1. Introduction

1.1. Fast Solidification in Nature and in the Technical World

Between 8 and 10 % of the flowering plants in nature exude a latex when injured [

1,

2]. The term “latex” in this context denotes a milky fluid, which solidifies after exudation, thereby protecting the plant [

2,

3,

4]. Protection encompasses “self-sealing” and “self-healing”,[

3] where self-sealing precedes self-healing. Even a liquid material may prevent the entry of toxins into the plant (self-sealing), while self-healing requires some degree of solidification. Evidently, fast self-healing amounts to an evolutionary advantage.

We briefly digress on the solidification of technical latices, also termed polymer dispersions. Polymer dispersions amounted to a market volume of more than 10 billion US dollars in 2023.[

5] Important products are coatings,[

6] adhesives,[

7] and rubber gloves.[

8] Film formation from water-borne polymer dispersions has been studied in considerable depth.[

9] The mechanisms of solidification can be roughly grouped as physical drying,[

10] chemical crosslinking,[

11] polymer interdiffusion,[

12] and wet sintering.[

8] Physical drying in air can induce deformation and merging of particles with a glass temperature close to the drying temperature because the deformation in this case is driven by a large negative capillary pressure originating from the concave menisci at the film–air interface.[

10] Chemical crosslinking is widely employed to achieve toughness [

11,

13] The diffusion of polymer chains across the interparticle boundaries – often at elevated temperature and over prolonged time – also contributes to toughness.[

14] Wet sintering is employed in a process called coagulation dipping.[

15] The object to be covered (the “former”, shaped as a hand in the production of rubber gloves) is first coated with a coagulant (a layer of a calcium salt) and then dipped into the latex dispersion. After the electrostatic repulsion between spheres has been overcome by Ca

2+-bridges, particles coalesce onto the former, driven by the van-der-Waals attraction and the interfacial tension between the polymer and the liquid. Coagulation dipping requires soft materials such as rubbers because the stress in wet sintering does not suffice to deform stiff spheres.

Both physical drying and drying-induced crosslinking take tens of seconds, at least, because they require diffusive transport of water or reaction inhibitors from the bulk to the film-air interface. If crosslinking is induced by oxygen, the oxygen again must diffuse from the film-air interface into the bulk. At room temperature and with a film thickness above 300 µm, the drying time is closer to a few minutes than to a few seconds. This estimate follows from the diffusion time scale, τ

diff, being given as τ

diff =

L2/

D with

L the characteristic length (

L > 300 µm) and

D the diffusivity (

D < 10

−5 cm

2/s). Drying time is of critical importance when laminating aluminum foils while these run through an oven at high speed. This process has received renewed attention in the context of electrode formation for lithium ion batteries.[

16] These consist of special coatings on an aluminum backing, where the latter is the current collector. Drying time translates into path length inside the oven and thereby into cost. The rate limiting step can be diffusion inside the film, but also the rate of evaporation.[

17]

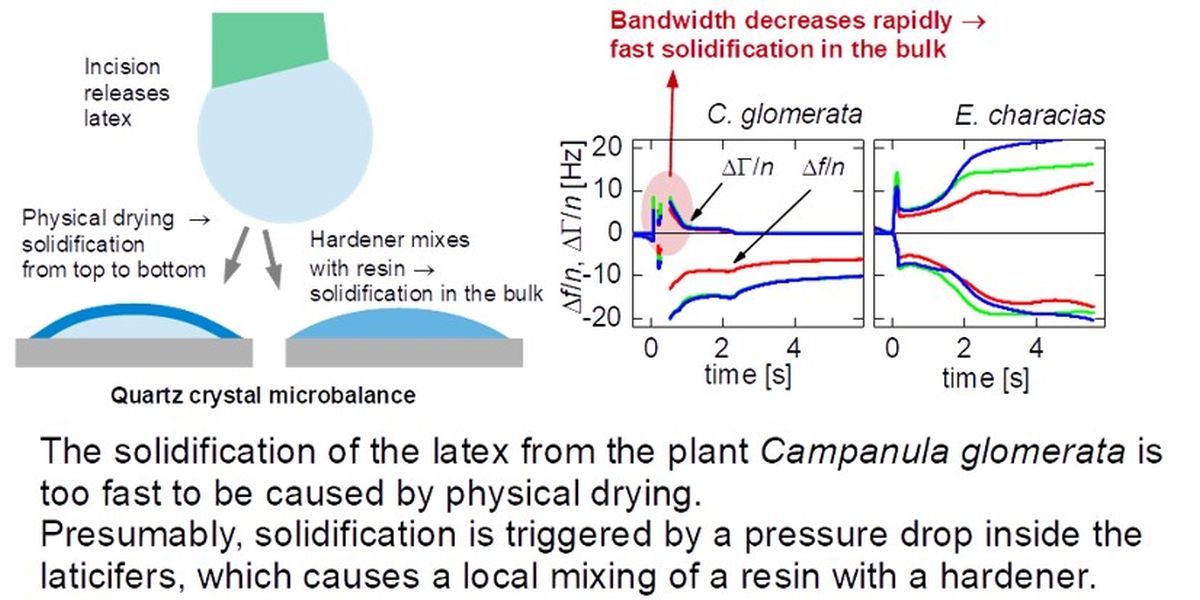

This work is concerned with a solidification process – namely the self-healing of the latex exuded by

