144 | 1.37827 | 0.03497 | 0.15307 | 0.00205 | 0.04764 | 0.00097 | 789 | 47 | 880 | 15 | 918 | 11 | 941 | 19 | |||||

| 11 | 87.1 | 225 | 0.39 | 0.06549 | 0.00146 | 1.27094 | 0.02931 | 0.14051 | 0.00124 | 0.04183 | 0.00079 | 791 | 46 | 833 | 13 | 848 | 7 | 828 | 15 | |||||

| 12 | 109 | 283 | 0.39 | 0.06634 | 0.00119 | 1.25833 | 0.02381 | 0.13755 | 0.00144 | 0.04284 | 0.00070 | 817 | 32 | 827 | 11 | 831 | 8 | 848 | 13 | |||||

| 13 | 161 | 347 | 0.46 | 0.06524 | 0.00118 | 1.27030 | 0.02445 | 0.14095 | 0.00121 | 0.04498 | 0.00077 | 783 | 39 | 833 | 11 | 850 | 7 | 889 | 15 | |||||

| 14 | 137 | 158 | 0.87 | 0.06707 | 0.00165 | 1.28405 | 0.03330 | 0.13882 | 0.00165 | 0.04235 | 0.00080 | 839 | 56 | 839 | 15 | 838 | 9 | 838 | 15 | |||||

| 15 | 129 | 289 | 0.45 | 0.06736 | 0.00157 | 1.42050 | 0.04111 | 0.15237 | 0.00233 | 0.04936 | 0.00109 | 850 | 49 | 898 | 17 | 914 | 13 | 974 | 21 | |||||

| KY-08 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 01 | 2454 | 6351 | 0.39 | 0.06523 | 0.00113 | 0.59374 | 0.01087 | 0.06584 | 0.00081 | 0.01900 | 0.00051 | 783 | 35 | 473 | 7 | 411 | 5 | 380 | 10 | |||||

| 02 | 361 | 308 | 1.17 | 0.07032 | 0.00157 | 1.32532 | 0.02936 | 0.13635 | 0.00129 | 0.04164 | 0.00067 | 939 | 42 | 857 | 13 | 824 | 7 | 825 | 13 | |||||

| 03 | 366 | 295 | 1.24 | 0.05261 | 0.00158 | 0.40154 | 0.01272 | 0.05510 | 0.00063 | 0.01712 | 0.00028 | 322 | 73 | 343 | 9 | 346 | 4 | 343 | 6 | |||||

| 04 | 492 | 1159 | 0.42 | 0.07043 | 0.00104 | 1.32926 | 0.02021 | 0.13653 | 0.00123 | 0.04433 | 0.00059 | 943 | 31 | 859 | 9 | 825 | 7 | 877 | 11 | |||||

| 05 | 483 | 1703 | 0.28 | 0.06621 | 0.00098 | 1.21120 | 0.01926 | 0.13216 | 0.00117 | 0.03176 | 0.00070 | 813 | 30 | 806 | 9 | 800 | 7 | 632 | 14 | |||||

| 06 | 199 | 305 | 0.65 | 0.06718 | 0.00137 | 1.23369 | 0.02479 | 0.13302 | 0.00138 | 0.04082 | 0.00063 | 843 | -158 | 816 | 11 | 805 | 8 | 809 | 12 | |||||

| 07 | 186 | 265 | 0.70 | 0.06677 | 0.00131 | 1.24488 | 0.02478 | 0.13499 | 0.00144 | 0.04205 | 0.00062 | 831 | 41 | 821 | 11 | 816 | 8 | 832 | 12 | |||||

| 08 | 251 | 364 | 0.69 | 0.05452 | 0.00156 | 0.44474 | 0.01233 | 0.05913 | 0.00053 | 0.01804 | 0.00032 | 394 | 65 | 374 | 9 | 370 | 3 | 361 | 6 | |||||

