Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A wide-ranging comparison of many common machine learning methods for predicting tower-based FCO2;

- The discovery of a generalizable machine learning-based model that can predict FCO2 to within 1.81molm−2s−1 of tower-based measurements;

- An open source gap-filled FCO2 dataset covering 44 unique sites for free use by other researchers in the climate science community; and

- An open source code repository for reproducibility and wider implementation.

2. Background Information

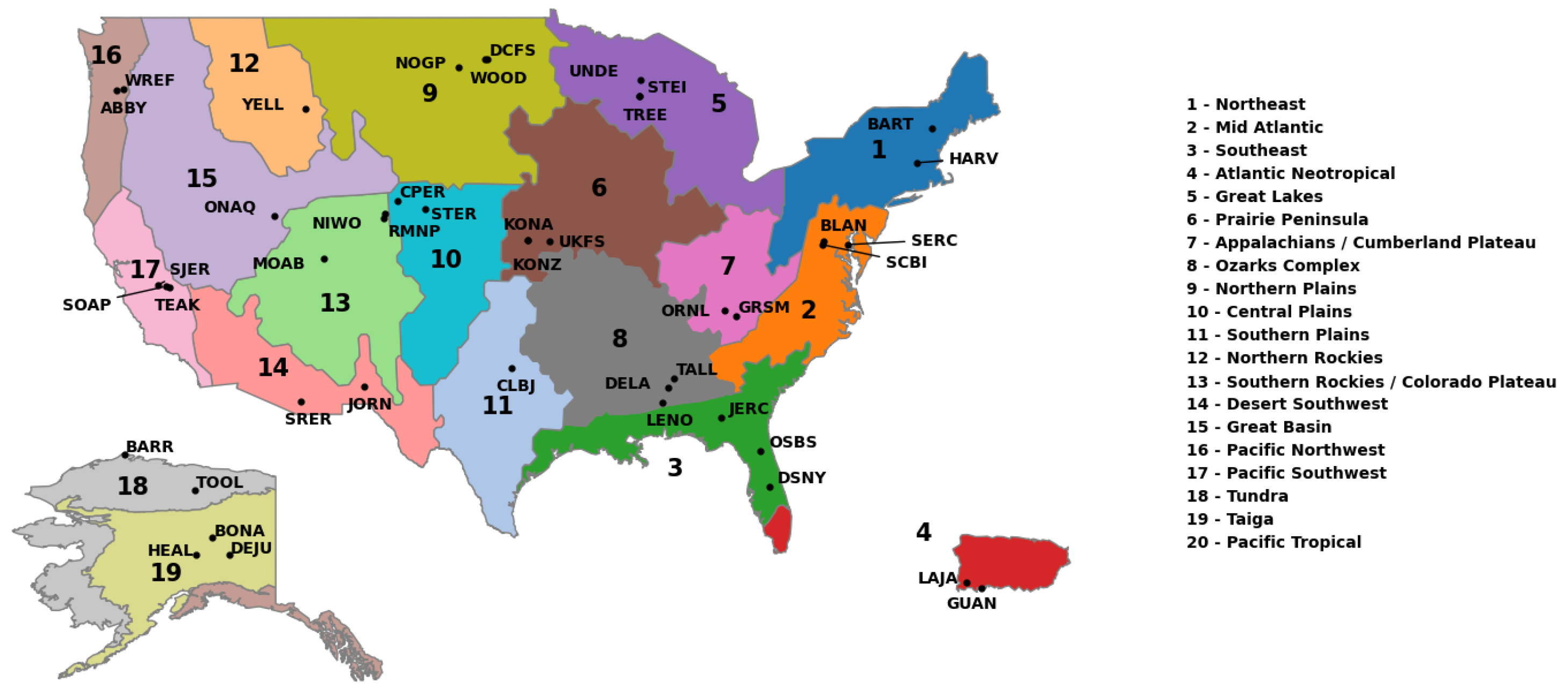

2.1. The AmeriFlux network

2.2. Natural Climate Solutions

3. Literature Review

4. Methods

4.1. Data

- Agricultural (AG)

- Deciduous Broadleaf (DB)

- Evergreen Broadleaf (EB)

- Evergreen Needleleaf (EN)

- Grassland (GR)

- Shrub (SH)

- Tundra (TN)

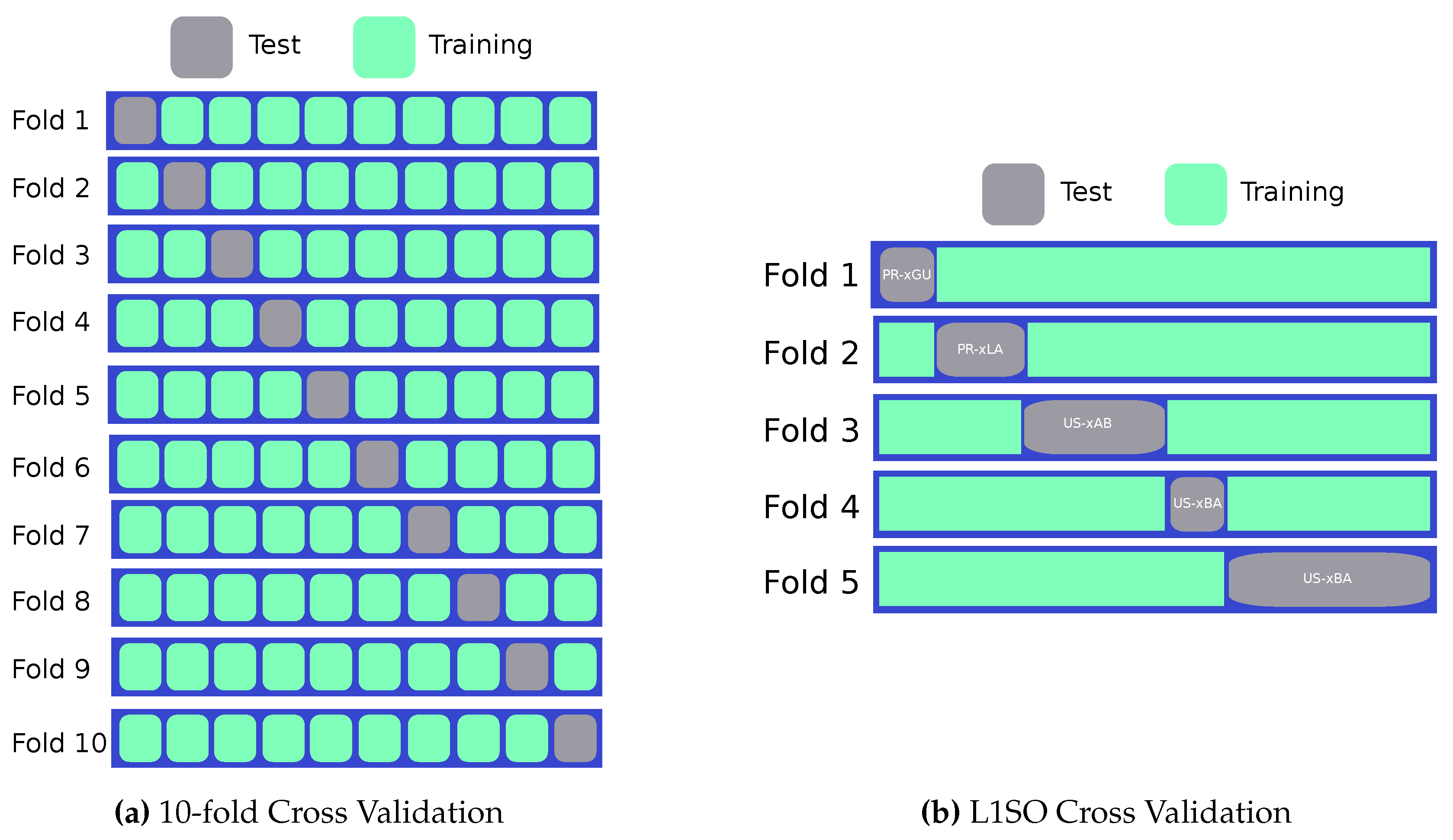

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Machine Learning Models

- Linear Regression (all predictors): This is a linear model including all of the variables using the maximum likelihood estimates for the coefficients. Linear regression assumes a linear relationship between the predictors and the response variable, which is unlikely in complex modeling problems, but does provide a baseline for the comparison of the performance of other models.

- Stepwise Linear Regression: This model began by testing for the most significant single variable in a linear regression model, and then iteratively added variables and tested for greatest improvement. A threshold number of selection variables was set to 15 for this forward selection technique. In this way, we simplify the basic linear regression model to find feature variables with greater importance for linear prediction.

- Decision Tree: A decision tree is a model based on recursively splitting the data on values of variables to maximize the difference between observations. Decision trees are most effective on problems where there is a non-linear relationship between the predictors and response variable [33,51]. The optimal tree depth was found to be 10 which was found through cross-validation.

- Random Forest: A random forest model [7] is a bagged ensemble of decision trees. The algorithm creates an uncorrelated forest of decision trees by using random subsets of features in each tree. When predicting a regression variable with a random forest model, the overall prediction is the average of the results of each of its constituent trees.

- Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): The XGBoost model [8] is a boosted ensemble of n underfit decision tree models. In practice, a decision tree is fit the to data and the errors in prediction are measured. Next, a second decision tree is used to fit the errors of the first tree. Then a third decision tree is fit to the errors of the second tree, and we continue until we have n trees in our ensemble. The optimal number of trees in our ensemble was found to be 2000. We also set the number of rounds for early stopping to be 50, and we used a learning rate of 0.05, max depth of 10, subsample ratio of 0.5, and subsample ratio of columns for each node of 0.45. Finally we used the histogram-optimized approximate greedy algorithm for tree construction to optimize our XGBoost model. All hyperparameters were optimized through 10-fold cross-validation using an exhaustive grid search.

- Neural Network (single-layer): A neural network is the sum of weighted non-linear functions of the predictor variables. This model is a single-layer neural network, with 256 neurons in the hidden layer, and uses a feed-forward architecture with ReLU activation. Early stopping was implemented to prevent model over-fitting, and training was performed with a data loader with a batch size of 128. The learning rate was set to 0.0003, and the best performance was achieved with no weight decay using the Adam optimizer. For more information on the mathematics of neural networks, see: [22,30].

- Deep Neural Network: The model uses the same mathematical structure as the single-layer neural network, but increases the number of hidden layers to 3, each consisting of 256 neurons. Compared to the single-layer neural network, the increased depth of the model increases the number of parameters to learn, meaning the model is capable of modeling more complex relationships, but also takes longer to learn from the data.

