1. Introduction

The green algae

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii contains 12–14 carbonic anhydrases (CAs) localized in almost all compartments of the cell and belonging to three independent families of the enzyme, α, β, and γ [

1,

2,

3]. Many of them, in cooperation with inorganic carbon (C

i) transporters and other additional proteins, are involved in the operation of the carbon-concentrating mechanism (CCM), increasing the intracellular pool of C

i under low and very low CO

2 environmental conditions [

4,

5,

6], while the roles of other CAs are still unclear or discussed.

The first CA found in

C. reinhardtii cells was the periplasmic CAH1, significantly accumulated under low CO

2 conditions simultaneously with a high increase of total CA activity [

7]. The specific CA activity of the CAH1 protein isolated with affinity chromatography was established within the range of 2000–2580 Wilbur-Anderson Units (WAU) mg

–1 [

7,

8], which was near a quarter of activity obtained for bovine CAII (bCAII), which is one of the standard references in studies with CAs [

9,

10]. In 1992, another, but closely related to CAH1 (~92% similarity), periplasmic CAH2 was isolated with ~1.5 times higher CA activity. However, the maximum amount of CAH2 protein (under high CO

2 conditions) was ~90 times less than that of the CAH1 protein [

8]. Thus, it was assumed for a long time that the main CA activity of algal cells is localized in the periplasmic space and related to highly active enzyme CAH1.

The data about the chloroplast-localized CA activity in

C. reinhardtii cells were also obtained at the beginning of the 1990s (see in [

9]), however the fact that the main contribution to the total CA activity of the algae cell came from periplasmic CAs was not in doubt then. Around 1998, the third CA named CAH3 with relatively high enzymatic activity was identified and isolated by Karlsson and colleagues [

11,

12]. On the one hand, the immature CAH3 protein had two transport peptides clearly indicating its localization inside the thylakoids (i.e., in the lumen). On the other hand, the CA activity of CAH3 was high (~1260 WAU mg

–1) [

12] and close to that observed for CAH1 (for more details see [

9]). In contrast to both periplasmic CAs (CAH1 and CAH2), the expression level of the gene encoding CAH3, as well as the content of the protein, were not strongly dependent on CO

2 conditions of algal growth [

13,

14,

15].

In spite of the fact that CAH3 is a lumenal protein, its role in CCM was immediately proposed through the possible CA dehydration activity (HCO

3– + H

+ → H

2O + CO

2), which can result in the pass of CO

2 formed in the reaction across the thylakoid membrane of the tubules (the thylakoids penetrating the pyrenoid) to the pyrenoid matrix [

11]. However, the role of CAH3 in supporting high photochemical activity of photosystem II (PSII) was also suggested in parallel, based on the observed results [

11]. Further studies with the use of PSII-enriched membrane preparations isolated from wild type (WT)

C. reinhardtii indeed showed the presence of a high amount of CAH3 protein in them [

9,

16,

17,

18,

19]. To date, the dual role of CAH3 is still discussed by researchers, which was summarized in the recent review [

9].

To study the involvement of CA activity of CAH3 in supporting the high photosynthetic function of PSII, the recombinant protein (rCAH3) was purified and used in experiments with PSII isolated from the CAH3-deficient mutant

cia3 [

17]. The data showed that under C

i-free conditions, CA activity of CAH3 could provide more than 70% stimulation of O

2 evolution rate of PSII from

cia3 with the addition of very low HCO

3– concentrations. The location of its acting was proposed as being in the close vicinity to the PSII donor (lumenal) side. Biochemical studies showed the complete binding of added rCAH3 to the fraction of PSII-enriched membranes, as well as the requirement of the ratio of rCAH3 to PSII as 1 : 1 for achieving a higher stimulation effect on O

2 evolving activity of PSII [

17].

The accumulation of purified rCAH3 allowed the crystallization of the protein [

20], while it was possible only in the presence of a high amount of dihydrogen phosphate ions or the CA inhibitor acetazolamide. The results showed the formation of four dimers of rCAH3 per unit cell. Nevertheless, a single rCAH3 monomer was characterized by architecture similar to other α-CAs: the central core formed by the β-sheet, two α-helices placed at the side of the molecule, the catalytic center formed by a Zn

2+ ion bound by three histidine residues and a water molecule in a tetrahedral geometry [

20]. The rCAH3 molecule structure showed a broader cavity with the absence of the N-acetamido group, which results in structural and electrostatic changes making the protein surface more hydrophobic [

20], which is probably necessary for the formation of interaction with the PSII complex.

As it was calculated from the data of O

2 evolving activity of PSII in

C. reinhardtii, the flow of protons from the water-oxidizing complex to the lumen in the light is extremely high [

19]. Thus, to avoid local acidification that could suppress the function of the active center of the water-oxidizing complex [

17], the dehydration CA activity of CAH3 should fully cover it. In the present study the purification of rCAH3 showed CA activity comparable to that of bCAII and long-term sustainability was performed. Detected values ~11 times higher indicated how much the enzymatic activity of CAH3 had been underestimated in the previous works.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Algal Growth Conditions

The

C. reinhardtii strain CC-503 (cw92), which is a cell-deficient mutant [

21,

22] usually used as a standard wild type in photosynthetic studies, was grown at 25 °C in a 1 L bottle under aeration with 5% CO

2 and continuous illumination with LED lamps of cool-light spectra (6500 K) with light intensity of ~100 µmol photons m

–2 s

–1 according to described previously [

21,

23].

