Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Caffeine is a weak, nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist. At low-to-moderate doses, caffeine has a stimulating effect, however, at higher doses, it can act as a depressant. It can act both as a neuroprotectant and a neurotoxin. In experimental Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), administration of this psychoactive drug has been associated with beneficial or detrimental effects, depending on the dose, model, and timing. In a healthy brain, it can boost alertness and promote wakefulness. On the other hand, its consumption during late adolescence and early adulthood disrupts normal pruning processes in the context of repetitive moderate TBI (mTBI), leading to changes in dendritic spine morphology resulting in neurological and behavioral impairments. Caffeine can potentially reduce TBI-associated intracranial pressure, oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, cytotoxic edema, inflammation, and apoptosis. It can enhance alertness and reduce mental fatigue, which is critical for the cognitive rehabilitation of TBI patients. It has positive effects on immune cells and recovery post-TBI. It can improve cognitive function by antagonizing adenosine receptors involved in controlling synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, and synapse toxicity. On the contrary, studies have also reported caffeine consumers had significantly higher somatic discomfort compared to non-consumers. Therefore, we bring forth this review with the objective of exploring various studies and thoroughly examining the positive and negative role of caffeine in TBI.

Keywords:

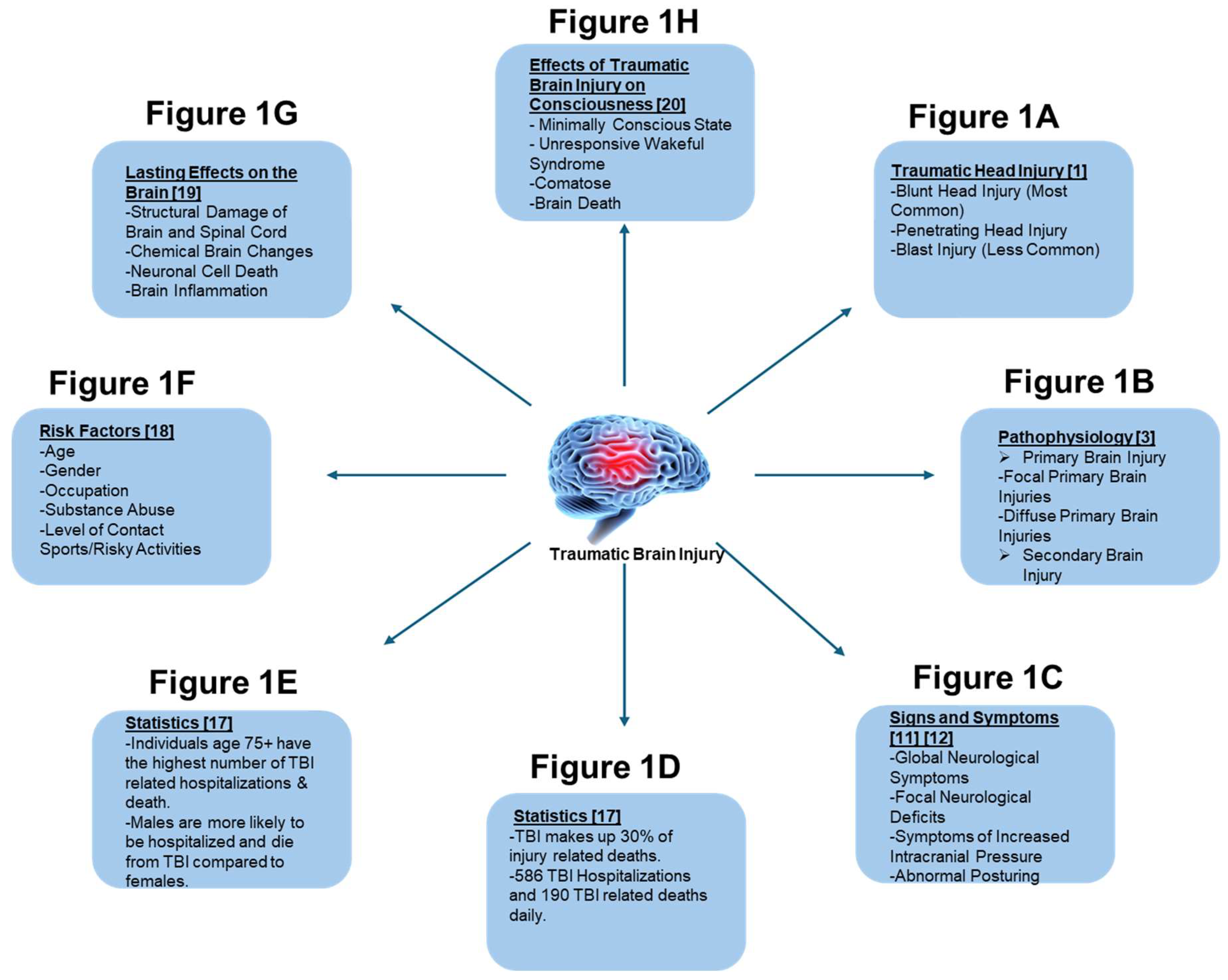

1. Introduction to Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

2. Introduction to Caffeine

2.1. Mechanism of Action

2.2. Route of Administration

2.3. Metabolism of Caffeine

2.4. Caffeine Toxicity

3. Numerous Effects of Caffeine in TBI

3.1. Caffeine as a Neuroprotectant

Caffeine as a Neurotoxin

3.2. Effects of Caffeine on a Healthy Brain and an Injured Brain

3.2.1. Healthy Brain

3.2.2. Injured Brain

3.3. Effect of Caffeine on Oxidative Stress and Mortality in TBI

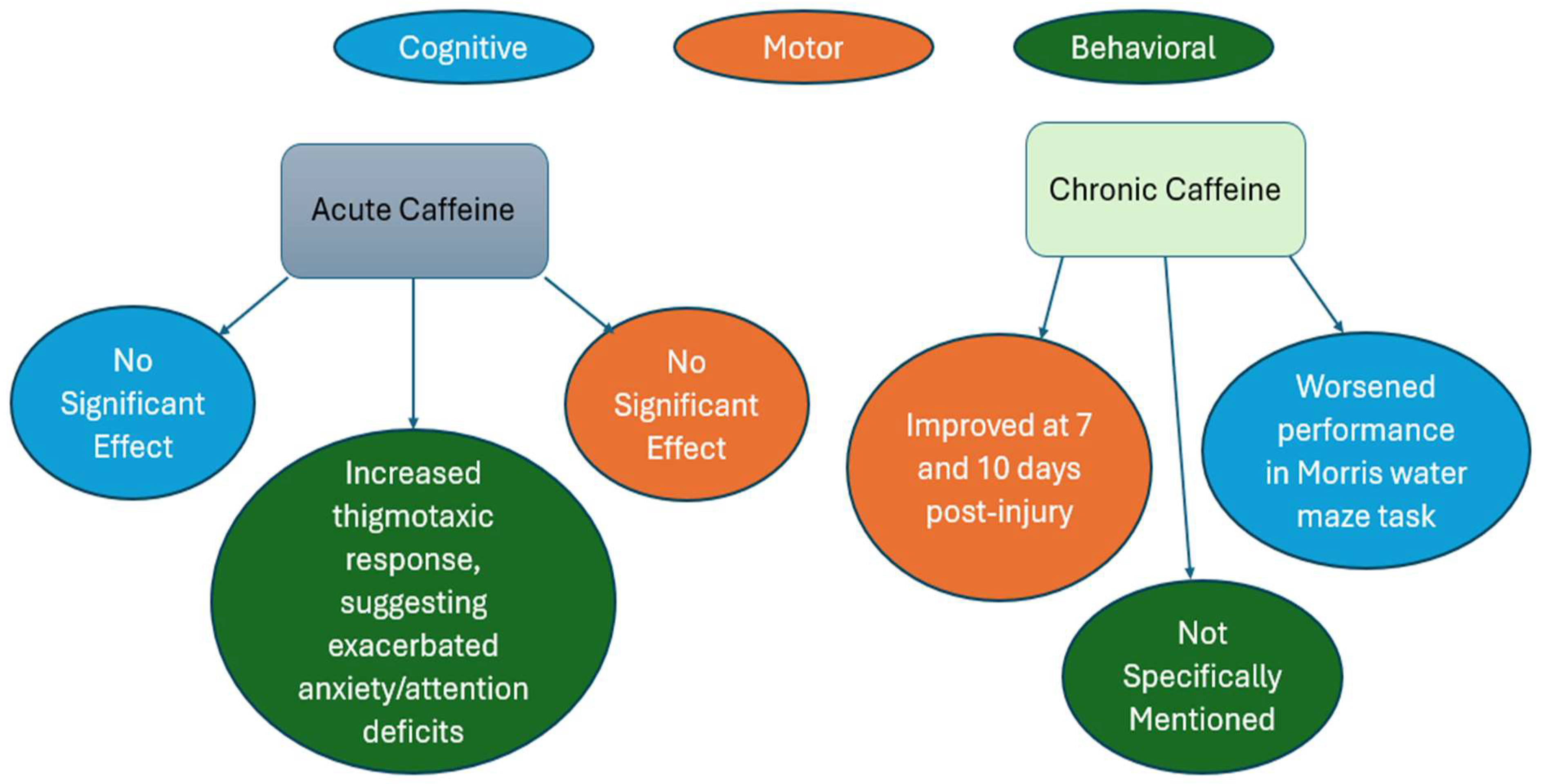

1.1. Effect of Caffeine on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Motor outcomes in TBI

3.4. Effect of Caffeine on the Immune System in TBI

| Study/Experiment | Details |

|---|---|

| TBI Mortality and Morbidity | High incidence of mortality and morbidity in TBI patients [39] |

| Caffeine Neuroprotective Effects | Caffeine has neuroprotective benefits in degenerative neurological disorders, antagonizes A2A receptors [45] |

| Serum Caffeine in TBI Patients | Caffeine levels analyzed within 4 hours of injury; and categorized into low, intermediate, and high levels; higher likelihood of 6-month recovery in low- and intermediate-caffeine groups [45] |

