1. Introduction

Historically, the volatility of financial time series has been treated in two ways. The first approach is parametric and postulates a latent variable via conditional heteroscedastic models to describe the volatility, such as the ARCH (Autoregressive Conditional Heterocedasticity) family models proposed by [

10] and the stochastic volatility models, proposed by [

18]. There is a huge literature on this approach and for details, see, for example, [

17,

21].

The main motivation for using the nonparametric approach is because parametric models often fail to adequately capture the movements of intraday volatility, see [

1]. A nonparametric approach consists of constructing the daily realized volatility (RV) of a financial series using intraday returns, sampled at intervals

, of the order of 5 or 15 minutes, for example. RV is obtained from sums of squares of intraday returns, see [

1] and [

6]. Another method is to construct the realized bi-power variance (RVBP), from the sums of cross products of absolute adjacent, properly scaled returns, see [

7]. For details, see [

5]. [

7,

12] and [

2] derived test statistics for detecting the existence of jumps. Other authors established tests for the necessity of adding a Brownian force, see [

3,

14,

16,

20] and [

19]. [

4] studied whether the jump component is of finite activity when the Brownian force is present.

In recent years, efforts have been devoted to study the distribution function of test statistics in the presence of jumps. [

15] studied whether it is necessary to add an infinite variation jump term in addition to a continuous local martingale, using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) type test statistic. [

8] derived the exact and asymptotic distribution of Cramér-von mises statistic when the empirical distribution function is a uniform distribution function. [

20] suggested using other measures of discrepancy between distributions, as the Cramér-von mises test for the presence of diffusion component in a process

which usually represents the price (or log-prices) of some financial asset. These studies motivated us to propose a test statistic using a Cramér-Von Mises type statistic.

It would be important to obtain the distribution of our proposed test statistic in the presence of jumps, however this is not an easy task, so we will employ numerical methods to approximate this distribution.

The paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2 we establish the set up for our problem, define the hypotheses of interest and discuss the choice of the proposed test statistic.

Section 3 discuss an approximation to the true distribution of the statistics, whereas

Section 4 presents a simulation study to assess its performance.

Section 5 applies our proposed test statistic to real data and

Section 6 concludes with comments on the usefulness of the proposed methodology and on recommendations for future works.

2. Setup

The standard jump-diffusion model used for modeling many stochastic processes is given by the following differential equation:

where

and

are processes with càdlàg paths,

is a standard Brownian motion, and

is an Itô semimartingale process of pure-jump type. [

20] generalized Eq. (

1) to accommodate the alternative hypothesis that

can be of pure-jump type. Itô semimartingale plays an important role in stochastic calculus and the following model plays a major role.

Suppose that

follows a non-parametric volatility model

where

is a continuous Itô semimartingale, that is,

where

is the drift term with

being an optional and càdlàg process,

is a continuous local martingale with

being an adapted process,

is a standard Brownian motion, and

is a skewed

-stable Lévy process.

[

15] provided a theoretical test for the presence of infinite variation jumps in the simultaneous presence of a diffusion term and a jump component of finite variation and established the asymptotic theory of the empirical distribution of the “devolatilized" increments of Itô semimartingale with infinitely active or even infinite variation jumps. There are other methods to estimate the spot volatility, see, for instance, [

20] and [

11].

Recently, [

9] discussed a volatility functional model and showed that jumps asymptotically impact the volatility estimate and presented a jump detection model based on wavelets.

We now consider the following hypotheses

where

denotes the

ith one-step increment for

and we assume that the available data set

are discretely equally spaced variables sampled from

, in the fixed interval

, i.e.,

with

for

. The empirical process is given by:

for a finite sample size

n,

and

are some integer depending on

n,

should be smaller than

,

should be smaller than

and

denotes the integer part. Here,

denotes the distribution function (df) of a standard normal random variable and

is the empirical distribution function (edf) of the devolatilized increments. We used the local estimator proposed by [

20] to estimate

. On each of the blocks the local estimator of

is given by

which is the bipower variation for measuring the quadratic variation of the diffusion component of

. [

20] removed the high-frequency increments that contain big jumps. The total number of increments used in their statistic is thus given by

where

and

. They use a time-varying threshold in the truncation to account for the time varying

. The scaling of every high-frequency increment is done after adjusting

to exclude the contribution of that increment in its formation:

Then, they define

which is simply the edf of the devolatilized increments that do not contain any big jumps. In the jump-diffusion case of Eq. (

1),

should be approximately the df of a standard normal random variable. [

20] use an alternative estimator of the volatility that is the truncated variation defined as

where

and, the corresponding one excluding the contribution of the

ith increment for

, is

The edf of the devolatilized (and truncated) increments is given by,

where

. Here, the total number of increments is defined as

We define the test statistic as:

where

A is a compact set in

and

. Here,

is an edf and we assume that

is the df of a standard normal random variable and use the notation

for it. So, we have

The critical region for the test is given by

where

A is a compact set in

and

is the

-quantile of the distribution of the statistic. We evaluate

via simulation. The test rejects

if

. The main purpose is to develop a test statistic that has better statistical properties than the existing KS test statistic for identifying jump variations in high-frequency time series. We will use the notation

and

for

when using Eqs. (

6) and (

9), respectively. To determine the critical region of the test we will perform extensive simulations, using the R language, version

. All data and codes are available upon request to the authors.

2.1. Performance of Test Statistics

The idea is to observe which test statistic performs better using the two df mentioned in the previous section. A simulation was performed with

replications and different

n,

and

values, as shown in the following panel.

