Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| Salt | %RH | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LiCl | 11 | 1.25 | 1.2 |

| CH3COOK | 23 | 1.70 | 1.73 |

| MgCl2 | 33 | 2.10 | 2.1 |

| K2CO3 | 43 | 2.40 | 2.78 |

| NH4NO3 | 64 | 3.33 | 3.41 |

| NaCl | 75 | 4.00 | 3.89 |

| KCL | 85 | 4.97 | 4.76 |

| KNO3 | 95 | 7.00 | 7.52 |

| K2SO4 | 98 | 8.51 | 8.51 |

3. Experimental Section

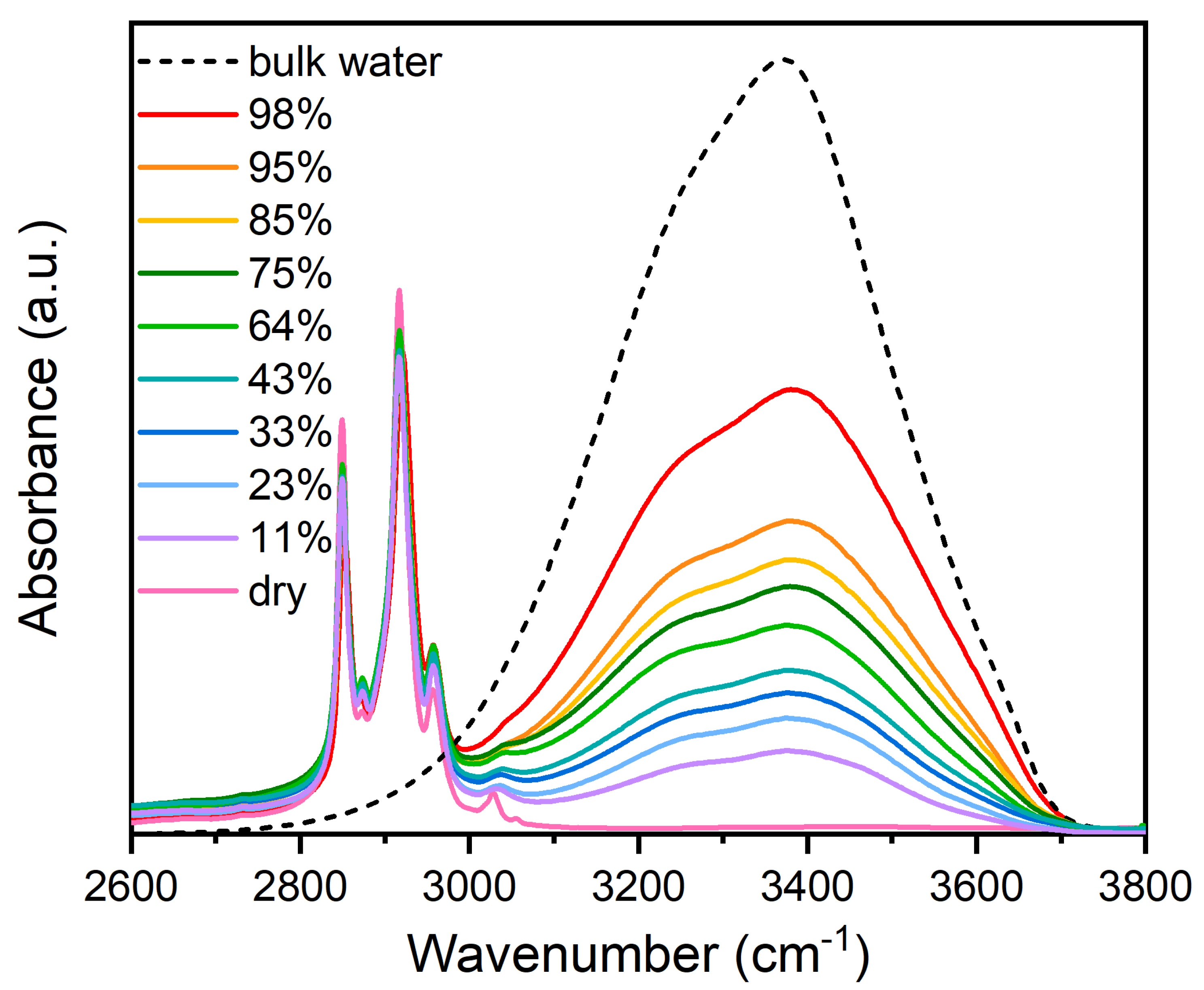

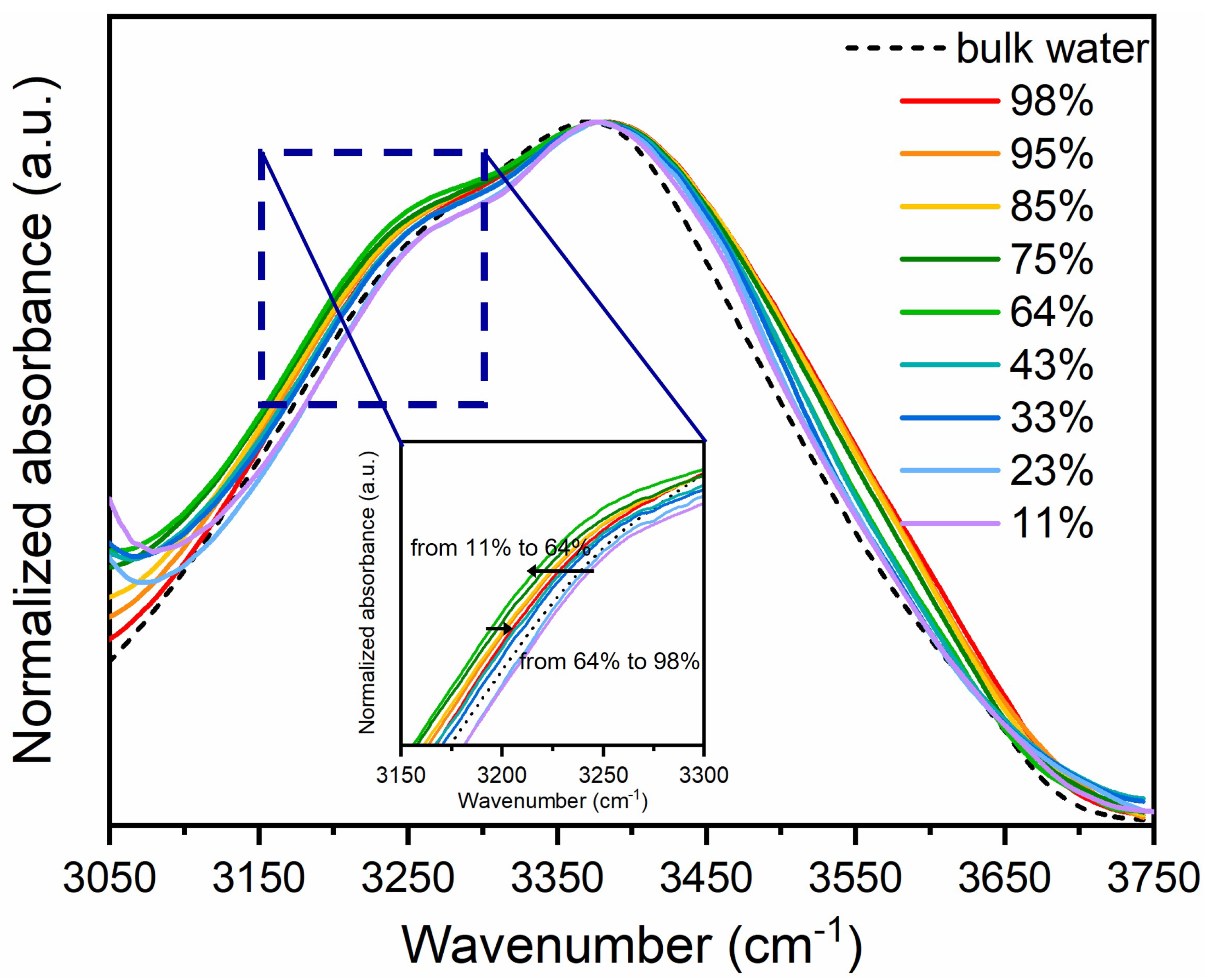

