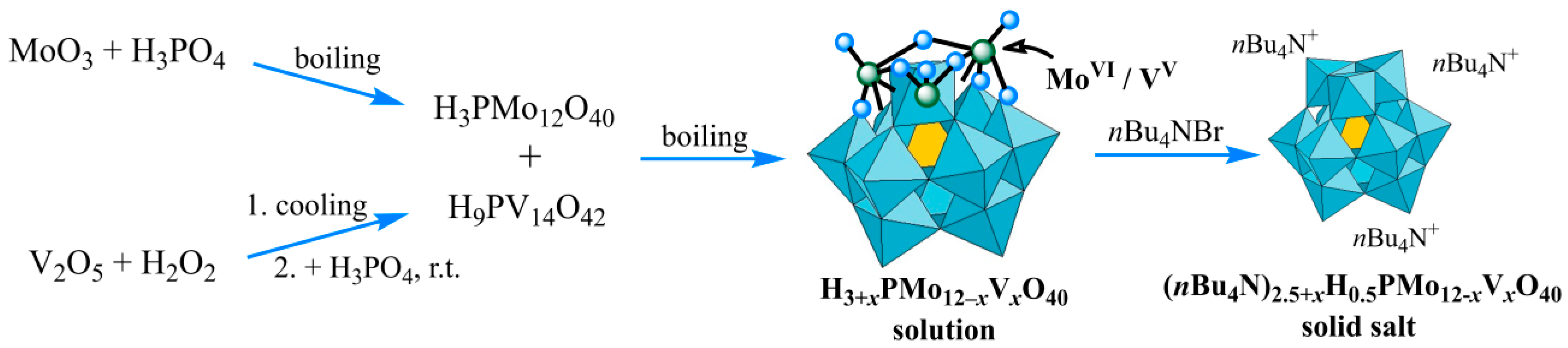

Solutions of HPA-

x with

x of 1–4 were synthesized by careful reacting a phosphomolybdate solution, obtained by dissolving the structure-forming molybdenum(VI) oxide in H

2O/H

3PO

4, with a solution of H

9PV

14O

42, prepared separately by treatment of vanadium(V) oxide using H

2O

2/H

3PO

4 (

Figure 1). Activation of vanadium by

peroxide method according to Eqns. (2) and (3) with its subsequent insertion into Mo-containing framework allowed obtaining HPA-

x solutions free of extraneous ions, part of which was subjected to slow rotary evaporation for preparing the model patterns. These model patterns, as with TBA

2.5+xHPA-

x (

x = 1–4) salts obtained by precipitation with tetra-

n-butylammonium cations, were then characterized by various techniques such as XRD, IR-ATR, TGA, N

2 adsorption–desorption. The elemental composition of the obtained samples was confirmed by ICP-AES with a deviation between the obtained and calculated values of P, Mo, and V contents below 3 wt %.

