Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Heterogeneity in TNBC

BCSCs and the BC Stemness Markers

Characteristics of BCSCs in TNBC

Resistance

Metastasis

Role of ABCG2 and CD133 in Regulating BC Stemness

The Role of the Hippo Pathway Downstream Effectors YAP and TAZ in BC Stem-Like Cells

Overview of the Hippo Pathway

YAP and TAZ – The Acting Arms of the Hippo

YAP/TAZ and Cancer

YAP/TAZ as Drivers and Enhancers of BCSCs

YAP/TAZ Inhibition - A Promising Strategy to Curtail Cancer Stemness

Factors Governing the Maintenance and Clonogenicity of BCSCs

- Plasticity of BCSCs - BCSCs that underwent EMT exhibit enhanced invasive potential, enabling them to disseminate from primary tumors and form distant metastases, contributing to disease progression and poor prognosis. Additionally, such BCSCs display resistance to NACT and targeted therapies, due to their enhanced survival mechanisms and altered gene expression profiles through epigenetic adaptations [239]. The plasticity conferred by EMT enables BCSCs to adapt to changing microenvironments within the tumor and metastatic sites, facilitating tumor relapses. Targeting EMT and its associated signaling pathways may represent a promising therapeutic approach to restrict BCSCs to one state, which prevents plastic conversion to a more resistant form and improves treatment outcomes for BC patients. [240].

- Signaling pathways: Tumor cell signaling pathways such as Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog, and PI3K/Akt/mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), intricately regulate the behavior of BCSCs, dictating their self-renewal and differentiation capabilities [241]. Through a network of molecular interactions, these pathways regulate self-renewal, sustenance of cancer stemness, and survival of BCSCs. These signaling pathways prime and activate BCSCs for aggressive behaviors, fueling invasion, migration, and metastasis. By influencing the gene expression involved in cell fate determination and interactions with TME in a paracrine manner, these signaling cascades modulate the phenotypic and functional heterogeneity within BCSC populations [242,243]. Understanding the crosstalk between these pathways provides insights into the mechanisms underlying BC progression and offers potential co-targets for therapeutic intervention aimed at disrupting BCSC-mediated tumorigenesis and metastasis.

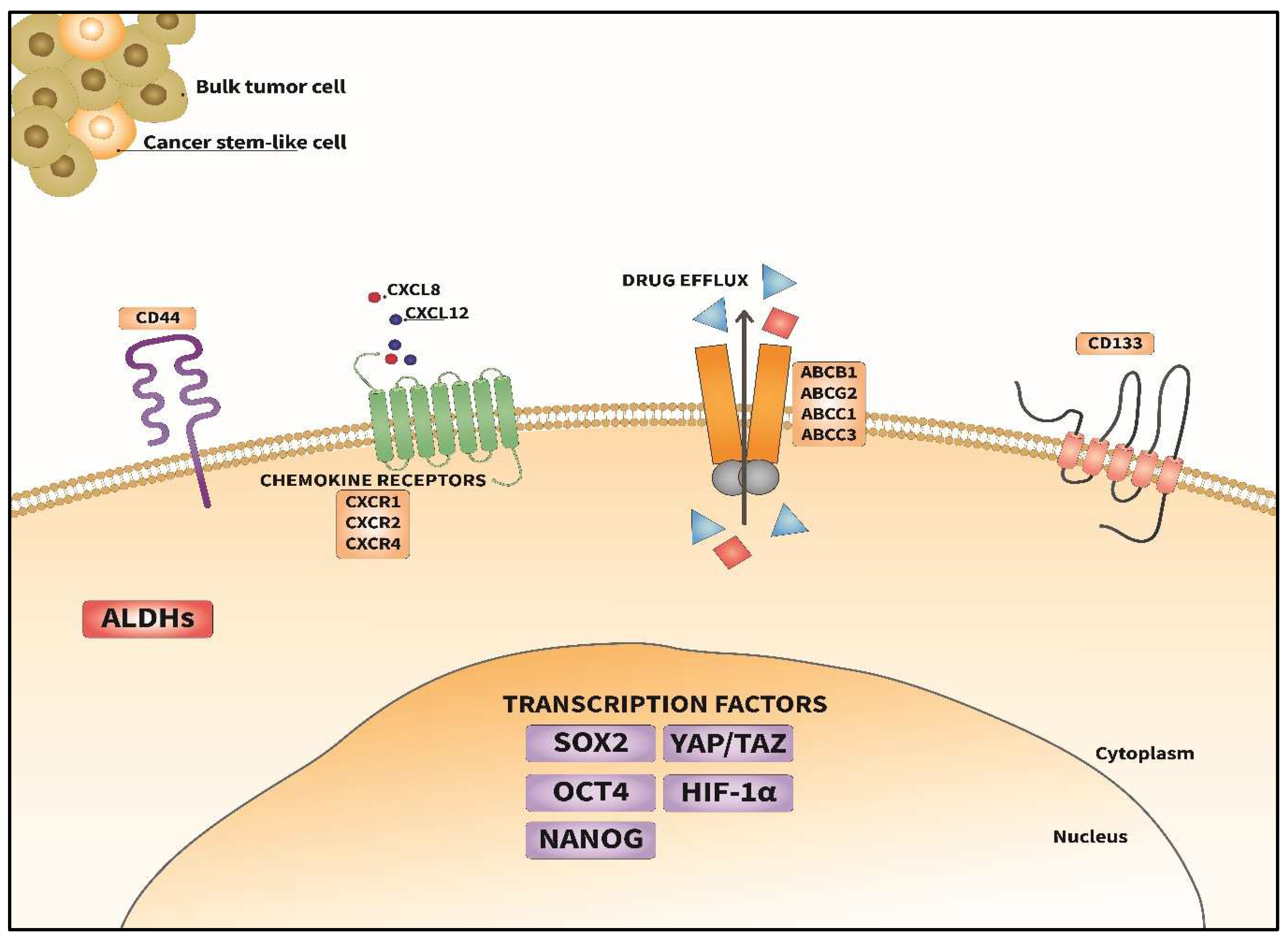

- Transcription factors: PTFs such as SOX2, OCT4 and NANOG serve as master regulators of cancer stemness in BCSCs, activating gene expression that sustains their self-renewal capacity [4]. These TFs exert control over critical cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and survival, thereby contributing significantly to the clonogenicity and maintenance of BCSC populations within the tumors [244,245]. Their dysregulation or aberrant activity can drive therapy resistance and induce MRD, subsequent expansion and recurrence. Insights into the regulatory networks governed by these PTFs may provide valuable avenues for the development of novel strategies aimed at disrupting BCSC-mediated tumorigenesis and improving patient outcomes.

- Cytokines in the TME: Within the TME, the cytokine storm can drive the behavior of BCSCs, and they may oscillate between cancer stemness and bulk tumor cell states. Interleukins (ILs), such as IL-6 and IL-8 (CXCL8) C-X-C chemokine ligand 8, along with tumor necrosis factor a (TNF-a) and transforming growth factor b (TGF-b), represent key players in this regulatory network [80,246]. These cytokines from the TME exert a paracrine effect on BCSCs, influencing their survival, clonogenic expansion, survival, and migration. By engaging with specific receptors and initiating downstream signaling pathways, cytokines and chemokines modulate the gene expression associated with cancer stemness, plasticity, and chemoresistance in BCSCs [240]. Thus, the niche for BCSCs in the TME can foster their survival, clonogenicity and maintenance [247]. Co-targeting the cytokine signaling network may augment targeted therapies.

- Stromal cells within the TME: A dynamic interplay exists between stromal cell compartments comprising of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), endothelial cells, immune cells, acellular extracellular matrices (ECM) and the BCSCs [248]. CAFs, through the secretion of growth factors and cytokines, create a supportive niche for BCSCs, enhancing their maintenance and self-renewal capabilities [240]. Endothelial cells contribute to BCSC survival and proliferation by facilitating neoangiogenesis and providing nourishment. The immune cells, such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) and regulatory T lymphocytes (Treg), secrete factors that promote BCSC stemness [249]. This bi-directional communication between stromal and cancer cells (bulk tumor cells and BCSCs) enables the sustenance of cancer stemness and clonogenicity. Uncovering the supportive roles of the TME for BCSCs holds promise for developing novel therapeutic interventions aimed at disrupting BCSC-mediated tumorigenesis, metastasis, and drug resistance.

- Hypoxic TME: The role of hypoxia in BC has been discussed in earlier sections. HIFs activate a cascade of events within BCSCs, promoting their maintenance, enhancing their plasticity and promoting resistance to therapy. Through transcriptional activation of target genes involved in angiogenesis, metabolism, and cell survival, HIFs create a microenvironment conducive to BCSC survival and clonal expansion under hypoxic stress [250,251]. This hypoxia-driven adaptation confers a selective advantage to BCSCs, facilitating their persistence. Understanding the interplay between hypoxia, HIFs, and BCSC holds promising therapeutic potential for targeting aggressive and refractory tumors.

