Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. International Human Mobility

1.2. Brain Drainage, Gain, and Circulation

2. Literature Review

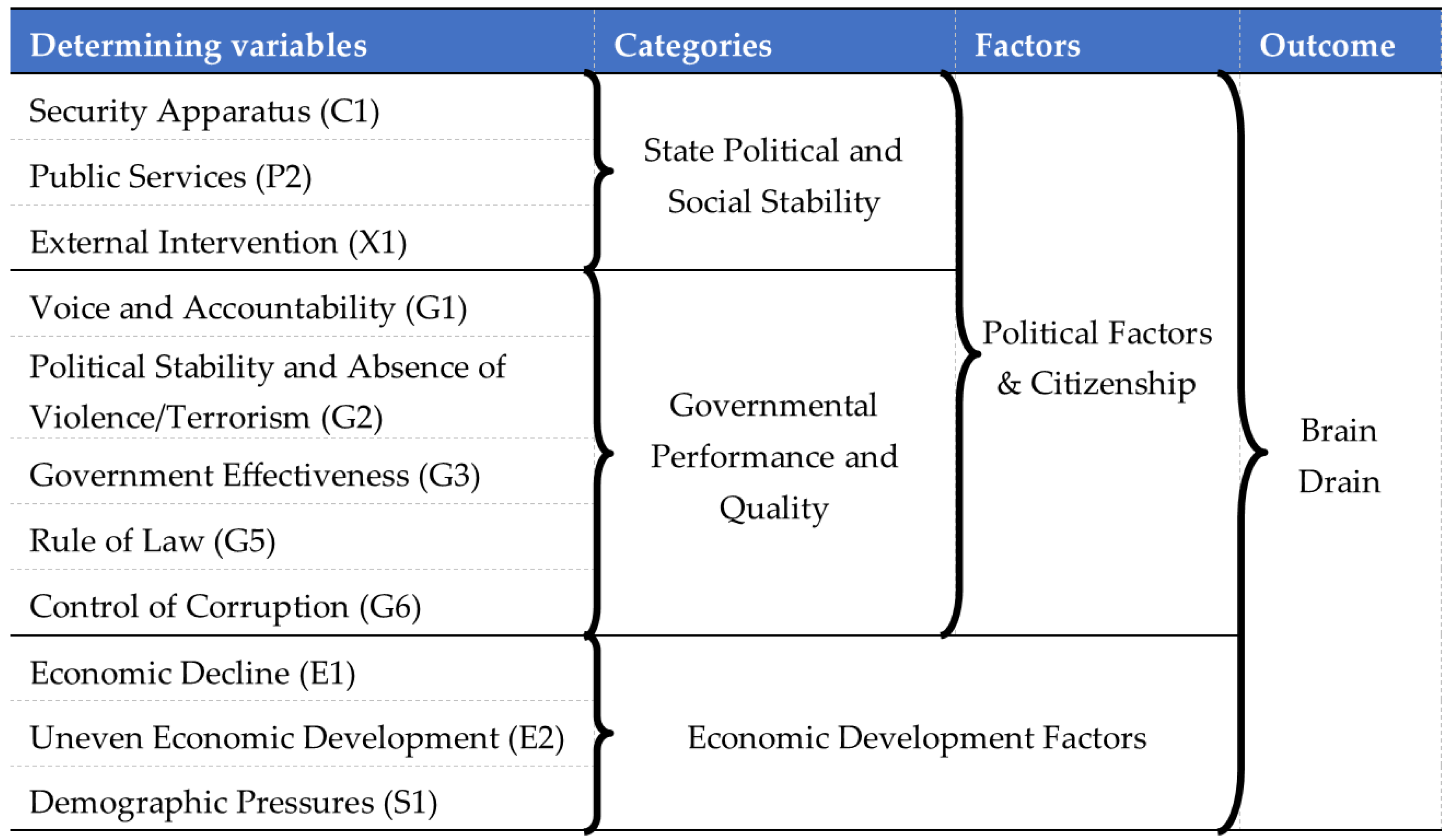

2.1. Political Factors and Citizenship: Implications of the Brain Drain

2.2. Economic Development Factors Behind the Brain Drain

3. Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

- Public Services (P2), significantly influence migration decisions and the improvement of which could reduce emigration intentions as a key factor in attracting talent and fostering regional development, as studied by Aliyev & Gasimov (2023) in Azerbaijan and by Zhang et al, (2024) within China, highlighting the importance of these elements as determinants of brain drain.

- External Intervention (X1), as a determinant of brain drain, intensifies in contexts of instability and destabilization, as observed in countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan, where external intervention and terrorist attacks aggravate the conditions that contribute to brain drain (Chee & Mu, 2021). Thus, the most fragile states experience greater vulnerability, which favors the outflow of talent, further exacerbating the brain drain phenomenon (Chee & Mu, 2021),

- Uneven Economic Development (E2), which drives brain drain, as workers seek better opportunities abroad due to limited prospects at home, a phenomenon analyzed by Petrou & Connell (2023) in Oceania, where international mobility is influenced by unequal labor markets, and

- Economic Decline (E1) driven by state fragility and regional imbalances, is a key determinant of brain drain, as it limits labor opportunities and exacerbates social tensions, especially during migration crises, reinforcing the need to strengthen local economic activities to mitigate these effects (Seyoum & Camargo, 2021; Carlsen & Bruggemann, 2017; Egyed & Zsibók, 2023).

6. Conclusions

- Public services: improving the quality of education, healthcare, infrastructure and security can reduce emigration by making life in the home country more attractive.

- External intervention: promoting international cooperation programs, foreign investment and offering incentives to returned emigrants can help retain talent.

- Uneven economic development: encouraging development in disadvantaged regions, creating regional innovation clusters and promoting local entrepreneurship can reduce internal and external emigration.