| n |

|

|

, , , , , , , , |

| |

, , , , ,

|

|

, , , , , , ,

|

| |

, , , , , ,

|

| |

, , , , ,

|

|

, , , , , , ,

|

| |

, , , , , , , |

| |

, , , , , ,

|

| |

, , , , , ,

|

| |

, , , , . |

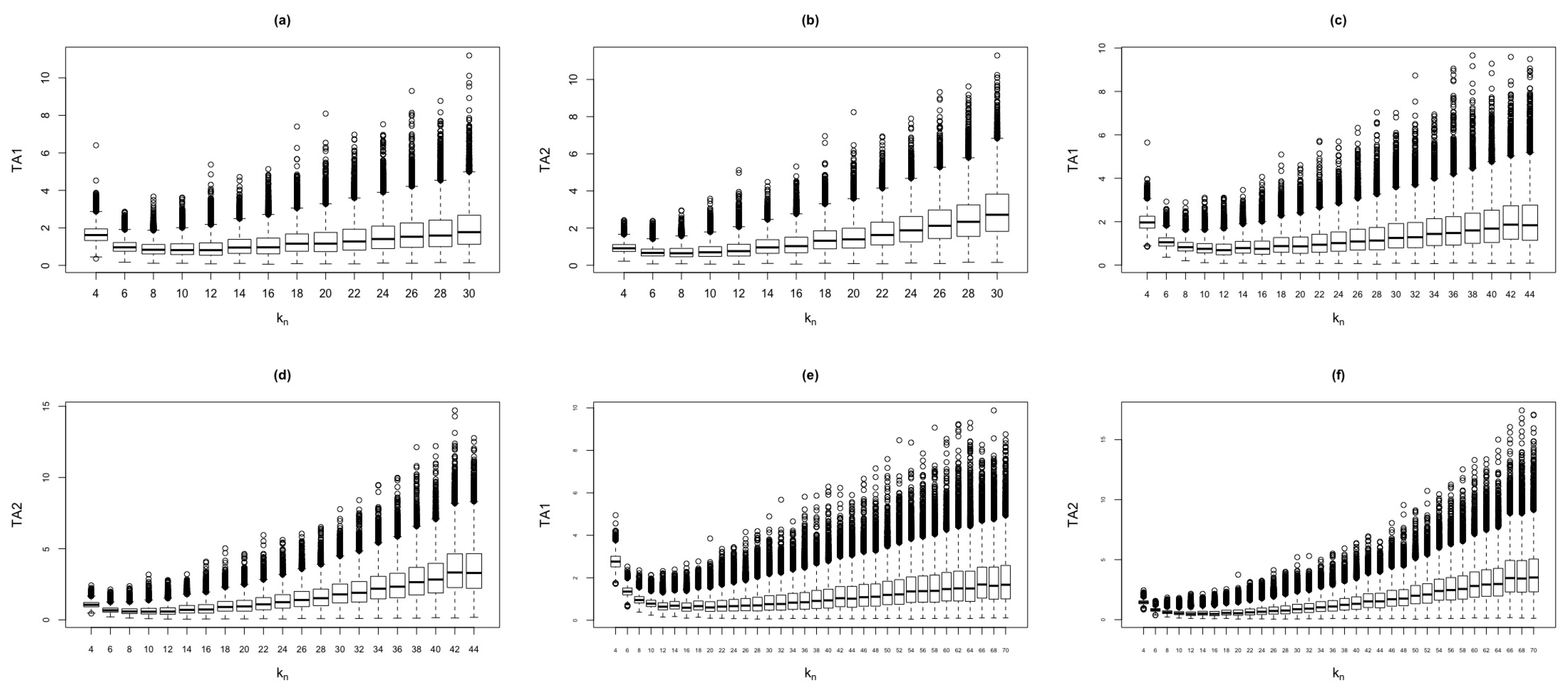

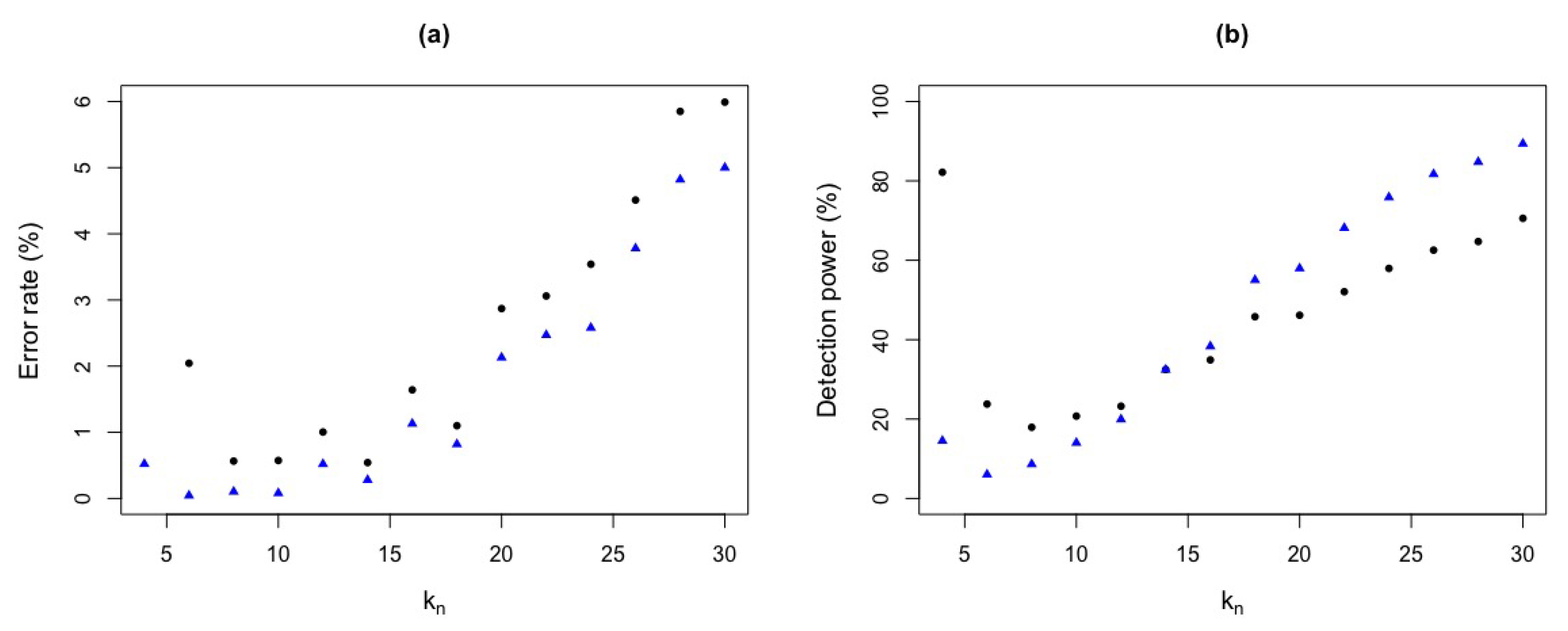

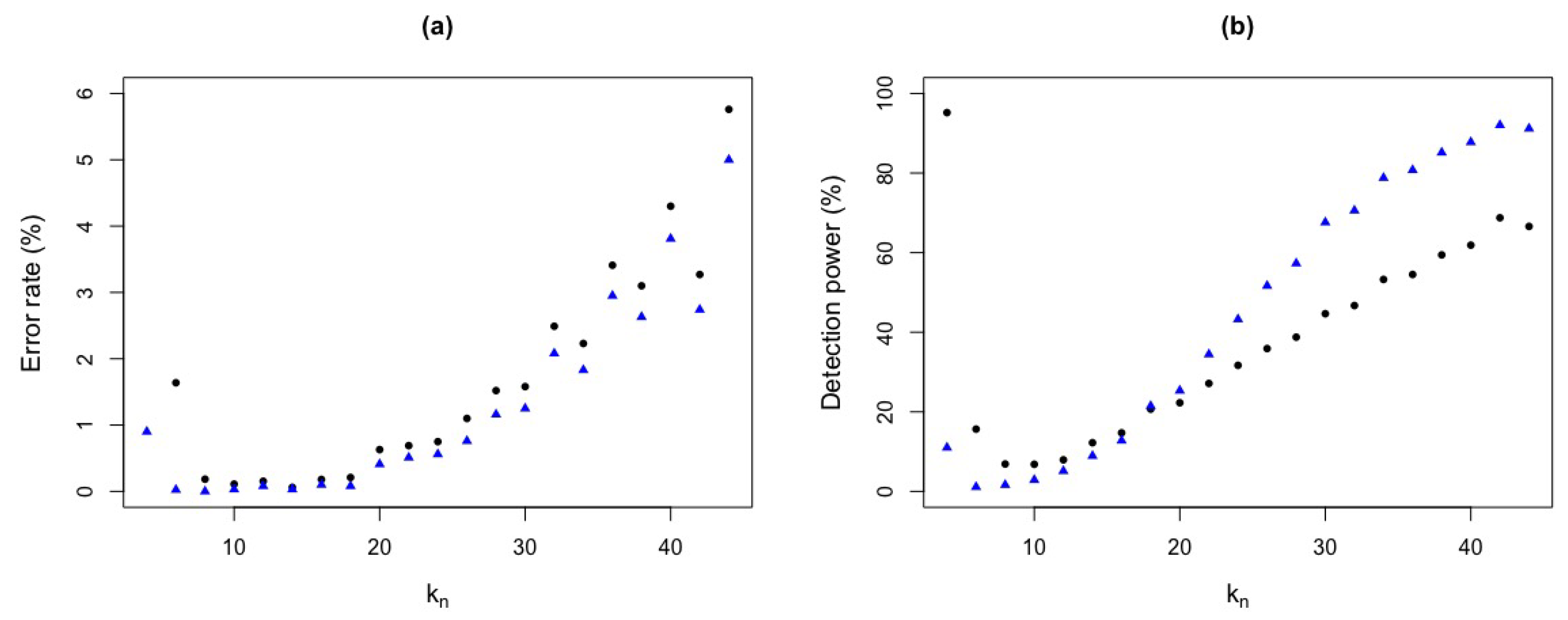

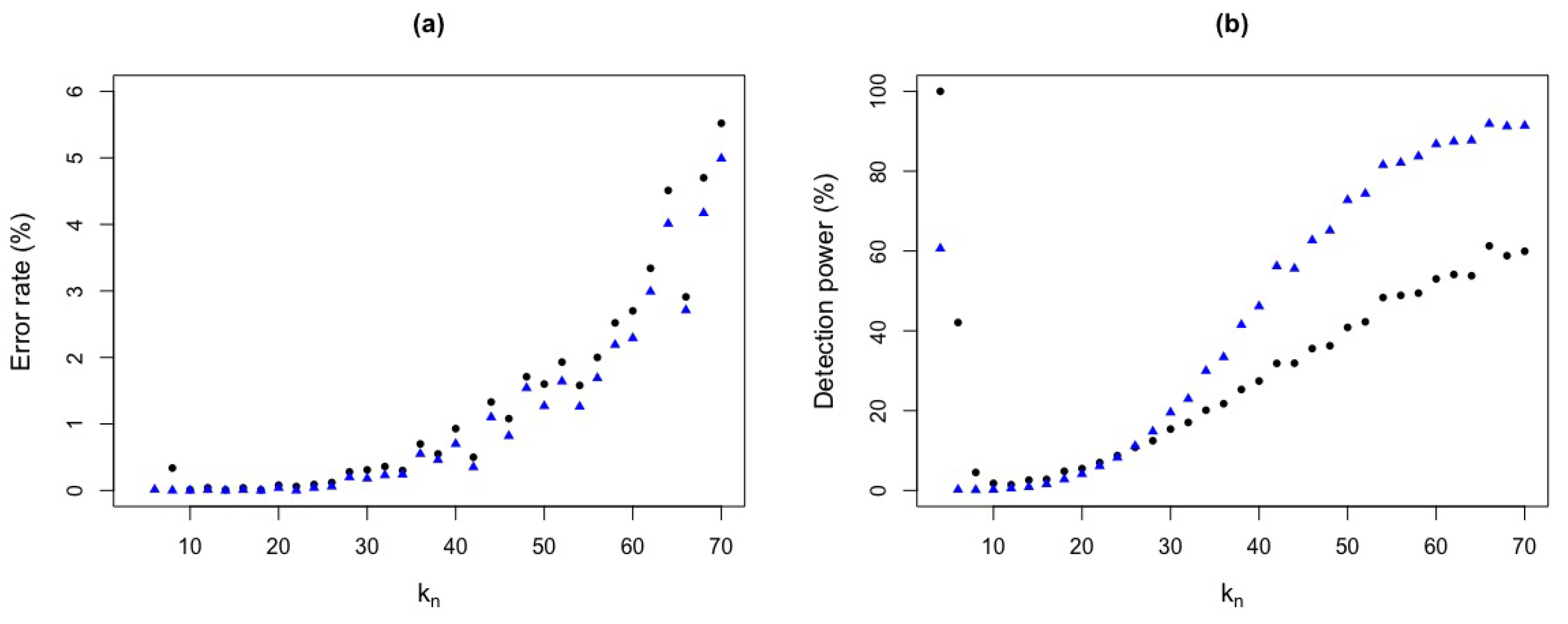

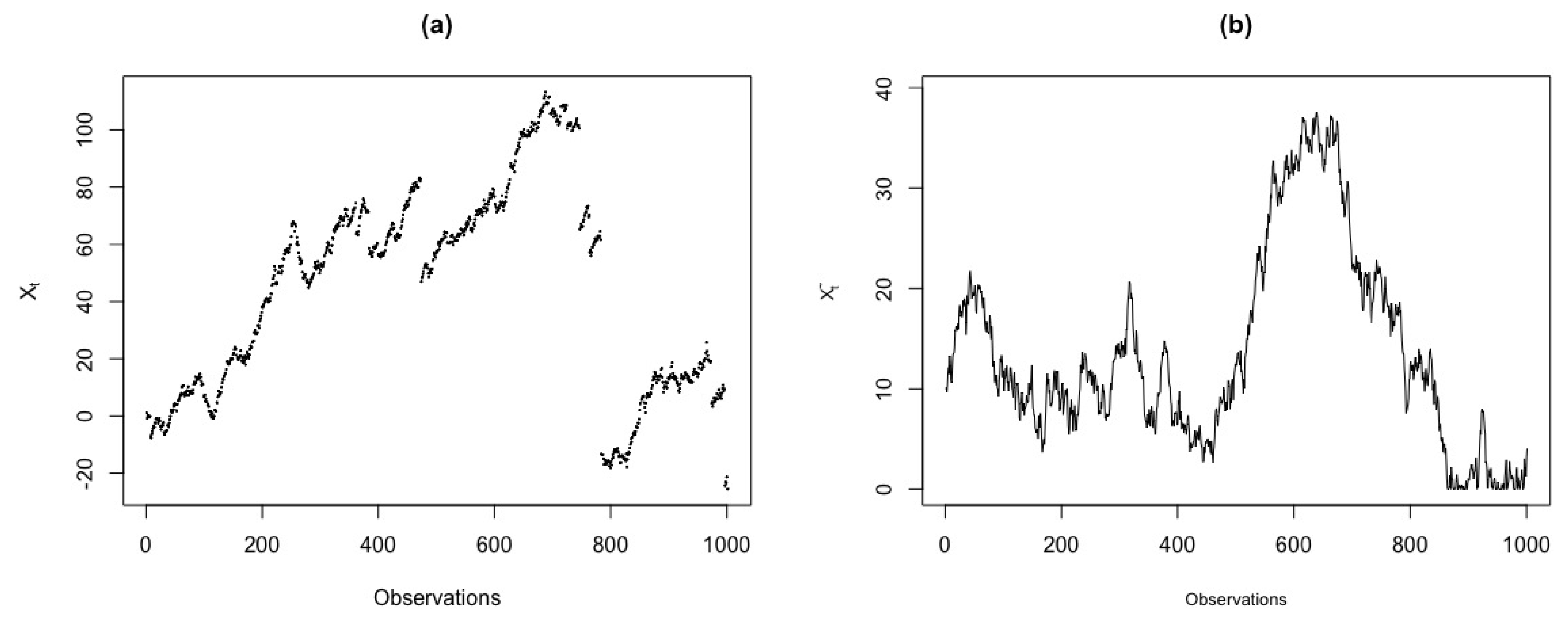

Figure 1 shows the behavior of

and

test statistics against

, for the jump-diffusion model. From the plots, we observe the existence of outliers. Also, the values of

and

test statistics increase as

increases. In cases where

and

, the values of the test statistics present some inconsistencies.

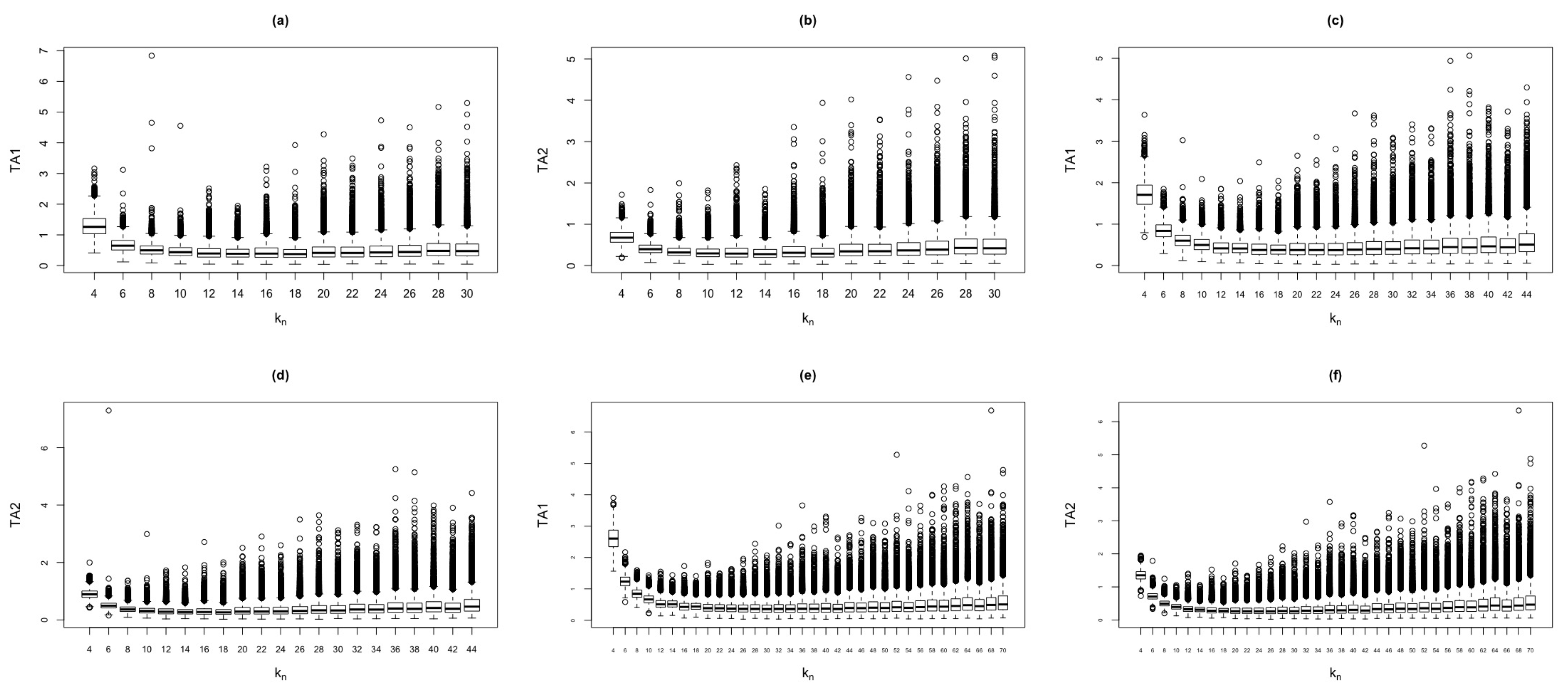

Figure 2 shows the behavior of

and

test statistics against

, for the standard normal model.