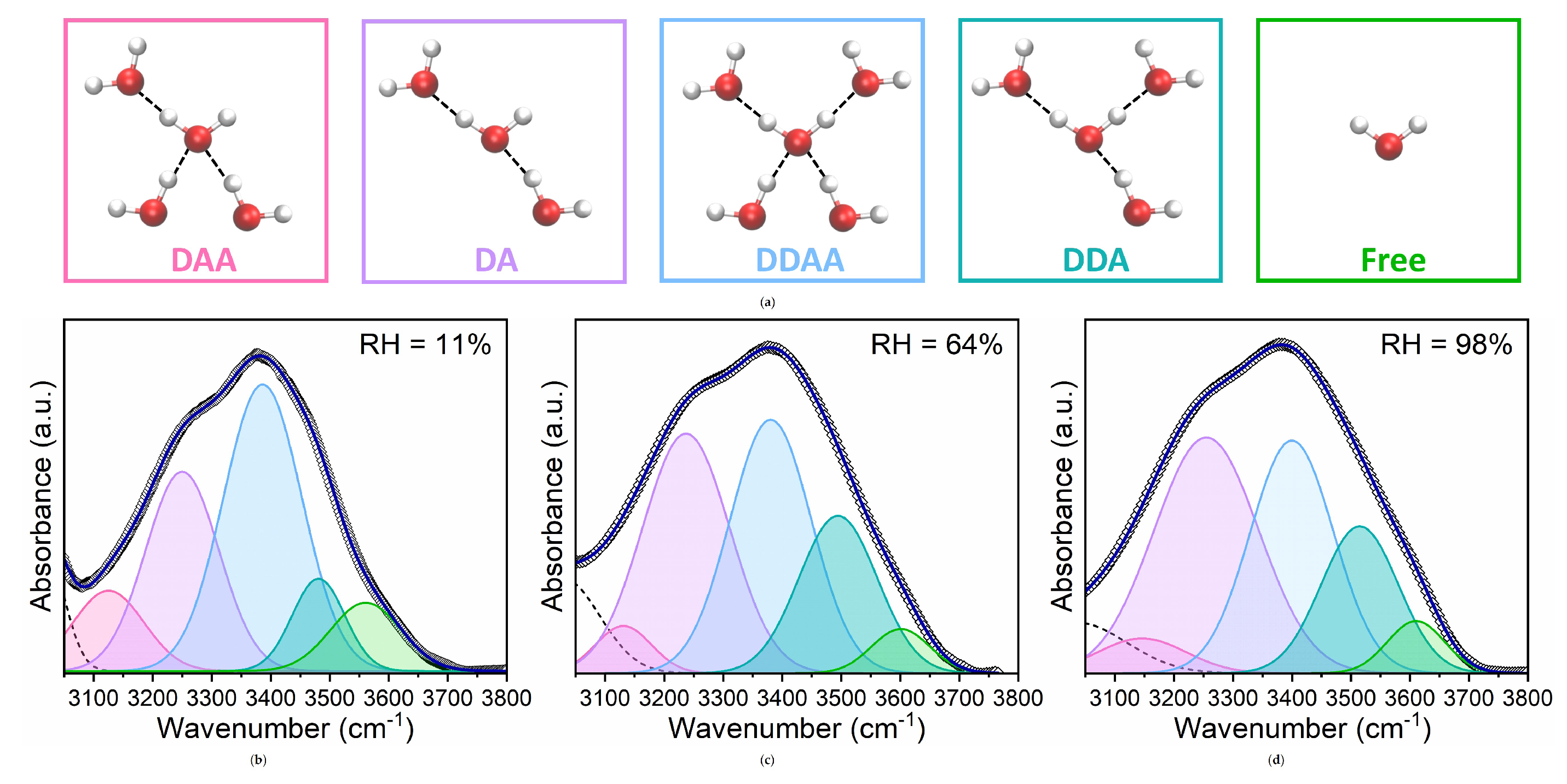

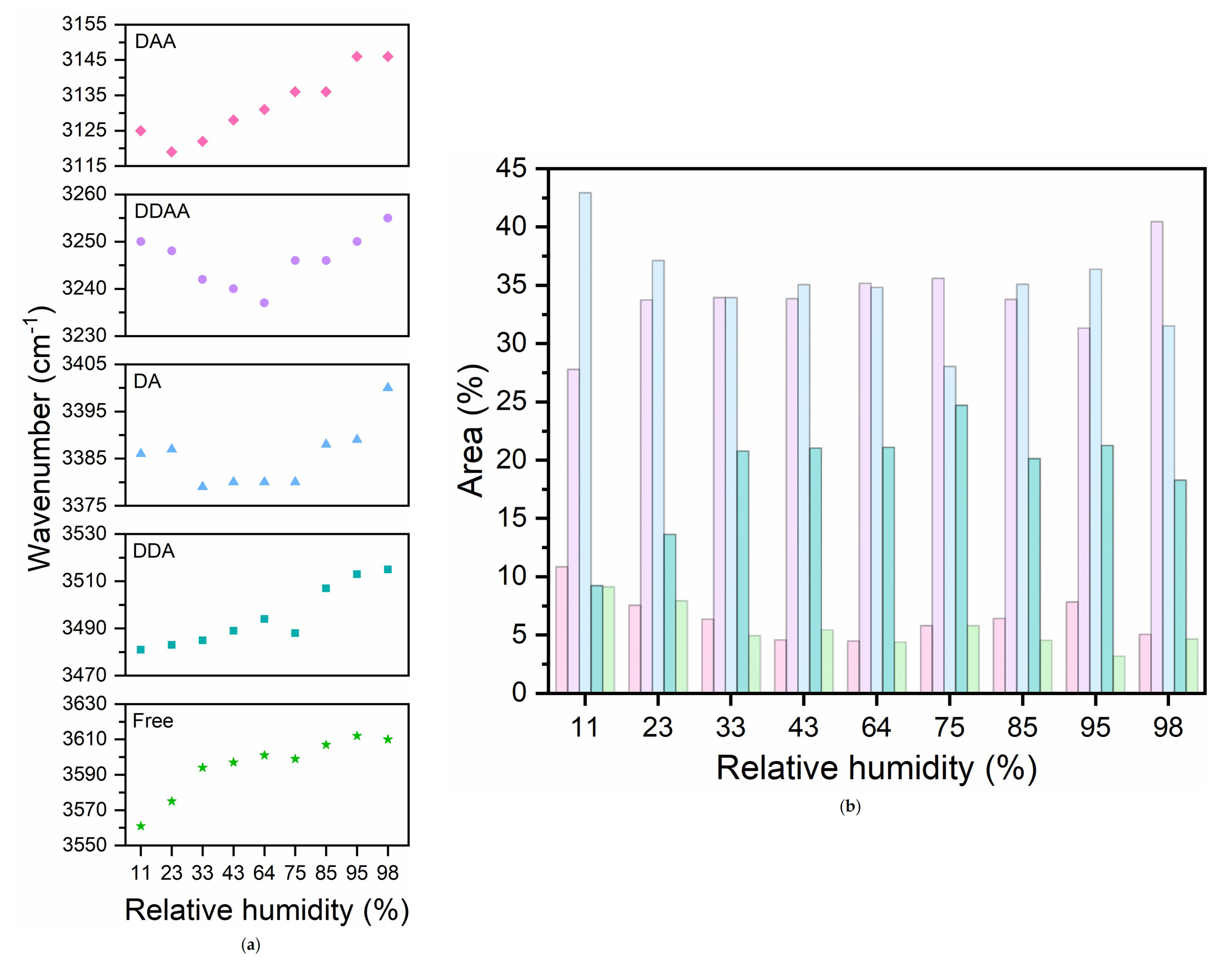

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Abbreviations

| FTIR-ATR | Fourier transform infrared - Attenuated total reflectance |

| DMPC | Dimyristoyl Phosphatidylcholine |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| HBs | Hydrogen Bonds |

References

- Disalvo, E.A. Membrane Hydration: The Role of Water in the Structure and Function of Biological Membranes; Vol. 71, Springer, 2015.

