1. Introduction

Great risk of drowning in Breath-hold divers (BHD) occurs immediately after dive on surface [

1]. At this moment, with very low oxygen saturation (SpO2), the sympathetic nervous system is reactivated, which causes the metabolism to accelerate recovery from the effort produced by previous apnea [

2]. This requires performing efficient breathing to avoid that the little oxygen left is consumed by this increased metabolism. In sports events, the safety divers are present; however, it rarely occurs in amateur freediving practices. According to the World Health Organization, drowning is the third leading cause of unintentional injury death worldwide. There are an estimated 236 000 annual drowning deaths worldwide. There is a wide range of uncertainty around the estimate of global drowning deaths; however, despite the difficulty of collecting data, making drowning a major public health problem worldwide [

3].

Most drowning events in amateurs are caused by apnea-related hypoxemia. Such hypoxemia could trigger the lost motor control or syncope [

4]; besides, in trained BHD lung edema occurrence could more quickly trigger severe hypoxemia. In trained BHD, who descend beyond their residual volume (25-40 m), the lung volume can no longer contract due to stiffness of the thorax. In parallel, there is a redistribution of blood flow from the periphery to the central regions, commonly referred to as blood shift. This causes a lower pressure in the lungs than in the surrounding capillaries. When such capillaries reach a certain degree of pressure, it extravasate blood into the lungs [

5]. Even mild edema can contribute to the risk of syncope by compromising gas exchange [

6].

Pulse oximetry has been used as a simple and effective method to detect possible edema after dive [

6], [

7]. In recent years, the use of lung ultrasound has been implemented as a more reliable method to detect post-dive pulmonary edema. With lung ultrasound, B-lines can be counted on images of different lung sections to quantify the presence of lung edema [

8].

To prevent syncope induced by hypoxemia, trained BHD use a breathing technique after surfacing called “hook breathing” (HB) (9). It consists of a full inspiration interrupted at the beginning of exhalation with a Valsalva-like maneuver and with subsequent exhalation performed against resistance to generate continuous positive airway pressure during exhalation (6). This breathing maneuver is observed in Air Force pilots to prevent loss of consciousness at high G-forces due to the drop in blood pressure during acceleration [

10]. In BHD, continuous positive airway pressure during expiration could open the atelectasis zones of the lung and force out edema-associated fluid [

11]; also, the increase in partial pressure of O2 achieved in the alveoli with HB would probably increase gas exchange [

12]. A previous study showed how HB was effective in SpO2 recovery, after -30m apnea, in BHD with a possible (estimated by pulse oximetry) mild pulmonary edema, while in asymptomatic BHD, the effect was insignificant [

6].

This study aimed to analyze the influence of HB on SpO2 recovery after ‒40 m deep dive compared to usual breathing (UB). We hypothesize a faster SpO2 recovery associated with HB.

2. Materials and Methods

A randomized crossover trial was conducted with a 1:1 allocation ratio assigning subjects to either perform: (1) HB followed by UB, or (2) UB followed by HB. Randomization was conducted prior to the assessment and initiation of the intervention using GraphPad software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The assessor was blinded as he did not know which participants were assigned. The washout period was 72 hours. The trial was approved by the local Ethics Committee for Human Research (CSEULS-PI-215/2018) and was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration. Protocol registration was performed in Clinical Trials Gov (NCT04366414).

2.1. Participants

A convenience non-probabilistic sampling method was employed, and the following inclusion criteria were imposed: (1) age between 18 and 65 years; and (2) baseline ≥ 95 %SpO2. The following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) cardiovascular diseases; (2) respiratory diseases; (3) lung squeeze event in the week prior to measurement; (4) current pharmacological treatment; (5) recreational drug use; (6) self-harming behaviors; (7) pregnancy or possibility of being pregnant; (8) splenectomy; (9) vigorous physical activity within 24 hours before the study.

The participants attended the intervention site (Apnea Canarias Center, Tenerife, Spain) during two separate days. Once there, the intervention protocol was explained. Subsequently, time was given for the reading and signing of informed consent, followed by the assessment.