Campanula glomerata – which is too fast to be caused by physical drying. As well-known from the technical world, solidification can also be triggered by mixing processes on the local scale. These require a mechanism, by which the reagents (often called “resin” and “hardener”) are maintained separate prior to solidification and are mixed once solidification is supposed to set in. Microcompartments achieving separation may be capsules with a wall, which breaks when a suitable stimulus is applied. In the case of the “self-healing resins”, the stimulus is a crack which intersects the capsule containing the hardener.[

18] Other stimuli can be temperature, biodegradation,[

19] or stress.[

20] Physical drying may also be the stimulus, but physical drying is slow. A second example, where a hardener is released from a capsule, is the rubber tree (

Hevea brasiliensis). The hardener in

H. brasiliensis is the protein hevein, contained in capsules named “lutoids”.[

21] Pakianathan et al. noticed as early as 1966 that lutoids may break following an osmotic shock.[

22] D’Auzac et al. propose that the osmotic shock is the consequence of an influx of serum into the capillaries containing the lutoids (the “laticifers”).[

23] This influx is the consequence of a sudden decrease of pressure inside the capillaries, as expected upon exudation. D’Auzac et al. do not emphasize that the process can be fast and it actually is not particularly fast in the case of the rubber tree. It can be fast though, because a pressure drop propagates through the sample with the speed of sound and because the follow-up processes all happen on a local scale. The d’Auzac model is compatible with fast solidification.

1.2. A Possible Role of Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) in Solidification

The problem with the d’Auzac model applied to

C. glomerata is that images of the exudate acquired with cryo-SEM did not show any evidence of capsules.[

24] The d’Auzac model requires capsules and it is difficult to understand why such capsules should not at all be visible in cryo-SEM images.

Another conceivable mixing process on the local scale is linked to a transition from liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) to a single-phase state, triggered by pressure.[

25] LLPS is rather common in biological systems, often in the form of condensed globules of proteins. LLPS can also amount to complex formation between two sets of polyelectrolytes with opposite charge. The name “coacervation” is often used in the context of polyelectrolytes, but is also applied to biocondensates. LLPS and its biological implications have in depth been reviewed in Cinar et al.[

25]. Liu et al. describe the role of LLPS in fibrillar networks.[

26] Rose et al. report an experiment, where coacervation was used to turn a fluid latex dispersion into a gel.[

27]

Among the parameters modulating LLPS are protein concentration, ionic strength, osmolyte content, and pressure. Pressure affects the intermolecular interactions and may thereby induce a transition from a two-phase state to single-phase state, at least in principle. A more detailed look at the examples from [

25], however, raises doubt on pressure being the direct cause of such a transition in

C. glomerata. The pressures involved are in the range of hundreds of bars (see Figure 6 in 27), while the pressure inside the laticifers is closer to a few bars. More likely, the transition is mediated by an influx of serum into the laticifers, where the latter is caused by the pressure drop. The serum changes the concentrations of ions and osmolytes inside the laticifers. A similar, indirect path is claimed in the case of the rubber tree. The osmotic shock in the d’Auzac model is caused by an influx of serum, as opposed to altered hydrostatic pressure.

1.3. Previous Work on C. glomerata

Fast solidification in the case of

C. glomerata and the pressure-drop mechanism playing a role in the latex of solidification from

Ficus benjamina have been discussed in different publications by the Freiburg group.[

28] Bauer et al. describe a setup, which allowed to damage plants under pressure.[

1] Latex solidification was much delayed in

Hevea brasiliensis and

Ficus benjamina when the plant was injured at a pressure above 8 bars. Because coagulation in the case of

C. glomerata was too fast for these experiments, the Freiburg group conducted a second simple test.[

28] They cut the stem of

C. glomerata and repeatedly pulled on the white fluid with the same scalpel, which was used to make the cut. Immediately after the cut (~ 1 s) the latex was in a liquid state. The second or third pull (2 – 5 seconds later) produced threads between the stem and the tip of the scalpel. At this time, an elastic skin had formed.

The Freiburg group undertook a third experiment,[

29] which motivates the work reported below. Solidification of

F. benjamina and

E. characias latex was monitored using nanorheometers in an initial oscillating mode followed by a stepped-shear viscosity test. Parallel measurements of the drying rate based on gravimetry allowed to distinguish between evaporation effects in

Euphorbia spp. and chemical reactions as found in

F. benjamina. As with the high-pressure measurements, solidification in the case of

Campanula spp. was too fast to be followed with this setup. We expand on these studies using a fast rheometer, which gives access to the drying of

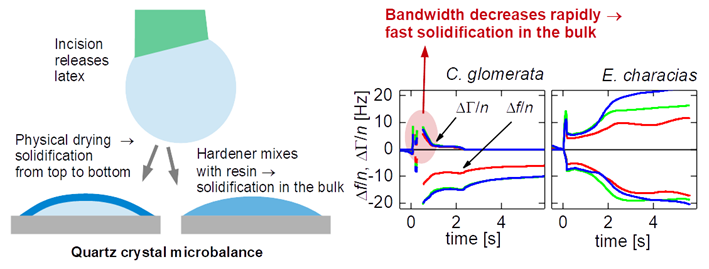

C. glomerata. More specifically, we employ a quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring (QCM-D, QCM, for short), described in section 2 in more detail. The high data acquisition rate allows to resolve the solidification kinetics. We further corroborate the explanation in terms of a pressure change with optical videos from plants being cut under water. These test for whether solidification requires the presence of air.

