Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This review critically examines the integration of biomimicry, nature-inspired algorithms (NIAs), and swarm robotics to enhance sustainability, automation, and efficiency in mining operations. The paper begins by defining the foundational concepts of biomimicry, highlighting how nature-inspired designs have influenced engineering, architecture, and other fields. It then explores NIAs, discussing how biological processes such as foraging, evolution, and swarming have been modelled to solve complex optimization problems. Swarm robotics, largely inspired by the collective behaviour of social insects and other natural systems, is also analysed for its potential to revolutionize autonomous exploration, material transport, and excavation in dynamic mining environments. The synergy between biomimicry, NIAs, and swarm robotics is assessed for its applicability in addressing key challenges in the mining sector, including safety, resource management, and environmental sustainability. Systematic review of current technologies and future potential applications is presented, offering strategic insights into how these innovations can drive the transition towards fully automated and sustainable mining practices.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biomimicry

2.1. Conceptual Foundations of Biomimicry

2.2. Applications of Biomimicry in Engineering and Design

3. Nature-Inspired Algorithms (NIAs)

3.1. Theoretical Foundations of Nature-Inspired Algorithms

3.2. NIA Classification

3.3. Swarm-Based Bioinspired Algorithms

3.3.1. Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) Algorithm

3.3.2. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) Algorithm

3.3.3. Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) Algorithm

3.3.4. Firefly Algorithm (FA)

3.3.5. Bat Algorithm (BA)

3.3.6. Krill Herding (KH) Algorithm

3.3.7. Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) Algorithm

3.3.8. Salp Swarm Algorithm (SSA)

3.3.9. Grasshopper Optimization Algorithm (GOA)