| 09 | 405 | 509 | 0.80 | 0.06979 | 0.00174 | 0.59865 | 0.01454 | 0.06242 | 0.00100 | 0.02250 | 0.00035 | 924 | 51 | 476 | 9 | 390 | 6 | 450 | 7 | |||||

| 10 | 384 | 409 | 0.94 | 0.07518 | 0.00151 | 1.34947 | 0.02982 | 0.12953 | 0.00127 | 0.04172 | 0.00078 | 1073 | 45 | 867 | 13 | 785 | 7 | 826 | 15 | |||||

| 11 | 527 | 693 | 0.76 | 0.37045 | 0.00871 | 3.44825 | 0.10373 | 0.06695 | 0.00088 | 0.09578 | 0.00382 | 3794 | 36 | 1515 | 24 | 418 | 5 | 1849 | 70 | |||||

| 12 | 239 | 193 | 1.24 | 0.11551 | 0.00173 | 5.27910 | 0.08117 | 0.33034 | 0.00283 | 0.09412 | 0.00125 | 1888 | 27 | 1865 | 13 | 1840 | 14 | 1818 | 23 | |||||

| 13 | 397 | 562 | 0.71 | 0.07451 | 0.00170 | 1.43403 | 0.03242 | 0.13940 | 0.00143 | 0.05016 | 0.00448 | 1055 | 46 | 903 | 14 | 841 | 8 | 989 | 86 | |||||

| 14 | 201 | 314 | 0.64 | 0.06713 | 0.00115 | 1.30399 | 0.02340 | 0.14062 | 0.00155 | 0.04117 | 0.00059 | 843 | 36 | 847 | 10 | 848 | 9 | 816 | 12 | |||||

| 15 | 503 | 351 | 1.43 | 0.12010 | 0.00660 | 0.77236 | 0.04909 | 0.04544 | 0.00050 | 0.01791 | 0.00065 | 1958 | 98 | 581 | 28 | 286 | 3 | 359 | 13 | |||||

| 16 | 190 | 205 | 0.92 | 0.06805 | 0.00133 | 1.28945 | 0.02564 | 0.13696 | 0.00115 | 0.04005 | 0.00056 | 870 | 40 | 841 | 11 | 827 | 7 | 794 | 11 | |||||

| 17 | 259 | 372 | 0.70 | 0.06707 | 0.00121 | 1.28975 | 0.02325 | 0.13913 | 0.00117 | 0.03931 | 0.00054 | 839 | -162 | 841 | 10 | 840 | 7 | 779 | 10 | |||||

| 18 | 206 | 335 | 0.62 | 0.06594 | 0.00126 | 1.27282 | 0.02257 | 0.14004 | 0.00146 | 0.04032 | 0.00059 | 806 | 40 | 834 | 10 | 845 | 8 | 799 | 11 | |||||

| 19 | 264 | 433 | 0.61 | 0.07959 | 0.00215 | 1.45701 | 0.03381 | 0.13339 | 0.00129 | 0.04868 | 0.00122 | 1187 | 53 | 913 | 14 | 807 | 7 | 961 | 24 | |||||

| 20 | 275 | 591 | 0.47 | 0.06670 | 0.00117 | 1.27296 | 0.02212 | 0.13806 | 0.00128 | 0.04112 | 0.00063 | 828 | 37 | 834 | 10 | 834 | 7 | 814 | 12 | |||||

| Sample | KY-01 | KY-02 | KY-03 | KY-04 | KY-05 | KY-06 | KY-07 | KY-08 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LREE-rich granite | HREE-rich granite | |||||||||||||||

| SiO2 | 73.30 | 76.98 | 77.02 | 73.12 | 76.73 | 70.55 | 74.74 | 78.34 | ||||||||

| TiO2 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| Al2O3 | 13.40 | 11.35 | 11.94 | 13.20 | 12.27 | 15.20 | 13.76 | 11.90 | ||||||||