5. Results

5.1. 10-Fold Cross-Validation Results

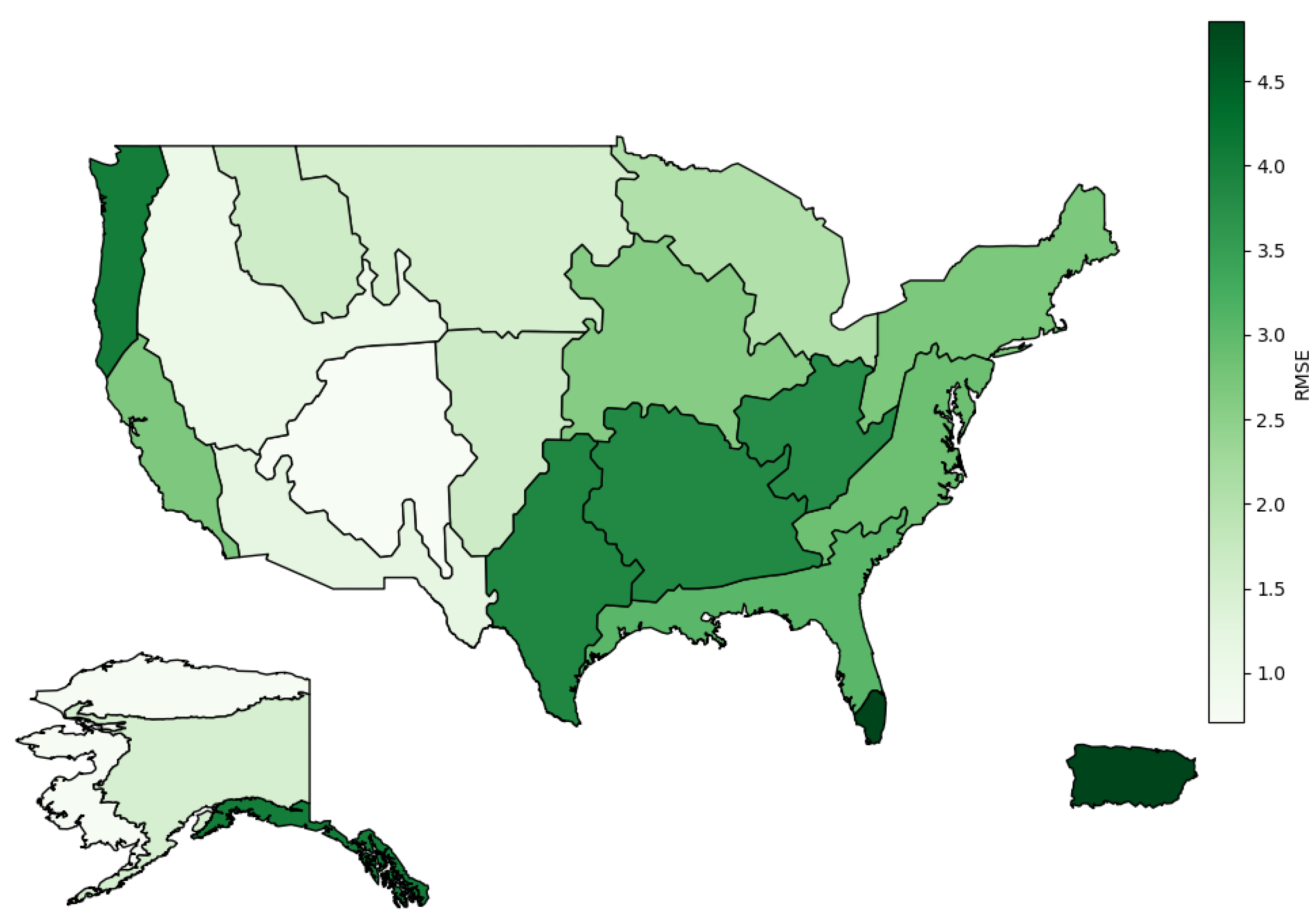

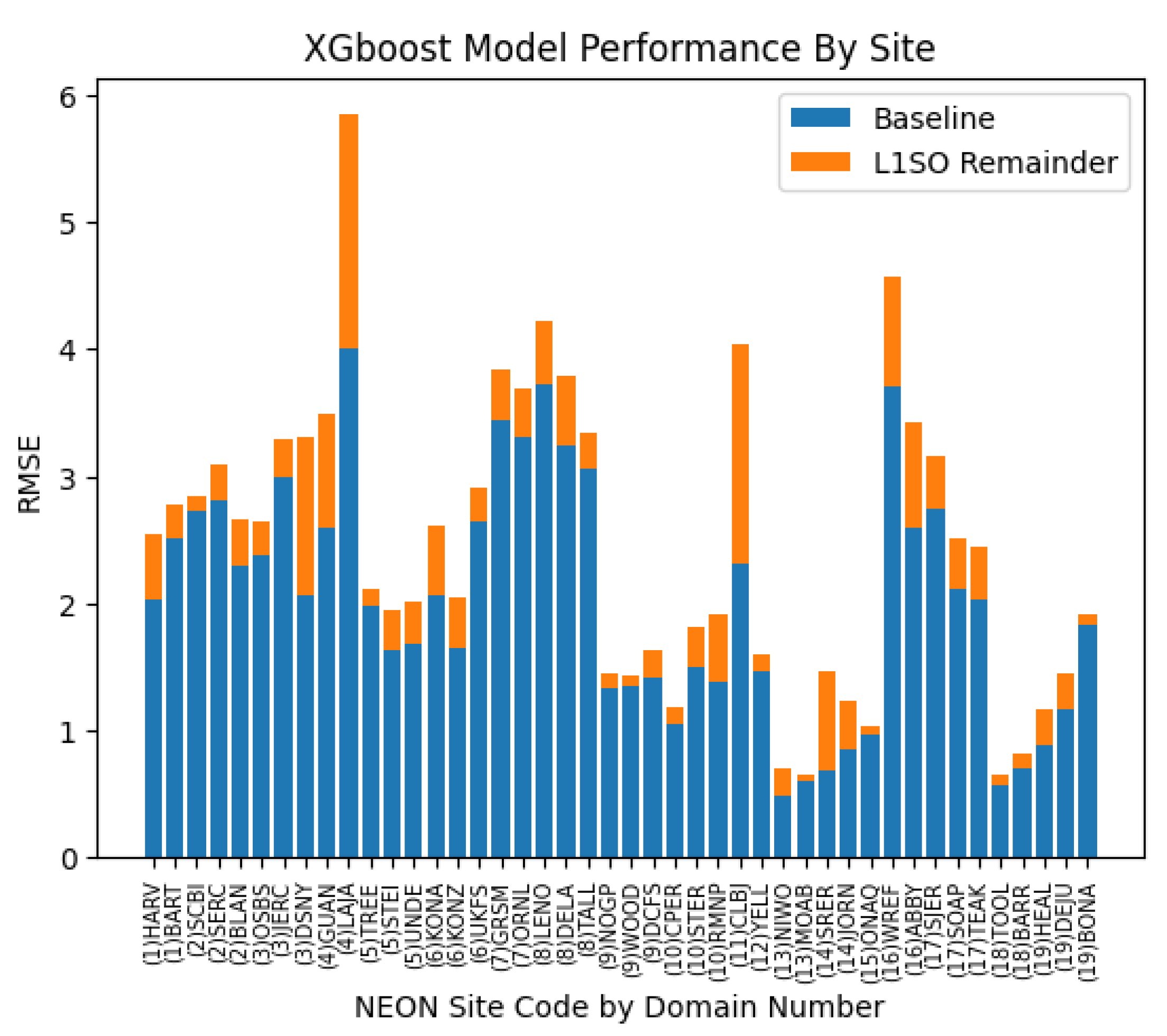

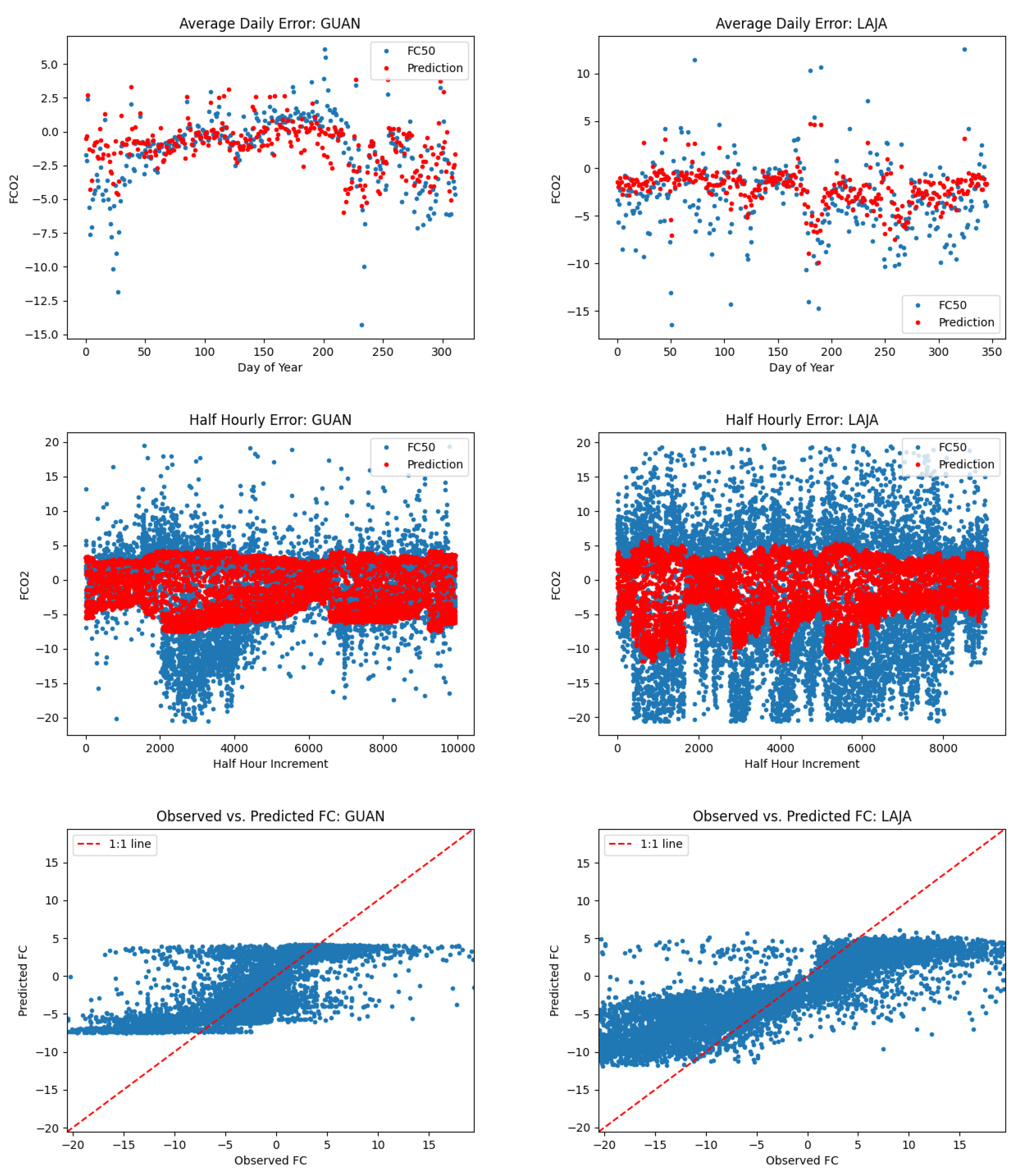

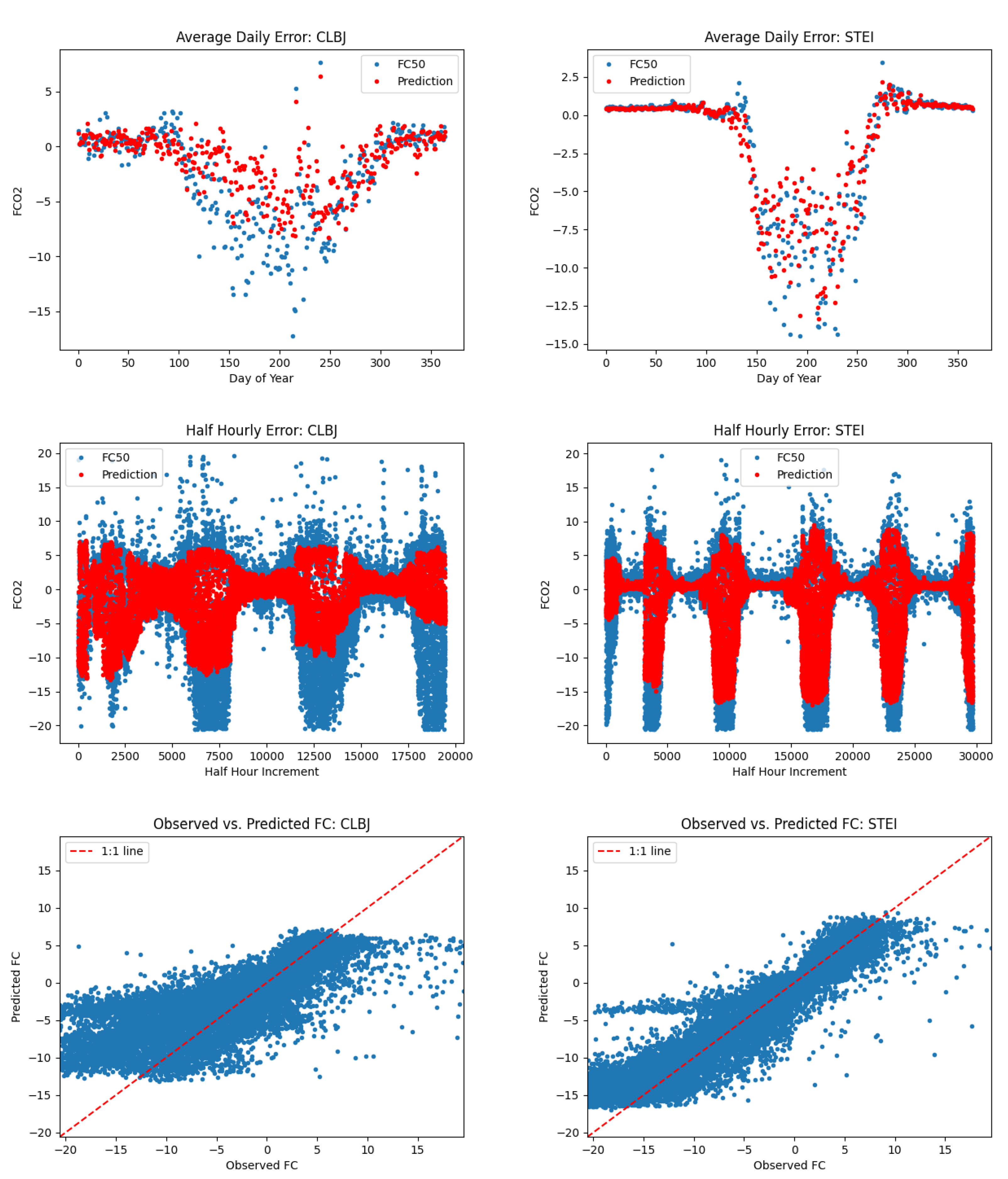

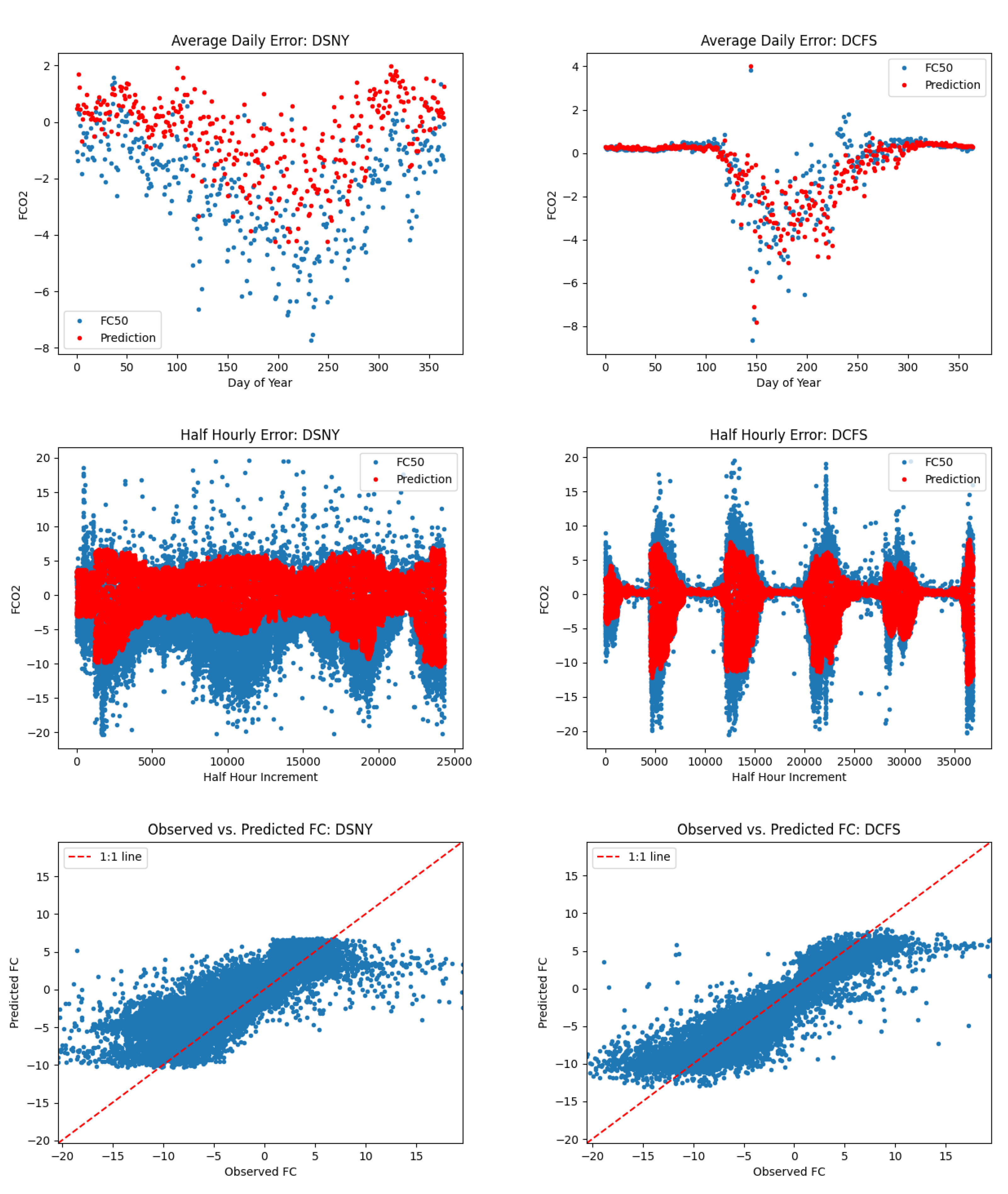

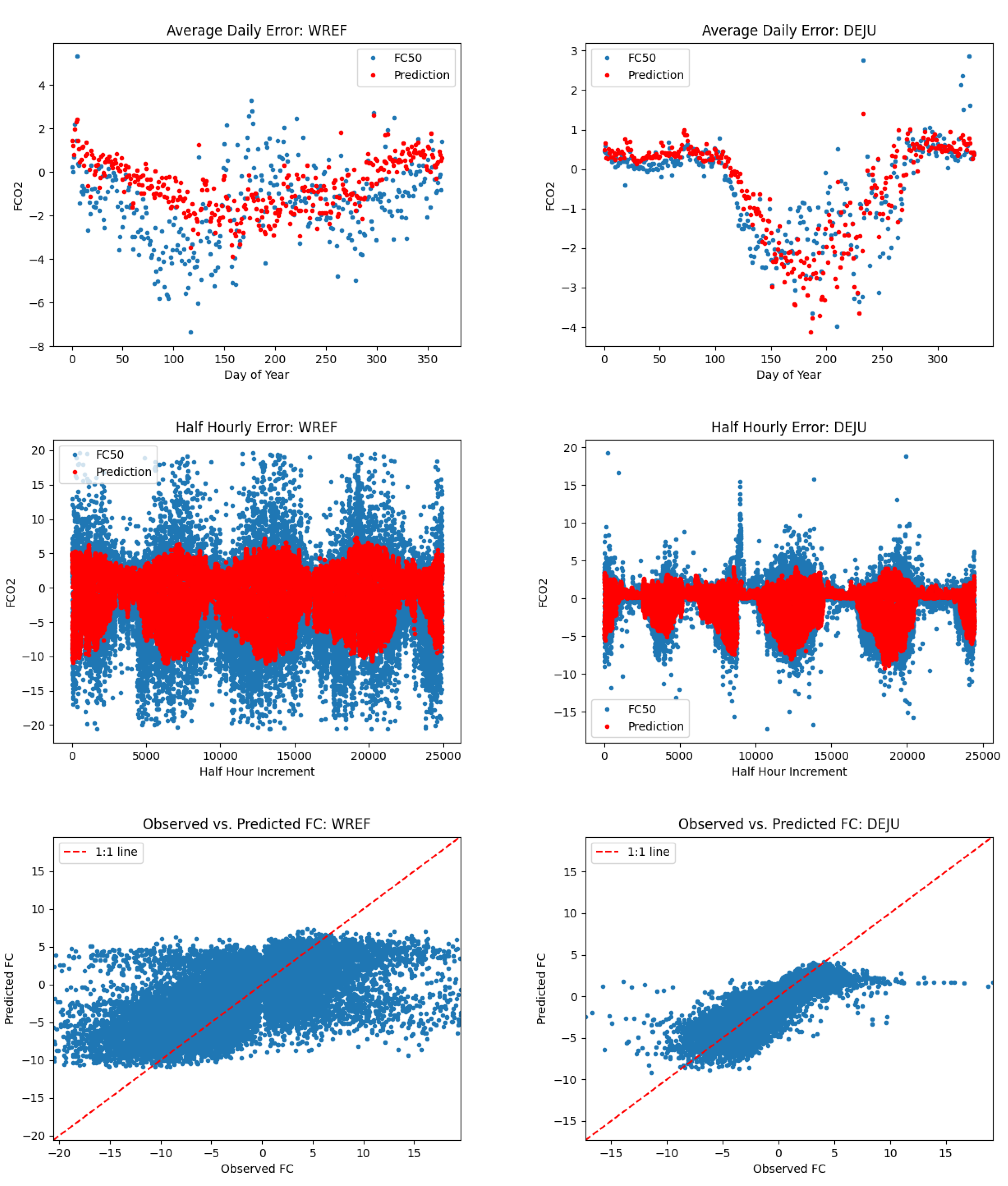

5.2. L1SO Cross-Validation Results

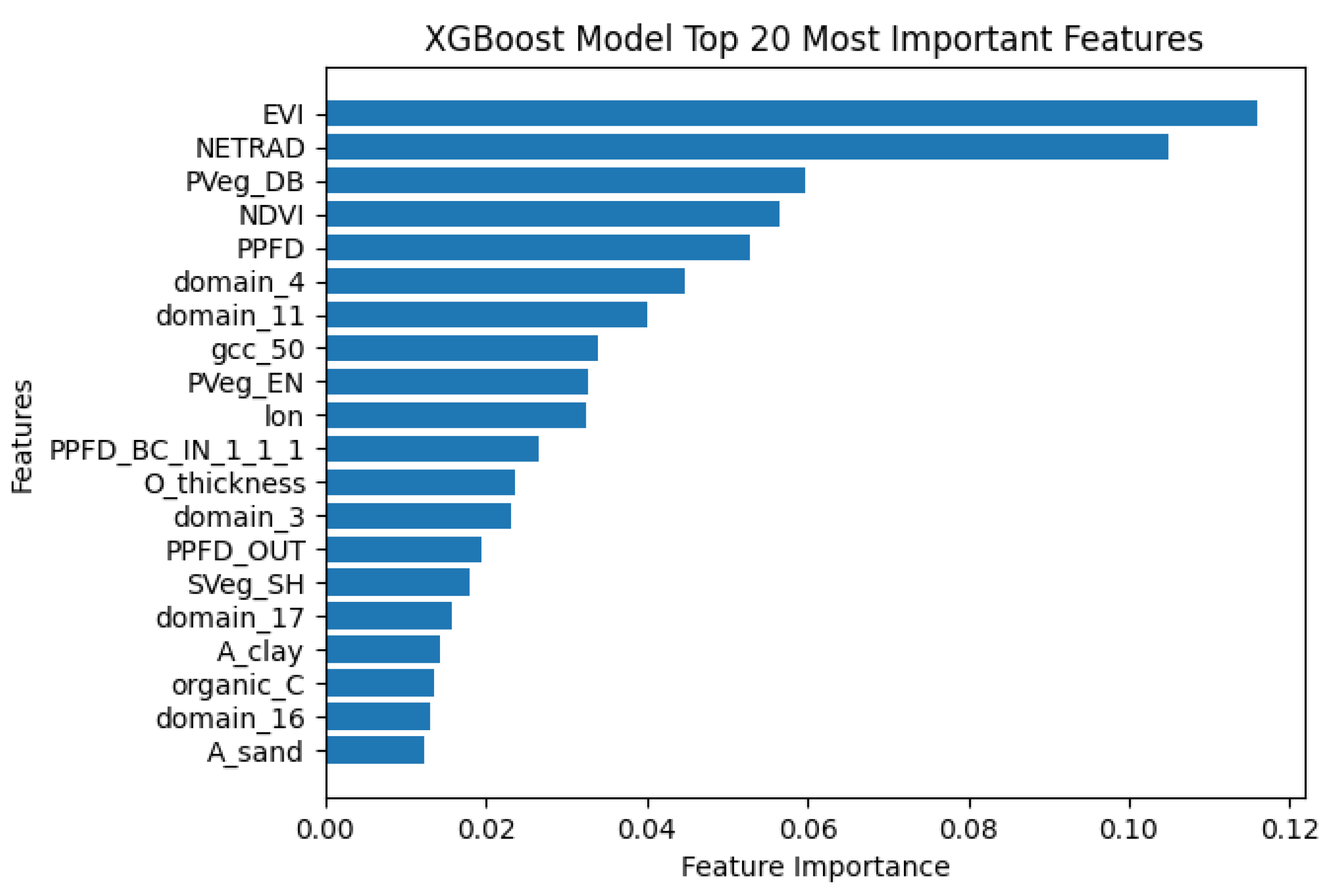

5.3. XGBoost Feature Importance

6. Discussion

6.1. Comparison of 10-fold and L1SO experimental results

6.2. Relevance of L1SO predictions for unseen sites

6.3. Leveraging Site-level Data when Standardized Model Inputs are not Available

6.4. Annual carbon sums

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AlOmar MK, Hameed MM, Al-Ansari N, Razali SFM, AlSaadi MA (2023) Short-, medium-, and long-term prediction of carbon dioxide emissions using wavelet-enhanced extreme learning machine. Civil Engineering Journal 9(4):815–834. [CrossRef]

- Baareh AK (2013) Solving the carbon dioxide emission estimation problem: An artificial neural network model. Journal of Software Engineering and Applications 6:338–342.