4. Swarm Robotics: Concepts and Applications

4.1. Swarm Robotics Application in Various Industries

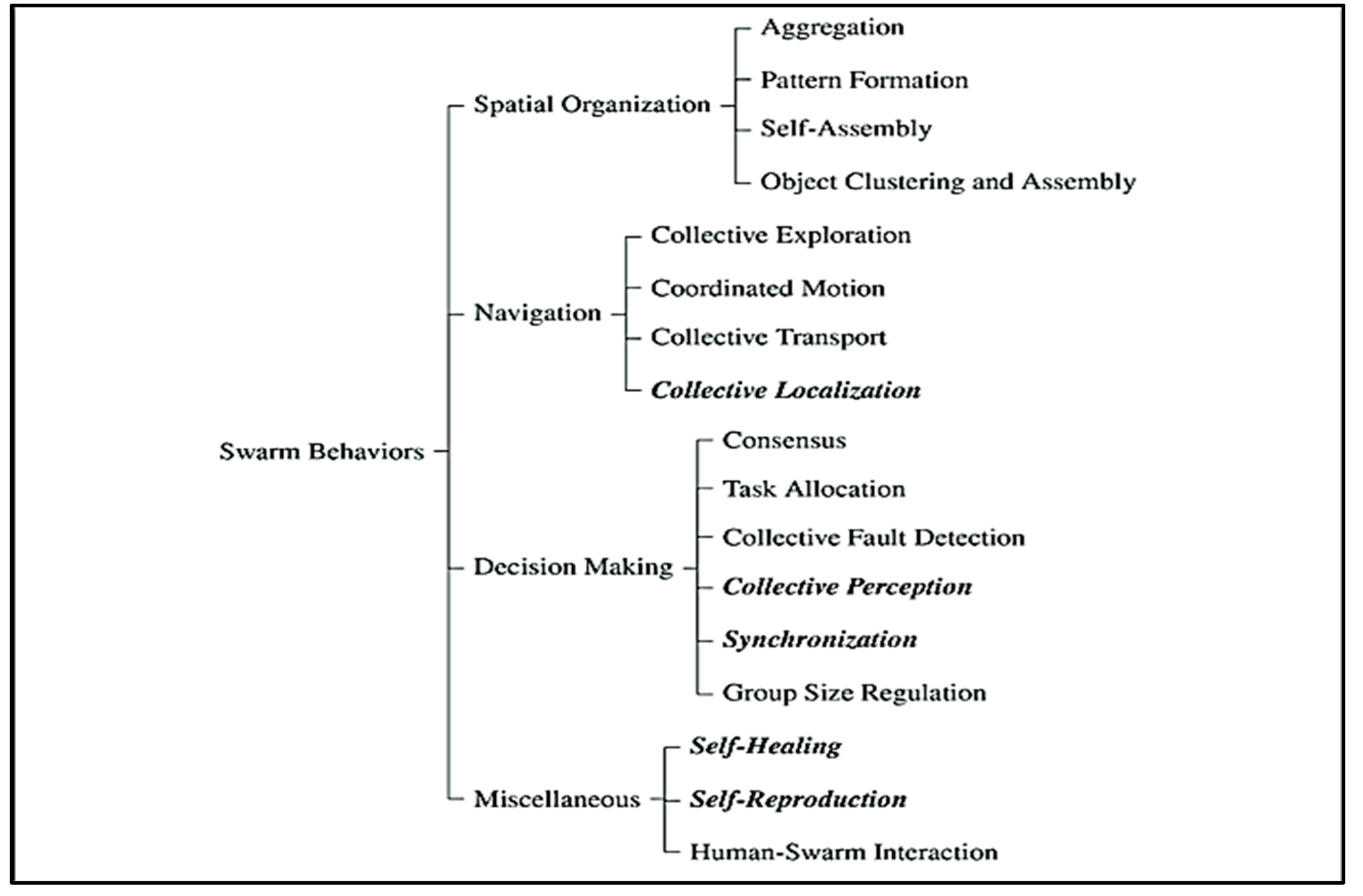

4.2. Swarm Robotics Behaviour Classification

4.2.1. Spatial Organization

4.2.2. Navigation

4.2.3. Decision Making

4.2.4. Miscellaneous

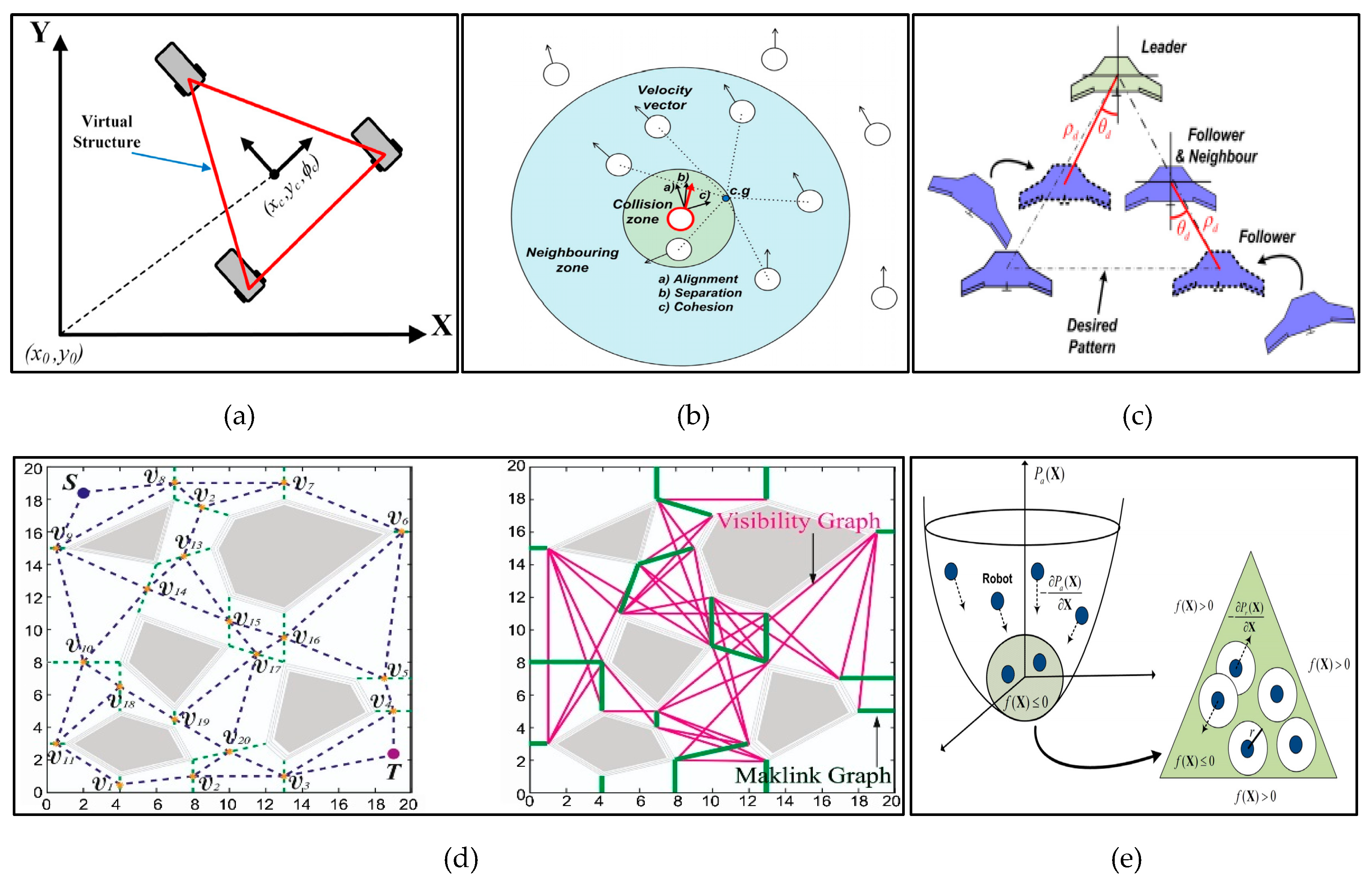

4.3. Swarm Robotics Formation Control

4.3.1. Centralized Control vs Decentralised Control

4.3.2. Virtual Structure Approach

4.3.3. Behaviour-Based Approach

4.3.4. Leader-Follower Approach

4.3.5. Graph-Based Approach

4.3.6. Artificial Potential Approach

5. Applications of NIAs, Biomimicry and Swarm Robotics in Mining

5.1. NIAs in Mining

5.1.1. Exploration and resource Management

5.1.2. Mine Planning and Logistical Optimization

5.1.3. Mine Safety and Risk Management

5.1.4. Mine Environmental Sustainability

5.1.5. Overview of NIAs in Mining Applications

5.2. Biomimicry in Mining

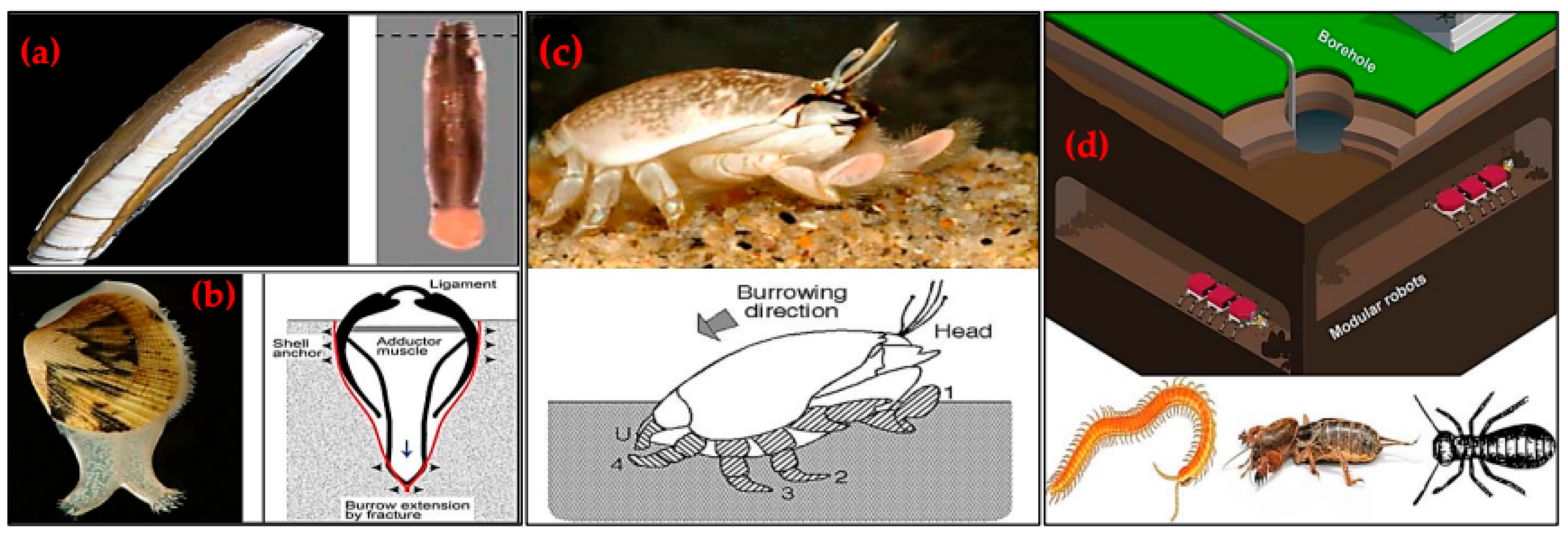

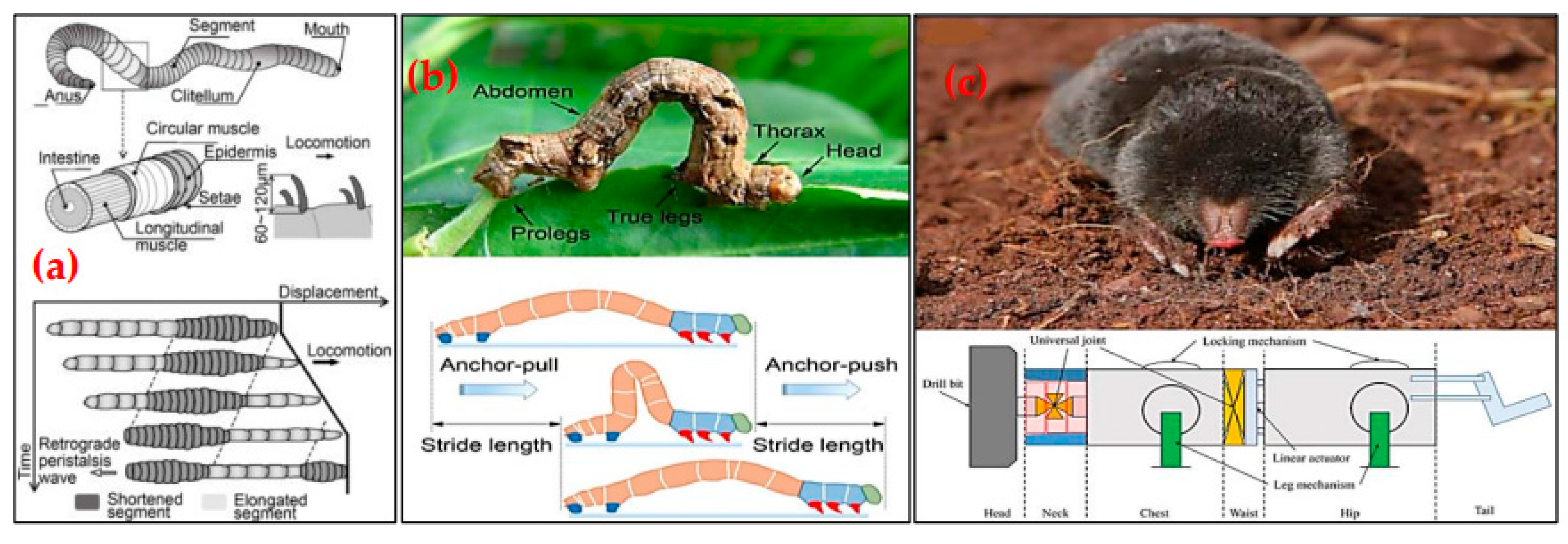

5.2.1. Mining Excavation and Drilling

5.2.2. Mining Exploration and Mapping

5.3. Swarm Robotics in Mining

5.3.1. Mining Operational

5.3.2. Mining Research and Development

6. Future Directions and Research Gaps

6.1. Emerging Research Areas

6.2. Technological Barriers and Challenges

6.3. Opportunities for Cross-Disciplinary Research

7. Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benyus, J. (1997). Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature. Harper Perennial.

- Omar, M., Akash, B., & Sheraz, U. (2015). Applications of biomimicry in engineering design. Journal of Bionic Engineering, 12(1), 24-35.

- Akash, G.M., 2020. Application of biomimetics in design of vehicles–A review. Int Res J Eng Technol, 7(3), pp.2753-2759.

- Cheraghi, A.R., Shahzad, S., & Graffi, K. (2022). Past, present, and future of swarm robotics. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.00671.

- Shibeshi, T.S. (2009). Urban planning inspired by ant colony organization. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 13(2), 157-172.

