1. Introduction

It was pointed out long ago that existence of particles moving faster-than-light in vacuum is not in contradiction with special relativity [

1,

2,

3]. G. Feinberg called these hypothetical particles tachyons [

3]. Generalization of the Lorentz transformation for the region

has been proposed [

4].

Despite many qualms in the physics community and the lack of direct experimental evidence the possibility and implication of tachyons have been a subject of interest among physicists [

5,

6,

7,

8]. For example, it has been claimed that some neutrinos may be tachyons [

9,

10,

11]. In cosmology, tachyons were proposed as a way to model cosmic inflation and dark energy [

12,

13].

If we disregard gravity, the geometry of our spacetime is described by Minkowski metric. In the case of 1+1 dimension the interval reads

which is invariant under Lorentz transformation of coordinates. In Equation (

1) we put

to make the time and the space coordinates have the same units. Physically, the difference between

t and

x appears when we calculate the derivative

along a worldline of a massive particle. If

, we associate

t with the time coordinate and

x with the spatial coordinate. Otherwise

t and

x should be interchanged.

It is tacitly assumed that physical processes can “flow” only unidirectionally with time, from the past into the future, which is chosen as a positive direction of the time axis. This implies that past affects the future, but future can not affect the past. Mathematically, this assumption is formulated as the Cauchy problem which consists of finding solution of the evolution differential equations subject to the initial conditions at some value . In the Cauchy problem, the initial conditions at can be imposed in a way that leaves no possibility for propagation backward in time, breaking the time-reversal invariance of the classical evolution equations.

In this paper we will not restrict our analysis to the Cauchy problem and consider examples with time boundaries for which solution of the evolution equations can be uniquely obtained without specifying initial conditions. We show that there are situations when propagation backward in time occurs and future affects the past. Along spatial coordinates, the physical processes can go in any direction. Then why along the time coordinate they cannot go in both directions as well?

In this paper we consider reflection of a massless scalar field from a “tachyonic" boundary (mirror) that propagates faster than light in vacuum, and impose a boundary condition that the field vanishes at the mirror surface. By making Lorentz transformation one can choose an inertial frame in which the superluminal boundary has the worldline . In this frame, the boundary condition reduces to everywhere in space.

Such Lorentz transformation exists if the boundary moves at a speed greater than speed of light in vacuum

c. For example, a worldline

under Lorentz transformation

where

, transforms into the worldline

.

We will show that one can satisfy the boundary condition only if we allow the reflected field propagate backward in time. This is analogous to reflection from a static mirror for which the boundary condition is satisfied only if the field can move in both directions along the spatial coordinate.

The boundary condition

applies to the problem of light reflection from a moving perfect conductor. Indeed, in the Lorenz gauge, Maxwell’s equations read

where

is the vector potential and

is the electric current density. For the problem of reflection of electromagnetic waves from the surface of a perfect conductor at normal incidence, the vector potential

vanishes at the metal surface. This boundary condition for

(but not for the electric field

) remains valid if the conductor is moving perpendicular to it’s flat surface at any speed.

Thus, in our analysis, the boundary condition models interaction of the field with a perfectly reflecting moving mirror. However, it is not clear how to realize such a boundary condition at a superluminal mirror motion in laboratory experiments since existence of tachyons remains questionable.

One should note that inhomogeneities of the refractive index partially reflect light and behave like mirrors. Reflection and transmission of a light pulse when passing through superluminal inhomogeneities of the refractive index yields interesting phenomena which have been investigated theoretically [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, in these studies, inhomogeneities do not yield the perfectly reflecting boundary condition at the superluminal surface which allows transmission of the pulse through the interface. In this case, one can satisfy the boundary conditions assuming no back in time reflected pulse and two transmitted pulses propagating in the opposite directions.

However, in Sec. III we show that centers of static black holes act like a perfectly reflecting superluminal mirrors if we impose a boundary condition that the field remains finite at the center. This boundary condition implies that the field does not disappear at the black hole center. Hence, the present problem could have applications in astrophysics.

Moreover, in Sec. IV we show that de Sitter spacetime acts as a time mirror provided particles do not disappear from the spacetime at . This problem might be relevant to the early universe because exponential expansion of space during cosmic inflation can be described by the de Sitter metric.

To gain insights into the physics of black hole and de Sitter space geometries in the next Section we consider a fictitious superluminal mirror in Minkowski spacetime. Since there is no evidence that the latter object can exist in nature one can treat the problem as a simplified model of light reflection from the black hole center or the de Sitter space boundary.

2. Reflection of light backward in time from a superluminal mirror

In this Section we consider hypothetical perfectly reflecting superluminal mirrors by imposing the boundary condition at the surface. In this case, there is no transmitted wave. We do not argue that such mirrors can (or cannot) be realized experimentally, but rather study how light is reflected from them. As we show below, backward in time reflection produced by such superluminal mirror yields a possibility to construct a time machine that allows us to send a signal into the past. This leads to logical contradictions associated with time travel paradoxes, which might be an argument against existence of time mirrors. Yet, possibility of new physics cannot be ruled out.

To avoid ambiguities with the field quantization, we consider a classical massless complex scalar field

in 1+1 dimension obeying a wave equation with a source located at the origin of

coordinate system

where

is the Dirac delta function and prime denotes derivative of the delta function with respect to its argument. In this and the following section we put

. Equation (

2) can be obtained by taking variation of the action

with respect to

, where

. Thus, Equation (

2) can describe certain physical models. For example, the source in Equation (

2) can be a two-level atom located at

for which coupling with the field

is suddenly turned on and turned off at

as a delta function

[

19]. From the perspective of the atom, the proper time of the atom determines the positive direction of the time axis

t, and here we adopt this convention.

The general solution of Equation (

2) reads

where

and

are arbitrary functions.

