Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Microfluidic chip

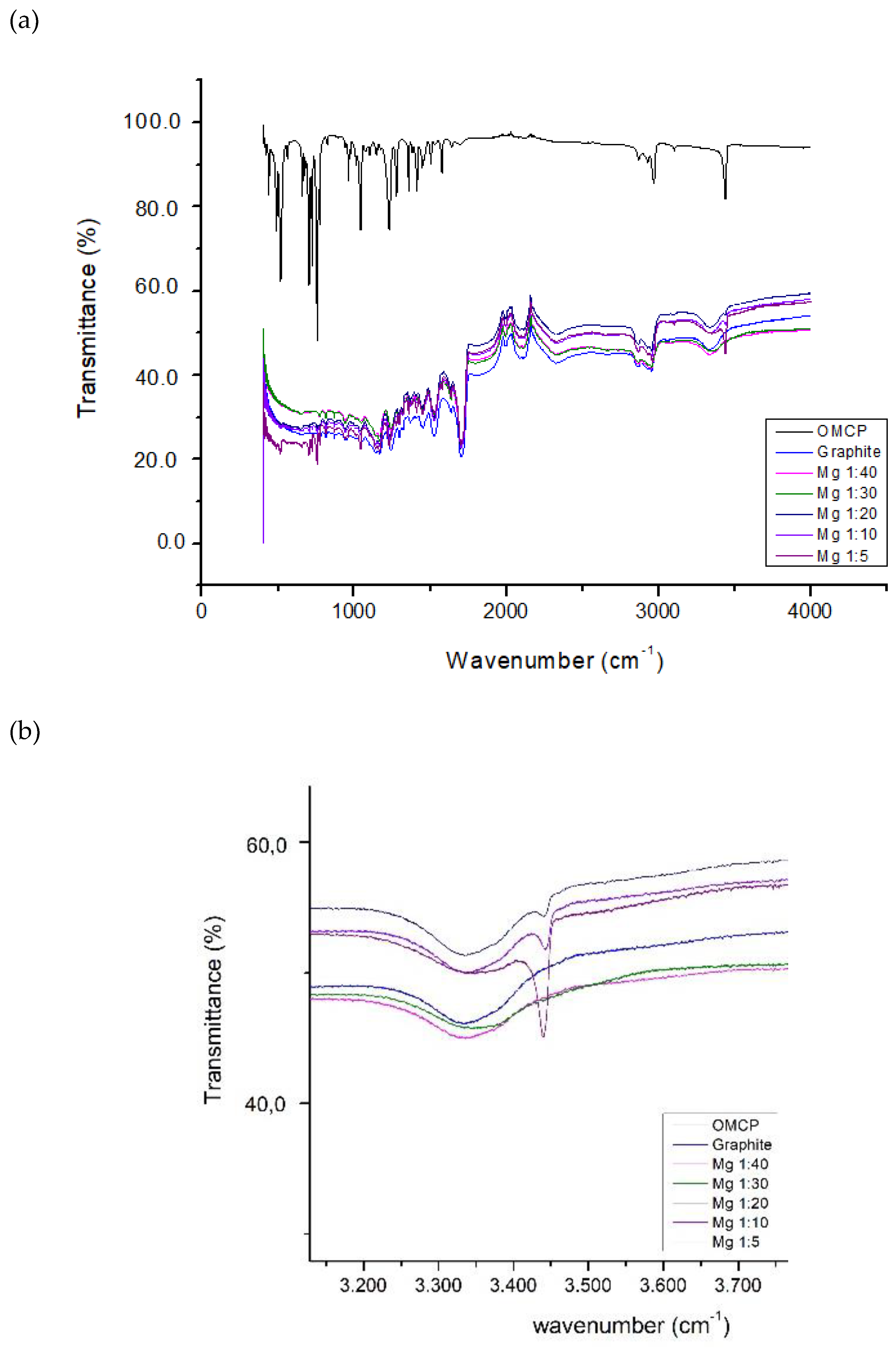

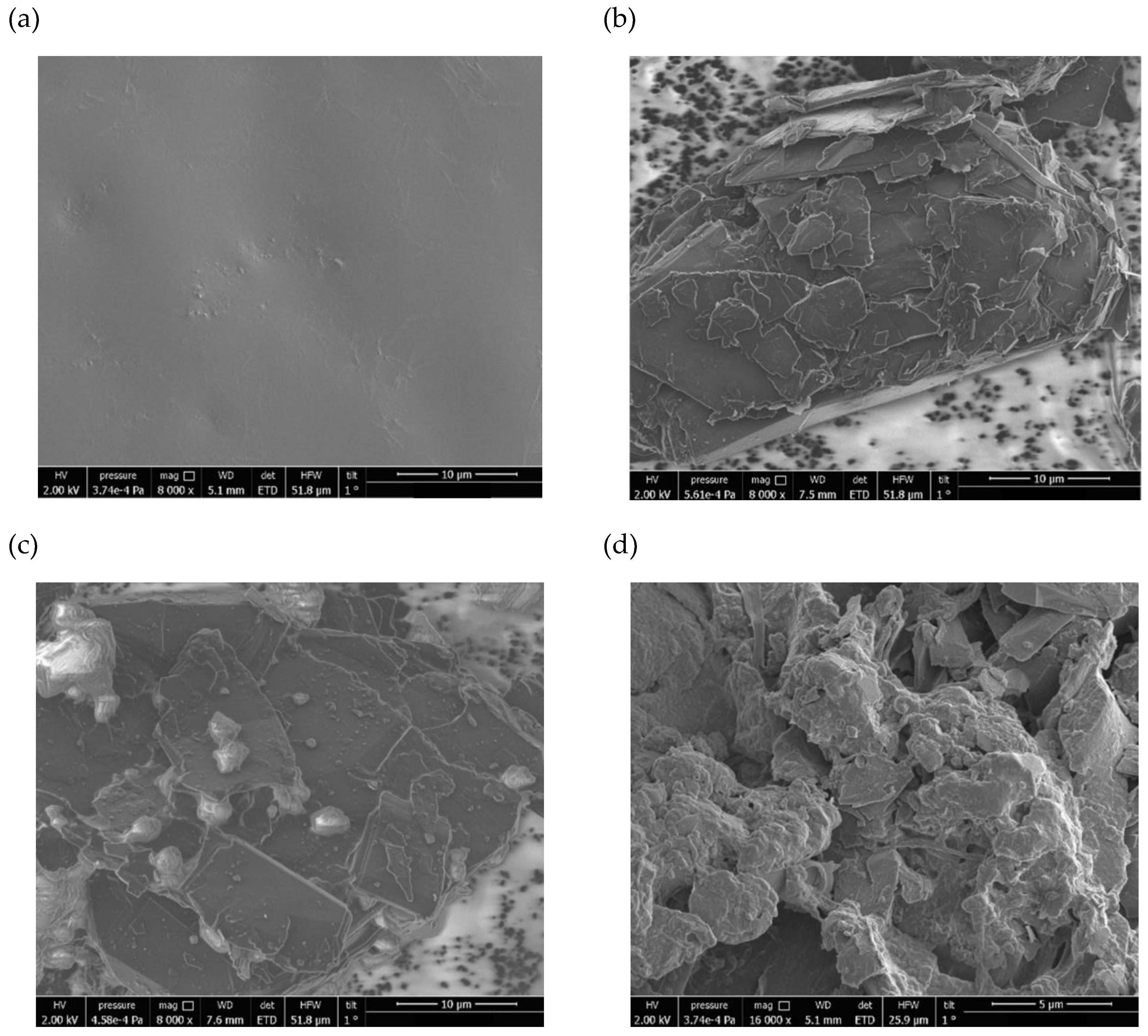

Creatinine Sensing Membrane: Construction and Characterization

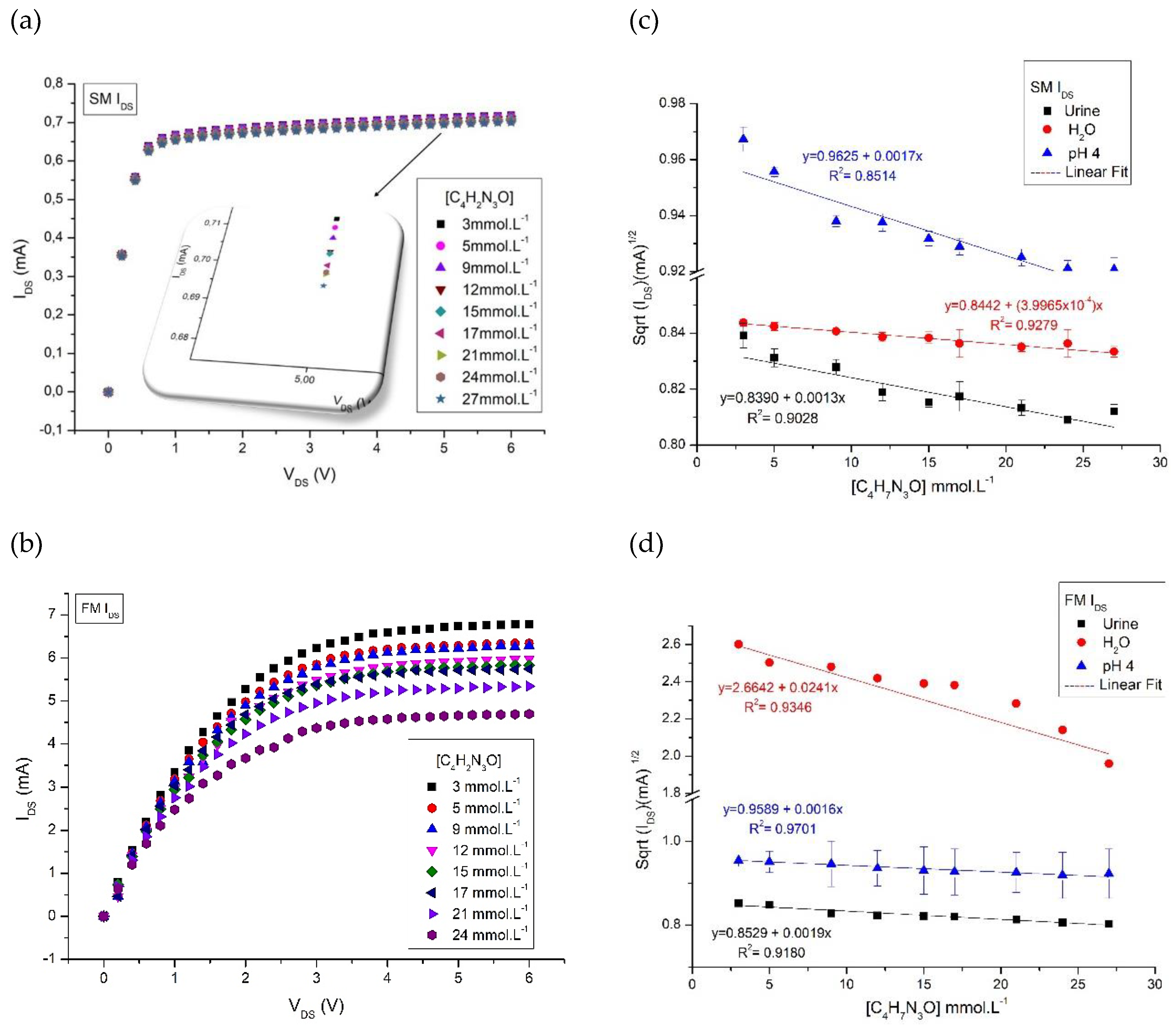

Commercial MOS transistor

Measurements

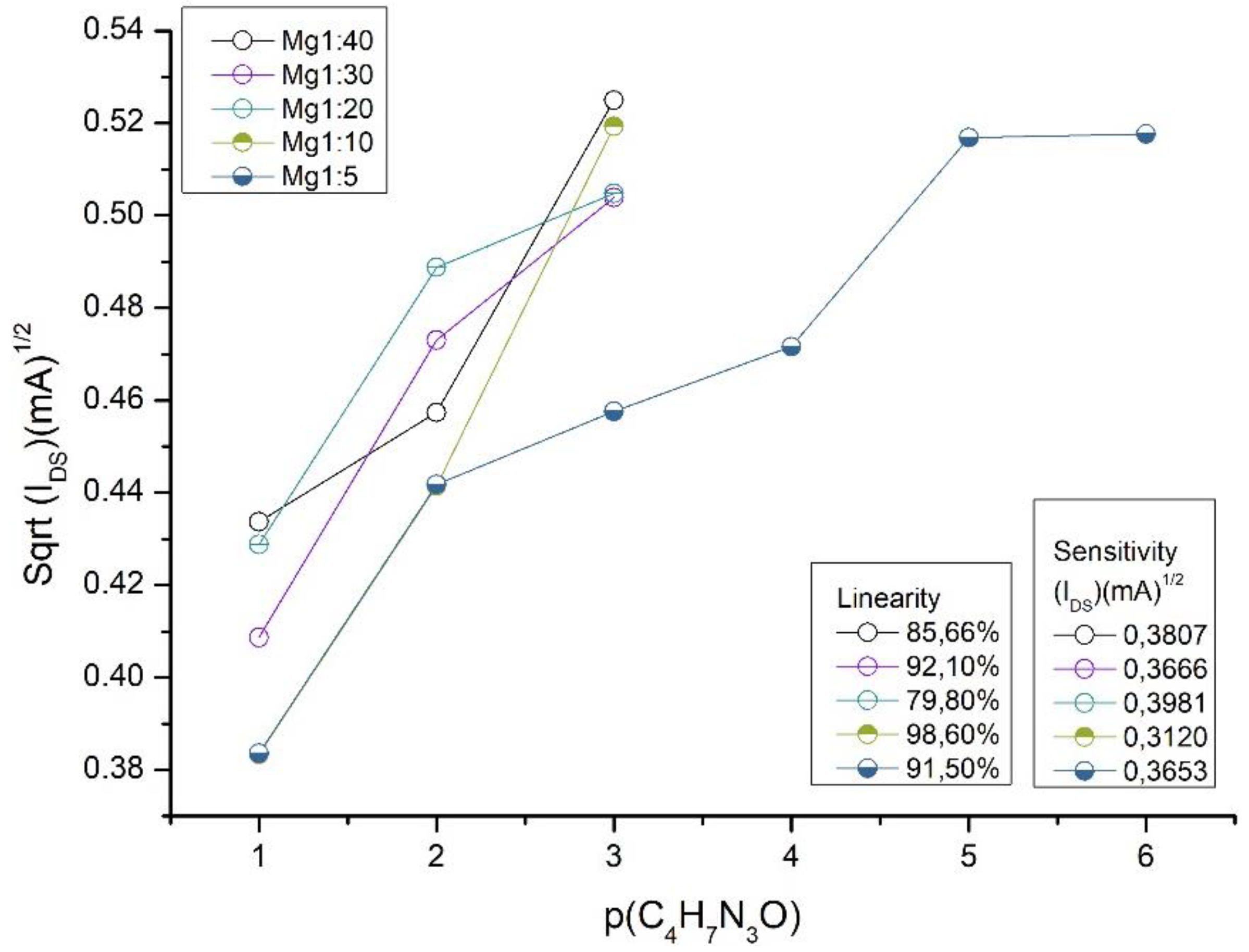

Sensor Evaluation Parameters

Results and Discussions

Conclusion