2. Experimental Procedures

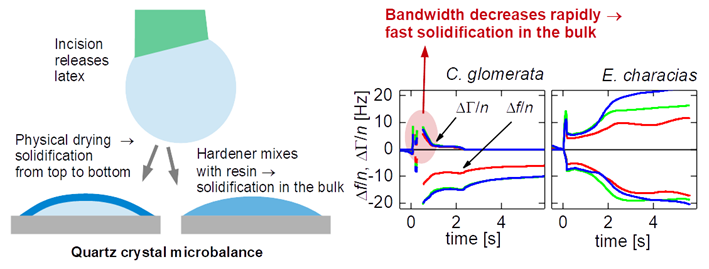

2.1. The QCM as an Instrument to Study Solidification

A QCM consists of a piezoelectric plate, which is electrically excited to thickness-shear vibrations with frequencies in the MHz range. A contact between the resonator and a sample shifts the resonance frequencies and the resonance bandwidths. When the sample is a liquid droplet, the kinetics of drying and/or solidification can be inferred from the evolution of frequency and bandwidth with time. Because the shear wave emanates from the resonator surface, the QCM is rather insensitive to the formation of a skin at the droplet–air interface. It mostly probes the bulk (

Figure 2.1C). A few microliters of sample suffice (even less, see Ref. [

30]), which is among the advantages of the QCM-D, compared to other rheometers. Also, droplets can be deposited onto the resonator plate, quickly. Cutting the stem of the plant and collecting the liquid takes more time than placing the sample onto the resonator plate. Other types of microrheometers do not allow for fast sample entry in the same way.[

31]

The Clausthal group has recently demonstrated a QCM-D with a much improved rate of data acquisition (section 2.2). In all respects other than time resolution, which is 10 milliseconds, the work reported below follows the lines of Bauer et al..[

29] Data acquisition is started, a droplet of latex is deposited on the resonator surface, and the droplet is allowed to solidify (

Figure 2.1). It takes some practice to cut the stems open and to then quickly place the droplet on the resonator surface (with a delay of about 10 s). Otherwise, the procedures are rather simple.

2.2. A Fast Quartz Crystal Microbalance Interrogated by a Multifrequency Lockin Amplifier

On the technical side, we exploit the options opened up by a fast, multi-overtone QCM-D, which makes use of a multifrequency lockin amplifier (MLA, supplied by Intermodulation Products SE, Stockholm, Sweden).[

32] The instrument determines shifts in frequency, Δ

f, and in half bandwidth, ΔΓ, on up to four overtones simultaneously, where overtones usually are labeled by their overtone order

n. Overtones at

n = 3, 5, and 7 with frequencies of 15, 25, and 35 MHz were interrogated here. In the “comb mode”, the MLA sends out up to 32 sine waves, arranged as one or a few combs in frequency, covering one resonance or the three resonances at 15, 25, and 35 MHz. The MLA collects the corresponding currents at these 32 frequencies, thereby determining the electrical admittance of the device under test at these frequencies. Plots of the complex admittance versus frequency show resonance curves, which can be fitted with “phase-shifted Lorentzians”.[

33] The fit derives the resonance frequency and the resonance bandwidth.

Transformed to the time domain, a frequency comb amounts to a series of pulses spaced in time by δtcomb = 1/δfcomb with δfcomb being the gap between neighboring frequencies. The gap therefore sets the time resolution of the measurement. δfcomb must be less than the bandwidth of the resonance because the comb will otherwise miss the resonance. With a resonance bandwidth of a few hundred Hz, δfcomb can be 100 Hz, which puts the time resolution to 10 ms.

For planar films, one might compare the values of Δ

f/

n between overtones, which would lead to a statement on the film’s softness. For droplets, the poorly controlled geometry prevents such a quantitative analysis.[

30,

34] Solidification per se, however, is easily inferred from the kinetics of the bandwidth. The bandwidth is proportional to the energy dissipated per unit time in the sample. Soft samples dissipate energy, while rigid samples do so to a lesser extent. There is a slight caveat insofar, as coupled resonances can complicate the picture.[

35] These occur, when the sample itself has an acoustic eigenfrequency close to the resonance frequency of the QCM. Droplets should be as small as possible for that reason. The droplets never where thinner than a few 100 µm, though. At this size, physical drying requires a few minutes, at least.