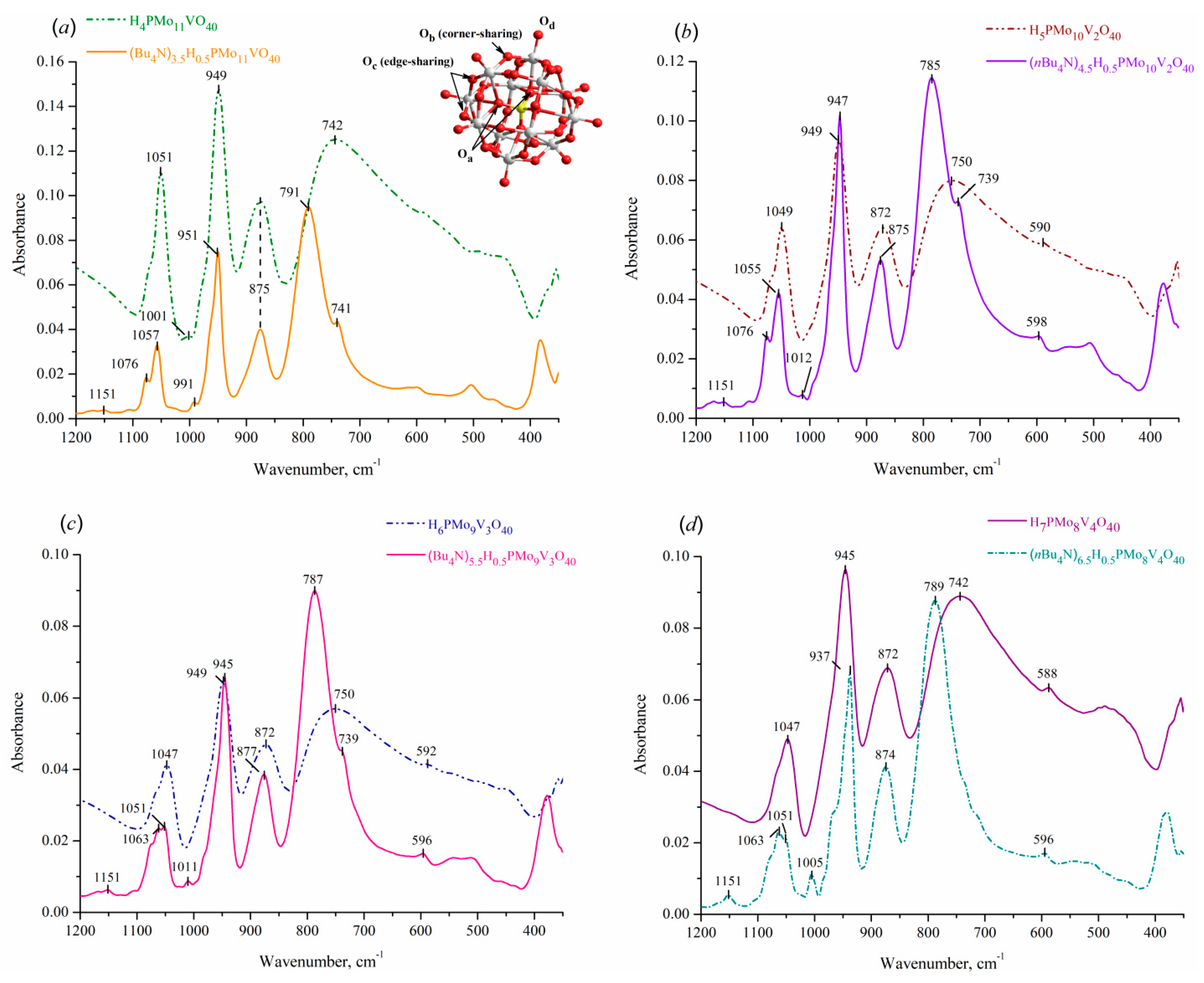

IR-ATR investigations

In general, the formation of mixed [РМo

12-хV

хО

40]

(3+x)– anions can be considered as the replacement of Mo

VI atoms with V

V in the [РМo

12О

40]

3– heteropolyanion, the structure of which can be represented as a central PO

4 tetrahedron surrounded by twelve MoO

6 octahedrons assembled into four Mo

3O

13 triads [

22]. As a consequence, such anion contain twelve quasi-linear Mo-O

b-Mo bonds between octahedrons from different Mo

3O

13 triads, twelve Mo-O

c-Mo bonds between octahedrons within Mo

3O

13 sets, four P-O

a-{Mo

3O

13} bonds between central heteroatom and triads, and twelve terminal bonds Mo=O

d. This leads to the formation of characteristic vibrations of the Keggin anions in the range of 700–1100 cm

–1, which makes IR spectroscopy a convenient method for their characterization.

According to

Figure 2, the spectra of HPA-

x (

x = 1–4) contain four recognized strong absorption peaks in the fingerprint region of the Keggin polyoxoanions, which could be attributed to the fundamental P-O

a, Mo-O

d, Mo-O

b-Mo, and Mo-O

c-Mo asymmetric stretching vibrations. Compared with the IR spectrum of unsubstituted H

3PMo

12O

40 acid [

23], the obtained vibrations in mixed P-Mo-V patterns did not reveal a significant difference, suggesting the formation of the Keggin anions at preparing HPAs-

x via “peroxide” technique. The shoulder observed for P-O

a-{Mo

3O

13} vibrations can be explained by the replacement of Mo atoms by V ones in the framework of HP-anions with formation of Mo-O-V linkages [

24], its presence becoming more noticeable with raising substitution content. Vanadium insertion also affects on the charge and symmetry of anions, causing a slight shift of

νas(Mo-O

d) and

νas(Mo-O

c-Mo) stretching vibrations and a band of

νas(Mo-O

b-Mo) to lower and higher wavenumbers, correspondingly, compared to vanadium-free acid. The same effect was previously observed in the literature [

8,

25], confirming the retaining of the primary structure during the formation of mixed P-Mo-V anions. The similarity of (

nBu

4N)

2.5+xH

0.5PMo

12-xV

xO

40 spectra at 1100–700 cm

–1 region with those of corresponding model acids strongly confirms the retention of the primary structure during the precipitation.

Expanded spectra of the prepared acids (

Figure 3(a)) contain two additional bands at 3340 and 1604 cm

–1 that can be attributed to hydrogen bonds in crystal water [

26]. Insertion of

nBu

4N

+ cations gives rise to new bands at 1481, 1468, and 1381 cm

–1, as well as a set of peaks in the region 3000–2800 cm

–1 (

Figure 3(b)), which originate from asymmetric and/or symmetric bending and stretching vibrations of C–H, –CH

2–, and –CH

3 groups, respectively [

27]. The peaks at 1153 and 1003 cm

–1 can be ascribed to C–N stretching vibrations, whereas other characteristic peaks of

nBu

4N

+ cation appear at 1000–600 cm

–1 and overlap with polyanion fingerprint domain. Nevertheless, it allows supposing that

nBu

4N

+ cation also maintains its structure in the obtained salts without degradation. The registered spectra are in good agreement with those described in the literature for sodium salts of HPAs-

x with

x of 1–3 [

8,

28].

Figure 2.

IR-ATR spectra of (nBu4N)2.5+xH0.5PMo12-xVxO40 acidic salts and corresponding H3+xPMo12-xVxO40 acids with x of 1 (a), 2 (b), 3 (c), and 4 (d) in fingerprint region of the Keggin anion.

Figure 2.

IR-ATR spectra of (nBu4N)2.5+xH0.5PMo12-xVxO40 acidic salts and corresponding H3+xPMo12-xVxO40 acids with x of 1 (a), 2 (b), 3 (c), and 4 (d) in fingerprint region of the Keggin anion.

Figure 3.

Expanded IR-ATR spectra of (a) H3+xPMo12-xVxO40 acids and (b) (nBu4N)2.5+xH0.5PMo12-xVxO40 acidic salts with x of 1–4.

Figure 3.

Expanded IR-ATR spectra of (a) H3+xPMo12-xVxO40 acids and (b) (nBu4N)2.5+xH0.5PMo12-xVxO40 acidic salts with x of 1–4.