- Economic decline: maintaining economic stability, creating jobs in key sectors and supporting economic diversification will generate more opportunities within the country, reducing the need to emigrate.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Operational Definitions by Vega-Muñoz et al. (2024b) |

|---|---|

| Human Flight and Brain Drain (E3) |

“Economic impact of human mobility (for economic or political reasons) and its consequences for a country’s development”. |

| Security Apparatus (C1) | “Threats to the security of a State, such as bombings, attacks and deaths in combat, rebel movements, riots, coups d’état or terrorism”. |

| Economic Decline (E1) | “Progressive economic decline patterns of society, as measured by per capita income, Gross National Product, unemployment rates, inflation, productivity, debt, poverty levels or business failures”. |

| Uneven Economic Development (E2) |

“Inequality within the economy, regardless of the actual economic performance, such as structural inequality based on group (racial, ethnic, religious, or other identity group) or based on education, economic status, or region (urban-rural divide)”. |

| Public Services (P2) | “Basic state functions serving the population, such as the essential services (health, education, water and sanitation, transportation infrastructure, electricity and energy, and Internet and connectivity), and the state’s capability to protect its citizens through effective police”. |

| Demographic Pressures (S1) | “Pressures on the State derived from the demographic dynamics of the population and its environment, related to the vital resources supply (food, access to drinking water and others), health, and those derived from extreme meteorological phenomena and environmental hazards”. |

| External Intervention (X1) | “Influence and impact of external actors on State functioning. Whether in security aspects, with covert or overt intervention in the internal affairs of a State at risk affecting the internal power balance, or with economic engagement by external actors creating economic dependence (large-scale loans, development projects or foreign aid, continuous budgetary support, control of finances or management of the State’s economic policy). Also considering humanitarian intervention, such as the deployment of an international peacekeeping mission”. |

| Voice and Accountability (G1) | “Citizen perception in a country regarding participation in government elections, freedom of expression, association, and the media”. |

| Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism (G2) | “Perception of political instability and/or politically motivated violence, including terrorism”. |

| Government Effectiveness (G3) | “Quality perception of public services and the civil service, and their independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to those policies”. |

| Rule of Law (G5) | “Agents’ perceptions on trust and compliance with social rules, and in particular the quality of contractual compliance, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence”. |

| Control of Corruption (G6) | “Perception of the public power exercise for private benefit, including forms of small and large-scale corruption, as well as the "capture" of the state by elites and private interests”. |

Appendix B

| Model | Predictors | R | R-Squared | Adjusted R-Squared | Std. Error of Estimation | Adequate Betas Sign | VIF ≤ 10 | Feasible Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P2 | .776 | .602 | .601 | 1.296 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | P2, X1 | .816 | .666 | .666 | 1.187 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | P2, X1, E2 | .821 | .674 | .674 | 1.172 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4A | P2, X1, E2, C1 | .821 | .674 | .674 | 1.172 | No | Yes | No |

| 4B | P2, X1, E2, E1 | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4C | P2, X1, E2, S1 | .821 | .675 | .674 | 1.172 | No | Yes | No |

| 4D | P2, X1, E2, G1 | .826 | .683 | .683 | 1.156 | No | Yes | No |

| 4E | P2, X1, E2, G2 | .825 | .680 | .680 | 1.162 | No | Yes | No |

| 4F | P2, X1, E2, G3 | .822 | .675 | .675 | 1.171 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4G | P2, X1, E2, G5 | .822 | .676 | .676 | 1.169 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4H | P2, X1, E2, G6 | .822 | .676 | .676 | 1.169 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5B1 | P2, X1, E2, E1, C1 | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5B2 | P2, X1, E2, E1, S1 | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | No | Yes | No |

| 5B3 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G1 | .830 | .688 | .688 | 1.147 | No | Yes | No |

| 5B4 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G2 | .827 | .685 | .684 | 1.154 | No | Yes | No |

| 5B5 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G3 | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5B6 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G5 | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5B7 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G6 | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5F1 | P2, X1, E2, G3, C1 | .822 | .675 | .675 | 1.171 | No | Yes | No |

| 5F2 | P2, X1, E2, G3, E1 * | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5F3 | P2, X1, E2, G3, S1 | .824 | .675 | .674 | 1.171 | No | Yes | No |

| 5F4 | P2, X1, E2, G3, G1 | .830 | .689 | .689 | 1.145 | No | Yes | No |

| 5F5 | P2, X1, E2, G3, G2 | .826 | .682 | .682 | 1.158 | No | Yes | No |

| 5F6 | P2, X1, E2, G3, G5 | .823 | .677 | .676 | 1.168 | No | No (G3, G5) | No |

| 5F7 | P2, X1, E2, G3, G6 | .822 | .676 | .676 | 1.169 | No | No (G3) | No |

| 5G1 | P2, X1, E2, G5, C1 | .823 | .677 | .676 | 1.168 | No | Yes | No |

| 5G2 | P2, X1, E2, G5, E1 * | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5G3 | P2, X1, E2, G5, S1 | .822 | .676 | .676 | 1.169 | No | No (P2) | No |

| 5G4 | P2, X1, E2, G5, G1 | .835 | .698 | .698 | 1.129 | No | Yes | No |

| 5G5 | P2, X1, E2, G5, G2 | .829 | .687 | .686 | 1.150 | No | Yes | No |

| 5G6 | P2, X1, E2, G5, G3 | .823 | .677 | .676 | 1.168 | No | No (G3, G5) | No |

| 5G7 | P2, X1, E2, G5, G6 | .822 | .676 | .676 | 1.169 | Yes | No (G5) | No |

| 5H1 | P2, X1, E2, G6, C1 | .823 | .677 | .676 | 1.168 | No | Yes | No |

| 5H2 | P2, X1, E2, G6, E1 * | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5H3 | P2, X1, E2, G6, S1 | .822 | .676 | .676 | 1.169 | No | Yes | No |