- Hutchins, E. (2012). Biomimicry in architecture: Cooling systems inspired by termite mounds. Architectural Science Review, 55(1), 45-56.

- Bertayeva, K., Panaedova, G., Natocheeva, N. and Belyanchikova, T., 2019. Industry 4.0 in the mining industry: Global trends and innovative development. In E3S Web of conferences (Vol. 135, p. 04026). EDP Sciences.

- Jenkins, H. , 2004. Corporate social responsibility and the mining industry: conflicts and constructs. Corporate social responsibility and environmental management, 11(1), pp.23-34.

- Rogers, W.P., Kahraman, M.M., Drews, F.A., Powell, K., Haight, J.M., Wang, Y., Baxla, K. and Sobalkar, M., 2019. Automation in the mining industry: Review of technology, systems, human factors, and political risk. Mining, metallurgy & exploration, 36, pp.607-631.

- Carvalho, F.P. , 2017. Mining industry and sustainable development: time for change. Food and Energy security, 6(2), pp.61-77.

- Kalisz, S., Kibort, K., Mioduska, J., Lieder, M. and Małachowska, A., 2022. Waste management in the mining industry of metals ores, coal, oil and natural gas-A review. Journal of environmental management, 304, p.114239.

- McNab, K. and Garcia-Vasquez, M., 2011. Autonomous and remote operation technologies in Australian mining. Brisbane City, Australia: Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining (CSRM)-Sustainable Minerals Institute, University of Queensland.

- Singh, G., Singh, S.K., Chaurasia, R.C. and Jain, A.K., 2024. THE PRESENT AND FUTURE PROSPECT OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN THE MINING INDUSTRY. Machine Learning, 53(4).

- Onifade, M., Zvarivadza, T., Adebisi, J.A., Said, K.O., Dayo-Olupona, O., Lawal, A.I. and Khandelwal, M., 2024. Advancing toward sustainability: The emergence of green mining technologies and practices. Green and Smart Mining Engineering, 1(2), pp.157-174.

- Tan, J., Melkoumian, N., Akmeliawati, R., & Harvey, D., 2021. Design and application of swarm robotics system using ABCO method for off-Earth mining. Fifth International Future Mining Conference 2021. AusIMM.

- Tan, J., Melkoumian, N., Harvey, D. and Akmeliawati, R., 2024. Evaluating Swarm Robotics for Diverse Mining Environments: Insights into Model Performance and Application.

- Brambilla, M., Ferrante, E., Birattari, M. and Dorigo, M., 2013. Swarm robotics: a review from the swarm engineering perspective. Swarm Intelligence, 7, pp.1-41.

- Schranz, M., Umlauft, M., Sende, M. and Elmenreich, W., 2020. Swarm robotic behaviors and current applications. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 7, p.36.

- Trianni, V., IJsselmuiden, J. and Haken, R., 2016. The Saga Concept: Swarm Robotics for Agricultural Applications. Technical Report. 2016. Available online: http://laral. istc. cnr. it/saga/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sagadars2016. pdf (accessed on 23 August 2018).

- Sawant, R., Singh, C., Shaikh, A., Aggarwal, A., Shahane, P. and Harikrishnan, R., 2022, January. Mine Detection using a Swarm of Robots. In 2022 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Applied Informatics (ACCAI) (pp. 1-9). IEEE.

- Young, C., Papadopoulos, L., Wendorf, M. and Williams, M., 2021. Biomimicry: 9 Ways Engineers Have Been `Inspired` by Nature. [online] Interestingengineering.com. 21 September. Available online: https://interestingengineering.com/biomimicry-9-ways-engineers-have-been-inspired-by-nature (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Wen, L., Weaver, J.C. and Lauder, G.V., 2014. Biomimetic shark skin: design, fabrication and hydrodynamic function. Journal of experimental Biology, 217(10), pp.1656-1666.

- Ab Wahab, M.N., Nefti-Meziani, S. and Atyabi, A., 2015. A comprehensive review of swarm optimization algorithms. PloS one, 10(5), p.e0122827.

- Darvishpoor, S., Darvishpour, A., Escarcega, M. and Hassanalian, M., 2023. Nature-inspired algorithms from oceans to space: a comprehensive review of heuristic and meta-heuristic optimization algorithms and their potential applications in drones. Drones, 7(7), p.427.

- Houssein, E.H., Younan, M. and Hassanien, A.E., 2019. Nature-inspired algorithms: A comprehensive review. Hybrid Computational Intelligence, pp.1-25.

- Fister Jr, I., Yang, X.S., Fister, I., Brest, J. and Fister, D., 2013. A brief review of nature-inspired algorithms for optimization. arXiv:1307.4186.

- Mirjalili, S., Gandomi, A.H., Mirjalili, S.Z., Saremi, S., Faris, H. and Mirjalili, S.M., 2017. Salp Swarm Algorithm: A bio-inspired optimizer for engineering design problems. Advances in Engineering Software, 114, pp.163-191.

- Dhiman, G. and Kumar, V., 2017. Spotted hyena optimizer: a novel bio-inspired based metaheuristic technique for engineering applications. Advances in Engineering Software, 114, pp.48-70.

- Zang, H., Zhang, S. and Hapeshi, K., 2010. A review of nature-inspired algorithms. Journal of Bionic Engineering, 7(4), pp. S232-S237.

- Abualigah, L., Shehab, M., Alshinwan, M. and Alabool, H., 2020. Salp swarm algorithm: a comprehensive survey. Neural Computing and Applications, 32(15), pp.11195-11215.

- Abualigah, L.M., Sawaie, A.M., Khader, A.T., Rashaideh, H., Al-Betar, M.A. and Shehab, M., 2017. β-hill climbing technique for the text document clustering. New Trends in Information Technology (NTIT)–2017, 60.

- Glover, F., 1989. Tabu search—part I. ORSA Journal on computing, 1(3), pp.190-206.

- Kirkpatrick, S., 1984. Optimization by simulated annealing: Quantitative studies. Journal of statistical physics, 34(5), pp.975-986.

- Abualigah, L.M.Q. and Hanandeh, E.S., 2015. Applying genetic algorithms to information retrieval using vector space model. International Journal of Computer Science, Engineering and Applications (IJCSEA) Vol, 5.

- Geem, Z.W., Kim, J.H. and Loganathan, G.V., 2001. A new heuristic optimization algorithm: harmony search. simulation, 76(2), pp.60-68.

- Rajabioun, R., 2011. Cuckoo optimization algorithm. Applied soft computing, 11(8), pp.5508-5518.

- Yang, X.S., 2010. Firefly algorithm, stochastic test functions and design optimisation. International journal of bio-inspired computation, 2(2), pp.78-84.

- Dorigo, M. and Di Caro, G., 1999, July. Ant colony optimization: a new meta-heuristic. In Proceedings of the 1999 congress on evolutionary computation-CEC99 (Cat. No. 99TH8406) (Vol. 2, pp. 1470-1477). IEEE.

- Dhiman, G. and Kumar, V., 2017. Spotted hyena optimizer: a novel bio-inspired based metaheuristic technique for engineering applications. Advances in Engineering Software, 114, pp.48-70.

- Yang, X.S., 2010. A new metaheuristic bat-inspired algorithm. In Nature inspired cooperative strategies for optimization (NICSO 2010) (pp. 65-74). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Bolaji, A.L.A., Al-Betar, M.A., Awadallah, M.A., Khader, A.T. and Abualigah, L.M., 2016. A comprehensive review: Krill Herd algorithm (KH) and its applications. Applied Soft Computing, 49, pp.437-446.

- Yang, X.S. and Deb, S., 2009, December. Cuckoo search via Lévy flights. In 2009 World congress on nature & biologically inspired computing (NaBIC) (pp. 210-214). Ieee.

- Karaboga, D., 2005. An idea based on honeybee swarm for numerical optimization (Vol. 200, pp. 1-10). Technical report-tr06, Erciyes university, engineering faculty, computer engineering department.

- Mirjalili, S., 2015. Moth-flame optimization algorithm: A novel nature-inspired heuristic paradigm. Knowledge-based systems, 89, pp.228-249.

- Niu, B. and Wang, H., 2012. Bacterial colony optimization, ‖ Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc, 2012.

- Simon, D., 2008. Biogeography-based optimization. IEEE transactions on evolutionary computation, 12(6), pp.702-713.

- Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S.M. and Lewis, A., 2014. Grey Wolf Optimizer Adv Eng Softw 69: 46–61.

