Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Road Markings

2.1. Properties

- Retroreflectivity – the phenomenon of returning the light from vehicle’s headlights back toward the driver, measured as coefficient of retroreflected luminance (RL) and expressed in mcd/m²/lx; RL can be also measured under the conditions of wetness (RW). While RL could be theoretically measured also during rain (RR), such measurements in the field are not being done due to the absence of reliable methodology. Retroreflectivity is obtained due to the GBs and their embedment to circa 50–60% in the coating layer [25,26]. The effect of RL on visibility and contrast of RMs has been analysed [27,28]. Studies of drivers’ visual needs indicated that RL >150 mcd/m²/lx should be maintained at all times [29].

- Skid resistance – measured using British Pendulum skid resistance tester (SRT) and expressed in unitless Pendulum Test Value (PTV). Skid resistance is furnished by the retroreflective layer (in RMs applied in thick layers also by the coarse fillers in the coating layer).

- Functional service life – RMs meet or exceed the functional properties demanded in specifications, particularly RL, Qd, and skid resistance.

- Physical service life – RMs no longer meet the demanded functional properties but remain on the road surface.

- End-of-life – RMs are physically eroded (i.e. completely abraded) and cease being visible for road users.

2.2. Materials for Road Markings

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. LCA Assumptions

- Production, including (a) preparation of the raw materials, including their mining and/or production, (b) transport of the raw materials to the manufacture site, and (c) manufacturing process itself, including packaging. The manufacture location for the retroreflective layer components was chosen Amstetten (Austria) and for the coating layer Frankfurt am Main (Germany); choice of these locations affected the environmental costs of transportation and energy.

- Installation, including transport from the manufacturing sites and the energy used for installation. As installation location was chosen Regensburg (Germany) as being roughly mid-point between the manufacturing sites.

- Waste disposal of the packaging and residual materials during production and application.

- The following were disregarded (assumed nil values):

- The use stage – does not apply because RMs are passive products.

- Reuse, recovery, recycling – omitted because RMs usually do not undergo such processes. However, one should observe that during road surface renovation, the RMs are typically reused or recycled together with the asphalt or concrete. Furthermore, during realignment of the road delineation or when the layer thickness of the RMs becomes excessive due to stacking [32], they may be mechanically removed and disposed (there might be possibility of recycling).