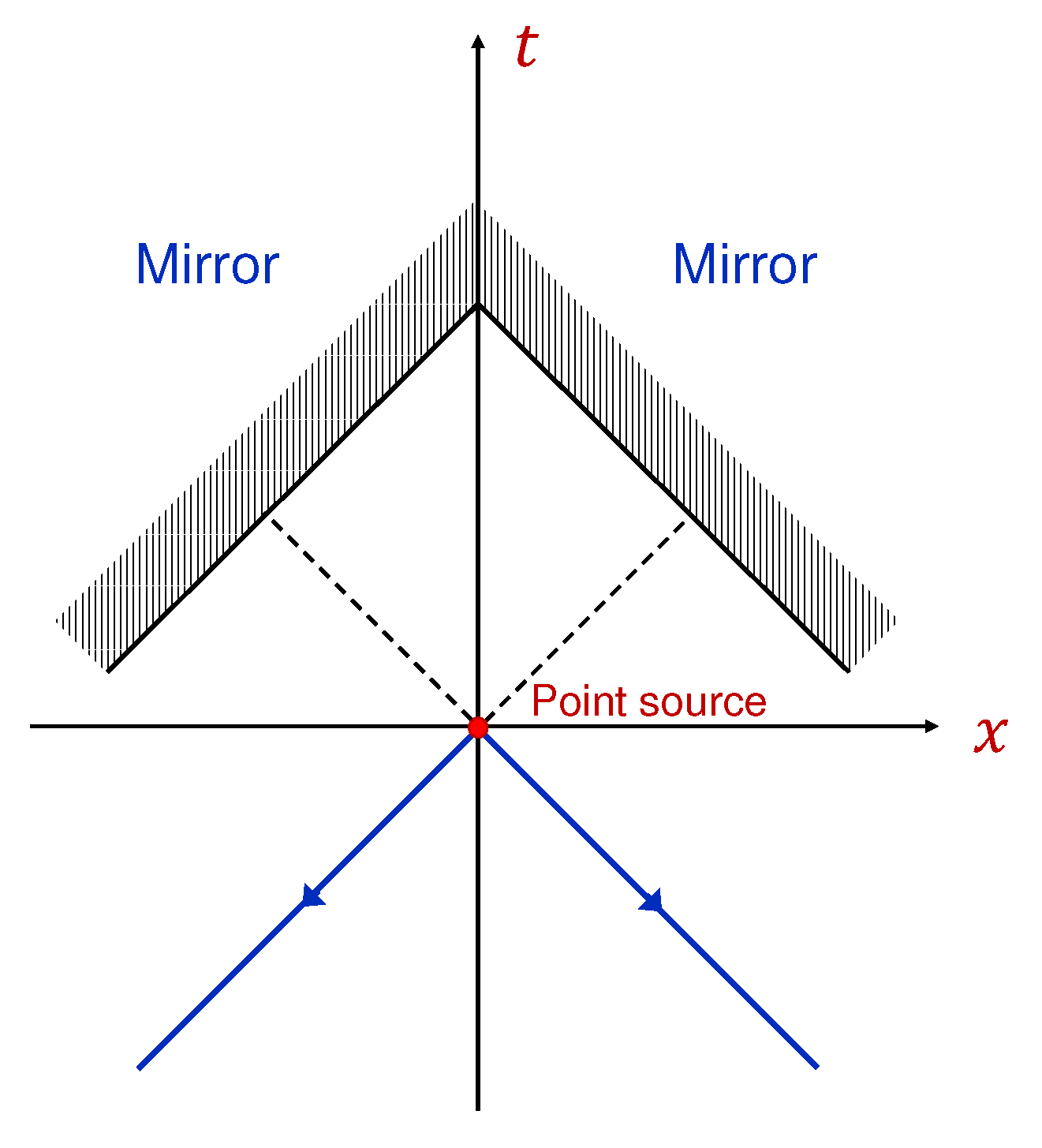

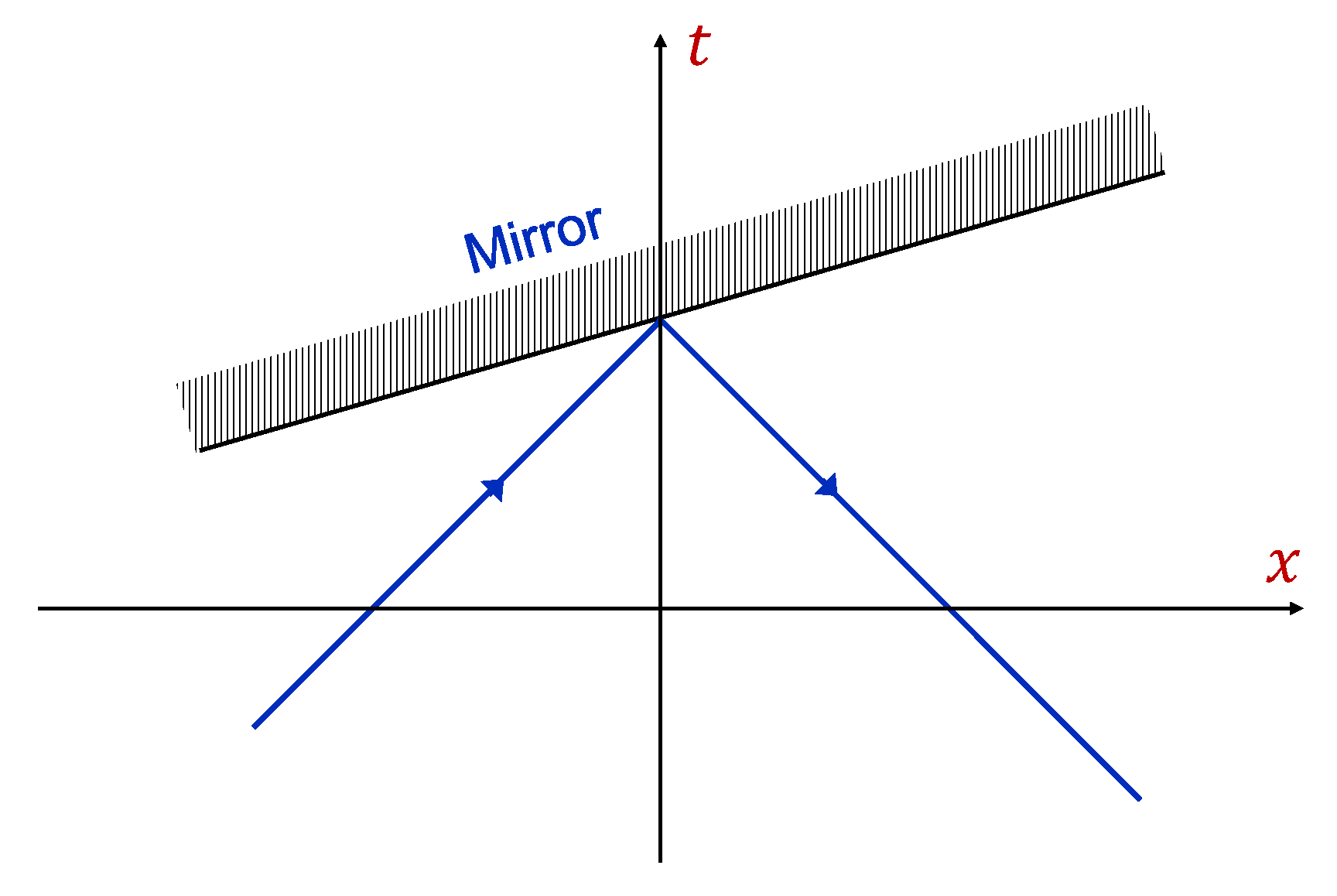

Figure 1.

Point source located at the origin of the Cartesian coordinate system generates two pulses which are reflected from the mirrors propagating at the speed of light. Pulses reflected from the mirrors propagate backward in time.

Figure 1.

Point source located at the origin of the Cartesian coordinate system generates two pulses which are reflected from the mirrors propagating at the speed of light. Pulses reflected from the mirrors propagate backward in time.

As the first example, we consider a situation for which

and

can be obtained uniquely without specifying initial condition for the field. Namely, we assume that there are two hypothetical mirrors propagating with the speed of light along the trajectories (see

Figure 1)

where

. At the position of the mirrors, the field

must vanish, that is

. This boundary condition yields the following constraints on

and

Plug Equations (

5) and (

6) in Equation (

3), gives that solution satisfying the boundary condition at the mirror’s surfaces is unique and is given by

where

is the Heaviside step function. Solution (

7) can be written as

where

is a solution of Equation (

2) with no mirrors which satisfies the “natural” initial condition

, and

Equation (

8) can be interpreted as follows. The point source in the right hand side of Equation (

2) generates two

pulses propagating to the left and to the right toward the mirrors. This is described by the function

. The pulses are then reflected from the mirrors and propagate backward in time, which is described by

. Thus, the mirrors act as time mirrors. In the region

, the incident and reflected pulses cancel each other (

). The net field propagates backward in time from the source into the region

(see

Figure 1). If pulses could propagate only forward in time then in the region

the field must be equal to zero, which is not the case according to the unique solution (

7).

This example demonstrates that presence of the mirrors in the future affects how the source radiates in the past (at ), namely, no field appears in the region . If there are many point sources then none of them would generate field into the future region.

One can also interpret solution (

7) as if two pulses are propagating from

forward in time toward the source and are absorbed by the source. However, in such interpretation, the two pulses are not generated by the source in the right hand side of Equation (

2), which is not the problem we are considering. Moreover, in such interpretation the mirrors play no role because pulses do not reach the mirrors.

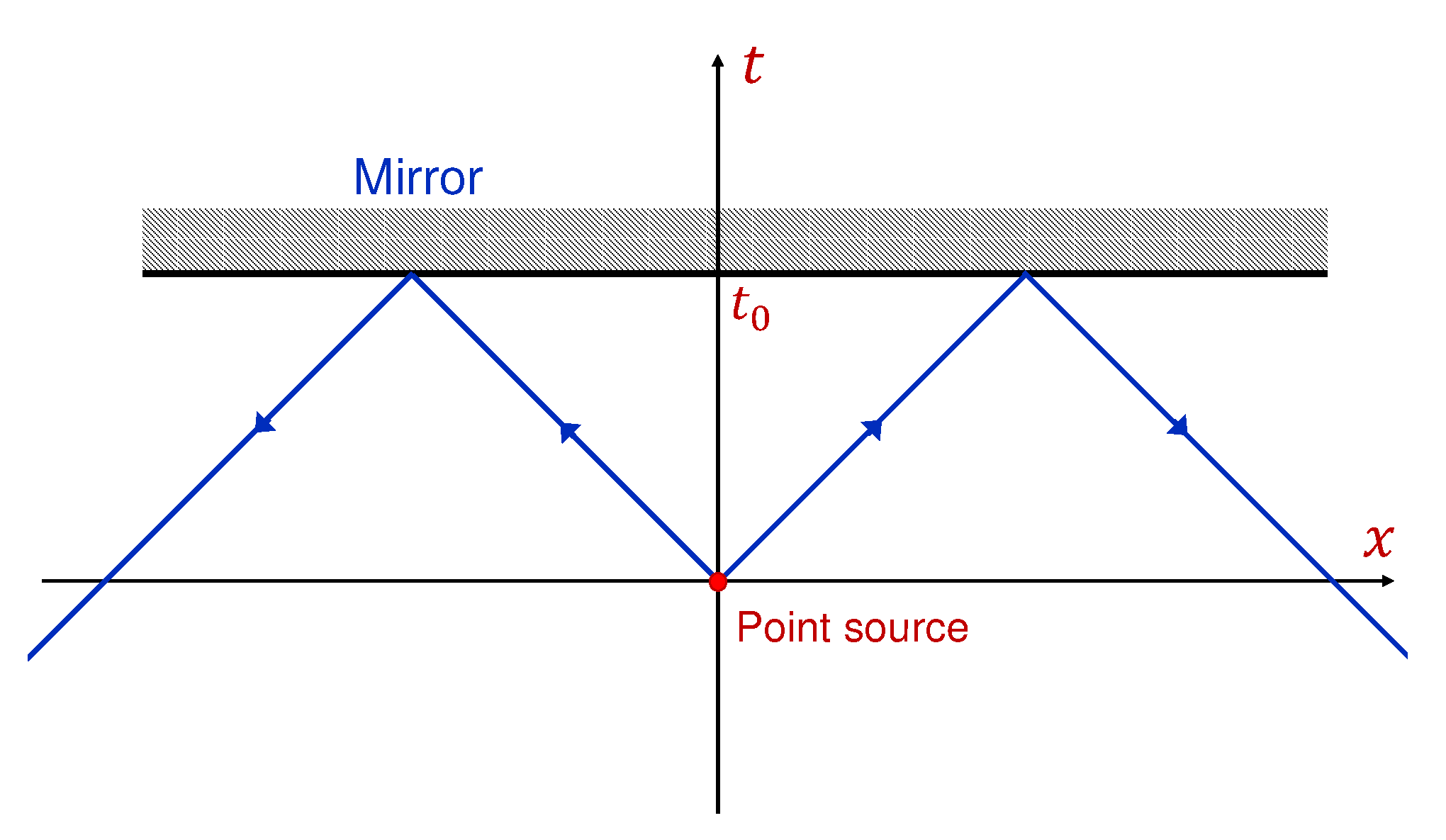

Figure 2.

A point source at the origin of coordinate system generates left and right propagating pulses moving forward in time which are reflected from the mirror at and propagate backward in time.

Figure 2.

A point source at the origin of coordinate system generates left and right propagating pulses moving forward in time which are reflected from the mirror at and propagate backward in time.

In the next example we consider a hypothetical mirror moving along a trajectory

(see

Figure 2). That is field must satisfy the boundary condition

for any

x. Plug this boundary condition into the general solution (

3), yields the following constraint

Symmetry of the problem implies that

. Taking into account that pulse generated by the source in the right hand side of Equation (

2) is a combination of

functions and the pulse trajectory must pass through the source, Equation (

12) gives

where

C is an arbitrary constant. Thus, the general solution of Equation (

2) satisfying the boundary condition (

11) is

The first term in the right hand side of Equation (

13) is a solution of Equation (

2) with no mirror which describes the left and right propagating

pulses generated by the source. Since it is a solution with no mirror, we interpret these

pulses as propagating forward in time. At

, the pulses are reflected from the mirror. Reflection produces

pulses propagating backward in time along the same spacetime trajectory (the second term proportional to

C) and along the reflected trajectory (the last term in Equation (

13)).