The first simulations were based on

replicas with

and the same pairs of

and

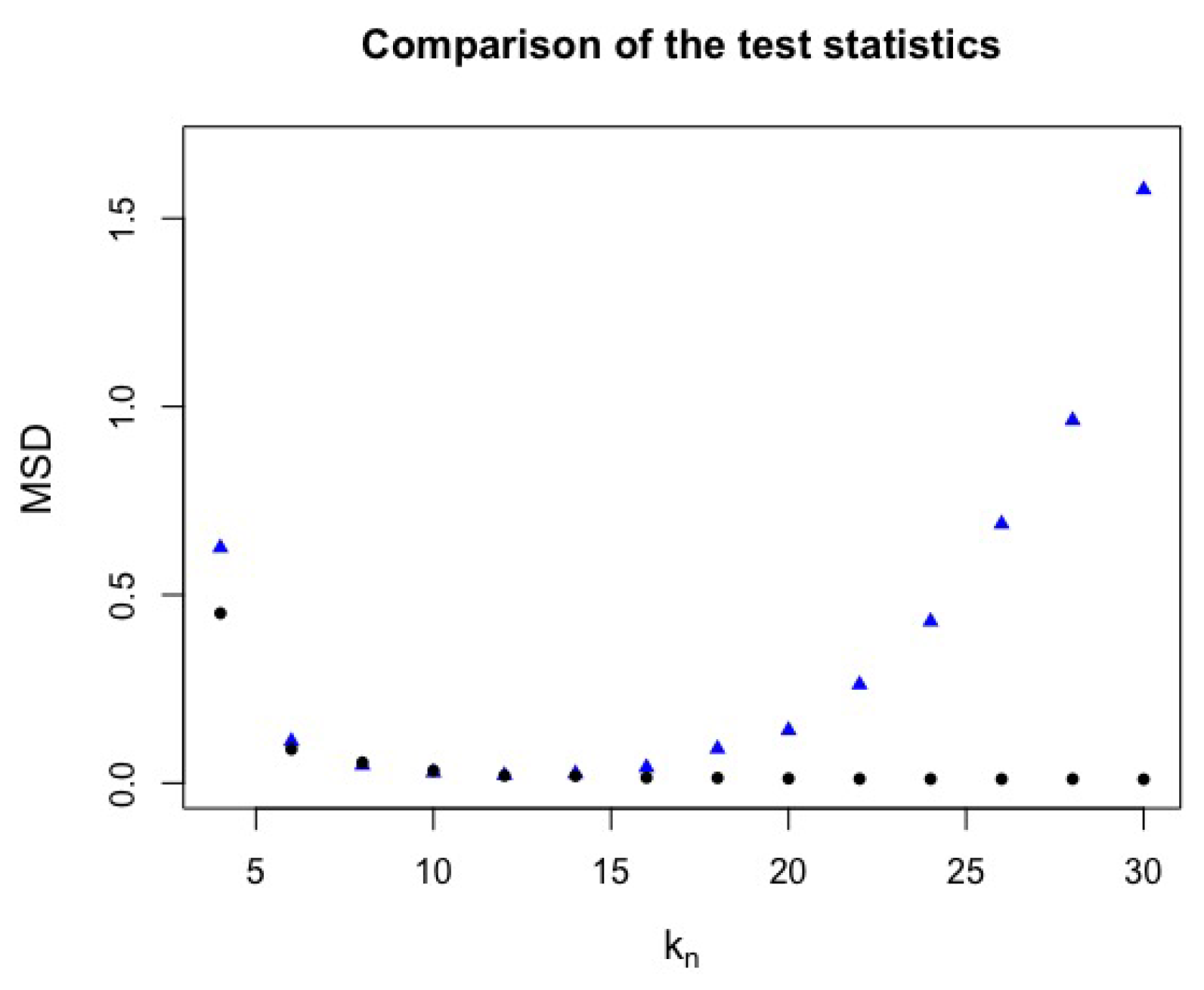

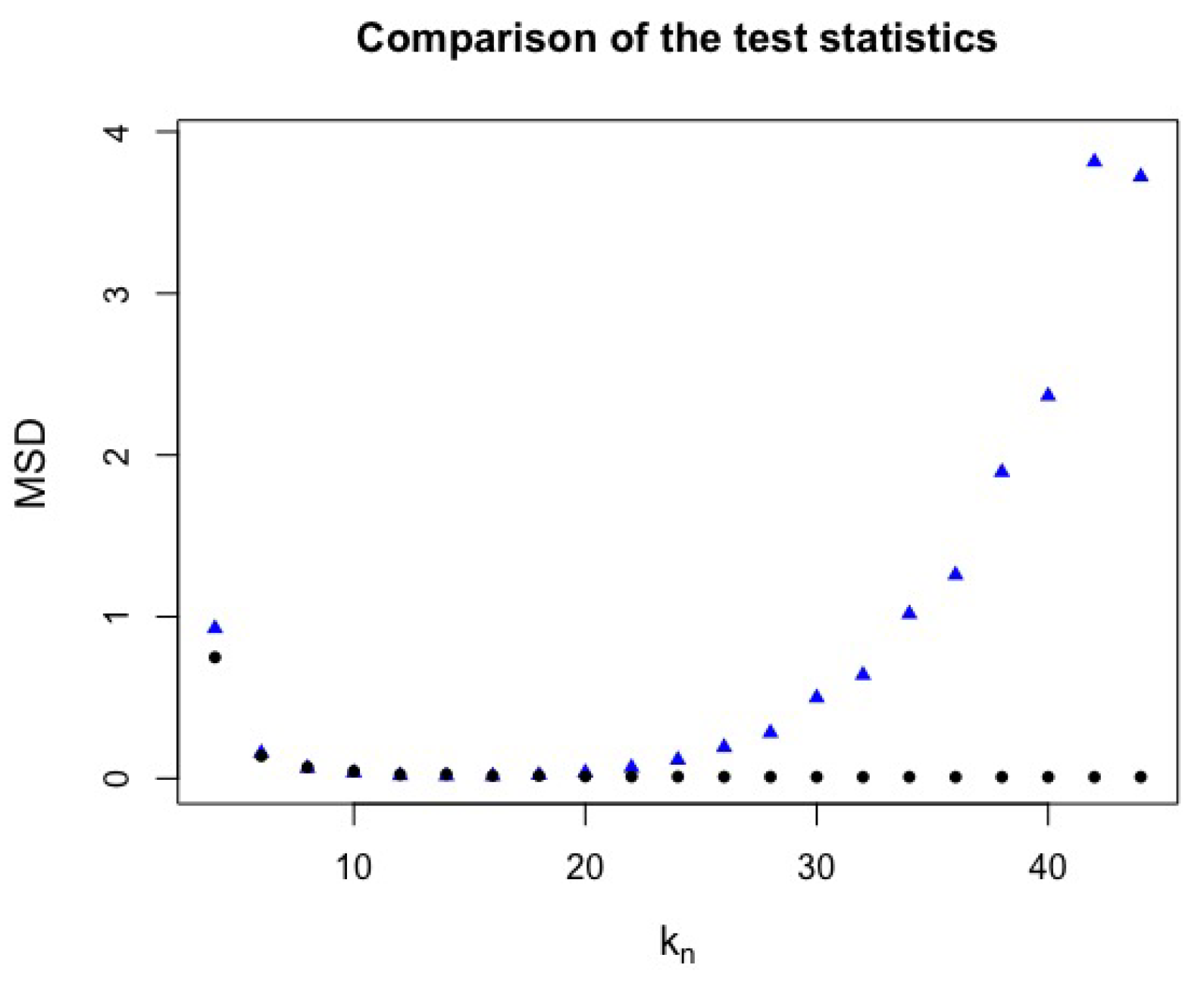

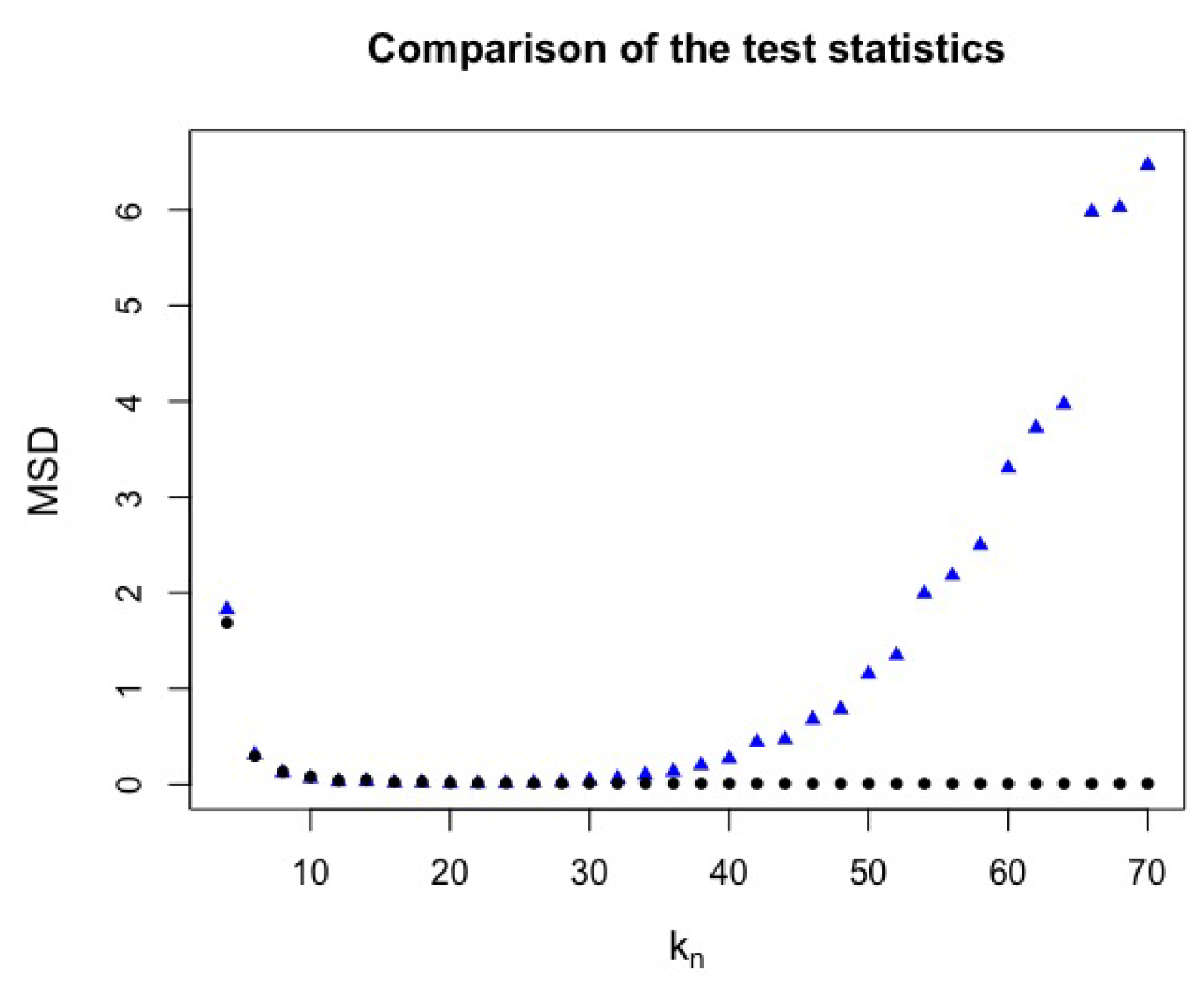

as mentioned above. The mean squared distance (MSD) is the difference between the values observed of test statistics from the two models used. It can be observed in

Figure 3 that, for the jump-diffusion model, the MSD of test statistic increases as

increases. On the other hand, for the normal model, on the average, the MSD of test statistics stabilizes, that is, the values of test statistics are close as

increases.

One purpose is to estimate the best critical value of test statistics to choose which test performs better.

The ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve is widely used to determine the cutoff point. The best critical value is obtained using simulation. A ROC curve can be described as the shape of the trade-off between the sensitivity and the specificity of a test, for every possible decision rule cutoff (or threshold) between 0 and 1. The optimal cutoff point is the one closer to the point, and this gives the values of the specificity and sensitivity of the test. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) gives the accuracy of the test. The larger the area, the larger the accuracy of the test. In our case, we will call the sensitivity by detection power and 1-specificity the error rate.

2.2. The Best Critical Value

We test the critical value

q between 1 and 3, and used the ROC curve to find the cutoff point. We compare the detection power and error rate for these values and a fixed critical value.

Table 1 shows that, for

test statistic with a fixed critical value

, the error rate for

is around

and the detection power is

. In contrast, for

test statistic, the error rate is around

and the detection power is

. It can also be seen that, for low

values of

, there are low error rates but with low detection power. For example, for

, with

, there is an error rate around

and a detection power of

and, for

, we observe

of error rate and

of detection power. Moreover, for the optimal critical value

, with

, we have an error rate of

and a detection power of

for

and, for

, an error rate of

and

of detection power.