| Caffeine Antioxidative Properties | Caffeine protects neuronal cells from ROS damage, modulates inflammatory responses, lowers pro-inflammatory cytokine production [62,102] |

| Impact on Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes | Caffeine reduced PD1 expression on cytotoxic T lymphocytes, enhanced tumor targeting, decreased tumor size [102] |

| Effect on Natural Killer Cells | Caffeine enhanced NK cell activation post-exercise in cyclists, effective at low and high doses [103] |

| Developmental Exposure in Rats | Developmental caffeine exposure in rats altered spine density, impaired memory and cognitive function, different TBI recovery patterns [47] |

3.5. Effect of Caffeine on Various Physiological Proteins and Elements in TBI

3.6. Effect of Caffeine on Various Signaling Pathways, Genes, and Proteins in TBI

| Impact | Mechanism | Pathway | Genes/Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroprotection [114] | Reduces cell death and improves cognitive function post-injury [116] | Activates adenosine receptors, leading to downstream neurotransmitter release and neuroinflammatory pathways [115] | Modulates expression of genes involved in inflammation like TNF-α and IL-1β and neuronal survival like BDNF and NGF [117] |

| Anti-inflammatory [116] | Inhibits microglial activation and reduces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [117] |

Downregulates NF-κB signaling and modulates MAPK pathways [117] |

Alters expression of inflammatory mediators (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β) [114,117] |

| Improvement of Cognitive Function [119] | Enhances synaptic plasticity and neurotransmitter systems (e.g., acetylcholine) [119] |

Modulates cAMP/PKA signaling and calcium homeostasis [114,118] | Upregulates neurotrophic factors (e.g., BDNF, NGF) [114,118] |

3.7. How does Caffeine Interfere with Concussion and TBI Recovery?

| Type of Study | Caffeine Treatment | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Clinical Study | 0.25g/L | Chronic caffeine treatment alleviated cerebral injury at 24h post severe blast-induced TBI (bTBI)[41] |

| Pre-Clinical Study | 5mg/kg,15mg/kg and 50mg/kg | Chronic caffeine treatment represses the release of glutamate and inhibits cytokine expression after TBI[63] |

| Clinical Study | 0.01 - 10.00 μg/mL | A statistically significant association between a serum caffeine concentration of 0.01 to 1.66 μg/mL and good functional recovery at 6 months after injury compared with the no-caffeine group of patients with TBI with intracranial injury[45] |

| Pre-Clinical Study | Oral bolus dose of 25mg/kg | Regular caffeine consumption before a penetrating brain injury may moderately improve motor recovery but worsen the neurocognitive sequelae associated with a penetrating brain injury [81] |

