Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics, Pathophysiology, and Treatments of Anxiety Disorders in the Clinic

2.1. Prevalence and Symptoms of Various Anxiety Disorders in the Clinic

2.2. Pathophysiology of Anxiety Disorders in the Clinic

2.3. Pharmacological Treatments of Anxiety Disorders in the Clinic

3. Anxiolytic Substances Used in Non-Clinical Studies: Pharmacological Treatments and Neural Mechanisms

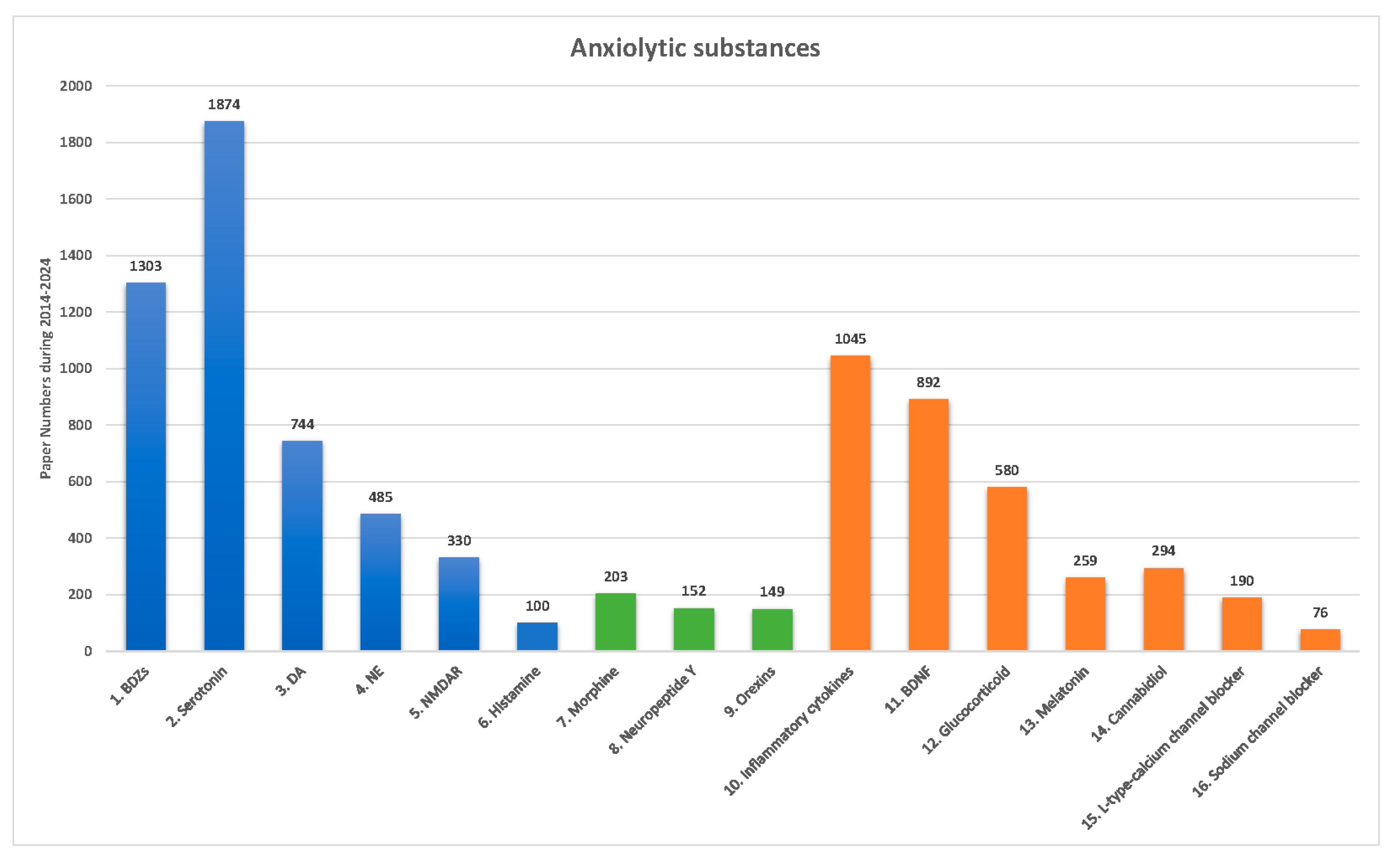

3.1. Conventional Anxiolytic Substances

3.2. Current Anxiolytic Substances: Classical Neurotransmitters, Neuropeptides, and Nonclassical Neurotransmitters

4. Types and Properties for Animal Models of Anxiety Disorders

4.1. Shaping an Animal Model of Anxiety Disorders and PTSD

4.2. Testing Anxiety and PTSD Behaviors

5. Opinion from Precinical Studies to Clinical Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Declaration of interest