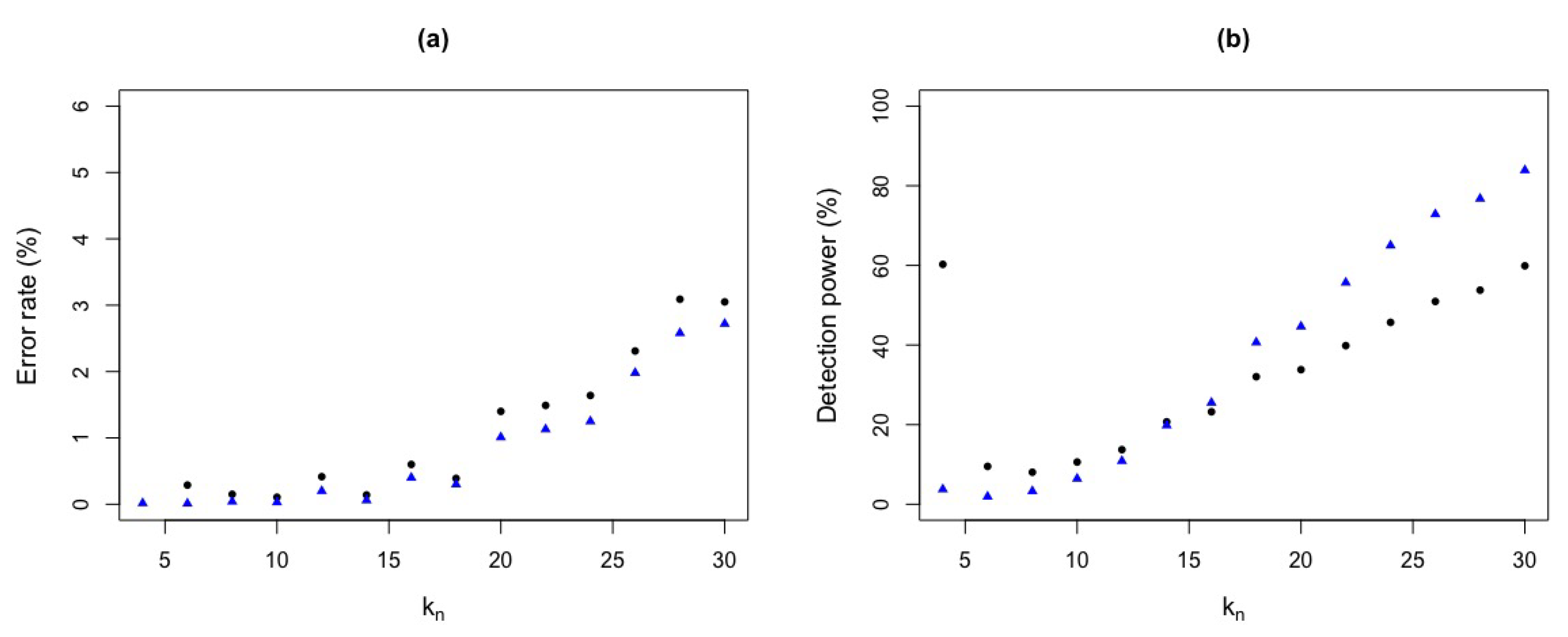

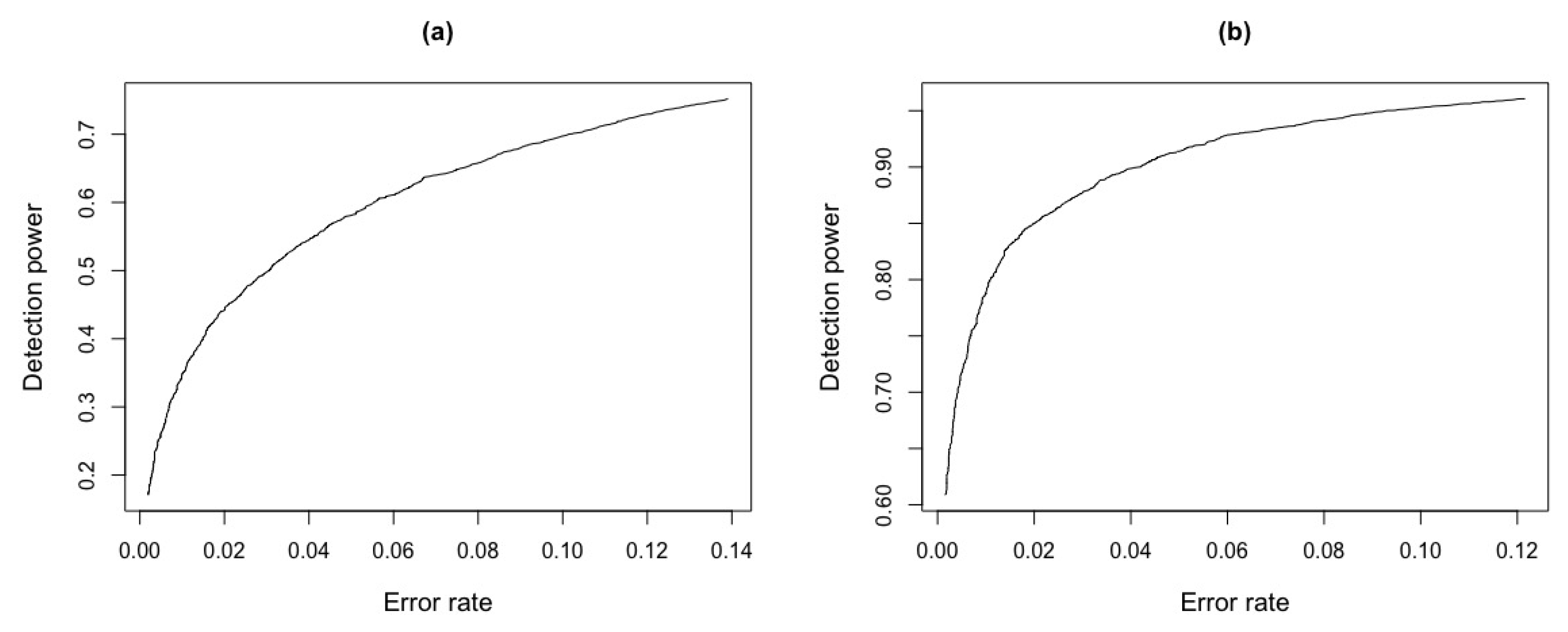

Figure 4 shows the detection power and error rate for a fixed critical value

.

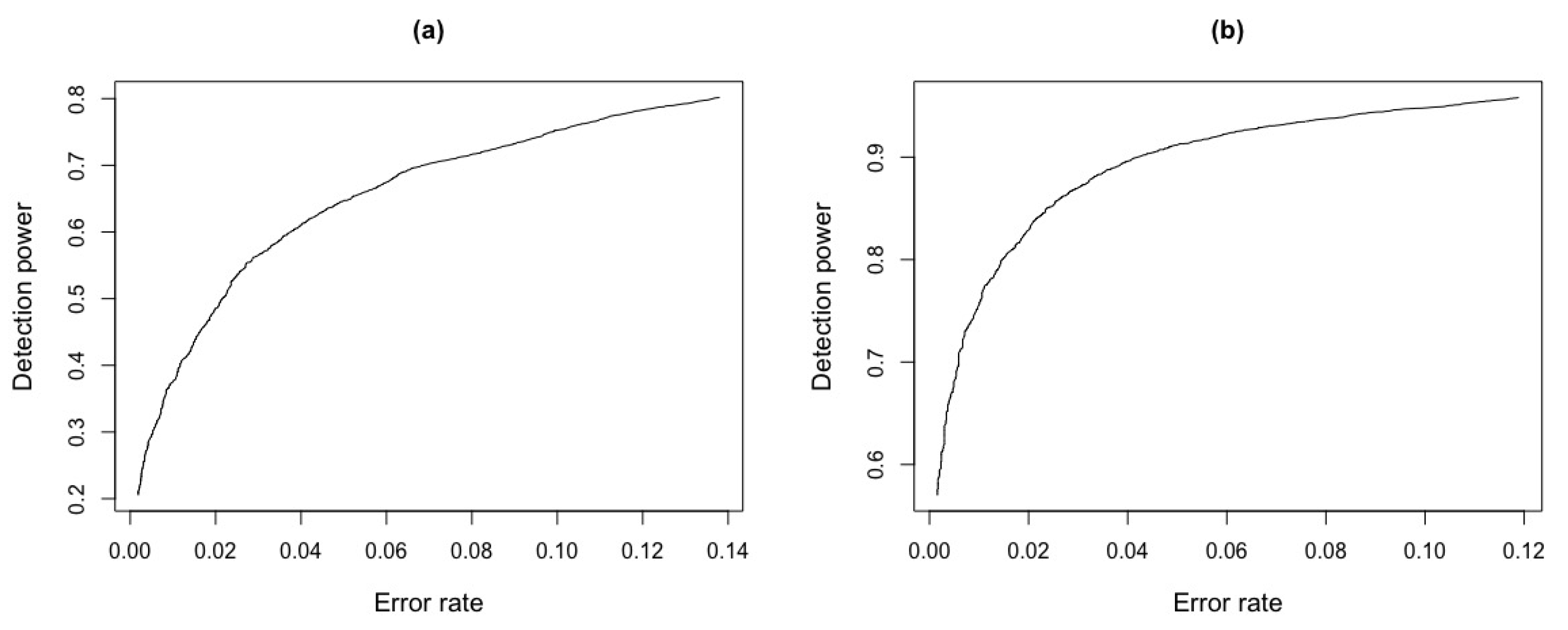

Figure 5 shows the detection power and error rate of a simulated critical value

, that were obtained through the respective ROC curves in

Figure 6. We repeat our simulation for

and the same pairs of

and

already mentioned above. The conclusion is similar to

.

The MSD of test statistics, are shown in

Figure 7.

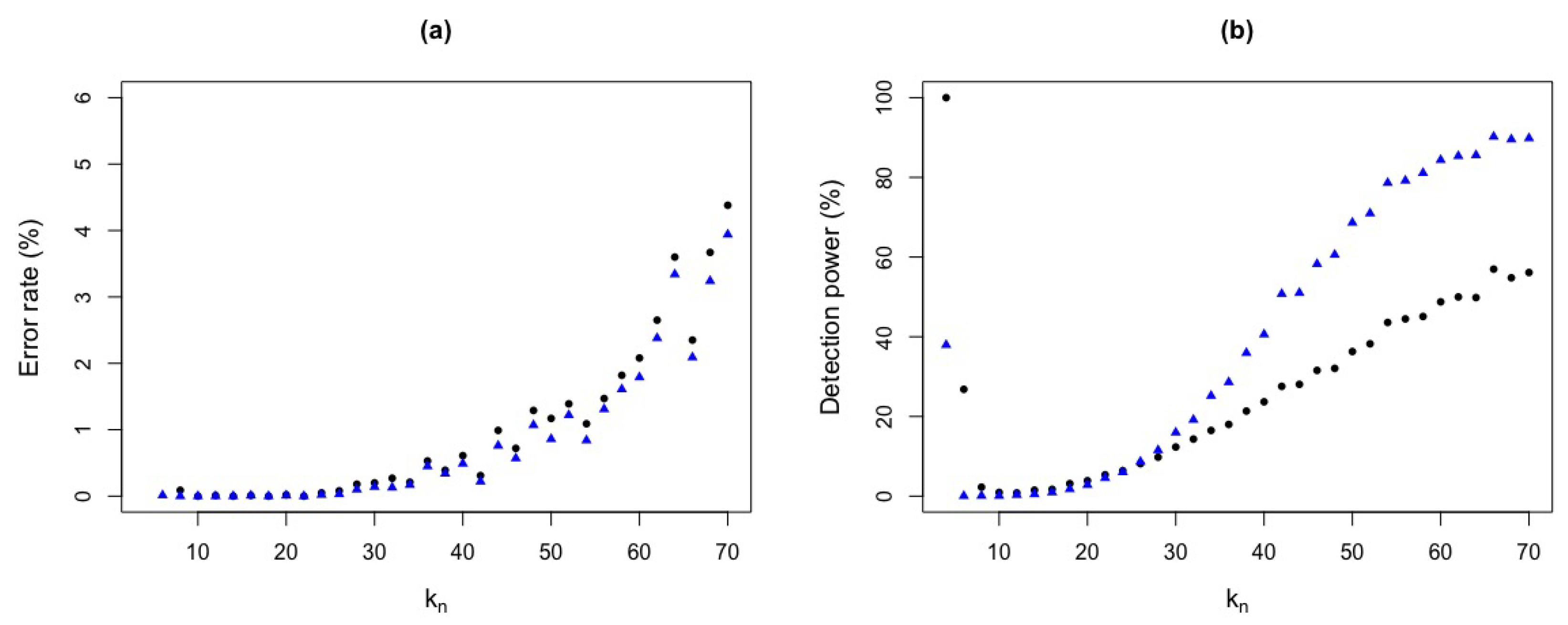

Figure 8 shows the detection power and error rate for a fixed critical value

.

Table 2 shows the detection powers and error rates for two critical values, a fixed and simulated, which lead us to conclude that

test statistic is better than

test statistic. For example, for

with

, we have an error rate of

and a detection power of

for

test statistic whereas

test statistic presents an error rate of

and a low detection power of

.

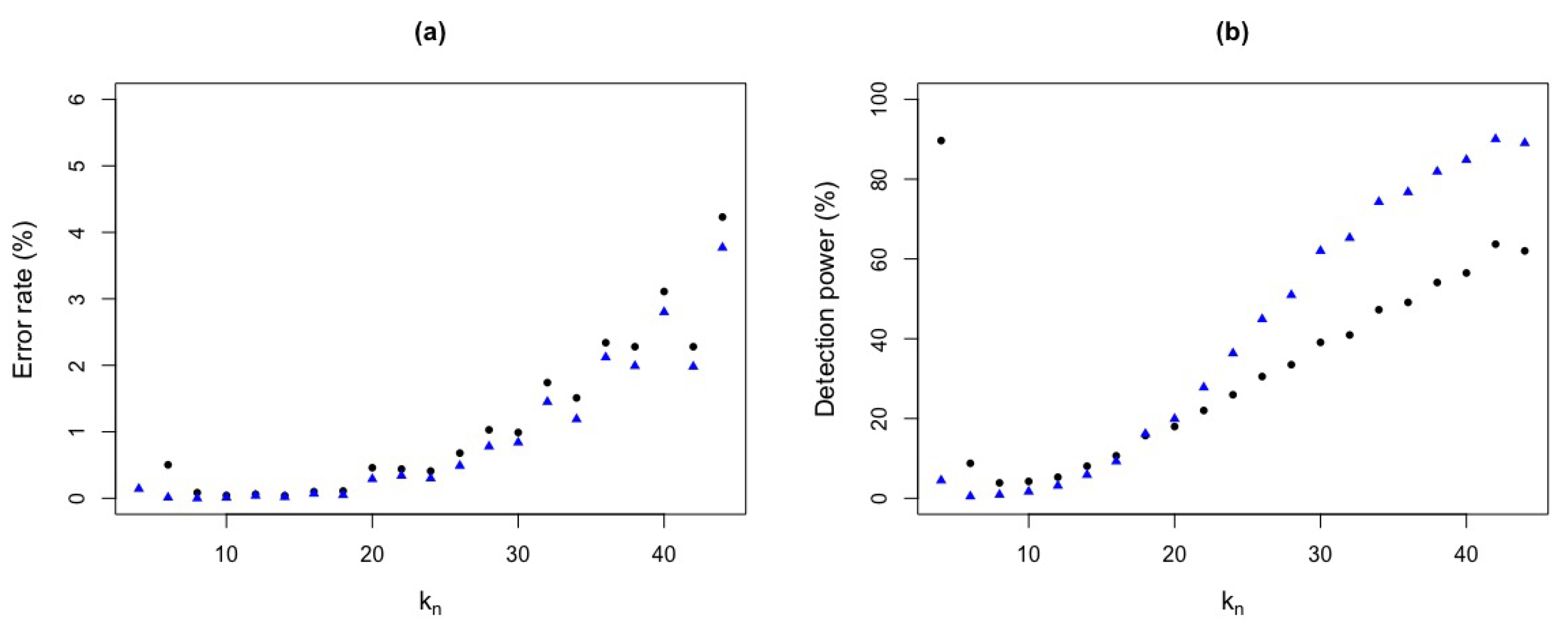

Figure 9 shows the detection power and error rate for

, obtained by simulation, with the ROC curves in

Figure 10. It can be seen that as

increases the error rate for

is higher than

and, for the detection power, as

increases,

has a higher detection power than

. Again,

test statistic seems to be better than

test statistic.