In this example, the boundary condition at the mirror surface is not sufficient to specify the value of the integration constant

C. However, for the present geometry, the problem of the field interaction with the mirror is transitionally invariant along the

axis, which yields conservation of the field momentum during reflection. Therefore, we must take

. Then solution (

13) reduces to

which is sketched in

Figure 2. Solution (

14) has the following interpretation. The point source generates left and right propagating

pulses moving forward in time (the first term) which are reflected from the mirror at

and propagate backward in time (the second term).

Thus, the

mirror acts as a time mirror: after reflection from such a mirror the field propagates backward in time. It turns out that any superluminal mirror, with the boundary condition

at the mirror surface, acts as a time mirror. Indeed, let us consider part of the solution (

14) for

, that is

in a moving frame by making the Lorentz transformation of coordinates

where

. In the new coordinates, Equation (

15) becomes

while the mirror is moving along the trajectory

with a superluminal speed

. Solution (

17) is sketched in

Figure 3.

Equation (

17) shows that

pulse produced by the source and propagating forward in time (the first term) is reflected from the superluminal mirror at the spacetime point

and then propagates backward in time (the second term). Thus, superluminal mirrors act as the time mirrors.

Pulses propagating backward in time interact differently with atoms. Namely, such pulses behave as if they have negative energy, and, as a result, ground-state atoms cannot become excited by absorbing them. Instead, the process looks like a ground-state atom becomes excited by emitting a photon. Indeed, the interaction Hamiltonian between a two-level atom located at

and a classical field

reads

where

is the atomic transition frequency,

and

are the atomic lowering and rasing operators,

g is the atom-field coupling constant, and the field

is taken at the atom’s location

. If there is a time mirror at

then the plane-wave modes of the field satisfying the boundary condition

at the mirror surface are

where

is a parameter which we assume to be positive (

). The first term in the right hand side of Equation (

19) describes a plane-wave with positive energy propagating toward the mirror. This wave can yield excitation of the ground-state atom through the term

in the Hamiltonian which becomes time-independent under the resonance condition

. In contrast, the wave reflected from the mirror (the second term in Equation (

19)) cannot excite the atom because the part of the Hamiltonian describing atom’s excitation

is a fast oscillating function of time for any

. If

the reflected wave can yield resonant de-excitation of the excited atom through the term

in the Hamiltonian, which implies that the wave has negative energy.

From the perspective of a subluminal (e.g. fixed in space) observer the field is evolving in the forward direction of the observer’s proper time, and the latter process looks like as if the ground-state atom becomes excited by emitting a negative-energy pulse (photon). One should note that negative-energy photons appear in various physical problems [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. For example, in the reference frame moving faster than speed of light in a medium, photons propagating inside the Cherenkov cone have negative energy [

19,

25]. This leads to Cherenkov radiation. Similar effects occur in the case of surface waves, for example, surface plasmons. In the moving frame, the surface plasmon frequency is Doppler shifted and for large wave numbers the shifted frequency becomes negative. As a result, a ground-state atom moving above a metal surface can become excited by emitting a negative-energy surface plasmon [

26]. The negative energy of the surface plasmon insures energy conservation in the process of atom excitation.

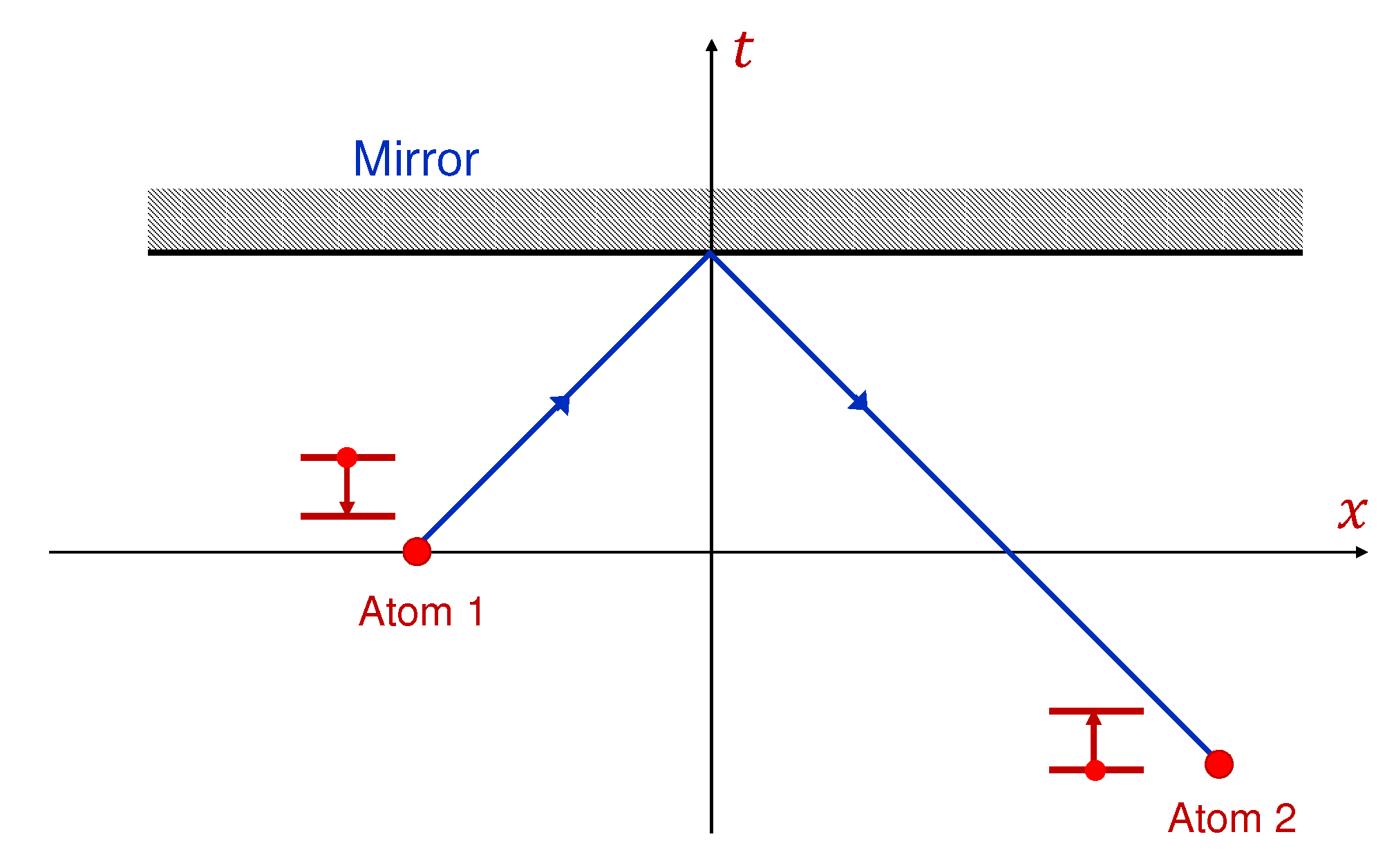

Figure 4.

At time atom 1 emits a photon propagating forward in time. After reflection from the superluminal mirror the photon propagates backward in time and excites atom 2 at .

Figure 4.

At time atom 1 emits a photon propagating forward in time. After reflection from the superluminal mirror the photon propagates backward in time and excites atom 2 at .

Despite similarities, the mentioned negative-energy excitations are different from the pulses propagating backward in time. The latter have negative energy in the lab frame and can violate causality, that is future can affect the past.

Figure 4 shows an excited atom 1 which at time

spontaneously emits a photon propagating forward in time. After reflection from the superluminal mirror (

) the photon propagates backward in time and can excite an atom 2 at

. The process looks like the atom 2 becomes excited by emitting a photon. However, the cause of excitation of the atom 2 is photon emission by the atom 1 at the later moment of time.

One should note that in quantum description of the field, appearance of negative frequencies in the field mode functions (

19) implies particle production. That is superluminal mirror generates photons [

18]. In the present classical treatment this effect does not appear.

Change of the sign of the frequency of a wave reflected from a superluminal mirror can be also understood considering reflection of plane waves. The net field is the sum of the incident (right propagating) and reflected (left propagating) waves with frequencies

and

respectively

where

and

. At the surface of a mirror moving with velocity

V to the left (

) the field vanishes, which yields

Equation (

20) shows that if the mirror is superluminal (

), the frequency of the reflected wave is negative.

3. Black hole center as a superluminal mirror

In this Section we show that centers of static black holes (BHs) act like a perfectly reflecting superluminal mirrors if we impose a boundary condition that the field remains finite at the center. This boundary condition implies that the field does not disappear at the BH center. That is field flux through a sphere of a small radius r vanishes in the limit . After reflection from the BH center, infalling light and matter propagate backward in time and escape from the BH. If true, accreting BHs could be bright, rather than dark objects on the sky.

To gain insight into the effect, we first consider a scalar field

in flat Minkowski spacetime in 3+1 dimension. The field

obeys the wave equation

For spherically symmetric solutions, the origin of the spherical coordinate system

acts as a mirror, where

r is the spherical radial coordinate. Indeed, in spherical coordinates, Equation (

21) reduces to

Introducing a new function

we obtain that

obeys the one-dimensional wave equation

and, according to Equation (

23), it satisfies the mirror-like boundary condition

That is

describes waves propagating in free space with a mirror boundary at

.

Often, for simplicity, spherically symmetric problems in 3+1 dimension are modeled by truncating the spacetime into 1+1 dimension. In this procedure, Equation (

21) is written in 1+1 dimension, which yields

The truncated spacetime is confined into the region

. Equation (

26), however, does not specify the boundary condition for the field

at the spacetime boundary. One can obtain the boundary condition from Equation (

22) in 3+1 dimension by writing it as

Requiring that the field derivatives are finite everywhere, and taking the limit

in Equation (

27), we obtain the boundary condition for

which can be used in the truncated 1+1 dimensional model to mimic spherical symmetry of the original 3+1 dimensional problem. Equations (

26) and (

28) in the truncated spacetime can be mapped into the exact 3+1 dimensional Equations (

24) and (

25) by introducing new function

, which obeys Equations (

24) and (

25). Thus, the truncated spacetime model can catch the essential physics provided we impose the proper boundary condition.

