Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Drug-Induced Cardiovascular Damage

Justification of the Study

- To explore the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying drug-induced cardiovascular damage, with a focus on autonomic regulation, oxidative stress, and inflammatory pathways.

- To review the existing clinical evidence, including randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses, to assess the cardiovascular impact of substance use invulnerable populations such as young individuals and those with pre-existing cardiovascular comorbidities.

- To propose clinical and public health strategies for the prevention, diagnosis, and management of substance-related cardiovascular diseases, addressing risks associated with both legal and illicit drugs.

- To identify critical gaps in current research and suggest future directions, with particular attention to the chronic cardiovascular effects of prolonged substance use.

Research Objectives and PICO Questions

- Impact of illicit drugs on cardiovascular health: What are the effects of illicit drug use, such as cocaine, methamphetamines, and cannabis, on the incidence of severe cardiovascular events (e.g., myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, ¿heart failure) compared to non-users?

- Cardiovascular effects of legal substance use (tobacco and alcohol): How does chronic use of legal substances like tobacco and alcohol influence the development of cardiovascular diseases (e.g., hypertension, atherosclerosis, arrhythmias) compared to non-users?

- Pathophysiological mechanisms of drug-induced cardiovascular damage: What pathophysiological mechanisms—such as autonomic dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation, ¿and endothelial damage—are implicated in drug-induced cardiovascular damage?

- Cardiovascular risks of novel psychoactive substances: How do the risks of acute cardiovascular events, such as hypertension, arrhythmias, and cardiac diseases, ¿among users of novel psychoactive substances compare to those of traditional drug users?

