1. Introduction

A hypothetical chemical reaction, called the Combinatorial Fusion Cascade (CFC), has been recently proposed to explain the origin of the standard genetic code (SGC) [

1].

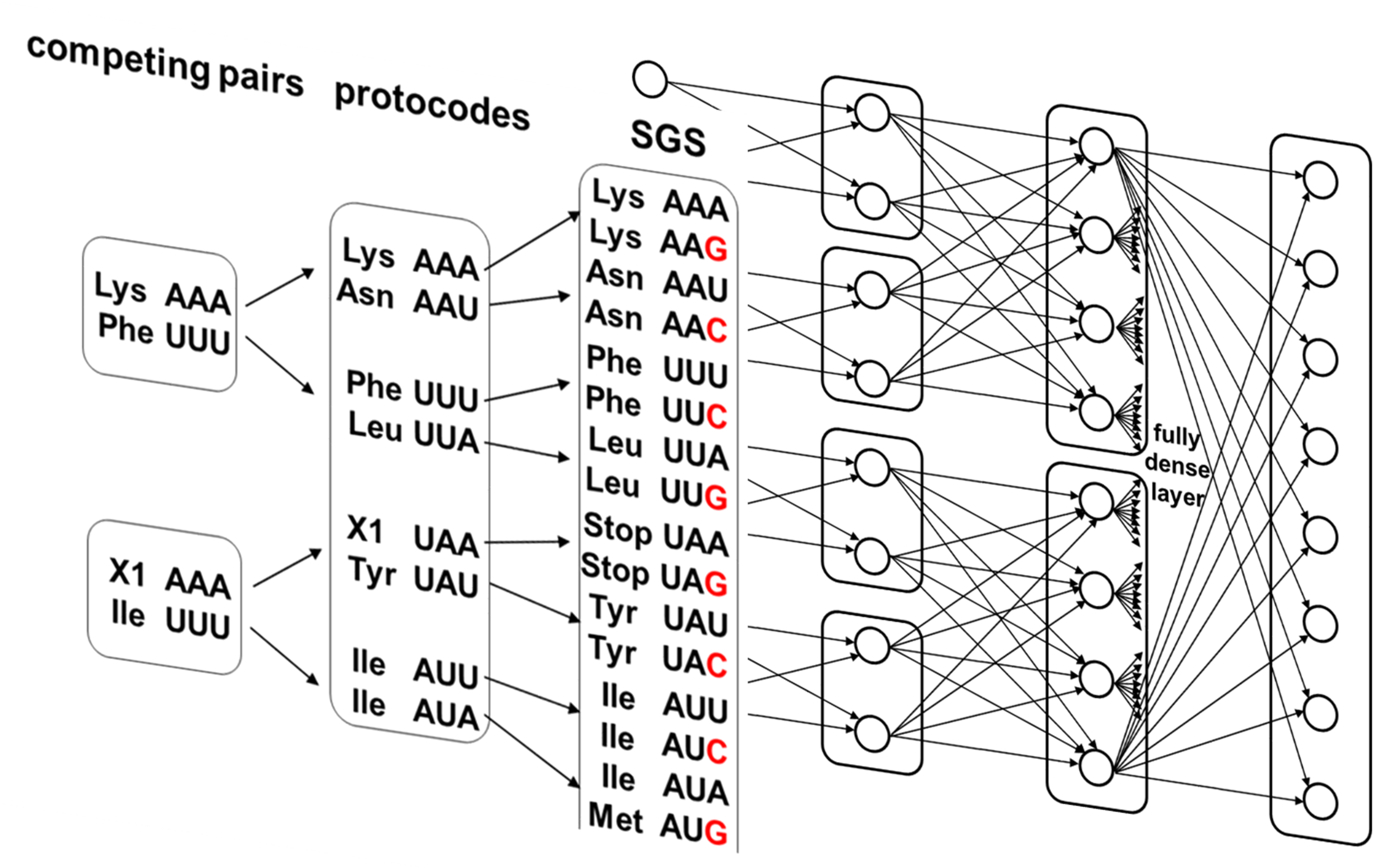

Figure 1a shows a half of the CFC to demonstrate how homogenous complementary coding triplets fused combinatorially to the protocodes at the first stage of the CFC and, accordingly, combinatorial fusion of protocodes results in the formation of the SGC. With unexpected simplicity, the CFC explains the distribution of amino acids among codons in the SGC, the appearance of stop codons, and some deviations from the standard genetic code in mitochondria that were not possible with any other approaches [

2].

This cascade-combinatorial fusion principle has inspired a number of innovative studies to explore the molecular basis for the different stages of the CFC closely connected with the origin of life. For example, peptide synthesis on short complementary RNA fragments has been demonstrated [

3]. M. Yarus, a renowned expert in the field of genetic code evolution, considered fusion as a process yielding hybrid routes to the SGC and summarized that efficient evolution occurs when code fusion is less prone to failure [

4]. The interactions between short RNA fragments and elongating peptide chains have been studied with an assumption of competing protocodes [

5]. The fact that the genetic code originated not from chaotic combinations of bases, but from homogenous triplets was attempted to be explained by reducing strand entropy during non-enzymatic replication [

6] or by the self-assembly of pure adenosine and pure uridine monophosphate strands on Montmorillonite clay [

7].

Viewing the CFC as a neural network reveals it as a cascade of interconnected multimodal subarchitectures, merging into progressively complex structures based on the same multimodal principle. This process culminates in a global layer that unifies all modalities into a single encoding layer.

