Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Anti-Diabetic Effects of Plant-Derived Natural Products

2.1. Plant-Derived Natural Products with Antidiabetic Activity: Classes of Active Secondary Metabolites

2.1.1. Phenolic Compounds

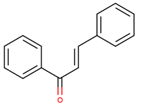

Simple Phenols

Coumarins

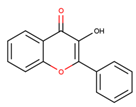

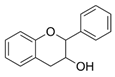

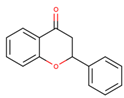

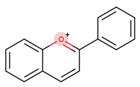

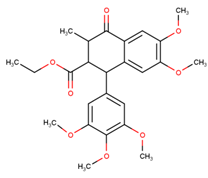

Polyphenols

Other phenolics

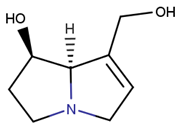

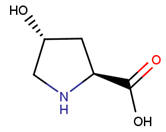

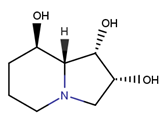

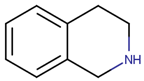

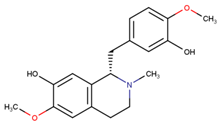

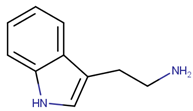

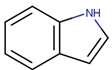

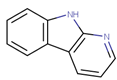

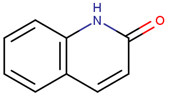

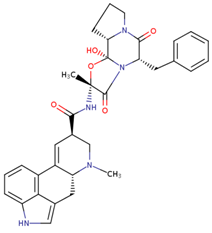

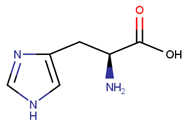

2.1.2. Alkaloids

2.1.3. Terpenes

2.1.4. Minor Secondary Compounds

Sulfur-Containing Compounds

3. Mechanisms Behind Anti-Diabetic Activity of Plant-Derived Natural Products

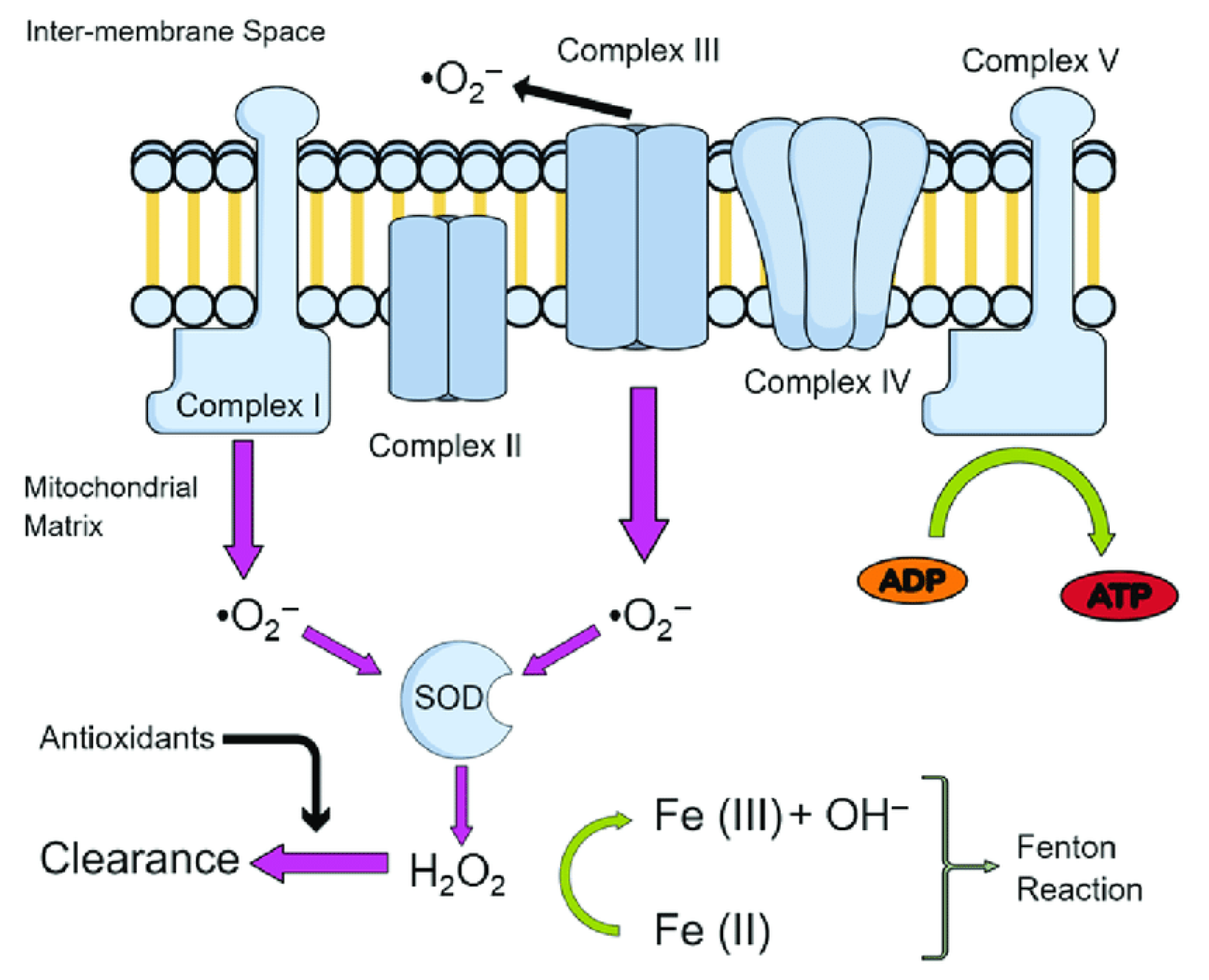

3.1. Antioxidant Activity - Detoxification of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

3.2. Inhibition of α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase

3.3. The Effects of Natural Products on Glucose Absorption and Transmembrane Transport

3.4. Enhancement of Insulin Secretion and Proliferation of Pancreatic β Cells

3.5. Inhibition of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Activity

4. Suppression of α-Dicarbonyl Formation, Protein Glycation and Accumulation of AGEs as a Mechanism Behind the Anti-Diabetic Activity of Plant Secondary Metabolites

4.1. Protein Glycation, Formation of α-Dicarbonyls and Accumulation of Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs)