2. Materials and Methods

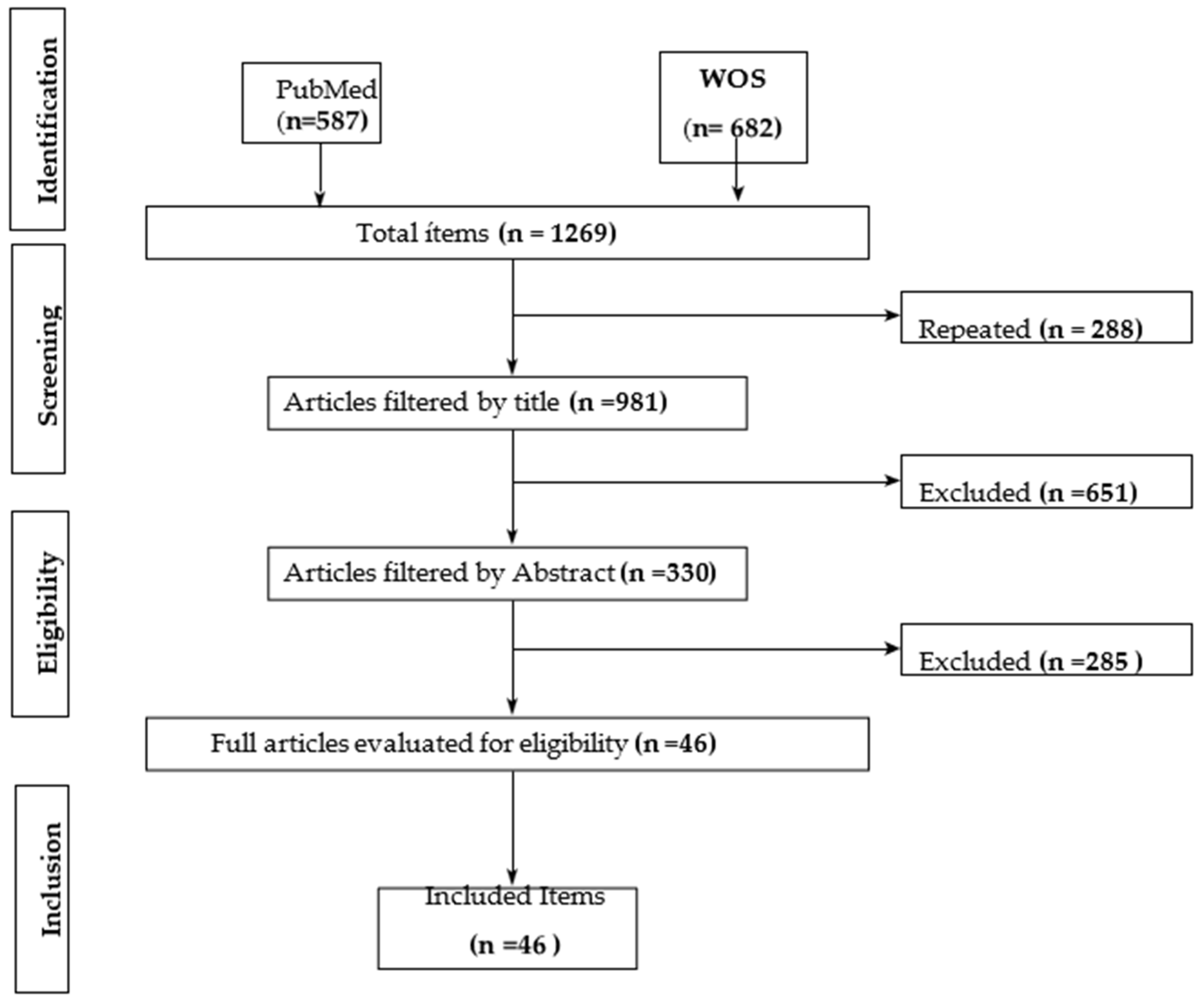

Search Strategy

Inclusion Criteria

- -

- Studies with high methodological standards, such as randomized clinical trials (RCTs), systematic reviews, and meta-analyses, will be included.

- -

- Publications must be indexed in high-quality databases, such as PubMed or Web of Science, and have been published within the last five years.

- -

- Population: Studies involving adolescents and adults over 15 years of age who consume psychoactive substances, both legal (tobacco and alcohol) and illegal (cocaine, methamphetamines, cannabis, opioids, among others), as well as psychotropic medications used therapeutically or recreationally. Individuals with and without pre-existing cardiovascular diseases will be included.

- -

- Interventions: Research that explores the direct and indirect effects of psychoactive substances on cardiovascular health, evaluating parameters such as hypertension, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, acute coronary syndromes and atherosclerosis. Studies that focus on pathophysiological mechanisms such as oxidative stress, vascular inflammation and autonomic dysfunction will also be addressed.

- -

- Results: Adverse cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke) and Biomarkers of cardiovascular risk (blood pressure, heart rate, inflammatory markers, endothelial dysfunction).

Exclusion Criteria

- -

- Only articles published in English or Spanish will be considered to ensure the quality and accessibility of the results.

- -

- Non-systematic reviews, editorials, letters to the editor, conference abstracts and theses will be excluded.

- -

- Duplicate studies or without access to the full text.

- -

- In terms of population, studies focused exclusively on pediatric (<15 years) or geriatric (>80 years) populations without specific cardiovascular outcomes are excluded.

- -

- Preclinical research (animal models) and non-human studies.

- -

- Studies that look at the effects of substances without a clear focus on cardiovascular outcomes.

- -

- Research limited to neuropsychiatric or cognitive effects with no cardiovascular relevance.

- -

- Articles in languages other than English or Spanish.

- -

- Studies published outside the last five-year period.

3. Results

| Author | Year | Design | N | Age | Control group | Experimental group | Substance | Measurement scale | Results |

| Adkins-Hempel et al. | 2023 | Randomized controlled trial | 324 | 18-75 years | Yes | Yes | Tobacco | Fagerström, measures of anxiety | Significant reduction in tobacco use |

| Al Ali et al. | 2020 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 31 studies with N= 38,037 | Adults | No | No | Water pipe | Cardiovascular parameters | Increased systolic blood pressure |

| Aminuddin et al. | 2023 | Systematic review | 7 | Seniors | No | No | Tobacco | Unstable Plate Analysis | Association between smoking and unstable plaques |

| Anadani et al. | 2023 | Post-hoc analysis | 2874 | 18-85 years old | Yes | Yes | Tobacco | Behavioral changes | Smoking after an acute ischemic stroke raises the risk of cardiovascular events and mortality compared to non-smokers. |

| Bagherpour-Kalo et al. | 2024 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2759 | Adults | No | No | Water pipe | Incidence of stroke | Increased prevalence of associated stroke |

