1. Introduction

Emerging contaminants (ECs), or contaminants of emerging concern (CECs), include various chemical substances with potential risks to human health and ecosystems due to their persistence and toxicity [

1]. These substances have been identified in the environment and consist of pharmaceuticals[

2], personal care products[

3], endocrine disruptors[

4], and industrial chemicals[

5]. Despite their presence, they largely remain unregulated or inadequately monitored. Many of these contaminants enter ecosystems through wastewater, agricultural runoff, or industrial emissions and landfill leachate[

6] posing potential risks to both ecosystems and human health. The persistence and potential bioaccumulation of ECs, combined with their often-unknown toxicological profiles, can disrupt natural habitats, alter biodiversity, and introduce health risks when they infiltrate drinking water sources [

7].

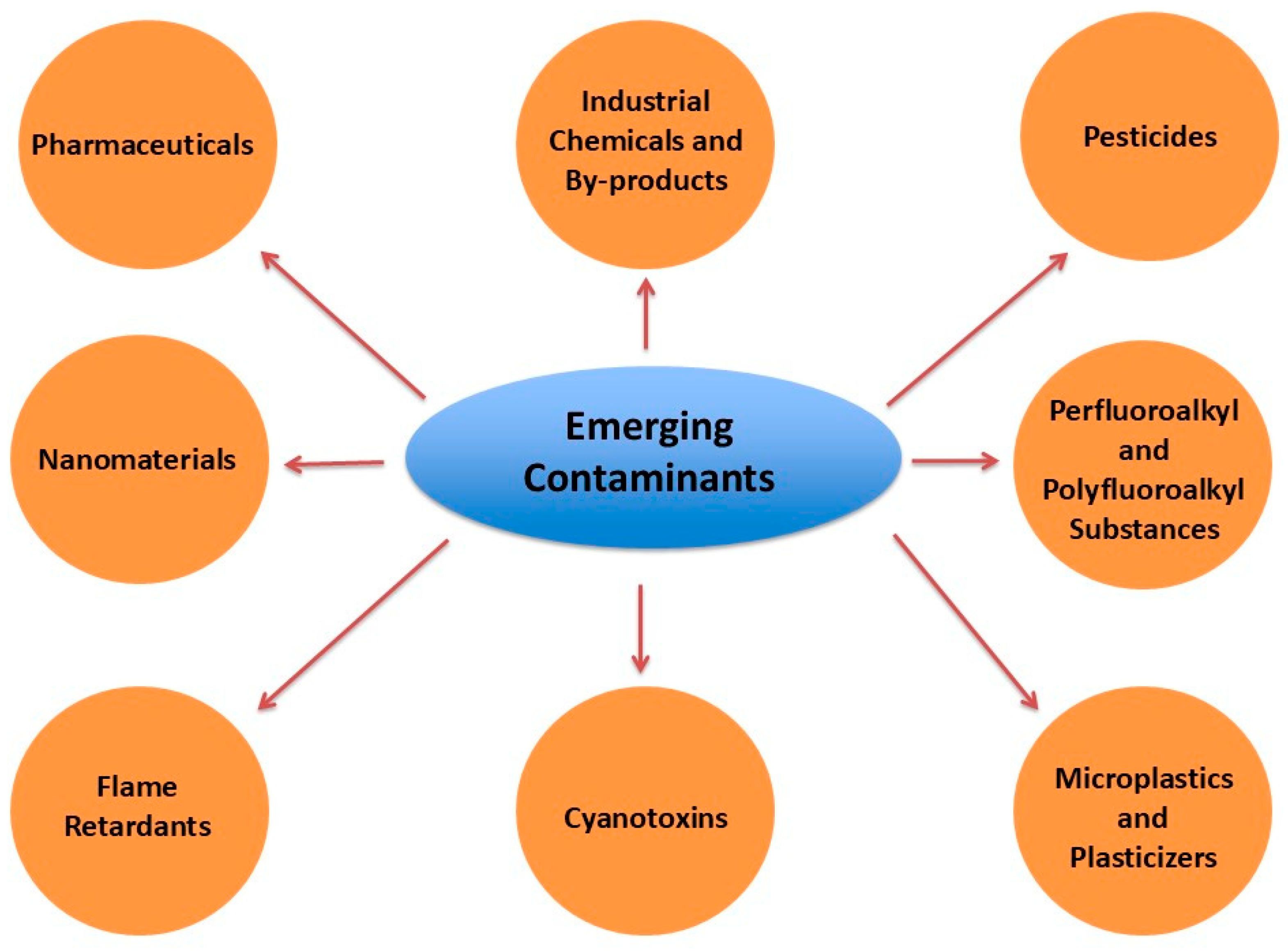

Figure 1.

Categories of emerging contaminants.

Figure 1.

Categories of emerging contaminants.

Emerging contaminants are constantly evolving, as substances initially identified become recognized environmental threats with advancing scientific insights. This category includes both newly synthesized chemicals and "legacy" contaminants which are familiar substances like lead and arsenic. Their effects and environmental behaviors are now being reconsidered as new data surfaces. Pollutants such as cyanotoxins from algal blooms and by-products from water treatment processes illustrate the extensive and unpredictable range of these contaminants. The complex, interconnected effects of these pollutants highlight the necessity for multidisciplinary approaches to thoroughly evaluate their impacts on human health, ecosystems, and natural resources. The criteria for classifying a substance as an emerging contaminant (EC) hinge on several key factors, which underscore their potential risks to ecosystems and human health. First, persistence in the environment is a fundamental trait; ECs tend to resist natural degradation processes, allowing them to remain active and accumulate over extended periods [

8]. This persistence makes them difficult to manage through conventional treatment or remediation processes, increasing their chances of widespread distribution. Another important factor is bioaccumulation, as many ECs are capable of concentrating within biological systems, potentially transferring from one organism to another across trophic levels [

9]. This can lead to long-term ecological impacts, as these contaminants travel up the food chain, posing threats to wildlife and, eventually, humans who consume contaminated species.

Toxicity is also a significant criterion, although toxicological data on many ECs remains incomplete. Despite this limitation, some ECs have been linked to harmful effects on various organisms, particularly through endocrine and reproductive disruptions. For example, pharmaceuticals and personal care products that act as endocrine disruptors can alter hormonal balances in aquatic species, leading to population-level effects [

10]. Finally, ubiquity and detection are key considerations. ECs are increasingly detected in a wide range of environments, from urban and rural water systems to remote ecosystems like Arctic waters and even atmospheric layers. Their ability to spread across diverse habitats further emphasizes their potential for far-reaching impacts. Together, these criteria highlight the complexity of managing ECs and the need for enhanced monitoring, regulation, and public awareness to address their environmental and health implications effectively [

11].

