Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

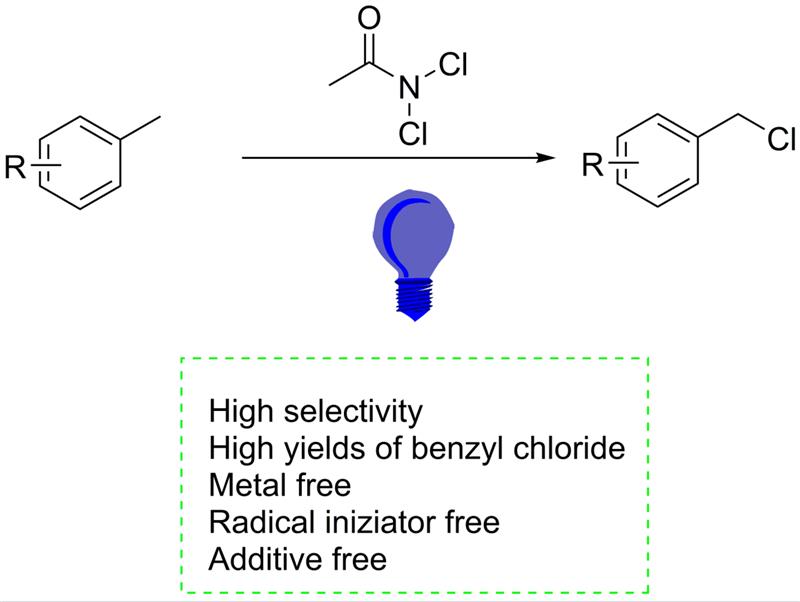

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

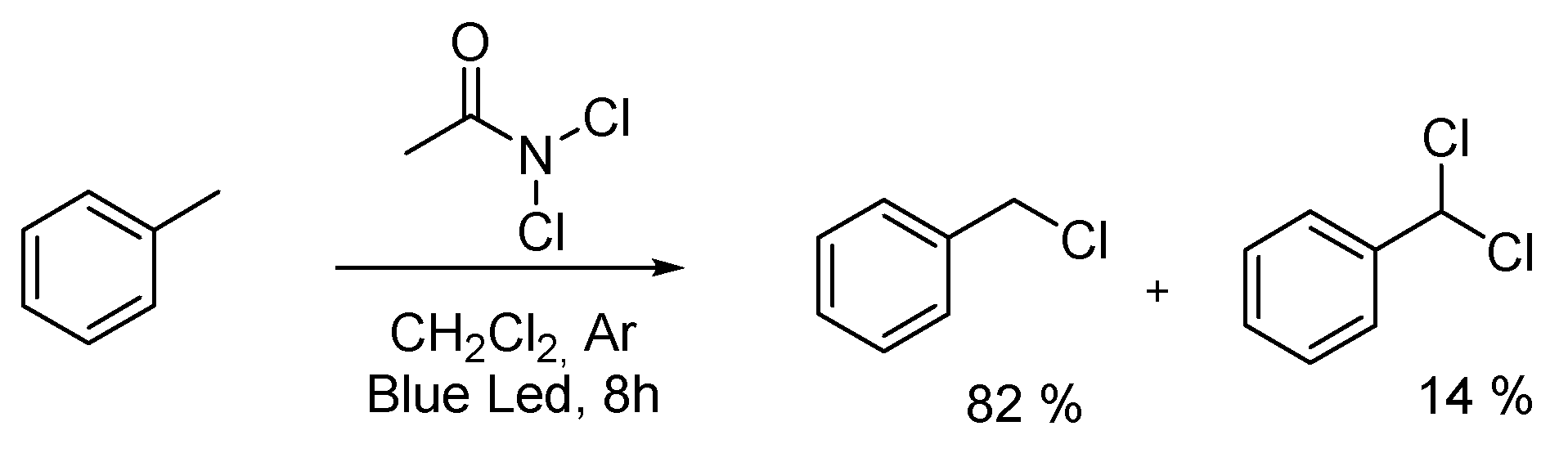

2. Results

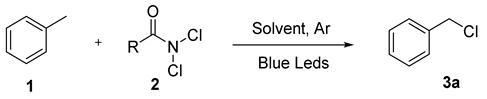

2.1. Optimization of Reaction Conditions

2.2. Scale up of Our Methodology

2.3. Scope of the Reaction

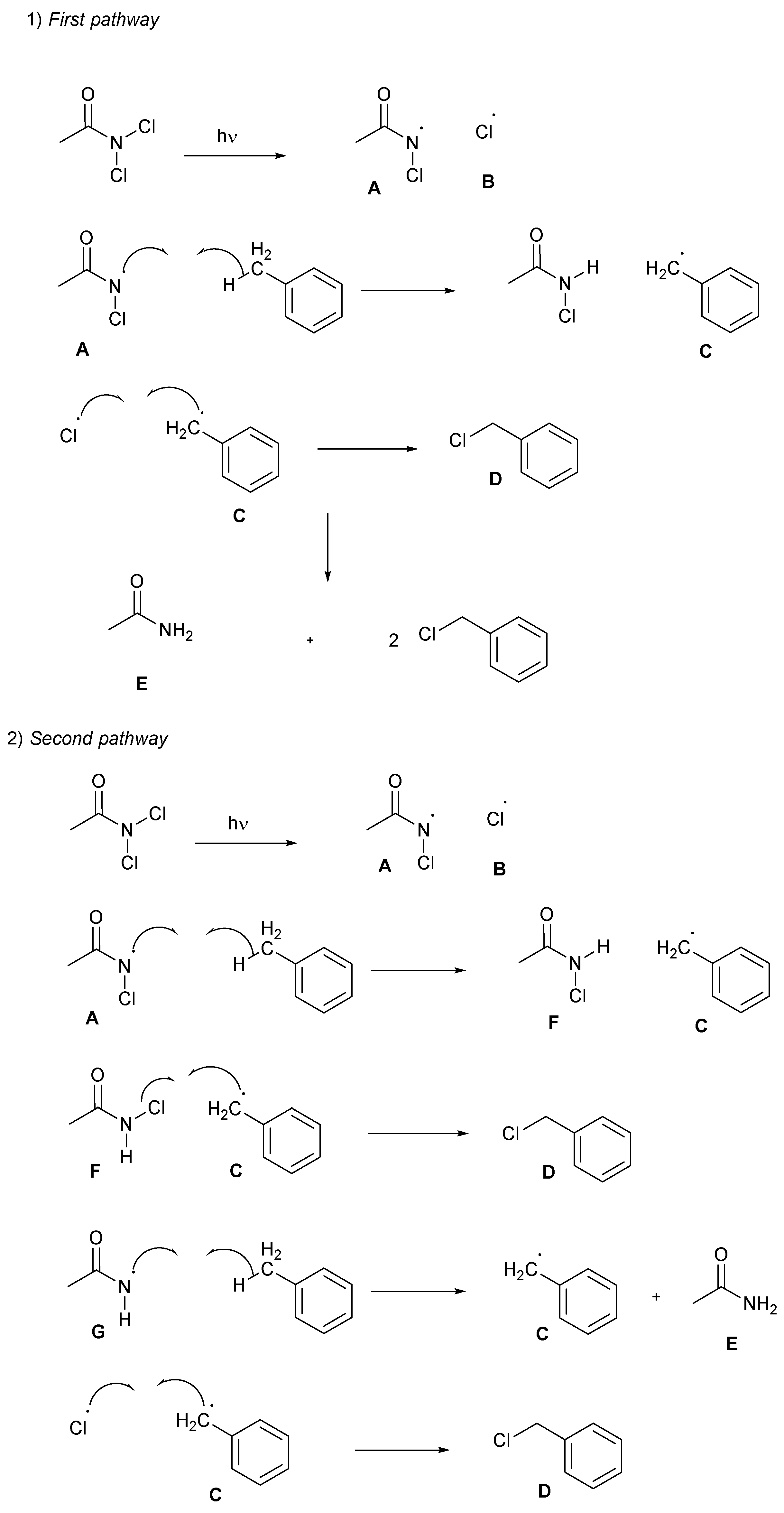

2.4. Proposed Mechanism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

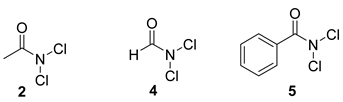

3.2. General Procedure to N,N-dichloroamides 2, 4, 5:[38]

3.3. General Procedure to Compounds 3a-3o:

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gribble, G. W. , Natural Organohalogens: A New Frontier for Medicinal Agents? Journal of Chemical Education 2004, 81(10), 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Amrute, A. P.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. , Halogen-Mediated Conversion of Hydrocarbons to Commodities. Chemical Reviews 2017, 117(5), 4182–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terao, J.; Kambe, N. , Cross-Coupling Reaction of