- Baldocchi DD (2020) How eddy covariance flux measurements have contributed to our understanding of global change biology. Global Change Biology 26(1):242–260.

- Battelle (2024) National Science Foundation’s National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON). https://www.neonscience.org/.

- Bossio D, Cook-Patton S, Ellis P, Fargione J, Sanderman J, Smith P, Wood S, Zomer R, Von Unger M, Emmer I, et al. (2020) The role of soil carbon in natural climate solutions. Nature Sustainability 3(5):391–398. [CrossRef]

- Braswell BH, Sacks WJ, Linder E, Schimel DS (2005) Estimating diurnal to annual ecosystem parameters by synthesis of a carbon flux model with eddy covariance net ecosystem exchange observations. Global Change Biology 11(2):335–355.

- Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Machine learning 45:5–32.

- Chen T, Guestrin C (2016) Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, pp 785–794.

- Chu H, Christianson DS, Cheah YW, Pastorello G, O’Brien F, Geden J, Ngo ST, Hollowgrass R, Leibowitz K, Beekwilder NF, et al. (2023) Ameriflux base data pipeline to support network growth and data sharing. Scientific Data 10(1):614. [CrossRef]

- Dietze MC, Vargas R, Richardson AD, Stoy PC, Barr AG, Anderson RS, Arain MA, Baker IT, Black TA, Chen JM, et al. (2011) Characterizing the performance of ecosystem models across time scales: A spectral analysis of the north american carbon program site-level synthesis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 116(G4). [CrossRef]

- Dou X, Yang Y, Luo J (2018) Estimating forest carbon fluxes using machine learning techniques based on eddy covariance measurements. Sustainability 10(1):203.

- Durmanov A, Saidaxmedova N, Mamatkulov M, Rakhimova K, Askarov N, Khamrayeva S, Mukhtorov A, Khodjimukhamedova S, Madumarov T, Kurbanova K (2023) Sustainable growth of greenhouses: investigating key enablers and impacts. Emerging Science Journal 7(5):1674–1690.

- Ellis PW, Page AM, Wood S, Fargione J, Masuda YJ, Carrasco Denney V, Moore C, Kroeger T, Griscom B, Sanderman J, et al. (2024) The principles of natural climate solutions. Nature Communications 15(1):547. [CrossRef]

- Fang D, Zhang X, Yu Q, Jin TC, Tian L (2018) A novel method for carbon dioxide emission forecasting based on improved gaussian processes regression. Journal of cleaner production 173:143–150.

- Fargione JE, Bassett S, Boucher T, Bridgham SD, Conant RT, Cook-Patton SC, Ellis PW, Falcucci A, Fourqurean JW, Gopalakrishna T, et al. (2018) Natural climate solutions for the united states. Science Advances 4(11):eaat1869. [CrossRef]

- Fer I, Kelly R, Moorcroft PR, Richardson AD, Cowdery EM, Dietze MC (2018) Linking big models to big data: efficient ecosystem model calibration through bayesian model emulation. Biogeosciences 15(19):5801–5830.

- Griscom BW, Adams J, Ellis PW, Houghton RA, Lomax G, Miteva DA, Schlesinger WH, Shoch D, Siikamäki JV, Smith P, et al. (2017) Natural climate solutions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(44):11645–11650.

- Hamrani A, Akbarzadeh A, Madramootoo CA (2020) Machine learning for predicting greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural soils. Science of The Total Environment 741:140338.

- Hemes KS, Runkle BR, Novick KA, Baldocchi DD, Field CB (2021) An ecosystem-scale flux measurement strategy to assess natural climate solutions. Environmental science & technology 55(6):3494–3504.

- Hollinger D, Davidson E, Fraver S, Hughes H, Lee J, Richardson A, Savage K, Sihi D, Teets A (2021) Multi-decadal carbon cycle measurements indicate resistance to external drivers of change at the howland forest ameriflux site. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 126(8):e2021JG006276.

- Hou Y, Liu S (2024) Predictive modeling and validation of carbon emissions from china’s coastal construction industry: A bo-xgboost ensemble approach. Sustainability 16(10):4215.

- James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R (2021) An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R: 2nd Edition. Springer, URL https://faculty.marshall.usc.edu/gareth-james/ISL/.

- Jung M, Schwalm C, Migliavacca M, Walther S, Camps-Valls G, Koirala S, Anthoni P, Besnard S, Bodesheim P, Carvalhais N, Chevallier F, Gans F, Goll DS, Haverd V, Köhler P, Ichii K, Jain AK, Liu J, Lombardozzi D, Nabel JEMS, Nelson JA, O’Sullivan M, Pallandt M, Papale D, Peters W, Pongratz J, Rödenbeck C, Sitch S, Tramontana G, Walker A, Weber U, Reichstein M (2020) Scaling carbon fluxes from eddy covariance sites to globe: synthesis and evaluation of the fluxcom approach. Biogeosciences 17(5):1343–1365.

- Kang Y, Gaber M, Bassiouni M, Lu X, Keenan T (2023) Cedar-gpp: spatiotemporally upscaled estimates of gross primary productivity incorporating co 2 fertilization. Earth System Science Data Discussions 2023:1–51.

- Keenan T, Baker I, Barr A, Ciais P, Davis K, Dietze M, Dragoni D, Gough CM, Grant R, Hollinger D, et al. (2012) Terrestrial biosphere model performance for inter-annual variability of land-atmosphere co2 exchange. Global Change Biology 18(6):1971–1987.

- Lee H, Calvin K, Dasgupta D, Krinner G, Mukherji A, Thorne P, Trisos C, Romero J, Aldunce P, Barret K, Blanco G, Cheung WW, Connors SL, Denton F, Diongue-Niang A, Dodman D, Garschagen M, Geden O, Hayward B, Jones C, Jotzo F, Krug T, Lasco R, Lee YY, Masson-Delmotte V, Meinshausen M, Mintenbeck K, Mokssit A, Otto FE, Pathak M, Pirani A, Poloczanska E, Pörtner HO, Revi A, Roberts DC, Roy J, Ruane AC, Skea J, Shukla PR, Slade R, Slangen A, Sokona Y, Sörensson AA, Tignor M, van Vuuren D, Wei YM, Winkler H, Zhai P, Zommers Z, Hourcade JC, Johnson FX, Pachauri S, Simpson NP, Singh C, Thomas A, Totin E, Arias P, Bustamante M, Elgizouli I, Flato G, Howden M, Méndez-Vallejo C, Pereira JJ, Pichs-Madruga R, Rose SK, Saheb Y, Rodríguez RS, Ürge-Vorsatz D, Xiao C, Yassaa N, Alegría A, Armour K, Bednar-Friedl B, Blok K, Cissé G, Dentener F, Eriksen S, Fischer E, Garner G, Guivarch C, Haasnoot M, Hansen G, Hauser M, Hawkins E, Hermans T, Kopp R, Leprince-Ringuet N, Lewis J, Ley D, Ludden C, Niamir L, Nicholls Z, Some S, Szopa S, Trewin B, van der Wijst KI, Winter G, Witting M, Birt A, Ha M, Romero J, Kim J, Haites EF, Jung Y, Stavins R, Birt A, Ha M, Orendain DJA, Ignon L, Park S, Park Y (2023) IPCC, 2023: Climate change 2023: Synthesis report, summary for policymakers. Contribution of working groups i, ii and iii to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. Technical report, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Geneva, Switzerland.

- Lucas B, Pelletier C, Inglada J, Schmidt D, Webb G I, and Petitjean F (2019) Exploring Data Quantity Requirements for Domain Adaptation in the Classification of Satellite Image Time Series. In: 10th International Workshop on the Analysis of Multitemporal Remote Sensing Images (MultiTemp), Shanghai, China, 2019, pp. 1-4.

- Lucas B, Pelletier C, Schmidt D, Webb G I, and Petitjean F (2020) Unsupervised Domain Adaptation Techniques for Classification of Satellite Image Time Series, In: IGARSS 2020 - 2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2020, pp. 1074-1077.

- Madan T, Sagar S, Virmani D (2020) Air quality prediction using machine learning algorithms –a review. In: 2020 2nd International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication Control and Networking, pp 140–145.