In tackling emerging contaminants, researchers and policymakers must navigate challenges in prioritization and risk assessment. Limited toxicological data, along with varying persistence and degradation rates, complicate efforts to establish safe exposure thresholds and environmental guidelines. The constantly evolving landscape of these contaminants calls for adaptive management strategies and enhanced funding for research. Proactive monitoring and advanced treatment technologies are essential to mitigate the risks associated with these pollutants, yet resource constraints and gaps in public awareness continue to hinder widespread implementation.

The detection and quantification of these contaminants are essential for environmental safety, as many of them exhibit toxic properties even at low concentrations. Increased detection efforts have highlighted the widespread distribution of ECs across different environmental media, including soil, water, and air. The environmental behavior of these contaminants is complex and often varies with chemical composition, posing challenges to effective environmental management. Their potential to affect various ecological and human health systems has prompted regulatory agencies to monitor their prevalence and influence, especially in sensitive ecosystems like aquatic environments [

7].

2. Mass Spectrometry for Emerging Contaminants Analysis

Mass spectrometry (MS) has emerged as a critical analytical tool in identifying and quantifying ECs in complex environmental samples. MS has become an invaluable analytical tool in detecting and quantifying emerging contaminants (ECs) within environmental samples. Its high sensitivity, selectivity, and adaptability make it especially suitable for analyzing trace contaminants across various environmental media, such as water, soil, and air. Several MS techniques stand out for environmental applications, each offering unique advantages based on the characteristics of the contaminants. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) is commonly used for analyzing volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds, such as industrial chemicals and certain pesticides. By separating compounds based on their volatility before they reach the MS detector, GC-MS enables precise identification and quantification, making it a preferred method for monitoring air quality and soil contamination.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), in contrast, is well-suited for non-volatile and thermally unstable compounds, such as pharmaceuticals and personal care products. LC-MS separates analytes based on their solubility in different solvents, allowing it to handle the complex matrix of environmental samples like wastewater. This technique is highly effective for monitoring ECs in aquatic environments, where such contaminants are often found in low concentrations.

Proton Transfer Reaction Mass Spectrometry (PTR-MS) is a real-time MS technique primarily used for detecting volatile organic compounds (VOCs) directly in the air without the need for pre-separation. This high-throughput capability makes PTR-MS suitable for continuous environmental monitoring, especially for compounds that rapidly disperse or change concentrations, such as VOCs from industrial emissions.

Lastly, Selected Ion Flow Tube Mass Spectrometry (SIFT-MS)[

12] is another direct MS method that provides real-time detection of trace gases in complex samples. Like PTR-MS, SIFT-MS does not require pre-separation but instead uses controlled chemical ionization to achieve high sensitivity and specificity. This method is effective for detecting reactive and labile compounds in ambient air, making it particularly useful for monitoring pollutants with short atmospheric lifetimes.

These MS techniques collectively offer a robust toolkit for detecting diverse ECs, providing crucial insights into their distribution, behavior, and potential risks in the environment. Their application allows scientists to track contamination patterns, identify sources, and assess ecological impacts, informing both remediation efforts and regulatory policies.

MS techniques offer high sensitivity and specificity, making them ideal for detecting trace amounts of ECs. The precision and accuracy of MS enable environmental scientists to monitor contamination levels accurately, trace pollution sources, and evaluate potential ecological impacts. This review focuses on discussing the various applications of MS in detecting and studying ECs, with an emphasis on recent advancements and challenges. The primary objective of this review is to provide an in-depth analysis of the role of MS in environmental monitoring of ECs, exploring its methodologies, applications, and limitations. By reviewing key studies and recent developments, this article aims to contribute to the growing body of knowledge on ECs and support the development of effective regulatory and mitigation strategies for environmental safety.

