Introduction

Pathological impairment of myocardial activation and slowing myocardial conduction can lead to fatal ventricular tachyarrhythmias. The search for a novel signaling agent that targets specific ion channels related to electrical conduction presents an important research problem. Voltage-gated sodium channels play a significant role in the activation of ventricular myocardium. It is reported that G protein-coupled receptors can regulate the function of voltage-gated ion channels including sodium channel [Holz et al., 1986; Hille et al., 2014; Mattheisen et al., 2018].

In the in vivo experiments, melatonin has been shown earlier to enhance INa sodium current in the adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes, thereby enhancing activation and increasing conduction velocity [Durkina et al., 2022], which accounted for the reduction in the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias [Sedova et al., 2019, Tsvetkova et al., 2020, Durkina et al., 2023]. However, important question remains unsolved, namely whether melatonin acts on cardiomyocytes directly or its effect is mediated by systemic mechanisms. Melatonin activates G protein-coupled receptors (MT1 and/or MT2), which are present in the myocardium [Han et al., 2019]. It means that the direct effect of melatonin on cardiomyocytes is probable but has not been still confirmed. To address the question, we studied the influence of melatonin on sodium channels in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes.

Materials and Methods

General

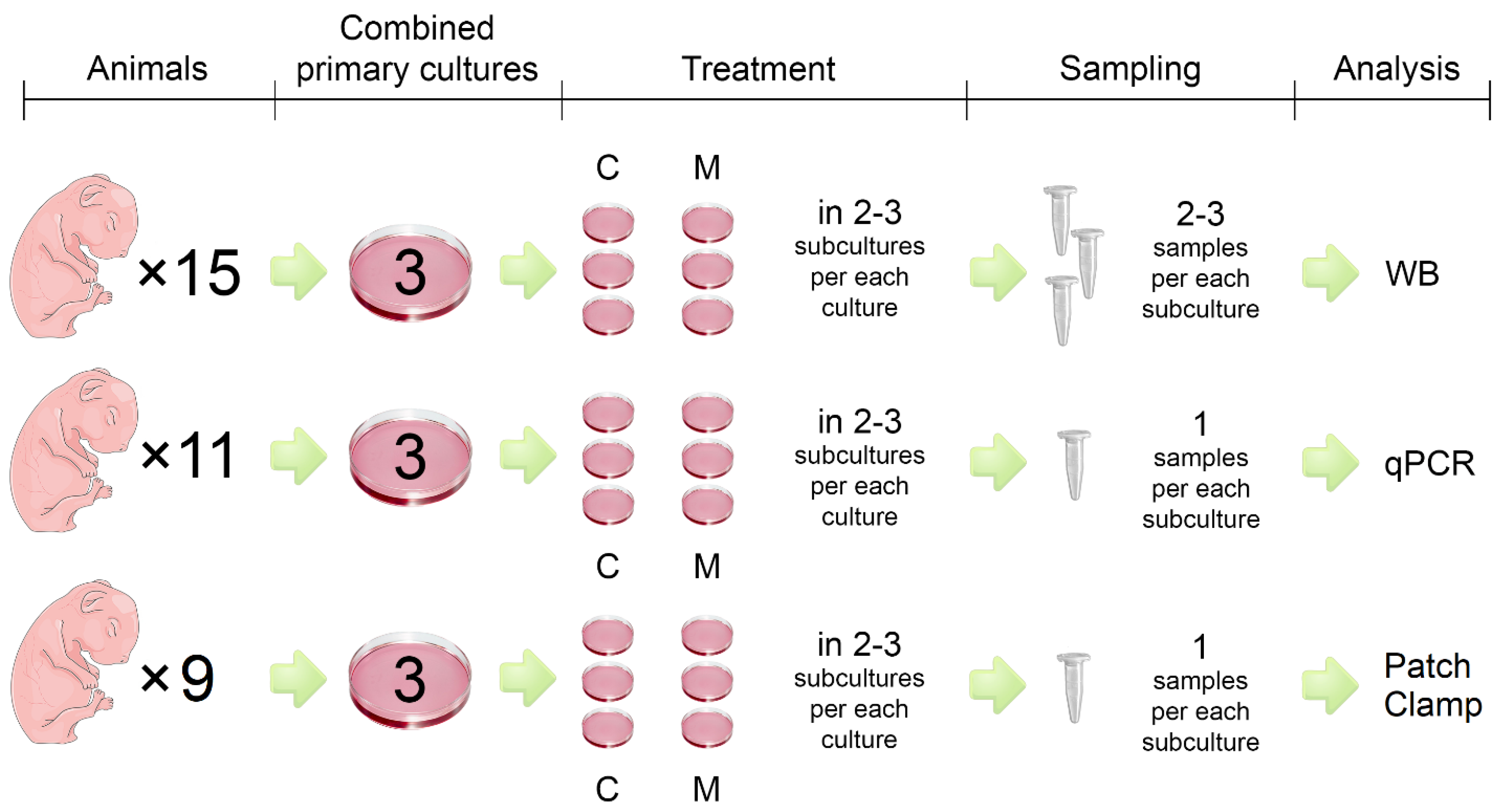

In the present study, the hearts of newborn Wistar rats (1-3 days old) were used to obtain a primary cell culture of cardiomyocytes (CMs). After 6-7 days of primary cells isolation cell, cultures were incubated with medium containing 100 µM melatonin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 24 hours. Then RNA and total protein were extracted from the cells for studies using the RT-PCR method and for the western blotting analysis. The INa sodium current of cultured CMs was recorded using a whole cell patch-clamp technique. The study design is presented in

Figure 1.

The study conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Eighth Edition published by the National Academies Press (United States), 2011, the guidelines from Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, and was approved by the ethical committee of the Institute of Physiology of the Komi Science Centre, Ural Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences (approval April 10, 2024).

Isolation and Cultures of Neonatal Ventricular Cell

The protocol for isolation and culturing of cardiomyocytes was developed on the basis of several previously published ones [Pereira et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2012; Li et al., 2020]. Newborn rats were quickly decapitated (4-15 puppies per isolation). The hearts were collected in sterile calcium-free Krebs-Ringer’s solution on ice containing (in mM): 45 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10 HEPES, 25 Glucose, 1 MgCl2, pH 7.4. All subsequent steps were performed under sterile conditions in a laminar-flow box. All solutions were prepared and sterilized by 0.2 µm filtration in advance. The hearts were transferred to a new tube with 200 