Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

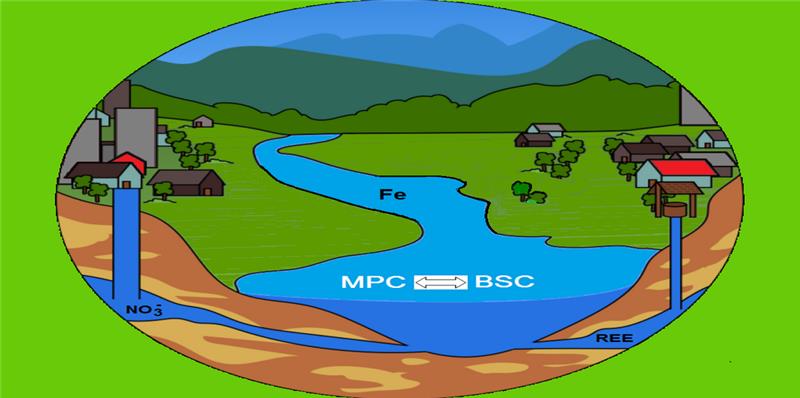

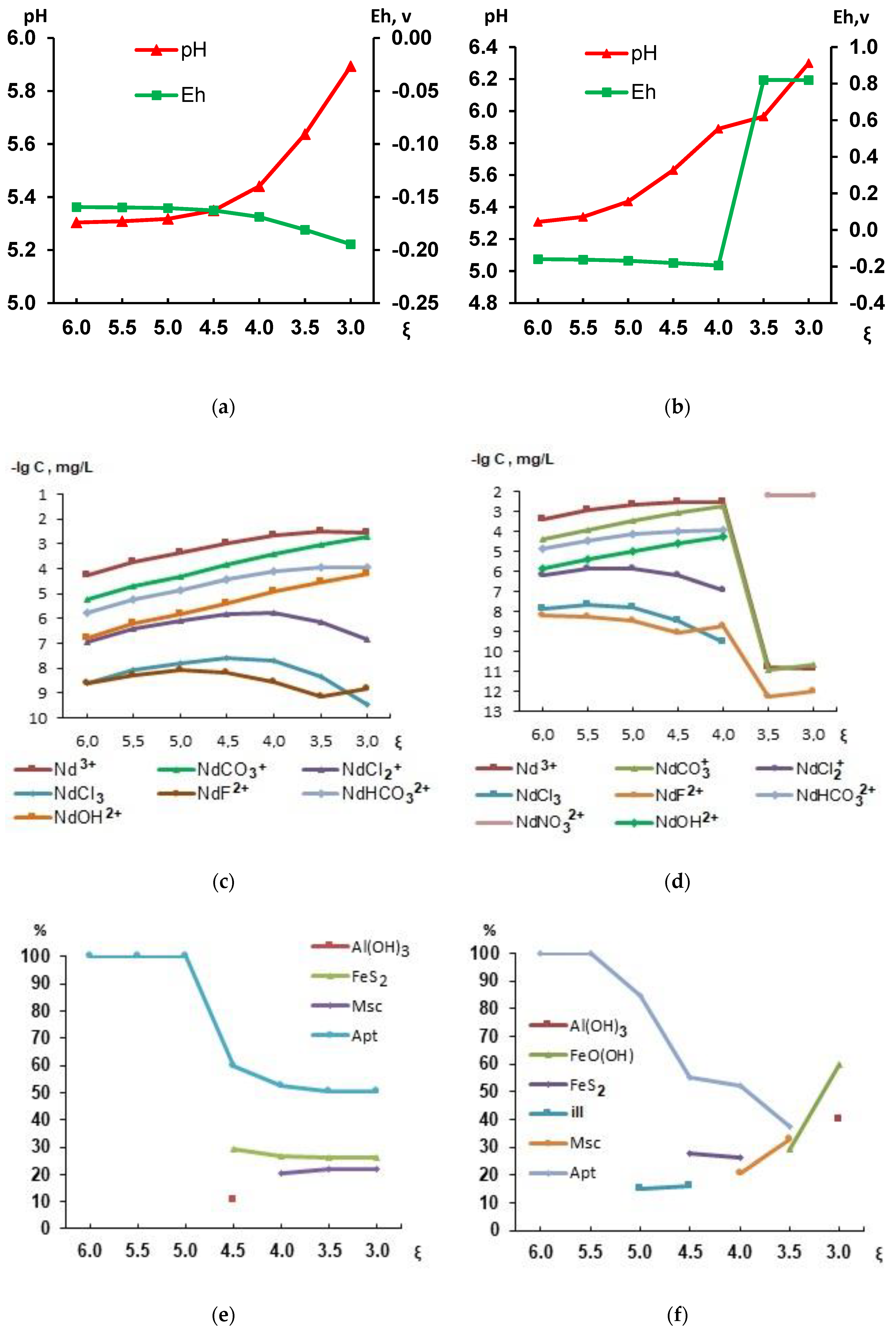

The chemical composition of surface and ground waters of the village Krasnoshchelye (Murmansk region, the Kola Peninsula) have been studied in this work. The quality of surface and ground waters of the village Krasnoshchelye is characterized taking into account the MPC and biologically significant concentration, the forms of migration of elements in the system "solution - crystalline substance" in natural waters and the human body (using the stomach as an example) have been considered. The results of the studies of drinking water in the village Krasnoshchelye indicate that the macro- (Ca, Mg, Na, K) and microelement (Co, Cu, Mn, Ni, V, Zn, Cr) composition have lower concentrations from the standpoint of biological significance for the elemental balance of a person than the recommended level of the lower limit of the BSC, except for the elements U, Th, Y. Their concentration is several times higher than their LLBSC. The forms of migration of elements and newly formed phases depend on both the acidity of the stomach and the amount of gastric juice in the human body, in the "water - gastric juice" system. These are individual characteristics of a person and his age. Well waters can contain up to 50 μg/l of REE, and changes in their migration patterns can lead to accumulation in the human body and cause diseases of the nervous system and other organs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Objects

2.2. Research Methods

2.3. Software and Thermodynamic Dataset for Modeling

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dolgikh, P.G. Geoecological features of the chemical composition of waters and bottom sediments of the Ust-Ilimsky reservoir. Abstract of the dissertation for the Candidate of Geological and mineralogical Sciences. A.P. Vinogradov Institute of Geochemistry, Irkutsk. Russia. 2024. http://www.igc.irk.ru/ru/zashchita, (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Ushakova, E.S. Ecogeochemistry of aquatic ecosystems of urbanized territories of the northern Caspian Sea. Dissertation for candidate of geological and mineralogical sciences. Tomsk polytechnic university. Tomsk. Russia. 2024. https://portal.tpu.ru/council/indcouncils/6080/worklist (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Kayukova, E.P.; Filimonova, E.A. Quality of fresh groundwater of the Crimean Mountains (the Bodrak River Basin). Moscow University Bulletin. Series 4. Geology 2022, 1, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SanPiN 2.1.3684-21. Sanitary Rules and Standards. Hygienic standards and requirements for ensuring the safety and (or) harmlessness of environmental factors for humans; Moscow, Russia, 2021.