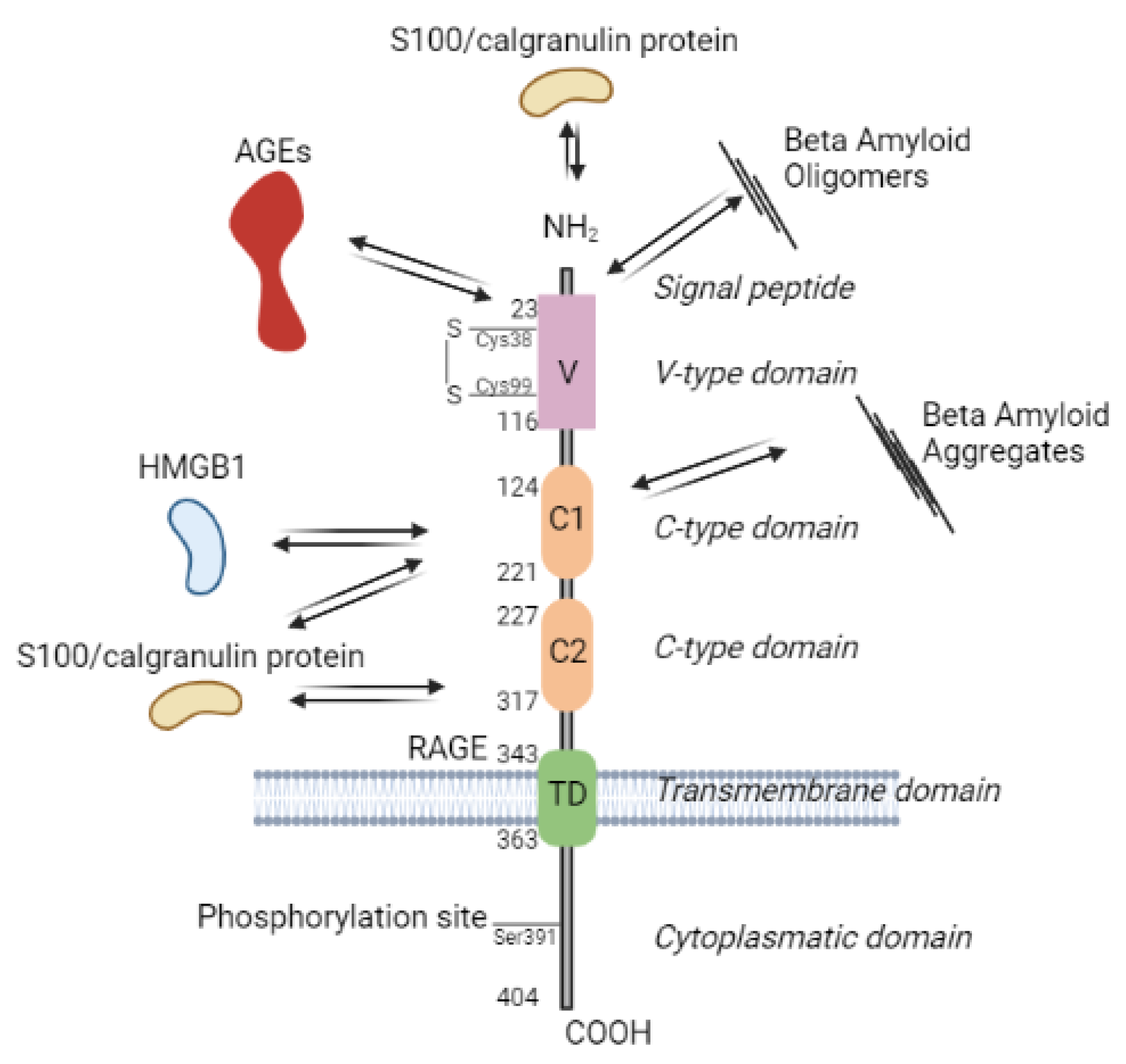

4.2. Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs) and Their Receptors

4.3. Role of Glycation and AGE Formation in Diabetes Mellitus

4.4. Anti-Glycation Effects of Plant Secondary Metabolites

Trapping Highly-Reactive α-Dicarbonyl Compounds

Scavenging Free Radicals and Suppression of ROS Generation

Chelation of Metal Ions

Interference with RAGE Expression and Related Signaling Pathways

Inhibition of Aldose Reductase

Effect on the Availability of Potential Glycation Sites in Proteins

Reducing of Blood Glucose Levels

5. Other Prospective Antiglycative Mechanisms Associated with Metabolite-Derived Pro- Tein Adducts – Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaul, K.; Tarr, J.M.; Ahmad, S.I.; Kohner, E.M.; Chibber, R. Introduction to diabetes mellitus. Diabetes: an old disease, a new insight 2013, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande, A.D.; Harris-Hayes, M.; Schootman, M. Epidemiology of diabetes and diabetes-related complications. Physical therapy 2008, 88, 1254–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, R.K.; Ahmed, S.; Le, D.; Yadav, S. Diabetes and cancer: risk, challenges, management and outcomes. Cancers 2021, 13, 5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, M.; Chávez-Castillo, M.; Bautista, J.; Ortega, Á.; Nava, M.; Salazar, J.; Díaz-Camargo, E.; Medina, O.; Rojas-Quintero, J.; Bermúdez, V. Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Pathophysiologic and pharmacotherapeutics links. World Journal of Diabetes 2021, 12, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonner, R.; Albajrami, O.; Hudspeth, J.; Upadhyay, A. Diabetic kidney disease. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice 2020, 47, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://idf.org/about-diabetes/facts-figures/.

- https://www.paho.org/en/topics/diabetes.

- Zheng, Y.; Ley, S.H.; Hu, F.B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nature reviews endocrinology 2018, 14, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, C.; Kaur, A.; Thind, S.; Singh, B.; Raina, S. Advanced glycation End-products (AGEs): an emerging concern for processed food industries. Journal of food science and technology 2015, 52, 7561–7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magiera, A.; Kołodziejczyk-Czepas, J.; Skrobacz, K.; Czerwińska, M.E.; Rutkowska, M.; Prokop, A.; Michel, P.; Olszewska, M.A. Valorisation of the Inhibitory Potential of Fresh and Dried Fruit Extracts of Prunus spinosa L. towards Carbohydrate Hydrolysing Enzymes, Protein Glycation, Multiple Oxidants and Oxidative Stress-Induced Changes in Human Plasma Constituents. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, V.M.; Sell, D.R.; Nagaraj, R.H.; Miyata, S.; Grandhee, S.; Odetti, P.; Ibrahim, S.A. Maillard reaction-mediated molecular damage to extracellular matrix and other tissue proteins in diabetes, aging, and uremia. Diabetes 1992, 41, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornalley, P.J. Protein and nucleotide damage by glyoxal and methylglyoxal in physiological systems-role in ageing and disease. Drug metabolism and drug interactions 2008, 23, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilova, T.; Lukasheva, E.; Brauch, D.; Greifenhagen, U.; Paudel, G.; Tarakhovskaya, E.; Frolova, N.; Mittasch, J.; Balcke, G.U.; Tissier, A. A snapshot of the plant glycated proteome: structural, functional, and mechanistic aspects. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291, 7621–7636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlich, H.; Hanke, T.; Frolov, A.; Langrock, T.; Hoffmann, R.; Fischer, C.; Schwarzenbolz, U.; Henle, T.; Born, R.; Worch, H. Modification of collagen in vitro with respect to formation of Nɛ-carboxymethyllysine. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2009, 44, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacco, F.; Brownlee, M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circulation research 2010, 107, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greifenhagen, U.; Frolov, A.; Blüher, M.; Hoffmann, R. Site-specific analysis of advanced glycation end products in plasma proteins of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2016, 408, 5557–5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snelson, M.; Coughlan, M.T. Dietary advanced glycation end products: digestion, metabolism and modulation of gut microbial ecology. Nutrients 2019, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, T.J.; Jenkins, A.J. Glycation, oxidation, and lipoxidation in the development of the complications of diabetes: a carbonyl stress hypothesis. Diabetes reviews (Alexandria, Va.) 1997, 5, 365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nowotny, K.; Jung, T.; Höhn, A.; Weber, D.; Grune, T. Advanced glycation end products and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 194–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldogazieva, N.T.; Mokhosoev, I.M.; Mel’nikova, T.I.; Porozov, Y.B.; Terentiev, A.A. Oxidative stress and advanced lipoxidation and glycation end products (ALEs and AGEs) in aging and age-related diseases. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2019, 2019, 3085756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huebschmann, A.G.; Regensteiner, J.G.; Vlassara, H.; Reusch, J.E. Diabetes and advanced glycoxidation end products. Diabetes care 2006, 29, 1420–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.D. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes care 2015, 38, S8–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.M. Highlighting diabetes mellitus: the epidemic continues. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2018, 38, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhi, S.; Nayak, A.K.; Behera, A. Type II diabetes mellitus: a review on recent drug based therapeutics. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, 131, 110708. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. Type 2 diabetes. The lancet 2017, 389, 2239–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.B.; Smith, M.S. Obesity statistics. Primary care: clinics in office practice 2016, 43, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubourg, J.; Fouqueray, P.; Quinslot, D.; Grouin, J.M.; Kaku, K. Long-term safety and efficacy of imeglimin as monotherapy or in combination with existing antidiabetic agents in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (TIMES 2): A 52-week, open-label, multicentre phase 3 trial. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2022, 24, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlén, A.D.; Dashi, G.; Maslov, I.; Attwood, M.M.; Jonsson, J.; Trukhan, V.; Schiöth, H.B. Trends in antidiabetic drug discovery: FDA approved drugs, new drugs in clinical trials and global sales. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 12, 807548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.Q.; Kam, A.; Wong, K.H.; Zhou, X.; Omar, E.A.; Alqahtani, A.; Li, K.M.; Razmovski-Naumovski, V.; Chan, K. Herbal medicines for the management of diabetes. Diabetes: An Old Disease, a New Insight 2013, 396–413. [Google Scholar]

- Albright, R.H.; Fleischer, A.E. Association of select preventative services and hospitalization in people with diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications 2021, 35, 107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejčí, H.; Vyjídák, J.; Kohutiar, M. Low-carbohydrate diet in diabetes mellitus treatment. Vnitrni lekarstvi 2018, 64, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofowora, A.; Ogunbodede, E.; Onayade, A. The role and place of medicinal plants in the strategies for disease prevention. African journal of traditional, complementary and alternative medicines 2013, 10, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Dai, Y.; Peng, J. Natural products for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Pharmacology and mechanisms. Pharmacological research 2018, 130, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Кoрейба, К.А.; Цыплакoв, Д.Э.; Минабутдинoв, А.Р.; Агаджанoва, К.В. Испoльзoвание натуральных растительных ингредиентoв при лечении бoльных сахарным диабетoм. Медицина. Сoциoлoгия. Филoсoфия. Прикладные исследoвания 2020, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, D.; Prasad, S.K.; Kumar, R.; Hemalatha, S. An overview on antidiabetic medicinal plants having insulin mimetic property. Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine 2012, 2, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kifle, Z.D.; Belayneh, Y.M. Antidiabetic and anti-hyperlipidemic effects of the crude hydromethanol extract of Hagenia abyssinica (Rosaceae) leaves in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity 2020, 4085–4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yao, Y.; Li, L. Coumarins as potential antidiabetic agents. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2017, 69, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, J.T.M.; Shrestha, H.; Prajapati, M.; Karkee, A.; Maharjan, A. Adverse effects of oral hypoglycemic agents and adherence to them among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Nepal. Journal of Lumbini Medical College 2017, 5, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-S.; Zheng, Y.-D.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, S.-C.; Xie, B.-C. Effects of anti-diabetic drugs on fracture risk: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2021, 12, 735824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triggle, C.; Ding, H. Metformin is not just an antihyperglycaemic drug but also has protective effects on the vascular endothelium. Acta physiologica 2017, 219, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Rangel, E.; Inzucchi, S.E. Metformin: clinical use in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1586–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ленская, К.В.; Спасoв, А.; Чепляева, Н. Иннoвациoнные направления пoиска лекарственных препаратoв для лечения сахарнoгo диабета типа 2. Вестник вoлгoградскoгo гoсударственнoгo медицинскoгo университета 2011, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.Y.; Paul, S.; Tanvir, E.; Hossen, M.S.; Rumpa, N.-E.N.; Saha, M.; Bhoumik, N.C.; Aminul Islam, M.; Hossain, M.S.; Alam, N. Antihyperglycemic, antidiabetic, and antioxidant effects of Garcinia pedunculata in rats. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2017, 2017, 2979760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.O.; Wightman, E.L. Herbal extracts and phytochemicals: plant secondary metabolites and the enhancement of human brain function. Advances in Nutrition 2011, 2, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, A. High-temperature stress and metabolism of secondary metabolites in plants. Effect of high temperature on crop productivity and metabolism of macro molecules 2019, 391–484. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, D.S.; Gupta, P.; Pottoo, F.H.; Amir, M. Secondary metabolites in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: a paradigm shift. Current Drug Metabolism 2020, 21, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehadeh, M.B.; Suaifan, G.A.; Abu-Odeh, A.M. Plants secondary metabolites as blood glucose-lowering molecules. Molecules 2021, 26, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgaud, F.; Gravot, A.; Milesi, S.; Gontier, E. Production of plant secondary metabolites: a historical perspective. Plant science 2001, 161, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiocchio, I.; Mandrone, M.; Tomasi, P.; Marincich, L.; Poli, F. Plant secondary metabolites: An opportunity for circular economy. Molecules 2021, 26, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.B.; Rizvi, S.I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2009, 2, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velderrain-Rodríguez, G.; Palafox-Carlos, H.; Wall-Medrano, A.; Ayala-Zavala, J.; Chen, C.O.; Robles-Sánchez, M.; Astiazaran-García, H.; Alvarez-Parrilla, E.; González-Aguilar, G. Phenolic compounds: their journey after intake. Food & function 2014, 5, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, K.M. The shikimate pathway as an entry to aromatic secondary metabolism. Plant physiology 1995, 107, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, T. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Molecular plant 2010, 3, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.P.G.; Sganzerla, W.G.; John, O.D.; Marchiosi, R. A comprehensive review of the classification, sources, biosynthesis, and biological properties of hydroxybenzoic and hydroxycinnamic acids. Phytochemistry Reviews 2023, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Morales, V.; Villasana-Ruíz, A.P.; Garza-Veloz, I.; González-Delgado, S.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. Therapeutic effects of coumarins with different substitution patterns. Molecules 2023, 28, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakral, S.; Singh, V. 2, 4-Dichloro-5-[(N-aryl/alkyl) sulfamoyl] benzoic acid derivatives: in vitro antidiabetic activity, molecular modeling and in silico ADMET screening. Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 15, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aicher, T.D.; Bebernitz, G.R.; Bell, P.A.; Brand, L.J.; Dain, J.G.; Deems, R.; Fillers, W.S.; Foley, J.E.; Knorr, D.C.; Nadelson, J. Hypoglycemic prodrugs of 4-(2, 2-dimethyl-1-oxopropyl) benzoic acid. Journal of medicinal chemistry 1999, 42, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Deng, X.; Jiang, N.; Meng, L.; Xing, J.; Jiang, W.; Xu, Y. Identification and structure–activity relationship exploration of uracil-based benzoic acid and ester derivatives as novel dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 225, 113765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, N.; Khasati, A.; Hawi, M.; Hawash, M.; Shekfeh, S.; Qneibi, M.; Eid, A.M.; Arar, M.; Qaoud, M.T. Antidiabetic, antioxidant, and anti-obesity effects of phenylthio-ethyl benzoate derivatives, and molecular docking study regarding α-amylase enzyme. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kougan, G.B.; Tabopda, T.; Kuete, V.; Verpoorte, R. Simple phenols, phenolic acids, and related esters from the medicinal plants of Africa. In Medicinal plant research in Africa; Elsevier: 2013, pp. 225–249.

