1. Introduction

The intersection of mental health and university life has become increasingly prominent, with institutions often characterised as 'anxiety machines' [

1]. Studies and reports identified concerns with students’ mental health situation in multiple countries. For example, Lipson and colleagues analysed 10 years of data from the Healthy Minds Study and found significantly increased rates of mental health treatment and diagnosis among students in the United States [

2,

3]. The New Zealand Union of Students’ Associations [

4] produced the Kei Te Pai? Report in 2018 (Kei Te Pai means fine or good in Te Reo Māori). It reviewed tertiary students’ mental health and found that university students commonly experience moderate levels of psychological distress.

Similarly, in the past two decades, academic work has become more demanding. The main reason for this include dramatically increasing student numbers [

5] and the students-as-consumer model derived from commercialised culture [

6]. As a result, universities have then been characterised as “a generator of anxiety and pressure” [

7]. Guthrie

et al. [

8], commissioned by the Royal Society and Wellcome Trust, explored the mental health in researchers, including academic staff and postgraduate students in universities, in the United Kingdom. They found that the level of job stress among university staff was comparable to that of healthcare workers, a high-risk group, with over 40 per cent of postgraduate students reporting symptoms of depression, emotional or stress-related problems, or high levels of stress. They also noted a lack of effective interventions and support for researchers, with even less literature evaluating the situation. Nicholls and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 26 papers and identified seven key themes of academic researchers’ mental health experiences [

9], highlighting that lack of job security coupled with high expectations has left researchers at risk of poor mental health and well-being.

However, universities need not be synonymous with stress; they can be places that foster health and well-being. This can be achieved not only through the curriculum but also by creating environments that promote healthy lifestyles. In 2015, the World Health Organization presented the Okanagan Charter, highlighting the role of higher education institutions in enhancing the health of those who live, learn, work, and play on campuses [

10]. Universities are well-placed to educate students about healthy life choices and to instil the value of maintaining health and well-being in everyday life. They are also workplaces for staff who spend a significant portion of their daily lives there. As the Okanagan Charter pointed out, work should be a source of health rather than consuming it.

Universities worldwide have gradually adopted the Okanagan Charter and prioritised health promotion in their agendas, including the University of British Columbia and the University of Waterloo in Canada, the University of Melbourne in Australia, Glasgow Caledonian University in the United Kingdom, and the University of Auckland and the University of Otago in New Zealand. However, as Travia et al. pointed out in their study in 2020, universities globally are still in the early stages of embracing well-being as one of their core objectives [

11].

From a landscape architecture point of view, nature and landscapes have long been recognised to possess ‘healing’ power [

12] and there has been considerable discussion about using natural landscapes to promote health and well-being in communities [

13]. However, only limited research has examined the relationship between campus landscape design and health promotion. For example, Lau & Yang explored the application of healing gardens to campus design to create a health-supportive and sustainable campus environment in Hong Kong University [

14]. Studies by Mt Akhir et al. mainly discussed the health effects of planting design on campus [

15,

16,

17]. Holt et al. recognised the positive effects from social interactions during physical exercise sessions in green spaces, which they referred to as green exercises [

18]. McDonald-Yale & Birchall explored winter design strategies that contribute to students’ well-being for northern campuses [

19].

Despite these studies, there remains a noticeable gap in empirical research on the role of campus landscapes in promoting mental health, particularly in New Zealand. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by investigating how campus landscape design supports relaxation for both students and staff. By exploring the uses and preferences of campus landscapes for relaxation, we seek to inform future designs of health-promoting campus environments.

2. Materials and Methods

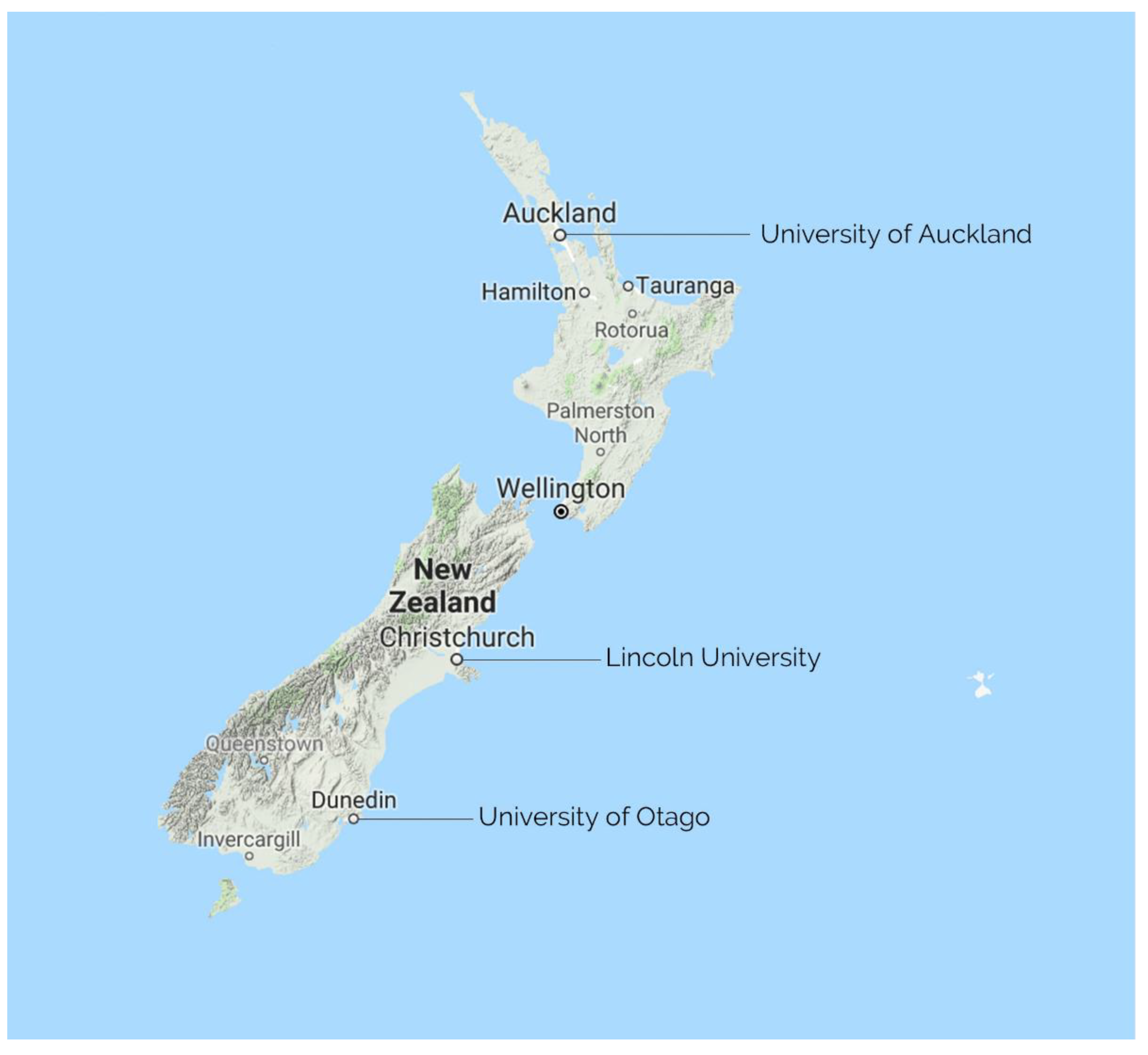

A comparative multi-case study was conducted with 66 participants including students, staff, and medical workers on campus from the city campus of the University of Auckland in Auckland, Lincoln University in Christchurch, and University of Otago in Dunedin in terms of their relaxation experience associated with campus landscapes (see

Figure 1). In-depth individual interviews were conducted during semester time in September and October 2018.

