1. Introduction

Ebola virus (EBOV) has caused multiple outbreaks of EBOV disease (EVD) since the late 20

th century [

1]. With high case fatality rates and few approved therapeutic options, EVD continues to pose a significant threat to global health and has been classified as a priority disease by the World Health Organization (WHO) [

2,

3]. Due to its extreme virulence, infectious EBOV is required be handled in biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) laboratories, significantly limiting the breadth of molecular research into EBOV biology and pathogenesis.

EBOV has a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome which encodes seven structural genes [

4]. The genome is encapsidated in a nucleocapsid and enclosed within a host-derived, lipid-bilayer membrane enveloped particle. Life cycle modeling systems, like minigenomes, are powerful tools for studying the molecular biology of EBOV without the extreme safety concerns associated with handling infectious virus (reviewed in [

5]). Minigenomes are truncated, defective viral genomes lacking several or all viral open reading frame (ORF) sequences, which are replaced by reporter genes to monitor their activity in cells. Importantly, minigenomes retain non-coding regions containing the minimal promoter recognized by the viral polymerase as well as the genome packaging signals. This allows minigenomes to undergo replication and transcription when viral ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex proteins, including nucleoprotein (NP), transcriptional activator VP30, polymerase cofactor VP35, and RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase (L), are provided

in trans [

6]. Additionally, by supplying additional viral structural proteins, such as matrix protein VP40, surface glycoprotein (GP), and VP24, the minigenome systems can be expanded to the production of transcription- and replication-competent virus-like particles (trVLPs) [

7,

8]. trVLPs are morphologically similar to EBOV particles and have been used for studying EBOV biology as well as evaluation as a vaccine candidate [

8,

9,

10,

11].

There are well-established animal models for EVD in non-human primates, pigs, ferrets, hamsters, guinea pigs, and mice (reviewed in [

12]). While mice can be used, it is worth noting that EBOV does not cause significant diseases in most naïve mice. However, EBOV can be adapted to infect mice through serial passaging in progressively older suckling mice [

13,

14,

15]. After this selection, mouse-adapted Ebola virus (MA-EBOV) has been shown to recapitulate key hallmarks of human EVD, including high viremia, extensive pro-inflammatory cytokine activation [

13,

16], and lymphocyte apoptosis [

17,

18,

19,

20].

When the sequence of MA-EBOV was examined, 13 nucleotide changes were acquired. Five of these mutations did not change amino acid codons, but the eight others mutated amino acids [

13,

14,

15]. When the single amino acid changes were examined in mice, only single mutations in NP and VP24 were critical for virulence in mice, but only when they were both present in the virus [

21]. These mutations have been linked to overcoming host type I interferon (IFN) response and to enhancing viral replication in mouse macrophages [

21]. However, the detailed roles of these mutations still remain unclear.

In this study, we established a pentacistronic EBOV minigenome (5xMG) by introducing the NP gene, expanding on the previously established minigenome systems already containing VP24, VP40, GP, and a reporter gene. To evaluate the effects of mutations found in MA-EBOV, we introduced the mutations into the NP and VP24 genes within the 5xMG. trVLPs produced by this system were utilized to infect murine macrophages, a critical cell type for in vivo EBOV infection. Transcriptomic analysis revealed extensive changes in response to trVLP infection, including distinct immune activation profiles between WT- and MA-trVLP infections. We propose the 5xMG as a new tool for assessment of EBOV biology under BSL-2 conditions.

2. Results

2.1. Development of an NP Gene-Containing Pentacistronic EBOV Minigenome

A previously described tetracistronic minigenome (4xMG) expresses VP40, GP, VP24 and a luciferase reporter gene [

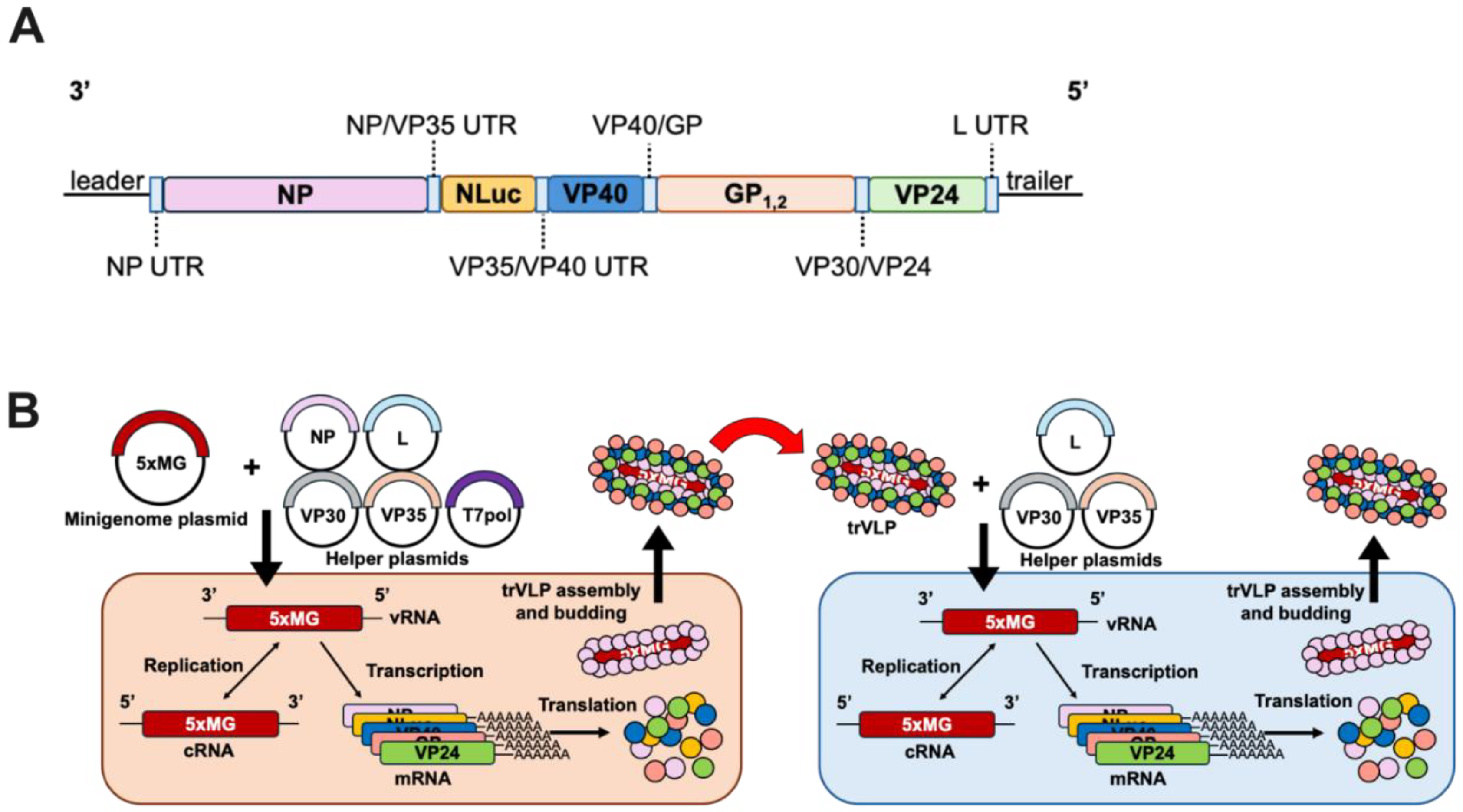

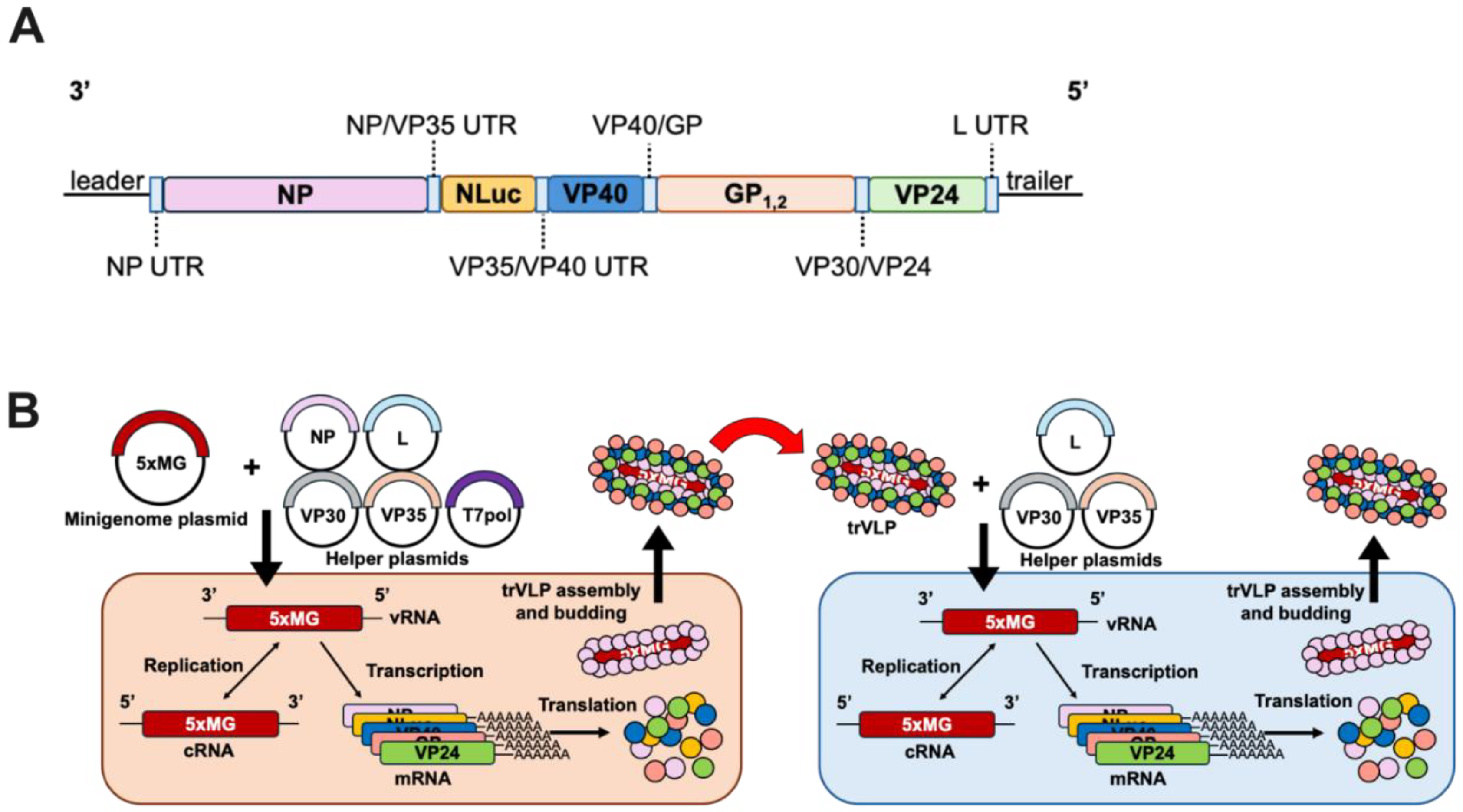

7]. With the intent to model MA-EBOV, we expanded the system to a 5xMG system by incorporating the EBOV NP gene between the NP untranslated region (UTR) and VP35 transcription start signal, its “native” position in the EBOV viral genome (

Supplementary Figure 1). This construct, flanked by a hammerhead ribozyme and hepatitis delta virus ribozyme sequences, was inserted in the anti-sense orientation into an expression plasmid under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. The resulting 5xMG contains the viral genes NP, VP40, GP, and VP24, along with a NanoLuc luciferase reporter gene (

Figure 1A).

When 5xMG is co-transfected in P0 cells with NP, VP30, VP35, and L plasmids, its genome undergoes replication and transcription, like the 4xMG, as well as assemble trVLPs that can infect P1 target cells (

Figure 1B). The 5xMG delivered via trVLP infection only undergoes primary transcription in naïve P1 cells. If these cells are transfected with the VP30, VP35, and L plasmids, the 5xMG genome is replicated thereby amplifying both mRNA and protein production from the minigenome. In contrast, the 4xMG does not replicate under the same conditions as its genome does not carry the NP gene. The NP protein must be externally supplied to P1 cells to have 4xMG to replicate. Therefore, the presence of the NP gene within the 5xMG genome should allow aspects of EBOV NP biology to be examined that are not feasible in the existing 4xMG system.

