Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

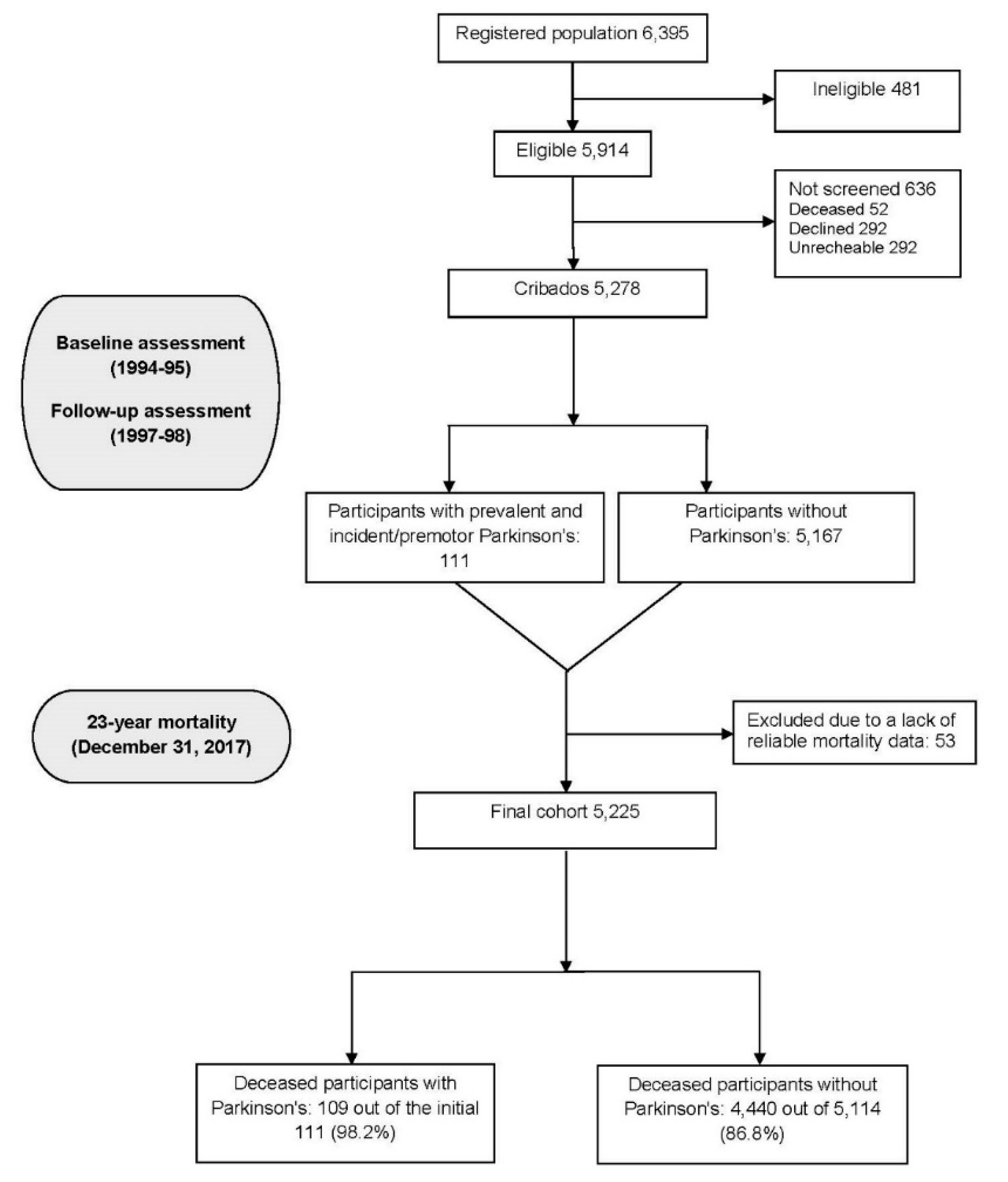

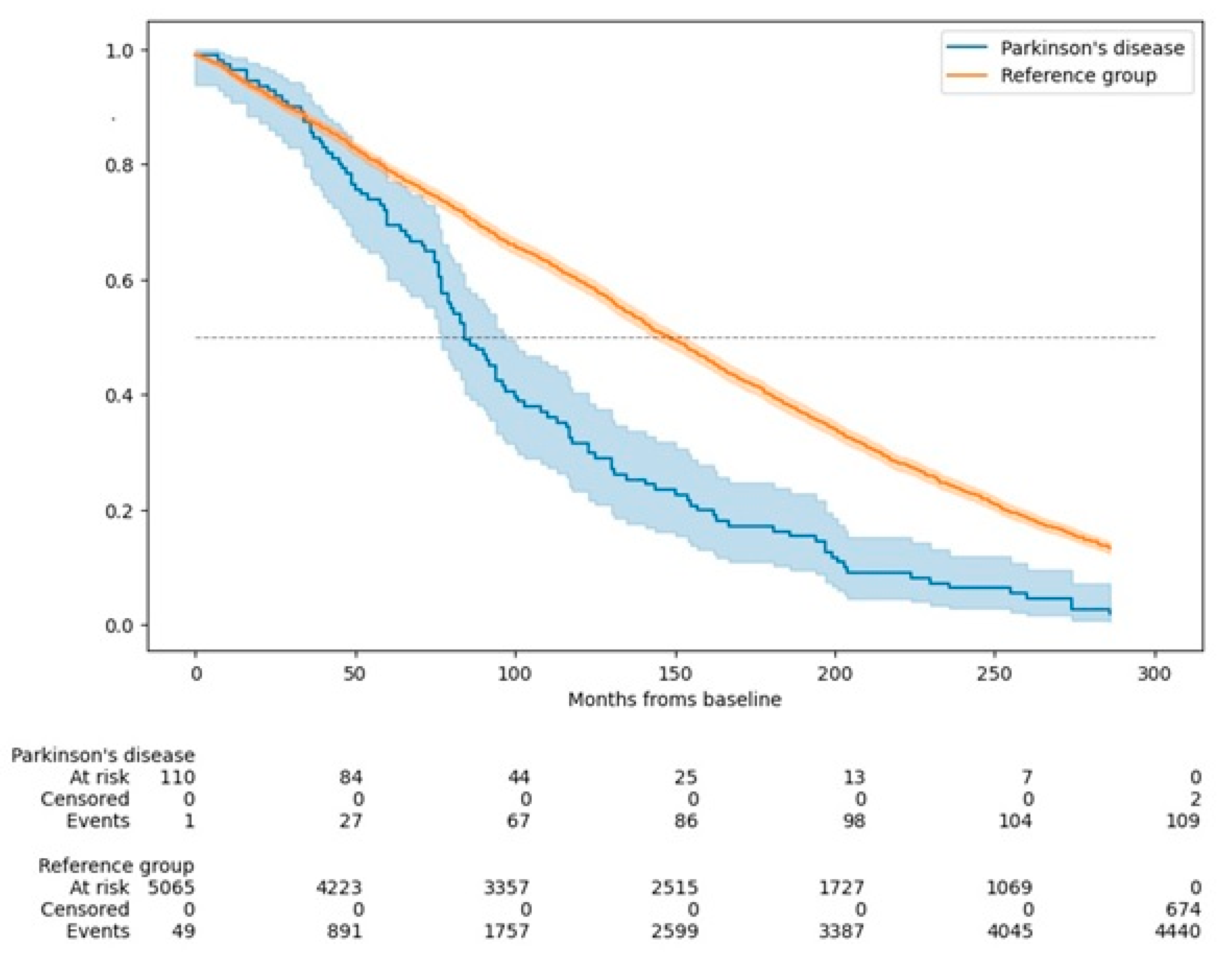

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a prevalent neurodegenerative disorder in older adults, yet its long-term mortality impact remains inadequately defined. This study builds on prior findings from the Neurological Disorders in Central Spain (NEDICES) cohort, extending mortality analysis to a 23-year follow-up within a Spanish population-based sample. This prospective cohort study included 5,278 individuals aged 65 years and older. Conducted in two waves (baseline and follow-up), it identified 81 prevalent PD cases at baseline (1994-95) and 30 incident (premotor) cases at follow-up (1994-95). Mortality was tracked for up to 23 years, with Cox proportional hazard models used to estimate mortality hazard ratios (HRs), adjusted for demographic and clinical variables. Among 111 PD cases, 109 (98.2%) died during follow-up, compared to 4,440 (86.8%) of 5,114 without PD. PD was associated with a significantly increased mortality risk (adjusted HR=1.62; 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.31–2.01). Individuals with both PD and dementia had an even higher risk (HR=2.19; 95% CI=1.24–3.89). Younger-onset PD (<65 years) showed heightened mortality risk (HR=2.11; 95% CI=1.22–3.64). Cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases were the leading causes of death in both PD and non-PD participants. PD was significantly more often listed as the primary cause of death in PD individuals compared to the reference group (14.7% vs. 0.4%, p<0.001). PD significantly