1. Introduction

In the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the rapid development of digital technology worldwide, Vietnam is actively advancing its digital transformation across various sectors. In the National Digital Transformation Strategy of Vietnam, Education is regarded as the most crucial field for prioritization in digital transformation, after healthcare. However, the shift from in-person interaction to online communication may lead to feelings of social isolation, exacerbating mental health issues [

1]

Firstly, young people, such as students who spend more time on social media, are at higher risk of experiencing symptoms of depression [

1,

2]. Secondly, the increase in university tuition fees has intensified financial pressures, with about 33% to 70% of college students reporting financial stress, and 9% to 40% indicating it negatively affects their academic performance [

3].

Additionally, academic pressure and grading expectations are heavily influenced by cultural factors, with notable differences observed between continents, particularly between Asia and other regions. In many Asian countries, especially those with a Confucian cultural heritage like China, Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam, families place high expectations on their children's academic achievements. Research by Tan and Yates [

4], expectations are a primary source of academic stress for Asian students. Academic achievement is considered a central measure of success and social status, creating substantial pressure on students to attain high grades and stand out in their classes. School culture in Asia often emphasizes hard work and exam performance, resulting in significant pressure on students.

Using a methodology that builds on prior research and a questionnaire survey of 100 students from universities across Vietnam, this study aims to address the following questions:

To provide a preliminary assessment of the prevalence of depression among students in Vietnam in the new era (post-Covid-19), what are the observed trends?

Do new contexts, such as universities gaining financial autonomy, create additional pressures for students?

Compare the depression rates between 2024 and 2019 and analyze the differences.

In conclusion, this study positions itself within the broader context of the digital transformation of education in Vietnam and its implications for student mental health. By focusing on the impact of academic pressure, financial stress, and social isolation on depression among university students, it seeks to address a gap in the current literature, particularly in the post-COVID-19 era. Through a qualitative approach, the study aims to assess the prevalence of depression, explore new sources of stress arising from financial autonomy in universities, and compare current trends with those observed in previous years. The following sections will outline the methodology, present the findings, and discuss the implications for improving mental health support and creating a more conducive university environment in Vietnam.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Depression and Anxiety

Depression and anxiety are the two most common mental health problems, and they often begin during adolescence [

5]. Depression is one of the most common psychological disorders, affecting millions of people worldwide. It not only has negative impacts on mental health but also affects quality of life and individuals' ability to work. Research has shown that biological factors play an important role in the development of depression. These factors include genetics, chemical imbalances in the brain, and other neurological factors. For example, a study by Remes [

6] highlighted that biological factors, such as neurotransmitter imbalances involving serotonin and dopamine, are closely linked to depression.

Psychological factors also play a key role in the development of depression. These include past negative experiences, self-esteem issues, and other psychological disorders. Lim indicated that depression is often associated with feelings of sadness, low self-esteem, loss of interest, and anxiety [

7]. Additionally, psychological factors such as loneliness and a sense of isolation can contribute to the development of depression.

Social factors, including living environment, social relationships, and cultural factors, can also influence depression. Research by Bernaras revealed that negative social relationships and sociocultural changes can increase the risk of depression [

8]. Furthermore, factors such as work pressure, unemployment, and financial issues can contribute to the onset of depression.

In summary, depression is a complex disorder with interrelated biological, psychological, and social factors. Understanding these factors can help us develop more effective treatment methods and improve patients' quality of life.

3.1. DASS-21 Depression Scale

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) is a self-assessment tool comprising 21 items, designed to measure the severity of negative emotional states related to depression, anxiety, and stress. This is a shortened version of the DASS-42 scale and is widely used in both clinical and non-clinical settings to assess general psychological conditions and associated symptoms.

DASS-21 consists of three subscales, each with 7 items (Table xx). Participants read each statement and select a number from 0 to 3 to indicate the extent to which the statement applied to them over the past week:

0: Did not apply to me at all

1: Applied to me to some degree, or some of the time

2: Applied to me to a considerable degree, or a good part of the time

3: Applied to me very much, or most of the time

Table 1.