3.2. Materials

3.3. Carbon Footprint Components

3.4. Service Life of Road Markings

4. Results

5. Discussion

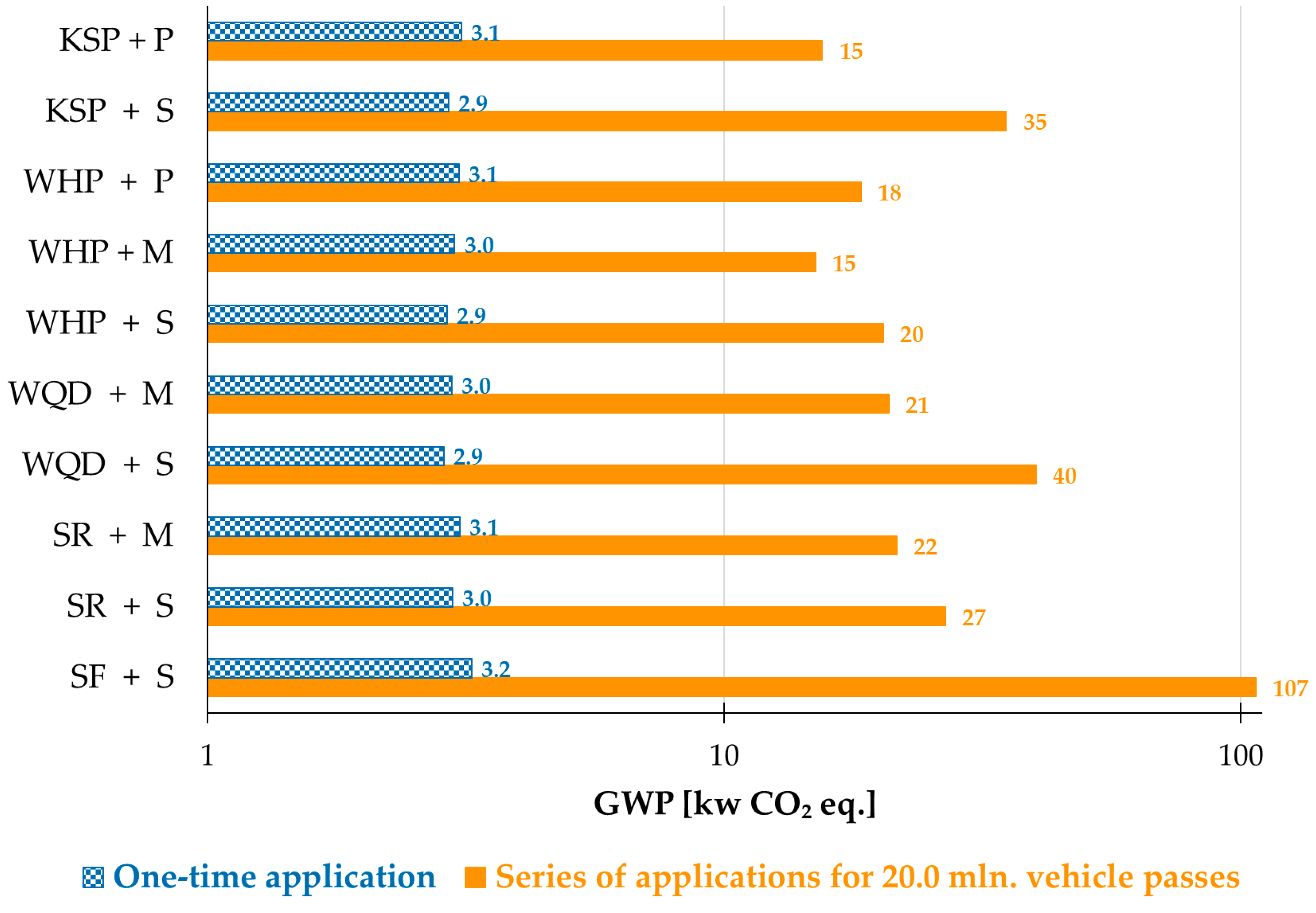

- Very high GWP – >100 kg CO₂ eq./m² in case of the low-end paint. This should be considered as grossly irregular but is highly probable. The unexpected very low performance prompted repeat field test, where essentially the same results were measured [58]. It may be hypothesised that the absence of toluene, an excellent solvent for RMs that facilitates the adhesion to asphalt surface [59], could be playing a role. This underlines the necessity of proper field testing, as the paint was homologated at the roundtable for the use in Germany [33].

- Medium GWP – 30–45 kg CO₂ eq./m² in cases of the typical quick-dry waterborne paint and sprayed cold plastic, both reflectorised with the ‘Standard’ GBs.

- Low GWP – 20–30 kg CO₂ eq./m² in majority of cases.

- Minimal GWP – <20 kg CO₂ eq./m², in cases of sprayed cold plastic and high-performance waterborne paint, both reflectorised with the inclusion of ‘Premium’ GBs. One should observe that the use of ‘Premium’ GBs, with RI 1.6–1.7, despite environmental expense of production much higher than in case of ‘Standard’ GBs, did not cause the increase in long-term GWP – contrariwise. Even though the reported RL rate of decay with such GBs was higher than in case of the ‘Standard’ GBs [21], the much higher initial RL still permitted for the obtention of prolonged functional service life, which lowered the long-term environmental burden.

- The analysis was done based on ‘cradle-to-end of functional service life’ and not ‘cradle-to-grave’. The data for the physical service life and end-of-life stages is not available; this remains amongst major research needs.

- Exclusion of the typical peroxide initiator, necessary for formation of cold plastic RMs has to be noted as it could potentially affect the outcome. Since LCA data for such material was not available, its carbon footprint was but omitted.

- In all of the analysed cases, it was assumed that renewal would occur immediately when RL <150 mcd/m²/lx was measured. In practice, even in the mild climate in Croatia, there are no road marking activities during winter. Hence, in practice, renewals could be delayed until spring when RL <150 mcd/m²/lx would be measured.

- The selection of manufacture and application locations, along with the local requirements related to materials composition, did affect the outcome of the LCA.

- The chosen materials, even though purchased commercially from several manufacturers, do not represent the full spectrum of available products. In addition, some uncertainties related to the composition remain.

- The absence of comparable data for thick layer RMs was the reason for their exclusion from analysis. Materials like thermoplastic (designed for slow wear-off to continuously furnish RL), cold plastic (capable of furnishing exquisite physical service life), and structured cold plastic (furnishing extended functional service life and improved visibility under wet conditions) ought to be tested.

- This analysis was based on RL under dry conditions and the most-used regions of transverse lines. Similar evaluation based on RW should be performed. Such testing would reveal any possible differences due to dissimilar materials that can provide retroreflectivity under wet conditions. Structured thick layer RMs and tapes should also be included because of their design as Type II RMs.

- Evaluation based on the least-used regions of the transverse lines should be done; major differences in performance, not paralleling the tested most-used regions, were measured [21].

- Physical service life of various RMs was not included. At the test field, a low-end waterborne paint (excluded from this analysis) failed completely [21] – it underwent erosion during winter exposure even in the absence of meaningful snow ploughing.

- The LCA data was calculated for manufacture at modern production facilities in Europe. Large variations are expected for other locations – due to the physical location and the associated transport expenses, due to the used energy and the emissions, and due to the local production processes. The same applies to the application location.

