Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

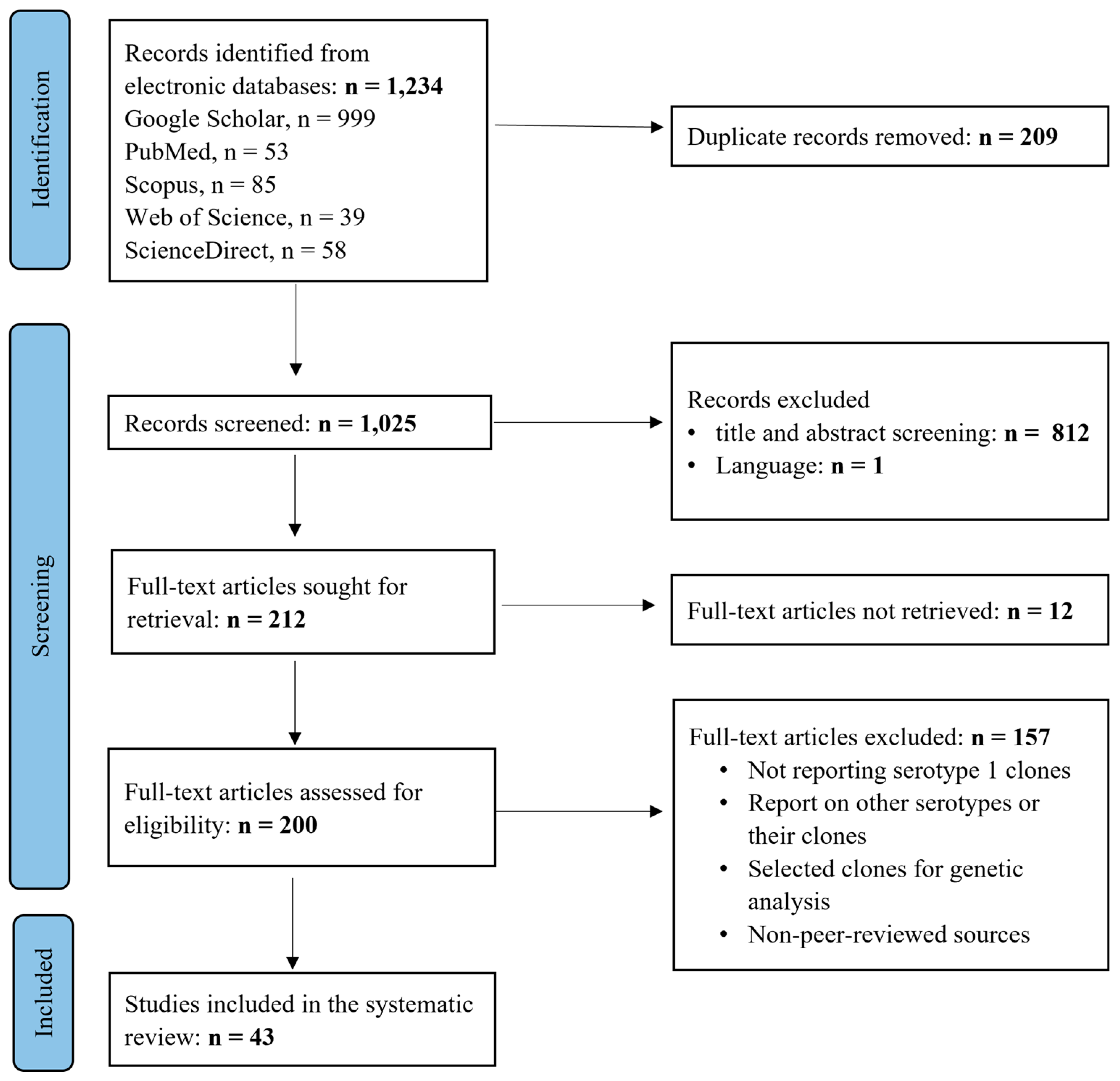

2.1. Search Results and Selection Process

2.2. Description of Included Studies

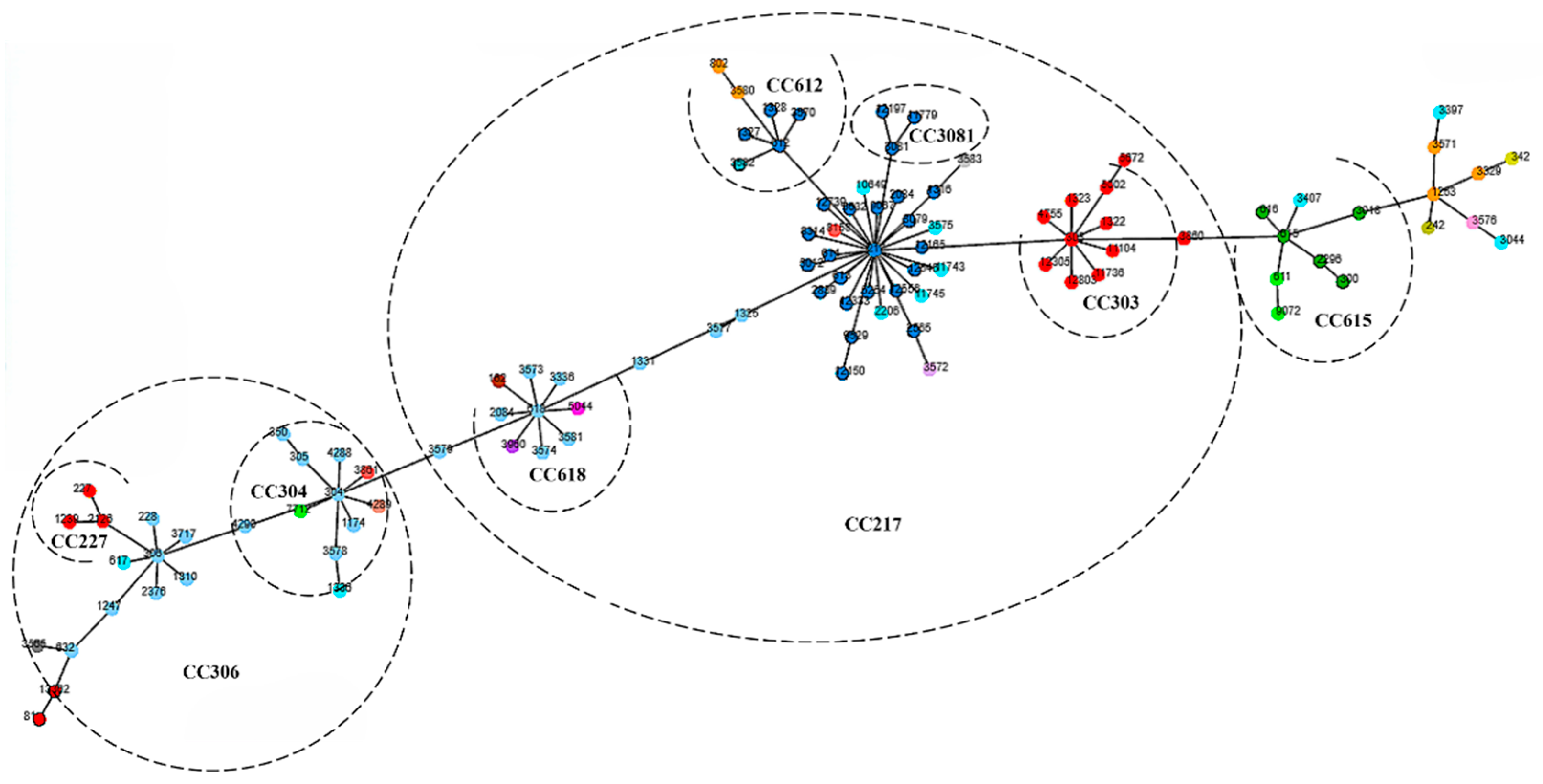

2.3. Pneumococcal Serotype 1 Clones Reported Worldwide

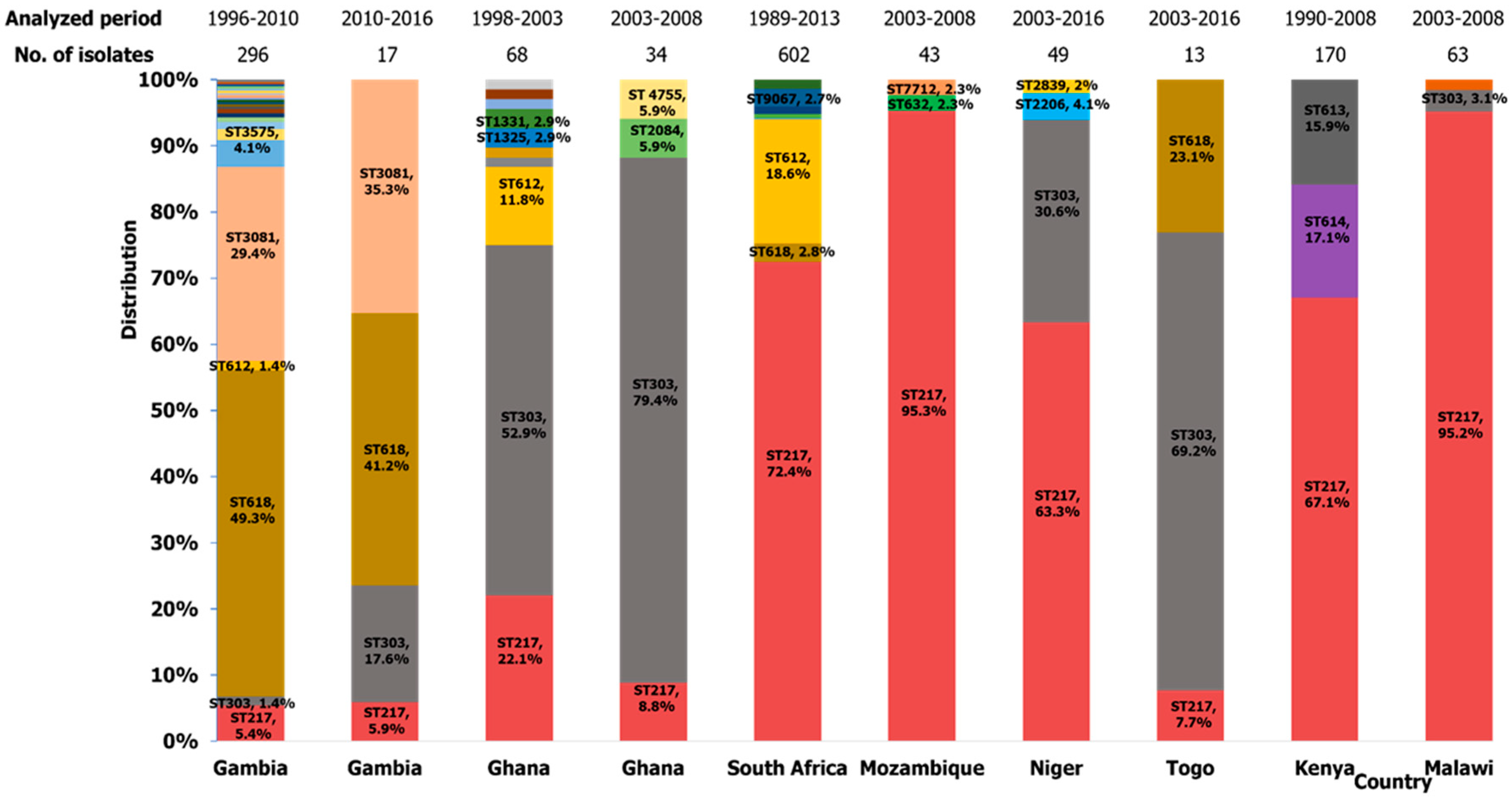

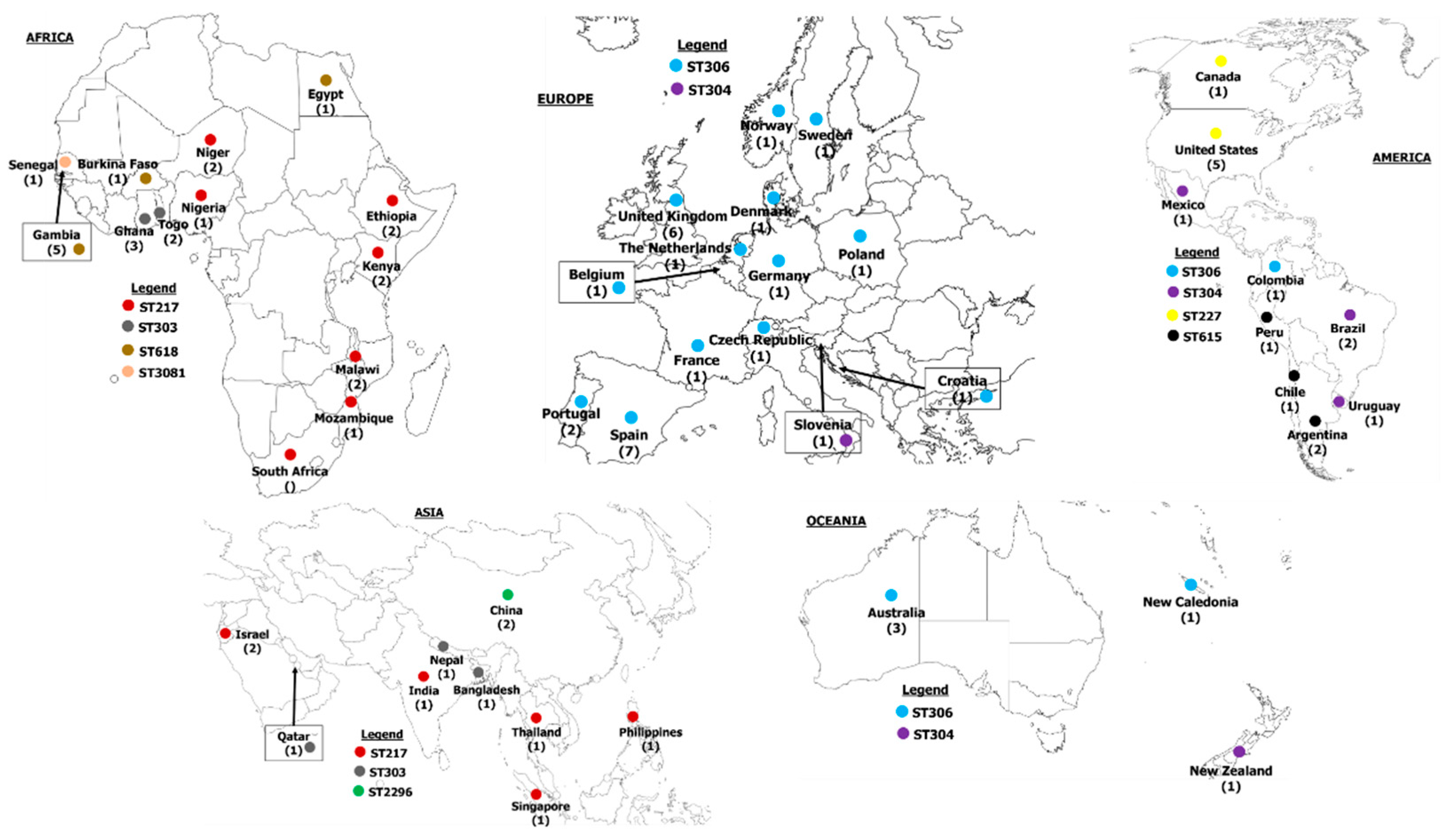

2.3.1. Africa

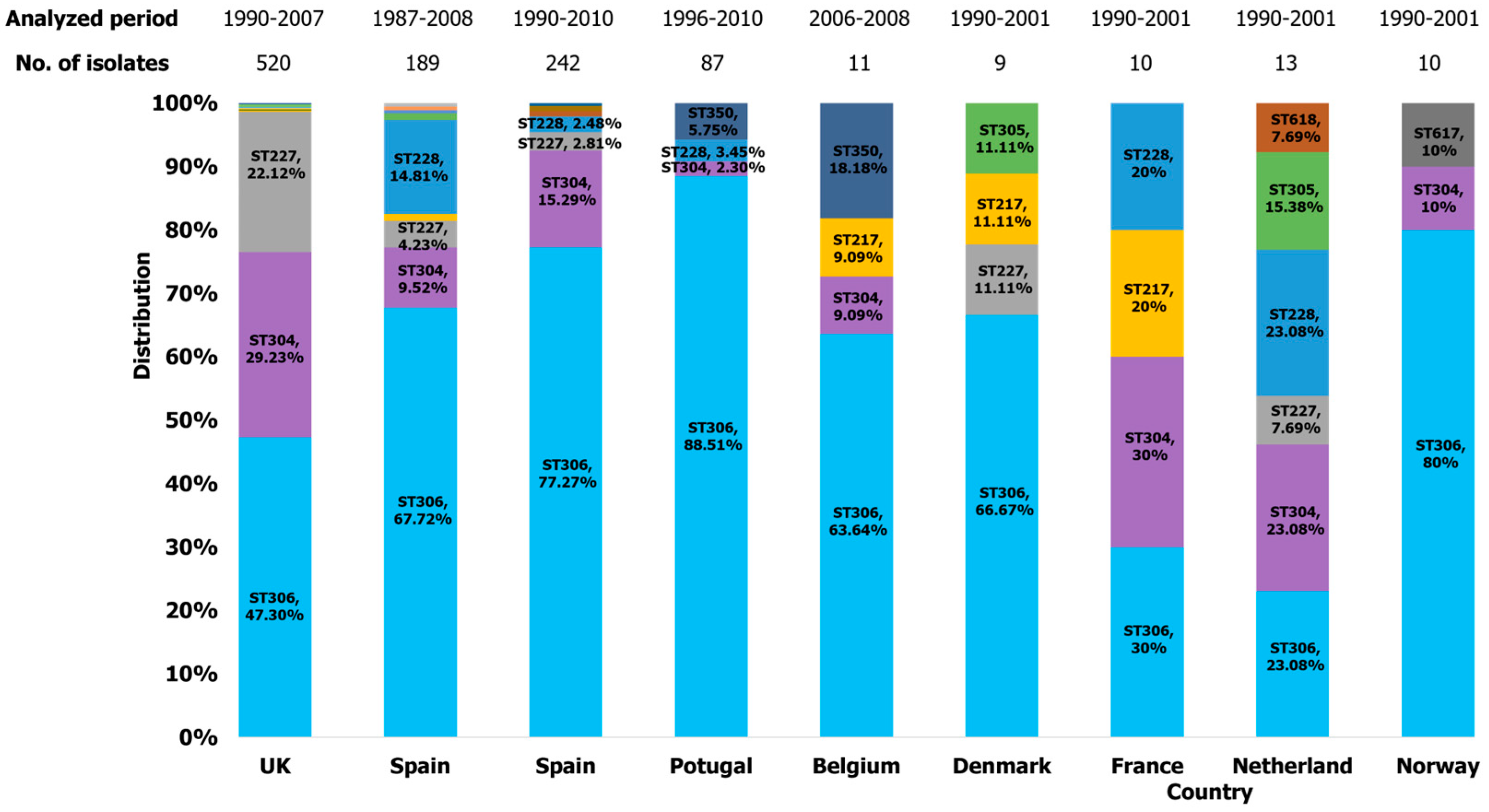

2.3.2. Europe

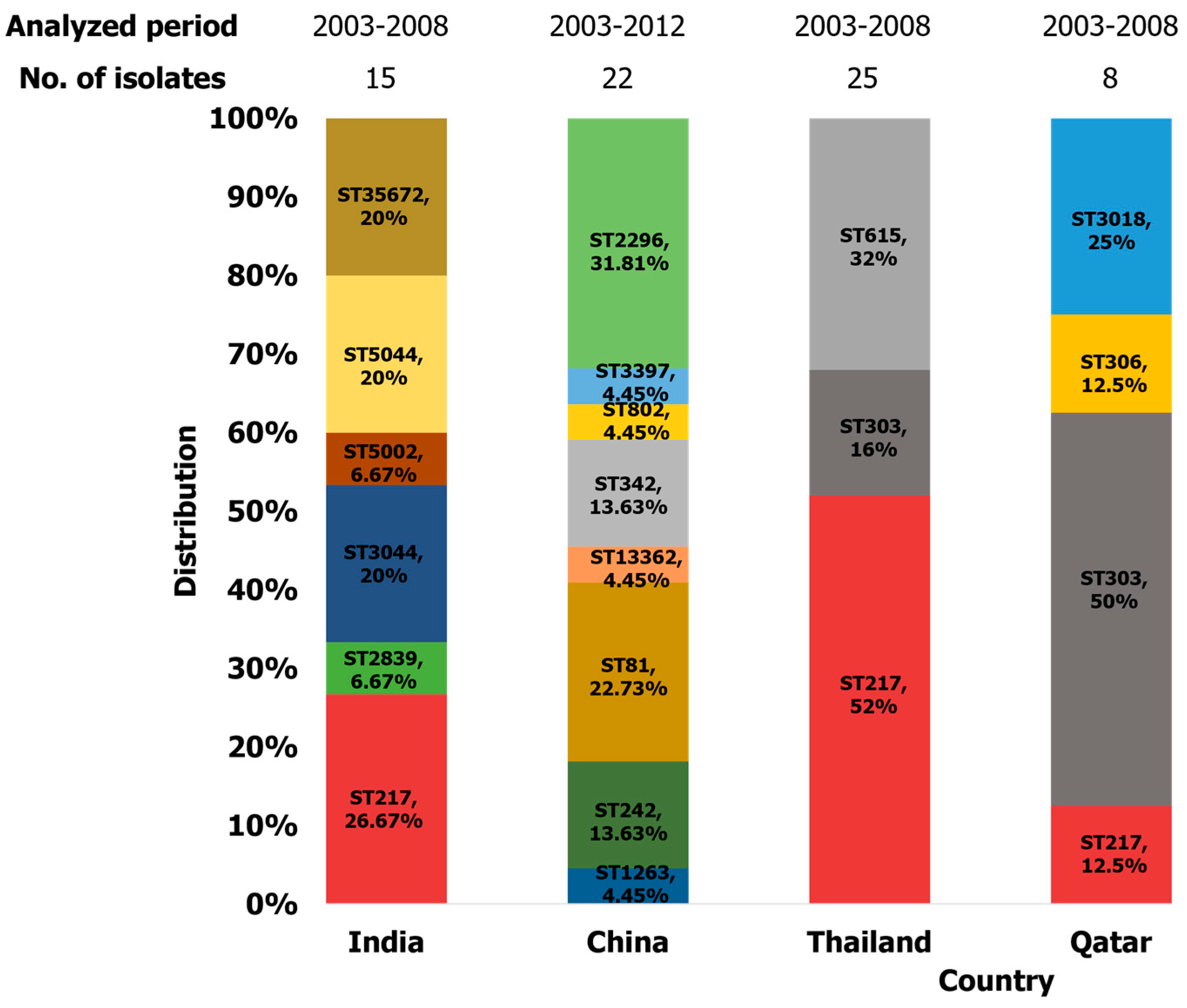

2.3.3. Asia

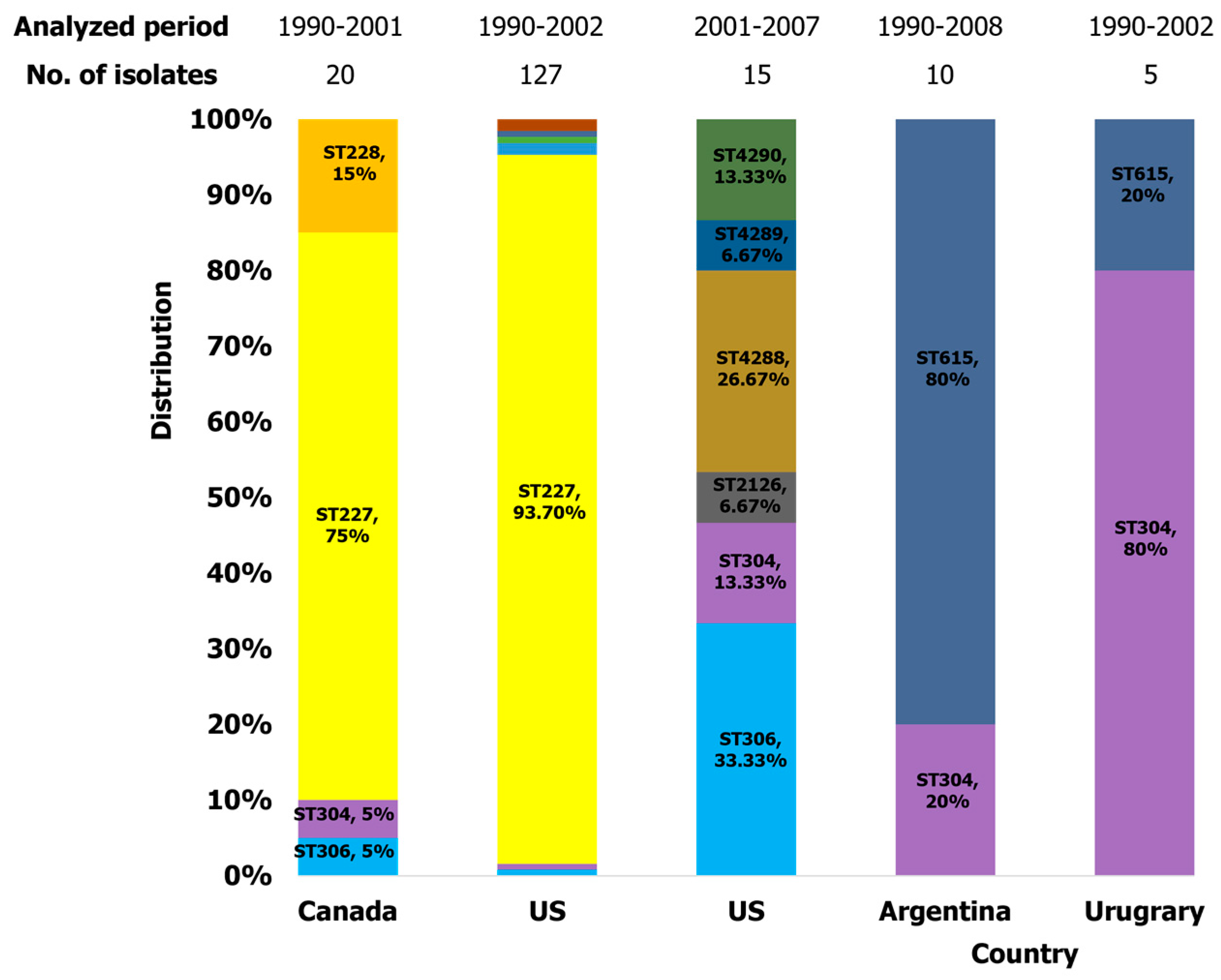

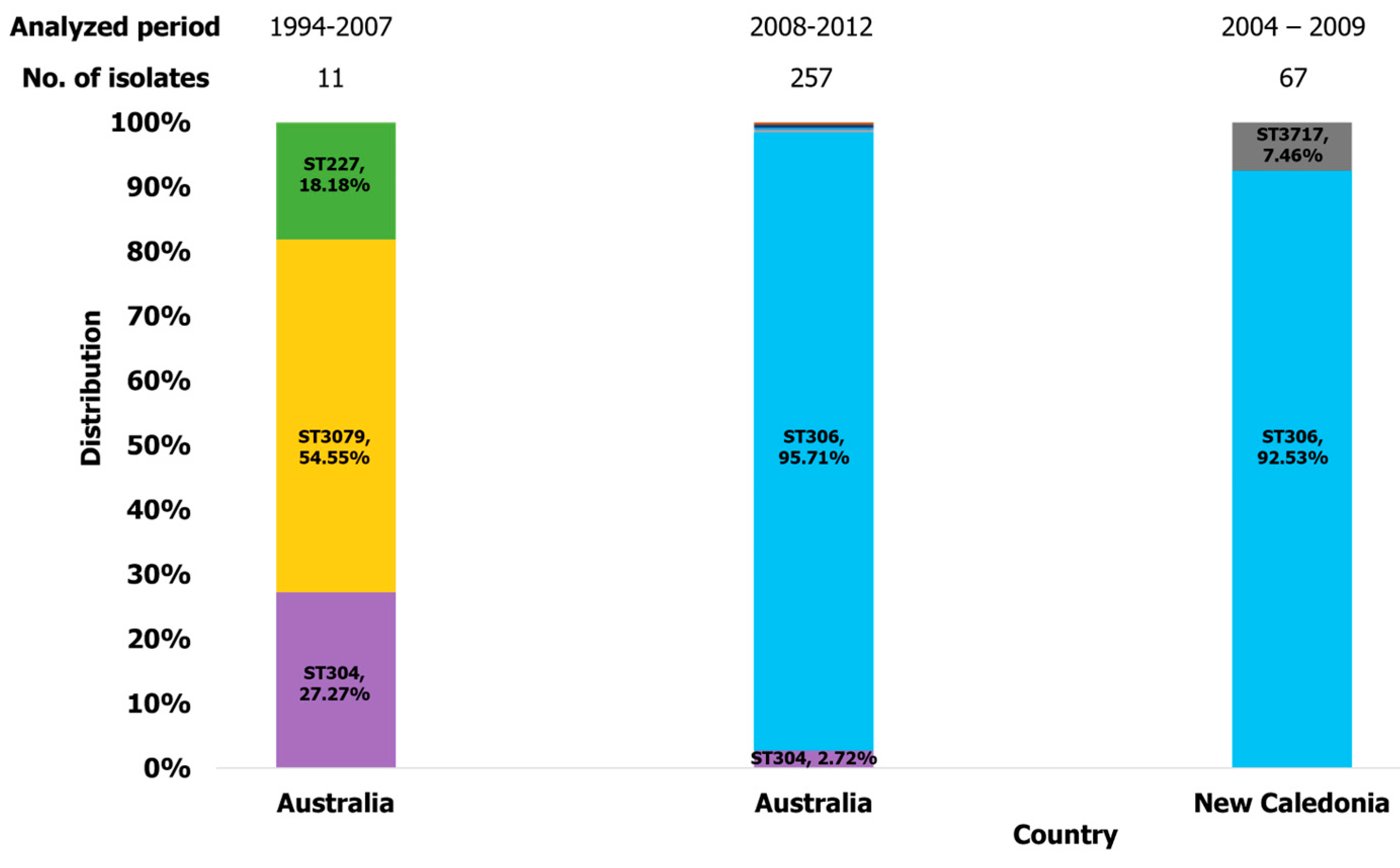

2.3.4. Americas

2.3.5. Oceania

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Literature Search Strategy and Selection Process

4.2. Eligibility Criteria

4.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

4.4. BURST Cluster Analysis

4.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Availability of data and materials

Consent for publication

