1. Introduction

Esophagitis, characterized by inflammation or damage to the esophageal mucosa, is a multifactorial condition with diverse etiologies. Among these, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a predominant cause, frequently resulting in erosive esophagitis. GERD arises from the repeated, abnormal reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus, leading to mucosal injury. The underlying pathophysiology involves reduced lower esophageal sphincter tone and increased transient relaxations, both of which facilitate acid reflux. In addition, structural abnormalities, such as hiatal hernias, further compromise esophageal sphincter integrity, increasing susceptibility to reflux-induced esophagitis [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Other contributing factors include impaired esophageal peristalsis and alterations in salivary composition, both of which weaken the protective mechanisms essential for esophageal mucosal integrity [

3,

4].

Histopathologically, GERD-related esophagitis is marked by characteristic changes, such as intercellular space dilation and infiltration of neutrophils and eosinophils [

5]. These inflammatory processes not only damage the mucosa but also overstimulate vagal nerve endings within the esophagus. Acid reflux and the resulting inflammation are known to enhance vagal activity, disrupting the autonomic balance. Emerging evidence suggests that this autonomic dysregulation may extend beyond the esophagus, influencing cardiac electrophysiology [

6,

7].

Non-invasive echocardiographic parameters have proven to be invaluable tools for predicting arrhythmias across various medical conditions. Atrial electromechanical delay (EMD), an echocardiographic marker, measures the time interval between the initiation of atrial electrical activity and subsequent myocardial contraction. Tissue Doppler imaging (TDI), a widely employed technique, enables precise quantification of EMD, making it a reliable metric for assessing the risk of atrial arrhythmias. Previous studies have established the clinical significance of atrial EMD in conditions such as myotonic dystrophy type 1, generalized anxiety disorders, chronic kidney disease, and obesity-hypoventilation syndrome [

6,

8,

9,

10].

The relationship between esophagitis and cardiac arrhythmias has been described in the literature, often framed within the context of Roemheld gastrocardiac syndrome. This phenomenon highlights the functional interplay between gastrointestinal and cardiac systems, whereby esophageal stimulation triggers cardiac symptoms, including arrhythmias. However, despite the established role of GERD in modulating autonomic activity, the impact of esophagitis on atrial electromechanical properties, particularly EMD, remains unexplored [

11,

12,

13].

This study aims to investigate atrial EMD in patients with esophagitis using TDI. By examining intra- and interatrial EMD and correlating these parameters with esophagitis severity, this research seeks to elucidate the potential role of esophagitis in the pathophysiology of atrial arrhythmias. Findings from this study could provide novel insights into the cardiac implications of esophagitis, emphasizing the need for interdisciplinary management of these patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

The study involved 60 patients admitted to the gastroenterology outpatient clinic, suspected of having gastroesophageal reflux based on medical history and physical examination, and diagnosed with esophagitis via endoscopy. An endoscopy was indicated and conducted by a gastroenterologist. Patients diagnosed with esophagitis during endoscopy were classified using the Los Angeles classification system [

14].

Individuals under 18 years, tobacco users, those with renal failure, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes, thyroid hormone disorders or any hormonal disorders, heart failure, valvular heart disease, coronary artery disease, malignancy, active infections or inflammatory diseases (or both), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a history of alcohol abuse, were taking medications that affect cardiac conduction, had documented cardiac arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, ventricular pre-excitation, or atrioventricular conduction abnormalities, or did not provide consent to participate. Furthermore, individuals with a prior diagnosis of esophagitis who were undergoing follow-up treatment were excluded from the study. Thirty healthy volunteers of comparable age and gender who presented at the outpatient clinic were included as a control group in the study. Initially, all participants received a comprehensive cardiovascular and systemic examination, and demographic data were documented.