Previously, the combinatorial cascade architecture did not attract practical attention, since in modern neural networks such as in image recognition tasks, layer convergence from a large number of nodes to a small number of outputs responsible for specific labels is required. This is necessary for the efficient adjustment of neural network weights through error backpropagation method [

8]. In contrast, CFC maintains or even increases the number of nodes as it advances to higher stages in the cascade.

Modular neural networks are recognized for their precise handling of subtasks, robustness, and fault tolerance [

9,

10]. As a distributed modular architecture, the CFC may therefore be particularly relevant to the development and application of artificial intelligence. Modularity also underlies human consciousness, when visual, auditory and other sensory signals are integrated by the neocortex into a single perception of the surrounding world.

This work explores the possibility of embedding the CFC into deep neural networks instead of sequential fully dense layers. Fully dense layers play a significant role in attention-based architectures, such as transformers [

11]. However, their training requires substantial computational resources and energy. Therefore, the search for more efficient neural architectures has become a pressing challenge. Additionally, the CFC, as a natural pattern underlying the origin of life, may be of interest for developing training methods that do not rely on error backpropagation.

2. Unique Characteristics of the CFC

The combinatorial cascade resembles growing m-ary trees (m ∈ ℕ), where branches form increasingly broad connections, ultimately resulting in a densely connected "crown." The CFC consists of 16 intertwined quaternary trees.

Table 1 shows the SGC elements at different stages of the cascade.

An important feature of the cascade is the complementarity of codons in entities. In particular, complementarity between hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids is built into SGC [

12].

In the SGC, less entropic codons are preserved and passed on to subsequent stages of the cascade (

Figure 1b, The coding of different databases is done in colors.): the inherited codons of the initial complementary pairs constitute ¼ of the codons at the protocode stage. Similarly, all codons from the protocode stage are inherited in the SGC and constitute ¼ of it. From the point of view of neural network connectivity, some signal patterns are transmitted in the cascade without change.

Another feature of the CFC is that the competition between amino acids (features) for codons at the initial stage of the cascade turns into degenerative coding of amino acids. If no new amino acids enter the cascade tree, then four different codons code for one amino acid in the SGC.

3. Methods

3.1. Implementation of the CFC in Neural Networks

The implementation of a combinatorial cascade in neural networks is shown schematically in

Figure 1c. This cascade ends with a fully dense matrix.

Dynamic mask method is used to simulate combinatorial cascade. The entire network can be represented as

Here is the standard matrix multiplication, f is the activation function, the element-wise product with the dynamic mask , the bias vector for layer ( = 1, 2, …, ).

A general form of

is expressed as a sum of diagonal matrices:

where

is the main diagonal of

filled with ones,

(for

k = 1,2, …,

d) the

k-th diagonal with ones on the

k-th off-diagonal both above and below the main diagonal. The all-ones matrix

corresponds the full dense connections.

The final output

after

layers is calculated as:

In combinatorial cascade dynamic matrix of size

, the sparsity increases progressively layer by layer, with the number of non-zero elements

k growing at each combinatorial cascade stage. It corresponds to the number of diagonals

filled with non-zero elements:

. If the number of non-zero diagonals increases progressively, for example, like a quaternary tree: 2, 8, 32, 128, etc, computational complexity of matrix multiplication

is estimated as:

The total computational complexity

across all

layers for the CFC network is:

3.2. CFC Laplace Matrix

The Laplacian matrix

is defined based on the graph’s adjacency matrix

and degree matrix

:

Here degree matrix

is a diagonal matrix with elements

that represent the number of edges connected to node i and adjacency matrix

is a symmetric matrix with elements

:

The Laplacian eigenvalues λ

i and eigenvectors

of the Laplacian matrix are calculated using the equation:

where

is identity matrix.

3.3. Python Codes

All data analysis were performed using Python, version 3.12.4. The Transformer-based text classifier was compiled with the Adam optimizer, a binary cross-entropy loss function, and accuracy as the evaluation metric (see provided Python codes). The Adam optimizer was chosen for its efficiency in handling sparse gradients and its proven effectiveness across a wide range of deep learning tasks. The optimizer was initialized using TensorFlow’s default configuration.

4. Results

4.1. Computational Complexity of the CFC

The total computational complexity

(5) grows exponentially with the increasing the number of diagonals with layer depth. However, it is still much smaller than total matrix calculation complexity

for fully dense matrices in earlier layers.