References

- Bogaert, D.; De Groot, R.; Hermans, P.W.M. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonisation: the key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004 Mar;4(3):144–54.

- Løchen, A.; Croucher, N.J.; Anderson, R.M. Divergent serotype replacement trends and increasing diversity in pneumococcal disease in high income settings reduce the benefit of expanding vaccine valency. Sci Rep. 2020 Nov 4;10(1):18977.

- Lynch, J.P.; Zhanel, G.G. Streptococcus pneumoniae: epidemiology, risk factors, and strategies for prevention. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 Apr;30(2):189–209.

- O’Brien, K.L.; Wolfson, L.J.; Watt, J.P.; Henkle, E.; Deloria-Knoll, M.; McCall, N. , et al. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet Lond Engl. 2009 Sep 12;374(9693):893–902.

- von Mollendorf, C.; von Gottberg, A.; Tempia, S.; Meiring, S.; de Gouveia, L.; Quan, V. , et al. Increased risk for and mortality from invasive pneumococcal disease in HIV-exposed but uninfected infants aged .

- CDC Pneumococcal Disease Surveillance and Trends [Internet]. Pneumococcal Disease. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 3]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/php/surveillance/index.html.

- Lynch, J.P.; Zhanel, G.G. Streptococcus pneumoniae: epidemiology and risk factors, evolution of antimicrobial resistance, and impact of vaccines. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010 May;16(3):217–25.

- Ganaie, F.; Saad, J.S.; McGee, L.; van Tonder, A.J.; Bentley, S.D.; Lo, S.W. , et al. A New Pneumococcal Capsule Type, 10D, is the 100th Serotype and Has a Large cps Fragment from an Oral Streptococcus. mBio. 2020 May 19;11(3):e00937-20.

- Brueggemann, A.B.; Griffiths, D.T.; Meats, E.; Peto, T.; Crook, D.W.; Spratt, B.G. Clonal relationships between invasive and carriage Streptococcus pneumoniae and serotype- and clone-specific differences in invasive disease potential. J Infect Dis. 2003 May 1;187(9):1424–32.