Reviewer disclosures

Data availability

CRediT authorship contribution statement

References

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; Association, A.P., Ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Griebel, G.; Holmes, A. 50 years of hurdles and hope in anxiolytic drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2013, 12, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.M.; Kalueff, A.V. Anxiolytic drug discovery: what are the novel approaches and how can we improve them? Expert Opin Drug Discov 2014, 9, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J. An assessment of anxiolytic drug screening tests: hormetic dose responses predominate. Crit Rev Toxicol 2008, 38, 489–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; Sweeney, F.F. The age of anxiety: role of animal models of anxiolytic action in drug discovery. Br J Pharmacol 2011, 164, 1129–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourin, M. Animal models for screening anxiolytic-like drugs: a perspective. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015, 17, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.C.; Bergner, C.L.; Smolinsky, A.N.; Dufour, B.D.; Egan, R.J.; LaPorte, J.L.; Kalueff, A.V. Experimental Models of Anxiety for Drug Discovery and Brain Research. Methods Mol Biol 2016, 1438, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.C.; Kim, Y.K. Anxiety Disorders in the DSM-5: Changes, Controversies, and Future Directions. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1191, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabow, L.E.; Russek, S.J.; Farb, D.H. From ion currents to genomic analysis: recent advances in GABAA receptor research. Synapse 1995, 21, 189–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspesi, D.; Pinna, G. Animal models of post-traumatic stress disorder and novel treatment targets. Behav Pharmacol 2019, 30, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heesbeen, E.J.; Bijlsma, E.Y.; Verdouw, P.M.; van Lissa, C.; Hooijmans, C.; Groenink, L. The effect of SSRIs on fear learning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2023, 240, 2335–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blessing, E.M.; Steenkamp, M.M.; Manzanares, J.; Marmar, C.R. Cannabidiol as a Potential Treatment for Anxiety Disorders. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Yang, Z.; Li, C.Q. The Melatonergic System in Anxiety Disorders and the Role of Melatonin in Conditional Fear. Vitam Horm 2017, 103, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health, O. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, P.A.; Holmes, A.J.; Robinson, O.J. Threat vigilance and intrinsic amygdala connectivity. Hum Brain Mapp 2022, 43, 3283–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, O.J.; Krimsky, M.; Lieberman, L.; Allen, P.; Vytal, K.; Grillon, C. Towards a mechanistic understanding of pathological anxiety: the dorsal medial prefrontal-amygdala 'aversive amplification' circuit in unmedicated generalized and social anxiety disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vytal, K.E.; Overstreet, C.; Charney, D.R.; Robinson, O.J.; Grillon, C. Sustained anxiety increases amygdala-dorsomedial prefrontal coupling: a mechanism for maintaining an anxious state in healthy adults. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2014, 39, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.M. Defining biotypes for depression and anxiety based on large-scale circuit dysfunction: a theoretical review of the evidence and future directions for clinical translation. Depress Anxiety 2017, 34, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe, P.; Flint, A. Diagnosis and Management of Anxiety Disorders. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2018, 24, 893–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelow, B. Current and Novel Psychopharmacological Drugs for Anxiety Disorders. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1191, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, C.; Mishor, Z.; Filippini, N.; Cowen, P.J.; Taylor, M.J.; Harmer, C.J. SSRI administration reduces resting state functional connectivity in dorso-medial prefrontal cortex. Mol Psychiatry 2011, 16, 592–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrough, J.W.; Yaqubi, S.; Sayed, S.; Charney, D.S. Emerging drugs for the treatment of anxiety. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2015, 20, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscatello, M.R.; Spina, E.; Bandelow, B.; Baldwin, D.S. Clinically relevant drug interactions in anxiety disorders. Hum Psychopharmacol 2012, 27, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVeaugh-Geiss, J. Pharmacologic therapy of obsessive compulsive disorder. Adv Pharmacol 1994, 30, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, D.V. Delineation of anxiety and phobic disorders responsive to monoamine oxidase inhibitors: implications for classification. J Clin Psychiatry 1984, 45, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, H.; Pan, F.