µL of cold Krebs-Ringer’s solution, the atria and great vessels were carefully removed, and ventricles were homogenized using scissors. Then, 1 mL collagenase solution (Krebs-Ringer’s solution, 5 mg/mL collagenase Worthington, USA and 50 µM CaCl2) was added to the ventricular tissue, which was incubated for 9 min at 37°C, 5% CO2. The cell suspension was pipetted 30-40 times, and the supernatant was transferred to a new 2 mL tube. Cells were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes. The first supernatant fraction containing many fibroblasts and blood cells was discarded. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (low glucose) (Servicebio, China) supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone, USA), 10 µM sodium lactate (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Servicebio, China). The cell suspension was pre-plated on 6 -well plates for 1 hour at 37°C, 5% CO2 to remove fibroblasts. Then the cell suspension was collected into a common tube, centrifugated at 800 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was resuspended in fresh medium. The number of cells were determined, and 700K cells were plated per well of the plate for PCR and Western blotting analysis, while 200K cells were plated on coverslips for Patch-clamp recordings. After 24 hours, the media was changed to contain 3% FBS to remove dead cells; thereafter the medium was changed every 2 days. After 6-7 days of cultivation, the cells were ready for use.

PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using Aurum Total RNA lysis solution (Bio-Rad, USA) and diaGene RNA extraction kit (Dia-M, Russia), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity of extracted RNA was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. Quantification was performed using Qubit RNA BR Assay Kit and a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using a reverse transcription with the MMLV RT kit (Evrogene, Russia), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The RT-PCR reactions were carried out using qPCRmix-HS SYBR (Evrogen, Russia) on QuantStudio 5 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The following PCR cycling conditions were used: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, 57°C for 15 seconds, and 72°C 30 seconds. Each analysis was performed in triplicate technical replicates, and the mean relative expression values from these replicates were used for subsequent statistical analysis. Relative expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method [Livak et al., 2001] by normalizing to the geometric averaging of GAPDH gene and β-actin gene. Primers were designed using Primer-BLAST online tools. The sequences of the primers used for RT-PCR are as follows: Scn5a forward, 5′-TGTGTGCGTAACTTCACCGA-3′, reverse, 5′-ACATCCGTGGTGCCATTCTT-3′; Scn1b forward, 5′-GTCACGTCTACCGTCTCCTC-3′, reverse, 5′-GGCAGCAGCAATCTTCTTGT-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-ATGGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAA-3′, reverse, 5′-CGACATACTCAGCACCAGCAT-3′; β-actin forward, 5′-GCCTTCCTTCCTGGGTATGG-3′, reverse, 5′-ACGCAGCTCAGTAACAGTCC- 3′. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Evrogen (Russia). The specificity of the primers was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Western Blotting

The neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were washed with cold-ice PBS and lysed in 350 µL of RIPA buffer (Servicebio, China) and protease inhibitors cocktail (TransGen, China) to isolate total proteins. Lysate concentrations, purified by centrifugation, were measured using the Quick Start Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, USA) on a CLARIOstar Plus plate reader (BMG Labtech, USA). For each sample, 40 mg of protein was separated on 8% acrylamide gels (Smart-Lifesciences, China) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad, USA). Following blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBST solution (0.1% Tween-20, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris) for 1 hour, the membrane fragments were incubated at room temperature for 3 hours with primary antibodies Anti-NaV1.5 (Scn5a) Antibody (diluted 1:2000 in TBST with 3% BSA, #PA5-115620, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). After washing in TBST, the membranes were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with recombinant Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) HRP antibody (diluted 1:25000, #S0001, Affinity Biosciences, China). Subsequent to five washes in TBST, the Immun-Star Western C reagent and Chemidoc XRS imager (both from Bio-Rad, USA) were employed for blots visualization. Signal quantification from the recorded images was performed using the ImageLab software (Bio-Rad, USA). The Western blot analyses were conducted at the Centre of Collective Usage «Molecular biology» of the Institute of Biology of Komi SC UrB RAS.

Patch-Clamp Electrophysiological Recording

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of the sodium current (INa) were conducted using the Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instrument, USA) under controlled room temperature conditions (22–24°C). Coverslips with primary culture of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were placed into the bath chamber perfused with a Cs+-based low-Na+ extracellular solution containing (in mM): 80 NaCl, 10 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 20 TEA-Cl, 20 glucose, 1.2 KH2PO4, and 10 HEPES, with the pH 7.4 adjusted using NaOH at a temperature of 22°C. Patch pipettes with an average resistance of 1.6 ± 0.3 MΩ were pulled using a HEKA PIP 6 pipette puller (HEKA Electronics, USA) from borosilicate glass (Sutter Instruments, USA). These pipettes were filled with an intracellular solution containing (in mM): 10 NaCl, 130 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 4 Mg2ATP, and 10 HEPES, with pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. Prior to recording, pipette capacitance, cell capacitance, and series resistance were compensated to ensure accurate measurements. The INa current was recorded in the presence of 2 × 10–5 M nifedipine in the bath solution to inhibit ICaL. The INa current was obtained using a square-step protocol (-120 mV – +60 mV) from a holding potential of -120 mV with 10 mV steps applied every 2000 ms. The INa sodium current was recorded using software WinWCP 5.4.1 (Strathclyde Electrophysiology Software, UK), data processing was carried out using ClampFit 10.6 software (Molecular devices, USA). The steady-state voltage dependence of activation and inactivation for the voltage-gated sodium channels was determined by the Boltzmann equation, as described in [Karmažínová et al., 2010].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, USA) . To test normality of data distribution, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used. Differences between groups were evaluated using unpair Student t-test. All data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Expression of Scn5a mRNA and NaV1.5 Protein in Neonatal Rat Cardiomyocytes After Melatonin Treatment