| 5H4 | P2, X1, E2, G6, G1 | .833 | .695 | .694 | 1.135 | No | Yes | No |

| 5H5 | P2, X1, E2, G6, G2 | .829 | .687 | .686 | 1.150 | No | Yes | No |

| 5H6 | P2, X1, E2, G6, G3 * | .822 | .676 | .676 | 1.169 | No | No (G3) | No |

| 5H7 | P2, X1, E2, G6, G5 * | .822 | .676 | .676 | 1.169 | Yes | No (G5) | No |

| 6B11 | P2, X1, E2, E1, C1, S1 | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | No | No (P2) | No |

| 6B12 | P2, X1, E2, E1, C1, G1 | .832 | .690 | .689 | 1.144 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B13 | P2, X1, E2, E1, C1, G2 | .829 | .688 | .687 | 1.148 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B14 | P2, X1, E2, E1, C1, G3 | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B15 | P2, X1, E2, E1, C1, G5 | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B16 | P2, X1, E2, E1, C1, G6 | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B51 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G3, C1 * | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B52 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G3, S1 | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | No | No (P2) | No |

| 6B53 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G3, G1 | .832 | .692 | .691 | 1.141 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B54 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G3, G2 | .828 | .685 | .685 | 1.152 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B55 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G3, G5 | .826 | .682 | .681 | 1.159 | No | No (G3, G5) | No |

| 6B56 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G3, G6 | .826 | .682 | .681 | 1.159 | No | No (G3) | No |

| 6B61 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G5, C1 * | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B62 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G5, S1 | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | No | No (P2) | No |

| 6B63 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G5, G1 | .837 | .700 | .700 | 1.125 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B64 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G5, G2 | .830 | .690 | .689 | 1.145 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B65 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G5, G3 * | .826 | .682 | .681 | 1.159 | No | No (G3, G5) | No |

| 6B66 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G5, G6 | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | Yes | No (G5) | No |

| 6B71 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G6, C1 | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B72 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G6, S1 | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | No | No (P2) | No |

| 6B73 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G6, G1 | .835 | .698 | .697 | 1.129 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B74 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G6, G2 | .831 | .690 | .689 | 1.144 | No | Yes | No |

| 6B75 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G6, G3 | .826 | .682 | .681 | 1.159 | No | No (G3) | No |

| 6B76 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G6, G5 | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | No | No (G5, G6) | No |

| 11 | C1, E1, E2, P2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3, G5, G6 | .845 | .715 | .714 | 1.099 | No | No (P2, G3, G5, G6) | No |

| 10A | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3, G5, G6 | .844 | .712 | .711 | 1.103 | No | No (G3, G5, G6) | No |

| 10B | C1, E1, E2, P2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G5, G6 | .844 | .713 | .712 | 1.102 | No | No (P2, G5) | No |

| 10C | C1, E1, E2, P2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3, G6 | .842 | .709 | .709 | 1.108 | No | No (P2, G3) | No |

| 10D | C1, E1, E2, P2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3, G5 | .844 | .712 | .711 | 1.103 | No | No (P2, G3, G5) | No |

| 9A1 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G5, G6 | .843 | .711 | .710 | 1.105 | No | No (G5) | No |

| 9A2 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3, G6 | .841 | .707 | .706 | 1.113 | No | No (G3) | No |

| 9A3 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3, G5 | .842 | .710 | .709 | 1.108 | No | No (G3, G5) | No |

| 9B1 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G5, G6 | .843 | .711 | .710 | 1.105 | No | No (G5) | No |

| 9B2 | C1, E1, E2, P2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G6 | .842 | .709 | 709 | 1.108 | No | No (P2) | No |

| 9C1 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3, G6 | .841 | .707 | .706 | 1.113 | No | No (G3, G6) | No |

| 9C2 | C1, E1, E2, P2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G6 | .842 | .709 | .709 | 1.108 | No | No (P2) | No |

| 9D1 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3, G5 | .842 | .710 | .709 | 1.108 | No | No (G3, G5) | No |

| 9D2 | C1, E1, E2, P2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G5 | .843 | .711 | .710 | 1.105 | No | No (P2) | No |

| 9D3 | C1, E1, E2, P2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3 | .837 | .701 | .700 | 1.125 | No | No (P2) | No |

| 8A11 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G6 | .841 | .707 | .706 | 1.113 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8A21 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G6 * | .841 | .707 | .706 | 1.113 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8A31 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G5 | .842 | .709 | .709 | 1.108 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8A32 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3 | .835 | .697 | .696 | 1.131 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8B11 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G6 * | .841 | .707 | .706 | 1.113 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8B21 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G6 * | .841 | .707 | .706 | 1.113 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8C11 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G6 * | .841 | .707 | .706 | 1.113 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8C12 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3 * | .835 | .697 | .696 | 1.131 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8C21 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G6 * | .841 | .707 | .706 | 1.113 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8D11 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G5 * | .842 | .709 | .709 | 1.108 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8D12 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3 * | .835 | .697 | .696 | 1.131 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8D21 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G5 * | .842 | .709 | .709 | 1.108 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 8D31 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G2, G3 * | .835 | .697 | .696 | 1.131 | No (G1, G2) | Yes | No |

| 7A111 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G2, G6 | .828 | .686 | .686 | 1.151 | No (G2) | Yes | No |

| 7A112 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G6 | .834 | .696 | .695 | 1.133 | No (G1) | Yes | No |

| 7A311 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G2, G5 | .828 | .686 | .685 | 1.152 | No (G2) | Yes | No |

| 7A312 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G5 | .836 | .699 | .698 | 1.127 | No (G1) | Yes | No |

| 7A321 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G2, G3 | .826 | .682 | .681 | 1.159 | No (G2) | Yes | No |

| 7A321 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G1, G3 | .831 | .690 | .689 | 1.145 | No (G1) | Yes | No |

| 6A1111 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G6 | .822 | .676 | .675 | 1.170 | No (C1) | Yes | No |

| 6A1121 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G6 * | .822 | .676 | .675 | 1.170 | No (C1) | Yes | No |

| 6A3111 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G5 | .822 | .676 | .675 | 1.170 | No (C1) | Yes | No |

| 6A3121 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G5 * | .822 | .676 | .675 | 1.170 | No (C1) | Yes | No |