- Obstruction of traffic due to road marking activities was not included, even though – through increased emissions from queueing up vehicles – it may affect the results. Only one brief report on this topic was found in the available literature [61]. This corollary aspect remains excluded from the LCA.

- The physical service life (during which abrasion is likely to occur) and the end-of-life considerations were not included. The fate of particles generated from abrasion of RMs remains unknown; while generally they ought to be free from toxic ingredients (like in all of the cases presented herein), in some formulations that are nowadays obsolete and generally banned in Europe, harmful ingredients and pigments were present. It is of utmost importance to carefully assess all possible contamination or toxic effects and separate the current issues from erstwhile.

- The topic of microplastic emissions from RMs, which recently gained scientific attention [15,22], was not addressed in this LCA. The methodology for such inclusion is still being developed [62,63,64]. Nonetheless, one should keep in mind that the emissions of microplastics from RMs occur only after the functional service life is exhausted [15,22] (the exception are thermoplastic RMs due to their design for wear-off), which did not occur in any of the examples presented herein.

- Road safety – the main purpose of installation of RMs – was not included. At present, there is no reliable method for calculating this impact on LCA. The presence of RMs was consistently reported as lowering the number and severity of accidents [4,65]. Also, the increase in RL was positively correlated with the decrease in single vehicle crashes at night [66,67].

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sonnemann, G.; Margni, M. (eds), Life cycle management. SpringerOpen, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Tillman, A.M.; Ekvall, T.; Baumann, H.; Rydberg, T. Choice of system boundaries in life cycle assessment. J. Cleaner Prod. 1994, 2(1), 21-29. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Silva, M.; Klutke, G.A. (eds), Reliability and life-cycle analysis of deteriorating systems. Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.R. Benefit–cost analysis of lane marking. Transport. Res. Record 1992, 1334, 38–45.

- Babić, D.; Fiolić, M.; Babić, D.; Gates, T. Road markings and their impact on driver behaviour and road safety: a systematic review of current findings. J. Adv. Transport. 2020, 7843743. [CrossRef]

- Storsæter, A.D.; Pitera, K.; McCormack, E.D. The automated driver as a new road user. Transport Reviews 2020, 41(5), 533–555. [CrossRef]

- Aryan, Y.; Dikshit, A.K.; Shinde, A.M. A critical review of the life cycle assessment studies on road pavements and road infrastructures. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 336, 117697. [CrossRef]

- Stripple, H. Life cycle assessment of road: a pilot study for inventory analysis. IVL Rapport B 1210 E. IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute: Göteborg, Sweden, 2001.

- Birgisdóttir, H.; Pihl, K.A.; Bhander, G.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Christensen, T.H. Environmental assessment of roads constructed with and without bottom ash from municipal solid waste incineration. Transport. Res. Part D, Transp. Environ. 2006, 11(5), 358–368. [CrossRef]

- Noland, R.B.; Hanson, C. S. Life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions associated with a highway reconstruction: a New Jersey case study. J. Cleaner Prod. 2015, 107, 731–740. [CrossRef]

- Barandica, J.M.; Fernández-Sánchez, G.; Berzosa, Á.; Delgado, J.A.; Acosta, F.J. Applying life cycle thinking to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from road projects. J. Cleaner Prod. 2013, 57, 79–91. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Sánchez, G.; Berzosa, Á.; Barandica, J.M.; Cornejo, E.; Serrano, J.M. Opportunities for GHG emissions reduction in road projects: a comparative evaluation of emissions scenarios using CO₂NSTRUCT. J. Cleaner Prod. 2015, 104, 156–167. [CrossRef]

- Trigaux, D.; Wijnants, L.; De Troyer, F.; Allacker, K. Life cycle assessment and life cycle costing of road infrastructure in residential neighbourhoods. Int. J. Life Cycle Assessm. 2017, 22, 938–951. [CrossRef]

- Verán-Leigh, D.; Larrea-Gallegos, G.; Vázquez-Rowe, I. Environmental impacts of a highly congested section of the Pan-American highway in Peru using life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assessm. 2019, 24, 1496–1514. [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.E.; Pashkevich, A.; Babić, D.; Mosböck, H.; Babić, D.; Żakowska, L. Microplastics and road markings: the role of glass beads and loss estimation. Transport. Res. Part D, Transp. Envir. 2022, 102, 103123. [CrossRef]

- Pocock, B.W.; Rhodes, C.C. Principles of glass-bead reflectorization. Highway Res. Board Bull. 1952, 57, 32–48.