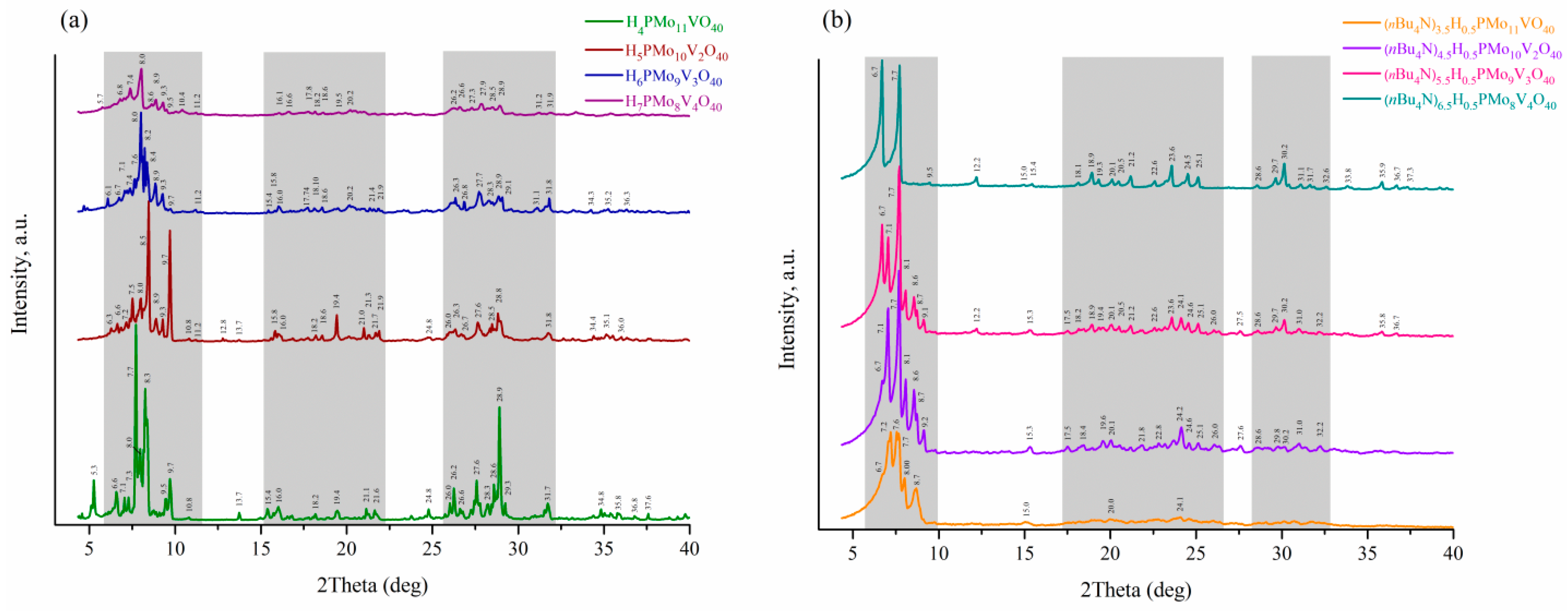

X-ray diffraction

To further investigate the obtained solids, the powder X-ray diffraction patterns were recorded in the 2

θ range of 3°–40°.

Figure 4 shows the diffraction patterns of HPA-

x (

x = 1–4) acids and the corresponding

nBu

4N

+-substituted salts, each of which contains characteristic peaks in similar ranges of 2

θ, with these ranges having a good convergence with those for unsubstituted H

3PMo

12O

40 acid [

8,

29]. Some main peaks in the diffraction patterns keep safe after increasing the vanadium content and replacing protons with

nBu

4N

+ ions, resulting in similarity of obtained profiles. The divergence between obtained patterns and literature data [

30] can be attributed to the difference in content and type of cations and hydration level, which affect the symmetry and arrangement of elements in the unit cell. Redistribution of peak intensities watched with increasing x can be explained by the formation of several isomeric Keggin anions (anions with different values and positions of

x). The presence of separate phases of addenda atoms (MoO

3 and V

2O

5) is not observed.