| 6A3211 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G3 | .821 | .673 | .673 | 1.174 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6A3211 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G3 * | .821 | .673 | .673 | 1.174 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5A11111 | E1, E2, S1, X1, G6 | .822 | .676 | .675 | 1.170 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5A11211 | E1, E2, S1, X1, G6 * | .822 | .676 | .675 | 1.170 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5A31111 | E1, E2, S1, X1, G5 | .822 | .675 | .675 | 1.170 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5A31211 | E1, E2, S1, X1, G5 * | .822 | .675 | .675 | 1.170 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dimension | Eigenvalue | Condition Index | Variance Proportions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | P2 | X1 | E2 | E1 | |||

| 1 | 4.816 | 1.000 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| 2 | .097 | 7.039 | .53 | .05 | .05 | .00 | .00 |

| 3 | .046 | 10.204 | .01 | .10 | .51 | .19 | .03 |

| 4 | .027 | 13.352 | .00 | .07 | .39 | .28 | .45 |

| 5 | .014 | 18.848 | .46 | .78 | .05 | .53 | .53 |

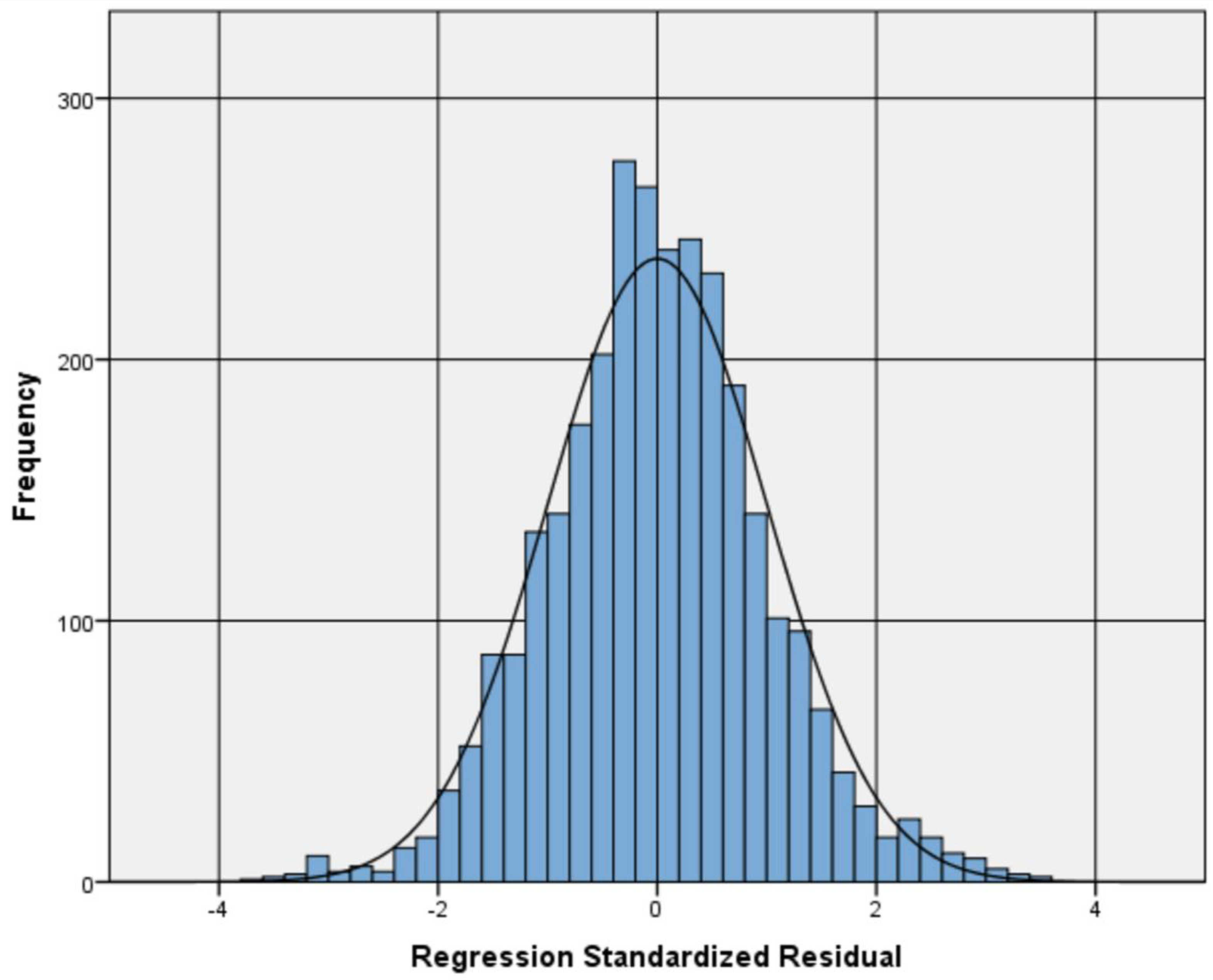

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted Value | 1.472 | 8.824 | 5.540 | 1.692 | 2989 |