- Metabolic reprogramming: A subset of BCSCs (called energetic BCSCs) display an increase in glucose uptake, a high glycolytic rate through the Warburg effect that results in lactate accumulation, and a concurrent decrease in mitochondrial respiration [253]. Recent evidence suggests that BCSCs can alternate between glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in the presence of oxygen, facilitating incessant tumor growth. This metabolic plasticity allows BCSCs to engage in OXPHOS generating ATP, thus promoting survival under conditions where glycolysis is impaired [254]. Interestingly, proliferative BCSCs prefer the OXPHOS metabolism, while quiescent BCSCs are dependent on glycolysis for their metabolism [255,256]. In addition, BCSCs have also been reported to rely on mitochondrial fatty acid oxi[28]dation as an alternative energy source to maintain their survival, self-renewal, and chemoresistance [257]. This metabolic adaptability makes them less vulnerable to many therapies targeting specific metabolic pathways. However, a combination therapy targeting more than one metabolic pathway may disrupt the availability of an array of metabolic mechanisms at the disposal of BCSCs.

Additional Strategies for Targeting BCSCs

BCSCs in Hormone Receptor-Positive BC

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | African American |

| ABCs | ATP binding cassettes |

| ABCB1 | ATP binding cassette B1 |

| ABCG2 | ATP binding cassette G2 |

| ABL | Abelson leukemia |

| Ago2 | Argonaute 2 |

| AhR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| ALDHs | Aldehyde dehydrogenases |

| ALDH1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 |

| ALDH1A1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 |

| APC | Adenomatous polyposis coli |

| AP-1 | Activator protein 1 |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BC | BC |

| BCRP | BC resistance protein |

| BCSCs | BC stem-like cells |

| BET | Bromodomain extra-terminal domain |

| BIRC5 | Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5 |

| BL1 | Basal-like 1 |

| BL2 | Basal-like 2 |

| BRCA1 | Breast cancer gene 1 |

| CAFs | Cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| CCL21 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 21 |

| CCR7 | C-C chemokine receptor type 7 |

| CD | Cluster of differentiation |

| CD24 | Cluster of differentiation 24 |

| CD44 | Cluster of differentiation 44 |

| CD49f | Cluster of differentiation 49f |

| CD133 | Cluster of differentiation 133 |

| CEACAM1 | carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase 2 |

| CREB | cyclic AMP response element-binding protein |

| CSC | Cancer stem cell |

| CXCR1 | C-X-C chemokine receptor 1 |

| CXCR2 | C-X-C chemokine receptor 2 |

| CXCR4 | C-X-C chemokine receptor 4 |

| CXCL8 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 |

| c-MYC | cellular myelocytomatosis |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DOT1L | Disruptor of telomeric silencing 1 |

| d-TPP | Dodecyl(triphenyl)phosphonium |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| eIF4A1 | Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A1 |

| eIF4B | Eukaryotic initiation factor 4B |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| EpCAM | Epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ERK | Extracellular signal regulated kinase |

| EW | European White |

| FGF9 | Fibroblast growth factor9 |

| Fz | Frizzled receptor |

| GLI1 | Glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor2 |

| HIFs | Hypoxia Inducible factors |

| HIF-1a | Hypoxia inducible factor 1a |

| HIF-2a | Hypoxia inducible factor 2a |

| HMGA1 | High mobility group A1 |

| HRE | Hypoxia response element |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| Ils | Interleukins |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 |

| IRF | Interferon regulatory factor |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| JAK2 | Janus kinase2 |

| JAM-A | Junctional adhesion molecule A |

| KLF4 | Kruppel-like factor 4 |

| KLF5 | Kruppel-like factor 5 |

| LAR | Luminal androgen receptor |

| LASP1 | LIM and SH3 protein 1 |

| LATS1/2 | Large tumor suppressor 1 and 2 |

| LRP6 | Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 |

| M | Mesenchymal |

| MAPK | Mitogen activated protein kinase |

| MAP4K | Mitogen activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinases |

| MCL1 | Myeloid cell leukemia 1 |

| MDM2 | Mouse double minute 2 homolog |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| miRNAs | MicroRNAs |

| MOB1 A/B | Monopolar spindle (mps1) binder 1 A/B |

| MRD | Minimal residual disease |

| mRNAs | Messenger RNAs |

| MSI1 | Musashi RNA binding protein 1 |

| MST1/2 | Mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1/2 |

| mTNBC | Metastatic triple-negative BC |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| mTORC1 | Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| NACT | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

| NF-kB | Nuclear factor kappa of B lymphocytes |

| Notch 1-4 | Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 1-4 |

| OCT4 | Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 |

| OSKM | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| PCP | planar cell polarity |

| pCR | Pathological complete response |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death ligand 1 |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase |

| PR | Progesterone receptor |

| PTEN | Phosphate and tensin homolog |

| PTFs | Pluripotent transcription factors |

| P-gp | P-glycoprotein |

| RANKL | receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| ROCK1 | Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1 |

| ROR1 | Receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RSKs | Ribosomal S6 kinases |

| SAV1 | Salvador homolog 1 |

| SERDs | Selective estrogen receptor degraders |

| SETRMs | Selective estrogen receptor modulators |

| SH3 | Src homology 3 |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| SMIs | Small molecule inhibitors |

| SMO | Smoothened receptor |

| SOX2 | SRY (sex determining region Y)-box2 |

| SOX9 | SRY (sex determining region Y)-box9 |

| SRF | Serum response factor |

| STAT3 | Signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TAOKs | Thousand and one kinases |

| TAZ | Transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif |

| Tbx3 | T-box transcription factor3 |

| TCF | T-cell factor |

| tDRs | Transfer RNA-derived small non-coding RNAs |

| TEAD 1-4 | Transcriptional enhancer associate domain 1-4 |

| TF | Transcription factors |

| TGF-b | Transforming growth factor b |

| TILs | Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TKIs | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| TNBC | Triple-negative BC |

| TNF-a | Tumor necrosis factor a |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TPP | Target product profile |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cells |

| Twist1 | Twist family BHLH transcription factor 1 |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VM | Vascular mimicry |