3. Results

3.1. QCM Experiments

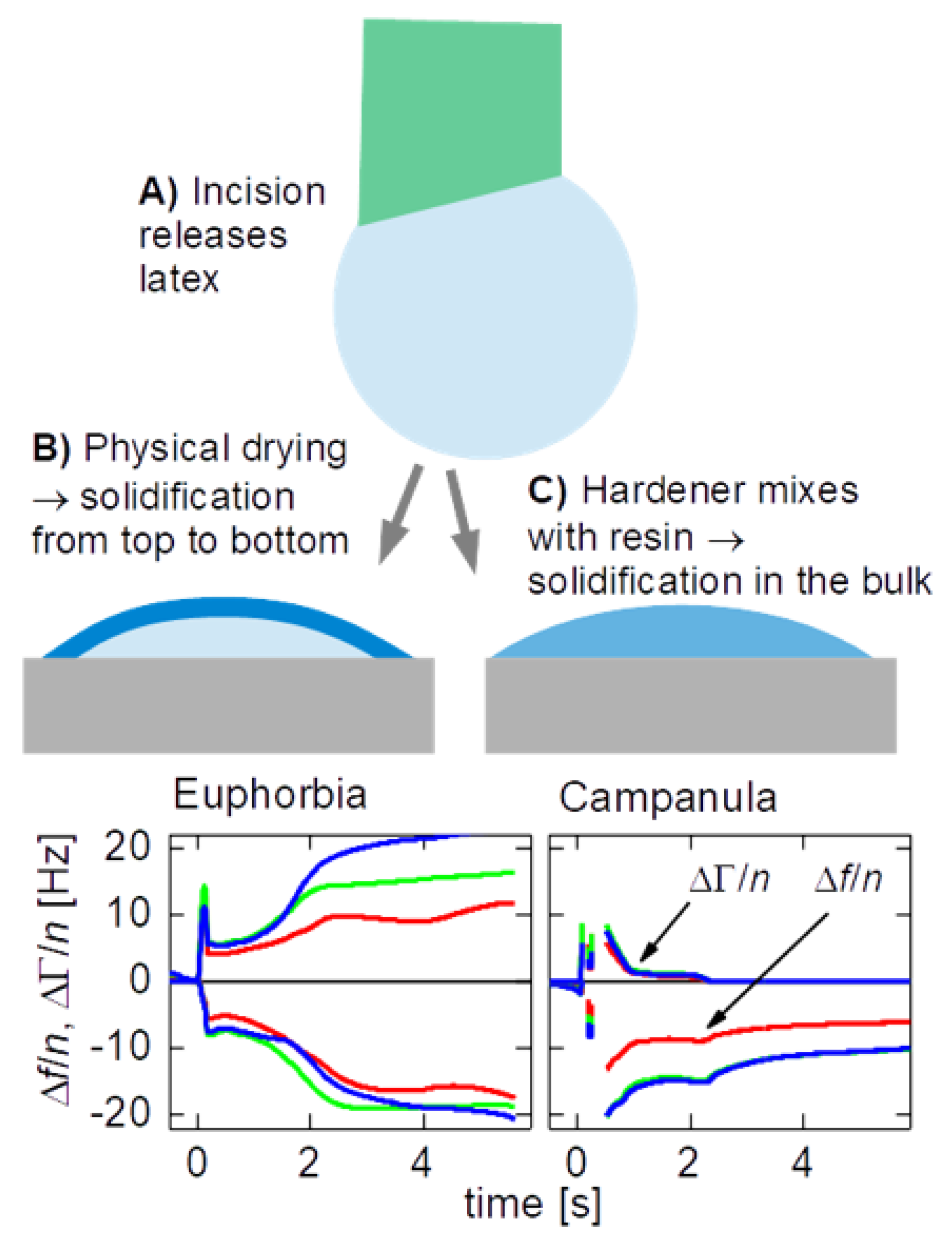

All plants were purchased in a local store. We report experiments on two species, which are C. glomerata (a flower, English names are “clustered bellflower” or “dane’s blood”) and E. characias silver swan (English name: “Mediterranean or Albanian spurge”). Numerous experiments were carried out on other plants (including Ficus benjamina and Dieffenbachia sp.) and, also, on technical latices, searching for characteristic differences in behavior. While there was some variability, systematic trends or differences between plant latices and technical latices were not seen. C. glomerata was the one exception. It solidified much faster than all other samples studied.

Figure 3.1 shows three examples (for each

E. characias and

C. glomerata) of how the shifts in overtone-normalized frequency, Δ

f/

n, and overtone-normalized half bandwidth, ΔΓ/

n, evolve with time. Data from three overtones at 15, 25, and 35 MHz are shown. The overtone-normalized frequency shifts never agreed between overtones. A rigid layer would induce an overtone-normalized frequency shift Δ

f/

n independent of overtone order. The samples studied here do not appear as rigid to the QCM. In panels D and E (

C. glomerata), ΔΓ/

n rapidly decreases to zero. These droplets do not dissipate energy after about a second. Remember that it took about 10 seconds to cut the stem and place the droplet on the resonator. Energy dissipation stopped at a time of less than 12 seconds after the cut was made.

In panel F (also

C. glomerata), there is a fast decrease, which, however, does not lead to zero. Judging from the frequency shift (and also from visual observation), this droplet is larger than the droplets from panels D and E. In the presence of a small viscous component of the sample’s compliance, ΔΓ scales as the cube of the sample’s thickness (Eq. 44 in Ref. [

33]). Because this droplet is thicker than the two others, ΔΓ/

n levels off to a finite value after solidification.

The phenomenology is much different in panels A – C (E. characias). In these cases, ΔΓ/n stays large over the duration of these experiments. ΔΓ/n does eventually drop after about a minute (data not shown).