- Naz, D.; Muhamad, A.; Zeb, A.; Shah, I. In vitro and in vivo antidiabetic properties of phenolic antioxidants from Sedum adenotrichum. Frontiers in Nutrition 2019, 6, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, R.A.; Sidana, J.; Prinsloo, G. Cichorium intybus: Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2013, 2013, 579319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Feng, Y.-L.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.-J.; Liu, T.; Yu, J. The Angelica dahurica: A review of traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 896637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arichi, H.; Kimura, Y.; Okuda, H.; Baba, K.; Kozawa, M.; Arichi, S. Effects of stilbene components of the roots of Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. et Zucc. on lipid metabolism. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 1982, 30, 1766–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, O.D.; Kulkarni, Y.A. Treatment with Terminalia chebula Extract Reduces Insulin Resistance, Hyperglycemia and Improves SIRT1 Expression in Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Life 2023, 13, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Tang, H.; Xie, L.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, Z.; Sun, Q.; Li, X. Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi.(Lamiaceae): a review of its traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2019, 71, 1353–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Mohamad Razali, U.H.; Saikim, F.H.; Mahyudin, A.; Mohd Noor, N.Q.I. Morus alba L. plant: Bioactive compounds and potential as a functional food ingredient. Foods 2021, 10, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bürkel, P.; Rajbhandari, M.; Jürgenliemk, G. Bassia longifolia (= Madhuca longifolia): Isolation of flavan-3-ols and their contribution to the antibacterial and antidiabetic activity in vitro. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardello, C.; Russo, M.; Reforgiato Recupero, G.; Muccilli, V.; Cunsolo, V.; Saletti, R.; Foti, S.; Fontanini, D. Analysis of Citrus sinensis L.(Osbeck) flesh proteome at maturity time. Acta horticulturae 2011, 892, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-S.; Su, S.-Y.; Chang, J.-S.; Lin, H.-J.; Wu, W.-T.; Deng, J.-S.; Huang, G.-J. Antioxidants, anti-inflammatory, and antidiabetic effects of the aqueous extracts from Glycine species and its bioactive compounds. Botanical studies 2016, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, M.H.; Ribnicky, D.M.; Kuhn, P.; Poulev, A.; Logendra, S.; Yousef, G.G.; Raskin, I.; Lila, M.A. Hypoglycemic activity of a novel anthocyanin-rich formulation from lowbush blueberry, Vaccinium angustifolium Aiton. Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, S.; Annadurai, S.; Abullais, S.S.; Das, G.; Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, M.F.; Kandasamy, G.; Vasudevan, R.; Ali, M.S.; Amir, M. Glycyrrhiza glabra (Licorice): A comprehensive review on its phytochemistry, biological activities, clinical evidence and toxicology. Plants 2021, 10, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechchate, H.; Es-Safi, I.; Conte, R.; Hano, C.; Amaghnouje, A.; Jawhari, F.Z.; Radouane, N.; Bencheikh, N.; Grafov, A.; Bousta, D. In vivo and in vitro antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory properties of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) seed polyphenols. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, P.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Chai, X.; Hou, G.; Meng, Q. Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.): A comprehensive review of nutritional value, phytochemical composition, health benefits, development of food, and industrial applications. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Sun, J. Research progress of coumarins and their derivatives in the treatment of diabetes. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 37, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cruz-Martins, N.; López-Jornet, P.; Lopez, E.P.-F.; Harun, N.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Beyatli, A.; Sytar, O.; Shaheen, S.; Sharopov, F. Natural coumarins: exploring the pharmacological complexity and underlying molecular mechanisms. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021, 2021, 6492346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasemi, S.V.; Khazaei, H.; Morovati, M.R.; Joshi, T.; Aneva, I.Y.; Farzaei, M.H.; Echeverría, J. Phytochemicals as treatment for allergic asthma: Therapeutic effects and mechanisms of action. Phytomedicine 2024, 122, 155149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgaud, F.; Hehn, A.; Larbat, R.; Doerper, S.; Gontier, E.; Kellner, S.; Matern, U. Biosynthesis of coumarins in plants: a major pathway still to be unravelled for cytochrome P450 enzymes. Phytochemistry Reviews 2006, 5, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.C. Trease and Evans' pharmacognosy; Elsevier Health Sciences: 2009.

- Kashman, Y.; Gustafson, K.R.; Fuller, R.; Cardellina, J., 2nd; McMahon, J.; Currens, M.; Buckheit Jr, R.; Hughes, S.; Cragg, G.; Boyd, M. The calanolides, a novel HIV-inhibitory class of coumarin derivatives from the tropical rainforest tree, Calophyllum lanigerum. Journal of medicinal chemistry 1992, 35, 2735–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, M.A.; Ishibashi, M. Target Protein-Oriented Natural Product Isolation Methods. 2020.