| WASP | Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein |

| WAVE3 | WASP-family verprolin-homologous protein |

| Wnt | Wingless-related integration site |

| WWTR1 | WW-domain-containing transcription regulator 1 |

| YAP | Yes-associated protein |

| YB-1 | Y-box binding protein 1 |

| (ΔNp63) | Delta N Isoform of Tumor Protein 63 |

References

- Brooks, M.D.; Burness, M.L.; Wicha, M.S. Therapeutic Implications of Cellular Heterogeneity and Plasticity in Breast Cancer. Cell stem cell 2015, 17, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, S.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, R.; Sun, K.; Zeng, H.; Zhou, J.; Wei, W. Global patterns of breast cancer incidence and mortality: A population-based cancer registry data analysis from 2000 to 2020. Cancer Commun. (Lond) 2021, 41, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucalp, A.; Traina, T.A.; Eisner, J.R.; Parker, J.S.; Selitsky, S.R.; Park, B.H.; Elias, A.D.; Baskin-Bey, E.S.; Cardoso, F. Male breast cancer: a disease distinct from female breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 173, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hajj, M.; Wicha, M.S.; Benito-Hernandez, A.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 3983–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagami, P.; Carey, L.A. Triple negative breast cancer: Pitfalls and progress. NPJ Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, A.M.; Hoadley, K.A.; Troester, M.A. Race and Ancestry in Immune Response to Breast Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 2496–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.P.; Roth, A.; Goya, R.; Oloumi, A.; Ha, G.; Zhao, Y.; Turashvili, G.; Ding, J.; Tse, K.; Haffari, G.; et al. The clonal and mutational evolution spectrum of primary triple-negative breast cancers. Nature 2012, 486, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, I.A.; Abramson, V.G.; Lehmann, B.D.; Pietenpol, J.A. New strategies for triple-negative breast cancer--deciphering the heterogeneity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, B.D.; Bauer, J.A.; Chen, X.; Sanders, M.E.; Chakravarthy, A.B.; Shyr, Y.; Pietenpol, J.A. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2750–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B.D.; Jovanovic, B.; Chen, X.; Estrada, M.V.; Johnson, K.N.; Shyr, Y.; Moses, H.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Pietenpol, J.A. Refinement of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes: Implications for Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Selection. PloS one 2016, 11, e0157368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaayvaz, M.; Cristea, S.; Gillespie, S.M.; Patel, A.P.; Mylvaganam, R.; Luo, C.C.; Specht, M.C.; Bernstein, B.E.; Michor, F.; Ellisen, L.W. Unravelling subclonal heterogeneity and aggressive disease states in TNBC through single-cell RNA-seq. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Current Treatment Landscape for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC). J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Qiu, Q.; Khanna, A.; Todd, N.W.; Deepak, J.; Xing, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Su, Y.; Stass, S.A.; et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a tumor stem cell-associated marker in lung cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2009, 7, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Mukherjee, P.; Chatterjee, R.; Jamal, Z.; Chatterji, U. Enhancing Chemosensitivity of Breast Cancer Stem Cells by Downregulating SOX2 and ABCG2 Using Wedelolactone-encapsulated Nanoparticles. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, J.; Ahn, J.H.; Park, J.M.; Choi, S.B.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, H.S.; Kim, S.I.; Park, B.W.; Park, S. Distinct Prognosis of Minimal Residual Disease According to Breast Cancer Subtype in Patients with Breast or Nodal Pathologic Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 7060–7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Harano, K.; Miura, S.; Wang, Y.; Hirota, Y.; Harada, O.; Jolly, M.K.; Matsunaga, Y.; Lim, B.; Wood, A.L.; et al. Changes in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes in Patients Without Pathologic Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Systemic Chemotherapy. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, e2000368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Zoubeidi, A.; Beltran, H.; Selth, L.A. The Transcriptional and Epigenetic Landscape of Cancer Cell Lineage Plasticity. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 1771–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Vázquez, G.; Gámez-Pozo, A.; Trilla-Fuertes, L.; Arevalillo, J.M.; Zapater-Moros, A.; Ferrer-Gómez, M.; Díaz-Almirón, M.; López-Vacas, R.; Navarro, H.; Maín, P.; et al. A novel approach to triple-negative breast cancer molecular classification reveals a luminal immune-positive subgroup with good prognoses. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wein, L.; Savas, P.; Luen, S.J.; Virassamy, B.; Salgado, R.; Loi, S. Clinical Validity and Utility of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Routine Clinical Practice for Breast Cancer Patients: Current and Future Directions. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.; Rugo, H.S.; Cescon, D.W.; Im, S.A.; Yusof, M.M.; Gallardo, C.; Lipatov, O.; Barrios, C.H.; Perez-Garcia, J.; Iwata, H.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; Bergh, J.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R.; Harbeck, N.; et al. Pembrolizumab for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulal, D.; Boring, A.; Terrero, D.; Johnson, T.; Tiwari, A.K.; Raman, D. Tackling of Immunorefractory Tumors by Targeting Alternative Immune Checkpoints. Cancers 2023, 15, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Cui, H.; Xiao, S.; Dong, L.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Xin, M.; Zhi, H.; Liu, C.; et al. The landscape of immune checkpoint-related long non-coding RNAs core regulatory circuitry reveals implications for immunoregulation and immunotherapy responses. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliou, V.; Vasiliou, K.; Nebert, D.W. Human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family. Hum. Genom. 2009, 3, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, M.; Moitra, K.; Allikmets, R. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. Hum. Mutat. 2022, 43, 1162–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Liang, X.J. Overcoming drug efflux-based multidrug resistance in cancer with nanotechnology. Chin. J. Cancer 2012, 31, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.J.; Gong, L.H.; Zheng, F.Y.; Cheng, K.J.; Chen, Z.S.; Shi, Z. Triterpenoids as reversal agents for anticancer drug resistance treatment. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Aziz, Y.S.; Spillane, A.J.; Jansson, P.J.; Sahni, S. Role of ABCB1 in mediating chemoresistance of triple-negative breast cancers. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherlach, K.S.; Roepe, P.D. “Drug resistance associated membrane proteins”. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, R.; Daumar, P.; Mounetou, E.; Aubel, C.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Abrial, C.; Vatoux, C.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Bamdad, M. BCRP and P-gp relay overexpression in triple negative basal-like breast cancer cell line: a prospective role in resistance to Olaparib. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, R.; Luk, F.; Bebawy, M. Inhibition of the multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein: time for a change of strategy? Drug Metab. Dispos. 2014, 42, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathy Abd-Ellatef, G.E.; Gazzano, E.; Chirio, D.; Hamed, A.R.; Belisario, D.C.; Zuddas, C.; Peira, E.; Rolando, B.; Kopecka, J.; Assem Said Marie, M.; et al. Curcumin-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Bypass P-Glycoprotein Mediated Doxorubicin Resistance in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, N.; Bivona, T.G. Polytherapy and Targeted Cancer Drug Resistance. Trends Cancer 2019, 5, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedeljkovic, M.; Damjanovic, A. Mechanisms of Chemotherapy Resistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer-How We Can Rise to the Challenge. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zou, Y.; Liang, J.Y.; Xiao, W.; Yang, A.; Meng, T.; Lu, S.; Luo, Z.; Xie, X. Identification and validation of a combined hypoxia and immune index for triple-negative breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 2814–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, C.; Barsoum, I.; Kim, J.; Black, M.; Siemens, R.D. Mechanisms Of Hypoxia-Induced Immune Escape In Cancer And Their Regulation By Nitric Oxide. Redox Biol. 2015, 5, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Yang, F.; Shao, C.; Wei, K.; Xie, M.; Shen, H.; Shu, Y. Role of hypoxia in cancer therapy by regulating the tumor microenvironment. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Cunha, R.R.; Murry, D.J.; An, G. Nilotinib Alters the Efflux Transporter-Mediated Pharmacokinetics of Afatinib in Mice. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 3434–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, J.T.; Ganguly, S.S.; Bennett, H.; Friend, J.W.; Tepe, J.; Plattner, R. Imatinib reverses doxorubicin resistance by affecting activation of STAT3-dependent NF-κB and HSP27/p38/AKT pathways and by inhibiting ABCB1. PLoS One 2013, 8, e55509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Huang, Y.H.; Chen, J.L. Understanding and targeting cancer stem cells: therapeutic implications and challenges. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Yang, C.; Zheng, J.; Wang, M.; Chen, M.; Le, D.Q.S.; Kjems, J.; Bunger, C.E. Enhanced efficacy of chemotherapy for breast cancer stem cells by simultaneous suppression of multidrug resistance and antiapoptotic cellular defense. Acta Biomater. 2015, 28, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugano, R.; Ramachandran, M.; Dimberg, A. Tumor angiogenesis: causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 1745–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, M.; Mousa, S.A. The Role of Angiogenesis in Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Dhar, S.; Ray, B.K. Control of VEGF expression in triple-negative breast carcinoma cells by suppression of SAF-1 transcription factor activity. Mol. Cancer Res. 2011, 9, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linderholm, B.K.; Hellborg, H.; Johansson, U.; Elmberger, G.; Skoog, L.; Lehtiö, J.; Lewensohn, R. Significantly higher levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and shorter survival times for patients with primary operable triple-negative breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, 1639–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, S.F. The role of VEGF in triple-negative breast cancer: where do we go from here? Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, 1615–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.U.; Cho, H.M.; Das, R.; Gil-Henn, H.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Al Bayati, A.; Carroll, S.F.; Zhang, Y.; Sankar, A.P.; Elledge, C.; et al. Inhibition of Vasculogenic Mimicry and Angiogenesis by an Anti-EGFR IgG1-Human Endostatin-P125A Fusion Protein Reduces Triple Negative Breast Cancer Metastases. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urru, S.A.M.; Gallus, S.; Bosetti, C.; Moi, T.; Medda, R.; Sollai, E.; Murgia, A.; Sanges, F.; Pira, G.; Manca, A.; et al. Clinical and pathological factors influencing survival in a large cohort of triple-negative breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, F.M.; Olopade, O.I. Epidemiology of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Review. Cancer J. 2021, 27, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietze, E.C.; Sistrunk, C.; Miranda-Carboni, G.; O’Regan, R.; Seewaldt, V.L. Triple-negative breast cancer in African-American women: disparities versus biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, R.; Trudeau, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Hanna, W.M.; Kahn, H.K.; Sawka, C.A.; Lickley, L.A.; Rawlinson, E.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 4429–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, R.L.; Updike, K.L.; Factor, R.E.; Henry, N.L.; Boucher, K.M.; Bernard, P.S.; Varley, K.E. A Multigene Assay Determines Risk of Recurrence in Patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 3466–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.L.B.; Gradishar, W.J. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Current Practice and Future Directions. J. Oncol. Pract. 2017, 13, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Brok, W.D.; Speers, C.H.; Gondara, L.; Baxter, E.; Tyldesley, S.K.; Lohrisch, C.A. Survival with metastatic breast cancer based on initial presentation, de novo versus relapsed. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 161, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansour, N.M. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Brief Review About Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Signaling Pathways, Treatment and Role of Artificial Intelligence. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 836417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.A.; Guo, W.; Liao, M.J.; Eaton, E.N.; Ayyanan, A.; Zhou, A.Y.; Brooks, M.; Reinhard, F.; Zhang, C.C.; Shipitsin, M.; et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 2008, 133, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassn Mesrati, M.; Syafruddin, S.E.; Mohtar, M.A.; Syahir, A. CD44: A Multifunctional Mediator of Cancer Progression. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altevogt, P.; Sammar, M.; Hüser, L.; Kristiansen, G. Novel insights into the function of CD24: A driving force in cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charafe-Jauffret, E.; Ginestier, C.; Iovino, F.; Wicinski, J.; Cervera, N.; Finetti, P.; Hur, M.H.; Diebel, M.E.; Monville, F.; Dutcher, J.; et al. Breast cancer cell lines contain functional cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity and a distinct molecular signature. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chute, J.P.; Muramoto, G.G.; Whitesides, J.; Colvin, M.; Safi, R.; Chao, N.J.; McDonnell, D.P. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase and retinoid signaling induces the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11707–11712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, W.C.; Lim, C.L. Breast cancer stem cells-from origins to targeted therapy. Stem Cell Investig. 2017, 4, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Clauser, K.R.; Tam, W.L.; Fröse, J.; Ye, X.; Eaton, E.N.; Reinhardt, F.; Donnenberg, V.S.; Bhargava, R.; Carr, S.A.; et al. A breast cancer stem cell niche supported by juxtacrine signalling from monocytes and macrophages. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, P.K.; Kanojia, D.; Liu, X.; Singh, U.P.; Berger, F.G.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H. CD49f and CD61 identify Her2/neu-induced mammary tumor-initiating cells that are potentially derived from luminal progenitors and maintained by the integrin-TGFβ signaling. Oncogene 2012, 31, 2614–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.H.; Calcagno, A.M.; Salcido, C.D.; Carlson, M.D.; Ambudkar, S.V.; Varticovski, L. Brca1 breast tumors contain distinct CD44+/CD24- and CD133+ cells with cancer stem cell characteristics. Breast Cancer Res. 2008, 10, R10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, J.M.; Jordan, C.T. The increasing complexity of the cancer stem cell paradigm. Science 2009, 324, 1670–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmer, J. Breast cancer stem cells: Features, key drivers and treatment options. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 53, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, A.H.; Reipas, K.; Hu, K.; Berns, R.; Firmino, N.; Stratford, A.L.; Dunn, S.E. Inhibition of RSK with the novel small-molecule inhibitor LJI308 overcomes chemoresistance by eliminating cancer stem cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledzka, K.; Schiemann, B.; Schiemann, W.P.; Fox, P.; Plow, E.F.; Sossey-Alaoui, K. The WAVE3-YB1 interaction regulates cancer stem cells activity in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 104072–104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H. Asymmetric Cell Division and Tumor Heterogeneity. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 938685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, S.; Howard, C.M.; Tilley, A.M.C.; Subramaniyan, B.; Tiwari, A.K.; Ruch, R.J.; Raman, D. Novel and Alternative Targets Against Breast Cancer Stemness to Combat Chemoresistance. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Arvinrad, P.; Darley, M.; Laversin, S.A.; Parker, R.; Rose-Zerilli, M.J.J.; Townsend, P.A.; Cutress, R.I.; Beers, S.A.; Houghton, F.D.; et al. The effects of restricted glycolysis on stem-cell like characteristics of breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 23274–23288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridharan, S.; Robeson, M.; Bastihalli-Tukaramrao, D.; Howard, C.M.; Subramaniyan, B.; Tilley, A.M.C.; Tiwari, A.K.; Raman, D. Targeting of the Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4A Against Breast Cancer Stemness. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, D.; Cimpean, A.M.; De Miglio, M.R. Editorial: Drug resistance in breast cancer - mechanisms and approaches to overcome chemoresistance. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1080684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Samant, R.S.; Shevde, L.A. Nonclassical activation of Hedgehog signaling enhances multidrug resistance and makes cancer cells refractory to Smoothened-targeting Hedgehog inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 11824–11833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, D.; Tiwari, A.K. Role of eIF4A1 in triple-negative breast cancer stem-like cell-mediated drug resistance. Cancer Rep. (Hoboken) 2022, 5, e1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Fahrmann, J.F.; Lee, H.; Li, Y.-J.; Tripathi, S.C.; Yue, C.; Zhang, C.; Lifshitz, V.; Song, J.; Yuan, Y.; et al. JAK/STAT3-Regulated Fatty Acid β-Oxidation Is Critical for Breast Cancer Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Chemoresistance. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 136–150.e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-L.; Kuo, Y.-C.; Ho, Y.-S.; Huang, Y.-H. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Current Understanding and Future Therapeutic Breakthrough Targeting Cancer Stemness. Cancers 2019, 11, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandolini, L.; Cristiano, L.; Fidoamore, A.; De Pizzol, M.; Di Giacomo, E.; Florio, T.M.; Confalone, G.; Galante, A.; Cinque, B.; Benedetti, E.; et al. Targeting CXCR1 on breast cancer stem cells: signaling pathways and clinical application modelling. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 43375–43394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilley, A.M.C.; Howard, C.M.; Sridharan, S.; Subramaniyan, B.; Bearss, N.R.; Alkhalili, S.; Raman, D. The CXCR4-Dependent LASP1-Ago2 Interaction in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, D.; Howard, C.M.; Tilley, A.M.C.; Sridharan, S. Cell-Cell Interaction | Chemokine Receptors. In Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry III; 2021; pp. 699–710.

