Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

About the Terminology

Geophagy

Humans

Humans and Animals

Lithophagy-Geophagy

Birds and Mammals

Conclusions

- The instinctive desire to eat earthy substances, products of hypergenic transformation of various rocks, preserved in many groups of animals and partly in humans, is, in its most general form, a manifestation of the evolutionarily conditioned way of regulating the material composition of the internal environment, as well as some biological and physiological processes in the body.

- There are two varieties of instinctive geophagy-lithophagy, which define two types of self-regulation of organisms with the help of natural minerals and earthy substances of complex composition.

- 3.

- The main cause of geophagy-lithophagy in humans and animals is to maintain the required concentration and ratio of rare earth elements in the neuroimmunoendocrine system of the body. This control center of metabolic and immune defense processes in any organism is largely based on the unique physicochemical properties of f-electron atoms of REE, not all seventeen, but at best a few, perhaps six of them. The role of such atoms in the organism is only beginning to be studied. According to the available data, it is determined by the effects on ionotropic receptors. The tendency to regulate REE in the body, in fact, to geophagy, is controlled by the development of specific hormonal stress.

- 4.

- The complexity of maintaining the necessary ratio and concentration of REE in the body consists not only in the fact that all these elements without exception can be integrated into biological structures, but not all of them are capable of performing the functions required by the body. The complexity also lies in the fact that all REE necessary for the body, as well as all other vital elements, follow the law of "threshold" concentrations according to V.V. Kovalsky (1974), i.e. such concentrations above or below which metabolic regulation is disturbed, which is accompanied by dysfunction of life-support systems and, as a result, persistent metabolic disorders with the transition of the body to the state of endemic geochemically determined disease. The nature of REE endemias seems to be determined on the one hand by the ratios and concentrations of REE entering the internal environment of the body, and on the other hand by the genetic characteristics of organisms that have recently settled or have lived for a long time in landscapes that are REE-anomalous for a given organism.

- 5.

- The effect of minerals on any living body is multifactorial and not always positive. The complete list of mineral effects on living systems is presented in a separate table (see Table 1).

- 6.

- Sometimes the need for geophagy in animals (possibly also in humans) may not be related to the regulation of rare earth elements in the body, but is determined by the need to regulate their internal environment based on other functions that the mineral-crystalline substances have.

- 7.

- Instinctive geophagy in animals (especially in mammals) usually acquires traditional forms with long visits to the same places over centuries and millennia, resulting in the formation of specific landscape complexes, which we call by the term "kudurs". Kudurs, as places of wildlife concentration, have always been used by humans for hunting animals.

Acknowledgments

References

- Abrahams P.W. (1997) Geophagy (soil consumption) and iron supplementation in Uganda // Trop. Med. Int. Health. Vol. 2. No 7. Р. 23–617.Abrahams P.W. The Chemistry and Mineralogy of Three Savanna Lick Soils // Journal of Chemical Ecology,1999, V. 25, Is. 10, pp. 2215-2228.

- Abrahams P.W., Parsons J.A. (1996) Geophagy in the Tropics: a literature eview // Geogr. J. Vol. 162. P. 63–72.

- Аiler R.K. (1982) The Chemistry of Silica: Solubility, Polymerization, Colloid and Surface Properties and Biochemistry of Silica. Part I. Moscow: Mir. 416 p. (Russian Edition translated from Iler R.K., 1979).

- Аnell B., Lagercrantz S. (1958) Gefagical customs // Stud. ethnogr. upsal. Vol. 17. 98 p.

- Anitha J.K., Joseph Sabu, Rejith R.G., Sundararajan M. (2020) Monazite chemistry and its distribution along the coast of Neendakara-Kayamkulam belt, Kerala, India // SN Applied Sciences 2:812. [CrossRef]

- Aufreiter S., Hancock R.G.V., Mahanev W.C., Stambolic-Robb A., Sanmugadas K. (1997) Geochemistry and mineralogy of soils eaten by humans // J. Food Sciences and Nutrition V.48. P.293-305.

- Avtsyn A.P., Zhavoronkov A.A., Rish M.A., Strochkova L.S. (1991) Human microelementoses. Moscow: Medicine. 496 p. (In Russian).

- Banenzoue C., Signing P., Mbey Jean-Aimé, Njopwouo D. (2014) Antacid power and their enhancements in some edible clays consumed by geophagia in Cameroon // Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research, 6 (10): 668-676. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282154824.

- Baranovskaya N.V., Mazukhina S.I., Panichev A.M. et al. (2024) Features of chemical elements migration in natural waters and their deposition in the form of neocrystallisations in living organisms (physico-chemical modeling with animal testing) // Bulletin of the Tomsk Polytechnic University. Geo Аssets Engineering. V. 335. No. 2. P. 187-201. [CrossRef]

- Belyanovskaya A.I. (2019) Elemental composition of the organism of mammals of natural and man-made territories and their ranking using the USETOX model // Dissertation for the degree of candidate of geological and mineralogical sciences. Tomsk-Bordeaux, 22 c. (In Russian).

- Bgatov V.I., Motovilov K.Ya., Speshilova M.A. (1987) Functions of natural minerals in metabolic processes of agricultural poultry. Agricultural Biology, No 7, pp. 98-102. (In Russian).