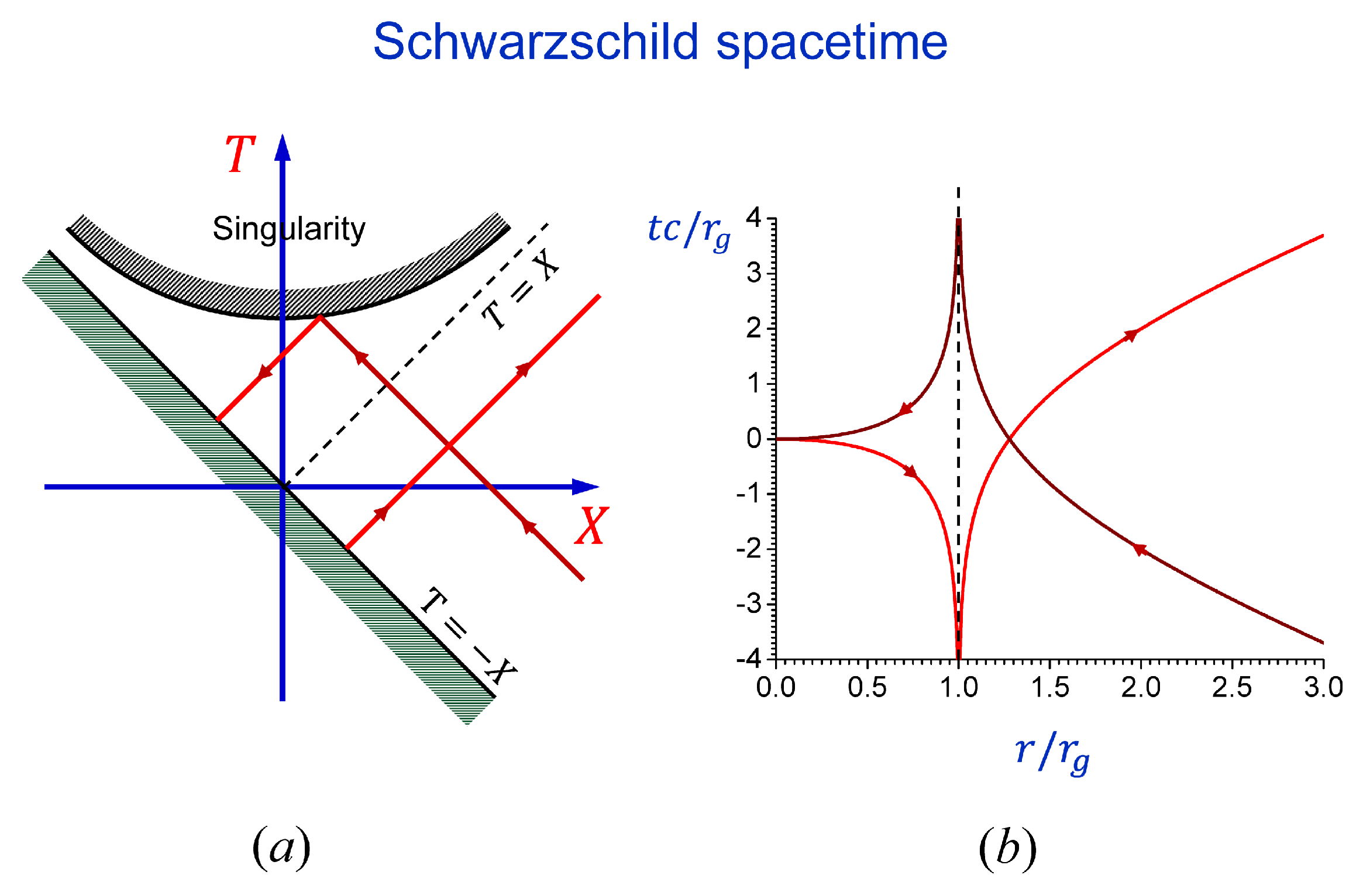

General relativity predicts existence of BHs. An eternal static BH of mass

M in 3+1 dimension in Schwarzschild coordinates is described by the metric

where

is the gravitational radius.

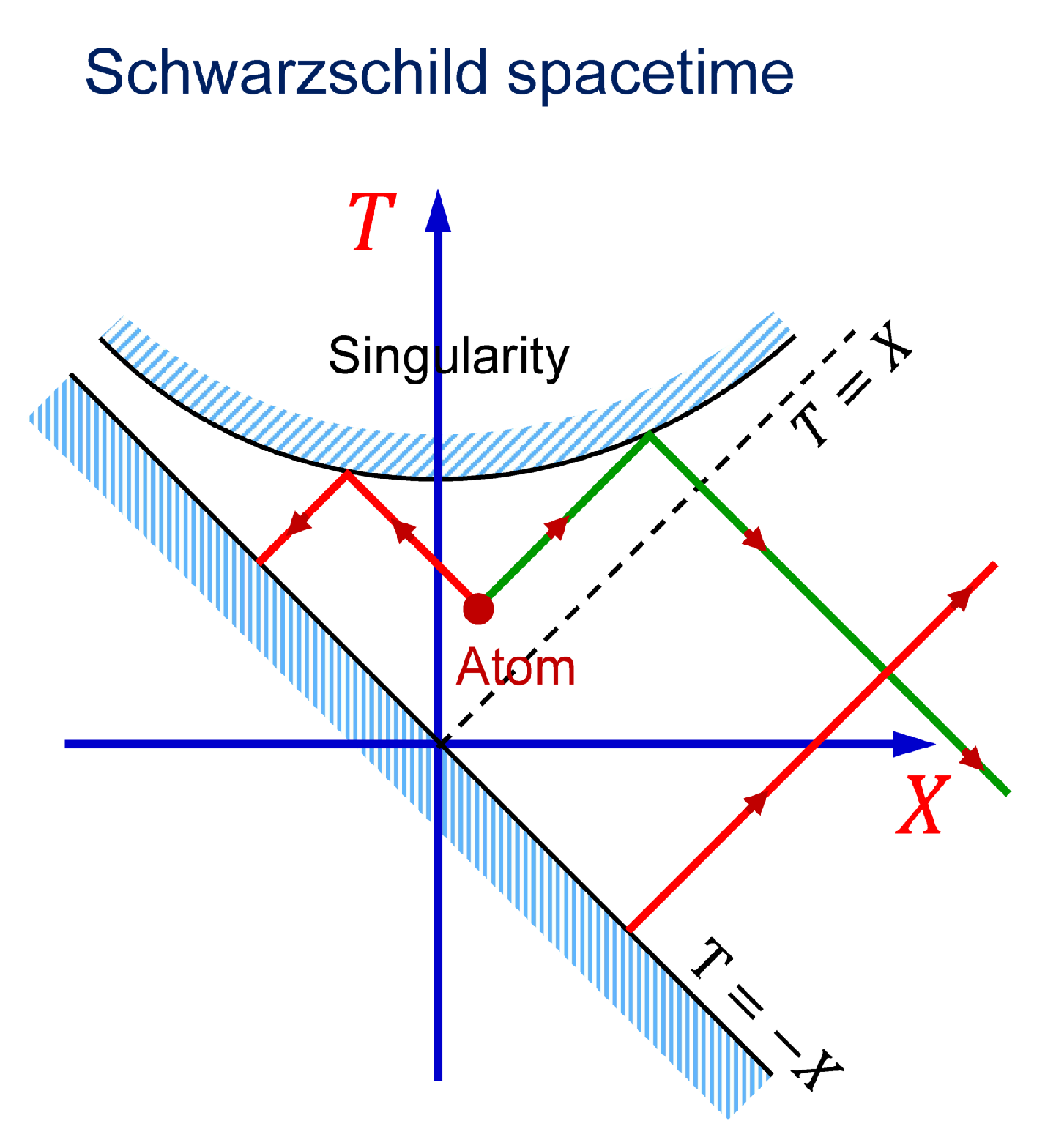

The BH spacetime has an event horizon at . If it would be possible to hold a mirror at fixed r inside the event horizon, such a mirror would act as a time mirror. Next we show that the problem of reflection from the BH center () is mathematically similar to the reflection from a fictitious superluminal mirror in Minkowski spacetime discussed in the previous section.

BHs have a curvature singularity at , which, however, is not responsible for the present effect. Namely, the mirror-like boundary condition at appears due to the spherical symmetry of the 3+1 dimensional problem, while the mirror trajectory is superluminal because it is located inside the event horizon.

Here we consider a massless scalar field

in the Schwarzschild spacetime which obeys the covariant wave equation

where

is the spacetime metric given by the interval (

29), namely

In the following, we will use the gravitational radius as a unit of length, and

as a unit of time. To make the analogy with the superluminal mirror straightforward, we will use Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates that are defined in terms of the Schwarzschild coordinates

t,

r as

for

, and

for

. In these coordinates, the BH center (

) is a space-like line

along which

. The line

sets a boundary of the Schwarzschild spacetime in the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates (see

Figure 5). In these coordinates, the Schwarzschild metric reads

and for a spherically symmetric problem (no dependence on angles

and

), Equation (

30) reduces to

where dependence of

r on

T and

X is given by equation

In contrast to the Schwarzschild coordinates, in the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates, Equation (

34) and the metric (

33) are regular at the BH horizon (

), and, hence, the singular behavior of the metric (

29) at

is a coordinate effect.