- Butt, E.; Howard, C.M.; Raman, D. LASP1 in Cellular Signaling and Gene Expression: More than Just a Cytoskeletal Regulator. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, C.M.; Bearss, N.; Subramaniyan, B.; Tilley, A.; Sridharan, S.; Villa, N.; Fraser, C.S.; Raman, D. The CXCR4-LASP1-eIF4F Axis Promotes Translation of Oncogenic Proteins in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniyan, B.; Sridharan, S.; MHoward, C.; MC Tilley, A.; Basuroy, T.; de la Serna, I.; Butt, E.; Raman, D. Role of the CXCR4-LASP1 Axis in the Stabilization of Snail1 in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, M.; Krishnamurthy, T.P.; Sola, P. Targeted Drug Therapy to Overcome Chemoresistance in Triple-negative Breast Cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2020, 20, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, T.; Ross, D.D. Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2): its role in multidrug resistance and regulation of its gene expression. Chin. J. Cancer 2012, 31, 73–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.; Ross, D.D.; Nakanishi, T.; Bailey-Dell, K.; Zhou, S.; Mercer, K.E.; Sarkadi, B.; Sorrentino, B.P.; Schuetz, J.D. The stem cell marker Bcrp/ABCG2 enhances hypoxic cell survival through interactions with heme. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 24218–24225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamichi, N.; Morii, E.; Ikeda, J.-i.; Qiu, Y.; Mamato, S.; Tian, T.; Fukuhara, S.; Aozasa, K. Synergistic effect of interleukin-6 and endoplasmic reticulum stress inducers on the high level of ABCG2 expression in plasma cells. Lab. Investig. 2009, 89, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Oviedo, L.; Nuncia-Cantarero, M.; Morcillo-Garcia, S.; Nieto-Jimenez, C.; Burgos, M.; Corrales-Sanchez, V.; Perez-Peña, J.; Győrffy, B.; Ocaña, A.; Galán-Moya, E.M. Identification of a stemness-related gene panel associated with BET inhibition in triple negative breast cancer. Cell. Oncol. 2020, 43, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedeljković, M.; Tanić, N.; Prvanović, M.; Milovanović, Z.; Tanić, N. Friend or foe: ABCG2, ABCC1 and ABCB1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2021, 28, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Yang, C.; Han, L.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.J. Expression of BCRP/ABCG2 Protein in Invasive Breast Cancer and Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2021, 45, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palasuberniam, P.; Yang, X.; Kraus, D.; Jones, P.; Myers, K.A.; Chen, B. ABCG2 transporter inhibitor restores the sensitivity of triple negative breast cancer cells to aminolevulinic acid-mediated photodynamic therapy. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Cano, I.; Adam-Artigues, A.; Lameirinhas, A.; Blandez, J.F.; Candela-Noguera, V.; Rojo, F.; Zazo, S.; Madoz-Gúrpide, J.; Lluch, A.; Bermejo, B.; et al. miR-99a-5p modulates doxorubicin resistance via the COX-2/ABCG2 axis in triple-negative breast cancer: from the discovery to in vivo studies. Cancer Commun. 2022, 42, 1412–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, B.; Zhao, X.; Ma, Y.; Ji, R.; Gu, Q.; Dong, X.; Li, J.; Liu, F.; Jia, X.; et al. Twist1 expression induced by sunitinib accelerates tumor cell vasculogenic mimicry by increasing the population of CD133+ cells in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 2014, 13, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Xiong, G.; Guo, S.; Xu, C.; Xu, R.; Guo, P.; Shu, D. Delivery of Anti-miRNA for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Therapy Using RNA Nanoparticles Targeting Stem Cell Marker CD133. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, P.; Ceccarelli, C.; Berishaj, M.; Chang, Q.; Rajasekhar, V.K.; Perna, F.; Bowman, R.L.; Vidone, M.; Daly, L.; Nnoli, J.; et al. Self-renewal of CD133hi cells by IL6/Notch3 signalling regulates endocrine resistance in metastatic breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.J.; Sun, B.C.; Zhao, X.L.; Zhao, X.M.; Sun, T.; Gu, Q.; Yao, Z.; Dong, X.Y.; Zhao, N.; Liu, N. CD133+ cells with cancer stem cell characteristics associates with vasculogenic mimicry in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene 2013, 32, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, C.; Kuhn, C.; Ditsch, N.; Krebold, R.; Heublein, S.; Mayr, D.; Doisneau-Sixou, S.; Jeschke, U. Strong correlation between N-cadherin and CD133 in breast cancer: role of both markers in metastatic events. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 140, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnoli, F.; Grassilli, S.; Al-Qassab, Y.; Capitani, S.; Bertagnolo, V. CD133 in Breast Cancer Cells: More than a Stem Cell Marker. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 7512632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, S.K.; Roger, E.; Toti, U.; Niu, L.; Ohlfest, J.R.; Panyam, J. CD133-targeted paclitaxel delivery inhibits local tumor recurrence in a mouse model of breast cancer. J. Control. Release 2013, 171, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wu, S.; Barrera, J.; Matthews, K.; Pan, D. The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila Homolog of YAP. Cell 2005, 122, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, F.D.; Gokhale, S.; Johnnidis, J.B.; Fu, D.; Bell, G.W.; Jaenisch, R.; Brummelkamp, T.R. YAP1 increases organ size and expands undifferentiated progenitor cells. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 2054–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calses, P.C.; Crawford, J.J.; Lill, J.R.; Dey, A. Hippo Pathway in Cancer: Aberrant Regulation and Therapeutic Opportunities. Trends Cancer 2019, 5, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, K.F.; Zhang, X.; Thomas, D.M. The Hippo pathway and human cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Feldmann, G.; Huang, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, N.; Comerford, S.A.; Gayyed, M.F.; Anders, R.A.; Maitra, A.; Pan, D. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell 2007, 130, 1120–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, K.F.; Pfleger, C.M.; Hariharan, I.K. The Drosophila Mst ortholog, hippo, restricts growth and cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Cell 2003, 114, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantalacci, S.; Tapon, N.; Leopold, P. The Salvador partner Hippo promotes apoptosis and cell-cycle exit in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 5, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udan, R.S.; Kango-Singh, M.; Nolo, R.; Tao, C.; Halder, G. Hippo promotes proliferation arrest and apoptosis in the Salvador/Warts pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 5, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, R.W.; Zilian, O.; Woods, D.F.; Noll, M.; Bryant, P.J. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene warts encodes a homolog of human myotonic dystrophy kinase and is required for the control of cell shape and proliferation. Genes. Dev. 1995, 9, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Stewart, R.A.; Yu, W. Identifying tumor suppressors in genetic mosaics: the Drosophila lats gene encodes a putative protein kinase. Development 1995, 121, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Jho, E.H. The history and regulatory mechanism of the Hippo pathway. BMB Rep. 2018, 51, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Moroishi, T.; Guan, K.L. Mechanisms of Hippo pathway regulation. Genes. Dev. 2016, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, A.; Varelas, X.; Guan, K.L. Targeting the Hippo pathway in cancer, fibrosis, wound healing and regenerative medicine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 480–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocaterra, A.; Romani, P.; Dupont, S. YAP/TAZ functions and their regulation at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2020, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggiano, J.C.; Vanderzalm, P.J.; Fehon, R.G. Tao-1 phosphorylates Hippo/MST kinases to regulate the Hippo-Salvador-Warts tumor suppressor pathway. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.L.; Lin, J.I.; Zhang, X.; Harvey, K.F. The sterile 20-like kinase Tao-1 controls tissue growth by regulating the Salvador-Warts-Hippo pathway. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, E.H.; Nousiainen, M.; Chalamalasetty, R.B.; Schafer, A.; Nigg, E.A.; Sillje, H.H. The Ste20-like kinase Mst2 activates the human large tumor suppressor kinase Lats1. Oncogene 2005, 24, 2076–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hergovich, A.; Schmitz, D.; Hemmings, B.A. The human tumour suppressor LATS1 is activated by human MOB1 at the membrane. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 345, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furth, N.; Aylon, Y. The LATS1 and LATS2 tumor suppressors: beyond the Hippo pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2017, 24, 1488–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Meng, Z.; Chen, R.; Guan, K.L. The Hippo Pathway: Biology and Pathophysiology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 577–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praskova, M.; Khoklatchev, A.; Ortiz-Vega, S.; Avruch, J. Regulation of the MST1 kinase by autophosphorylation, by the growth inhibitory proteins, RASSF1 and NORE1, and by Ras. Biochem. J. 2004, 381, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, L.R.; Komander, D.; Alessi, D.R. The nuts and bolts of AGC protein kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, K.; Tapon, N. The Salvador-Warts-Hippo pathway - an emerging tumour-suppressor network. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.L.; Fu, V.; Liu, G.; Tang, T.; Konradi, A.W.; Peng, X.; Kemper, E.; Cravatt, B.F.; Franklin, J.M.; Wu, Z.; et al. Hippo pathway regulation by phosphatidylinositol transfer protein and phosphoinositides. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 18, 1076–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.X.; Guan, K.L. The Hippo pathway: regulators and regulations. Genes. Dev. 2013, 27, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, I.; McCollum, D. Control of cellular responses to mechanical cues through YAP/TAZ regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 17693–17706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tang, X.; Nice, E.C.; Huang, C.; Aguilar, M. Hippo signaling in cancer: regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Aust. J. Chem. 2023, 76, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, S.; Jaiswal, P.K.; Vatanmakarian, M.; Yousefi, H.; Sankaralingam, S.; Alahari, S.K.; Koul, S.; Koul, H.K. Hippo pathway: Regulation, deregulation and potential therapeutic targets in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2021, 507, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Totaro, A.; Panciera, T.; Piccolo, S. YAP/TAZ upstream signals and downstream responses. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, S.; Dupont, S.; Cordenonsi, M. The biology of YAP/TAZ: hippo signaling and beyond. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 1287–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.G.; Moroishi, T.; Guan, K.L. YAP and TAZ: a nexus for Hippo signaling and beyond. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Zhou, X. Targeting Hippo signaling in cancer: novel perspectives and therapeutic potential. MedComm (2020) 2023, 4, e375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y. Analysis of the role of the Hippo pathway in cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.S.; Park, H.W.; Guan, K.L. The Hippo signaling pathway in stem cell biology and cancer. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, M.; Hu, Y.; Lan, T.; Guan, K.L.; Luo, T.; Luo, M. The Hippo signalling pathway and its implications in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebio, A.; Lenz, H.J. Molecular Pathways: Hippo Signaling, a Critical Tumor Suppressor. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 5002–5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanconato, F.; Cordenonsi, M.; Piccolo, S. YAP and TAZ: a signalling hub of the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaulk, S.G.; Lattanzi, V.J.; Hiemer, S.E.; Fahlman, R.P.; Varelas, X. The Hippo pathway effectors TAZ/YAP regulate dicer expression and microRNA biogenesis through Let-7. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 1886–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, M.; Triboulet, R.; Mohseni, M.; Schlegelmilch, K.; Shrestha, K.; Camargo, F.D.; Gregory, R.I. Hippo signaling regulates microprocessor and links cell-density-dependent miRNA biogenesis to cancer. Cell 2014, 156, 893–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabine, A.; Bovay, E.; Demir, C.S.; Kimura, W.; Jaquet, M.; Agalarov, Y.; Zangger, N.; Scallan, J.P.; Graber, W.; Gulpinar, E.; et al. FOXC2 and fluid shear stress stabilize postnatal lymphatic vasculature. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 3861–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Luo, J.Y.; Li, B.; Tian, X.Y.; Chen, L.J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Deng, D.; Lau, C.W.; Wan, S.; et al. Integrin-YAP/TAZ-JNK cascade mediates atheroprotective effect of unidirectional shear flow. Nature 2016, 540, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Ai, D.; Yao, L.; Jiang, H. The role of the Hippo pathway in heart disease. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 5819–5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boopathy, G.T.K.; Hong, W. Role of Hippo Pathway-YAP/TAZ Signaling in Angiogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Zheng, Y.; Yin, F.; Yu, J.; Silverman, N.; Pan, D. Toll Receptor-Mediated Hippo Signaling Controls Innate Immunity in Drosophila. Cell 2016, 164, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xie, F.; Chu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, B.; Dai, T.; Gao, L.; Wang, L.; Ling, L.; Jia, J.; et al. YAP antagonizes innate antiviral immunity and is targeted for lysosomal degradation through IKKvarepsilon-mediated phosphorylation. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, L.; Li, X.; Zhou, D.; Geng, J.; Chen, L. Role of Hippo signaling in regulating immunity. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2018, 15, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.M.; Singh, M.K. Emerging roles of the Hippo signaling pathway in modulating immune response and inflammation-driven tissue repair and remodeling. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 4061–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; He, J.; Huang, B.; Liu, S.; Zhu, H.; Xu, T. Emerging role of the Hippo pathway in autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Hong, L.; Ji, S.; Liu, C.; Geng, J.; Zhang, W.; et al. Hippo Signaling Suppresses Cell Ploidy and Tumorigenesis through Skp2. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 669–684 e667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Guan, K.L. Hippo pathway key to ploidy checkpoint. Cell 2014, 158, 695–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reggiani, F.; Gobbi, G.; Ciarrocchi, A.; Sancisi, V. YAP and TAZ Are Not Identical Twins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021, 46, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudol, M. Yes-associated protein (YAP65) is a proline-rich phosphoprotein that binds to the SH3 domain of the Yes proto-oncogene product. Oncogene 1994, 9, 2145–2152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kanai, F.; Marignani, P.A.; Sarbassova, D.; Yagi, R.; Hall, R.A.; Donowitz, M.; Hisaminato, A.; Fujiwara, T.; Ito, Y.; Cantley, L.C.; et al. TAZ: a novel transcriptional co-activator regulated by interactions with 14-3-3 and PDZ domain proteins. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 6778–6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaan, H.Y.K.; Chan, S.W.; Tan, S.K.J.; Guo, F.; Lim, C.J.; Hong, W.; Song, H. Crystal structure of TAZ-TEAD complex reveals a distinct interaction mode from that of YAP-TEAD complex. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battilana, G.; Zanconato, F.; Piccolo, S. Mechanisms of YAP/TAZ transcriptional control. Cell Stress. 2021, 5, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Wei, X.; Li, W.; Udan, R.S.; Yang, Q.; Kim, J.; Xie, J.; Ikenoue, T.; Yu, J.; Li, L.; et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes. Dev. 2007, 21, 2747–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ren, F.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, B.; Jiang, J. The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Dev. Cell 2008, 14, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panciera, T.; Azzolin, L.; Cordenonsi, M.; Piccolo, S. Mechanobiology of YAP and TAZ in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, V.; Sheetz, M. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuFort, C.C.; Paszek, M.J.; Weaver, V.M. Balancing forces: architectural control of mechanotransduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santinon, G.; Pocaterra, A.; Dupont, S. Control of YAP/TAZ Activity by Metabolic and Nutrient-Sensing Pathways. Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Guo, Q.; Shen, P.; Zhen, B.; Qian, X.; et al. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP Pathway by Glucose Sensor O-GlcNAcylation. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 591–604 e595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nokin, M.J.; Durieux, F.; Peixoto, P.; Chiavarina, B.; Peulen, O.; Blomme, A.; Turtoi, A.; Costanza, B.; Smargiasso, N.; Baiwir, D.; et al. Methylglyoxal, a glycolysis side-product, induces Hsp90 glycation and YAP-mediated tumor growth and metastasis. Elife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, G.; Ruggeri, N.; Specchia, V.; Cordenonsi, M.; Mano, M.; Dupont, S.; Manfrin, A.; Ingallina, E.; Sommaggio, R.; Piazza, S.; et al. Metabolic control of YAP and TAZ by the mevalonate pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.; Kim, J.; Jho, E.H. Role of the Hippo pathway and mechanisms for controlling cellular localization of YAP/TAZ. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 5798–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Qian, M.; He, Q.; Zhu, H.; Yang, B. The posttranslational modifications of Hippo-YAP pathway in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2020, 1864, 129397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, K.T.; Yamashita, K.; Sakurai, N.; Ohno, S. The Epithelial Circumferential Actin Belt Regulates YAP/TAZ through Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling of Merlin. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 1435–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, S.; Totty, N.F.; Irwin, M.S.; Sudol, M.; Downward, J. Akt phosphorylates the Yes-associated protein, YAP, to induce interaction with 14-3-3 and attenuation of p73-mediated apoptosis. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.Y.; Zha, Z.Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, W.; Zhao, D.; Li, T.; Chan, S.W.; Lim, C.J.; Hong, W.; et al. The hippo tumor pathway promotes TAZ degradation by phosphorylating a phosphodegron and recruiting the SCFbeta-TrCP E3 ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 37159–37169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Li, L.; Tumaneng, K.; Wang, C.Y.; Guan, K.L. A coordinated phosphorylation by Lats and CK1 regulates YAP stability through SCF(beta-TRCP). Genes. Dev. 2010, 24, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Lv, X.; Liu, C.; Zha, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Lei, Q.Y.; Guan, K.L. The N-terminal phosphodegron targets TAZ/WWTR1 protein for SCFbeta-TrCP-dependent degradation in response to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 26245–26253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.Z.; Bialik, J.F.; Speight, P.; Dan, Q.; Yeung, T.; Szaszi, K.; Pedersen, S.F.; Kapus, A. TGF-beta1 regulates the expression and transcriptional activity of TAZ protein via a Smad3-independent, myocardin-related transcription factor-mediated mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 14902–14920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Tian, X.; Zhang, C.; Miao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Qiu, S.; Wang, H.; Cui, J.; Cao, L.; et al. YAP ISGylation increases its stability and promotes its positive regulation on PPP by stimulating 6PGL transcription. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, F.; Qiao, Y.; Zheng, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Y.; et al. TFCP2 Is Required for YAP-Dependent Transcription to Stimulate Liver Malignancy. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Fischer, R.S.; Pan, D.; Waterman, C.M. YAP Nuclear Localization in the Absence of Cell-Cell Contact Is Mediated by a Filamentous Actin-dependent, Myosin II- and Phospho-YAP-independent Pathway during Extracellular Matrix Mechanosensing. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 6096–6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.; Itoga, K.; Okano, T.; Yonemura, S.; Sasaki, H. Hippo pathway regulation by cell morphology and stress fibers. Development 2011, 138, 3907–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanal, P.; Jia, Z.; Yang, X. Cysteine residues are essential for dimerization of Hippo pathway components YAP2L and TAZ. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben, C.; Wu, X.; Takahashi-Kanemitsu, A.; Knight, C.T.; Hayashi, T.; Hatakeyama, M. Alternative splicing reverses the cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic pro-oncogenic potentials of YAP1. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 13965–13980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbsky, J.; Vinarsky, V.; Perestrelo, A.R.; De La Cruz, J.O.; Martino, F.; Pompeiano, A.; Izzi, V.; Hlinomaz, O.; Rotrekl, V.; Sudol, M.; et al. Evidence for discrete modes of YAP1 signaling via mRNA splice isoforms in development and diseases. Genomics 2021, 113, 1349–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, S.; Panciera, T.; Contessotto, P.; Cordenonsi, M. YAP/TAZ as master regulators in cancer: modulation, function and therapeutic approaches. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, A.; Vera, I.; Diaz, M.P.; Navarro, C.; Rojas, M.; Torres, W.; Parra, H.; Salazar, J.; De Sanctis, J.B.; Bermudez, V. The YAP/TAZ Signaling Pathway in the Tumor Microenvironment and Carcinogenesis: Current Knowledge and Therapeutic Promises. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zou, H.; Guo, Y.; Tong, T.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, P. The oncogenic roles and clinical implications of YAP/TAZ in breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wu, B.K.; Kanchwala, M.; Cai, J.; Wang, L.; Xing, C.; Zheng, Y.; Pan, D. YAP/TAZ drives cell proliferation and tumour growth via a polyamine-eIF5A hypusination-LSD1 axis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, B.J. YAP/TAZ: Drivers of Tumor Growth, Metastasis, and Resistance to Therapy. Bioessays 2020, 42, e1900162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanconato, F.; Cordenonsi, M.; Piccolo, S. YAP/TAZ at the Roots of Cancer. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 783–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanconato, F.; Forcato, M.; Battilana, G.; Azzolin, L.; Quaranta, E.; Bodega, B.; Rosato, A.; Bicciato, S.; Cordenonsi, M.; Piccolo, S. Genome-wide association between YAP/TAZ/TEAD and AP-1 at enhancers drives oncogenic growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Yao, W.; Ying, H.; Hua, S.; Liewen, A.; Wang, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, C.J.; Sadanandam, A.; Hu, B.; et al. Yap1 activation enables bypass of oncogenic Kras addiction in pancreatic cancer. Cell 2014, 158, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, T.; Murakami, H.; Fujii, M.; Ishiguro, F.; Tanaka, I.; Kondo, Y.; Akatsuka, S.; Toyokuni, S.; Yokoi, K.; Osada, H.; et al. YAP induces malignant mesothelioma cell proliferation by upregulating transcription of cell cycle-promoting genes. Oncogene 2012, 31, 5117–5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, J.H.; Plouffe, S.W.; Meng, Z.; Lee, D.H.; Yang, D.; Lim, D.S.; Wang, C.Y.; Guan, K.L. Induction of AP-1 by YAP/TAZ contributes to cell proliferation and organ growth. Genes. Dev. 2020, 34, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Deng, L.; Zou, H.; Guo, Y.; Tong, T.; Huang, M.; Ling, G.; Li, P. New insights into the ambivalent role of YAP/TAZ in human cancers. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Qiu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Geck, R.C.; Tewari, A.K.; Xiao, T.; Font-Tello, A.; Lim, K.; Jones, K.L.; et al. FGFR-inhibitor-mediated dismissal of SWI/SNF complexes from YAP-dependent enhancers induces adaptive therapeutic resistance. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordenonsi, M.; Zanconato, F.; Azzolin, L.; Forcato, M.; Rosato, A.; Frasson, C.; Inui, M.; Montagner, M.; Parenti, A.R.; Poletti, A.; et al. The Hippo transducer TAZ confers cancer stem cell-related traits on breast cancer cells. Cell 2011, 147, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartucci, M.; Dattilo, R.; Moriconi, C.; Pagliuca, A.; Mottolese, M.; Federici, G.; Benedetto, A.D.; Todaro, M.; Stassi, G.; Sperati, F.; et al. TAZ is required for metastatic activity and chemoresistance of breast cancer stem cells. Oncogene 2015, 34, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, L.A.; Squatrito, M.; Northcott, P.; Awan, A.; Holland, E.C.; Taylor, M.D.; Nahle, Z.; Kenney, A.M. Oncogenic YAP promotes radioresistance and genomic instability in medulloblastoma through IGF2-mediated Akt activation. Oncogene 2012, 31, 1923–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Ho, K.C.; Hao, Y.; Yang, X. Taxol resistance in breast cancer cells is mediated by the hippo pathway component TAZ and its downstream transcriptional targets Cyr61 and CTGF. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 2728–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Honjo, S.; Jin, J.; Chang, S.S.; Scott, A.W.; Chen, Q.; Kalhor, N.; Correa, A.M.; Hofstetter, W.L.; Albarracin, C.T.; et al. The Hippo Coactivator YAP1 Mediates EGFR Overexpression and Confers Chemoresistance in Esophageal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 2580–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, A.M.; Tang, C.; Gong, Y.; Bian, J.; Luk, J.M.; Xu, Z.; Chen, J. Overexpression of Yes-associated protein confers doxorubicin resistance in hepatocellullar carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 29, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Xie, L.X.; Zhang, X.Y.; Hu, P.; Long, M.F.; Xiong, F.; Huang, J.; Ye, X.Q. Role of YAP in lung cancer resistance to cisplatin. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 3949–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Jang, S.K.; Hong, S.E.; Park, C.S.; Seong, M.K.; Kim, H.A.; Park, K.S.; Kim, C.H.; Park, I.C.; Jin, H.O. Knockdown of YAP/TAZ sensitizes tamoxifen-resistant MCF7 breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 601, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.D.K.; Yi, C. YAP/TAZ Signaling and Resistance to Cancer Therapy. Trends Cancer 2019, 5, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiso, E.; Migliore, C.; Ciciriello, V.; Morando, E.; Petrelli, A.; Corso, S.; De Luca, E.; Gatti, G.; Volante, M.; Giordano, S. YAP-Dependent AXL Overexpression Mediates Resistance to EGFR Inhibitors in NSCLC. Neoplasia 2017, 19, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, T.; Arang, N.; Wang, Z.; Costea, D.E.; Feng, X.; Goto, Y.; Izumi, H.; Gilardi, M.; Ando, K.; Gutkind, J.S. EGFR Regulates the Hippo pathway by promoting the tyrosine phosphorylation of MOB1. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.F.; Tseng, Y.C.; Nguyen, P.A.; Li, Y.C.; Ho, C.C.; Wu, C.W. Enhanced YAP expression leads to EGFR TKI resistance in lung adenocarcinomas. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coggins, G.E.; Farrel, A.; Rathi, K.S.; Hayes, C.M.; Scolaro, L.; Rokita, J.L.; Maris, J.M. YAP1 Mediates Resistance to MEK1/2 Inhibition in Neuroblastomas with Hyperactivated RAS Signaling. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 6204–6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Sabnis, A.J.; Chan, E.; Olivas, V.; Cade, L.; Pazarentzos, E.; Asthana, S.; Neel, D.; Yan, J.J.; Lu, X.; et al. The Hippo effector YAP promotes resistance to RAF- and MEK-targeted cancer therapies. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Pelissier, F.A.; Zhang, H.; Lakins, J.; Weaver, V.M.; Park, C.; LaBarge, M.A. Microenvironment rigidity modulates responses to the HER2 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib via YAP and TAZ transcription factors. Mol. Biol. Cell 2015, 26, 3946–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, D.R.; Hurst, D.R. Defining the Hallmarks of Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 3011–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.S.A.; Xiao, Y.; Lamar, J.M. YAP/TAZ Activation as a Target for Treating Metastatic Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastushenko, I.; Mauri, F.; Song, Y.; de Cock, F.; Meeusen, B.; Swedlund, B.; Impens, F.; Van Haver, D.; Opitz, M.; Thery, M.; et al. Fat1 deletion promotes hybrid EMT state, tumour stemness and metastasis. Nature 2021, 589, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamar, J.M.; Stern, P.; Liu, H.; Schindler, J.W.; Jiang, Z.G.; Hynes, R.O. The Hippo pathway target, YAP, promotes metastasis through its TEAD-interaction domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2441–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallet-Staub, F.; Marsaud, V.; Li, L.; Gilbert, C.; Dodier, S.; Bataille, V.; Sudol, M.; Herlyn, M.; Mauviel, A. Pro-invasive activity of the Hippo pathway effectors YAP and TAZ in cutaneous melanoma. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ye, L.; Li, Q.; Wu, X.; Wang, B.; Ouyang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Li, J.; Lin, C. Synaptopodin-2 suppresses metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer via inhibition of YAP/TAZ activity. J. Pathol. 2018, 244, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, D.E.; Collins, J.M.; Dawahare, J.H.; Nguyen, T.D.; Lin, Y.; Voytik-Harbin, S.L.; Zorlutuna, P.; Yoder, M.C.; Boerckel, J.D. YAP and TAZ limit cytoskeletal and focal adhesion maturation to enable persistent cell motility. J. Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 1369–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haemmerle, M.; Taylor, M.L.; Gutschner, T.; Pradeep, S.; Cho, M.S.; Sheng, J.; Lyons, Y.M.; Nagaraja, A.S.; Dood, R.L.; Wen, Y.; et al. Platelets reduce anoikis and promote metastasis by activating YAP1 signaling. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, D.C.; Kang, J.H.; Hamza, B.; King, E.M.; Lamar, J.M.; Manalis, S.R.; Hynes, R.O. YAP Enhances Tumor Cell Dissemination by Promoting Intravascular Motility and Reentry into Systemic Circulation. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 3867–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, G.M.; Schmidt, M.O.; Yi, C.; Hu, Z.; Haddad, B.R.; Glasgow, E.; Riegel, A.T.; Wellstein, A. Cell growth density modulates cancer cell vascular invasion via Hippo pathway activity and CXCR2 signaling. Oncogene 2015, 34, 5879–5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.L.; Urtatiz, O.; Van Raamsdonk, C.D. Oncogenic G Protein GNAQ Induces Uveal Melanoma and Intravasation in Mice. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 3384–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.J.; Rouse, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Onaitis, M.W.; Pendergast, A.M. Inactivation of ABL kinases suppresses non-small cell lung cancer metastasis. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e89647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panciera, T.; Azzolin, L.; Fujimura, A.; Di Biagio, D.; Frasson, C.; Bresolin, S.; Soligo, S.; Basso, G.; Bicciato, S.; Rosato, A.; et al. Induction of Expandable Tissue-Specific Stem/Progenitor Cells through Transient Expression of YAP/TAZ. Cell stem cell 2016, 19, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Shin, J.E.; Park, H.W. The Role of Hippo Pathway in Cancer Stem Cell Biology. Mol. Cells 2018, 41, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Chen, Y.; Wan, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, L.; Hu, Q.; Xu, B.; Chernov, M.; et al. Identification of TAZ-Dependent Breast Cancer Vulnerabilities Using a Chemical Genomics Screening Approach. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 673374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, I.; Kim, J.; Okazawa, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, B.; Yu, J.; Chinnaiyan, A.; Israel, M.A.; Goldstein, L.S.; Abujarour, R.; et al. The role of YAP transcription coactivator in regulating stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes. Dev. 2010, 24, 1106–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, K.; Mendoza-Villanueva, D.; Sharan, S.; Summers, G.H.; Dobrolecki, L.E.; Lewis, M.T.; Sterneck, E. C/EBPdelta links IL-6 and HIF-1 signaling to promote breast cancer stem cell-associated phenotypes. Oncogene 2019, 38, 3765–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliopoulos, D.; Hirsch, H.A.; Wang, G.; Struhl, K. Inducible formation of breast cancer stem cells and their dynamic equilibrium with non-stem cancer cells via IL6 secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 1397–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H. Interleukin 6 signaling maintains the stem-like properties of bladder cancer stem cells. Transl. Cancer Res. 2019, 8, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Yang, S.J.; Hwang, D.; Song, J.; Kim, M.; Kyum Kim, S.; Kang, K.; Ahn, J.; Lee, D.; Kim, M.Y.; et al. A basal-like breast cancer-specific role for SRF-IL6 in YAP-induced cancer stemness. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, A.; Goodpaster, T.; Randolph-Habecker, J.; Hoffstrom, B.G.; Jalikis, F.G.; Koch, L.K.; Berger, C.; Kosasih, P.L.; Rajan, A.; Sommermeyer, D.; et al. Analysis of ROR1 Protein Expression in Human Cancer and Normal Tissues. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 3061–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipps, T.J. ROR1: an orphan becomes apparent. Blood 2022, 140, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Ghia, E.M.; Huang, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Lam, S.; Lei, Y.; He, J.; Cui, B.; et al. Inhibition of chemotherapy resistant breast cancer stem cells by a ROR1 specific antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Wu, X. Targeting Transcription Factors in Cancer: From “Undruggable” to “Druggable”. Methods Mol. Biol. 2023, 2594, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baccelli, I.; Schneeweiss, A.; Riethdorf, S.; Stenzinger, A.; Schillert, A.; Vogel, V.; Klein, C.; Saini, M.; Bauerle, T.; Wallwiener, M.; et al. Identification of a population of blood circulating tumor cells from breast cancer patients that initiates metastasis in a xenograft assay. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oku, Y.; Nishiya, N.; Shito, T.; Yamamoto, R.; Yamamoto, Y.; Oyama, C.; Uehara, Y. Small molecules inhibiting the nuclear localization of YAP/TAZ for chemotherapeutics and chemosensitizers against breast cancers. FEBS Open Bio 2015, 5, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagenbeek, T.J.; Zbieg, J.R.; Hafner, M.; Mroue, R.; Lacap, J.A.; Sodir, N.M.; Noland, C.L.; Afghani, S.; Kishore, A.; Bhat, K.P.; et al. An allosteric pan-TEAD inhibitor blocks oncogenic YAP/TAZ signaling and overcomes KRAS G12C inhibitor resistance. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 812–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrash, H.L.; Pendergast, A.M. Multi-Functional Regulation by YAP/TAZ Signaling Networks in Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Cancers 2023, 15, 4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu-Chittenden, Y.; Huang, B.; Shim, J.S.; Chen, Q.; Lee, S.J.; Anders, R.A.; Liu, J.O.; Pan, D. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes. Dev. 2012, 26, 1300–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolcher, A.W.; Lakhani, N.J.; McKean, M.; Lingaraj, T.; Victor, L.; Sanchez-Martin, M.; Kacena, K.; Malek, K.S.; Santillana, S. A phase 1, first-in-human study of IK-930, an oral TEAD inhibitor targeting the Hippo pathway in subjects with advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, TPS3168–TPS3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furet, P.; Bordas, V.; Le Douget, M.; Salem, B.; Mesrouze, Y.; Imbach-Weese, P.; Sellner, H.; Voegtle, M.; Soldermann, N.; Chapeau, E.; et al. The First Class of Small Molecules Potently Disrupting the YAP-TEAD Interaction by Direct Competition. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202200303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macleod, A.R. Abstract ND11: The discovery and characterization of ION-537: A next generation antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of YAP1 in preclinical cancer models. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, ND11–ND11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotiyal, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Breast cancer stem cells, EMT and therapeutic targets. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 453, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkaya, H.; Liu, S.; Wicha, M.S. Breast cancer stem cells, cytokine networks, and the tumor microenvironment. J. Clin. Invest. 2011, 121, 3804–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.; Farzaneh, M. Signaling pathways governing breast cancer stem cells behavior. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Fu, M.; Hu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X.; Luo, M. Regulation and signaling pathways in cancer stem cells: implications for targeted therapy for cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manni, W.; Min, W. Signaling pathways in the regulation of cancer stem cells and associated targeted therapy. MedComm (2020) 2022, 3, e176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Paskeh, M.D.A.; Entezari, M.; Mirmazloomi, S.r.; Hassanpoor, A.; Aboutalebi, M.; Rezaei, S.; Hejazi, E.S.; Kakavand, A.; Heidari, H.; et al. SOX2 function in cancers: Association with growth, invasion, stemness and therapy response. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasti, A.; Mehrazma, M.; Madjd, Z.; Abolhasani, M.; Saeednejad Zanjani, L.; Asgari, M. Co-expression of Cancer Stem Cell Markers OCT4 and NANOG Predicts Poor Prognosis in Renal Cell Carcinomas. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Qin, Y.; Liu, S. Cytokines, breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) and chemoresistance. Clin. Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fico, F.; Santamaria-Martínez, A. The Tumor Microenvironment as a Driving Force of Breast Cancer Stem Cell Plasticity. Cancers 2020, 12, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Nan, F. Breast cancer stromal fibroblasts promote the generation of CD44+CD24- cells through SDF-1/CXCR4 interaction. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 29, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xu, J.; Liu, S. Cancer Stem Cells and Neovascularization. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhi, W.I.; Lu, H.; Samanta, D.; Chen, I.; Gabrielson, E.; Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate pluripotency factor expression by ZNF217- and ALKBH5-mediated modulation of RNA methylation in breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 64527–64542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Lu, H.; Samanta, D.; Salman, S.; Lu, Y.; Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-dependent expression of adenosine receptor 2B promotes breast cancer stem cell enrichment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E9640–E9648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Samanta, D.; Lu, H.; Bullen, J.W.; Zhang, H.; Chen, I.; He, X.; Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia induces the breast cancer stem cell phenotype by HIF-dependent and ALKBH5-mediated m⁶A-demethylation of NANOG mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2016, 113, E2047–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, G.J. Metabolic reprogramming: the emerging concept and associated therapeutic strategies. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 34, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordaz-Ramos, A.; Tellez-Jimenez, O.; Vazquez-Santillan, K. Signaling pathways governing the maintenance of breast cancer stem cells and their therapeutic implications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1221175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Qian, Y.; Yu, J.; Wong, C.C. Metabolic rewiring in the promotion of cancer metastasis: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Oncogene 2020, 39, 6139–6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Dong, Q.Z. Advance in metabolism and target therapy in breast cancer stem cells. World J. Stem Cells 2020, 12, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari Movahed, Z.; Rastegari-Pouyani, M.; Mohammadi, M.H.; Mansouri, K. Cancer cells change their glucose metabolism to overcome increased ROS: One step from cancer cell to cancer stem cell? Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Francesco, E.M.; Sotgia, F.; Lisanti, M.P. Cancer stem cells (CSCs): metabolic strategies for their identification and eradication. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 1611–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francesco, E.M.; Ózsvári, B.; Sotgia, F.; Lisanti, M.P. Dodecyl-TPP Targets Mitochondria and Potently Eradicates Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs): Synergy With FDA-Approved Drugs and Natural Compounds (Vitamin C and Berberine). Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginestier, C.; Hur, M.H.; Charafe-Jauffret, E.; Monville, F.; Dutcher, J.; Brown, M.; Jacquemier, J.; Viens, P.; Kleer, C.G.; Liu, S.; et al. ALDH1 Is a Marker of Normal and Malignant Human Mammary Stem Cells and a Predictor of Poor Clinical Outcome. Cell Stem Cell 2007, 1, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xue, W.; Huang, X.; Yu, X.; Luo, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Bi, Z.; Qiu, X.; Bai, S. Distinct prognostic values of ALDH1 isoenzymes in breast cancer. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 2421–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarvi, S.; Crispin, R.; Lu, Y.; Zeng, L.; Hurley, T.D.; Houston, D.R.; von Kriegsheim, A.; Chen, C.H.; Mochly-Rosen, D.; Ranzani, M.; et al. ALDH1 Bio-activates Nifuroxazide to Eradicate ALDH(High) Melanoma-Initiating Cells. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 1456–1469.e1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurani, H.; Razavipour, S.F.; Harikumar, K.B.; Dunworth, M.; Ewald, A.J.; Nasir, A.; Pearson, G.; Van Booven, D.; Zhou, Z.; Azzam, D.; et al. DOT1L Is a Novel Cancer Stem Cell Target for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 1948–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Brown, R.L.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, P.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Deng, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Gao, X.D.; et al. CD44 splice isoform switching determines breast cancer stem cell state. Genes. Dev. 2019, 33, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.M.; Giltnane, J.M.; Balko, J.M.; Schwarz, L.J.; Guerrero-Zotano, A.L.; Hutchinson, K.E.; Nixon, M.J.; Estrada, M.V.; Sánchez, V.; Sanders, M.E.; et al. MYC and MCL1 Cooperatively Promote Chemotherapy-Resistant Breast Cancer Stem Cells via Regulation of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 633–647.e637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, S.; Srivastava, S.; Terrero, D.; Malla, S.; Tiwari, A.K.; Raman, D. Abstract 4479: Targeting of eIF4A1 curtails lung metastases in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 4479–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Zhai, B.; Yu, Y.; Kiyotsugu, Y.; Raschle, T.; Etzkorn, M.; Seo, H.C.; Nagiec, M.; Luna, R.E.; Reinherz, E.L.; et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis reveals system-wide signaling pathways downstream of SDF-1/CXCR4 in breast cancer stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E2182–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Dulal, D.; Johnson, T.; Raman, D. Role of CXCL12/CXCR4 Axis in the Pathogenesis of Hematological Malignancies. 2024.

