1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Epidemiology

Echinococcosis, a zoonotic parasitic infection caused by the larvae of tapeworms of the genus Echinococcus, has long been recognized as a significant public health concern worldwide. Cystic echinococcosis (CE) and alveolar echinococcosis (AE) are the two main forms of echinococcosis. CE, caused by Echinococcus granulosus (E. granulosus), is the most frequent form and typically affects the liver and lungs [

1]. AE, caused by Echinococcus multilocularis, is less common but more severe, often leading to metastatic spread and extensive tissue damage, particularly affecting the liver [

2].

The global distribution of echinococcosis is closely associated with the presence of suitable intermediate hosts, primarily livestock such as sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs [

3]. Definitive hosts, predominantly canids such as dogs and foxes, harbor the adult tapeworms in their intestines and play a crucial role in the transmission cycle. Humans become accidental intermediate hosts by ingesting parasite eggs shed in the feces of infected definitive hosts, either through direct contact with contaminated soil or water or indirectly via consumption of contaminated food, particularly raw or undercooked meat [

4]. Echinococcosis exhibits a heterogeneous geographical distribution, with endemicity varying widely across different regions. Endemic foci are common in rural areas near livestock farming, where environmental and socioeconomic factors favor parasite transmission. Regions with nomadic or pastoralist lifestyles are at risk due to increased contact between humans, livestock, and infected canids [

5].

Certain regions have been identified as hotspots for echinococcosis transmission, including parts of Central and South America, Central Asia, the Mediterranean basin, Africa, and China. The prevalence of echinococcosis can vary significantly within endemic regions, influenced by climate, altitude, land use patterns, and human behavior. For example, high-altitude regions with extensive sheep farming, such as the Andean highlands of South America, have reported elevated rates of CE. Furthermore, migration and travel patterns contribute to the spread of echinococcosis, with imported cases reported in non-endemic areas due to increased mobility and globalization. In regions where echinococcosis is not endemic, cases often occur in immigrants from endemic areas or travelers returning from visits to these regions [

6].

1.2. Etiology and Life Cycle of Echinococcus Species

Echinococcosis is caused by the larval stages of tapeworms belonging to the genus Echinococcus. Several species within this genus can infect humans, including E. granulosus, Echinococcus multilocularis, Echinococcus oligarthrus, and Echinococcus vogeli [

7]. Each species has its distinct geographical distribution and lifecycle, leading to disease presentation and severity variations.

The primary species responsible for human infections are E. granulosus and Echinococcus multilocularis. E. granulosus causes cystic echinococcosis (CE), while E. multilocularis causes alveolar echinococcosis (AE). These species differ in their pathogenicity, lifecycle, and clinical manifestations. While CE typically forms cystic lesions in the liver and lungs, AE exhibits infiltrative growth patterns and can spread to other organs, particularly the liver [

8].

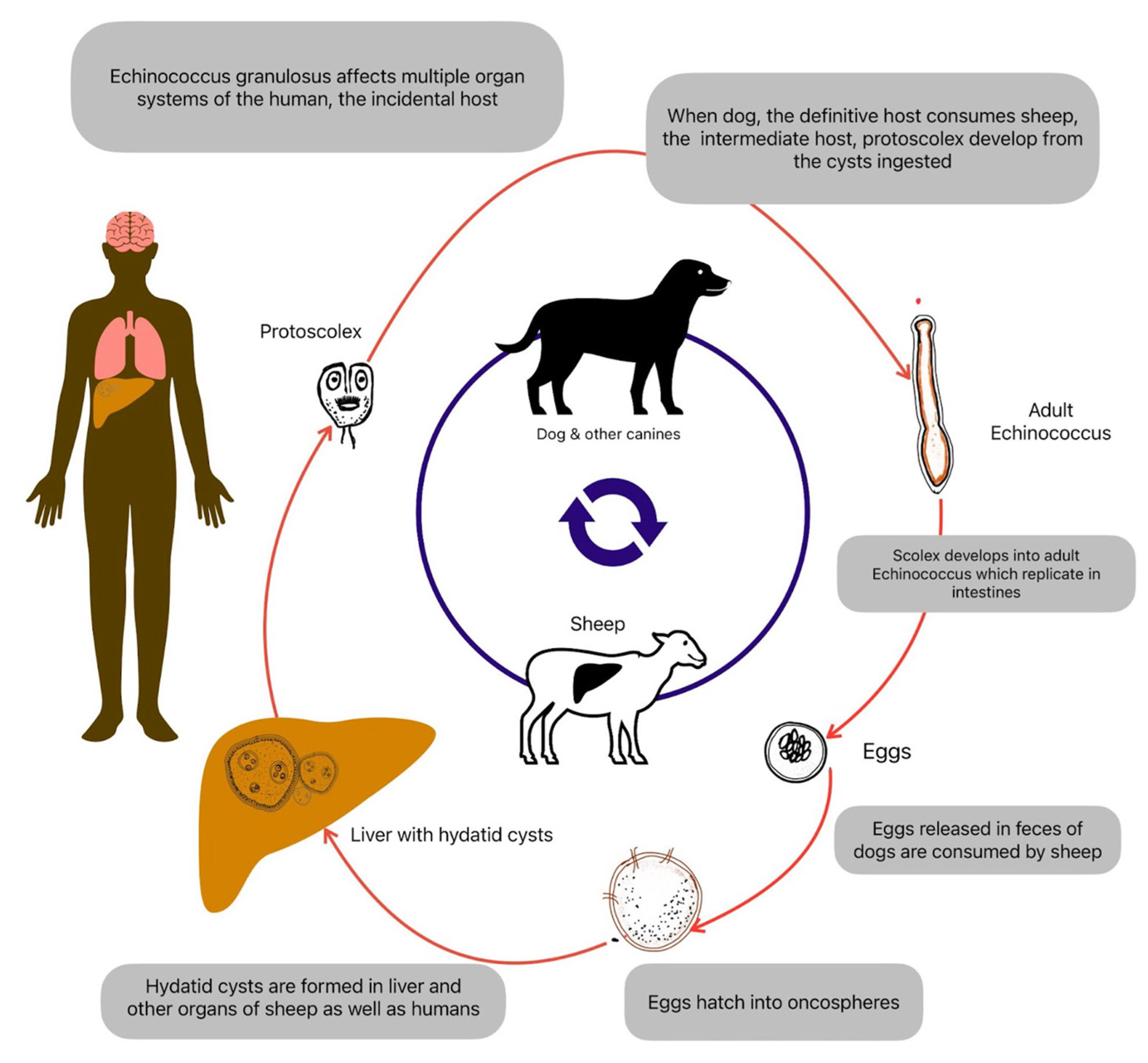

The life cycle of Echinococcus species involves definitive hosts, intermediate hosts, and occasionally, accidental intermediate hosts such as humans (

