Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Large software applications typically use open source software (OSS) to implement key pieces of functionality. Often only the functionality is considered, and the non-functional requirements, such as security, are ignored or not fully taken into account prior to the release of the software application. This leads to issues in two different areas: 1) evaluating the OSS used in our current software, 2) evaluating OSS that our developers may be considering using. This research focuses on providing a mechanism to examine third-party components, focusing on security vulnerabilities. Both current and future software face similar security issues. We develop an approach to minimize risk when adding in OSS to an application, and we provide an assessment of how exploitable 8 new/existing software applications may be if not secured with other layers of defense. We have analyzed two case studies of known compromised open source components [1]. The developed controls identified high levels of risk immediately.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- *

- Description of a technique to examine used/potential components for vulnerabilities.

- *

- Leveraging of the Open Source Security Foundation (OSSF) scorecard health metrics.

- *

- Analyzing the component dependencies and the software bill of materials (SBOM) to determine a dependency tree of components used.

- *

- Development of a continuous verification system to enable organizations to make data-driven decisions based on component analysis.

- *

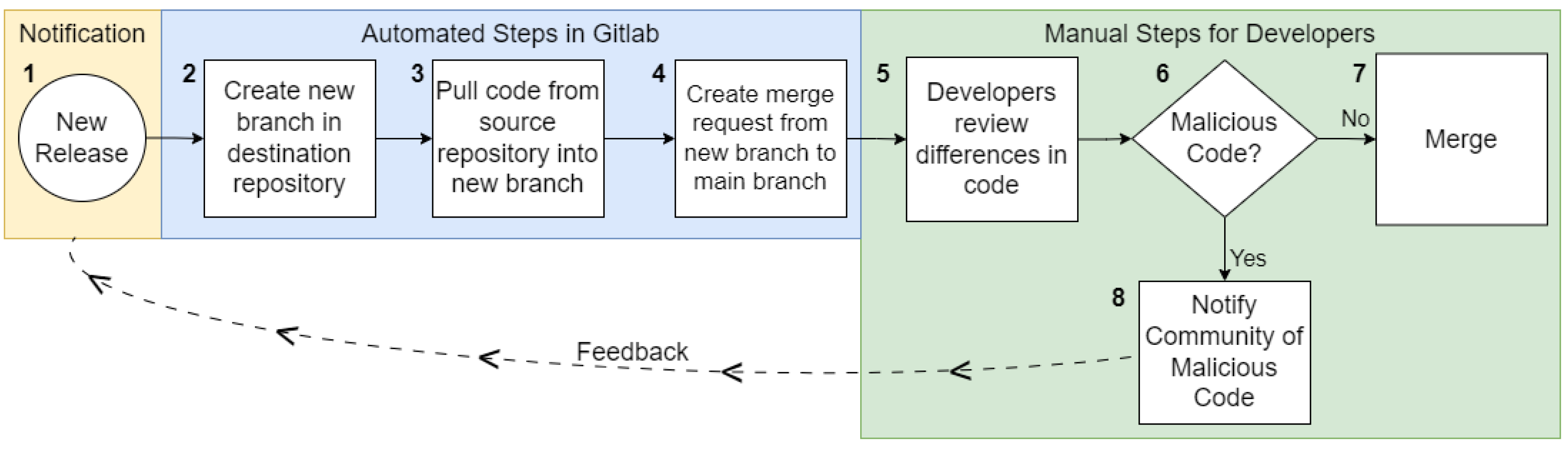

- Automated systems architecture for reviewing and sanitizing OSS components before and after use.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dealing with Vulnerabilities in the Supply Chain

2.1.1. Potential and Current Vulnerabilities

2.1.2. Code Analysis for OSS Dependencies

2.1.3. Continuous Integration System

2.1.4. Incorporating Operations

3. Results

3.1. Vulnerability Assessments

3.2. Continuous Verification in Operations

- C1: Improving the checks on the package for known vulnerabilities in a package’s dependencies and in the package itself, analyzing the history of vulnerabilities and the weaknesses causing the vulnerability.

- C2: Leveraging available static code analysis tools to review and analysis the source code for known weaknesses, with emphasis on known CWE information.

- C3: Deeper dive into the package’s community to understand the security posture of the community’s maintainers and contributors.

- C4: Code and ecosystem complexity for the OSS component.

- C5: Architecture and threat modeling of the package has been completed.

- C6: Security documentation to make software practitioners more aware of security configurations and concerns when including the OSS component as a dependency.

- C7: Confirm there is an authorized and available Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) available for the OSS component.

- C8: Completing dynamic scanning of the overall application that is using the OSS component as a dependency.

- C9: Assessing the application before it is deployed into production with an application level penetration test.

- C10: Improving the hardening of the network perimeter defense around the development and production environment of the software project.

3.2.1. Evaluation

- The larger size of its source code base and usage of JavaScript.

- The high number of dependencies it has, as well as the large number of repositories and packages that are dependent upon it.

- The overall security posture is lacking, due to no official software bill of materials, lack of security related documentation, and no evidence of threat modeling completed.