The Scale and Symptom Assessment of DASS-21.

Table 1.

The Scale and Symptom Assessment of DASS-21.

| Scale |

Assessment of symptoms |

| Depression Scale |

Assess symptoms such as sadness, loss of interest, low self-esteem, and feelings of hopelessness. |

| Anxiety Scale |

Assess symptoms such as autonomic arousal, musculoskeletal effects, situational anxiety, and subjective feelings of anxiety. |

| Stress Scale |

Assess symptoms related to difficulty relaxing, nervous system arousal, and easy excitability. |

The DASS-21 is used to assess the severity of psychological symptoms and to monitor changes in psychological states over time. In the field of higher education, DASS-21 has been widely applied to evaluate students' mental health. A study by Long et al. (2020) confirmed the validity of the DASS-21 scale for screening Vietnamese students' mental health in an online learning environment. The findings indicated that the prevalence rates of moderate to high levels of depression, anxiety, and stress were 50%, 19.7%, and 37.3%, respectively. [

9]

Another study by Zhang et al. (2024) conducted a structural analysis and invariance testing of the DASS-21 scale among Chinese students. The results showed that the three-factor structure of DASS-21 was stable and that there were high correlations among the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress.[

10]

3.2. Vietnam’s Higher Education Environment

The university environment in Vietnam presents a critical context for understanding and addressing mental health issues among students. Research highlights that Vietnamese university students often experience significant stress, depression, and anxiety due to academic pressure, limited access to mental health resources, and societal stigma around seeking psychological help. A study by

Dessauvagie et al. (2022) revealed low mental health literacy (MHL) among university students, with many failing to recognize symptoms of mental disorders, which further discourages help-seeking behaviors. Male students and those in STEM fields were particularly at risk, suggesting the need for targeted mental health promotion programs.[

11]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the transition to online learning exacerbated mental health issues, with over 50% of students experiencing moderate to severe depression or stress. Female students reported significantly higher distress levels than their male counterparts [

9]. Similarly, initiatives such as the "School-Based Mental Health Collaboration" aimed to mitigate these effects through training webinars and support services. These efforts demonstrated the potential for scalable mental health interventions but underscored the importance of long-term planning and resource allocation [

12]

Furthermore, help-seeking behaviors among students remain limited due to psychological openness and barriers such as stigma.

Nguyen Thai and Nguyen (2018) emphasized the importance of improving students' ability to identify depression and encouraging the use of professional mental health services through tailored educational programs [

13]. Promoting nature-relatedness and extracurricular activities has also been identified as an effective strategy to enhance well-being[

14].

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Design

This study adopts a cross-sectional qualitative research design to explore the impact of the university environment on depression among students in Vietnam. A structured questionnaire is used to gather data on various environmental stressors and their relationship with depressive symptoms. Specifically, the study applies the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) to assess depressive symptoms quantitatively, while open-ended questions offer additional qualitative insights.

4.2. Questionnaire

The questionnaire is divided into five main categories that address academic pressure, social relationships, financial constraints, institutional support, and depressive symptoms. The first four sections use a 5-point Likert scale (1 - Strongly Disagree to 5 - Strongly Agree) to gauge students' perceptions and experiences across various stressors. Sample questions for academic pressure include “I feel overwhelmed by the volume of coursework” and “I worry constantly about my grades.” Social relationships are assessed through questions like “I find it challenging to make new friends” and “I often feel lonely at university.” Institutional support is evaluated with questions such as “The university provides adequate resources for my studies,” while financial pressures are addressed with items like “I worry about affording my tuition fees.”