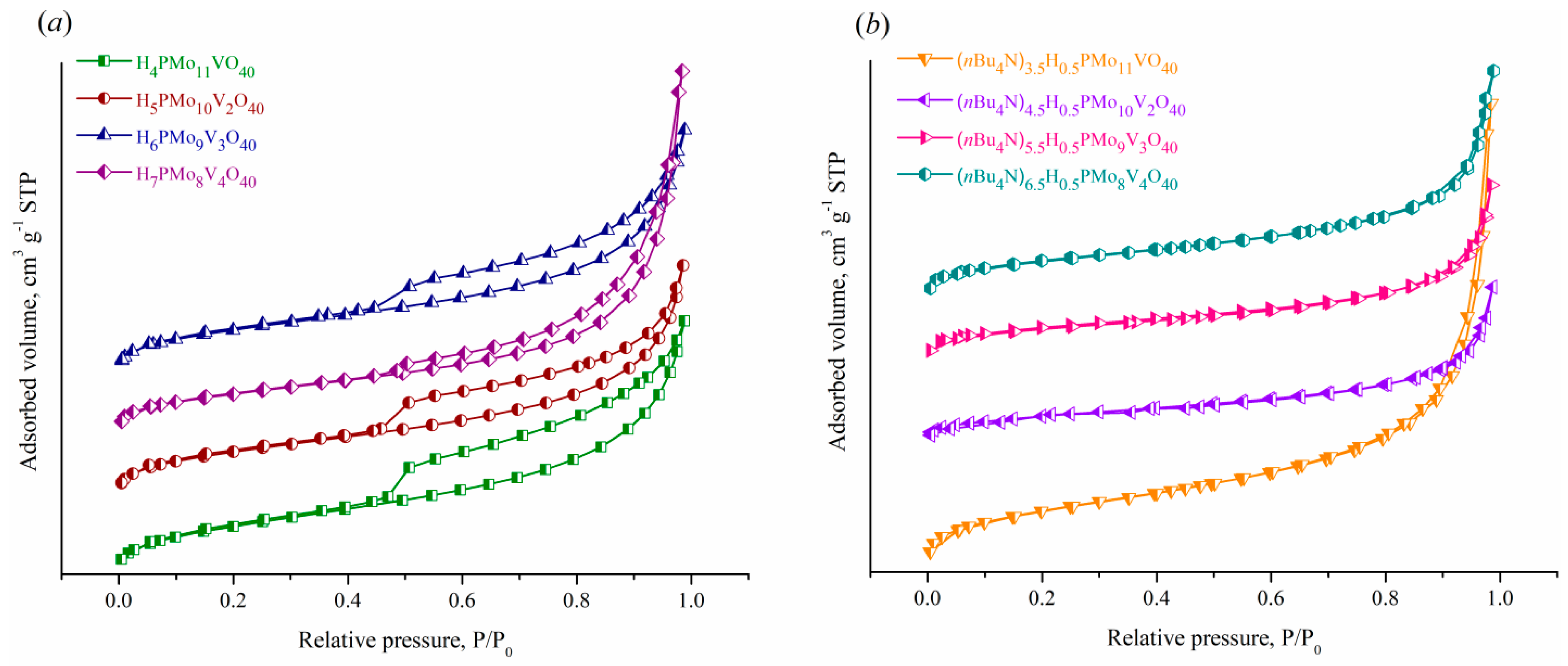

Investigation of textural characteristics

The textural properties of the samples obtained were characterized by low-temperature adsorption-desorption of nitrogen at 77.4 K (

Figure 5,

Table 2).

According to

Figure 5(a), the HPAs-

x have type II isotherms according to the IUPAC classification [

31], characteristic of disperse macroporous and nonporous materials, with H3-shaped hysteresis loops usually attributed to slit-like materials. The adsorption isotherms of TBA

2.5+xHPA-x acidic salts (

Figure 5(b)) are S-shaped curves of the same type with a feebly marked capillary condensation hysteresis loops shifted to the region of

Р/

Р0 > 0.85, which suggests the presence of mesopores. All samples possess a low specific surface area in the range of 2–13 m

2·g

–1 with its values decreasing with passing from parental acids to the corresponding

nBu

4N

+ salts as well as with increasing vanadium(V) content (

Table 2).

Figure 5.

N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of (a) H3+xPMo12-xVxO40 acids and (b) (nBu4N)2.5+xH0.5PMo12-xVxO40 acidic salts with x of 1–4.

Figure 5.

N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of (a) H3+xPMo12-xVxO40 acids and (b) (nBu4N)2.5+xH0.5PMo12-xVxO40 acidic salts with x of 1–4.