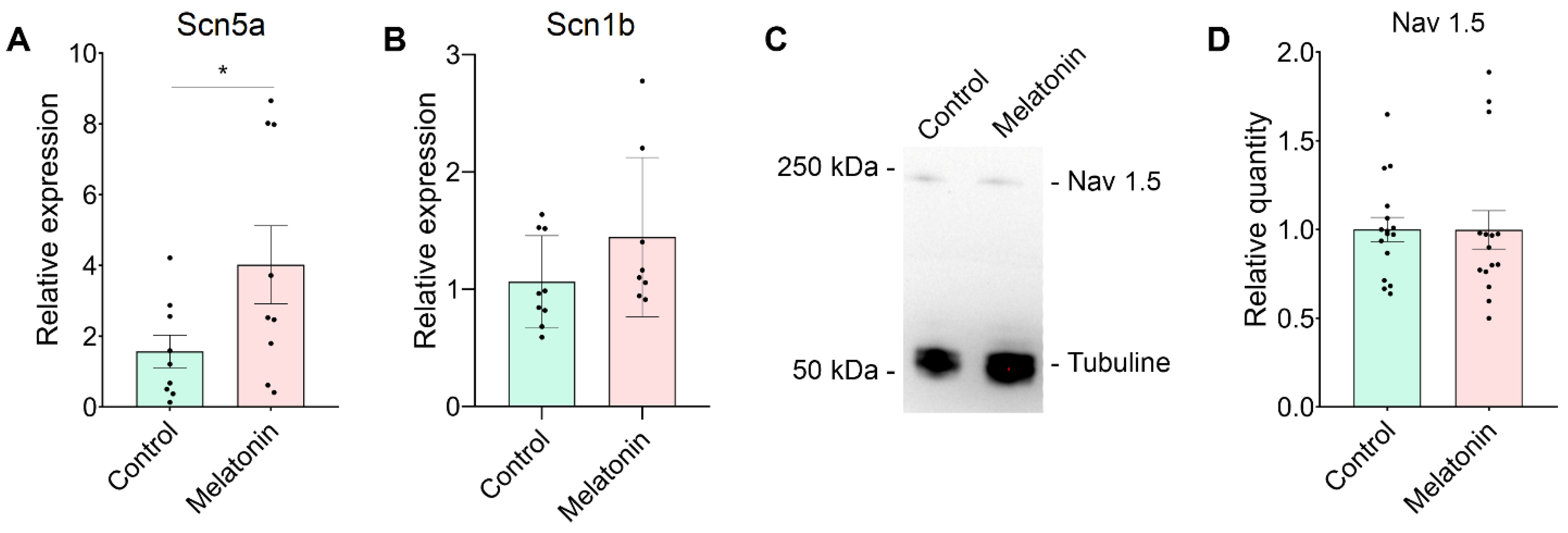

The relative mRNA expression of Scn5a gene transcript was significantly increased in cardiomyocytes after incubation with melatonin at a concentration of 100 µM (

Figure 2A) compared to the control group. The relative mRNA expression of Scn1b gene transcript did not differ between the groups.

Interestingly, western blotting provided contrasting results regarding the expression of NaV1.5 protein in neonatal cardiomyocytes at the same concentration of the melatonin when compared to the relative mRNA expression. Specifically, the level of NaV1.5 protein in cultured cells remained unchanged after 24-hour exposure to melatonin, similar to the control group (

Figure 2B).

Melatonin Increases the Amplitude of INa Current in Cultured Neonatal Rat Cardiomyocytes