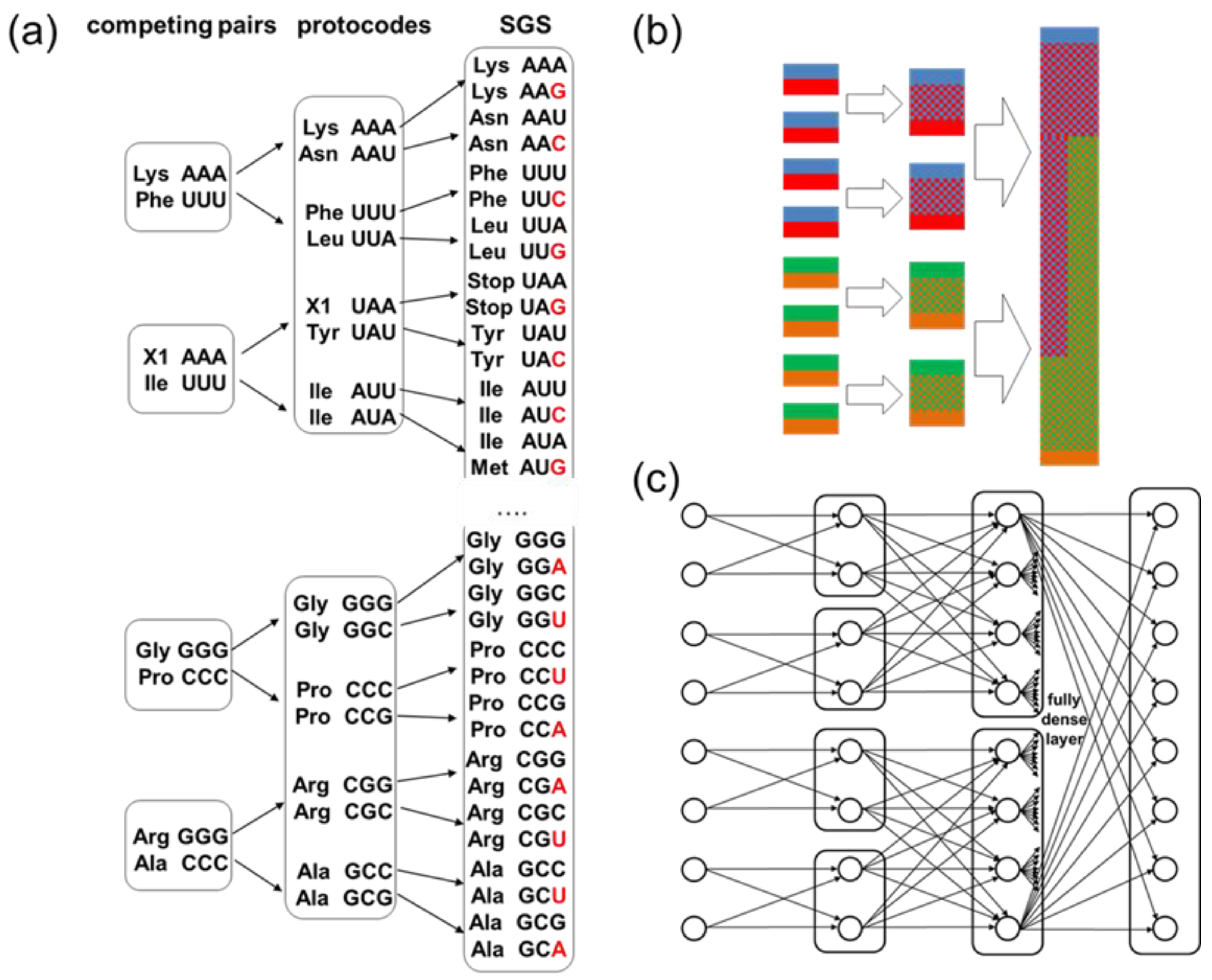

Figure 2 estimates the number of stages of a quaternary combinatorial cascade, in which the total complexity of matrix calculation reaches the total complexity of matrix calculation of a fully dense neural network. Since the number of layers is an integer, the function has a step-like character. It is characteristic that the number of CFC layers, at which the computational complexity of the CFC reaches the computational complexity of the corresponding fully dense neural network, can remain constant in a large range of the number of neurons. In particular, the quaternary combinatorial cascade, consisting of 7 layers, reaches the complexity of a fully connected neural network in a wide range from 500 to 1000 neurons in a layer.