| Benowitz & Liakoni | 2022 | Narrative Review | - | Adults | No | No | Tobacco | CV Risk Factors | Description of the impact of tobacco on cardiovascular health |

| Bhanu et al. | 2021 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 27079 | Seniors | yes | yes | Blood pressure medications | Frequency of orthostatic hypotension | Significant relationship between medication use and hypotension events |

| Carr et al. | 2024 | Systematic review | 4826 | Adults | No | No | Alcohol | IHD Measurements | Association between alcohol consumption and ECI |

| Cecchini et al. | 2024 | Systematic review | 600 000 | Seniors | yes | yes | Alcohol | Blood pressure. Dose-response analysis | Increased risk of hypertension with higher levels of consumption |

| Chen et al. | 2020 | Systematic review | 37 290 | Seniors | yes | yes | Alcohol | Incidence of retinopathy. Microvascular abnormalities | Increased risk of diabetic retinopathy |

| Cortés et al. | 2019 | Narrative Review | - | Adults | No | No | Cocaine | Cardiovascular effects | Relationship between cocaine use and CV complications |

| Crotty et al. | 2020 | Updating Guides | 67 posts | Seniors | No | No | Opioids | ASAM Guide | Summary of Opioid Disorder Treatment Recommendations |

| DeFilippis et al. | 2020 | Narrative Review | - | Seniors | No | No | Marijuana | Cardiovascular risk | Potential risks in patients with cardiovascular disease |

| Di Federico et al. | 2023 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 19,548 participants | Adults | No | No | Alcohol | Blood pressure | Association between alcohol consumption and blood pressure levels |

| Ding et al. | 2021 | Systematic review | 14,386 patients | Seniors | No | No | Alcohol | CV morbidity/mortality | Increased risk of morbidity/mortality with alcohol consumption |

| Florez-Perdomo et al. | 2024 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2227 cocaine users | Adults | No | No | Cocaine | Incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage | Association between cocaine use and increased risk of bleeding |

| George et al. | 2019 | Randomized controlled trial | 114 | Adults | Tobacco cigarette users (TC) | E-cigarettes (with nicotine and nicotine-free) | Nicotine | Flow-mediated dilation (FMD), pulse wave velocity (PWV) | Significant improvement in vascular endothelial function after switching from TC to EC. Females showed greater improvement than males. |

| Krantz et al. | 2021 | Narrative Review | - | Seniors | No | No | Opioids | Cardiovascular complications | Analysis of cardiovascular complications in opioid users |

| Latif & Garg | 2020 | Review | Youth and Adults | No | No | cannabis | Cardiovascular complications | Cardiovascular effects such as thrombosis, inflammation, atherosclerosis, heart attack, arrhythmias, and strokes | |

| Mena et al. | 2020 | Narrative Review | - | Adults | No | No | Cannabis | Cardiovascular health | Impact of cannabis use on cardiovascular health |

| Page et al. | 2020 | Revision | - | Youth and adults | No | No | cannabis | Analysis of cardiovascular effects based on observational data and previous studies | cardiovascular events: myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathies, strokes and arteritis, |

| Patel et al. | 2020 | Systematic review | 12 | Adults | No | No | Marijuana | Acute myocardial infarction | Relationship between marijuana use and heart attack risk |

| Jalali et al. | 2021 | Narrative Review | - | Adults | No | No | Tobacco, Alcohol, Opioids | Coronary microcirculation | Negative impact on microcirculation related to substance use |

| Gagnon et al. | 2022 | Narrative Review | - | Adults | No | No | Common drugs of abuse | Toxicology and management | Heart complications from drug abuse |

| Morovatdar et al. | 2021 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 1334 | Adults | No | No | Water pipe | Risk of coronary heart disease | Increased risk of coronary heart disease associated with waterpipe use |

| Lang et al. | 2023 | Secondary analysis | 4877 participants | Adults | Yes | Yes | Tobacco | Risk of stroke | Increased risk of stroke with smoking |

| Fernández-Solà et al. | 2020 | Review | - | Seniors | No | No | Alcohol | Cardiovascular effects | Alcoholic-dilated cardiomyopathy progresses with ethanol intake, but abstinence or reduction improves outcomes. |