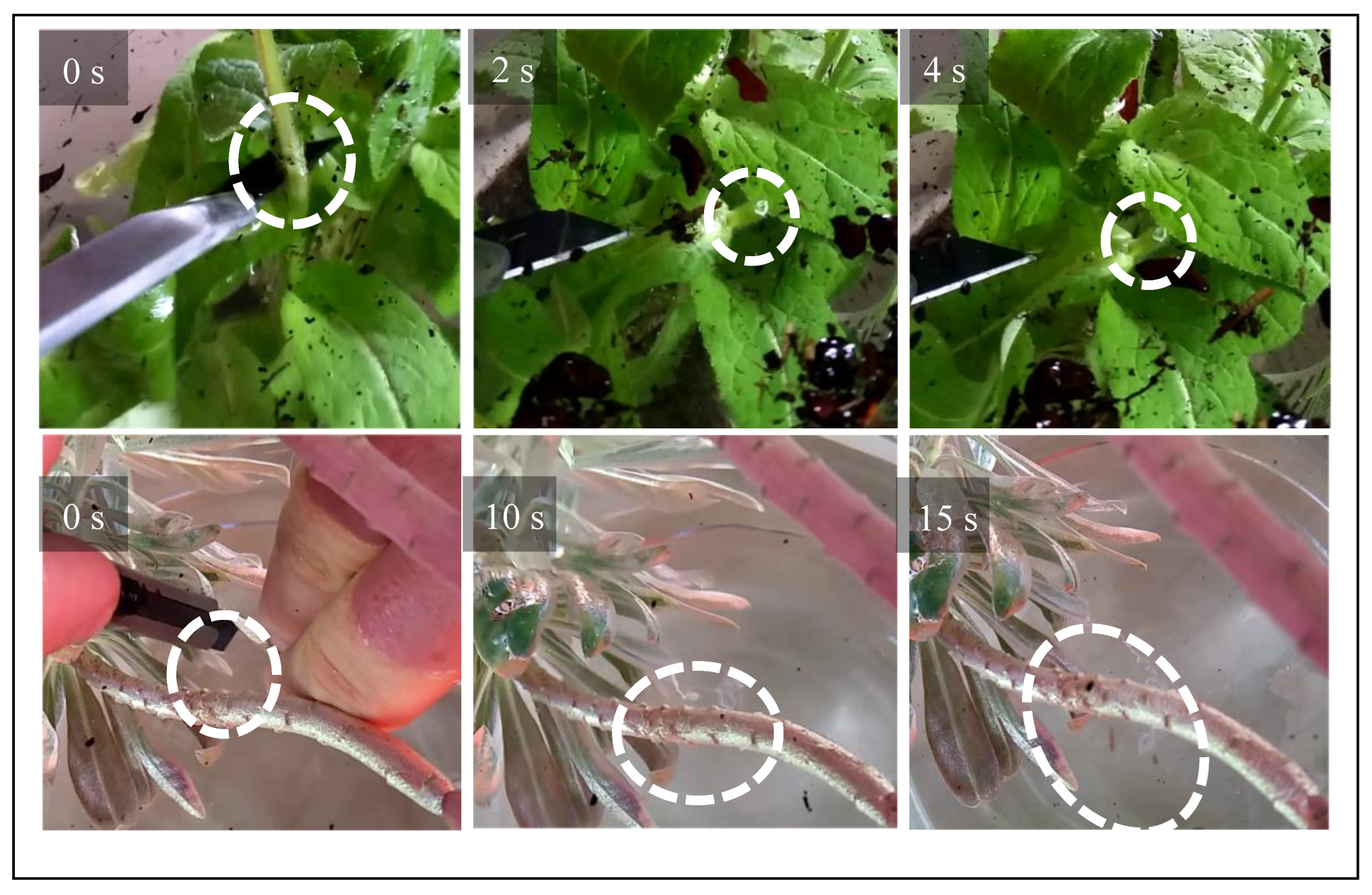

3.2. Video Microscopy on Samples Injured in Air and Under Water

Rapid solidification in the case of

C. glomerata is impressively evidenced by simply cutting the stem of the plant with a scalpel and pulling on the liquid (

Figure 3.2). An elastic thread immediately forms in the case of

C. glomerata, while the thread appears much later in the case of

E. characias. These experiments confirm the findings by Bold.[

28] The video traces, however, are less conclusive than the QCM experiments with regard to the mechanism of solidification, because what appears to be a thread might consist of a liquid cylinder surrounded by a skin. Such a skin may form quickly because both the evaporation of water and the entry of oxygen is fast close to the surface. There is a similar experiment which avoids this ambiguity. When the incision is made under water (

Figure 3.3), latex from

C. glomerata immediately forms a plug. Clearly, neither air nor physical drying are required for solidification. Latex from

E. characias, in contrast, keeps streaming away over the entire duration of the experiment, which was about one minute.

4. Discussion

Rapid solidification is evidenced by optical videos and the QCM. A first set of arguments supporting the pressure-drop hypothesis is based on kinetics alone. All other mechanisms require transport of water to the droplet surface or transport of oxygen from the surface into the bulk. If the diffusion length is larger than 300 µm, diffusive transport requires a minute, at least. The QCM as a tool to quantify the solidification kinetics has two advantages. First, the data are more quantitative than what can be learned from the inspection of optical videos. Admittedly, there was some variability in how fast the droplets were transferred from the stem of the plant to the resonator surface (≈ 10 s). Only after this transfer is complete does the QCM experiment start. Still, the QCM shows that solidification occurs within in seconds. A second advantage with regard to this problem is that the QCM probes the droplet from below. Should a skin form at the droplet–air interface, the QCM will be insensitive to the skin as illustrated in the sketches in

Figure 2.1B and C. A skin might form within seconds even when the process is rate-limited by diffusion because the diffusion path is short at the surface.