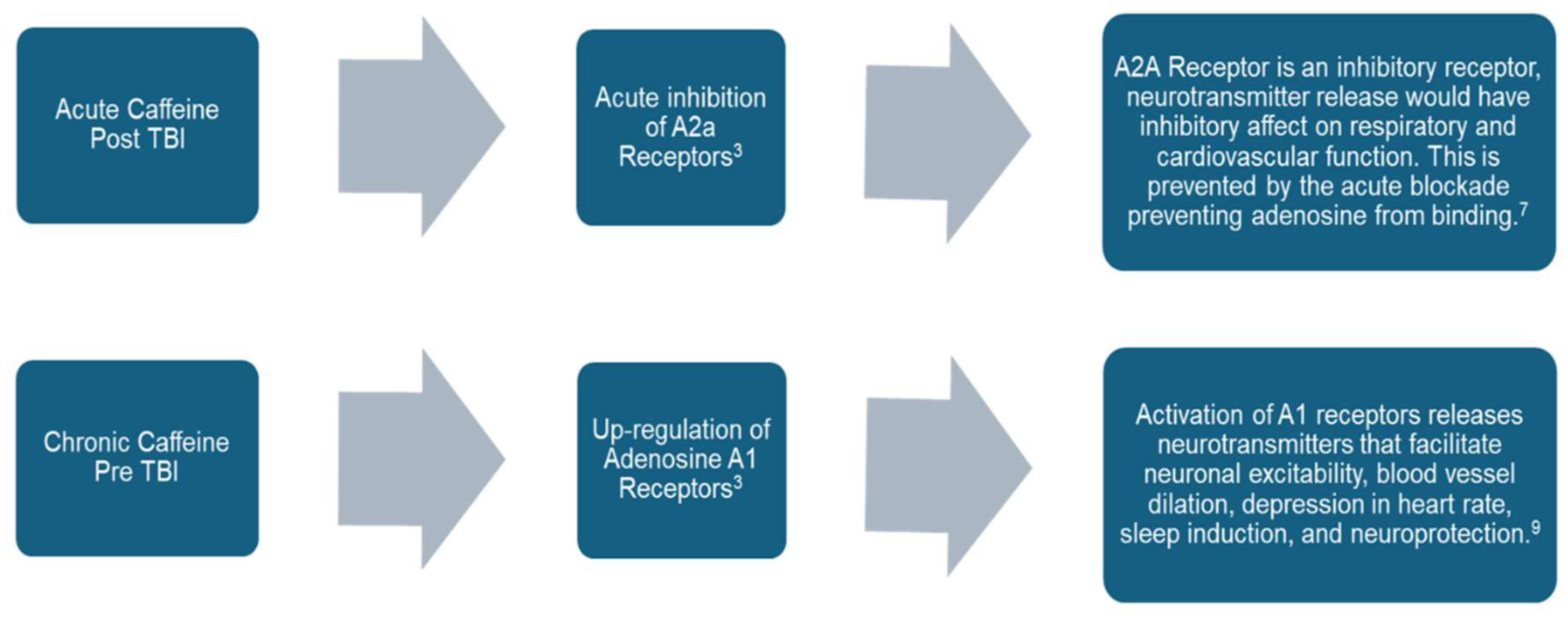

| Clinical Study | ≥1 μmol/L (194 ng/mL) | Caffeine may be neuroprotective by long-term upregulation of adenosine A1 receptors or acute inhibition of A2a receptors[36] |

| Pre-Clinical Study | 20mg/kg | Intracranial pressure decreased by 11% from baseline value which can improve clinical outcomes post-TBI[72] |

| Pre-Clinical Study | 25mg/kg | Chronic treatment initiated after TBI suggested improved motor function with a nonspecific adenosine receptor agonist, but a slight decrease in motor function after an A1 receptor antagonist [40] |

| Pre-Clinical Study | 36mg/kg | The interventions of caffeine, sleep deprivation, sleep aids, and sedation during the acute post-mTBI period each changed the subclinical characteristics of the brain after mTBI and altered the return toward normal function[59]. |

3.8. Effect of Preinjury and Post-Injury Exposure to Caffeine

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Menon, D. K.; Schwab, K.; Wright, D. W.; Maas, A. I. Position Statement: Definition of Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010, 91 (11), 1637–1640. [CrossRef]

- Accessed on December 6, 2024. CDC Surveillance Report of Traumatic Brain Injury-related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths—United States, 2014. URL: https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/data/tbi-edhd.html .

- Saatman, K. E.; Duhaime, A.-C.; Bullock, R.; Maas, A. I. R.; Valadka, A.; Manley, G. T. Classification of Traumatic Brain Injury for Targeted Therapies. J Neurotrauma 2008, 25 (7), 719–738. [CrossRef]

- Bhaisora, K.; Behari, S.; Godbole, C.; Phadke, R. Traumatic Aneurysms of the Intracranial and Cervical Vessels: A Review. Neurol India 2016, 64 (7), 14. [CrossRef]

- Gerard, C.; Busl, K. M. Treatment of Acute Subdural Hematoma. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2014, 16 (1), 275. [CrossRef]

- Ron Walls, M. R. H. M. M. G.-H. M. F. F. T. B. E. M. F. F. F. and S. R. W. M. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, ISBN: 9780323757898 , 10th Edition.; Page count 2768, 2022; Vol. II.

- Joseph Loscalzo, A. F. D. K. S. H. D. L. J. L. J. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 21st ed.; McGraw-Hill Education; 2022, 2022.

- Neurology and Clinical Neuroscience, 1626 Pages; Anthony Henry Vernon Schapira, Edward Byrne, Eds.; Mosby Elsevier, 2007 ISBN: 0323033547, 9780323033541.

- Mckee, A. C.; Daneshvar, D. H. The Neuropathology of Traumatic Brain Injury; 2015; pp 45–66. [CrossRef]

- Carney, N.; Ghajar, J.; Jagoda, A.; Bedrick, S.; Davis-O’Reilly, C.; du Coudray, H.; Hack, D.; Helfand, N.; Huddleston, A.; Nettleton, T.; Riggio, S. Concussion Guidelines Step 1. Neurosurgery 2014, 75 (Supplement 1), S3–S15. [CrossRef]

- Rincon, S.; Gupta, R.; Ptak, T. Imaging of Head Trauma. Handb Clin Neurol 2016, 135, 447–477. [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. T.; Giza, C. C. Traumatic Brain Injury in Children. In Swaiman’s Pediatric Neurology; Elsevier, 2012; pp 1087–1125. [CrossRef]

- Marmarou, A. A Review of Progress in Understanding the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Brain Edema. Neurosurg Focus 2007, 22 (5), E1. [CrossRef]

- Drs. Richard G. Ellenbogen, L. N. S. and N. K. Principles of Neurological Surgery, 4th Edition.; Imprint: Elsevier. eBook ISBN: 9780323461276; Hardback ISBN: 9780323431408, 2017.