| Mancone et al. | 2024 | Randomized trial | 3445 patients | Adults | Yes | Yes | Tobacco | Coronary heart disease | Impact of smoking on suspected coronary heart disease |

| Gadelha et al. | 2022 | Expert Opinion / Narrative Review | - | Adults | No | No | Opioids | Not applicable since the study does not conduct any measurements. | Impact of opioids on endocrine function including hypogonadism, adrenal dysfunction, and hyperprolactinemia. |

| Kharel et al. | 2023 | Systematic review | 75 cases | Adults | No | No | Altitude | Cerebral venous thrombosis | Association between high-altitude exposure and thrombosis in smokers and alcohol consumption |

| Kevil et al. | 2019 | Narrative Review | - | Adults | No | No | Methamphetamine | Cardiovascular disease | Impact of methamphetamine use on cardiovascular risk |

| Karavitaki et al. | 2024 | Scientific statement | - | Seniors | No | No | Opioids | Endocrine system | Scientific opinions on the effects of opioids |

| Schupper et al. | 2023 | Randomized Clinical Trial | 800 | Adults | Yes | Yes | Tobacco | Expansion of the hematoma | Increased risk of bleeding with tobacco use |

| Gupta et al. | 2018 | Systematic review | 50 studies | Adults | No | No | Smokeless tobacco | Cardiovascular disease | Significant Association Between Smokeless Tobacco Use and Cardiovascular Disease |

| Singh et al. | 2018 | Literature review | 135 studies | Adults | No | No | Marijuana | Cardiovascular complications | Relationship between marijuana and cardiovascular complications |

| Mladěnka et al. | 2018 | Comprehensive review | 18 | Adults | No | No | Drugs of abuse | Cardiovascular toxicity | Review of the toxicity of different substances of abuse |

| Mwebe & Roberts | 2019 | Narrative Review | - | Adults with serious mental illness | No | No | Psychotropic medication | Cardiovascular risk | Increased cardiovascular risk associated with the use of psychotropic drugs |

| Pasha et al. | 2021 | Systematic Review |

Adults | No | No | Medical Marijuana |

Cardiovascular Effects of Medical Marijuana |

Marijuana is associated with its own set of cardiovascular risks | |

| Piña et al. | 2018 | Narrative Review | - | Seniors | No | No | Psychopharmacology | Cardiovascular health | Impact of psychiatric drugs on cardiovascular health |

| Larsson et al. | 2020 | Mendelian randomization | - | Adults (primarily European) | SI | Alcohol | Odds ratios calculated using genetic variants (SNPs) and statistical methods (MR-Egger, MR-PRESSO, etc.) | Alcohol consumption causally associated with increased risk of peripheral artery disease and stroke. Weaker associations observed for other CVDs. | |

| Toska & Mayrovitz | 2023 | Narrative Review | 50 studies | Adults | No | No | Opioids | Cardiovascular health | Negative impacts of opioids on cardiovascular health |

| Topçu et al. | 2019 | Case Report | 1 | Young 18 years old | No | No | Synthetic cannabis | electrocardiogram (ECG) and atrial fibrillation | Osborn wave and atrial fibrillation detected |

| La Rosa et al. | 2023 | Clinical Review | 25 studies | Adults | No | No | E-cigarettes | Salud cardiovascular | Effects of e-cigarette substitution on CV health |

| Siagian et al. | 2023 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 7042 | Young women | No | No | Risk factors | Acute coronary syndrome | Identification of risk factors in young women |

| Zhang et al. | 2020 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 55 studies | Secondhand smoke | No | No | Secondhand smoke | Cardiovascular disease | Dose-response effect of secondhand smoke on cardiovascular health |

| Zhao, J. et al. | 2021 | Mendelian randomization study | 32,330 (exposure); | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Cannabis use | Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with cannabis use; GWAS data on cardiovascular diseases | No causal effects. Significant associations with small-vessel stroke and AF after adjustments. |

4. Discussion

Justification for the Analytical Categories

- Impact of different drugs on cardiovascular risk factors.

- 2.

- Association between drug use and specific cardiovascular diseases.