- Repetitive vulnerabilities that have been High or Critical severity.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hastings, T.G. Combating Source Poisoning and Next-Generation Software Supply Chain Attacks Using Education, Tools, and Techniques. Ph.D., University of Colorado Colorado Springs, United States – Colorado, 2024. ISBN: 9798382262970.

- Townsend, K. Cyber Insights 2023 | Supply Chain Security. url = https://www.securityweek.com/cyber-insights-2023-supply-chain-security/, 2023.

- Fitri, A. Supply chain attacks on open source software grew 650% in 2021. url = https://techmonitor.ai/technology/cybersecurity/supply-chain-attacks-open-source-software-grew-650-percent-2021, 2021.

- Plumb, T. GitHub’s Octoverse report finds 97% of apps use open source software. url = https://venturebeat.com/programming-development/github-releases-open-source-report-octoverse-2022-says-97-of-apps-use-oss/, 2022.

- Microsoft. Github advisory database. url = https://github.com/advisories, 2023.

- Blog. Enable Dependabot, dependency graph, and other security features across your organization. url = https://github.blog/changelog/2020-07-13-enable-dependabot-dependency-graph-and-other-security-features-across-your-organization/, 2020.

- Snyk. Enable Dependabot, dependency graph, and other security features across your organization. url = https://docs.dependencytrack.org/datasources/snyk/, 2023.

- Pashchenko, I.; Vu, D.L.; Massacci, F. A Qualitative Study of Dependency Management and Its Security Implications. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, New York, NY, USA, 2020; CCS ’20, pp. 1513–1531. [CrossRef]

- Vailshery, L. Year-over-year (YoY) increase in open source software (OSS) supply chain attacks worldwide from 2020 to 2022. url = https://www.statista.com/statistics/1268934/worldwide-open-source-supply-chain-attacks/, 2023.

- Zahan, N.; Zimmermann, T.; Godefroid, P.; Murphy, B.; Maddila, C.; Williams, L. What are Weak Links in the npm Supply Chain? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice, 2022, pp. 331–340. arXiv:2112.10165 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- lmays. Security Scorecards for Open Source Projects, 2020.

- Malicious code found in npm package event-stream downloaded 8 million times in the past 2.5 months, 2018.

- Mitre. CNAs | CVE, 2023.

- Mitre. Overview | CVE, 2023.

- Mitre. CWE - About - CWE Overview, 2023.

- Swinhoe, D. 7 places to find threat intel beyond vulnerability databases. url = https://www.csoonline.com/ article/3315619/7-places-to-find-threat-intel-beyond-vulnerability-databases.html, 2018.

- Urbanski, W. Day 0/Day 1/Day 2 operations & meaning - software lifecycle in the cloud age, 2021.

- vipul1501. Dependency Graph in Compiler Design, 2022. Section: Compiler Design.

- Vaszary, M. The EO and SBOMs: What your security team can do to prepare, 2023.

- NIST. attack surface - Glossary | CSRC, 2023.

- Hastings, T.; Walcott, K.R. Continuous Verification of Open Source Components in a World of Weak Links. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering Workshops (ISSREW), 2022, pp. 201–207. [CrossRef]

- npm. vendorize, 2019.

- Hastings, T.; Walcott, K.R. Continuous Verification of Open Source Components in a World of Weak Links. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering Workshops (ISSREW). IEEE, 2022, pp. 201–207.

- Wang, X.; Sun, K.; Batcheller, A.; Jajodia, S. Detecting "0-Day" Vulnerability: An Empirical Study of Secret Security Patch in OSS. In Proceedings of the 2019 49th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN); 2019; pp. 485–0889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris Khan, F.; Javed, Y.; Alenezi, M. Security assessment of four open source software systems. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 2019, 16, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkortzis, A.; Feitosa, D.; Spinellis, D. Software reuse cuts both ways: An empirical analysis of its relationship with security vulnerabilities. Journal of Systems and Software 2021, 172, 110653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponta, S.E.; Plate, H.; Sabetta, A. Detection, assessment and mitigation of vulnerabilities in open source dependencies. Empirical Software Engineering 2020, 25, 3175–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashchenko, I.; Plate, H.; Ponta, S.E.; Sabetta, A.; Massacci, F. Vuln4Real: A Methodology for Counting Actually Vulnerable Dependencies. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 2022, 48, 1592–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prana, G.A.A.; Sharma, A.; Shar, L.K.; Foo, D.; Santosa, A.E.; Sharma, A.; Lo, D. Out of sight, out of mind? How vulnerable dependencies affect open-source projects. Empirical Software Engineering 2021, 26, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Operations | OSSF Framework | Our Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Shift Left 0 | Low Risk | High Risk |

| Shift Left 1 | Not in Scope | Effective |

| Shift Left 2 | Not in Scope | Effective |

| Operations | OSSF Framework | Our Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Shift Left 0 | High Risk | High Risk |

| Shift Left 1 | Not in Scope | Effective |

| Shift Left 2 | Not in Scope | Effective |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).