Figure 1). Canids such as dogs, foxes, and wolves serve as definitive hosts for Echinococcus species. Adult tapeworms reside in the small intestine of these animals, where they produce eggs known as “oncospheres.” These eggs are released into the environment through the feces of infected definitive hosts. Livestock such as sheep, goats, cattle, pigs, and other herbivores serve as intermediate hosts for Echinococcus species. Intermediate hosts become infected by ingesting parasite eggs in contaminated food, water, or vegetation. Once ingested, the eggs hatch in the intestine, releasing oncospheres that penetrate the intestinal wall and migrate through the bloodstream to various organs, developing into hydatid cysts. Within the intermediate host, oncospheres develop into fluid-filled cysts, which primarily localize in the liver and lungs but can also occur in other organs such as the spleen, kidneys, brain, and bones. These cysts contain numerous protoscoleces, small fluid-filled vesicles, and daughter cysts, representing potential sources of infection for definitive hosts [

9]. Definitive hosts become infected by ingesting the cystic material containing protoscoleces or daughter cysts from infected intermediate hosts. Once ingested, protoscoleces attach to the intestinal mucosa of the definitive host, where they develop into adult tapeworms, completing the lifecycle [

10].

Humans can become accidental intermediate hosts by ingesting Echinococcus eggs through contaminated food, water, or direct contact with infected definitive hosts. In humans, oncospheres develop into hydatid cysts, leading to echinococcosis. Accidental intermediate hosts do not contribute to the transmission of Echinococcus species to definitive hosts. Still, they can sustain the parasite life cycle by harboring cysts and serving as potential sources of infection for definitive hosts through improper hygiene practices or consumption of infected tissues [

11].

1.3. Neurological Manifestations in Echinococcosis

Neurological manifestations in echinococcosis, although relatively rare compared to hepatic or pulmonary involvement, can lead to severe morbidity and mortality. The central nervous system (CNS) may be affected either directly by the presence of cystic lesions or indirectly through inflammatory responses or mass effects caused by these lesions. Understanding the diverse neurological manifestations associated with echinococcosis is crucial for early recognition, appropriate management, and prevention of complications. Therefore, this study aims to review the neurological manifestations associated with Echinococcosis.

2. Pathogenesis of Neurological Involvement

2.1. Mechanisms of Central Nervous System Invasion

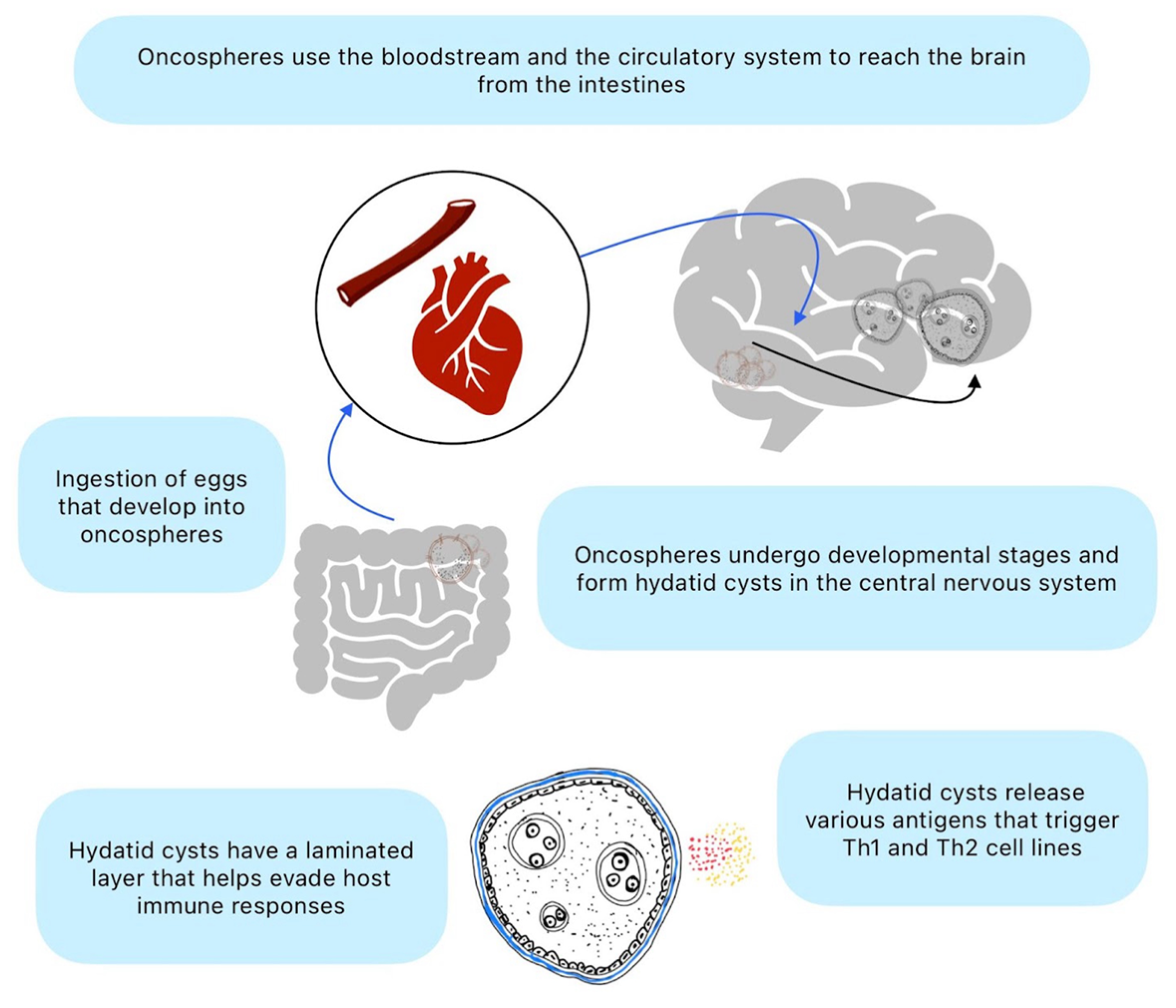

The invasion of the CNS by Echinococcus species involves complex mechanisms that allow the parasite to evade host immune responses and establish infection within the CNS tissues (

Figure 2). The initial step in CNS invasion involves the hematogenous spread of oncospheres from the intestine to distant organs, including the brain and spinal cord. After ingestion by the definitive host, Echinococcus eggs release oncospheres that penetrate the intestinal wall and enter the bloodstream. These oncospheres can then travel through the circulation and reach the CNS, where they can establish infection within the brain parenchyma or spinal cord [

12].