3.1. Black hole model in truncated spacetime

If spacetime is truncated to 1+1 dimension,

T and

X, the Schwarzschild metric in the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates is conformally invariant to the Minkowski metric

and the scalar field

obeys the same wave equation as in the Minkowski spacetime

Equation (

37) does not specify the boundary condition for the field

at the spacetime boundary

. As a consequence, many authors have not imposed any boundary condition. This implies that field can freely propagate through the spacetime boundary, as if it is totally absorbed by the BH center (singularity). Usually, the presumption that the BH singularity must absorb everything falling into it, is based on the argument that otherwise the Cauchy problem is not well-defined. However, if we allow propagation backward in time, the problem with the boundary conditions at the superluminal spacetime boundary

becomes well-formulated. That is boundary conditions determine whether propagation backward in time occurs in a particular physical situation.

In a correct treatment, the boundary condition must be properly derived from the equations. The spacetime boundary in the simplified 1+1 dimensional model corresponds to the origin of the spherical coordinates in the exact 3+1 dimensional description. Thus, the boundary condition must be obtained from 3+1 dimensional equations. Taking the limit

in the field equation (

34) in 3+1 dimension, we find the following boundary condition

To obtain Equation (

38) from (

34) we need to assume that

and

are finite at the boundary. Later we will give an exact solution of the problem in 3+1 dimension imposing the boundary condition that the scalar field

must be finite at the boundary, which yields the same solution. The latter condition (finite field) is independent of the coordinate choice since the field is scalar.

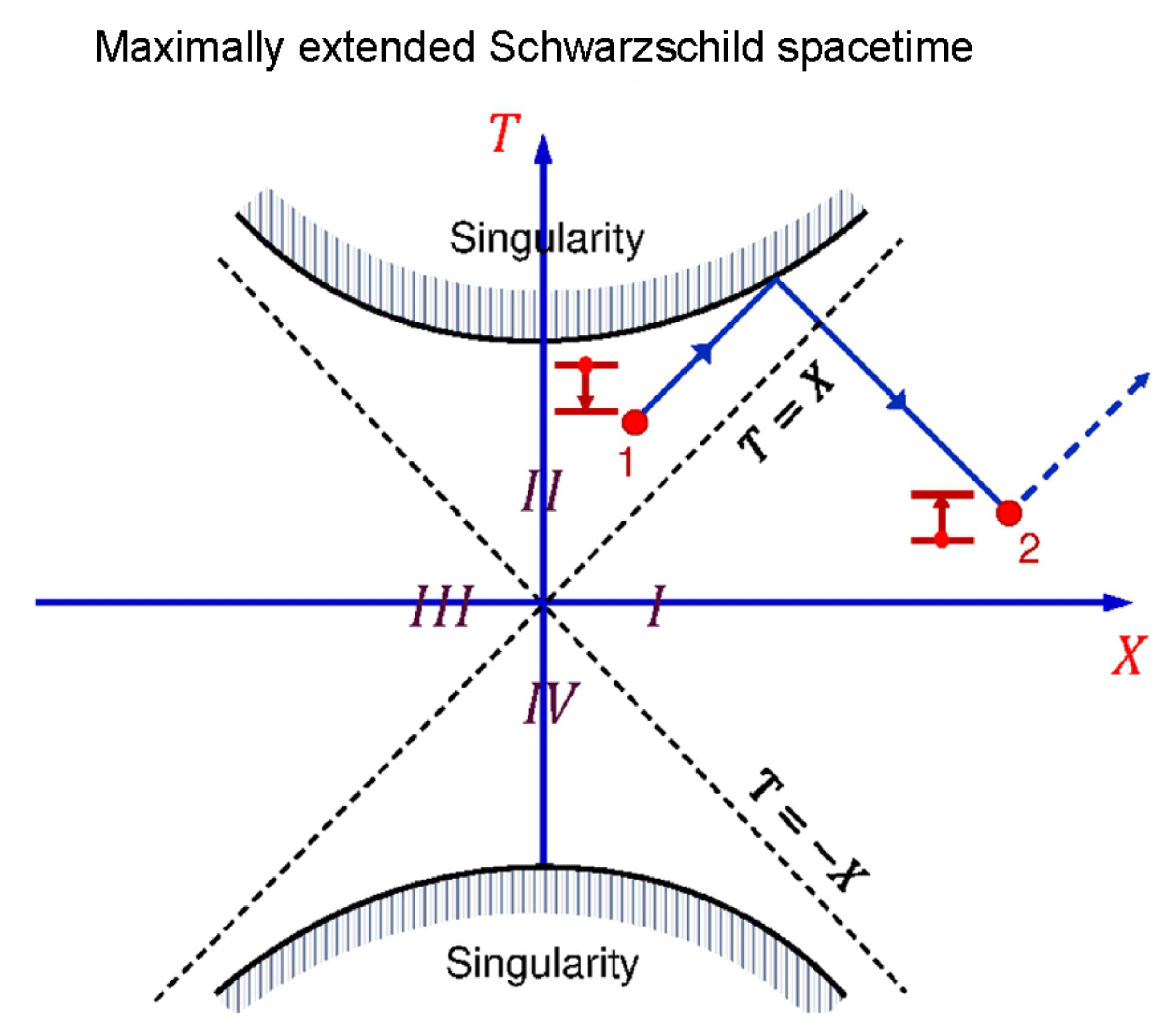

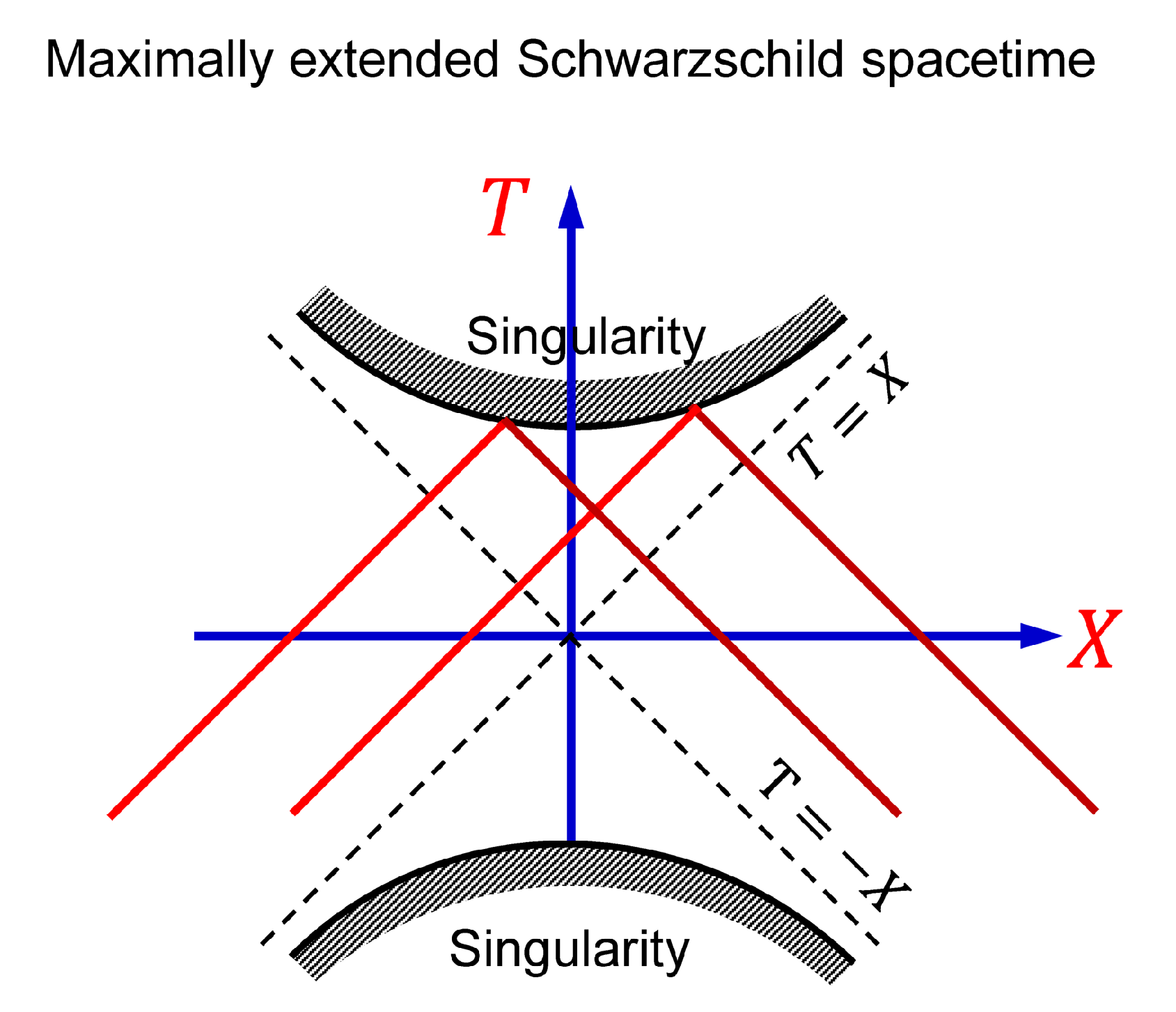

Figure 5.

Kruskal–Szekeres diagram of a maximally extended Schwarzschild spacetime. The quadrants are the black hole interior (II), the white hole interior (IV) and the two exterior regions (I and III). The dotted lines, which separate these four regions, are the event horizons. The hyperbolas which bound the top and bottom of the diagram are the black and white hole centers () which act as superluminal time mirrors. Excited atom 1 located inside the black event horizon can emit a photon which is reflected from the center and propagates backward in time outside the black hole. Such photon can excite a ground-state atom 2 which then spontaneously decays by emitting a photon propagating forward in time.

Figure 5.

Kruskal–Szekeres diagram of a maximally extended Schwarzschild spacetime. The quadrants are the black hole interior (II), the white hole interior (IV) and the two exterior regions (I and III). The dotted lines, which separate these four regions, are the event horizons. The hyperbolas which bound the top and bottom of the diagram are the black and white hole centers () which act as superluminal time mirrors. Excited atom 1 located inside the black event horizon can emit a photon which is reflected from the center and propagates backward in time outside the black hole. Such photon can excite a ground-state atom 2 which then spontaneously decays by emitting a photon propagating forward in time.