- Brightsmith D.J., Taylor J., Phillips T.D. (2008) The Roles of Soil Characteristics and Toxin Adsorption in Avian Geophagy // Biotropica, V. 40(6). P.766-774. [CrossRef]

- Brightsmith D.J., Hobson E.A., Martinez G. (2017) Food availability and breeding season as predictors of geophagy in Amazonian parrots // Ibis 18 p. [CrossRef]

- Brouziotis A.A., Giarra A., Libralato G., Pagano G., Guida M., Trifuoggi M. (2022) Toxicity of rare earth elements: An overview on human health impact // Frontiers in Environmental Science. [CrossRef]

- Browman D.L., Gundersen J.N. (1993) Altiplano Comestible Earths: Prehistoric and Historie Geophagy of Highland Peru and Bolivia // Geoarchaeology: An International Journal, Vol. 8, No. 5, 413-425.

- Brown C.J., Chenery S.R., Smith B., Mason C., Tomkins A., Roberts G.J. et al. (2004) Environmental influences on the trace element content of teeth – Implications for disease and nutritional status // Arch. Oral Biol. Vol. 49. Is. 9. P. 705-717.

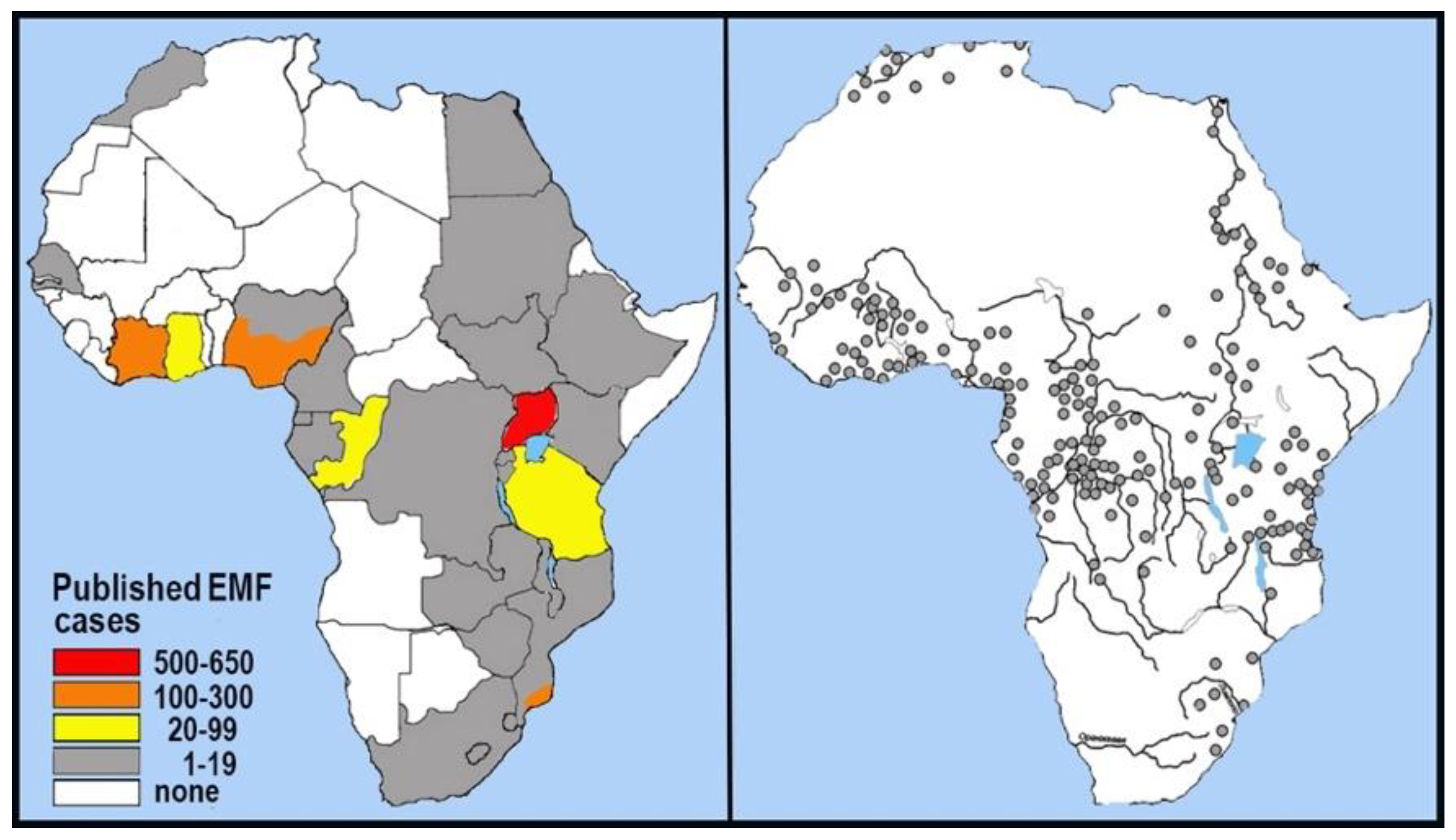

- Bukhman G., Ziegler J., Parry E. (2008) Endomyocardial Fibrosis: Still a Mystery after 60 Years //www.plosntds.org 2008 Volume 2 Issue 2 e97.

- Cheek D.B., Smith R.M., Spargo R.M., Francis N. (1981) Zinc, copper and environmental factors in the Aboriginal peoples of the north-west // Aust. N. J. Med. Vol. 2. P. 508–512.

- Cheng Y., You L., Rongchang L., Wang K., Yao H. (1999) The uptake of cerium by erythrocytes and the changes of membrane permeability in CeCl3 feeding rats // Progress in Natural Science, 9:610-616.