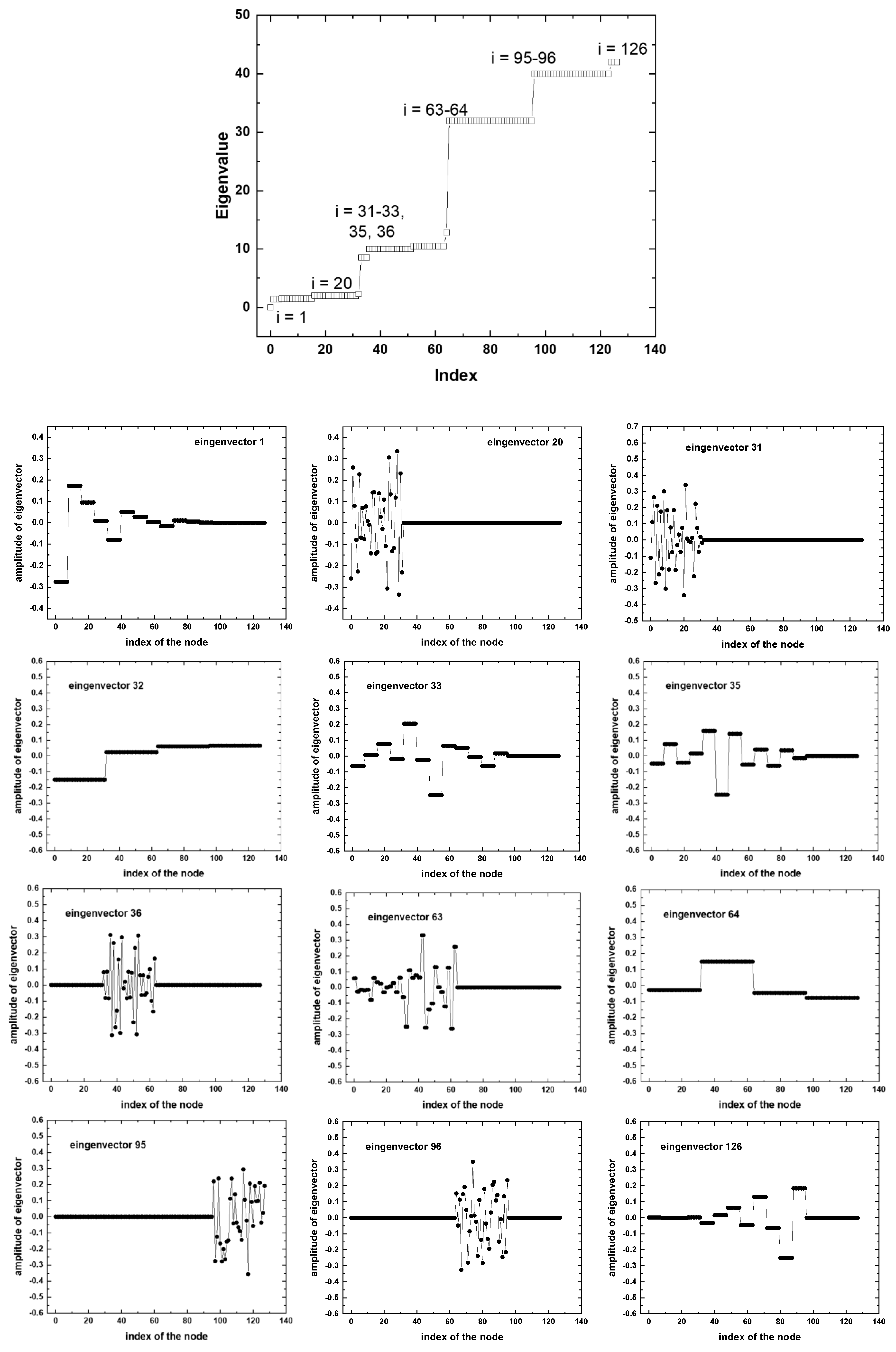

4.2. Spectral Properties of the CFC Laplace Matrix

To identify the spectral properties of the CFC, we examine a neural network with four layers, similar to the one shown in

Figure 1C, containing 32 neurons in each layer. The connectivity of the CFC network is described in

Table 2.

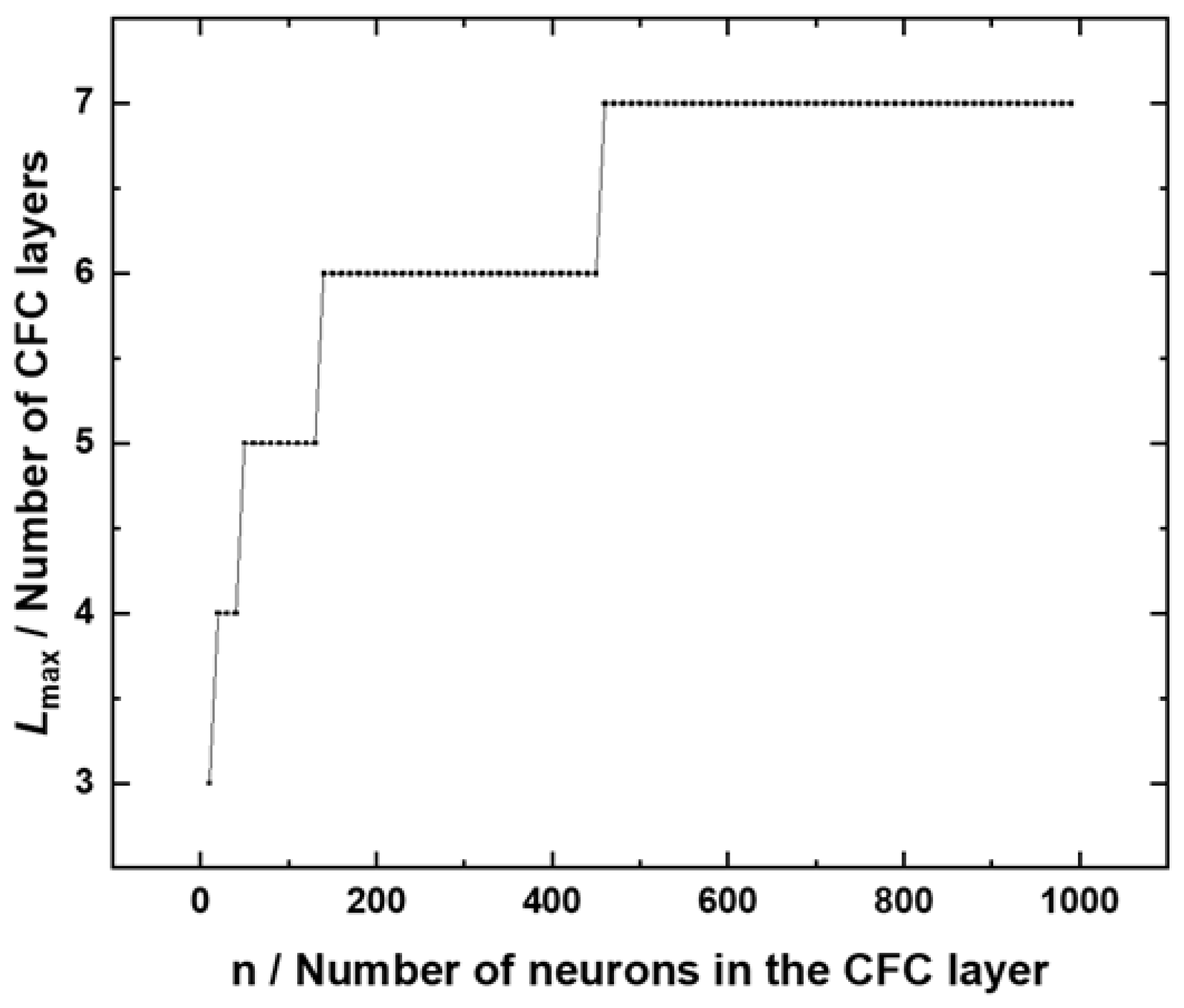

The eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the Laplace matrix for this neural network are compared with those of a fully connected four-layer neural network of the same size.