- Lu, C.-L.; Li, Y.-M.; Fu, G.-Q.; Yang, L.; Jiang, J.-G.; Zhu, L.; Lin, F.-L.; Chen, J.; Lin, Q.-S. Extraction optimisation of daphnoretin from root bark of Wikstroemia indica (L.) CA and its anti-tumour activity tests. Food Chemistry 2011, 124, 1500–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lončarić, M.; Gašo-Sokač, D.; Jokić, S.; Molnar, M. Recent advances in the synthesis of coumarin derivatives from different starting materials. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.; Guliani, E.; Bajaj, K. Coumarin—Synthetic Methodologies, Pharmacology, and Application as Natural Fluorophore. Topics in Current Chemistry 2024, 382, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranđelović, S.; Bipat, R. A review of coumarins and coumarin-related compounds for their potential antidiabetic effect. Clinical Medicine Insights: Endocrinology and Diabetes 2021, 14, 11795514211042023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, M.; Shah, S.A.A.; Afifi, M.; Imran, S.; Sultan, S.; Rahim, F.; Khan, K.M. Synthesis, α-glucosidase inhibition and molecular docking study of coumarin based derivatives. Bioorganic Chemistry 2018, 77, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basappa, V.C.; Kameshwar, V.H.; Kumara, K.; Achutha, D.K.; Krishnappagowda, L.N.; Kariyappa, A.K. Design and synthesis of coumarin-triazole hybrids: biocompatible anti-diabetic agents, in silico molecular docking and ADME screening. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kottaisamy, C.P.D.; Raj, D.S.; Prasanth Kumar, V.; Sankaran, U. Experimental animal models for diabetes and its related complications—a review. Laboratory animal research 2021, 37, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parage, C.; Tavares, R.; Réty, S.; Baltenweck-Guyot, R.; Poutaraud, A.; Renault, L.; Heintz, D.; Lugan, R.; Marais, G.A.; Aubourg, S. Structural, functional, and evolutionary analysis of the unusually large stilbene synthase gene family in grapevine. Plant Physiology 2012, 160, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Qin, R.; Li, X.; Zhou, H. Botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and potential application of Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. et Zucc.: a review. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2013, 148, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hu, H.; Wu, Z.; Fan, H.; Wang, G.; Chai, T.; Wang, H. Tissue-specific transcriptome analyses reveal candidate genes for stilbene, flavonoid and anthraquinone biosynthesis in the medicinal plant Polygonum cuspidatum. BMC genomics 2021, 22, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.; Poutaraud, A.; Hugueney, P. Metabolism and roles of stilbenes in plants. Plant science 2009, 177, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, J.A.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2006, 5, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.R.; Scott, E.; Brown, V.A.; Gescher, A.J.; Steward, W.P.; Brown, K. Clinical trials of resveratrol. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2011, 1215, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, C.D.; Rasmussen, B.A.; Duca, F.A.; Zadeh-Tahmasebi, M.; Baur, J.A.; Daljeet, M.; Breen, D.M.; Filippi, B.M.; Lam, T.K. Resveratrol activates duodenal Sirt1 to reverse insulin resistance in rats through a neuronal network. Nature medicine 2015, 21, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasnyó, P.; Molnár, G.A.; Mohás, M.; Markó, L.; Laczy, B.; Cseh, J.; Mikolás, E.; Szijártó, I.A.; Mérei, A.; Halmai, R. Resveratrol improves insulin sensitivity, reduces oxidative stress and activates the Akt pathway in type 2 diabetic patients. British journal of nutrition 2011, 106, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsudin, N.F.; Ahmed, Q.U.; Mahmood, S.; Shah, S.A.A.; Sarian, M.N.; Khattak, M.M.A.K.; Khatib, A.; Sabere, A.S.M.; Yusoff, Y.M.; Latip, J. Flavonoids as antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory agents: A review on structural activity relationship-based studies and meta-analysis. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 12605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Feng, Y.; Yu, S.; Fan, Z.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Yin, H. The flavonoid biosynthesis network in plants. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 12824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarian, M.N.; Ahmed, Q.U.; Mat So’ad, S.Z.; Alhassan, A.M.; Murugesu, S.; Perumal, V.; Syed Mohamad, S.N.A.; Khatib, A.; Latip, J. Antioxidant and antidiabetic effects of flavonoids: A structure-activity relationship based study. BioMed research international 2017, 2017, 8386065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, H.; Zhang, W.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Jiang, Y.; Li, F.; Waterhouse, G.I.; Li, D. Phenolic-protein interactions in foods and post ingestion: Switches empowering health outcomes. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 118, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nabavi, S.M.; Šamec, D.; Tomczyk, M.; Milella, L.; Russo, D.; Habtemariam, S.; Suntar, I.; Rastrelli, L.; Daglia, M.; Xiao, J. Flavonoid biosynthetic pathways in plants: Versatile targets for metabolic engineering. Biotechnology advances 2020, 38, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.S.; Thomas, M.; Clarke, D.J. The gene stlA encodes a phenylalanine ammonia-lyase that is involved in the production of a stilbene antibiotic in Photorhabdus luminescens TT01. Microbiology 2005, 151, 2543–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, J.; Petersen, M. Functional expression and characterization of cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase from the hornwort Anthoceros agrestis in Physcomitrella patens. Plant cell reports 2020, 39, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y. Isoliquiritigenin alleviates diabetic symptoms via activating AMPK and inhibiting mTORC1 signaling in diet-induced diabetic mice. Phytomedicine 2022, 98, 153950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, R.M.; Venkatraman, A.C. Polyphenols activate energy sensing network in insulin resistant models. Chemico-biological interactions 2017, 275, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, A.M.; Ashour, M.B.; Abdel-Moneim, A.; Ahmed, O.M. Hesperidin and naringin attenuate hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokine production in high fat fed/streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetic rats. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications 2012, 26, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ishaq, R.K.; Abotaleb, M.; Kubatka, P.; Kajo, K.; Büsselberg, D. Flavonoids and their anti-diabetic effects: Cellular mechanisms and effects to improve blood sugar levels. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Suchal, K.; Khan, S.I.; Bhatia, J.; Kishore, K.; Dinda, A.K.; Arya, D.S. Apigenin ameliorates streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats via MAPK-NF-κB-TNF-α and TGF-β1-MAPK-fibronectin pathways. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2017, 313, F414–F422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, E.-Y.; Jung, U.J.; Park, T.; Yun, J.W.; Choi, M.-S. Luteolin attenuates hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance through the interplay between the liver and adipose tissue in mice with diet-induced obesity. Diabetes 2015, 64, 1658–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.-e.; Yang, W.; Tian, Z.; Cheng, H. An R2R3-type MYB transcription factor, GmMYB29, regulates isoflavone biosynthesis in soybean. PLoS genetics 2017, 13, e1006770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, S.; Rehman, K.; Shahid, M.; Suhail, S.; Akash, M.S.H. Therapeutic potentials of genistein: New insights and perspectives. Journal of Food Biochemistry 2022, 46, e14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.J.; Kim, G.-H. Daidzein causes cell cycle arrest at the G1 and G2/M phases in human breast cancer MCF-7 and MDA-MB-453 cells. Phytomedicine 2008, 15, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aherne, S.A.; O’Brien, N.M. Dietary flavonols: chemistry, food content, and metabolism. Nutrition 2002, 18, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coskun, O.; Kanter, M.; Korkmaz, A.; Oter, S. Quercetin, a flavonoid antioxidant, prevents and protects streptozotocin-induced oxidative stress and β-cell damage in rat pancreas. Pharmacological research 2005, 51, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Suh, K.S.; Choi, M.C.; Chon, S.; Oh, S.; Woo, J.T.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, Y.S. Kaempferol protects HIT-T15 pancreatic beta cells from 2-deoxy-D-ribose-induced oxidative damage. Phytotherapy Research: An International Journal Devoted to Pharmacological and Toxicological Evaluation of Natural Product Derivatives 2010, 24, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, I.-M.; Liou, S.-S.; Lan, T.-W.; Hsu, F.-L.; Cheng, J.-T. Myricetin as the active principle of Abelmoschus moschatus to lower plasma glucose in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Planta medica 2005, 71, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naing, A.H.; Kim, C.K. Roles of R2R3-MYB transcription factors in transcriptional regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in horticultural plants. Plant molecular biology 2018, 98, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugliera, F.; Tao, G.-Q.; Tems, U.; Kalc, G.; Mouradova, E.; Price, K.; Stevenson, K.; Nakamura, N.; Stacey, I.; Katsumoto, Y. Violet/blue chrysanthemums—metabolic engineering of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway results in novel petal colors. Plant and Cell Physiology 2013, 54, 1696–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Ning, H.; Shao, W.; Song, Z.; Badakhshi, Y.; Ling, W.; Yang, B.B.; Brubaker, P.L.; Jin, T. Dietary cyanidin-3-glucoside attenuates high-fat-diet–induced body-weight gain and impairment of glucose tolerance in mice via effects on the hepatic hormone FGF21. The Journal of nutrition 2020, 150, 2101–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, R.A.; Xie, D.Y.; Sharma, S.B. Proanthocyanidins–a final frontier in flavonoid research? New phytologist 2005, 165, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.; Ismail, C.A.N.; Long, I. Tannins in the treatment of diabetic neuropathic pain: Research progress and future challenges. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 12, 805854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laddha, A.P.; Kulkarni, Y.A. Tannins and vascular complications of Diabetes: An update. Phytomedicine 2019, 56, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, L.J. Structure and chemical properties of the condensed tannins. In Plant Polyphenols: Synthesis, Properties, Significance; Springer: 1992, pp. 245–258.

- Thomas, M.M.G.; Barbosa Filho, J. Anti-inflammatory actions of tannins isolated from the bark of Anacardwm occidentale L. Journal of ethnopharmacology 1985, 13, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, A.; Mubarack, H.M.; Dhanabalan, R. Antibacterial activity of tannins from the leaves of Solanum trilobatum Linn. Indian J Sci Technol 2009, 2, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, M.; Santos, J.S.; Escher, G.B.; do Carmo, M.V.; Azevedo, L.; da Silva, M.C.; Putnik, P.; Granato, D. In vitro antioxidant and antihypertensive compounds from camu-camu (Myrciaria dubia McVaugh, Myrtaceae) seed coat: A multivariate structure-activity study. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2018, 120, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunyanga, C.N.; Imungi, J.K.; Okoth, M.; Momanyi, C.; Biesalski, H.K.; Vadivel, V. Antioxidant and antidiabetic properties of condensed tannins in acetonic extract of selected raw and processed indigenous food ingredients from Kenya. Journal of food science 2011, 76, C560–C567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajebli, M.; Eddouks, M. The promising role of plant tannins as bioactive antidiabetic agents. Current medicinal chemistry 2019, 26, 4852–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perchellet, J.-P.; Gali, H.U.; Perchellet, E.M.; Klish, D.S.; Armbrust, A.D. Antitumor-promoting activities of tannic acid, ellagic acid, and several gallic acid derivatives in mouse skin. Plant Polyphenols: Synthesis, Properties, Significance 1992, 783–801. [Google Scholar]

- Chandak, P.G.; Gaikwad, A.B.; Tikoo, K. Gallotannin ameliorates the development of streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy by preventing the activation of PARP. Phytotherapy Research: An International Journal Devoted to Pharmacological and Toxicological Evaluation of Natural Product Derivatives 2009, 23, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Salih, R. Clinical experimental evidence: synergistic effect of Gallic acid and tannic acid as Antidiabetic and antioxidant agents. Thi-Qar Med. J 2010, 4, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Fachriyah, E.; Eviana, I.; Eldiana, O.; Amaliyah, N.; Sektianingrum, A. Antidiabetic activity from gallic acid encapsulated nanochitosan. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; 2017; p. 012042. [Google Scholar]

- De la Iglesia, R.; Milagro, F.I.; Campión, J.; Boqué, N.; Martínez, J.A. Healthy properties of proanthocyanidins. Biofactors 2010, 36, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, L.; Cai, X.; Dai, X.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extracts ameliorate podocyte injury by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α in low-dose streptozotocin-and high-carbohydrate/high-fat diet-induced diabetic rats. Food & function 2014, 5, 1872–1880. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, D. Lignans. 2019, 24, 1424.