Supplementary Material

References

- [1] Mello, H. J. N. P. D., Bueno, P. R. & Mulato, M. Comparingglucose and urea enzymatic electrochemical and optical biosensors based on polyaniline thin films. Anal. Methods, 12, 4199–4210, (2020). [CrossRef]

- [2] Chiang, J.-L., Shang, Y.-G., B. K. Yadlapalli, F.-P. Yu, and Wuu, D.-S. Ga2o3nanorod-based extended-gate field-effect transistors for ph sensing. Materials Science and Engineering: B, 276, 115542, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [3] Niu, P., Jiang, J., Liu, K., Wang, S., Jing, J., Xu, T., Wang, T., Liu, Y. & Liu. T. Fiber-integrated wgm optofluidic chip enhanced by microwavephotonic analyzer for cardiac biomarker detection with ultra-high resolution. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 208, 114238, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [4] Sinha, A., Tai, T.-Y., Li, K.-H., Gopinathan, P., Chung, Y.-D., Sarangadharan, I., Ma, H.-P., Huang, P.-C., Shiesh, S.-C., Wang, Y.-L. & Lee, G.-B. An integrated microfluidic system with field-effect-transistor sensor arrays for detecting multiple cardiovascular biomarkers from clinical samples. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 129, 155–163, (2019). [CrossRef]