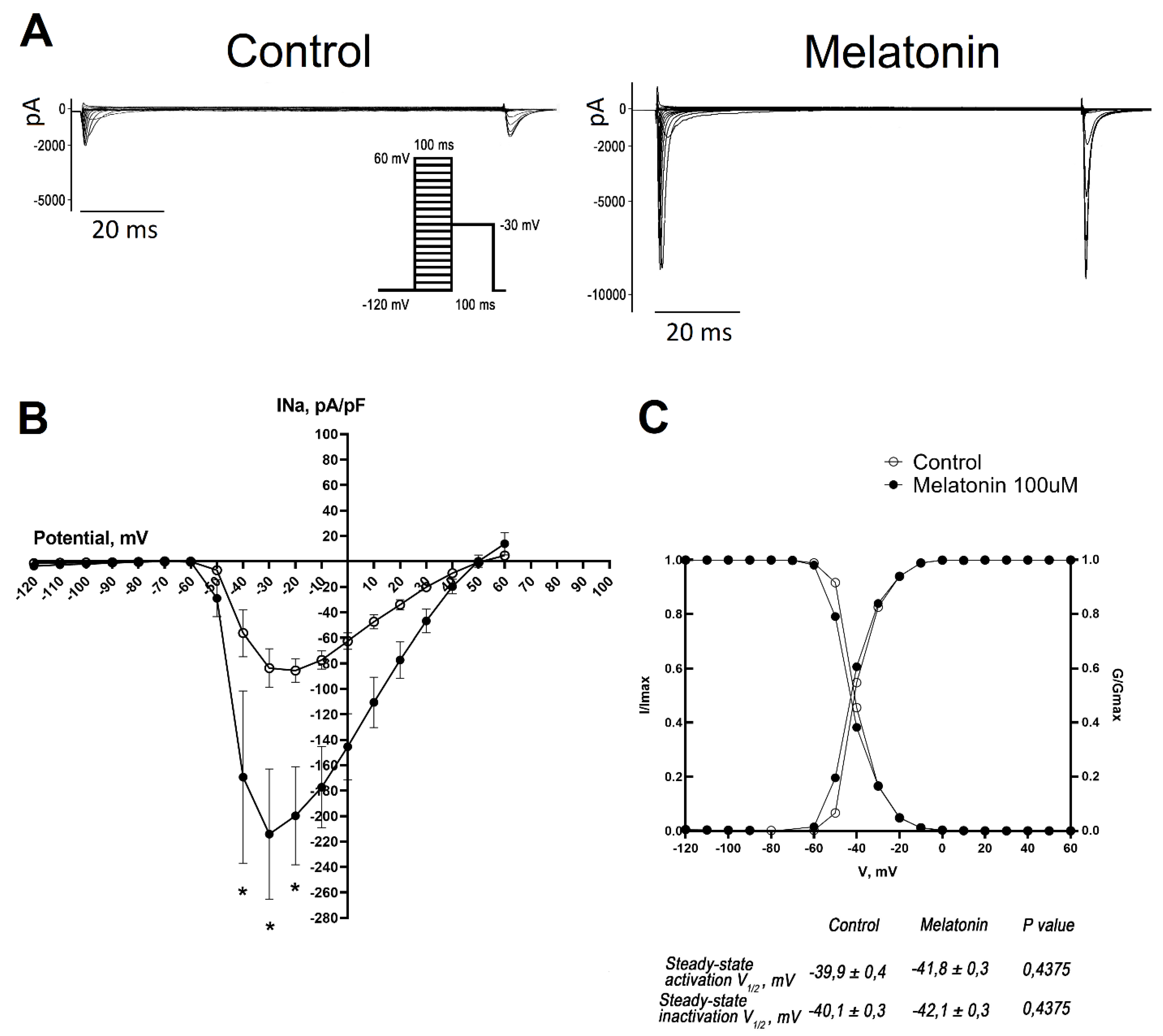

Representative whole-cell traces and I-V curves illustrated the increase in the amplitude of INa in neonatal cardiomyocytes incubated with melatonin (

Figure 3A, B). Interestingly, this increase in amplitude was not caused by changes in their gating properties since steady-state activation and inactivation curves did not differ in the treated and control cells (

Figure 3C).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that melatonin influences sodium channels in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes. Specifically, 24-hour melatonin incubation enhanced the expression of the Scn5a gene and significantly increased the INa sodium current in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes. However, this treatment did not affect the characteristics of steady-state activation and inactivation of the sodium channels and the overall level of Nav1.5 protein.

Previous research has demonstrated that melatonin treatment in vivo reduces the occurrence of life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias in vivo [Sedova et al., 2019; Tsvetkova et al., 2020; Durkina et al., 2023], shortens myocardial activation time, and enhances INa current as well as mRNA of Scn5a gene transcripts and Nav1.5 protein expression in the ventricles of adult rats [Durkina et al., 2022]. The results of the present study are consistent with the above-mentioned in vivo findings concerning the expression of Scn5a gene mRNA and INa current. However, we did not observe the changes in the relative protein levels of Nav1.5, which might be accounted for by a suggestion that in addition to the increase in Scn5a expression melatonin caused posttranslational effects on Nav1.5 that were not reflected in the changes in the protein level but were expressed functionally as the increase in INa current. It also cannot be excluded that the expected effect on the relative protein levels of Nav1.5 appeared to be not high enough to be detected by the used technique and/or setting. This explanation is supported by our previous observations [Durkina et al., 2022] of the increased Nav1.5 level after a longer (7 days) melatonin treatment in vivo. It is also noteworthy that in the present study melatonin did not affect the expression of the Scn1b gene encoding the β-subunit of the sodium channel responsible for the regulation of the kinetics and gating of the sodium channels [Brackenbury et al., 2011; Rook et al., 2012]. It accounts for the unchanged steady-state activation and inactivation characteristics of the sodium channel in our experiments.