2.2. Echocardiographic Assessment

Experienced echocardiographers, lacking knowledge of the clinical specifics of each participant, conducted transthoracic echocardiographic assessments utilizing the Vivid E95® cardiac ultrasonography system (GE VingMed Ultrasound AS; Horten, Norway) with 2.5- to 5-MHz transducers. A 2D, M-mode, pulsed, and color flow Doppler echocardiography examination was performed on each patient in the left lateral and supine postures. A single-lead electrocardiogram was continually monitored. The average of a minimum of three cardiac cycles was obtained for all measures. The assessment of M-mode data and conventional Doppler echocardiography was based on the standards established by the European Society of Echocardiography [

15]. Doppler tracings and two-dimensional pictures were acquired from the parasternal long and short axes, as well as the apical and subcostal perspectives. The diameters of the left and right atria, as well as the end-systolic and end-diastolic dimensions of the left ventricle (LV), and the diastolic thicknesses of the LV posterior and septal walls were measured. Left atrial volumes were measured utilizing the disc method, whereas Simpson's formula was employed to estimate left ventricular ejection fraction (EF). Mitral inflow velocities, namely peak E (early diastolic) and peak A (late diastolic), together with the E/A ratio, were utilized for the assessment of left ventricular diastolic function. Additionally, the deceleration time of the E-wave (DT) and isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT) were employed. All echocardiographic pictures were evaluated by a seasoned cardiologist who was unaware of the research details.

2.3. Tissue Doppler Echocardiography (TDE)

The pulsed Doppler sample volume was positioned at the LV lateral mitral annulus, septal mitral annulus, and RV tricuspid annulus using an apical four-chamber view. The time interval from the onset of the P-wave on surface ECG to the beginning of the late diastolic wave (Am), referred to as PA, was measured at the lateral mitral annulus (PA lateral), septal mitral annulus (PA septal), and RV tricuspid annulus (PA tricuspid) (

Figure 1). The distinction between PA septum and PA tricuspid (PA septum − PA tricuspid) was recognized as intra-atrial electromechanical delay, whereas the difference between PA lateral and PA tricuspid (PA lateral − PA tricuspid) was recognized as interatrial electromechanical delay [

16,

17,

18].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data management and analysis were conducted using SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with a two-sided p-value of ≤0.05 deemed statistically significant. Categorical variables were assessed using percentages and case counts, whereas continuous variables were represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR). An independent sample t-test was employed to compare means, while the Mann–Whitney U test was utilized for cases with abnormal distribution, focusing on the median. A chi-square test was employed for the categorical data analysis. Spearman correlation analysis was employed for abnormally distributed variables, while Pearson correlation was utilized for normally distributed variables. A p-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

3. Results

The demographic, clinical, and echocardiographic characteristics of the study groups are summarized in

Table 1. The esophagitis group comprised 60 patients, with a mean age of 44 ± 8, compared to 38 ± 6 years in the control group (p = 0.484). The gender distribution was comparable between the two groups (p = 0.551). Similarly, other baseline characteristics, such as the presence of hypertension (p = 0.324) and heart rate (p = 0.652), did not differ significantly. Echocardiographic parameters, including left atrial (LA) diameter, left ventricular (LV) dimensions, LV mass, and LV ejection fraction (LVEF), were also similar between the groups (p > 0.05).

Among the patients with esophagitis, disease severity was classified using the Los Angeles classification system. A total of 27 patients were categorized as grade A, while 33 were classified as grade B. Notably, three patients in the grade B subgroup were also diagnosed with hiatal hernia, a structural abnormality known to exacerbate esophageal reflux and mucosal damage.