- [5] Laliberte, K., Scott, P., Khan, N. I., Mahmud, M. S. & Song, E. A wearable graphene transistor-based biosensor for monitoring il-6 biomarker. Microelectronic Engineering, 262, 111835, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [6] Song, P., Fu, H., Wang, Y., Chen, C., Ou, P. Rashid, R. T. Duan, S. Song, J. Mi, Z. & Liu, X. A microfluidic field-effect transistor biosensor with rolled-up indium nitridemicrotubes. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 190, 113264, (2021). [CrossRef]

- [7] Chou, C.-H., Lim, J.-C., Lai, Y.-H., Chen, Y.-T., Lo, Y.-H. & Huang, J.-J. Characterizations of protein-ligand reaction kinetics by transistor-microfluidic integrated sensors. Analytica Chimica Acta, 1110, 1–10, (2020). [CrossRef]

- [8] Chen, T.-Y., Yang, T.-H., Wu, N.-T., Chen, Y.-T. & Huang, J.-J. Transient analysis of streptavidin-biotin complex detection using an igzo thin film transistor-based biosensor integrated with a microfluidic channel. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 244, 642–648 (2017). [CrossRef]

- [9] Khizir H. A. & Abbas, T. A.-H. Hydrothermal synthesis of tio2 nanorods as sensing membrane for extended-gate field-effect transistor (egfet) ph sensing applications. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 333, 113231, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [10] Manjakkal, L., Sakthivel, B., Gopalakrishnan, N. & Dahiya, R. Printed flexibleelectrochemical ph sensors based on cuo nanorods,” Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 263, 50–58, (2018). [CrossRef]

- [11] Casimero, C., McConville, A., Fearon, J.-J., Lawrence, C. L. C., Taylor, M., Smith, R. B. & Davis, J. Sensor systems for bacterial reactors: A newflavin-phenol composite film for the in situ voltammetric measurement of ph. Analytica Chimica Acta, 1027, 1–8, (2018). [CrossRef]

- [12] Cho W.-J. & Lim, C.-M. Sensing properties of separative paper-based extended-gate ion-sensitive field-effect transistor for cost effective ph sensor applications. Solid-State Electronics, 140, 96–99, (2018). [CrossRef]

- [13] Rasheed, H. S., Ahmed, N. M. & Matjafri, M. Ag metal mid layer based on newsensing multilayers structure extended gate field effect transistor (eg-fet) for ph sensor. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing, 74, 51–56, (2018). [CrossRef]

- [14] Slewa, L. H., Abbas, T. A. & Ahmed, N. M. Synthesis of quantum dot porous silicon as extended gate field effect transistor (egfet) for a ph sensor application. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing, 100, 167–174, (2019). [CrossRef]

- [15] Kang, J.-W. & Cho, W.-J. Achieving enhanced ph sensitivity using capacitive coupling in extended gate fet sensors with various high-k sensing films. Solid-State Electronics, 152, 29–32, (2019). [CrossRef]

- [16] Bazilah, A., Awang, Z., Shariffudin, S. S., Hamid, N. H. & Herman, S. H. Sensing and physical properties of zno nanostructures membrane. Materials Today: Proceedings, 16, 1864–1870, (2019). [CrossRef]

- [17] Ahmed, N. M., Sabah, F. A., Kabaa, E. & Myint, M. T. Z. Single- and double-thread activated carbon fibers for ph sensing. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 221, 288–294, (2019). [CrossRef]

- [18] Chung, W.-Y., Silverio, A. A., Tsai, V. F., Cheng, C., Chang, S.-Y., Ming-Ying, Z., Kao, C.-Y., Chen, S.-Y., Pijanowska, D. G., Rustia, D. & Lo, Y.-W. An implementation of an electronic tongue system based on a multi-sensor potentiometric readout circuit with embedded calibration and temperaturecompensation. Microelectronics Journal, 57, 1–12, (2016). [CrossRef]

- [19] Pundir, C., Kumar, P. & Jaiwal, R. Biosensing methods for determination of creatinine: A review. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 126, 707–724, (2019). [CrossRef]