In the following, we will adopt the boundary condition (

38) for the Schwarzschild BH in the simplified 1+1 dimensional model. The boundary condition (

38) can be also obtained directly in 1+1 dimension from the requirement that the field flux through the spacetime boundary

is equal to zero.

Introducing a new scalar field

and taking into account that

we find that

obeys the wave equation

subject to the mirror-like boundary condition at the superluminal (space-like) line

That is, for the field

, the BH center

acts as a superluminal mirror. For

obeys the same wave equation as in the Minkowski spacetime, and the same boundary condition, the results obtained in the previous section can be applied here as well. One should mention that the boundary condition (

39) has been introduced in Ref. [

27] without derivation in connection with the Hawking radiation problem.

Figure 5 illustrates a maximally extended Schwarzschild spacetime of a static BH in the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates

X. The hyperbolas which bound the top and the bottom of the diagram are the BH and white hole centers respectively, which act as superluminal time mirrors. After reflection from the center, the field propagates backward in time and escapes from the BH. In particular, photons emitted by atoms inside the BH event horizon escape from the BH and can excite atoms in the exterior region (see

Figure 5).

The back-in-time propagating photons excite atoms in an unusual manner. Namely, since the proper time of the atom determines the positive direction of the time axis, the process looks like a ground-state atom becomes excited by emitting a photon (Cherenkov-like radiation [

19]). However, the emitted photon cannot be detected because its future path till the BH center is determined and, hence, it cannot be absorbed before it hits the center. Such photon can only be emitted sufficiently close to the center so that there is nothing on its path to interact with. Light reflected from the BH center and propagating away from the BH backward in time is interpreted by a distant observer as usual radiation coming from a point source. Such radiation can excite ground-state atoms which then can spontaneously decay back to the ground state by emitting photons propagating forward in time (see

Figure 5).

General solution of Equation (

37) satisfying the boundary condition (

38) reads

where

f is an arbitrary function. It is insightful to consider solutions in the form

where

is the frequency of the wave far away from the BH in Schwarzschild coordinates. Mode functions analogous to Equation (

41) have been discussed in connection with a uniformly accelerated mirror in Minkowski spacetime [

28]. The first (second) term in the right-hand side of Equation (

41) is nonzero only above the horizon

(

). Solutions (

41) describe waves falling into the top spacetime boundary

, which are then totally reflected from the boundary and propagate backward in time (see

Figure 6). Which term in Equation (

41) is interpreted as an incident (reflected) wave is determined by the location of the source generating such a wave.

To make the set of modes (

41) complete, one should add mode functions describing reflection of waves propagating backward in time from the white hole center (bottom spacetime boundary of

Figure 5)

which are a superposition of terms that are nonzero in the opposite half-plane from the corresponding horizons

. After reflection from the white hole center the wave propagates forward in time.

Figure 6.

Rays of waves falling into and reflected from the center of 1+1 dimensional black hole in a maximally extended Schwarzschild spacetime in the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates.

Figure 6.

Rays of waves falling into and reflected from the center of 1+1 dimensional black hole in a maximally extended Schwarzschild spacetime in the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates.

The Schwarzschild coordinate system can only cover regions I and II in the Kruskal-Szekeres diagram of

Figure 5. Regions III and IV describe extension of the Schwarzschild spacetime into “parallel” universe. Solutions (

41) and (

42) describe propagation of waves into (from) the parallel universe. When such a wave crosses the boundary of the parallel universe, it disappears from the Schwarzschild spacetime (regions I and II). If the parallel universe does not exist, then we must choose mode functions which would not terminate in the Schwarzschild spacetime. Such mode functions can be constructed by taking sum of Equations (

41) and (

42), which yields

or in the Schwarzschild coordinates

where we used

Equation (

44) describes a wave falling into the BH (first term) which is totally reflected from the center and propagates away from the BH (second term). Lines of constant phase of such waves (light rays) in the Kruskal-Szekeres and Schwarzschild coordinates are shown in

Figure 7.

Figure 7 shows that when the reflected wave emerges from the BH horizon it begins to propagate forward in time. That is from the perspective of a distant observer, the BH acts as a usual perfectly reflecting static point-like mirror. Namely, far from the center

, both the ingoing and the outgoing waves propagate forward in time.

If a short pulse is sent to the BH, which can be approximated as a

function, the corresponding solution for the field reads

where

is a constant determined by the position of the pulse at

. In the Schwarzschild coordinates we obtain

The worldline of the

function pulse coincides with the light rays shown in

Figure 7. Using the general solution (

40), one can construct other types of pulses, e.g., Gaussian pulses, etc.

3.2. Exact solution in 3+1 dimension

To demonstrate that the effect is not a fluke of the simplified truncated spacetime model, we here present an exact solution of the problem in 3+1 dimension. Namely, we present solutions analogous to the modes (

44). To obtain such solutions, it is convenient to start from the field equation (

30) in the Schwarzschild coordinates. In 3+1 dimension, for spherical symmetry, Equation (

30) reduces to

One can separate variables by looking for the solutions in the form

which yields the following equation for

This equation can be solved exactly, with its solutions being expressed in terms of the confluent Heun functions

HeunC [

29]. Two independent solutions of Equation (

46) are given by

and its complex conjugate. The confluent Heun function in Equation (

47) logarithmically diverges at

, but regular elsewhere. The pre-factor

has a logarithmic phase singularity at the horizon

.

Next we note that if

is a solution of Equation (

45), then functions

and

are also solutions of Equation (

45). This property allows us to construct mode functions that are regular along the wave propagation in the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates by replacing the pre-factor

in Equation (

47) with

, which yields another solution. Taking a linear combination of this solution with its complex conjugate, we obtain the following solutions of Equation (

45)

which are analogous to the mode functions (

44). In Equation (

48)

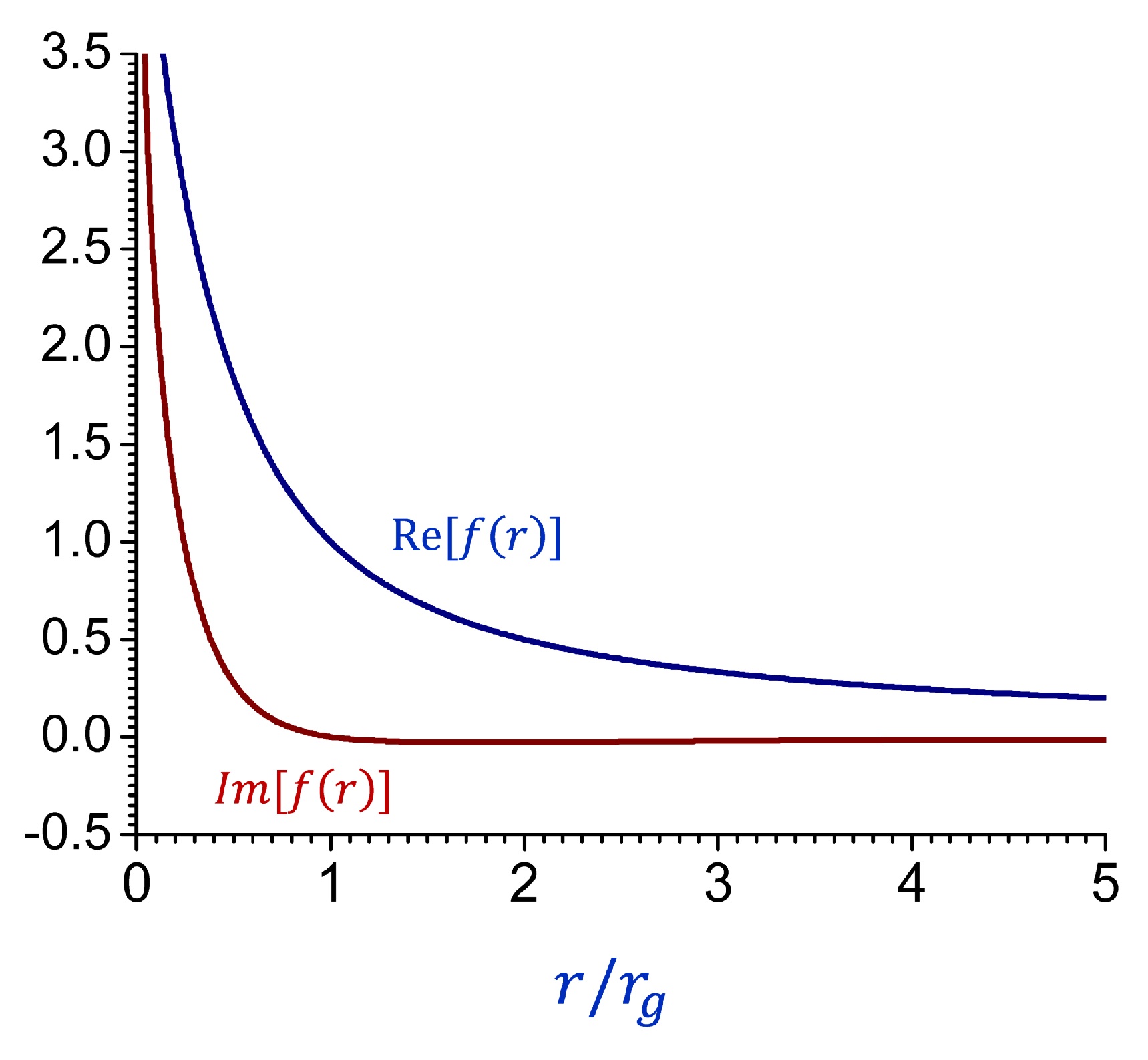

In

Figure 8 we plot the real and imaginary parts of

as a function of

r which shows their regular behavior everywhere, apart from the logarithmic divergence at

.

The complex constant

is obtained from the requirement that functions

must be finite at

. Taking into account the asymptotic of the confluent Heun function for

we find

The phase of

can be calculated numerically, but it is irrelevant for the present discussion.

The asymptotic (

49) can be found from Equation (

46) by taking the limit

which yields equation

whose solutions are combinations of the Bessel functions

The Bessel function of the second kind

leads to the logarithmic divergence at

.