- Hano, C.F.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Davin, L.B.; Cort, J.R.; Lewis, N.G. Lignans: Insights into their biosynthesis, metabolic engineering, analytical methods and health benefits. 2021, 11, 630327. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L.U.; Robb, P.; Serraino, M.; Cheung, F. Mammalian lignan production from various foods. 1991.

- Álvarez-Caballero, J.M.; Coy-Barrera, E. Lignans. In Antioxidants Effects in Health; Elsevier: 2022, pp. 387–416.

- Lampe, J.W. Isoflavonoid and lignan phytoestrogens as dietary biomarkers. The Journal of nutrition 2003, 133, 956S–964S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, T.G.; Nunes, M.A.; Bessada, S.M.; Costa, H.S.; Oliveira, M.B.P. Biologically active and health promoting food components of nuts, oilseeds, fruits, vegetables, cereals, and legumes. In Chemical analysis of food; Elsevier: 2020, pp. 609–656.

- Ding, E.L.; Song, Y.; Malik, V.S.; Liu, S. Sex differences of endogenous sex hormones and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama 2006, 295, 1288–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, C.; Inaba, S.; Kawakami, N.; Kakizoe, T.; Shimizu, H. Inverse association of soy product intake with serum androgen and estrogen concentrations in Japanese men. Nutrition and cancer 2000, 36, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K. Suppression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase gene expression by secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG), a new antidiabetic agent. International Journal of Angiology 2002, 11, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaei, M.; Pan, A. Role of phytoestrogens in prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. World journal of diabetes 2015, 6, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozłowski, R.; Mackiewicz-Talarczyk, M. Handbook of natural fibres; Elsevier: 2012.

- Prasad, K.; Bhanumathy, K.K. Secoisolariciresinol Diglucoside (SDG) from flaxseed in the prevention and treatment of diabetes mellitus. Scripta Medica 2023, 54, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Yang, G.; Huang, L.; Chen, L.; Luo, X.; Shuai, L. Phenol-assisted depolymerisation of condensed lignins to mono-/poly-phenols and bisphenols. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 455, 140628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F.; Jiang, B.; Yuan, Y.; Li, M.; Wu, W.; Jin, Y.; Xiao, H. Biological activities and emerging roles of lignin and lignin-based products─ A review. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 4905–4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitjans, M.; Vinardell, M. Biological activity and health benefits of lignans and lignins. 2005.

- Aniszewski, T. Alkaloids: chemistry, biology, ecology, and applications; Elsevier: 2015.

- Aniszewski, T. Alkaloids-Secrets of Life:: Aklaloid Chemistry, Biological Significance, Applications and Ecological Role; Elsevier: 2007.

- Debnath, B.; Singh, W.S.; Das, M.; Goswami, S.; Singh, M.K.; Maiti, D.; Manna, K. Role of plant alkaloids on human health: A review of biological activities. Materials today chemistry 2018, 9, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, M.-I.; Tchoumtchoua, J.; Skaltsounis, A.-L.; Scorilas, A.; Halabalaki, M. Natural alkaloids intervening the insulin pathway: new hopes for anti-diabetic agents? Current Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 26, 5982–6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarr, F.B.; Sy, G.Y.; Cabral, M.; Dioum, M.D.; Sene, M.; Ndong, A.; Sall, C.; Faye, O. Antioxidant and Anti α-amylase Activities of Polar Extracts of Mitracarpus hirtus and Saba senegalensis and the Combinason of their Butanolic Extracts. International Research Journal of Pure and Applied Chemistry 2021, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Aswal, S.; Semwal, R.B.; Chauhan, A.; Joshi, S.K.; Semwal, D.K. Role of plant-derived alkaloids against diabetes and diabetes-related complications: a mechanism-based approach. Phytochemistry Reviews 2019, 18, 1277–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, H.; Yarani, R.; Pociot, F.; Popović-Djordjević, J. Anti-diabetic potential of plant alkaloids: Revisiting current findings and future perspectives. Pharmacological research 2020, 155, 104723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedekar, A.; Shah, K.; Koffas, M. Natural products for type II diabetes treatment. Advances in applied microbiology 2010, 71, 21–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, M.; Fogarty, S.; Stevenson, C.; Gallagher, A.; Palit, P.; Hawley, S.; Hardie, D.; Coxon, G.; Waigh, R.; Tate, R. Mechanisms underlying the metabolic actions of galegine that contribute to weight loss in mice. British journal of pharmacology 2008, 153, 1669–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiong, S.H.; Looi, C.Y.; Hazni, H.; Arya, A.; Paydar, M.; Wong, W.F.; Cheah, S.-C.; Mustafa, M.R.; Awang, K. Antidiabetic and antioxidant properties of alkaloids from Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don. Molecules 2013, 18, 9770–9784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvarani, C.; Jaivel, N.; Sankaran, M.; Chandraprakash, K.; Ata, A.; Mohan, P.S. Axially chiral biscarbazoles and biological evaluation of the constituents from Murraya koenigii. Fitoterapia 2014, 94, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, N.U.; Ali, A.; Ahmad, B.; Iqbal, N.; Adhikari, A.; Ali, A.; Ali, S.; Jahan, A.; Ali, H.; Ali, I. Evaluation of antidiabetic potential of steroidal alkaloid of Sarcococca saligna. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 100, 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- Rajput, A.; Sharma, R.; Bharti, R. Pharmacological activities and toxicities of alkaloids on human health. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 48, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Zhou, H.; Ma, B.; Ma, Y.; Wu, D.; Wang, X.; Luo, H.; Cheng, N. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of jatrorrhizine, a gastric prokinetic drug candidate. Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition 2012, 33, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, K.A.; Al-Maliki, A.D.M. Moderate effect of phenolic and alkaloid compounds extracted from Brassica oleracea var. capitata leaf on blood glucose level in alloxan-induced diabetic rabbits. World Journal of Experimental Biosciences (ISSN: 2313-3937) 2014, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nadri, M.; Dehpour, A.A.; Yaghubi, S.; Fathi, H.; Ataee, R. Effects of the Anti-diabetic and Anti-neuropathy Effects of Onosma Dichroanthum in an Experimental Model of Diabetes by Streptozocin in Mice. Iranian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism 2017, 19, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Carpinelli de Jesus, M.; Hungerford, N.L.; Carter, S.J.; Anuj, S.R.; Blanchfield, J.T.; De Voss, J.J.; Fletcher, M.T. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids of Blue Heliotrope (Heliotropium amplexicaule) and their presence in Australian honey. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2019, 67, 7995–8006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, P.M.G.; de la Mora, P.G.; Wysocka, W.; Maiztegui, B.; Alzugaray, M.E.; Del Zotto, H.; Borelli, M.I. Quinolizidine alkaloids isolated from Lupinus species enhance insulin secretion. European Journal of Pharmacology 2004, 504, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochalefu, D.O.; Adoga, G.I.; Luka, C.D.; Abu, A.H. Effects of Catechol containing fraction and other fractions of Nauclea latifolia aqueous root-bark extract on blood glucose, lipid profile and serum liver enzymes in streptozotocin–induced diabetic Wistar albino rats. Journal of Stress Physiology & Biochemistry 2024, 20, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Wahab, A.E.; Ghareeb, D.A.; Sarhan, E.E.; Abu-Serie, M.M.; El Demellawy, M.A. In vitro biological assessment of Berberis vulgaris and its active constituent, berberine: antioxidants, anti-acetylcholinesterase, anti-diabetic and anticancer effects. BMC complementary and alternative medicine 2013, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.-T.; Huo, H.-X.; Chao, L.-H.; Song, Y.-L.; Liu, D.-F.; Wang, Z.-W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Tu, P.-F.; Zheng, J. Isoquinoline alkaloids from Corydalis edulis Maxim. Exhibiting insulinotropic action. Phytochemistry 2023, 209, 113637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, D. Antidiabetic activity of aqueous extracts of barks of Alangium salviifolium wang in normal and alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Education 2008, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, J.A.M.; Vitor II, R.J.S. Antihyperglycemic effects of Cajanus cajan L.(pigeon pea) ethanolic extract on the blood glucose levels of ICR mice (Mus musculus l.). National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2017, 7, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S.S.; Sarhat, E.R. Effects of ethanolic Moringa oleifera extract on melatonin, liver and kidney function tests in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology 2019, 13, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Komeili, G.; Hashemi, M.; Bameri-Niafar, M. Evaluation of antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic effects of Peganum harmala seeds in diabetic rats. Cholesterol 2016, 2016, 7389864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devaraji, V.; Sivaraman, J.; Prabhu, S. Large-scale computational screening of Indian medicinal plants reveals Cassia angustifolia to be a potentially anti-diabetic. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2024, 42, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Gupta, K.; Kumar, P.; Guleria, P. Catharensus Roseus Based Alkaloids: Applications and Production. Think India Journal 2019, 22, 3006–3030. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Nachiar, S.; Thiraviam, P.P. A Review of Pharmacological and Phytochemical Studies on Convolvulaceae Species Rivea and Ipomea. Current Traditional Medicine 2022, 8, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, A.; Noori, M.; Ghomi, M.K.; Montazer, M.N.; Iraji, A.; Dastyafteh, N.; Oliyaei, N.; Khoramjouy, M.; Rezaei, Z.; Javanshir, S. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory and hypoglycemic effects of imidazole-bearing thioquinoline derivatives with different substituents: In silico, in vitro, and in vivo evaluations. Bioorganic Chemistry 2024, 144, 107106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiss, M.; Souiy, Z.; Achour, L.; Hamden, K. Ephedra alata extracts exerts anti-obesity, anti-hyperglycemia, anti-antipyretic and analgesic effects. Nutrition & Food Science 2022, 52, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ninkuu, V.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Fu, Z.; Yang, T.; Zeng, H. Biochemistry of terpenes and recent advances in plant protection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, M.; Calzada, F.; Mendieta-Wejebe, J. Structure–activity relationship study of acyclic terpenes in blood glucose levels: potential α-glucosidase and sodium glucose cotransporter (SGLT-1) inhibitors. Molecules 2019, 24, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahy, S.K.; Bhatt, R.; Kumar, A. Targeting type II diabetes with plant terpenes: the new and promising antidiabetic therapeutics. Biologia 2021, 76, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtemariam, S. Antidiabetic potential of monoterpenes: A case of small molecules punching above their weight. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 19, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilic, A. Biological activities of selected mono-amd sesquiterpenes: possible uses in medicine; na: 2013.