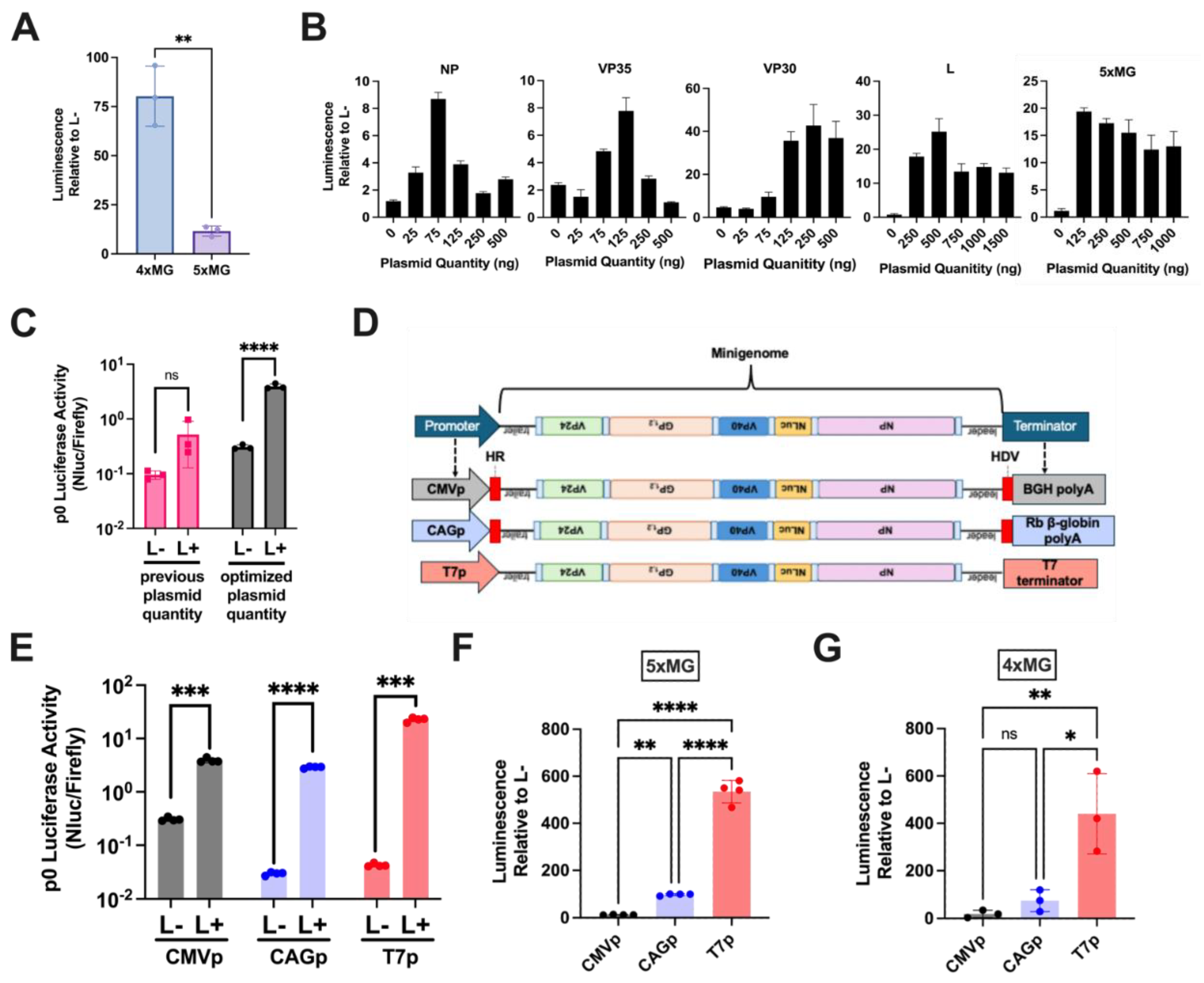

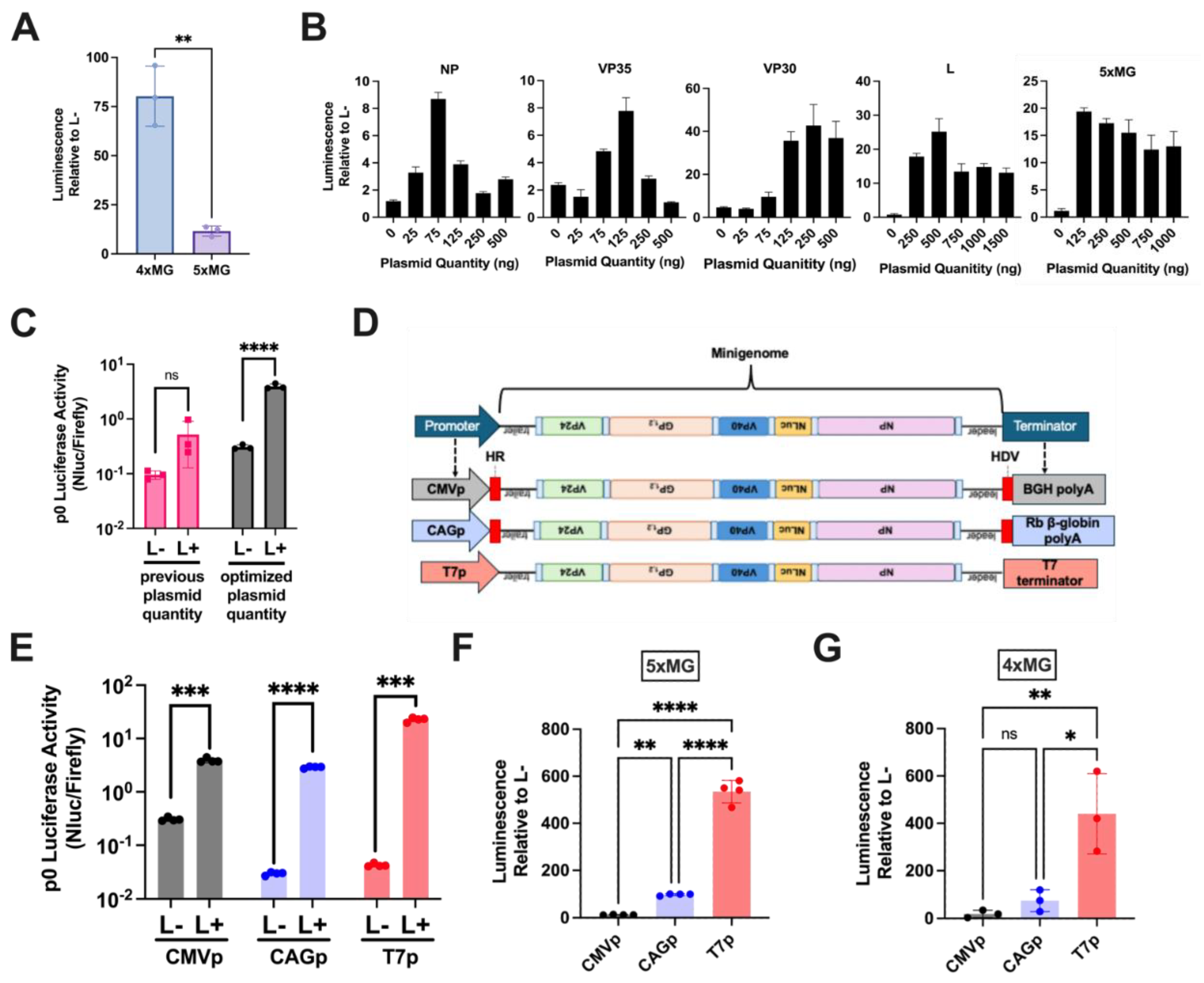

To directly compare the 5x- with 4xMG, 293T cells were transfected using previously published minigenome and helper plasmid (NP, VP35, VP30, and L) amounts and protocol [

22]. Both systems showed a significant increase in reporter signal in the presence of the L polymerase (L+) when compared to an L-absent (L-) control. However, the 5xMG construct exhibited an approximately 10-fold lower reporter activity compared to 4xMG (

Figure 2A). This aligns with previous findings that minigenome reporter activity is inversely correlated with its genome length [

7], and may also be influenced by the reporter gene’s placement as the second gene within the minigenome which will be transcribed less due to the known gradient of transcription [

23].

3.2. Plasmid Optimization and the T7 Bacteriophage Promoter Increase 5xMG Efficiency in Producer Cells

To maximize the activity of 5xMG, we individually titrated the minigenome and helper plasmids while keeping the other plasmid amounts constant during the transfection of producer cells (

Figure 2B). The initial transfection ratios were based on previously published 4xMG system [

7,

22], which used 125 ng NP, 125 ng VP35, 75 ng VP30, 1,000 ng L, and 250 ng minigenome plasmids. Starting from zero, the plasmid quantity used in transfection was gradually increased up to 500-1,500 ng, depending on the plasmid size. The optimized plasmid quantities, which produced the highest signal-to-noise ratio for the 5xMG, were: 75 ng NP, 125 ng VP35, 250 ng VP30, 500 ng L, and 125 ng minigenome plasmids. Compared to the starting conditions, the optimized values featured a reduction in the amounts of NP, L, and minigenome plasmids, and an increase in VP30 plasmid. Importantly, the unoptimized reactions did not reach a statistical significance between the L- and L+ conditions, while the optimized reactions showed both an increased reporter signal as well as a significant difference between L- and L+ (

Figure 2C). All subsequent 5xMG transfections and trVLP production utilized the optimal plasmid quantities for maximum yield.

A previous study demonstrated that the CAG promoter (CAGp), an RNA polymerase II (pol-II) promoter combining the CMV enhancer with the chicken beta-actin promoter and intron, drives stronger EBOV minigenome activity compared to the CMV promoter [

24]. Additionally, the T7 bacteriophage polymerase promoter (T7p) has also been successfully utilized in EBOV minigenome systems [

6,

7,

24,

25,

26]. To compare promoter efficiency for producing 5xMG RNA genomes, we generated two additional 5xMG constructs: one driven by CAGp and the other by T7p (

Figure 2D) and assessed their minigenome activities alongside the CMVp-driven construct. Reporter assays demonstrated that each of the constructs mediated significant increases in luciferase activity when L was provided as compared to the L- condition (

Figure 2E). CAGp was stronger than CMVp, but T7p outperformed both, showing a 400- to 500-fold increase over CAGp and CMVp (

Figure 2F). Notably, similar trends were also observed in the EBOV 4xMG system (

Figure 2G), suggesting that T7p system may be more efficient than pol II-based systems in driving multi-cistronic EBOV minigenome activity.