Drawing on the methods used by previous studies, interviews and surveys are common methods used in restorative environment studies where they investigated participants’ responses to videotapes or photos of landscapes [

20,

21,

22]. However, the experience of the environment is multi-sensory, e.g., the temperature varies outside but it is stable in a room. It could be argued that traditional interviews that take place in an office may not be sufficient to collect explicit responses about the studied environment. Therefore, this study adopted a walking interview technique as an addition to traditional interviews to collect explicit responses about the studied environment from interviewees. Walking in the studied environments can provoke a sense of connection to the environment, which grants access for the researcher to respondents’ attitudes and knowledge about the environment, and thus offers privileged insights [

23].

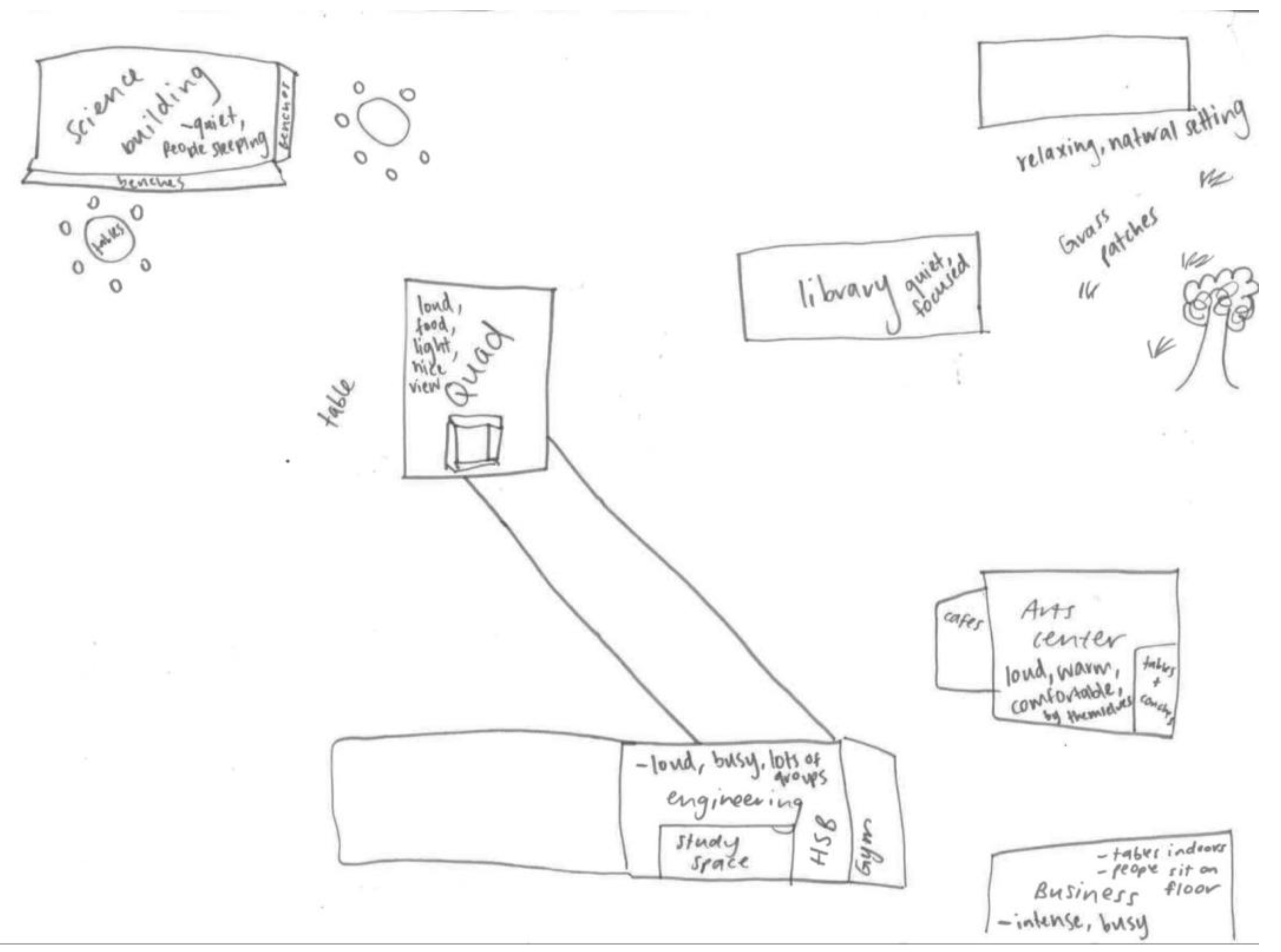

Another interview technique adopted was the mental mapping exercise that asks respondents to draw and write about relaxation experience on campus. This technique was particularly helpful when respondents were not able to conduct a walking interview due to their availability. The action of drawing can encourage spatial thinking which helps respondents to convey the everyday life image in their head.

Interviews taking place in the field offered the opportunity to conduct direct observation on site as well, which can help strengthen the data quality. Direct observation enables evaluation of campus space use and justification of information provided by respondents from the perspective of a trained landscape architect. Photographs of campus landscapes used for relaxation were taken and, as Dabbs suggests, photographs of the site contain important characteristics of the studied site, which facilitate outside observers’ understanding [

24].

Data collection was carried out in the order of University of Otago, Lincoln University, and the University of Auckland to make sure data were collected before their semesters ended when spaces were being used by campus users.

Each mental mapping exercise took around 5 to 15 minutes, which was a reasonable amount of time that campus users were willing to spend during their working day. Conversations with participants were recorded. Two open-ended questions were also presented to participants after they finished their drawing to encourage reflection and gain more insights into their relaxation experience and their perceptions of relaxation spaces on campus. The questions were:

If you were going to use some keywords to describe the relaxation spaces you have drawn, what would they be?