Alkyl Halides with Grignard Reagents Catalyzed by Ni, Pd, or Cu Complexes with π-Carbon Ligand(s). Accounts of Chemical Research 2008, 41(11), 1545–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffinger, P.; Hays, F. A.; Westhof, E.; Ho, P. S. , Halogen bonds in biological molecules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101(48), 16789–16794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrone, D. A.; Ye, J.; Lautens, M. , Modern Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Carbon–Halogen Bond Formation. Chemical Reviews 2016, 116(14), 8003–8104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podgoršek, A.; Zupan, M.; Iskra, J. , Oxidative Halogenation with “Green” Oxidants: Oxygen and Hydrogen Peroxide. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2009, 48(45), 8424–8450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossberg, M.; Lendle, W.; Pfleiderer, G.; Tögel, A.; Dreher, E.-L.; Langer, E.; Rassaerts, H.; Kleinschmidt, P.; Strack, H.; Cook, R.; Beck, U.; Lipper, K.-A.; Torkelson, T. R.; Löser, E.; Beutel, K. K.; Mann, T. , Chlorinated Hydrocarbons. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry.

- Zhang, L.; Hu, X. , Room temperature C(sp2)–H oxidative chlorination via photoredox catalysis. Chemical Science 2017, 8(10), 7009–7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, J.; Kanai, M. , Silver-Catalyzed C(sp3)–H Chlorination. Organic Letters 2017, 19(6), 1430–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furniss, B. S. H., A. J.; Smith, P. W. G.; Tatchell, A. R, Vogel’s Textbook of Practical Organic Chemistry. 5th ed. ed.; Harlow: Longman: 1989; p 864.

- Whitmore, F. C.; Ginsburg, A.; Rueggeberg, W.; Tharp, I.; Nottorf, H.; Cannon, M.; Carnahan, F.; Cryder, D.; Fleming, G.; Goldberg, G.; Haggard, H.; Herr, C.; Hoover, T.; Lovell, H.; Mraz, R.; Noll, C.; Oakwood, T.; Patterson, H.; Van Strien, R.; Walter, R.; Zook, H.; Wagner, R.; Weisgerber, C.; Wilkins, J. , Production of Benzyl Chloride by Chloromethylation of Benzene. Laboratory and Pilot Plant Studies. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry.

- Lei A., S. W., Liu C., Liu W., Zhang H. He C., Oxidative Cross-Coupling Reactions. Wiley-VCH: 2016.