Echinococcus larvae possess various mechanisms to evade host immune responses, allowing them to survive and proliferate within the CNS tissues. The outer layer of the hydatid cyst, known as the laminated layer, contains antigens that modulate host immune responses and promote tolerance to the parasite [

13]. Additionally, the thick laminated layer and the host-derived adventitial layer surrounding the cyst act as physical barriers that protect the parasite from immune attack. Echinococcus larvae may induce immune tolerance within the CNS microenvironment, allowing them to persist and grow without triggering a robust inflammatory response [

14]. This immunomodulatory effect is thought to be mediated by various parasite-derived molecules, including excretory-secretory products and antigens released by the cyst.

Once Echinococcus larvae reach the CNS, they undergo metacestode development and form hydatid cysts within the brain parenchyma or spinal cord [

15]. The cysts grow slowly over time, gradually expanding and exerting mass effects on surrounding neural tissues. The cysts consist of an inner germinal layer, which produces protoscoleces and daughter cysts enclosed by the laminated and adventitial layers. Despite the immunomodulatory effects of Echinococcus larvae, the presence of hydatid cysts within the CNS can still trigger inflammatory responses from the host immune system. This inflammatory reaction may contribute to tissue damage, edema, and neurological symptoms associated with neuro-echinococcosis. In some cases, the host immune response may lead to the encapsulation or calcification of the cysts, resulting in a chronic, asymptomatic infection [

16].

2.2. Immunopathogenesis and Host Responses

The immunopathogenesis of neuro-echinococcosis involves a complex interplay between the parasite’s evasion strategies and the host immune responses. The host’s immune system recognizes Echinococcus species as foreign invaders and mounts innate and adaptive immune responses to combat the infection. However, the parasite has evolved various mechanisms to evade host immune surveillance, allowing it to establish chronic diseases within the CNS. Understanding these immunopathogenic mechanisms is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies against neuro-echinococcosis.

Macrophages and dendritic cells play a pivotal role in the initial recognition and phagocytosis of Echinococcus larvae and cysts within the CNS tissues [

17]. Toll-like receptors expressed on innate immune cells recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns present on the surface of Echinococcus species, triggering pro-inflammatory responses. Innate immune cells release cytokines such as interleukin-12, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interferon-gamma, promoting T lymphocyte activation and enhancing the anti-parasitic immune response.

T lymphocytes, particularly CD4+ T helper (Th) cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, play crucial roles in the adaptive immune responses against Echinococcus species within the CNS. Th1-type immune responses characterized by the production of IFN-γ and IL-2 are essential for activating macrophages and promoting the killing of intracellular parasites. Th2-type immune responses, marked by the production of cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10, are associated with humoral immunity and eosinophil recruitment but may also contribute to immunomodulation and parasite persistence [

18]. Regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells may dampen excessive inflammation, prevent immune-mediated tissue damage, promote immune tolerance, and facilitate parasite survival [

19].

The laminated layer of the hydatid cyst acts as a physical barrier that prevents direct contact between the parasite and host immune cells, shielding the parasite from immune recognition and attack. Echinococcus larvae release excretory-secretory products and antigens that modulate host immune responses, promoting immune tolerance and evasion. Antigenic variation and mimicry may allow Echinococcus species to evade host immune surveillance by altering their surface antigens and escaping detection by the host immune system [

20].

Chronic immune-mediated inflammation within the CNS can lead to tissue damage, edema, and neurological deficits associated with neuro-echinococcosis. Inflammatory responses may contribute to the formation of granulomatous reactions, fibrosis, and calcification around the hydatid cysts, further impairing neurological function [

19].

3. Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of neuro-echinococcosis can vary widely depending on the location, size, number, and stage of development of the cystic lesions within the CNS. The symptoms may be nonspecific and mimic other neurological conditions, challenging diagnosis.

Persistent or recurrent headaches are common in patients with intracranial echinococcosis. Depending on the location of the cystic lesions within the brain or spinal cord, patients may present with focal neurological deficits corresponding to the affected area. Seizures are a common manifestation of intracranial echinococcosis, particularly in cases involving cortical or subcortical regions of the brain [

21]. Echinococcal cysts located in the frontal or temporal lobes of the brain may cause cognitive dysfunction, memory impairment, personality changes, or psychiatric symptoms such as depression or anxiety. Large or rapidly growing intracranial cysts may lead to signs and symptoms of increased ICP, including papilledema, visual disturbances, altered mental status, drowsiness, or coma [

22]. Patients with spinal echinococcosis may experience radicular pain radiating along the distribution of affected nerve roots. Spinal echinococcosis involving the lower thoracic, lumbar, or sacral spinal cord segments may lead to urinary or fecal incontinence, retention, or other bladder and bowel dysfunction (Table 1) [

23].

|

Table 1. Classification Of Spinal Hydatid Disease By Braithwaite et al. [23] |

| Type |

Description |

| Type 1 |

Hydatid cyst is intramedullary |

| Type 2 |

Hydatid cyst is intradural and extramedullary |

| Type 3 |

Hydatid cyst is extradural and intraspinal |

| Type 4 |

Hydatid cyst is in the vertebral body |

| Type 5 |

Hydatid cyst is paravertebral |

3.1. Atypical Presentations

Some cases of neuro-echinococcosis may be asymptomatic and incidentally detected on imaging studies performed for unrelated reasons. Asymptomatic cystic lesions may remain clinically silent for prolonged periods or may present with nonspecific symptoms that do not prompt further evaluation. In rare cases, neuro-echinococcosis may manifest with isolated psychiatric symptoms such as psychosis, mania, or personality changes. These atypical presentations may result from the involvement of specific brain regions or the effects of inflammatory mediators on neurotransmitter pathways [

24].

Hydatidosis, caused by the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus, primarily affects the liver and lungs but can rarely involve the brain. Gader et al. reported a child with a hydatid cyst in the brainstem, leading to progressive walking difficulties and limb impairment [

25]. An MRI confirmed the diagnosis, necessitating surgical intervention due to the lesion's size and location. The cyst was successfully decompressed and excised, followed by albendazole treatment. The patient had a smooth recovery and showed no signs of recurrence after 2 years.

Extradural hydatid cysts are extremely rare. Borni et al. reported a distinctive case of a pediatric patient from North Africa residing in a rural area who showed a painless swelling in the left parieto-occipital region without any neurological symptoms [

26]. The condition was treated successfully through surgery, making it an undocumented case within the pediatric demographic. Kharosekar reported a similar case of primary multiple intracranial extradural hydatid cysts [

27].

Neuro-echinococcosis may mimic other neurological conditions, including brain tumors, vascular lesions, demyelinating diseases, or infectious processes such as neurocysticercosis or tuberculoma [

28]. Differential diagnosis may be challenging, requiring careful consideration of clinical, radiological, and laboratory findings. Spinal echinococcosis can present with symptoms of spinal cord compression, such as radicular pain, motor weakness, sensory deficits, or bladder and bowel dysfunction. However, these symptoms may be nonspecific and mimic other spinal pathologies, necessitating careful evaluation and imaging studies.