With regard to excluding physical drying as the cause for crosslinking, the pulling experiment in air is less conclusive than the QCM experiment. The pulling experiment under water is conclusive because it avoids exposure to air. These arguments do not exclude some influence of pressure in the case E. characias and the other plants studied (data not shown). The arguments do not apply to most synthetic latices, though, because these do not contain capsules or globules, which would break or dissolve following a pressure drop. All polymer dispersions studied solidified slowly (similar to all plant latices other than the one from C. glomerata). Following the lines of d’Auzac model, we propose the influx of serum into laticifers as the key intermediate step, triggering solidification. The mostly plausible mechanism for mixing is a transition from a liquid-liquid two-phase state to a single-phase state.

That leaves the question of whether there is a way to let technical latices solidify equally fast. A pressure drop is not easily realized in such settings, but a temperature jump within a few seconds or even less might be, at least for sufficiently thin films. Conceptionally, one would borrow from controlled drug release and, also, from underwater adhesion building on triggered coacervation.[

36,

37] For instance, drug release was triggered by hyperthermia in ref. [

38]. LLPS can be modulated by temperature, easily.[

39] Materials with an upper critical solution temperature (UCST) are needed because the temperature jump will always amount to heating and because the single-phase state must be the high-temperature state. In water, UCST behavior is less common than LCST behavior (that is, phase segregation at the higher temperature). UCST behavior combined with LLPS was reported in Kim et al.[

40]. The context of underwater adhesion, the solid state often is the coacervate state. Coacervation based on polyelectrolyte complexes can be cost efficient and scalable. Such methods would also have to be evaluated against UV-curing,[

41] which has similar advantages and is carried out in a similar way.

5. Conclusions

Using a fast QCM-D, it was shown that latex droplets from C. glomerata solidify much faster than droplets from other plants and, also, droplets containing technical latices. The fast kinetics suggests that solidification in the former case is triggered by a sudden decrease of pressure inside the laticifers, followed by an influx of serum into the laticifers, leading to a local mixing between a resin and a hardener. Presumably, mixing is caused by a transition from a liquid-liquid phase separated state to a single-phase state. The transition occurs in the bulk fluid with no influence of physical drying. This explanation gains support from experiments under water, where the latex exuding from an incision quickly produces a plug in the case of C. glomerata, but not in the case of E. characias. At this point, species of the genus Campanula are the only plants displaying rapid solidification of this kind, known to us. Technical processes of a similar kind exist for underwater adhesion, but not for latex films.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgements

This work was in part funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) under contract Jo-278/24-1 (no. 500106119).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicting interests to declare.