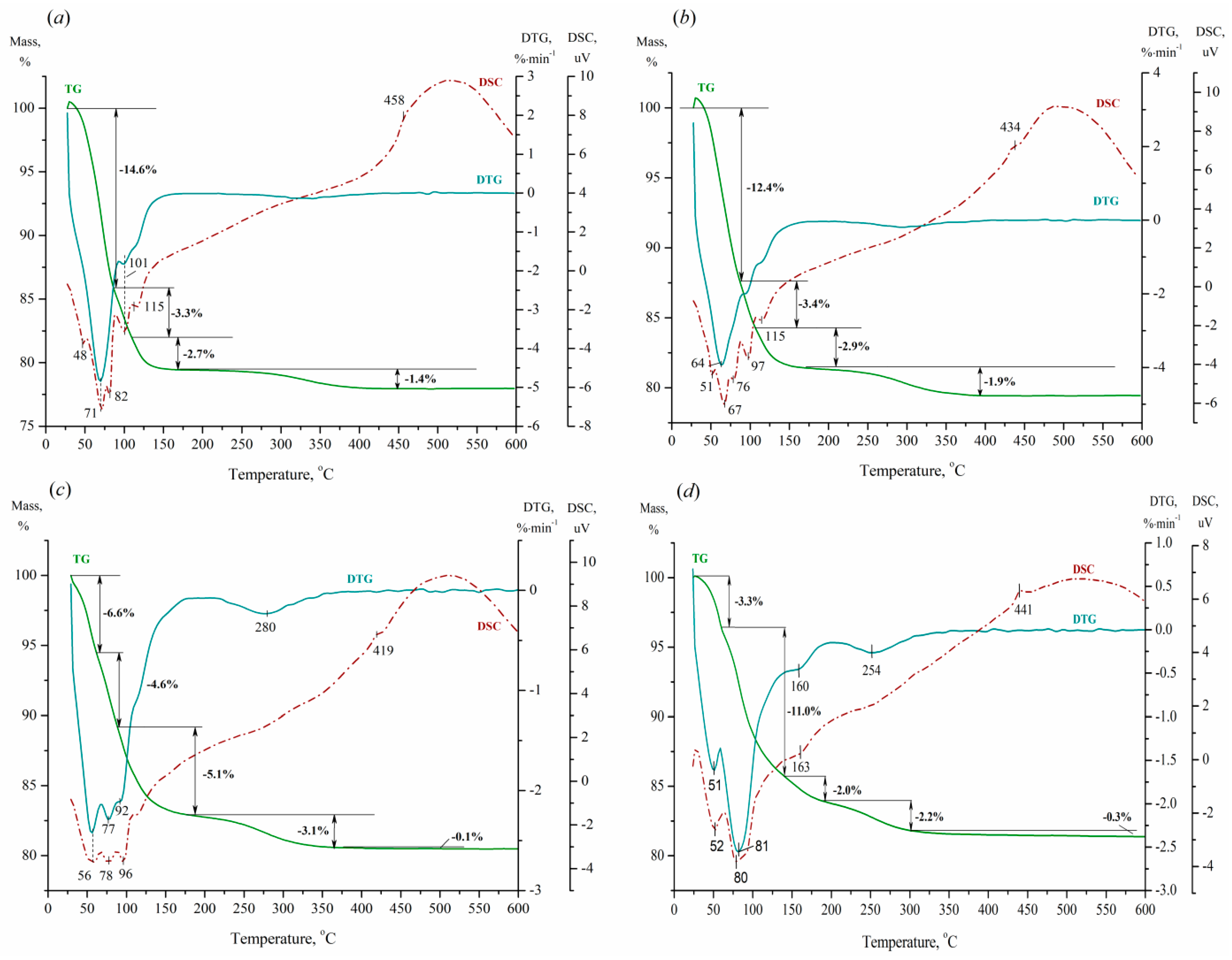

Thermal analysis

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 depict the TG/DTG/DSC profiles of the parental acids and prepared

nBu

4N

+ acidic salts, allowing one to estimate their thermal stability and degree of hydration.

According to

Figure 6, the parental acids exhibit a continuous stepwise loss of weight in the range of room temperature (r.t.) to 419–458°C. The first weight loss occurs at heating the samples from r.t. up to 59–93°C, with a minimum on the DTG curves at 51–70°C. This stage can be assigned to the release of physisorbed water, with its duration and observed weight loss decreasing as

x increases. The second stage proceeds to 89–144°C, with the detected loss of mass increasing in the range of 3.3–11.0% with rising charge of heteropoly anion. It can be attributed to the liberation of zeolitic water. The next thermal event is characterized by a weight damage of 2.0–5.1 wt % and occurs to 165–195°C. This can be ascribed to the elimination of crystallization (hydrogen-bonded to the acidic protons) water to form an anhydrous compound. The subsequent alteration can be ascribed to the loss of structural water (acidic protons) and the beginning of destruction of the Keggin framework with its total collapse to structure-forming oxides near 419–458°C (according to the exothermic peak on the DSC curves). The displacement of these temperatures to the low-temperature region compared to vanadium-free H

3PMo

12O

40 acid (500°C) [

8] seems to be due to reducing symmetry of the Keggin anions at the insertion of vanadium(V) atoms.

Figure 6.

TG/DTG/DSC profiles of H3+xPMo12-xVxO40 acids with x of 1 (a), 2 (b), 3 (c), and 4 (d).

Figure 6.

TG/DTG/DSC profiles of H3+xPMo12-xVxO40 acids with x of 1 (a), 2 (b), 3 (c), and 4 (d).