increases mortality risk over 23 years, particularly among those with early onset and dementia. These findings support a multidisciplinary PD care approach that addresses both motor and non-motor symptoms to improve long-term outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical Aspects

2.2. Study Areas

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

Funding Sources and Conflict of Interest

Ethical aspects

Authors Roles:

Acknowledgments

References

- Bloem BR, Okun MS, Klein C. Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet 2021, 397, 2284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Gong DD, Man CF, Fan Y. Parkinson’s disease and risk of mortality: meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Neurol Scand 2014, 129, 71–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macleod AD, Taylor KSM, Counsell CE. Mortality in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Movement Disorders 2014, 29, 1615–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino YC, Cabral LM, Miranda NC, et al. Respiratory disorders of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurophysiol 2022, 127, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pablo-Fernández E, Lees AJ, Holton JL, Warner TT. Prognosis and Neuropathologic Correlation of Clinical Subtypes of Parkinson Disease. JAMA Neurol 2019, 76, 470–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommershuijsen LJ, Darweesh SKL, Ben-Shlomo Y, Kluger BM, Bloem BR. The elephant in the room: critical reflections on mortality rates among individuals with Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2023, 9, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada IJ, Benito-León J, Louis ED, et al. Mortality from Parkinson’s disease: A population-based prospective study (NEDICES). Movement Disorders 2011, 26, 2522–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito-León J, Porta-Etessam J, Bermejo F. [Epidemiology of Parkinson disease]. Neurologia 1998, 13 (Suppl 1), 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Benito-Leon, J. [Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease in Spain and its contextualisation in the world]. Rev Neurol 2018, 66, 125–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ebmeier KP, Calder SA, Crawford JR, Stewart L, Besson JA, Mutch WJ. Parkinson’s disease in Aberdeen: survival after 3.5 years. Acta Neurol Scand 1990, 81, 294–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Marmot MG. Survival and cause of death in a cohort of patients with parkinsonism: possible clues to aetiology? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 1995, 58, 293–9. [Google Scholar]

- Morens DM, Davis JW, Grandinetti A, Ross GW, Popper JS, White LR. Epidemiologic observations on Parkinson’s disease: Incidence and mortality in a prospective study of middle-aged men. Neurology 1996, 46, 1044–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis ED, Marder K, Cote L, Tang M, Mayeux R. Mortality From Parkinson Disease. Archives of Neurology 1997, 54, 260–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger K, Breteler MM, Helmer C, et al. Prognosis with Parkinson’s disease in europe: A collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Neurology 2000, 54 (Suppl 5), Suppl–5. [Google Scholar]