3.1. Atrial Electromechanical Delay

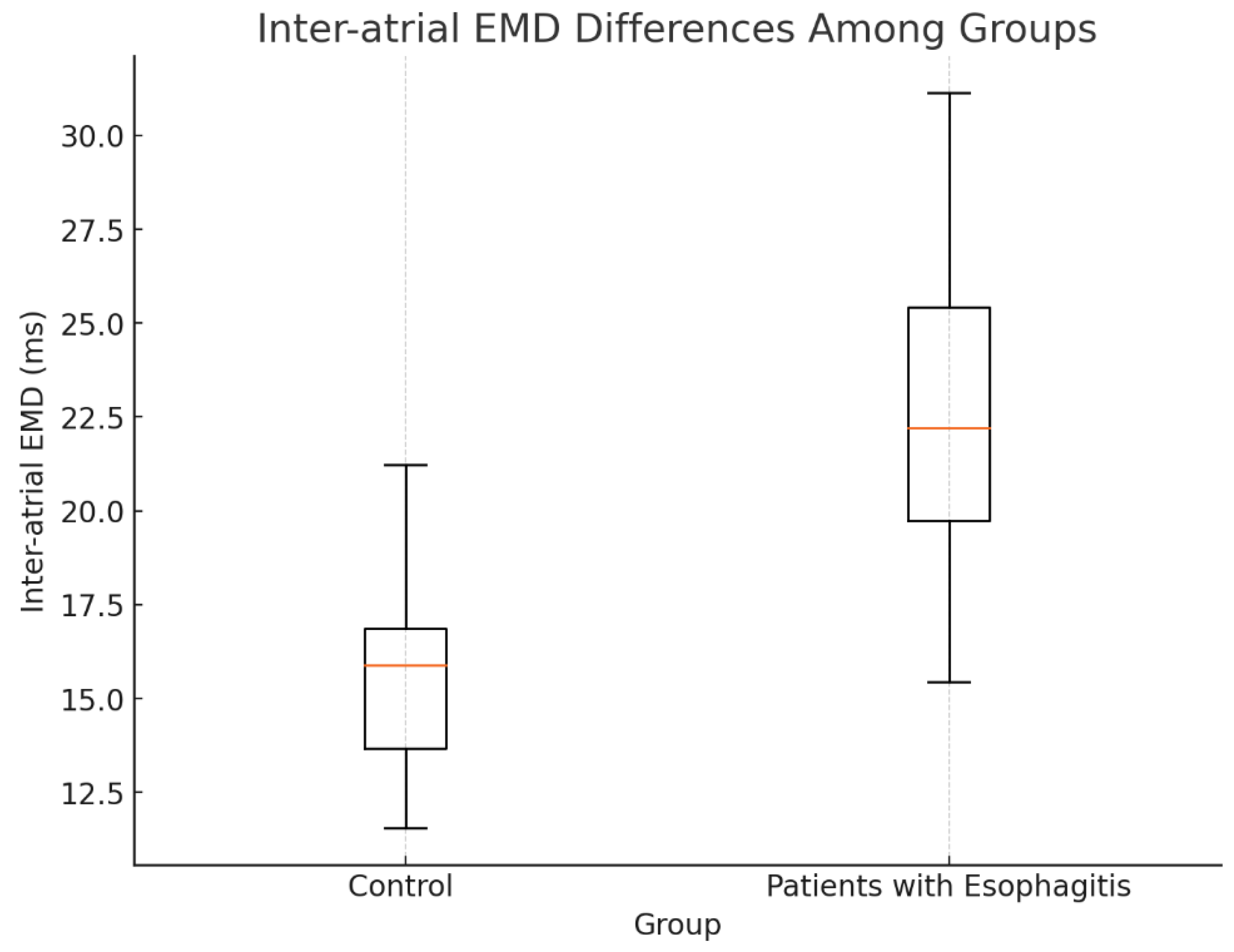

The atrial electromechanical delay (EMD) parameters measured by tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) are presented in

Table 2. Patients with esophagitis exhibited significant prolongation in lateral PA (62.1 ± 6.2 ms) and PA septum (52.3 ± 5.1 ms) compared to controls (54.9 ± 7.3 ms, p < 0.01 and 44.5 ± 4.6 ms, p = 0.027, respectively). Inter-atrial EMD, defined as the difference between PA lateral and PA tricuspid, was significantly prolonged in the esophagitis group (22.6 ± 6.4 ms) relative to controls (15.8 ± 4.7 ms, p < 0.01). Similarly, intra-atrial EMD, calculated as the difference between PA septum and PA tricuspid, was longer in patients with esophagitis (12 ms [IQR: 4–15.2]) compared to controls (5 ms [IQR: 2–9], p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Comparison of the Atrial Electromechanical Coupling Parameters Measured by Tissue Doppler Imaging.

Table 2.

Comparison of the Atrial Electromechanical Coupling Parameters Measured by Tissue Doppler Imaging.

| |

Patients with Esophagitis |

Control |

|

| |

n:60 |

n:30 |

p |

| PA Lateral (msec) |

62.1 ± 6.2 |

54.9 ± 7.3 |

<0.01 |

| PA Septum (msec) |

52.3 ± 5.1 |

44.5 ± 4.6 |

0.027 |

| PA Tricuspid (msec) |

43.2 ± 6.5 |

39.3 ± 5.6 |

0.434 |

| Inter-atrial EMD (msec) |

22.6 ± 6.4 |

15.8 ± 4.7 |

<0.01 |

| Intra-atrial EMD (msec) |

12 (4-15.2) |

5 (2-9) |

<0.01 |

Figure 2.

Interatrial EMD differences among groups.

Figure 2.

Interatrial EMD differences among groups.