We can observe in

Figure 11 that the MSD of the test statistics has a similar behavior to the previous analysis.

We are interested in the largest squared distance, so the pairs of for , we will be used for our study for the aforementioned reasons.

Figure 12 shows the detection power and error rate for a fixed critical value

.

Figure 13 shows the detection power and error rate considering a simulated critical value, obtained by ROC curve, see

Figure 14.

Table 3 shows that, for a fixed value

, the error rate for

test statistic, with

is around

and the detection power is

. In contrast, for the test statistic

, the error rate is around

and detection power of

. It can also be seen that, for low

values for

test statistic, there are low error rates but with low detection power. For example, taking

, for

test statistic, there is an error rate around

and

of detection power. On the other hand, for the simulated critical value

obtained by ROC curve and

, we have an error rate of

and a detection power of

for

test statistic and for

, we observe an error rate of

and a detection power of

.

Remark: Note that;

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 for

and

values, the error rate and detection power show inconsistent values, due to a high false alarm rate and not so much detection power. Therefore, we do not recommend using low values of

.

We will use test statistic, since it presented better results in relation to low error rate and high detection power. The ideal is to choose a that shows a low error rate and high detection power.

In contrast, for

test statistic, there is high error rate and low detection power for most

values. See also

Table 4. Also, the area under the ROC curve of

shows a larger area, and therefore the larger the area, the greater the accuracy of the test, which leads us to conclude that our

test is better than

.

4. A simulation Study

We conduct a simulation study to check the performance of the

test statistic.

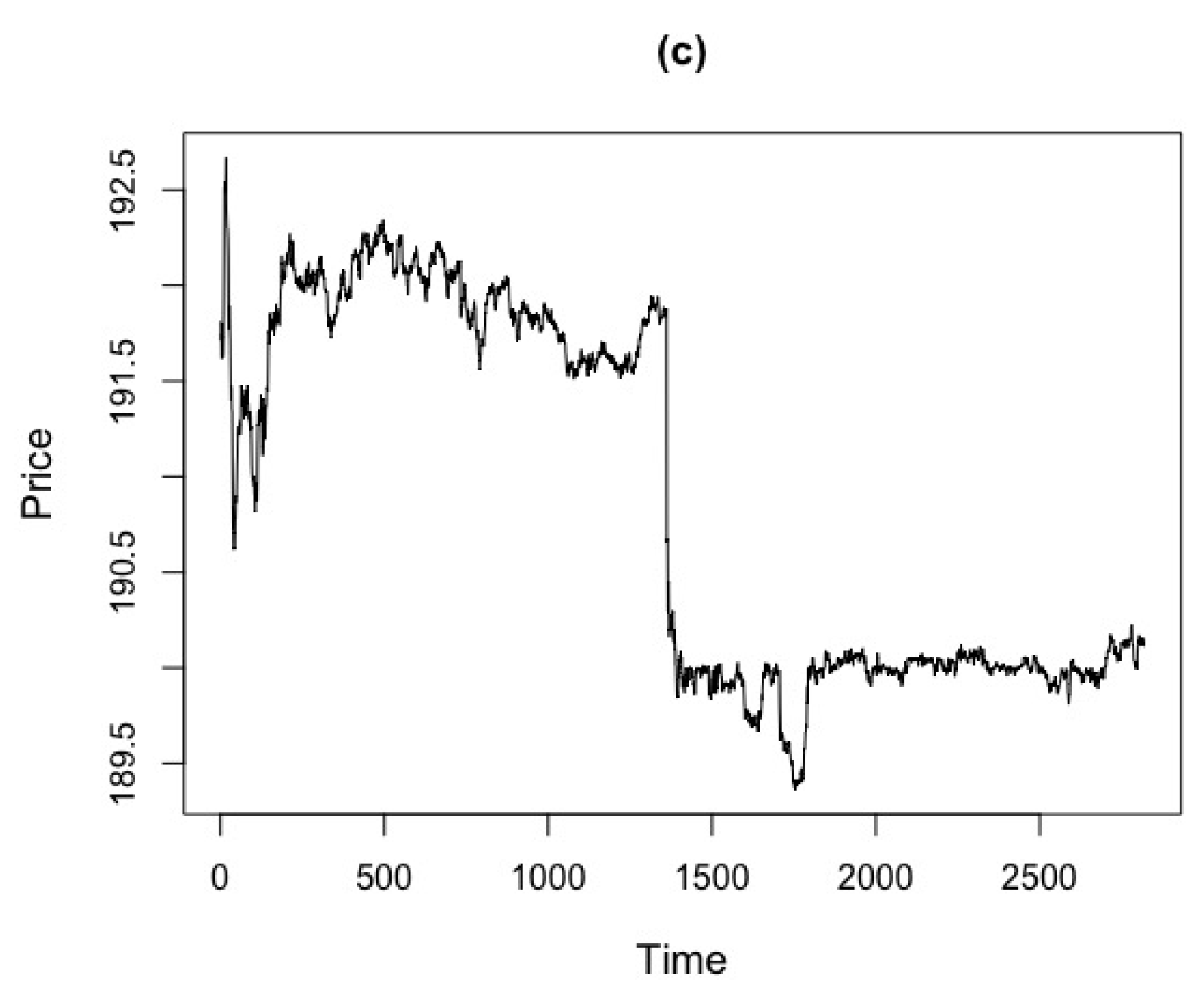

Figure 17 shows data generated from the jump-diffusion and standard normal models that we used in our study.

The models are defined as follows: the jump-diffusion model is given by,

where

is a skewed

Lévy process. The volatility

is a square root diffusion process which is widely used in financial applications. The parameter in

is specified as in [

13]. The standard normal model is

, where

is the initial value that should be defined.

We considered

replicas for sample sizes

and

. For the truncation of the increments, as is typical in the literature, we set

and

. Hence for the sampling frequencies mentioned in

Section 2, we set the pairs of

as:

,

,

,

and

with

ranging from

to

and having an increasing trend.

In

Table 7 we can observe that the

test power increases as the sample size increases and also, for

n fixed,

test power is bigger for largest

values. The

test power was calculated with the gamma quantile values, and we note that these values are very close to the empirical quantiles. To evaluate the performance of our test, we compare with the KS test, which also measures discrepancy between distributions.

In

Table 8 we note that the

test statistic shows better results. Moreover, the KS test power decreases and the error rate increases as

n increases. For

, KS test power is bigger than

test power, however

test statistic has an error rate of

and KS test has an error rate bigger than

. For larger sample sizes, the

test statistic shows better test power with low error rate. Besides, KS test power decreases and the error rate increases as

n increases. For

, KS test power is bigger than

test power, however

test statistic has an error rate of

and KS test has an error rate bigger than

.

For larger sample sizes, the test statistic shows better power with low error rate.

Figure 1.

Behavior of and test statistics against for the jump-diffusion model. The simulation were based on replicas and different n values. (a) . (b) . (c) . (d) . (e) . (f) .

Figure 1.

Behavior of and test statistics against for the jump-diffusion model. The simulation were based on replicas and different n values. (a) . (b) . (c) . (d) . (e) . (f) .

Figure 2.

Behavior of and test statistics against for the standard normal model. The simulation were based on replicas and different n values. (a) . (b) . (c) . (d) . (e) . (f) .

Figure 2.

Behavior of and test statistics against for the standard normal model. The simulation were based on replicas and different n values. (a) . (b) . (c) . (d) . (e) . (f) .

Figure 3.

MSD of test statistics for different values in data generated from the jump-diffusion (blue triangle) and standard normal (black circle) models with .

Figure 3.

MSD of test statistics for different values in data generated from the jump-diffusion (blue triangle) and standard normal (black circle) models with .

Figure 4.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

Figure 4.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

Figure 5.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

Figure 5.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

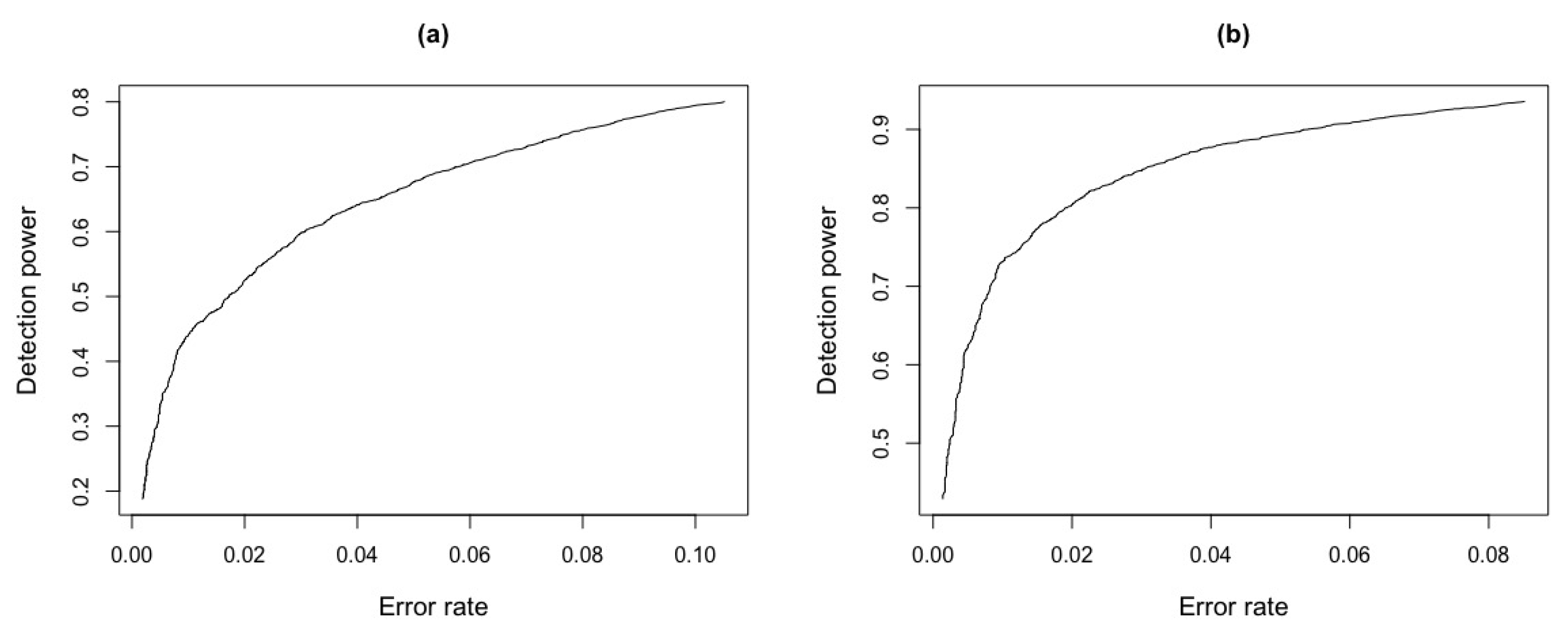

Figure 6.

ROC curve for

and

test statistics for

Figure 5. (

a) ROC curve

. (

b) ROC curve

.

Figure 6.

ROC curve for

and

test statistics for

Figure 5. (

a) ROC curve

. (

b) ROC curve

.

Figure 7.

MSD of test statistics for different values, in data generated from the jump-diffusion (blue triangle) and standard normal (black circle) models with .

Figure 7.

MSD of test statistics for different values, in data generated from the jump-diffusion (blue triangle) and standard normal (black circle) models with .

Figure 8.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

Figure 8.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

Figure 9.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

Figure 9.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

Figure 10.

ROC curve for

and

test statistics for

Figure 9. (

a) ROC curve

. (

b) ROC curve

.

Figure 10.

ROC curve for

and

test statistics for

Figure 9. (

a) ROC curve

. (

b) ROC curve

.

Figure 11.

MSD of test statistics for different values, in data generated from the jump-diffusion (blue triangle) and standard normal (black circle) models with .

Figure 11.

MSD of test statistics for different values, in data generated from the jump-diffusion (blue triangle) and standard normal (black circle) models with .

Figure 12.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

Figure 12.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

Figure 13.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

Figure 13.

Error rate and detection power with critical value and different values with . (a) Error rates for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics. (b) Detection powers for (black circle) and (blue triangle) test statistics.

Figure 14.

ROC curve for

and

test statistics for

Figure 13. (

a) ROC curve

. (

b) ROC curve

.

Figure 14.

ROC curve for

and

test statistics for

Figure 13. (

a) ROC curve

. (

b) ROC curve

.