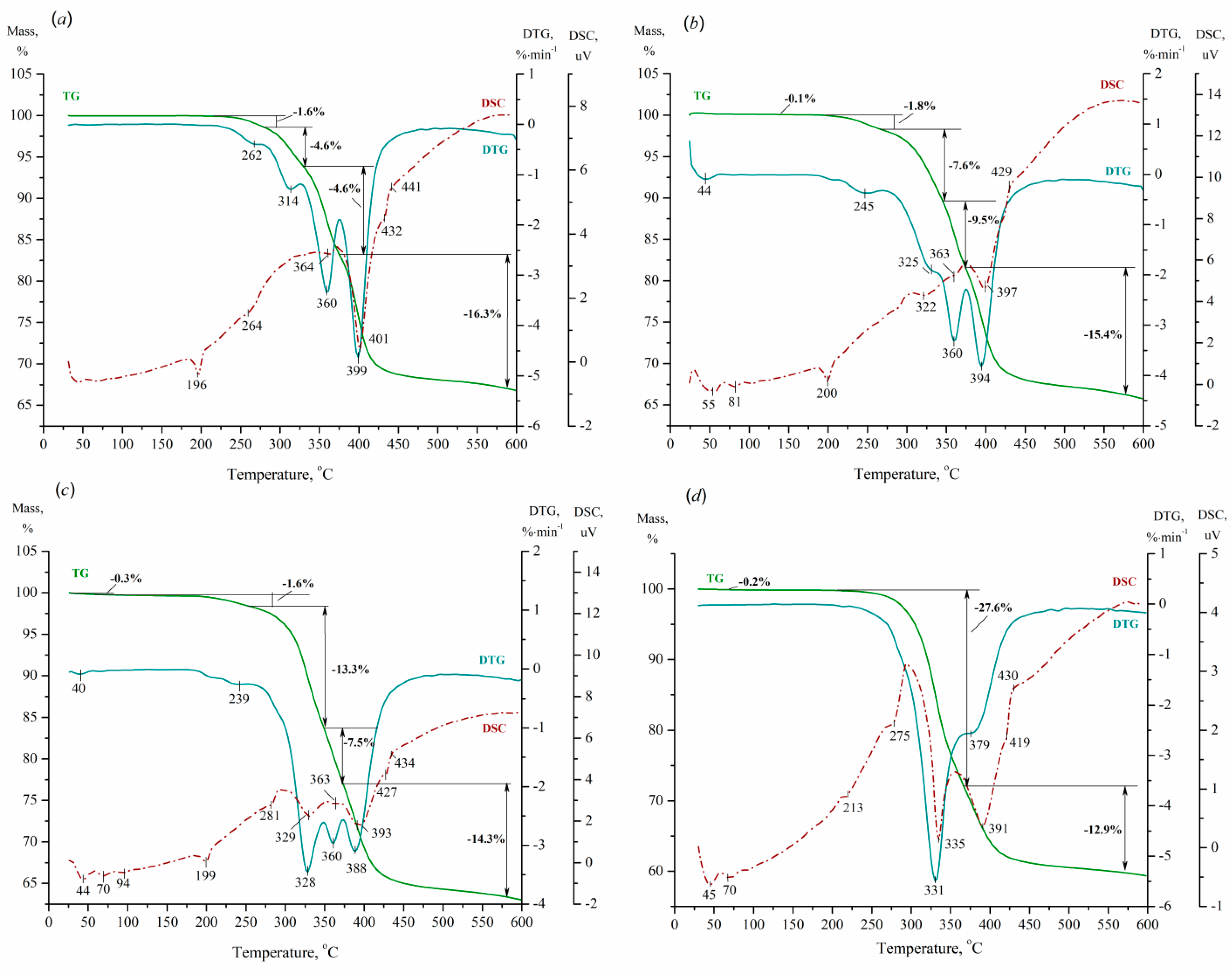

According to

Figure 7, the TG curves of TBA

2.5+xHPA-

x acidic salts have a relatively constant value to 185–210°C, after which they continuously decrease up to 430–440°C. The observed decrease in the TG curves is reflected by a large and broad endothermic peak on the DTG curves, which contains from 2 to 4 marked minima depending on the salt composition. This stepwise loss of weight can be assigned to the decomposition and removal of

nBu

4N

+ cations, as well as to the same processes discussed above for the parental acids. Additional peaks are present in the DSC profiles up to 215°C, indicating minor intermediate rearrangements, presumably due to three-dimensional

nBu

4N

+ cations. It can be concluded that the prepared salts are stable up to at least 370°C without loss of

nBu

4N

+ cations and degradation of the Keggin anions. It is obvious that the replacement of H

+ ions with

nBu

4N

+ cations leads to an increase in thermal stability.

Figure 7.

TG/DTG/DSC profiles of (nBu4N)2.5+xH0.5PMo12-xVxO40 salts with x of 1 (a), 2 (b), 3 (c), and 4 (d).

Figure 7.

TG/DTG/DSC profiles of (nBu4N)2.5+xH0.5PMo12-xVxO40 salts with x of 1 (a), 2 (b), 3 (c), and 4 (d).

Investigation of hydrolytic stability

The stability of the catalyst under reaction conditions is an important criterion for the successful implementation of the process, as well as proof of the heterogeneous nature of the reaction. The study of the synthesized TBA2.5+xHPA-x salts for stability and solubility was performed in 3 cycles by hydrothermal treatment at boiling temperature for 3 h. After completion of each treatment, the solid was separated and investigated by IR-ATR and XRD, whereas the mother liquor was analysed by ICP-AES for P, Mo and V content.

According to the data obtained, the solubility of salts after the first treatment cycle changed in the following series: TBA6.5HPA-4 (0.6%) < TBA5.5HPA-3 (0.8%) < TBA3.5HPA-1 (1.4%) < TBA4.5HPA-2 (2.2%). After the second cycle of treatment, the solubility of the samples was: TBA6.5HPA-4 (0.2%) < TBA5.5HPA-3 (0.3%) < TBA3.5HPA-1 (0.8%) < TBA4.5HPA-2 (1.2%). After the third treatment cycle, the solubility of TBA4.5HPA-2 salt has continued to decrease and amounted to 1.0%; for the others salts, the total leaching of the components was less than 0.1%, which confirms their heterogeneous nature.

Characterization of spent salts by XRD and IR-ATR (Fig. S1 and S2) showed significant structural stability of nBu4N+-containing acidic salts. The IR spectra and diffraction patterns of fresh salts and their spent samples were similar, with for TBA6.5HPA-4 and TBA5.5HPA-3 these being almost identical. For these samples, no perceivable differences in both peak intensities and their position, as well as no disappearance of peaks or the appearance of new bands, were observed in the obtained spectra. This confirms the preservation of the Keggin structure in spent solids and implies that (nBu4N)2.5+хH0.5PMo12-хVхO40 with x of 3 and 4 are stable and reusable water-insoluble compounds. As a consequence, owing to the presence of vanadium(V) atoms capable of oxidation, these salts can potentially be used as catalysts for the transformation of organic compounds.

