Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

14 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This study presents a novel Mobile Solar Cooling System (MSCS) designed to enhance the cold chain for leafy vegetables by leveraging solar energy for sustainable and cost-effective refrigeration. The MSCS maintained an average storage temperature of 9 ± 4°C and relative humidity of 85 ± 10%, significantly improving the preservation of green amaranth compared to ambient conditions (average temperature: 30 ± 2°C). Key system metrics include a coefficient of performance (COP) of 1.6, indicating efficient energy use, with an average daily energy consumption of 1190 Wh. The system extended the shelf life of green amaranth to 18 days, as opposed to 5 days under ambient storage, while minimizing weight loss, retaining up to 87.25% moisture, and preserving essential nutrients such as Vitamin A (51.35 mg/100 g) and beta carotene (22.49 mg/100 g). The microbial load remained within internationally acceptable limits, with bacterial counts below 10⁵ and fungal counts of 10³-10⁴. This innovative system has the potential to reduce postharvest losses, ensure food safety, and enhance food security in regions with limited access to conventional refrigeration infrastructure. The MSCS is recommended for scaling and adoption by stakeholders in fruit and vegetable supply chains, with further potential for application across a variety of perishable crops.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

-

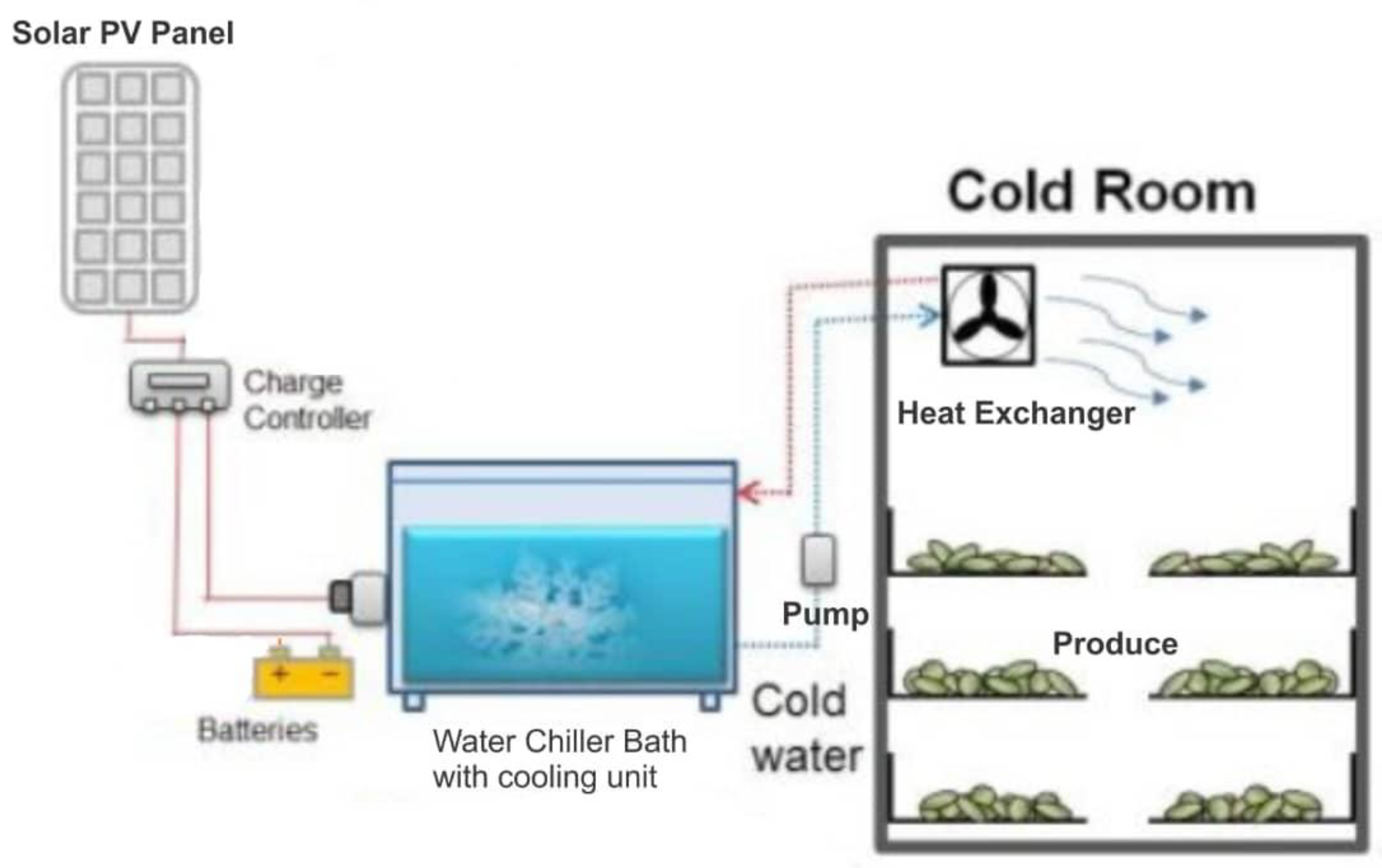

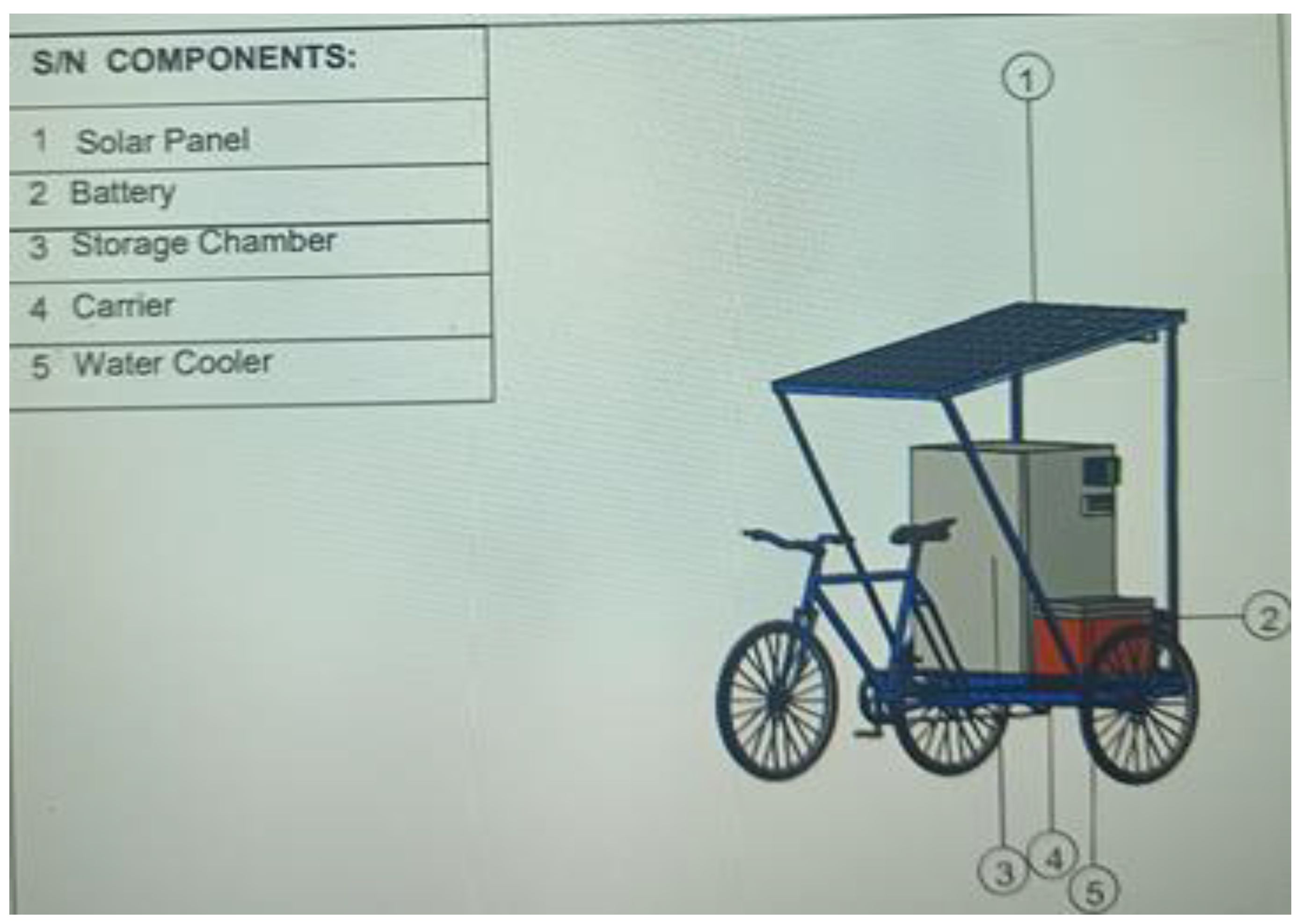

Construction Materials:Insulation materials: Various types of insulation materials were selected to minimize heat loss and maintain the internal temperature of the mobile solar cooling system (MSCS). The choice of insulation material was guided by its thermal resistance, durability, and cost-effectiveness.Frame and Enclosure: These were made from lightweight, corrosion-resistant materials such as aluminum and polycarbonate. The design aimed at achieving a balance between structural integrity and portability.Solar Panels: High-efficiency photovoltaic (PV) panels were selected to capture sunlight effectively and convert it into electrical power for cooling. The orientation and mounting of these panels were optimized to maximize solar energy absorption.