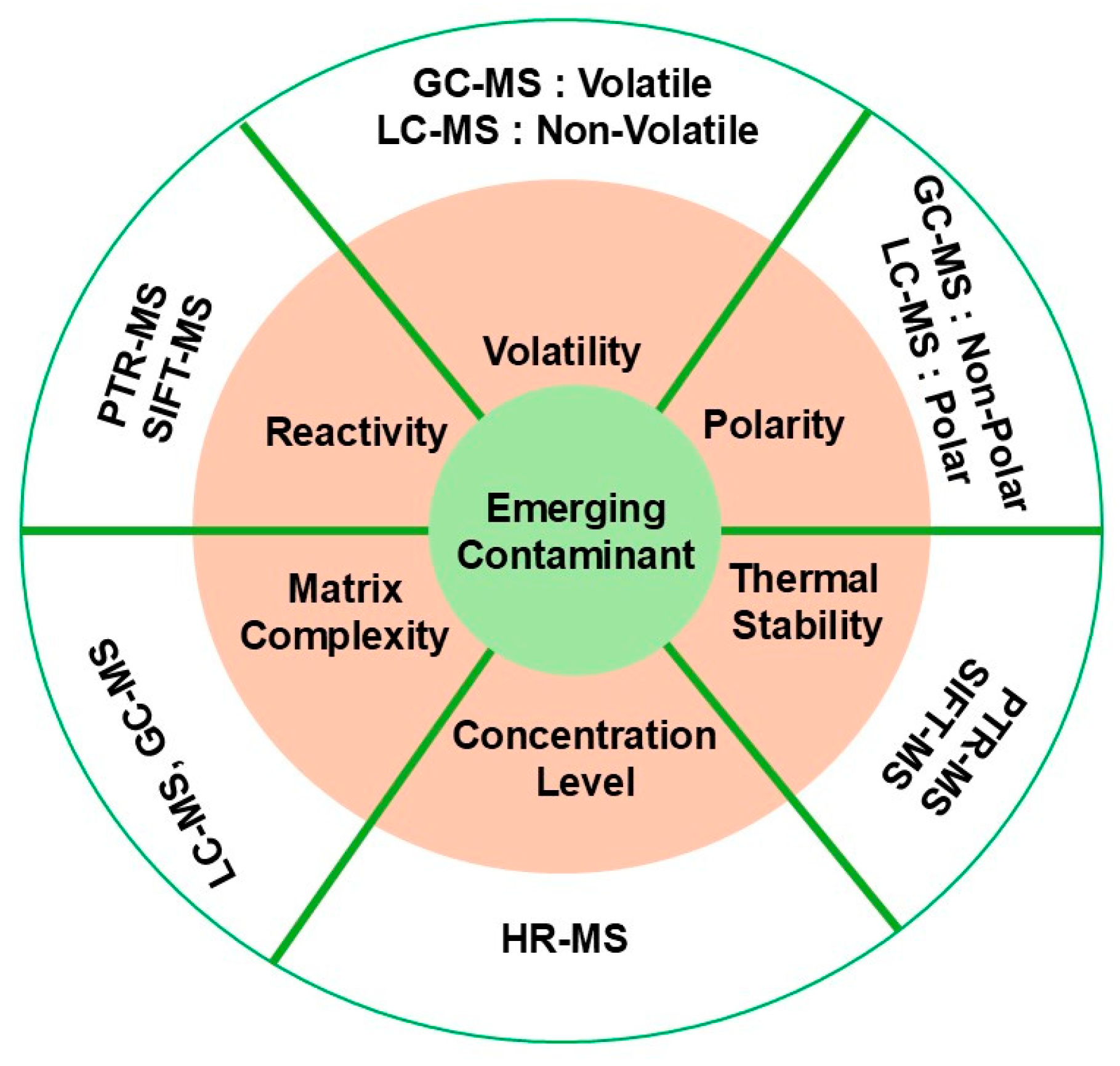

The selection of an appropriate mass spectrometry (MS) technique for detecting emerging contaminants (ECs) depends on several key characteristics of the contaminants, such as their volatility, polarity, thermal stability, concentration levels, and the complexity of the matrix in which they are found. Each MS technique has distinct advantages based on these factors, so making the right choice is essential for accurate, sensitive detection (

Figure 2).

Volatility: The volatility of a contaminant plays a significant role in choosing between Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). GC-MS is ideal for volatile and semi-volatile compounds that can be vaporized without decomposition, like benzene, toluene, and some pesticides, which are commonly found in industrial and agricultural settings [

13]. LC-MS, however, is preferred for non-volatile or thermally sensitive compounds, such as antibiotics and steroid hormones, which would degrade if vaporized [

14].

Polarity: The polarity of ECs influences their separation and detection efficiency in chromatography. LC-MS is particularly effective for polar and ionic compounds like pharmaceutical residues (e.g., acetaminophen) and certain personal care products, as it separates these substances in a liquid phase. In contrast, GC-MS is well-suited for non-polar or moderately polar contaminants, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and certain plasticizers, which are more stable in a gaseous phase.

Thermal Stability: For contaminants that are thermally unstable—such as certain pesticides like carbamates or chemicals in personal care products—LC-MS or techniques that do not involve sample heating, like Selected Ion Flow Tube Mass Spectrometry (SIFT-MS)[

15] or Proton Transfer Reaction Mass Spectrometry (PTR-MS)[

16], are optimal. These techniques avoid the high temperatures in GC-MS, preserving the integrity of compounds that would otherwise degrade.

Concentration Levels and Sensitivity Needs: Some ECs exist in trace amounts, requiring techniques with high sensitivity. High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HR-MS) and Tandem MS (MS/MS) offer precise quantification even at low concentrations, which is essential for contaminants like endocrine-disrupting compounds (e.g., bisphenol A) in aquatic systems. For continuous monitoring of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the air, SIFT-MS and PTR-MS are advantageous as they enable real-time, high-sensitivity detection.

Matrix Complexity: The environmental matrix—whether water, soil, air, or biota—significantly impacts MS technique selection. For instance, LC-MS, often combined with solid-phase extraction, is ideal for detecting pharmaceuticals and pesticides in water. GC-MS, on the other hand, is highly effective for analyzing air samples for industrial pollutants and soil samples for semi-volatile compounds like PAHs. For gaseous matrices, PTR-MS and SIFT-MS are particularly useful, providing real-time analysis without extensive sample preparation.

Reactivity and Chemical Composition: For highly reactive or labile compounds, rapid techniques like PTR-MS or SIFT-MS, which avoid lengthy sample preparation, are suitable. These methods enable fast, real-time detection of reactive VOCs from industrial emissions, such as formaldehyde and acetaldehyde, which can change composition over time if not analyzed immediately.

By carefully considering these characteristics, researchers can select the MS technique that provides optimal sensitivity, specificity, and reliability for detecting and quantifying emerging contaminants in diverse environmental samples. This approach ensures precise data collection on EC prevalence and environmental impact, guiding effective monitoring and regulatory decisions.

3. Sample Preparation and Extraction Methods for EC Analysis

Preparing samples and extracting compounds are crucial steps in identifying emerging contaminants, especially when using advanced techniques to screen for known and unknown substances. Since environmental, biological, and food samples often come with complex mixtures, these steps must be carefully tailored to ensure accurate results while minimizing interference from other materials in the sample. Common methods like solvent extraction and solid-phase extraction (SPE) are widely used, with SPE being particularly effective for isolating contaminants from liquids [

17]. To tackle the diversity of chemicals present, researchers often use a combination of different SPE sorbents or sequential solvent extractions, aiming to capture a wide range of substances. Materials like Oasis HLB and C18 are frequently chosen for their ability to handle challenging samples, though no single approach is perfect for every situation [

18]. Dispersive micro SPE (DMSPE) is a promising approach that simplifies the SPE process by using sorbent mixtures for direct in-situ preconcentration of analytes, while fast on-line SPE introduces automation, improved repeatability, and sub-ng L⁻¹ detection limits [

19].

Advanced techniques, such as gel permeation chromatography (GPC), help remove unwanted lipids and other impurities, though they can sometimes cause the loss of important compounds [

20]. Recently, innovative solutions like ionic liquids[

21], nanomaterials[

22], and molecularly imprinted polymers[

23] have started to make a difference by improving the precision and efficiency of extractions. A recent review by Sereshti et al. provides a comprehensive overview of nanosorbent-based solid-phase microextraction (SPME) techniques for monitoring emerging organic contaminants (EOCs) in water and wastewater samples. The authors discuss the preparation, properties, advantages, and limitations of various nanosorbents used in SPME applications, including carbon-based materials like graphene and carbon nanotubes, as well as magnetic nanosorbents and metal-organic frameworks. They highlight that the selection of sorbent material is crucial for the efficiency of SPME, as it directly affects the extraction performance for target pollutants [

24].

In some cases, direct injection of samples into analytical instruments is an option, but it often struggles to detect low-concentration contaminants or deal with complex sample types. The field still faces challenges, including the lack of standardized methods and the difficulty of validating results without established reference materials. Despite these obstacles, researchers continue to develop and refine techniques, making it possible to uncover and better understand the hidden chemicals that may impact our environment and health.