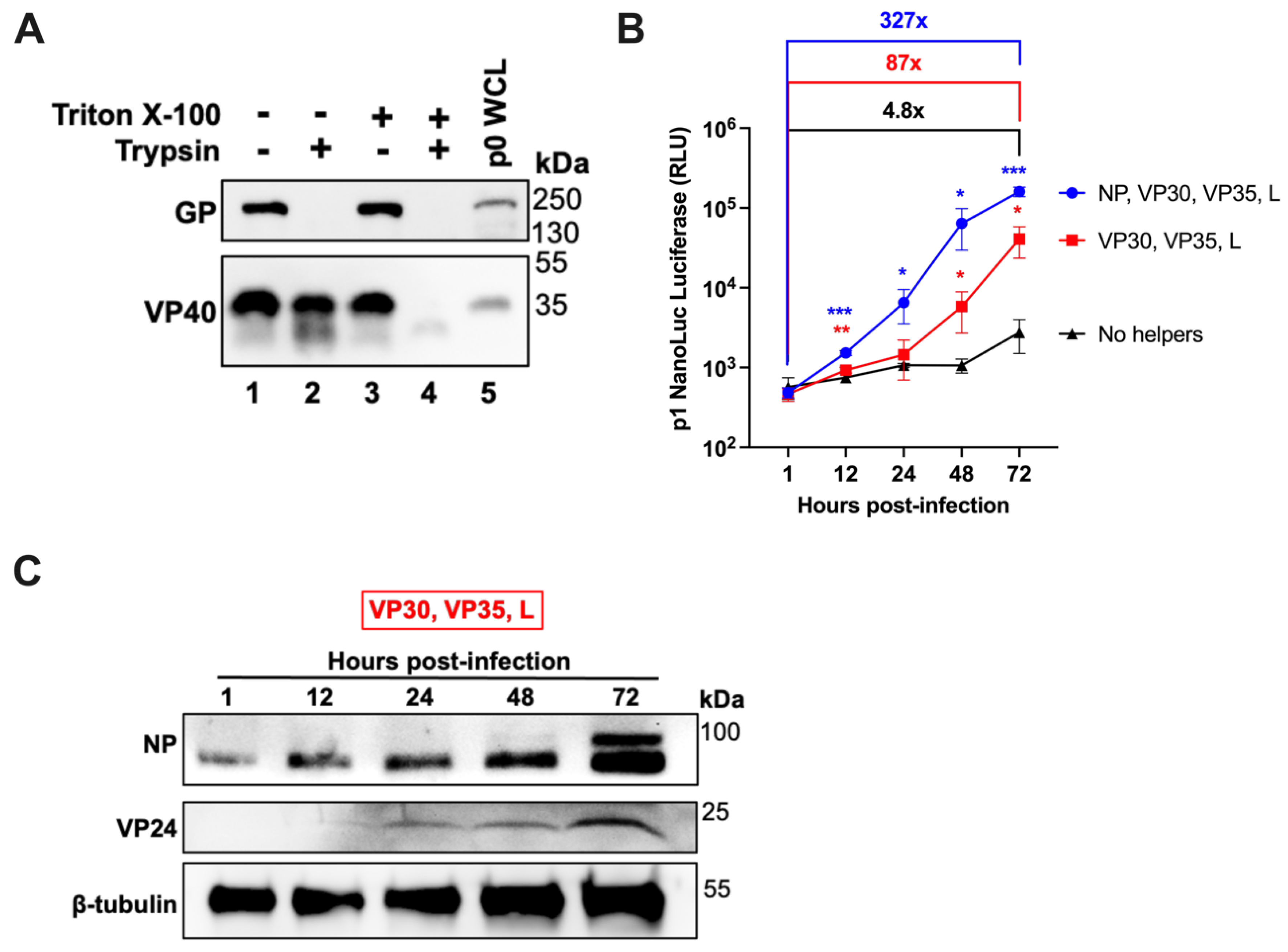

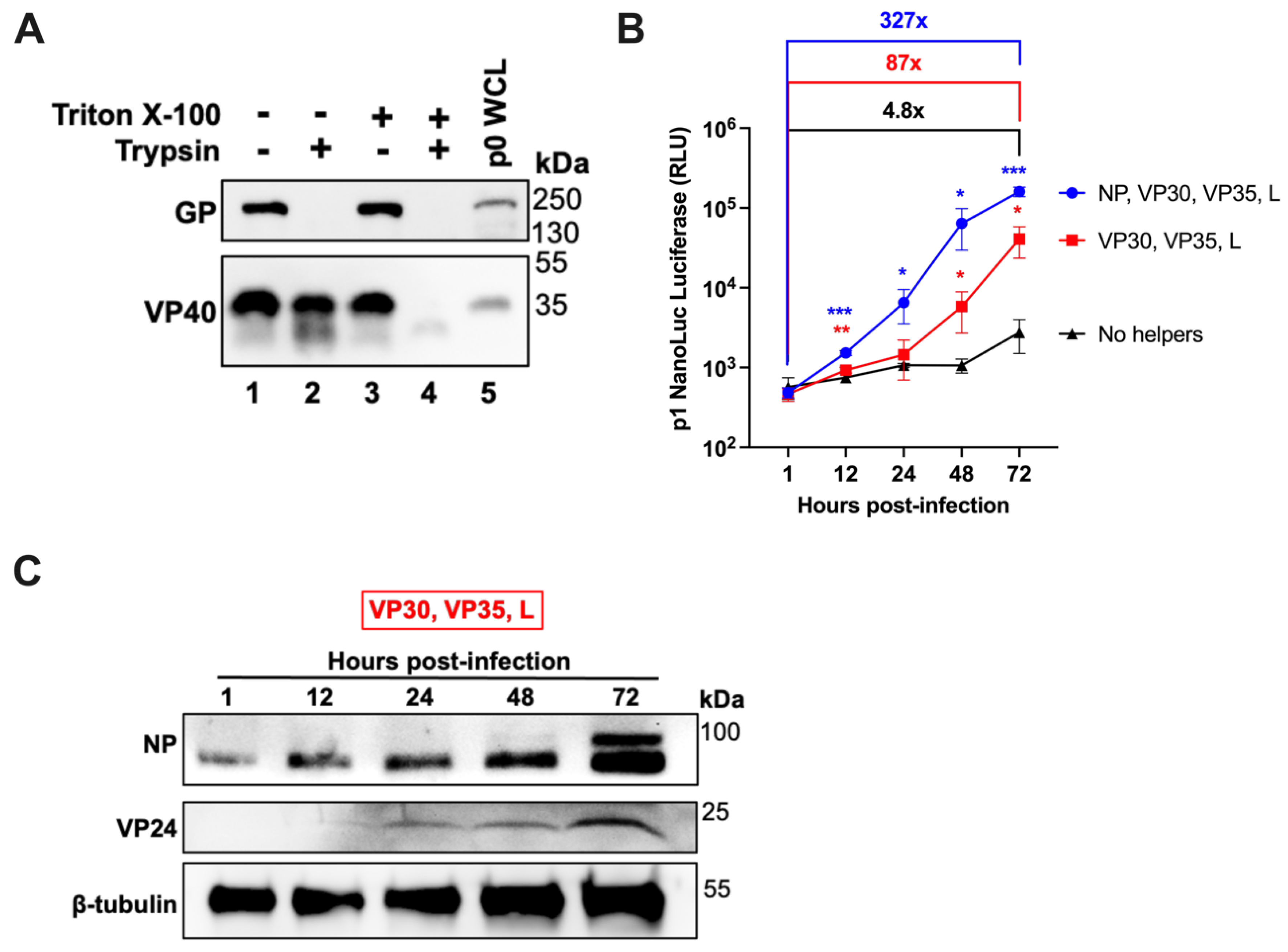

3.3. 5xMG Replication Generates trVLPs Containing Detectable GP and VP40

An advantage of expressing VP40, GP, and VP24 from the minigenome is the ability to produce trVLPs from P0 producer cells that can be used to infect P1 target cells (

Figure 1B). 5xMG trVLP particle integrity was assessed by a protease protection assay [

27,

28]. trVLPs were concentrated and separated into equal fractions before protease or detergent treatment, followed by viral protein detection by western blot. Under these conditions, VP40 protein was present in trVLPs in the absence of detergent and protease (

Figure 3A, Lane 4). Treating with trypsin alone was insufficient to degrade VP40 (

Figure 3A, Lane 2). If detergent was added to the particles, VP40 was digested by protease, indicating that VP40 was protected within lipid bilayer trVLPs, maintaining particle integrity. In contrast, the GP was completely digested by trypsin without the need for detergent, indicating that the glycoprotein was displayed on the surfaces of the trVLPs (

Figure 3A, Lane 2). These data suggest that the 5xMG can generate production of VP40- and GP-containing trVLPs.

3.4. NP Is Expressed from the Pentacistronic EBOV Minigenome in trVLP-Infected Cells

Previous studies have shown that minigenomes delivered via trVLP infection undergo primary transcription in infected cells, while genome replication and further trVLP formation occur when helper proteins are supplied

in trans [

7]. To assess the infectivity of 5xMG trVLPs, a Huh7 hepatocyte model was used in the presence and absence of helper proteins. When none of the helper proteins were present, there was a 4.8-fold increase in reporter signal from 1 to 72 hours post-infection (

Figure 3B, black line). When all helper proteins were supplied to infected cells via expression plasmid transfection, the 5xMG signal was amplified over 300-fold throughout 72-hour time period (

Figure 3B, blue line). This robust increase in 5xMG activity in the presence of all helper proteins was consistent with previously reported findings using 4xMG [

7]. Notably, if the NP helper plasmid was absent from the transfection, there was still an 87-fold increase in luciferase signal, significantly stronger than without any helpers (

Figure 3B, red line). These data suggest that the NP provided from the 5xMG is sufficient to support transcription and replication of the minigenome RNA if other EBOV helper proteins are provided from plasmids. The levels of NP and VP24 proteins in cell lysates lacking NP pre-transfection correlated with the increasing reporter signal (

Figure 3C). Together, these findings indicate that 5xMG can generate infectious trVLPs and enable NP and VP24 co-expression from the minigenome in infected cells.

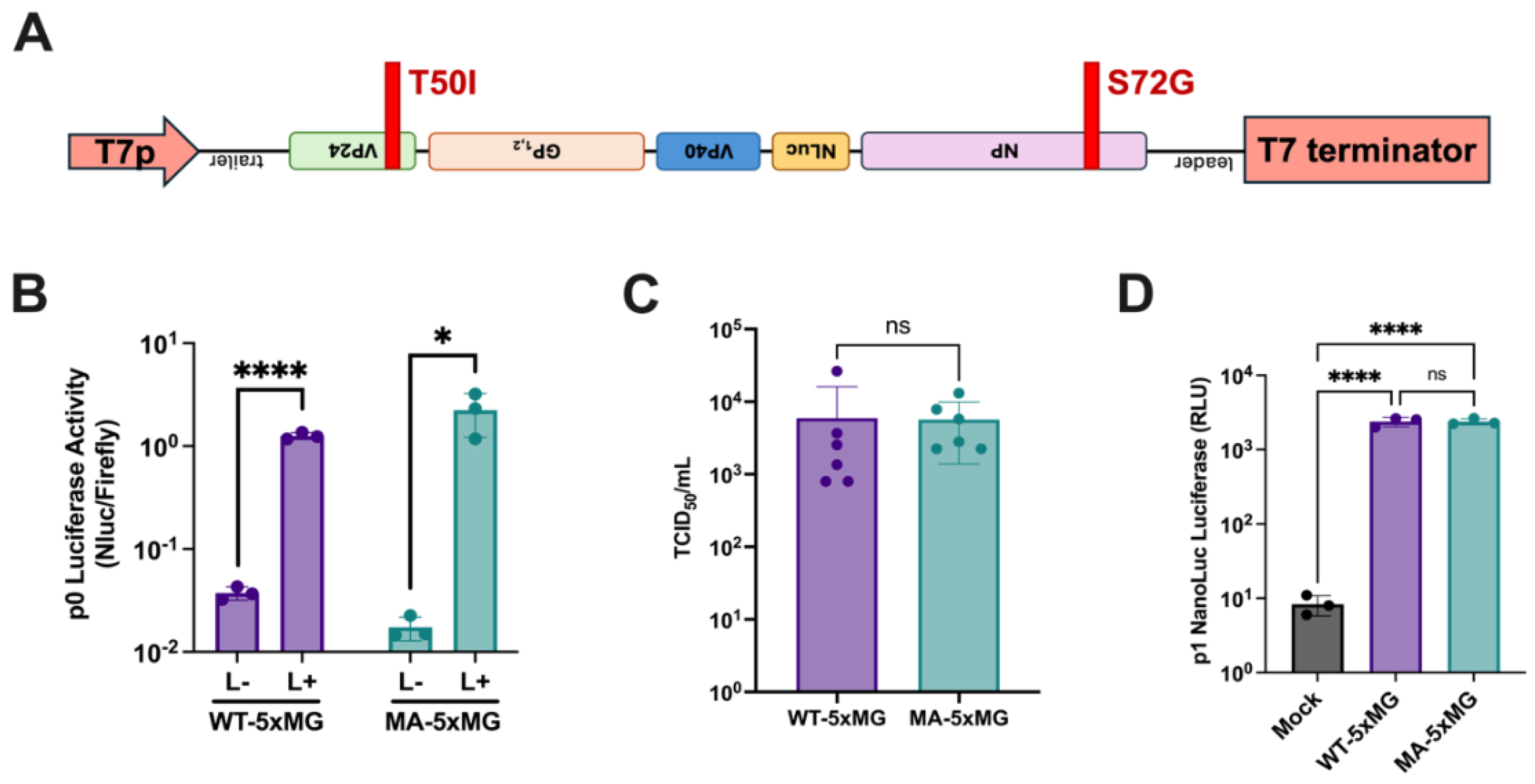

3.5. Introduction of Mouse-Adaptation Mutations Does Not Significantly Impact 5xMG Reporter Activity and trVLP Infectivity