Figure 3 shows the Laplacian spectrum and some Laplacian eigenvectors for a fully dense neural network with four layers. Fiedler eigenvector [

13] (the first nontrivial eigenvector with index i = 1) shows the global structure of the neural network by identifying four clusters corresponding to the four layers. Using the analogy of connected vibrators, the behavior of the neural network’s Laplacian eigenvectors as their eigenvalue increases can be interpreted as the emergence of more energetic oscillatory vibration modes. The entire spectrum of Laplacian eigenvalues of a fully connected network is divided into two qualitatively different groups. At low vibration energies, the eigenvectors are localized in the region with smaller edges: this is the input and output layer. As the vibration energy of the network increases, the localization of the Laplacian eigenvectors moves to the middle of the neural network with a higher concentration of connections between nodes.

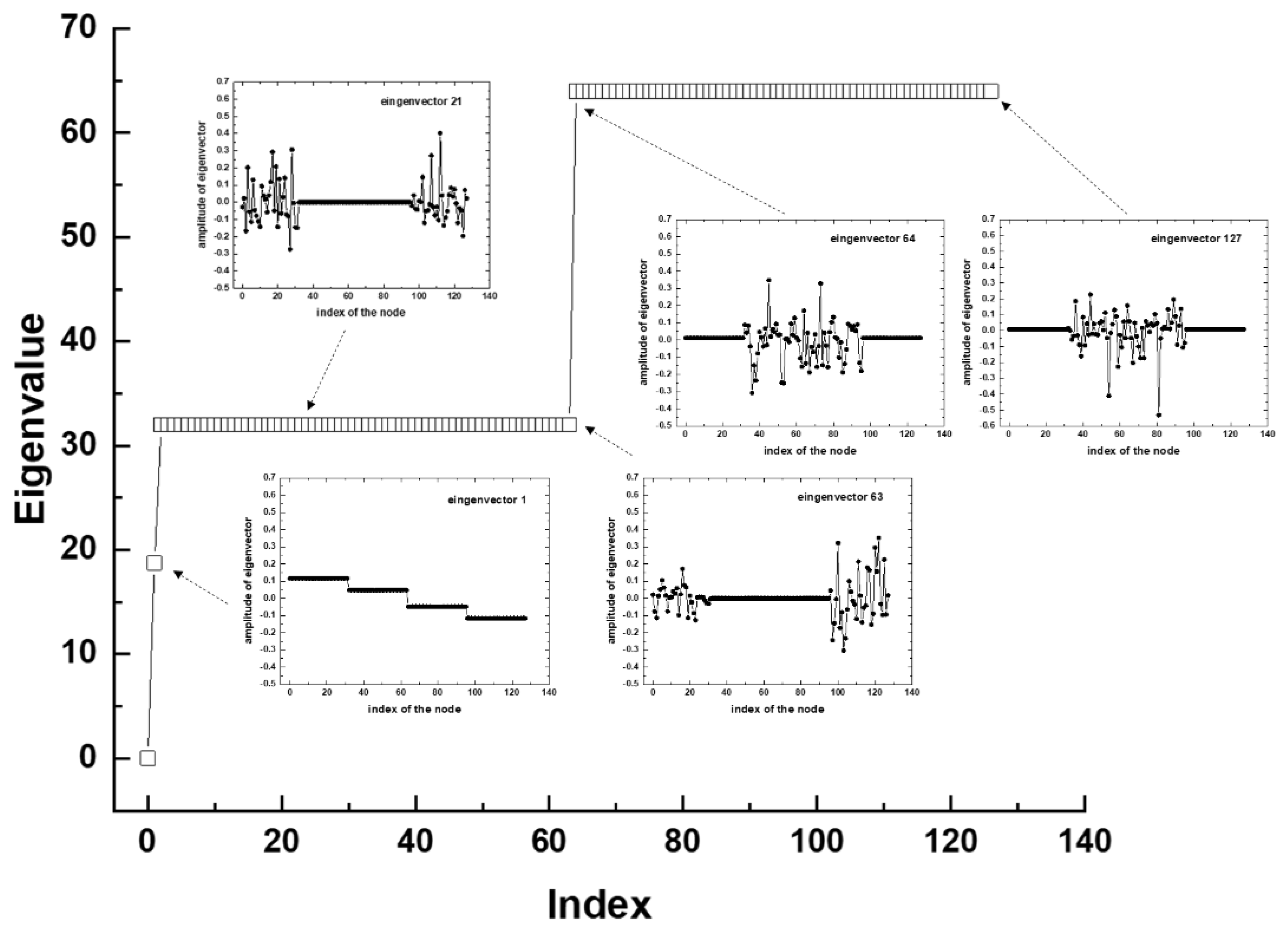

In the case of the CFC (

Figure 4), most of the eigenvectors have a similar complex beat shape as in the case of the fully connected neural network in

Figure 3. The localization of these eigenvectors shifts as the energy of the network oscillations increases from regions with lower to higher connectivity: input layer nodes (e.g. i = 20 and 31), first hidden layer nodes (e.g. i = 36), output layer nodes (e.g. i = 95) and second hidden layer nodes with the densest connectivity (e.g. i = 96).