- Cruz, M.; Klein, A.; Steiner, V. Sustainability assessment of road marking systems. Transport. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 869–875. [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.E.; Pashkevich, A.; Żakowska, L. Influence of volatile organic compounds emissions from road marking paints on ground-level ozone formation: case study of Kraków, Poland. Transport. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 714–723. [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, H.; Diederichs, S.K.; Wenker, J.L.; Rüter, S. Environmental product declarations in accordance with EN 15804 and EN 16485—how to account for primary energy of secondary resources?. Environ. Impact Assessm. Rev. 2016, 60, 134–138. [CrossRef]

- Hertwich, E.G.; Mateles, S.F.; Pease, W.S.; McKone, T.E. Human toxicity potentials for life-cycle assessment and toxics release inventory risk screening. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. Int. J. 2001, 20(4), 928–939. [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.E.; Babić, D.; Pashkevich, A. Sustainability of thin layer road markings based on their service life. Transport. Res. Part D, Transp. Envir. 2022, 109, 103339. [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.E.; Pashkevich, A. Road markings and microplastics – a critical literature review. Transport. Res Part D, Transp. Envir. 2023, 119, 103740. [CrossRef]

- European Standard EN 1436. Road marking materials — Road marking performance for road users and test methods. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Burghardt, T.E.; Chistov, O.; Reiter, T.; Popp, R.; Helmreich, B.; Wiesinger, F. Visibility of flat line and structured road markings for machine vision. Case Studies Constr. Mat. 2023, 18, e02048. [CrossRef]

- Vedam, K.; Stoudt, M.D. Retroreflection from spherical glass beads in highway pavement markings. 2: Diffuse reflection (a first approximation calculation). Appl. Optics 1978, 17(12), 1859–1869. [CrossRef]

- Grosges, T. Retro-reflection of glass beads for traffic road stripe paints. Optical Mat. 2008, 30, 1549–1554. [CrossRef]

- Spieringhs, R.M.; Smet, K.; Heynderickx, I.; Hanselaer, P. Road marking contrast threshold revisited. Leukos 2022, 18(4), 493–512. [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, R.; Cao, Q.; Xie, F. Research on the nighttime visibility of white pavement markings. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36533. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-S.; Oh, H.-U. Minimum Retroreflectivity for Pavement Markings by Driver's Static Test Response. J. Eastern Asia Soc. Transport. Studies 2005, 6, 1089–1099. [CrossRef]

- COST 331 – requirements for horizontal road marking. European Commission. Directorate General Transport. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1999.

- Brémond R. Visual performance models in road lighting: a historical perspective. Leukos 2020, 17, 212–241. [CrossRef]

- Technical Report CEN/TR 16958. Road marking materials. Conditions for removing/masking road markings. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- Keppler, R. 15 Jahre Eignungsprüfungen von Markierungssystemen auf der Rundlaufprüfanlage der Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen [in German]. Straßenverkehrstechnik 2005, 49(11), 575–582.

- ONR 22440-1. Bodenmarkierungen. Funktionsdauer – Teil 1: Allgemeines. Ortsgebiet [in German]. Österreichisches Normungsinstitut: Wien, Austria, 2018.

- ONR 22440-2: Bodenmarkierungen. Funktionsdauer – Teil 2: Ortsgebiet [in German]. Österreichisches Normungsinstitut: Wien, Austria, 2018.

- Zusätzlichen Technischen Vertragsbedingungen und Richtlinien für Markierungen auf Straßen (ZTV-M); 2013. Serie: FGSV, Nr. 341 [in German]. FGSV Verlag: Köln, Germany, 2013.

- de Jong, H.; Flapper, J. Titanium dioxide: ruling opacity out of existence? Eur. Coatings J. 2017, 10, 52–55.

- Hassan M. Life-cycle assessment of titanium dioxide coatings. In: Construction Research Congress 2009; Seattle, WA, USA, 5-7 April 2009, pp. 836–845. [CrossRef]

- Stratmann, H.; Hellmund, M.; Veith, U.; End, N.; Teubner, W. Indicators for lack of systemic availability of organic pigments. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 115, 104719. [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.E.; Pashkevich, A. Emissions of volatile organic compounds from road marking paints. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 193, 153–157. [CrossRef]

- van der Kooij, H.M.; Sprakel, J. Watching paint dry; more exciting than it seems. Soft Matter 2015, 11(32), 6353–6359. [CrossRef]

- Kugler, S.; Ossowicz, P.; Malarczyk-Matusiak, K.; Wierzbicka, E. Advances in rosin-based chemicals: the latest recipes, applications and future trends. Molecules 2019, 24(9), 1651. [CrossRef]

- Cashman, S.A.; Moran, K.M.; Gaglione, A.G. Greenhouse gas and energy life cycle assessment of pine chemicals derived from crude tall oil and their substitutes. J. Ind. Ecol. 2016, 20(5), 1108−1121. [CrossRef]

- 44. Deutsche Norm DIN EN 1423. Straßenmarkierungsmaterialien - Nachstreumittel - Markierungs-Glasperlen, Griffigkeitsmittel und Nachstreugemische [in German]. DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung: Berlin, Germany, 2012.