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Effects of Traumatic Stress Induced in the Juvenile Period on the Expression of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Receptor Type A Subunits in Adult Rat Brain. Neural Plast 2017, 2017, 5715816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.C.; Pollack, M.H. Benzodiazepines in clinical practice: consideration of their long-term use and alternative agents. J Clin Psychiatry 2005, 66 Suppl 2, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriksen, H.; Olivier, B.; Oosting, R.S. From non-pharmacological treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder to novel therapeutic targets. Eur J Pharmacol 2014, 732, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malikowska-Racia, N.; Salat, K.; Nowaczyk, A.; Fijalkowski, L.; Popik, P. Dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonists attenuate PTSD-like symptoms in mice exposed to single prolonged stress. Neuropharmacology 2019, 155, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitman, B.M.; Gajewski, N.D.; Mann, G.L.; Kubin, L.; Morrison, A.R.; Ross, R.J. The alpha1 adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin enhances sleep continuity in fear-conditioned Wistar-Kyoto rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2014, 49, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Daniel, M.P.; Petrunich-Rutherford, M.L. Effects of chronic prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, on anxiety-like behavior and cortisol levels in a chronic unpredictable stress model in zebrafish (Danio rerio). PeerJ 2020, 8, e8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulovic, J.; Ren, L.Y.; Gao, C. N-Methyl D-aspartate receptor subunit signaling in fear extinction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2019, 236, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, F.; Yamauchi, M.; Oyama, M.; Okuma, K.; Onozawa, K.; Nagayama, T.; Shinei, R.; Ishikawa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kakui, N. Anxiolytic-like profiles of histamine H3 receptor agonists in animal models of anxiety: a comparative study with antidepressants and benzodiazepine anxiolytic. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009, 205, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, A.; Saravia, R.; Maldonado, R.; Berrendero, F. Orexins and fear: implications for the treatment of anxiety disorders. Trends Neurosci 2015, 38, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serova, L.I.; Laukova, M.; Alaluf, L.G.; Pucillo, L.; Sabban, E.L. Intranasal neuropeptide Y reverses anxiety and depressive-like behavior impaired by single prolonged stress PTSD model. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2014, 24, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RaiseAbdullahi, P.; Vafaei, A.A.; Ghanbari, A.; Dadkhah, M.; Rashidy-Pour, A. Time-dependent protective effects of morphine against behavioral and morphological deficits in an animal model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Brain Res 2019, 364, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczytkowski-Thomson, J.L.; Lebonville, C.L.; Lysle, D.T. Morphine prevents the development of stress-enhanced fear learning. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2013, 103, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inutsuka, A.; Yamanaka, A. The physiological role of orexin/hypocretin neurons in the regulation of sleep/wakefulness and neuroendocrine functions. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrabian, S.; Riahi, E.; Karimi, S.; Razavi, Y.; Haghparast, A. The potential role of the orexin reward system in future treatments for opioid drug abuse. Brain Res 2020, 1731, 146028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felger, J.C. Imaging the Role of Inflammation in Mood and Anxiety-related Disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol 2018, 16, 533–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andero, R.; Ressler, K.J. Fear extinction and BDNF: translating animal models of PTSD to the clinic. Genes Brain Behav 2012, 11, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.B.; Liu, H.X.; Shi, W.; Ding, T.; Hu, H.Q.; Guo, H.W.; Jin, S.; Wang, X.L.; Zhang, T.; Lu, Y.C.; et al. Various BDNF administrations attenuate SPS-induced anxiety-like behaviors. Neurosci Lett 2022, 788, 136851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido, A.; Velasco, E.R.; Monari, S.; Cano, M.; Cardoner, N.; Sandi, C.; Andero, R.; Perez-Caballero, L. Glucocorticoid-based pharmacotherapies preventing PTSD. Neuropharmacology 2023, 224, 109344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurana, K.; Bansal, N. Lacidipine attenuates caffeine-induced anxiety-like symptoms in mice: Role of calcium-induced oxido-nitrosative stress. Pharmacol Rep 2019, 71, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirza, N.R.; Bright, J.L.; Stanhope, K.J.; Wyatt, A.; Harrington, N.R. Lamotrigine has an anxiolytic-like profile in the rat conditioned emotional response test of anxiety: a potential role for sodium channels? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005, 180, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragen, B.J.; Seidel, J.; Chollak, C.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Neumeister, A. Investigational drugs under development for the treatment of PTSD. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2015, 24, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, S.B.; Singewald, N. Novel pharmacological targets in drug development for the treatment of anxiety and anxiety-related disorders. Pharmacol Ther 2019, 204, 107402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiller, J.W. Depression and anxiety. Med J Aust 2013, 199, S28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, E.; Fliugge, G. Experimental animal models for the simulation of depression and anxiety. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2006, 8, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiess, K.O. Statistical concepts for the behavioral sciences; Allyn and Bacon, Inc., 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Flandreau, E.I.; Toth, M. Animal Models of PTSD: A Critical Review. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2018, 38, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissek, S.; Kaczkurkin, A.N.; Rabin, S.; Geraci, M.; Pine, D.S.; Grillon, C. Generalized anxiety disorder is associated with overgeneralization of classically conditioned fear. Biol Psychiatry 2014, 75, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.H.; Lim, Y.S.; Ou, C.Y.; Chang, K.C.; Tsai, A.C.; Chang, F.C.; Huang, A.C.W. The Medial Prefrontal Cortex, Nucleus Accumbens, Basolateral Amygdala, and Hippocampus Regulate the Amelioration of Environmental Enrichment and Cue in Fear Behavior in the Animal Model of PTSD. Behav Neurol 2022, 2022, 7331714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Morinobu, S.; Takei, S.; Fuchikami, M.; Matsuki, A.; Yamawaki, S.; Liberzon, I. Single prolonged stress: toward an animal model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety 2009, 26, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, B.N.; Fleshner, M. Exercise, learned helplessness, and the stress-resistant brain. Neuromolecular Med 2008, 10, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, S.F.; Watkins, L.R. Stressor controllability and learned helplessness: the roles of the dorsal raphe nucleus, serotonin, and corticotropin-releasing factor. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2005, 29, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banagozar Mohammadi, A.; Torbati, M.; Farajdokht, F.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Fazljou, S.M.B.; Vatandoust, S.M.; Golzari, S.E.J.; Mahmoudi, J. Sericin alleviates restraint stress induced depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors via modulation of oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and apoptosis in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. Brain Res 2019, 1715, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, N.C.; Kubala, K.H.; Hassell, J.E., Jr.; Lieb, M.W.; Nguyen, K.T.; Heinze, J.D.; Drugan, R.C.; Maier, S.F.; Lowry, C.A. Two models of inescapable stress increase tph2 mRNA expression in the anxiety-related dorsomedial part of the dorsal raphe nucleus. Neurobiol Stress 2018, 8, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Rhee, J.; Park, K.; Han, J.S.; Malinow, R.; Chung, C. Exposure to Stressors Facilitates Long-Term Synaptic Potentiation in the Lateral Habenula. J Neurosci 2017, 37, 6021–6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, X.Z.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Yu, T.; Dohl, J.; Ursano, R.J. Updates in PTSD Animal Models Characterization. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 2011, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.C.; Fogaca, M.V.; Aguiar, D.C.; Guimaraes, F.S. Animal models of anxiety disorders and stress. Braz J Psychiatry 2013, 35 Suppl 2, S101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, T.; Duffy, L.; Herzog, H. Behavioural profile of a new mouse model for NPY deficiency. Eur J Neurosci 2008, 28, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraeuter, A.K.; Guest, P.C.; Sarnyai, Z. The Open Field Test for Measuring Locomotor Activity and Anxiety-Like Behavior. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1916, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critchley, M.A.; Handley, S.L. Effects in the X-maze anxiety model of agents acting at 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1987, 93, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handley, S.L.; McBlane, J.W. An assessment of the elevated X-maze for studying anxiety and anxiety-modulating drugs. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 1993, 29, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedia, S.; Chattarji, S. Marble burying as a test of the delayed anxiogenic effects of acute immobilisation stress in mice. J Neurosci Methods 2014, 233, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Augustsson, H.; Markham, C.M.; Hubbard, D.T.; Webster, D.; Wall, P.M.; Blanchard, R.J.; Blanchard, D.C. The rat exposure test: a model of mouse defensive behaviors. Physiol Behav 2004, 81, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalueff, A.V.; Tuohimaa, P. The Suok ("ropewalking") murine test of anxiety. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc 2005, 14, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliethermes, C.L.; Crabbe, J.C. Pharmacological and genetic influences on hole-board behaviors in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2006, 85, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, S.B.; Geyer, M.A.; Gallagher, D.; Paulus, M.P. The balance between approach and avoidance behaviors in a novel object exploration paradigm in mice. Behav Brain Res 2004, 152, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anxiety disorders | Prevalence | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) | 0.9% and 2.9% prevalence rates for adolescents and adults in the United States. | 1. Persistent and excessive anxiety 2. Worry about school and work performance |