- Mirjalili, S., 2015. The ant lion optimizer. Advances in engineering software, 83, pp.80-98.

- Eberhart, R. and Kennedy, J., 1995, October. A new optimizer using particle swarm theory. In MHS'95. Proceedings of the sixth international symposium on micro machine and human science (pp. 39-43). Ieee.

- Torres-Treviño, L. , 2021. A 2020 taxonomy of algorithms inspired on living beings’ behavior. arXiv:2106.04775.

- Dorigo, M. and Di Caro, G., 1999, July. Ant colony optimization: a new meta-heuristic. In Proceedings of the 1999 congress on evolutionary computation-CEC99 (Cat. No. 99TH8406) (Vol. 2, pp. 1470-1477). IEEE.

- Colorni, A., Dorigo, M. and Maniezzo, V., 1992, September. An Investigation of some Properties of an" Ant Algorithm". In Ppsn (Vol. 92, No. 1992).

- Kumar, V. and Yadav, S.M., 2022. A state-of-the-Art review of heuristic and metaheuristic optimization techniques for the management of water resources. Water Supply, 22(4), pp.3702-3728.

- Tan, J., Melkoumian, N., Harvey, D. and Akmeliawati, R., 2024. Classifying Nature-Inspired Swarm Algorithms for Sustainable Autonomous Mining.

- Jackson, D.E. and Ratnieks, F.L., 2006. Communication in ants. Current biology, 16(15), pp.R570-R574.

- Phan, H.D., Ellis, K., Barca, J.C. and Dorin, A., 2020. A survey of dynamic parameter setting methods for nature-inspired swarm intelligence algorithms. Neural computing and applications, 32(2), pp.567-588.

- Okonta, C.I., Kemp, A.H., Edopkia, R.O., Monyei, G.C. and Okelue, E.D., 2016, August. A heuristic based ant colony optimization algorithm for energy efficient smart homes. In Proc. 5th Int. Conf. Exhib. Clean Energy (pp. 1-12).

- Van Quan, T., Giang, N.H. and Tan, N.N., 2023. A DATA-DRIVEN APPROACH FOR INVESTIGATING SHEAR STRENGTH OF SLENDER STEEL FIBER REINFORCED CONCRETE BEAMS. Journal of Science and Technology in Civil Engineering (JSTCE)-HUCE, 17(2), pp.133-144.

- Yousefi, M., Omid, M., Rafiee, S. and Ghaderi, S.F., 2013. Strategic planning for minimizing CO2 emissions using LP model based on forecasted energy demand by PSO Algorithm and ANN. International Journal of Energy and Environment (Print), 4.

- Khader, A.T., Al-betar, M.A. and Mohammed, A.A., 2013. Artificial bee colony algorithm, its variants and applications: a survey.

- Karaboga, D., 2010. Artificial bee colony algorithm. scholarpedia, 5(3), p.6915.

- Chalotra, S., Sehra, S.K. and Sehra, S.S., 2016, February. A systematic review of applications of bee colony optimization. In 2016 International conference on innovation and challenges in cyber security (ICICCS-INBUSH) (pp. 257-260). IEEE.

- Chao, K.H. and Li, J.Y., 2022. Global maximum power point tracking of photovoltaic module arrays based on improved artificial bee colony algorithm. Electronics, 11(10), p.1572.

- Sharma, T.K., Pant, M. and Singh, V.P., 2012. Improved local search in artificial bee colony using golden section search. arXiv:1210.6128.

- Yang, J. and Peng, Z., 2018. Improved ABC algorithm optimizing the bridge sensor placement. Sensors, 18(7), p.2240.

- Tighzert, L., Fonlupt, C. and Mendil, B., 2018. A set of new compact firefly algorithms. Swarm and evolutionary computation, 40, pp.92-115.

- Sharma, S., Jain, P. and Saxena, A., 2020. Adaptive inertia-weighted firefly algorithm. In Intelligent Computing Techniques for Smart Energy Systems: Proceedings of ICTSES 2018 (pp. 495-503). Springer Singapore.

- Nordin, N., Sulaiman, S.I. and Omar, A.M. (2018) ‘Hybrid artificial neural network with meta-heuristics for grid-connected photovoltaic system output prediction’, Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 11(1), p. 121. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, A., Gálvez, A. and Suárez, P., 2020. Swarm robotics–a case study: bat robotics. In Nature-Inspired Computation and Swarm Intelligence (pp. 273-302). Academic Press.

- Topal, A.O. and Altun, O., 2016. A novel meta-heuristic algorithm: dynamic virtual bats algorithm. Information Sciences, 354, pp.222-235.

- Templos-Santos, J.L., Aguilar-Mejia, O., Peralta-Sanchez, E. and Sosa-Cortez, R., 2019. Parameter tuning of PI control for speed regulation of a PMSM using bio-inspired algorithms. Algorithms, 12(3), p.54.

- Gandomi, A.H. and Alavi, A.H., 2012. Krill herd: a new bio-inspired optimization algorithm. Communications in nonlinear science and numerical simulation, 17(12), pp.4831-4845.

- Wang, G.G., Gandomi, A.H., Alavi, A.H. and Gong, D., 2019. A comprehensive review of krill herd algorithm: variants, hybrids and applications. Artificial Intelligence Review, 51, pp.119-148.

- Ren, Y.T., Qi, H., Huang, X., Wang, W., Ruan, L.M. and Tan, H.P., 2016. Application of improved krill herd algorithms to inverse radiation problems. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 103, pp.24-34.

- Regad, M., Helaimi, M.H., Taleb, R., Othman, A.M. and Gabbar, H.A., 2020. Frequency control of microgrid with renewable generation using PID controller based krill herd. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Informatics (IJEEI), 8(1), pp.21-32.

- Faris, H., Aljarah, I., Al-Betar, M.A. and Mirjalili, S., 2018. Grey wolf optimizer: a review of recent variants and applications. Neural computing and applications, 30, pp.413-435.

- Guha, D., Roy, P.K. and Banerjee, S., 2016. Load frequency control of large scale power system using quasi-oppositional grey wolf optimization algorithm. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, 19(4), pp.1693-1713.

- Zhang, J., Wang, Z. and Luo, X., 2018. Parameter estimation for soil water retention curve using the salp swarm algorithm. Water, 10(6), p.815.

- Saremi, S., Mirjalili, S. and Lewis, A., 2017. Grasshopper optimisation algorithm: theory and application. Advances in engineering software, 105, pp.30-47.

- Meraihi, Y., Gabis, A.B., Mirjalili, S. and Ramdane-Cherif, A., 2021. Grasshopper optimization algorithm: theory, variants, and applications. IEEE Access, 9, pp.50001-50024.

- Abualigah, L. and Diabat, A., 2020. A comprehensive survey of the Grasshopper optimization algorithm: results, variants, and applications. Neural Computing and Applications, 32(19), pp.15533-15556.

- Nabavi, S., Gholampour, S. and Haji, M.S., 2022. Damage detection in frame elements using Grasshopper Optimization Algorithm (GOA) and time-domain responses of the structure. Evolving Systems, 13(2), pp.307-318.

- Tan, Y. and Zheng, Z.Y., 2013. Research advance in swarm robotics. Defence Technology, 9(1), pp.18-39.

- Fong, T., Nourbakhsh, I. and Dautenhahn, K., 2003. A survey of socially interactive robots. Robotics and autonomous systems, 42(3-4), pp.143-166.

- Blum, C. and Merkle, D. eds., 2008. Swarm intelligence: introduction and applications. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Szabó, L., Káptalan, E. and Szász, C., 2011. Applications of Collective Behavior Concepts in Flexible Manufacturing Systems. Journal of Computer Science and Control Systems, 4(1), p.187.

- Majid, M.H.A., Arshad, M.R. and Mokhtar, R.M., 2022. Swarm robotics behaviors and tasks: a technical review. Control engineering in robotics and industrial automation: Malaysian society for automatic control engineers (MACE) technical series 2018, pp.99-167.

- Mariappan, M., Arshad, M.R., Akmeliawati, R. and Chong, C.S., 2022. Control Engineering in Robotics and Industrial Automation.

- Novischi, D.M. and Florea, A.M., 2013, October. Toward a real-time heterogeneous mobile robotic swarm: Robot platform and agent architecture. In 2013 17th International Conference on System Theory, Control and Computing (ICSTCC) (pp. 772-776). IEEE.