- Goncharuk, V.V.; Zui, O.V.; Melnik, L.A.; Mishchuk, N.A.; Nanieva, A.V.; Pelishenko, A.V. Assessment of the physiological adequacy of drinking water by biotesting. Chemistry for Sustainable Development 2021, 1, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SanPiN 2. 1.4.1116-02. Sanitary Rules and Standards. Drinking water. Hygienic requirements for the quality of water packaged in containers. Quality control; Ministry of Health of Russia: Moscow, Russia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sanitary norms and rules Requirements for the physiological usefulness of drinking water; Minsk, Belarus, 2012.

- DSTU 7525-2014. Drinking water. Requirements and methods of quality control; Ministry of Economic Development of Ukraine: Kiev, Ukraine, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Krainov, S.R.; Ryzhenko, B.N.; Shvets, V.M. Geochemistry of groundwater. Theoretical, applied and environmental aspects; CentrLitNefteGaz: Moscow, Russia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalsky, V.V. Geochemical Ecology; Nauka Publ.: Moscow, Russia, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Barvish, M.V.; Schwartz, A.A. A new approach to the assessment of the microcomponent composition of underground waters used for drinking water supply. Geoecology 2000, 5, 467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Linnik, P.N.; Nabivanets, B.I. Forms of Metal Migration in Fresh Surface Waters; Gidrometeoizdat: Leningrad, Russia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Linnik, P.N.; Zhezherya, V.A. Aluminum in surface water of ukraine: concentrations, migration forms, distribution among abiotic components. Water Resources 2013, 40, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandimirov, S.S.; Pozhilenko, V.I.; Mazukhina, S.I.; Drogobuzhskaya, S.V.; Shirokaya, A.A.; Tereshchenko, P.S. Chemical Composition of Natural Waters of the Lovozero Massif, Russia. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 8, 4307–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazukhina, S.I.; Sandimirov, S.S.; Drogobuzhskaya, S.V. Physiological adequacy assessment of potable water in Lovozero district, Murmansk region of Russia. In Biogenic—Abiogenic Interactions in Natural and Anthropogenic Systems; Frank-Kamenetskaya, O.V., Vlasov, D.Yu., Panova, E.G., Alekseeva, T. V., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Earth and Environmental Sciences, Switzerland, 2022, pp.617-633. [CrossRef]