| Fe2O3T | 2.68 | 1.83 | 1.64 | 2.43 | 1.52 | 2.87 | 1.44 | 0.47 | ||||||||

| MnO | 0.028 | 0.014 | 0.018 | 0.029 | 0.018 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| MgO | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.54 | 0.09 | 0.39 | 0.08 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| CaO | 1.15 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 1.79 | 0.52 | 0.99 | 0.33 | 0.42 | ||||||||

| Na2O | 2.82 | 2.67 | 2.52 | 3.64 | 2.56 | 2.63 | 2.84 | 3.80 | ||||||||

| K2O | 5.36 | 5.67 | 5.06 | 3.39 | 4.96 | 5.57 | 5.31 | 4.39 | ||||||||

| P2O5 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| LOI | 0.48 | 0.63 | 0.73 | 1.30 | 1.06 | 1.12 | 1.25 | 0.46 | ||||||||

| TOTAL | 99.82 | 99.87 | 99.86 | 99.84 | 99.84 | 99.78 | 99.86 | 99.87 | ||||||||

| A/CNK | 1.07 | 1.00 | 1.14 | 1.02 | 1.17 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| A/NK | 1.28 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.37 | 1.28 | 1.47 | 1.32 | 1.08 | ||||||||

| DI | 89.48 | 95.16 | 93.33 | 86.29 | 93.50 | 87.43 | 93.55 | 97.07 | ||||||||

| SI | 2.35 | 1.17 | 3.39 | 5.45 | 1.02 | 3.49 | 0.80 | 0.50 | ||||||||

| Li | 18.45 | 8.50 | 7.80 | 17.66 | 10.97 | 10.47 | 15.04 | 2.09 | ||||||||

| Be | 4.00 | 4.32 | 3.16 | 4.06 | 4.59 | 3.26 | 5.57 | 23.05 | ||||||||

| Sc | 6.50 | 6.97 | 7.73 | 8.62 | 7.17 | 7.46 | 7.54 | 5.16 | ||||||||

| V | 8.43 | 4.24 | 2.42 | 10.71 | 3.07 | 15.09 | 4.68 | 3.00 | ||||||||

| Cr | 6.32 | 3.50 | ND | 5.80 | 4.33 | 9.08 | 4.90 | 2.53 | ||||||||

| Co | 2.22 | 1.08 | 0.74 | 2.68 | 0.65 | 3.49 | 0.56 | 0.82 | ||||||||

| Ni | 0.92 | 0.66 | ND | 1.30 | 1.33 | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.49 | ||||||||

| Cu | 1.34 | 1.09 | 3.88 | 12.47 | 2.18 | 2.44 | 2.02 | 2.25 | ||||||||

| Zn | 39.37 | 25.91 | 22.20 | 26.63 | 26.50 | 31.66 | 23.75 | 7.75 | ||||||||

| Ga | 24.83 | 24.86 | 26.6 | 26.31 | 25.01 | 26.32 | 24.77 | 21.46 | ||||||||

| Rb | 292.02 | 298.85 | 300.00 | 186.07 | 378.04 | 217.67 | 480.32 | 292.12 | ||||||||

| Sr | 76.87 | 24.31 | 36.40 | 111.85 | 21.19 | 106.29 | 28.70 | 25.17 | ||||||||

| Sn | 5.26 | 5.67 | 8.72 | 6.30 | 8.66 | 6.37 | 12.84 | 4.19 | ||||||||

| Cs | 5.09 | 3.08 | 2.10 | 1.90 | 4.69 | 2.04 | 8.53 | 1.40 | ||||||||

| Ba | 499.20 | 54.64 | 118.00 | 424.36 | 121.62 | 1019.83 | 155.73 | 122.79 | ||||||||