3. Differences in Cardiovascular Impact According to the Type of Drug

4. Effects of Chronic vs. Acute Drug Use on the Cardiovascular System

5. Biological and Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Drug Use in Cardiovascular Health

Cocaine and Cardiovascular Health

Cannabis and Cardiovascular Health

Tobacco and Cardiovascular Health

Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health

Opioids and Cardiovascular Health

Other Drugs and Cardiovascular Health

5. Conclusions

- How do chronic exposures to novel psychoactive substances, such as synthetic cannabinoids or designer stimulants, influence cardiovascular health over time in diverse demographic cohorts?

- What are the sex-specific and age-specific cardiovascular risks associated with the concurrent use of multiple psychoactive substances?

- Can specific inflammatory biomarkers or genetic predispositions predict cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with a history of psychoactive substance use?

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2020. Booklet 2—Drug use and health consequences. 2020. Available at: https://wdr.unodc.org/wdr2020/field/WDR20_Booklet_2.pdf.

- Mladěnka P, Applová L, Patočka J, Costa VM, Remiao F, Pourová J, et al. Comprehensive review of cardiovascular toxicity of drugs and related agents. Med Res Rev. 2018;38(4):1332-1403. [CrossRef]

- Kevil CG, Goeders NE, Woolard MD, Bhuiyan MS, Dominic P, Traylor J, et al. Methamphetamine use and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review of the literature and implications for treatment. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2019;19(6):543-558. [CrossRef]

- Gagnon LR, Sadasivan C, Perera K, Oudit GY. Cardiac complications of common drugs of abuse: pharmacology, toxicology, and management. Can J Cardiol. 2022;38(9):1331-1341. [CrossRef]

- Phillips K, Luk A, Soor GS, Butany J. Cocaine and cardiovascular health: A comprehensive review. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73(6):347-355. [CrossRef]

- Florez-Perdomo W, Reyes Bello J, García-Ballestas E, Moscote-Salazar L, Barthélemy E, Janjua T, et al. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and cocaine consumption: A systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2024;184:241-252.e2. [CrossRef]

- Krantz MJ, Palmer RB, Haigney MC. Cardiovascular complications of opioid use: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(2):205-223. [CrossRef]

- Toska E, Mayrovitz HN. Opioid impacts on cardiovascular health. Cureus. 2023;15(9). [CrossRef]

- Fountas A, Chai ST, Kourkouti C, Karavitaki N. Mechanisms of endocrinology: endocrinology of opioids. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;179(4):R183-R196. [CrossRef]

- Latif Z, Garg N. The impact of marijuana on the cardiovascular system: a review of the most common cardiovascular events associated with marijuana use. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1925. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Saluja S, Kumar A, Agrawal S, Thind M, Nanda S, et al. Cardiovascular complications of marijuana and related substances: a review. Cardiol Ther. 2018;7(1):45-59. [CrossRef]

- Pacher P, Kunos G. Acute and chronic effects of cannabis on cardiovascular health: A review. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2021;26(4):293-302. [CrossRef]

- Mena LJ, Felix VG, Ostos R, González JG, Maestre GE. Impact of cannabis consumption on cardiovascular health: A review. Int J Cardiol. 2020;310:170-175. [CrossRef]

- Zhang D, Liu Y, Cheng C, Wang Y, Xue Y, Li W, et al. Dose-related effect of secondhand smoke on cardiovascular disease in nonsmokers: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2020;228:113546. [CrossRef]

- Benowitz NL, Liakoni E. Tobacco use disorder and cardiovascular health. Addiction. 2022;117(4):1128-1138. [CrossRef]

- Gupta R, Gupta S, Sharma S, Sinha DN, Mehrotra R. A systematic review on association between smokeless tobacco & cardiovascular diseases. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148(1):77-89. [CrossRef]

- Lang AE, de Havenon A, Mac Grory B, Henninger N, Shu L, Furie KL, et al. Subsequent ischemic stroke and tobacco smoking: A secondary analysis of the POINT trial. Eur Stroke J. 2023;8(1):328-333. [CrossRef]

- Cecchini M, Filippini T, Whelton P, Iamandii I, Di Federico S, Boriani G, et al. Alcohol intake and risk of hypertension: A systematic review and dose-response analysis. Hypertension. 2024;81(8):1701-15. [CrossRef]

- Ronksley PE, Brien SE, Turner BJ, Mukamal KJ, Ghali WA. Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d671. [CrossRef]