2.2. Total RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

Isolation of total RNA was performed with the Aurum Total RNA Mini Kit (BioRad, USA) with modifications. For cell disruption, 0.5 ml of a suspension of harvested algal cells (5000 g, 3 min) was frozen in liquid nitrogen and mixed with 0.7 ml of RIZol reagent (Dia-M, Russia) containing β-mercaptoethanol immediately after thawing. The mixture was vortexed and the lysate centrifuged for 3 min at 10000 g. The supernatant was mixed with 0.7 ml of 70% ethanol and loaded onto an RNA-binding column from the Kit. Further steps were performed according to the supplied manual. On the final step, the Elution solution was loaded onto the column for 1 min and total RNA was eluted with centrifugation (10000 g, 2 min). The samples of total RNA were stored at –70 °C.

Synthesis of cDNA was performed with the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the supplied manual with the use of the primer complimentary to 3’-end of the cah3 gene (CTAGCACACTCGTGTCCGC). The samples of cDNA were stored at –20 °C.

2.3. Cloning of the cah3 Gene

The cah3 gene of C. reinhardtii without the signal sequence (1–72 a.a.) was cloned into the pET-19mod, pET-32b(+), and pQE-30 plasmids. The following primers for amplification of the cah3 gene were used: cahFe1 TTTTAGATCTGGAGAATCTTTATTTTCAGGGCGCAGCTTGGAACTATGGCGAAGTT and cahRe1 TAGCACCTCGAGGTCCGCTCACAGCTCGTA for cloning into pET-32b(+), cahFe2 AGTCATATGGCAGCTTGGAACTATGGCGAAGTT and cahRe2 AGTGGATCCTCACAGCTCGTATTCGACCAGG for cloning into pET-19mod, and cahFe3 AGTGGATCCGCAGCTTGGAACTATGGCGAAGTT and cahRe3 AGTAAGCTTTCACAGCTCGTATTCGACCAGG for cloning into pQE-30. Cleavage sites for restriction endonucleases are presented in italic, introduced site for TEV-protease are underscored. The cDNA was used as a template.

PCR amplification program was as follows: (1) initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s; (2) 35 cycles as follows: denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 50 °C for 30 s, elongation at 72 °C for 45 s; (3) final elongation at 72 °C for 2 min. Using the designed primers, the target PCR products were amplified and purified using a commercial kit (diaGene, Russia). The correctness of amplicons were verified by sequencing.

The BamHI/HindIII-digested amplicon was cloned into pQE-30 (Qiagen, Germany). Plasmid pQE::cah3 was used to transform E. coli M15[pREP4] competent cells. The NdeI/BamHI- and Bgl II/XhoI-digested amplicons was cloned into pET-19mod and pET-32b(+), correspondingly. Plasmid pET19::cah3 and pET32::cah3 were used to transform E. coli DH5α competent cells. Transformants were selected on LB plates containing 100 µg ampicillin/ml. Insertion plasmids were obtained from the overnight culture of E.coli transformants. Sequences of cloned genes were verified by sequencing.

2.4. Recombinant CAH3 Purification

For the production of rCAH3, strain E. coli M15[pREP4] was transformed with pQE::cah3; strain E. coli Origami B(DE3) was transformed with pET19::cah3 and pET32::cah3 plasmids. All strains were grown at 37 °C with agitation at 250 rpm to a cell density of 0.6–0.8 at 600 nm. Then, 0.9 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside was added to the culture medium and the cells were incubated for 18 h at 16 °C with agitation at 100 rpm. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 4000 g for 30 min, suspended in 35 ml of 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), containing 0.5 M NaCl and 1 mM imidazole (buffer 1) and disrupted by sonication. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (90 min at 9000 g). The protein was purified by affinity chromatography on a HisTrap 5-ml column (GE Healthcare, USA). Cell extract was loaded onto a HisTrap column equilibrated with buffer 1, washed with six volumes of the buffer 1 and then washed with six volumes of the buffer 2 (20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.5 M NaCl, 50 mM imidazole). Fractions containing the rCAH3 were eluted with buffer 3 (20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.5 M NaCl, 300 mM imidazole). After the chromatography stage, the protein was dialyzed against 20 mM Tris (pH 9.0) buffer with 0.5 M NaCl (unless otherwise mentioned). The concentration of the protein was determined using the molar extinction at 280 nm (ε = 26.39 M−1 cm−1) calculated from the protein sequence using Vector NTI Program (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

2.5. SDS-PAGE Electrophoresis and Western Blot

PAGE under denaturation conditions and Western-blot analysis was carried out as described previously [

18,

19,

23] in 12.5% SDS-PAAG using the Mini-PROTEAN 3 Cell (Bio-Rad, USA) and the primary antibodies against CAH3 (Agrisera, Sweden, AS05 073). Specific modifications of the approaches indicated on the related figures and their descriptions.

2.6. CO2 Hydration Activity Measurements

CA activity was measured at 0 °C in the 3-ml thermostatic chamber as the time of the shift in pH value from 8.3 to 7.8 induced by addition of cold CO2-saturated water to the reaction mixture, containing 25 mM Tris (pH 8.5). The saturation of water by CO2 was carried out on ice by passing the gas through the medium in a 100 ml glass cylinder for at least one hour and during the entire period of the measurement. The added part of CO2-saturated water was 40% from the total volume of the reaction mixture. CO2 hydration activity was expressed in Wilbur-Anderson Units (WAU) and calculated according to the equation WAU = (t0–t)/t, where t0 and t were the times required for pH decrease in the absence and in the presence of CA in the reaction mixture. Obtained CA activities were calculated per mg of protein (WAU mg–1).

2.7. Esterase Activity Measurements

Esterase activity was measured according to the protocol described previously [

24] as the acceleration of

p-nitrophenylacetate (

p-NPA) hydrolysis detected by the increase in absorption at 348 nm [

25]. Fresh 3mM solution of

p-NPA was prepared every day as follows: 5.43 mg of

p-NPA was dissolved in 0.3 ml of acetone after that water was carefully added with stirring up to the final volume of 10 ml. To obtain 1 ml of the reaction mixture in the cuvette 0.42 ml of water was mixed with 0.33 ml of

p-NPA solution (1 mM) and 0.25 ml of 1M buffer (25 mM). Measurement was started after 1 min of incubation and absorption at 348 nm was detected every minute during 7 min. Esterase activity was expressed in units (U), which are related to the absorption increase by 0.001 per 5 min after subtraction of values of non-enzymatic changes [

24]. The measurement was conducted at room temperature. Obtained esterase activities were calculated as U per mg of protein (U mg

–1).

