Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Betalain Extracts Preparation and Conservation Treatments

2.3. Physicochemical Characteristics of the Betalain Extracts and Extraction Yield

2.4. Shelf-Life Analysis Of Bofalain Extracts

2.5. Color Stability Analysis of Betalain Extracts

2.6. Application of Extracts in Cottage Cheese

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

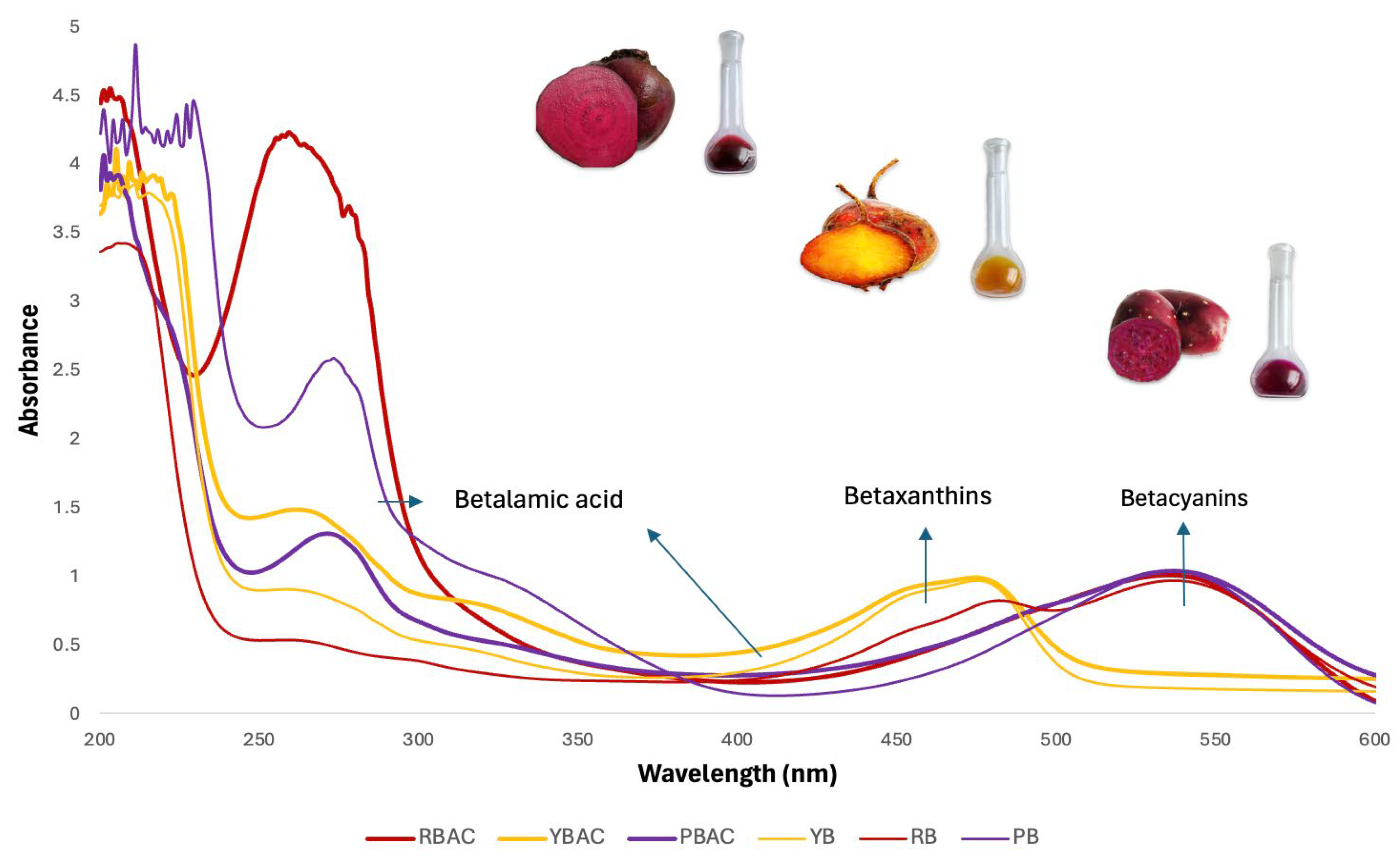

3.1. Physicochemical Characteristics and Yield of Betalain Extracts

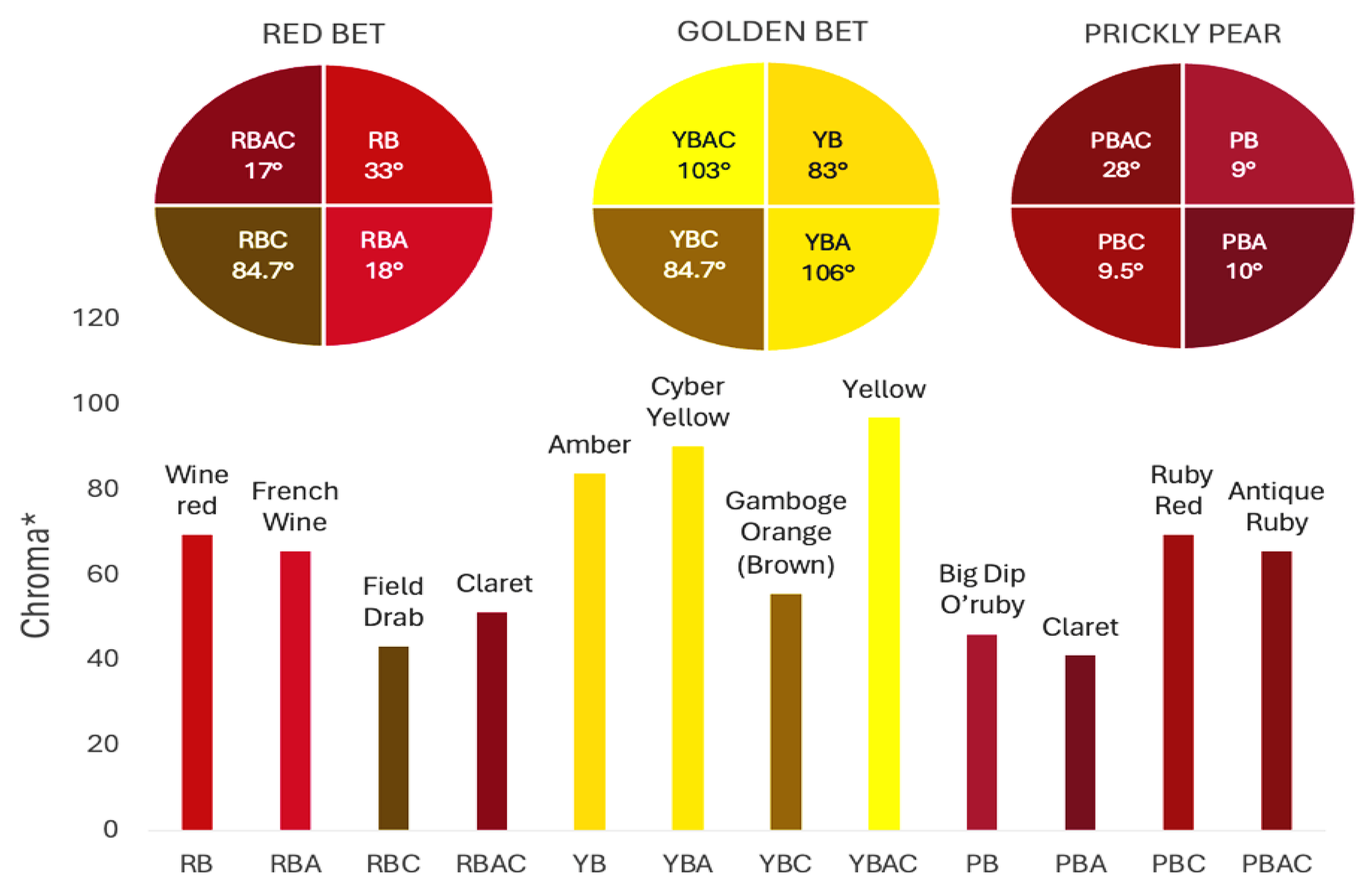

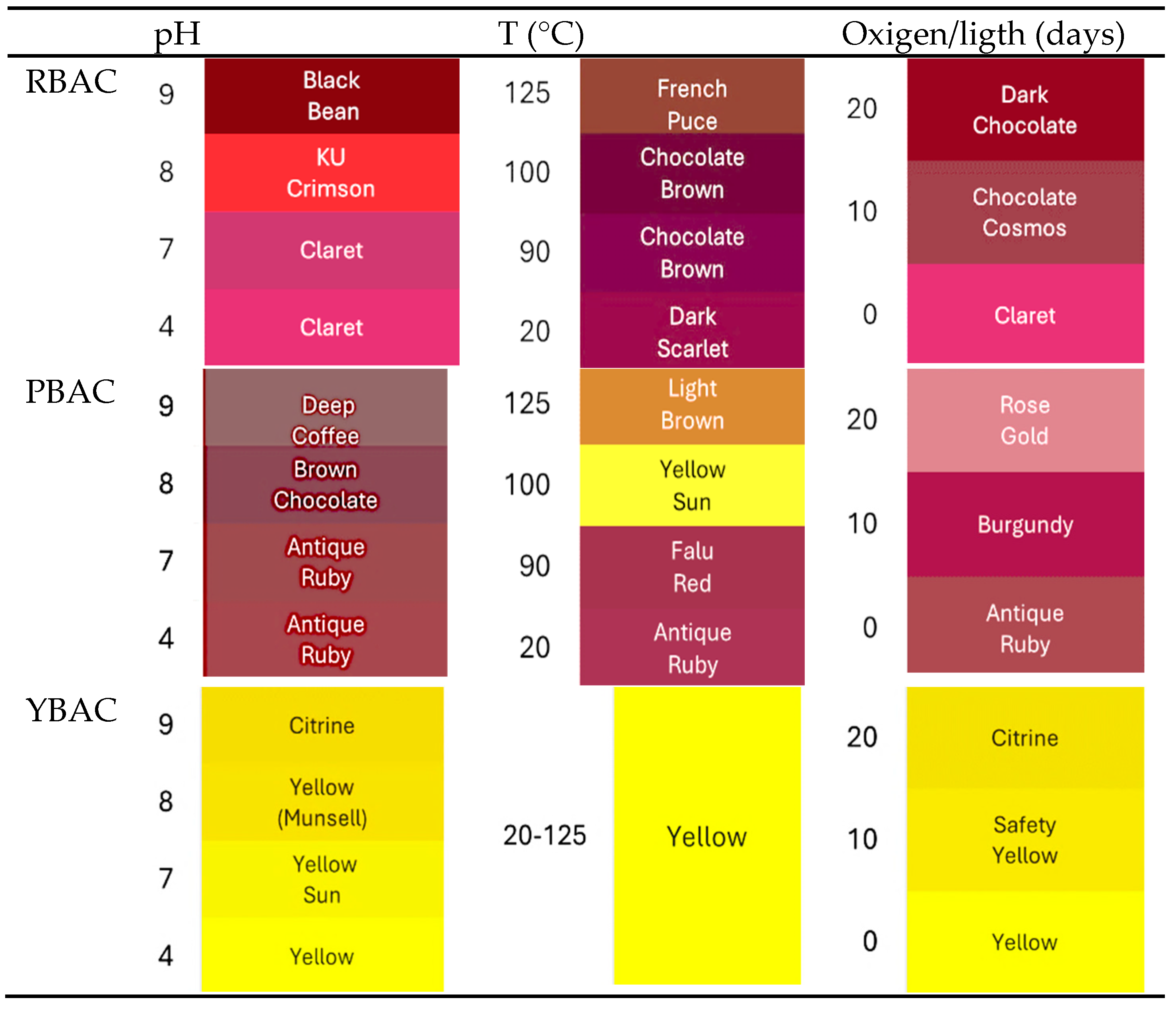

3.2. Colorimetric Characteristics of Betalain Extracts

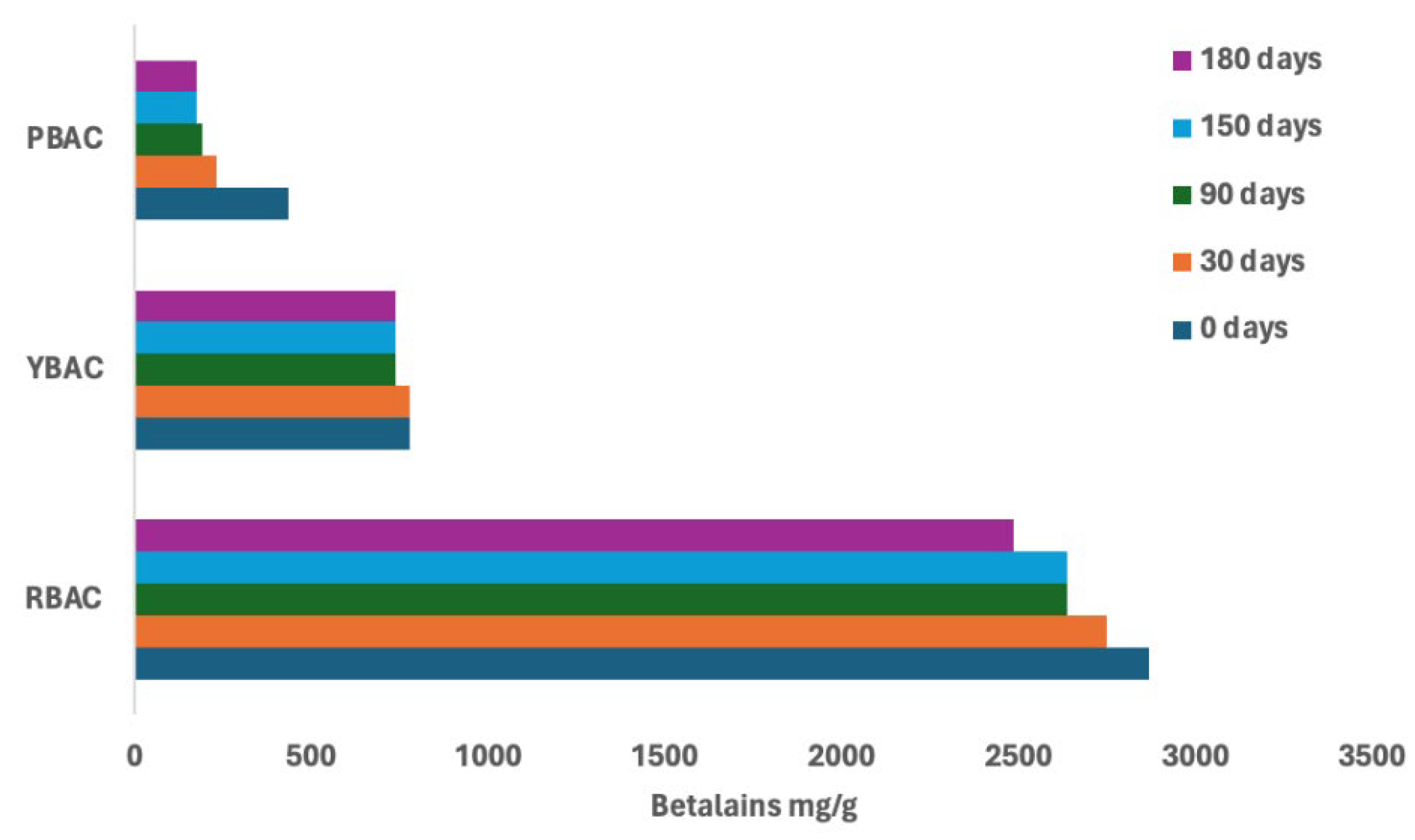

3.3. Shelf-Life Analysis of Betalain Extracts. Effect of Organic Acid Addition and Concentration

3.4. Color Stability Analysis of Betalain Extracts

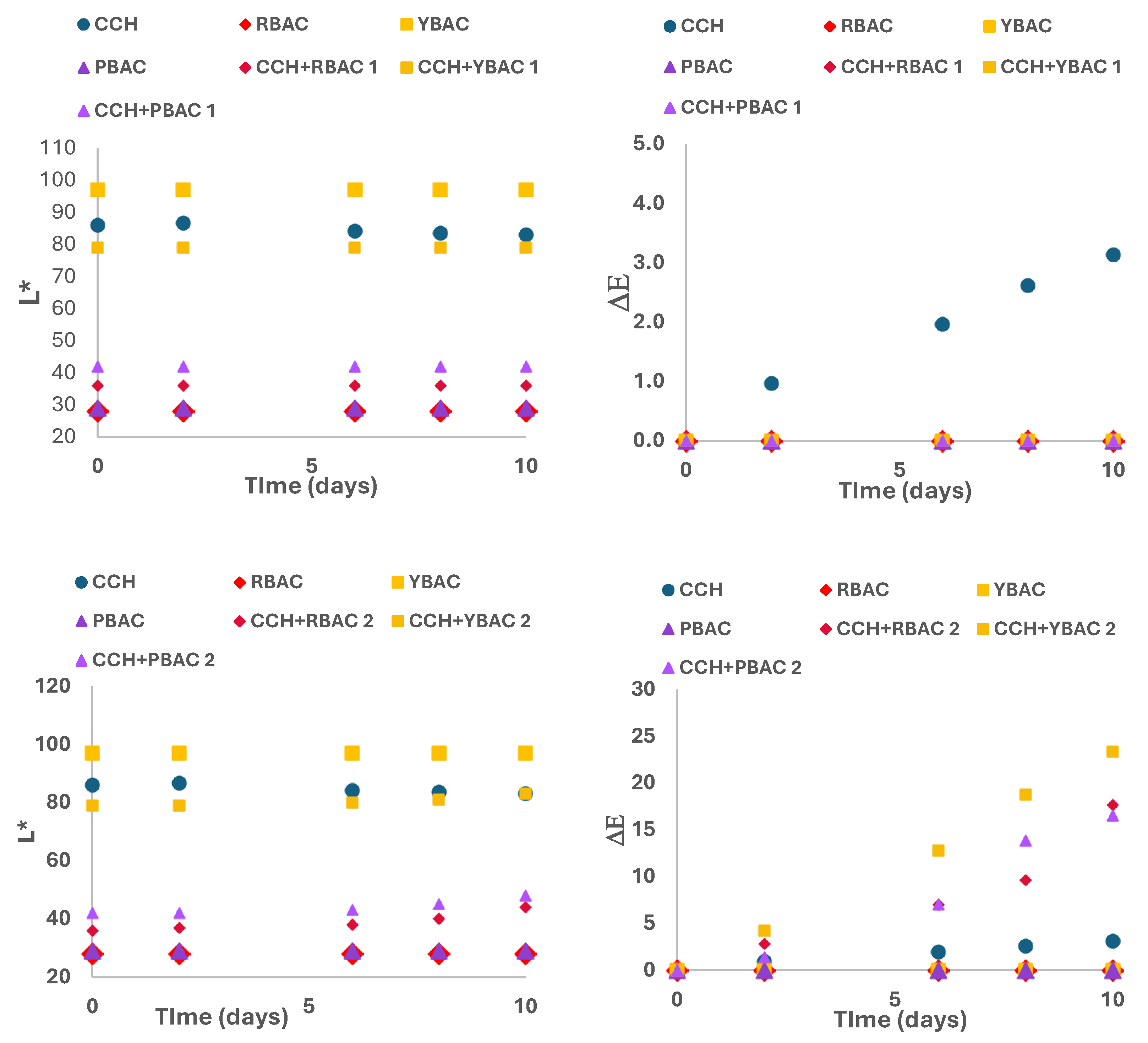

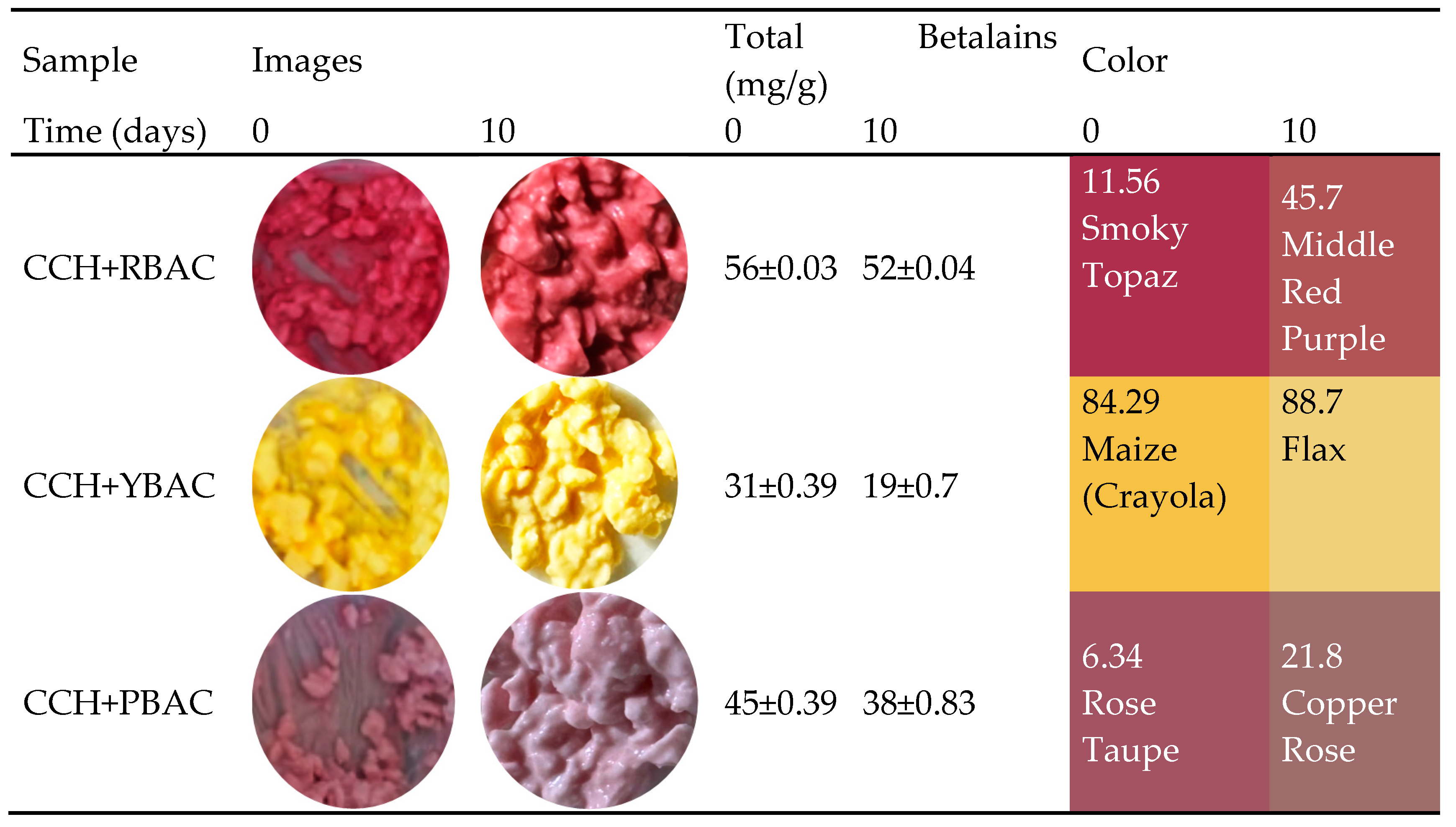

3.5. Shelf-Life Analysis of Betalain Extracts on Cottage Cheese