- Chaguza, C.; Yang, M.; Jacques, L.C.; Bentley, S.D.; Kadioglu, A. Serotype 1 pneumococcus: epidemiology, genomics, and disease mechanisms. Trends Microbiol. 2022 Jun 1;30(6):581–92.

- Rayner, R.E.; Savill, J.; Hafner, L.M.; Huygens, F. Genotyping Streptococcus pneumoniae. Future Microbiol. 2015;10(4):653–64.

- Horn, E.K.; Wasserman, M.D.; Hall-Murray, C.; Sings, H.L.; Chapman, R.; Farkouh, R.A. Public health impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination: a review of measurement challenges. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021 Oct 3;20(10):1291–309.

- Mackenzie, G.A.; Hill, P.C.; Jeffries, D.J.; Ndiaye, M.; Sahito, S.M.; Hossain, I. , et al. Impact of the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia in The Gambia: 10 years of population-based surveillance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 1;21(9):1293–302.

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. , et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ. 2021 Mar 29;372:n160.

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016 Dec 5;5(1):210.

- Jolley, K.A.; Bray, J.E.; Maiden, M.C.J. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:124.

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. , et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008 Apr;61(4):344–9.

- Sanderson, S.; Tatt, I.D.; Higgins, J.P.T. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007 Jun;36(3):666–76.

- Byington, C.; Hulten, K.G.; Ampofo, K.; Shen, X.; At, P.; Aj, B. , et al. Molecular epidemiology of pediatric pneumococcal empyema from 2001 to 2007 in Utah. J Clin Microbiol [Internet]. 2010 Feb [cited 2024 Nov 4];48(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20018815/.