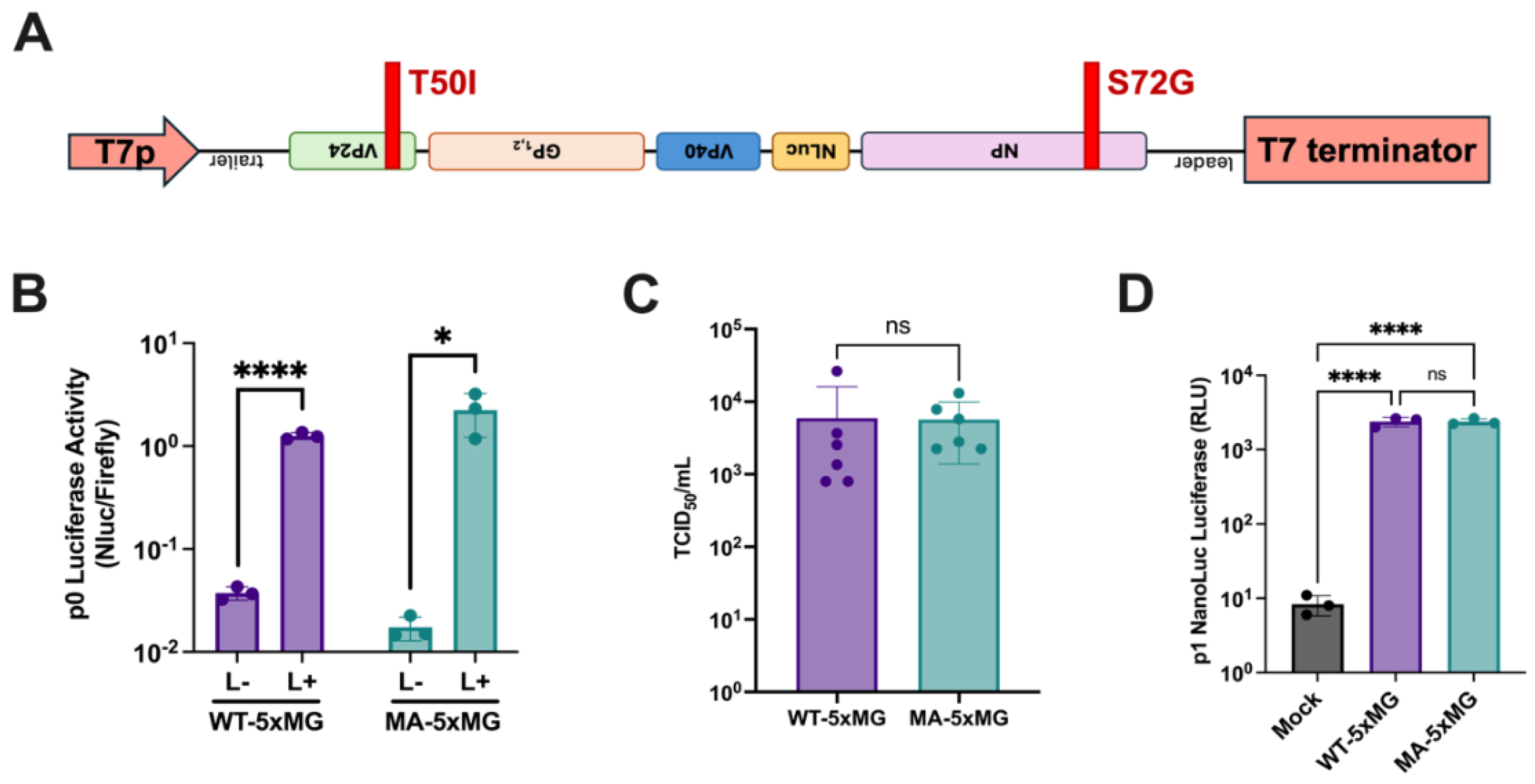

EBOV 5xMG was next modified with the two key virulence determinant mutations in MA-EBOV: S72G in NP and T50I in VP24 (

Figure 4A). MA-5xMG mediated similar activity to WT-5xMG with significant induction of luciferase when comparing L+ to L- samples (

Figure 4B). This indicates that the MA mutations did not appreciably impact 5xMG replication or transcription in 293T cells.

Determining trVLPs titers is essential for conducting comparative functional analyses between WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLPs. The initial titration was attempted by quantifying vRNA within trVLPs by RT-qPCR. However, the resulting amplification indicated the presence of trailer and NP sequences in a control sample where no reverse transcriptase was added, despite no such amplification in the no-template control (

Supplementary Figure 2); this suggests the presence of a carried-over plasmid DNA template. This aberrant amplification occurred despite successive treatments of RNA with two different DNAses. Thus, we instead evaluated the applicability of a bioluminescent endpoint dilution assay to assess the infectivity of trVLPs. Briefly, VeroE6 cells, which are commonly used for rescue and titration of infectious WT- and MA-EBOV [

29,

30], were infected with varying dilutions of trVLPs then subjected to luciferase reporter assays for the calculation of a TCID

50. This method demonstrated similar rescue efficiency of WT- and MA-trVLPs (

Figure 4C).

3.6. trVLP Infection Delivers 5xMG into Mouse Macrophages for Primary Transcription

Macrophages are the primary target for EBOV and thus critically involved in EBOV pathogenesis [

31,

32]. We therefore tested trVLP infectivity in a mouse macrophage cell line, RAW264.7, which has been previously demonstrated to be infected by WT- and MA-EBOV [

21,

33]. When RAW264.7 cells were infected with 650 TCID

50 of WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLPs, both produced similar luciferase activity, suggesting no significant differences in primary transcription (

Figure 4D). This result demonstrates successful delivery of the minigenome to RAW264.7 cells for MG-encoded gene expression.

3.7. Mouse-Adapted 5xMG-trVLP Induces Dampened Innate Immune Response in Murine Macrophages

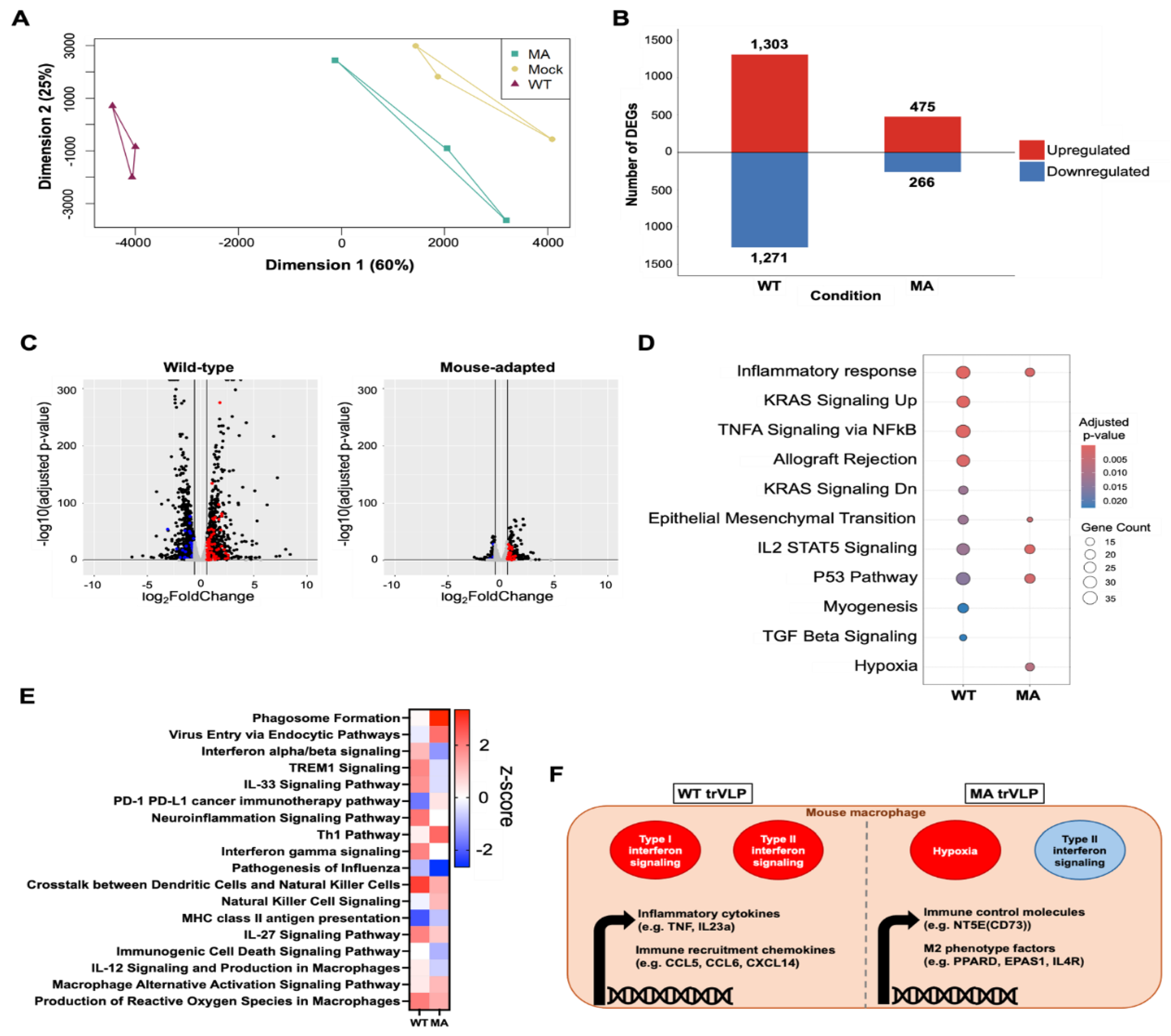

Our 5xMG-trVLP system offers an authentic tool for co-supplying several EBOV proteins, including NP and VP24, in mouse macrophages. Using this system, we conducted RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) to assess global host responses associated with MA mutations in NP and VP24, with the goal of gaining further understanding into the mutant’s possible roles in virulence acquisition. RAW264.7 cells were infected in triplicate with 6.5E3 TCID

50 of WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLPs and next generation RNA-seq was performed on the extracted RNA (

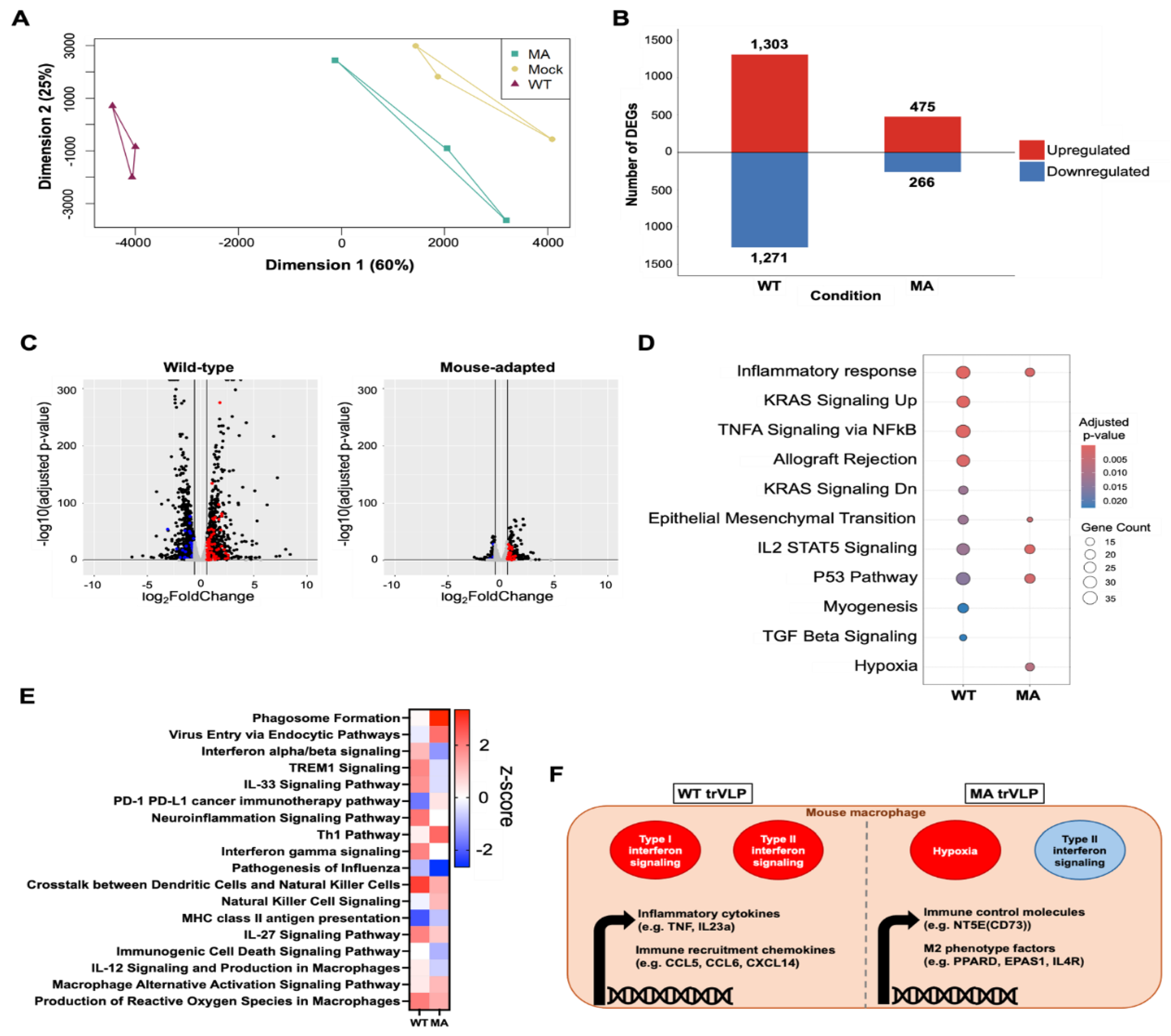

Figure 5). Multidimensional scaling (MDS) of the triplicate samples indicated similarity in magnitude and directionality among replicates, while clearly distinguishing between the uninfected mock, WT, and MA groups (

Figure 5A). More pronounced gene expression changes were observed in WT 5xMG-trVLP infection compared to MA 5xMG-trVLP: 1,303 genes upregulated, and 1,271 genes downregulated for WT 5xMG-trVLPs; 475 genes upregulated, and 266 genes downregulated for MA 5xMG-trVLPs (

Figure 5B).