The depressive symptoms section uses the DASS-21 scale to assess students' experiences of depression, anxiety, and stress over the previous two weeks. The DASS-21, a validated self-report measure, consists of 21 items divided into three subscales: depression, anxiety, and stress, with seven items each. Students rate each item on a 4-point scale (0 - Did not apply to me at all to 3 - Applied to me most of the time). The depression subscale includes items such as “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all” and “I felt that life was meaningless.” Higher scores on each subscale indicate greater levels of depressive, anxiety, or stress symptoms. DASS-21 scores are then multiplied by two to match the original DASS-42 scoring system, allowing for a nuanced assessment of symptom severity.

4.3. Sampling

The study sample comprises 100 university students selected using convenience sampling through online recruitment facilitated by Google Forms. The survey was distributed via email and social media platforms, making it accessible to students from various Vietnamese universities. The sample represents diverse academic years and majors, ensuring a comprehensive view of the student population. The distribution of students by academic year is as follows: 29.8% in Year 1, 59.6% in Year 2, 8.5% in Year 3, and a minimal proportion in Year 4.

Participants’ fields of study include a wide range of disciplines, which provides additional diversity in the sample. Among the fields represented are International Political Economy, International Business, Business Administration, Finance, Business Analytics, Biology Education, International Trade Law, Embedded System Development, Marketing, and Engineering fields such as Computer Engineering and Electrical Engineering. Other areas include Economics, Primary Education, Project Management, Biotechnology, and fields under social sciences and humanities, such as Vietnamese History and Education in Geography. This range of disciplines allows the study to capture the unique stressors related to each field, as students in different programs may experience varying levels of academic pressure, career-related anxieties, and institutional support.

4.4. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected through an online survey distributed across student networks and social media platforms, facilitating accessibility for participants from various Vietnamese universities. Quantitative data from the Likert-scale responses and DASS-21 scores were coded and analyzed using statistical software. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation) provided an overview of the prevalence of stressors and depressive symptoms, while scores from the DASS-21 enabled a detailed breakdown of symptom severity.

Qualitative responses to open-ended questions were coded and subjected to thematic analysis to identify key themes related to academic, financial, and social stressors. This thematic analysis helped contextualize the quantitative findings, offering a comprehensive understanding of the primary factors influencing depressive symptoms among students.

Table 2.

The rate of students with depression according to DASS 21 in 2024 (Source: Author).

Table 2.

The rate of students with depression according to DASS 21 in 2024 (Source: Author).

Table 3.

The rate of students with depression according to DASS 21 in 2021: Data form Nguyet et al, 2021 [

15].

Table 3.

The rate of students with depression according to DASS 21 in 2021: Data form Nguyet et al, 2021 [

15].