Intracranial alveolar echinococcosis (IAE) constitutes a significant zoonotic health concern in the Tibetan region. Li et al. study delineates the clinical and radiological characteristics of 21 IAE patients who were treated at the Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture People's Hospital. The cohort had an average age of 44.1 years, with a predominance of male patients (61.9%). The principal presenting symptom was headache, reported by 81.0% of the patients. All patients exhibited liver involvement, with neuroimaging revealing low-signal shadows and small vesicles. Notably, 28.6% of the patients displayed hepatic portal invasion. Compliance with albendazole therapy was notably poor, with 52.4% of patients demonstrating inadequate adherence. Surgical intervention was undertaken in 11 patients, yielding variable outcomes. During the follow-up period, which averaged 21.7 months, 47.6% of the patients succumbed to the condition, with a median interval of 84 months from diagnosis to mortality. Despite advancements in both diagnostic techniques and treatment modalities, the management of IAE continues to present considerable challenges, underscoring the necessity for enhanced patient education regarding medication compliance [

29].

Hydatid cysts constitute less than four percent of all intracranial space-occupying lesions. Interestingly, brain involvement in hydatid disease, especially for intraventricular cyst location, is rare and occurs primarily in children (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Literature Cases Of Cerebral Intraventricular Hydatid Cyst. |

| Reference |

Age, Sex |

Number of cysts |

Intraventricular location in CNS |

Clinical features |

| Copley et al. (1992) [30] |

12, F7, M |

1 |

Lateral ventricle |

Headache, dizziness |

| Diren et al. (1993) [31] |

10, F |

2 |

Frontal horn of the right lateral ventricle |

Headache, right proptosis |

| Gupta et al. (1999) [32] |

NA |

1 |

Lateral ventricle |

Focal neurological deficits and features of raised intracranial pressure |

| Aydin et al. (2002) [33] |

18, M |

4 |

Right lateral ventricle |

Headache, blurred vision, vertigo, vomiting |

| Iyigun et al. (2004) [34] |

2, M |

1 |

Right lateral ventricle |

Focal neurological deficit |

| Bukte et al. (2004) [35] |

7, F |

1 |

Posterior fossa, 4th ventricle |

Cerebellar deficit, ataxia |

| Evliyaoglu et al. (2005) [36] |

7, F |

1 |

Lateral ventricle |

Headache, nausea, vomiting |

| Maurya et al. (2007) [37] |

25, F |

1 |

Right lateral ventricle |

Complex partial seizures, bifrontal headache, and bilateral papilledema |

| Guzel et al. (2008) [38] |

10, F |

1 |

Right lateral ventricle |

Headache |

| Kamath et al. (2009) |

6, F |

1 |

Right lateral ventricle |

Headache, vomiting, and left hemiparesis |

| Kamali et al. (2011) [39] |

25, F |

1 |

Right lateral ventricle |

Partial seizures, bifrontal headache, bilateral papilledema |

| Sanlı et al. (2012) [40] |

7, M |

1 |

Ambient cistern |

Headache, nausea, vomiting, progressive drowsiness |

| Prasad et al. (2013) [41] |

20, M |

1 |

Third ventricle |

Headache |

| Pandey et al. (2015) [42] |

21, F |

1 |

Left lateral ventricle |

Headache and difficulty in walking |

| Qadri et al. (2017) [43] |

24, M |

1 |

Right lateral ventricle |

Tinnitus, decreased hearing, headache, vertigo, nausea, vomiting, bilateral papilledema |

| Sadashiva et al. (2018) [44] |

7, M |

1 |

Left trigone and occipital horn of the lateral ventricle |

Altered sensorium, vomiting, headache |

| Samadian et al. (2020) [45] |

3, F |

1 |

Third ventricle |

Headache, nausea |

| Maamri et al. (2022) [46] |

7, F |

1 |

Third ventricle |

Headache, seizures, and raised intracranial pressure. |

| Abbreviations: F, female; M, male. |

4. Diagnostic Approaches

Diagnostic approaches for neuro-echinococcosis involve clinical evaluation, imaging studies, serological tests, and occasionally cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. A thorough clinical history and physical examination are essential for identifying neurological symptoms and signs suggestive of neuro-echinococcosis. Symptoms such as headache, focal neurological deficits, seizures, and signs of increased intracranial pressure should raise suspicion for CNS involvement.

CSF analysis may reveal elevated protein levels, pleocytosis (predominantly lymphocytic), and occasionally eosinophilia in patients with neuro-echinococcosis [

47]. Detection of Echinococcus species. antigens or DNA in CSF samples using molecular techniques may provide additional diagnostic confirmation. Histopathological examination of biopsy specimens obtained from surgical resection or aspiration of cystic lesions may be necessary for definitive diagnosis, particularly in cases with atypical imaging findings or diagnostic uncertainty. Histological features characteristic of Echinococcus species. include laminated layers, germinal membranes, and protoscoleces [

48].

Serological testing plays a complementary role in diagnosing neuro-echinococcosis, particularly in cases where imaging findings are inconclusive or when confirmation of the diagnosis is needed. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and immunoblot assays can detect specific antibodies against antigens of Echinococcus species in serum or CSF samples. Serological tests may aid in confirming the diagnosis, monitoring treatment response, and detecting recurrence of infection[

49]. However, false-positive results and cross-reactivity with other parasitic infections should be considered, particularly in endemic regions with overlapping antigenic profiles.

4.1. Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging should be used to assess intracranial and spinal lesions associated with neuro-echinococcosis initially. The benefit of performing a cranial CT scan compared to a brain MRI is its superiority in detecting the cyst wall or septa calcification. However, brain MRI can be better at detecting multiplicity and defining the anatomic relationship of the lesion with the adjacent structures. Also, in recurrent disease, the surrounding edema can be better delineated by revealing subtle differences in tissue content.

The most common location of neuro-echinococcosis in CNS is the hemispheric parenchyma [

50]. Also, the cysts can rarely be found in the subarachnoid spaces, lateral ventricle, and cerebellum [

51]. Most cysts contain clear fluid, usually associated with small daughter cysts and a granular deposit of scolices. On neuroimaging, the hydatid lesions appear as significant, spherical cystic masses well demarcated from the surrounding brain parenchyma, with cyst fluid isodense with CSF on CT scans and isointense with CSF on MRI studies with no surrounding edema. Usually, partial or complete contrast enhancement involving the cystic wall is observed. The peripheral capsule of the cyst can generally be seen on MRI imaging, and calcification of the wall is better identified on CT imaging.

4.2. Challenges in Diagnosis

Diagnosing neurological echinococcosis poses several challenges due to its diverse clinical presentations, nonspecific symptoms, and overlapping features with other neurological conditions. Additionally, the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria and limited availability of specific diagnostic tests further complicate the diagnostic process. Neurological echinococcosis can present with nonspecific symptoms, which are not unique to echinococcosis and may mimic other neurological conditions [

52].