The CFC network also has fundamental differences. The Fiedler vector of the CFC does not distinguish the cascade structure, but divides the network into 16 clusters (4 clusters per layer). Analogs of Fiedler eigenvectors appear at the junction of cascade layers (eingenvectros with i = 33, 35 in

Figure 4). It is interesting to note that Fiedler analogs also appear at maximum vibration energies of the neural network e.g. i = 126. Clustering according to the stages of the cascade (4 clusters) occurs with an energy significantly exceeding the energy of Fiedler mode. Only single cascade eigenvectors, not Fiedler eigenvector and its analogs, contrary to expectations, are distributed throughout the entire neural network.

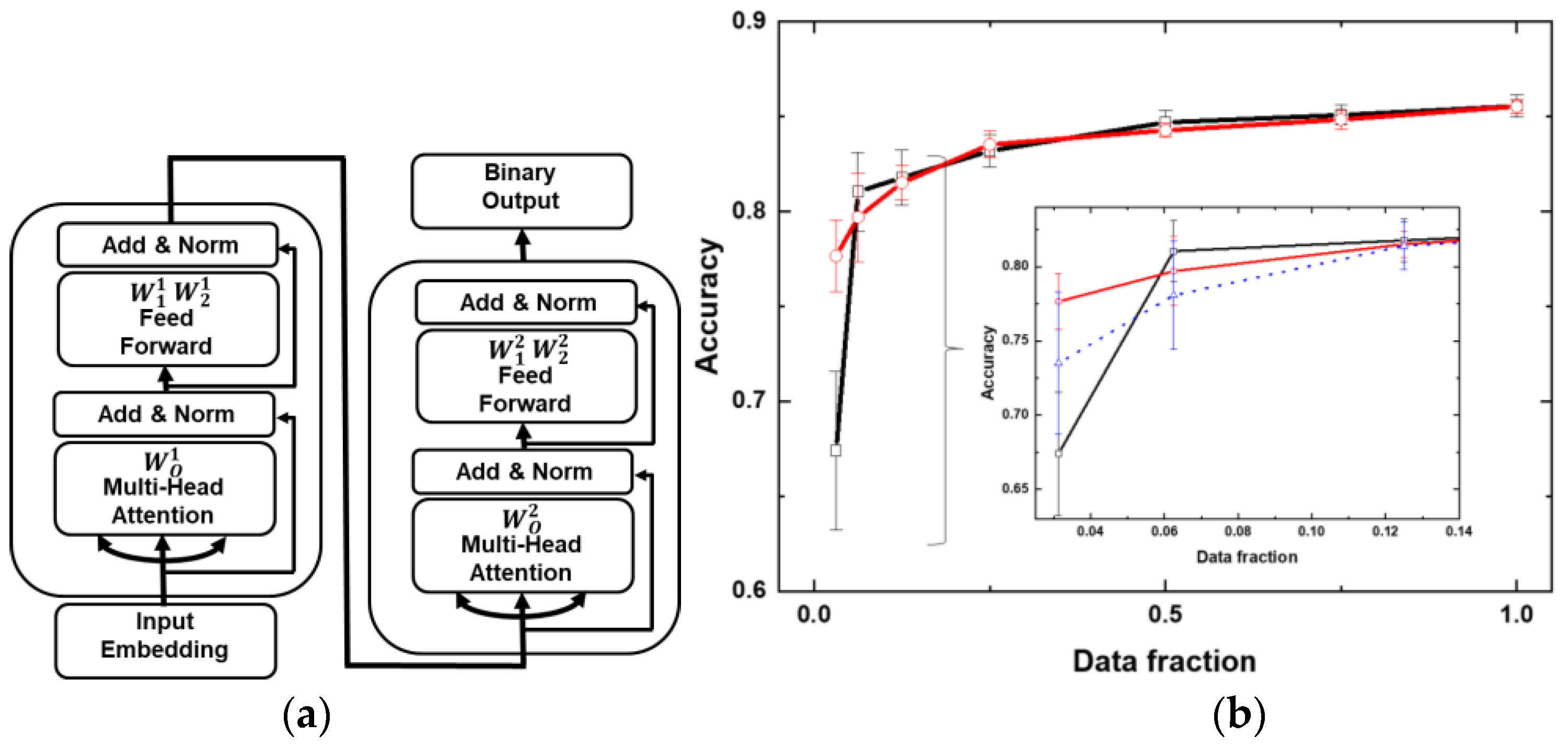

4.3. Combinatorial Cascade Architecture in Transformers

Fully connected layers are used extensively in Transformers, both in the multi-head attention (MHA) layers and in the feed-forward network (FFN) layers. The Transformer-based large-scale language models like GPT-3, which have billions of parameters, face a significant number of operations and increase in memory requirements. This is recognized as a serious bottleneck for the further development of large language models [

14]. Here we explore how a cascade architecture could influence the operation of Transformers by integrating it into a Transformer-based text classifier.

Figure 5a illustrates the architecture of a text classifier designed to evaluate the impact of the CFC architecture on its performance. The classifier uses the standard IMDB dataset [

15], embedding layer, two sequential transformers, and an output layer for binary sentiment classification. In the embedding, 25000 reviews are tokenized into numerical sequences, where each word is replaced by its corresponding index in a predefined vocabulary. Dimension of embedding matrix was 10000 x 128 (number of tokens x dimension of the model). To ensure consistent input length, sequences are padded or truncated to a fixed size. The transformer architecture incorporates key elements such as dropout layers, normalization, and residual connections (see supplementary materials for the Python code for the text classifier).