- Flood, L. HEAD AND NECK TRAUMA: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH A Ernst, M Herzog, R Seidl Georg Thieme Verlag, 2006 ISBN 3 13 140001 3 Pp 222 Price Euro (D) 99.95 CHF 160.00 Before Receipt. J Laryngol Otol 2007, 121 (4), 408–408. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics: Mortality Data on CDC WONDER. Available online; accessed on December 6, 2024.

- Lafta, G.; Sbahi, H. Factors Associated with the Severity of Traumatic Brain Injury. Med Pharm Rep 2023, 96 (1), 58–64. [CrossRef]

- Bramlett, H. M.; Dietrich, W. D. Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury: Current Status of Potential Mechanisms of Injury and Neurological Outcomes. J Neurotrauma 2015, 32 (23), 1834–1848. [CrossRef]

- https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/traumatic-brain-injury-tbi. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). Available online; accessed on December 6, 2024.

- Teasdale, G.; Jennett, B. ASSESSMENT OF COMA AND IMPAIRED CONSCIOUSNESS. The Lancet 1974, 304 (7872), 81–84. [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, G.; Maas, A.; Lecky, F.; Manley, G.; Stocchetti, N.; Murray, G. The Glasgow Coma Scale at 40 Years: Standing the Test of Time. Lancet Neurol 2014, 13 (8), 844–854. [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, S. M.; Jacinto, T. A.; Gonçalves, A. C.; Gaspar, D.; Silva, L. R. Overview of Caffeine Effects on Human Health and Emerging Delivery Strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16 (8), 1067. [CrossRef]

- Justin Evans; John R. Richards; Amanda S. Battisti. Caffeine. In In: StatPearls [Internet] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519490/; Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2024.

- Fiani, B.; Zhu, L.; Musch, B. L.; Briceno, S.; Andel, R.; Sadeq, N.; Ansari, A. Z. The Neurophysiology of Caffeine as a Central Nervous System Stimulant and the Resultant Effects on Cognitive Function. Cureus 2021. [CrossRef]

- Burdan, F. Caffeine in Coffee. In Coffee in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier, 2015; pp 201–207. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V. S.; Shiva, S.; Manikantan, S.; Ramakrishna, S. Pharmacology of Caffeine and Its Effects on the Human Body. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry Reports 2024, 10, 100138. [CrossRef]

- Nowaczewska, M.; Wiciński, M.; Kaźmierczak, W. The Ambiguous Role of Caffeine in Migraine Headache: From Trigger to Treatment. Nutrients 2020, 12 (8), 2259. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V. K.; Sharma, A.; Verma, K. K.; Gaur, P. K.; Kaushik, R.; Abdali, B. A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW ON PHARMACOLOGICAL POTENTIALS OF CAFFEINE. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 2023, 6 (3), 16–26. [CrossRef]

- Grzegorzewski, J.; Bartsch, F.; Köller, A.; König, M. Pharmacokinetics of Caffeine: A Systematic Analysis of Reported Data for Application in Metabolic Phenotyping and Liver Function Testing. Front Pharmacol 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Belayneh, A.; Molla, F. The Effect of Coffee on Pharmacokinetic Properties of Drugs : A Review. Biomed Res Int 2020, 2020, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, M.; Calvello, R.; Porro, C.; Messina, G.; Cianciulli, A.; Panaro, M. A. Neurodegenerative Diseases: Can Caffeine Be a Powerful Ally to Weaken Neuroinflammation? Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23 (21), 12958. [CrossRef]

- Kolahdouzan, M.; Hamadeh, M. J. The Neuroprotective Effects of Caffeine in Neurodegenerative Diseases. CNS Neurosci Ther 2017, 23 (4), 272–290. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury: Nanotherapeutics. J Clin Haematol 2024, 5 (1), 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.-L.; Yang, N.; Chen, X.; Tian, H.-K.; Zhao, Z.-A.; Zhang, X.-Z.; Liu, D.; Li, P.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Z.-G.; Chen, J.-F.; Zhou, Y.-G. Caffeine Attenuates Brain Injury but Increases Mortality Induced by High-Intensity Blast Wave Exposure. Toxicol Lett 2019, 301, 90–97. [CrossRef]

- Al Moutaery, K.; Al Deeb, S.; Khan, H. A.; Tariq, M. Caffeine Impairs Short-Term Neurological Outcome after Concussive Head Injury in Rats. Neurosurgery 2003, 53 (3), 704–712. [CrossRef]

- Sachse, K. T.; Jackson, E. K.; Wisniewski, S. R.; Gillespie, D. G.; Puccio, A. M.; Clark, R. S.; Dixon, C. E.; Kochanek, P. M. Increases in Cerebrospinal Fluid Caffeine Concentration Are Associated with Favorable Outcome after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Humans. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2008, 28 (2), 395–401. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-L.; Qu, W.-M.; Eguchi, N.; Chen, J.-F.; Schwarzschild, M. A.; Fredholm, B. B.; Urade, Y.; Hayaishi, O. Adenosine A2A, but Not A1, Receptors Mediate the Arousal Effect of Caffeine. Nat Neurosci 2005, 8 (7), 858–859. [CrossRef]

- Moreira-de-Sá, A.; Lourenço, V. S.; Canas, P. M.; Cunha, R. A. Adenosine A2A Receptors as Biomarkers of Brain Diseases. Front Neurosci 2021, 15. [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, T. A.; Lytle, N. K.; Szybala, C.; Boison, D. Caffeine Prevents Acute Mortality after TBI in Rats without Increased Morbidity. Exp Neurol 2012, 234 (1). [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, T. A.; Lytle, N. K.; Gebril, H. M.; Boison, D. Effects of Preinjury and Postinjury Exposure to Caffeine in a Rat Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. J Caffeine Adenosine Res 2020, 10 (1), 12–24. [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.-L.; Yang, N.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Z.-A.; Zhang, X.-Z.; Chen, X.-Y.; Li, P.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Y.-G. Chronic Caffeine Exposure Attenuates Blast-Induced Memory Deficit in Mice. Chinese Journal of Traumatology 2015, 18 (4), 204–211. [CrossRef]

- Sebastião, A. M.; Ribeiro, J. A. Adenosine Receptors and the Central Nervous System; 2009; pp 471–534. [CrossRef]

- Dash, P. K.; Moore, A. N.; Moody, M. R.; Treadwell, R.; Felix, J. L.; Clifton, G. L. Post-Trauma Administration of Caffeine Plus Ethanol Reduces Contusion Volume and Improves Working Memory in Rats. J Neurotrauma 2004, 21 (11), 1573–1583. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadipour, M.; Ahmadinejad, M. Effects of Caffeine Administration on GCS and GOSE in Children and Adolescent Patients with Moderate Brain Trauma. European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine 2021, 08 (1).