5. Results

5.1. Depression Symptoms in DASS-2

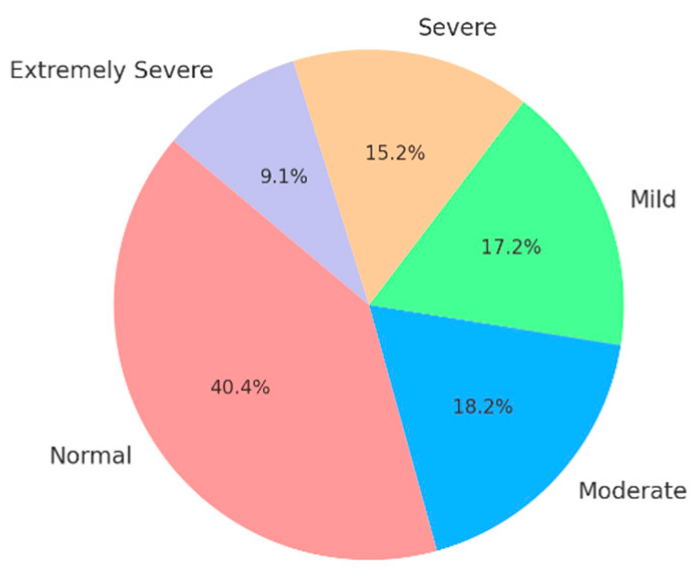

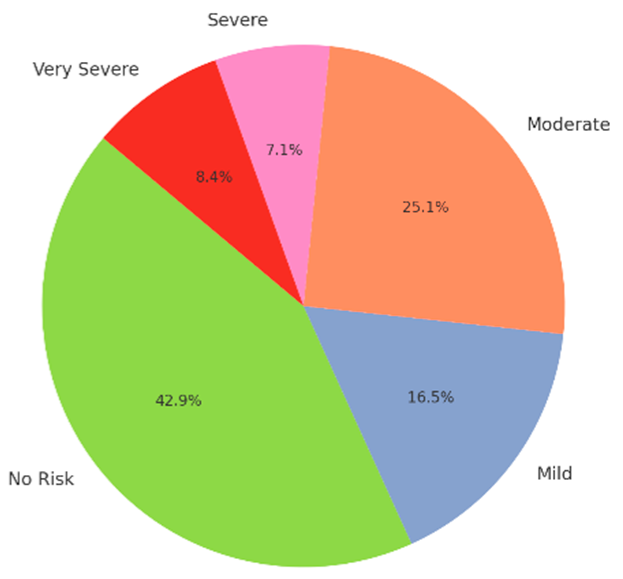

Based on the findings of Phan et al. and the data collected by our research, we can illustrate the results using the two following charts.

The results from a comparative chart on depression rates among Vietnamese students over two periods, 2020-2021 and 2024, indicate a significant upward trend in severe depression levels, while the percentage of students with no risk of depression has decreased. Specifically, the rate of students without depression symptoms ("No Risk") declined from 42.9% in 2020-2021 to 40.4% in 2024. This reflects a general decline in mental well-being among students, with fewer students achieving a healthy psychological state. This trend may stem from the prolonged impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted daily life and required extended adaptation to online learning formats. According to Nguyet et al. (2021), these factors led to a noticeable increase in symptoms of anxiety, stress, and depression among Vietnamese university students [

15]. The World Health Organization (WHO) in Vietnam also affirmed that the pandemic caused higher stress levels in the community, especially among young people, due to changes in learning and a lack of social connection.

Additionally, the proportion of students in the "Severe Depression" and "Very Severe Depression" categories has risen significantly from 2020 to 2024. The percentage of students in the "Severe Depression" group increased from 8.4% to 15.2%, while those in the "Very Severe Depression" category rose from 7.1% to 9.1%. This increase suggests that not only are more students experiencing depression symptoms, but the severity of these symptoms has also escalated. Academic pressure and high expectations from family may be key contributing factors. Thao et al. (2024) highlighted that Vietnam's highly competitive education system places considerable pressure on students to excel, leading to stress and a heightened risk of depression. Furthermore, financial difficulties and rising living costs, particularly in major cities, also exert economic pressure on students and their families[

16]. Research by Mai et al, (2022) showed that students struggling to meet living expenses have a higher risk of experiencing depression and anxiety symptoms.[

17]

Another notable point is the shift in the "Mild" and "Moderate" categories. The percentage of students with "Mild" depression symptoms slightly increased from 16.5% to 17.2%, while the "Moderate" group decreased from 25.1% to 18.2%. This may suggest that some students from the mild and moderate groups have progressed to more severe depression levels. This shift may partially be explained by the influence of social media. Gabrielle et al. (2024) found that the increased use of social media is linked to higher depression levels, as students often compare themselves to others, leading to feelings of inadequacy and loss of confidence.[

18] Additionally, the lack of psychological support services within educational institutions, as noted by UNICEF Vietnam (2020), contributes to the rise in depression among students, as they do not receive timely support and intervention.

The findings of this study emphasize that depression among Vietnamese students has worsened over time, with an increase in severe and very severe cases. This trend underscores the need for greater attention to student mental health. Addressing this issue requires intervention from universities and society, including improved counseling services, reduced academic pressure, and a supportive environment for students. Raising awareness of mental health, along with support measures from schools and families, will play a crucial role in mitigating depression and enhancing the mental well-being of students.