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Polturak, G. , & Aharoni, A. (s. f.). “La Vie en Rose”: Biosynthesis, Sources, and Applications of Betalain Pigments. Molecular Plant, 2018, 11, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calva-Estrada, S. , Jiménez-Fernández, M., & Lugo-Cervantes, E. Betalains and their applications in food: The current state of processing, stability and future opportunities in the industry. Food chem-mol sc, 2022; 4, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaari, M. , Elhadef, K., Akermi, S., Hlima, H. B., Fourati, M., Mtibaa, A. C., Ennouri, M., D’Amore, T., Ali, D. S., Mellouli, L., Khaneghah, A. M., & Smaoui, S. Potentials of beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) peel extract for quality enhancement of refrigerated beef meat. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods, 2023; 15, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, I., da Silva Martins, L.H., Campos, R., Siquiera, C., & Sarkis, M.R. Betalains from vegetable peels: Extraction methods, stability, and applications as natural food colorants. Food Res Inter. 2024, 195, 114956. [CrossRef]

- Tekin, İ. , Özcan, K., & Ersus, S. Optimization of ionic gelling encapsulation of red beet (Beta vulgaris L.) juice concentrate and stability of betalains. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol, 2023; 51, 102774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazervazifeh, A. , Rezazadeh, A., Banihashemi, A., Ghasempour, Z., & Kia, E. M. Pulsed microwave radiation for extraction of betalains from red beetroot: Engineering and technological aspects. Process Biochem., 2023, 134, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otálora, M. C. , Wilches-Torres, A., & Castaño, J. A. G. Microencapsulation of Betaxanthin Pigments from Pitahaya (Hylocereus megalanthus) By-Products: Characterization, Food Application, Stability, and In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Foods, 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boravelli, J. A. R. , & Vir, A. B. Continuous flow aqueous two-phase extraction of betalains in millifluidic channel. Chem Eng J, 2024, 495, 