-

Evaluation Materials (Green Amaranth):Sample Selection: Fresh green amaranth was selected as the test material due to its sensitivity to temperature variations. This choice provided a representative case to study the effectiveness of the MSCS in preserving the freshness and shelf life of perishable vegetables.Preparation for Testing: The green amaranth was cleaned, sorted, and weighed before being placed inside the MSCS. The weight and condition of the amaranth were monitored at regular intervals to evaluate the cooling system’s performance.

-

Instruments/Equipment:Measuring Devices: A set of digital thermometers, hygrometers, and data loggers were used to monitor the internal temperature and humidity levels within the MSCS during operation. These instruments allowed for precise tracking of environmental conditions inside the system.Power Meters: Used to measure the energy consumption of the MSCS and the output from the solar panels. This data helped in assessing the system's energy efficiency and sustainability.Load Cells: To measure the weight of the vegetables, providing insights into moisture content and loss over time due to cooling.

2.1. Design Considerations

-

Capacity and Total Weight of the MSCS:The capacity was designed to hold up to 50 kg of fresh vegetables, balancing cooling efficiency with portability.The total weight was minimized to ensure easy mobility, especially important for users in remote areas.

-

Insulation Materials:The selection of insulation materials was critical to maintaining the internal temperature. The design aimed at optimizing the thermal resistance to prevent heat ingress from the external environment, thereby enhancing the cooling efficiency of the system.

-