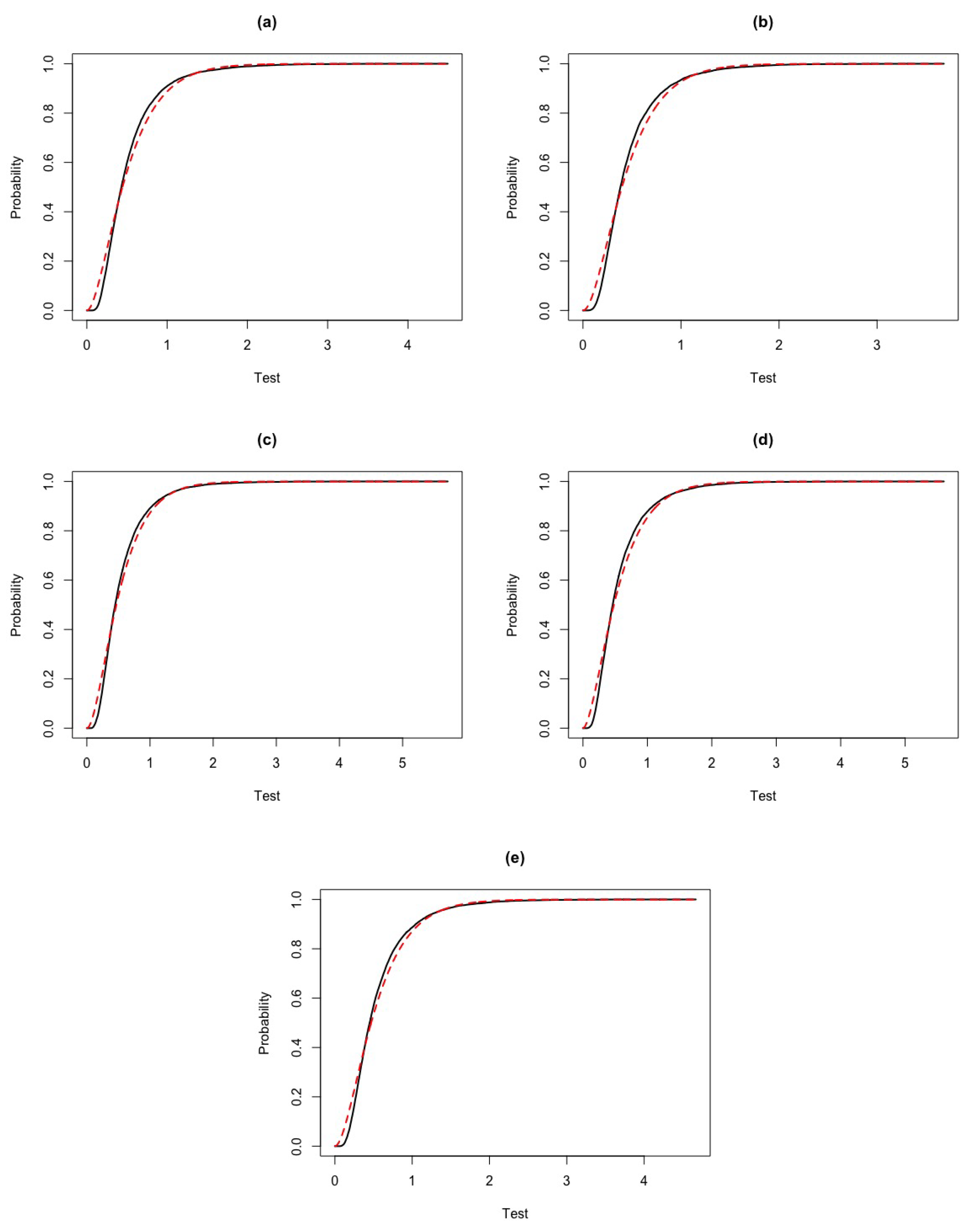

Figure 15.

Comparison between the edf of (black curve) and the gamma distribution function (red curve) for different and sample sizes n. (a) . (b) . (c) . (d) . (e) .

Figure 15.

Comparison between the edf of (black curve) and the gamma distribution function (red curve) for different and sample sizes n. (a) . (b) . (c) . (d) . (e) .

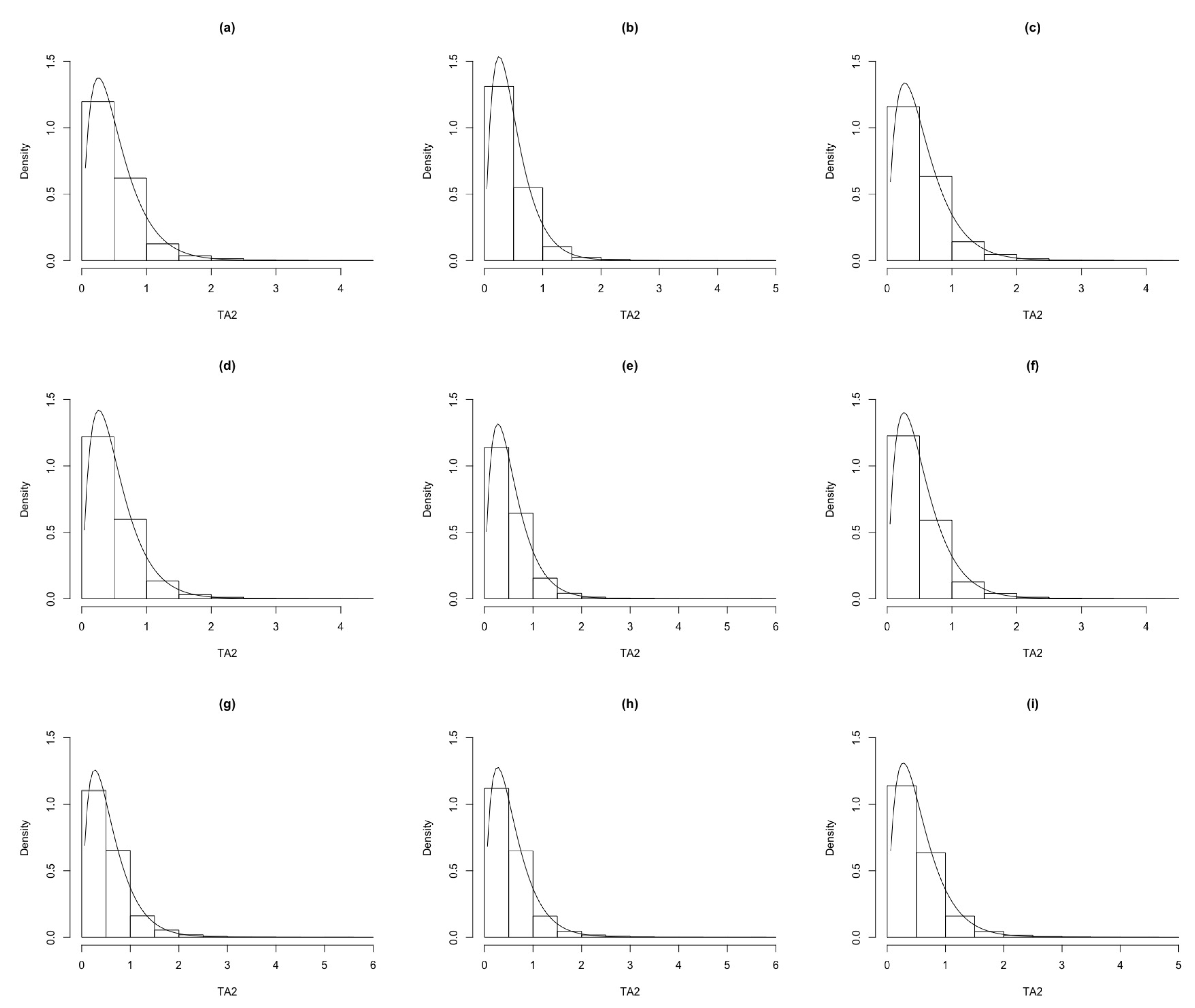

Figure 16.

Histograms of the edf of TA2 for different and sample sizes, n, compared with the gamma density (black curve). (a) . (b) . (c) . (d) . (e) . (f) . (g) . (h) . (i) .

Figure 16.

Histograms of the edf of TA2 for different and sample sizes, n, compared with the gamma density (black curve). (a) . (b) . (c) . (d) . (e) . (f) . (g) . (h) . (i) .

Figure 17.

Data generated from the jump-diffusion and standard normal models. (a) Jump-difussion model. (b) Standard normal model.

Figure 17.

Data generated from the jump-diffusion and standard normal models. (a) Jump-difussion model. (b) Standard normal model.

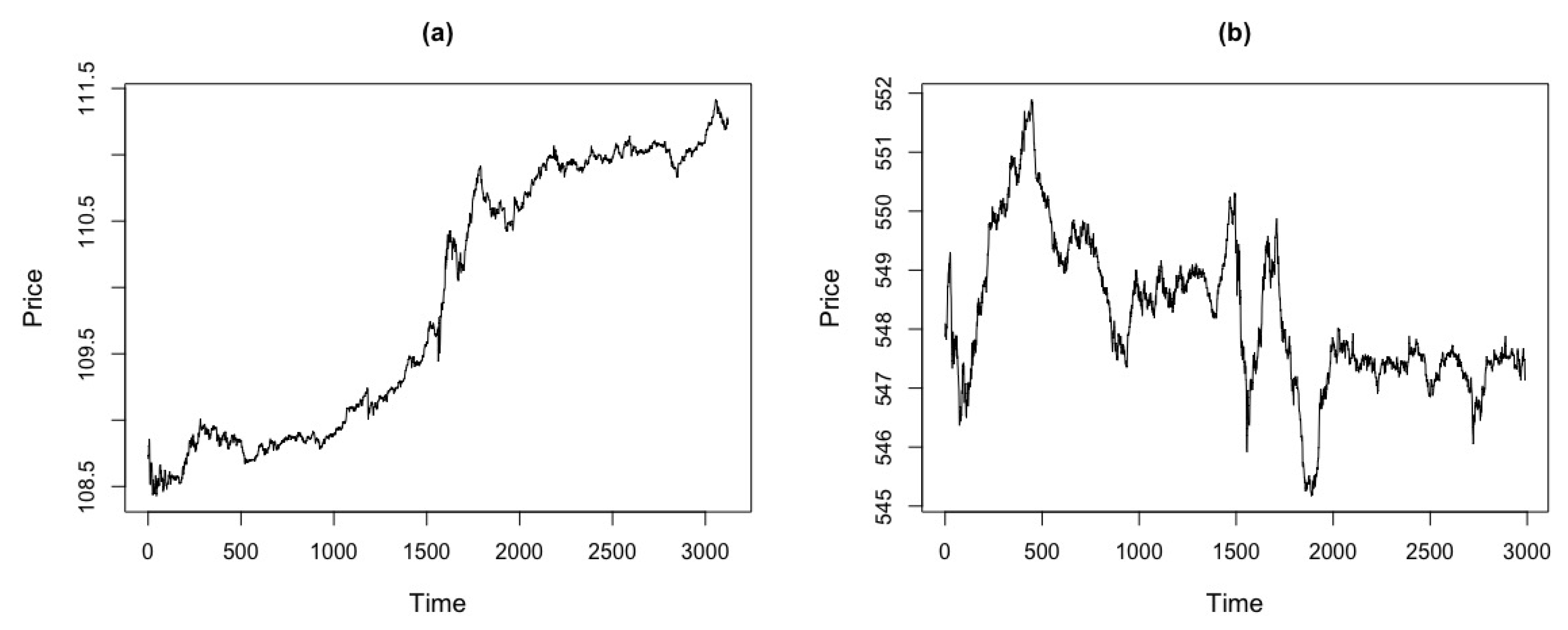

Figure 18.

Price series for market data of Apple, Google and GS stocks with transactions from 9:30 a.m to 4:00 p.m. (a) Apple. (b) Google. (c) GS.

Figure 18.

Price series for market data of Apple, Google and GS stocks with transactions from 9:30 a.m to 4:00 p.m. (a) Apple. (b) Google. (c) GS.