- Chung E.O., Mattah B., Hickey M.D., Salmen C.R., Milner E.M., Bukusi E.A., Brashares J.S., Young S.L., Fernald L.C.H., Fiorella K.J. (2019) Characteristics of Pica Behavior among Mothers around Lake Victoria, Kenya: A Cross-Sectional Study// Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 16, 2510. [CrossRef]

- Collignon R. (1992) А propos des troubles des conduites alimentaires du pica des médecins à la géophagie des géographes, des voyageurs et des ethnologues // Psychopathologie africaine, Vol. XXIV. Is. 3. P. 385-396.

- Cragin F.W. (1836) Observations on Cachexia Africana or dirt-eating //Am. J. Med. Sci. Vol. 17. P. 356–364.

- Curtlius M.F., Millican F.K., Layman E.M. et. al. (1963) Treatment of Rica with a vitamin and mineral supplement // Amer. J. Clin. Nutr. Vol. 12. P. 388–393.

- Dominy N.J., Davoust E., Minekus M. (2004) Adaptive function of soil consumption: An in vitro study modelling the human stomach and small intestine. Journal of Experimental Biology, 207: 319-324.

- Downs C.T (2006) Geophagy in the African Olive Pigeon (Columba arquatrix) // Ostrich, V. 77(1-2) P.40-44. [CrossRef]

- Dravert P.L. (1922) On lithophagy // Siberian Nature. No 1. P. 3-6. (In Russian).

- Dreyer M.J., Chaushev P.G., Gledhill R.F. (2004) Biochemical investigations in geophagia // J. Royal Soc. Med. Vol. 97 P. 48.

- Dubinin A.V. (2006) Geochemistry of rare earth elements in the ocean. Moscow: Nauka. 360 p. (In Russian).

- Duplex K. K. E., Wouatong Armand Sylvain Ludovic, Njopwouo Daniel, Ekosse Georges Ivo. (2018) Physico-chemical Characterization of Clayey Materials Consumed by Geophagism in Locality of Sabga (North-western Cameroon): Health Implications // International Journal of Applied Science and Technology, V. 8, No.3. P.57-68. [CrossRef]

- Eapen J.T. (1998) Elevated Levels of Cerium in Tubers from Regions Endemic for Endomyocardial Fibrosis (EMF) // Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 60:168-170.

- Edwards A.A., Mathura C.B., Edwards C.H. (1983) Effects of maternal geophagia on infant and juvenile rats // J. Nat. Medical Assoc., Vol. 75, №. 9. P. 895-902.

- Eisele G.R., Mraz F.R., Woody M.C. (1980) Gastrointestinal uptake and 144Ce in the neonatal mouse, rat and pig. Health Physics, 39:185-192.

- Ekosse G.E., Ngole V.M., Longo-Mbenza B. (2011) Mineralogical and geochemical aspects of geophagic clayey soils from the Democratic Republic of Congo // International Journal of the Physical Sciences, Vol. 6. Is. 31. P. 7302-7313.

- Ekosse G.I., Chistyakov K.V., Rozanov A.B. et al., (2020) Landscape Settings and Mineralogy of Some Geophagic Clay Occurrences in South Africa /O.V. Frank-Kamenetskaya et al. (eds.), Processes and Phenomena on the Boundary Between Biogenic and Abiogenic Nature, Lecture Notes in Earth System Sciences, pp 785-801. [CrossRef]

- Feidman M.D. (1986) Pica: current perspectives // Psychosomat. No 27. P. 519–523.

- Feng L., Xiao H., He X., et al. (2006) Neurotoxicological consequence of long-term exposure to lanthanum // Toxicology Letters. Vol. 165. P. 112-120.

- Fiddler G., Tanaka T., Webster I. Low systemic adsorption and excellent tolerability during administration of Lanthanum carbonate (FosrenolTM) for 5 days. In 9th Asian Pacific Congress of Nephrology, 19- 20. Februar 2003, Pattaya, Thailand, 2003.

- Fleming C.A. (1951) Sea Lions as Geological Agents // Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, V.21, No. 1. P. 22-25.

- Ferrell R.E., Vermeer D.E., LeBlanc W.S. (1985) Chemical and mineralogical composition of geophagical materials // Trace substances in environ. health XIX. Univ. Missouri, Р. 47–55.

- Gebel A.D. (1862) About earthy substances used for food in Persia // Notes of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. St. Petersburg. Vol. 2. P. 126-135.

- Geissler P.W., Shulman C.E., Prince R.J., Mutemi W., Mnazi C., Friis H., Lowe B. (1998): Geophagy, iron status and anaemia among pregnant woman on the coast of Kenya // Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg., 92. P.549-553.

- Ghanem S.J. Geophagy of tropical fruit-eating bats – mineral licks as a link between ecology and conservation // Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades des Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.). 2012. 127 p.

- Gilardi J.D., Duffey S.S., Munn C.A., Tell L. (1999). Biochemical functions of geophagy in parrots: detoxification of dietary toxins and cytoprotective effects // J. Chem Ecol., 25. Р.897-922.