What do you think are the most important factors for an outdoor space to be inviting/attractive for a university user to come and relax?

Each participant was asked if s/he was interested and available to do a further walking interview after finishing the mental mapping exercise. For those who were willing to participate, we arranged a time before the researcher left to avoid the difficulty of reaching participants again by email.

The walking interviews allowed participants to lead the way to the relaxation spaces they had identified on their maps. Detached from their workplaces, they were more willing to discuss campus relaxation spaces and even shared personal opinions on health and well-being. Being in the environment helped them recall their experiences on campus, and they often told stories of friends' or colleagues' relaxation experiences. Additionally, while on campus, participants could identify spaces they had overlooked and not included in their mental maps. For example, during one interview, as we stepped out of the building, a participant stopped and mentioned he had somehow omitted the courtyard—the closest space to his workplace—from his map. The walking interviews also provided opportunities for the researcher to share their direct observations about the campus and ask for their opinions.

3. Results

3.1. The Importance of Natural Landscapes on Campus

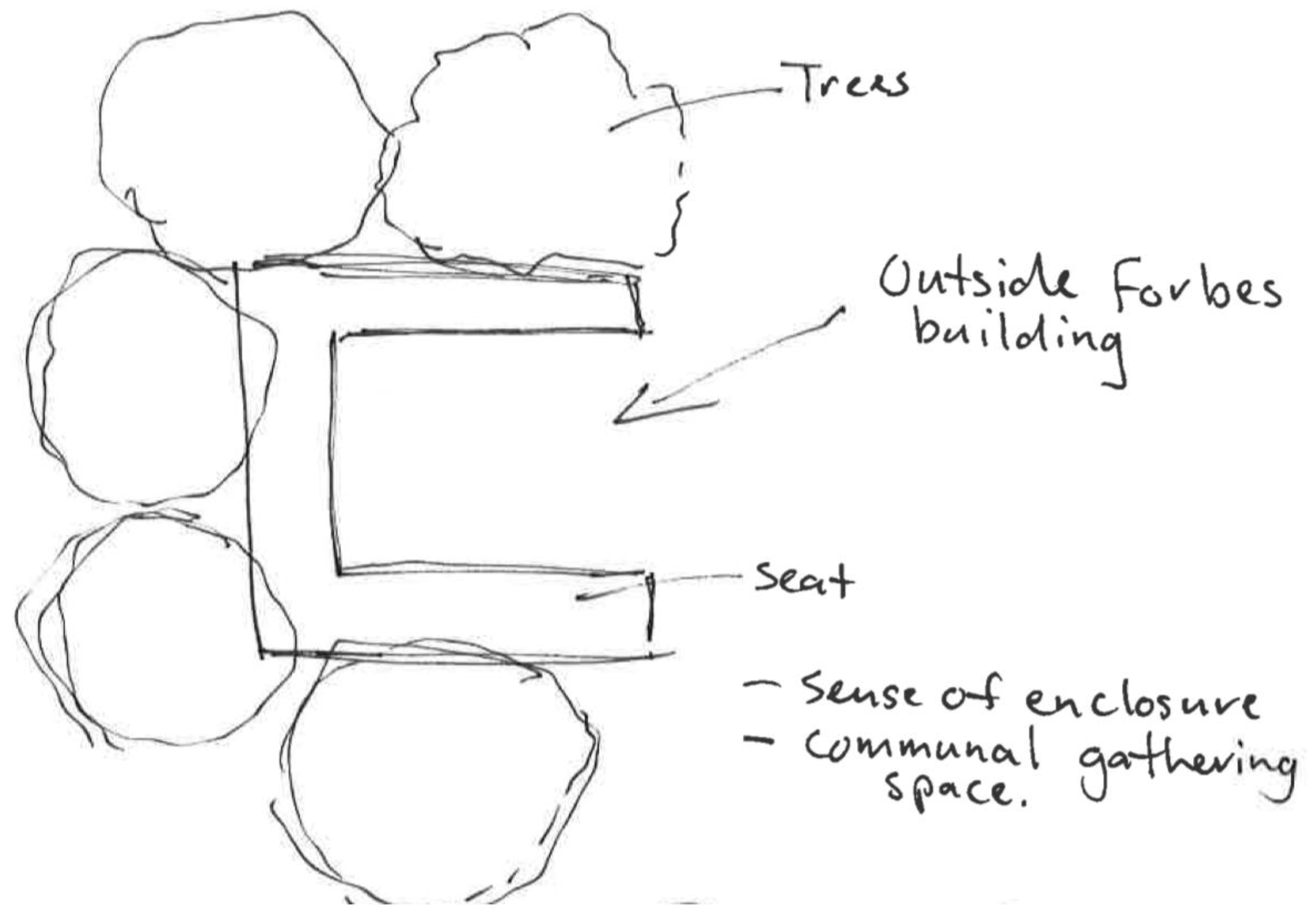

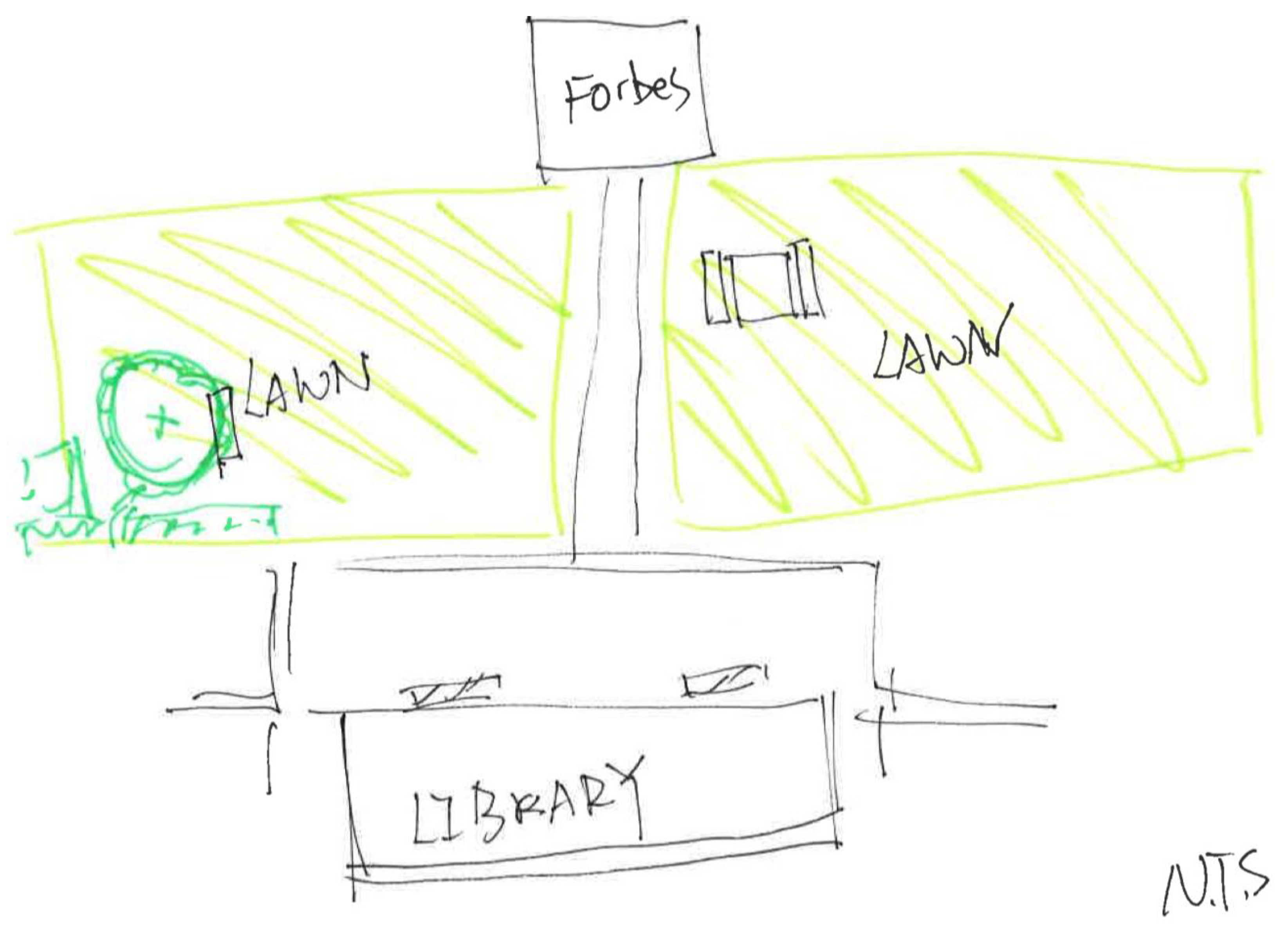

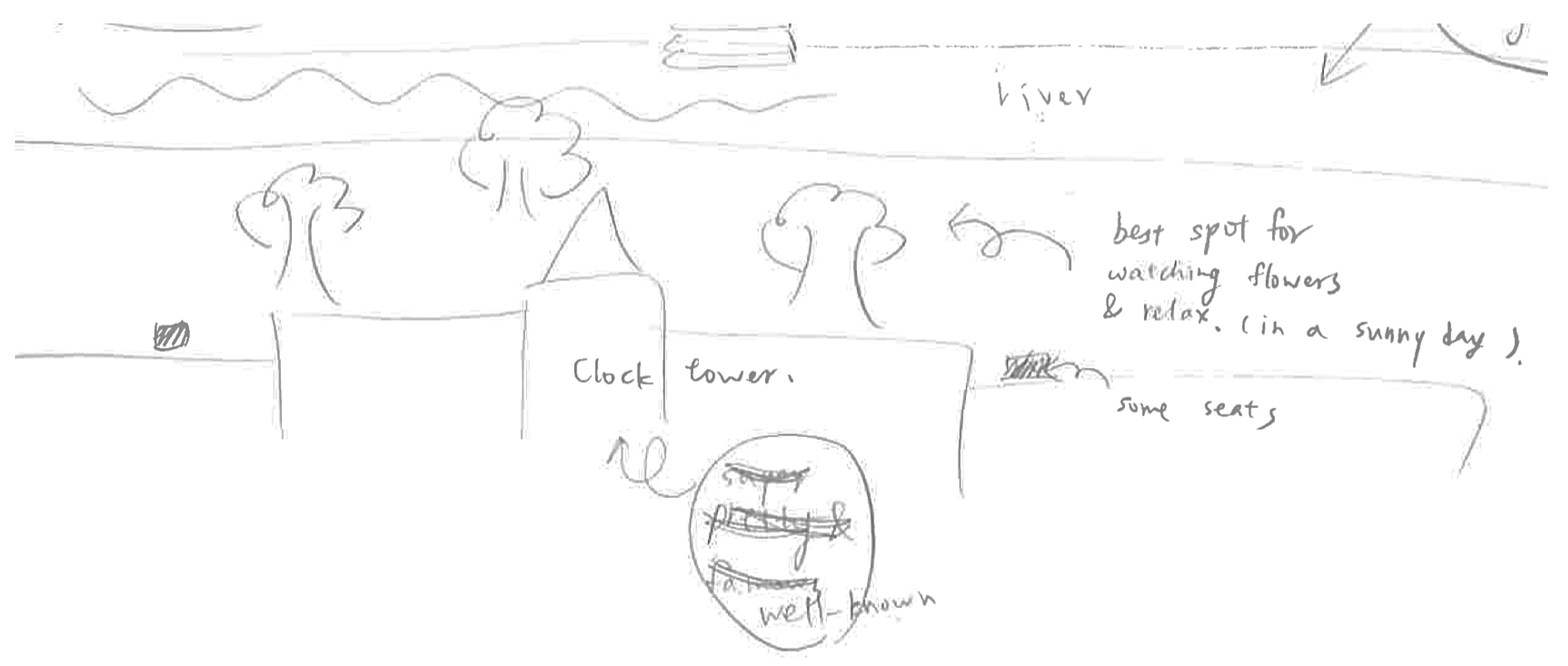

Results showed that enjoying natural landscapes on campus is the most preferred relaxation for both students and staff. Participant UA23 explained that “… because university life is always bustling and vibrant, that is why you come to parks or nature to get away and have a little breath.”Natural elements can be found on majority of mental maps including trees, lawn, and flowers (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4).

While students and staff typically spend the majority of their time indoors, participants' accounts revealed that they are more attracted to spaces with access to natural features that bring vitality and are full of change. For example, they noted how the sun moves throughout the day, creating shifting shadows, whereas interior spaces are illuminated by fluorescent lighting, especially those with small windows. Many natural features also move with the wind and change with the seasons, such as leaves on deciduous trees, while interior spaces remain lifeless, filled with computers and work documents. Participant LU2 from Lincoln University explained that spaces with natural features make her feel like there are “lots of different things happening.” She further explained:

“I like looking at the change as well as what happens in the space. … I guess part of this relaxation for me is not necessarily always stopping. I feel like I can recharge my batteries by moving through [spaces]. Like walking through here, that variation. Rather than at your office where you always got one window with nothing changes much throughout the day. … Sometimes you also notice when the flowers and the weather or the apples are coming in, so you kind of have that relationship [with the land].”