Heat Load Calculations:Calculations were conducted to determine the thermal load based on the amount of heat generated by the solar panels and the ambient temperature conditions. These calculations guided the selection of cooling capacity and the design of the ventilation system to effectively manage the heat within the system.

-

Compactness and Availability of Construction Materials:The system was designed to be compact yet sturdy, making use of readily available construction materials to reduce costs and facilitate easy maintenance and repair. The goal was to create a practical solution that could be easily replicated in different settings.

2.2. Materials Needed for the Mobile Solar Cooling System (MSCS)

- i.

- Mobile devise: A tricycle

- ii.

- Solar components: solar panels, charge controller, deep cycle solar battery, circuit breakers, cable and cable connectors and switch board.

- iii.

- Cooling component materials: DC compressor accessories, condenser with fan, water bath with water as phase change material, evaporator plates on which ice was formed, a brushless DC water pump to convey chilled water to the storage chamber, water hoses, clips and refrigerant (R600a) isobutene which is environmental friendly.

- iv.

- Storage chamber component materials: polyurethane panels of 60mm insulation thickness for rectangular shape storage chamber construction, stainless pipe for construction of racks and shelves, stainless mesh was used for construction of trays where produce were arranged, heat exchanger (evaporator) with fan to circulate thermal cooling energy in the storage chamber.

- v.

- Other items for construction are galvanized metal sheets, bolts, nuts and screws to fasten the walls of storage chamber and other parts together, a 45 litres (from calculation) insulated plastic container was used for water chiller bath to avoid thermal losses, electrodes (both stainless and mild steel type will be used for welding the various metal parts.

2.3. Instrumentation Devises for the Research Work

- i.

- A digital camry weighing scale (30 kg) and (600 g) capacity of 0.001 kg accuracy, ACS – 30 – JE 11, made in china – was used for measuring the weights of samples.