| Tl | 1.54 | 1.38 | 1.29 | 0.97 | 1.70 | 0.81 | 2.33 | 1.33 | ||||||||

| Pb | 24.69 | 29.63 | 33.00 | 13.75 | 10.47 | 0.49 | 11.00 | 31.07 | ||||||||

| Th | 46.87 | 47.24 | 50.00 | 45.18 | 57.42 | 51.87 | 45.84 | 32.65 | ||||||||

| U | 5.01 | 6.74 | 10.40 | 7.78 | 9.58 | 4.32 | 9.37 | 11.99 | ||||||||

| Nb | 12.60 | 12.53 | 13.00 | 16.39 | 13.30 | 13.82 | 19.06 | 14.43 | ||||||||

| Ta | 1.10 | 1.32 | 1.50 | 1.79 | 1.69 | 1.29 | 3.58 | 2.26 | ||||||||

| Zr | 153.91 | 190.08 | 146.00 | 183.44 | 275.80 | 166.02 | 237.24 | 192.80 | ||||||||

| Hf | 6.21 | 7.72 | 5.18 | 7.07 | 10.59 | 5.14 | 9.98 | 12.47 | ||||||||

| Zr/Hf | 24.79 | 24.62 | 28.19 | 25.95 | 26.04 | 32.33 | 23.78 | 15.46 | ||||||||

| Nb/Ta | 11.50 | 9.47 | 8.67 | 9.15 | 7.87 | 10.68 | 5.33 | 6.38 | ||||||||

| Rb/Sr | 3.80 | 12.29 | 8.24 | 1.66 | 17.84 | 2.05 | 16.74 | 11.60 | ||||||||

| La | 87.42 | 85.78 | 53.40 | 76.23 | 88.08 | 69.06 | 37.39 | 14.96 | ||||||||

| Ce | 180.36 | 173.15 | 124.00 | 154.05 | 145.65 | 169.13 | 72.86 | 33.61 | ||||||||

| Pr | 19.30 | 19.95 | 14.10 | 16.91 | 24.39 | 17.33 | 10.28 | 3.87 | ||||||||

| Nd | 74.02 | 74.08 | 51.40 | 66.21 | 93.09 | 61.52 | 40.87 | 18.63 | ||||||||

| Sm | 13.77 | 14.04 | 11.40 | 13.61 | 19.47 | 11.62 | 10.38 | 9.18 | ||||||||

| Eu | 0.91 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.85 | 0.49 | 1.46 | 0.30 | 0.22 | ||||||||

| Gd | 12.08 | 11.88 | 9.82 | 12.89 | 19.82 | 10.42 | 10.12 | 17.67 | ||||||||

| Tb | 1.81 | 1.90 | 1.77 | 2.13 | 3.32 | 1.60 | 1.75 | 3.90 | ||||||||

| Dy | 9.38 | 10.43 | 9.55 | 11.96 | 19.22 | 8.84 | 10.10 | 28.99 | ||||||||

| Ho | 1.75 | 2.01 | 1.91 | 2.43 | 4.06 | 1.82 | 2.13 | 6.84 | ||||||||

| Er | 4.66 | 5.81 | 5.58 | 7.00 | 11.35 | 5.08 | 6.59 | 21.36 | ||||||||

| Tm | 0.66 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 1.04 | 1.72 | 0.76 | 1.06 | 3.48 | ||||||||

| Yb | 3.90 | 5.40 | 5.92 | 6.37 | 10.63 | 4.72 | 7.28 | 21.77 | ||||||||

| Lu | 0.57 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 1.54 | 0.66 | 1.13 | 3.25 | ||||||||

| Y | 43.55 | 45.57 | 49.90 | 68.25 | 111.03 | 50.49 | 54.66 | 231.21 | ||||||||

| ∑REE | 454.13 | 451.88 | 340.81 | 440.84 | 553.88 | 414.51 | 266.91 | 418.93 | ||||||||

| ∑LREE | 375.77 | 367.23 | 254.58 | 327.85 | 375.77 | 367.23 | 80.46 | 80.46 | ||||||||

| ∑HREE | 78.36 | 84.64 | 86.23 | 112.99 | 182.70 | 84.38 | 94.82 | 338.47 | ||||||||

| L/HREE | 4.80 | 4.34 | 2.95 | 2.90 | 2.03 | 3.91 | 1.81 | 0.24 | ||||||||

| δEu | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.41 | 0.09 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| δCe | 1.08 | 1.03 | 1.11 | 1.05 | 0.77 | 1.20 | 0.91 | 1.08 | ||||||||