Participants from the University of Otago shared a variety of uses of the beloved Leith River and the riverbanks for relaxation. Some participants simply enjoyed the environment brought by fully landscaped riverbanks and flowering trees. According to the participants, they enjoy “getting some fresh air outside”, “hearing birdsong and water rippling”, and “seeing the changes of the season”. During spring, participants shared their own experience and observations of many campus users. Residents who live in Dunedin, and even tourists would visit the Leith riverbanks in the warmer weather when the cherry and magnolia trees were in blossom (see

Figure 5).

While most of the descriptions of 'enjoying nature' involved passive experiences, campus users also, though less frequently, found ways to actively engage with and utilise natural spaces. Participant UO80 from the University of Otago shared a story of the Leith River, “One time there was floodwater coming down at the Leith here, and people were kayaking in flood,” she said with amusement and excitement. “I mean, they are not supposed to kayaking and it is probably dangerous, but they really liked the water rapids!”.

Another form of active engagement with nature that frequently takes place in campus green spaces is playing sports. Based on participants' accounts and our observations, many campus users enjoy using flat lawn areas as small-scale sports fields. For example, the researcher observed two people practising fencing during the weekend on the Leith riverbank at the University of Otago (see

Figure 6) and some students set up a volleyball net and played at Lincoln University (see

Figure 7).

3.2. Proximity > Design Quality

Many participants pointed out that the proximity comes before the design quality of the space since campus users have limited time and resources for relaxation during working hours. For example, participant UA12 said: “I wouldn’t want to go to OBBG [Sir Owen G Glenn Building] or Albert Park. But then I would use that outdoor area [the courtyard of the School of Architecture and Planning] even though it’s not quite as nice just because I am here.” Participants such as LU12 revealed the preference for proximity through the way of identifying relaxation spaces according to the adjacent building (see

Figure 8).

Proximity is closely related to time and distance. Participants have characterised their relaxation into two categories:

3.2.1. Short-Term Break on Campus

There are three main types of spaces suitable for short-term break on campus: 1) communal space, 2) isolated space, 3) walk-scape.

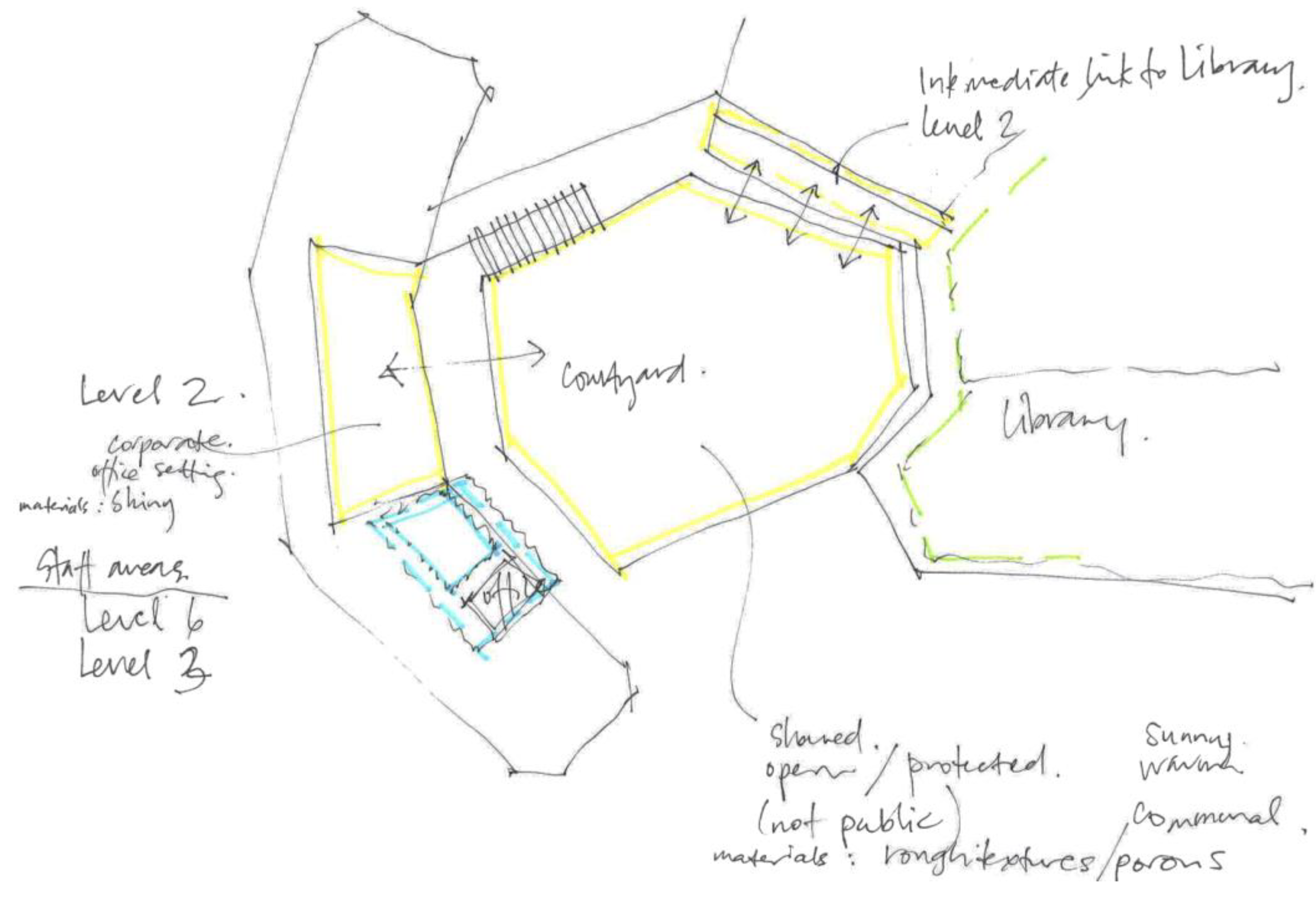

Outdoor spaces that are immediately accessible are utilised the most, even if they don't fully meet relaxation needs. Such proximity fosters and strengthens a sense of belonging, leading participants to refer to these areas as 'communal spaces' since they are usually the downstairs spaces attached to buildings. These spaces are also sought after when campus users want to refresh their minds by simply peeking out of the window. For example, participant UA17 described the courtyard of the School of Architecture and Planning as below:

“It is in the intermediate zone. The people I would encounter there are the people who would belong to this large community, the Architecture and Planning, including all their friends or acquaintances. Generally, the main public would not walk through it because it is protected by buildings and the way it is shaping. But it is quite busy and communal. “

She also showed the spatial character of the courtyard on the mental map (see

Figure 9).

- (2)

Isolated Space

While communal spaces are often busy and noisy due to heavy use, people sometimes need a moment of quiet to recover and unwind. At such times, they might choose a more isolated space that is close to them and enjoy a semi-enclosed environment, such as the 'little forest' at Lincoln University. This 'little forest' is a small, lush, vegetated area located right beside the School of Landscape Architecture building (see

Figure 10). Because of its proximity to the building, such isolated spaces can afford a quick refresh (see

Figure 11).