2.8. pH-Dependence Measurements

In all pH-dependent studies, the samples of rCAH3 were diluted fourfold by 0.1 M Britton–Robinson buffer with different pH values (4.0–10.0).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the standard algorithms of OriginPro (2016) (OriginLab, Northampton, USA). The data are presented as means ± SD.

4. Discussion

CAH3 was the third α-CA found in

C. reinhardtii by Karlsson and colleagues [

11,

12] in addition to the known and well-characterized CAH1 and CAH2 located in the periplasmic membrane of the algal cell [

7,

8]. The CO

2 hydration activity detected in the precipitated fraction enriched by native CAH3 was ~1260 WAU mg

–1 [

12], which was relatively high. However, this was much lower compared to known activities of CAH1 and CAH2. Following attempts to purify recombinant protein of CAH3 led to the obtaining of the enzyme [

26] with significantly lower CA activity (by 1.7–4.2 times) compared to the native protein. Nevertheless, rCAH3 was able to stimulate up to 80% of the O

2-evolving activity of PSII isolated from the

cia3 mutant (deficient in CAH3 in the thylakoid lumen) at extremely low bicarbonate concentrations [

17]. This indicated the importance of CAH3 activity for optimal function of the photosynthetic apparatus of

C. reinhardtii on the level of PSII.

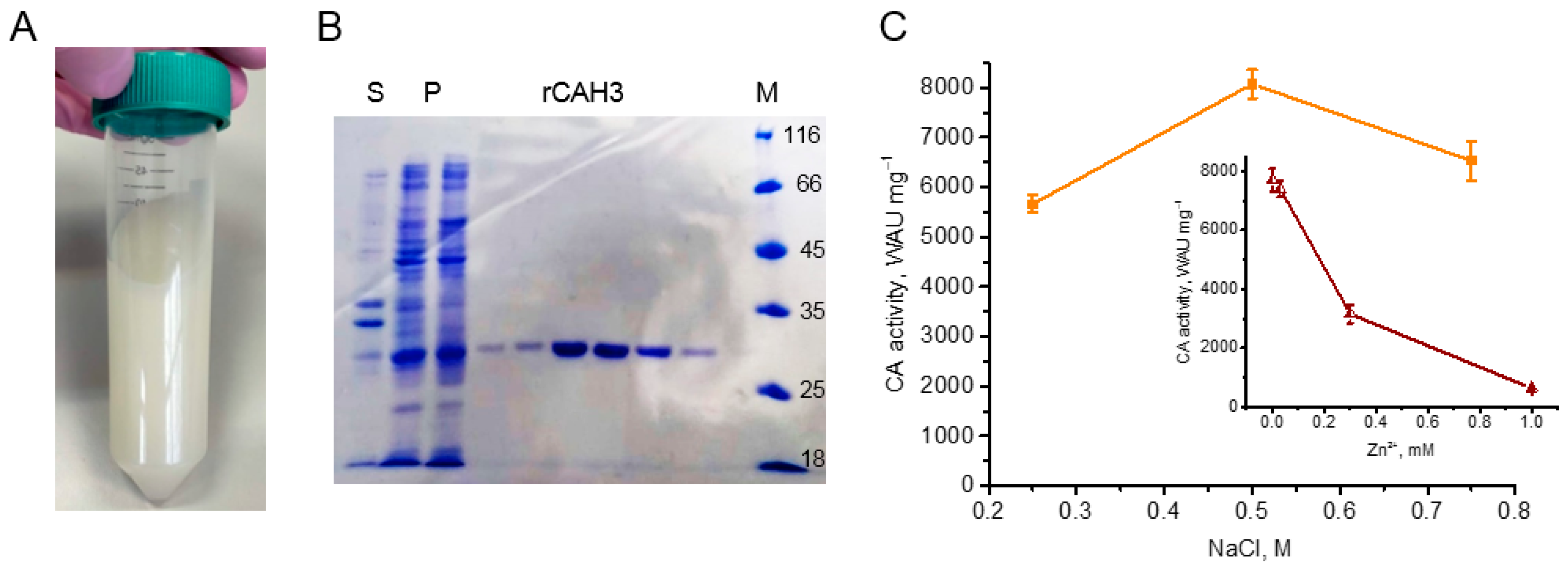

During the production of rCAH3 in the present study, the transformation of

E. coli strains by different plasmids containing the catalytic fragment of CAH3, including the combination similar to those used in previous studies [

17,

20,

26], resulted in high accumulation of rCAH3 in cells in all variants (

Figure 1A,B)). However, rCAH3 was prone to complete precipitation into an insoluble fraction during accumulation in cells. The only use of the pET-19mod plasmid and the

E. coli Origami B(DE3) strain for transformation made it possible to obtain an enough amount of rCAH3 in the soluble fraction. An additional requirement to obtain maximum activity of rCAH3 was the presence of 0.5 M NaCl in the dialysis buffer (