4. Environmental Matrices and Challenges in MS Analysis

Analyzing emerging contaminants (ECs) in diverse environmental matrices presents significant challenges, particularly when employing mass spectrometry (MS) techniques. Environmental samples such as water, sediments, soils, and air are complex and heterogeneous, often containing a multitude of organic and inorganic substances that can interfere with the detection and quantification of ECs. For instance, sediments may harbor various polar pesticides that are difficult to extract and analyze due to their low hydrophobicity and potential degradation during sample preparation [

25]. The presence of natural organic matter, humic substances, and other co-contaminants can suppress or enhance ionization in MS, leading to inaccurate quantification. Moreover, the transformation products of ECs, formed through biological or chemical degradation, add another layer of complexity. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) has emerged as a powerful tool to identify these transformation products, offering high mass accuracy and the ability to perform non-target screening [

26].

Recently, Nguyen et al. addressed the challenges of analyzing multi-class emerging contaminants in complex environmental matrices like soil and sediment, emphasizing the need for robust methodologies to extract trace-level contaminants while minimizing interference from organic matter. The study optimized a QuEChERS-based extraction method coupled with UPLC-MS/MS for 90 emerging organic contaminants, including pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and PFASs, achieving recoveries between 70% and 120% with low matrix effects. The use of citrate buffer and 1–2% formic acid significantly improved recoveries for diverse chemical classes, highlighting the importance of pH optimization in enhancing extraction efficiency [

27].

However, the lack of standardized protocols and comprehensive spectral libraries for these emerging contaminants and their transformation products hampers the identification process. Additionally, the continuous introduction of new chemicals into the environment necessitates constant updates to analytical methods and databases. Addressing these challenges requires the development of robust sample preparation techniques, advanced MS methodologies, and comprehensive databases to ensure accurate detection and assessment of ECs across various environmental matrices.

5. Recent Advances in MS for Emerging Contaminants Detection

Recent advancements in mass spectrometry (MS) have significantly enhanced the detection and analysis of emerging contaminants (ECs) in environmental matrices. Innovations such as direct mass spectrometry techniques, including Proton Transfer Reaction Mass Spectrometry (PTR-MS), have enabled real-time monitoring of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) with high sensitivity and rapid response times. Salthammer et al. (2023) highlight the critical role of Proton Transfer Reaction Mass Spectrometry (PTR-MS) in analyzing organic compounds in indoor air environments [

28]. This advanced technique provides real-time monitoring of very volatile and volatile organic compounds (VVOCs and VOCs) with high sensitivity, often reaching detection limits in the parts-per-trillion (ppt) range. PTR-MS offers significant advantages over traditional chromatographic methods by enabling the direct analysis of complex mixtures in the gas phase. The authors utilized ion-dipole collision theories, such as Average Dipole Orientation (ADO) and capture theory, to compute proton transfer rate constants (

kPT) for 114 organic compounds, supported by density functional theory (DFT) for dipole moment and polarizability calculations. Key challenges identified include calibration difficulties, molecular fragmentation influenced by electric field strengths, and the importance of thermally averaged quantum chemical calculations to (

kPT) accuracy. This work underscores PTR-MS as a versatile tool for applications in emerging contaminants detection.

Additionally, the integration of Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry (IMS-MS) has improved analytical selectivity by separating ions based on their shape and charge, thereby facilitating the differentiation of isomeric and isobaric species. Aly et al. demonstrated the utility of ion mobility spectrometry coupled with mass spectrometry (IMS-MS) for the rapid characterization and detection of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and their metabolites [

29]. This study evaluated 64 chemicals, including pesticides, industrial chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), using complementary ionization techniques like electrospray ionization (ESI) and atmospheric pressure photoionization (APPI). IMS-MS allowed simultaneous separation of parent compounds and their degradation products based on molecular weight and drift time, enabling rapid screening without extensive sample preparation. Key findings include the superior sensitivity of ESI for polar metabolites and the ability of IMS-MS to distinguish isomers of hydroxylated and sulfated POPs. The results underscore the potential of IMS-MS as a robust screening tool for environmental pollutants, facilitating exposure assessment and advancing understanding of chemical degradation pathways.