2.2. Intervention

Each BHD performed 2 free immersion (FIM) dives to ‒40 m depth separated 72 hours, one followed by recovery breathing using HB and the other using UB. The starting order of the breathing maneuvers (HB or UB) was determined by randomization. All BHDs used their usual breathing preparation at the surface before dives. The diver was asked to start the dive when feeling ready. BHDs then used the arms to pull themselves down along a vertical line and up again followed by recovery breathing using either HB or UB.

All BHDs, already familiar with the HB protocol, received the following information: “take deep inhale, hold your breath and start to exhale with your glottis closed; then, open it, and continue to exhale with mouth resistance. When you finish, inhale and repeat protocol for one minute.”

2.3. Outcome Measures

Participants were described through sociodemographic and other characterization variables such as: (1) age; (2) sex; (3) body mass index (BMI); (4) resting heart rate (HR); (5)resting SpO2; (6) years of apnoea experience (in years, number of competitions and personal best in FIM); (7) history of apnoea-dive competitions (number); (8) personal best in FIM; and (9) percentage of the depth reached (40m) related to the personal best in FIM.

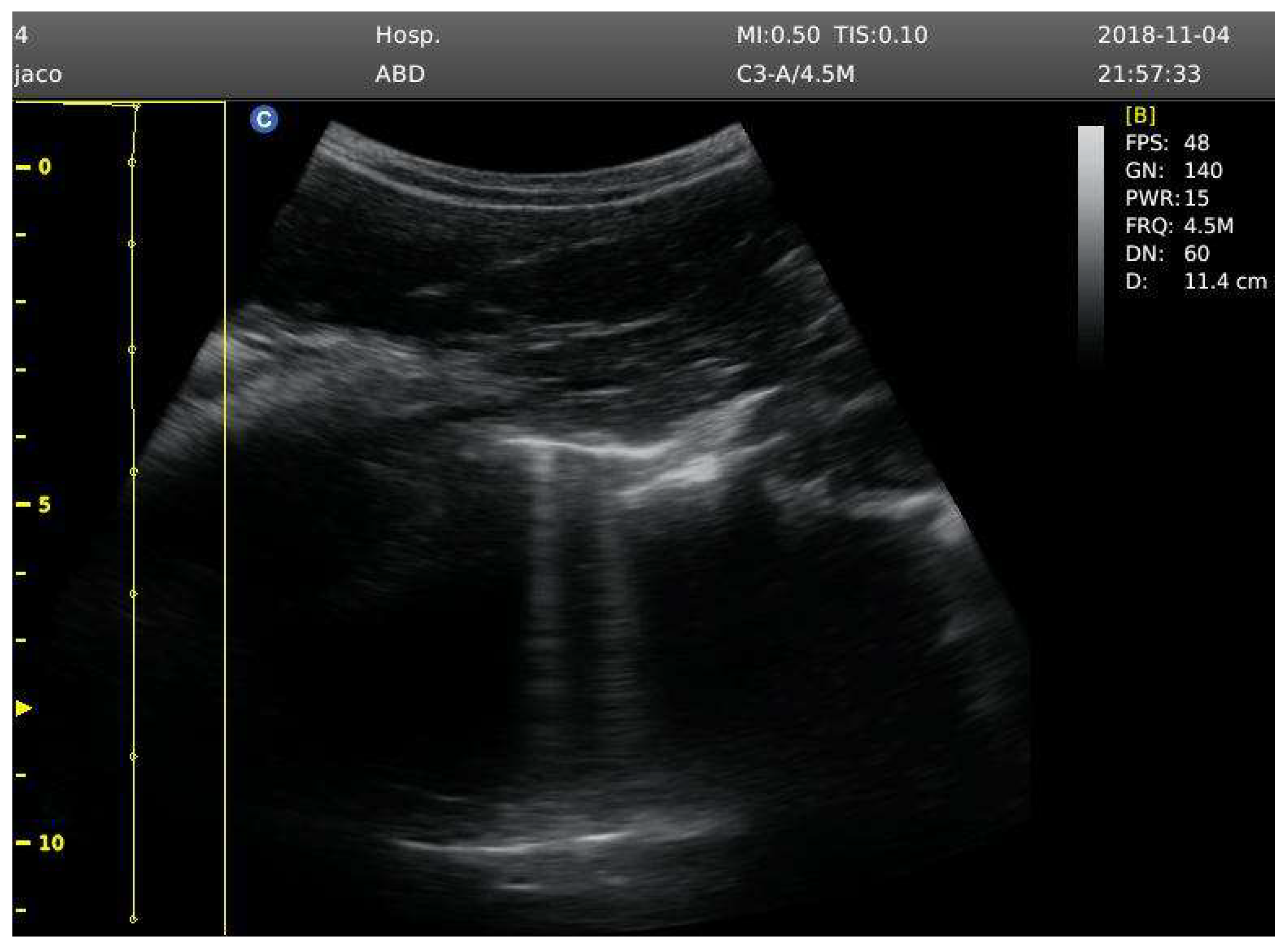

Baseline ultrasound B-lines were recorded before the competition, with participants not having conducted diving activity 24 hours before the assessment. Lung ultrasound was collected in the sitted position by displaying mode B, using 2D ultrasonic imaging, with a convex transducer 3.5 MHz (Chison ECO 5 Portable Ultrasound Scanner). Bilateral imaging of the hemithorax from the second to fourth intercostal spaces was performed, culminating in 6 assessment zones.

A B-line was detected as an echogenic comet-shaped signal spreading from the pleural line to the further border of the screen. The same medical researcher (E-P) performed all ultrasound measurements; then, B-lines were analysed by another medical researcher specialist on pulmary ultrasound (J-L) to provide a total B-line score [

13].Ultrasound B-lines are an index of extravascular lung fluid, and the sensitivity a reliability of this method has been contrasted in different studies compared with radiographic imaging [

14], [

15]. After analysis, the total number of B-lines was recorded to detect possible signs of pulmonary edema.

After surfacing, SpO2 and HR recordings started as soon as possible. Pulse oxymetry (NoninPalmSAT® 2500 series, Nonin Medical Inc.) were recorded every 5 seconds during 1 minute, while BHDs performed either the HB or UB protocol. During the measurement, a signal on the pulse oximeter indicated with green light (good perfusion) or red light (bad perfusion) if readings were reliable. Only data with good finger perfusion indicated were included. In further analysis, were counted the seconds when participant to reach normoxia (95% SpO2; [