- Milhaud, J. New insights into water–phospholipid model membrane interactions. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2004, 1663, 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashaghi, A.; Partovi-Azar, P.; Jadidi, T.; Nafari, N.; Maass, P.; Tabar, M.R.R.; Bonn, M.; Bakker, H.J. Hydration strongly affects the molecular and electronic structure of membrane phospholipids. The Journal of chemical physics 2012, 136, 03B611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, G.; Conti Nibali, V.; Crupi, C.; Rifici, S.; Wanderlingh, U.; Paciaroni, A.; Sacchetti, F.; Branca, C. Probing intermolecular interactions in phospholipid bilayers by far-infrared spectroscopy. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2017, 121, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nibali, V.C.; Khouzami, K.; Wanderlingh, U.; Branca, C.; D’Angelo, G. Study of the interaction of water with phospholipid bilayers by FTIR spectroscopy. Atti della Accademia Peloritana dei Pericolanti-Classe di Scienze Fisiche, Matematiche e Naturali 2017, 95, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Laage, D.; Elsaesser, T.; Hynes, J.T. Water dynamics in the hydration shells of biomolecules. Chemical Reviews 2017, 117, 10694–10725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitter, J.; Verclas, S.; Lechner, R.; Seelert, H.; Dencher, N. Function and picosecond dynamics of bacteriorhodopsin in purple membrane at different lipidation and hydration. FEBS letters 1998, 433, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.G. How lipids affect the activities of integral membrane proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2004, 1666, 62–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disalvo, E.; Lairion, F.; Martini, F.; Tymczyszyn, E.; Frias, M.; Almaleck, H.; Gordillo, G. Structural and functional properties of hydration and confined water in membrane interfaces. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2008, 1778, 2655–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitter, J.; Lechner, R.; Büldt, G.; Dencher, N. Temperature dependence of molecular motions in the membrane protein bacteriorhodopsin from QINS. Physica B: Condensed Matter 1996, 226, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantsch, H.; McElhaney, R. Phospholipid phase transitions in model and biological membranes as studied by infrared spectroscopy. Chemistry and physics of lipids 1991, 57, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, R.; Fuller, N.; Parsegian, V.; Rau, D. Variation in hydration forces between neutral phospholipid bilayers: evidence for hydration attraction. Biochemistry 1988, 27, 7711–7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepniewski, M.; Bunker, A.; Pasenkiewicz-Gierula, M.; Karttunen, M.; Róg, T. Effects of the lipid bilayer phase state on the water membrane interface. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2010, 114, 11784–11792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, C.F.; Nielsen, S.O.; Klein, M.L.; Moore, P.B. Hydrogen bonding structure and dynamics of water at the dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine lipid bilayer surface from a molecular dynamics simulation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2004, 108, 6603–6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelia, H.; Kaznessis, Y.N. Structure of the antimicrobial β-hairpin peptide protegrin-1 in a DLPC lipid bilayer investigated by molecular dynamics simulation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2007, 1768, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.S.; Cejas, J.P.; Disalvo, E.A.; Frías, M.A. Correlation between the hydration of acyl chains and phosphate groups in lipid bilayers: Effect of phase state, head group, chain length, double bonds and carbonyl groups. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2019, 1861, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, L.M.; de Los Angeles Frias, M.; Morini, M.A.; Belén Sierra, M.; Appignanesi, G.A.; Anibal Disalvo, E. Water populations in restricted environments of lipid membrane interphases. The European Physical Journal E 2016, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, H. Water near lipid membranes as seen by infrared spectroscopy. European Biophysics Journal 2007, 36, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti Nibali, V.; Branca, C.; Wanderlingh, U.; D’Angelo, G. Intermolecular hydrogen-bond interactions in DPPE and DMPC phospholipid membranes revealed by far-infrared spectroscopy. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 10038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Berkowitz, M.L. Orientational dynamics of water in phospholipid bilayers with different hydration levels. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2009, 113, 7676–7680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samatas, S.; Calero, C.; Martelli, F.; Franzese, G. Water between membranes: structure and dynamics. In Biomembrane Simulations; CRC Press, 2019; pp. 69–88.

- Srivastava, A.; Debnath, A. Hydration dynamics of a lipid membrane: Hydrogen bond networks and lipid-lipid associations. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2018, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, C.; Stanley, H.E.; Franzese, G. Structural interpretation of the large slowdown of water dynamics at stacked phospholipid membranes for decreasing hydration level: All-atom molecular dynamics. Materials 2016, 9, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gennis, R.B. Membrane dynamics and protein-lipid interactions. In Biomembranes; Springer, 1989; pp. 166–198.