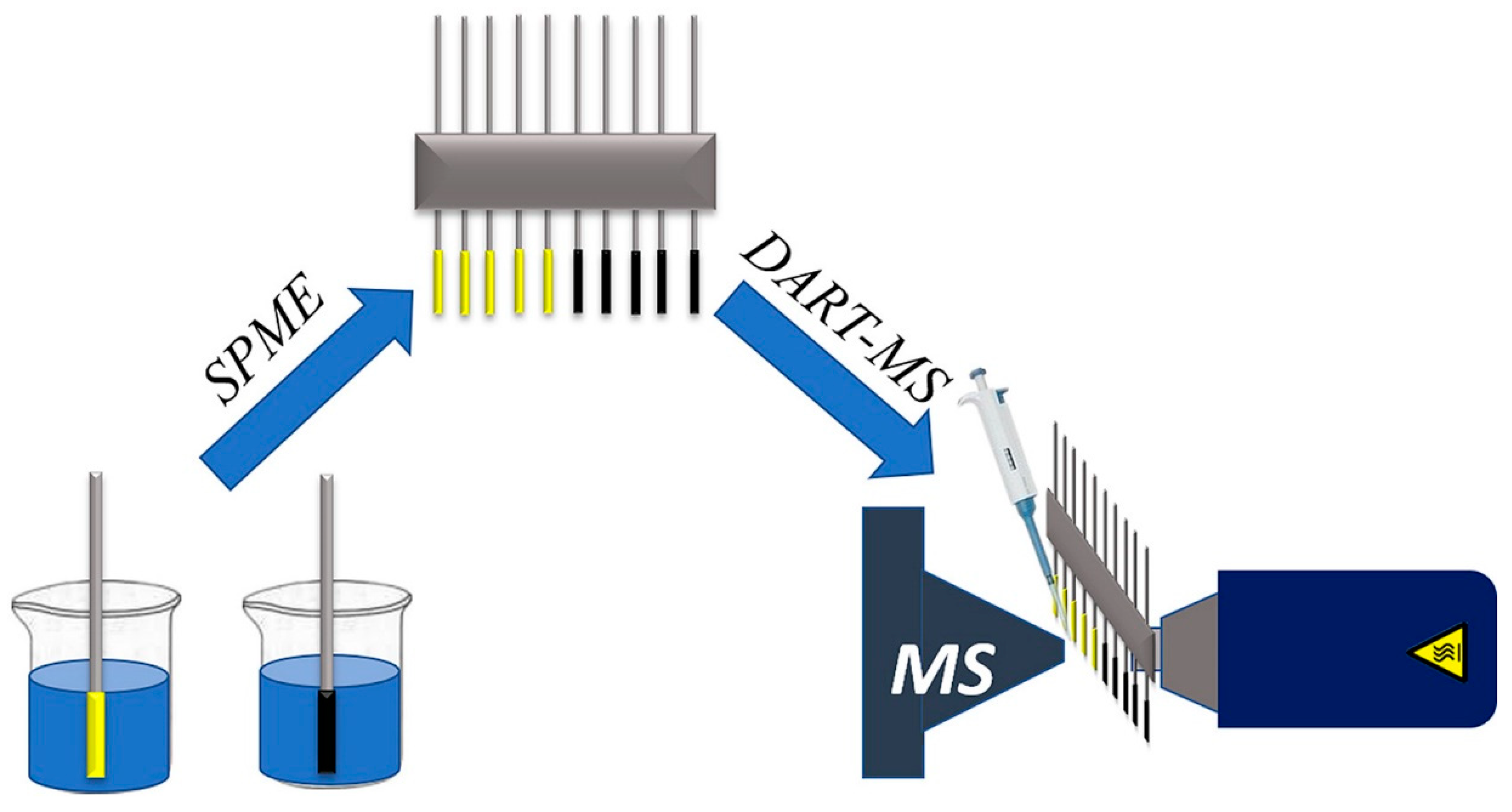

Ambient ionization techniques, such as Desorption Electrospray Ionization (DESI) and Direct Analysis in Real Time (DART), have revolutionized the field by allowing direct sampling of surfaces under ambient conditions, thus reducing sample preparation time and preserving the integrity of labile compounds. Raths et al. demonstrate the potential of Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (DESI-MS) in visualizing the spatial distribution of organic contaminants and their biotransformation products within amphipod tissues [

30]. DESI-MS imaging, combined with cryosectioning, revealed high sensitivity for detecting small organic molecules, surpassing Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization (MALDI-MS) in certain contexts. DESI’s minimal sample preparation and ability to detect compounds with lower fragmentation make it a valuable tool for environmental sciences, though advancements are needed to analyze samples at environmentally relevant concentrations. Jing et al. introduced a sorbent and solvent co-enhanced direct analysis in real-time mass spectrometry (SSE-DART-MS) method for high-throughput detection of trace pollutants in water. By integrating graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) sorbents with organic solvents, the technique achieved signal enhancements of up to 100-fold for phthalic acid esters (PAEs), with detection limits as low as 0.07 ng/L [

31]. The approach combines the advantages of solid-phase extraction and DART-MS, offering superior sensitivity and reduced matrix interference. This innovative method demonstrates potential for rapid, environmentally friendly analysis of trace contaminants in complex samples (

Figure 3).

High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HR-MS) has become a pivotal tool in identifying unknown ECs, offering precise mass measurements that aid in elucidating molecular formulas and structures. Giannelli Moneta et al. and Yang et al. emphasize the power of high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) for non-target screening of environmental contaminants. Giannelli Moneta et al. applied LC-HRMS to Arctic snow and aerosol samples, identifying over 150 compounds, including potential anthropogenic pollutants like plasticizers and flame retardants. This method highlighted the challenges of tracing sources due to limited overlap between snow and aerosol contaminants [

32]. Yang et al. showcased HRMS’s utility in industrial settings, identifying new pollutants from metallurgical and incineration processes. They highlighted HRMS’s high sensitivity for emerging contaminants, enabling source identification and supporting sustainable industrial development [

33]. Together, these studies underscore HRMS as a critical tool for tracking environmental pollutants and advancing sustainable practices. The application of HR-MS in non-target screening approaches has expanded the scope of environmental analysis, enabling the detection of previously unrecognized contaminants and their transformation products. These technological advancements collectively contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of ECs in the environment, enhancing the ability to monitor and mitigate their impact on ecosystems and human health.

6. Applications of MS in Monitoring Emerging Contaminants

Mass spectrometry (MS) has become indispensable in monitoring emerging contaminants (ECs) across diverse environments, offering unmatched sensitivity and specificity. In aquatic systems, MS techniques like LC-MS/MS and HRMS are widely used to detect pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and other micropollutants in water bodies, even at trace levels [

34]. Nazar et al. utilized GC-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS to analyze 345 micropollutants, including pesticides and endocrine disruptors, in fish from the Cochin estuary, highlighting the bioaccumulation of these contaminants and their associated health risks [

35]. Similarly, atmospheric monitoring benefits from MS techniques like PTR-MS, which detect industrial pollutants such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in real-time. For soil and sediments, MS-based methods effectively trace pesticide residues and persistent organic pollutants, aiding environmental risk assessments. In biological matrices, MS applications extend to biomonitoring ECs in wildlife, as demonstrated by the analysis of fish tissues to identify endocrine disruptors and polyaromatic hydrocarbons. These studies underscore the versatility of MS in providing robust, high-sensitivity detection across environmental and biological contexts. Atmospheric monitoring benefits from MS methods such as PTR-MS and DART-MS, which facilitate real-time analysis of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and industrial pollutants, providing insights into air quality and pollutant dispersion. Soil and sediment analysis relies on GC-MS and LC-MS to trace pesticide residues and persistent organic pollutants, revealing contamination pathways and environmental persistence. In aquatic systems, MS methods like LC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS enable the detection of trace levels of pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and other ECs in water and sediments, as highlighted by Peris and Eljarrat. Their work underscores the importance of multi-residue analysis for tracking contaminants like oxadiazon, which pose significant risks to aquatic organisms [

36]. For biological samples, MS-based biomonitoring identifies ECs and their metabolites in wildlife, such as polar bears and amphibians, elucidating bioaccumulation and ecological risks. Jasrotia et al. emphasize the widespread impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on aquatic ecosystems, highlighting their detrimental effects on wildlife and human health [

37]. These chemicals, originating from industrial, agricultural, and pharmaceutical sources, disrupt hormonal balance and affect reproduction, development, and metabolism in aquatic organisms. The study reveals bioaccumulation of EDCs through food webs, leading to significant ecological and health risks. Common contaminants include heavy metals, flame retardants, and pesticides, which interfere with endocrine signaling pathways. Efforts to mitigate these effects include advanced wastewater treatment technologies and the adoption of green chemistry solutions. This underscores the urgent need for coordinated global action to address the challenges posed by EDCs. These applications underscore MS’s pivotal role in understanding the distribution and impact of ECs on ecosystems and human health.

7. Data Analysis and Interpretation in MS-Based EC Studies

Data analysis and interpretation in mass spectrometry (MS)-based studies of emerging contaminants (ECs) involve a multi-step process that is essential for extracting reliable and meaningful results from complex environmental samples. Advanced data processing techniques, including peak detection, spectral deconvolution, and alignment of retention times, are fundamental to identifying contaminants amidst a high background of interfering substances [

38]. These methods often rely on software tools and algorithms that can handle large, multidimensional datasets, ensuring accurate quantification and identification of target and non-target compounds.