Because prior literature indicates a role of innate immunity in mouse-adaptation of EBOV, we performed differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis focused on the ‘Immune Effector Process’ from the Gene Ontology Biological Processes (GOBP), sourced from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) [

35,

36,

37,

38]. We observed a highly active transcriptional profile for macrophages infected with WT 5xMG-trVLP compared to the MA 5xMG-trVLP infection (

Figure 5C). This comparison identified 70 significant DEGs related to immune cell effector functions with a stark increase in immune effector upregulation in WT 5xMG-trVLP-infected cells, while MA 5xMG-trVLP infection led to a less pronounced upregulation of only 35 of these genes (

Figure 5C,

Supplementary Figure 3). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using Hallmark gene sets from MSigDB revealed preferential upregulation of genes involved in innate immune pathways, including ‘Inflammatory response’, ‘TNFα Signaling via NFκB, and ‘IL2 STAT5 Signaling’ in response to WT-5xMG-trVLP infection (

Figure 5D). In contrast, MA-5xMG-trVLP infection resulted in less genes fitting the significance criteria of this analysis. Some immune-related gene sets, such as ‘Inflammatory response’ and ‘IL-2 STAT5 Signaling’, were shown to be enriched but associated with a smaller number of genes compared to WT (

Figure 5D,

Supplementary Figure 4). Of note, QIAGEN Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) [

39] also predicted distinct activation and inhibition states between the groups, with both IFN-α/β and IFN-γ signaling pathways showing lower activation in the MA group compared to the WT group (

Figure 5E). Taken together, these data suggest that MA-mutated NP and VP24 may contribute to a reduced innate immune response in mouse macrophages following infection (

Figure 5F).

4. Discussion

In this work, we developed a novel minigenome system to model EBOV infections under BSL-2 conditions. Here, we generated minigenomes that produce viral RNA genomes that not only encode the standard three EBOV genes found in 4xMGs (VP24, VP40, and GP), but also NP which plays critical roles in the viral life cycle. These 5xMGs, therefore, allow exploration of the biology of NP with MGs and trVLPs at BSL-2 that was not feasible previously with 4xMGs or that could only be explored under BSL-4 conditions with infectious EBOV or MA-EBOV viruses.

We applied this new tool in proof-of-concept studies that begin to examine the role of NP and VP24 in MA-EBOV [

21]. We show the successful production of WT- and MA-EBOV trVLPs and their ability to infect cells, to transcribe genome-encoded proteins, and when assisted with EBOV helper proteins VP30, VP35, and L, to replicate the genome and amplify mRNA and protein production. Importantly, our data also demonstrate the successful delivery and primary transcription of the 5xMG in mouse macrophage cell line RAW264.7 through trVLP infection (

Figure 4D).

A system that can assess the cellular response of macrophages to WT- and MA-trVLPs is essential, given that studies have highlighted the crucial role of macrophages in MA-EBOV pathogenicity in mice and hamsters [

20,

40]. While there are other potential methods of gene delivery to cells, including transfection of nucleic acids and lentivirus expression systems, macrophages face key technical challenges: low transfection efficiency and extreme sensitivity to stimuli that activate immune responses. In contrast, the 5xMG approach through trVLP infection not only enables simultaneous expression of NP and VP24 in macrophages, but also more accurately mimics authentic viral protein expression and cellular immune response than other potential gene delivery methods. It is also important to note that our RNA-seq results obtained from WT-5xMG trVLP infections identified multiple DEGs which have been previously identified during EBOV infection in mononuclear cells: Arid5a, CD80, and Ptafr from the ‘Immune Effector’ GOBP gene set and Gadd45a, Ccrl2, CD80, Ccl5, and TNF from the ‘TNFα signaling via NFκB’ Hallmark gene set (

Supplementary Figure 3A, 4A) [

10,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. These associations support the integrity of our 5xMG-trVLP system to investigate host transcriptomics in EBOV infection.

Although previous work identified that S72G in NP and T50I in VP24 are both required to confer virulence to MA-EBOV [

21], the exact role(s) which these mutations play remains elusive. Results from previous studies point to a hypothesis that the nature of MA-EBOV pathogenesis lies in overcoming host innate immunity, demonstrated by: susceptibility of IFN-α/β receptor (IFNAR)-knockout and mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS)-knockout mice to WT-EBOV [

52,

53] and a resistance of MA-EBOV to type I IFN treatment [

21]. Notably, our transcriptomic analysis revealed a stark difference in the cellular innate immune responses between WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLP infections; while WT-5xMG-trVLP infection demonstrated substantial upregulation of inflammatory and innate immune-related genes, including genes associated with type I and type II IFN pathways (e.g., FcgR1a, TNF, and Ahr), such enrichment was absent in MA-5xMG-trVLP infection (

Figure 5,

Supplementary Figures 3-4). This finding is suggestive of a blunted innate immune response in murine macrophages by MA-5xMG-trVLP infection. One of the pathways enriched by WT-5xMG-trVLP infection but not MA-5xMG-trVLPs was ‘IL2 STAT5 signaling’. Of note, VP24 has a well-described canonical type I IFN antagonism by binding karyopherin α to prevent nuclear translocation of STAT1/STAT2 complexes [

54]. To our knowledge, the impact of VP24 on STAT5 translocation has not been investigated, making it an interesting area to explore potential novel mechanisms of immune modulation mechanisms by MA-VP24. Interestingly, GSEA using Hallmark gene sets only identified a few genes more upregulated in MA-5xMG-trVLP infection than WT-5xMG-trVLP. One such gene was NT5E which encodes CD73, a protein with immunosuppressive consequence (

Supplementary Figure 4A-C). This could be a potential function by which MA-EBOV initiates infection in murine macrophages more efficiently than WT-EBOV. Further study will focus on elucidating the interaction between the identified genes/pathways and MA-NP and -VP24 to better understand the mechanisms of EBOV virulence acquisition in mice.

Though it has been demonstrated that MA-EBOV replicates more efficiently than WT-EBOV in mouse monocytes [

21], we did not observe any differences in reporter signal between WT-5xMG trVLP and MA-5xMG trVLP following infection of RAW264.7 cells (

Figure 4D). This is likely due to the absence of viral helper proteins in the trVLP-infected cells which are necessary to support the replication of the minigenome and is a limitation of our study. The RAW264.7 cell line is known to be difficult to transfect with plasmid DNA and the length of L genes also prevent it from being efficiently packaged in vectors for lentiviral transduction. In future studies, we will test transient transfection of helper-encoding mRNAs to evaluate minigenome replication in these critical cells.

The present study demonstrates that the T7 polymerase-driven 5xMG generates significantly higher reporter activity in transfected 293T cells compared to the pol II-driven 5xMG systems (CMVp and CAGp), using 125 ng minigenome plasmid in a 12-well plate format. Interestingly, this promoter preference appears to be reversed in the case of monocistronic EBOV minigenomes [

24]; when 250 ng or less of the minigenome plasmid was used for transfection at the same scale, reporter activity was markedly higher with the CAGp system than with the T7p system. These insights suggest that genome length-dependent effects may influence the efficiency of different transcription systems. It is possible that changes in genome length affect the RNA secondary structures, potentially altering the cleavage efficiency of the ribozyme and resulting in nonfunctional minigenome termini [

55]. Further investigation is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms, which could have significant implications for designing viral minigenomes and their applications.

In summary, we demonstrate here a novel, NP gene-containing EBOV polycistronic minigenome system as a useful tool which we applied to the assessment of the host cell responses to MA-5xMGtrVLP infection. Examination of transcriptional profiles in trVLP-infected murine macrophages revealed reduced innate immune responses to the infection of MA-5xMG-trVLP compared to WT. Further investigations into the interactions among EBOV NP, VP24, and host immune responses, may enhance our understanding of EBOV pathogenesis and provide insights for new strategies for therapeutic intervention.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Cell Culture

HEK293T/17 (ATCC, CRL-11268), Huh7 (a kind gift from Dr. Yoshiharu Matsuura, Osaka University), VeroE6 (ATCC CRL-1586), and RAW264.7 (ATCC TIB-71) cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% (v/v) penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

5.2. Plasmids

EBOV (Mayinga variant) protein expressing plasmids pCAGGS-NP, -VP35, -VP30, and -L were previously generated and described [

56,

57]. The initial tetracistronic minigenome plasmid was generated by assembling four synthesized gene fragments (GenScript Biotech) into a plasmid backbone. The pentacistronic minigenome plasmid was generated by inclusion of the NP ORF into the tetracistronic minigenome plasmid through In-Fusion® (Takara Bio) cloning of an NP sequence-containing PCR product. The minigenome constructs driven by CAG and T7 promoters were generated by traditional restriction enzyme cloning and PCR techniques. The mouse-adaptation mutations were introduced to the pentacistronic minigenome through PCR mutagenesis of NP and VP24 fragments using iProof High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Bio-Rad) followed by In-Fusion® (Takara Bio) ligation. After purification, plasmid preparations were performed with endotoxin-free DNA purification kits and/or subjected to endotoxin removal. Plasmid sequences were confirmed via Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing before use.

5.3. Minigenome Transfections

For p0 transfections, HEK293T cells were seeded in 6-well plates. After 24 hours, cells were transfected with a mixture comprising a 3:1 ratio of TransIT-LT1 Transfection Reagent (Mirus Bio) with plasmid DNA in OptiMEM media (Gibco). Plasmid amounts for 4xMG: NP 125 ng, VP35 125 ng, VP30 75 ng, L 1,000 ng, and minigenome 250 ng. Plasmid amounts for 5xMG: NP 75 ng, VP35 125 ng, VP30 250 ng, L 500 ng, and minigenome 125 ng. For experiments utilizing a T7 polymerase-driven minigenome, 250 ng of pCAGGS-T7pol was included in transfection reactions. To control for transfection efficiency, 10 ng of a pCAGGS-Luc2, which encodes a firefly luciferase gene, was included in each reaction.

5.4. Minigenome Plasmid Titration

Helper plasmid titrations were conducted in HEK293T cells seeded in 12-well plates. Plasmid quantities were increased from 0 ng up to 0.5 to 1.5 µg, depending on the plasmid size. To compensate for changes in total plasmid in each reaction, an empty pCAGGS vector was used to account for total plasmid deficit. Cells were transfected with a mixture comprising a 3:1 ratio of TransIT-LT1 Transfection Reagent (Mirus Bio) with plasmid DNA in OptiMEM media (Gibco). Following a 72-hour incubation, whole cell lysates were harvested in 1x Passive Lysis Buffer (PLB) and used for NanoLuc Dual Reporter Assay (Promega).

5.5. Luciferase Reporter Assays

NanoLuc and NanoLuc Dual Reporter Assays (Promega) were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were lysed in 1x PLB before use. All luciferase assays were run in Costar 96-well white opaque plates using a Synergy H1 (Agilent) or GloMax Explorer (Promega) plate reader.

5.6. trVLP Production

trVLPs were generated from minigenome transfections as described above. After 72 hours, cell supernatants were harvested and clarified at 1,000× g for 10 minutes. Clarified trVLP preparations were aliquoted and stored at -80 °C until use.

5.7. trVLP Infection of Helper-Expressing Huh7

Huh7 cells underwent reverse transfection for infection experiments. Transfection was achieved with 75 ng of pCAGGS-NP, 250 ng -VP30, 125 ng -VP35, 500 ng -L, and 250 ng -TIM-1 in OptiMEM media (Gibco) then vortexed with TransIT LT-1 Transfection Reagent (Mirus Bio) at a 3:1 ratio. Transfection complexes were added to coat 12-well plates for 20 minutes. Huh7 cell suspensions were then added to the wells and incubated overnight, followed by trVLP infection the next day. Clarified trVLP-containing supernatant (400 µl) was transferred to each well for infection, incubated at 37 °C with gentle rocking of the plate in 15-minute intervals. Incubations were carried out at 37 °C from 1 to 72 hours before harvest in 1x PLB for downstream luciferase assay or western blot.

5.8. Protease Protection Assay

trVLPs used for protease protection assay were concentrated via ultracentrifugation. Following clarification at 1,000× g, trVLP supernatant was loaded into ultracentrifuge tube above 20% sucrose cushion. Samples were spun at 32,000 rpm in a Beckman Coulter Optima L-80 XP Ultracentrifuge for 2 hours before removal of the media/sucrose mixture and gentle pellet resuspension in 1x PBS. Samples were then mixed with 0.1% trypsin, 1% Triton X-100, or a combination of both before a 30-minute incubation at room temperature. Samples were then prepared for Western blotting.