- Gilbertson M.L., Brandell E.E., et al. (2022) Сause of death, pathology, and chronic wasting disease status of white-tailed deer (Оdocoileus virginianus) mortalities in Wisconsin, USA // Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 58(4), pp. 803–815. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Aracena, J., Riemersma, R. A., Gutiérrez-Bedmar, M., Bode, P., Kark, J. D., Garcia-Rodríguez, A., et al. (2006). Toenail cerium levels and risk of a first acute myocardial infarction: The EURAMIC and heavy metals study. Chemosphere 64, 112–120. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths B.M., Jin Yan, Griffiths L.G., Gilmore M.P. (2022) Physical, landscape, and chemical properties of Amazonian interior forest mineral licks // Environ Geochem Health. [CrossRef]

- Gu W., Muhammad Farhan Ul Haque, DiSpirito A.A., Semrau J.D. (2016) Uptake and effect of rare earth elements on gene expression in Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b // FEMS Microbiol Lett. 363(13): fnw129. Epub 2016 May 12. [CrossRef]

- Henríquez-Hernández, L. A., Boada, L. D., Carranza, C., Pérez-Arellano, J. L., González-Antuña, A., Camacho, M., et al. (2017). Blood levels of toxic metals and rare Earth elements commonly found in e-waste may exert subtle effects on hemoglobin concentration in sub-Saharan immigrants. Environ. Int. 109, 20–28. [CrossRef]

- Henry J.M., Cring F.D. (2014) Geophagy аn Anthropological Perspective. Р. 179-198. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261362058.

- He M.L., Rambeck W.A. (2000) Rare earth elements – a new generation of growth promoters for pigs? Archives of Animal Nutrition, 53(4):323–334.

- He R., Xia Z. (2001) Effect of rare earth compounds added to diet on performance of growing- finishing pigs. World Wide Web, http://www.rare-earth-agri.com.cn/eng5.htm, 2001.accessed 15. July 2001.

- Hinz E. (1999) Formen der Geophagie und ihre Bedeutung für die Parasitologie // Tropenmed. Parasitol. Vol. 21. P. 1-14.

- Hladik, C. M., Gueguen, L. (1974) Géophagie et nutrition minérale chez les primates sauvages. Comptes Rendus de L’académie des Sciences Serie D, 279, 1393-1396.

- Hooda P.S., Henry C.J.K., Seyoum T.A., Armstrong L.D.M., Fowler M.B. (2004) The potential impact of soil ingestion on human mineral nutrition // Science of the Total Environment 333 75–87. [CrossRef]

- Hooper D., Mann H.H. (1906) Earth eating and the earth eating habit in India // Mem. Asiat. Soc. Bengal.Calcutta. Vol. 1. P. 249–270.

- Houston D.C., Gilardi J.D., Hall A.J. (2001). Soil consumption by elephants might help to minimize the toxic effects of plant secondary compounds in forest browse. Mammal. Review. Vol. 31. Is. 3-4. P. 249-254.

- Hutchison A.J., Albaaj F. (2005) Lanthanum carbonate for the treatment of hyperphosphataemia in renal failure and dialysis patients. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 6(2): 319–328.

- Khokhlov A.M. (1969) Arrangement of artificial pebble beds for upland game. In: Proceedings of the Zavidovsky reserve hunting farm. Vol. 1. Moscow: Voenizdat, pp. 291-297. (In Russian).

- Jiesheng L., Shen Zhiguo, Yang Weidong et al. (2002) Effact of Long-term Intake of Rare Earht in Drinking Water on Trace Elements in Brains of Mice // J. Rare Earths. Vol. 20. № 5.

- Johns T. (1986) Detoxification function of geophagy and domestication of the potato // J. Chem. Ecol. 12. P. 635–646.

- Johns T., Duquette M. (1991) Detoxification and mineral supplementation as functions of geophagy // American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 53: 448-456.

- Jones, Krishnamani, R., Mahaney W.C. (2000) Geophagy among primates: Adaptive significance and ecological consequences. Animal Behaviour, 59 (5), 899-915.

- José C.A., Donicer M.V., Mastoby M.M. Clinical diagnosis of allotrophagia in cattle of the department of Sucre Colombia // Colombiana Cienc Anim 2017; 9(2):141-146. [CrossRef]

- Kalyuzhnov V.T., Zlobina I.E., Nikulina P.G. (1988) Physiological justification of inclusion of zeolites in birds’ food. In: Use of zeolites from Siberia and the Far East in agriculture. Novosibirsk: Siberian Branch of the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences, pp. 15-20. (In Russian).

- Ketch L.A., Malloch D., Mahaney W.C., Huffman M.A. (2001) Comparative microbial analysis and clay mineralogy of soil eaten by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes Schweinfurhii) in Tanzania. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. Vol. 33. № 2. P. 199-203.

- Klaus G., Klaus-Hügi C., Schmid B. (1998) Geophagy by large mammals at natural licks in the rain forest of the Dzanga National Park, Central African Republic. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 14: 829-839.

- Klaus, G., Schmid B. (1998) Geophagy at natural licks and mammal ecology: a review. Mammalia, 62(4): 482-498.

- Knebel C. Untersuchungen zum Einfluss Seltener Erd-Citrate auf Leistungsparameter beim Schwein und die ruminale Fermentation im künstlichen Pansen (RUSITEC). Dissertation, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München, 2004.

- Knezevich, M. (1998) Geophagy as a therapeutic mediator of endoparasitism in a free-ranging group of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) // American Journal of Primatology, 44(1),71-82.

- Knudsen, J.W. (2002) Kula Udongo (earth eating habits): a social and cultural practice among Chagga Women on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro // Indilinga African Journ. Of Indigenous Knowledge Systems. V. 1. p.19-25. [CrossRef]

- Kostial K., Kargacin B., Landeka M. (1989) Gut retention of metals in rats. Biological Trace Element Research, 21:213-218.

- Kovalsky V.V. (1974) Geochemical ecology. Essays. Moscow: Nauka, 229 p. (In Russian).