153265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Huerta, A. , Flores-Andrade, E., Jiménez-Fernández, M., Beristain, C., & Pascual-Pineda, L. Microencapsulation of betalains by foam fluidized drying. J. Food Eng., 2023, 359, 111701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, B. A. , Yolaçaner, E. T., & Aytaç, S. A. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of betalain-rich bioactive compounds of prickly pear fruit: an optimization study. Food Biosci. 2024; 61, 104734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R. M. , Queffelec, J., Flórez-Fernández, N., Saraiva, J. A., Torres, M. D., Cardoso, S. M., & Domínguez, H. Production of betalain-rich Opuntia ficus-indica peel flour microparticles using spray-dryer: A holist approach. LWT, 2023, 186, 115241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaari, M. , Elhadef, K., Akermi, S., Tounsi, L., Hlima, H. B., Ennouri, M., Abdelkafi, S., Agriopoulou, S., Ali, D. S., Mellouli, L., & Smaoui, S. Development of a novel colorimetric pH-indicator film based on CMC/flaxseed gum/betacyanin from beetroot peels: A powerful tool to monitor the beef meat freshness. Sustainable Chem Pharm2024, 39, 101543. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D. , Kuksal, K., Yadav, K., Yadav, S. K., Zhang, Y., & Nile, S. H. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and encapsulation of betalain from prickly pear: Process optimization, in-vitro digestive stability, and development of functional gummies. Ultrason Sonochem, 2024, 108, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, D. , Kuksal, K., Sharma, A., Soni, N., Kumari, S., & Nile, S. H. Postharvest integration of prickly pear betalain-enriched gummies with different sugar substitutes for decoding diabetes type-II and skin resilience - in vitro and in silico study. Food Chem. 2025; 464, 141612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimen, I. B. , Najar, T., & Abderrabba, M. Chemical and Antioxidant Properties of Betalains. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017; 65, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I. R. , Da Silva Martins, L. H., Chisté, R. C., Picone, C. S. F., & Joele, M. R. S. P. Betalains from vegetable peels: Extraction methods, stability, and applications as natural food colorants. Food Res. Int, 2024; 195, 114956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visockis, M. , Bobinaitė, R., Ruzgys, P., Barakauskas, J., Markevičius, V., Viškelis, P., & Šatkauskas, S. Assessment of plant tissue disintegration degree and its related implications in the pulsed electric field (PEF)–assisted aqueous extraction of betalains from the fresh red beetroot. Innov food sci emerg, 2021; 73, 102761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandía-Herrero, F. , Escribano, J., & García-Carmona, F. Characterization of the Activity of Tyrosinase on Betanidin. J. Agric. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. , Jayaprakasha, G. K., & Patil, B. S. UPLC-QTOF-MS fingerprinting combined with chemometrics to assess the solvent extraction efficiency, phytochemical variation, and antioxidant activities of Beta vulgaris L. JFDA. [CrossRef]