- Ding C, O’Neill D, Bell S, Stamatakis E, Britton A. Alcohol consumption and morbidity/mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):167. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Solà J. The effects of ethanol on the heart: alcoholic cardiomyopathy. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):572. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Zhang K, Zhong C, Zhu Z, Zheng X, Yang P, et al. Alcohol drinking modified the effect of plasma YKL-40 levels on stroke-specific mortality of acute ischemic stroke. Neuroscience. 2024;552:152-158. [CrossRef]

- Piña IL, Di Palo KE, Ventura HO. Psychopharmacology and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(20):2346-2359. [CrossRef]

- Mwebe H, Roberts D. Risk of cardiovascular disease in people taking psychotropic medication: a literature review. Br J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;8(3):136-144. [CrossRef]

- Pasha AK, Clements CY, Reynolds CA, Lopez MK, Lugo CA, Gonzalez Y, Shirazi FM, Abidov A. Cardiovascular effects of medical marijuana: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2021;134(2):182-193. [CrossRef]

- Al Ali R, Vukadinović D, Maziak W, Katmeh L, Schwarz V, Mahfoud F, et al. Cardiovascular effects of waterpipe smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020;21(3):453-468. [CrossRef]

- Karavitaki N, Bettinger JJ, Biermasz N, Christ-Crain M, Gadelha MR, Inder WJ, et al. Exogenous opioids and the human endocrine system: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr Rev. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP23-07-01-006, NSDUH Series H-58). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2023. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2022-nsduh-annual-national-report.

- Rossboth S, Lechleitner M, Oberaigner W. Risk factors for diabetic foot complications in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2021;4(1):e00175. [CrossRef]

- Siebenhofer A, Winterholer S, Jeitler K, Horvath K, Berghold A, Krenn C, et al. Long-term effects of weight-reducing drugs in people with hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;1(1):CD007654. [CrossRef]

- Siagian SN, Christianto C, Angellia P, Holiyono HI. The risk factors of acute coronary syndrome in young women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2023;19(3):37-49. [CrossRef]

- Bhanu C, Nimmons D, Petersen I, Orlu M, Davis D, Hussain H, et al. Drug-induced orthostatic hypotension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021;18(11):e1003821. [CrossRef]

- Di Federico S, Filippini T, Whelton P, Cecchini M, Iamandii I, Boriani G, et al. Alcohol intake and blood pressure levels: A dose-response meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2023;80(10):1961-1969. [CrossRef]

- Liampas I, Raptopoulou M, Siokas V, Bakirtzis C, Tsouris Z, Aloizou A, et al. Conventional cardiovascular risk factors in transient global amnesia: Systematic review. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2021;61:100909. [CrossRef]

- Ye J, Liu C, Deng Z, Zhu Y, Zhang S. Risk factors associated with contrast-associated acute kidney injury. BMJ Open. 2023;13(6):e070561. [CrossRef]

- Crotty K, Freedman KI, Kampman KM. Executive summary of the focused update of the ASAM national practice guideline for the treatment of opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2):99-112.

- Kharel S, Shrestha S, Pant S, Acharya A, Sharma A, Baniya S, et al. High-altitude exposure and cerebral venous thrombosis: An updated systematic review. High Alt Med Biol. 2023;24(3):167-74. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Jia Y, Zhang Q, Du Y, He Y, Zheng A. Incidence and risk factors for postoperative venous thromboembolism in patients with gynecological malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;160(2):610-8. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Saluja S, Kumar A, Agrawal S, Thind M, Nanda S, et al. Cardiovascular complications of marijuana and related substances: a review. Cardiol Ther. 2018;7(1):45-59. [CrossRef]

- Jeffers AM, Glantz S, Byers AL, Keyhani S. Association of Cannabis Use with Cardiovascular outcomes among US adults. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13(5):e030178. [CrossRef]

- Feng Y, Bai X, Zhang X, Wang T, Lu X, Yang K, et al. Risk factors for new ischemic cerebral lesions after carotid artery stenting. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;77:296-305. [CrossRef]

- Rehman S, Sahle B, Chandra R, Dwyer M, Thrift A, Callisaya M, et al. Sex differences in risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol Sci. 2019;406:116446. [CrossRef]