- Chaguza, C.; Yang, M.; Cornick, J.E.; du Plessis, M.; Gladstone, R.A.; Ba, K.A. , et al. Bacterial genome-wide association study of hyper-virulent pneumococcal serotype 1 identifies genetic variation associated with neurotropism. Commun Biol [Internet]. 2020 Oct 8 [cited 2024 Nov 4];3(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33033372/.

- Hanachi, M.; Kiran, A.M.; Cornick, J.E.; Harigua-Souiai, E.; Everett, D.; Benkahla, A. , et al. Genomic Characteristics of Invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae Serotype 1 in New Caledonia Prior to the Introduction of PCV13. Bioinforma Biol Insights [Internet]. 2020 Sep 29 [cited 2024 Nov 4];14. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33088176/.

- Almeida, S.; de Lencastre, H.; Sá-Leão, R. Epidemiology and population structure of serotypes 1, 5 and 7f carried by children in Portugal from 1996-2010 before introduction of the 10-valent and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. PloS One [Internet]. 2013 Sep 18 [cited 2024 Nov 4];8(9). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24058686/.

- Esteva, C.; Selva, L.; de Sevilla, M.F.; Garcia-Garcia, J.J.; Pallares, R.; Muñoz-Almagro, C. Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 1 causing invasive disease among children in Barcelona over a 20-year period (1989-2008). Clin Microbiol Infect Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis [Internet]. 2011 Sep [cited 2024 Nov 4];17(9). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21729192/.

- Marimon, J.M.; Ercibengoa, M.; Alonso, M.; Zubizarreta, M.; Pérez-Trallero, E. Clonal structure and 21-year evolution of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 1 isolates in northern Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis [Internet]. 2009 Sep [cited 2024 Nov 4];15(9). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19702591/.

- Antonio, M.; Hakeem, I.; Awine, T.; Secka, O.; Sankareh, K.; Nsekpong, D. , et al. Seasonality and outbreak of a predominant Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 1 clone from The Gambia: expansion of ST217 hypervirulent clonal complex in West Africa. BMC Microbiol. 2008 Nov 17;8:198.

- Gonzalez, B.E.; Hulten, K.G.; Kaplan, S.L.; Mason, E.O. US Pediatric Multicenter Pneumococcal Surveillance Study Group. Clonality of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 1 isolates from pediatric patients in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2004 Jun;42(6):2810–2.

- Brueggemann, A.B.; Spratt, B.G. Geographic distribution and clonal diversity of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 1 isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2003 Nov;41(11):4966–70.

- Jourdain, S.; Drèze, P.A.; Verhaegen, J.; Van Melderen, L.; Smeesters, P.R. Carriage-associated Streptocccus pneumoniae serotype 1 in Brussels, Belgium. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 Jan;32(1):86–7.

- Horácio, A.N.; Silva-Costa, C.; Diamantino-Miranda, J.; Lopes, J.P.; Ramirez, M.; Melo-Cristino, J. , et al. Population Structure of Streptococcus pneumoniae Causing Invasive Disease in Adults in Portugal before PCV13 Availability for Adults: 2008-2011. PloS One. 2016;11(5):e0153602.

- Smith-Vaughan, H.; Marsh, R.; Mackenzie, G.; Fisher, J.; Morris, P.S.; K, H.; et al. Age-specific cluster of cases of serotype 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage in remote indigenous communities in Australia. Clin Vaccine Immunol CVI [Internet]. 2009 Feb [cited 2024 Nov 4];16(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19091995/.

- Jauneikaite, E.; Jefferies, J.M.; Churton, W.V.; Lin, R.P.T.; Hibberd, M.L.; Clarke, C.S. Genetic diversity of Streptococcus pneumoniae causing meningitis and sepsis in Singapore during the first year of PCV7 implementation. Emerg Microbes Infect [Internet]. 2014 Jun [cited 2024 Nov 4];3(6). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26038742/.

- Kwambana-Adams, B.A.; Asiedu-Bekoe, F.; Sarkodie, B.; Afreh, O.K.; Kuma, G.K.; Owusu-Okyere, G. , et al. An outbreak of pneumococcal meningitis among older children (≥5 years) and adults after the implementation of an infant vaccination programme with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Ghana. BMC Infect Dis. 2016 Oct 18;16(1):575.

- Leimkugel, J.; Adams Forgor, A.; Gagneux, S.; Pflüger, V.; Flierl, C.; Awine, E. , et al. An outbreak of serotype 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis in northern Ghana with features that are characteristic of Neisseria meningitidis meningitis epidemics. J Infect Dis. 2005 Jul 15;192(2):192–9.

- Lai, J.Y.; Cook, H.; Yip, T.W.; Berthelsen, J.; Gourley, S.; Krause, V. , et al. Surveillance of pneumococcal serotype 1 carriage during an outbreak of serotype 1 invasive pneumococcal disease in central Australia 2010-2012. BMC Infect Dis. 2013 Sep 3;13:409.

- Ebruke, C.; Roca, A.; Egere, U.; Darboe, O.; Hill, P.C.; Greenwood, B. , et al. Temporal changes in nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 1 genotypes in healthy Gambians before and after the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. PeerJ. 2015;3:e903.

- Kirkham, L.A.S.; Jefferies, J.M.C.; Kerr, A.R.; Jing, Y.; Clarke, S.C.; Smith, A. , et al. Identification of Invasive Serotype 1 Pneumococcal Isolates That Express Nonhemolytic Pneumolysin. J Clin Microbiol. 2006 Jan;44(1):151.

- Staples, M.; Graham, R.M.A.; Jennison, A.V.; Ariotti, L.; Hicks, V.; Cook, H. , et al. Molecular characterization of an Australian serotype 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae outbreak. Epidemiol Infect. 2015 Jan;143(2):325–33.

- Zhou, H.; Guo, J.; Qin, T.; Ren, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C. , et al. Serotype and MLST-based inference of population structure of clinical Streptococcus pneumoniae from invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal disease. Infect Genet Evol J Mol Epidemiol Evol Genet Infect Dis. 2017 Nov;55:104–11.

- du Plessis, M.; Allam, M.; Tempia, S.; Wolter, N.; de Gouveia, L.; von Mollendorf, C. , et al. Phylogenetic Analysis of Invasive Serotype 1 Pneumococcus in South Africa, 1989 to 2013. J Clin Microbiol. 2016 May;54(5):1326–34.

- Brueggemann, A.B.; Muroki, B.M.; Kulohoma, B.W.; Karani, A.; Wanjiru, E.; Morpeth, S. , et al. Population genetic structure of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Kilifi, Kenya, prior to the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. PloS One. 2013;8(11):e81539.

- Donkor, E.S.; Adegbola, R.A.; Wren, B.W.; Antonio, M. Population biology of Streptococcus pneumoniae in West Africa: multilocus sequence typing of serotypes that exhibit different predisposition to invasive disease and carriage. PloS One. 2013;8(1):e53925.

- Zemlicková, H.; Crisóstomo, M.I.; Brandileone, M.C.; Camou, T.; Castañeda, E.; Corso, A. , et al. Serotypes and clonal types of penicillin-susceptible streptococcus pneumoniae causing invasive disease in children in five Latin American countries. Microb Drug Resist Larchmt N. 2005;11(3):195–204.