- (3)

Walk-scape

The last type of short-term relaxation space is not exactly a 'space' but rather the short journeys within campus, such as walking from one lecture theatre to another. The relaxation experience depends on the overall planning and design of campus streetscapes. Participant LU4 from Lincoln University explained that he enjoys walking along campus streets several times a week to catch the bus, appreciating the blossoms that turn the avenue white and pink. Participants from the University of Otago expressed their appreciation of the innovative landscape work completed recently, noting that it promotes the consistency and aesthetics of pedestrian paths, creating a more walker-friendly environment (see

Figure 12).

3.2.2. Long-Term Breaks

Participants' accounts revealed that, on campus, the lunch break is almost synonymous with long-term breaks, and every campus in this study has multiple spaces specifically designed for lunchtime relaxation. Such spaces in all three campuses are open green spaces so that they can not only accommodate food service, but also serve as centres for activities and student services (see

Figure 13). Therefore, participants characterised them as

'activity centres' and because they are versatile and full of energy, they become 'go-to' spots where people not only satisfy their physical needs but also fulfil their social needs by meeting friends or occasionally joining fun activities. Participants suggested that during lunchtime, these spaces are likely the most bustling areas on the entire campus.

Aside from lunch breaks, campus users sometimes have time to relax between classes or after finishing their work for the day. Some participants prefer to use this time to go somewhere detached from the main campus atmosphere, which they called "get-away spaces." Participants explained that campus users need to temporarily escape from their work, social roles, and stress to simply be themselves and reconnect with nature and the larger world. For example, participant LU3 referred to the magnolia garden as her "secret place" because "it is often just you there, and it is very peaceful." She further explained, "Even if other people are there, they are there for the same reason as you, so they are just looking for some quietness and some nature."

Some get-away spaces are located on campus and not far from activity centres. However, these spaces usually have stronger buffers than isolated spaces, creating a more enclosed environment. Get-away spaces on campus also offer no particular resources such as food or water, so campus users do not come out of necessity. For example, the secret garden at Lincoln University is physically close to the major and secondary activity centres. However, with a long two-storey building blocking the view of the space from the main campus street, not many people gather there (see

Figure 14).

Some get-away spaces identified by participants are located outside the main campus. By getting away from the main campus, participants stated that they can forget about work, change mood instantly, and also feel more relaxed without social pressure. All get-away spaces identified by participants that are outside the main campus are dominated by natural elements. For example, participants from the University of Auckland enjoy having a large public park, Albert Park, located on the other side of the street from the main activity centre (see

Figure 15) and participant UA5 recommended Albert Park as “an escape from the campus”.

3.3. University Staff and Relaxation

The initial intention of this study was to investigate how both students and staff use campus landscapes for relaxation. However, we found that staff were much more difficult to interview, leading to only a limited number of staff participants.

Overall, university staff are more aware of the importance of relaxation during working hours. However, they appear to be at two extremes: they either have their own daily relaxation routines, or they are too busy to leave their desks.

Participant LU5 falls into the former category, and she likes

“… doing qigong somewhere out of the way and a bit sheltered from the wind. This is not a place where you see many other people, but it is kind of a contemplative space where you can make strange movements like this because you do not have people walking by.”

Participant LU3 likes the walking journey from the Recreation Centre on campus to the magnolia garden, which takes about 20 minutes one way.

However, university staff are often absent from some of the popular relaxation spaces identified by students, such as the activity centres. While these spaces may appear to welcome all campus users, many participants—including both students and staff—pointed out that activity centres are more like "students' spaces".

In other words, students experience a sense of belonging in places like activity centres, but there are no spaces specifically designed for university staff to foster the same feeling. Some academic staff expressed a desire to enjoy their lunch breaks somewhere away from students. As participant UA4 explained:

"Sometimes, if you want to go outside the office, you want to be detached from the emails and students. Sometimes I go to the Old Government Hall and have a glass of beer. When I'm so tired, such as on a Friday afternoon, I am looking for a place to escape."

Furthermore, a significant number of university staff are absent from campus relaxation spaces simply because they are too busy to even pause and relax during lunchtime. However, they could still benefit from spending brief moments looking outside of the window, which they characterised as ‘micro-breaks’.

4. Discussion

This study investigated how campus landscape design supports relaxation during working hours for both students and staff at New Zealand universities. Through mental mapping exercises and walking interviews with 66 participants across three universities, several key themes emerged: the significant role of natural landscapes in providing relaxation; the prioritisation of proximity over design quality due to time constraints; and the underrepresentation of university staff in the use of campus relaxation spaces.

4.1. Advocate for a Biophilic Campus

The study findings conclude that biophilic experiences dominate campus users' relaxation activities, with enjoying nature identified as their most preferred way to relax. This suggests that biophilic design can enhance the health and well-being potential of built environments, promoting people's health in everyday settings. Baur [

25] and Liu et al. [

26] further suggest that campus natural spaces can contribute to student success.

The enjoyment of nature on campus is primarily associated with the "direct experience of nature," one of the biophilic experience categories defined by Kellert and Calabrese [

27]. According to participants' accounts, this direct experience of nature is multi-sensory which attracts their attention away from work.

Participants often described the sight of nature as "beautiful," enhancing the aesthetics of outdoor landscapes and providing engaging window views. This finding aligns with numerous examples of research on the pleasure and stress reduction value of a window to natural landscapes [

2][

31]. Although this study focused on landscape design strategies for outdoor spaces, participants also expressed interest in the design of interior spaces for relaxation, which is pertinent given the significant amount of time they spend indoors. Although the micro-breaks mentioned in section 3.3 fall outside the main scope of this study, it would be interesting for future research to explore the effects of interactions between interior and exterior spaces on relaxation.

Participants reported loving natural sounds such as birds chirping, wind rustling through leaves, and running water. Their preference for natural soundscapes over urban noises supports the idea that natural sounds can enhance people's experience of urban environments [

32] . They also expressed enjoyment in engaging with nature when flowers are in bloom, relishing the pleasant fragrances.

The sight and smell of nature not only provide pleasure but also encourage tactile and even gustatory engagement, like picking fruit from a tree, fostering a sense of connection with nature and place [

33]. Participants indicated that the multi-sensory experiences nature are far more interesting than the static character of interior spaces. Kaplan and Kaplan termed this "soft fascination," which captures attention away from daily concerns in an "undramatic fashion" that "permits a more reflective mode" [

34].

This multi-sensory relaxation experience aligns with Thompson's findings, where woodlands were places for children and parents to experience extraordinary, sensory, and emotional encounters [

35].