- Gandía-Herrero, F. , Escribano, J., & García-Carmona, F. Structural implications on color, fluorescence, and antiradical activity in betalains. Planta. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. , Wang, Y., Deng, Y., Yao, Q., & Xiong, A. Synthesis of betanin by expression of the core betalain biosynthetic pathway in carrot. Hortic. Plant J. [CrossRef]

- Stintzing, F. C. , Schieber, A., & Carle, R. Identification of Betalains from Yellow Beet (Beta vulgarisL.) and Cactus Pear [Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill.] by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography−Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ponce, H. A. , Martínez-Saldaña, M. C., Tepper, P. G., Quax, W. J., Buist-Homan, M., Faber, K. N., & Moshage, H. Betacyanins, major components in Opuntia red-purple fruits, protect against acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Food Res. Int. 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Santiago, V. , Cavia, M. M., Alonso-Torre, S. R., & Carrillo, C. Relationship between color and betalain content in different thermally treated beetroot products. J. Food Sci. Technol, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. P. P. , Bolanho, B. C., Stevanato, N., Massa, T. B., & Silva, C. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of red beet pigments (Beta vulgaris L.): Influence of operational parameters and kinetic modeling. J Food Process Preserv. [CrossRef]

- Masithoh, R. E. , Pahlawan, M. F. R., Arifani, E. N., Amanah, H. Z., & Cho, B. K. Determination of the Betacyanin and Betaxanthin Contents of Red Beet (Beta Vulgaris) Powder Using Partial Least Square Regression Based on Visible-Near Infrared Spectra. Trends In Sciences, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhikara, N. , Kushwaha, K., Sharma, P., Gat, Y., & Panghal, A. Bioactive compounds of beetroot and utilization in food processing industry: A critical review. Food Chem. [CrossRef]

- Attia, G. Y. , Moussa, M. M., & Sheashea, E. E. D. R. CHARACTERIZATION OF RED PIGMENTS EXTRACTED FROM RED BEET (BETA VULGARIS, l.) AND ITS POTENTIAL USES AS ANTIOXIDANT AND NATURAL FOOD COLORANTS. Egypt.J. Agric. Res. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbach, K. M. , Rohe, M., Stintzing, F. C., & Carle, R. Structural and chromatic stability of purple pitaya (Hylocereus polyrhizus [Weber] Britton & Rose) betacyanins as affected by the juice matrix and selected additives. Food Res. Int, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otalora, C. , Bonifazi, E., Fissore, E., Basanta, F., & Gerschenson, L. Thermal Stability of Betalains in By-Products of the Blanching and Cutting of Beta vulgaris L. var conditiva. Pol. J. Of Food and Nutrition Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, H. M. Betalains: properties, sources, applications, and stability – a review. IJFST, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Amaya, D. B. Update on natural food pigments - A mini-review on carotenoids, anthocyanins, and betalains. Food Res. Int. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska-Bartosz, I. , & Bartosz, G. Biological Properties and Applications of Betalains. Molecules, 2021; 26, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancha, M. A. F., Monterrubio, A. L. R., Vega, R. S., & Martínez, A. C. Estructura y Estabilidad de las Betalanas. Interciencia, 2019, 6(44). https://www.redalyc.org/journal/339/33960068002/html/.

- Sutor-Świeży, K. , Proszek, J., Popenda, Ł., & Wybraniec, S. Influence of Citrates and EDTA on Oxidation and Decarboxylation of Betacyanins in Red Beet (Beta vulgaris L.) Betalain-Rich Extract. Molecules, 2022; 27, 9054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, J. A. , Victoria, M. T. C. Y., & Barragán-Huerta, B. E. Betaxanthins and antioxidant capacity in Steno cereus pruinosus: Stability and use in food. Food Res. Int., 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneşer, O. Pigment and color stability of beetroot betalains in cow milk during thermal treatment. Food Chem. 2015; 196, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Betalains Extract | Yield (mL/100 g FW) | pH | Betaxanthins (mg/g) | Betacyanins (mg/g) | Total betalains (mg/g) | °Bx | TDS (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RB | 30 | 6.7±0.01 | 392.3±2.7 | 522.2±6.2 | 914.5±8.9 | 12±0.1 | 94.7±1 |