- Dorigo, M., Floreano, D., Gambardella, L.M., Mondada, F., Nolfi, S., Baaboura, T., Birattari, M., Bonani, M., Brambilla, M., Brutschy, A. and Burnier, D., 2013. Swarmanoid: a novel concept for the study of heterogeneous robotic swarms. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, 20(4), pp.60-71.

- Kayser, M., Cai, L., Bader, C., Falcone, S., Inglessis, N., Darweesh, B., Costa, J. and Oxman, N., 2018, September. Fiberbots: design and digital fabrication of tubular structures using robot swarms. In Robotic Fabrication in Architecture, Art and Design (pp. 285-296). Springer, Cham.

- Petersen, K.H., Nagpal, R. and Werfel, J.K., 2011. Termes: An autonomous robotic system for three-dimensional collective construction. Robotics: science and systems VII.

- Phys.org. 2018. Nature-inspired soft millirobot makes its way through enclosed spaces. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2018-01-nature-inspired-soft-millirobot-enclosed-spaces.html (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Trianni, V., IJsselmuiden, J. and Haken, R., 2016. The Saga Concept: Swarm Robotics for Agricultural Applications. Technical Report. 2016. Available online: http://laral. istc. cnr. it/saga/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sagadars2016. pdf (accessed on 23 August 2018).

- Kshetri, N. and Rojas-Torres, D., 2018. The 2018 winter olympics: A showcase of technological advancement. IT Prof., 20(2), pp.19-25.

- Navarro, I. and Matía, F., 2013. An introduction to swarm robotics. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2013(1), p.608164.

- BRAMBILLA, D., 2014. Environment classification: an empirical study of the response of a robot swarm to three different decision-making rules.

- Trianni, V. and Campo, A., 2015. Fundamental collective behaviors in swarm robotics. Springer handbook of computational intelligence, pp.1377-1394.

- Bayındır, L., 2016. A review of swarm robotics tasks. Neurocomputing, 172, pp.292-321.

- Mendonça, M., Chrun, I.R., Neves Jr, F. and Arruda, L.V., 2017. A cooperative architecture for swarm robotic based on dynamic fuzzy cognitive maps. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 59, pp.122-132.

- Connor, J., Champion, B. and Joordens, M.A., 2020. Current algorithms, communication methods and designs for underwater swarm robotics: A review. IEEE Sensors Journal, 21(1), pp.153-169.

- Duflo, G., Danoy, G., Talbi, E.G. and Bouvry, P., 2022. Learning to Optimise a Swarm of UAVs. Applied Sciences, 12(19), p.9587.

- Duan, H., Huo, M. and Fan, Y., 2023. From animal collective behaviors to swarm robotic cooperation. National Science Review, 10(5), p.nwad040.

- Ibrahim, R., Alkilabi, M., Khayeat, A.R.H. and Tuci, E., 2024. Review of Collective Decision Making in Swarm Robotics. Journal of Al-Qadisiyah for Computer Science and Mathematics, 16(1), pp.72-80.

- Mansouri, S.S., Kanellakis, C., Kominiak, D. and Nikolakopoulos, G., 2020. Deploying MAVs for autonomous navigation in dark underground mine environments. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 126, p.103472.

- Lerman, K., Martinoli, A. and Galstyan, A., 2005. A review of probabilistic macroscopic models for swarm robotic systems. In Swarm Robotics: SAB 2004 International Workshop, Santa Monica, CA, USA, July 17, 2004, Revised Selected Papers 1 (pp. 143-152). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- De La Cruz, C. and Carelli, R., 2006, November. Dynamic modeling and centralized formation control of mobile robots. In IECON 2006-32nd annual conference on IEEE industrial electronics (pp. 3880-3885). IEEE.

- Mehrjerdi, H., Saad, M. and Ghommam, J., 2010. Hierarchical fuzzy cooperative control and path following for a team of mobile robots. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, 16(5), pp.907-917.

- Kamel, M.A., Yu, X. and Zhang, Y., 2020. Formation control and coordination of multiple unmanned ground vehicles in normal and faulty situations: A review. Annual reviews in control, 49, pp.128-144.

- Dorigo, M., Theraulaz, G. and Trianni, V., 2021. Swarm robotics: Past, present, and future [point of view]. Proceedings of the IEEE, 109(7), pp.1152-1165.

- Kambayashi, Y., Yajima, H., Shyoji, T., Oikawa, R. and Takimoto, M., 2019. Formation control of swarm robots using mobile agents. Vietnam Journal of Computer Science, 6(02), pp.193-222.

- Stolfi, D.H. and Danoy, G., 2024. Evolutionary swarm formation: From simulations to real world robots. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 128, p.107501.

- Lu, S., Samaan, N., Diao, R., Elizondo, M., Jin, C., Mayhorn, E., Zhang, Y. and Kirkham, H., 2011, January. Centralized and decentralized control for demand response. In ISGT 2011 (pp. 1-8). Ieee.

- Jamshidpey, A., Wahby, M., Heinrich, M.K., Allwright, M., Zhu, W. and Dorigo, M., 2024. Centralization vs. decentralization in multi-robot coverage: Ground robots under uav supervision. arXiv:2408.06553.

- Garattoni, L., Birattari, M. and Webster, J.G., 2016. Swarm robotics. Wiley encyclopedia of electrical and electronics engineering, 10.

- Lewis, M.A. and Tan, K.H., 1997. High precision formation control of mobile robots using virtual structures. Autonomous robots, 4(4), pp.387-403.

- Balch, T. and Arkin, R.C., 1998. Behavior-based formation control for multirobot teams. IEEE transactions on robotics and automation, 14(6), pp.926-939.

- Desai Jaydev, P. and Ostrowski James, P., 2001. Kumar Vijay. Modeling and control of formations of nonholonomic mobile robots, Robotics and Automation, IEEE Transactions on, 17(6), pp.905-908.

- Lei, T., Sellers, T., Luo, C., Carruth, D.W. and Bi, Z., 2023. Graph-based robot optimal path planning with bio-inspired algorithms. Biomimetic Intelligence and Robotics, 3(3), p.100119.

- Desai, J.P., Ostrowski, J. and Kumar, V., 1998, May. Controlling formations of multiple mobile robots. In Proceedings. 1998 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No. 98CH36146) (Vol. 4, pp. 2864-2869). IEEE.

- Khatib, O., 1986. Real-time obstacle avoidance for manipulators and mobile robots. In Autonomous robot vehicles (pp. 396-404). Springer, New York, NY.

- Lawton, J.R., Beard, R.W. and Young, B.J., 2003. A decentralized approach to formation maneuvers. IEEE transactions on robotics and automation, 19(6), pp.933-941.

- Nhleko, A.S. and Musingwini, C., 2019. Analysis of the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm for application in stope layout optimisation for underground mines. In Proceedings of the Mine Planner’s Colloquium.

- Jafrasteh, B. and Fathianpour, N., 2017. Optimal location of additional exploratory drillholes using afuzzy-artificial bee colony algorithm. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 10, pp.1-16.

- Saremi, S., Mirjalili, S. and Lewis, A., 2017. Grasshopper optimisation algorithm: theory and application. Advances in engineering software, 105, pp.30-47.

- Mohammadzadeh, M., Mahboubiaghdam, M., Nasseri, A. and Jahangiri, M., 2023. A New Frontier in Mineral Exploration: Hybrid Machine Learning and Bat Metaheuristic Algorithm for Cu-Au Mineral Prospecting in Sonajil area, E-Azerbaijan.

- Korzeń, M. and Kruszyna, M., 2023. Modified Ant Colony Optimization as a Means for Evaluating the Variants of the City Railway Underground Section. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), p.4960.

- Sattarvand, J., 2012. Long-term open-pit planning by ant colony optimization (Doctoral dissertation, Aachen, Techn. Hochsch., Diss., 2009).

- Gilani, S.O. and Sattarvand, J., 2016. Integrating geological uncertainty in long-term open pit mine production planning by ant colony optimization. Computers & Geosciences, 87, pp.31-40.

- Shishvan, M.S. and Sattarvand, J., 2015. Long term production planning of open pit mines by ant colony optimization. European Journal of Operational Research, 240(3), pp.825-836.

- Khan, A. and Niemann-Delius, C., 2014, September. Application of particle swarm optimization to the open pit mine scheduling problem. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium Continuous Surface Mining-Aachen 2014 (pp. 195-212). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Ferland, J., Amaya, J. and Djuimo, M.S., 2007. Particle swarm procedure for the capacitated open pit mining problem. Autonomous Robot and Agents. Studies in Computational Intelligence, Book Series, Springer Verlag.