5.9. Western Blotting

Samples were mixed 1:1 with Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad) then heated at 95 °C for 10 minutes before being loaded and ran on a 4-15% gradient polyacrylamide SDS-PAGE gel (Mini-PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free Gel, Bio-Rad). After electrophoresis, the protein was transferred using a Trans-Blot SD Semi Dry Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad) to PVDF membrane for blotting. VP40 detection was achieved with a mouse anti-VP40 antibody (5B12, IBT Bioservices) diluted at 1:2,000, then an anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP) secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted at 1:10,000. For NP and GP detection, a custom rabbit polyclonal antibody against the NP peptide sequence “Cys-PAVSSGKNIKRT” (Biomatik) and rabbit anti-EBOV GP pAb (IBT Bioservices) diluted 1:2,000 were used, followed by secondary detection with anti-rabbit HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling Technologies) diluted 1:10,000. β-tubulin was detected with rabbit polyclonal anti-β-tubulin antibody (Abcam) diluted 1:2,000 and utilized the previously described anti-rabbit secondary. Western blots were sensitized using SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged on a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc.

5.10. Titration of trVLPs via Bioluminescence

Titration was calculated via TCID

50 using a luciferase-based endpoint dilution assay as previously described [

58,

59]. Briefly, VeroE6 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate 24 hours before infection. trVLP preparations were diluted in 5-fold increments in serum-free DMEM and 100 µl was added to each well for infection. Infections were incubated for 1 hour at 37 °C with gentle rocking of the plate in 15-minute intervals. After 72 hours, cells were lysed in 1x PLB and used for NanoLuc Luciferase Reporter Assay. Wells with luciferase signal three times higher than background wells were considered positive. TCID

50 for each trVLP preparation was calculated using the Spearman-Kärber method [

60].

5.11. RT-qPCR Assays

RNA extraction was performed by lysing trVLPs in TRIzol LS (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Purification was achieved with Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research) with in-column DNase I treatment according to manufacturer’s directions. vRNA quantification was conducted using 2-step RT-qPCR methods. Reverse transcription was performed using the SuperScript III or SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) per manufacturer’s instructions with an EBOV trailer-specific primer (sequence: CTATATTTAGCCTCTCTCCC) for vRNA amplification. The resulting cDNA was subjected to qPCR with SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems). Primers used: EBOV trailer fwd “GTTGCGTTAAATTCATTGCG”; EBOV trailer rev “CTATATTTAGCCTCTCTCCC”; EBOV NP fwd “GCAAGACGAGCAACAAGATC”; EBOV NP rev “CAGCATCAAATGGCCCCTGTG”. Cycling conditions are as follows: initial denaturation at 50 °C for 2 minutes then 95 °C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 15 sec denaturation at 95 °C and 1 min annealing/extension step. Quantification was done comparing Ct values to a standard curve. Standard curve was generated by using dilutions of an in vitro-transcribed pentacistronic minigenome RNA species. Assays were conducted with an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 and analyzed with its QuantStudio Design and Analysis software.

5.12. trVLP Infection of RAW264.7

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in 12-well plates and incubated overnight before infection. For the initial comparison between WT- and MA-5xMG trVLPs, 6.5E2 TCID50 of each preparation were added to the cell monolayers. Infections were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours before harvest in 1x PLB and downstream luciferase assay as described above. For the infection preceding RNA sequencing, RAW264.7 monolayers were infected with 6.5E3 TCID50 of WT- and MA-trVLPs for 24 hours before RNA extraction. Cells were lysed in TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and RNA was purified using Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research) with in-column DNase I treatment according to manufacturer’s directions. Purified RNA was frozen at -80 °C prior to submission for RNA sequencing.

5.13. RNA Sequencing and Analysis

RNA library preparation and sequencing was conducted at Azenta Life Sciences (South Plainfield, NJ, USA) as follows:

5.14. Library Preparation with PolyA Selection/rRNA Depletion and Illumina Sequencing

Total RNA samples were quantified using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and RNA integrity was checked using Agilent TapeStation 4200 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix (Cat: #4456740) from ThermoFisher Scientific, was added to normalize total RNA prior to library preparation following manufacturer’s protocol. RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina using manufacturer’s instructions (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). Briefly, mRNAs were initially enriched with Oligo (dT) beads. Enriched mRNAs were fragmented for 15 minutes at 94 °C. First strand and second strand complementary DNA (cDNA) were subsequently synthesized. RNA molecules were converted into cDNA and incorporated UMIs during reverse transcription. cDNA fragments were end repaired and adenylated at 3’ ends, and universal adapters were ligated to cDNA fragments, followed by index addition and library enrichment by PCR with limited cycles. The sequencing library was validated on the Agilent TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), and quantified by using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as well as by quantitative PCR (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA). The sequencing libraries were multiplexed and clustered onto a flowcell on the Illumina NovaSeq instrument according to manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were sequenced using a 2 × 150 bp Paired End (PE) configuration. Image analysis and base calling were conducted by the NovaSeq Control Software (NCS). Raw sequence data (.bcl files) generated from Illumina NovaSeq was converted into fastq files and de-multiplexed using Illumina bcl2fastq 2.20 software. One mis-match was allowed for index sequence identification.

5.15. Data Analysis

After investigating the quality of the raw data, sequence reads were trimmed to remove possible adapter sequences and nucleotides with poor quality (Phred cutoff of 36) using Trimmomatic v.0.36 [

61]. The trimmed reads were mapped to the reference genome (GRCm38) available on ENSEMBL using the STAR aligner v.2.5.2b [

62]. Raw count values were generated using the featureCounts package from Subread v.1.5.2 in R v.3.4.1 [

63,

64]. Only unique reads that fell within exon regions were counted. The resulting read counts were imported into R and differentially expressed genes were identified using Wald test in DESEq2 [

65]. Genes with fold change relative to time-matched, mock-infected controls > |1.5| (log2FC > |0.585|) and adjusted P-values < 0.05 were identified as DEG and selected for further analysis. MDS plots were generated using raw count data and the plotMDS function from limma (v3.58.1) [

66]. Bar graphs showing total DEG were generated using ggplot2 v3.5.1 and R v4.3.3 [

67]. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed to analyze DEGs using hallmark gene sets available from the most recent release of the Mouse Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) and clusterProfiler v4.10.1 in R v4.3.3 [

37,

68,

69,

70]. Pathways that contained 10 or more DEGs were selected for analysis. Dot plots showing clusterProfiler enrichment results from hallmark gene sets were generated using enrichplot [

71]. Volcano plots representing all genes from DESEq2 results were generated using ggplot2 and R v4.3.3. DEG within the MSigDB gene set “GOBP_IMMUNE_EFFECTOR_PROCESS” (GO:0002252, MM4211) meeting significance criteria were colorized according to log2FC value. Heatmaps were generated using MSigDB hallmark gene sets and pheatmap v1.0.12 in R v4.3.3 [

72].

Pathway comparison analysis was conducted with the use of QIAGEN IPA (QIAGEN Inc.,

https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/IPA) using the most recent knowledgebase update of IPA at the time of writing (fall 2024) [

39]. Immune-related pathways (Metabolic Pathways: None; Reactome Pathways: Immune System; Signaling Pathways: Cellular Immune Response, Cytokine Signaling, Humoral Immune Response, Pathogen-Influenced Signaling) with p-value < 0.05 were selected for comparison analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Comparison of Tetra- and Pentacistronic EBOV Minigenomes. Figure S2: Quantification of vRNA from trVLP-containing Supernatant Via RT-qPCR Shows Aberrant Amplification in Control Conditions. Figure S3: Up- and Downregulated GOBP ‘Immune Effector’ Genes in 5xMG trVLP-infected Murine Macrophages. Figure S4: Up- and Downregulated Hallmark Immune Gene Sets in 5xMG trVLP-infected Murine Macrophages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z., M.B., S.Y. and H.E.; Methodology, B.Z., V.S. and S.Y.; Software, V.S.; Validation, B.Z.; Formal Analysis, B.Z. and V.S.; Investigation, B.Z., S.C.L. and L.W.; Resources, B.Z., S.C.L. and L.W.; Data Curation, B.Z., V.S. and S.Y.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, B.Z., V.S. and S.Y.; Writing—Review & Editing, B.Z., V.S., S.C.L., L.W., M.B., H.E. and S.Y.; Visualization, B.Z. and V.S.; Supervision, M.B. and S.Y.; Project Administration, M.B. and S.Y.; Funding Acquisition V.S., M.B. and H.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by Mayo Clinic’s Foundation for Medical Education and Research and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI134937-01A1). This work was partially supported by grant T32 AI132165 from the National Institutes of Health awarded to VAS. The opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by Mayo Clinic or the NlH.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. RNA-seq results are openly available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive at