5.2. Psychological Factors Affecting UNIVERSITY students

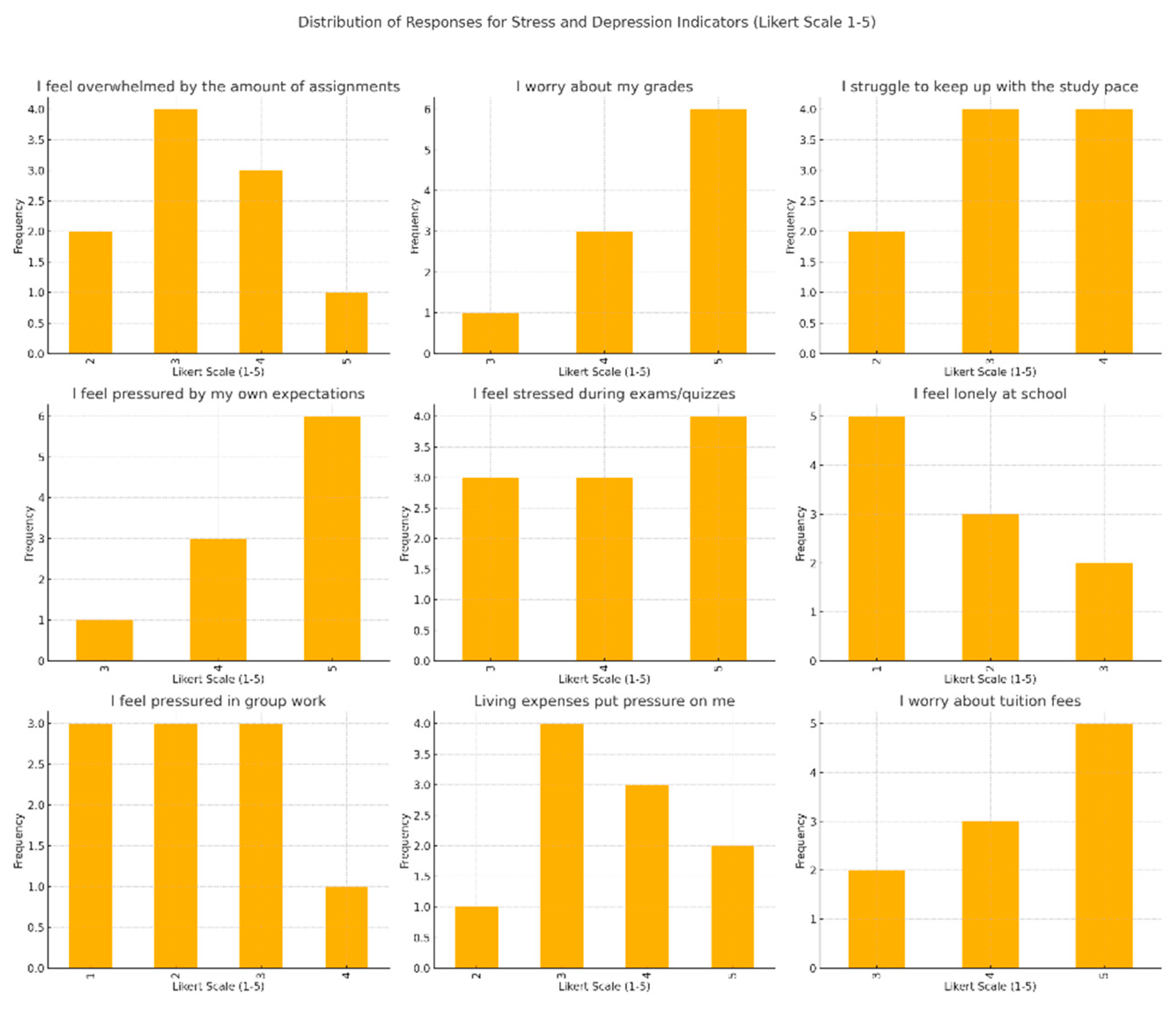

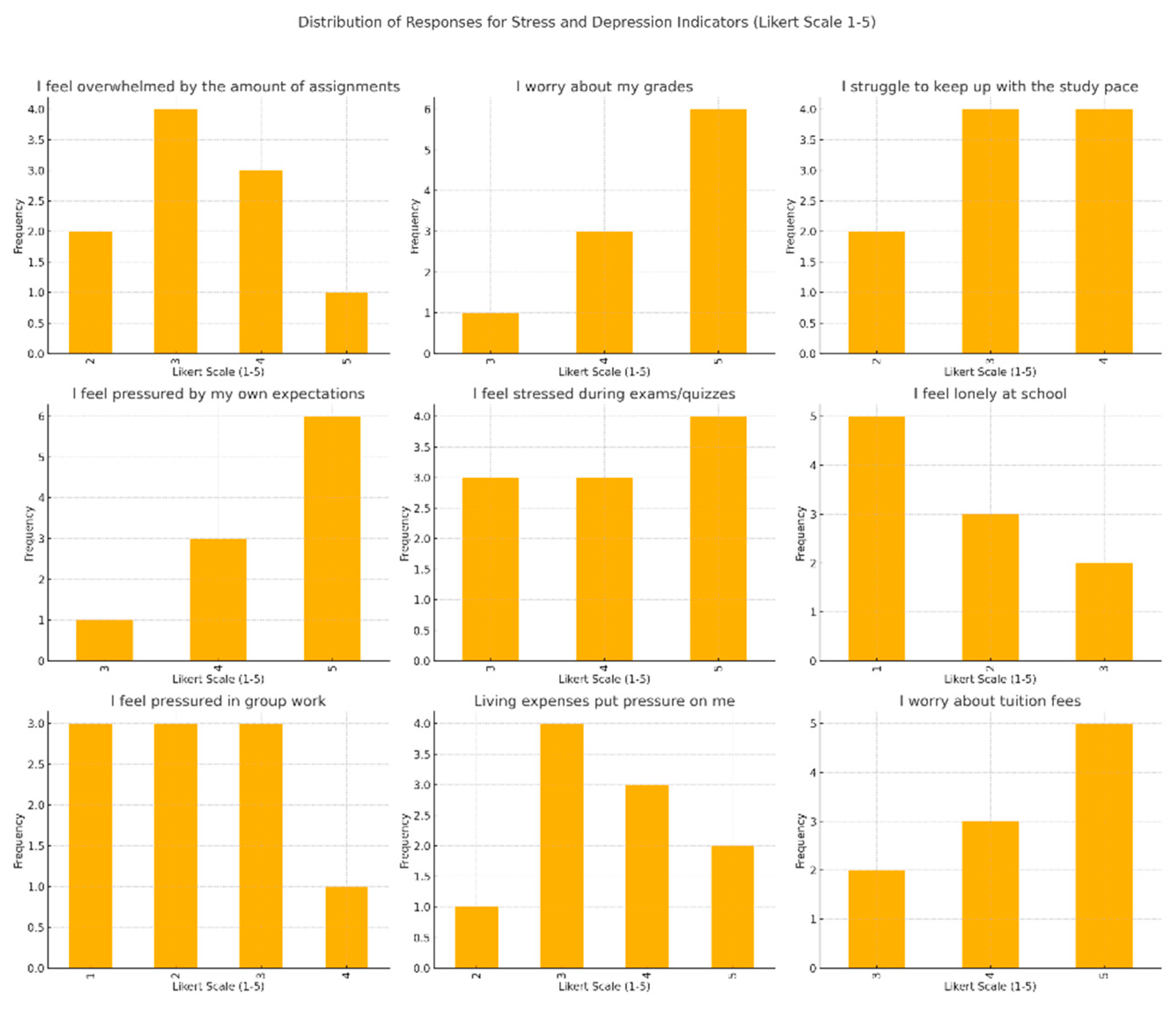

The analysis of this data further substantiates the impact of the educational environment on student mental health with concrete statistics. For example, concerning academic stress, the indicator "I worry about my grades" has a high mean rating of 4.5 on a Likert scale (1-5), with a mode of 5, indicating that the majority of students feel significant concern regarding their academic performance. Similarly, "I feel stressed during exams/quizzes" has a mean score of 4.1, with 75% of students rating this factor at 4 or higher. This data points to exams as a primary stressor, reinforcing the notion that performance pressure is a substantial psychological challenge within educational settings.