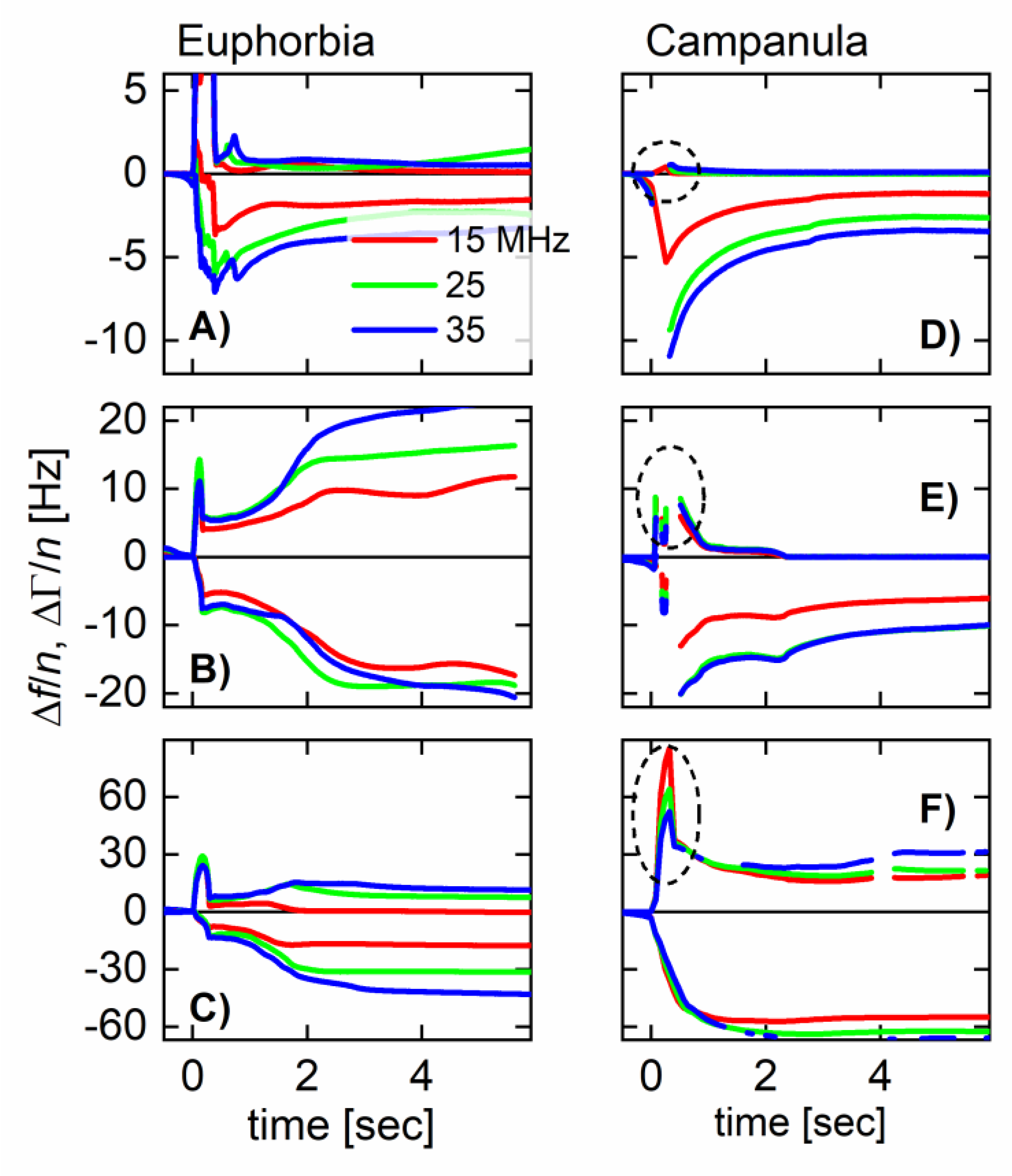

Figure for TOC

The solidification of the latex from the plant Campanula glomerata is too fast to be caused by physical drying. Presumably, solidification is triggered by a pressure drop inside the laticifers, which causes a local mixing of a resin with a hardener.

References

- G. Bauer; A. Nellesen; T. Speck. Biological Lattices In Fast Self-Repair Mechanisms In Plants And The Development Of Bio-Inspired Self-Healing Polymers. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2010, 128 (7), 453–459.

- Agrawal, A. A.; Konno, K. Latex: A Model for Understanding Mechanisms, Ecology, and Evolution of Plant Defense Against Herbivory. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2009, 40, 311–331. [CrossRef]

- Speck, O.; Speck, T. An Overview of Bioinspired and Biomimetic Self-Repairing Materials. Biomimetics 2019, 4 (1). [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J. R. Reconsidering the Functions of Latex. Trees 1994, 9 (1), 1–5. [CrossRef]

-

Polymer Dispersions Market Size. https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/polymer-dispersions-market (accessed 2024-07-27).

- Goldschmidt, H.-J. Streitberger. BASF Handbook on Basics of Coating Technology; Vincentz Network, 2003.

- Pocius, A. V. Adhesions and Adhesives Technology; Hanser Gardner, 1996.

- Groves, R.; Welche, P.; Routh, A. F. The Coagulant Dipping Process of Nitrile Latex: Investigations of Former Motion Effects and Coagulant Loss into the Dipping Compound. Soft Matter 2023, 19 (3), 468–482. [CrossRef]

- Keddie, J. L.; Routh, A. F. Fundamentals of Latex Film Formation: Processes and Properties; Springer, 2010.

- Brown, G. L. Formation of Films from Polymer Dispersions. Journal of Polymer Science 1956, 22 (102), 423–434. [CrossRef]

- Kessel, N.; Illsley, D. R.; Keddie, J. L. The Diacetone Acrylamide Crosslinking Reaction and Its Influence on the Film Formation of an Acrylic Latex. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2008, 5 (3), 285–297. [CrossRef]

- Voyutskii, S. S.; Ustinova, Z. M. Role of Autohesion During Film Formation from Latex. J. Adhes. 1977, 9 (1), 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. W.; Winnik, M. A. Functional Latex and Thermoset Latex Films. JCT Res. 2004, 1 (3), 163–190.

- Wang, Y. C.; Zhao, C. L.; Winnik, M. A. Molecular-Diffusion and Latex Film Formation - an Analysis of Direct Nonradiative Energy-Transfer Experiments. Journal of Chemical Physics 1991, 95 (3), 2143–2153. [CrossRef]

- A.D.T. Gorton. Latex Dipping I. Relationship Between Dwell Time, Latex Compound Viscosity and Deposit Thickness. Journal of the Rubber Research Institute of Malaya 1967, 20, 27.

- Renganathan, S.; Khan, N.; Srinivasan, R. Drying of Lithium-Ion Battery Negative Electrode Coating: Estimation of Transport Parameters. DRYING TECHNOLOGY 2022, 40 (10), 2188–2198. [CrossRef]

- Guerrier, B.; Bouchard, C.; Allain, C.; Benard, C. Drying Kinetics of Polymer Films. Aiche J. 1998, 44 (4), 791–798. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S. H.; White, S. R.; Braun, P. V. Self-Healing Polymer Coatings. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21 (6), 645-+. [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.; Vale, M.; Galhano, R.; Matos, S.; Bordado, J.; Pinho, I.; Marques, A. Microencapsulation of Isocyanate in Biodegradable Poly(ε-Caprolactone) Capsules and Application in Monocomponent Green Adhesives. ACS APPLIED POLYMER MATERIALS 2020, 2 (11), 4425–4438. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Demchuk, Z.; Tian, J.; Luo, J.; Li, B.; Cao, K.; Sokolov, A.; Hun, D.; Saito, T.; Cao, P. Ductile Adhesive Elastomers with Force-Triggered Ultra-High Adhesion Strength. MATERIALS HORIZONS 2024, 11 (4), 969–977. [CrossRef]

- Gidrol, X.; Chrestin, H.; Tan, H. L.; Kush, A. Hevein, a Lectin-like Protein from Hevea Brasiliensis (Rubber Tree) Is Involved in the Coagulation of Latex. J Biol Chem 1994, 269 (12), 9278–9283.

- S. W. Pakianathan; S. G. Boatman; D. H. Taysum. Particle Aggregation Following Dilution of Hevea Latex: A Possible Mechanism for the Closure of Latex Vessels after Tapping. Journal of the Rubber Research Institute of Malaya 1966, 19 (5), 259.