16]). If the diver did not reach this value during recovery, 60 seconds were counted.

At the end of pulse oximetry recording, participants went by boat (within 10 minutes post-dive) to Radazul Port in Tenerife, where a new lung ultrasound (same protocol to baseline) was performed to detect possible signs of pulmonary edema. The data were stored and sent to the medical assessor, who was blinded to the interventions; however, if the participant showed obvious signs of edema (hemoptysis, chest tightness, dyspnea, hypoxemia), they would be immediately excluded from the study and transferred to a medical center for further examination. One hour after the end of the dive, the participants were called back to evaluate, again, their condition by pulse oximetry and lung ultrasound. This procedure was conducted in accordance and approved by the ethics committee.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R (version [4.4.1]) within the RStudio environment (RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, USA) version 2023.06.0+421. A range of R packages was utilized to ensure robust data manipulation, visualization, and statistical analysis, including tidyverse for data processing, rstatix for repeated-measures ANOVA and post-hoc tests, and ggplot2 for visualization.

Descriptive statistics summarized the sociodemographic, characterization, and outcome variables presenting mean ± SD, median, quartiles, minimum and maximum values, and absolute frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Data visualizations, such as boxplots, illustrated the distributions of SpO₂ values for each group over time.

A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of Group (Breathing technique: HB vs. UB) and Time (11 post-apnea intervals) on SpO₂. These variables were included as two within-subject factors. The model accounted for within-subject variability using participant ID as the repeated factor. Assumption of normality was assessed with Q-Q plots for each Group × Time combination, and Mauchly’s test assessed the assumption of sphericity. Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied where sphericity was violated to adjust degrees of freedom. One participant was eliminated from the analysis due to deviation from normality. After examining this subject, he was significantly older than the rest of the participants and he had developed severe pulmonary edema in both conditions, which may have produced a delayed SpO2 recovery across time.