- Kreulen D.A. (1985). Lick use by large herbivores: a review of benefits and banes of soil consumption. Mammal Rev. 15: 107-123.

- Krishnamani, R., Mahaney W.C. (2000) Geophagy among primates: Adaptive significance and ecological consequences. Animal Behaviour, 59 (5), 899–915. [CrossRef]

- Kutty V.R., Abraham S., Kartha C.C. (1996) Geographical distribution of endomyocardial fibrosis in South Kerala // Int. J. Epi. Vol. 25. No 6. P. 1202–1207.26.

- Lantseva N.N., Motovilov K.Ya. (2003) Influence of different high silica additives on the quality of poultry products. Advances in current natural sciences, No. 8, pp. 21-24. (In Russian).

- Lantseva, N.N. (2009) Experimental substantiation of the system of use of natural minerals-kudurits in feeding of agricultural poultry. Abstract of dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Agricultural Sciences. Novosibirsk, Altai State Agrarian University, 41 p. (In Russian).

- Laufer B. (1930) Geophagy Publications of the Field Museum of Natural History. Anthropological Series, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 99, 101-198.

- Lavelle M.J., Phillips G.E., Fischer J.W., Burke P.W., Seward N.W., Stahl R.S., Nichols T.A., Wunder B.A., VerCauteren K.C. (2014) Mineral licks: motivational factors for visitation and accompanying disease risk at communal use sites of elk and deer // Environ Geochem Health, V. 36(6). P. 1049-1061. [CrossRef]

- Lebedeva E., Panichev A., Kharitonova N., Kholodov A. Golokhvast К. (2020) Diversity, Abundance, and Some Characteristics of Bacteria Isolated from Earth Material Consumed by Wild Animals at Kudurs in the Sikhote-Alin Mountains, Russia // International Journal of Microbiology, Article ID 8811047, 9 pages. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.E., Hamman, M.G., Black, J.M. (2004) Grit-site selection of black brant: Particle size or calcium content? Wilson Bulletin, V.116, no. 4, pp. 304–313. [CrossRef]

- Li W., Li C., Jiang Z., Guo R. & Ping X. (2018) Daily rhythm and seasonal pattern of lick use in sika deer (Cervus nippon) in China// Biological Rhythm ReseaRch, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Wu, M., Zhang, L., Bi, J., Song, L., Wang, L., et al. (2019). Prenatal exposure of rare Earth elements cerium and ytterbium and neonatal thyroid stimulating hormone levels: Findings from a birth cohort study. Environ. Int. 133, 105222. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Calleja, M.V., Soto-Gamboa, A., Rezende, E.L. (2000) The role of gastrolites on feeding behavior and digestive efficiency in the rufous-collared sparrow. The Condor, vol. 102, no. 2, pp. 465-469. [CrossRef]

- Mahaney W.C. Hancock R.G.V. (1990) Geochemical nalysis of African buffalo geophagic sites and dung on Mount Kenya, East Africa // Mammalia, Vol. 54. Is.1. P. 25-32.

- Mahaney W.С., Milner M.W., Sunmugadas K. et al. (1997) Analysis of geophagy soils in Kibale Forest, Uganda // Primates, Vol. 38. Is. 2. P. 159-176.

- Mahaney W.C., Watts D., Hancock R.G.V. (1990) Geophagia by Mountain Gorillas (Gorilla gorilla beringei) in the Virunga Mountains, Rwanda // Primates, Vol. 31. Is.1. P. 113-120.

- Mahaney W.C., Zippin, J., Hancock R.G.V., Aufreiter S., Campbell S., Malloch D., Wink M., Huffman M.A. (1999) Chemistry, mineralogy and microbiology of termite mound soils eaten by the chimpanzees of the Mahale mountains, Western Tanzania // J. Tropical Ecology, Vol. 15. P. 565-588.

- Mahaney W.C., Milner M.W., Muliono H., Hancock R.G.V., Aufreiter S. (2000). Mineral and chemical analyses of soil eaten by humans in Indonesia // Int. J. Environm. Healht Research, Vol. 10. P. 93-109. [CrossRef]

- Makaridze N.G. (1986) Adsorption ability of zeolites to some proteolytic enzymes. Communications of the Academy of Sciences of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic, Vol. 122, No 3, pp. 621-623. (In Russian).

- Mason D. (1833) On atrophia a ventriculo (mal d’Estomac) or dirt-eating // Rdlnb. Med. S. J. Vol. 39. P. 95–289.

- May, T.A., Braun C.E. (1973) Gizzard stones from adult white-tailed ptarmigan (Lagopus leucurus) in Colorado. Arctic and Alpine Research 5:49-57.

- Mengel G.E., Garter W.A., Horton E.S. (1964) Geophagia with iron deficiency and hypokalemia // Arch.lntern. Med. Vol. 114. P. 470–474.

- Meryem B., Hongbing J.I., Gao Yang, Ding Huajian, Li Cai (2016) Distribution of rare earth elements in agricultural soil and human body (scalp hair and urine) near smelting and mining areas of Hezhang, China //J. of Rare Earths, Vol. 34, No. 11. P.1156-1167. [CrossRef]

- Metelsky S.T. (2009) Physiological mechanisms of absorption in the intestine // National School of Gastroenterologists, Hepatologists, 3. P. 51-56. (In Russian).

- Mincher B.J., Ball R.D., Houghton T.P. et al. (2008) Some aspects of geophagia in Wyoming bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis). European Journal of Wildlife Research, 54: 193-198.