The effects of melatonin on the sodium channels are expected to be mediated by complex melatonin signaling pathways. Since both MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors are predominantly coupled to Gαi/o subunits, they typically signal through inhibition of the cAMP/PKA pathway [Cecon et al., 2018] thereby suppressing transcription of genes controlled by the cAMP responsive element binding protein [Okamoto et al., 2024]. However, recent research revealed other possible signaling pathways for melatonin to influence the heart via MT1 and MT2 receptors. Using real-time intracellular cAMP determination, Tse et al. demonstrated that activation of melatonin receptors can either decrease or increase cAMP production depending on the relative abundance of Gs and Gi proteins, MT1 and MT2 receptors, and on the efficacy of the respective receptor/G proteins coupling [Tse et al., 2024]. Melatonin can directly and indirectly interact with calmodulin and affect calmodulin distribution in the cellular compartments [Turjanski et al., 2004; Estrada-Reyes et al., 2022; Benítez-King et al., 2024]. These complex interactions account for both inhibition (mostly short-term) and activation (mostly long-term) of the CaM-dependent pathways by melatonin. Also, melatonin has been shown to activate PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways via MT1 and/or MT2 receptors [Shu et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2017] and therefore positively regulate transcription of genes controlled by these pathways [Okamoto et al., 2024].

Many of the melatonin signaling pathways delineated above can be involved in the regulation of Nav1.5 channel expression and function. Sodium channels can be regulated by multiple kinases, in particular cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC), and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII), which phosphorylate and regulate the biosynthesis of Nav1.5 channels [Iqbal et al., 2019]. Enhancement of Scn5a expression can be also mediated by Akt/ERK1/2-FOXO1 signaling pathway [Ballou et al., 2015]. Direct modulation of Nav1.5 channels in rat cardiomyocytes via the stimulatory subunit of G-protein has also been reported, leading to the increase in sodium current [Palygin et al., 2008; Lowe et al., 2008].

The impact of PKA on INa current remains a subject of debate. For instance, it has been established that PKA modulation of the NaV1.5 channel via β-adrenergic receptors (β-AR) stimulation in neonatal rat myocytes decreases INa and induces a hyperpolarization shift in the steady-state inactivation curve due to elevated cAMP level [Ono et al., 1993; Schubert et al., 1999]. Conversely, studies in guinea pig cardiomyocytes reveal that β-AR stimulation can lead to PKA-independent increases in INa current by augmenting the number of functional sodium channels without altering their kinetic properties [Wang et al., 2008]. Similarly, research in rabbit cardiomyocytes has shown an increase in INa current density, attributed to phosphorylation of NaV1.5 either via PKA or G-protein (Gsα) activation, with no observed changes in sodium channel gating [Matsuda et al., 1992]. More recently, Bernas et al. have demonstrated that persistent PKA activation increases the amplitude of INa current without affecting the overall protein of NaV1.5 channel [Bernas et al., 2024]. Taken together, the data imply that melatonin could affect sodium channels on both expression and posttranslational levels via the PKA-dependent pathways and these influences can provide plausible explanations for our findings.

The activation of PKC via MT1 and MT2 is hypothesized to lead to a reduction in sodium current. Specifically, experimental evidence suggests that PKC stimulation reduces the amplitude of the sodium current and shifts the activation curve towards more positive potentials and trafficked sodium channels away from plasma membrane [Hallaq et al., 2012]. Activation of CaMKII has been shown to alter the steady-state properties of sodium channels and enhance the late sodium current, which is associated with an increased risk of arrhythmias [Wagner et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2023]. These findings contrast with the observations from the present study, and therefore the potential PKC and CaMKII activation by melatonin as an explanation for INa-enhancing mechanism can be discarded. On the other hand, since Scn5a expression can be enhanced by the activation of Akt/ERK1/2-FOXO1 signaling pathway [Ballou et al., 2015] and melatonin activates it [Okamoto et al., 2024], the observed here increase in Scn5a expression and INa current might be due to the Akt/ERK1/2 involvement in melatonin signaling.

Study limitations. Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes serve as a good experimental model. However, despite multiple advantages, there are several disadvantages of this model. For instance, neonatal cardiomyocytes have an immature cellular phenotype, which can manifest in strong variability of electrophysiological parameters and data scatter (that we observed in the present study from culture to culture, consisting of cells from several hearts). Nevertheless, all primary cultures in our study were obtained according to a uniform well-established protocol and were cultivated under identical controlled conditions and we were able to demonstrate consistent melatonin effects at least concerning Scn5a expression and characteristics of INa current.