| 2. Panic disorder | Appropriately 2–3% for adolescents and adults in the United States. | 1. Recurrent unexpected panic attacks. 2. Persistently concerned or worried about further panic attacks. |

| 3. Agoraphobia | Approximately 1.7% for adolescents and adults in the Unites States. | 1. Significant and intense fear or anxiety induced by an extendable range of surroundings in real or anticipated exposure. |

| 4. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | 3.5% for adults in the United States. | 1. Concern intrusions and avoidance of memories associated with the traumatic event itself. 2. The critical features of PTSD vary. 3. Some patients encounter fear-based reexperiencing, emotional, and behavioral symptoms. 4. Others feel anhedonic or dysphoric mood states, and negative cognitions may be most distressing. 5. In some cases, arousal and reactive-externalizing symptoms are prominent 6. Others produce dissociative symptoms predominate. 7. Some individuals exhibit combinations of these symptom patterns. |

| 5. Social anxiety disorder (SAD; Social phobia) | Approximately 7% in the United States. | 1. Social phobia. 2. Fearful or anxious about or avoidant of social interactions and social surroundings that involve the possibility of being scrutinized. |

| 6. Acute stress disorder (ASD) | Less than 20% (do not involve interpersonal assault) in the United States. | 1. Symptoms may vary by individuals. 2. Anxiety response for reexperiencing or reactivity to the traumatic event. 3. A dissociative or detached presentation, although these individuals typically will also display strong emotional or physiological reactivity in response to trauma reminders. 4. A strong anger response in which reactivity is characterized by irritable or possibly aggressive responses. 5. The symptoms are development at least lasting from 3 days to 1 month. |

| 7. Separation anxiety disorder | About 0.9–1.9% for adults, 4% for children, and 1.6% for adolescents in the United States. | 1. Excessive fear or anxiety concerning separation from home or attachment figures. |

| 8. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) | About 1.2% in the United States. | 1. The presence of obsessions and compulsions. 2. Obsessions are repeated, persistent thoughts, images, or urges. 3. Persistent thoughts are voluntary associated with marked distress or anxiety. 4. Compulsions are repetitive behaviors or mental acts. |

| Anxiety disorders and treatments | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicines | Drugs | 1. GAD | 2. PD | 3. Agoraphobia | 4. PTSD | 5. SAD | 6. ASD | 7. Separation anxiety disorder | 8. OCD |

| 1. BDZs | Alprazolam Chlordiazepoxide Clonazepam Diazepam Lorazepam Oxazepam |

V V V V V |

V V V V V V |

V V V V V |

V V V V V |

V V V V V |

V V V V V |

V V V V V |

V V V V V |

| 2. SSRIs | Escitalopam Fluoxetine Fluvoxamine Paroxetine Citalopram Sertaline |

V V V |

V V V V V V |

V V V V V V |

V V |

V V V V V |

|

|

V V V V |

| 3. SNRIs | Duloxetine Venlafaxine |

V V |

V |

V |

V |

||||

| 4. TCA | Clomipramine Doxepine Imipramine |

V |

V V V |

V V |

V |

V |

V |

V |

V V |

| 5. MAOIs | Phenelzine Moclobemide |

V |

V |

||||||

| 6. Calcium modulators | Pregabalin | V |

V |

||||||

| 7. Azapirone | Buspirone | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| 8. Antihistamine | Hydroxyzine | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| Mechanism of action | Mental illness | Animal models | Neural mechanisms and effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical neurotransmitters: | ||||

| 1. Agonism of GABAa receptor | Anxiety disorders and PTSD | Conditioned fear learning | 1. BDZ drugs affiliate GABAa receptor 2. Cause anxiolytic effects |