Figure 1C,

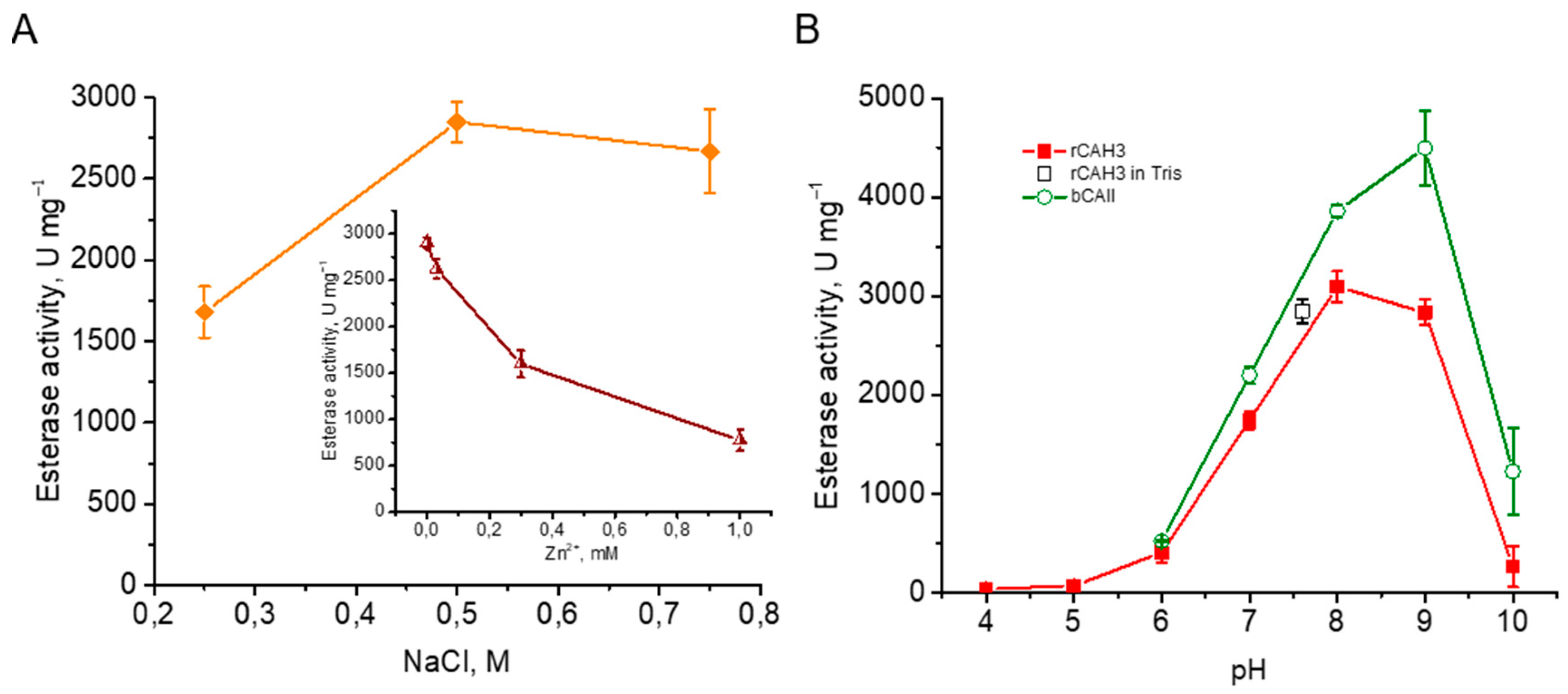

Figure 6A).

The maximum CO

2 hydration activity of purified rCAH3, in turn, was surprisingly high (up to 9000 WAU mg

–1) and much exceeded that obtained in the previous studies by more than 11 times. The measurements with bCAII, performed in parallel, showed that the activity of rCAH3 was ~80% of that. The same high level was observed for the well-determined esterase activity of rCAH3. In this case, the maximum value was also comparable (~70%) to that detected for bCAII in parallel measurements (

Figure 6). Besides, CO

2 hydration activity of rCAH3 was higher than those known for CAH1 and CAH2 by ~3.5 and ~2.7 times, respectively (for comparison see [

9]). Thus, the data indicated, that CAH3, located in the thylakoid lumen, probably could be the most active CA of the