Moreover, biophilic design acknowledges the intrinsic relationship between humans and nature. It not only proposes integrating natural elements into built environments but also aims to identify design features and spatial configurations that align with our innate biophilic preferences, including those we try to avoid [

12]. To date, little has been done to incorporate biophilic design into university settings for health-promoting purposes. Peters & D'Penna discussed trends and gaps in understanding the influence of biophilic design in university settings, highlighting the complexity of these environments and urging that biophilic elements be tailored to meet users' needs. [

36]. For instance, while participants in our study identified the "little forest" as a relaxation space, considerations of safety should be addressed in future development.

4.2. Advocate for Relaxation-Oriented Campus Planning

Participants’ accounts revealed that proximity is the priority when selecting a space for relaxation, even if the design features didn't fully meet their needs. This indicates there is a fundamental difference between relaxation during working hours and relaxation during after-hours. Kaplan & Kaplan also recognised proximity as essential for nearby nature, providing convenient relaxation at people's doorsteps and facilitating a quick switch between work and rest; people tend to use what is readily available [

37].

Campus users demonstrated an even stricter perception of proximity compared to users of community open spaces. They favoured communal spaces attached to buildings—like the front or back gardens of private properties—and spaces connected to facilities. In contrast, Sugiyama et al.'s study showed adult participants' walking activities are within a 1.6 km radius [

38], which is significantly different from campus users' preferences.

This preference for immediately available relaxation spaces highlights the importance of incorporating relaxation into campus planning, enabling users to take short breaks and prevent burnout. Moreover, many studies of public open spaces focus on the walking experience, suggesting that if people intend to walk, distance is less of a barrier. Therefore, it would be interesting to explore whether distance becomes more critical for landscape users engaging in other types of relaxation activities in community spaces during non-working hours.

4.3. Advocate for Healthy Workplaces

Universities, as large employers, have the capacity to provide a caring and supportive working environment for staff [

39]. However, participants' accounts from this study reveal that campus planning and landscape design often lack attention being given to university staff. With academic work becoming increasingly demanding, campus landscapes should include spaces specifically designed for staff to relax during working hours and prevent burnout.

Geurts and Sonnentag defined recovery during working hours as internal recovery, and recovery after hours as external recovery—including after work, during weekends, or on holidays [

40]. They argued that the need for external recovery increases when internal recovery is insufficient, suggesting that internal recovery can buffer accumulated fatigue and stress. Therefore, it is essential to explore how workspaces can be designed to promote internal recovery and help maintain the 'healthy' mental status of workers.

Some studies have shown that internal recovery associated with landscapes close to workplaces can deliver mental health benefits. For example, landscape architect Stigsdotter explored employees' experiences of stress and their use of green outdoor spaces at their workplaces in nine Swedish cities. She found that accessible green spaces adjacent to workplaces can positively influence employees, even if they only look at the green view [

41].

5. Conclusions

Through investigating the uses of campus landscapes for relaxation and the preferred relaxation spaces in the University of Auckland, Lincoln University, and the University of Otago, relaxation associated with natural landscapes turned out to be the most preferred relaxation on campus. Natural landscapes on campus are not untouched ‘wild’ nature but manmade natural features. They provide spaces for ‘enjoying nature’ during short-term and long-term breaks. The enjoyment of nature on campus for relaxation recognises the health and well-being potential of biophilic design and suggests that integrating natural features in the built environments can enhance people’s health and well-being in everyday settings. In addition, the time available for relaxation is the major difference between internal and external recovery. Therefore, proximity comes before the design quality of space when choosing spaces for internal relaxation. These findings not only contribute to design healthy campus environment for live, learn, and work but also to workspace design in cities.

References

- Hall, R.; Bowles, K. Re-engineering Higher Education: The Subsumption of Academic Labour and the Exploitation of Anxiety. Workplace: A Journal for Academic Labor 2016, 28, 30–47.

- Healthy Minds Network. Available online: https://healthymindsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/HMS-Fall-2020-National-Data-Report.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Lipson, S; Lattie, E; Eisenberg, D. Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007-2017). Psychiatric Services 2018, 70(1), 60-63.

- New Zealand Union of Students’ Associations. Available online: https://kimspaincounselling.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/student-mental-health-report-kei-te-pai.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Kinman, Gail. ‘Doing More with Less? Work and Wellbeing in Academics.’ Somatechnics 2014, 4(2), 219–35.

- HEPI. Available online: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/HEPI-Pressure-Vessels-Occasional-Paper-20.pdf (29 November 2024).

- Education Suppport. Available online: https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/media/fs0pzdo2/staff_wellbeing_he_research.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Guthrie, S.; Lichten, C. A.; Van Belle, J.; Ball, S.; Knack, A.; Hofman, J. Understanding mental health in the research environment: A Rapid Evidence Assessment. Rand health quarterly 2018, 7(3), 2.

- Nicholls, H.; Nicholls, M.; Tekin, S.; Lamb, D.; Billings, J. The impact of working in academia on researchers' mental health and well-being: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. PloS one, 2022, 17(5).

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/enhanced-wellbeing/first-global-conference (accessed 29 November 2024).

- Travia, R. M.; Larcus, J. G.; Andes, S.; Gomes, P. G. Framing well-being in a college campus setting. Journal of American College Health 2020, 70(3), 758–772. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R. S.; Gilpin, L. Healing arts: Nurtrition for the soul. In Putting patients first: Designing and practicing patient-centered care; Susan B. Frampton, Philip Charmel, Patrick A. Charmel, Eds.; Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, United States, 2003, pp. 117–146.

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R. A.; Groenewegen, P. P.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P. "Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation?" Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2006, 60(7), 587-592.

- Lau, Stephen Siu Yu; Feng Yang. Introducing Healing Gardens into a Compact University Campus: Design Natural Space to Create Healthy and Sustainable Campuses. Landscape Research 2009, 34(1):55–81.

- Mt Akhir, N.; Md Sakip, S. R.; Abbas, M. Y.; Othman, N. Landscape Spatial Character: Students’ preferences on outdoor campus spaces. Asian Journal of Quality of Life 2018, 3(13), 89–97. [CrossRef]

- Mt Akhir, N.; Md Sakip, S. R.; Abbas, M. Y.; Othman, N. A Taste of Spatial Character: Quality outdoor space in campus landscape leisure setting. Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal 2017, 2(6), 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Mt Akhir, N.; Sakip, S. R. M.; Abbas, M. Y.; Othman, N. Literature survey on how planting composition influence visual preferences: A campus landscape setting. The Journal of Social Sciences Research 2018, 6, 783–790. [CrossRef]

- Holt, Elizabeth W.; Quinn K. Lombard; Noelle Best; Sara Smiley-Smith; John E. Quinn. Active and Passive Use of Green Space, Health, and Well-Being amongst University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16(3).