- Delaude, L.; Laszlo, P. , Versatility of zeolites as catalysts for ring or side-chain aromatic chlorinations by sulfuryl chloride. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 1990, 55(18), 5260–5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanemura, K.; Suzuki, T.; Nishida, Y.; Horaguchi, T. , Chlorination of aliphatic hydrocarbons, aromatic compounds, and olefins in subcritical carbon tetrachloride. Tetrahedron Letters 2008, 49(45), 6419–6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharasch, M. S.; Brown, H. C. , Chlorinations with Sulfuryl Chloride. I. The Peroxide-Catalyzed Chlorination of Hydrocarbons. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2142. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, M.; Zhou, C.; Yang, X.-L.; Chen, B.; Tung, C.-H.; Wu, L.-Z. , Visible Light-Catalyzed Benzylic C–H Bond Chlorination by a Combination of Organic Dye (Acr+-Mes) and N-Chlorosuccinimide. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 2020, 85(14), 9080–9087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combe, S. H.; Hosseini, A.; Parra, A.; Schreiner, P. R. , Mild Aliphatic and Benzylic Hydrocarbon C–H Bond Chlorination Using Trichloroisocyanuric Acid. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 2017, 82(5), 2407–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Zhao, Y.; Kyne, S. H.; Farshadfar, K.; Ariafard, A.; Chan, P. W. H. , Copper(I)-catalysed site-selective C(sp3)–H bond chlorination of ketones, (E)-enones and alkylbenzenes by dichloramine-T. Nature Communications 2021, 12(1), 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumamagal, B. T. S.; Narayanasamy, S.; Venkatesan, R. , Regiospecific Chlorination of Xylenes Using K-10 Montmorrillonite Clay. Synthetic Communications 2008, 38(16), 2820–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucos, M.; Villalonga-Barber, C.; Micha-Screttas, M.; Steele, B. R.; Screttas, C. G.; Heropoulos, G. A. , Microwave assisted solid additive effects in simple dry chlorination reactions with n-chlorosuccinimide. Tetrahedron 2010, 66(11), 2061–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspa, S.; Valentoni, A.; Mulas, G.; Porcheddu, A.; De Luca, L. , Metal-Free Preparation of α-H-Chlorinated Alkylaromatic Hydrocarbons by Sunlight. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3(27), 7991–7995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-H.; Fiser, B.; Jiang, B.-L.; Li, J.-W.; Xu, B.-H.; Zhang, S.-J. , N-Hydroxyphthalimide/benzoquinone-catalyzed chlorination of hydrocarbon C–H bond using N-chlorosuccinimide. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 3403. [Google Scholar]

- Çimen, Y.; Akyüz, S.; Türk, H. , Facile, efficient, and environmentally friendly α- and aromatic regioselective chlorination of toluene using KHSO5 and KCl under catalyst-free conditions. New Journal of Chemistry 2015, 39(5), 3894–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, X.; Fan, S.; Huang, J.; Whiting, A. , Highly selective halogenation of unactivated C(sp3)–H with NaX under co-catalysis of visible light and Ag@AgX. Green Chemistry 2018, 20(20), 4729–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu W., Z. M., Li M., Visible-Light-Driven Oxidative Mono- and Dibromination of Benzylic sp3 C–H Bonds with Potassium Bromide/Oxone at Room Temperature Synthesis 2018, 50, 4933–4939. 50.

- Zhao, M.; Lu, W. , Visible Light-Induced Oxidative Chlorination of Alkyl sp3 C–H Bonds with NaCl/Oxone at Room Temperature. Organic Letters 2017, 19(17), 4560–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson C. R. J., Y. T. P., MacMillan D. W. C., Visible light photo-catalysis in organic chemistry,. Wiley-VCH Verlag, Weinheim: 2017.