- Yoon, H.; Ro, Y. S.; Jung, E.; Moon, S. B.; Park, G. J.; Lee, S. G. W.; Shin, S. Do. Serum Caffeine Concentration at the Time of Traumatic Brain Injury and Its Long-Term Clinical Outcomes. J Neurotrauma 2023, 40 (21–22), 2386–2395. [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, W. A.; Saykally, J. N.; Mervis, R. F.; Lin, X.; Cao, C.; Citron, B. A. Behavior, Protein, and Dendritic Changes after Model Traumatic Brain Injury and Treatment with Nanocoffee Particles. BMC Neurosci 2019, 20 (1), 44. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.; Yamakawa, G. R.; Salberg, S.; Wang, M.; Kolb, B.; Mychasiuk, R. Caffeine Consumption during Development Alters Spine Density and Recovery from Repetitive Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Young Adult Rats. Synapse 2020, 74 (4). [CrossRef]

- Cappelletti, S.; Daria, P.; Sani, G.; Aromatario, M. Caffeine: Cognitive and Physical Performance Enhancer or Psychoactive Drug? Curr Neuropharmacol 2015, 13 (1), 71–88. [CrossRef]

- Nehlig, A. Is Caffeine a Cognitive Enhancer? In Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease; 2010; Vol. 20. [CrossRef]

- Fredholm, B. B.; Bättig, K.; Holmén, J.; Nehlig, A.; Zvartau, E. E. Actions of Caffeine in the Brain with Special Reference to Factors That Contribute to Its Widespread Use. Pharmacological Reviews. 1999.

- Yang, J.-N.; Chen, J.-F.; Fredholm, B. B. Physiological Roles of A 1 and A 2A Adenosine Receptors in Regulating Heart Rate, Body Temperature, and Locomotion as Revealed Using Knockout Mice and Caffeine. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2009, 296 (4), H1141–H1149. [CrossRef]

- Powers, M. E. Acute Stimulant Ingestion and Neurocognitive Performance in Healthy Participants. J Athl Train 2015, 50 (5). [CrossRef]

- Rusted, J. Caffeine and Cognitive Performance: Effects on Mood or Mental Processing? In Caffeine and Behavior: Current Views & Research Trends: Current Views and Research Trends; 2020.

- Smith, J. E.; Lawrence, A. D.; Diukova, A.; Wise, R. G.; Rogers, P. J. Storm in a Coffee Cup: Caffeine Modifies Brain Activation to Social Signals of Threat. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2012, 7 (7), 831–840. [CrossRef]

- Porkka-Heiskanen, T. Methylxanthines and Sleep. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, N.; Ghotbi, R.; Jankovic, S.; Aklillu, E. Induction of CYP1A2 by Heavy Coffee Consumption Is Associated with the CYP1A2 -163C>A Polymorphism. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2010, 66 (7). [CrossRef]

- Rétey, J. V.; Adam, M.; Khatami, R.; Luhmann, U. F. O.; Jung, H. H.; Berger, W.; Landolt, H. P. A Genetic Variation in the Adenosine A2A Receptor Gene (ADORA2A) Contributes to Individual Sensitivity to Caffeine Effects on Sleep. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007, 81 (5). [CrossRef]

- Coris, E. E.; Moran, B.; Sneed, K.; Del Rossi, G.; Bindas, B.; Mehta, S.; Narducci, D. Stimulant Therapy Utilization for Neurocognitive Deficits in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach 2022, 14 (4), 538–548. [CrossRef]

- Everson, C. A.; Szabo, A.; Plyer, C.; Hammeke, T. A.; Stemper, B. D.; Budde, M. D. Sleep Loss, Caffeine, Sleep Aids and Sedation Modify Brain Abnormalities of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Exp Neurol 2024, 372, 114620. [CrossRef]

- Temple, J. L. Caffeine Use in Children: What We Know, What We Have Left to Learn, and Why We Should Worry. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2009, 33 (6), 793–806. [CrossRef]

- Landolt, H.-P.; Rétey, J. V; Tönz, K.; Gottselig, J. M.; Khatami, R.; Buckelmüller, I.; Achermann, P. Caffeine Attenuates Waking and Sleep Electroencephalographic Markers of Sleep Homeostasis in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29 (10), 1933–1939. [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, G. R.; Lengkeek, C.; Salberg, S.; Spanswick, S. C.; Mychasiuk, R. Behavioral and Pathophysiological Outcomes Associated with Caffeine Consumption and Repetitive Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (RmTBI) in Adolescent Rats. PLoS One 2017, 12 (11), e0187218. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Dai, S.; An, J.; Li, P.; Chen, X.; Xiong, R.; Liu, P.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, M.; Liu, X.; Zhu, P.; Chen, J.-F.; Zhou, Y. Chronic but Not Acute Treatment with Caffeine Attenuates Traumatic Brain Injury in the Mouse Cortical Impact Model. Neuroscience 2008, 151 (4), 1198–1207. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B. S.; Gupta, U. Caffeine and Behavior: Current Views and Research Trends; 2020.