Conclusion

In this study for the first time, we demonstrated the ability of melatonin to augment sodium current in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes due to its direct action on cells independently of its possible systemic effects in the organism. Notably, melatonin did so without altering the sodium channel gating, which is important because alterations in steady-state activation and inactivation can lead to an increase in an arrhythmogenic late sodium current. Our data suggest that melatonin impact on cardiac electrophysiology is multifaceted, with direct effects on sodium currents that could have implications for cardiac impulse conduction.

Authors’ Contribution

A. Durkina, J. Azarov – concept and design; A. Durkina, M. Gonotkov, A. Furman, I. Velegzhaninov – experiments and data processing, O. Bernikova – primers design, A. Durkina, M. Gonotkov, K. Sedova, V. Mikhailova, I. Velegzhaninov, J. Azarov - analysis, A. Durkina, J. Azarov – drafting the manuscript. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation RSF 23-25-00504.

References

- Holz GG 4th, Rane SG, Dunlap K. GTP-binding proteins mediate transmitter inhibition of voltage-dependent calcium channels. Nature 1986, 319, 670–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hille B, Dickson E, Kruse M, Falkenburger B. Dynamic metabolic control of an ion channel. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2014, 123, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattheisen GB, Tsintsadze T, Smith SM. Strong G-Protein-Mediated Inhibition of Sodium Channels. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 2770–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Durkina AV, Bernikova OG, Gonotkov MA, Mikhaleva NJ, Sedova KA, Malykhina IA, Kuzmin VS, Velegzhaninov IO, Azarov JE. Melatonin treatment improves ventricular conduction via upregulation of Nav1.5 channel proteins and sodium current in the normal rat heart. J Pineal Res. 2022, 73, e12798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedova KA, Bernikova OG, Cuprova JI, Ivanova AD, Kutaeva GA, Pliss MG, Lopatina EV, Vaykshnorayte MA, Diez ER, Azarov JE. Association Between Antiarrhythmic, Electrophysiological, and Antioxidative Effects of Melatonin in Ischemia/Reperfusion. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsvetkova AS, Bernikova OG, Mikhaleva NJ, Khramova DS, Ovechkin AO, Demidova MM, Platonov PG, Azarov JE. Melatonin Prevents Early but Not Delayed Ventricular Fibrillation in the Experimental Porcine Model of Acute Ischemia. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 22, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Durkina AV, Szeiffova Bacova B, Bernikova OG, Gonotkov MA, Sedova KA, Cuprova J, Vaykshnorayte MA, Diez ER, Prado NJ, Azarov JE. Blockade of Melatonin Receptors Abolishes Its Antiarrhythmic Effect and Slows Ventricular Conduction in Rat Hearts. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 11931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Han D, Wang Y, Chen J, Zhang J, Yu P, Zhang R, Li S, Tao B, Wang Y, Qiu Y, Xu M, Gao E, Cao F. Activation of melatonin receptor 2 but not melatonin receptor 1 mediates melatonin-conferred cardioprotection against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Pineal Res. 2019, 67, e12571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira AHM, Cardoso AC, Franchini KG. Isolation, culture, and immunostaining of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. STAR Protoc. 2021, 2, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nguyen PD, Hsiao ST, Sivakumaran P, Lim SY, Dilley RJ. Enrichment of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes in primary culture facilitates long-term maintenance of contractility in vitro. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012, 303, C1220–C1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li C, Rong X, Qin J, Wang S. An improved two-step method for extraction and purification of primary cardiomyocytes from neonatal mice. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2020, 104, 106887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmažínová M, Lacinová L. Measurement of cellular excitability by whole cell patch clamp technique. Measurement of cellular excitability by whole cell patch clamp technique. Physiol Res. 2010, 59 (Suppl. S1), S1–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brackenbury WJ, Isom LL. Na channel beta subunits: overachievers of the ion channel family. Front Pharmacol. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Rook MB, Evers MM, Vos MA, Bierhuizen MF. Biology of cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 expression. Cardiovasc Res. 2012, 93, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecon E, Oishi A, Jockers R. Melatonin receptors: molecular pharmacology and signalling in the context of system bias. Br J Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 3263–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tse LH, Cheung ST, Lee S, Wong YH. Real-Time Determination of Intracellular cAMP Reveals Functional Coupling of Gs Protein to the Melatonin MT1 Receptor. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iqbal SM, Lemmens-Gruber R. Phosphorylation of cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel: Potential players with multiple dimensions. Acta Physiol 2019, 225, e13210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Palygin OA, Pettus JM, Shibata EF. Regulation of caveolar cardiac sodium current by a single Gsalpha histidine residue. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008, 294, H1693–H1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe JS, Palygin O, Bhasin N, Hund TJ, Boyden PA, Shibata E, Anderson ME, Mohler PJ. Voltage-gated Nav channel targeting in the heart requires an ankyrin-G dependent cellular pathway. J Cell Biol. 2008, 180, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ono K, Fozzard HA, Hanck DA. Mechanism of cAMP-dependent modulation of cardiac sodium channel current kinetics. Circ Res. 1993, 72, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert B, Vandongen AM, Kirsch GE, Brown AM. Inhibition of cardiac Na+ currents by isoproterenol. Am J Physiol. 1990, 258, H977–H982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang HW, Yang ZF, Zhang Y, Yang JM, Liu YM, Li CZ. Beta-receptor activation increases sodium current in guinea pig heart. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009, 30, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matsuda JJ, Lee H, Shibata EF. Enhancement of rabbit cardiac sodium channels by beta-adrenergic stimulation. Circ Res. 1992, 70, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernas, T. , Seo, J., Wilson, Z. T., Tan, B. H., Deschenes, I., Carter, C., Liu, J., & Tseng, G. N. Persistent PKA activation redistributes NaV1.5 to the cell surface of adult rat ventricular myocytes. J. Gen. Physiol. 2024, 156, e202313436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallaq H, Wang DW, Kunic JD, George AL Jr, Wells KS, Murray KT. Activation of protein kinase C alters the intracellular distribution and mobility of cardiac Na+ channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012, 302, H782–H789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wagner S, Dybkova N, Rasenack EC, Jacobshagen C, Fabritz L, Kirchhof P, Maier SK, Zhang T, Hasenfuss G, Brown JH, Bers DM, Maier LS. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates cardiac Na+ channels. J Clin Invest. 2006, 116, 3127–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu X, Ren L, Yu S, Li G, He P, Yang Q, Wei X, Thai PN, Wu L, Huo Y. Late sodium current in synergism with Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II contributes to β-adrenergic activation-induced atrial fibrillation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2023, 378, 20220163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ballou, L.M.; Lin, R.Z.; Cohen, I.S. Control of Cardiac Repolarization by Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Signaling to Ion Channels. Circ Res 2015, 116, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, T.; Wu, T.; Pang, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Rong, L. Effects and mechanisms of melatonin on neural differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016, 474, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Song, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.; Fu, B.; Mao, T.; Zhang, Y. Melatonin-mediated upregulation of GLUT1 blocks exit from pluripotency by increasing the uptake of oxidized vitamin C in mouse embryonic stem cells. Faseb j 2017, 31, 1731–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, H.H.; Cecon, E.; Nureki, O.; Rivara, S.; Jockers, R. Melatonin receptor structure and signaling. J Pineal Res 2024, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turjanski, A.G.; Estrin, D.A.; Rosenstein, R.E.; McCormick, J.E.; Martin, S.R.; Pastore, A.; Biekofsky, R.R.; Martorana, V. NMR and molecular dynamics studies of the interaction of melatonin with calmodulin. Protein Sci 2004, 13, 2925–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Reyes, R.; Quero-Chávez, D.B.; Alarcón-Elizalde, S.; Cercós, M.G.; Trueta, C.; Constantino-Jonapa, L.A.; Oikawa-Sala, J.; Argueta, J.; Cruz-Garduño, R.; Dubocovich, M.L.; et al. Antidepressant Low Doses of Ketamine and Melatonin in Combination Produce Additive Neurogenesis in Human Olfactory Neuronal Precursors. Molecules 2022, 27, 5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-King, G.; Argueta, J.; Miranda-Riestra, A.; Muñoz-Delgado, J.; Estrada-Reyes, R. Interaction of the Melatonin/Ca<sup>2+</sup>-CaM Complex with Calmodulin Kinase II: Physiological Importance. Mol Pharmacol 2024, 106, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).