- Lang AE, de Havenon A, Mac Grory B, Henninger N, Shu L, Furie KL, et al. Subsequent ischemic stroke and tobacco smoking: A secondary analysis of the POINT trial. Eur Stroke J. 2023; 8(1):328-333. [CrossRef]

- Stein JH, Smith SS, Hansen KM, Korcarz CE, Piper ME, Fiore MC, et al. Longitudinal effects of smoking cessation on carotid artery atherosclerosis in contemporary smokers: The Wisconsin Smokers Health Study. Atherosclerosis. 2020;315:62-67. [CrossRef]

- Parada-Ricart E, Luque V, Zaragoza M, Ferre N, Closa-Monasterolo R, Koletzko B, et al. Effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on child blood pressure in a European cohort. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):17308. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy C, McAteer C, Murphy R, McDermott C, Costello M, O’Donnell M. Behavioral sleep interventions and cardiovascular risk factors: Systematic review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2024;39(5):E158-E171. [CrossRef]

- Howard D, Gaziano L, Rothwell P. Risk of stroke in relation to asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(3):193-202. [CrossRef]

- Li B, Li D, Liu J, Wang L, Yan X, Liu W, et al. “Smoking paradox” is not true in patients with ischemic stroke: A systematic review. J Neurol. 2021;268(6):2042-2054. [CrossRef]

- Bagherpour-Kalo M, Jones M, Darabi P, Hosseini M. Water pipe smoking and stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2024;14(1):e3357. [CrossRef]

- Aminuddin A, Cheong S, Roos N, Ugusman A. Smoking and unstable plaque in acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review. Int J Med Sci. 2023;20(4):482-492. [CrossRef]

- Al Ali R, Vukadinović D, Maziak W, Katmeh L, Schwarz V, Mahfoud F, et al. Cardiovascular effects of waterpipe smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020;21(3):453-468. [CrossRef]

- Kevil CG, Goeders NE, Woolard MD, Bhuiyan MS, Dominic P, Traylor J, et al. Methamphetamine use and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review of the literature and implications for treatment. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2019;19(6):543-558. [CrossRef]

- Patel R, Kamil S, Bachu R, Adikey A, Ravat V, Kaur M, et al. Marijuana use and acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2020;30(5):298-307. [CrossRef]

- Richards T. Mechanisms linking cannabinoid use to arrhythmias and coronary artery disease. J Cardiol. 2020;35(4):678-688.

- Anderer A. Cannabis use and cardiovascular risks: Evidence from population-based studies. Int J Cardiol. 2024;35(7):205-211. [CrossRef]

- Shelton SK, Herrmann ES, Ahmed M, Van Amburgh C, Moser S, Bashaw H, et al. Why do patients come to the emergency department after using cannabis? J Emerg Med. 2019;57(5):611-618. [CrossRef]

- Krantz MJ, Palmer RB, Haigney MC. Cardiovascular complications of opioid use: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(2):205-223.

- Florez-Perdomo W, Reyes Bello J, García-Ballestas E, Moscote-Salazar L, Barthélemy E, Janjua T, et al. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and cocaine consumption: A systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2024;184:241-252.e2. [CrossRef]

- Adkins-Hempel M, Japuntich SJ, Chrastek M, Dunsiger S, Breault CE, Ayenew W, et al. Integrated smoking cessation and mood management following acute coronary syndrome: Protocol for the post-acute cardiac event smoking (PACES) trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2023;18(1):29. [CrossRef]

- Sun L, Song L, Yang J, Lindley RI, Robinson T, Lavados PM, et al. Smoking influences outcome in patients who had thrombolysed ischemic stroke: The ENCHANTED study. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2021;6(3):395-401. [CrossRef]

- Jalali Z, Khademalhosseini M, Soltani N, Esmaeili Nadimi A. Smoking, alcohol, and opioids effect on coronary microcirculation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21(1):185. [CrossRef]

- Morovatdar N, Poorzand H, Bondarsahebi Y, Hozhabrossadati SA, Montazeri S, Sahebkar A. Water pipe tobacco smoking and risk of coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2021;14(6):986-992. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Zhang K, Zhong C, Zhu Z, Zheng X, Yang P, et al. Alcohol drinking modified the effect of plasma YKL-40 levels on stroke-specific mortality of acute ischemic stroke. Neuroscience. 2024;552:152-158. [CrossRef]