Catalytic tests

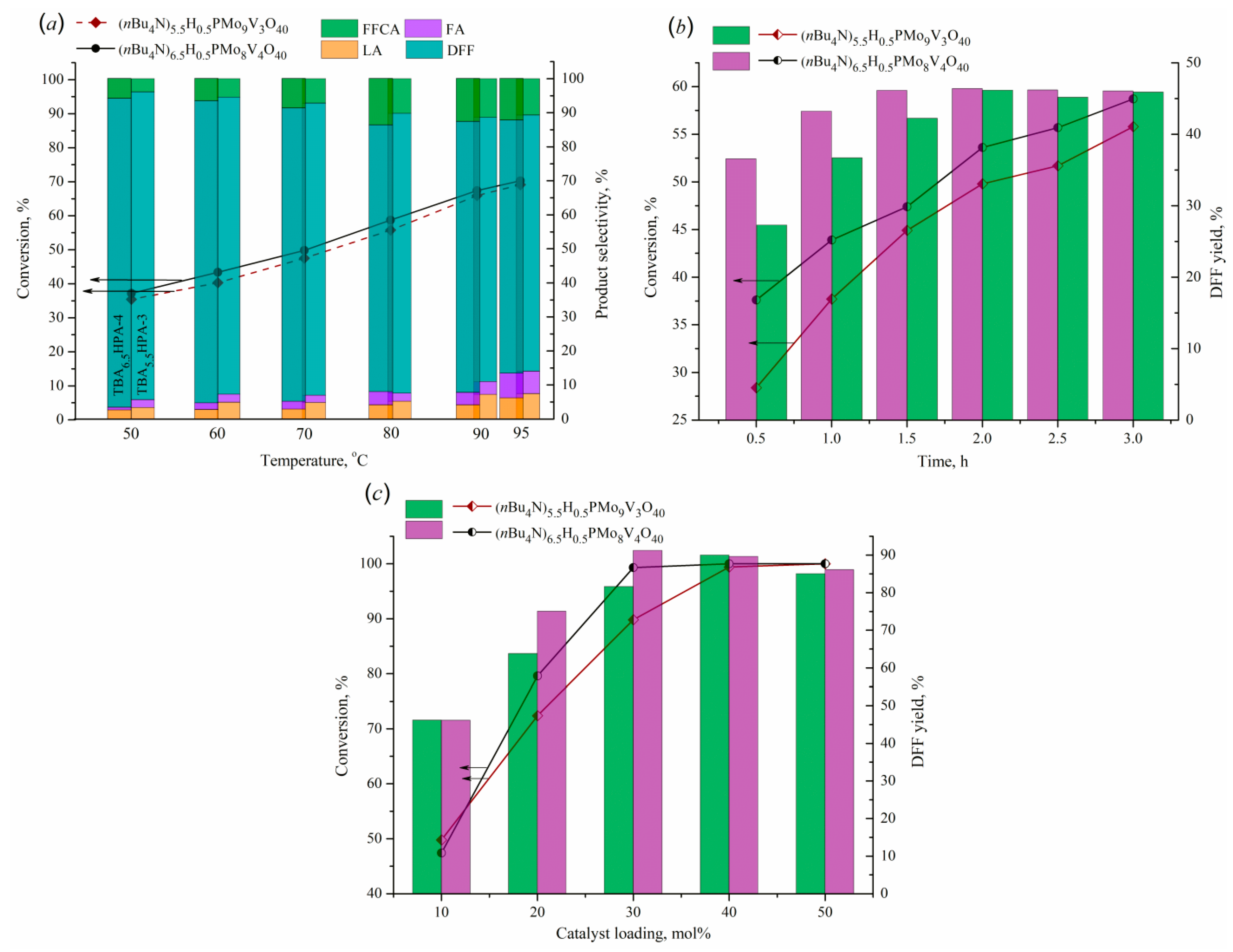

The catalytic activity of the obtained salts was studied in the oxidation reaction of 5-HMF as a model substrate. This reaction was disclosed to result in a preferred production of DFF with some formation of 5-formyl-2-furancarboxylic (FFCA), levulinic (LA), and formic (FA) acids as by-products. The influence of several parameters on 5-HMF conversion and DFF selectivity, such as temperature, substrate-to-catalyst molar ratio, and reaction time, was investigated and presented in

Figure 8.

The first series of experiments was aimed at assessing the effect of temperature (

Figure 8(a)). It was found that increasing the reaction temperature in the range of 50–95°C had a positive action on substrate conversion, raising it from 35 to 70%. The use of TBA

6.5HPA-4 salt leads to slightly superior values compared to TBA

5.5HPA-3, evidencing that the content of vanadium has a beneficial effect on the transformation of 5-HMF. Besides higher conversion, TBA

6.5HPA-4 catalyst also provides the greater yield toward the desired product (DFF), which some rises with increasing temperature. Selectivity of products changes differently that can be associated with varying in the contribution of processes of DFF overoxidation and 5-HMF hydration. The data obtained show that a temperature of 80°C provides the best relationship between the conversion of 5-HMF and the selectivity of DFF relative to other products.

Changing the reaction time in the range of 0.5–3 h (

Figure 8(b)) showed that although the substrate conversion increased over time for both catalysts, the selectivity of the products progressed various. The best yield of the target product for TBA

6.5HPA-4 is achieved after 1.5 hours and then practically does not change, while for TBA

5.5HPA-3 a similar yield value is observed only after 2 hours.

Estimating the influence of catalyst loading showed the predominant formation of DFF in the entire studied range, with an increase in catalyst content leading to a considerable raise of 5-HMF conversion (

Figure 8(c)). It was found that the yields of FA and LA reduced monotonically with increasing catalyst amount, which indicates rising the rate of the target reaction and predominating oxidation process over the hydration of 5-HMF. On the other hand, the application of high catalyst loading resulted in increasing DFF overoxidation with the formation of 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) as another by-product.

Figure 8.

Effect of reaction temperature (a), process time (b), and catalyst loading (c) on 5-HMF conversion and product selectivity (a) or DFF yield (b, c). Reaction conditions: (a) 5-HMF (0.39 mmol) in H2O (5 mL), catalyst (10 mol%) in H2O (15 mL), 3 h, 0.1 MPa O2; (b) 5-HMF (0.39 mmol) in H2O (5 mL), catalyst (10 mol%) in H2O (15 mL), 80°C, 0.1 MPa O2; (c) 5-HMF (0.39 mmol) in H2O (5 mL), catalyst (10–50 mol%) in H2O (15 mL), 80°C, 0.1 MPa O2, 1.5 h (for TBA6.5HPA-4) or 2 h (for TBA5.5HPA-3).

Figure 8.

Effect of reaction temperature (a), process time (b), and catalyst loading (c) on 5-HMF conversion and product selectivity (a) or DFF yield (b, c). Reaction conditions: (a) 5-HMF (0.39 mmol) in H2O (5 mL), catalyst (10 mol%) in H2O (15 mL), 3 h, 0.1 MPa O2; (b) 5-HMF (0.39 mmol) in H2O (5 mL), catalyst (10 mol%) in H2O (15 mL), 80°C, 0.1 MPa O2; (c) 5-HMF (0.39 mmol) in H2O (5 mL), catalyst (10–50 mol%) in H2O (15 mL), 80°C, 0.1 MPa O2, 1.5 h (for TBA6.5HPA-4) or 2 h (for TBA5.5HPA-3).