- J. d’Auzac; H. Cretin; B. Marin; C. Lioret. A Plant Vacuolar System: The Lutoids from Hevea Brasiliensis Latex. Physiol Veg. 1982, 20 (2), 311–331.

- M.H.M.Wermelink,; M.L. Becker,; R. Konradi,; C. Taranta,; M: Ranft,; S.Nord,; J. Rühe,; T. Speck,; S. Kruppert; H.M. Maartje, Wermelink1,2, Merle L. Becker1, Rupert Konradi3,4, Claude Taranta5, Meik Ranft4, Simon Nord5, Jürgen Rühe2,3,6, Thomas Speck1,2,3, S. Kruppert. Towards Understanding the Fast Coagulation in Campanula Spp. in preparation.

- Cinar, H.; Fetahaj, Z.; Cinar, S.; Vernon, R. M.; Chan, H. S.; Winter, R. H. A. Temperature, Hydrostatic Pressure, and Osmolyte Effects on Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation in Protein Condensates: Physical Chemistry and Biological Implications. Chemistry – A European Journal 2019, 25 (57), 13049–13069. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. X.; Haataja, M. P.; Košmrlj, A.; Datta, S. S.; Arnold, C. B.; Priestley, R. D. Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation within Fibrillar Networks. Nature Communications 2023, 14 (1), 6085. [CrossRef]

- Rose, G.; Harris, J.; McCann, G.; Weishuhn, J.; Schmidt, D. Rapid Gel-like Latex Film Formation through Controlled Ionic Coacervation of Latex Polymer Particles Containing Strong Cationic and Protonated Weak Acid Functionalities. LANGMUIR 2005, 21 (4), 1192–1200. [CrossRef]

- Georg Bold. Chemisch-Stukturell Basierte Selbstreparaturprozesse Bei Pflanzen Und Die Bionische Übertragung Auf Technische Elastomere, Freiburg, 2012.

- Bauer, G.; Friedrich, C.; Gillig, C.; Vollrath, F.; Speck, T.; Holland, C. Investigating the Rheological Properties of Native Plant Latex. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2014, 11 (90), 20130847. [CrossRef]

- Leppin, C.; Hampel, S.; Meyer, F. S.; Langhoff, A.; Fittschen, U. E. A.; Johannsmann, D. A Quartz Crystal Microbalance, Which Tracks Four Overtones in Parallel with a Time Resolution of 10 Milliseconds: Application to Inkjet Printing. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20 (20). [CrossRef]

- Woldeyes, M. A.; Qi, W.; Razinkov, V. I.; Furst, E. M.; Roberts, C. J. Temperature Dependence of Protein Solution Viscosity and Protein–Protein Interactions: Insights into the Origins of High-Viscosity Protein Solutions. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2020, 17 (12), 4473–4482. [CrossRef]

- Hutter, C.; Platz, D.; Tholen, E. A.; Hansson, T. H.; Haviland, D. B. Reconstructing Nonlinearities with Intermodulation Spectroscopy. Physical Review Letters 2010, 104 (5), 050801. [CrossRef]

- Johannsmann, D.; Langhoff, A.; Leppin, C. Studying Soft Interfaces with Shear Waves: Principles and Applications of the Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM). Sensors 2021, 21 (10), 3490. [CrossRef]

- Wiegmann, J.; Leppin, C.; Langhoff, A.; Schwaderer, J.; Beuermann, S.; Johannsmann, D.; Weber, A. P. Influence of the Solvent Evaporation Rate on the β-Phase Content of Electrosprayed PVDF Particles and Films Studied by a Fast Multi-Overtone QCM. Advanced Powder Technology 2022, 33 (3), 103452. [CrossRef]

- Lucklum, R.; Schranz, S.; Behling, C.; Eichelbaum, F.; Hauptmann, P. Analysis of Compressional-Wave Influence on Thickness-Shear-Mode Resonators in Liquids. Sensors and Actuators a-Physical 1997, 60 (1–3), 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Dompé, M.; Cedano-Serrano, F.; Vahdati, M.; van Westerveld, L.; Hourdet, D.; Creton, C.; van der Gucht, J.; Kodger, T.; Kamperman, M. Underwater Adhesion of Multiresponsive Complex Coacervates. ADVANCED MATERIALS INTERFACES 2020, 7 (4). [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Stewart, R. Biomimetic Underwater Adhesives with Environmentally Triggered Setting Mechanisms. ADVANCED MATERIALS 2010, 22 (6), 729-+. [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Lammers, T.; Ten Hagen, T. L. M. Temperature-Sensitive Polymers to Promote Heat-Triggered Drug Release from Liposomes: Towards Bypassing EPR. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2022, 189, 114503. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J. D.; Caliari, S. R.; Lampe, K. J. Temperature-Dependent Complex Coacervation of Engineered Elastin-like Polypeptide and Hyaluronic Acid Polyelectrolytes. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19 (10), 3925–3935. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jeon, B.; Kim, S.; Jho, Y.; Hwang, D. S. Upper Critical Solution Temperature (UCST) Behavior of Coacervate of Cationic Protamine and Multivalent Anions. Polymers 2019, 11 (4). [CrossRef]

- MANSER, A. PLASTIC FOIL LAMINATING USING UV CURABLE ADHESIVES. KUNSTSTOFFE-GERMAN PLASTICS 1991, 81 (9), 760–763.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).