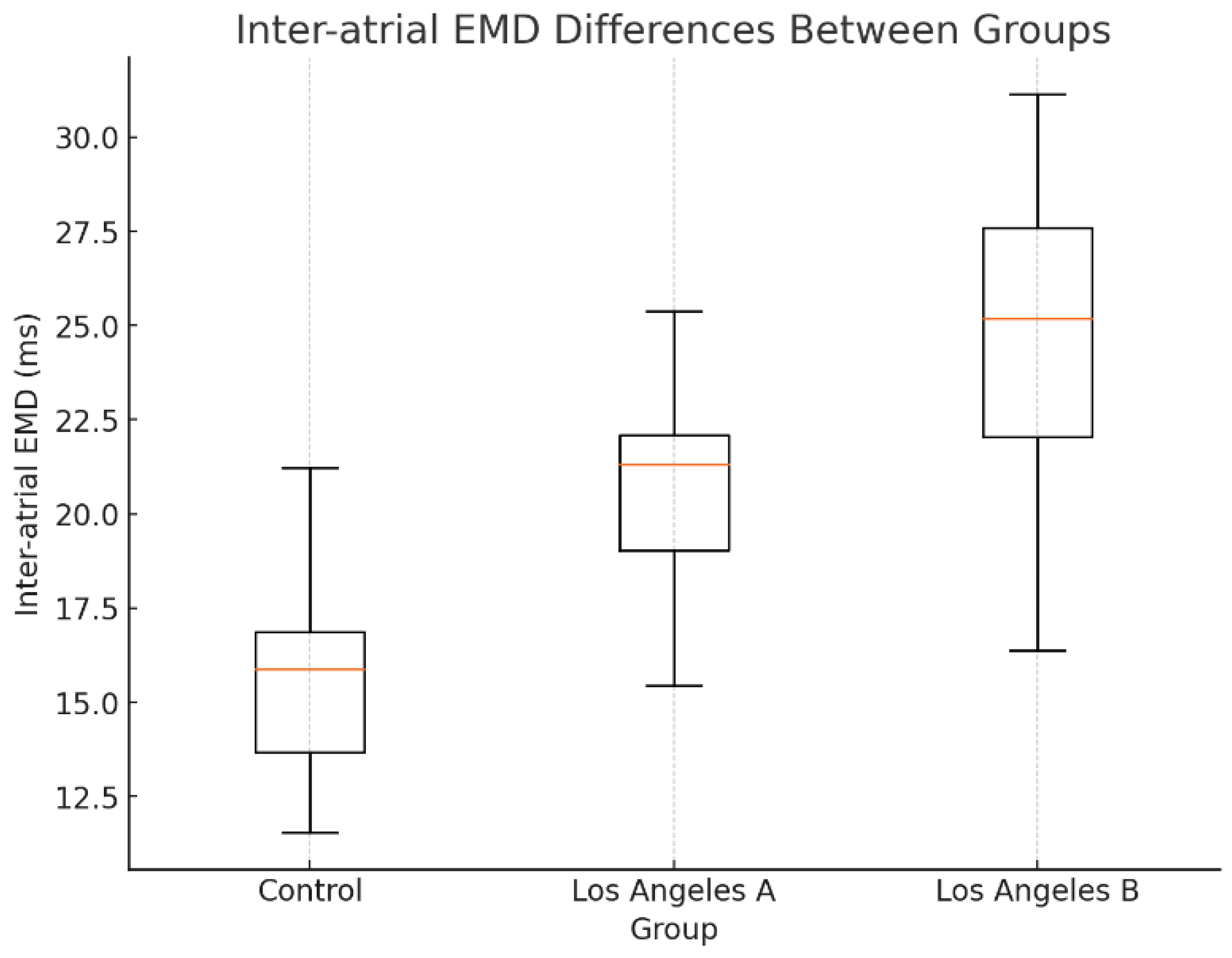

3.2. Subgroup Analysis by Disease Severity

A subgroup analysis based on the Los Angeles classification revealed that EMD parameters were further prolonged in patients with grade B esophagitis compared to those with grade A. Specifically, inter-atrial EMD was significantly elevated in grade B patients, suggesting a correlation between esophagitis severity and electromechanical delay (

Figure 3). This observation aligns with the hypothesis that chronic inflammation and structural changes in the esophagus exert greater influence on atrial conduction times in more severe cases.