Radiological imaging studies are essential for diagnosing neuro-echinococcosis. However, interpreting imaging findings can be challenging, particularly in cases with atypical or nonspecific features. Echinococcal cysts may resemble other cystic lesions such as tumors, abscesses, or vascular malformations, necessitating careful evaluation by experienced radiologists. Differential diagnosis of neuro-echinococcosis includes a wide range of neurological conditions. Distinguishing between these entities based on clinical, radiological, and laboratory findings can be challenging and may require a systematic approach and multidisciplinary evaluation.

Serological tests for echinococcosis are valuable diagnostic tools. However, these tests have limitations, including variable sensitivity and specificity, cross-reactivity with other parasitic infections, and inability to differentiate between active and past infections. False-positive and false-negative results may occur, particularly in low-prevalence settings or in patients with atypical presentations. Access to specialized diagnostic resources may be scarce in resource-limited settings and endemic regions. Lack of infrastructure, trained personnel, and financial constraints can hinder the timely diagnosis and management of neuro-echinococcosis in these settings [

53].

Histopathological examination of biopsy specimens obtained from surgical resection or aspiration of cystic lesions may provide a definitive diagnosis of neuro-echinococcosis [

54]. However, obtaining tissue samples may not always be feasible, particularly in cases with deep-seated or inaccessible lesions, and carries inherent risks of surgical morbidity and complications.

4.3. Differential Diagnosis

Neurocysticercosis usually presents with a higher number of lesions instead when compared to echinococcosis, also the common CNS locations are the gray matter-white matter junction and deep sulci, and it is less common in subarachnoid spaces and ventricles (especially the fourth ventricle) [

42]. Some of the radiological findings in neurocysticercosis are multiple lesions in different stages of development. The stages are vesicular, colloidal vesicular, granular nodular, and calcified [

55].

Focal brain lesions mainly localized to the basal ganglia are commonly observed in neurotoxoplasmosis. Post-contrast T1-weighted images may exhibit a highly suggestive abscess aspect: “the target sign” with rim enhancement and central hypointensity with a little eccentric nodule of contrast inside the mass. Another typical radiological finding is multiple ring-enhancing lesions in both cerebral hemispheres [

56].

Well-circumscribed lesions with the same signal intensity, with no contrast enhancement, suggest an arachnoid cyst. Arachnoid cysts are believed to be congenital lesions and may have large sizes but generally do not communicate with the ventricles, are not spherical, are not surrounded entirely by brain substance, are extra-axial masses that may deform adjacent brain, and have an irregular inner border.

Porencephalic cysts are lined by gliotic white matter. Usually, it is not spherical, not surrounded entirely by brain substances resulting from insults to normal brain tissue [

21]. Epidermoid cysts are hypodense lesions that resemble CSF and do not enhance with contrast agents. May develop within the frontal, parietal, or petrous bone and may destroy the inner and outer table of the cranial bone to cause soft-tissue swelling under the scalp well-demarcated, encapsulated lesions, with a whitish capsule of a mother-of-pearl sheen lined by stratified squamous epithelium and are filled with debris, keratin, water, and cholesterol crystals [

57].

5. Management Strategies

Neuro-echinococcosis management strategies aim to achieve several key objectives, including reducing cyst burden, relieving symptoms, preventing complications, and minimizing the risk of disease recurrence. Treatment approaches typically involve a combination of pharmacotherapy, surgical intervention, and adjunctive measures. The choice of management strategy depends on factors such as the location, size, and stage of cystic lesions, the patient's clinical presentation, and overall health status.

Benzimidazole derivatives such as albendazole and mebendazole are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy for neuro-echinococcosis [

58]. These agents exert parasiticidal effects by disrupting microtubule polymerization and inhibiting glucose uptake, leading to cyst degeneration and parasite death. Albendazole is preferred due to its superior bioavailability and tissue penetration. Antiparasitic therapy is typically administered for extended periods, ranging from several months to years, depending on the response to treatment and the risk of disease recurrence. Combination therapy with albendazole and praziquantel may be considered in select cases, particularly for complex or refractory infections. Regular clinical and radiological assessments are essential for monitoring treatment response, detecting adverse effects, and evaluating the need for treatment modifications. Serum drug levels may be measured to optimize dosing and ensure therapeutic efficacy.

Surgical resection or aspiration of cystic lesions may be indicated in symptomatic or complicated neuro-echinococcosis cases, such as large cysts causing mass effect, cyst rupture, or spinal cord compression [

59]. Surgical goals include completely removing cystic material, preserving neurological function, and preventing cyst dissemination or recurrence. Minimally invasive techniques such as endoscopic or percutaneous approaches may be considered for select cases, offering advantages such as reduced morbidity and shorter recovery times.

Systemic corticosteroids may reduce pericystic inflammation, edema, and mass effects associated with neuro-echinococcosis [

60]. Steroids may be initiated before or concomitantly with antiparasitic therapy and tapered gradually based on clinical response. Patients with neuro-echinococcosis presenting with seizures may require treatment with AEDs to control seizure activity and prevent recurrence [

61]. AED selection and dosing should be individualized based on seizure type, frequency, and patient preferences.

Percutaneous aspiration-injection-reaspiration (PAIR) is a minimally invasive radiological procedure used to treat cystic lesions in various organs, including the brain and spinal cord. This technique involves percutaneous aspiration of cystic fluid, injection of scolicidal agents (e.g., hypertonic saline or ethanol), and reaspiration of cyst contents to decompress the cyst and induce parasite death [

62].

Long-term follow-up is essential for monitoring treatment response, assessing for disease recurrence, and managing potential complications such as cyst rupture or secondary infections. Regular clinical evaluations, imaging studies, and serological tests are recommended to ensure optimal patient outcomes and minimize the risk of disease relapse.

6. Challenges and Future Directions

Neuro-echinococcosis presents diagnostic challenges due to its nonspecific clinical manifestations and imaging findings that can resemble other neurological conditions. Improving diagnostic modalities, including serological tests and imaging techniques, is crucial for accurate and timely diagnosis. Some cases of neuro-echinococcosis may exhibit resistance to conventional pharmacotherapy, leading to treatment failure or disease recurrence. Understanding the mechanisms of drug resistance and developing novel therapeutic strategies are essential for improving treatment outcomes [

63].

Surgical management of neuro-echinococcosis carries inherent risks, including neurological deficits, cyst rupture, and postoperative complications [

64]. Minimizing surgical morbidity and optimizing patient outcomes requires careful patient selection, surgical expertise, and perioperative management. Limited surveillance systems and underreporting contribute to the underestimation of the actual burden of neuro-echinococcosis, particularly in endemic regions. Strengthening disease surveillance and implementing standardized reporting protocols are essential for monitoring disease trends and informing public health interventions.