- Donnan PT, Steinke DT, Stubbings C, Davey PG, MacDonald TM. Selegiline and mortality in subjects with Parkinson’s disease: a longitudinal community study. Neurology 2000, 55, 1785–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgante L, Salemi G, Meneghini F, et al. Parkinson disease survival: a population-based study. Arch Neurol 2000, 57, 507–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fall P-A, Saleh A, Fredrickson M, Olsson J-E, Granérus A-K. Survival time, mortality, and cause of death in elderly patients with Parkinson’s disease: a 9-year follow-up. Mov Disord 2003, 18, 1312–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lau LML, Schipper CMA, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MMB. Prognosis of Parkinson Disease: Risk of Dementia and Mortality: The Rotterdam Study. Arch Neurol 2005, 62, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsaa EB, Larsen JP, Wentzel-Larsen T, Alves G. What predicts mortality in Parkinson disease?: A prospective population-based long-term study. Neurology 2010, 75, 1270–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savica R, Grossardt BR, Bower JH, et al. Survival and Causes of Death Among People With Clinically Diagnosed Synucleinopathies With Parkinsonism: A Population-Based Study. JAMA Neurol 2017, 74, 839–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson P, Meara J. Mortality and quality of death certification in a cohort of patients with Parkinson’s disease and matched controls in North Wales, UK at 18 years: a community-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keener AM, Paul KC, Folle A, Bronstein JM, Ritz B. Cognitive Impairment and Mortality in a Population-Based Parkinson’s Disease Cohort. J Parkinsons Dis 2018, 8, 353–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogland J, Post B, De Bie RMA. Overall and Disease Related Mortality in Parkinson’s Disease – a Longitudinal Cohort Study. JPD 2019, 9, 767–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales JM, Bermejo FP, Benito-León J, et al. Methods and demographic findings of the baseline survey of the NEDICES cohort: a door-to-door survey of neurological disorders in three communities from Central Spain. Public Health 2004, 118, 426–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermejo-Pareja F, Benito-León J, Vega-Q S, et al. [The NEDICES cohort of the elderly. Methodology and main neurological findings]. Rev Neurol 2008, 46, 416–23. [Google Scholar]

- Vega S, Benito-León J, Bermejo-Pareja F, et al. Several factors influenced attrition in a population-based elderly cohort: Neurological disorders in Central Spain Study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2010, 63, 215–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo-Pareja F, Benito-León J, Vega S, et al. Consistency of clinical diagnosis of dementia in NEDICES: A population-based longitudinal study in Spain. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2009, 22, 246–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermejo-Pareja F, Benito-León J, Vega S, Medrano MJ, Román GC. Neurological Disorders in Central Spain (NEDICES) Study Group. Incidence and subtypes of dementia in three elderly populations of central Spain. J Neurol Sci 2008, 264, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-León J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Morales J, Vega S, Molina J. Prevalence of essential tremor in three elderly populations of central Spain. Movement Disorders 2003, 18, 389–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito-León J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Louis ED. Incidence of essential tremor in three elderly populations of central Spain. Neurology 2005, 64, 1721–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-León J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Rodríguez J, et al. Prevalence of PD and other types of parkinsonism in three elderly populations of central Spain. Movement Disorders 2003, 18, 267–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-León J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Morales-González JM, et al. Incidence of Parkinson disease and parkinsonism in three elderly populations of central Spain. Neurology 2004, 62, 734–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Guzmán J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Benito-León J, Vega S, Gabriel R, Medrano MJ. Prevalence of Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack in Three Elderly Populations of Central Spain. Neuroepidemiology 2008, 30, 247–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Salio A, Benito-León J, Díaz-Guzmán J, Bermejo-Pareja F. Cerebrovascular disease incidence in central Spain (NEDICES): A population-based prospective study. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2010, 298, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- the ILSA Group, Maggi S, Zucchetto M, et al. The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging (ILSA): Design and methods. Aging Clin Exp Res 1994, 6, 464–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo F, Gabriel R, Vega S, Morales JM, Rocca WA, Anderson DW. Problems and Issues with Door-To-Door, Two-Phase Surveys: An Illustration from Central Spain. Neuroepidemiology 2001, 20, 225–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahn, S. Members of the UPDRS Development Committee. Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale [Internet]. 1987. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:203500896.

- American Psychiatric Association. APAssociation Task Force on DSM-IV,. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression, and mortality. 1967. Neurology 2001, 57 (Suppl 3), S11–26.