| RBA | 30 | 4.3±0.01 | 666.73±5.2 | 1068.07±8.8 | 1734.8±14 | 12±0.5 | 94.6±2 |

| RBC | 6 | 6.5±0.02 | 267.11±1 | ND | 267.1±1 | 4±1 | 44±2 |

| RBAC | 6 | 4.3±0.3 | ND | 2866.97±5.04 | 2866.9±5.04 | 61±1 | 243.1±4 |

| YB | 80 | 6.8±0.01 | 86.4±0.63 | ND | 86.4±0.63 | 12±0.1 | 15±1 |

| YBA | 80 | 4.1±0.1 | 105.94±0.29 | ND | 105.9±0.29 | 12±0.1 | 34.2±1 |

| YBC | 16 | 6.8±0.1 | ND | ND | ND | 4±0.1 | 7±1 |

| YBAC | 16 | 4.5±0.2 | 776.38±0.35 | ND | 776.3±0.35 | 61±0.1 | 68.7±1 |

| PB | 44 | 5.7±0.5 | ND | 193.2±13.42 | 193.2±13.42 | 12±0.5 | 111.6±1 |

| PBA | 44 | 4.1±0.3 | ND | 223.9±13.24 | 223.9±13.24 | 11.5±1 | 185.5±3 |

| PBC | 9 | 6.4±0.5 | ND | 83.6±0.43 | 83.6±0.43 | 27.4±1 | 189.2±2 |

| PBAC | 9 | 4.3±1 | ND | 433.9±12 | 433.9±12 | 10±2 | 237.2±4 |

| Source | Shelf-life (storage days) | Betalains content (mg/g) | |||

| Red beetroot | RBAC | RB | RBA | RBC | |

| 0 | 2867±5 | 914±9 | 1735±14 | 267±1 | |

| 180 | 2485±1 | 0 | 693.9±14 | 0 | |

| Betalains maintenance % | 87 | 0 | 40 | 0 | |

| ΔE | |||||

| Yellow beetroot | YBAC | YB | YBA | YBC | |

| 0 | 776±1 | 86±1 | 106±1 | 0 | |

| 180 | 791±1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Betalains maintenance % | 95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Purple prickly pear | PBAC | PB | PBA | PBC | |

| 0 | 434±12 | 193±13 | 224±13 | 84±0.5 | |

| 180 | 177±5 | 44±2 | 78.5±2 | 0 | |

| Betalains maintenance % | 50 | 23 | 35 | 0 | |

|

Betalain extracts |

RBAC | YBAC | PBAC | |||||||

|

Exposure Factors |

Order |

Betalains (mg/g) |

Betalains retention(%) |

Color difference ΔΕ |

Betalains (mg/g) |

Betalains retention (%) |

Color difference ΔΕ |

Betalains (mg/g) |

Betalains retention (%) |

Color difference ΔΕ |

| pH | 4 | 2867±0.5 | 100 | 0 | 776±0.3 | 100 | 0 | 434±0.3 | 100 | 0 |

| 7 | 1442±0.2 | 50 | 27 | 727±0.5 | 94 | 10 | 420±0.1 | 97 | 10 | |

| 8 | 1021±0.1 | 36 | 60 | 696±0.3 | 90 | 15 | 425±0.6 | 60 | 49 | |

| 9 | 501±0.1 | 18 | 72 | 672±0.8 | 87 | 25 | 421±0.4 | 47 | 57 | |

| Temperature (°C) | 20 | 2801±0.5 | 98 | 8 | 776±0.3 | 100 | 0 | 115±.5 | 91 | 86 |

| 90 | 2437±0.6 | 85 | 38 | 776±0.3 | 100 | 0 | 75±0.3 | 85 | 90 | |

| 100 | 1581±0.5 | 55 | 53 | 776±0.3 | 100 | 0 | 14±0.1 | 50 | >100 | |

| 125 | 433±0.5 | 20 | 74 | 776±0.3 | 100 | 0 | 5±0.1 | 1 | >100 | |

| Oxigen and light (Days) | 0 | 2867±0.2 | 100 | 0 | 776±0.3 | 100 | 0 | 434±0.4 | 100 | 0 |

| 10 | 2181±1.3 | 76 | 35 | 384±0.7 | 50 | 40 | 286±1.6 | 66 | 26 | |

| 20 | 800±1.6 | 250 | 75 | 297±2.9 | 38 | 50 | 286±2.1 | 56 | 32 | |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).