According to the data obtained, total substrate conversion and DFF selectivity of 91.2% are achieved in oxygen atmosphere (0.1 MPa) for 1.5 h at 80°C in the presence of TBA

6.5HPA-4 catalyst at its loading of 30 mol %. The content of by-products is 2.6, 2.3 and 3.8% for LA, FA, and FFCA, respectively. Similar result in DFF yield of 90.9% can be obtained in the presence of TBA

5.5HPA-3 catalyst, but this requires the application of a larger catalyst load (40 mol %) and an increase in reaction time to 2 h. The reached conversion and selectivity values are close to those for state-of-the-art solid catalysts studied in the oxidation of 5-HMF under similar conditions with water as a solvent [

32].

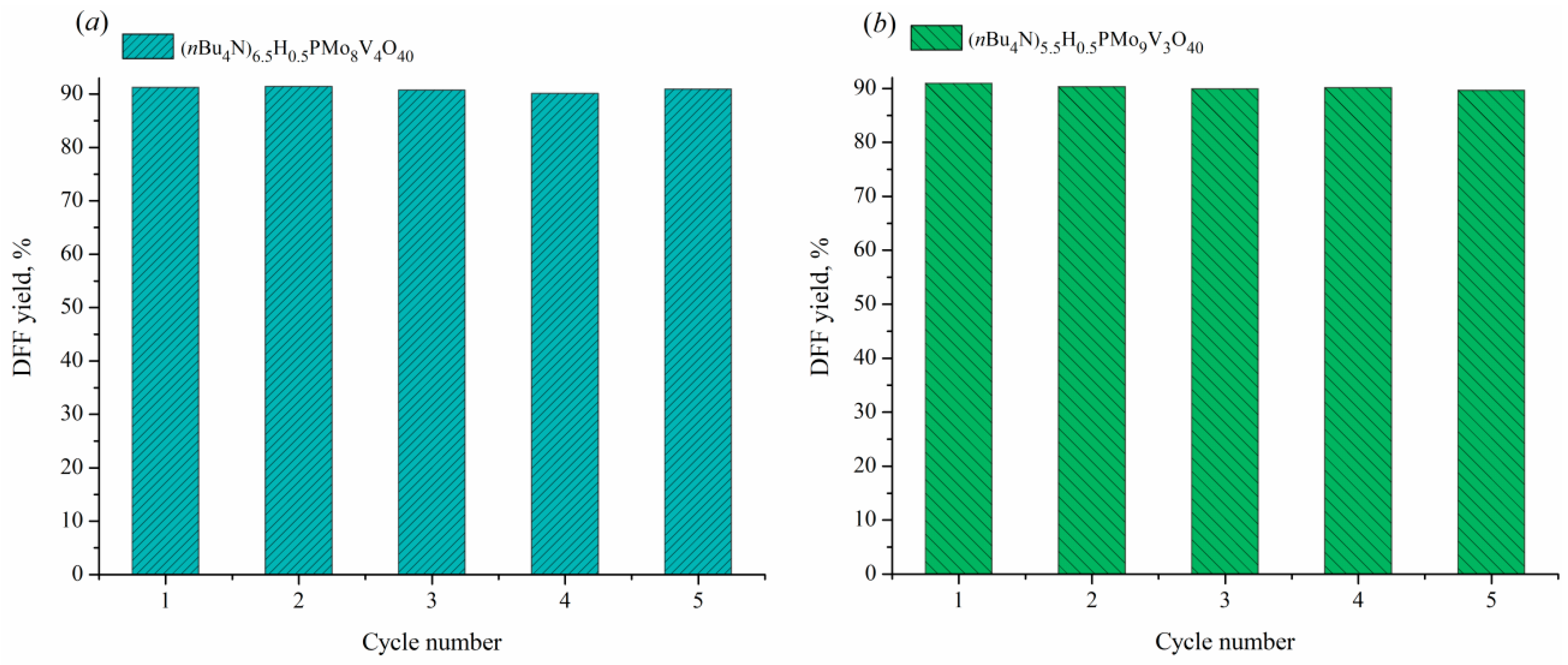

Investigation of catalyst reusability

The reusability of TBA2.5+xHPA-x (x = 3, 4) was investigated in 5 cycles of 5-HMF oxidation (Fig. (9)). After each reaction, the spent catalyst was separated by centrifugation and calcined at 150°C for 3 h in oxygen atmosphere. Both catalysts were found to demonstrate high stability and retention of catalytic activity during repeated application with the yield spread below 1.3%. The XRD patterns and IR spectra of the spent catalysts after 5 runs were identical to those of the samples after threefold hydrothermal treatment.

Figure 9.

The change of DFF yield during 5 runs in the presence of TBA6.5HPA-4 (a) and TBA5.5HPA-3 (b). Conditions: (a) 5-HMF (0.39 mmol) in H2O (5 mL), catalyst (30 mol%) in H2O (15 mL), 80°C, 1.5 h, 0.1 MPa O2; (b) 5-HMF (0.39 mmol) in H2O (5 mL), catalyst (40 mol%) in H2O (15 mL), 80°C, 2 h, 0.1 MPa O2.

Figure 9.

The change of DFF yield during 5 runs in the presence of TBA6.5HPA-4 (a) and TBA5.5HPA-3 (b). Conditions: (a) 5-HMF (0.39 mmol) in H2O (5 mL), catalyst (30 mol%) in H2O (15 mL), 80°C, 1.5 h, 0.1 MPa O2; (b) 5-HMF (0.39 mmol) in H2O (5 mL), catalyst (40 mol%) in H2O (15 mL), 80°C, 2 h, 0.1 MPa O2.