Stevens et al. (2005); Lu et al. (2017) |

| 2. Inhibition of serotonin reuptake | Anxiety-related disorders (e.g., panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorders, PTSD) | Conditioned fear learning (contextual or cue) or PTSD animal models | 1. SSRIs drugs act the inhibition of serotonin reuptake 2. Lead to anxiolytic effects |

Hendriksen et al. (2014); Heesbeen et al. (2023) |

| 3. Agonism of dopamine receptor | PTSD | PTSD animal model (single prolonged stress) | 1. D2/D3 receptor agonism 2. Lead to anxiolytic effects |

Malikowska-Racia et al. (2019) |

| 4. Antagonism of norepinephrine receptor | PTSD | Conditioned fear learning | 1. Antagonism of alpha-1 adrenergic receptor 2. Disrupt anxiety- and PTSD-associated symptoms |

Laitman et al. (2014); O’Daniel et al. (2020) |

| 5. Antagonism of NMDA receptor | Anxiety disorders and PTSD | Conditioned fear learning animal model | 1. Antagonism of NMDA receptor 2. Attenuate fear symptoms |

Radulovic et al. (2018) |

| 6. Agonism of histamine receptor | Anxiety disorders | Isolation-induced aggressive behavior; Conditioned fear learning | 1. H3 receptor agonism 2. Reduce anxiety disorders |

Yokoyama et al. (2009) |

| Neuropeptides: | ||||

| 1. Agonism of opiates | PTSD | Conditioned fear learning | 1. Opioid receptor agonism 2. Result in anxiolytic effects |

Szczytkowski-Thomson et al. (2013); RaiseAbdullahi et al. (2019) |

| 2. Activation of neuropeptide Y | PTSD | PTSD animal model (single prolonged stress) | 1. Neuropeptide Y receptor agonism 2. Reduce anxiety behaviors and PTSD symptoms |

Serova et al. (2014) |

| 3. Antagonism of orexins receptor | Anxiety disorders (e.g., phobia, panic, and PTSD) | Conditioned fear learning animal models | 1. Orexins receptor antagonism 2. Impair fear behaviors |

Flores et al. (2015) |

| Nonclassical neurotransmitters: | ||||

| 1. Activation of inflammatory cytokines | Anxiety disorders and PTSD | Multiple anxiety and PTSD animal models | 1. Activation of inflammation cytokines 2. Cause anxiety disorders and PTSD symptoms. |

Felger (2018) |

| 2. Activation of BDNF | Anxiety disorders and PTSD | PTSD animal model (single prolonged stress) | 1. Activation of BDNF via TrkB receptor 2. Attenuate anxiety disorders |

Yin et al. (2022); Andero and Ressler (2012) |

| 3. Activation of glucocorticoid | PTSD | PTSD animal models | 1. Activation of glucocorticoid receptor 2. Block anxiety disorders |

Florido et al. (2023) |

| 4. Activation of Melatonin | PTSD | Conditioned fear learning animal models | 1. Activation of melatonin receptor 2. Impairs contextual fear conditioning |

Huang et al. (2017) |

| 5. Activation of cannabidiol | Anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, PTSD) | Multiple anxiety disorders animal models | 1. Agonism of CB1 receptor 2. Impair multiple anxiety disorders (including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and PTSD) |

Blessing et al. (2015) |

| 6. Action of L-type calcium channel blocker | Anxiety disorders | Caffeine-induced anxiety symptoms | 1. Antagonism of calcium channels 2. Cause anxiolytic effects |

Khurana et al. (2019) |

| 7. Activation of sodium channel blocker | PTSD | Conditioned fear learning (i.e., cue) | 1. Antagonism of sodium channels 2. Lead to anxiolytic effects |

Mirza et al. (2005) |

| Animal models | Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages | When to use | Use frequency | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Shaping anxiety models | ||||||

|

1. Fear conditioning: Cue/footshock |

Applying a discrete cue stimulus to pair with footshock-induced stress. | Cue is a clear-cut stimulus; high face, predictive, and constructive validity. | --- | Anxiety disorders; PTSD | *** | Lissek et al. (2013) |

|

2. Fear conditioning: Context/footshock |

Applying a contextual stimulus to pair with footshock-induced stress. | A contextual stimulus mimics the environment; high face, predictive, and constructive validity. | Context is a complex stimulus combining various environmental stimuli. | Anxiety disorders; PTSD | *** | Yu et al. (2022) |