- Mazukhina, S.I.; Мазухина, С.И.; Дрoгoбужская, С.В.; Сандимирoв, С.С.; Маслoбoев, В.А. Features of changes in chemical composition of drinking water as a result of water treatment (Lovozero, Kola peninsula). Bulletin of the Tomsk Polytechnic University. Geo Аssets Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Mazukhina, S.; Drogobuzhskaya, S.; Sandimirov, S.; Masloboev, V. Effect of Water Treatment on the Chemical Composition of Drinking Water: a Case of Lovozero, Murmansk region, Russia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materials for the state report "On the state of epidemiological well-being of the population in the Murmansk region were prepared by a working group of specialists: sanitary-2022". Rospotrebnadzor: Murmansk, Russia, 2023. https://51.rospotrebnadzor.ru (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Materials for the state report "On the state of the sanitary and epidemiological well-being of the population in the Murmansk region in 2023". Rospotrebnadzor: Murmansk, Russia, 2024. 214 p. https://51.rospotrebnadzor.ru. (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Karpov, I.K.; Chudnenko, K.V.; Kulik, D.A.; Bychinskii, V.A. The convex programming minimization of five thermodynamic potentials other than Gibbs energy in geochemical modeling. Am. J. Sci. 2002, 302, 281–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudnenko, K.V. Thermodynamic Modeling in Geochemistry: Theory, Algorithms, Software, Applications; Akadem Publishing House “Geo”: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, R.; Prausnic, D.; Shervud, T. Gases and Liquids Properties; Him-ija: Leningrad, Russia, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, R.C.; Prausnitz, J.M.; Sherwood, T.K. The Properties of Gases and Liquids; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Shock, E.L.; Helgeson, H.C. Calculation of the thermodynamic and transport properties of aqueous species at high pressures and temperatures: Correlation algorithms for ionic species and equation of state predictions to 5 kb and 100°C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1988, 52, 2009–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokokawa, H. Tables of thermodynamic properties of inorganic compounds. J. Nat. Chem. Lab. Indust. 1988, 83, 27–121. [Google Scholar]

- Shock, E.L.; Helgeson, H.C.; Sverjensky, D.A. Calculation of the thermodynamic and transport properties of aqueous species at high pressures and temperatures: Standard partial molal properties of inorganic neutral species. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1989, 53, 2157–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.W.; Oelkers, E.H.; Helgeson, H.C. SUPCRT92: Software package for calculating the standard molal thermodynamic properties of mineral, gases, aqueous species, and reactions from 1 to 5000 bars and 0 to 100 ◦C. Comput. Geosci. 1992, 18, 899–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 28. Robie, R.A.; Hemingway, B.S. Thermodynamic Properties of Minerals and Related Substances at 298.15 K and 1 Bar (105 Pascals) Pressure and at Higher Temperatures; United States Geological Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 1995.

- Shock, E.L.; Sassani, D.C.; Willis, M.; Sverjensky, D.A. Inorganic species in geologic fluids: Correlation among standard molal thermodynamic properties of aqueous ions and hydroxide complexes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1997, 61, 907–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokarev, I.V. Isotope reconstruction of the origin, evolution and assessment of the current state of water and ice objects. Dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Geological and Mineralogical Sciences. St Petersburg University, Saint Petersburg, 2024, V.2, p.48. https://crust.ru/newsfullarchive.html. (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Toolabi, A.; Bonyadi, Z.; Paydar, M.; Najafpoor, A.A.; Ramavandi, B. Spatial distribution, occurrence, and health risk assessment of nitrate, fluoride, and arsenic in Bam groundwater resource, Iran. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 12, 100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazukhina, S.I.; Drogobuzhskaya, S.V.; Ionov, N.V.; Rybachenko, V.V. Analysis of the chemical composition of tap water of Murmansk. In Ecological Problems of the Northern Regions and Ways to Their Solution. Proceedings of the VIII Russian Scientific Conference with international participation, Apatity, Russia, 24–29 June 2024; Makarov D.V., Eds. Publishing house of the FIS of the KSC RAS: Apatity, Russia, 2024; pp. 279–280. [Google Scholar]