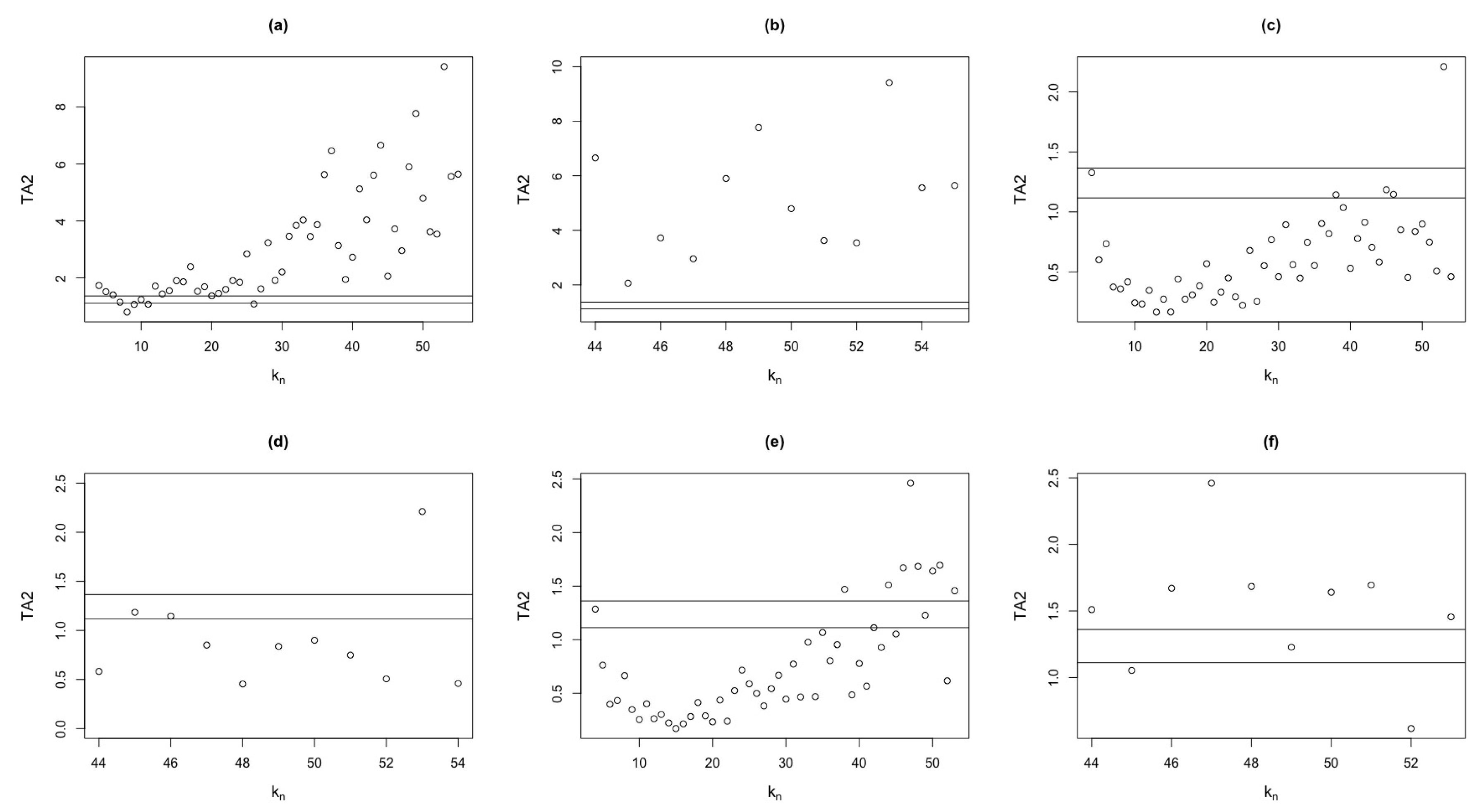

Figure 19.

test statistic, compared to different values for Apple, Google and GS stocks. (a) Apple, . (b) Apple, . (c) Google, . (d) Google, . (e) GS, . (f) GS, .

Figure 19.

test statistic, compared to different values for Apple, Google and GS stocks. (a) Apple, . (b) Apple, . (c) Google, . (d) Google, . (e) GS, . (f) GS, .

Table 1.

Error rates and detection powers for values between 4 and 30, a fixed critical value and the simulated critical value , in replicas of data generated with .

Table 1.

Error rates and detection powers for values between 4 and 30, a fixed critical value and the simulated critical value , in replicas of data generated with .

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Error rate |

Detection power |

Error rate |

Detection power |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

2 |

0.2728 |

0.0002 |

0.6026 |

0.0376 |

0.5286 |

0.0052 |

0.8217 |

0.1453 |

| 6 |

3 |

0.0029 |

0.0001 |

0.0952 |

0.0193 |

0.0204 |

0.0004 |

0.2378 |

0.0604 |

| 8 |

4 |

0.0015 |

0.0004 |

0.0805 |

0.0330 |

0.0056 |

0.0010 |

0.1793 |

0.0863 |

| 10 |

5 |

0.0011 |

0.0003 |

0.1061 |

0.0643 |

0.0057 |

0.0008 |

0.2074 |

0.1402 |

| 12 |

5 |

0.0042 |

0.0020 |

0.1372 |

0.1088 |

0.0100 |

0.0052 |

0.2324 |

0.1993 |

| 14 |

8 |

0.0014 |

0.0006 |

0.2071 |

0.1982 |

0.0054 |

0.0028 |

0.3248 |

0.3242 |

| 16 |

7 |

0.0060 |

0.0040 |

0.2323 |

0.2551 |

0.0164 |

0.0113 |

0.3490 |

0.3833 |

| 18 |

11 |

0.0039 |

0.0030 |

0.3204 |

0.4066 |

0.0110 |

0.0082 |

0.4578 |

0.5502 |

| 20 |

9 |

0.0140 |

0.0101 |

0.3381 |

0.4465 |

0.0287 |

0.0213 |

0.4616 |

0.5796 |

| 22 |

11 |

0.0149 |

0.0113 |

0.3984 |

0.5568 |

0.0306 |

0.0247 |

0.5208 |

0.6814 |

| 24 |

12 |

0.0164 |

0.0125 |

0.4569 |

0.6501 |

0.0354 |

0.0258 |

0.5795 |

0.7586 |

| 26 |

13 |

0.0231 |

0.0198 |

0.5094 |

0.7286 |

0.0451 |

0.0378 |

0.6255 |

0.8170 |

| 28 |

13 |

0.0309 |

0.0258 |

0.5378 |

0.7675 |

0.0585 |

0.0482 |

0.6472 |

0.8477 |

| 30 |

16 |

0.0305 |

0.0272 |

0.5989 |

0.8390 |

0.0599 |

0.0500 |

0.7057 |

0.8937 |

Table 2.

Error rates and detection powers for values between 4 and 44, a fixed critical value and, the simulated critical value , in replicas of data generated with .

Table 2.

Error rates and detection powers for values between 4 and 44, a fixed critical value and, the simulated critical value , in replicas of data generated with .

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Error rate |

Detection power |

Error rate |

Detection power |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

2 |

0.7289 |

0.0014 |

0.8966 |

0.0449 |

0.8380 |

0.0090 |

0.9519 |

0.1101 |

| 6 |

3 |

0.0050 |

0.0001 |

0.0877 |

0.0049 |

0.0164 |

0.0002 |

0.1565 |

0.0110 |

| 8 |

4 |

0.0008 |

0.0000 |

0.0387 |

0.0090 |

0.0018 |

0.0000 |

0.0688 |

0.0162 |

| 10 |

5 |

0.0004 |

0.0001 |

0.0424 |

0.0168 |

0.0011 |

0.0003 |

0.0681 |

0.0288 |

| 12 |

5 |

0.0006 |

0.0004 |

0.0530 |

0.0316 |

0.0015 |

0.0008 |

0.0793 |

0.0512 |

| 14 |

8 |

0.0004 |

0.0002 |

0.0806 |

0.0587 |

0.0006 |

0.0003 |

0.1223 |

0.0892 |

| 16 |

7 |

0.0010 |

0.0007 |

0.1066 |

0.0926 |

0.0018 |

0.0010 |

0.1471 |

0.1277 |

| 18 |

11 |

0.0011 |

0.0005 |

0.1572 |

0.1615 |

0.0021 |

0.0008 |

0.2067 |

0.2145 |

| 20 |

9 |

0.0046 |

0.0029 |

0.1799 |

0.1992 |

0.0063 |

0.0041 |

0.2227 |

0.2533 |

| 22 |

11 |

0.0044 |

0.0034 |

0.2201 |

0.2779 |

0.0069 |

0.0051 |

0.2713 |

0.3444 |

| 24 |

12 |

0.0041 |

0.0030 |

0.2596 |

0.3635 |

0.0075 |

0.0056 |

0.3168 |

0.4325 |

| 26 |

13 |

0.0068 |

0.0049 |

0.3052 |

0.4489 |

0.0110 |

0.0076 |

0.3589 |

0.5166 |

| 28 |

13 |

0.0103 |

0.0078 |

0.3350 |

0.5095 |

0.0152 |

0.0116 |

0.3876 |

0.5730 |

| 30 |

16 |

0.0099 |

0.0084 |

0.3908 |

0.6201 |

0.0158 |

0.0125 |

0.4465 |

0.6761 |

| 32 |

15 |

0.0174 |

0.0145 |

0.4094 |

0.6527 |

0.0249 |

0.0208 |

0.4670 |

0.7058 |

| 34 |

18 |

0.0151 |

0.0119 |

0.4726 |

0.7428 |

0.0223 |

0.0183 |

0.5326 |

0.7878 |

| 36 |

17 |

0.0234 |

0.0212 |

0.4911 |

0.7673 |

0.0341 |

0.0295 |

0.5451 |

0.8075 |

| 38 |

20 |

0.0228 |

0.0199 |

0.5409 |

0.8189 |

0.0310 |

0.0263 |

0.5943 |

0.8515 |

| 40 |

20 |

0.0311 |

0.0280 |

0.5648 |

0.8483 |

0.0430 |

0.0381 |

0.6188 |

0.8776 |

| 42 |

26 |

0.0228 |

0.0198 |

0.6370 |

0.9004 |

0.0327 |

0.0274 |

0.6876 |

0.9205 |

| 44 |

21 |

0.0423 |

0.0377 |

0.6201 |

0.8905 |

0.0576 |

0.0500 |

0.6659 |

0.9118 |

Table 3.

Error rates and detection powers for values between 4 and 70, a fixed critical value and the simulated critical value , in replicas of data generated with .

Table 3.

Error rates and detection powers for values between 4 and 70, a fixed critical value and the simulated critical value , in replicas of data generated with .

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Error rate |

Detection power |

Error rate |

Detection power |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

2 |

1.0000 |

0.1851 |

1.0000 |

0.3794 |

1.0000 |

0.4053 |

1.0000 |

0.6061 |

| 6 |

3 |

0.1101 |

0.0001 |

0.2681 |

0.0005 |

0.2176 |

0.0001 |

0.4208 |

0.0022 |

| 8 |

4 |

0.0009 |

0.0000 |

0.0226 |

0.0010 |

0.0034 |

0.0000 |

0.0452 |

0.0013 |

| 10 |

5 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0094 |

0.0009 |

0.0001 |

0.0000 |

0.0179 |

0.0019 |

| 12 |

5 |

0.0001 |

0.0000 |

0.0082 |

0.0031 |

0.0004 |

0.0001 |

0.0145 |

0.0052 |

| 14 |

8 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0150 |

0.0048 |

0.0001 |

0.0000 |

0.0261 |

0.0087 |

| 16 |

7 |

0.0001 |

0.0001 |

0.0171 |

0.0096 |

0.0004 |

0.0001 |

0.0279 |

0.0159 |

| 18 |

11 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0314 |

0.0177 |

0.0001 |

0.0000 |

0.0481 |

0.0281 |

| 20 |

9 |

0.0002 |

0.0001 |

0.0387 |

0.0282 |

0.0008 |

0.0004 |

0.0548 |

0.0413 |

| 22 |

11 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0536 |

0.0455 |

0.0006 |

0.0000 |

0.0699 |

0.0613 |

| 24 |

12 |

0.0005 |

0.0002 |

0.0638 |

0.0602 |

0.0009 |

0.0004 |

0.0875 |

0.0826 |

| 26 |

13 |

0.0008 |

0.0003 |

0.0815 |

0.0864 |

0.0012 |

0.0006 |

0.1080 |

0.1115 |

| 28 |

13 |

0.0018 |

0.0010 |

0.0978 |

0.1153 |

0.0028 |

0.0020 |

0.1246 |

0.1479 |

| 30 |

16 |

0.0020 |

0.0014 |

0.1233 |

0.1597 |

0.0031 |

0.0018 |

0.1538 |

0.1954 |

| 32 |

15 |

0.0027 |

0.0013 |

0.1432 |

0.1917 |

0.0036 |

0.0023 |

0.1705 |

0.2296 |

| 34 |

18 |

0.0021 |

0.0017 |

0.1649 |

0.2518 |

0.0030 |

0.0024 |

0.2011 |

0.2998 |

| 36 |

17 |

0.0053 |

0.0045 |

0.1800 |

0.2860 |

0.0070 |

0.0055 |

0.2174 |

0.3341 |

| 38 |

20 |

0.0039 |

0.0034 |

0.2135 |

0.3594 |

0.0055 |

0.0046 |

0.2530 |

0.4150 |

| 40 |

20 |

0.0061 |

0.0049 |

0.2368 |

0.4059 |

0.0093 |

0.0070 |

0.2742 |

0.4615 |

| 42 |

26 |

0.0031 |

0.0022 |

0.2755 |

0.5076 |

0.0050 |

0.0035 |

0.3185 |

0.5618 |

| 44 |

21 |

0.0099 |

0.0076 |

0.2806 |

0.5101 |

0.0133 |

0.0110 |

0.3189 |

0.5559 |

| 46 |

25 |

0.0072 |

0.0057 |

0.3156 |

0.5826 |

0.0108 |

0.0082 |

0.3556 |

0.6267 |

| 48 |

23 |

0.0129 |

0.0107 |

0.3206 |

0.6058 |

0.0171 |

0.0154 |

0.3626 |

0.6514 |

| 50 |

28 |

0.0117 |

0.0086 |

0.3629 |

0.6863 |

0.0160 |

0.0127 |

0.4086 |

0.7277 |

| 52 |

27 |

0.0139 |

0.0122 |

0.3823 |

0.7097 |

0.0193 |

0.0164 |

0.4226 |

0.7437 |

| 54 |

34 |

0.0109 |

0.0084 |

0.4359 |

0.7863 |

0.0158 |

0.0126 |

0.4834 |

0.8156 |

| 56 |

31 |

0.0147 |

0.0131 |

0.4448 |

0.7919 |

0.0200 |

0.0169 |

0.4888 |

0.8212 |

| 58 |

30 |

0.0182 |

0.0161 |

0.4508 |

0.8111 |

0.0252 |

0.0219 |

0.4944 |

0.8371 |

| 60 |

34 |

0.0208 |

0.0179 |

0.4876 |

0.8437 |

0.0270 |

0.0229 |

0.5301 |

0.8677 |

| 62 |

33 |

0.0265 |

0.0238 |

0.4999 |

0.8536 |

0.0334 |

0.0299 |

0.5411 |

0.8743 |

| 64 |

30 |

0.0360 |

0.0334 |

0.4983 |

0.8557 |

0.0451 |

0.0401 |

0.5380 |

0.8770 |

| 66 |

40 |

0.0235 |

0.0209 |

0.5697 |

0.9022 |

0.0291 |

0.0271 |

0.6127 |

0.9186 |

| 68 |

35 |

0.0367 |

0.0324 |

0.5480 |

0.8955 |

0.0470 |

0.0417 |

0.5882 |

0.9123 |

| 70 |

33 |

0.0438 |

0.0394 |

0.5613 |

0.8982 |

0.0552 |

0.0499 |

0.5994 |

0.9140 |

Table 4.