- Mehrpouri, M. The contributory roles of the CXCL12/CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in normal and malignant hematopoiesis: A possible therapeutic target in hematologic malignancies. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 920, 174831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillenburg-Pilla, P.; Patel, V.; Mikelis, C.M.; Zárate-Bladés, C.R.; Doçi, C.L.; Amornphimoltham, P.; Wang, Z.; Martin, D.; Leelahavanichkul, K.; Dorsam, R.T.; et al. SDF-1/CXCL12 induces directional cell migration and spontaneous metastasis via a CXCR4/Gαi/mTORC1 axis. Faseb j 2015, 29, 1056–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.D.; Panu, L.; Holm, N.T.; Li, B.D.; Johnson, L.W.; Zhang, S. High chemokine receptor CXCR4 level in triple negative breast cancer specimens predicts poor clinical outcome. J. Surg. Res. 2010, 159, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Peng, X.; Li, X.; Yang, P.; Xie, L.; Li, Y.; Du, C.; Zhang, G. Correction: Silencing of CXCR4 sensitizes triple-negative breast cancer cells to cisplatin. Oncotarget 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubrovska, A.; Hartung, A.; Bouchez, L.C.; Walker, J.R.; Reddy, V.A.; Cho, C.Y.; Schultz, P.G. CXCR4 activation maintains a stem cell population in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells through AhR signalling. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]