- Burghardt, T.E.; Ettinger, K.; Köck, B.; Hauzenberger, C. Glass beads for road markings and other industrial usage: crystallinity and hazardous elements. Case Studies Constr. Mat. 2022, 17, e01213. [CrossRef]

- Migaszewski, Z.M.; Gałuszka, A.; Dołęgowska, S.; Michalik, A. Glass microspheres in road dust of the city of Kielce (south-central Poland) as markers of traffic-related pollution. J. Hazard. Mat. 2021, 413, 125355. [CrossRef]

- Plueddemann, E.P. Adhesion through silane coupling agents. J. Adhesion 1970, 2(3), 184–201. [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.M.; Datta S. Effect of glass bead refractive index on pavement marking retroreflectivity considering passenger vehicle and airplane geometries. Transport. Res. Record 2020, 2674(10), 438–447. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Wang, H. Retroreflectivity-based service life and life-cycle cost analysis of airfield pavement markings. Transport. Res. Record 2024, 03611981241255368. [CrossRef]

- Burns, D.; Hedblom, T.; Miller, T. Modern pavement marking systems: relationship between optics and nighttime visibility. Transport. Res. Record 2007, 2056, 43–51. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.Y.; Lee, J.I.; Chung, W.J.; Choi, Y.G. Correlations between refractive index and retroreflectance of glass beads for use in road-marking applications under wet conditions. Curr. Optics Photonics 2019, 3(5), 423-428. [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.E.; Köck, B.; Pashkevich, A. Fasching, A. Skid resistance of road markings: literature review and field test results. Roads Bridges 2023, 22, 141–164. [CrossRef]

- Siwińska-Stefańska, K.; Krysztafkiewicz, A.; Jesionowski, T. Effect of inorganic oxides treatment on the titanium dioxide surface properties. Physicochem. Problems Mineral Process. 2008, 42, 141-–152.

- Konradsen, F.; Hansen, K.S.H.; Ghose, A.; Pizzol, M. Same product, different score: how methodological differences affect EPD results. Int. J. Life Cycle Assessm. 2024, 29(2), 291–307. [CrossRef]

- Babić, D.; Ščukanec, A.; Babić, D.; Fiolić, M. Model for predicting road markings service life. Baltic J. Road Bridge Eng. 2019, 14(3), 341–359. [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, A.; Shoghli, O. Predictive analytics for roadway maintenance: a review of current models, challenges, and opportunities. Civil Eng. J. 2020, 6, 602–625. [CrossRef]

- Idris, I.I.; Mousa, M.; Hassan, M. Modeling retroreflectivity degradation of pavement markings across the US with advanced machine learning algorithms. J. Infrastr. Preserv. Resilience 2024, 5, 3. [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.E.; Pashkevich, A. Green Public Procurement criteria for road marking materials from insiders’ perspective. J. Cleaner Prod. 2021, 298, 126521. [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, T.E.; Pashkevich, A.; Żakowska, L. Contribution of solvents from road marking paints to tropospheric ozone formation. Budownictwo Architektura 2016, 15(1), 7–18. [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, A.; Ščukanec, A.; Babić, D. Impact of winter maintenance on retroreflection of road markings. In: Proceedings of International Scientific Conference “Perspectives on Croatian 3PL Industry in Acquiring International Cargo Flows”, Zagreb, Croatia, 12 April 2016, pp. 119–127.

- Fiolić, M.; Habuzin, I.; Dijanić, H.; Sokol, H. The influence of drying of the road marking materials on traffic during the application of markings. In: Proceedings of ZIRP-LST Conference, Opatija, Croatia, 1–2 June 2017, pp. 109–118.

- Vega, G.C.; Gross, A.; Birkved, M. The impacts of plastic products on air pollution-a simulation study for advanced life cycle inventories of plastics covering secondary microplastic production. Sust. Prod. Consumpt. 2021, 28, 848–865. [CrossRef]

- Saling, P.; Gyuzeleva, L.; Wittstock, K.; Wessolowski, V.; Griesshammer, R. Life cycle impact assessment of microplastics as one component of marine plastic debris. Int. J. Life Cycle Assessm. 2020, 25, 2008–2026. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A.E.; Herlaar, S.; Cohen, Q.M.; Quik, J.T.K.; Golkaram, M.; Urbanus, J.H., van Emmerik, T.H.M.; Huijbregts, M.A.J. Microplastic aquatic impacts included in life cycle assessment. Resources Conserv. Recycling 2024, 209, 107787. [CrossRef]

- Tsyganov, A.R.; Machemehl, R.B.; Warrenchuk, N.M., Wang, Y. Before-after comparison of edgeline effects on rural two-lane highways. Report No. FHWA/TX-07/0-5090-2. Texas Department of Transportation, Research and Technology Implementation Office: Austin, TX, USA, 2006.