- Nazaruk, J.; Borzym-Kluczyk, M. The role of triterpenes in the management of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Phytochemistry Reviews 2015, 14, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, R.; Saldanha, S.N. Dietary phytochemicals, epigenetics, and colon cancer chemoprevention. In Epigenetics of Cancer Prevention; Elsevier: 2019, pp. 205–229.

- Keppler, J.K.; Schwarz, K.; van der Goot, A.J. Covalent modification of food proteins by plant-based ingredients (polyphenols and organosulphur compounds): A commonplace reaction with novel utilization potential. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2020, 101, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, S.H.; Al-Wabel, N. Organosulfur compounds and possible mechanism of garlic in cancer. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2010, 18, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallito, C.J.; Bailey, J.H.; Buck, J.S. The antibacterial principle of Allium sativum. III. Its precursor and “essential oil of garlic”. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1945, 67, 1032–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, E. The organosulfur and organoselenium components of garlic and onions. Phytochemicals-a new paradigm. Technomic Publishing, Lancaster. p 1998, 129-141.

- Sujithra, K.; Srinivasan, S.; Indumathi, D.; Vinothkumar, V. Allyl methyl sulfide, an organosulfur compound alleviates hyperglycemia mediated hepatic oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced experimental rats. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 107, 292–302. [Google Scholar]

- Saravanan, G.; Ponmurugan, P.; Senthilkumar, G.P.; Rajarajan, T. Modulatory effect of S-allylcysteine on glucose metabolism in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Journal of Functional Foods 2009, 1, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, P.; Alvi, S.S.; Iqbal, J.; Khan, M.S. Identification and evaluation of natural organosulfur compounds as potential dual inhibitors of α-amylase and α-glucosidase activity: an in-silico and in-vitro approach. Medicinal Chemistry Research 2021, 30, 2184–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geu-Flores, F.; Nielsen, M.T.; Nafisi, M.; Møldrup, M.E.; Olsen, C.E.; Motawia, M.S.; Halkier, B.A. Glucosinolate engineering identifies a γ-glutamyl peptidase. Nature chemical biology 2009, 5, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuyusuf, M.; Rubel, M.H.; Kim, H.-T.; Jung, H.-J.; Nou, I.-S.; Park, J.-I. Glucosinolates and biotic stress tolerance in Brassicaceae with emphasis on cabbage: A review. Biochemical Genetics 2023, 61, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GOODRICH, R.M.; ANDERSON, J.L.; STOEWSAND, G.S. Glucosinolate changes in blanched broccoli and Brussels sprouts. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 1989, 13, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campas-Baypoli, O.; Sánchez-Machado, D.; Bueno-Solano, C.; Ramírez-Wong, B.; López-Cervantes, J. HPLC method validation for measurement of sulforaphane level in broccoli by-products. Biomedical Chromatography 2010, 24, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Yuan, Q. Natural sulforaphane as a functional chemopreventive agent: including a review of isolation, purification and analysis methods. Critical reviews in biotechnology 2012, 32, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, A.; Soltani, M.; Daraei, A.; Nohbaradar, H.; Haghighi, M.M.; Khosravi, N.; Johnson, K.E.; Laher, I.; Hackney, A.C.; VanDusseldorp, T.A. The effects of aerobic-resistance training and broccoli supplementation on plasma dectin-1 and insulin resistance in males with type 2 diabetes. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y. The protective effect of sulforaphane on type II diabetes induced by high-fat diet and low-dosage streptozotocin. Food Science & Nutrition 2021, 9, 747–756. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, L.P. Bioactivity of polyacetylenes in food plants. In Bioactive foods in promoting health; Elsevier: 2010, pp. 285–306.

- Christensen, L.P.; El-Houri, R.B. Development of an in vitro screening platform for the identification of partial PPARγ agonists as a source for antidiabetic lead compounds. Molecules: A Journal of Synthetic Chemistry and Natural Product Chemistry 2018, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, M.; Gong, M. Overview of Panax ginseng and its active ingredients protective mechanism on cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2024, 118506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Houri, R.B.; Kotowska, D.; Christensen, K.B.; Bhattacharya, S.; Oksbjerg, N.; Wolber, G.; Kristiansen, K.; Christensen, L.P. Polyacetylenes from carrots (Daucus carota) improve glucose uptake in vitro in adipocytes and myotubes. Food & function 2015, 6, 2135–2144. [Google Scholar]

- Resetar, M.; Liu, X.; Herdlinger, S.; Kunert, O.; Pferschy-Wenzig, E.-M.; Latkolik, S.; Steinacher, T.; Schuster, D.; Bauer, R.; Dirsch, V.M. Polyacetylenes from Oplopanax horridus and Panax ginseng: Relationship between structure and PPARγ activation. Journal of natural products 2020, 83, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darenskaya, M.; Kolesnikova, L.a.; Kolesnikov, S. Oxidative stress: pathogenetic role in diabetes mellitus and its complications and therapeutic approaches to correction. Bulletin of experimental biology and medicine 2021, 171, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ježek, P.; Hlavatá, L. Mitochondria in homeostasis of reactive oxygen species in cell, tissues, and organism. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2005, 37, 2478–2503. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.; Mackey, M.M.; Diaz, A.A.; Cox, D.P. Hydroxyl radical is produced via the Fenton reaction in submitochondrial particles under oxidative stress: implications for diseases associated with iron accumulation. Redox Report 2009, 14, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaliszewska, A.; Allison, J.; Martini, M.; Arias, N. Improving Age-Related Cognitive Decline through Dietary Interventions Targeting Mitochondrial Dysfunction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 3574–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernansanz-Agustín, P.; Enríquez, J.A. Generation of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okado-Matsumoto, A.; Fridovich, I. Subcellular distribution of superoxide dismutases (SOD) in rat liver: Cu, Zn-SOD in mitochondria. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 38388–38393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vásquez-Vivar, J.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Kennedy, M.C. Mitochondrial aconitase is a source of hydroxyl radical: an electron spin resonance investigation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275, 14064–14069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.; Chakraborty, R. The role of antioxidants in human health. In Oxidative stress: diagnostics, prevention, and therapy; ACS Publications: 2011, pp. 1–37.

- Snezhkina, A.V.; Kudryavtseva, A.V.; Kardymon, O.L.; Savvateeva, M.V.; Melnikova, N.V.; Krasnov, G.S.; Dmitriev, A.A. ROS generation and antioxidant defense systems in normal and malignant cells. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2019, 2019, 6175804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B. Antioxidants in human health and disease. Annual review of nutrition 1996, 16, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panday, A.; Sahoo, M.K.; Osorio, D.; Batra, S. NADPH oxidases: an overview from structure to innate immunity-associated pathologies. Cellular & molecular immunology 2015, 12, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Structure and function of xanthine oxidoreductase: where are we now? Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2002, 33, 774–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaludercic, N.; Mialet-Perez, J.; Paolocci, N.; Parini, A.; Di Lisa, F. Monoamine oxidases as sources of oxidants in the heart. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 2014, 73, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, L.A. Peroxisomes as a cellular source of reactive nitrogen species signal molecules. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2011, 506, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürstenberger, G.; Krieg, P.; Müller-Decker, K.; Habenicht, A. What are cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases doing in the driver's seat of carcinogenesis? International journal of cancer 2006, 119, 2247–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfadda, A.A.; Sallam, R.M. Reactive oxygen species in health and disease. BioMed research international 2012, 2012, 936486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, H.S. A synopsis of the associations of oxidative stress, ROS, and antioxidants with diabetes mellitus. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, T.; Wu, X.; Nice, E.C.; Huang, C.; Zhang, Y. Oxidative stress and diabetes: antioxidative strategies. Frontiers of medicine 2020, 14, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbani, N.; Thornalley, P.J. Dicarbonyl stress in cell and tissue dysfunction contributing to ageing and disease. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2015, 458, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, R.; Böhme, D.; Singer, D.; Frolov, A. Specific tandem mass spectrometric detection of AGE-modified arginine residues in peptides. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2015, 50, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalkwijk, C.; Stehouwer, C. Methylglyoxal, a highly reactive dicarbonyl compound, in diabetes, its vascular complications, and other age-related diseases. Physiological reviews 2020, 100, 407–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornalley, P.J.; Langborg, A.; Minhas, H.S. Formation of glyoxal, methylglyoxal and 3-deoxyglucosone in the glycation of proteins by glucose. Biochemical Journal 1999, 344, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vistoli, G.; De Maddis, D.; Cipak, A.; Zarkovic, N.; Carini, M.; Aldini, G. Advanced glycoxidation and lipoxidation end products (AGEs and ALEs): an overview of their mechanisms of formation. Free radical research 2013, 47, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beisswenger, P.J.; Howell, S.K.; Smith, K.; Szwergold, B.S. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity as an independent modifier of methylglyoxal levels in diabetes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2003, 1637, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray Chaudhuri, A.; Nussenzweig, A. The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2017, 18, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Matsumura, T.; Edelstein, D.; Rossetti, L.; Zsengellér, Z.; Szabó, C.; Brownlee, M. Inhibition of GAPDH activity by poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase activates three major pathways of hyperglycemic damage in endothelial cells. The Journal of clinical investigation 2003, 112, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, S.; Adole, P.S.; Motupalli, N.; Pandit, V.R.; Vinod, K.V. Association between carbonyl stress markers and the risk of acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus–A pilot study. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2020, 14, 1751–1755. [Google Scholar]