- Minnich V., Okcuoglu A., Tarcon Y., Arcasov A., Cin S., Yorukoglu O., Renda, F., Demirag B. (1968) Pica in Turkey II. Effect of clay upon iron absorption. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 21, 78–86.

- Mure A.I. (1934) The moose of isle Royale // Misc. Publ. Mus. Zool. Univ. Mich. No 25. P. 1–44.

- Nasimovich А.А. (1938) In regard to the knowledge of the mineral nutrition of wild animals of the Caucasian Reserve // Proceedings of the Caucasus Nature Reserve. Iss. 1. Moscow. 1938. P. 103-150. (In Russian).

- Nazarov A.A., Shubnikova O.N., Kirikov, S.V. (1975) Northern taiga. In: Grouse Birds. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 31-40.

- Nchito M., Geissler P. W., Mubila L., Friis H., Olsen A. (2004) Effects of iron and multimicronutrient supplementation on geophagy: a two-by-two factorial study among Zambian schoolchildren in Lusaka // Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Vol. 98. P. 218-227.

- Ngole V.M., Ekosse G.E. (2012) Physico-chemistry, mineralogy, geochemistry and nutrient bioaccessibility of geophagic soils from Eastern Cape, South Africa // Scientific Research and Essays Vol. 7(12), pp. 1319-1331. [CrossRef]

- Palasz P.C. (2000) Toxicological and cytophysiological aspects of lanthanides action // Acta Biochimica Polonica, Vol. 47 No. 4. P. 1107-1114.

- Panichev A.M. (1987) Natural mineral ion exchangers - regulators of ionic equilibrium in the body of lithophagous animals // Dokl. of the USSR Academy of Sciences. Vol. 292. No 4. P. 1016-1019. (In Russian).

- Panichev A.M. (1990). Geophagia in the worlds of animals and humans. 223 p. Moscow: Nauka (In Russian).

- Panichev A. M. (2011). Lithophagy (geological, ecological and biomedical aspects). Moscow: Nauka. 149 p. (in Russian).

- Panichev A.M., Golokhvast K.S., Gulkov A.N., Сhekryzhov I.Yu. (2013) Geophagy and geology of mineral licks (kudurs): a review of Russian publications // Environmental Geochemistry and Health. № 1. Р.133-152.

- Panichev A.M. (2015) Rare Earth Elements: Review of Medical and Biological Properties and Their Abundance in the Rock Materials and Mineralized Spring Waters in the Context of Animal and Human Geophagia Reasons Evaluation // Achievements in the Life Sciences 9. P. 95-103. [CrossRef]

- Panichev A.M. (2016) Lithophagy: causes of the phenomenon // Priroda. No. 4. P. 25-35. (In Russian).

- Panichev A.M., Popov V.K., Chekryzhov I.Yu et al. (2016) Rare earth elements upon assessment of reasons of the geophagy in Sikhote-Alin region (Russian Federation), Africa and other world regions // Environ Geochem Health. 38. P.1255–1270. [CrossRef]

- Panichev A.M., Baranovskaya N.V., Seryodkin I.V., et al. (2021) Landscape REE anomalies and the cause of geophagy in wild animals at kudurs (mineral salt licks) in the Sikhote-Alin // Environmental Geochemistry and Health. [CrossRef]

- Panichev, A.M., Seryodkin, I.V. (2022) The mineral composition of gastroliths in the stomachs of Anatidae in Primorsky Region and the importance of silicon minerals in the physiology of birds. Amurian Zoological Journal, vol. XIV, no. 3, pp. 469–491. [CrossRef]

- Panichev A.M., Baranovskaya N.V., Seryodkin I. et al. (2023a) Excess of REE in plant foods as a cause of geophagy in animals in the Teletskoye Lake basin, Altai Republic, Russia // World Academy of Sciences Journal, № 5 V. 6. Р.1-22.

- Panichev A.M., Baranovskaya N.V., Seryodkin I.V et al. (2023b) The Main Cause of Geophagy According to Extensive Studies on Olkhon Island, Lake Baikal // Geosciences, 13, 211. [CrossRef]

- Panichev A.M., Baranovskaya N.V., Chekrizhov I.Yu., Ivanov V.V., Tsatska A.N. (2024) An Unusual Variety of Geophagy: Coal Consumption by Snow Sheep in the Transbaikalia Mountains // Doklady Earth Sciences,. [CrossRef]

- Plummer I.H., Johnson C.J., Chesney A.R., et al. (2018) Mineral licks as environmental reservoirs of chronic wasting disease prions PLoS One. May 2;13(5):e0196745. eCollection 2018. [CrossRef]

- Powell T.U., Brightsmith D. (2009) Parrots Take it with a Grain of Salt: Available Sodium Content May Drive Collpa (Clay Lick) Selection in Southeastern Peru // Biotropica V.41(3):279-282. [CrossRef]

- Powis D.A., Clark C.L., O’Brien K.J. (1994) Lanthanum can be transported by the sodium-calcium exchange pathway and directly triggers catecholamine release from bovine chromaffin cells. Cell Calcium, 16(5):377-390.

- Ramachandran K.K., Balagopalan M., Vijayakumaran Nayr P. (1995). Use pattern and chemical characterization of the natural salt licks in Chinnar wildlife sanctuary (Research report 94). Kerala Forest Research Institute Peechi, Thrissur, 18 p.

- Rambeck W.A., He M.L., Wehr U. (2004) Influence of the alternative growth promoter "Rare Earth Elements" on meat quality in pigs. In Proceedings of the British Society of Animal Science pig and poultry meat quality - genetic and non-genetic factors, 14-15. October 2004, Krakow, Poland 2004.