4. Discussion

This study provides novel insights into the relationship between esophagitis and atrial electromechanical delay (EMD), revealing significantly prolonged EMD parameters in patients with esophagitis compared to healthy controls. These findings highlight a crucial link between gastrointestinal inflammation and cardiac conduction abnormalities, underscoring the need for integrated clinical approaches to managing these patients.

4.1. Mechanisms Linking Esophagitis and Atrial Electromechanical Delay

4.1.1. Vagal Stimulation and Autonomic Dysregulation

One of the primary mechanisms underlying prolonged EMD in esophagitis is heightened vagal stimulation triggered by acid reflux. Esophageal acid exposure irritates the mucosal lining, overstimulating vagal afferents and disrupting autonomic balance. Previous studies have demonstrated that heightened vagal tone is associated with arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation (AF), even in patients without structural cardiac disease [

19,

20,

21].

In addition, the autonomic influence of GERD on cardiac electrophysiology is well-documented. Roemheld gastrocardiac syndrome, described as arrhythmogenic responses to esophageal and gastric stimuli, exemplifies this interplay [

22,

23]. Similarly, Paterson et al. demonstrated that esophageal pH abnormalities were correlated with episodes of atrial tachyarrhythmias, further supporting the role of autonomic dysregulation in esophagitis-related arrhythmias [

24]. Our findings expand on this concept by showing that vagally mediated prolongation of atrial EMD may be an early manifestation of this gastrointestinal-cardiac interaction.

4.1.2. Chronic Inflammation and Cytokine Release

Beyond autonomic factors, chronic inflammation plays a pivotal role in EMD prolongation. Persistent esophageal inflammation, driven by repeated acid exposure, leads to the systemic release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [

25,

26,

27]. These cytokines have been implicated in atrial remodeling and the pathogenesis of arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation.

For instance, IL-6 and CRP levels are strongly correlated with increased arrhythmogenic risk and adverse cardiac outcomes in population studies [

28,

29]. These inflammatory mediators disrupt myocardial architecture by promoting atrial fibrosis, delaying electrical conduction, and increasing EMD [

30,

31]. Moreover, experimental models, such as those by Fernández-Sada et al., have shown that inflammatory cytokines can induce ventricular arrhythmias and contractile dysfunction, emphasizing the systemic impact of localized inflammation [

32]. In the context of esophagitis, this inflammatory cascade may similarly extend to atrial tissues, promoting electromechanical dissociation.

4.1.3. Fibrosis and Structural Remodeling

Chronic inflammation also drives structural changes in atrial tissues, particularly fibrosis. Fibrotic remodeling disrupts the uniform conduction of electrical signals across the atria, prolonging EMD and increasing the risk of arrhythmias. Kobayashi et al. demonstrated that systemic inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis patients is associated with myocardial fibrosis, detected via cardiac MRI [

31]. Similarly, studies on atrial fibrillation suggest that fibrosis is a major contributor to conduction delays and arrhythmogenesis [

32,

33]. In our study, the prolonged inter- and intra-atrial EMD observed in esophagitis patients likely reflects these fibrotic processes, exacerbated by chronic esophageal inflammation.

4.1.4. Hiatal Hernia and Mechanical Effects

In three of our patients with grade B esophagitis, hiatal hernia was identified as a comorbid condition. Hiatal hernias mechanically compress the left atrium, further disrupting electrical conduction. Duygu et al. linked large paraesophageal hernias to persistent atrial fibrillation, attributing the association to both mechanical and inflammatory factors [

34]. Mechanical pressure on atrial tissues can impair electrical coupling, while the proximity of the hernia to the esophagus amplifies inflammatory cross-talk, compounding the risk of arrhythmias [

35,

36].

4.2. Clinical Implications

The findings of this study suggest that prolonged EMD may serve as an early marker for arrhythmic risk in patients with esophagitis. Identifying these subclinical conduction abnormalities has several clinical implications:

Screening and Monitoring: Patients with chronic esophagitis, particularly those with grade B severity or hiatal hernia, should be evaluated for arrhythmogenic risk using tissue Doppler imaging or other non-invasive modalities.

Interdisciplinary Management: Collaboration between gastroenterologists and cardiologists is essential to optimize care for these patients. Addressing esophageal inflammation through medical or surgical interventions may reduce arrhythmic complications.

Prognostic Value: The role of EMD in predicting long-term outcomes, such as the development of atrial fibrillation or ventricular arrhythmias, warrants further exploration.