Differences in SpO2 between HB and UB conditions accounted for the main effect of Group. Time-dependent changes in SpO2 irrespective of breathing technique accounted for the main effect of Time. Finally, differences in SpO2 between breathing techniques across time points accounted for interaction effect between Group and Time. Significant effects, which were set at p<0.05, were followed up with post-hoc analyses to explore specific differences.

Post-hoc comparisons were performed with Bonferroni corrections for between groups at each time point and within groups across time points. Pairwise comparisons tested SpO₂ differences using paired t-tests. Significant differences were reported with mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The sample consisted of 13 professional breath-hold divers with a mean age of 42 ± 9 years and a mean BMI of 24 ± 1.4 kg/m². All participants were male with an average apnea experience of 7.2 ± 2.9 years and had attended 11 ± 14 competitions. Baseline SpO₂ (%) was 97 ± 0.69 for the UB and 97± 0.69 for the HB, and baseline HR was 69 ± 16 bpm for the UB, and 70 ± 15 bpm for the HB group. All descriptive information is presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Four participants showed signs of mild pulmonary edema, after diving, coinciding in both protocols (Supp material 1). Ultrasound B-lines count was recorded at baseline, 10 minutes post-immersion and at 1 hour post-immersion (

Figure 1).

3.2. Oxygen Saturation Recovery

The repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant main effects for Group [F(1, 11) = 5.254; p = 0.043, ηg2 = 0.014], and Time [F(2.08, 22.87) = 32.171, p < 0.001, ηg2 = 0.649], as well as a significant Group × Time interaction [F(3.30, 36.26) = 3.497, p = 0.022, ηg2 = 0.054].

3.3. Oxygen Saturation Recovery - Post-Hoc Analysis

3.3.1. Within-Group Time Comparisons

Both groups exhibited significant increases in SpO₂ over time [UB: F(2.25, 24.7) = 22.1, p < 0.001, ηg2 = 0.612; HB: F(2.11, 23.2) = 29.0, p < 0.001, ηg2 = 0.688]. Pairwise comparisons revealed significant SpO₂ recovery from 10 seconds to 35 seconds, with the HB group recovering more rapidly to near-baseline levels.

3.3.2. Between-Group Comparisons

Significant differences in SpO₂ were observed between HB and UB at 30–45 seconds post-apnea, with higher SpO₂ values in the HB. Significant differences between groups included mean difference values ranging between 1.64 and 5.08% of SpO₂ in favor of HB intervention. No significant differences were found at earlier (10–25 seconds) or later time points (50–60 seconds). Differences between groups are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Percentage of oxygen saturation for both groups per each time, showing groups' distributions (a) and means (b).

Differences are shown in mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).t

-- Figure 2 about here –

4. Discussion

This study aimed to analyze the influence of HB on the recovery of oxygen saturation after a 40 m deep dive. To check the oxygen saturation recovery, each participant was monitored by pulse oximetry during the first minute after apnoea. Results showed an improved oxygen recovery in both groups; however, between 30-45 seconds HB reached a faster oxygen recovery. No significant differences were found at earlier or later time points. One explanation might be reflected in table 2, where it observed that in the HB protocol, participants surfaced with significantly lower saturations (5% lower on average) than in the UB protocol. This could explain why there are no differences at the beginning of the recovery, as the hemoglobin dissociation curve does not have a linear but an exponential behavior [

17]. During the later time points, after 50 s, there is a clearer hypothesis, which is that when normoxia is reached in both groups, a physiological ceiling effect is produced.