Error rates and detection powers of test statistic, for a fixed critical value and optimal critical values, in some scenarios for n.

Table 4.

Error rates and detection powers of test statistic, for a fixed critical value and optimal critical values, in some scenarios for n.

| |

|

|

Optimal q

|

| n |

|

|

Error rate |

Detection power |

Error rate |

Detection power |

| 1,000 |

30 |

16 |

0.0272 |

0.8390 |

0.05

|

0.8937 |

| 2,000 |

44 |

21 |

0.0377 |

0.8905 |

0.05

|

0.9118 |

| 5,000 |

70 |

33 |

0.0394 |

0.8982 |

0.049

|

0.9140 |

Table 5.

Comparison between empirical and true gamma quantiles, for values between 18 and 100 and, between 11 and 54, with large values for n.

Table 5.

Comparison between empirical and true gamma quantiles, for values between 18 and 100 and, between 11 and 54, with large values for n.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

empirical |

| n |

|

|

a |

b |

quantile

|

quantile

|

| 500 |

18 |

11 |

2.254 |

0.190 |

0.982 |

0.970 |

| |

20 |

11 |

2.109 |

0.238 |

1.174 |

1.165 |

| |

22 |

12 |

1.938 |

0.274 |

1.273 |

1.243 |

| 1,000 |

26 |

13 |

2.083 |

0.231 |

1.128 |

1.116 |

| |

28 |

13 |

1.993 |

0.267 |

1.266 |

1.270 |

| |

30 |

19 |

2.064 |

0.228 |

1.106 |

1.084 |

| 2,000 |

40 |

18 |

1.922 |

0.283 |

1.308 |

1.296 |

| |

42 |

22 |

1.972 |

0.267 |

1.259 |

1.246 |

| |

44 |

22 |

1.953 |

0.282 |

1.320 |

1.304 |

| 5,000 |

66 |

36 |

1.993 |

0.261 |

1.239 |

1.251 |

| |

68 |

38 |

1.974 |

0.264 |

1.241 |

1.247 |

| |

70 |

34 |

1.885 |

0.308 |

1.403 |

1.380 |

| 10,000 |

96 |

62 |

1.947 |

0.253 |

1.181 |

1.179 |

| |

98 |

48 |

1.894 |

0.301 |

1.379 |

1.357 |

| |

100 |

54 |

1.972 |

0.284 |

1.334 |

1.322 |

Table 6.

Percentage points for . Entries in the table are x such that . The upper number in a double entry is the critical value calculated by using the gamma distribution; the lower is that bases on the sample distribution.

Table 6.

Percentage points for . Entries in the table are x such that . The upper number in a double entry is the critical value calculated by using the gamma distribution; the lower is that bases on the sample distribution.

| n |

Percentage points for the following values of p: |

|

|

|

|

n |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 500 |

0.037 |

0.061 |

0.090 |

0.137 |

0.177 |

0.215 |

0.251 |

0.443 |

0.717 |

0.798 |

0.901 |

1.041 |

1.273 |

1.498 |

1.788 |

2.495 |

500 |

| |

0.121 |

0.145 |

0.167 |

0.201 |

0.231 |

0.259 |

0.285 |

0.430 |

0.650 |

0.722 |

0.825 |

0.964 |

1.243 |

1.589 |

2.054 |

3.194 |

|

| 1,000 |

0.037 |

0.059 |

0.087 |

0.129 |

0.164 |

0.198 |

0.230 |

0.397 |

0.633 |

0.702 |

0.790 |

0.909 |

1.106 |

1.297 |

1.542 |

2.138 |

1,000 |

| |

0.107 |

0.129 |

0.152 |

0.186 |

0.212 |

0.235 |

0.259 |

0.382 |

0.569 |

0.641 |

0.727 |

0.859 |

1.084 |

1.361 |

1.754 |

2.700 |

|

| 2,000 |

0.040 |

0.064 |

0.095 |

0.143 |

0.185 |

0.224 |

0.262 |

0.461 |

0.745 |

0.829 |

0.935 |

1.080 |

1.320 |

1.553 |

1.853 |

2.583 |

2,000 |

| |

0.117 |

0.142 |

0.169 |

0.206 |

0.238 |

0.267 |

0.296 |

0.443 |

0.679 |

0.759 |

0.863 |

1.023 |

1.304 |

1.625 |

2.072 |

3.278 |

|

| 5,000 |

0.037 |

0.0624 |

0.096 |

0.145 |

0.189 |

0.230 |

0.270 |

0.482 |

0.785 |

0.875 |

0.989 |

1.145 |

1.403 |

1.654 |

1.978 |

2.769 |

5,000 |

| |

0.119 |

0.148 |

0.176 |

0.217 |

0.250 |

0.279 |

0.306 |

0.463 |

0.712 |

0.794 |

0.907 |

1.090 |

1.380 |

1.693 |

2.235 |

3.403 |

|

| 10,000 |

0.040 |

0.066 |

0.097 |

0.147 |

0.189 |

0.228 |

0.267 |

0.468 |

0.754 |

0.840 |

0.947 |

1.093 |

1.334 |

1.569 |

1.871 |

2.606 |

10,000 |

| |

0.118 |

0.141 |

0.169 |

0.209 |

0.242 |

0.270 |

0.298 |

0.449 |

0.692 |

0.770 |

0.880 |

1.045 |

1.322 |

1.610 |

2.048 |

3.252 |

|

Table 7.

Comparison of test power with gamma and empirical quantiles, with a significance level of .

Table 7.

Comparison of test power with gamma and empirical quantiles, with a significance level of .

| |

|

|

|

|

|

empirical |

test |

| n |

|

|

a |

b |

quantile

|

quantile

|

power |

| 500 |

4 |

2 |

6.323 |

0.087 |

0.962 |

0.905 |

0.564 |

| |

6 |

3 |

2.302 |

0.165 |

0.865 |

0.689 |

0.615 |

| |

8 |

4 |

3.592 |

0.096 |

0.693 |

0.684 |

0.818 |

| |

18 |

11 |

2.254 |

0.190 |

0.982 |

0.968 |

0.956 |

| |

20 |

11 |

2.109 |

0.238 |

1.174 |

1.165 |

0.928 |

| |

22 |

12 |

1.938 |

0.274 |

1.273 |

1.243 |

0.930 |

| 1,000 |

4 |

2 |

13.991 |

0.049 |

1.017 |

1.004 |

0.875 |

| |

6 |

3 |

6.924 |

0.060 |

0.709 |

0.680 |

0.958 |

| |

8 |

4 |

5.350 |

0.064 |

0.623 |

0.621 |

0.981 |

| |

26 |

13 |

2.083 |

0.231 |

1.128 |

1.116 |

0.999 |

| |

28 |

13 |

1.993 |

0.267 |

1.266 |

1.270 |

0.997 |

| |

30 |

19 |

2.064 |

0.228 |

1.106 |

1.084 |

0.999 |

| 2,000 |

4 |

2 |

27.702 |

0.032 |

1.202 |

1.196 |

0.990 |

| |

6 |

3 |

14.850 |

0.033 |

0.736 |

0.731 |

0.999 |

| |

8 |

4 |

9.147 |

0.041 |

0.612 |

0.607 |

0.999 |

| |

40 |

18 |

1.922 |

0.283 |

1.308 |

1.296 |

1 |

| |

42 |

22 |

1.972 |

0.267 |

1.259 |

1.246 |

1 |

| |

44 |

22 |

1.953 |

0.282 |

1.320 |

1.304 |

1 |

| 5,000 |

4 |

2 |

69.609 |

0.019 |

1.633 |

1.631 |

1 |

| |

6 |

3 |

35.490 |

0.020 |

0.921 |

0.920 |

1 |

| |

8 |

4 |

21.383 |

0.023 |

0.694 |

0.694 |

1 |

| |

66 |

36 |

1.993 |

0.261 |

1.239 |

1.251 |

1 |

| |

68 |

38 |

1.974 |

0.264 |

1.241 |

1.247 |

1 |

| |

70 |

34 |

1.885 |

0.308 |

1.403 |

1.380 |

1 |

| 10,000 |

4 |

2 |

132.233 |

0.014 |

2.155 |

2.154 |

1 |

| |

6 |

3 |

70.155 |

0.013 |

1.171 |

1.170 |

1 |

| |

8 |

4 |

41.810 |

0.015 |

0.839 |

0.838 |

1 |

| |

96 |

62 |

1.947 |

0.253 |

1.181 |

1.179 |

1 |

| |

98 |

48 |

1.894 |

0.301 |

1.379 |

1.357 |

1 |

| |

100 |

54 |

1.972 |

0.284 |

1.334 |

1.322 |

1 |

Table 8.

Comparison between and KS test power, with a significance level of and large values for n.

Table 8.

Comparison between and KS test power, with a significance level of and large values for n.

| |

|

|

|

|

Gamma |

sample |

power |

power |

error |

| n |

|

|

a |

b |

|

quantile

|

|

KS |

rate KS |

| 500 |

4 |

2 |

6.323 |

0.087 |

0.962 |

0.905 |

0.564 |

0.958 |

0.763 |

| |

6 |

3 |

2.302 |

0.165 |

0.865 |

0.689 |

0.615 |

0.958 |

0.963 |

| |

8 |

4 |

3.592 |

0.096 |

0.693 |

0.684 |

0.818 |

0.959 |

0.987 |

| |

18 |

11 |

2.254 |

0.190 |

0.982 |

0.968 |

0.956 |

0.960 |

0.999 |

| |

20 |

11 |

2.109 |

0.238 |

1.174 |

1.165 |

0.928 |

0.958 |

1 |

| |

22 |

12 |

1.938 |

0.274 |

1.273 |

1.243 |

0.930 |

0.960 |

1 |

| 1,000 |

4 |

2 |

13.991 |

0.049 |

1.017 |

1.004 |

0.875 |

0.911 |

0.691 |

| |

6 |

3 |

6.924 |

0.060 |

0.709 |

0.680 |

0.958 |

0.912 |

0.913 |

| |

8 |

4 |

5.350 |

0.064 |

0.623 |

0.621 |

0.981 |

0.911 |

0.974 |

| |

26 |

13 |

2.083 |

0.231 |

1.128 |

1.116 |

0.999 |

0.913 |

1 |

| |

28 |

13 |

1.993 |

0.267 |

1.266 |

1.270 |

0.997 |

0.914 |

1 |

| |

30 |

19 |

2.064 |

0.228 |

1.106 |

1.084 |

0.999 |

0.913 |

1 |

| 2,000 |

4 |

2 |

27.702 |

0.032 |

1.202 |

1.196 |

0.990 |

0.836 |

0.528 |

| |

6 |

3 |

14.850 |

0.033 |

0.736 |

0.731 |

0.999 |

0.836 |

0.897 |

| |

8 |

4 |

9.147 |

0.041 |

0.612 |

0.607 |

0.999 |

0.836 |

0.977 |

| |

40 |

18 |

1.922 |

0.283 |

1.308 |

1.296 |

1 |

0.836 |

1 |

| |

42 |

22 |

1.972 |

0.267 |

1.259 |

1.246 |

1 |

0.838 |

1 |

| |

44 |

22 |

1.953 |

0.282 |

1.320 |

1.304 |

1 |

0.837 |

1 |

| 5,000 |

4 |

2 |

69.609 |

0.019 |

1.633 |

1.631 |

1 |

0.635 |

0.462 |

| |

6 |

3 |

35.490 |

0.020 |

0.921 |

0.920 |

1 |

0.635 |

0.818 |

| |

8 |

4 |

21.383 |

0.023 |

0.694 |

0.694 |

1 |

0.635 |

0.959 |

| |

66 |

36 |

1.993 |

0.261 |

1.239 |

1.251 |

1 |

0.638 |

1 |

| |

68 |

38 |

1.974 |

0.264 |

1.241 |

1.247 |

1 |

0.637 |

1 |

| |

70 |

34 |

1.885 |

0.308 |

1.403 |

1.380 |

1 |

0.637 |

1 |

Table 9.

Rejection rates of test statistic, considering all possible values, with a significance level of and , for the three stock prices considered.

Table 9.

Rejection rates of test statistic, considering all possible values, with a significance level of and , for the three stock prices considered.

| Stock |

n |

|

|

|

|

| Apple |

3,122 |

[4,55] |

[2,27] |

88% |

92% |

| Google |

2,989 |

[4,54] |

[2,27] |

2% |

10% |

| GS |

2,819 |

[4,53] |

[2,26] |

16% |

20% |

Table 10.

Rejection rates of test statistic, considering values that are at least 44, with a significance level of and , for the three stock prices considered.

Table 10.

Rejection rates of test statistic, considering values that are at least 44, with a significance level of and , for the three stock prices considered.

| Stock |

n |

|

|

|

|

| Apple |

3,122 |

[44,55] |

[22,27] |

100% |

100% |

| Google |

2,989 |

[44,54] |

[22,27] |

9% |

27% |

| GS |

2,819 |

[44,53] |

[22,26] |

70% |

80% |