| 3. Single prolonged stress | Animals are restrained for 2 hours and then forced to swim test for 20 minutes. Following recovery for 15 minutes, animals are exposed to ether until they lose consciousness. | Stable stress; face, predictive, and constructive validity. | Require complex and long-term stress manipulations. Single prolonged stress model is complex compared to the fear conditioning model. | PTSD | *** | Yamamoto et al. (2009) |

| 4. Learned helplessness | Animals are exposed to uncontrolled stressors through behavioral responses. | Manipulate footshock to shape stressor; thus, effective and easy manipulation. | Also used to test depression behaviors. | PTSD; MDD | * | Greenwood and Fleshner (2008); Maiet and Watkins (2005). |

| 5. Restraint stress | Mice are immobilized by placing them into well-ventilated 50 mL Falcon tubes for 2 hours per day over 21 consecutive days. | Restraint mice for immobility to induce stressor; easy preparation and manipulation. | Also used to test depression behaviors. | Anxiety disorders; PTSD | * | Mohammadi et al. (2019) |

| 6. Inescapable tail shock | Animals experience uncontrolled and inescapable tail shock, leading to acute stress. | Easy manipulation for Inescapable tail shock to induce stress. | Also used to test depression behaviors. | PTSD | * | Donner et al. (2018); Park et al. (2017) |

| 7. Underwater trauma | Animals are held underwater for 30 seconds. | Easy manipulation for holding animals underwater to induce stress. | Doubt in the face, predictive, and constructive validity. | PTSD | * | Zhang et al. (2019) |

| 8. Social isolation | Animals are raised without any companion or environmental enrichment. | Easy manipulation for animals without any companion. | Long-term conduction. | PTSD | ** | Aspesi and Pinna (2019) |

| 9. Social defeat | Animals are exposed to a trained aggressor conspecific for 6 hours daily for 5 or 10 days. | Easy manipulation for exposing aggressors inducing stress. | --- | PTSD | ** | Campos et al. (2013) |

| 10. Early-life stress | Maternal separation induces trauma events. | Face, predictive, and constructive validity. | Long-term conduction. | PTSD | ** | Schoner et al. (2017); Zhang et al. (2019) |

| 11. Predator-based stress | Predators or predator-related stimuli (such as predator’s urine) produce trauma induction. | Place predator and its related stimuli to induce stress; Easy manipulation. | --- | PTSD | ** | Zhang et al. (2019) |

| B. Testing anxiety behaviors | ||||||

| 1. Open field test | Tests time spent or crossing trials in the center area of the open field task for anxiety responses. | Face, predictive, and constructive validity. | Competition between locomotion and anxiety behavior. | Multiple anxiety disorders; PTSD | *** | Karl et al. (2008); Kraeuter et al. (2019) |

| 2. Elevated zero maze test | Test is conducted in the open arm to indicate the strength of the anxiety responses. | No crossing areas, which enforces animals’ decisions. | Conflicts arise from spending time in open arms and closed arms. | Multiple anxiety disorders; PTSD | ** | Campos et al. (2013) |

| 3. Elevated plus maze test | Test is conducted in the open arm to indicate the strength of the anxiety responses. | Cross the area to take a rest. | Long-term staying in the cross area between the closed and open arms | Multiple anxiety disorders; PTSD | *** | Karl et al. (2008) |

| 4. Elevated x-maze test | Tests the open arm time/total time ratio. | Face, predictive, and constructive validity. | --- | Multiple anxiety disorders | * | Critchley and Handley (1987); Handley and McBlane (1993) |

| 5. Light-dark box test | Tests activity and time spent in both brightly lit and dark apparatus compartments using the animal’s innate desire to explore novel areas. | Assessing the activity and time in light and dark box; Easy manipulation. | --- | Multiple anxiety disorders | ** | Karl et al. (2008) |

| 6. Startle response test | Pairing a conditioned stimulus (sound or light) with a footshock induces an anxiogenic “startle” response. | Face, predictive, and constructive validity for anxiety disorders. | Limitations in the style of anxiety behaviors for a cue with footshock. | Multiple anxiety disorders; PTSD | ** | Hart et al. (2016) |

| 7. Marble burying test | Animals with previous stress are placed in the test cage and then test amounts of marble burying up to 2/3 of the depth with bedding. | Face, predictive, and constructive validity for anxiety disorders. | A digging activity for a species-typical reaction to stress (e.g., rats and mice). | Multiple anxiety disorders; PTSD | ** | Archer et al. (1987); Kedia and Chattarji (2014) |

| 8. Defensive shock-prod burying test | A familiar test cage or home cage with plentiful bedding and a hole in the wall 2 cm above the bedding. An electrical probe is connected to a shock source. Measuring the depth to which the prod is buried. | Face, predictive, and constructive validity. | Animals do not touch the electrical probe and cannot induce anxiety. | Multiple anxiety disorders | ** | Yang et al. (2004) |

| 9. Grooming test | Stressors (e.g., novel environment, predator exposure, bright light) induce grooming. |