- Khan, A., 2018. Long-term production scheduling of open pit mines using particle swarm and bat algorithms under grade uncertainty. Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 118(4), pp.361-368.

- Tolouei, K. and Moosavi, E., 2020. Production scheduling problem and solver improvement via integration of the grey wolf optimizer into the augmented Lagrangian relaxation method. SN Applied Sciences, 2(12), p.1963.

- Ghaziania, H.H., Monjezi, M., Mousavi, A., Dehghani, H. and Bakhtavar, E., 2021. Design of loading and transportation fleet in open-pit mines using simulation approach and metaheuristic algorithms. Journal of Mining and Environment, 12(4), pp.1177-1188.

- Bao, H. and Zhang, R., 2020. Study on Optimization of Coal Truck Flow in Open-Pit Mine. Advances in Civil Engineering, 2020(1), p.8848140.

- Nguyen, H., Bui, X.N. and Topal, E., 2023. Reliability and availability artificial intelligence models for predicting blast-induced ground vibration intensity in open-pit mines to ensure the safety of the surroundings. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 231, p.109032.

- Yan, G. and Feng, D., 2013. Escape-Route Planning of Underground Coal Mine Based on Improved Ant Algorithm. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2013(1), p.687969.

- Li, X., Li, Y., Zhang, Y., Liu, F. and Fang, Y., 2020. Fault diagnosis of belt conveyor based on support vector machine and grey wolf optimization. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2020(1), p.1367078.

- Liu, Y., Lin, J. and Yue, H., 2023. Soil respiration estimation in desertified mining areas based on UAV remote sensing and machine learning. Earth Science Informatics, 16(4), pp.3433-3448.

- Trueman, E.R., 1967. The dynamics of burrowing in Ensis (Bivalvia). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences, 166(1005), pp.459-476.

- Winter, A.G., Hosoi, A.E., Slocum, A.H. and Deits, R.L., 2009, January. The design and testing of RoboClam: A machine used to investigate and optimize razor clam-inspired burrowing mechanisms for engineering applications. In International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (Vol. 49040, pp. 721-726).

- Winter, A.G. and Hosoi, A.E., 2011. Identification and evaluation of the Atlantic razor clam (Ensis directus) for biologically inspired subsea burrowing systems.

- Winter, A.G., Deits, R.L. and Dorsch, D.S., 2013, August. Critical timescales for burrowing in undersea substrates via localized fluidization, demonstrated by RoboClam: a robot inspired by Atlantic razor clams. In International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (Vol. 55935, p. V06AT07A007). American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- Winter, A.G., Deits, R.L.H., Dorsch, D.S., Slocum, A.H. and Hosoi, A.E., 2014. Razor clam to RoboClam: burrowing drag reduction mechanisms and their robotic adaptation. Bioinspiration & biomimetics, 9(3), p.036009.

- Isava, M., 2015. An investigation of the critical timescales needed for digging in wet and dry soil using a biomimetic burrowing robot (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

- Isava, M., 2016. Razor clam-inspired burrowing in dry soil. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics, 81, pp.30-39.

- Wei, H., Zhang, Y., Zhang, T., Guan, Y., Xu, K., Ding, X. and Pang, Y., 2021. Review on bioinspired planetary regolith-burrowing robots. Space Science Reviews, 217, pp.1-39.

- Koller-hodac et al., “Actuated Bivalve Robot Study of the Burrowing Locomotion in Sediment,” in IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2010, pp. 1209–1214.

- Lopes, L., Bodo, B., Rossi, C., Henley, S., Žibret, G., Kot-Niewiadomska, A. and Correia, V., 2020. ROBOMINERS–Developing a bio-inspired modular robot-miner for difficult to access mineral deposits. Advances in Geosciences, 54, pp.99-108.

- Gomez, V., Hernando, M., Aguado, E., Sanz, R. and Rossi, C., 2023. Robominer: Development of a highly configurable and modular scaled-down prototype of a mining robot. Machines, 11(8), p.809.

- Berner, M. and Sifferlinger, N.A., 2024. H2020-ROBOMINERS Prototype Field Test. BHM Berg-und Hüttenmännische Monatshefte, 169(4), pp.197-198.

- Russell, R.A., 2011. CRABOT: A biomimetic burrowing robot designed for underground chemical source location. Advanced Robotics, 25(1-2), pp.119-134.

- Kim, J., Jang, H.W., Shin, J.U., Hong, J.W. and Myung, H., 2018. Development of a mole-like drilling robot system for shallow drilling. IEEE Access, 6, pp.76454-76463.

- Kobayashi, T., Tshukagoshi, H., Honda, S. and Kitagawa, A., 2011. Burrowing rescue robot referring to a mole’s shoveling motion. In Proceedings of the 8th JFPS international symposium on fluid power (pp. 644-649).

- Lee, J., Lim, H., Song, S. and Myung, H., 2019, November. Concept design for mole-like excavate robot and its localization method. In 2019 7th International Conference on Robot Intelligence Technology and Applications (RiTA) (pp. 56-60). IEEE.

- Lee, J., Tirtawardhana, C. and Myung, H., 2020, October. Development and analysis of digging and soil removing mechanisms for mole-bot: Bio-inspired mole-like drilling robot. In 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) (pp. 7792-7799). IEEE.

- Chen, Z., Liang, Z., Zheng, K., Zheng, H., Zhu, H., Guan, Y., Xu, K. and Zhang, T., 2024, August. Mechanism Design of a Mole-inspired Robot Burrowing with Forelimb for Planetary Exploration. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA) (pp. 982-987). IEEE.

- Yuan, Z., Mu, R., Yang, J., Wang, K. and Zhao, H., 2022, June. Modeling of Autonomous Burrowing Mole-type Robot Drilling into Lunar Regolith. In 2022 International Conference on Service Robotics (ICoSR) (pp. 113-117). IEEE.

- Yuan, Z., Mu, R., Zhao, H. and Wang, K., 2023. Predictive model of a mole-type burrowing robot for lunar subsurface exploration. Aerospace, 10(2), p.190.

- Yuan, Z. and Zhao, H., 2023, June. Towards Ultra-Deep Exploration in the Moon: Modeling and Implementation of a Mole-Type Burrowing System. In ARMA US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium (pp. ARMA-2023). ARMA.

- Zhang, P., Chen, J., Xia, H., Li, Z., Lin, X. and Zhou, P., 2024. Development and Motion Mechanism of a Novel Underwater Exploration Robot for Stratum Drilling. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering.

- Simi, A., Pasculli, D. and Manacorda, G., 2019, September. Badger project: GPR system design on board on a underground drilling robot. In 10th International Workshop on Advanced Ground Penetrating Radar (Vol. 2019, No. 1, pp. 1-9). European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers.

- Vartholomeos, P., Marantos, P., Karras, G., Menendez, E., Rodriguez, M., Martinez, S. and Balaguer, C., 2021. Modeling, gait sequence design, and control architecture of BADGER underground robot. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 6(2), pp.1160-1167.

- Zhang, W., Jiang, S., Tang, D., Chen, H. and Liang, J., 2017. Drilling load model of an inchworm boring robot for lunar subsurface exploration. International Journal of Aerospace Engineering, 2017(1), p.1282791.

- Zhang, W., Li, L., Jiang, S., Ji, J. and Deng, Z., 2019. Inchworm drilling system for planetary subsurface exploration. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, 25(2), pp.837-847.

- Dorgan, K.M., 2015. The biomechanics of burrowing and boring. Journal of Experimental Biology, 218(2), pp.176-183.

- Winter, A.G., Deits, R.L., Dorsch, D.S., Hosoi, A.E. and Slocum, A.H., 2010, October. Teaching roboclam to dig: The design, testing, and genetic algorithm optimization of a biomimetic robot. In 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (pp. 4231-4235). IEEE.

- Isaka, K., Tsumura, K., Watanabe, T., Toyama, W., Sugesawa, M., Yamada, Y., Yoshida, H. and Nakamura, T., 2019. Development of underwater drilling robot based on earthworm locomotion. Ieee Access, 7, pp.103127-103141.

- Wang, W., Lee, J.Y., Rodrigue, H., Song, S.H., Chu, W.S. and Ahn, S.H., 2014. Locomotion of inchworm-inspired robot made of smart soft composite (SSC). Bioinspiration & biomimetics, 9(4), p.046006.