- Avelar, R.E.; Carlson, P. J. Link between pavement marking retroreflectivity and night crashes on Michigan two-lane highways. Transport. Res. Record 2014, 2404, 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, P.J.; Avelar, R.E.; Park, E.S.; Kang, D.H. Nighttime safety and pavement marking retroreflectivity on two-lane highways: revisited with North Carolina data. In: Proceedings of Transportation Research Board 94th Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 January 2015, paper 15-5753.

- Faith-Ell, C.; Balfors, B.; Folkeson, L.The application of environmental requirements in Swedish road maintenance contracts. J. Cleaner Prod. 2006, 14(2), 163–171. [CrossRef]

- Parikka-Alhola, K.; Nissinen, A.. Enhancing green practice in public road construction procurement. In: Proceedings of 3rd International Public Procurement Conference; Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 28–30 August 2008, pp. 655–666.

- Anthonissen, J.; Van Troyen, D.; Braet, J. Using carbon dioxide emissions as a criterion to award road construction projects: a pilot case in Flanders. J. Cleaner Prod. 2015, 102, 96–102. [CrossRef]

- Laurinavičius, A.; Skerys, K.; Jasiūnienė, V.; Pakalnis, A.; Starevičius, M. Analysis and evaluation of the effect of studded tyres on road pavement and environment (I). Baltic J. Road Bridge Eng. 2009, 4(3), 115–122. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.; Janhäll, S.; Gustafsson, M.; Erlingsson, S. Calibration of the Swedish studded tyre abrasion wear prediction model with implication for the NORTRIP road dust emission model. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2021, 22(4), 432–446. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, F.; Zhang, H. Active luminous road markings: a comprehensive review of technologies, materials, and challenges. Constr. Building Mat. 2023, 363, 129811. [CrossRef]

| Layer | Coating layer | Retroreflective layer (drop-on material) |

|---|---|---|

| Functions | Adhesion to road surface. Colour contrasting with the roadway. Surface for retroreflection. Adhesion surface for retroreflective layer. |

Retroreflection. Protection of the coating layer from abrasion. Skid resistance. |

| Selected materials | Paint (solventborne, waterborne). Cold plastic. Thermoplastic. Plural-component (epoxy, urea, urethane, etc.; solventborne or solvent-less). Tapes. |

Glass beads (GBs). GBs mixed with anti-skid particles (ASPs), sometimes called anti-skid agglomerates. ASPs alone (special purposes only). Crystalline elements in lieu of GBs. |

| Application methods | Thin layer: spray. Thick layer: extrusion, screed, roller. Tapes: glue with pressure-sensitive adhesive. |

Drop-on during application (in tapes and some pre-formed materials – during manufacturing). |

| Layer thickness, applied quantity (thin layer) | Paints: wet film 0.3–0.6 mm (up to 0.9 mm) / 0.5–1.5 kg/m², resulting in dry film approximately 0.2–0.4 mm (up to 0.6 mm). Solvent-less materials: 0.2–1.0 mm (up to 1.5 mm) / 0.2–2.2 kg/m². Only flat lines. |

Drop-on application 0.3–0.5 kg/m². Layer approximately 0.05−0.5 mm thick (GBs diameters 0.1−1.0 mm). |

| Layer thickness, applied quantity (thick layer) | Wet film 1.0–6.0 mm / 1.5–7.0 kg/m², resulting in dry film approximately 1.0–6.0 mm; flat lines or structured. | Drop-on application 0.3–0.5 kg/m². Layer approximately 0.1−1.0 mm (GBs diameters 0.2−2.0 mm). |

| Abrasion resistance | Very low or low (except for cold plastic and tapes: very high). | High or very high. |

| Material | Typical resin (binder) | Description and comments |

|---|---|---|

| Solventborne paints | Acrylic, alkyd, styrenic (chlorinated rubber is mostly obsolete). Content 10–15%. | Commonly utilised worldwide. Because of relatively short service life mostly suitable for areas with minimal encroachment of vehicles. Can be utilised for renewal of thick layer RMs. Some formulations, nowadays mostly obsolete, contained GBs intermixed with the paint. Dry through evaporation of organic solvents (typical contents 22–28%), thus contributing to tropospheric ozone formation [40]. Applied at wet film builds 0.3–0.5 mm (thicker films not possible due to shrinking during drying). |

| Waterborne paints | Acrylic, styrenic, vinyl, acetoacetate, polyol, etc. Content 15–25%. | Usage varies between regions. Designed for marking of areas of low to moderate exposure to vehicular traffic, can be utilised for renewal of thick layer RMs. Usually more durable than solventborne paints; with some binders affording really high durability [21]. Instead of simple drying, can cure through solvent evaporation combined with an acid-base reaction; quick drying and curing can be achieved with some binders. Because binder is delivered as a dispersion, the use of a coalescent is necessary [41]. Emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) minimised to usually <2%; water content typically 15–20%. Disadvantage of waterborne paints is the need to achieve washout resistance after drying; this period may be quite long in case of cool and humid weather conditions. Applied at wet film builds 0.2–0.5 mm (thicker films not possible due to shrinking during drying), but special high-performance paints can be applied at up to 0.9 mm. |