- Muñoz-Almagro, C.; Ciruela, P.; Esteva, C.; Marco, F.; Navarro, M.; Bartolome, R. , et al. Serotypes and clones causing invasive pneumococcal disease before the use of new conjugate vaccines in Catalonia, Spain. J Infect. 2011 Aug;63(2):151–62.

- Cooke, B.; Smith, A.; Diggle, M.; Lamb, K.; Robertson, C.; Inverarity, D. , et al. Antibiotic resistance in invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates identified in Scotland between 1999 and 2007. J Med Microbiol. 2010 Oct;59(Pt 10):1212–8.

- Clarke, S.C.; Jefferies, J.M.C.; Smith, A.J.; McMenamin, J.; Mitchell, T.J.; Edwards, G.F.S. Pneumococci causing invasive disease in children prior to the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Scotland. J Med Microbiol. 2006 Aug;55(Pt 8):1079–84.

- Muñoz-Almagro, C.; Jordan, I.; Gene, A.; Latorre, C.; Garcia-Garcia, J.J.; Pallares, R. Emergence of invasive pneumococcal disease caused by nonvaccine serotypes in the era of 7-valent conjugate vaccine. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2008 Jan 15;46(2):174–82.

- Beall, B.; McEllistrem, M.C.; Gertz, R.E.; Wedel, S.; Boxrud, D.J.; Gonzalez, A.L. , et al. Pre- and postvaccination clonal compositions of invasive pneumococcal serotypes for isolates collected in the United States in 1999, 2001, and 2002. J Clin Microbiol. 2006 Mar;44(3):999–1017.

- Antonio, M.; Dada-Adegbola, H.; Biney, E.; Awine, T.; O’Callaghan, J.; Pfluger, V. , et al. Molecular epidemiology of pneumococci obtained from Gambian children aged 2-29 months with invasive pneumococcal disease during a trial of a 9-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. BMC Infect Dis. 2008 Jun 11;8:81.

- Yaro, S.; Lourd, M.; Traoré, Y.; Njanpop-Lafourcade, B.M.; Sawadogo, A.; Sangare, L. , et al. Epidemiological and molecular characteristics of a highly lethal pneumococcal meningitis epidemic in Burkina Faso. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2006 Sep 15;43(6):693–700.

- Zähner, D.; Gudlavalleti, A.; Stephens, D.S. Increase in Pilus Islet 2–encoded Pili among Streptococcus pneumoniae Isolates, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010 Jun;16(6):955.

- Grau, I.; Ardanuy, C.; Calatayud, L.; Rolo, D.; Domenech, A.; Liñares, J. , et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease in healthy adults: increase of empyema associated with the clonal-type Sweden(1)-ST306. PloS One. 2012;7(8):e42595.

- Kourna Hama, M.; Khan, D.; Laouali, B.; Okoi, C.; Yam, A.; Haladou, M. , et al. Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis Surveillance in Niger: Increased Importance of Neisseria meningitidis Serogroup C, and a Decrease in Streptococcus pneumoniae Following 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Introduction. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2019 Sep 5;69(Suppl 2):S133–9.

- Jefferies, J.M.; Smith, A.J.; Edwards, G.F.S.; McMenamin, J.; Mitchell, T.J.; Clarke, S.C. Temporal analysis of invasive pneumococcal clones from Scotland illustrates fluctuations in diversity of serotype and genotype in the absence of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. J Clin Microbiol. 2010 Jan;48(1):87–96.

- Porat, N.; Benisty, R.; Trefler, R.; Givon-Lavi, N.; Dagan, R. Clonal distribution of common pneumococcal serotypes not included in the 7-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV7): marked differences between two ethnic populations in southern Israel. J Clin Microbiol. 2012 Nov;50(11):3472–7.

- Foster, D.; Knox, K.; Walker, A.S.; Griffiths, D.T.; Moore, H.; Haworth, E. , et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease: epidemiology in children and adults prior to implementation of the conjugate vaccine in the Oxfordshire region, England. J Med Microbiol. 2008 Apr;57(Pt 4):480–7.

- Chaguza, C.; Cornick, J.E.; Andam, C.P.; Gladstone, R.A.; Alaerts, M.; Musicha, P. , et al. Population genetic structure, antibiotic resistance, capsule switching and evolution of invasive pneumococci before conjugate vaccination in Malawi. Vaccine. 2017 Aug 16;35(35 Pt B):4594–602.

- Sanneh, B.; Okoi, C.; Grey-Johnson, M.; Bah-Camara, H.; Kunta Fofana, B.; Baldeh, I. , et al. Declining Trends of Pneumococcal Meningitis in Gambian Children After the Introduction of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2019 Sep 5;69(Suppl 2):S126–32.

- Tsolenyanu, E.; Bancroft, R.E.; Sesay, A.K.; Senghore, M.; Fiawoo, M.; Akolly, D. , et al. Etiology of Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis Pre- and Post-PCV13 Introduction Among Children Under 5 Years Old in Lomé, Togo. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2019 Sep 5;69(Suppl 2):S97–104.

- Sharew, B.; Moges, F.; Yismaw, G.; Mihret, A.; Lobie, T.A.; Abebe, W. , et al. Molecular epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates causing invasive and noninvasive infection in Ethiopia. Sci Rep. 2024 Sep 13;14(1):21409.

- Serrano, I.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Carriço, J.A.; Ramirez, M. Characterization of the genetic lineages responsible for pneumococcal invasive disease in Portugal. J Clin Microbiol. 2005 Apr;43(4):1706–15.

- Cornick, J.E.; Chaguza, C.; Harris, S.R.; Yalcin, F.; Senghore, M.; Kiran, A.M. , et al. Region-specific diversification of the highly virulent serotype 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Genomics. 2015 Aug;1(2):e000027.

- Chaguza, C.; Cornick, J.E.; Harris, S.R.; Andam, C.P.; Bricio-Moreno, L.; Yang, M. , et al. Understanding pneumococcal serotype 1 biology through population genomic analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2016 Nov 8;16(1):649.