- Kuzmin, A.; Johansson, B.; Gimenez, L.; Ögren, S.-O.; Fredholm, B. B. Combination of Adenosine A1 and A2A Receptor Blocking Agents Induces Caffeine-like Locomotor Stimulation in Mice. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 16 (2), 129–136. [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, T. Adenosine Neuromodulation and Traumatic Brain Injury. Curr Neuropharmacol 2009, 7 (3), 228–237. [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, P. M.; Verrier, J. D.; Wagner, A. K.; Jackson, E. K. The Many Roles of Adenosine in Traumatic Brain Injury. In Adenosine; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013; pp 307–322. [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.-S.; Zhou, Y.-G. Adenosine 2A Receptor: A Crucial Neuromodulator with Bidirectional Effect in Neuroinflammation and Brain Injury. revneuro 2011, 22 (2), 231–239. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Dai, S.; An, J.; Xiong, R.; Li, P.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, P.; Wang, H.; Zhu, P.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y. Genetic Inactivation of Adenosine A2A Receptors Attenuates Acute Traumatic Brain Injury in the Mouse Cortical Impact Model. Exp Neurol 2009, 215 (1), 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-F.; Xu, K.; Petzer, J. P.; Staal, R.; Xu, Y.-H.; Beilstein, M.; Sonsalla, P. K.; Castagnoli, K.; Castagnoli, N.; Schwarzschild, M. A. Neuroprotection by Caffeine and A 2A Adenosine Receptor Inactivation in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease. The Journal of Neuroscience 2001, 21 (10), RC143–RC143. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-F.; Chern, Y. Impacts of Methylxanthines and Adenosine Receptors on Neurodegeneration: Human and Experimental Studies; 2011; pp 267–310. [CrossRef]

- Bláha, M.; Vajnerová, O.; Bednár, M.; Vajner, L.; Tichý, M. Traumatic Brain Injuries--Effects of Alcohol and Caffeine on Intracranial Pressure and Cerebral Blood Flow. Rozhl Chir 2009, 88 (11).

- Bona, E.; Ådén, U.; Gilland, E.; Fredholm, B. B.; Hagberg, H. Neonatal Cerebral Hypoxia-Ischemia: The Effect of Adenosine Receptor Antagonists. Neuropharmacology 1997, 36 (9), 1327–1338. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Gonzalez, F.; McQuillen, P. S. Caffeine Restores Background EEG Activity Independent of Infarct Reduction after Neonatal Hypoxic Ischemic Brain Injury. Dev Neurosci 2020, 42 (1), 72–82. [CrossRef]

- Washington, C. ; J. E. ; J. K. ; V. V. ; L. Z. ; J. L. ; C. R. ; D. C. E. ; K. P. Chronic Caffeine Administration Reduces Hippocampal Neuronal Cell Death after Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice. J Neurotrauma. J. Neurotrauma 2005, 22 1256–1256.

- Barrett, P. J.; Casey, E. K.; Sisung, C.; Gaebler-Spira, D. Caffeine as a Neurostimulant: Two Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury Cases. J Pediatr Rehabil Med 2010, 3 (3), 229–232. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-A.; Zhao, Y.; Ning, Y.-L.; Yang, N.; Peng, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, X.-Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Bai, W.; Chen, J.-F.; Zhou, Y.-G. Adenosine A2A Receptor Inactivation Alleviates Early-Onset Cognitive Dysfunction after Traumatic Brain Injury Involving an Inhibition of Tau Hyperphosphorylation. Transl Psychiatry 2017, 7 (5), e1123–e1123. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Y.-G.; Chen, J.-F. Targeting the Adenosine A2A Receptor for Neuroprotection and Cognitive Improvement in Traumatic Brain Injury and Parkinson’s Disease. Chinese Journal of Traumatology 2024, 27 (3), 125–133. [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, P. M.; Vagni, V. A.; Janesko, K. L.; Washington, C. B.; Crumrine, P. K.; Garman, R. H.; Jenkins, L. W.; Clark, R. S.; Homanics, G. E.; Dixon, C. E.; Schnermann, J.; Jackson, E. K. Adenosine A1 Receptor Knockout Mice Develop Lethal Status Epilepticus after Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2006, 26 (4), 565–575. [CrossRef]

- Haselkorn, M. L.; Shellington, D. K.; Jackson, E. K.; Vagni, V. A.; Janesko-Feldman, K.; Dubey, R. K.; Gillespie, D. G.; Cheng, D.; Bell, M. J.; Jenkins, L. W.; Homanics, G. E.; Schnermann, J.; Kochanek, P. M. Adenosine A 1 Receptor Activation as a Brake on the Microglial Response after Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice. J Neurotrauma 2010, 27 (5), 901–910. [CrossRef]

- Sanjakdar, S. S.; Flerlage, W. J.; Kang, H. S.; Napier, D. A.; Dougherty, J. R.; Mountney, A.; Gilsdorf, J. S.; Shear, D. A. Differential Effects of Caffeine on Motor and Cognitive Outcomes of Penetrating Ballistic-Like Brain Injury. Mil Med 2019, 184 (Supplement_1), 291–300. [CrossRef]

- Sabir, H.; Maes, E.; Zweyer, M.; Schleehuber, Y.; Imam, F. B.; Silverman, J.; White, Y.; Pang, R.; Pasca, A. M.; Robertson, N. J.; Maltepe, E.; Bernis, M. E. Comparing the Efficacy in Reducing Brain Injury of Different Neuroprotective Agents Following Neonatal Hypoxia–Ischemia in Newborn Rats: A Multi-Drug Randomized Controlled Screening Trial. Sci Rep 2023, 13 (1), 9467. [CrossRef]

- Rincon, F.; Ghosh, S.; Dey, S.; Maltenfort, M.; Vibbert, M.; Urtecho, J.; McBride, W.; Moussouttas, M.; Bell, R.; Ratliff, J. K.; Jallo, J. Impact of Acute Lung Injury and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome After Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States. Neurosurgery 2012, 71 (4), 795–803. [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Li, P.; Ning, Y.-L.; Jiang, Y.-L.; Yang, N.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.-G. Reduction in Blood Glutamate Levels Combined With the Genetic Inactivation of A2AR Significantly Alleviate Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Acute Lung Injury. Shock 2019, 51 (4), 502–510. [CrossRef]

- Strong, R.; Grotta, J. C.; Aronowski, J. Combination of Low Dose Ethanol and Caffeine Protects Brain from Damage Produced by Focal Ischemia in Rats. Neuropharmacology 2000, 39 (3), 515–522. [CrossRef]

- Piriyawat, P.; Labiche, L. A.; Burgin, W. S.; Aronowski, J. A.; Grotta, J. C. Pilot Dose-Escalation Study of Caffeine Plus Ethanol (Caffeinol) in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2003, 34 (5), 1242–1245. [CrossRef]

- KONTOS, H. A.; POVLISHOCK, J. T. Oxygen Radicals in Brain Injury. Central Nervous System Trauma 1986, 3 (4), 257–263. [CrossRef]