Social factors show equally concerning trends. The question "I feel lonely at school" has a mean score of 3.7, with a substantial portion of students indicating moderate to high levels of loneliness. Additionally, a strong positive correlation (0.95) exists between "I have difficulty making new friends" and "I feel lonely at school," suggesting that social isolation is both a cause and effect of difficulties in forming peer connections. This finding highlights the need for institutions to facilitate social integration and support networks to mitigate these effects.

Financial concerns add another layer of stress, with "Living expenses put pressure on me" having a mean score of 3.8, and the majority of responses falling between 3 and 5. The correlation between financial pressures and academic stressors is notable; for instance, a negative correlation (-0.52) exists between "I have to work part-time to cover expenses" and "Library and resources are adequate," indicating that financially strained students might struggle to utilize academic resources effectively.

These statistics offer robust evidence that educational environments significantly affect students' mental health. The high frequency of stress across academic, social, and financial domains calls for a comprehensive approach to student support, addressing not only academic pressures but also the socio-economic challenges that influence student well-being.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Responses for Stress and Depression Indicators (Likert Scale 1–5): (a) Distribution of responses for feeling overwhelmed by the amount of assignments, showing a high concentration on the upper end of the scale, indicating significant stress; (b) Responses regarding worrying about grades, which also cluster at higher values, reflecting academic concerns; (c) Responses about struggling to keep up with the study pace, with a substantial proportion indicating difficulty; (d) Responses about feeling pressured by their own expectations, with mixed but notable responses on the higher end; (e) Responses related to stress during exams/quizzes, showing significant stress among respondents; (f) Responses about feeling lonely at school, demonstrating variability but with notable high-end responses; (g) Responses about feeling pressured in group work, showing moderate variability; (h) Responses about living expenses putting pressure on respondents, with moderate to high values; (i) Responses about worrying about tuition fees, again showing moderate to high values across the sample.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Responses for Stress and Depression Indicators (Likert Scale 1–5): (a) Distribution of responses for feeling overwhelmed by the amount of assignments, showing a high concentration on the upper end of the scale, indicating significant stress; (b) Responses regarding worrying about grades, which also cluster at higher values, reflecting academic concerns; (c) Responses about struggling to keep up with the study pace, with a substantial proportion indicating difficulty; (d) Responses about feeling pressured by their own expectations, with mixed but notable responses on the higher end; (e) Responses related to stress during exams/quizzes, showing significant stress among respondents; (f) Responses about feeling lonely at school, demonstrating variability but with notable high-end responses; (g) Responses about feeling pressured in group work, showing moderate variability; (h) Responses about living expenses putting pressure on respondents, with moderate to high values; (i) Responses about worrying about tuition fees, again showing moderate to high values across the sample.

6. Conclusions

Through thematic analysis of interviews with 100 students, the research identifies key factors contributing to depressive symptoms, with academic pressure emerging as the most prominent determinant. In addition, social relationship difficulties and career-related anxiety were found to exacerbate mental health challenges among students.

The findings underscore the critical role of universities in shaping students' psychological well-being. Given the increasing prevalence of depression among university students, it is imperative that academic institutions prioritize the implementation of comprehensive psychological support systems. Furthermore, creating a more supportive and inclusive academic environment, where the emphasis on academic performance is balanced with mental health considerations, is essential for mitigating the adverse effects of stress on student well-being.