To implement the combinatorial cascade architecture, six matrices were selected: the fully dense projection matrix from the multi-head attention part of the first transformer, two fully dense matrices and from the feed-forward part of the first transformer, as well as analogous matrices from the second transformer: from the multi-head attention part and from the feed-forward block. The projection matrix plays a crucial role in aggregating information from multiple attention heads into a unified representation for each token. The feed-forward block matrices are essential for transforming the input data and extracting higher-level features. To these six matrices were applied six dynamic matrices the number of diagonals of which increased according to the binary cascade: 2, 4, 8, …, 128. For simplicity of implementation of the cascade architecture, the dimension of these matrices was taken 128x128. Thus, the last matrix of the cascade remained completely dense. The application of a binary cascade resulted in a reduction of two-thirds of the weights of all selected matrices.

Based on the fact that CFC has a cascade multimodality, by analogy, we multiplied the initial weights for the entire cascade of selected matrices by a factor decreasing in a binary geometric progression: 1, 1/2, 1/4, …, 1/32.

Figure 5b compares the accuracy for the text classifier with full-weight matrices and that with the built-in cascade and with cascaded weight reduction as a function of the number of reviews used for training. Overall, introducing the cascade did not significantly affect accuracy. However, a notable difference emerged when the number of training samples was reduced by a factor of 1/32 (781 reviews): while the standard text classifier experienced a substantial drop in accuracy, the classifier with the built-in cascade exhibited a more gradual decline. The average accuracy difference between the two cases was nearly 10%. It is also interesting to note that the standard deviation of accuracy in the case of a cascade text classifier was reduced more than twice. The inlet of figure 5b shows another dependence for accuracy (blue dashed line), for the case of a standard text generator with a cascade factor for initial weights. Of the three cases shown in figure 5b, the text classifier with a built-in connectivity cascade and a cascade factor for initial weights gives the greatest accuracy in the area of significant reduction of the number of samples for training.

Reducing the embedding matrix dimension by limiting the number of tokens to 1,000 (down from 10,000) during training on the full dataset did not result in a significant difference in accuracy for either the cascade or standard text classifiers. When the number of tokens was further reduced to 100, the accuracy dropped to 0.72, with no noticeable difference between the two text classifier types.

5. Discussion

The combinatorial diffusion cascade is a recently discovered natural pattern that has not been previously studied mathematically. Its effective descriptive power regarding the origin of the genetic code could indicate that CFC has a number of special properties that are interesting for applications in machine learning.

It turned out that the cascade partitioning of the neural network is not described by the Fiedler eigenvector, but is described by other vectors corresponding to more energetic excitations of the network. The Fiedler vector itself, however, divides the network into smaller fragments, and a partition similar to the Fiedler eigenvector is also found on other vectors with higher eigenvalues of the Laplace matrix. In contrast to the Fiedler eigenvector, its analogs (

Figure 4, eigenvectors with

i = 1, 33, 35, 126) and the eigenvectors of the neural network consisting of a sequence of fully connected matrices (

Figure 3), the cascade vectors are distributed throughout the entire network (see

Figure 4). Localized eigenvectors can be sensitive to small changes in the network or data, since they are concentrated in certain areas. In contrast, distributed vectors provide a more uniform representation, making the model more robust to noise, which could explain the particular stability of the cascaded text classifier in the case of a small set of training samples (

Figure 5b).

A significant influence of the cascade on the network behavior was observed during training on a reduced set of samples (about 3% of the initial one). The cascade architecture, despite its small share (сa. 4.5 %) in the total number of network parameters, turned out to be significantly more stable, yielding an average accuracy greater by 10% percent and a smaller standard deviation.

The decrease in the standard deviation in the case of a text classifier with a built-in cascade could be explained by a decrease in the Lipschitz constant that controls the sensitivity of the neural network to perturbations in its parameters [

16]. Since the total Lipschitz constant of a neural network is equal to the product of the Lipschitz constants for individual matrices [

17], the matrix with the highest sparsity is decisive for comparing the average deviation. The spectral norm of sparse masks is generally lower, which ensures a smaller standard deviation of accuracy in the case of random sets of initial weights.

Reducing the embedding dimension did not lead to a difference in accuracy between the standard classifier and the classifier with the built-in cascade when trained on the full IMDB dataset. This is surprising, since with an embedding matrix dimension of 100x128, the ratio of the weights of the matrices modified by the dynamic cascade becomes significant compared to the embedding weights. Probably, the number of samples is of great importance for accuracy. This property can be used for more effective strategies for training large language models.

Technically, there can be different forms of implementing a cascade on neural networks. For example, instead of a geometric progression, an arithmetic progression can be used to increase connectivity along the cascade. This could stretch the cascade to a large number of fully dense matrices of a large neural network. It is also not at all necessary for the cascade matrices to be square, as in the test classifier given in the article.

6. What Is Wrong with Backpropagation?

This question was asked by Geoffrey Hinton, exploring the possibilities of alternative methods of training neural networks [

18]. He noted that backpropagation is very effective, but fundamentally different from the work of the brain: “The brain needs a learning procedure that can learn on fly”, “without taking frequent timeouts”.