| Residual | -4.242 | 3.983 | .000 | 1.162 | 2989 |

| Std. Predicted Value | -2.404 | 1.941 | .000 | 1.000 | 2989 |

| Std. Residual | -3.649 | 3.426 | .000 | .999 | 2989 |

References

- Aarhus, J.H.; Jakobsen, T.G. Rewards of reforms: Can economic freedom and reforms in developing countries reduce the brain drain? Int. Area Stud. Rev. 2019, 22, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, A.; Goujon, A.; Jiang, L. The Migration Intentions of Young Egyptians. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Hashish, E.; Ashour, H.M. Determinants and mitigating factors of the brain drain among Egyptian nurses: A mixed-methods study. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliyev, K.; Gasimov, I. Trust in government and intention to emigrate in a post-soviet country: evidence from Azerbaijan. Econ. Sociol. 2023, 16, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMunifi, A.A.; Aleryani, A.Y. Internal efficiency of higher education system in armed conflict-affected countries: Yemen case. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2021, 83, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asso, P.F. New perspectives on old inequalities: Italy’s north-south divide. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2021, 9, 346–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.; Cummings, M.; Vaaler, P. The social dividends of diaspora: Migrants, remittances, and changes in home-country rule of law. Proc. Int. Assoc. Bus. Soc. 2012, 23, 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Bauböck, R. Towards a political theory of migrant transnationalism. Int. Migr. Rev. 2003, 37, 700–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beine, M.; Docquier, F.; Rapoport, H. Brain drain and economic growth: theory and evidence J. Dev. Econ. 2001, 64, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhamou, K. Capacity building for sustainable energy access in the Sahel/Sahara region: Wind energy as catalyst for regional development. Nato sci peace secur. 2008, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverelli, C.; Orefice, G. Migration deflection: The role of Preferential Trade Agreements. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2019, 79, 103469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boc, E. Brain drain in the EU: Local and regional public policies and good practices. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2020, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carling, J The human dynamics of migrant transnationalism. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2008, 31, 1452–1477. [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, L.; Bruggemann, R. Fragile State Index: Trends and Developments. A Partial Order Data Analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 133, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, R.; Ruiz-Castillo, J. Spatial mobility in elite academic institutions in economics: The case of Spain. Series-J. Span. Econ. Assoc. 2019, 10, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Palaganas, E.; Spitzer, D.L.; Kabamalan, M.M.; Sanchez, M.C.; Caricativo, R.; Runnels, V.; Labonte, R.; Murphy, G.T.; Bourgeault, I.L. An examination of the causes, consequences, and policy responses to the migration of highly trained health personnel from the Philippines: the high cost of living/leaving-a mixed method study. Hum. Resour. Health. 2017, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, M. Brain drain, brain circulation, and the African diaspora in the United States. J. Afr. Bus. 2019, 20, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, L.; Mu, F. Spatiotemporal characteristics and driving forces of attacks in the Belt and Road Initiative countries. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooray, A.; Schneider, F. Does corruption promote emigration? An empirical examination. J. Popul. Econ. 2016, 29, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugeliene, R. , and Marcinkeviciene, R. Brain Circulation: Theoretical Considerations. Inz. Ekon. 2009, 3, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- De Haas, H. A theory of migration: the aspirations-capabilities framework. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2021, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-la-Vega-Hernández, I.M.; Barcellos-de-Paula, L. The quintuple helix innovation model and brain circulation in central, emerging and peripheral countries. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 2241–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, M.A. Subjectand migration intentions abroad: The case of Senegal. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2022, 34, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibeh, G.; Fakhri, A.; Marrouch, W. Decision to emigrate amongst the youth in Lebanon. Int. Migr. 2018, 56, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djajic, S.; Docquier, F.; Michael, M.S. Optimal education policy and human capital accumulation in the context of brain drain. J. Demogr. Econ. 2019, 85, 271–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docquier, F.; Marfouk, A. (2006). International migration by education attainment, 1990-2000. In C. Ozden, & M. Schiff (Eds.), International Migration, Remittances and the Brain Drain (pp. 151–200). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Docquier, F.; Rapoport, H. Globalization, Brain Drain, and Development. J. Econ. Lit. 2012, 50, 681–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docquier, F.; Lohest, O.; Marfouk, A. Brain drain in developing countries. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2007, 21, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egyed, I.; Zsibók, Z. Exploring firm performance in Central and Eastern European regions: A foundational approach. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2023, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakih, A.; El Baba, M. The willingness to emigrate in six MENA countries: The role of past revolutionary stress. Int. Migr. 2023, 61, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetzer, J.S.; Millen, B.A. The Causes of Emigration from Singapore: How Much Is Still Political? Crit. Asian Stud. 2015, 47, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, G. Quantifying the Malaysian Brain Drain and an Investigation of its Key Determinants. Malays. J. Econ. Stud. 2011, 48, 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, M.P. Discursive policy webs in a globalisation era: A discussion of access to professions and trades for immigrant professionals in Ontario, Canada. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2006, 4, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryan, A.; Khachatryan, S. Remittances and emigration intentions: Evidence from Armenia. Int. Migr. 2022, 60, 198–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, C.; Sano, Y.; Zarifa, D.; Haan, M. Will They Stay or Will They Go? Examining the Brain Drain in Canada's Provincial North. Can. Rev. Sociol. 2020, 57, 174–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoti, A. Determinants of emigration and its economic consequences: Evidence from Kosova. SE. Eur. Black Sea Stud. 2009, 9, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.N. Immigrant Skill Selection: A Case Study of South Africa and the USA. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 14, 101567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo, G. Migration and development in Asia and a role for Australia. J. Intercult. Stud. 2013, 34, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, R. Brain drain phenomenon in Romania: What comes in line after corruption? A quantitative analysis of the determinant causes of Romanian skilled migration. Rom. J. Commun. Public Relat. 2018, 20, 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ienciu, N.M.; Ienciu, A. Brain drain in Central and Eastern Europe: New insights on the role of public policy. SE. Eur. Black Sea Stud. 2015, 15, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbala, K.; Peng, H.; Hafeez, M.; Wang, Y.C.; Khurshid, L.I.; CY. The current wave and determinants of brain drain migration from China. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2020, 39, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jons, H. 'Brain circulation' and transnational knowledge networks: studying long-term effects of academic mobility to Germany 1954-2000. Glob. Netw. 2009, 9, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovcheska, S. Exploring corruption in higher education: A case study of brain drain in North Macedonia. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2024, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, M.; Gamedze, T.; Oghenetega, J. Mobility of sub-Saharan Africa doctoral graduates from South African universities—A tracer study. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2019, 68, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesselman, J.R. Policy implications of brain drain from Canada. Can. Public Policy 2001, 27, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.U.; Qureshi, J.A. The strategic role of public policies in technological innovation in Pakistan and lessons learnt from advanced countries: A comparative literature review. J. Organ. Behav. Res. 2020, 5, 212–232. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, J. European academic brain drain: A meta-synthesis. Eur. J. Educ. 2021, 56, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J. Anesthesiol 2019, 72, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Gëdeshi, I. Albanian students abroad: A potential brain drain? Cent. East. Eur. Migr. Rev. 2023, 12, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizhakethalackal, E.T.; Mukherjee, D.; Alvi, E. Count-data Analysis of physician Emigration from Developing Countries: A Note. Econ. Bull. 2015, 35, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Knauer, H. Strategic Approach Idea for Innovation Performance in Declining Rural Hinterland Areas. Rural development. 2009, 74, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, B.; Zent, R. Diaspora linkages benefit both sides: A single partnership experience. Glob. Health Action 2019, 12, 1645558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kritz, M.M. International student mobility and tertiary education capacity in Africa. Int. Migr. 2015, 53, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanati, M.; Thiele, R. Aid for health, economic growth, and the emigration of medical workers. J. Int. Dev. 2021, 33, 1112–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanko, D. Fear of Brain Drain: Russian Academic Community on Internationalization of Education. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2022, 26, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, C.H. The fragile environments of inexpensive CD4+T-cell enumeration in the least developed countries: Strategies for accessible support. Cytom. Part B-Clin. Cytom. 2008, 748, S107–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitin, C. Yeltsin voices concern over 'brain-drain'. Nature 1997, 390, 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leydesdorff, L. & Etzkowitz, H. Emergence of a Triple Helix of university—industry—government relations, Sci. Public Policy 1996, 23, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lo, L.; Lu, Y.X.; Tan, Y.N.; Lu, Z. Intellectual migration: Considering China. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020, 47, 2833–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, B.R. Brain drain and higher education in Nepal. Rout res high educ 2020, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.B.; Latukha, M.; Selivanovskikh, L. From brain drain to brain gain in emerging markets: exploring the new agenda for global talent management in talent migration. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2022, 17, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchal, B.; Kegels, G. Health workforce imbalances in times of globalization: Brain drain or professional mobility? Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2003, 18, S89–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, D.S.; Arango, J.; Hugo, G.; Kouaouci, A.; Pellegrino, A.; Taylor, J.E. Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review 1993, 19, 431–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, T.W.; Chophel, D. The impact and outcomes of (non-education) doctorates: The case of an emerging Bhutan. High Educ. 2020, 80, 1081–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, K.A. Meeting the goals of research with multiple linear regression. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1970, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, K. Debt administration in small island-states. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2019, 78, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monekosso, G.L. A brief history of medical education in Sub-Saharan Africa. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, S11–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, A.; Sang, G.Y. Brain drain in higher education: Critical voices on teacher education in Yemen. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2018, 16, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwapaura, K.; Chikoko, W.; Nyabeze, K.; Kabonga, I.; Zvokuomba, K. Provision of child protection services in Zimbabwe: Review of the human rights perspective. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.A.; Liu, Z.Y.; Younis, A.; Asghar, F.; Ghani, U.; Xu, Y. How governance structure, terrorism, and internationalization affect innovation: Evidence from Pakistan. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 33, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, T.; Zhao, L.X. Capital accumulation through studying abroad and return migration. Econ. Model. 2020, 87, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndjobo, P.M.N.; Simoes, N.C. Institutions and brain drain: The role of business start-up regulations. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2021, 13, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoma, AL.; Ismail, N.W. The determinants of brain drain in developing countries. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2013, 40, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittayaramphong, S.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Thailand - private health-care out of control. Health Policy Plan. 1994, 9, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotakopoulos, A. Investigating the factors affecting brain drain in Greece: Looking beyond the obvious. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 16, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejanovic, R.; Grubic-Nesic, L.; Birovljev, J.; Sedlak, O. Three missions of universities and the university-industry-state government triade. ICERI Proc. 2015, 6111–6118. [Google Scholar]