- Das, R.; Kapur, M. , Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Site-Selective C−H Halogenation Reactions. Asian Journal of Organic Chemistry 2018, 7(8), 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abderrazak, Y.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Reiser, O. , Visible-Light-Induced Homolysis of Earth-Abundant Metal-Substrate Complexes: A Complementary Activation Strategy in Photoredox Catalysis. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2021, 60(39), 21100–21115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, A.; Paul, S.; Bhowmik, S.; Das, R.; Naveen, T.; Rana, S. , Recent Advances in First-Row Transition-Metal-Mediated C−H Halogenation of (Hetero)arenes and Alkanes. Asian Journal of Organic Chemistry 2022, 11(5), e202200060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, T. W.; Sanford, M. S. , Palladium-Catalyzed Ligand-Directed C−H Functionalization Reactions. Chemical Reviews 2010, 110(2), 1147–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racowski, J. M.; Ball, N. D.; Sanford, M. S. , C–H Bond Activation at Palladium(IV) Centers. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2011, 133(45), 18022–18025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Tong, X. , Synthesis of organic halides via palladium(0) catalysis. Organic Chemistry Frontiers 2014, 1(4), 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Tian, X.; Ni, S.-F.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Li, D.; Liu, S. , Visible light-induced FeCl3-catalyzed chlorination of C–H bonds with MgCl2. Green Chemistry 2024, 26(11), 6559–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Tian, X.; Whiting, A. , A Visible-Light-Induced α-H Chlorination of Alkylarenes with Inorganic Chloride under NanoAg@AgCl. Chemistry – A European Journal, 9671. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, M. A.; Buss, J. A.; Stahl, S. S. , Cu-Catalyzed Site-Selective Benzylic Chlorination Enabling Net C–H Coupling with Oxidatively Sensitive Nucleophiles. Organic Letters 2022, 24(2), 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, S.; Tian, X.; Liu, Y.; Fan, S.; Huang, B.; Whiting, A. , Cu@CuCl-visible light co-catalysed chlorination of C(sp3)–H bonds with MCln solution and photocatalytic serial reactor-based synthesis of benzyl chloride. Green Chemistry 2022, 24(1), 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, H.; Audrieth, L. F. , Tertiary Butyl Hypochlorite as as N-Chlorinating Agent. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1954, 76(14), 3856–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J. E.; Guo, W.; Gaspa, S.; Kleij, A. W. , Copper-Catalyzed Synthesis of γ-Amino Acids Featuring Quaternary Stereocenters. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2017, 56(47), 15035–15038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellisanti, A.; Chessa, E.; Porcheddu, A.; Carraro, M.; Pisano, L.; De Luca, L.; Gaspa, S. , Visible Light-Promoted Oxidative Cross-Coupling of Alcohols to Esters. Molecules 2024, 29(3), 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspa, S.; Raposo, I.; Pereira, L.; Mulas, G.; Ricci, P. C.; Porcheddu, A.; De Luca, L. , Visible light-induced transformation of aldehydes to esters, carboxylic anhydrides and amides. New Journal of Chemistry 2019, 43(27), 10711–10715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgoršek, A.; Stavber, S.; Zupan, M.; Iskra, J. , Visible light induced ‘on water’ benzylic bromination with N-bromosuccinimide. Tetrahedron Letters 2006, 47(7), 1097–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalapathy, C.; Pitchumani, K. , Selectivity in bromination of alkylbenzenes in the presence of montmorillonite clay. Tetrahedron 1997, 53(7), 2581–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Muñiz, K. , Selective Piperidine Synthesis Exploiting Iodine-Catalyzed Csp3–H Amination under Visible Light. ACS Catalysis 2017, 7(6), 4122–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, I.; Borah, A. J.; Phukan, P. , Use of Bromine and Bromo-Organic Compounds in Organic Synthesis. Chemical Reviews 2016, 116(12), 6837–7042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillard, S. E.; Schulte, B.; Studer, A. , Radical-Based Arylation Methods. In Modern Arylation Methods, 2009; pp 475-511.

| |||||

| Entry1 | Toluene (mmol) | Cl-source (mmol) | Solvent | Time (h) | Yield2 (%) |

| 1 | 2 | (2) 1 | DCM | 8 | 64 % |

| 2 | 2 | (2) 1.2 | DCM | 8 | 70 % |

| 3 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | DCM | 8 | 79 % |

| 4 | 2 | (2) 2 | DCM | 8 | 70 % |

| 5 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | DCM | 0.5 | 36 % |

| 6 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | DCM | 1 | 44 % |

| 7 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | DCM | 2 | 47 % |

| 8 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | DCM | 3 | 57 % |

| 9 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | DCM | 5 | 65 % |

| 10 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | DCM | 12 | 66 % |

| 11 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | CPME | 8 | - |

| 12 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | CH3CN | 8 | - |

| 13 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | AcOEt | 8 | trace |

| 14 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | 2-MeTHF | 8 | - |

| 15 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | THF | 8 | - |

| 16 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | DCE | 8 | - |

| 17 3 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | DCM | 8 | - |

| 18 4 | 2 | (2) 1.3 | DCM | 8 | - |

| 19 | 2 | (4) 1.3 | DCM | 8 | 47 % |

| 20 | 2 | (5) 1.3 | DCM | 8 | 60 % |

| |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).