- Carey IM, Shah SM, Harris T, DeWilde S, Cook DG. A new simple primary care morbidity score predicted mortality and better explains between practice variations than the Charlson index. J Clin Epidemiol 2013, 6, 436–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fereshtehnejad S-M, Yao C, Pelletier A, Montplaisir JY, Gagnon J-F, Postuma RB. Evolution of prodromal Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: a prospective study. Brain 2019, 142, 2051–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diederich NJ, Sauvageot N, Pieri V, Hipp G, Vaillant M. The Clinical Non-Motor Connectome in Early Parkinson’s Disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2020, 10, 1797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siderowf A, Stern MB. Premotor Parkinson’s disease: clinical features, detection, and prospects for treatment. Ann Neurol 2008, 64 (Suppl 2), S139–147.

- Siderowf A, Lang AE. Premotor Parkinson’s disease: concepts and definitions. Mov Disord 2012, 27, 608–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy G, Tang M-X, Louis ED, et al. The association of incident dementia with mortality in PD. Neurology 2002, 59, 1708–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano A, Canning CG, Hausdorff JM, Lord S, Rochester L. Falls in Parkinson’s disease: A complex and evolving picture. Movement Disorders 2017, 32, 1524–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley DJ, Myint PK, Gray RJ, Deane KHO. Systematic review on factors associated with medication non-adherence in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2012, 18, 1053–61. [Google Scholar]

- Cereda E, Cilia R, Klersy C, et al. Dementia in Parkinson’s disease: Is male gender a risk factor? Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2016, 26, 67–72.

- Hoogland J, Boel JA, De Bie RMA, et al. Risk of Parkinson’s disease dementia related to level I MDS PD-MCI. Movement Disorders 2019, 34, 430–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickremaratchi MM, Ben-Shlomo Y, Morris HR. The effect of onset age on the clinical features of Parkinson’s disease. Euro J of Neurology 2009, 16, 450–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano G, Ferrara N, Brooks DJ, Pavese N. Age at onset and Parkinson disease phenotype. Neurology 2016, 86, 1400–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter B, Diem-Zangerl A, Wenning GK, et al. Mortality in Parkinson’s disease: A 38-year follow-up study. Movement Disorders 2015, 30, 266–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-León J, Louis ED, Villarejo-Galende A, Romero JP, Bermejo-Pareja F. Under-reporting of Parkinson’s disease on death certificates: A population-based study (NEDICES). Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2014, 347, 188–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomber R, Alshameeri Z, Masia AF, Mela F, Parker MJ. Hip fractures and Parkinson’s disease: A case series. Injury 2017, 48, 2730–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burchill E, Watson CJ, Fanshawe JB, et al. The impact of psychiatric comorbidity on Parkinson’s disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2024, 39, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong CT, Hu HH, Chan L, Bai C-H. Prevalent cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease in people with Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. CLEP 2018, 10, 1147–54. [Google Scholar]

- Caspell-Garcia C, Simuni T, Tosun-Turgut D, et al. Multiple modality biomarker prediction of cognitive impairment in prospectively followed de novo Parkinson disease. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0175674. [Google Scholar]

- Fereshtehnejad S-M, Zeighami Y, Dagher A, Postuma RB. Clinical criteria for subtyping Parkinson’s disease: biomarkers and longitudinal progression. Brain 2017, 140, 1959–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espay AJ, Kalia LV, Gan-Or Z, et al. Disease modification and biomarker development in Parkinson disease: Revision or reconstruction? Neurology 2020, 94, 481–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Study | Cohort Characteristics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Ebmeier et al.10 | 267 patients and 233 matched controls in Scotland were followed for 3.5 years | The ratio of mortality risks for patients and controls was 2.35. Factors predicting death included cognitive impairment, older age, late disease onset, long-term smoking, low blood pressure, and Parkinson's-related mobility issues |

| 1995 | Ben-Shlomo & Marmot11 | 220 Parkinson’s disease patients and 421 matched controls in the UK were followed for 20 years | Parkinson's disease was associated with increased mortality (adjusted hazard ratio = 2.6); cerebrovascular and ischemic heart disease deaths were higher in Parkinson's disease. |

| 1996 | Morens et al.12 | 8,006 middle-aged men from the Honolulu Heart Study were followed for 29 years | Mortality increased 2-3 times in Parkinson's disease; survival was reduced by 8 years compared to controls. |