- Mahabbati A, Beringer J, Leopold M, McHugh I, Cleverly J, Isaac P, Izady A (2021) A comparison of gap-filling algorithms for eddy covariance fluxes and their drivers. Geoscientific Instrumentation, Methods and Data Systems 10(1):123–140.

- Mardani A, Liao H, Nilashi M, Alrasheedi M, Cavallaro F (2020) A multi-stage method to predict carbon dioxide emissions using dimensionality reduction, clustering, and machine learning techniques. Journal of Cleaner Production 275:122942.

- National Ecological Observatory Network (2024) Bundled data products - eddy covariance (dp4.00200.001). URL https://data.neonscience.org/data-products/DP4.00200.001/RELEASE-2024.

- Nie F, Zhu W, Li X (2020) Decision tree svm: An extension of linear svm for non-linear classification. Neurocomputing 401:153–159.

- Novick KA, Biederman J, Desai A, Litvak M, Moore DJ, Scott R, Torn M (2018) The AmeriFlux network: A coalition of the willing. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 249:444–456.

- Papale D, Valentini R (2003) A new assessment of european forests carbon exchanges by eddy fluxes and artificial neural network spatialization. Global Change Biology 9(4):525–535.

- Ricciuto DM, Davis KJ, Keller K (2008) A bayesian calibration of a simple carbon cycle model: The role of observations in estimating and reducing uncertainty. Global biogeochemical cycles 22(2).

- Richardson AD, Anderson RS, Arain MA, Barr AG, Bohrer G, Chen G, Chen JM, Ciais P, Davis KJ, Desai AR, et al. (2012a) Terrestrial biosphere models need better representation of vegetation phenology: results from the n orth a merican c arbon p rogram s ite s ynthesis. Global Change Biology 18(2):566–584.

- Richardson AD, Aubinet M, Barr AG, Hollinger DY, Ibrom A, Lasslop G, Reichstein M (2012b) Uncertainty quantification. In: Aubinet M, Vesala T, Papale D (eds) Eddy Covariance: A Practical Guide to Measurement and Data Analysis, Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp 173–209.

- Richardson AD, Hufkens K, Milliman T, Aubrecht DM, Chen M, Gray JM, Johnston MR, Keenan TF, Klosterman ST, Kosmala M, et al. (2018) Tracking vegetation phenology across diverse north american biomes using phenocam imagery. Scientific data 5(1):1–24. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez JD, Perez A, Lozano JA (2009) Sensitivity analysis of k-fold cross validation in prediction error estimation. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 32(3):569–575.

- Safaei-Farouji M, Thanh HV, Dai Z, Mehbodniya A, Rahimi M, Ashraf U, Radwan AE (2022) Exploring the power of machine learning to predict carbon dioxide trapping efficiency in saline aquifers for carbon geological storage project. Journal of Cleaner Production 372:133778.

- Schaefer K, Schwalm CR, Williams C, Arain MA, Barr A, Chen JM, Davis KJ, Dimitrov D, Hilton TW, Hollinger DY, et al. (2012) A model-data comparison of gross primary productivity: Results from the north american carbon program site synthesis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 117(G3). [CrossRef]

- Schimel DS, House JI, Hibbard KA, Bousquet P, Ciais P, Peylin P, Braswell BH, Apps MJ, Baker D, Bondeau A, et al. (2001) Recent patterns and mechanisms of carbon exchange by terrestrial ecosystems. Nature 414(6860):169–172. [CrossRef]

- Schwalm CR, Williams CA, Schaefer K, Anderson R, Arain MA, Baker I, Barr A, Black TA, Chen G, Chen JM, et al. (2010) A model-data intercomparison of co2 exchange across north america: Results from the north american carbon program site synthesis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 115(G3). [CrossRef]

- Seyednasrollah B, Young AM, Hufkens K, Milliman T, Friedl MA, Frolking S, Richardson AD (2019) Tracking vegetation phenology across diverse biomes using version 2.0 of the phenocam dataset. Scientific data 6(1):222.

- Siqueira M, Katul GG, Sampson D, Stoy PC, Juang JY, McCarthy HR, Oren R (2006) Multiscale model intercomparisons of co2 and h2o exchange rates in a maturing southeastern us pine forest. Global Change Biology 12(7):1189–1207.

- Stoy PC, Dietze MC, Richardson AD, Vargas R, Barr AG, Anderson RS, Arain MA, Baker IT, Black TA, Chen JM, Cook RB, Gough CM, Grant RF, Hollinger DY, Izaurralde RC, Kucharik CJ, Lafleur P, Law BE, Liu S, Lokupitiya E, Luo Y, Munger JW, Peng C, Poulter B, Price DT, Ricciuto DM, Riley WJ, Sahoo AK, Schaefer K, Schwalm CR, Tian H, Verbeeck H, Weng E (2013) Evaluating the agreement between measurements and models of net ecosystem exchange at different times and timescales using wavelet coherence: an example using data from the north american carbon program site-level interim synthesis. Biogeosciences 10(11):6893–6909.

- Tramontana G, Jung M, Schwalm CR, Ichii K, Camps-Valls G, Ráduly B, Reichstein M, Arain MA, Cescatti A, Kiely G, Merbold L, Serrano-Ortiz P, Sickert S, Wolf S, Papale D (2016) Predicting carbon dioxide and energy fluxes across global fluxnet sites with regression algorithms. Biogeosciences 13(14):4291–4313.

- United States Department of Energy (2023) AmeriFlux Management Project. https://ameriflux.lbl.gov/.

- Vais A, Mikhaylov P, Popova V, Nepovinnykh A, Nemich V, Andronova A, Mamedova S (2023) Carbon sequestration dynamics in urban-adjacent forests: a 50-year analysis. Civil Engineering Journal 9(9):2205–2220.

- Vanli ND, Sayin MO, Mohaghegh M, Ozkan H, Kozat SS (2019) Nonlinear regression via incremental decision trees. Pattern Recognition 86:1–13.

- Wofsy SC, Harris RC (2002) The north american carbon program 2002. Tech. rep., The Global Carbon Project, URL https://www.globalcarbonproject.org/global/pdf/thenorthamericancprogram2002.pdf.

- Xiao J, Zhuang Q, Baldocchi DD, Law BE, Richardson AD, Chen J, Oren R, Starr G, Noormets A, Ma S, et al. (2008) Estimation of net ecosystem carbon exchange for the conterminous united states by combining modis and ameriflux data. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 148(11):1827–1847. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Fu B (2023) Impact of china’s establishment of ecological civilization pilot zones on carbon dioxide emissions. Journal of Environmental Management 325:116652.

- Zhao J, Lange H, Meissner H (2022) Estimating carbon sink strength of norway spruce forests using machine learning. Forests 13(10):1721.

- Zhu S, Clement R, McCalmont J, Davies CA, Hill T (2022) Stable gap-filling for longer eddy covariance data gaps: A globally validated machine-learning approach for carbon dioxide, water, and energy fluxes. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 314:108777.

| Variable | Description | Source | Mean | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOY | Day Of Year | AmeriFlux/NEON | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| HOUR | Hour Of Day | AmeriFlux/NEON | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| TS_1_1_1 | Soil Temperature Depth 1 | AmeriFlux/NEON | 12.64 | -29.82 | 56.15 |

| TS_1_2_1 | Soil Temperature Depth 2 | AmeriFlux/NEON | 12.17 | -29.85 | 52.52 |

| PPFD | Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density | AmeriFlux/NEON | 563.72 | -2.27 | 2772.22 |

| TAIR | Air Temperature | AmeriFlux/NEON | 12.14 | -36.39 | 41.85 |

| VPD | Vapor Pressure Deficit | AmeriFlux/NEON | 8.48 | -0.57 | 74.49 |

| SWC_1_1_1 | Soil Water Content | AmeriFlux/NEON | 19.74 | 0.25 | 40.96 |

| PPFD_OUT | Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density, Outgoing | AmeriFlux/NEON | 60.92 | -2.29 | 2054.03 |

| PPFD_BC_IN_1_1_1 | Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density, Below Canopy Incoming | AmeriFlux/NEON | 193.89 | -9.44 | 2638.5 |

| RH | Relative Humidity | AmeriFlux/NEON | 57.03 | 1.35 | 101.95 |

| NETRAD | Net Radiation | AmeriFlux/NEON | 152.55 | -308.42 | 1056.68 |

| USTAR | Friction velocity | AmeriFlux/NEON | 0.46 | 0.05 | 2.78 |

| GCC_50 | Green Chromatic Coordinate, 50th Quantile | Phenocam | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.46 |

| RCC_50 | Red Chromatic Coordinate, 50th Quantile | Phenocam | 0.4 | 0.26 | 0.58 |

| MAT_DAYMET | Mean Annual Temperature | DAYMET | 9.7 | -11.6 | 26.1 |

| MAP_DAYMET | Mean Annual Precipitation | DAYMET | 872.85 | 86 | 2290 |

| PVEG | Primary Vegetation Type | Phenocam | categorical | ||

| SVEG | Secondary Vegetation Type | Phenocam | categorical | ||

| LW_OUT | Longwave Radiation, Outgoing | AmeriFlux/NEON | 378.09 | 165.3 | 694.8 |

| DAILY PRECIPITATION | Daily Precipitation | AmeriFlux/NEON | 2.2 | 0 | 225.19 |