- [20] Dong, Y., Luo, X., Liu, Y., Yan, C., Li, H., Lv, J., Yang, L. & Cui, Y. Adisposable printed amperometric biosensor for clinical evaluation of creatinine inrenal function detection. Talanta, 248, 123592, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [21] Humphries, T. L., Vesey, D. A., Galloway, G. J., Gobe, G. C. & Francis, R. S. Identifying disease progression in chronic kidney disease using proton magneticresonance spectroscopy. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy, 134-135, 52–64, (2023). [CrossRef]

- [22] Mak, R. H. & Abitbol,bC. L. Standardized urine biomarkers in assessing neonatal kidney function: are we there yet?. Jornal de Pediatria, 97, 5, 476–477, (2021). [CrossRef]

- [23] Balhara, N., Devi, M., Balda, A., Phour, M. & Giri, A. Urine; a new promisingbiological fluid to act as a non-invasive biomarker for different human diseases. URINE, 5, 40–52, (2023). [CrossRef]

- [24] Lorente, D. G., Lorente, J. G. & Usach, T. S. Repeticion de lamedicion de creatinina serica en atencion primaria: no todos tienen insuficienciarenal crônica. Nefrologia, 35, 4, 395–402, (2015). [CrossRef]

- [25] Nkuipou-Kenfack ,E., Latosinska, A., Yang, W.Y., Fournier M.C., Blet, A., Mujaj, B., Thijs, L., Feliot, E., Gayat, E., Mischak, H., Staessen, J.A., Mebazaa, A., Zhang, Z.Y., French & European Outcome Registry in Intensive Care Unit Investigators. A novel urinary biomarker predicts 1-year mortality after discharge from intensive care. Crit Care, 24, 1, 10, (2020). [CrossRef]

- [26] Askenazi, D. J. No matter the hemisphere or language, neonatal acute kidney injury is common and is associated with poor outcomes. Jornal de Pediatria, 99, 3, 203–204, (2023). [CrossRef]

- [27] Stasyuk, N., Zakalskiy, A., Nogala, W., Gawinkowski, S., Ratajczyk, T., Bonarowska, M., Demkiv, O., Zakalska, O., & Gonchar, M. A reagentless amperometric biosensor for creatinine assay based on recombinant creatinine deiminase and n-methylhydantoin-sensitive cocu nanocomposite. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 393, 134276, (2023). [CrossRef]

- [28] Rumpel, J., Spray, B. J., Chock, V. Y., Kirkley, M. J., Slagle, C. L., Frymoyer, A., Cho, S.-H., Gist, K. M., Blaszak, R., Poindexter, B. & Courtney, S. E. Urinebiomarkers for the assessment of acute kidney injury in neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy receiving therapeutic hypothermia. The Journal of Pediatrics, 241, 133–140.e3, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [29] Moraes, L. H. A., Krebs, V. L. J., Koch, V. H. K., Magalhaes, N. A. M. & Carvalho, W. B. Risk factors of acute kidney injury in very low birth weight infantsin a tertiary neonatal intensive care unit. Jornal de Pediatria, 99, 3, 235–240, (2023). [CrossRef]

- [30] Barrio, R. C., Agustin, J. A., Manzano, M. C., Garcıa-Rubira, J. C., Fernandez-Ortiz, A., Vilacosta, I. & Macaya, C. In-hospital prognostic value of glomerular filtration rate inpatients with acute coronary syndrome and a normal creatinine level. Revista Espanola de Cardiologia (English Edition), 60, 7, 714–719, (2007). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17663855/.

- [31] Ashakirin, S. N., Zaid, M. H. M., Haniff, M. A. S. M., Masood, A. & Wee., M.F. M. R. Sensitive electrochemical detection of creatinine based on electrodeposited molecular imprinting polymer modified screen printed carbon electrode. Measurement, 210, 112502, (2023). [CrossRef]

- [32] Gonzalez-Gallardo, C. L., Arjona, N., Álvarez-Contreras, L., & Guerra-Balcázar, M. Electrochemical creatinine detection for advanced point-of-care sensing devices: a review. RSC Advances, 12, 47, 30785-30802, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [33] Jadhav, R. B., Patil, T. & Tiwari, A. P. Trends in sensing of creatinine by electrochemical and optical biosensors. Applied Surface Science Advances, 19, 100567, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [34] Guinovart, T., Hernandez-Alonso, D., Adriaenssens, L., Blondeau, P., Rius, F. X., Ballester, P. & Andrade, F. J. Characterization of a new ionophore-basedion-selective electrode for the potentiometric determination of creatinine in urine. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 87, 587–592, (2017). [CrossRef]