- Gomez, V., Remmas, W., Hernando, M., Ristolainen, A. and Rossi, C., 2024. Bioinspired Whisker sensor for 3D mapping of underground mining environments. Biomimetics, 9(2), p.83.

- Hou, X., Xin, L., Fu, Y., Na, Z., Gao, G., Liu, Y., Xu, Q., Zhao, P., Yan, G., Su, Y. and Cao, K., 2023. A self-powered biomimetic mouse whisker sensor (BMWS) aiming at terrestrial and space objects perception. Nano Energy, 118, p.109034.

- Kossas, T., Remmas, W., Gkliva, R., Ristolainen, A. and Kruusmaa, M., 2024, May. Whisker-based tactile navigation algorithm for underground robots. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) (pp. 13164-13170). IEEE.

- Western, A., Haghshenas-Jaryani, M. and Hassanalian, M., 2023. Golden wheel spider-inspired rolling robots for planetary exploration. Acta Astronautica, 204, pp.34-48.

- Yazıcı, A.M., 2021. Bio-inspired Robotics For Space Research. Havacılık ve Uzay Çalışmaları Dergisi, 1(2), pp.64-77.

- Trianni, V., IJsselmuiden, J. and Haken, R., 2016. The saga concept: swarm robotics for agricultural applications. Technical Report. 2016. Available online: http://laral. istc. cnr. it/saga/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sagadars2016. pdf (accessed on 23 August 2018).

- Phys.org. 2018. Nature-inspired soft millirobot makes its way through enclosed spaces. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2018-01-nature-inspired-soft-millirobot-enclosed-spaces.html (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Kayser, M., Cai, L., Bader, C., Falcone, S., Inglessis, N., Darweesh, B., Costa, J. and Oxman, N., 2018, September. Fiberbots: design and digital fabrication of tubular structures using robot swarms. In Robotic Fabrication in Architecture, Art and Design (pp. 285-296). Springer, Cham.

- Petersen, K.H., Nagpal, R. and Werfel, J.K., 2011. Termes: An autonomous robotic system for three-dimensional collective construction. Robotics: science and systems VII.

- Bearne, G., 2014. Innovation in mining: Rio Tinto's Mine of the Future (TM) programme. Aluminium International Today, 26(3), p.15.

- Ellem, B., 2015. Resource peripheries and neoliberalism: The Pilbara and the remaking of industrial relations in Australia. Australian Geographer, 46(3), pp.323-337.

- Tinto, R., 2015. Rio Tinto. MarketLine Company Profile, pp.1-36.

- Government of Western Australia., 2019. Western Australia Iron Ore Profile 2019.

- BHP., 2019. Automation data is making work safer, smarter and faster.

- Salisbury, C., 2018. Iron Ore–Delivering value from flexibility and optionality. London, UK: Rio Tinto.

- Jang, H. and Topal, E., 2020. Transformation of the Australian mining industry and future prospects. Mining Technology, 129(3), pp.120-134.

- Leonida, C., 2022. Introducing Autonomy 2.0. Engineering and Mining Journal, 223(12), pp.26-30.

- Kottege, N., Williams, J., Tidd, B., Talbot, F., Steindl, R., Cox, M., Frousheger, D., Hines, T., Pitt, A., Tam, B. and Wood, B., 2023. Heterogeneous robot teams with unified perception and autonomy: How Team CSIRO Data61 tied for the top score at the DARPA Subterranean Challenge. arXiv:2302.13230.

- Vallejos, C.A.C., 2019. Structural recognition and rock mass characterisation in underground mines: A UAV And LiDAR Mapping Based Approach (Doctoral dissertation, MSc thesis, Universidad De Concepción, Concepción).

- Jones, E., Sofonia, J., Canales, C., Hrabar, S. and Kendoul, F., 2019, June. Advances and applications for automated drones in underground mining operations. In Deep mining 2019: Proceedings of the ninth international conference on deep and high stress mining (pp. 323-334). The Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy.

- Baylis, C.N.C., Kewe, D.R., Jones, E.W. and Wesseloo, J., 2020, November. Mobile drone LiDAR structural data collection and analysis. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Underground Mining Technology, Australian Centre for Geomechanics, Perth (pp. 325-334).

- Woolmer, D., Jones, E., Taylor, J., Baylis, C. and Kewe, D., 2020, December. Use of Drone based Lidar technology at Olympic Dam Mine and initial Technical Applications. In MassMin 2020: Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference & Exhibition on Mass Mining (pp. 565-582). University of Chile.

- Gustafsson, C., 2023. Evaluation of SLAM based mobile laser scanning and terrestrial laser scanning in the Kiruna mine: A comparison between the Emesent Hovermap HF1 mobile laser scanner and the Faro Laser Scanner Focus3D X 330 terrestrial laser scanner.

- Lozano Bravo, H., Lo, E., Moyes, H., Rissolo, D., Montgomery, S. and Kuester, F., 2023. a Methodology for Cave Floor Basemap Synthesis from Point Cloud Data: a Case Study of Slam-Based LIDAR at Las Cuevas, Belize. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, pp.179-186.

- Carter, R.A., 2019. Over, Under, Sideways, Down. Engineering and Mining Journal, 220(12), pp.66-71.

- Brown, L., Clarke, R., Akbari, A., Bhandari, U., Bernardini, S., Chhabra, P., Marjanovic, O., Richardson, T. and Watson, S., 2020. The design of prometheus: A reconfigurable uav for subterranean mine inspection. robotics, 9(4), p.95.

- Extance, A., 2019. Optical sensor drones fly into danger: Powered predominantly by lidar, plus spectroscopy and visual-wavelength imaging, Andy Extance discovers unmanned aerial vehicles can safely survey hazardous environments. Electro Optics, (292), pp.18-23.

- Mueller, R.P. and Van Susante, P.J., 2012. A review of extra-terrestrial mining robot concepts. Earth and Space 2012: Engineering, Science, Construction, and Operations in Challenging Environments, pp.295-314.

- du Venage, G., 2018. Thousands gather at Electra. Engineering and Mining Journal, 219(10), pp.70-73.

- Nguyen, H.A. and Ha, Q.P., 2023. Robotic autonomous systems for earthmoving equipment operating in volatile conditions and teaming capacity: a survey. Robotica, 41(2), pp.486-510.

- Lopes, L., Zajzon, N., Bodo, B., Henley, S., Žibret, G. and Dizdarevic, T., 2017. UNEXMIN: Developing an autonomous underwater explorer for flooded mines. Energy Procedia, 125, pp.41-49.

- Lopes, L., Zajzon, N., Henley, S., Vörös, C., Martins, A. and Almeida, J.M., 2017. UNEXMIN: a new concept to sustainably obtain geological information from flooded mines. European Geologist, 44, pp.54-57.

- Martins, A., Almeida, J., Almeida, C., Dias, A., Dias, N., Aaltonen, J., Heininen, A., Koskinen, K.T., Rossi, C., Dominguez, S. and Vörös, C., 2018, October. UX 1 system design-A robotic system for underwater mining exploration. In 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) (pp. 1494-1500). IEEE.

- Almeida, J.M., Martins, A., Viegas, D., Ferreira, A., Matias, B., Sytnyk, D., Soares, E. and Pereira, R., 2023. Underwater Robotics: Sustainable Prospecting and Exploitation of Raw Materials. INESC TEC Science&Society, 1(6).

- Clausen, E. and Sörensen, A., 2022. Required and desired: breakthroughs for future-proofing mineral and metal extraction. Mineral Economics, 35(3), pp.521-537.

- Alvarenga, C.D., Castellon, J.S.G., Hermosillo, J.M.G., Mann, N., Meraz, M., Nho, J., Salcedo, J. and Carpin, S., NASA Swarmathon 2017.

- Ackerman, S.M., Fricke, G.M., Hecker, J.P., Hamed, K.M., Fowler, S.R., Griego, A.D., Jones, J.C., Nichol, J.J., Leucht, K.W. and Moses, M.E., 2018. The swarmathon: An autonomous swarm robotics competition. arXiv:1805.08320.

- Nguyen, L.A., Harman, T.L. and Fairchild, C., 2019, September. Swarmathon: a swarm robotics experiment for future space exploration. In 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Measurement and Control in Robotics (ISMCR) (pp. B1-3). IEEE.

- Mueller, R.P., Cox, R.E., Ebert, T., Smith, J.D., Schuler, J.M. and Nick, A.J., 2013, March. Regolith advanced surface systems operations robot (RASSOR). In 2013 IEEE Aerospace Conference (pp. 1-12). IEEE.