The dynamic matrix method used in this paper allows us to consider the neural network as a cascaded hyper network, when the parameters of the primary network are controlled by another matrix above them [

19]. Brain hyper network analysis has been widely applied in neuroimaging studies [

20,

21] . Some recent studies suggest that the brain complex integrative actions are assembled into the brain hyper network that has as fundamental components, the tetra-partite synapses, formed by neural, glial, and extracellular molecular networks [

22].

We have not used in this work a couple of interesting properties of CFC, which may be relevant for training a neural network without backpropagation. ¼ of the codes after merging competency entities are preserved. New codes formed as a result of combinatorics are divided between already existing or newly accepted into the genetic code amino acids. In essence, this means that two modal neural networks can be combined into one layer without additional training. Alternatively, the resulting new codons (connections) can be used to integrate new recognition functions into the network.

In the genetic code, a key element is codon complementarity, a property that is preserved at all stages of the cascade. A training with backpropagation based on two forward passes, working in the same way but with opposite objectives, was demonstrated by Hinton in the context of the forward-forward algorithm [

18]. In this approach, the positive pass adjusted the weights, increasing the goodness at each hidden layer, and the negative pass decreased the goodness at the same layers. Adjusting the weights using novel complementarity principles may replace the calculation of goodness, with the goal of reducing computations. Complementarity implies automatic knowledge of the entire code if half of it is known.

If an efficient training method could be found on a cascade architecture, then a cascade neural network as shown in

Figure 2 could achieve significant computational complexity in just a few neural layers due to the combinatorial explosion of cascade connections.

Funding

This research was funded by German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Protection, grant number KK5145204CR4.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

A.N.-M. acknowledges the Open Access Publishing Fund of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. A.N.-M. acknowledges the use of ChatGPT for enhancing Python code to implement formulas and neural networks in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nesterov-Mueller, A.; Popov, R. The Combinatorial Fusion Cascade to Generate the Standard Genetic Code. Life-Basel 2021, 11.

- Koonin, E.V.; Novozhilov, A.S. Origin and Evolution of the Universal Genetic Code. Annu Rev Genet 2017, 51, 45-62. [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.; Escobar, L.; Xu, F.; Wegrzyn, E.; Nainyte, M.; Amatov, T.; Chan, C.Y.; Pichler, A.; Carell, T. A prebiotically plausible scenario of an RNA-peptide world. Nature 2022, 605, 279-+. [CrossRef]

- Yarus, M. The Genetic Code Assembles via Division and Fusion, Basic Cellular Events. Life-Basel 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Jenne, F.; Berezkin, I.; Tempel, F.; Schmidt, D.; Popov, R.; Nesterov-Mueller, A. Screening for Primordial RNA-Peptide Interactions Using High-Density Peptide Arrays. Life-Basel 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kudella, P.W.; Tkachenko, A.V.; Salditt, A.; Maslov, S.; Braun, D. Structured sequences emerge from random pool when replicated by templated ligation. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2021, 118. [CrossRef]

- Himbert, S.; Chapman, M.; Deamer, D.W.; Rheinstädter, M.C. Organization of Nucleotides in Different Environments and the Formation of Pre-Polymers. Sci Rep-Uk 2016, 6. [CrossRef]

- Ackley, D.H.; Hinton, G.E.; Sejnowski, T.J. A Learning Algorithm for Boltzmann Machines. Cognitive Sci 1985, 9, 147-169.

- Amer, M.; Maul, T. A review of modularization techniques in artificial neural networks. Artif Intell Rev 2019, 52, 527-561. [CrossRef]

- Sabour, S.; Frosst, N.; Hinton, G.E. Dynamic routing between capsules. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017.

- Copley, S.D.; Smith, E.; Morowitz, H.J. A mechanism for the association of amino acids with their codons and the origin of the genetic code. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2005, 102, 4442-4447. [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, M. Algebraic Connectivity of Graphs. Czech Math J 1973, 23, 298-305.

- Minaee, S.; Mikolov, T.; Nikzad, N.; Chenaghlu, M.; Socher, R.; Amatriain, X.; Gao, J. Large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.06196 2024.

- Maas, A.L.; Daly, R.E.; Pham, P.T.; Huang, D.; Ng, A.Y.; Potts, C. Learning Word Vectors for Sentiment Analysis. Portland, Oregon, USA, June, 2011; pp. 142-150.

- Leino, K.; Wang, Z.; Fredrikson, M. Globally-robust neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2021; pp. 6212-6222.

- Khromov, G.; Singh, S.P. Some intriguing aspects about lipschitz continuity of neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.10886 2023.

- Hinton, G. The forward-forward algorithm: Some preliminary investigations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.13345 2022.

- Chauhan, V.K.; Zhou, J.D.; Lu, P.; Molaei, S.; Clifton, D.A. A brief review of hypernetworks in deep learning. Artif Intell Rev 2024, 57. [CrossRef]

- Arbabshirani, M.R.; Plis, S.; Sui, J.; Calhoun, V.D. Single subject prediction of brain disorders in neuroimaging: Promises and pitfalls. Neuroimage 2017, 145, 137-165. [CrossRef]

- Jie, B.; Wee, C.Y.; Shen, D.; Zhang, D.Q. Hyper-connectivity of functional networks for brain disease diagnosis. Med Image Anal 2016, 32, 84-100. [CrossRef]

- Agnati, L.F.; Marcoli, M.; Maura, G.; Woods, A.; Guidolin, D. The brain as a "hyper-network": the key role of neural networks as main producers of the integrated brain actions especially via the "broadcasted" neuroconnectomics. J Neural Transm 2018, 125, 883-897. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).