- [35] Kukkar, D., Zhang, D., Jeon, B. & Kim, K.-H. Recent advances in wearablebiosensors for non-invasive monitoring of specific metabolites and electrolytes associated with chronic kidney disease: Performance evaluation and future challenges. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 150, 116570, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [36] N.-J. M. M. Gohiya, P. Study of neonatal acute kidney injury based on kdigo criteria. Pediatrics and Neonatology, 63, 66–70, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [37] Costa, B. M. de C., Griveau, S., Bedioui, F., Orlye, F. d’, Silva, J. A. F. & Varenne, A. Stereolithography based 3d-printed microfluidic device with integratedelectrochemical detection. Electrochimica Acta, 407, 139888, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [38] Yörük, Ö., Uysal, D., Doğan, Ö. M. Carbon-assisted hydrogen production via electrolysis at intermediate temperatures: Impact of mineral composition, functional groups, and membrane effects on current density. Fuel, 380, 133268, (2025). [CrossRef]

- [39] Sacko, A., Nure, J. F., Motsa, M. M., Nyoni, H., Mamba, B., Nkambule, T., Msagati, T. A.M. Graphitic carbon nitride embedded in polymeric membrane from polyethylene terephthalate microplastic for water treatment. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 68, 106458, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [40] Wu, F., Li, X., Jiao, Y., Pan, C., Fan, G., Long, Y., Yang, H. Multifunctional flexible composite membrane based on nanocellulose-modified expanded graphite/electrostatically spun fiber network structure for solar thermal energy conversion. Energy Reports, 11, 4564-4571, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [41] Liu, H. Duan, P., Wu, Z., Liu, Y., Yan, Z., Zhong, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, X. Silicon/graphite/amorphous carbon composites as anode materials for lithium-ion battery with enhanced electrochemical performances. Materials Research Bulletin, 181, 113082, (2025). [CrossRef]

- [42] Hao, Y., Chen, D., Yang, G., Hu, S., Wang, S., Pei, P., Hao, J., Xu, X. N-doped porous graphite with multilevel pore defects and ultra-high conductivity anchoring Pt nanoparticles for proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers. Journal of Energy Chemistry, In press (2024). [CrossRef]

- [43] Song, C., Liu, M., Du, L., Chen, J., Meng, L., Li, H. Hu, J. Effect of grain size of graphite powder in carbon paper on the performance of proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Journal of Power Sources, 548, 2022, 232012, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [44] Corba, A., Sierra, A. F., Blondeau, P., Giussani, B., Riu, J., Ballester, P., Andrade, F. J. Potentiometric detection of creatinine in the presence of nicotine: Molecular recognition, sensing and quantification through multivariate regression. Talanta, 246, 123473, (2022). [CrossRef]

- [45] Guinovart, T., Hernández-Alonso, D., Adriaenssens, L., Blondeau, P., Martínez-Belmonte, M., Rius, F. X., Andrade, F. J., Ballester, P. Recognition and Sensing of Creatinine. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 55, 7, 2435-2440. (2016). [CrossRef]

- [46] Lu, Y., Wang, S., He, S., Huang, Q., Zhao, C., Yu, S., Jiang, W., Yao, H., Wang, L., & Yang, L. An endo-functionalized molecular cage for selective potentiometric determination of creatinine. Chem. Sci. 15, 36, 14791-14797, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [47] Sedra A. S. & Smith, K. C. Microelectronic Circuits, 5th ed. Oxford University Press, (2004).