- Tardieu, A.; Luzzati, V.; Reman, F. Structure and polymorphism of the hydrocarbon chains of lipids: a study of lecithin-water phases. Journal of molecular biology 1973, 75, 711–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanderlingh, U.; D’Angelo, G.; Branca, C.; Conti Nibali, V.; Trimarchi, A.; Rifici, S.; Finocchiaro, D.; Crupi, C.; Ollivier, J.; Middendorf, H. Multi-component modeling of quasielastic neutron scattering from phospholipid membranes. The Journal of chemical physics 2014, 140, 05B602_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, G.; Wanderlingh, U.; Nibali, V.C.; Crupi, C.; Corsaro, C.; Di Marco, G. Physical study of dynamics in fully hydrated phospholipid bilayers. Philosophical Magazine 2008, 88, 4033–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibali, V.C.; D’Angelo, G.; Tarek, M. Molecular dynamics simulation of short-wavelength collective dynamics of phospholipid membranes. Physical Review E 2014, 89, 050301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifici, S.; Corsaro, C.; Crupi, C.; Nibali, V.C.; Branca, C.; D’Angelo, G.; Wanderlingh, U. Lipid diffusion in alcoholic environment. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2014, 118, 9349–9355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifici, S.; D’Angelo, G.; Crupi, C.; Branca, C.; Conti Nibali, V.; Corsaro, C.; Wanderlingh, U. Influence of Alcohols on the Lateral Diffusion in Phospholipid Membranes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2016, 120, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanderlingh, U.; D’Angelo, G.; Nibali, V.C.; Gonzalez, M.; Crupi, C.; Mondelli, C. Influence of gramicidin on the dynamics of DMPC studied by incoherent elastic neutron scattering. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2008, 20, 104214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grdadolnik, J.; Kidri, J.; Had, D.; others. Hydration of phosphatidylcholine reverse micelles and multilayers—an infrared spectroscopic study. Chemistry and physics of lipids 1991, 59, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrondo, J.; Goni, F.; Macarulla, J. Infrared spectroscopy of phosphatidylcholines in aqueous suspension a study of the phosphate group vibrations. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Lipids and Lipid Metabolism 1984, 794, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fringeli, U.P.; Günthard, H.H. Infrared membrane spectroscopy. In Membrane spectroscopy; Springer, 1981; pp. 270–332.

- Jendrasiak, G.L.; Hasty, J.H. The hydration of phospholipids. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Lipids and Lipid Metabolism 1974, 337, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendrasiak, G.L.; Smith, R.L. The interaction of water with the phospholipid head group and its relationship to the lipid electrical conductivity. Chemistry and physics of lipids 2004, 131, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, D.; Morowitz, H.; Prestegard, J. Hydration of phosphatidylocholine. Adsorption isotherm and proton nuclear magnetic resonance studies. Biophysical journal 1977, 20, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagle, J.F.; Tristram-Nagle, S. Structure of lipid bilayers. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Biomembranes 2000, 1469, 159–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.N.; McElhaney, R.N. The structure and organization of phospholipid bilayers as revealed by infrared spectroscopy. Chemistry and physics of lipids 1998, 96, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, W.; Blume, A. Interactions at the lipid–water interface. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 1998, 96, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubach, J.B.; Mermet, A.; Filabozzi, A.; Gerschel, A.; Roy, P. Signatures of the hydrogen bonding in the infrared bands of water. The Journal of chemical physics 2005, 122, 184509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohle, W.; Selle, C.; Fritzsche, H.; Binder, H. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy as a probe for the study of the hydration of lipid self-assemblies. I. Methodology and general phenomena. Biospectroscopy 1998, 4, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsov, Z. Long-Range Lipid-Water Interaction as Observed by ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy. In Membrane Hydration; Springer, 2015; pp. 127–159.