- ii.

- Hobo Humidity/Temperature automated Data logger (ONSET MX2301, WXF – ONST3) - It monitors temperatures from -40 to +85°C. It has built-in temperature sensor, Case waterproof to ip68, User programmable alarms, User-replaceable battery, 32,000 reading capacity, High reading resolution, Fast data offload and Low-battery monitor.

- iii.

- Fruit and vegetable portable colourimeter (WR10QC – 8, 10QC230754) was used to monitor the test commodity’s colour change.

- iv.

- Solar power meter (NO. 11128388, LCD display, w/m2 or BTU) – this was used in measuring solar insolation of the sun in the study location.

- v.

- AC and DC multimetre (Etekcity-C600 digital clamp metre) – this was used to measure the current in solar panels, batteries, compressors and charge controller.

- vi.

- Four channel thermocouple: 3 (three) of this channel was used to record the temperature of water in the water chiller bath and the remaining 1 channel is to record ambient temperature.

- vii.

- Thermostat was used to control the temperature both in the storage chamber and in the water chiller bath.

- viii.

- Smart Sensor Digital Anemometer AR826 (Graigar, China) measuring to an accuracy of 0.3 m/s. This is to measure the air velocity in the storage chamber

2.4. Design Calculations

2.4.1. Calculation of Total Heat Loads

- (1)

- The total heat of conduction through the insulated walls of the storage chamber of the MSCS will be obtained using Equation (1) as reported by Ogumo et al. [6]

- (2)

- Calculation of field heat of produce in the storage chamber

- (3)

- Calculation of heat of respiration of produce in the storage chamber

- (4)

- Calculation of air infiltration load in the storage chamber

- (5)

- Calculation of miscellaneous heat load (Equipment load) in the storage chamber of the MSCS

2.4.2. Safety Factor for the Calculated Total Heat Loads

2.4.3. Determination of Refrigeration Cooling Capacity of the MSCS

| Source of Heat | Quantity of Heat (Kwh/day) |

| Heat of conduction | 0.68 |

| Produce heat (sensible) | 0.47 |

| Produce heat (respiration) | 0.00382 |

| Air infiltration heat | 0.002 |

| Miscellaneous (equipment) heat | 0.16 |

| Total heat load Safety factor (20%) of total heat load Total heat load + safety factor calculated |

1.32 0.26 1.58 |

2.5. Fabrication Process and Description of the MSCS

2.6. No-Load Test Evaluation of the MSCS

2.6.1. Ice Production Capacity of the MSCS

| S/NO | Date | Time | Quantity 0f water (Mt)(L) | Weight of water (Mw)(kg) | (kg) | Cummulative weight of ice (kg) | Temperature of water (0C) | Mean Current in the compressor(I) | Mean Voltage in the compressor (V) | Mean ambient temp. (0C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25/3/24 | 5 pm | 36 | 32.21 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 4.30 | 11.40 | 28.4 |

| 2 | 26/3/24 | 5 pm | 22 | 19.6 | 12.61 | 12.61 | -2 | 4.28 | 11.50 | 29.7 |

| 3 | 27/3/24 | 5 pm | 11 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 23.01 | -2.8 | 4.03 | 12.37 | 30.0 |

| 4 | 28/3/24 | 5 pm | 4 | 3.6 | 5.6 | 28.61 | -3.8 | 3.89 | 12.32 | 31.3 |

| 5 | 29/3/24 | 5 pm | 2 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 30.61 | -1.2 | 4.01 | 12.54 | 31.9 |

| Mean | 7.7 | 4.1 | 12.01 | 30.26 |

2.6.2. Determination of Quantity of Energy Available in the Ice (Energy Output)

2.6.3. Determination of Energy Consumption by the Compressor (Energy Input)

2.6.4. Determination of Heat Loss from Insulated Surfaces (Q Losses)

2.6.5. Determination of Coefficient of Performance (COP) of the System

2.7. Load Test (Evaluation with Green Amaranth)

2.8. Experimental Design for the Research Work

3. Results

| Treatment | Moisture | Crude fibre % | Crude Protein % | Vit A | Iron mg/100g | Beta Carotene mg/100 g | Weight loss kg | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | 90.35 | 2.07 | 3.04 | 1.57 | 53.14 | 24.01 | 5 | leaves were green and very attractive |