- Redling K. (2006). Rare earth elements in agriculture with emphasis on animal husbandry. Dissertation. Munich: University of Munich. https://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/5936/1/Redling_Kerstin.pdf.

- Reichardt F. (2008) Ingestion spontanée d’argiles chez le rat: Rôle dans la physiologie intestinale/ Thèse de doctorat. Université Louis Pasteur – Strasbourg. 222 p. https://theses.fr/2008STR13206.

- Reid R.M. (1992) Cultural and medical perspectives on geophagia // Med. Anthropol. Vol. 13. No 4. P. 337–351.

- Robertson R.H.S. 1996.Sadavers, cholera and clays//Mineralogical Society Bulletin,No.113.Р. 3-7.

- Robinson B.A., Tolan P.W. (1990) Golding-Beecher О. Childhood pica: some aspects of the clinical profile in Manchester, Jamaica // W. lnd. Med. J. Vol. 39. P. 20-26.

- Ross T. (1895) Personal narrative of travels to the equinoctial regiom of America during the years 1799–1804 by Alexander von Humholdt and Aime Bonpland. London: Routledge, Vol. 2.

- Rowland, M.J. (2002) Geophagy: an assessment of implications for the development of Australian Indigenous plant processing technologies // Australian Aboriginal Studies, https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Geophagy%3A+an+assessment+of+implications+for+the+development+of...-a0127621929.

- Sako A., Mills A.J., Roychoudhury A.N. Rare earth and trace element geochemistry of termite mounds in central and northeastern Namibia: Mechanisms for micro-nutrient accumulation // Geoderma, 2009. Vol. 153. Is. 1-2. P. 217-230.

- Sanders T.A., Braun C.E. Minerals in gastroliths and foods consumed by band-tailed pigeons // J Wildl Manag. 2021;1–24. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, T. A., Jarvis R.L. 2000. Do band-tailed pigeons seek a calcium supplement at mineral sites? Condor 10: 855-863.

- Schuller S. Seltene Erden als Leistungsförderer beim Geflügel. Untersuchungen an Broilern und Japanischen Wachteln. Dissertation, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München, 2001.

- Seim G.L., Ahn C.I., Bodis M.S., Luwedde F., Miller D.D., Hillier S.E, Tako E.C., Glahn R.P., Young S.L. (2013) Bioavailability of iron in geophagic earths and clay minerals, and their effect on dietary iron absorption using an in vitro digestion // Food and Function, Vol. 4. Is. 8. P.1263-1270.

- Severance H.W., Holt T., Patrone N.A., Chapman L. (1988) Profound muscle weakness and hypokalemia due to clay ingestion. South // Med. J. Vol. 81. P. 272-284.

- Smith B., Chenery S.R.N., Cook J.M. et al. (1998) Geochemical and environmental factors controlling exposure to cerium and magnesium in Uganda // J. Geochem. Explor. Vol. 65. Is.1. P. 1-15.

- Spragens, K. A., Bjerre, E. R., Black, J. M. (2013). Black brant Branta bernicla nigricans grit acquisition at Humboldt Bay, California, USA. Wildfowl, no. 3, pp. 104-115.

- Staaland H., White R. G., Luick J. R., Holleman D.F. (1980) Dietary influences on sodium and potassium metabolism of reindeer. Canadian Journal of Zoology 58:1728-1734.

- Stockstad D.S., Morris M.S., Lory E.C. (1953) Chemical characteristics of natural licks used by big game animals in western Montana // Trans.N. Amer. Wildlife Conf. Vol. 18. P. 247-257.

- Struhsaker T.T., Cooney D.O., Siex K.S. (1997) Charcoal Consumption by Zanzibar Red Colobus Monkeys: Its Function and Its Ecological and Demographic Consequences //International Journal of Primatology, V.18, Р. 61–72.

- Sternberg L.Y. (1933) Gilyaks, Orochs, Golds, Negidals, Ainu. Habarovsck: Dalgiz. 740 p.

- Sullivan M.E., Miller B.M., Goebel J.C. (1984) Gastrointestinal absorption of metals (51Cr. 65 Zn, 95mTc, 109Cd, 113Sn, 147Pm and 238Pu) by rats and swine. Environmental Research, 35 (2):439- 453.

- Symes C.T., Hughes J C., Mack A.L., Marsden S.J (2006) Geophagy in birds of Crater Mountain Wildlife Management Area, Papua New Guinea// Journal of Zoology. V. 268. P. 87-96. [CrossRef]

- Szasz B., Sarkadi, Schubert A., Gardos G. (1978) Effects of lanthanum on calcium dependent phenomena in human red cells // Biochimica et Biophysica acta, 512:331-340.

- Tariq H., Sharma A., Sarkar S., Ojha L., Pal R.P., Mani V. (2020) Perspectives of rare earth elements as feed additive in livestock: A review //Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. Mar.33(3):373-381. [CrossRef]

- Temga J.P., Sababa E., Mamdem L.E., Ngo Bijeck M.L., Azinwi P.T. et al. (2021) Rare earth elements in tropical soils, Cameroon soils (Central Africa) // Geoderma Regional, V. 25 (2021) e00369. [CrossRef]

- Tobler M.W., Carrillo-Percastegui S.E., Powell G. (2009) Habitat use, activity patterns and use of mineral licks by five species of ungulate in south-eastern Peru // Journal of Tropical Ecology, V.25. P.261-270. [CrossRef]

- Triven M., (1983) Immobilized Enzymes. Moscow: Mir. 211 p. (Russian Edition translated from Triven M., 1980).