- [48] Ko, C., Tseng, C., Lu, S., Lee, C., Kim, S., & Fu, L. Handheld microfluidic multiple detection device for concurrent blood urea nitrogen and creatinine ratio determination using colorimetric approach. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 422, 136585, (2025). [CrossRef]

- [49] Parra, L. M. H., Laucirica, G., Toimil-Molares, M. E., Marmisollé, W., & Azzaroni, O. Sensing creatinine in urine via the iontronic response of enzymatic single solid-state nanochannels, Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 268, 116893, (2025). [CrossRef]

- [50] Das, C., Raveendran, J., Bayry, J. & Rasheed, P. A. Selective and naked eye colorimetric detection of creatinine through aptamer-based target-induced passivation of gold nanoparticles. RSC Adv., 14, 46, 33784-33793 (2024). [CrossRef]

- [51] Chandhana J.P., Roshith M., Vasu, S. P., Kumar, D. V. R., Satheesh B. T.G., High aspect ratio copper nanowires modified screen-printed carbon electrode for interference-free non-enzymatic detection of serum creatinine in neutral médium. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 971, 118605, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [52] Peng, S., Yan, L., You, R., Lu, Y., Liu, Y. & Li, L. Cationic cellulose dispersed Ag NCs/C-CNF paper-based SERS substrate with high homogeneity for creatinine and uric acid detection. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 282, 136724, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [53] Saputra, E. A colorimetric detection of creatinine based-on EDTA capped-gold nanoparticles (EDTA-AuNPs): Digital image colorimetry. Sensors International, in press, 100286, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [54] Manikandan, R., Yoon, J., Lee, J. & Chang, S. Non-enzymatic disposable paper sensor for electrochemical detection of creatinine. Microchemical Journal, 204, 111114, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [55] Huang, J., Sokolikova, M., Ruiz-Gonzalez, A., Kong, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Xu, L., Wang, M., & Mattevi, C., Davenport, A., Lee, T. & Li, B. Ultrasensitive colorimetric detection of creatinine via its dual binding affinity for silver nanoparticles and silver ions. RSC Adv., 14, 13, 9114-9121 (2024). [CrossRef]

- [56] Sasikumar, T., Shanmugaraj, K., Nandhini, K., Kim, J. T., & Ilanchelian, M. Red-emitting copper nanoclusters for ultrasensitive and selective detection of creatinine and its application in portable smartphone-based paper strips and polymer thin film. Surfaces and Interfaces, 53, 105014, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [57] Zhang, Q., Yang, R., Liu, G., Jiang, S., Wang, J., Lin, J., Wang, T., Wang, J., Huang, Z. Smartphone-based low-cost and rapid quantitative detection of urinary creatinine with the Tyndall effect, Methods, 221, 12-17, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [58] Bajpai, S., Akien, G. R., & Toghill, K. E. An alkaline ferrocyanide non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor for creatinine detection. Electrochemistry Communications, 158, 107624, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [59] Tirkey, A. & Babu, P. J. Synthesis and characterization of citrate-capped gold nanoparticles and their application in selective detection of creatinine (A kidney biomarker), Sensors International, 5, 100252, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [60] Chhillar, M., Kukkar, D., Yadav, A. K. & Kim, K. Nitrogen doped carbon dots and gold nanoparticles mediated FRET for the detection of creatinine in human urine samples. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 321, 124752, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [61] Nazar, H. R. S., Ahmadi, V. & Nazar, A. R. S. Mach-Zehnder interferometer fiber optic sensor coated with UiO-66 metal organic framework for creatinine detection. Measurement, 225, 114015, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [62] Patel, M. R., Park, T. J., & Kailasa, S. K. Eu3+ ion-doped strontium vanadate perovskite quantum dots-based novel fluorescent nanosensor for selective detection of creatinine in biological samples. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 449, 115376, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [63] Afshary, Hosein & Amiri, Mandana. A fast and highly selective ECL creatinine sensor for diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Sens. Diagn. 3, 9, 1562-1570 (2024). [CrossRef]

- [64] Mishra, P., Gupta, P., Singh, B. P., Kedia, R., Shrivastava, S., Patra, A., Hwang, S., & Agrawal, V. V. Advancing paper microfluidics: A strategic approach for rapid fabrication of microfluidic paper-based analytical devices (µPADs) enabling in-vitro sensing of creatinine. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 411, 125707, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [65] Das, M., Chakraborty, T. & Kao, C. H. Sol-gel synthesized RexBi1-x-O thin films for electrochemical creatinine sensing: A facile fabrication approach. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 315, 128889, (2024). [CrossRef]

- [66] Grochocki, W., Markuszewski, M. J. & Quirino, J. P. Simultaneous determination of creatinine and acetate by capillary electrophoresis with contactless conductivity detector as a feasible approach for urinary tract infection diagnosis. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 137, 178-181, (2017). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).