C. reinhardtii cell.

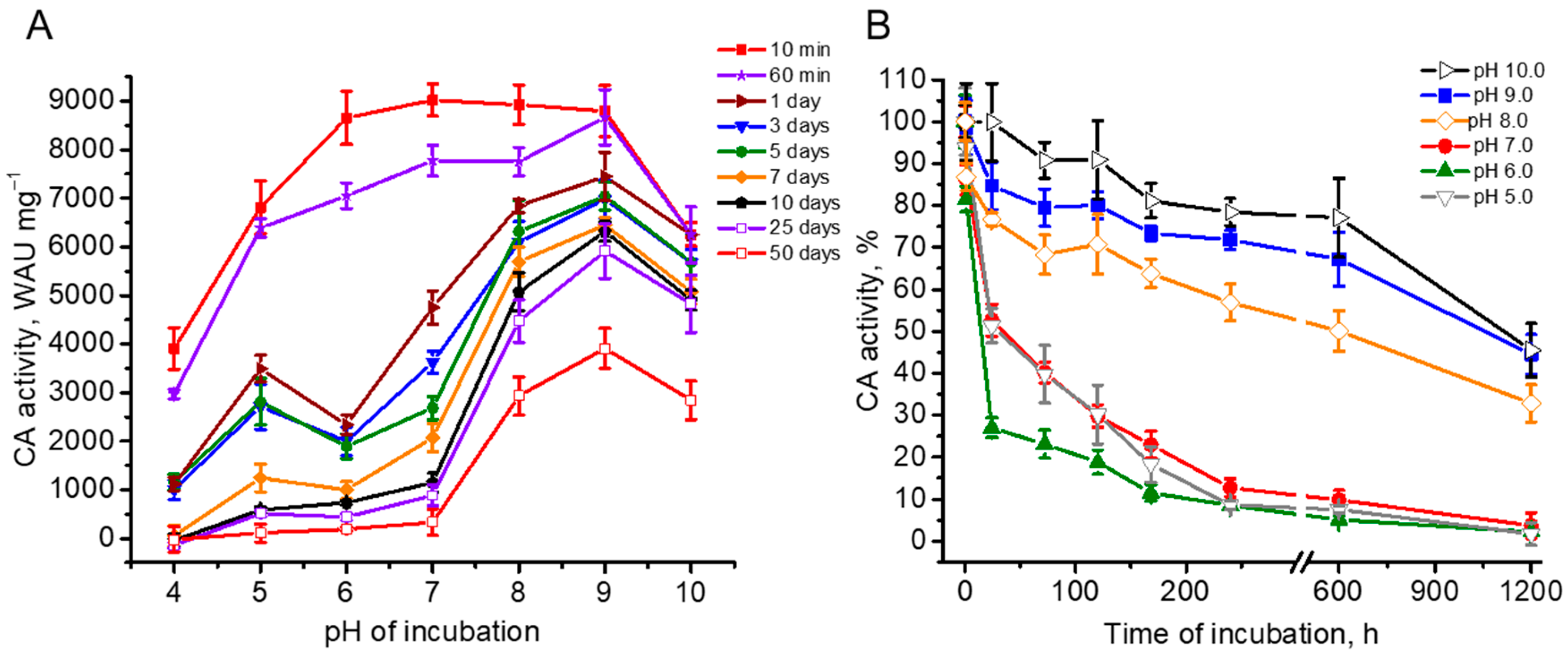

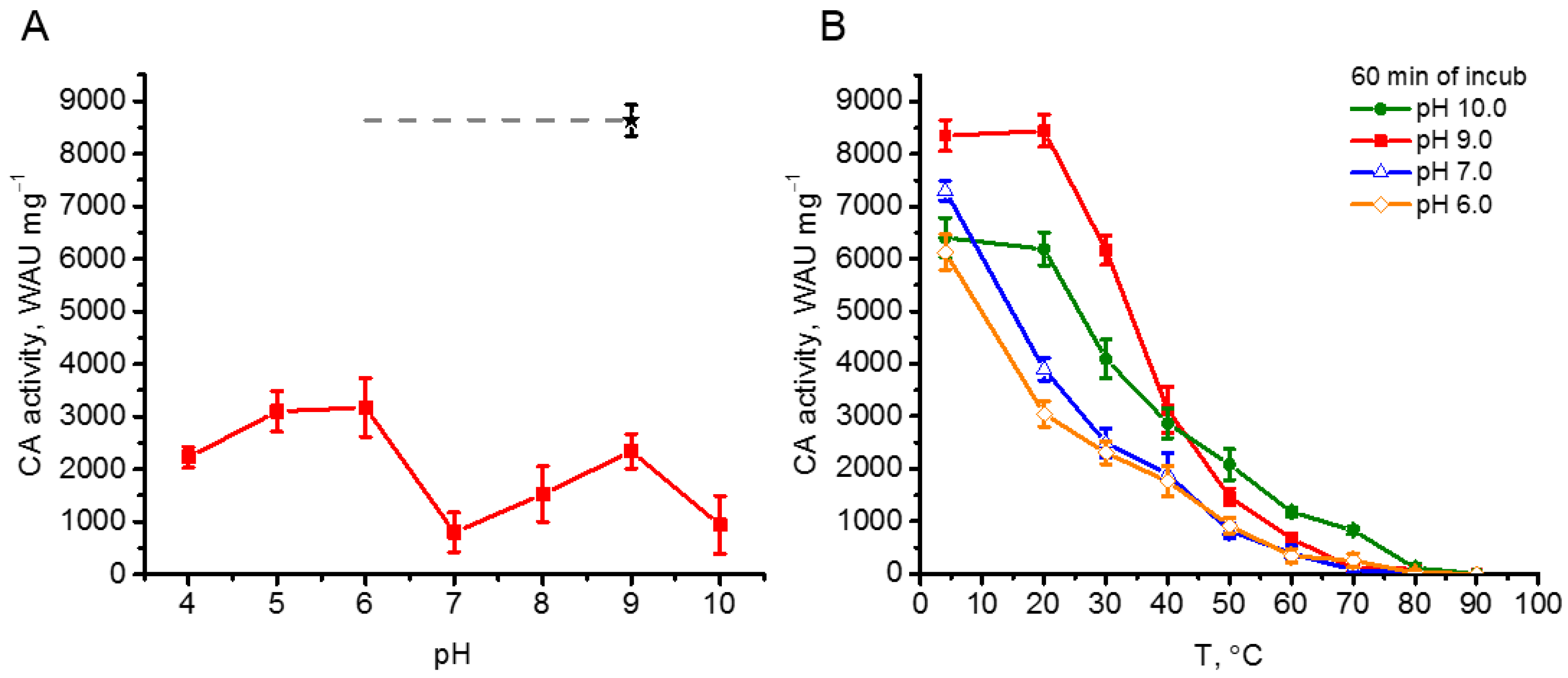

In addition, rCAH3 showed good long-term stability at alkaline pH, maintaining more than half of its CO

2 hydration activity under incubation at 4 °C for up to 50 days (

Figure 3). Similar results were observed during thermoinactivation of the enzyme, which showed higher temperatures for the ~50% decrease of its CA activity under alkaline pH, compared with those at acidic pH (

Figure 4). Surprisingly, these data were in contradiction with the previously published results, which showed the place of the maximum of rCAH3 activity at pH 6.5 with the decrease in values at lower pH 6.0 and higher pH 7.0 [

20]. To verify the pH dependence of enzyme activity of rCAH3 produced in the present study, the esterase activity was measured at pH from 4.0 to 10.0 in comparison with that of bCAII. The results obtained for bCAII were in good agreement with data shown previously [

32]. The maximum activity in the case of rCAH3 indeed was shifted to the acidic side compared to that observed for bCAII, which was consistent with previously published data [

20]. However, the maxima were detected at pH 8.0 and 9.0, respectively, for rCAH3 and bCAII, rather than at pH 6.5 and 7.0 as it was determined by Benlloch and colleagues [

20]. Therefore, the long-term stability of rCAH3 correlated well with the optimal pH of its activity.