4.3. Study Limitations

This study is limited by its cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inference. Longitudinal follow-up is necessary to determine whether prolonged EMD predicts future arrhythmic events in this population. Additionally, the modest sample size and lack of advanced imaging modalities, such as cardiac MRI, limited our ability to assess atrial fibrosis directly. Finally, the absence of diastolic function parameters may have underestimated the overall cardiac impact of esophagitis.

4.4. Future Directions

To build on these findings, future studies should: Conduct Longitudinal Cohort Studies: Investigate the temporal relationship between EMD prolongation and arrhythmia development.Explore Therapeutic Interventions; evaluate the impact of anti-inflammatory or autonomic modulation therapies on EMD and arrhythmic outcomes. Utilize Advanced Imaging; incorporate cardiac MRI or three-dimensional echocardiography to assess atrial structural remodeling in esophagitis patients. Examine comorbidities; investigate the synergistic effects of comorbid conditions, such as hiatal hernia and obesity, on EMD and cardiac outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant prolongation of atrial electromechanical delay in patients with esophagitis, likely mediated by vagal stimulation, systemic inflammation, and fibrotic remodeling. These findings reinforce the importance of interdisciplinary care and early monitoring in this population. Future research should aim to elucidate the prognostic and therapeutic implications of EMD prolongation in esophagitis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.Y. and M.K.; data curation, E.C., H.G. and M.A.; formal analysis, M.K. and O.Y.; funding acquisition, O.Y. and H.G.; investigation, H.C.S., K.E. and M.A.; methodology, M.K., O.Y.; project administration, M.K. and O.Y.; resources, M.K. and O.Y.; software, M.K. and E.C; supervision, M.K. and O.Y..; validation, H.G.; visualization, M.K. and E.C.; writing—original draft, O.Y. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, O.Y. and H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Izmir Tepecik University of Health Sciences (ethical code; 2024/07-10).