- Mueller, R.P., Smith, J.D., Schuler, J.M., Nick, A.J., Gelino, N.J., Leucht, K.W., Townsend, I.I. and Dokos, A.G., 2016, April. Design of an excavation robot: regolith advanced surface systems operations robot (RASSOR) 2.0. In 15th Biennial ASCE Conference on Engineering, Science, Construction, and Operations in Challenging Environments (pp. 163-174). Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers.

- NASA. (n.d.). Regolith Advanced Surface Systems Operations Robot (RASSOR) Excavator (KSC-TOPS-7). NASA Technology Transfer Program. Available from https://technology.nasa.gov/patent/KSC-TOPS-7.

- Tan, J., Melkoumian, N., Harvey, D. and Akmeliawati, R., 2024. LUNARMINERS: Lunar Mining for Water-Ice Etraction by Implementing Nature-Inspired Behavior in Robotic Swarms.

- Schmickl, T. and Hamann, H., 2011. BEECLUST: A swarm algorithm derived from honeybees. Bio-inspired computing and communication networks, pp.95-137.

- Wahby, M., Weinhold, A. and Hamann, H., 2016. Revisiting BEECLUST: Aggregation of swarm robots with adaptiveness to different light settings. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Collaborative Computing, 2(9), pp.272-279.

- Jayadeva, Shah, S., Bhaya, A., Kothari, R. and Chandra, S., 2013. Ants find the shortest path: a mathematical proof. Swarm Intelligence, 7, pp.43-62.

- Głąbowski, M., Musznicki, B., Nowak, P. and Zwierzykowski, P., 2014. An algorithm for finding shortest path tree using ant colony optimization metaheuristic. In Image Processing and Communications Challenges 5 (pp. 317-326). Springer International Publishing.

- Ok, S.H., Seo, W.J., Ahn, J.H., Kang, S. and Moon, B., 2009. An ant colony optimization approach for the preference-based shortest path search. In Communication and Networking: International Conference, FGCN/ACN 2009, Held as Part of the Future Generation Information Technology Conference, FGIT 2009, Jeju Island, Korea, December 10-12, 2009. Proceedings (pp. 539-546). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Vittori, K., Talbot, G., Gautrais, J., Fourcassié, V., Araújo, A.F. and Theraulaz, G., 2006. Path efficiency of ant foraging trails in an artificial network. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 239(4), pp.507-515.

- Bandyopadhyay, L.K., Chaulya, S.K. and Mishra, P.K., 2010. Wireless communication in underground mines. RFID-Based Sens. Netw, 22.

- Yarkan, S., Guzelgoz, S., Arslan, H. and Murphy, R.R., 2009. Underground mine communications: A survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 11(3), pp.125-142.

- Forooshani, A.E., Bashir, S., Michelson, D.G. and Noghanian, S., 2013. A survey of wireless communications and propagation modeling in underground mines. IEEE Communications surveys & tutorials, 15(4), pp.1524-1545.

- Cao, L., Cai, Y. and Yue, Y., 2019. Swarm intelligence-based performance optimization for mobile wireless sensor networks: survey, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access, 7, pp.161524-161553.

- Carrillo, M., Gallardo, I., Del Ser, J., Osaba, E., Sanchez-Cubillo, J., Bilbao, M.N., Gálvez, A. and Iglesias, A., 2018. A bio-inspired approach for collaborative exploration with mobile battery recharging in swarm robotics. In Bioinspired Optimization Methods and Their Applications: 8th International Conference, BIOMA 2018, Paris, France, May 16-18, 2018, Proceedings 8 (pp. 75-87). Springer International Publishing.

- Harvey, D.J., 2007. An investigation into insect chemical plume tracking using a mobile robot (Doctoral dissertation).

| Algorithms | Mining Applications | Mining Optimization | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSO | Exploration | Improves stope identification, enhances block scheduling, reduces truck counts, shortens wait times, increases productivity (up to 52.24% profit gains), enhances mapping accuracy (97.22%), fault detection, and environmental variable analysis (R2 = 0.959) | [123,126,132,136,139,140] |

| Mine Planning | |||

| Logistics Optimization Safety and Risk Management Environmental Monitoring | |||

| ABC | Exploration | Lowers kriging variance, increases accuracy of mineral estimation | [124] |

| Resource Management | |||

| GOA | Exploration | Improves effectiveness of mineral zone identification | [125] |

| Resource Management | |||

| BA | Exploration | Increases mineralization mapping accuracy (94.3%), reduces exploration disturbances, enhances fault detection accuracy (97.22%) | [126,139] |

| Environmental Sustainability Safety and Risk Management | |||

| ACO | Mine Planning Safety and Risk Management |

Enhances route planning, integrates geological uncertainty, improves escape routes, increases NPV by up to 21.1%, improves long-term production planning, increasing NPV by 2.58% | [127,128,129,130,138] |

| GWO | Mine Planning Safety and Risk Management |

Increases long-term scheduling NPV by 13.39%, enhances fault detection accuracy (97.22%) | [134,139] |

| FA | Logistics Optimization |

Reduces idle time, improves equipment scheduling (20% productivity gain) | [135] |

| SSA | Safety and Risk Management | Improves blasting safety, predicts ground vibrations with 90.5% accuracy | [137] |

| Bio-Inspiration | Robots | Bio-inspired Mechanism | Mining Applications | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic Razor Clam | RoboClam | Contracts its valves to fluidize soil and reduce drag. |

|

[141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148] |

| Bivalve | Actuated Bivalve Robot | Uses a rocking motion and water expulsion to fluidize sediment. |

|

[148,149] |

| Mole Crickets, Termites, Centipedes | Robot-miner | Dig, navigate and excavate autonomously without GPS. |

|

[150,151,152] |

| Mole crab | CRABOT | Mimics burrowing motion with power and recovery strokes; uses a uropod-like appendage to improve excavation efficiency by 50%. |

|

[148,153] |

| Mole | Mole-like Drilling Robot | Uses incisors to brace and push soil out of holes. |

|

[148,154] |

| Burrowing Rescue Robot | Shovelling motion with two arms and palms to push aside soil and steer itself. |

|

[148,155] | |

| Mole-Bot | Expandable drill bit mimicking the teeth and forelimbs of a mole for digging habit. |

|

[156,157,158] | |

| Earthworm | Stratloong | Peristaltic motion mimicking anchoring and extending motions to penetrate soil. |

|

[148,162] |

| Inchworm | BADGER | Sequential extension and contraction mimicking anchoring and forward pushing. |

|

[162,163,164] |

| NASA Inchworm Robot | [165,166] | |||

| Naked Mole Rat | Robotic Miner with Whisker Sensors | Mimics the tactile whisker sensing of naked mole rats. |

|

[171] |

| Mouse | Biomimetic Whisker Sensor (BMWS) | Mimics mouse whiskers for object and contour detection. |

|

[172] |

| Rodents | RM3 Robot | Mimics the whisker sensing of rodents. |

|

[173] |

| Golden Wheel Spider | Spider Rolling Robot (SRR) | Wind-assisted rolling motion to traverse rough surfaces efficiently. |

|

[174] |

| Robot / System | Project / Company | Mining Application | Mining Applications | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous Haulage System (AHS) | Rio Tinto | Autonomous haulage trucks for transporting ore teleoperated. |

|

Operational | [180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187] |

| Hovermap | Emesent | Autonomous drone for 3D mapping in underground mines. |

|

Operational | [188,189,190,191,192,193,194] |

| Exyn A3R | Exyn Technologies | Autonomous drone for 3D mapping in underground mines. |

|

Operational | [195,196,197] |

| AutoMine system | Sandvik | Autonomous trucks and loaders teleremote. |

|

Operational | [198,199,200] |

| UX-1 | UNEXMIN project | Autonomous robot for exploring and mapping flooded underground mines. |

|

Research & development | [201,202] |

| NEXGEN SIMS Autonomous Robots | Epiroc project | Autonomous electric robots for mine transportation, drilling and inspection |

|

Research & development | [205] |

| Swarmies | NASA’s Swarmathon Competition | Autonomous robots for resource collection simulating Mars missions for ISRU. |

|

Research & development | [206,207,208] |

| RASSOR* (*updated name: IPEx) | NASA | Autonomous robot for regolith excavation and processing on the Moon and Mars |

|

Research & development | [209,210,211,212] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).