New antiparasitic agents with improved efficacy, safety profiles, and mechanisms of action against Echinococcus species are needed [

65]. Targeting specific parasite pathways or exploiting host-parasite interactions may offer promising avenues for drug discovery. Harnessing the host immune response to enhance parasite clearance and prevent disease progression is a promising therapeutic approach for neuro-echinococcosis. Immunomodulatory agents or vaccine-based strategies to boost protective immune responses warrant further investigation.

Advancements in molecular diagnostics and personalized medicine may enable tailored treatment regimens based on individual patient characteristics, including genetic factors, immune status, and parasite genotype [

66]. Precision medicine approaches can optimize therapeutic outcomes and minimize adverse effects.

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a widely occurring zoonotic illness caused by the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus, which can result in serious complications in humans. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are becoming recognized as crucial components in parasitic infections, impacting the immune responses of the host. Shi et al. investigated EVs obtained from mice infected with E. granulosus at different infection stages. The authors isolated EVs utilizing the ExoQuick and ExoEasy kits and characterized them through transmission electron microscopy, nanoparticle tracking analysis, and immunoblotting techniques. Proteomic evaluation of plasma EVs was conducted using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), identifying proteins with differential expression through bioinformatics approaches. In vitro co-culture studies revealed that EVs promoted the increase of regulatory T (Treg) cells and levels of IL-10. They observed that these EVs can be taken up by T cells, B cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), demonstrating their function as immune modulators [

67].

Echinococcosis is a long-lasting zoonotic disease caused by Echinococcus tapeworms, often necessitating expensive and complex treatments, including surgical intervention. Existing diagnostic methods depend on ultrasound and immunological testing, but these techniques usually identify infections during advanced stages. Wan et al. research analyzed cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from the plasma of patients with echinococcosis and confirmed the presence of Echinococcus DNA. Wan et al.created a targeted next-generation sequencing technique that can identify as little as 0.1% of the Echinococcus genome in 1 mL of plasma. The plasma results from patients showed an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.862, with a sensitivity of 62.50% and a specificity of 100%. Their study suggests that hydatid cysts release cfDNA into the bloodstream, introducing a new, highly specific approach for the non-invasive detection of echinococcosis [

68].

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, neuro-echinococcosis remains a challenging and potentially debilitating condition that requires comprehensive management approaches to optimize patient outcomes. Despite advancements in diagnostic modalities, treatment options, and disease surveillance, several challenges persist, including diagnostic limitations, treatment resistance, surgical risks, and inadequate disease surveillance. Addressing these challenges and exploring future research and clinical practice directions are essential for improving the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of neuro-echinococcosis. Moving forward, there is a need for continued investment in research and innovation to develop novel diagnostic tools, therapeutic agents, and immunomodulatory approaches tailored to the unique characteristics of neuro-echinococcosis.

Supplementary Materials

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.R., V.V.B., and A.L.F.C.; methodology, A.L.F.C.; software, A.L.F.C.; validation, A.L.F.C., J.P.R. and V.V.B.; formal analysis, A.L.F.C.; investigation, A.L.F.C.; resources, A.L.F.C.; data curation, J.P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.R.; writing—review and editing, J.P.R.; visualization, V.V.B.; supervision, V.V.B.; project administration, V.V.B.; funding acquisition, J.P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Woolsey, I.D.; Miller, A.L. Echinococcus Granulosus Sensu Lato and Echinococcus Multilocularis: A Review. Res Vet Sci 2021, 135, 517–522. [CrossRef]

- Craig, P. Echinococcus Multilocularis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2003, 16, 437–444. [CrossRef]

- Tigre, W.; Deresa, B.; Haile, A.; Gabriël, S.; Victor, B.; Pelt, J.V.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Vercruysse, J.; Dorny, P. Molecular Characterization of Echinococcus Granulosus s.l. Cysts from Cattle, Camels, Goats and Pigs in Ethiopia. Vet Parasitol 2016, 215, 17–21. [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, Y.; Omar, S.S.; Dadar, M.; Pilevar, Z.; Sahlabadi, F.; Torabbeigi, M.; Rezaeiarshad, N.; Abbasi, F.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. The Prevalence of Hydatid Cyst in Raw Meat Products: A Global Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 26094. [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, C.N. Epidemiology and Control of Parasites in Nomadic Situations. Vet Parasitol 1994, 54, 87–102. [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Nazeer, S.; Elahi, M.M.S.; Idu, E.G.; Zhang, H.; Mahmoudvand, H.; Khan, S.N.; Yang, J. Global Distribution and Definitive Host Range of Echinococcus Species and Genotypes: A Systematic Review. Vet Parasitol 2024, 331, 110273. [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, A.; Rausch, R.L. New Aspects of Neotropical Polycystic (Echinococcus Vogeli) and Unicystic (Echinococcus Oligarthrus) Echinococcosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2008, 21, 380–401, table of contents. [CrossRef]

- Czermak, B.V.; Akhan, O.; Hiemetzberger, R.; Zelger, B.; Vogel, W.; Jaschke, W.; Rieger, M.; Kim, S.Y.; Lim, J.H. Echinococcosis of the Liver. Abdom Imaging 2008, 33, 133–143. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, L.; Huang, D.; Tian, M.; Shen, Y.; Deng, J.; Hou, J.; et al. Echinococcus Multilocularis Protoscoleces Enhance Glycolysis to Promote M2 Macrophages through PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Pathog Glob Health 2023, 117, 409–416. [CrossRef]

- Smyth, J. Studies on Tapeworm Physiology: XI. In Vitro Cultivation of Echinococcus Granulosus from the Protoscolex to the Strobilate Stage. Parasitology 1967, 57, 111–133.

- Romig, T.; Deplazes, P.; Jenkins, D.; Giraudoux, P.; Massolo, A.; Craig, P.S.; Wassermann, M.; Takahashi, K.; de la Rue, M. Ecology and Life Cycle Patterns of Echinococcus Species. Adv Parasitol 2017, 95, 213–314. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, H.S.; Prabhu, V.V.; Malhotra, K.P.; Srivastava, C. Helminthic Infections of the Central Nervous System. In A Review on Diverse Neurological Disorders; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 73–91.