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1191138 or at BioProject ID: PRJNA1191138.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank colleagues at Mayo Clinic for their insightful discussion and Carla Weisend for her excellent technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rugarabamu, S.; Mboera, L.; Rweyemamu, M.; Mwanyika, G.; Lutwama, J.; Paweska, J.; Misinzo, G. Forty-two years of responding to Ebola virus outbreaks in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e001955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letafati, A.; Salahi Ardekani, O.; Karami, H.; Soleimani, M. Ebola virus disease: A narrative review. Microb. Pathogenesis 2023, 181, 106213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Prioritizing diseases for research and development in emergency contexts. Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/prioritizing-diseases-for-research-and-development-in-emergency-contexts (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Flint, J.; Racaniello, V.R.; Rall, G.F.; Skalka, A.M. Priniciples of Virology, 4th ed.; ASM Press, 2015; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Hoenen, T.; Groseth, A.; de Kok-Mercado, F.; Kuhn, J.H.; Wahl-Jensen, V. Minigenomes, transcription and replication competent virus-like particles and beyond: Reverse genetics systems for filoviruses and other negative stranded hemorrhagic fever viruses. Antiviral Res. 2011, 91, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhlberger, E.; Weik, M.; Volchkov, V.E.; Klenk, H.-D.; Becker, S. Comparison of the Transcription and Replication Strategies of Marburg Virus and Ebola Virus by Using Artificial Replication Systems. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 2333–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, A.; Moukambi, F.; Banadyga, L.; Groseth, A.; Callison, J.; Herwig, A.; Ebihara, H.; Feldmann, H.; Hoenen, T. A Novel Life Cycle Modeling System for Ebola Virus Shows a Genome Length-Dependent Role of VP24 in Virus Infectivity. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 10511–10524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Watanabe, T.; Noda, T.; Takada, A.; Feldmann, H.; Jasenosky, L.; Kawaoka, Y. Production of Novel Ebola Virus-Like Particles from cDNAs: an Alternative to Ebola Virus Generation by Reverse Genetics. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenen, T.; Groseth, A.; Kolesnikova, L.; Theriault, S.; Ebihara, H.; Hartlieb, B.; Bamberg, S.; Feldmann, H.; Ströher, U.; Becker, S. Infection of naive target cells with virus-like particles: implications for the function of ebola virus VP24. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 7260–7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfield, K.L.; Bosio, C.M.; Welcher, B.C.; Deal, E.M.; Mohamadzadeh, M.; Schmaljohn, A.; Aman, M.J.; Bavari, S. Ebola virus-like particles protect from lethal Ebola virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003, 100, 15889–15894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, K.L.; Swenson, D.L.; Olinger, G.G.; Kalina, W.V.; Aman, M.J.; Bavari, S. Ebola Virus-Like Particle-Based Vaccine Protects Nonhuman Primates against Lethal Ebola Virus Challenge. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, S430–S437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Claire, M.C.; Ragland, D.R.; Bollinger, L.; Jahrling, P.B. Animal Models of Ebolavirus Infection. Comp. Med. 2017, 67, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bray, M.; Davis, K.; Geisbert, T.W.; Schmaljohn, C.; Huggins, J. A Mouse Model for Evaluation of Prophylaxis and Therapy of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever. J. Infect. Dis. 1998, 178, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, M.; Hatfill, S.; Hensley, L.; Huggins, J. Haematological, biochemical and coagulation changes in mice, guinea-pigs and monkeys infected with a mouse-adapted variant of Ebola Zaire virus. J. Comp. Pathol. 2001, 125, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volchkov, V.E.; Chepurnov, A.A.; Volchkova, V.A.; Ternovoj, V.A.; Klenk, H.-D. Molecular Characterization of Guinea Pig-Adapted Variants of Ebola Virus. Virology 2000, 277, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, S.; Gupta, M.; Paragas, J.; Bray, M.; Ahmed, R.; Rollin, P.E. Protection From Lethal Infection is Determined by Innate Immune Responses in a Mouse Model of Ebola Virus Infection. Virology 2003, 312, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spengler, J.R.; Welch, S.R.; Ritter, J.M.; Harmon, J.R.; Coleman-McCray, J.D.; Genzer, S.C.; Seixas, J.N.; Scholte, F.E.M.; Davies, K.A.; Bradfute, S.B.; Montgomery, J.M. Mouse models of Ebola virus tolerance and lethality: characterization of CD-1 mice infected with wild-type, guinea pig-adapted, or mouse-adapted virus. Antiviral Res. 2023, 210, 105496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradfute, S.B.; Warfield, K.L.; Bavari, S. Functional CD8+ T cell responses in lethal Ebola virus infection. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 4058–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradfute, S.B.; Braun, D.R.; Shamblin, J.D.; Geisbert, J.B.; Paragas, J.; Garrison, A.; Hensley, L.E.; Geisbert, T.W. Lymphocyte Death in a Mouse Model of Ebola Virus Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, S296–S304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, T.R.; Bray, M.; Geisbert, T.W.; Steele, K.E.; Kell, W.M.; Davis, K.J.; Jaax, N.K. Pathogenesis of experimental Ebola Zaire virus infection in BALB/c mice. J. Comp. Pathol. 2001, 125, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebihara, H.; Takada, A.; Kobasa, D.; Jones, S.; Neumann, G.; Theriault, S.; Bray, M.; Feldmann, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Molecular Determinants of Ebola Virus Virulence in Mice. PLoS Pathogens 2006, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, H.; Mora, A.; Watt, A.; Hoenen, T. Modeling The Lifecycle of Ebola Virus Under Biosafety Level 2 Conditions with Virus-like Particles Containing Tetracistronic Minigenomes. J. Visualized Exp. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlberger, E. Filovirus replication and transcription. Future Virology 2007, 2, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.V.; Pacheco, J.R.; Hume, A.J.; Cressey, T.N.; Deflube, L.R.; Ruedas, J.B.; Connor, J.H.; Ebihara, H.; Muhlberger, E. An RNA Polymerase II-Driven Ebola Virus Minigenome System as an Advanced Tool for Antiviral Drug Screening. Antiviral Res. 2017, 146, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uebelhoer, L.S.; Albariño, C.G.; McMullan, L.K.; Chakrabarti, A.K.; Vincent, J.P.; Nichol, S.T.; Towner, J.S. High-throughput, luciferase-based reverse genetics systems for identifying inhibitors of Marburg and Ebola viruses. Antiviral Res. 2014, 106, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Dorival, I.; Wu, W.; Armstrong, S.D.; Barr, J.N.; Carroll, M.W.; Hewson, R.; Hiscox, J.A. Elucidation of the Cellular Interactome of Ebola Virus Nucleoprotein and Identification of Therapeutic Targets. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15, 4290–4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.F.; Bell, P.; Harty, R.N. Effect of Ebola virus proteins GP, NP and VP35 on VP40 VLP morphology. Virol. J. 2006, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasenosky, L.D.; Neumann, G.; Lukashevich, I.; Kawaoka, Y. Ebola virus VP40-induced particle formation and association with the lipid bilayer. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 5205–5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volchkov, V.E.; Volchkova, V.A.; Mühlberger, E.; Kolesnikova, L.; Weik, M.; Dolnik, O.; Klenk, H.-D. Recovery of Infectious Ebola Virus from Complementary DNA: RNA Editing of the GP Gene and Viral Cytotoxicity. Science 2001, 291, 1965–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenen, T.; Groseth, A.; Callison, J.; Takada, A.; Feldmann, H. A novel Ebola virus expressing luciferase allows for rapid and quantitative testing of antivirals. Antiviral Res. 2013, 99, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, K.J.; Maury, W. The Role of mononuclear Phagocytes in Ebola Virus Infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2018, 104, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.; Geisbert, T.W. Ebola virus: The role of macrophages and dendritic cells in the pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2005, 37, 1560–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, J.E.; Wong, G.; Jones, S.E.; Grolla, A.; Theriault, S.; Kobinger, G.P.; Feldmann, H. Stimulation of Ebola Virus Production from Persistent Infection Through Activation of the Ras/MAPK Pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 17982–17987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Data analysis; Springer, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, T.G.O.; Aleksander, S.A.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J.M.; Drabkin, H.J.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N.L.; et al. The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanza, A.S.; Recla, J.M.; Eby, D.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Bult, C.J.; Mesirov, J.P. Extending support for mouse data in the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB). Nature Methods 2023, 20, 1619–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, A.; Green, J.; Pollard, J., Jr.; Tugendreich, S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebihara, H.; Zivcec, M.; Gardner, D.; Falzarano, D.; LaCasse, R.; Rosenke, R.; Long, D.; Haddock, E.; Fischer, E.; Kawaoka, Y.; et al. A Syrian Golden Hamster Model Recapitulating Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 207, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melanson, V.R.; Kalina, W.V.; Williams, P. Ebola Virus Infection Induces Irregular Dendritic Cell Gene Expression. Viral Immunol. 2014, 28, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosio, C.M.; Aman, M.J.; Grogan, C.; Hogan, R.; Ruthel, G.; Negley, D.; Mohamadzadeh, M.; Bavari, S.; Schmaljohn, A. Ebola and Marburg Viruses Replicate in Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells without Inducing the Production of Cytokines and Full Maturation. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 188, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteeg, K.; Menicucci, A.R.; Woolsey, C.; Mire, C.E.; Geisbert, J.B.; Cross, R.W.; Agans, K.N.; Jeske, D.; Messaoudi, I.; Geisbert, T.W. Infection with the Makona variant results in a delayed and distinct host immune response compared to previous Ebola virus variants. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, S.; Sánchez-Aparicio, M.; Seoane, R.; El Motiam, A.; Nelson, E.V.; Bouzaher, Y.H.; Baz-Martínez, M.; García-Dorival, I.; Gonzalo, S.; Vázquez, E.; et al. Expression of the Ebola Virus VP24 Protein Compromises the Integrity of the Nuclear Envelope and Induces a Laminopathy-Like Cellular Phenotype. mBio 2021, 12, e0097221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kash, J.C.; Walters, K.-A.; Kindrachuk, J.; Baxter, D.; Scherler, K.; Janosko, K.B.; Adams, R.D.; Herbert, A.S.; James, R.M.; Stonier, S.W.; et al. Longitudinal peripheral blood transcriptional analysis of a patient with severe Ebola virus disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, O.; Johnson, J.C.; Honko, A.N.; Yen, B.; Shabman, R.S.; Hensley, L.E.; Olinger, G.G.; Basler, C.F. Ebola virus exploits a monocyte differentiation program to promote its entry. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 3801–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, O.; Valmas, C.; Basler, C.F. Ebola virus-like particle-induced activation of NF-κB and Erk signaling in human dendritic cells requires the glycoprotein mucin domain. Virology 2007, 364, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, K.L.; Rollin, P.E. Cytokine and Chemokine Expression in Humans Infected with Sudan Ebola Virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, S357–S363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baize, S.; Leroy, E.M.; Georges, A.J.; Geroges-Courbot, M.-C.; Capron, M.; Bedjabaga, I.; Lansoud-Soukate, J.; Mavoungou, E. Inflammatory responses in Ebola virus-infected patients. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2002, 128, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerber, R.; Krumkamp, R.; Korva, M.; Rieger, T.; Wurr, S.; Duraffour, S.; Oestereich, L.; Gabriel, M.; Sissoko, D.; Anglaret, X.; et al. Kinetics of Soluble Mediators of the Host Response in Ebola Virus Disease. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, S496–S503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, L.E.; Young, H.A.; Jahrling, P.B.; Geisbert, T.W. Proinflammatory Response During Ebola Virus Infection of Primate Models: Possible Involvement of the Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Superfamily. Immunol. Letters 2002, 80, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, M. The Role of the Type I Interferon Response in the Resistance of Mice to Filovirus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2001, 82, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.; Robertson, S.J.; Okumura, A.; Scott, D.P.; Chang, J.; Weiss, J.M.; Sturdevant, G.L.; Feldmann, F.; Haddock, E.; Chiramel, A.I.; et al. A Systems Approach Reveals MAVS Signaling in Myeloid Cells as Critical for Resistance to Ebola Virus in Murine Models of Infection. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 816–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.P.; Valmas, C.; Martinez, O.; Sanchez, F.M.; Basler, C.F. Ebola Virus VP24 Proteins Inhibit the Interaction of NPI-1 Subfamily Karyopherin α Proteins with Activated STAT1. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 13469–13477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanmechelen, B.; Stroobants, J.; Vermeire, K.; Maes, P. Advancing Marburg virus antiviral screening: Optimization of a novel T7 polymerase-independent minigenome system. Antiviral Res. 2021, 185, 104977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuda, Y.; Hoenen, T.; Banadyga, L.; Weisend, C.; Ricklefs, S.M.; Porcella, S.F.; Ebihara, H. An Improved Reverse Genetics System to Overcome Cell-Type-Dependent Ebola Virus Genome Plasticity. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 212 (Suppl. 2), S129–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banadyga, L.; Hoenen, T.; Ambroggio, X.; Dunham, E.; Groseth, A.; Ebihara, H. Ebola virus VP24 interacts with NP to facilitate nucleocapsid assembly and genome packaging. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Y.; Guo, Z.-D.; Li, J.-M.; Zhao, Z.-Z.; Fu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, C.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.-N.; Qian, J.; Liu, L.-N. Genome-Wide Search for Competing Endogenous RNAs Responsible for the Effects Induced by Ebola Virus Replication and Transcription Using a trVLP System. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Y.; Li, J.-M.; Fu, Y.-Y.; Zhao, Z.-Z.; Zhang, C.-M.; Li, N.; Li, J.; Cheng, H.; Jin, X.; Lu, B.; et al. A Rapid Screen for Host-Encoded miRNAs with Inhibitory Effects against Ebola Virus Using a Transcription- and Replication-Competent Virus-Like Particle System. Int. J. Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, M.A. Determination of 50% endpoint titer using a simple formula. World J. Virol. 2016, 5, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Y.; Giles, E.C.; Vahedi, F.; Chew, M.V.; Nham, T.; Loukov, D.; Lee, A.J.; Bowdish, D.M.E.; Ashkar, A.A. IFN-β signalling regulates RAW 264.7 macrophage activation, cytokine production, and killing activity. Innate Immun. 2020, 26, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq Aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2013, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. The R Package Rsubread is Easier, Faster, Cheaper and Better for Alignment and Quantification of RNA Sequencing Reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, e47–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biology 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Xu, S.; Hu, E.; Cai, Y.; Xie, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhan, L.; Tang, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, R.; et al. Using clusterProfiler to Characterize Multiomics Data. Nat. Protocols 2024, 19, 3292–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. The Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: an R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G. Visualization of Functional Enrichment Result. Available online: https://yulab-smu.top/biomedical-knowledge-mining-book/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Kolde, R. pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps. Available online: https://github.com/raivokolde/pheatmap. (accessed on 15 October 2024).

Figure 1.

An NP Gene-containing Pentacistronic EBOV Minigenome for Modeling Infection. A Schematic of the pentacistronic minigenome (5xMG) construct organization. 3’ leader and 5’ trailer sequences are indicated at the genome termini. Viral open reading frames are indicated for NP, VP40, GP, and VP24 genes with the respective intergenic untranslated regions (UTRs) indicated in light blue boxes. A NanoLuc (NLuc) reporter gene is included flanked by VP35 non-coding sequences. B Schematic of 5xMG in producer and target cells. Producer cells (p0) are transfected with plasmids encoding NP, VP30, VP35, L genes and the 5xMG. Replication and transcription of viral RNA (vRNA) can occur to generate complementary RNA (cRNA) and messenger RNA (mRNA). The proteins are then produced via translation and transcription- and replication-competent virus-like particles (trVLPs) are formed and bud from the producer cells. trVLPs can be transferred to target cells (p1) for modeling infection. Following transfection of p1 with plasmids encoding VP30, VP35, and L genes, 5xMG carried by trVLPs is transcribed and replicated as in p0. trVLPs can also be produced from p1 for further infection.

Figure 1.