- Clark, R. S. B.; Carcillo, J. A.; Kochanek, P. M.; Obrist, W. D.; Jackson, E. K.; Mi, Z.; Wisneiwski, S. R.; Bell, M. J.; Marion, D. W. Cerebrospinal Fluid Adenosine Concentration and Uncoupling of Cerebral Blood Flow and Oxidative Metabolism after Severe Head Injury in Humans. Neurosurgery 1997, 41 (6), 1284–1292. [CrossRef]

- Gerbatin, R. R.; Dobrachinski, F.; Cassol, G.; Soares, F. A. A.; Royes, L. F. F. A1 Rather than A2A Adenosine Receptor as a Possible Target of Guanosine Effects on Mitochondrial Dysfunction Following Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. Neurosci Lett 2019, 704, 141–144. [CrossRef]

- Almajano, M. P.; Vila, I.; Gines, S. Neuroprotective Effects of White Tea Against Oxidative Stress-Induced Toxicity in Striatal Cells. Neurotox Res 2011, 20 (4), 372–378. [CrossRef]

- Caravan, I.; Sevastre Berghian, A.; Moldovan, R.; Decea, N.; Orasan, R.; Filip, G. A. Modulatory Effects of Caffeine on Oxidative Stress and Anxiety-like Behavior in Ovariectomized Rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2016, 94 (9), 961–972. [CrossRef]

- Prasanthi, J. R. P.; Dasari, B.; Marwarha, G.; Larson, T.; Chen, X.; Geiger, J. D.; Ghribi, O. Caffeine Protects against Oxidative Stress and Alzheimer’s Disease-like Pathology in Rabbit Hippocampus Induced by Cholesterol-Enriched Diet. Free Radic Biol Med 2010, 49 (7), 1212–1220. [CrossRef]

- Fredholm, B. B.; Chen, J.-F.; Masino, S. A.; Vaugeois, J.-M. ACTIONS OF ADENOSINE AT ITS RECEPTORS IN THE CNS: Insights from Knockouts and Drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2005, 45 (1), 385–412. [CrossRef]

- &NA; Caffeine for the Sustainment of Mental Task Performance: Formulations for Military Operations. Nutr Today 2002, 37 (1). [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S. Mechanisms of the Psychostimulant Effects of Caffeine: Implications for Substance Use Disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016, 233 (10), 1963–1979. [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S.; Ciruela, F.; Quiroz, C.; Luján, R.; Popoli, P.; Cunha, R. A.; Agnati, L. F.; Fuxe, K.; Woods, A. S.; Lluis, C.; Franco, R. Adenosine Receptor Heteromers and Their Integrative Role in Striatal Function. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Yacoubi, M. El; Ledent, C.; Ménard, J.; Parmentier, M.; Costentin, J.; Vaugeois, J. The Stimulant Effects of Caffeine on Locomotor Behaviour in Mice Are Mediated through Its Blockade of Adenosine A 2A Receptors. Br J Pharmacol 2000, 129 (7), 1465–1473. [CrossRef]

- Wilk, M.; Krzysztofik, M.; Filip, A.; Zajac, A.; Del Coso, J. The Effects of High Doses of Caffeine on Maximal Strength and Muscular Endurance in Athletes Habituated to Caffeine. Nutrients 2019, 11 (8), 1912. [CrossRef]

- Olopade, F. E.; Femi-Akinlosotu, O. M.; Adekanmbi, A. J.; Ighogboja, O. O.; Shokunbi, M. T. Chronic Caffeine Ingestion Improves Motor Function and Increases Dendritic Length and Arborization in the Motor Cortex, Striatum, and Cerebellum. J Caffeine Adenosine Res 2021, 11 (1), 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Vynorius, K. C.; Paquin, A. M.; Seichepine, D. R. Lifetime Multiple Mild Traumatic Brain Injuries Are Associated with Cognitive and Mood Symptoms in Young Healthy College Students. Front Neurol 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Van Batenburg-Eddes, T.; Lee, N. C.; Weeda, W. D.; Krabbendam, L.; Huizinga, M. The Potential Adverse Effect of Energy Drinks on Executive Functions in Early Adolescence. Front Psychol 2014, 5. [CrossRef]

- Venkata Charan Tej, G. N.; Neogi, K.; Verma, S. S.; Chandra Gupta, S.; Nayak, P. K. Caffeine-Enhanced Anti-Tumor Immune Response through Decreased Expression of PD1 on Infiltrated Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes. Eur J Pharmacol 2019, 859. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D. K.; Bishop, N. C. Effect of a High and Low Dose of Caffeine on Antigen-Stimulated Activation of Human Natural Killer Cells After Prolonged Cycling. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2011, 21 (2), 155–165. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.; Abtahi Froushani, S. M.; Delirezh, N.; Mostafaei, A. Caffeine Alters the Effects of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Neutrophils. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2018, 27 (4), 463–468. [CrossRef]

- Nehlig, A. Are We Dependent upon Coffee and Caffeine? A Review on Human and Animal Data. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1999, 23 (4), 563–576. [CrossRef]

- Ofluoglu, E.; Pasaoglu, H.; Pasaoglu, A. The Effects of Caffeine on L-Arginine Metabolism in the Brain of Rats. Neurochem Res 2009, 34 (3), 395–399. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.; Shakkour, Z.; Tabet, M.; Abdelhady, S.; Kobaisi, A.; Abedi, R.; Nasrallah, L.; Pintus, G.; Al-Dhaheri, Y.; Mondello, S.; El-Khoury, R.; Eid, A. H.; Kobeissy, F.; Salameh, J. Traumatic Brain Injury: Oxidative Stress and Novel Anti-Oxidants Such as Mitoquinone and Edaravone. Antioxidants 2020, 9 (10), 943. [CrossRef]

- Shirley, D. G.; Walter, S. J.; Noormohamed, F. H. Natriuretic Effect of Caffeine: Assessment of Segmental Sodium Reabsorption in Humans. Clin Sci 2002, 103 (5). [CrossRef]

- Seal, A. D.; Bardis, C. N.; Gavrieli, A.; Grigorakis, P.; Adams, J. D.; Arnaoutis, G.; Yannakoulia, M.; Kavouras, S. A. Coffee with High but Not Low Caffeine Content Augments Fluid and Electrolyte Excretion at Rest. Front Nutr 2017, 4. [CrossRef]