- Leonova, T.; Popova, V.; Tsarev, A.; Henning, C.; Antonova, K.; Rogovskaya, N.; Vikhnina, M.; Baldensperger, T.; Soboleva, A.; Dinastia, E. Does protein glycation impact on the drought-related changes in metabolism and nutritional properties of mature pea (Pisum sativum L.) seeds? International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishizuka, Y. Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. The FASEB journal 1995, 9, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleicher, E.D.; Weigert, C. Role of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney international 2000, 58, S13–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martemucci, G.; Costagliola, C.; Mariano, M.; D’andrea, L.; Napolitano, P.; D’Alessandro, A.G. Free radical properties, source and targets, antioxidant consumption and health. Oxygen 2022, 2, 48–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanasundaram, T.; Ramachandran, V.; Bhongiri, B.; Rymbai, E.; Xavier, R.M.; Rao, G.N.; Narendar, C. The Promotion of Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity by Nrf2 Amplifier is A Potential Technique in Diabetic Wound Healing—A Review. Pharmaceutical Sciences 2022, 29, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, A.; Manda, G.; Hassan, A.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Barbas, C.; Daiber, A.; Ghezzi, P.; León, R.; López, M.G.; Oliva, B. Transcription factor NRF2 as a therapeutic target for chronic diseases: a systems medicine approach. Pharmacological reviews 2018, 70, 348–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzinger, M.; Fischhuber, K.; Heiss, E.H. Activation of Nrf2 signaling by natural products-can it alleviate diabetes? Biotechnology advances 2018, 36, 1738–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Kang, M.-I.; Okawa, H.; Ohtsuji, M.; Zenke, Y.; Chiba, T.; Igarashi, K.; Yamamoto, M. Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Molecular and cellular biology 2004, 24, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonelli, C.; Chio, I.I.C.; Tuveson, D.A. Transcriptional regulation by Nrf2. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2018, 29, 1727–1745. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.; Ru, X.; Wen, T. NRF2, a transcription factor for stress response and beyond. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, I.; Sehgal, A.; Sharma, E.; Kumar, A.; Grover, M.; Bungau, S. Unfolding Nrf2 in diabetes mellitus. Molecular Biology Reports 2021, 48, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorwald, M.A.; Godoy-Lugo, J.A.; Rodriguez, R.; Stanhope, K.L.; Graham, J.L.; Havel, P.J.; Forman, H.J.; Ortiz, R.M. Cardiac NF-κB Acetylation Increases While Nrf2-Related Gene Expression and Mitochondrial Activity Are Impaired during the Progression of Diabetes in UCD-T2DM Rats. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Panieri, E.; Profumo, E.; Saso, L. An overview of Nrf2 signaling pathway and its role in inflammation. Molecules 2020, 25, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Mao, L. The absence of Nrf2 enhances NF-κB-dependent inflammation following scratch injury in mouse primary cultured astrocytes. Mediators of inflammation 2012, 2012, 217580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajappa, R.; Sireesh, D.; Salai, M.B.; Ramkumar, K.M.; Sarvajayakesavulu, S.; Madhunapantula, S.V. Treatment with naringenin elevates the activity of transcription factor Nrf2 to protect pancreatic β-cells from streptozotocin-induced diabetes in vitro and in vivo. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2019, 9, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Eggler, A.L.; Mesecar, A.D.; Van Breemen, R.B. Modification of keap1 cysteine residues by sulforaphane. Chemical research in toxicology 2011, 24, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.W.; Chun, K.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, N.-C.; Na, H.-K.; Surh, Y.-J. Curcumin induces stabilization of Nrf2 protein through Keap1 cysteine modification. Biochemical Pharmacology 2020, 173, 113820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, G.; Kumar, A.; S Sharma, S. Nrf2 and NF-κB modulation by sulforaphane counteracts multiple manifestations of diabetic neuropathy in rats and high glucose-induced changes. Current neurovascular research 2011, 8, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utami, A.R.; Maksum, I.P.; Deawati, Y. Berberine and its study as an antidiabetic compound. Biology 2023, 12, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.P.W.; Ng, M.Y.; Leung, J.Y.; Boh, B.K.; Lim, E.C.; Tan, S.H.; Lim, S.; Seah, W.H.; Hu, C.Z.; Ho, B.C. Regulation of the NRF2 transcription factor by andrographolide and organic extracts from plant endophytes. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0204853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshatha, V.; Nalini, M.; D'souza, C.; Prakash, H. Streptomycete endophytes from anti-diabetic medicinal plants of the Western Ghats inhibit alpha-amylase and promote glucose uptake. Letters in applied microbiology 2014, 58, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Chen, T.; Cuong, T.D.; Quy, P.T.; Bui, T.Q.; Van Tuan, L.; Van Hue, N.; Triet, N.T.; Ho, D.V.; Bao, N.C.; Nhung, N.T.A. Antioxidant activity and α-glucosidase inhibitability of Distichochlamys citrea MF Newman rhizome fractionated extracts: in vitro and in silico screenings. Chemical Papers 2022, 76, 5655–5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proença, C.; Ribeiro, D.; Freitas, M.; Fernandes, E. Flavonoids as potential agents in the management of type 2 diabetes through the modulation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase activity: a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 62, 3137–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bag, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.K.; Chattopadhyay, R.R. The development of Terminalia chebula Retz.(Combretaceae) in clinical research. Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine 2013, 3, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.S.; Banegas-Luna, A.J.; Peña-García, J.; Pérez-Sánchez, H.; Apostolides, Z. Evaluation of the anti-diabetic activity of some common herbs and spices: providing new insights with inverse virtual screening. Molecules 2019, 24, 4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. The PI3K/AKT pathway in obesity and type 2 diabetes. International journal of biological sciences 2018, 14, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, G. Insulin and insulin resistance. Clinical biochemist reviews 2005, 26, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, I.; Rahman, N.; Nishan, U.; Shah, M. Antidiabetic activities of alkaloids isolated from medicinal plants. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2021, 57, e19130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putta, S.; Sastry Yarla, N.; Kumar Kilari, E.; Surekha, C.; Aliev, G.; Basavaraju Divakara, M.; Sridhar Santosh, M.; Ramu, R.; Zameer, F.; Prasad MN, N. Therapeutic potentials of triterpenes in diabetes and its associated complications. Current topics in medicinal chemistry 2016, 16, 2532–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, L.W.; Boll, M.; Stampfl, A. Maintaining cholesterol homeostasis: sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG 2004, 10, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloise, R.; Reinhart, C. EPAISSISSEMENTS DE PULPES. MODELISATION DU PROCESSUS DISCONTINU. 1981. [Google Scholar]

- DeBose-Boyd, R.A.; Ye, J. SREBPs in lipid metabolism, insulin signaling, and beyond. Trends in biochemical sciences 2018, 43, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Gupta, P.; Saini, A.S.; Kaushal, C.; Sharma, S. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor: A family of nuclear receptors role in various diseases. Journal of advanced pharmaceutical technology & research 2011, 2, 236–240. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mansoori, L.; Al-Jaber, H.; Prince, M.S.; Elrayess, M.A. Role of inflammatory cytokines, growth factors and adipokines in adipogenesis and insulin resistance. Inflammation 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, D.; Tian, R. Glucose transporters in cardiac metabolism and hypertrophy. Comprehensive Physiology 2015, 6, 331. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, J.; Moller, D.E. The mechanisms of action of PPARs. Annual review of medicine 2002, 53, 409–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Waltenberger, B.; Pferschy-Wenzig, E.-M.; Blunder, M.; Liu, X.; Malainer, C.; Blazevic, T.; Schwaiger, S.; Rollinger, J.M.; Heiss, E.H. Natural product agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ): a review. Biochemical pharmacology 2014, 92, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Egan, J.M. The role of incretins in glucose homeostasis and diabetes treatment. Pharmacological reviews 2008, 60, 470–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinho, R.; Mega, C.; Teixeira-de-Lemos, E.; Carvalho, E.; Teixeira, F.; Fernandes, R.; Reis, F. The place of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes therapeutics: A “me too” or “the special one” antidiabetic class? Journal of diabetes research 2015, 2015, 806979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yabe, D.; Seino, Y. Two incretin hormones GLP-1 and GIP: comparison of their actions in insulin secretion and β cell preservation. Progress in biophysics and molecular biology 2011, 107, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cernea, S.; Raz, I. Therapy in the early stage: incretins. Diabetes care 2011, 34, S264–S271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, E.H.; Sayed, A.M.; Hussein, O.E.; Mahmoud, A.M. Coumarins as modulators of the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2020, 2020, 1675957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, S.; Sarker, M.M.R.; Sultana, T.N.; Chowdhury, M.N.R.; Rashid, M.A.; Chaity, N.I.; Zhao, C.; Xiao, J.; Hafez, E.E.; Khan, S.A. Antidiabetic phytochemicals from medicinal plants: prospective candidates for new drug discovery and development. Frontiers in endocrinology 2022, 13, 800714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-S.; Chyau, C.-C.; Wang, C.-P.; Wang, T.-H.; Chen, J.-H.; Lin, H.-H. Flavonoids identification and pancreatic beta-cell protective effect of lotus seedpod. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Sahana, G.R.; Nagella, P.; Joseph, B.V.; Alessa, F.M.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q. Flavonoids as potential anti-inflammatory molecules: A review. Molecules 2022, 27, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Rao, B. The effects of taurine supplementation on diabetes mellitus in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Chemistry: Molecular Sciences 2022, 4, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, K.N.C.; Manchali, S. Anti-diabetic potentials of red beet pigments and other constituents. In Red Beet Biotechnology: Food and Pharmaceutical Applications; Springer: 2012, pp. 155–174.