| (La/Yb)N | 16.07 | 11.40 | 6.47 | 8.58 | 5.94 | 10.50 | 3.68 | 0.49 | ||||||||

| Sample | 87Rb/86Sr | 87Sr/86Sr | ±2σ | (87Sr/86Sr)i | 147Sm/144Nd | 143Nd/144Nd | ±2σ | (143Nd/144Nd)i | εNd(t) | T2DM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KY-01 | 10.99 | 0.858502 | 0.000006 | 0.729158 | 0.11241 | 0.511934 | 0.000006 | 0.511327 | -4.9 | 1884 |

| KY-05 | 51.62 | 1.325471 | 0.000016 | 0.718041 | 0.12642 | 0.512039 | 0.000005 | 0.511356 | -4.3 | 1839 |

| KY-08 | 33.58 | 1.099860 | 0.000028 | 0.700121 | 0.29775 | 0.512895 | 0.000005 | 0.511268 | -5.8 | 1966 |

| Analytical spot | 176Yb/177Hf | 1σ | 176Lu/177Hf | 1σ | 176Hf/177Hf | 1σ | (176Hf/177Hf)i | fLu/Hf | εHf(t) | 1σ | TDM1 | TDM2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LREE-rich granites (KY-05) | ||||||||||||

| KY05-1 | 0.034185 | 0.000047 | 0.000961 | 0.000001 | 0.282190 | 0.000008 | 0.282175 | -0.94 | -3.2 | 0.3 | 1495 | 1894 |

| KY05-2 | 0.034901 | 0.000177 | 0.000980 | 0.000006 | 0.282201 | 0.000009 | 0.282186 | -0.93 | -2.8 | 0.3 | 1481 | 1871 |

| KY05-3 | 0.050090 | 0.000384 | 0.001402 | 0.000009 | 0.282154 | 0.000008 | 0.282132 | -0.91 | -4.7 | 0.3 | 1564 | 1989 |

| KY05-4 | 0.057255 | 0.000841 | 0.001535 | 0.000022 | 0.282197 | 0.000007 | 0.282173 | -0.90 | -3.2 | 0.2 | 1508 | 1899 |

| KY05-5 | 0.037510 | 0.000078 | 0.001017 | 0.000003 | 0.282210 | 0.000008 | 0.282194 | -0.93 | -2.5 | 0.3 | 1470 | 1852 |

| KY05-6 | 0.038630 | 0.000161 | 0.001187 | 0.000010 | 0.282191 | 0.000008 | 0.282173 | -0.92 | -3.2 | 0.3 | 1503 | 1900 |

| KY05-7 | 0.043113 | 0.000109 | 0.001200 | 0.000002 | 0.282175 | 0.000007 | 0.282156 | -0.92 | -3.8 | 0.2 | 1526 | 1936 |

| KY05-8 | 0.029451 | 0.000178 | 0.000831 | 0.000004 | 0.282215 | 0.000007 | 0.282202 | -0.94 | -2.2 | 0.2 | 1456 | 1835 |

| KY05-9 | 0.030116 | 0.000168 | 0.000823 | 0.000003 | 0.282210 | 0.000008 | 0.282197 | -0.95 | -2.4 | 0.3 | 1462 | 1845 |

| KY05-10 | 0.028884 | 0.000161 | 0.000795 | 0.000003 | 0.282206 | 0.000008 | 0.282194 | -0.95 | -2.5 | 0.3 | 1467 | 1853 |

| KY05-11 | 0.066287 | 0.000248 | 0.001850 | 0.000006 | 0.282164 | 0.000007 | 0.282135 | -0.88 | -4.6 | 0.2 | 1568 | 1982 |