| Thermoplastic (for thick layer application) | Hydrocarbon and/or esterified rosin. Content 12–17%. | Most commonly used thick-layer material worldwide, known since 1940s, easy to formulate and apply. Solvent-less product, delivered in powdery form, applied from a hot melt (about 200 °C), ready for use immediately upon cooling. Always contains ‘premix’ GBs and coarse fillers. Thermoplastics are often delivered in pre-formed shapes, which are also applied through heat. Thermoplastics are the only RMs designed for slow wear-off (the ‘premix’ GBs are thus exposed to continuously deliver RL; this feature is increasing road safety, albeit at the expense of particulate emissions). The possible use of modified rosin esters as binders (non-polymeric material) brings additional considerations related to the environmental impacts [42,43]. Applied as flat lines (rarely structures) through extrusion or using a screed box in layers 3 mm (range 1–5 mm possible) thick; upon the decrease in properties renewed with another layer of sprayed or extruded thermoplastic. Sometimes it is possible to renew through washing (to augment the exposure of the ‘premix’ GBs). All applications on new road surface demand the use of a primer. Thermoplastic formulations must be modified for the use in a particular climatic conditions. |

| Thermoplastic (sprayed) | Hydrocarbon and/or esterified rosin. Content 15–25%. | Chemically the same as thermoplastic, but typically devoid of the ‘premix’ GBs and ASPs. Applied by spraying at layers 0.3–1.5 mm (layers >1.0 mm with some coarse fillers). |

| Cold plastic (for thick layer application) | Acrylic. Content 20–30%. | Modern solvent-less hard material that furnishes exceptional durability, especially at the stage of physical service life. Delivered as acrylic oligomers and monomers, which polymerise on road surface upon mixing with a peroxide initiator. Always contains intermixed coarse fillers (often also ‘premix’ GBs) that enhance resistance to abrasion. Upon the loss of functional properties, renewed with thin layer applications of paint or sprayed cold plastic. Applied through extrusion (at small surfaces, also by manual rolling or spreading), as flat lines or structures; film builds up to 6.0 mm thick are possible. |

| Cold plastic (sprayed) | Acrylic. Content 35–45%. | Modern emerging solvent-less material furnishing high durability. Delivered as acrylic oligomers and monomers, which polymerise on road surface upon mixing with a peroxide initiator. Can be applied at wet film builds 0.2–1.0 mm (does not shrink upon cure). |

| Tapes | Urethane (rarely other). Content 30–40%. | Advanced solvent-less RMs glued to road surface with a pressure-sensitive adhesive; can also be applied to hot bitumen. Furnish very long service life and exceptional properties (particularly tapes designed for Type II performance). Prohibitively high purchase and installation cost. The only RMs not designed for renewal, but for removal and reapplication upon the loss of properties. |

| Material | RI | Description | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Standard’ GBs | 1.5 | Manufactured in vertical furnaces from ground recycled float glass (glass granulate). Surface defects from production process may be possible. | Most typical GB, currently least expensive, widely available. Diameters used in RM: 0.2–0.8 mm (possible range 0.06–1.0 mm). Permits for obtention of RL <350 mcd/m²/lx and, due to low RI, RW <60 mcd/m²/lx in white paint. |

| ‘Large’ GBs | 1.5 | Manufactured from virgin glass melts. High roundness and surface quality. | Produced for RMs in diameters 0.5–2.0 mm (for other industrial applications, the same type of GBs are made also in smaller diameters). Larger dimensions than in ‘Standard’ GB permit for somewhat improved RW. RL <400 mcd/m²/lx and RW <100 mcd/m²/lx can be obtained in white paint. |

| ‘Premium’ GBs | 1.6–1.7 | Silica-titanate GBs manufactured from virgin raw materials using proprietary process furnishing high roundness and good scratch resistance. | The mildly increased RI provide disproportionally high RL, reaching 1000 mcd/m²/lx and RW <200 mcd/m²/lx in white paint. Purchase cost much higher than for ‘Standard’ or ‘Large’ GBs; recently commercialised and available worldwide in diameters 0.3–1.0 mm. |

| ‘High index’ GBs | 1.9 | Silica-barium-titanate GBs made from virgin raw materials with superior roundness and surface quality. | High RI allows for obtention of RL <1800 mcd/m²/lx and RW <400 mcd/m²/lx in white paint. Nonetheless, high cost and low scratch resistance limit their use to some tapes and airport markings [48,49]. Expensive due to the need of using large quantity of TiO₂. Diameters 0.3–1.0 mm are readily available. |

| ‘Crystalline elements’ | 2.1–2.4 | Barium-titanate or lanthanum-titanate non-glassy spherical crystalline materials. | The high RI leads to diminished RL (<300 mcd/m²/lx), but outstanding RW (>300 mcd/m²/lx) in white RMs. Used mostly in high-end tapes designed for Type II performance [50,51]. Prohibitively expensive. |