| Ambient at day 3 | 85.09 | 1.91 | 2.99 | 0.99 | 48.88 | 19.21 | 4.4 | leaves withering |

| MSCS at day 3 | 89.01 | 2.03 | 3.23 | 1.21 | 52.61 | 23.52 | 4.8 | Still fresh |

| Ambient at day 5 | 67.91 | 1.56 | 2.04 | 0.89 | 41.39 | 15.36 | 2.7 | leaves fallen, experiment ended. |

| MSCS at day 5 | 88.98 | 2.1 | 3.12 | 1.11 | 52.08 | 22.76 | 4.44 | still fresh |

| MSCS at day 12 | 87.25 | 2.04 | 3.11 | 1.02 | 51.35 | 22.49 | 4.06 | leaves wither and colour change |

3.1. Effect of Temperature and Relative Humidity on Storage Quality

3.2. Physicochemical Changes in Storage

- Weight Loss: Weight loss in ambient storage was 45% higher than in the MSCS, primarily due to moisture loss induced by high temperatures and low relative humidity [15].

- Nutrient Retention: Crude fiber, crude protein, vitamin A, and beta-carotene content decreased in both storage conditions, but the decline was more pronounced in ambient storage. For example, beta-carotene content at day 5 was 15.36 mg/100 g in ambient storage compared to 22.76 mg/100 g in the MSCS.

- Microbial Growth: The bacterial and fungal loads in the MSCS remained within acceptable limits (< 105 CFU/g for bacteria and 103−104 CFU/g for fungi) as stipulated by the International Commission for Microbiological Specifications. In contrast, microbial loads in the ambient storage exceeded these limits by day 5, making the produce unsafe for consumption [30].

3.3. Performance of the MSCS

3.4. Comparison to Ambient Storage

4. Conclusions

References

- Adekalu, O.A.; Akande, S.A.; Fashanu, T.A.; Adeiza, A.O.; Lawal, I.O. Evaluation of improved vegetable baskets for storage of Amaranthus viridis (green amanranths) and Telfaria occidentalis H. (fluted pumpkin leaves). Res. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 7, 111–119. [CrossRef]

- Rahiel, H.A.; Zenebe, A.K.; Leake, G.W.; Gebremedhin, B.W. Assessment of production potential and post-harvest losses of fruits and vegetables in northern region of Ethiopia. Agric. Food Secur. 2018, 7, 29. [CrossRef]

- UN. The World at Seven Billion. A Rep from United nations Gen Assem regarding Popul Dyn Futur. :10 pages.

- Sipho, S. Development of a solar powered indirect air cooling combined with direct evaporative cooling system for storage of fruits and vegetables in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Agric Res Counc South Africa. 2019;9(10):1051–61. Available from: 10.13140/RG.2.2.13604.60808.

- Jekayinfa, S.O. and Scholz, V. Assessment of availability and cost of energetically usable crop residues in Nigeria. Nat gas. 2007;24(8):25–8.

- Ogumo, E.O.; Kunyanga, C.N.; Kimenju, J.; Okoth, M. Performance of a fabricated solar-powered vapour compression cooler in maintaining post-harvest quality of French beans in Kenya. Afr. J. Food Sci. 2020, 14, 192–200. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Gender and food loss in sustainable food value chains [Internet]. FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS (FAO) Rome, 2018. 2018. v–41.

- Tushar, S. Design and development of a solar powered cold storage system. Doctoral Dissertation, Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati, India; 2018.

- Verploegen, E., Ekka, R., and Gurbinder, G. Evaporative Cooling for Improved Vegetable and Fruit Storage in Rwanda and Burkina Faso. 2019.

- Olorunnisola, A.O. and Okanlawon, S.A. Development of passive evaporative cooling systems for tomatoes Part 1: construction material characterization. Agric Eng Int CIGR J. 2017;19(1):178–86.

- Aremu, I.S., Asafa, T.B., Jekayinfa, S.O., Lateef, A., and Ola, F.A. Development of Silica Nanoparticles as a Biopesticide for Enhanced Postharvest Lifespan of Cowpea. Adeleke Univ J Eng Technol. 2023;6(2):350–6.