Participants performed a deep dive to 40m. At this depth the residual volume is normally reached [

18]. In this condition, because of the blood shift, small extravasations of liquid from the surrounding blood vessels into the alveolus might occur, resulting in a predictably mild pulmonary edema [

19]. The initial hypothesis suggested a faster oxygen saturation recovery associated with HB, pronounced in divers suffering mild lung edema. The proposed mechanism is that the increased pulmonary pressure with HB will counteract the pulmonary edema developed and facilitate oxygen uptake in divers prone to squeeze. It was supported by a previous study, where results suggest that HB is efficient for increasing oxygen saturation recovery rate in individuals prone to squeeze; however, signs of edema was estimated by pulse oximetry [

6]. In the present study, after pulmonary ultrasound test, the same four participants (30% of total) showed ultrasound B-lines within ten minutes post-dive. These signs of mild pulmonary edema were observed in both protocols (HB and UB; see supplementary material 2). As the sample was so small, it was not feasible to establish a subgroup analysis of those participants with signs of mild edema, and the descriptive data is merely reflected in the results.

Ultrasound B-lines were performed again one hour after to detect possible areas of atelectasis caused by pulmonary edema. This is important, since one of the effects to be studied was the effect of HB on the recovery of fluid accumulated during extravasation [

8]. In addition to lung ultrasound, oxygen saturation recovery was observed by pulse oximetry after one hour to see if the release of atelectasis zones produced improvements in alveolar diffusion and therefore in oxygen saturation. Results revealed that normoxia was reached after one hour in both groups (1% SpO2 higher in HB). Regarding ultrasound B-lines, also showed a significant reduction in both groups, but only asymptomatic B-Lines were reached by HB after one hour in BHDs with mild lung edema. Possible effects of HB, in addition to opening up atelectatic areas of the lung and forcing out any fluid could possibly be due to the slightly increased partial pressure of O2 achieved with HB [

10]. Other possibly contributing effects of HB could be related to changes in pulmonary ventilation/perfusion, venous return and blood pressure, which could be further studied in the laboratory [

20].

The study has certain limitations that are important to highlight. Firstly, the experimental diving depths were submaximal for the most of studied divers and may not have been straining for the pulmonary system, but it is likely that a greater portion of the divers would respond with a mild lung edema in maximal competition dives well beyond their individual residual volume. Also, the heterogeneity of the stimulus at 40 m deep (with difference between 32 % to 100% from their personal best in FIM) might produce responses heterogeneous.

Although ultrasound was performed as soon as possible without compromising the dive safety protocol, ten minutes passed from the dive to the pulmonary ultrasound test. It might reduce ultrasound B-lines due to the time recovery. As indirect measurement pulse oximetry was performed immediately after surfacing to detect signs of hypoxemia which could indicate mild pulmonary edema if normoxia was not restored within the first minute after dive.

While this sample size can provide valuable information, it is important to consider that larger sample sizes are often recommended for variables to have a distribution closer to normality and to allow for better generalization of the results. In future studies, it is suggested to consider a greater sample size to increase the robustness of statistical analyses and strengthen the external validity of the findings [

21].

Results suggest that HB might be efficient in speeding up recovery in individuals with and without mild lung edema, but a larger sample size is suggested to detect a reliable effect size of such an intervention. With a large heterogeneity of post-dive breathing protocols, HB is probably the recovery protocol that has shown the greatest size effect based on plausible scientific hypotheses.

5. Conclusions

After 40 m apnea dive, the results revealed significant SpO₂ recovery from 30 seconds to 45 seconds, in individuals with and without mild lung edema, with the HB recovering more rapidly to close-baseline levels. No differences were found at earlier (10-25 seconds) or later time points (50-60 seconds).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Q-Q plot ANOVA; Table S1: Count of ultrasound B-lines.

Author Contributions

According to the CRediT taxonomy, project administration, resource management, writing (original draft) and supervision, was carried out by FD-F; conceptualization, methodology and formal analysis were carried out by A-RV, JF-M and FD-F; finally, data collection and writing (reviewing and editing) were carried out by A-RV, JF-M, EP, JL and FD-F.