| 1997 | Louis et al.13 | 288 patients, Manhattan, USA | The risk of mortality, when compared with nondemented elderly subjects, was highest among those with both PD and dementia (rate ratio, 4.9). Dementia and extrapyramidal symptoms strongly influenced risk. |

| 2000 | Berger et al.14 | Pooled analysis of five European population-based cohorts (16,143 participants) | The relative risk of death in Parkinson's disease = 2.3; increased institutionalization and mortality risks, especially in men. |

| 2000 | Donnan et al.15 | 97 Parkinson's disease patients in Scotland | Mortality in Parkinson's disease doubled (Rate Ratio = 1.76); higher mortality with levodopa monotherapy (Rate Ratio = 2.45). |

| 2000 | Morgante et al.16 | 59 patients and 118 matched controls in Sicily, Italy, were followed for 8 years. | Parkinson's disease mortality was significantly higher, with a relative risk of 2.3; pneumonia was the most common cause of death. |

| 2003 | Fall et al.17 | 170 Parkinson’s disease patients and 510 matched controls in Sweden were followed for 9 years | The mortality rate ratio was 1.6 when comparing PD patients with controls. There was a significant increase in deaths from pneumonia |

| 2005 | de Lau et al.18 (Rotterdam Study) | 6,969 participants, 99 prevalent, 67 incident Parkinson's disease cases | Increased mortality risk (Hazard ratio = 1.83). Within PD cases, mortality risk was influenced by disease duration and by occurrence of dementia |

| 2010 | Forsaa et al.19 | 230 Parkinson's disease patients, followed from 1993 to 2009, Norway | Median survival was 15.8 years; mortality predictors included higher age at motor onset, older age, male sex, more severe motor impairment, psychotic symptoms, and dementia. |

| 2011 | Posada et al.7 (NEDICES Study) | 5,262 elderly participants, 81 Parkinson's disease cases, Spain, 13-year follow-up | Parkinson's disease mortality was higher (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.75); dementia further increased the risk (adjusted hazard ratio = 2.60). |

| 2017 | Savica et al.20 | 461 patients with synucleinopathies, Minnesota, USA | Parkinson's disease was associated with moderately increased mortality (Hazard Ratio = 1.75); multiple system atrophy with parkinsonism showed the highest mortality (Hazard Ratio = 10.51). |

| 2018 | Hobson & Meara21 | 166 Parkinson's disease patients and 102 controls, followed for 18 years at Wales | Compared with the general UK population, individuals with Parkinson's disease had a higher risk of mortality, with a standardized mortality ratio of 1.82. The most common causes of death were pneumonia and cardiac-related conditions. |

| 2018 | Keener et al.22 | 360 Parkinson's disease patients, new-onset cohort, California, mean follow-up of 5.8-years | Cognitive impairment, older age at diagnosis, and motor subtype (postural instability and gait difficulty associated with higher risk; HR = 0.58 for tremor-dominant subtype) were significant predictors of mortality. |

| 2019 | Hoogland et al.23 | 133 newly diagnosed Parkinson's disease patients in the Netherlands followed for at least 13 years. | Increased mortality associated with mild cognitive impairment, higher levodopa dose, and earlier onset. |

| Parkinson’s disease (N = 111) | Without Parkinson’s (N = 5,114) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 76.5 ± 5.7 (76.0) | 74.3 ± 7.0 (73.0) | <0.001 |

| Sex (female) | 49 (44.1%) | 2,949 (57.7%) | 0.004 |

| Study area | 0.359 | ||

| - Arévalo | 47 (42.3%) | 1,874 (36.6%) | |

| - Las Margaritas | 31 (27.9%) | 1,725 (33.7%) | |

| - Lista | 33 (29.6%) | 1,515 (29.6%) | |

| Education in years of study completed * | 5.7 ± 7.1 (6.0) | 6.0 ± 5.3 (6.0) | 0.270 |