- Stathers, T. Quantifying postharvest losses in Sub-Saharan Africa with a focus on cereals and pulses. Bellagio Work Postharvest Manag. 2017;15.

- Ogunlade, C.A.; Jekayinfa, S.O.; Oyedele, O.J.; Olajire, A.S.; Oladipo, A.O. Drying parameters of wild lettuce (Lactuca taraxaxifolia L) affected by different drying methods. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 15, 115–122. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S., Saghir, S.A., and Shahzor, K.G. Effect of storage on the physicochemical characteristics of the mango (Mangifera indica L.) variety, Langra. African J Biotechnol. 2012;11(41):9825–8.

- Ajayi, O.O.; Useh, O.O.; Banjo, S.O.; Oweoye, F.T.; Attabo, A.; Ogbonnaya, M.; Okokpujie, I.P.; Salawu, E.Y. Investigation of the heat transfer effect of Ni/R134a nanorefrigerant in a mobile hybrid powered vapour compression refrigerator. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 391, 012001. [CrossRef]

- Jekayinfa, S.O.; Adeleke, K.M.; Ogunlade, C.A.; Sasanya, B.; Azeez, N. Energy and exergy analysis of Soybean production and processing system. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Akorede, M.; Ibrahim, O.; Amuda, S.; Otuoze, A.; Olufeagba, B. CURRENT STATUS AND OUTLOOK OF RENEWABLE ENERGY DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA. Niger. J. Technol. 2016, 36, 196–212. [CrossRef]

- Sitorus, T.B.; Ambarita, H.; Ariani, F.; Sitepu, T. Performance of the natural cooler to keep the freshness of vegetables and fruits in Medan City. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 309, 012089. [CrossRef]

- Osadare, T., Koyenikan, O.O., and Akinola, F.F. Physical and mechanical properties of mango during growth and storage for determination of maturity. Asian Food Sci Joural. 2019;10(2):1–8.

- Jekayinfa, S.; Linke, B.; Pecenka, R. Biogas production from selected crop residues in Nigeria and estimation of its electricity value. Int. J. Renew. Energy Technol. 2015, 6, 101. [CrossRef]

- Kazem, H.A.; Al-Waeli, A.H.A.; Chaichan, M.T.; Al-Mamari, A.S.; Al-Kabi, A.H. Design, measurement and evaluation of photovoltaic pumping system for rural areas in Oman. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 19, 1041–1053. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Dubey, R. Factors Affecting Post-Harvest Life of Flower Crops. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 548–557. [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.S. ASHRAE Handbook--Refrigeration. Am Soc Heating, Refrig Air-Conditioning Eng Atlanta. 2018;

- Babaremu, K.O., Omodara, M.A., Fayomi, S.I., Okokpujie, I.P., and Oluwafemi, J.O. Design and optimization of an active evaporative cooling system. Int J Mech Eng Technol. 2018;9(10):1051–61.

- Chaudhary, S. and Sharma, V. Thermal system design of a cold storage for 1500 metric tonne Potatoes. Int J Eng Res Technol. 2015;4(7):933–43.

- Olubanjo, O. Climate Variation Assessment Based on Rainfall and Temperature in Ilorin Kwara State Nigeria. Appl. Res. J. Environ. Eng. 2019, 2, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Olosunde, W.A., Aremu, A.K., and Umani, K.C. Performance optimization of a solar-powered evaporative cooling system. J Agric Eng Technol. 2019;24(2):21–34.

- Bradbury, A., Hine, J., Njenga, P., Otto, A., Muhia, G., and Willilo, S. Evaluation of the Effect of Road Condition on the Quality of Agricultural Produce. Africa Community Access Partnersh (AsCAP) Safe Sustain Transp Rural communities. 2017;

- Yousuf, B.; Qadri, O.S.; Srivastava, A.K. Recent developments in shelf-life extension of fresh-cut fruits and vegetables by application of different edible coatings: A review. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 89, 198–209. [CrossRef]

- Ayanda, I.S., Ibrahim, A.S., Adebayo, O.B., Afolayan, S.S., Akande, S.A., and Lawal, I.O. Effect of Storage Medium o the Sensory Attributes, Physicochemical Properties and Nutritional Compositions of Ripe Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Nijerian Journnal Post-Harvest Res. 2019;2(2):34–44.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).