Informed Consent Statement

The authors of the dataset declared that informed consent from the patients or their authorized guardians was obtained before data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Richter, J.E. Gastrooesophageal reflux disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2007, 21, 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fass, R.; Boeckxstaens, G.E.; El-Serag, H.; Rosen, R.; Sifrim, D.; Vaezi, M.F. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2021, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, C.P.; Yadlapati, R.; Fass, R.; Katzka, D.; Pandolfino, J.; Savarino, E.; et al. Updates to the modern diagnosis of GERD: Lyon consensus 2.0. Gut 2024, 73, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, C.; Kang, J.Y.; Neild, P.J.; Maxwell, J.D. The role of the hiatus hernia in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 20, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieder, F.; Cheng, L.; Harnett, K.M.; Chak, A.; Cooper, G.S.; et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease-associated esophagitis induces endogenous cytokine production leading to motor abnormalities. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, G.A. Vagal modulation of cardiac ventricular arrhythmia. Exp. Physiol. 2014, 99, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.A.; Miller, S.A.; Corsello, B.F. Acid-induced esophagobronchial-cardiac reflexes in humans. Gastroenterology 1990, 99, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temiz, F.; Güneş, H.; Güneş, H. Evaluation of atrial electromechanical delay in children with obesity. Medicina 2019, 55, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, H.; Sokmen, A.; Kaya, H.; Gungor, O.; Kerkutluoglu, M.; Guzel, F.B.; Sokmen, G. Evaluation of atrial electromechanical delay to predict atrial fibrillation in hemodialysis patients. Medicina 2018, 54, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokmen, A.; Acar, G.; Sokmen, G.; Akcay, A.; Akkoyun, M.; et al. Evaluation of atrial electromechanical delay and diastolic functions in patients with hyperthyroidism. Echocardiography 2013, 30, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, W.; Abdollah, H.; Beck, I.; Da Costa, L. Ambulatory esophageal manometry, pH-metry, and Holter ECG monitoring in patients with atypical chest pain. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1993, 38, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brembilla-Perrot, B.; Marcon, F.; Bosser, G.; Lucron, H.; Houriez, P.; Claudon, O.; et al. Paroxysmal tachycardia in children and teenagers with normal sinus rhythm and without heart disease. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2001, 24, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerson, L.; Friday, K.; Triadafilopoulos, G. Potential relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and atrial arrhythmias. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2006, 40, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundell, L.R.; Dent, J.; Bennett, J.R.; et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: Clinical and functional correlations and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut 1999, 45, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Bierig, M.; Devereux, R.B.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Pellikka, P.A.; Picard, M.H.; Roman, M.J.; Seward, J.; Shanewise, J.S.; et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: A report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2005, 18, 1440–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, G.; Sayarlioglu, M.; Akcay, A.; Sokmen, A.; Sokmen, G.; Altun, B.; Nacar, A.B.; Gunduz, M.; Tuncer, C. Assessment of atrial electromechanical coupling characteristics in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Echocardiography 2009, 26, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilgin, M.; Yıldız, B.S.; Tülüce, K.; Gül, İ.; Alkan, M.B.; Sayın, A.; İslamlı, A.; Efe, T.H.; Alihanoğlu, Y.İ.; Zoghi, M.; et al. Evaluating functional capacity and mortality effects in the presence of atrial electromechanical conduction delay in patients with systolic heart failure. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2016, 16, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokmen, A.; Acar, G.; Sokmen, G.; Akcay, A.; Akkoyun, M.; Koroglu, S.; Nacar, A.B.; Ozkaya, M. Evaluation of atrial electromechanical delay and diastolic functions in patients with hyperthyroidism. Echocardiography 2013, 30, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, G.A. Vagal modulation of cardiac ventricular arrhythmia. Exp. Physiol. 2014, 99, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.A.; Miller, S.A.; Corsello, B.F. Acid-induced esophagobronchial-cardiac reflexes in humans. Gastroenterology 1990, 99, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerson, L.; Friday, K.; Triadafilopoulos, G. Potential relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and atrial arrhythmias. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2006, 40, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, S.S.; Roth, G.A.; Gillum, R.F.; Mensah, G.A. Global burden of atrial fibrillation in developed and developing nations. Glob. Heart. 2014, 9, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Luscher, T.F. Anti-inflammatory therapies for cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 1782–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, W.; Abdollah, H.; Beck, I.; Da Costa, L. Ambulatory esophageal manometry, pH-metry, and Holter ECG monitoring in patients with atypical chest pain. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1993, 38, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieder, F.; Cheng, L.; Harnett, K.M.; Chak, A.; Cooper, G.S.; et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease-associated esophagitis induces endogenous cytokine production leading to motor abnormalities. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, C.M.; Ma, J.; Rifai, N.; Stampfer, M.J.; Ridker, P.M. Prospective study of C-reactive protein, homocysteine, and plasma lipid levels as predictors of sudden cardiac death. Circulation 2002, 105, 2595–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Sada, E.; Torres-Quintanilla, A.; Silva-Platas, C.; García, N.; Willis, B.C.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, C.; et al. Proinflammatory cytokines are soluble mediators linked with ventricular arrhythmias and contractile dysfunction in a rat model of metabolic syndrome. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 7682569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.K.; Shah, A.M.; Giugliano, R.P.; Ruff, C.T.; Antman, E.M.; Braunwald, E.; et al. C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Insights from the TOPCAT trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Bierig, M.; Devereux, R.B.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Pellikka, P.A.; et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: A report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2005, 18, 1440–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundell, L.R.; Dent, J.; Bennett, J.R.; et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: Clinical and functional correlations and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut 1999, 45, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yokoe, I.; Akashi, Y.; Takei, M.; Giles, J.T. Magnetic resonance imaging-detected myocardial inflammation and fibrosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2017, 69, 1304–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, V.; Andrie, R.P.; Rudolph, T.K.; Friedrichs, K.; Klinke, A.; Hirsch-Hoffmann, B.; et al. Myeloperoxidase acts as a profibrotic mediator of atrial fibrillation. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nattel, S.; Harada, M. Atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation: Recent advances and translational perspectives. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 2335–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duygu, H.; Ozerkan, F.; Saygi, S.; Akyuz, S. Persistent atrial fibrillation associated with gastroesophageal reflux and hiatal hernia. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2008, 8, 164–165. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, R.J.; Kaye, G.C. Paroxysmal atrial flutter suppressed by repair of a large paraesophageal hernia. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1998, 21, 1303–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilgin, M.; Yıldız, B.S.; Tülüce, K.; Gül, İ.; Alkan, M.B.; Sayın, A.; İslamlı, A.; Efe, T.H.; Alihanoğlu, Y.İ.; Zoghi, M.; et al. Evaluating functional capacity and mortality effects in the presence of atrial electromechanical conduction delay in patients with systolic heart failure. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2016, 16, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).