| KY05-12 | 0.063962 | 0.000166 | 0.001753 | 0.000006 | 0.282171 | 0.000007 | 0.282144 | -0.88 | -4.3 | 0.2 | 1554 | 1963 |

| KY05-13 | 0.044720 | 0.000354 | 0.001263 | 0.000010 | 0.282185 | 0.000007 | 0.282165 | -0.92 | -3.5 | 0.2 | 1514 | 1916 |

| KY05-14 | 0.041558 | 0.000193 | 0.001163 | 0.000004 | 0.282208 | 0.000008 | 0.282190 | -0.92 | -2.6 | 0.3 | 1478 | 1861 |

| KY05-15 | 0.036356 | 0.000059 | 0.001027 | 0.000002 | 0.282178 | 0.000008 | 0.282162 | -0.93 | -3.6 | 0.3 | 1515 | 1923 |

| HREE-rich granites (KY-08) | ||||||||||||

| KY08-01 | 0.075296 | 0.000243 | 0.002415 | 0.000011 | 0.282179 | 0.000009 | 0.282141 | -0.84 | -4.1 | 0.3 | 1571 | 1963 |

| KY08-02 | 0.049670 | 0.000758 | 0.001364 | 0.000017 | 0.282219 | 0.000010 | 0.282197 | -0.91 | -2.2 | 0.4 | 1471 | 1839 |

| KY08-04 | 0.048833 | 0.000470 | 0.001625 | 0.000011 | 0.282157 | 0.000019 | 0.282132 | -0.89 | -4.5 | 0.7 | 1568 | 1984 |

| KY08-05 | 0.094402 | 0.001150 | 0.002758 | 0.000024 | 0.282156 | 0.000010 | 0.282113 | -0.82 | -5.1 | 0.3 | 1619 | 2026 |

| KY08-06 | 0.040807 | 0.001470 | 0.001111 | 0.000039 | 0.282230 | 0.000011 | 0.282213 | -0.93 | -1.6 | 0.4 | 1445 | 1805 |

| KY08-07 | 0.058103 | 0.002140 | 0.001831 | 0.000058 | 0.282209 | 0.000025 | 0.282181 | -0.88 | -2.7 | 0.9 | 1503 | 1876 |

| KY08-10 | 0.095172 | 0.001360 | 0.002834 | 0.000062 | 0.282202 | 0.000010 | 0.282158 | -0.81 | -3.6 | 0.3 | 1555 | 1927 |

| KY08-13 | 0.067997 | 0.001080 | 0.002134 | 0.000041 | 0.282184 | 0.000008 | 0.282150 | -0.86 | -3.8 | 0.3 | 1552 | 1943 |

| KY08-14 | 0.043387 | 0.000744 | 0.001393 | 0.000016 | 0.282171 | 0.000012 | 0.282149 | -0.91 | -3.9 | 0.4 | 1540 | 1947 |

| KY08-16 | 0.035592 | 0.000154 | 0.001118 | 0.000010 | 0.282200 | 0.000008 | 0.282182 | -0.93 | -2.7 | 0.3 | 1488 | 1872 |

| KY08-17 | 0.038288 | 0.000195 | 0.001161 | 0.000006 | 0.282225 | 0.000009 | 0.282207 | -0.92 | -1.8 | 0.3 | 1455 | 1819 |

| KY08-18 | 0.024822 | 0.000076 | 0.000750 | 0.000010 | 0.282243 | 0.000017 | 0.282231 | -0.95 | -1.0 | 0.6 | 1414 | 1764 |

| KY08-19 | 0.056776 | 0.000676 | 0.001839 | 0.000029 | 0.282214 | 0.000010 | 0.282185 | -0.88 | -2.6 | 0.3 | 1497 | 1866 |

| KY08-20 | 0.033511 | 0.000263 | 0.001055 | 0.000010 | 0.282249 | 0.000010 | 0.282233 | -0.93 | -0.9 | 0.4 | 1416 | 1761 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).