- Díaz, A.; Casaravilla, C.; Irigoín, F.; Lin, G.; Previato, J.O.; Ferreira, F. Understanding the Laminated Layer of Larval Echinococcus I: Structure. Trends Parasitol 2011, 27, 204–213. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ye, J.-R.; Ma, H.-M.; Wu, J.-J.; Jiang, T.; Zheng, H. Role of Immune Tolerance in BALB/c Mice with Anaphylactic Shock after Echinococcus Granulosus Infection. Immunol Res 2016, 64, 233–241. [CrossRef]

- Gottstein, B.; Wang, J.; Blagosklonov, O.; Grenouillet, F.; Millon, L.; Vuitton, D.A.; Müller, N. Echinococcus Metacestode: In Search of Viability Markers. Parasite 2014, 21, 63. [CrossRef]

- Kern, P. Echinococcus Granulosus Infection: Clinical Presentation, Medical Treatment and Outcome. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2003, 388, 413–420. [CrossRef]

- Riganò, R.; Buttari, B.; Profumo, E.; Ortona, E.; Delunardo, F.; Margutti, P.; Mattei, V.; Teggi, A.; Sorice, M.; Siracusano, A. Echinococcus Granulosus Antigen B Impairs Human Dendritic Cell Differentiation and Polarizes Immature Dendritic Cell Maturation towards a Th2 Cell Response. Infect Immun 2007, 75, 1667–1678. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, W.; Cui, F.; Shi, C.; Gao, X.; Ouyang, J.; Wang, Y.; Nagai, A.; Zhao, W.; Yin, M.; et al. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Exert Immunosuppressive Function on the T Helper 2 in Mice Infected with Echinococcus Granulosus. Exp Parasitol 2020, 215, 107917. [CrossRef]

- Vatankhah, A.; Halász, J.; Piurkó, V.; Barbai, T.; Rásó, E.; Tímár, J. Characterization of the Inflammatory Cell Infiltrate and Expression of Costimulatory Molecules in Chronic Echinococcus Granulosus Infection of the Human Liver. BMC Infect Dis 2015, 15, 530. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, Á.; Barrios, A.A.; Grezzi, L.; Mouhape, C.; Jenkins, S.J.; Allen, J.E.; Casaravilla, C. Immunology of a Unique Biological Structure: The Echinococcus Laminated Layer. Protein Cell 2023, 14, 87–104. [CrossRef]

- Padayachy, L.C.; Dattatraya, M. Hydatid Disease (Echinococcus) of the Central Nervous System. Childs Nerv Syst 2018, 34, 1967–1971. [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Ma, Z.; Shi, Y.; Pang, X.; Yimingjiang, M.; Dang, Z.; Cui, W.; Lin, R.; Zhang, W. Comparison of Clinicopathological Features between Cerebral Cystic and Alveolar Echinococcosis: Analysis of 27 Cerebral Echinococcosis Cases in Xinjiang, China. Diagn Pathol 2024, 19, 90. [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, P.A.; Lees, R.F. Vertebral Hydatid Disease: Radiological Assessment. Radiology 1981, 140, 763–766. [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.F.; Douira-Khomsi, W.; Gharbi, H.; Sharma, M.; Cui, X.W.; Sparchez, Z.; Richter, J.; Kabaalioğlu, A.; Atkinson, N.S.; Schreiber-Dietrich, D.; et al. Cystic Echinococcosis, Review and Illustration of Non-Hepatic Manifestations. Med Ultrason 2020, 22, 319–324. [CrossRef]

- Gader, G.; Slimane, A.; Sliti, F.; Kherifech, M.; Belhaj, A.; Bouhoula, A.; Kallel, J. Hydatid Cyst of the Brainstem: The Rarest of the Rare Locations for Echinococcosis. Radiol Case Rep 2024, 19, 4422–4425. [CrossRef]

- Borni, M.; Abdelmouleh, S.; Taallah, M.; Blibeche, H.; Ayadi, A.; Boudawara, M.Z. A Case of Pediatric Primary Osteolytic Extradural and Complicated Hydatid Cyst Revealed by a Skull Vault Swelling. Childs Nerv Syst 2024, 40, 335–343. [CrossRef]

- Kharosekar, H.; Bhide, A.; Rathi, S.; Sawardekar, V. Primary Multiple Intracranial Extradural Hydatid Cysts: A Rare Entity Revisited. Asian J Neurosurg 2020, 15, 766–768. [CrossRef]

- Dalaqua, M.; do Nascimento, F.B.P.; Miura, L.K.; Garcia, M.R.T.; Barbosa Junior, A.A.; Reis, F. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Cranial Nerves in Infectious, Neoplastic, and Demyelinating Diseases, as Well as Other Inflammatory Diseases: A Pictorial Essay. Radiol Bras 2022, 55, 38–46. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, J.; He, Y.; Deng, Y.; Chen, J.; Fang, W.; Zeren, Z.; Liu, Y.; Abdulaziz, A.T.A.; Yan, B.; et al. Clinical Features, Radiological Characteristics, and Outcomes of Patients With Intracranial Alveolar Echinococcosis: A Case Series From Tibetan Areas of Sichuan Province, China. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 537565. [CrossRef]

- Copley, I.B.; Fripp, P.J.; Erasmus, A.M.; Otto, D.D. Unusual Presentations of Cerebral Hydatid Disease in Children. Br J Neurosurg 1992, 6, 203–210. [CrossRef]

- Diren, H.B.; Ozcanli, H.; Boluk, M.; Kilic, C. Unilocular Orbital, Cerebral and Intraventricular Hydatid Cysts: CT Diagnosis. Neuroradiology 1993, 35, 149–150. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Desai, K.; Goel, A. Intracranial Hydatid Cyst: A Report of Five Cases and Review of Literature. Neurol India 1999, 47, 214–217.

- Aydin, M.D.; Ozkan, U.; Altinörs, N. Quadruplets Hydatid Cysts in Brain Ventricles: A Case Report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2002, 104, 300–302. [CrossRef]

- Iyigun, O.; Uysal, S.; Sancak, R.; Hokelek, M.; Uyar, Y.; Bernay, F.; Ariturk, E. Multiple Organ Involvement Hydatid Cysts in a 2-Year-Old Boy. J Trop Pediatr 2004, 50, 374–376. [CrossRef]

- Bükte, Y.; Kemaloglu, S.; Nazaroglu, H.; Ozkan, U.; Ceviz, A.; Simsek, M. Cerebral Hydatid Disease: CT and MR Imaging Findings. Swiss Med Wkly 2004, 134, 459–467. [CrossRef]

- Evliyaoğlu, C.; Keskil, S. Possible Spontaneous “Birth” of a Hydatid Cyst into the Lateral Ventricle. Childs Nerv Syst 2005, 21, 425–428. [CrossRef]

- Maurya, P.; Singh, V.; Prasad, R.; Bhaikhel, K.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, M. Intraventricular Hydatid Cyst Causing Entrapped Temporal Horn Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Journal of Pediatric Neurosciences 2007, 2, 20–22.