| Smoking habit* | 0.118 | ||

| - Smoker | 5 (5.4%) | 489 (12.2%) | |

| - Ex-smoker | 29 (31.5%) | 1,068 (26.7%) | |

| - Never smoked | 58 (63.0%) | 2,436 (61.0%) | |

| Alcohol consumption* | 0.233 | ||

| - Regular drinker | 23 (25.0%) | 1,334 (33.4%) | |

| - Ex-drinker | 21 (22.8%) | 830 (20.8%) | |

| - Never drank | 48 (52.2%) | 1,825 (45.8%) | |

| Arterial hypertension* | 62 (56.4%) | 2,483 (51.0%) | 0.267 |

| Comorbidity Index | 1.6 ± 1.8 (1.0) | 1.1 ± 1.5 (0.0) | 0.005 |

| Dementia | 14 (12.6%) | 291 (5.7%) | 0.002 |

| Alive (N = 676) | Deceased (N = 4,549) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 68.9 ± 3.9 (68.0) | 75.1 ± 7.0 (74.0) | <0.001 |

| Sex (female) | 460 (68.0%) | 2,538 (55.8%) | <0.001 |

| Study area | 0.006 | ||

| - Arévalo | 211 (31.2%) | 1,710 (37.6%) | |

| - Las Margaritas | 249 (36.8%) | 1,507 (33.1%) | |

| - Lista | 216 (32.0%) | 1,332 (29.3%) | |

| Education in years of study completed * | 6.8 ± 5.7 (7.0) | 5.9 ± 5.3 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Smoking habit* | 0.002 | ||

| - Smoker | 62 (10.8%) | 432 (12.3%) | |

| - Ex-smoker | 125 (21.7%) | 972 (27.7%) | |

| - Never smoked | 388 (67.5%) | 2,106 (60.0%) | |

| Alcohol consumption* | 0.050 | ||

| - Regular drinker | 208 (36.3%) | 1,149 (32.8%) | |

| - Ex-drinker | 99 (17.3%) | 752 (21.4%) | |

| - Never drank | 266 (46.4%) | 1,607 (45.8%) | |

| Arterial hypertension* | 254 (38.4%) | 2,291 (53.1%) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity Index | 0.6 ± 1.0 (0.0) | 1.2 ± 1.6 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| A. Mortality hazard ratios in Parkinson's disease patients versus those without Parkinson's disease | ||||||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||||||

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | Valor p | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | |||||

| Parkinson's disease patients (N=111) | 1.91 | 1.58-2.32 | <0.001 | 1.56 | 1.29-1.89 | <0.001 | 1.64 | 1.33-2.04 | <0.001 | 1.62 | 1.31-2.01 | <0.001 | ||||

| Participants without Parkinson's disease (N = 5,114) (reference group) | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | ||||

| B. Mortality hazard ratios in Parkinson's disease patients, stratified by the presence or absence of dementia | ||||||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||||||

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | |||||

| Parkinson's disease patients with dementia (N = 14) | 4.27 | 2.52-7.23 | <0.001 | 2.13 | 1.26-3.62 | 0.005 | 2.19 | 1.24-3.88 | 0.007 | 2.19 | 1.24-3.89 | 0.007 | ||||

| Parkinson's disease patients without dementia (N = 97) | 1.77 | 1.44-2.17 | <0.001 | 1.50 | 1.23-1.84 | <0.001 | 1.58 | 1.26-1.99 | <0.001 | 1.56 | 1.24-1.96 | <0.001 | ||||

| Participants without either condition (N = 5,114) (reference group) | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | ||||

| C. Mortality hazard ratios in Parkinson's disease patients, stratified by disease onset | ||||||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||||||

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | |||||

| Parkinson's disease onset at age 65 or later (N = 92) | 1.87 | 1.52-2.30 | <0.001 | 1.46 | 1.19-1.80 | <0.001 | 1.58 | 1.25-1.99 | <0.001 | 1.56 | 1.24-1.97 | <0.001 | ||||

| Parkinson's disease onset before age 65 (N = 19) | 2.16 | 1.38-3.40 | <0.001 | 2.32 | 1.48-3.66 | <0.001 | 2.15 | 1.25-3.71 | 0.006 | 2.11 | 1.22-3.64 | 0.007 | ||||

| Participants without Parkinson's disease (N = 5,114) (reference group) | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | 1.0 | _ | 1.0 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).