Test grooming behavior; simple manipulation. | Questionable face, predictive, and constructive validity. | Multiple anxiety disorders; PTSD | * | Hart et al. (2016) |

| 10. Social interaction test | Two mice were in the test environment for 5 or 10 minutes and recorded the duration and frequency of all social interactions, including sniffing, following, chasing, touching, and biting. Higher scores in social interactions indicate lower anxiety behaviors. | More accessible design and manipulation. | Limitations in social anxiety disorders. | Multiple anxiety disorders; PTSD | ** | Hart et al. (2016) |

| 11. Suok test | The Suok task simultaneously tests anxiety vestibular and neuromuscular deficits by combining an unstable rod with novelty. The threats of height, loss of balance, and novelty are presented to analyze anxiety and assess animal exploration. |

Face validity. | Doubt in predictive and constructive validity. Competitions in testing for multiple behaviors. | Multiple anxiety disorders; PTSD | * | Kalueff and Tuohimaa (2005) |

| 12. Stress-induced hyperthermia test | Based on the evolutionarily important role of hyperthermia, whereby body temperature rises upon encountering stressful stimuli. | Across many species, including humans. | Testing errors from a lot of confounding factors. | Multiple anxiety disorders; PTSD | * | Hart et al. (2016) |

| 13. Hole-board test | Tests head dipping behaviors. More head dips indicate more explorations and lower anxiety. | Assessing animals’ head dipping behavior; Easy preparation and manipulation. |

Doubt in the face, predictive, and constructive validity. |

Multiple anxiety disorders | * | Kliethermes and Crabbe (2006) |

| 14. Rat exposure test | Uses animals' natural defensive “avoidance” behavioral response to signs of potential danger, such as a natural predator. Defensive behaviors include stretch-attend posture, stretch approach, freezing, burying, and hiding. | Testing the nature defensive behavior; thus, easy to use and manipulate. | Variations during different species. | Multiple anxiety disorders | * | Hart et al. (2016) |

| 15. Novel object test | Testing the approach-avoidance behaviors of mice in response to novel stimuli. Longer time in exploration for a novel object, indicating lower anxiety behaviors. | Face, predictive, and constructive validity. | Confused with recognition tests using the same task. | Multiple anxiety disorders; PTSD | * | Powell et al. (2004) |

| Animal models of anxiety disorders | Clinical anxiolytic drugs | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety disorders |

1. Fear conditioning (Cue) |

2. Fear conditioning (Context) |

3. SPS | 4. Learned helpless ness | 5. Restraint stress | 6. Inescapable tail shock | 7. Underwater trauma | 8. Social isolation | 9. Social defeat | 10. Early-life stress | 11. Predator-based stress | Medicines | |

| 1. GAD | V | V | BDZs; SSRIs; SNRIs; TCA; Calcium modulators; Azapirone; Antihistamine | ||||||||||

| 2. PD | V | V | V | BDZs; SSRIs; SNRIs; TCA; MAOIs; Azapirone; Antihistamine | |||||||||

| 3. Agoraphobia | V | BDZs; SSRIs; SNRIs; TCA; Azapirone; Antihistamine | |||||||||||

| 4. PTSD | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | BDZs; SSRIs; SNRIs; TCA; Azapirone; Antihistamine | |

| 5. SAD | V | V | BDZs; SSRIs; SNRIs; TCA; MAOIs; Calcium modulators; Azapirone; Antihistamine | ||||||||||

| 6. ASD | V | V | V | V | V | BDZs; TCA; Azapirone; Antihistamine | |||||||

| 7. Separation anxiety disorder | V | V | BDZs; TCA; Azapirone; Antihistamine | ||||||||||

| 8. OCD | V | V | V | V | BDZs; SSRIs; TCA; Azapirone; Antihistamine | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).