- La Rosa G, Vernooij R, Qureshi M, et al. Clinical testing of the cardiovascular effects of e-cigarette substitution for smoking: a living systematic review. Intern Emerg Med. 2023;18:917-928. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Li Y, Liu M, Gu H, Zhao F, Yang Y, et al. Acute effects of smoking on plaque instability in patients with coronary heart disease. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43(9):1050-1058. [CrossRef]

- Carr S, Bryazka D, McLaughlin S, Zheng P, Bahadursingh S, Aravkin A, et al. Alcohol consumption and ischemic heart disease: A systematic review. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):4082. [CrossRef]

- Pacher P, Kunos G. Acute and chronic effects of cannabis on cardiovascular health: A review. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2021;26(4):293-302. [CrossRef]

- Holt E, Phillips P, Grant A. Chronic pain management and cardiovascular risks in cannabis users: A retrospective analysis. Pain Manag. 2024;10(5):123-134. [CrossRef]

- Topçu H, Aksan G, Karakuş Yılmaz B, Tezcan M, Sığırcı S. Osborn wave and new-onset atrial fibrillation related to hypothermia after synthetic cannabis (bonsai) abuse. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2019;47(4):315-318. [CrossRef]

- Phillips K, Luk A, Soor GS, Butany J. Cocaine and cardiovascular health: A comprehensive review. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73(6):347-355. [CrossRef]

- Cortés FC, Ribas PFG, Campos JVQ. Cardiovascular effects in cocaine users. Rev Med Sinerg. 2019;4(5):5-14. [CrossRef]

- Patel RS, Kuntz T, Patel A. Cardiovascular effects of marijuana and synthetic cannabinoids: The good, the bad, and the ugly. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(2):202-210. [CrossRef]

- Florez-Perdomo W, Reyes Bello J, García-Ballestas E, Moscote-Salazar L, Barthélemy E, Janjua T, et al. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and cocaine consumption: A systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2024;184:241-252.e2. [CrossRef]

- Pacher P, Kunos G. Acute and chronic effects of cannabis on cardiovascular health: A review. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2021;26(4):293-302. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Chen H, Zhuo C, Xia S. Cannabis use and the risk of cardiovascular diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:676850. [CrossRef]

- Zongo S, N’Diaye MM, Gaye S, Diallo AI. Cannabis use and cardiovascular outcomes in Africa: A systematic review. Afr J Cardiol. 2021;33(2):45-57. [CrossRef]

- Mancone M, Mézquita AJV, Birtolo LI, Maurovich-Horvat P, Kofoed KF, Benedek T, et al. Impact of smoking in patients with suspected coronary artery disease in the randomized DISCHARGE trial. Eur Radiol. 2024; 34(6):4127-4141. [CrossRef]

- Karavitaki N, Bettinger JJ, Biermasz N, Christ-Crain M, Gadelha MR, Inder WJ, et al. Exogenous opioids and the human endocrine system: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr Rev. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shechter M, Melamed N, Nitzan U, Abiri S, Amsalem Y, Zafrir B, et al. Heart rate variability in chronic opioid users: A prospective observational study. J Cardiol. 2022;34(6):1123-1132. [CrossRef]

- Loomba R, Valls J, Suri G. Hyperadrenergic states during opioid withdrawal: Cardiovascular implications. J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;12(3):155-163. [CrossRef]

- La Rosa G, Vernooij R, Qureshi M, et al. Clinical testing of the cardiovascular effects of e-cigarette substitution for smoking: A living systematic review. Intern Emerg Med. 2023;18:917–928. [CrossRef]

- George J, Hussain M, Vadiveloo T, Ireland S, Hopkinson P, Struthers AD, Donnan PT, Khan F, Lang CC. Cardiovascular Effects of Switching From Tobacco Cigarettes to Electronic Cigarettes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Dec 24;74(25):3112-3120. Epub 2019 Nov 15. PMID: 31740017; PMCID: PMC6928567. [CrossRef]

- Larsson SC, Burgess S, Mason AM, Michaëlsson K. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease: A Mendelian randomization study. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020;13:e002814. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).