One should note that the requirement of boundedness of the field at

can be obtained by calculating the flux of the field current

through a sphere of a small radius

r, and taking the limit

. The flux vanishes only if the field is finite at the BH center. Non-zero flux would imply that the field simply disappears at the BH center.

The asymptotic of the confluent Heun function for

is [

30]

where

is a constant which depends on

. Thus, far from the BH the mode functions (

48) decay as

Equation (

50) shows that an ingoing spherical wave is totally reflected from the BH center (since

) and propagates away to infinity. In the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates, the mode functions (

48) read

where dependence of

r on

T and

X is given by Equation (

35).

4. Backward in time reflection from de Sitter space boundary

De Sitter metric describes the spacetime produced by a uniform matter density permeating an infinite, homogeneous medium [

31]

where

is the de Sitter radius which describes the limiting distance beyond which the spacetime curvature prevents any signal moving forward in time from ever reaching us (the event horizon). At this distance the enclosed mass is sufficient to turn it into the Schwarzschild radius for an observer at the origin of the spherical coordinates. De Sitter space can be defined by a hyperbola embedded in 4+1 dimensional Minkowski space [

32].

During cosmic inflation of the early universe the exponential expansion of space can be also described by the de Sitter metric [

32,

33]. In a space that expands exponentially with time, any pair of free-floating objects that are initially at rest will move apart from each other at an accelerating rate (if the objects are not bound together). From the point of view of one such object, the spacetime is something like an inside-out Schwarzschild black hole - each object is surrounded by a spherical event horizon. According to the conventional wisdom, once the other object has fallen through this horizon it can never return, and even light signals it sends will never reach the first object.

In this Section we show that signals moving outside the horizon () can be reflected back in time from the de Sitter space boundary (at ) similarly to the time reflection from the BH center. Such backward in time propagating signals can pass the event horizon and reach the interior region .

In the following, we will use

as a unit of length, and

as a unit of time. To make the analogy with the superluminal mirror straightforward, we make the following coordinate transformation

for

, and

for

. In these coordinates, the de Sitter space boundary (

) is a space-like line

along which

, while the origin (

) is a time-like line

. In the coordinates

T and

X the metric (

51) reads

If spacetime is truncated to 1+1 dimension,

T and

X, the metric (

52) is conformally invariant to the Minkowski metric

and the scalar field

obeys the same wave equation as in the Minkowski spacetime

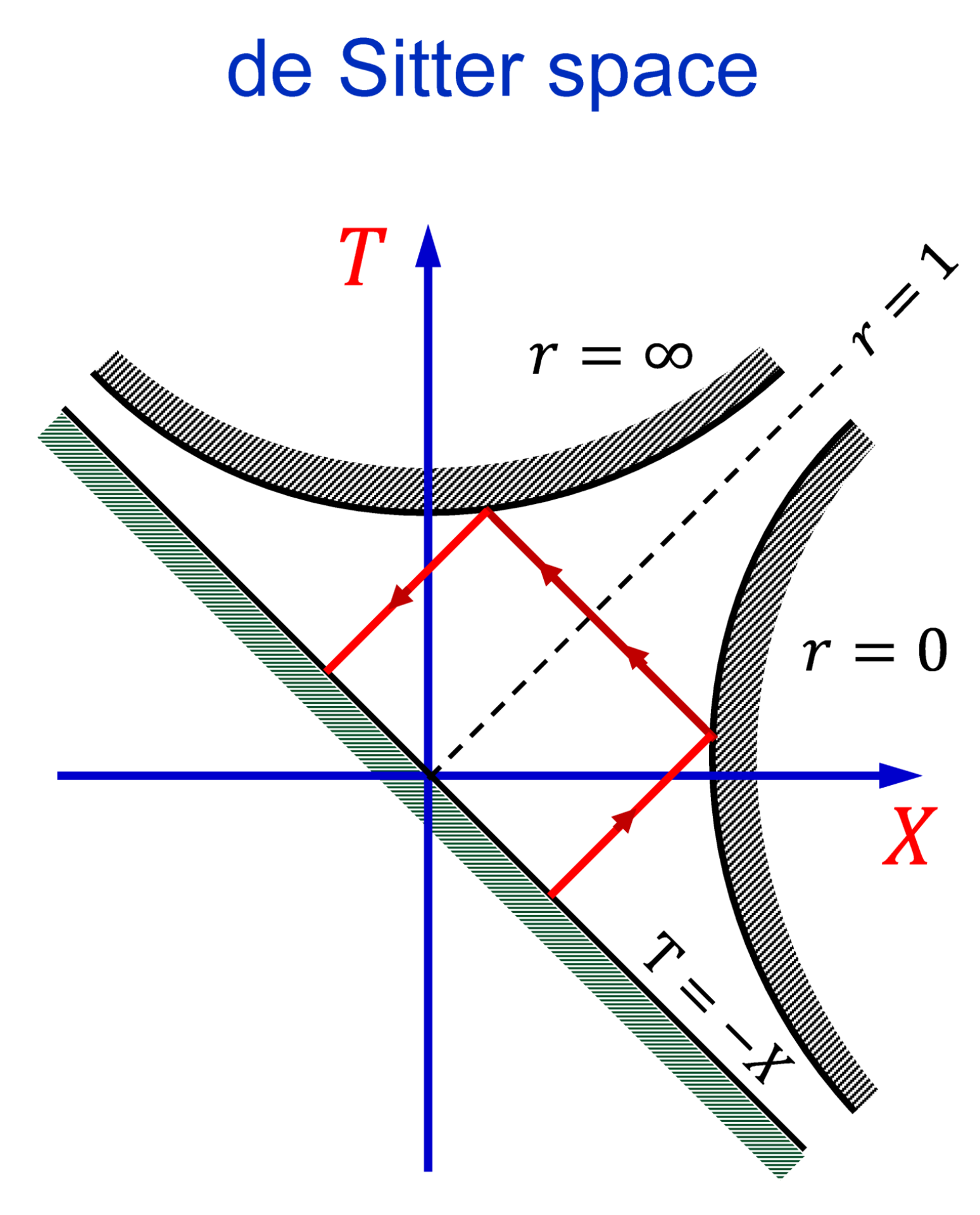

Figure 9.

Diagram of the de Sitter space in T - X coordinates. The space is bound by a time-like hyperbola , a space-like hyperbola and a straight line . Solid lines indicate a wave ray traveling in the de Sitter space and undergoing backward in time reflection from the superluminal boundary and usual reflection from the subluminal boundary .

Figure 9.

Diagram of the de Sitter space in T - X coordinates. The space is bound by a time-like hyperbola , a space-like hyperbola and a straight line . Solid lines indicate a wave ray traveling in the de Sitter space and undergoing backward in time reflection from the superluminal boundary and usual reflection from the subluminal boundary .

Figure 9 shows the diagram of the truncated de Sitter space in the coordinates

T and

X. The space is bound by the lines

(

),

(

) and

. The latter two boundaries are the same as in the case of the Schwarzschild spacetime in the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates (see

Figure 7a). The horizon is drawn as a dashed line in

Figure 9.

Solid line indicates a wave ray traveling in the de Sitter space. If particles do not disappear from the spacetime at the boundaries they undergo backward in time reflection from the superluminal boundary . The reflected wave crosses the horizon and propagates into the interior region . In contrast to BHs, in the present case the spacetime is not singular at the superluminal boundary.

In 3+1 dimension, for spherical symmetry, wave equation for the scalar field (

30) in the metric (

51) reduces to

which has the following solution analogous to the mode function (

48)

where

C is an integration constant. For solution (

53) the flux of the field current through a sphere of radius

r is independent of

r and goes as

. Thus, flux vanishes if

. For

Equation (

53) has the asymptote

which is finite at the origin if

. Hence, we obtain that for

Equation (

53) describes a standing spherical wave formed by reflection at the center (

) and back in time reflection from the superluminal boundary at

. Thus, de Sitter space acts as a cavity which traps electromagnetic radiation.

5. Summary and discussion

In this paper we consider reflection of light, approximating it as a massless scalar field , from a perfect fictitious mirror that propagates faster than light in vacuum, and impose the boundary condition that the field vanishes at the mirror surface. In this case, there are no transmitted pulses and a reflected pulse must be present to satisfy the boundary condition. We found that light propagates backward in time after reflection from such a mirror which can affect the past. Namely, using the superluminal mirror one can send information into the past. This leads to logical contradictions associated with time travel paradoxes - the grandfather paradox, causal loops, etc.

Here we prefer not to speculate whether time travel is possible, but want to mention that it is not clear how to realize the superluminal mirror with the perfectly reflecting boundary condition in laboratory experiments. Superluminal motion of inhomogeneities (e.g., medium refractive index or ionization fronts in plasma) in a fixed medium have been realized experimentally [

34]. However, the parameter inhomogeneity (for example, discontinuity in the permittivity) traveling at a velocity exceeding the speed of light does not yield the perfectly reflecting boundary conditions at the superluminal surface and, as a result, the boundary conditions can be satisfied without backward in time reflection that can affect the past [

14,

15,

16,

18].

We also found that centers of hypothetical BHs might act as a time mirror. Namely, in the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates the center of a Schwarzschild BH moves along the superluminal (space-like) trajectory . According to general relativity, spacetime disappears at the BH center. It is usually assumed that matter disappears together with the spacetime. Here we impose a boundary condition that the field does not disappear at the BH center (or, equivalently, it remains finite at the center). In this case, as we show, light is totally reflected from the center. The reflected field propagates backward in time, passes through the event horizon and moves away from the BH.