| PRCP1WEEK | Cummulative Precipitation 1 Week | AmeriFlux/NEON | 16.42 | 0 | 262.73 |

| PRCP2WEEK | Cumulative Precipitation 2 Week | AmeriFlux/NEON | 33.59 | 0 | 324.87 |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | MODIS | 0.47 | -0.2 | 0.96 |

| EVI | Enhanced Vegetation Index | MODIS | 0.26 | -0.13 | 0.76 |

| LAT | Latitude | Phenocam | 41.19 | 17.97 | 71.28 |

| LON | Longitude | Phenocam | -101.8 | -156.62 | -66.87 |

| ELEV | Elevation | Phenocam | 813.93 | 7 | 3493 |

| DOMAIN | NEON Field Site Domain | Phenocam | categorical | ||

| organic_C | Total Organic Carbon Stock in Soil Profile | AmeriFlux/NEON | 255.87 | 5 | 1339 |

| total_N | Total Nitrogen Stock in Soil Profile | AmeriFlux/NEON | 13.47 | 0.3 | 43.6 |

| O_thickness | Total Thickness of Organic Horizon | AmeriFlux/NEON | 3.49 | 0 | 110 |

| A_pH | pH of A Horizon | AmeriFlux/NEON | 6.03 | 0 | 8.5 |

| A_sand | Texture of A Horizon (% Sand) | AmeriFlux/NEON | 47.78 | 0 | 97 |

| A_silt | Texture of A Horizon (% Silt) | AmeriFlux/NEON | 32.57 | 0 | 61.9 |

| A_clay | Texture of A Horizon (% Clay) | AmeriFlux/NEON | 15.08 | 0 | 55.3 |

| A_BD | Bulk Density of A Horizon | AmeriFlux/NEON | 0.93 | 0 | 1.59 |

| Linear reg | Stepwise | Decision Tree | Random Forest | XGB | NN 1-layer | NN deeper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 3.49 | 3.58 | 2.39 | 2.26 | 1.81 | 2.06 | 1.91 |

| R2 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.85 |

| Test Set | Site Code | Site Name | Primary Vegtype | Linear reg | Stepwise | Decision Tree | Random Forest | XGB | NN 1-layer | NN deeper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PR-xGU | Guanica Forest (GUAN) | EB | 4.83 | 4.47 | 5.83 | 5.32 | 3.49 | 5.95 | 6.48 |

| 2 | PR-xLA | Lajas Experimental Station (LAJA) | EB | 7.52 | 6.99 | 7.60 | 6.68 | 6.22 | 6.02 | 6.60 |

| 3 | US-xAB | Abby Road (ABBY) | EN | 7.25 | 4.45 | 4.72 | 3.86 | 3.43 | 3.55 | 3.66 |

| 4 | US-xBA | Barrow Environmental Observatory (BARR) | TN | 135.35 | 1.30 | 1.51 | 1.49 | 0.86 | 2.91 | 0.89 |

| 5 | US-xBL | Blandy Experimental Farm (BLAN) | DB | 4.10 | 3.96 | 2.77 | 2.69 | 2.62 | 2.89 | 2.98 |

| 6 | US-xBN | Caribou Creek - Poker Flats Watershed (BONA) | EN | 14.61 | 2.41 | 2.12 | 2.01 | 1.93 | 2.70 | 1.92 |

| 7 | US-xBR | Bartlett Experimental Forest (BART) | DB | 5.21 | 4.41 | 3.33 | 3.06 | 2.77 | 3.13 | 3.06 |

| 8 | US-xCL | LBJ National Grassland (CLBJ) | DB | 5.19 | 4.17 | 4.38 | 4.16 | 3.88 | 4.11 | 3.31 |

| 9 | US-xCP | Central Plains Experimental Range (CPER) | GR | 4.24 | 2.47 | 1.38 | 1.29 | 1.22 | 1.60 | 1.48 |

| 10 | US-xDC | Dakota Coteau Field School (DCFS) | GR | 20.35 | 2.70 | 1.79 | 1.70 | 1.61 | 1.64 | 1.74 |

| 11 | US-xDJ | Delta Junction (DEJU) | EN | 5.52 | 2.28 | 2.05 | 1.64 | 1.44 | 1.56 | 1.44 |

| 12 | US-xDL | Dead Lake (DELA) | DB | 9.86 | 5.29 | 4.36 | 4.21 | 3.84 | 4.23 | 4.26 |

| 13 | US-xDS | Disney Wilderness Preserve (DSNY) | GR | 10.21 | 3.03 | 3.64 | 3.25 | 3.33 | 2.67 | 3.35 |

| 14 | US-xGR | Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Twin Creeks (GRSM) | DB | 6.51 | 6.06 | 4.21 | 3.99 | 3.87 | 4.12 | 3.94 |

| 15 | US-xHA | Harvard Forest (HARV) | DB | 5.24 | 4.50 | 3.05 | 2.91 | 2.60 | 2.73 | 2.92 |

| 16 | US-xHE | Healy (HEAL) | TN | 5.03 | 1.72 | 2.00 | 1.65 | 1.15 | 1.77 | 1.17 |

| 17 | US-xJE | Jones Ecological Research Center (JERC) | DB | 6.07 | 4.37 | 3.75 | 3.46 | 3.19 | 3.43 | 3.41 |

| 18 | US-xJR | Jornada LTER (JORN) | GR | 2.56 | 1.79 | 1.25 | 1.23 | 1.17 | 1.76 | 1.26 |

| 19 | US-xKA | Konza Prairie Biological Station - Relocatable (KONA) | AG | 6.57 | 3.64 | 3.02 | 2.95 | 2.61 | 3.05 | 3.56 |

| 20 | US-xKZ | Konza Prairie Biological Station (KONZ) | GR | 6.88 | 3.57 | 2.60 | 2.23 | 2.21 | 2.06 | 2.16 |

| 21 | US-xLE | Lenoir Landing (LENO) | DB | 6.83 | 5.27 | 4.92 | 4.53 | 4.32 | 4.25 | 4.19 |

| 22 | US-xMB | Moab (MOAB) | GR | 8.63 | 1.86 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 1.54 | 0.68 |

| 23 | US-xNG | Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory (NOGP) | GR | 5.07 | 2.29 | 1.67 | 1.59 | 1.46 | 1.55 | 1.96 |

| 24 | US-xNQ | Onaqui-Ault (ONAQ) | SH | 4.01 | 1.73 | 1.17 | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.90 | 1.21 |

| 25 | US-xNW | Niwot Ridge Mountain Research Station (NIWO) | TN | 9.63 | 1.46 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 1.86 | 1.76 |

| 26 | US-xRM | Rocky Mountain National Park, CASTNET (RMNP) | EN | 8.49 | 3.18 | 2.70 | 2.31 | 1.92 | 2.45 | 1.94 |

| 27 | US-xRN | Oak Ridge National Lab (ORNL) | DB | 5.75 | 5.11 | 4.43 | 4.22 | 3.68 | 3.92 | 3.61 |

| 28 | US-xSB | Ordway-Swisher Biological Station (OSBS) | EN | 7.77 | 3.40 | 3.06 | 2.78 | 2.63 | 3.17 | 3.08 |

| 29 | US-xSC | Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) | DB | 4.53 | 4.11 | 3.36 | 3.00 | 2.86 | 3.12 | 2.98 |

| 30 | US-xSE | Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) | DB | 6.79 | 4.62 | 3.40 | 3.21 | 3.08 | 3.35 | 3.32 |

| 31 | US-xSJ | San Joaquin Experimental Range (SJER) | EN | 5.13 | 4.23 | 3.23 | 3.11 | 3.02 | 3.23 | 3.81 |

| 32 | US-xSL | North Sterling, CO (STER) | AG | 6.10 | 2.40 | 2.00 | 1.93 | 1.83 | 1.90 | 2.08 |

| 33 | US-xSP | Soaproot Saddle (SOAP) | EN | 3.57 | 3.58 | 4.16 | 3.86 | 2.50 | 2.78 | 2.67 |

| 34 | US-xSR | Santa Rita Experimental Range (SRER) | SH | 3.22 | 2.19 | 4.23 | 3.63 | 1.18 | 2.42 | 1.12 |

| 35 | US-xST | Steigerwaldt Land Services (STEI) | DB | 3.96 | 4.06 | 2.44 | 2.10 | 1.91 | 2.34 | 1.78 |

| 36 | US-xTA | Talladega National Forest (TALL) | EN | 5.36 | 5.16 | 4.53 | 4.33 | 3.34 | 3.77 | 3.98 |

| 37 | US-xTE | Lower Teakettle (TEAK) | EN | 6.11 | 3.07 | 2.99 | 2.93 | 2.53 | 2.48 | 2.95 |

| 38 | US-xTL | Toolik (TOOL) | TN | 134.54 | 1.44 | 1.24 | 0.79 | 0.66 | 2.12 | 0.96 |

| 39 | US-xTR | Treehaven (TREE) | DB | 5.13 | 3.89 | 2.41 | 2.35 | 2.12 | 2.61 | 2.21 |

| 40 | US-xUK | The University of Kansas Field Station (UKFS) | DB | 5.16 | 4.12 | 3.20 | 3.06 | 2.92 | 3.56 | 2.92 |