An NP Gene-containing Pentacistronic EBOV Minigenome for Modeling Infection. A Schematic of the pentacistronic minigenome (5xMG) construct organization. 3’ leader and 5’ trailer sequences are indicated at the genome termini. Viral open reading frames are indicated for NP, VP40, GP, and VP24 genes with the respective intergenic untranslated regions (UTRs) indicated in light blue boxes. A NanoLuc (NLuc) reporter gene is included flanked by VP35 non-coding sequences. B Schematic of 5xMG in producer and target cells. Producer cells (p0) are transfected with plasmids encoding NP, VP30, VP35, L genes and the 5xMG. Replication and transcription of viral RNA (vRNA) can occur to generate complementary RNA (cRNA) and messenger RNA (mRNA). The proteins are then produced via translation and transcription- and replication-competent virus-like particles (trVLPs) are formed and bud from the producer cells. trVLPs can be transferred to target cells (p1) for modeling infection. Following transfection of p1 with plasmids encoding VP30, VP35, and L genes, 5xMG carried by trVLPs is transcribed and replicated as in p0. trVLPs can also be produced from p1 for further infection.

Figure 2.

Plasmid Optimization and the T7 Bacteriophage Promoter Increase the 5xMG Efficiency in Producer Cells A Luciferase assay of 293T cells transfected with CMVp-4xMG or -5xMG at 72 hours post-transfection. Data are shown as NanoLuc luminescence of the L+ condition relative to L-. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired, two-tailed t-tests. B Titration of EBOV helper expression plasmids NP, VP35, VP30, L and the 5xMG plasmid. Plasmid quantities were increased from zero to 1,000 nanograms per reaction. Data are shown as NanoLuc luciferase signal of the L+ condition relative to the L- condition. Cell lysates were harvested 72 hours post-transfection. C Comparison of previous and optimized plasmid quantifies for 5xMG transfection in 293T cells, 72 hours post-transfection. Data are shown as 5xMG luciferase signal relative to transfection control luciferase (NanoLuc/firefly). Conditions are either absent of the pCAGGS-L plasmid (L-) or present for the L plasmid (L+). Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired, two-tailed t-tests. D Schematic of 5xMG expression plasmids with the minigenome cassette in negative sense orientation, flanked by a cytomegalovirus (CMV), chicken beta-actin (CAG), or T7 bacteriophage promoter and a termination element. The CMVp and CAGp constructs both contain a hammerhead ribozyme (HR) and a hepatitis delta virus ribozyme (HDV), indicated by red blocks, for generating precise genome ends. E Promoter selection results as dual luciferase reporter assay 72 hours post-transfection. Conditions are either absent of the pCAGGS-L plasmid (L-) or present for the L plasmid (L+). Data are shown as 5xMG luciferase signal relative to transfection control luciferase (NanoLuc/firefly). Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired, two-tailed t-tests. F Luciferase assay of 293T cells transfected with the 5xMG driven by either the CMV, CAG, or T7 promoters at 96 hours post-transfection. Statistical analysis was performed by an ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. G Luciferase assay of 293T cells transfected with the 4xMG driven by either the CMV, CAG, or T7 promoters at 96 hours post-transfection. Data are shown as NanoLuc luminescence of the L+ condition relative to L-. Statistical analysis was performed by an ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For panels A, B, C, and G, data are shown with mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). For panels E and F, data are shown with mean ± SD (n = 4 independent biological replicates). ns > 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01,*** P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001.

Figure 2.

Plasmid Optimization and the T7 Bacteriophage Promoter Increase the 5xMG Efficiency in Producer Cells A Luciferase assay of 293T cells transfected with CMVp-4xMG or -5xMG at 72 hours post-transfection. Data are shown as NanoLuc luminescence of the L+ condition relative to L-. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired, two-tailed t-tests. B Titration of EBOV helper expression plasmids NP, VP35, VP30, L and the 5xMG plasmid. Plasmid quantities were increased from zero to 1,000 nanograms per reaction. Data are shown as NanoLuc luciferase signal of the L+ condition relative to the L- condition. Cell lysates were harvested 72 hours post-transfection. C Comparison of previous and optimized plasmid quantifies for 5xMG transfection in 293T cells, 72 hours post-transfection. Data are shown as 5xMG luciferase signal relative to transfection control luciferase (NanoLuc/firefly). Conditions are either absent of the pCAGGS-L plasmid (L-) or present for the L plasmid (L+). Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired, two-tailed t-tests. D Schematic of 5xMG expression plasmids with the minigenome cassette in negative sense orientation, flanked by a cytomegalovirus (CMV), chicken beta-actin (CAG), or T7 bacteriophage promoter and a termination element. The CMVp and CAGp constructs both contain a hammerhead ribozyme (HR) and a hepatitis delta virus ribozyme (HDV), indicated by red blocks, for generating precise genome ends. E Promoter selection results as dual luciferase reporter assay 72 hours post-transfection. Conditions are either absent of the pCAGGS-L plasmid (L-) or present for the L plasmid (L+). Data are shown as 5xMG luciferase signal relative to transfection control luciferase (NanoLuc/firefly). Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired, two-tailed t-tests. F Luciferase assay of 293T cells transfected with the 5xMG driven by either the CMV, CAG, or T7 promoters at 96 hours post-transfection. Statistical analysis was performed by an ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. G Luciferase assay of 293T cells transfected with the 4xMG driven by either the CMV, CAG, or T7 promoters at 96 hours post-transfection. Data are shown as NanoLuc luminescence of the L+ condition relative to L-. Statistical analysis was performed by an ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For panels A, B, C, and G, data are shown with mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). For panels E and F, data are shown with mean ± SD (n = 4 independent biological replicates). ns > 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01,*** P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001.

Figure 3.

5xMG-generated trVLPs Infect and Amplify in Huh7 Target Cells A Western blot for EBOV GP and VP40 from 5xMG trVLP fractions subjected to protease protection assay. Treatments of trVLP samples are indicated: PBS (lane 1), trypsin (lane 2), Triton X-100 (lane 3), or trypsin and Triton X-100 (lane 4). Lane 5 is whole cell lysate (WCL) from 5xMG-transfected 293T cells. B NanoLuc luciferase assay of trVLP-infected Huh7 cells. Cells were transfected with the indicated helper protein expression plasmids or an empty vector plasmid. After 24 hours of transfection, cell monolayers were infected with 0.4 mL of clarified trVLP-containing supernatant. Data are shown with mean ± SD (n = 4 independent biological replicates). Statistical analysis was performed as a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001. C Western blot for EBOV NP and VP24 in trVLP-infected Huh7. Whole cell lysates were derived from the ‘VP30, VP35, and L’ samples shown in panel B at the indicated timepoints.

Figure 3.

5xMG-generated trVLPs Infect and Amplify in Huh7 Target Cells A Western blot for EBOV GP and VP40 from 5xMG trVLP fractions subjected to protease protection assay. Treatments of trVLP samples are indicated: PBS (lane 1), trypsin (lane 2), Triton X-100 (lane 3), or trypsin and Triton X-100 (lane 4). Lane 5 is whole cell lysate (WCL) from 5xMG-transfected 293T cells. B NanoLuc luciferase assay of trVLP-infected Huh7 cells. Cells were transfected with the indicated helper protein expression plasmids or an empty vector plasmid. After 24 hours of transfection, cell monolayers were infected with 0.4 mL of clarified trVLP-containing supernatant. Data are shown with mean ± SD (n = 4 independent biological replicates). Statistical analysis was performed as a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001. C Western blot for EBOV NP and VP24 in trVLP-infected Huh7. Whole cell lysates were derived from the ‘VP30, VP35, and L’ samples shown in panel B at the indicated timepoints.

Figure 4.

Introduction of Mouse-Adaptation Mutations Does Not Significantly Impact 5xMG Efficiency A Diagram of the T7p-driven mouse-adapted 5xMG (MA-5xMG). MA mutations were introduced in the NP and VP24 genes at the indicated positions. B Dual luciferase reporter assay results of 293T cells transfected with WT- or MA-5xMG at 72 hours post-transfection. Data are shown as 5xMG luciferase signal relative to transfection control luciferase (NanoLuc/firefly). Conditions are either absent of the pCAGGS-L plasmid (L-) or present for the L plasmid (L+). Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired, two-tailed t-tests. C Titers of WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLP preparations expressed as TCID50/mL. Titrations were completed on VeroE6 cells using bioluminescent end point dilution assay at 72 hours post-infection. Data are shown with mean ± SD (n = 6 independent biological replicates). D NanoLuc luciferase assay results of RAW264.7 cells infected with 6.5E2 TCID50 of WT- or MA-trVLPs at 24 hours post-infection. Statistical analysis was performed by an ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For panels B and D, data are shown with mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). * P ≤ 0.05, **** P ≤ 0.0001.

Figure 4.

Introduction of Mouse-Adaptation Mutations Does Not Significantly Impact 5xMG Efficiency A Diagram of the T7p-driven mouse-adapted 5xMG (MA-5xMG). MA mutations were introduced in the NP and VP24 genes at the indicated positions. B Dual luciferase reporter assay results of 293T cells transfected with WT- or MA-5xMG at 72 hours post-transfection. Data are shown as 5xMG luciferase signal relative to transfection control luciferase (NanoLuc/firefly). Conditions are either absent of the pCAGGS-L plasmid (L-) or present for the L plasmid (L+). Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired, two-tailed t-tests. C Titers of WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLP preparations expressed as TCID50/mL. Titrations were completed on VeroE6 cells using bioluminescent end point dilution assay at 72 hours post-infection. Data are shown with mean ± SD (n = 6 independent biological replicates). D NanoLuc luciferase assay results of RAW264.7 cells infected with 6.5E2 TCID50 of WT- or MA-trVLPs at 24 hours post-infection. Statistical analysis was performed by an ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For panels B and D, data are shown with mean ± SD (n = 3 independent biological replicates). * P ≤ 0.05, **** P ≤ 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Mouse-Adapted 5xMG-trVLP Infection Induces Blunted Innate Immune Response in Mouse Macrophages.

A Multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot showing RNA-sequencing analysis of normalized gene expression in WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLP infected RAW264.7 cells. Dots indicate triplicate samples from each condition.

B DEGs in RAW264.7 cells infected with WT- or MA-5xMG-trVLPs meeting significance criteria. Red bars indicate upregulated genes, and blue bars indicate downregulated genes. Total DEG numbers are listed for each condition.

C Volcano plots displaying DEGs from WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLP infection. The axes indicate the fold change of gene expression and significance of up- and down-regulation. Red dots indicate upregulation, and blue dots indicate downregulation within the Gene Ontology of Biological Processes (GOBP) ‘Immune Effector’ gene set. Black dots indicate genes that are significant but unrelated to GOBP ‘Immune Effector’. Grey dots indicate genes that did not reach significance criteria. Vertical lines indicate log

2FC cutoffs, horizontal line indicates adjusted P-value cutoff. Plots were generated using the R package ggplot2 [

34] v3.5.1. DEG criteria for B-E = fold change relative to mock-infected controls > |1.5|, |log

2FC| > 0.585, and adjusted P-value < 0.05.

D Dot plot for upregulated GSEA pathways using Hallmark gene sets. Implicated pathways are listed on the left with the corresponding gene counts and significance indicated by the size and color of dots.

E Heatmap of the top 18 QIAGEN Ingenuity Pathway Analysis z-scores sorted by the largest difference between infections of WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLP for the indicated pathways. Color indicates the z-score associated with the represented pathway.

F Graphical summary of observed host responses to WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLP infection in mouse macrophages.

Figure 5.

Mouse-Adapted 5xMG-trVLP Infection Induces Blunted Innate Immune Response in Mouse Macrophages.

A Multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot showing RNA-sequencing analysis of normalized gene expression in WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLP infected RAW264.7 cells. Dots indicate triplicate samples from each condition.

B DEGs in RAW264.7 cells infected with WT- or MA-5xMG-trVLPs meeting significance criteria. Red bars indicate upregulated genes, and blue bars indicate downregulated genes. Total DEG numbers are listed for each condition.

C Volcano plots displaying DEGs from WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLP infection. The axes indicate the fold change of gene expression and significance of up- and down-regulation. Red dots indicate upregulation, and blue dots indicate downregulation within the Gene Ontology of Biological Processes (GOBP) ‘Immune Effector’ gene set. Black dots indicate genes that are significant but unrelated to GOBP ‘Immune Effector’. Grey dots indicate genes that did not reach significance criteria. Vertical lines indicate log

2FC cutoffs, horizontal line indicates adjusted P-value cutoff. Plots were generated using the R package ggplot2 [

34] v3.5.1. DEG criteria for B-E = fold change relative to mock-infected controls > |1.5|, |log

2FC| > 0.585, and adjusted P-value < 0.05.

D Dot plot for upregulated GSEA pathways using Hallmark gene sets. Implicated pathways are listed on the left with the corresponding gene counts and significance indicated by the size and color of dots.

E Heatmap of the top 18 QIAGEN Ingenuity Pathway Analysis z-scores sorted by the largest difference between infections of WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLP for the indicated pathways. Color indicates the z-score associated with the represented pathway.

F Graphical summary of observed host responses to WT- and MA-5xMG-trVLP infection in mouse macrophages.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).