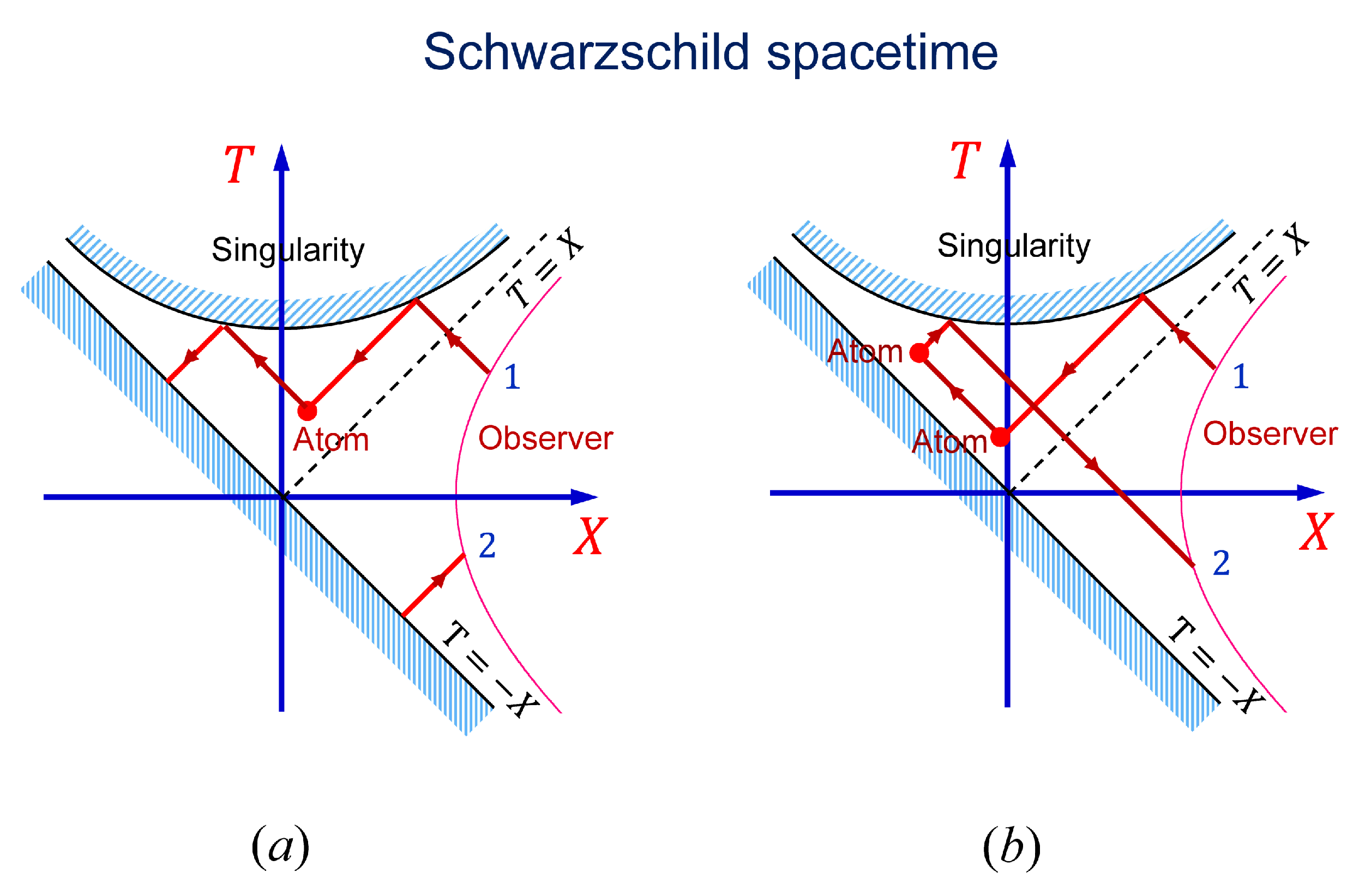

We find that due to the peculiar structure of the Schwarzschild spacetime, photons reflected from the BH center can propagate both forward and backward in time in the exterior region. In particular, from the perspective of a distant observer, the BH acts as a usual static perfectly reflecting point-like mirror. Namely, in the exterior region, both the ingoing and the outgoing waves propagate forward in time (see

Figure 7). If the wave source is located inside the event horizon, then, depending on which direction the wave is emitted, after reflection from the center the wave can propagate into the exterior region as forward or backward in time, or as a combination of those two (see

Figure 10). Photons, propagating backward in time excite atoms in an unusual way. Namely, the process looks like the ground-state atom becomes excited by emitting a negative-energy photon, which is analogous to Cherenkov radiation [

19].

We also show that a similar situation occurs in the de Sitter space. Namely, the space boundary acts as a time mirror. Particles reflected from the boundary propagate backward in time and pass the event horizon into the interior region. In contrast to BHs, de Sitter space is not singular at the superluminal boundary.

If BH centers are time mirrors, it is at odds with the generally accepted wisdom that BHs are spacetime regions that nothing in it can escape to infinity. Namely, light emitted inside the event horizon can never reach the external observer, and anything that passes through the event horizon from the observer’s side is never seen again by the observer. This conclusion results from not imposing the boundary condition for the field at the BH center, assuming that it simply disappears. Imposing no boundary condition leads to acceptance of divergent solutions for the field as meaningful. Please note that the scalar field itself diverges at the center, which is independent of the choice of coordinates since the field is scalar. For such divergent solutions, the flux of the field into the BH singularity is non-zero.

If we want to avoid divergence of the field in the Schwarzschild spacetime (and nonzero field flux into the BH center), we must allow solutions propagating backward in time. One should mention that authors of Ref. [

35,

36,

37,

38] also noticed that if the boundedness of the field is required at the BH center, then there are two different arrows of time, in agreement with our results. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that vanishing boundary condition at the BH center can be natural [

39]. It has been also shown that boundary conditions at the BH singularity prevent a loss of quantum mechanical information from the spacetime, which might be a possible way to resolve the BH information paradox [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. However, the BH information paradox can be also resolved without backward in time propagation [

46].

If BHs are time mirrors, the existence of BHs is somewhat at tension with astronomical observations. For example, when matter, e.g. atoms, fall into the BH center (singularity) the coupling between atoms and light changes nonadiabatically on a time scale of the light oscillation period. Such nonadiabatic change of coupling yields emission of bursts of radiation by atoms inside the event horizon. After reflection from the BH center, such radiation bursts propagate backward in time and escape from the BH. Due to this radiation mechanism, accreting BHs could look intrinsically bright, which contradicts observations of BH candidates in binary systems or supermassive BHs in galactic centers. To resolve the issue one can, e.g., argue that there is an optically thick gas cloud around the BH center which absorbs photons propagating backward in time before they reach the event horizon and, hence, photons cannot escape. Proper modeling of such systems can shed more light on this problem.

Another issue is the following. If the BH center reflects infalling light and matter, then BHs cannot grow by consuming the accreting mass. This contradicts to observations of supermassive objects at galactic centers, which are believed to become supermassive by consuming accreted matter. Moreover, the problem of gravitational collapse itself must be reconsidered if we allow the backward in time propagation. If only forward in time propagation is permitted, once the surface of the star has entered the Schwarzschild sphere during the gravitational collapse, one has a BH. The matter of the star and its radiation are then permanently trapped in the BH [

47]. However, backward in time propagation permits matter escape at any stage of the collapse. The inner part of an unstable star will first contract and then expand. What kind of object is formed under these conditions is a question for future study.

If BH acts as a perfect mirror then there is no information loss, and, hence, no BH information paradox. However, in this case, BHs can be used to build a time machine that allows us to send a signal into the past, yielding logical contradictions and associated time travel paradoxes. An example of a BH-based time machine is shown in

Figure 11. A distant observer, which we assume is located at fixed

, sends a signal (light pulse) into the BH at a point 1 of its trajectory. After reflection from the BH center, the pulse propagates backward in time away from the center and is absorbed by an atom located inside the event horizon. The atom re-emits the pulse toward the center and the pulse is reflected from the center one more time (

Figure 11a). After that, the pulse propagates away from the BH and crosses the observer’s trajectory at a point 2, which is earlier in time than the original point 1. That is observer can send information to itself into the past. In another version of the machine, the pulse re-emitted by the atom hits another atom that redirects the pulse into a different trajectory, which leads to a similar result (

Figure 11b).

The point of our paper is that in the case of BHs, the field equations have nonsingular solutions if we allow backward in time propagation. We prefer not to speculate which solution, singular or nonsingular, should be chosen in BH models. This question should be addressed to experiments. In either case, classical BHs do not obey the physics we are used to: or they are singular objects for which matter disappears together with the spacetime at the singularity, or they are nonsingular but the associated backward in time propagation yields time travel paradoxes.

In addition to exploring unconventional BH physics, one should look for alternatives of general relativity which predict no event horizons and no singularities and, thus, no unusual physics. BHs have never been observed directly and the usually-cited evidence of their existence is based on the assumption that general relativity provides the correct description of strong field gravitation. Until signatures of the event horizons are found the existence of BHs will not be proven.

A vector theory of gravity is the viable alternative [

48,

49]. The theory assumes that gravity is a vector field in fixed four-dimensional Euclidean space which effectively alters the spacetime geometry of the Universe. Despite fundamental differences, vector gravity also passes all available gravitational tests, including detection of gravitational waves by LIGO and Virgo [

48]. In addition, vector gravity provides an explanation of dark energy as the energy of the longitudinal gravitational field induced by the expansion of the Universe and yields, with no free parameters, the value of

[

49] which agrees with the results of Planck collaboration [

50] and results of the Dark Energy Survey. Thus, vector gravity solves the dark energy problem.

In strong fields, vector gravity deviates substantially from general relativity and yields no BHs. In particular, since the theory predicts no event horizons, the end point of a gravitational collapse is a stable star with a reduced mass. It has been shown that properties of supermassive objects at galactic centers can be explained well in the framework of vector gravity, including their images by the Event Horizon Telescope [

51,

52].

Moreover, it has been found recently that the data on gravitational wave (GW) detection of binary neutron star event GW170817, whose source location is determined precisely by concurrent electromagnetic observations, are inconsistent with the tensor GW polarization predictions of general relativity and Einstein’s theory is ruled out at 99% confidence level [

52]. At the same time, vector GW polarization, predicted by the vector theory of gravity, is supported by the GW detection data [

52]. If true, future GW detections for which the GW source is identified should confirm this conclusion with a greater accuracy.