- McDonald-Yale, E.; Birchall, S. J. The built environment in a winter climate: improving university campus design for student wellbeing. Landscape Research 2021, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Plane, J.; Klodawsky, F. Neighbourhood amenities and health: Examining the significance of a local park. Social Science & Medicine 2013, 99(2013), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Purani, K.; Kumar, D. S. Exploring restorative potential of biophilic servicescapes. Journal of Services Marketing 2018, 32(4), 414–429. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R. S.; Simons, R. F.; Losito, B. D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M. A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology 1991, 11(3), 201–230. [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T.; J. Lee. 2008. Introduction. In Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice on Foot; Editor 1, Jo Lee Vergunst, Editor 2, Tim Ingold, Eds.; Routledge, London, 2008; pp. 1-20.

- Dabbs, James M. Making Things Visible. In Varieties of qualitative research; J. Van Maanen, J. M. Dabbs, R. R. Faulkner, Eds. SAGE Publications Ltd, Beverly Hills, California, USA, 1982, pp. 31–63.

- Baur, J. Campus community gardens and student health: A case study of a campus garden and student well-being. Journal of American College Health 2020, 70(2), 377–384. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sun, N.; Guo, J.; Zheng, Z. Campus Green Spaces, Academic Achievement and Mental Health of College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8618. [CrossRef]

- The Practice of Biophilic Design. Available online: https://www.biophilic-design.com/ (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Bardwell, L. V. Nature around the corner: Preference and use of nearby natural areas in the urban setting; University of Michigan: Michigan, USA, 1985.

- Kardan, O.; Gozdyra, P.; Misic, B.; Moola, F.; Palmer, L. J.; Paus, T.; Berman, M. G. Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large urban center. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 11610. [CrossRef]

- Kearney, A. R.; Winterbottom, D. Nearby nature and long-term care facility residents: Benefits and design recommendations. Journal of Housing For the Elderly 2006, 19(3–4), 7–28. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R. S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224(4647), 420–421. [CrossRef]

- Hedblom, M.; Heyman, E.; Antonsson, H.; Gunnarsson, B. Bird song diversity influences young people’s appreciation of urban landscapes. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 2014, 13(3), 469–474. [CrossRef]

- Beatley, Timothy. Handbook of Biophilic City Planning and Design. ISLAND PRESS: Washington DC, USA, 2016.

- Kaplan, R.; S. Kaplan. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989.

- Thompson, C. W.; Aspinall, P.; Bell, S.; & Findlay, C. “It gets you away from everyday life”: Local woodlands and community use - What makes a difference? Landscape Research 2005, 30(1), 109–146. [CrossRef]

- Peters, T.; D’Penna, K. Biophilic design for restorative university learning environments: A critical review of literature and design recommendations. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12(17), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The experience of nature: a psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, Takemi; Jacinta Francis; Nicholas J. Middleton; Neville Owen; Billie Giles-CortI. Associations between Recreational Walking and Attractiveness, Size, and Proximity of Neighborhood Open Spaces. American Journal of Public Health 2010, 100(9):1752–57.

- Tsouros, Agis D.; Gina Dowding; Jane Thompson; Mark Dooris. Health Promoting Universities: Concept, Experience and Framework for Action; World Health Organisation Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, 1998.

- Geurts, Sabine A. E.; Sabine Sonnentag. Recovery as an Explanatory Mechanism in the Relation between Acute Stress Reactions and Chronic Health Impairment. Scandinavian Journal of Work 2006, Environment and Health 32(6):482–92.

- Stigsdotter, Ulrika K. A Garden at Your Workplace May Reduce Stress. Design & Health 2004, 147–57.

Figure 1.

The main geographical location of the selected campuses (Own work, 2020).

Figure 1.

The main geographical location of the selected campuses (Own work, 2020).

Figure 2.

Participant LU15's mental map shows trees on Lincoln University campus (From participant LU15, 2018).

Figure 2.

Participant LU15's mental map shows trees on Lincoln University campus (From participant LU15, 2018).

Figure 3.

Participant LU6’s mental map shows lawn areas at Lincoln University (From participant LU6, 2018).

Figure 3.

Participant LU6’s mental map shows lawn areas at Lincoln University (From participant LU6, 2018).

Figure 4.

Participant UO21 identified a flower-watching spot on her mental map of the University of Otago (From participant UO21, 2018).

Figure 4.

Participant UO21 identified a flower-watching spot on her mental map of the University of Otago (From participant UO21, 2018).

Figure 5.

Campus users at the University of Otago enjoy natural features on the banks of the Leith River in more passive ways (Photo by author, 2018).

Figure 5.

Campus users at the University of Otago enjoy natural features on the banks of the Leith River in more passive ways (Photo by author, 2018).

Figure 6.

Two people practise fencing on the banks of the Leith River at the University of Otago during the weekend (Photo by author, 2018).

Figure 6.

Two people practise fencing on the banks of the Leith River at the University of Otago during the weekend (Photo by author, 2018).

Figure 7.

Campus users play volleyball on the Forbes Lawn at Lincoln University (Photo by author, 2018).

Figure 7.

Campus users play volleyball on the Forbes Lawn at Lincoln University (Photo by author, 2018).

Figure 8.

The importance of the context of a space at Lincoln University (From participant LU12, 2018).

Figure 8.

The importance of the context of a space at Lincoln University (From participant LU12, 2018).

Figure 9.

The spatial character of the courtyard of the School of Architecture and Planning, University of Auckland (From participant UA17, 2018).

Figure 9.

The spatial character of the courtyard of the School of Architecture and Planning, University of Auckland (From participant UA17, 2018).

Figure 10.

The location of the little forest at Lincoln University (Modified from Google Map, 2020).

Figure 10.

The location of the little forest at Lincoln University (Modified from Google Map, 2020).

Figure 11.

The view inside the little forest at Lincoln University (Photo by Author, 2018).

Figure 11.

The view inside the little forest at Lincoln University (Photo by Author, 2018).

Figure 12.

A fully paved campus streets at the University of Otago (Photo by author, 2018).

Figure 12.

A fully paved campus streets at the University of Otago (Photo by author, 2018).

Figure 13.

The main activity centres at (from top to bottom): Lincoln University, the University of Auckland, and the University of Otago (Photos by Author, 2020).

Figure 13.

The main activity centres at (from top to bottom): Lincoln University, the University of Auckland, and the University of Otago (Photos by Author, 2020).

Figure 14.

The secret garden at Lincoln University blocked by the adjacent building block (Photo by author, 2019).

Figure 14.

The secret garden at Lincoln University blocked by the adjacent building block (Photo by author, 2019).

Figure 15.

Albert Park as one get-away space for campus users at the University of Auckland (Photo by author, 2018).

Figure 15.

Albert Park as one get-away space for campus users at the University of Auckland (Photo by author, 2018).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).