Bioinformatics and chemometric tools have become indispensable in analyzing MS data, especially in studies of ECs, which often involve complex mixtures. Techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA), hierarchical clustering, and machine learning models aid in identifying patterns, classifying contaminants, and correlating their presence to potential sources or environmental factors. For example, chemometric approaches can differentiate between anthropogenic and natural compounds, while machine learning can predict the behavior and degradation pathways of emerging contaminants based on MS data. These tools also facilitate the integration of MS data with other environmental datasets, offering a holistic understanding of contaminant behavior and impacts. Eysseric et al. presented a comprehensive workflow for non-targeted screening (NTS) of trace organic contaminants in surface waters using high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS). Their approach integrated three complementary tools: Similar Partition Searching (SPS), Global Natural Products Social Networking (GNPS), and MetFrag for the analysis of tandem mass spectra. This combinatorial method enabled the identification of 253 contaminants, including pharmaceuticals, consumer product additives, and pesticides, with 44 compounds confirmed using reference standards [

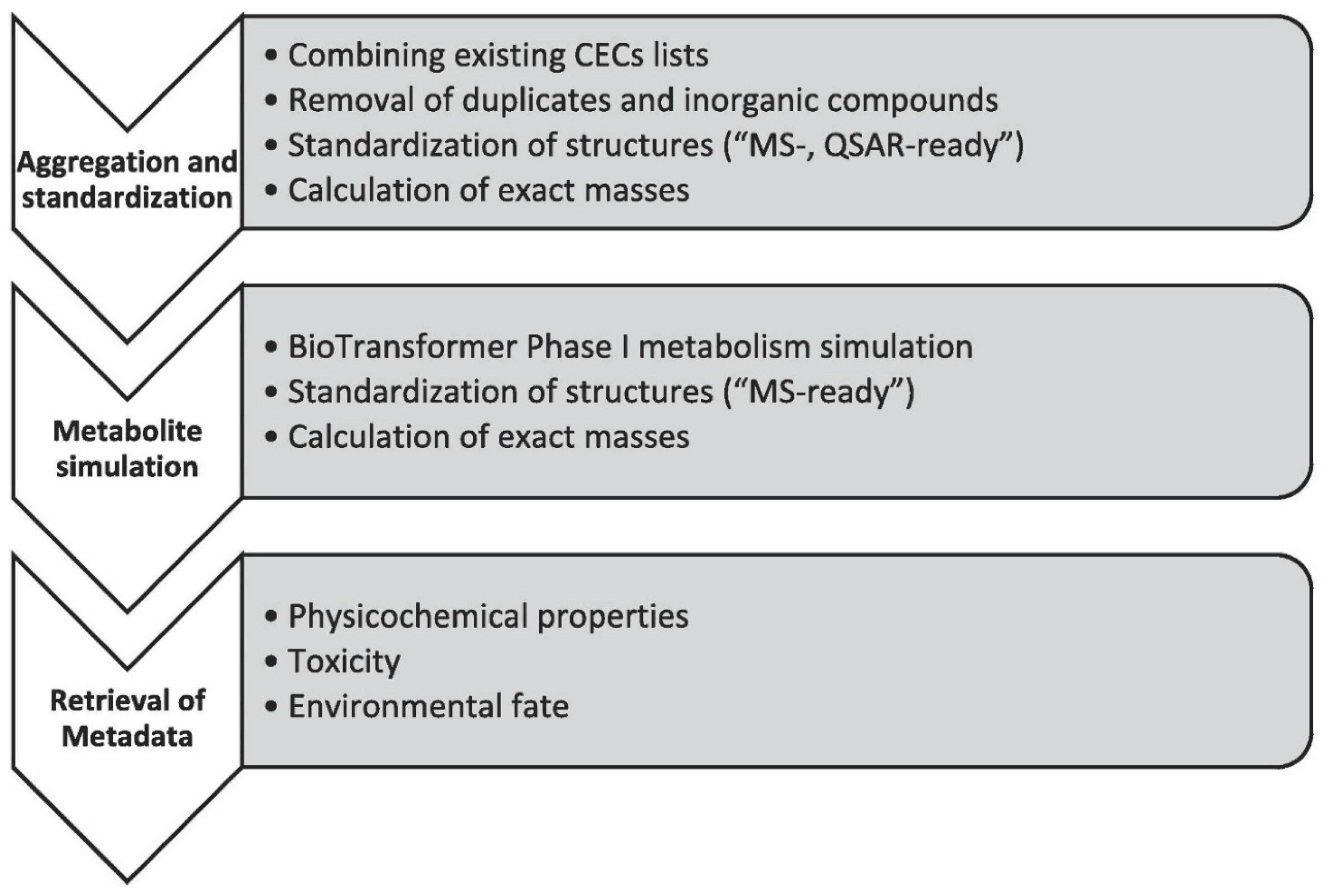

39]. Advanced computational techniques and empirical databases allowed structural annotation and the detection of transformation products at ultra-trace levels. This study demonstrates the power of combining in silico tools and empirical data for robust, high-confidence contaminant analysis in complex environmental matrices. Meijer et al. developed the CECscreen database, an extensive resource for annotating chemicals of emerging concern (CECs) in non-targeted high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) studies. This database aggregates over 70,000 "MS-ready" structures and includes simulated Phase I metabolites, expanding its applicability for exposome research. Advanced computational tools were used for structural standardization, physicochemical property prediction, and metabolite simulation, ensuring reliable annotations [

40]. Integration with bioinformatics platforms like MetFrag facilitates chemical identification and prioritization based on environmental and toxicological relevance. This approach addresses challenges in data analysis, offering a robust solution for identifying known and unknown CECs in complex biological matrices.

Figure 4 illustrates the three-step workflow for developing the CECscreen database for chemicals of emerging concern (CECs). The first step, aggregation and standardization, involves combining existing CEC lists, removing duplicates and inorganic compounds, standardizing structures into "MS-ready" and "QSAR-ready" formats, and calculating exact masses. The second step focuses on metabolite simulation using BioTransformer to predict Phase I metabolites and standardize their structures. The final step retrieves metadata, including physicochemical properties, toxicity, and environmental fate, to support comprehensive chemical annotation in HRMS-based studies.

Despite these advances, several challenges hinder the interpretation of results and ensure reproducibility. Variations in sample preparation methods, instrumental settings, and data processing workflows can lead to inconsistencies between studies. Moreover, the lack of standardization in reporting MS data, including library matching criteria and ion fragmentation patterns, further complicates cross-study comparisons. Ensuring reproducibility requires the adoption of standardized protocols, rigorous quality control measures, and the development of open-access databases that allow researchers to share and validate their findings. Such databases can also serve as reference tools for the identification of unknown compounds, fostering collaboration and improving the reliability of MS-based EC studies.