- Guzel, A.; Tatli, M.; Maciaczyk, J.; Altinors, N. Primary Cerebral Intraventricular Hydatid Cyst: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Child Neurol 2008, 23, 585–588. [CrossRef]

- Kamali, N.I.; Huda, M.F.; Srivastava, V.K. Intraventricular Hydatid Cyst Causing Entrapped Temporal Horn Syndrome: Case Report and Review of Literature. Trop Parasitol 2011, 1, 113–115. [CrossRef]

- Sanlı, A.M.; Türkoğlu, E.; Kertmen, H.; Gürer, B. Hydatid Cyst of the Ambient Cistern Radiologically Mimicking an Arachnoid Cyst. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2012, 10, 186–188. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Singh, K.; Sharma, V. Primary Intracranial Hydatid Cysts: Review of Ten Cases. World J Surg Res 2013, 4, 12–18.

- Pandey, S.; Pandey, D.; Shende, N.; Sahu, A.; Sharma, V. Cerebral Intraventricular Echinococcosis in an Adult. Surg Neurol Int 2015, 6, 138. [CrossRef]

- Qadri, S.K.; Hamdani, N.H.; Bhat, A.R.; Lone, M.I. Unusual Presentation of an Intraventricular Hydatid Cyst as a Bleeding Cystic Tumor: A Case Report and Brief Review. Asian J Neurosurg 2017, 12, 324–327. [CrossRef]

- Sadashiva, N.; Shukla, D.; Devi, B.I. Rupture of Intraventricular Hydatid Cyst: Camalote Sign. World Neurosurg 2018, 110, 115–116. [CrossRef]

- Samadian, M.; Mousavinejad, S.A.; Jabbari, A.; Tavassol, H.H.; Karimi, P.; Almagro, K.; Rezaei, O.; Borghei-Razavi, H. Third Ventricle Hydatid Cyst: A Rare Case Report and Review of the Literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2020, 198, 106218. [CrossRef]

- Maamri, K.; Cherif, I.; Trifa, A.; Nessib, N.; Elkahla, G.; Darmoul, M. Hydatid Cyst in the Third Ventricle of the Brain: Case Report of an Exceptionally Rare Condition. Childs Nerv Syst 2022, 38, 1637–1641. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lv, S.; Zhang, S. Different Protein of Echinococcus Granulosus Stimulates Dendritic Induced Immune Response. Parasitology 2015, 142, 879–889. [CrossRef]

- Stefaniak, J. Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy in the Differential Diagnosis of the Liver Cystic Echinococcosis. Acta Trop 1997, 67, 107–111. [CrossRef]

- Deplazes, P.; Alther, P.; Tanner, I.; Thompson, R.C.; Eckert, J. Echinococcus Multilocularis Coproantigen Detection by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay in Fox, Dog, and Cat Populations. J Parasitol 1999, 85, 115–121.

- Koziol, U.; Krohne, G.; Brehm, K. Anatomy and Development of the Larval Nervous System in Echinococcus Multilocularis. Frontiers in zoology 2013, 10, 1–17.

- Kammerer, W.S. Echinococcosis Affecting the Central Nervous System.; © 1993 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 1993; Vol. 13, pp. 144–147.

- McManus, D.P.; Gray, D.J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Echinococcosis. BMJ 2012, 344, e3866. [CrossRef]

- Auer, H.; Stöckl, C.; Suhendra, S.; Schneider, R. [Sensitivity and specificity of new commercial tests for the detection of specific Echinococcus antibodies]. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2009, 121 Suppl 3, 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Taxy, J.B.; Gibson, W.E.; Kaufman, M.W. Echinococcosis: Unexpected Occurrence and the Diagnostic Contribution of Routine Histopathology. Am J Surg Pathol 2017, 41, 94–100. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Xiong, X.; Li, L.; Li, H. Imaging Diagnostic Criteria of Hepatic Echinococcosis in China. Radiology of Infectious Diseases 2020, 7, 35–42.

- Finsterer, J.; Auer, H. Parasitoses of the Human Central Nervous System. J Helminthol 2013, 87, 257–270. [CrossRef]

- Arana, E.; Latorre, F.F.; Revert, A.; Menor, F.; Riesgo, P.; Liaño, F.; Diaz, C. Intradiploic Epidermoid Cysts. Neuroradiology 1996, 38, 306–311. [CrossRef]

- El-On, J. Benzimidazole Treatment of Cystic Echinococcosis. Acta Trop 2003, 85, 243–252. [CrossRef]

- Buttenschoen, K.; Carli Buttenschoen, D. Echinococcus Granulosus Infection: The Challenge of Surgical Treatment. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2003, 388, 218–230. [CrossRef]

- Neumayr, A.; Troia, G.; de Bernardis, C.; Tamarozzi, F.; Goblirsch, S.; Piccoli, L.; Hatz, C.; Filice, C.; Brunetti, E. Justified Concern or Exaggerated Fear: The Risk of Anaphylaxis in Percutaneous Treatment of Cystic Echinococcosis-a Systematic Literature Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011, 5, e1154. [CrossRef]

- Diem, S.; Gottstein, B.; Beldi, G.; Semmo, N.; Diem, L.F. Accelerated Course of Alveolar Echinococcosis After Treatment With Steroids in a Patient With Autoimmune Encephalitis. Cureus 2021, 13, e18831. [CrossRef]

- Smego, R.A., Jr.; Bhatti, S.; Khaliq, A.A.; Beg, M.A. Percutaneous Aspiration-Injection-Reaspiration Drainage Plus Albendazole or Mebendazole for Hepatic Cystic Echinococcosis: A Meta-Analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2003, 37, 1073–1083. [CrossRef]

- Raether, W.; Hänel, H. Epidemiology, Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis of Zoonotic Cestode Infections: An Update. Parasitol Res 2003, 91, 412–438. [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, D.; Gavra, M.; Stranjalis, G.; Boviatsis, E.; Korfias, S.; Karydakis, P.; Tmemistocleous, M. Echinococcus Infestation of the Central Nervous System as the Primary and Solitary Manifestation of the Disease: Case Report and Literature Review. Medical Research Archives 2023, 11.

- Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Han, X.; Li, J.; Tian, M.; Qi, W.; An, H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Han, S.; et al. Oral Delivery of Anti-Parasitic Agent-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles: Enhanced Liver Targeting and Improved Therapeutic Effect on Hepatic Alveolar Echinococcosis. Int J Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 3069–3085. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Pang, H.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, T.; Mo, X.; Yang, S.; Cai, Y.; Lu, Y. RESEARCH ARTICLE Advances in the Study of Molecular Identification Technology of Echinococcus Species. Tropical Biomedicine 2022, 39, 434–443.

- Shi, C.; Zhou, X.; Yang, W.; Wu, J.; Bai, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yang, H.; Nagai, A.; Yin, M.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles From Mice With Echinococcus Granulosus at Different Infection Stages and Their Immunomodulatory Functions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 805010. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Peng, X.; Ma, L.; Tian, Q.; Wu, S.; Li, J.; Ling, J.; Lv, W.; Ding, B.; Tan, J.; et al. Targeted Sequencing of Genomic Repeat Regions Detects Circulating Cell-Free Echinococcus DNA. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, e0008147. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).