It should be noted that the esterase activity of rCAH3 decreased with pH decline and was ~56% at pH 7.0, ~13% at pH 6.0 (~35% at pH 6.5), and only ~2 % at pH 6.0 (~8% at pH 5.5) from that observed at pH 8.0 (

Figure 6B). This was in good agreement with the previous suggestion about the involvement of CA activity of CAH3 in supporting high PSII function at pH close to 7.0 [

18,

19], i.e., in conditions providing relatively high CA activity of rCAH3.

CAH3 has a disulfide bond in its structure [

9,

20] in contrast to bCAII [

30,

31], which does not have it. According to previous reports, the disruption of the disulfide bond by sulfhydryl-reducing chemicals led to significant suppression of the CA activity of rCAH3 [

20,

26]. However, the observed degree of suppression was different between works that used the same chemicals, for example, DTT. Benlloch and colleagues [

20] showed a 50% decrease in rCAH3 activity already at 0.5 mM DTT and almost complete loss of it at 1 mM DTT. In contrast, Mitra and colleagues [

26] indicated a ~80% decrease in rCAH3 activity but at 10 mM DTT. The last value was close to that obtained in the present work (the ~73% decrease) (

Table 1). The suppression of activity in the case of 10 mM β-ME (~0.07%) was almost the same (by ~61%).

The action of Cys was significantly different. In the present study, 10 mM Cys completely inhibited the CA activity of rCAH3, being thus the strongest inhibitor of rCAH3 CA activity found in the study. However, in the work of Mitra and colleagues [

26], the 50% level of inhibition was only achieved by using Cys at the same concentration (the weakest inhibitor). The degree of CA activity suppression by Cys was similar to that observed in the presence of 10 mM DTT when the concentration of Cys was decreased to 0.75 mM (

Table 1).

The presence of 0.75 mM Cys did not decrease CA activity of bCAII, but the addition of 10 mM Cys, as well as DTT, and β-ME led, to its inhibition by 40–50%. This indicated that, besides inhibition of rCAH3 CA activity through the reduction of sulfhydryl groups, other ways of CA activity suppression also exist at such high concentrations of these chemicals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.V.T.; methodology, V.V.T., L.I.T., A.K.S., I.V.T., N.N.R.; validation, V.V.T. and L.I.T.; formal analysis, V.V.T.; investigation, V.V.T., L.I.T., A.K.S., I.V.T., N.N.R.; writing original draft preparation, V.V.T.; writing review and editing, V.V.T..; visualization, V.V.T.; supervision, V.V.T.; project administration, V.V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Main steps of rCAH3 purification. (A) A white staining suspension of E. coli cells with accumulated rCAH3. (B) Results of SDS-PAGE of the samples containing fractions of supernatant (S) and pellet (P) of sonicated E. coli cells, rCAH3 eluted from the Ni-column (rCAH3), and the markers of molecular weights (M). (C) CA activity of rCAH3 purified at different concentrations of NaCl in dialysis buffer, and (insert) the dependence of CA activity of rCAH3 on the Zn2+ presence in the reaction mixture.

Figure 1.

Main steps of rCAH3 purification. (A) A white staining suspension of E. coli cells with accumulated rCAH3. (B) Results of SDS-PAGE of the samples containing fractions of supernatant (S) and pellet (P) of sonicated E. coli cells, rCAH3 eluted from the Ni-column (rCAH3), and the markers of molecular weights (M). (C) CA activity of rCAH3 purified at different concentrations of NaCl in dialysis buffer, and (insert) the dependence of CA activity of rCAH3 on the Zn2+ presence in the reaction mixture.