- Rosa, A.S.; Disalvo, E.A.; Frias, M. Water behavior at the phase transition of phospholipid matrixes assessed by FTIR spectroscopy. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2020, 124, 6236–6244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Juhaniewicz-Debinska, J.; Sek, S.; Lipkowski, J. Water structure in the submembrane region of a floating lipid bilayer: The effect of an ion channel formation and the channel blocker. Langmuir 2019, 36, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q. The effects of dissolved hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups on water structure. Journal of Solution Chemistry 2020, 49, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitadai, N.; Sawai, T.; Tonoue, R.; Nakashima, S.; Katsura, M.; Fukushi, K. Effects of ions on the OH stretching band of water as revealed by ATR-IR spectroscopy. Journal of solution chemistry 2014, 43, 1055–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q. Local statistical interpretation for water structure. Chemical Physics Letters 2013, 568, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, D.W. Visualization of the in situ distribution of contents and hydrogen bonding states of cellular level water in apple tissues by confocal Raman microscopy. Analyst 2020, 145, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casal, H.L.; Mantsch, H.H. Polymorphic phase behaviour of phospholipid membranes studied by infrared spectroscopy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Biomembranes 1984, 779, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudert, F.X.; Vuilleumier, R.; Boutin, A. Dipole moment, hydrogen bonding and IR spectrum of confined water. ChemPhysChem 2006, 7, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasenkiewicz-Gierula, M.; Takaoka, Y.; Miyagawa, H.; Kitamura, K.; Kusumi, A. Hydrogen bonding of water to phosphatidylcholine in the membrane as studied by a molecular dynamics simulation: location, geometry, and lipid- lipid bridging via hydrogen-bonded water. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 1997, 101, 3677–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, I.W.; Mushayakarara, E.; Bittman, R. Vibrational assignment of the sn-1 and sn-2 chain carbonyl stretching modes of membrane phospholipids. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 1982, 13, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.N.; McElhaney, R.N. The structure and organization of phospholipid bilayers as revealed by infrared spectroscopy. Chemistry and physics of lipids 1998, 96, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, H.; Pascher, I.; Pearson, R.; Sundell, S. Preferred conformation and molecular packing of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Biomembranes 1981, 650, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.H.; Pascher, I. The molecular structure of lecithin dihydrate. Nature 1979, 281, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozdaganyan, M.E.; Lokhmatikov, A.V.; Voskoboynikova, N.; Cherepanov, D.A.; Steinhoff, H.J.; Shaitan, K.V.; Mulkidjanian, A.Y. Proton leakage across lipid bilayers: Oxygen atoms of phospholipid ester linkers align water molecules into transmembrane water wires. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics 2019, 1860, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Poojari, C.S.; Maznichenko, A.; Roesel, D.; Swiderska, I.; Pohl, P.; Hub, J.S.; Roke, S. Dynamic second harmonic imaging of proton translocation through water needles in lipid membranes. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2024, 146, 19818–19827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verduci, R.; Creazzo, F.; Tavella, F.; Abate, S.; Ampelli, C.; Luber, S.; Perathoner, S.; Cassone, G.; Centi, G.; D’Angelo, G. Water Structure in the First Layers on TiO2: A Key Factor for Boosting Solar-Driven Water-Splitting Performances. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2024, 146, 18061–18073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Song, Y.; Xia, Y.; Hong, J.; Huang, Y.; Ma, R.; You, S.; Guan, D.; Cao, D.; Zhao, M.; others. Nanoscale one-dimensional close packing of interfacial alkali ions driven by water-mediated attraction. Nature Nanotechnology 2024, 19, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkers, W.F.; Oldenhof, H.; Tang, F.; Han, J.; Bigalk, J.; Sieme, H. Factors affecting the membrane permeability barrier function of cells during preservation technologies. Langmuir 2018, 35, 7520–7528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perochon, E.; Lopez, A.; Tocanne, J. Polarity of lipid bilayers. A fluorescence investigation. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 7672–7682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Mukherjee, S. Red edge excitation shift of a deeply embedded membrane probe: implications in water penetration in the bilayer. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 1999, 103, 8180–8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disalvo, E.A.; Bouchet, A.M.; Frias, M. Connected and isolated CH 2 populations in acyl chains and its relation to pockets of confined water in lipid membranes as observed by FTIR spectrometry. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2013, 1828, 1683–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickels, J.D.; Katsaras, J. Water and lipid bilayers. Membrane hydration: The role of water in the structure and function of biological membranes.

- Pohl, P.; Saparov, S.M.; Pohl, E.E.; Evtodienko, V.Y.; Agapov, I.I.; Tonevitsky, A.G. Dehydration of Model Membranes Induced by Lectins from Ricinuscommunis and Viscumalbum. Biophysical journal 1998, 75, 2868–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Stanton, C.; Fitzgerald, G.; Daly, C.; Ross, R. Anhydrobiotics: The challenges of drying probiotic cultures. Food Chemistry 2008, 106, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.L.; Lecak, J.; Acker, J.P. Biopreservation of red blood cells: past, present, and future. Transfusion medicine reviews 2005, 19, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlikowska-Rzeznik, H.; Krok, E.; Domanska, M.; Setny, P.; La̧gowska, A.; Chattopadhyay, M.; Piatkowski, L. Dehydration of Lipid Membranes Drives Redistribution of Cholesterol Between Lateral Domains. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2024, 15, 4515–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).