- Pin-on, P.; Saringkarinkul, A.; Punjasawadwong, Y.; Kacha, S.; Wilairat, D. Serum Electrolyte Imbalance and Prognostic Factors of Postoperative Death in Adult Traumatic Brain Injury Patients. Medicine 2018, 97 (45), e13081. [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. T.; Rzigalinski, B. A.; Ellis, E. F. Calcium Responses to Caffeine and Muscarinic Receptor Agonists Are Altered in Traumatically Injured Neurons. J Neurotrauma 2002, 19 (11), 1433–1443. [CrossRef]

- Buccilli, B.; Alan, A.; Baha’, A.; Shahzad, A.; Almealawy, Y.; Chisvo, N. S.; Ennabe, M.; Weinand, M. Neuroprotection Strategies in Traumatic Brain Injury: Studying the Effectiveness of Different Clinical Approaches. Surg Neurol Int 2024, 15, 29. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, S.; Schnermann, J.; Noorbakhsh, F.; Henry, S.; Yong, V. W.; Winston, B. W.; Warren, K.; Power, C. A1 Adenosine Receptor Upregulation and Activation Attenuates Neuroinflammation and Demyelination in a Model of Multiple Sclerosis. The Journal of Neuroscience 2004, 24 (6), 1521–1529. [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, A. M.; Coppi, E.; Spalluto, G.; Corradetti, R.; Pedata, F. A 3 Adenosine Receptor Antagonists Delay Irreversible Synaptic Failure Caused by Oxygen and Glucose Deprivation in the Rat CA1 Hippocampus in Vitro. Br J Pharmacol 2006, 147 (5), 524–532. [CrossRef]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Villanueva-García, D.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Lezama-García, K.; Miranda-Cortés, A.; Martínez-Burnes, J. Cardiorespiratory and Neuroprotective Effects of Caffeine in Neonate Animal Models. Animals 2023, 13 (11), 1769. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Pozada, E. E.; Ramos-Tovar, E.; Rodriguez-Callejas, J. D.; Cardoso-Lezama, I.; Galindo-Gómez, S.; Talamás-Lara, D.; Vásquez-Garzón, V. R.; Arellanes-Robledo, J.; Tsutsumi, V.; Villa-Treviño, S.; Muriel, P. Caffeine Inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Downregulating TLR4/MAPK/NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway in an Experimental NASH Model. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23 (17), 9954. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Koike, T. Caffeine Promotes Survival of Cultured Sympathetic Neurons Deprived of Nerve Growth Factor through a CAMP-Dependent Mechanism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1992, 1175 (1), 114–122. [CrossRef]

- HAN, K.; JIA, N.; LI, J.; YANG, L.; MIN, L.-Q. Chronic Caffeine Treatment Reverses Memory Impairment and the Expression of Brain BNDF and TrkB in the PS1/APP Double Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Med Rep 2013, 8 (3), 737–740. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J. P.; Pliássova, A.; Cunha, R. A. The Physiological Effects of Caffeine on Synaptic Transmission and Plasticity in the Mouse Hippocampus Selectively Depend on Adenosine A1 and A2A Receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 2019, 166, 313–321. [CrossRef]

- Schapira, A. H. V.; Bezard, E.; Brotchie, J.; Calon, F.; Collingridge, G. L.; Ferger, B.; Hengerer, B.; Hirsch, E.; Jenner, P.; Novère, N. Le; Obeso, J. A.; Schwarzschild, M. A.; Spampinato, U.; Davidai, G. Novel Pharmacological Targets for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006, 5 (10), 845–854. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on the Review of the Department of Veterans Affairs Examinations for Traumatic Brain Injury. Evaluation of the Disability Determination Process for Traumatic Brain Injury in Veterans. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2019 Apr 10. B, Definitions of Traumatic Brain Injury. Nd Medicine Division; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542588/.

- Johnson, J. M. ; E. J. M. ; M. R. D. Effects of Caffeine on Measures of Clinical Outcome and Recovery Following Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Adolescents. Master’s Thesis, Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/7497., University of South Carolina, 2023.

- Sun, D. ; D. T. E. ; P. Y. ; K. K. ; C. H. T. ; L. A. M. ; J. L. S. ; C. J. D. Survival and Injury Outcome After TBI: Influence of Pre- and Post-Exposure to Caffeine. Neuroscience 2012, 47–58.

| Reference number | Study Model | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| [64] | N/A | Caffeine acts as an adenosine antagonist, specifically the A1 and A2A receptors. |

| [65] | N/A | Adenosine receptors are of interest in TBI because they are involved in various brain injury pathways. |

| [66] | Rodent | Adenosine may have a protective role in recovery of TBI |

| [67] | Rodent | Caffeine may have a neuroprotective effect on Parkinson’s disease pathways. |

| [68] | Mixed | Caffeine may have a neuroprotective effect on neurodegenerative diseases |

| [69] | Rodent | Chronic caffeine treatment rather than acute caffeine treatment showed better recovery from TBI in mice models. |

| [70] | Mixed | Review article finding combined evidence of potential benefit of treating Parkinson’s Disease and TBI through targeting the adenosine2A receptor. |

| [71] | Rodent | Pretreatment of rats with caffeine before TBI showed an increase in mortality |

| [63] | Rodent | Chronic caffeine use may have some protective benefits in blast-induced TBI however chronic and acute caffeine use both increased mortality. |

| [72] | Rodent | Caffeine injection given immediately after TBI reduced TBI-induced mortality in rat models. |

| [73] | Rodent | An acute dose of caffeine given 10 seconds after TBI decreased mortality and morbidity in mice models. |

| [74] | Humans | An increase in CSF concentration of caffeine in patients with TBI was associated with more favorable outcomes. |

| [74] | Human | Patients with TBI who had a serum caffeine concentration between 0.01 to 1.66 μg/mL had better recovery after 6 months of injury compared to the no caffeine group. |

| [75] | Cats | One of the earliest studies that examined the pathophysiology of oxygen radicals in TBI |

| [76] | Humans | Found potential benefits of adenosine on cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism in patients with severe head injury |

| [44] | Rodent | Caffeine in female rats has been shown to decrease oxidative stress and specifically decrease lipid peroxidation in the hippocampus. |

| [77] | Rabbits | Caffeine was seen to protect against oxidative stress and Alzheimer’s dementia-like pathology in rabbit models. |

| [62] | Rodent | Positive neuronal changes were seen when treating mice with nano coffee injections after a TBI. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).