8. Future Trends and Perspectives

Future trends in mass spectrometry (MS) for emerging contaminant (EC) analysis are set to revolutionize environmental monitoring through technological and digital advancements. High-resolution and hybrid MS technologies, such as Orbitrap and time-of-flight (TOF) systems, are continually evolving, offering enhanced sensitivity, mass accuracy, and dynamic range for detecting trace-level contaminants in complex matrices. These advancements enable improved non-targeted screening and identification of both known and unknown contaminants, facilitating comprehensive environmental surveillance [

41,

42].

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning into MS workflows is another transformative trend. These digital tools can automate peak identification, classify compounds, and predict transformation products based on large datasets, significantly reducing manual data processing time while enhancing accuracy. AI-driven algorithms are already being explored for pattern recognition, source apportionment, and predictive modeling of contaminant behavior and fate in various environmental compartments [

43].

Moreover, MS is emerging as a critical tool in predictive and preventive environmental monitoring, aiding in early identification of pollutants and assessing their ecological and health risks. By enabling the detection of contaminants at ultra-trace levels and revealing transformation pathways, MS supports the development of mitigation strategies and policy interventions. For example, real-time MS-based monitoring of air and water quality can provide actionable data to prevent environmental crises, making it an invaluable tool for achieving sustainable environmental management goals [

44].

These advancements underscore the role of MS in addressing the growing challenges posed by ECs, bridging the gap between analytical science and environmental protection, and supporting global efforts to safeguard ecosystems and public health.

9. Conclusion

Emerging contaminants (ECs) present significant environmental and health challenges due to their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and often-unknown toxicological effects. Addressing these challenges requires robust analytical tools, with mass spectrometry (MS) standing out as a pivotal technology for detecting, identifying, and quantifying ECs across diverse environmental matrices. The versatility of MS techniques, including GC-MS, LC-MS, PTR-MS, and HR-MS, has enabled unparalleled sensitivity and specificity, supporting the monitoring of contaminants at trace levels and advancing our understanding of their environmental behavior and impacts.

This review highlights the critical role of MS in environmental monitoring, from the real-time analysis of volatile organic compounds to the non-targeted identification of unknown pollutants. Despite its effectiveness, challenges such as matrix interferences, standardization gaps, and the need for comprehensive spectral libraries persist. These issues underline the importance of continued innovation in sample preparation methods, MS technologies, and data analysis approaches to improve the reliability and reproducibility of results. Looking forward, advancements in MS instrumentation, combined with the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning, promise to revolutionize environmental monitoring. These technologies will enable more efficient data interpretation, predictive modeling of contaminant behavior, and the development of targeted mitigation strategies. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and supporting regulatory efforts, MS will continue to play a vital role in addressing the complex issues posed by ECs, ensuring the protection of ecosystems and human health.

Author Contributions

AM conceived the idea, conducted the literature search and wrote the manuscript. AZ organized the content and did proofreading of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sauvé, S.; Desrosiers, M. A review of what is an emerging contaminant. Chem. Cent. J. 2014, 8, 15. [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Carrillo, M.; Abrell, L.; Ramírez-Hernández, J.; Reyes-López, J.A.; Carreón-Diazconti, C. Pharmaceuticals as emerging contaminants in the aquatic environment of Latin America: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 44863–44891. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sridharan, S.; Sawarkar, A.D.; Shakeel, A.; Anerao, P.; Mannina, G.; Sharma, P.; Pandey, A. Current research trends on emerging contaminants pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs): A comprehensive review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 859. [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Estrada, C.; Rostro-Alanis, M.d.J.; Muñoz-Gutiérrez, B.D.; Iqbal, H.M.; Kannan, S.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Emergent contaminants: Endocrine disruptors and their laccase-assisted degradation – A review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 612, 1516–1531. [CrossRef]

- Nuro, A. Emerging contaminants; BoD–Books on Demand, 2021.

- Nika, M.-C.; Alygizakis, N.; Arvaniti, O.S.; Thomaidis, N.S. Non-target screening of emerging contaminants in landfills: A review. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Heal. 2022, 32. [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Deng, Y.; Yang, F.; Miao, Q.; Ngien, S.K. Systematic Review of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs): Distribution, Risks, and Implications for Water Quality and Health. Water 2023, 15, 3922. [CrossRef]

- Raghav, M.; Eden, S.; Mitchell, K.; Witte, B. Contaminants of emerging concern in water. Water Resources Research Center College of Agriculture and Life Sciences 2013, 2648.

- Chen, X.; Qadeer, A.; Liu, M.; Deng, L.; Zhou, P.; Mwizerwa, I. T.; Liu, S.; Ajmal, Z.; Xingru, Z.; Jiang, X. Bioaccumulation of emerging contaminants in aquatic biota: PFAS as a case study. In Emerging Aquatic Contaminants, Elsevier, 2023; pp 347-374. [CrossRef]

- Saidulu, D.; Gupta, B.; Gupta, A.K.; Ghosal, P.S. A review on occurrences, eco-toxic effects, and remediation of emerging contaminants from wastewater: Special emphasis on biological treatment based hybrid systems. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9, 105282. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Naushad, M.; Govarthanan, M.; Iqbal, J.; Alfadul, S.M. Emerging contaminants of high concern for the environment: Current trends and future research. Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112609. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Španěl, P.; Demarais, N.; Langford, V.S.; McEwan, M.J. Recent developments and applications of selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry (SIFT-MS). Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2023, e21835. [CrossRef]

- Karasek, F. W.; Clement, R. E. Basic gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: principles and techniques; Elsevier, 2012.

- Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Francis, L. Handbook of LC-MS bioanalysis: best practices, experimental protocols, and regulations. 2013.

- Langford, V.; McEwan, M. J.; Perkins, M. High-throughput analysis of volatile compounds in air, water, and soil using SIFT-MS. 2018.