| Material | Description | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Cristobalite sand ASPs | Commonly utilised opaque ASP, >95% SiO₂, contains crystalline silica. | Inexpensive and readily available. Moderate hardness (Mohs scale 6–7). |

| Glass granulate ASPs | The raw material fed to the vertical ovens to prepare the ‘Standard’ GBs can also be used as transparent ASP to enhance skid resistance. | Inexpensive and highly efficient initially. Relatively soft (Mohs scale 5–6) may undergo polishing, which results in quickly diminishing performance [52]. |

| Corundum ASP | Highly effective transparent ASP, >95% Al₂O₃. | Very hard (Mohs scale 9), but costly ASP; usually used in combination with sand. |

| Coating layer material | Solventborne paint, aromatic-free | Solventborne paint, toluene-based | Waterborne paint, quick-set | Waterborne paint, high-performance | Sprayed cold plastic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material code | SAF | SAR | WQD | WHP | KSP |

| Binder (acrylic) | 10.00% | 10.00% | 15.45% | 17.15% | 39.77% |

| TiO₂ (a) | 4.00% | 6.80% | 4.75% | 7.00% | 8.00% |

| CaCO₃ | 58.35% | 55.70% | 51.40% | 50.95% | 49.40% |

| Coalescent (b) | – | – | 3.55% | 1.75% | – |

| VOC emissions | 25.70% | 24.70% (c) | 0.40% (d) | 0.40% (d) | 1.00% (e) |

| Water | – | – | 23.04% | 21.69% | – |

| Other additives | 1.95% | 2.80% | 1.41% | 1.06% | 2.58% |

| Peroxide initiator (f) | – | – | – | – | 1.00% |

| Retroreflective layer material | ‘Standard’ GBs | ‘Mixed’ GBs | ‘Premium’ GBs |

| Material code | S | M | P |

| SiO₂ | 58.00% | 39.25% | 28.00% |

| Na₂O | 10.00% | 3.75% | 0.00% |

| Al₂O₃ | 0.00% | 6.25% | 10.00% |

| MgO | 3.20% | 7.45% | 10.00% |

| CaO | 8.00% | 15.50% | 20.00% |

| TiO₂ | 0.00% | 6.25% | 10.00% |

| Other | 0.79% | 1.54% | 1.99% |

| Anti-skid particle (sand) | 20.00% | 20.00% | 20.00% |

| Organosilane coating | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.01% |

| Material type | Coating layer materials | Retroreflective layer materials | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact category (a) | SAF | SAR | WQD | WHP | KSP (b) | S | M | P |

| GWP (total) | 2.68 | 2.24 | 2.06 | 2.11 | 2.59 | 0.78 | 1.04 | 1.20 |

| GWP (fossil) | 2.66 | 2.22 | 2.05 | 2.12 | 2.58 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.88 |

| GWP (biogenic) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| GWP (luluc) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| AP | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| EP (terrestrial) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| ADPF | 42.98 | 38.83 | 30.74 | 28.86 | 41.36 | 13.00 | 12.38 | 12.01 |

| WDP | 1.97 | 1.49 | 1.42 | 1.49 | 2.55 | 0.04 | 0.74 | 1.17 |

| PERT | 2.14 | 1.61 | 2.66 | 2.87 | 2.53 | 0.54 | 4.62 | 7.07 |

| PENRT | 46.24 | 41.59 | 32.85 | 30.43 | 44.34 | 14.38 | 9.18 | 6.06 |

| FW | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| NHWD | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.48 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| IR | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| ETP | 39.62 | 24.46 | 40.68 | 44.70 | 41.02 | 4.98 | 19.84 | 28.77 |

| SQP | 8.31 | 6.19 | 10.43 | 11.78 | 10.61 | 1.68 | 4.74 | 6.58 |

| Road marking system code (a) | Functional service life (b) | Number of applications needed (c) | GWP [kg CO₂ eq.] per application | Total GWP [kg CO₂ eq.] per series of applications (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAF + S | 0.6 | 32 | 3.2 | 107.0 |

| SAR + S | 2.5 | 8 | 3.0 | 26.8 |

| SAR + M | 3.9 | 6 | 3.1 | 21.6 |

| WQD + S | 1.6 | 13 | 2.9 | 40.2 |

| WQD + M | 3.6 | 6 | 3.0 | 20.8 |

| WHP + S | 3.6 | 6 | 2.9 | 20.3 |

| WHP + M | 5.7 | 4 | 3.0 | 15.0 |

| WHP + P | 4.5 | 5 | 3.1 | 18.4 |

| KSP + S | 1.9 | 11 | 2.9 | 35.2 |

| KSP + P | 5.5 | 4 | 3.1 | 15.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).