Funding

The APC was funded by Rey Juan Carlos University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of CSEU La Salle CSEULS-PI-215/2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants and Apnea Canarias for the use of its facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lindholm, P. The Physiology and Pathophysiology of Human Breath-Hold Diving. J Appl Physiol 2009, 106, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, F.; Gonzalez-Rave, J.; Gonzalez-Mohino, F. Assessment of Sensory Sensitivity through Critical Flicker Fusion Frequency Thresholds after a Maximum Voluntary Apnoea. Dyving and Hiperbaric Medicine 2019, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drowning. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drowning (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Lindholm, P. Loss of Motor Control and/or Loss of Consciousness during Breath-Hold Competitions. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2007, 28, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barković, I.; Maričić, V.; Reinić, B.; Marinelli, F.; Wensveen, T.T. Haemoptysis in Breath-Hold Divers; Where Does It Come From? Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine Journal 2021, 51, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, F. de A.; Rodríguez-Zamora, L.; Schagatay, E. Hook Breathing Facilitates SaO2 Recovery After Deep Dives in Freedivers With Slow Recovery; 2019; Vol. 10; ISBN 1664-042X.

- Schagatay, E.; Lodin-Sundström, A.; Schagatay, F.; Engan, H. Can SaO2 Measurements during Recovery Be Used to Detect Lung Barotrauma in Freedivers? In Proceedings of the 41st Congress of the European Underwater & Baromedical Society (EUBS); Amsterdam, 2015.

- Picano, E.; Frassi, F.; Agricola, E.; Gligorova, S.; Gargani, L.; Mottola, G. Ultrasound Lung Comets: A Clinically Useful Sign of Extravascular Lung Water. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2006, 19, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G. The Effect of Valsalva Manouvre on the Systemic and Pulmonary Arterial Pressure in Man. British Heart Journal 1954, 16, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naval Air Development Center, PA. Air Vehicle and Crew Systems Technology Dept., W. Enhancing Tolerance to Acceleration (+Gz) Stress: The “Hook” Maneuver Final Rept. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Grasso, S.; Fanelli, V.; Cafarelli, A.; Anaclerio, R.; Amabile, M.; Ancona, G.; Fiore, T. Effects of High versus Low Positive End-Expiratory Pressures in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005, 171, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helbert, C.; Paskanik, A.; Bredenberg, C.E. Effect of Positive End-Expiratory Pressure on Lung Water in Pulmonary Edema Caused by Increased Membrane Permeability. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 1983, 36, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.A. Lung Ultrasound in the Critically Ill. Ann Intensive Care 2014, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussuges, A.; Coulange, M.; Bessereau, J.; Gargne, O.; Ayme, K.; Gavarry, O.; Fontanari, P.; Joulia, F. Ultrasound Lung Comets Induced by Repeated Breath-Hold Diving, a Study in Underwater Fishermen. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2011, 21, e384–e392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambrik, Z.; Monti, S.; Coppola, V.; Agricola, E.; Mottola, G.; Miniati, M.; Picano, E. Usefulness of Ultrasound Lung Comets as a Nonradiologic Sign of Extravascular Lung Water. The American Journal of Cardiology 2004, 93, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, Y. Relationship between Muscle Oxygenation Kinetics and the Rate of Decline in Peak Torque during Isokinetic Knee Extension in Acute Hypoxia and Normoxia. Int J Sports Med 2008, 29, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.-A.; Rudenski, A.; Gibson, J.; Howard, L.; O’Driscoll, R. Relating Oxygen Partial Pressure, Saturation and Content: The Haemoglobin-Oxygen Dissociation Curve. Breathe (Sheff) 2015, 11, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schagatay, E. Predicting Performance in Competitive Apnea Diving. Part III: Deep Diving. Diving Hyperb Med 2011, 41, 216–228. [Google Scholar]

- Marabotti, C.; Pingitore, A. Immersion-Related Atelectasis: A Possible Role in the Elusive Complications of Deep Breath-Hold Diving. Journal of Applied Physiology 2023, 135, 1388–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, S.R. Ventilation/Perfusion Relationships and Gas Exchange: Measurement Approaches. Compr Physiol 2020, 10, 1155–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascha, E.J.; Vetter, T.R. Significance, Errors, Power, and Sample Size: The Blocking and Tackling of Statistics. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2018, 126, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).