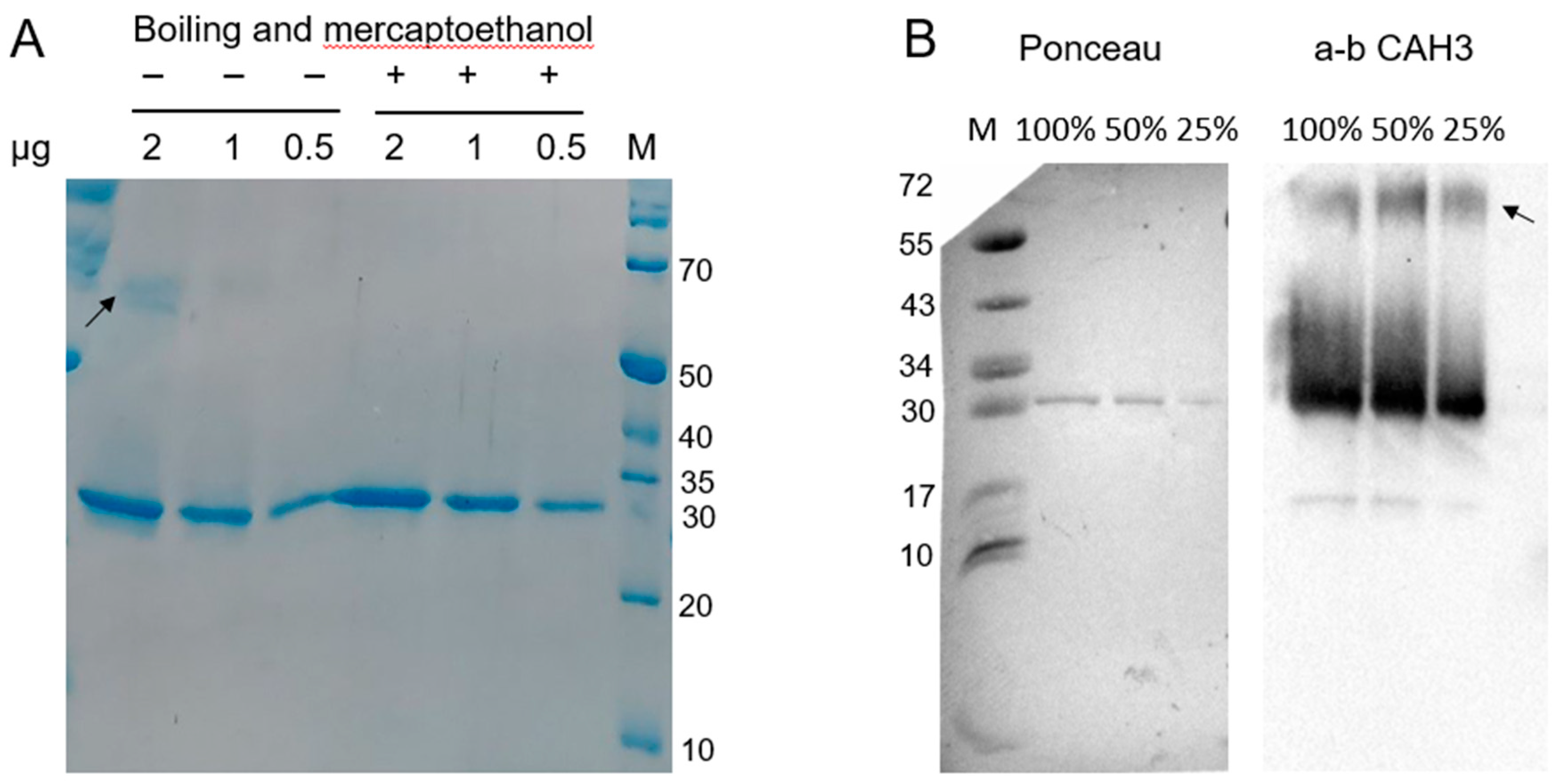

Figure 2.

Results of SDS-PAGE (A) and Western blot analysis with using the primary antibodies against CAH3 (B) obtained for purified rCAH3 protein. The samples were loaded in terms of 2 (100%), 1 (50%), and 0.5 (25%) µg of protein per track, as indicated on top. The exposure time for Western blot detection was 148 s. The arrows indicate the band related to a possible dimer. Staining of the membrane with Ponceau made it possible to visualize the marker bands and the major band of rCAH3.

Figure 2.

Results of SDS-PAGE (A) and Western blot analysis with using the primary antibodies against CAH3 (B) obtained for purified rCAH3 protein. The samples were loaded in terms of 2 (100%), 1 (50%), and 0.5 (25%) µg of protein per track, as indicated on top. The exposure time for Western blot detection was 148 s. The arrows indicate the band related to a possible dimer. Staining of the membrane with Ponceau made it possible to visualize the marker bands and the major band of rCAH3.

Figure 3.

Dependence of CA activity of rCAH3 on the time of incubation at different pH values presented in absolute (A) and relative (B) units. The values obtained after 10 min of incubation were used as 100% for each pH in plot B. The incubation was performed at 4 °C during the entire time of the study. The time on the abscissa axis in (B) is shown in hours for better visualization and the appropriate location of the axis break. The days correspond to the following hours: 1 day is 24 h, 3 days are 72 h, 5 days are 120 h, 7 days are 168 h, 10 days are 240 h, 25 days are 600 h, and 50 days are 1200 h.

Figure 3.

Dependence of CA activity of rCAH3 on the time of incubation at different pH values presented in absolute (A) and relative (B) units. The values obtained after 10 min of incubation were used as 100% for each pH in plot B. The incubation was performed at 4 °C during the entire time of the study. The time on the abscissa axis in (B) is shown in hours for better visualization and the appropriate location of the axis break. The days correspond to the following hours: 1 day is 24 h, 3 days are 72 h, 5 days are 120 h, 7 days are 168 h, 10 days are 240 h, 25 days are 600 h, and 50 days are 1200 h.

Figure 4.

CA activity of rCAH3 under thermoinactivation. (A) CA activity of rCAH3 at different pH values after incubation at 75 °C for 15 min. A black star indicates the initial CA activity at pH 9. (B) The decrease in CA activity of the rCAH3 after incubation at different temperatures for 60 min in mixtures with different pH values.

Figure 4.

CA activity of rCAH3 under thermoinactivation. (A) CA activity of rCAH3 at different pH values after incubation at 75 °C for 15 min. A black star indicates the initial CA activity at pH 9. (B) The decrease in CA activity of the rCAH3 after incubation at different temperatures for 60 min in mixtures with different pH values.