- Petrou, K.; Connell, J. Our 'Pacific family'. Heroes, guests, workers or a precariat? Aust. Geogr. 2023, 54, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoo, B.; Lee, C.Y.; Yu, C.M. Eliciting salient beliefs of engineers in Malaysia on migrating abroad. Migr. Lett. 2017, 14, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.L. Directly unproductive schooling: How country characteristics affect the impact of schooling on growth. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2008, 52, 356–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanov, E.V. What capitalism does Russia need? Methodological guidelines of the new industrialization. Econ. Soc. Chang. 2017, 10, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovska, Y.; Kozachenko, G.; Pogorelov, Y.; Pomazun, O.; Redko, K. Problems of development of economic security in Ukraine: Challenges and opportunities. Financ. Credit Act. 2022, 5, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safina, D. Favouritism and nepotism in an organization: Causes and effects. Proc. Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyoum, B.; Camargo, A. State fragility and foreign direct investment: The mediating roles of human flight and economic decline. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 63, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simplice, A. Globalization and health worker crisis: what do wealth-effects tell us? Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2014, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simplice, A. Determinants of health professionals' migration in Africa: a WHO based assessment. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2015, 42, 666–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spijkerboer, T. The Global Mobility Infrastructure: Reconceptualising the Externalisation of Migration Control Eur. J. Migr. Law. 2018, 20, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniscia, B.; Deravignone, L.; Gonzalez-Martin, B.; Pumares, P. Youth mobility and the development of human capital: Is there a Southern European model? J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, O.; Taylor, J.E. Relative Deprivation and International Migration. Demography 1989, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W.; Niño-Amézquita, L.; Kalyana, S. Geopolitics and multicultural environment as the determinants of personnel security. Manag. Res. Pract. 2021, 13, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Subhani, Z.H.; Tajuddin, N.A.; Diah, N.M. Muslim migration to the West: The case of the Muslim minority in India. Al-Shajarah 2018, 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Thaut, L. EU Integration & Emigration Consequences: The Case of Lithuania. Int. Migr. 2009, 47, 191–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Fund for Peace. Fragile States Index. (2025). Available in: https://fragilestatesindex.org/. (Accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Torrisi, B.; Pernagallo, G. Investigating the relationship between job satisfaction and academic brain drain: the Italian case. Scientometrics 2020, 124, 925–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.A.M.; Ozdeser, H.; Cavusoglu, B.; Aliyu, U.S. On the sustainable economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do remittances, human capital flight, and brain drain matter? Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Tung, R. Lure of country of origin: An exploratory study of ex-host country nationals in India. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1487–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Muñoz, A.; Gónzalez-Gómez-del-Miño, P.; Espinosa-Cristia, J.F. Recognizing New Trends in Brain Drain Studies in the Framework of Global Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Muñoz, A.; González-Gómez-del-Miño, P.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G. Scoping review about well-being in the ‘brain migration’ studies. MethodsX 2024, 13, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Muñoz, A.; González-Gómez-del-Miño, P.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G. Global panel data on World governance and state fragility from 2006 to 2022. Data Brief 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velema, T.A. The contingent nature of brain gain and brain circulation: their foreign context and the impact of return scientists on the scientific community in their country of origin. Scientometrics 2012, 93, 893–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X. The geopolitics of knowledge circulation: The situated agency of mimicking in/beyond China. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2020, 61, 740–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, P.; Steinkopf, T. Can Economic Freedom Cure Medical Brain Drain?, J. Priv. Enterp. 2014, 29, 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zea, D.G. Brain drain in Venezuela: The scope of the human capital crisis. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2020, 23, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hao, F.L.; Wang, S.J. Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Talent Inflow in Northeast China from the Perspective of Urban Amenity. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 5024011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Origin | N | Min | Max | Mean | Standard deviation | Pearson correlationwith E3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Flight and Brain Drain (E3) | FSI | 2989 | 0.4* | 10.0 | 5.540 | 2.05 | 1.00 |