- Majchrzak, T.; Wojnowski, W.; Lubinska-Szczygeł, M.; Różańska, A.; Namieśnik, J.; Dymerski, T. PTR-MS and GC-MS as complementary techniques for analysis of volatiles: A tutorial review. 2018, 1035, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Shyamalagowri, S.; Shanthi, N.; Manjunathan, J.; Kamaraj, M.; Manikandan, A.; Aravind, J. Techniques for the detection and quantification of emerging contaminants. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, 2191–2218. [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Huang, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, B.; Xie, D.; Huang, K.; Wang, R. Reproducibility in nontarget screening (NTS) of environmental emerging contaminants: Assessing different HLB SPE cartridges and instruments. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 912, 168971. [CrossRef]

- Kravos, A.; Prosen, H. Exploration of novel solid-phase extraction modes for analysis of multiclass emerging contaminants. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1319, 342955. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, K.; Sharma, N.; Gautam, P. B.; Sharma, R.; Mann, B.; Pandey, V. Chromatography. In Advanced Analytical Techniques in Dairy Chemistry, Springer, 2022; pp 11-83. [CrossRef]

- Merone, G.M.; Tartaglia, A.; Rosato, E.; D’ovidio, C.; Kabir, A.; Ulusoy, H.I.; Savini, F.; Locatelli, M. Ionic Liquids in Analytical Chemistry: Applications and Recent Trends. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2021, 17, 1340–1355. [CrossRef]

- Soylak, M.; Ozalp, O.; Uzcan, F. Magnetic nanomaterials for the removal, separation and preconcentration of organic and inorganic pollutants at trace levels and their practical applications: A review. 2020, 29, e00109. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yue, S.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, K.; Wang, P.; Zhan, S. Application of molecularly imprinted polymers in the water environmental field: A review on the detection and efficient removal of emerging contaminants. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 27. [CrossRef]

- Sereshti, H.; Duman, O.; Tunç, S.; Nouri, N.; Khorram, P. Nanosorbent-based solid phase microextraction techniques for the monitoring of emerging organic contaminants in water and wastewater samples. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, M.V.; Postigo, C.; Monllor-Alcaraz, L.S.; Barceló, D.; de Alda, M.L. A reliable LC-MS/MS-based method for trace level determination of 50 medium to highly polar pesticide residues in sediments and ecological risk assessment. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019, 411, 7981–7996. [CrossRef]

- Picó, Y.; Barceló, D. Transformation products of emerging contaminants in the environment and high-resolution mass spectrometry: a new horizon. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 6257–6273. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Baduel, C. Optimization and validation of an extraction method for the analysis of multi-class emerging contaminants in soil and sediment. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1710, 464287. [CrossRef]

- Salthammer, T.; Hohm, U.; Stahn, M.; Grimme, S. Proton-transfer rate constants for the determination of organic indoor air pollutants by online mass spectrometry. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 17856–17868. [CrossRef]

- Aly, N.A.; Dodds, J.N.; Luo, Y.-S.; Grimm, F.A.; Foster, M.; Rusyn, I.; Baker, E.S. Utilizing ion mobility spectrometry-mass spectrometry for the characterization and detection of persistent organic pollutants and their metabolites. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 414, 1245–1258. [CrossRef]

- Raths, J.; Pinto, F.E.; Janfelt, C.; Hollender, J. Elucidating the spatial distribution of organic contaminants and their biotransformation products in amphipod tissue by MALDI- and DESI-MS-imaging. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 264, 115468. [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Lv, Y.; Bi, W.; Chen, D.D.Y. Sorbent and solvent co-enhanced direct analysis in real time-mass spectrometry for high-throughput determination of trace pollutants in water. Talanta 2020, 208, 120378. [CrossRef]

- Moneta, B.G.; Aita, S.E.; Barbaro, E.; Capriotti, A.L.; Cerrato, A.; Laganà, A.; Montone, C.M.; Piovesana, S.; Scoto, F.; Barbante, C.; et al. Untargeted analysis of environmental contaminants in surface snow samples of Svalbard Islands by liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 858, 159709. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, L.; Zheng, M.; Liu, G. Application of non-target screening by high-resolution mass spectrometry to identification and control of new contaminants: Implications for sustainable industrial development. Sustain. Horizons 2023, 5. [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, A.M. Analytical Methods for the Determination of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Solid and Liquid Environmental Matrices: A Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 3900. [CrossRef]

- Nazar, N.; Athira, A.; Krishna, R.D.; Panda, S.K.; Banerjee, K.; Chatterjee, N.S. Large scale screening and quantification of micropollutants in fish from the coastal waters of Cochin, India: Analytical method development and health risk assessment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 954, 176515. [CrossRef]

- Peris, A.; Eljarrat, E. Multi-residue Methodologies for the Analysis of Non-polar Pesticides in Water and Sediment Matrices by GC–MS/MS. Chromatographia 2021, 84, 425–439. [CrossRef]

- Jasrotia, R.; Langer, S.; Dhar, M. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals in Aquatic Ecosystem: An Emerging Threat to Wildlife and Human Health. Proc. Zoöl. Soc. 2021, 74, 634–647. [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zeisel, S. H. Spectral deconvolution for gas chromatography mass spectrometry-based metabolomics: current status and future perspectives. Computational and structural biotechnology journal 2013, 4 (5), e201301013. [CrossRef]

- Eysseric, E.; Beaudry, F.; Gagnon, C.; Segura, P.A. Non-targeted screening of trace organic contaminants in surface waters by a multi-tool approach based on combinatorial analysis of tandem mass spectra and open access databases. Talanta 2021, 230, 122293. [CrossRef]

- Meijer, J.; Lamoree, M.; Hamers, T.; Antignac, J.-P.; Hutinet, S.; Debrauwer, L.; Covaci, A.; Huber, C.; Krauss, M.; Walker, D.I.; et al. An annotation database for chemicals of emerging concern in exposome research. Environ. Int. 2021, 152, 106511. [CrossRef]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Singer, H.P.; Slobodnik, J.; Ipolyi, I.M.; Oswald, P.; Krauss, M.; Schulze, T.; Haglund, P.; Letzel, T.; Grosse, S.; et al. Non-target screening with high-resolution mass spectrometry: critical review using a collaborative trial on water analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 6237–6255. [CrossRef]

- Hollender, J.; van Bavel, B.; Dulio, V.; Farmen, E.; Furtmann, K.; Koschorreck, J.; Kunkel, U.; Krauss, M.; Munthe, J.; Schlabach, M.; et al. High resolution mass spectrometry-based non-target screening can support regulatory environmental monitoring and chemicals management. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2019, 31, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A. M.; Zakarya, I. A.; Hasnain, M.; Sarkinbaka, Z. M.; Mukwana, K. C.; Abdo, A. Potential Breakthroughs in Environmental Monitoring and Management. In Harnessing AI in Geospatial Technology for Environmental Monitoring and Management, IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2025; pp 239-282. [CrossRef]

- Valbonesi, P.; Profita, M.; Vasumini, I.; Fabbri, E. Contaminants of emerging concern in drinking water: Quality assessment by combining chemical and biological analysis. 2020, 758, 143624. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).