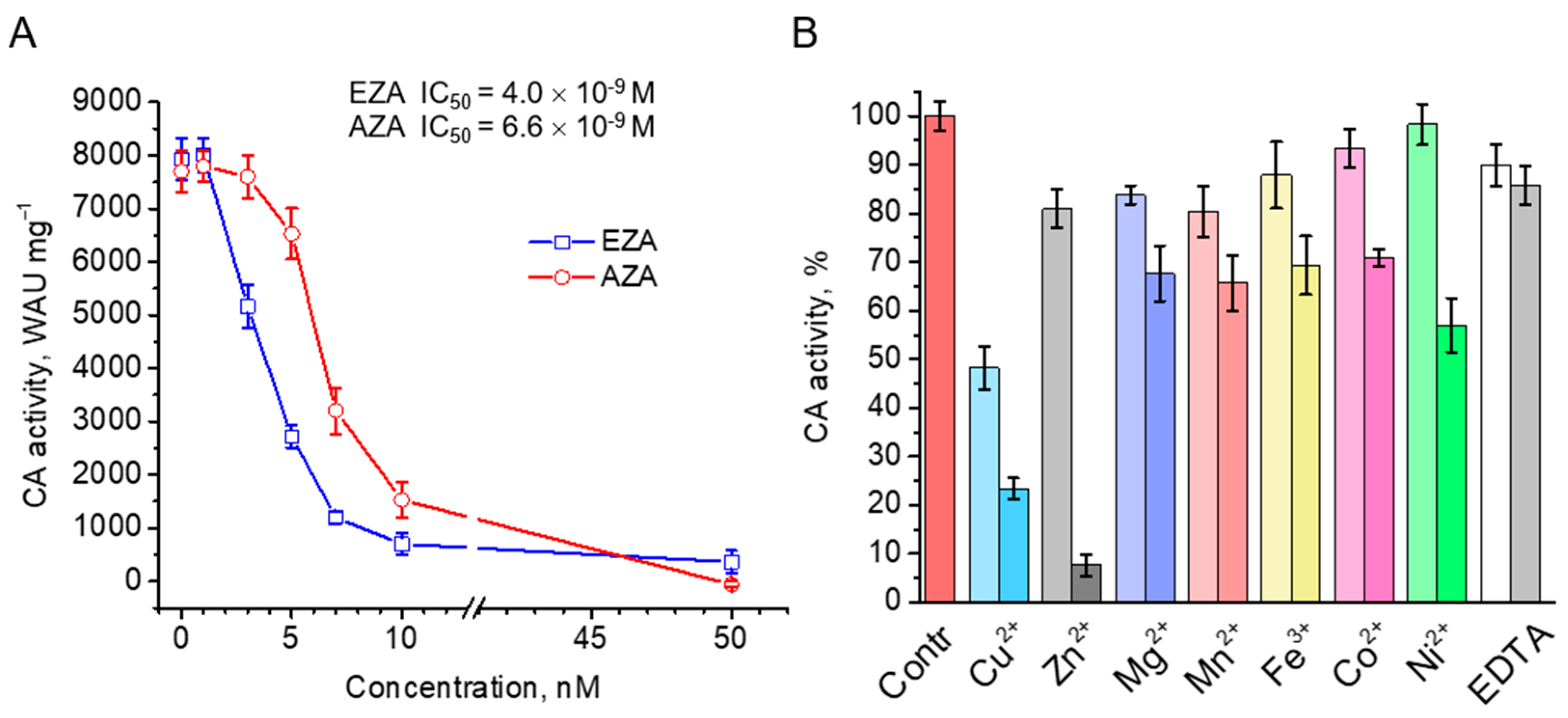

Figure 5.

Inhibition of CA activity of rCAH3 by standard inhibitors ethoxyzolamide (EZA) and acetazolamide (AZA) with indication of the estimated IC50 values (A), and by cations of different metals and EDTA at low (0.1 mM, lighter color) and high (1 mM, darker color) concentrations added to the reaction mixture during measurements (B).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of CA activity of rCAH3 by standard inhibitors ethoxyzolamide (EZA) and acetazolamide (AZA) with indication of the estimated IC50 values (A), and by cations of different metals and EDTA at low (0.1 mM, lighter color) and high (1 mM, darker color) concentrations added to the reaction mixture during measurements (B).

Figure 6.

Esterase activity of rCAH3 measured in Tris buffer (pH 7.6) for samples purified at different concentrations of NaCl in the dialysis buffer (A), the influence of Zn2+ presence on rCAH3 activity in the samples obtained at 0.5 M NaCl (insert), and pH-dependence of the activity measured in Britton–Robinson buffer (B) for rCAH3 and bCAII. The black square shows the value obtained for rCAH3 in Tris buffer (pH 7.6).

Figure 6.

Esterase activity of rCAH3 measured in Tris buffer (pH 7.6) for samples purified at different concentrations of NaCl in the dialysis buffer (A), the influence of Zn2+ presence on rCAH3 activity in the samples obtained at 0.5 M NaCl (insert), and pH-dependence of the activity measured in Britton–Robinson buffer (B) for rCAH3 and bCAII. The black square shows the value obtained for rCAH3 in Tris buffer (pH 7.6).

Table 1.

The rCAH3 CA activity suppression in the presence of 10 mM of different sulfhydryl-reducing chemicals, β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) (~0.07%), dithiothreitol (DTT), and L-cysteine (Cys) indicated as % of the residual activity. For DTT, the incubation at room temperature for 10 min (DTT, RTincub) and incubation at pH 7.0 (DTT, pH 7.0) were applied. The incubation at room temperature for 10 min in the case of Cys was performed for 0.75 mM concentrations (Cys0.75, RTincub). The values obtained in the previous studies are also indicated for comparison.

Table 1.

The rCAH3 CA activity suppression in the presence of 10 mM of different sulfhydryl-reducing chemicals, β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) (~0.07%), dithiothreitol (DTT), and L-cysteine (Cys) indicated as % of the residual activity. For DTT, the incubation at room temperature for 10 min (DTT, RTincub) and incubation at pH 7.0 (DTT, pH 7.0) were applied. The incubation at room temperature for 10 min in the case of Cys was performed for 0.75 mM concentrations (Cys0.75, RTincub). The values obtained in the previous studies are also indicated for comparison.

| |

β-ME |

DTT |

Cys |

Cys0.75 |

DTT, RTincub |

DTT,

pH 7.0

|

Cys0.75,

RTincub

|

reff |

| |

% of the residual activity |

|

| rCAH3 |

39.0±2.8 |

27.2±3.2 |

0 ± 0 |

28.4±1.4 |

25.4±1.8 |

22.7±1.7 |

29.8±1.6 |

this |

| bCAII |

60.9±6.4 |

63.4±9.9 |

42.3±7.6 |

97.1±8.8 |

– |

– |

– |

study |

| |

% of the residual activity after RTincub

|

|

| rCAH3 |

~38 |

~20 |

~50 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

[26] |

| rCAH3 |

|

0 (reaching at ~1.5 mM DTT) |

[20] |