| Security Apparatus (C1) | FSI | 2989 | 0.3* | 10.0 | 5.623 | 2.35 | 0.69 |

| Economic Decline (E1) | FSI | 2989 | 1.0* | 10.0 | 5.708 | 1.95 | 0.74 |

| Uneven Economic Development (E2) | FSI | 2989 | 0.5* | 10.0 | 6.150 | 2.07 | 0.72 |

| Public Services (P2) | FSI | 2989 | 0.6* | 10.0 | 5.617 | 2.49 | 0.78 |

| Demographic Pressures (S1) | FSI | 2989 | 0.7* | 10.0 | 6.039 | 2.27 | 0.74 |

| External Intervention (X1) | FSI | 2989 | 0.3* | 10.00 | 5.699 | 2.38 | 0.75 |

| Voice and Accountability (G1) | WGI | 2989 | -2.3 | 2.8* | -.138 | 1.01 | -0.46 |

| Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism (G2) | WGI | 2989 | -3.3 | 1.6* | -.170 | .97 | -0.53 |

| Government Effectiveness (G3) | WGI | 2989 | -2.4 | 2.5* | -.107 | 1.00 | -0.73 |

| Rule of Law (G5) | WGI | 2989 | -2.6 | 2.1* | -.151 | 1.00 | -0.72 |

| Control of Corruption (G6) | WGI | 2989 | -1.9 | 2.5* | -.124 | 1.01 | -0.65 |

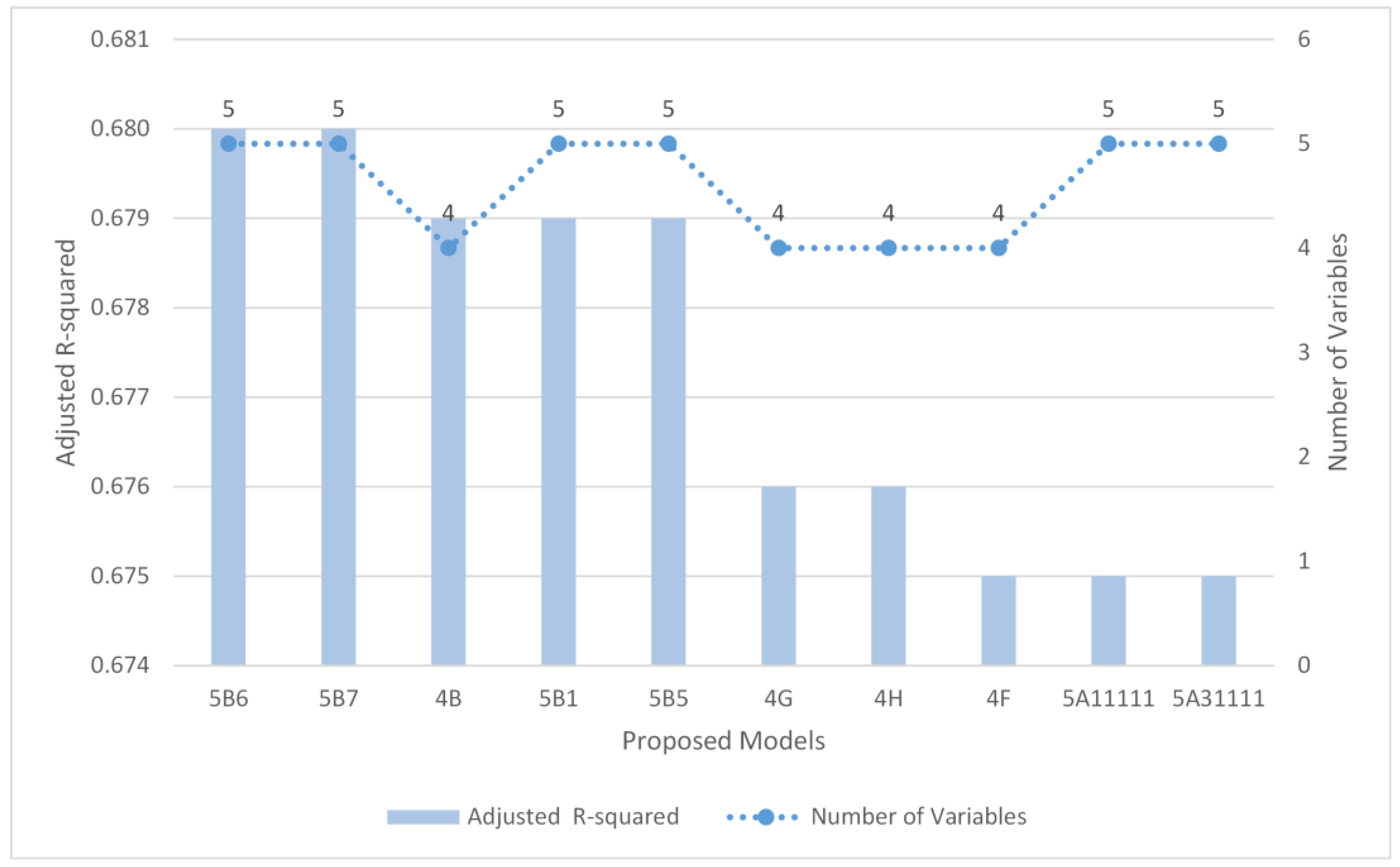

| Model | Number of Variables | Predictors | R | R-squared | Adjusted R-squared | Std. error of estimation | Adequate Betas sign | VIF ≤ 10 | Feasible model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5B6 | 5 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G5 | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5B7 | 5 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G6 | .825 | .681 | .680 | 1.161 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4B | 4 | P2, X1, E2, E1 | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5B1 | 5 | P2, X1, E2, E1, C1 | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5B5 | 5 | P2, X1, E2, E1, G3 | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4G | 4 | P2, X1, E2, G5 | .822 | .676 | .676 | 1.169 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4H | 4 | P2, X1, E2, G6 | .822 | .676 | .676 | 1.169 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4F | 4 | P2, X1, E2, G3 | .822 | .675 | .675 | 1.171 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5A11111 | 5 | E1, E2, S1, X1, G6 | .822 | .676 | .675 | 1.170 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5A31111 | 5 | E1, E2, S1, X1, G5 | .822 | .675 | .675 | 1.170 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | 3 | P2, X1, E2 | .821 | .674 | .674 | 1.172 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6A3211 | 6 | C1, E1, E2, S1, X1, G3 | .821 | .673 | .673 | 1.174 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | 2 | P2, X1 | .816 | .666 | .666 | 1.187 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 1 | 1 | P2 | .776 | .602 | .601 | 1.296 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Model | Sum of squares | Df | Mean Square | F test | Sig. | VIF > 10 | Condition index > 30 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5B6 | Regression | 8567.034 | 5 | 1713.407 | 1271.065 | .000 | No | No (19.250) |

| Residual | 4021.110 | 2983 | 1.348 | |||||

| Total | 12588.144 | 2988 | ||||||

| 5B7 | Regression | 8568.817 | 5 | 1713.763 | 1271.893 | .000 | No | No (19.126) |

| Residual | 4019.327 | 2983 | 1.347 | |||||

| Total | 12588.144 | 2988 | ||||||

| 4B | Regression | 8554.814 | 4 | 2138.703 | 1582.288 | .000 | No | No (18.848) |

| Residual | 4033.330 | 2984 | 1.352 | |||||

| Total | 12588.144 | 2988 | ||||||

| 5B1 | Regression | 8554.818 | 5 | 1710.964 | 1265.409 | .000 | No | No (20.806) |

| Residual | 4033.325 | 2983 | 1.352 | |||||

| Total | 12588.144 | 2988 | ||||||

| 5B5 | Regression | 8554.988 | 5 | 1711.000 | 1265.492 | .000 | No | No (19.304) |

| Residual | 4033.146 | 2983 | 1.352 | |||||

| Total | 12588.144 | 2988 | ||||||

| 4G | Regression | 8512.631 | 4 | 2128.158 | 1558.190 | .000 | No | No (14.744) |

| Residual | 4075.513 | 2984 | 1.366 | |||||

| Total | 12588.144 | 2988 | ||||||

| 4H | Regression | 8511.166 | 4 | 2127.792 | 1557.362 | .000 | No | No (14.684) |

| Residual | 4076.977 | 2984 | 1.366 | |||||

| Total | 12588.144 | 2988 | ||||||

| 4F | Regression | 8496.959 | 4 | 2124.240 | 1549.363 | .000 | No | No (15.104) |

| Residual | 4091.185 | 2984 | 1.371 | |||||

| Total | 12588.144 | 2988 | ||||||

| 5A11111 | Regression | 8503.904 | 5 | 1700.781 | 1242.197 | .000 | No | No (18.518) |

| Residual | 4084.240 | 2983 | 1.369 | |||||

| Total | 12588.144 | 2988 | ||||||

| 5A31111 | Regression | 8502.805 | 5 | 1700.561 | 1241.702 | .000 | No | No (18.760) |

| Residual | 4085.339 | 2983 | 1.370 | |||||

| Total | 12588.144 | 2988 | ||||||

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Root Mean Square | F Test | Sig. | R | R-Squared | AdjustedR-Squared | Standard Error of Estimation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 4B:P2, X1, E2, E1. | Regression | 8554.814 | 4 | 2138.703 | 1582.288 | .000 | .824 | .680 | .679 | 1.163 |

| Residual | 4033.330 | 2984 | 1.352 | |||||||

| Total | 12588.144 | 2988 | ||||||||

| Model 4B | UnstandardizedCoefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B |

Collinearity Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Constant) | .781 | .079 | 9.827 | .000 | .644 | .934 | |||

| Public Services (P2) | .214 | .021 | .259 | 10.285 | .000 | .174 | .256 | .169 | 5.908 |

| External Intervention (X1) | .275 | .016 | .319 | 17.699 | .000 | .239 | .309 | .331 | 3.020 |

| Uneven Economic Development (E2) | .184 | .019 | .185 | 9.628 | .000 | .145 | .219 | .292 | 3.429 |

| Economic Decline (E1) | .151 | .022 | .144 | 6.894 | .000 | .103 | .198 | .246 | 4.062 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).