- Valiathan M.S., Kartha C.C., Eapen J.T. et al. A geochemical basis for endomyocardial fibrosis // Cardiovasc Res. 1989. Vol. 23. No 7. Р. 647–648.

- Vermeer D.E. (1984) Geophagical clays from the Benin area of Nigeria: a major source for the markets of West Africa // Nat. Geogr. Soc. Res. Rep. No 16. P. 705-711.

- .

- Vermeer D.E., Ray E., Ferrell J. (1985) Nigerian Geophagical Clay: A Traditional Antidiarrheal Pharmaceutical // Science. Vol. 227. P. 634-636.

- Voros J., Mahaney W.C., Milner M.W. (2001) Geophagy by the Bonnet Macaques (Macaca radiata) of Southern India: A Preliminary Analysis // Primates, V.42. Is.4. P. 327-344.

- Wang M.Q., Xu Z.R. (2003) Effect of Supplemental Lanthanum on the Growth Performance of Pigs // Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci. Vol. 16. No. 9. Р. 1360-1363.

- Wilson M.J. (2003) Сlay mineralogical and related characteristics of geophagic materials // Journal of Chemical Ecology, Vol. 29, No. 7, Р. 1525-1547.

- Wings, O. (2007) A review of gastrolith function with implications for fossil vertebrates and a revised classification. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 1-16.

- Xun W., Shi L., Hou G., et al. (2014) Effect of rare earth elements on feed digestibility, rumen fermentation, and purine derivatives in sheep //Italian Journal of Animal Science 2014; V.13. Р. 357-362.

- Young S.L., Wilson J., Hillier S. et al., (2010) Differences and Commonalities in Physical, Chemical and Mineralogical Properties of Zanzibari Geophagic Soils // Journal of Chemical Ecology 36(1):129-40. [CrossRef]

- Young S.L., Sherman P.W., Lucks J.B., Pelto G.H. (2011) Why on earth?: evaluating hypotheses about the physiological functions of human geophagy // The quarterly review of biology,.V.86, No. 2. Р.97-120. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/659884.

- Zhao H., Cheng Z., Cheng J., et al. (2012) Erratum to: The Toxicological Effects in Brain of Mice Following Exposure to Cerium Chloride // Biol Trace Elem Res, 148:134. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, G., Zhou, Y., Lu, H., Lu, W., Zhou, M., Wang, Y., et al. (1996) Concentration of rare Earth elements, As, and Th in human brain and brain tumors, determined by neutron activation analysis. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 53, 45–49. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Ru, Wang Li, Yonghua Li et al. (2020) Distribution Characteristics of Rare Earth Elements and Selenium in Hair of Centenarians Living in China Longevity Region // Biological Trace Element Research, V.197(3). P.15-24. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W., Xu, S., Shao, P., Zhang, H., Wu, D., Yang, W., et al. (2005) Investigation on liver function among population in high background of rare Earth area in South China. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 104, 001–008. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W., Xu, S., Shao, P., Zhang, H., Wu, D., Yang, W., et al. (1997) Bioelectrical activity of the central nervous system among populations in a rare Earth element area. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 57, 71–77. [CrossRef]

| No. | Biological effects | Implementation mechanisms |

| Main effect | ||

| 1 |

Regulation of the composition and concentration of rare earth elements (REE) in the body, primarily in the neuroimmunoendocrine system |

In REE-rich landscapes by sorption in the digestive tract of excess REE on various types of mineral, organomineral and organic sorbents (including silica gels produced in the muscular stomachs of birds from siliceous minerals) and their removal from the body. |

|

In REE-poor landscapes by delivering the necessary elements to the body as part of REE-enriched minerals, clays, and other types of sorbents. | ||

| Minor effects | ||

| 2 | Supply of Na and other chemical elements to the body | Through salts and in sorbed form in various types of natural sorbents. In a number of cases in relation to mammals, especially from the ruminant group, Na can be positioned as the main element sought in kudurits. |

| 3 | Detoxification effects | By sorption and inactivation of toxic elements and compounds. |

| 4 | Participation in enzymatic reactions, especially hydrolytic reactions | By prolonging the action of enzymes when sorbed by silica gel or other natural sorbents. |

| 5 | Mechanical effects in the digestive tract | Increased peristalsis, cleansing of the digestive tract; in muscular stomachs, some mechanical processing of food is possible |

| 6 | Antacid effect | Regulation of pH in different parts of the digestive tract through the consumption of minerals with amphoteric, acidic or alkaline properties. |

| 7 | Binds excess water in the bowel | Due to hydration of ions, molecules and absorption of water by various types of sorbents. |

| 8 | Strengthening of antioxidant protection of body cells | By enhancing the antioxidant properties of a number of enzymes with some chemical elements. |

| 9 | Immune system training | By constant influx of antigenic material into the body as part of mineral adjuvants. |

| 10 | Effect on digestive microflora | Introduction of beneficial associations of microorganisms into the digestive tract; activation of fermentative forms; binding and removal of atypical microorganisms, including fungi and actinomycetes, from the digestive tract. |

| 11 | Energy-information effects | By the appearance of stable holograms of crystalline substances in the body, as well as by other, not yet studied energy-information interactions. |

| 12 | Negative biological effects are determined by the presence of toxic mineral and organic impurities in the ingested earthy substances, their dosage and the degree of their dispersion, as well as by the presence of harmful microorganisms, protozoa, helminth eggs and various toxins. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).