This research highlights the need for targeted interventions that address the unique stressors faced by students in higher education, particularly in the context of cultural expectations prevalent in Vietnam and other Asian countries. Future studies should explore longitudinal data and examine the effectiveness of institutional policies aimed at reducing student depression. In doing so, universities can play a pivotal role in fostering not only academic success but also the holistic development and mental health of their students.

References

- Świdziński, R.; Gryc, A.; Golemo, J.; Nowińska, A.; Lipiec, J. Social media and the possibility of depressive states in young adults. Journal of Education, Health and Sport 2022, 12, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettmann Schaefer, J.; Anstadt, G.; Casselman, B.; Ganesh, K. Young Adult Depression and Anxiety Linked to Social Media Use: Assessment and Treatment. Clinical Social Work Journal 2021, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.; McCarty, C.A.; Carter, S. The Impact of Financial Stress on Academic Performance in College Economics Courses. The Academy of Educational Leadership Journal 2015, 19, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.B.; Yates, S. Academic expectations as sources of stress in Asian students. Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal 2011, 14, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Il Shin, J.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry 2022, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remes, O.; Mendes, J.F.; Templeton, P. Biological, Psychological, and Social Determinants of Depression: A Review of Recent Literature. Brain Sci 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, G.Y.; Tam, W.W.; Lu, Y.; Ho, C.S.; Zhang, M.W.; Ho, R.C. Prevalence of Depression in the Community from 30 Countries between 1994 and 2014. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernaras, E.; Jaureguizar, J.; Garaigordobil, M. Child and Adolescent Depression: A Review of Theories, Evaluation Instruments, Prevention Programs, and Treatments. Front Psychol 2019, 10, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, N.; Hanh, N.; Lan, H. Validation of depression, anxiety and stress scales (DASS-21): Immediate psychological responses of students in the e-learning environment. International Journal of Higher Education 2020, 9, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, R.; Qiu, A.; Wu, H.; Wu, S.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, J. Application of DASS-21 in Chinese students: invariance testing and network analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessauvagie, A.; Dang, H.-M.; Truong, T.; Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, B.H.; Cao, H.; Kim, S.; Groen, G. Mental Health Literacy of University Students in Vietnam and Cambodia. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanh, H.P.; Nam, T.T.; Vinh, L.A. Initiatives to Promote School-Based Mental Health Support by Department of Educational Sciences, University of Education Under Vietnam National University. In University and School Collaborations during a Pandemic: Sustaining Educational Opportunity and Reinventing Education, Reimers, F.M., Marmolejo, F.J., Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 321-331. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Thai, Q.C.; Nguyen, T.H. Mental health literacy: knowledge of depression among undergraduate students in Hanoi, Vietnam. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2018, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc Nguyen, C.T.; Nguyen, Q.-A.N. Is nature relatedness associated with better mental health? An exploratory study on Vietnamese university students. Journal of American college health : J of ACH 2022, 1-8.

- Nguyệt Hà, P.; Thơ Nhị, T. TRẦM CẢM Ở SINH VIÊN TRƯỜNG ĐẠI HỌC Y HÀ NỘI NĂM HỌC 2020-2021 TRONG BỐI CẢNH ĐẠI DỊCH COVID-19 VÀ MỘT SỐ YẾU TỐ LIÊN QUAN. Tạp chí Y học Việt Nam 2022, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.V.; Nguyen, H.T.L.; Tran, X.M.T.; Tashiro, Y.; Seino, K.; Van Vo, T.; Nakamura, K. Academic stress among students in Vietnam: a three-year longitudinal study on the impact of family, lifestyle, and academic factors. Journal of Rural Medicine 2024, 19, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, P.P.; Hai, T.N.; Viet, T.D.M.; Van, H.T.H. 15. Depression, axiety and associated factors among young people during the second wave of Covid-19 in vietnam. Tạp chí Nghiên cứu Y học 2022, 154, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielle, T.; Sonne, M.; Indolo, N.N. The Impact of Social Media on Adolescent Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis. scipsy 2024, 5, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).