| 41 | US-xUN | University of Notre Dame Environmental Research Center (UNDE) | DB | 3.79 | 3.81 | 2.51 | 2.47 | 2.11 | 2.53 | 1.92 |

| 42 | US-xWD | Woodworth (WOOD) | GR | 5.16 | 2.21 | 1.77 | 1.61 | 1.49 | 1.52 | 1.70 |

| 43 | US-xWR | Wind River Experimental Forest (WREF) | EN | 7.53 | 5.31 | 5.89 | 5.82 | 4.67 | 4.92 | 4.68 |

| 44 | US-xYE | Yellowstone Northern Range (Frog Rock) (YELL) | EN | 5.05 | 2.49 | 2.10 | 2.05 | 1.61 | 1.71 | 1.74 |

| AVERAGE | 12.28 | 3.51 | 3.05 | 2.82 | 2.45 | 2.88 | 2.70 |

| Test Set | Site Code | Site Name | Primary Vegtype | Linear reg | Stepwise | Decision Tree | Random Forest | XGBoost | NN (1-layer) | NN (deep) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PR-xGU | Guanica Forest (GUAN) | EB | 0.07 | 0.21 | -0.35 | -0.12 | 0.52 | -0.40 | -0.67 |

| 2 | PR-xLA | Lajas Experimental Station (LAJA) | EB | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.47 |

| 3 | US-xAB | Abby Road (ABBY) | EN | -0.37 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.65 |

| 4 | US-xBA | Barrow Environmental Observatory (BARR) | TN | -16320.00 | -0.51 | -1.03 | -0.97 | 0.34 | -6.54 | 0.29 |

| 5 | US-xBL | Blandy Experimental Farm (BLAN) | DB | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.76 |

| 6 | US-xBN | Caribou Creek - Poker Flats Watershed (BONA) | EN | -33.28 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.40 | -0.17 | 0.41 |

| 7 | US-xBR | Bartlett Experimental Forest (BART) | DB | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.73 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.77 |

| 8 | US-xCL | LBJ National Grassland (CLBJ) | DB | 0.35 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.74 |

| 9 | US-xCP | Central Plains Experimental Range (CPER) | GR | -4.44 | -0.85 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.22 | 0.33 |

| 10 | US-xDC | Dakota Coteau Field School (DCFS) | GR | -28.15 | 0.49 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.79 |

| 11 | US-xDJ | Delta Junction (DEJU) | EN | -3.89 | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.67 |

| 12 | US-xDL | Dead Lake (DELA) | DB | -0.89 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| 13 | US-xDS | Disney Wilderness Preserve (DSNY) | GR | -3.07 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.72 | 0.56 |

| 14 | US-xGR | Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Twin Creeks (GRSM) | DB | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.78 |

| 15 | US-xHA | Harvard Forest (HARV) | DB | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.79 |

| 16 | US-xHE | Healy (HEAL) | TN | -4.45 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 0.72 | 0.33 | 0.71 |

| 17 | US-xJE | Jones Ecological Research Center (JERC) | DB | 0.19 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.75 |

| 18 | US-xJR | Jornada LTER (JORN) | GR | -2.75 | -0.85 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.21 | -0.77 | 0.09 |

| 19 | US-xKA | Konza Prairie Biological Station - Relocatable (KONA) | AG | -1.33 | 0.28 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.31 |

| 20 | US-xKZ | Konza Prairie Biological Station (KONZ) | GR | -0.85 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.82 |

| 21 | US-xLE | Lenoir Landing (LENO) | DB | 0.19 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.69 |

| 22 | US-xMB | Moab (MOAB) | GR | -145.46 | -5.79 | -0.05 | 0.01 | 0.09 | -3.66 | 0.09 |

| 23 | US-xNG | Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory (NOGP) | GR | -2.17 | 0.36 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.52 |

| 24 | US-xNQ | Onaqui-Ault (ONAQ) | SH | -7.30 | -0.54 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.43 | -0.87 | 0.25 |

| 25 | US-xNW | Niwot Ridge Mountain Research Station (NIWO) | TN | -120.13 | -1.77 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.28 | -3.53 | -3.04 |

| 26 | US-xRM | Rocky Mountain National Park, CASTNET (RMNP) | EN | -5.45 | 0.09 | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.67 | 0.46 | 0.66 |

| 27 | US-xRN | Oak Ridge National Lab (ORNL) | DB | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.71 |

| 28 | US-xSB | Ordway-Swisher Biological Station (OSBS) | EN | -1.39 | 0.54 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.62 |

| 29 | US-xSC | Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) | DB | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.75 |

| 30 | US-xSE | Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) | DB | -0.01 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.76 |

| 31 | US-xSJ | San Joaquin Experimental Range (SJER) | EN | -0.51 | -0.03 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.17 |

| 32 | US-xSL | North Sterling, CO (STER) | AG | -4.83 | 0.10 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.32 |

| 33 | US-xSP | Soaproot Saddle (SOAP) | EN | -0.98 | -0.98 | -1.68 | -1.31 | 0.03 | -0.19 | -0.10 |

| 34 | US-xSR | Santa Rita Experimental Range (SRER) | SH | -7.73 | -3.04 | -14.04 | -10.11 | -0.18 | -3.93 | -0.06 |

| 35 | US-xST | Steigerwaldt Land Services (STEI) | DB | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.90 |

| 36 | US-xTA | Talladega National Forest (TALL) | EN | 0.39 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.66 |

| 37 | US-xTE | Lower Teakettle (TEAK) | EN | -2.27 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.24 |

| 38 | US-xTL | Toolik (TOOL) | TN | -12181.30 | -0.40 | -0.03 | 0.58 | 0.71 | -2.01 | 0.38 |

| 39 | US-xTR | Treehaven (TREE) | DB | 0.24 | 0.57 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.86 |

| 40 | US-xUK | The University of Kansas Field Station (UKFS) | DB | 0.24 | 0.52 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.76 |

| 41 | US-xUN | University of Notre Dame Environmental Research Center (UNDE) | DB | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.89 |

| 42 | US-xWD | Woodworth (WOOD) | GR | -2.01 | 0.45 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.67 |

| 43 | US-xWR | Wind River Experimental Forest (WREF) | EN | -0.65 | 0.18 | -0.01 | 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.36 |

| 44 | US-xYE | Yellowstone Northern Range (Frog Rock) (YELL) | EN | -2.28 | 0.20 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.62 | 0.61 |

| AVERAGE | -656.42 | -0.02 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.60 | -0.01 | 0.44 |

| Primary Vegetation | Site | Mean Bias | R |

|---|---|---|---|

| AG | US-xSL | -15.80 | 0.58 |

| US-xKA | 4.73 | 0.22 | |

| AVERAGE | -5.53 ± 10.27 | 0.40 ± 0.18 | |

| DB | US-xSC | -60.82 | |

| US-xLE | 134.12 | ||

| US-xJE | 76.42 | 0.68 | |

| US-xHA | -46.71 | 0.32 | |

| US-xGR | 20.46 | 0.05 | |

| US-xRN | -67.14 | 0.82 | |

| US-xDL | 55.57 | -0.56 | |

| US-xST | 21.37 | 0.75 | |

| US-xSE | 17.43 | -0.36 | |

| US-xCL | 170.94 | -0.78 | |

| US-xBR | 114.38 | 0.85 | |

| US-xTR | -3.15 | 0.96 | |

| US-xBL | 135.44 | 0.019 | |

| US-xUK | 1.47 | 0.98 | |

| US-xUN | 4.95 | -0.44 | |

| AVERAGE | 38.32 ± 71.72 | 0.25 ± 0.64 | |

| EB | PR-xLA | 140.70 | |

| PR-xGU | 31.93 | ||

| AVERAGE | 86.32 ± 54.38 | ||

| EN | US-xSB | 121.02 | -0.20 |

| US-xSP | -44.92 | 0.48 | |

| US-xTA | -68.90 | 0.32 | |

| US-xTE | 47.40 | -0.35 | |

| US-xSJ | -15.44 | -0.65 | |

| US-xRM | -48.55 | -0.67 | |

| US-xYE | 4.31 | 0.57 | |

| US-xDJ | 20.68 | 0.24 | |

| US-xWR | -10.31 | -0.92 | |

| US-xAB | 52.29 | 0.09 | |

| US-xBN | -18.25 | 0.55 | |

| AVERAGE | 3.57 ± 51.99 | -0.05 ± 0.51 | |

| GR | US-xWD | -5.97 | 0.62 |

| US-xCP | -9.58 | 0.52 | |

| US-xDC | 21.99 | 0.88 | |

| US-xMB | 17.88 | 0.98 | |

| US-xDS | 230.26 | -0.90 | |

| US-xJR | 28.82 | 0.63 | |

| US-xKZ | 19.34 | -0.62 | |

| US-xNG | 34.74 | 0.85 | |

| AVERAGE | 42.18 ± 72.57 | 0.37 ± 0.67 | |

| SH | US-xSR | -61.37 | 0.99 |

| US-xNQ | 63.5 | 0.99 | |

| AVERAGE | 1.07 ± 62.44 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | |

| TN | US-xNW | -28.12 | 0.95 |

| US-xHE | -12.39 | 0.76 | |

| US-xTL | -22.12 | 0.54 | |

| US-xBA | -29.72 | 0.81 | |

| AVERAGE | -23.09 ± 6.80 | 0.77 ± 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).