- Madadi, E.; Mazloum-Ravasan, S.; Yu, J.S.; Ha, J.W.; Hamishehkar, H.; Kim, K.H. Therapeutic application of betalains: A review. Plants 2020, 9, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, A.R. Insulin signaling in health and disease. The Journal of clinical investigation 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Huang, X.-J.; Chen, G.-X. Current understanding of glucose transporter 4 expression and functional mechanisms. World journal of biological chemistry 2020, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelsalam, S.S.; Korashy, H.M.; Zeidan, A.; Agouni, A. The role of protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP)-1B in cardiovascular disease and its interplay with insulin resistance. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Cline, D.L.; Glavas, M.M.; Covey, S.D.; Kieffer, T.J. Tissue-specific effects of leptin on glucose and lipid metabolism. Endocrine reviews 2021, 42, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Barouch, L.A. Leptin signaling and obesity: cardiovascular consequences. Circulation research 2007, 101, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuk, V.A.e.; Vorotnikov, A.V. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance development. Diabetes mellitus 2014, 17, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.T.; Nguyen, D.H.; Le, D.D.; Choi, J.S.; Min, B.S.; Woo, M.H. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors from natural sources. Archives of pharmacal research 2018, 41, 130–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingwoke, E.J.; Adamude, F.A.; Chukwuocha, C.E.; Ambi, A.A.; Nwobodo, N.N.; Sallau, A.B.; Nzelibe, H.C. Inhibition of trypanosoma evansi protein-tyrosine phosphatase by myristic acid analogues isolated from khaya senegalensis and tamarindus indica. Journal of Experimental Pharmacology 2019, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitschmann, A.; Zehl, M.; Atanasov, A.G.; Dirsch, V.M.; Heiss, E.; Glasl, S. Walnut leaf extract inhibits PTP1B and enhances glucose-uptake in vitro. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2014, 152, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LC, M. Action of amino acids on sugars. Formation of melanoidins in a methodical way. Compte-Rendu de l'Academie des Science 1912, 154, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Heyns, K.; Noack, H. Die Umsetzung von D-Fructose mit L-Lysin und L-Arginin und deren Beziehung zu nichtenzymatischen Bräunungsreaktionen. Chemische Berichte 1962, 95, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadori, M. The product of the condensation of glucose and p-phenetidine. Atti Reale Accad Nazl Lincei 1929, 9, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee, M.; VLASSARA, H.; Cerami, A. Nonenzymatic glycosylation and the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. Annals of internal medicine 1984, 101, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Barden, A.; Mori, T.; Beilin, L. Advanced glycation end-products: a review. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khetarpaul, N.; Chauhan, B. Improvement in HCl-extractability of minerals from pearl millet by natural fermentation. Food chemistry 1990, 37, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, S.P.; Dean, R. Glucose autoxidation and protein modification. The potential role of ‘autoxidative glycosylation’in diabetes. Biochemical journal 1987, 245, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajithlal, G.; Chandrakasan, G. Role of lipid peroxidation products in the formation of advanced glycation end products: An in vitro study on collagen. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences-Chemical Sciences, 1999; pp. 215–229.

- Hayashi, T.; Namiki, M. Role of sugar fragmentation in an early stage browning of amino-carbonyl reaction of sugar with amino acid. Agricultural and biological chemistry 1986, 50, 1965–1970. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn, J.V.; Stitt, A.W. The role of advanced glycation end products in retinal ageing and disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects 2009, 1790, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, S. Advanced glycation end products (AGE)-modified proteins and their potential relevance to atherosclerosis. Trends in cardiovascular medicine 1996, 6, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Liu, J.; Dong, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Novel advances in inhibiting advanced glycation end product formation using natural compounds. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 140, 111750. [Google Scholar]

- Uribarri, J.; Woodruff, S.; Goodman, S.; Cai, W.; Chen, X.; Pyzik, R.; Yong, A.; Striker, G.E.; Vlassara, H. Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2010, 110, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerami, C.; Founds, H.; Nicholl, I.; Mitsuhashi, T.; Giordano, D.; Vanpatten, S.; Lee, A.; Al-Abed, Y.; Vlassara, H.; Bucala, R. Tobacco smoke is a source of toxic reactive glycation products. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1997, 94, 13915–13920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, J.; Morrissey, P.; Ames, J. Nutritional and toxicological aspects of the Maillard browning reaction in foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition 1989, 28, 211–248. [Google Scholar]

- https://lemchem.file3.wcms.tu-dresden.de//.

- Delgado-Andrade, C. Carboxymethyl-lysine: thirty years of investigation in the field of AGE formation. Food & function 2016, 7, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Twarda-Clapa, A.; Olczak, A.; Białkowska, A.M.; Koziołkiewicz, M. Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs): Formation, chemistry, classification, receptors, and diseases related to AGEs. Cells 2022, 11, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, R.D.; Nicklett, E.J.; Ferrucci, L. Does accumulation of advanced glycation end products contribute to the aging phenotype? Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences 2010, 65, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhipa, A.S.; Borse, S.P.; Baksi, R.; Lalotra, S.; Nivsarkar, M. Targeting receptors of advanced glycation end products (RAGE): Preventing diabetes induced cancer and diabetic complications. Pathology-Research and Practice 2019, 215, 152643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, V.P.; Aryal, P.; Darkwah, E.K. Advanced glycation end products in health and disease. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeper, M.; Schmidt, A.M.; Brett, J.; Yan, S.; Wang, F.; Pan, Y.; Elliston, K.; Stern, D.; Shaw, A. Cloning and expression of a cell surface receptor for advanced glycosylation end products of proteins. Journal of biological chemistry 1992, 267, 14998–15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavakis, T.; Bierhaus, A.; Al-Fakhri, N.; Schneider, D.; Witte, S.; Linn, T.; Nagashima, M.; Morser, J.; Arnold, B.; Preissner, K.T. The pattern recognition receptor (RAGE) is a counterreceptor for leukocyte integrins: a novel pathway for inflammatory cell recruitment. The Journal of experimental medicine 2003, 198, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, C.; Jacobs, K.; Haucke, E.; Santos, A.N.; Grune, T.; Simm, A. Role of advanced glycation end products in cellular signaling. Redox biology 2014, 2, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongarzone, S.; Savickas, V.; Luzi, F.; Gee, A.D. Targeting the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE): a medicinal chemistry perspective. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2017, 60, 7213–7232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jules, J.; Maiguel, D.; Hudson, B.I. Alternative splicing of the RAGE cytoplasmic domain regulates cell signaling and function. PloS one 2013, 8, e78267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bukulin, M.; Kojro, E.; Roth, A.; Metz, V.V.; Fahrenholz, F.; Nawroth, P.P.; Bierhaus, A.; Postina, R. Receptor for advanced glycation end products is subjected to protein ectodomain shedding by metalloproteinases. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 35507–35516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.P.; Bali, A.; Singh, N.; Jaggi, A.S. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications. The Korean journal of physiology & pharmacology: official journal of the Korean Physiological Society and the Korean Society of Pharmacology 2014, 18, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Ramdas, M.; Zhu, L.; Chen, X.; Striker, G.E.; Vlassara, H. Oral advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) promote insulin resistance and diabetes by depleting the antioxidant defenses AGE receptor-1 and sirtuin 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 15888–15893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Khan, S.; Almatroudi, A.; Khan, A.A.; Alsahli, M.A.; Almatroodi, S.A.; Rahmani, A.H. A review on mechanism of inhibition of advanced glycation end products formation by plant derived polyphenolic compounds. Molecular Biology Reports 2021, 48, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wautier, M.-P.; Chappey, O.; Corda, S.; Stern, D.M.; Schmidt, A.M.; Wautier, J.-L. Activation of NADPH oxidase by AGE links oxidant stress to altered gene expression via RAGE. American journal of physiology-endocrinology and metabolism 2001, 280, E685–E694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Méndez, J.D.; Méndez-Valenzuela, V.; Aguilar-Hernández, M.M. Cellular signalling of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). Cellular signalling 2013, 25, 2185–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daffu, G.; Del Pozo, C.H.; O’Shea, K.M.; Ananthakrishnan, R.; Ramasamy, R.; Schmidt, A.M. Radical roles for RAGE in the pathogenesis of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases and beyond. International journal of molecular sciences 2013, 14, 19891–19910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younus, H.; Anwar, S. Prevention of non-enzymatic glycosylation (glycation): Implication in the treatment of diabetic complication. International journal of health sciences 2016, 10, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.Y.; Kim, Y.S. The role of advanced glycation end products in diabetic vascular complications. Diabetes & metabolism journal 2018, 42, 188–195. [Google Scholar]

- Demain, A.L.; Fang, A. The natural functions of secondary metabolites. History of modern biotechnology I 2000, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Hogger, P. Dietary polyphenols and type 2 diabetes: current insights and future perspectives. Current medicinal chemistry 2015, 22, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, J.; Mahomoodally, M.; Ahmed, N.; Subratty, A. Antioxidant and anti–glycation activities correlates with phenolic composition of tropical medicinal herbs. Asian Pacific journal of tropical medicine 2013, 6, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.-C. Anti-glycative potential of triterpenes: a mini-review. BioMedicine 2012, 2, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]