| Author, year (ref) | Country | Year of study | Study population | Study group | Isolate type | No. of S. Pneumoniae serotype 1 | Molecular identification method | Genotyping tools | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLST | WGS | ||||||||

| Byington et al., 2010 [19] | United States | 2001 - 2007 | Children with Pediatric pneumococcal empyema | Children | IPD | 17 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Chaguza et al., 2020 [20] | sub-Saharan Africa | 1996 - 2016 | Invasive pneumococcal serotype 1 isolates from sub-Saharan Africa | All ages | IPD | 909 | Whole genome sequencing | √ | √ |

| Hanachi et al., 2020 [21] | New Caledonia | 2004 - 2009 | Pneumococcal serotype 1 samples | Unspecified | IPD & NIPD | 67 | Whole genome sequencing | √ | √ |

| Almeida et al., 2013 [22] | Portugal | 1996 - 2010 | Healthy children attending day care | Children | Carriage | 21 | PCR | √ | |

| Esteva et al., 2011 [23] | Spain | 1989 - 2008 | Children with IPD | Children | IPD | 56 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Marimon et al., 2009 [24] | Spain | 1987 - 2007 | Pneumococcal serotype 1 samples | All ages | IPD & NIPD | 135 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Antonio et al., 2008 [25] | Gambia | 1996 - 2006 | Healthy Gambians and IPD cases | All ages | IPD & Carriage | 163 | PCR | √ | |

| Gonzalez et al., 2004 [26] | United States | 1993 - 2002 | Pediatric patients | Children | IPD & NIPD | 55 | Rep-PCR | √ | |

| Brueggemann & Spratt, 2003 [27] | Multicenter | 1990 - 2001 | Serotype 1 IPD isolates | All ages | IPD | 166 | PCR | √ | |

| Jourdian et al., 2013 [28] | Belgium | 2006 - 2008 | Nursery school children | Children, 3 - 6 years | Carriage | 11 | PCR | √ | |

| Horacia et al., 2016 [29] | Portugal | 2008 - 2011 | Adult patients with IPD | Adults, 18 years and above | IPD | 66 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Smith-Vaughan et al., 2009 [30] | Australia | 1992 - 2007 | Individuals in remote Indigenous communities in Australia | All ages | IPD & Carriage | 26 | PCR | √ | |

| Jauneikaite et al., 2014 [31] | Singapore | 2009 - 2010 | IPD cases | Unspecified | IPD | 4 | PCR | √ | |

| Kwambana-Adams et al., 2016 [32] | Ghana | Cases of suspected meningitis | All ages | IPD | 38 | Triplex qPCR | √ | ||

| Leimkugel et al., 2005 [33] | Ghana | 1998 - 2003 | Patients with suspected meningitis | All ages | IPD | 58 | PCR | √ | |

| Lai et al., 2013 [34] | Australia | 2010 - 2012 | participants presenting to or visiting the Alice Springs Hospital Emergency Department | All ages, 1 - 77 years | Carriage | 4 | multiplex PCR | √ | |

| Ebruke et al., 2015 [35] | Gambia | 2003 - 2004 | Healthy Gambians | All ages | Carriage | 81 | multiplex PCR | √ | |

| Kirkham et al., 2006 [36] | United Kingdom | 2000 - 2004 | Serotype 1 IPD isolates | All ages | IPD | 34 | PCR | √ | |

| Staples et al., 2014 [37] | Australia | 2008 - 2012 | Serotype 1 IPD isolates | Unspecified | IPD | 253 | PCR | √ | |

| Zhou et al., 2017 [38] | China | 2006 - 2012 | Patients in a hospital in Shanghai, China | Children, < 10 years | IPD & NIPD | 15 | PCR | √ | |

| du Plessis et al., 2016 [39] | South Africa | 1989 - 2013 | IPD cases | All ages | IPD | 534 | Whole genome sequencing | √ | √ |

| Brueggemann et al., 2013 [40] | Kenya | 1994 - 2008 | Healthy persons and ill children | Children, > 5 | IPD & Carriage | 161 | PCR | √ | |

| Donkor et al., 2013 [41] | West Africa | 1996 - 2007 | Pneumococcal carriage and IPD isolates | Children, < 15 years | IPD & Carriage | 7 | PCR | √ | |

| Zemlicková et al, 2005 [42] | Multicenter | 1990 - 2002 | Children with IPD | Children, < 5 years | IPD | 26 | PCR | √ | |

| Muñoz-Almagro et al., 2011 [43] | Spain | 2009 | Patients with IPD | All ages | IPD | 137 | multiplex PCR | √ | |

| Cooke et al., 2010 [44] | United Kingdom | 1999 - 2007 | IPD cases | Unspecified | IPD | 225 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Clarke et al., 2006 [45] | United Kingdom | 2000 - 2004 | Children with IPD | Children, < 5 years | IPD | 7 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Muñoz-Almagro et al., 2008 [46] | Spain | 1997 - 2006 | Patients with IPD | All ages | IPD | 34 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Beall et al., 2006 [47] | United States | 1999 - 2002 | IPD cases | Unspecified | IPD | 63 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Antonio, Dada-Adegbola, et al., 2008 [48] | Gambia | 2000 - 2004 | Children investigated for possible IPD | Children, 2 - 29 months | IPD | 8 | Box PCR | √ | |

| Yaro et al., 2006 [49] | Burkina Faso | 2002 - 2005 | Persons with suspected acute bacterial meningitis | All ages, 2 - 29 years | IPD | 21 | PCR | √ | |

| Zahner et al., 2010 [50] | United States | 1994 - 2006 | IPD cases | Unspecified | IPD | 5 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Grau et al., 2012 [51] | Spain | 1996 - 2010 | Patients with IPD | Adults, 18 - 64 years | IPD | 76 | PCR | √ | |

| Kourna Hama et al., 2019 [52] | Niger | 2010 - 2016 | Children with suspected meningitis | Children, < 5 years | IPD | 10 | qPCR, Whole genome sequencing | √ | |

| Jefferies et al., 2010 [53] | United Kingdom | 2001 - 2006 | IPD cases | All ages | IPD | 261 | PCR | √ | |

| Porat et al., 2012 [54] | Israel | 1999 - 2008 | Cases of AOM & IPD | Children | IPD & NIPD | 92 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Foster et al., 2008 [55] | United Kingdom | 1996 - 2005 | IPD cases | All ages | IPD | 203 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Chaguza et al., 2017 [56] | Malawi | 2004 - 2010 | IPD cases | All ages | IPD | 113 | PCR, whole genome sequencing | √ | √ |

| Sanneh et al., 2019 [57] | Gambia | 2010 - 2016 | Suspected cases of meningitis | Children, < 5 years | IPD | 17 | qPCR, multiplex PCR, Whole genome sequencing | √ | |

| Tsolenyanu et al., 2019 [58] | Togo | 2010 - 2016 | Suspected cases of meningitis | Children, < 5 years | IPD | 7 | RT-PCR, whole genome sequencing | √ | |

| Sharew et al., 2024 [59] | Ethiopia | 2018 - 2019 | Patients with IPD and NIPD | All ages | IPD & NIPD | 1 | Whole genome sequencing | √ | √ |

| Serrano et al., 2005 [60] | Portugal | 1999 - 2002 | IPD cases | Children | IPD | 470 | Unspecified | √ | |

| Cornick et al., 2015 [61] | Multicenter | 2003 - 2008 | serotype 1 pneumococci recovered from hospital, surveillance and carriage studies | All ages | IPD, NIPD & Carriage | 448 | Whole genome sequencing | √ | √ |

| Database | Keywords | Filters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Document Type | Open access | ||

| PubMed | “Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 1” OR “serotype 1 streptococcus pneumoniae” OR “pneumococcal serotype 1” | English | - | Free full-text |

| Scopus | English | Article | All Open Access | |

| Web of Science | English | Article | Open Access | |

| ScienceDirect | English | Research article | Open Access & Open archives | |

| Google Scholar | English | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).