- Mazukhina, S.I.; Chudnenko, K.V.; Tereshchenko, P.S.; Drogobuzhskaya, S.V. Formation of Concretions in Human Body under the Influence of the State of Environment of the Kola Peninsula: Thermodynamic Modeling. Chemistry for Sustainable Development 2020, 28, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazukhina, S.I.; Maksimova, V.V.; Chudnenko, K.V.; Masloboev, V.A.; Sandimirov, S.S.; Drogobuzhskaya, S.V.; Tereshchenko, P.S.; Senzhenko, V.I.; Gudkov, A.V. Water Quality of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation: Physico-Chemical Modeling of Water Formation, Forms of Migration of Elements, Influence on the Human Body; Publishing house of the FIS of the KSC RAS: Apatity, Russia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Belisheva, N.K.; Drogobuzhskaya, S.V. Rare Earth Element Content in Hair Samples of Children Living in the Vicinity of the Kola Peninsula Mining Site and Nervous System Diseases. Biology 2024, 13, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.L.; Zhu, W.Z.; Gao, Z.H.; Meng, Y.X.; Peng, R.L.; Lu, G.C. Distribution characteristics of rare earth elements in children’s scalp hair from a rare earths mining area in Southern China. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2004, 39, 2517–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Huang, L. Toxic Effects of Rare Earth Elements on Human Health: A Review. Toxics 2024, 12, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskalev, Y.I. Mineral Exchange. Medicine: Moscow, Russia, 985. 288 p.

| Indicator | River Ponoy | Well (Figure 3, point 5) | Indicator | river Ponoy | Well (Figure 3, point 5) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | RM | AD | RM | AD | RM | AD | RM | |||||

| mg/L | mg/L | |||||||||||

| Eh | 0.845 | 0.8256 | Ba total | 0.0079 | 7.86×10-3 | 0.0373 | 0.0373 | |||||

| pH | 6.38 | 6.39 | 6.66 | 6.68 | Ba2+ | 7.86×10-3 | 0.0373 | |||||

| Is* | 0.00064 | 0.00180 | BaCO3 | 3.29×10-7 | 2.78×10-6 | |||||||

| Al total | 0.045 | 0.0450 | 0.098 | 0.0980 | BaCl+ | 1.80×10-7 | 3.70×10-6 | |||||

| Al(OH)2+ | 2.04×10-3 | 3.84×10-3 | BaOH+ | 3.61×10-10 | 3.26×10-9 | |||||||

| Al(OH)2F | 0.0804 | 0.0378 | Si total | 5.71 | 5.71 | 3.06 | 3.06 | |||||

| Al(OH)2F2- | 8.56×10-5 | 1.08×10-5 | SiO2 | 4.06 | 2.17 | |||||||

| AlO2- | 8.20×10-3 | 5.79×10-2 | HSiO3- | 2.92×10-3 | 3.09×10-3 | |||||||

| HAlO2 | 1.26×10-2 | 4.53×10-2 | H4SiO4 | 13.0 | 6.99 | |||||||

| Al(OH) 2+ | 9.23×10-4 | 9.27×10-4 | Sr total | 0.017 | 0.0170 | 0.041 | 0.0410 | |||||

| Al(OH)3 | 0.0109 | 3.93×10-2 | Sr2+ | 0.0169 | 0.0406 | |||||||

| Al(OH)4- | 0.0112 | 7.93×10-2 | SrOH+ | 1.40×10-9 | 6.15×10-9 | |||||||

| Al3+ | 3.03×10-5 | 1.66×10-5 | SrCO3 | 6.59×10-7 | 5.81×10-6 | |||||||

| AlSO4+ | 1.23×10-7 | 2.33×10-7 | SrHCO3+ | 1.47×10-4 | 6.94×10-4 | |||||||

| Ca total | 4.23 | 4.23 | 15.0 | 15.00 | SrCl+ | 7.98×10-7 | 8.29×10-6 | |||||

| Ca2+ | 4.18 | 14.80 | SrF+ | 1.77×10-7 | 1.04×10-7 | |||||||

| CaOH+ | 1.23×10-6 | 8.14×10-6 | Cd total | 5.0×10-6 | 5.00×10-6 | 5.0×10-6 | 5.00×10-6 | |||||

| CaCO3 | 1.50×10-3 | 9.24×10-3 | Cd2+ | 4.97×10-6 | 4.87×10-6 | |||||||

| Ca(HCO3)+ | 8.73×10-2 | 0.28 | CdCl+ | 3.98×10-8 | 1.69×10-7 | |||||||

| CaHSiO3+ | 4.62×10-6 | 1.64×10-5 | CdO | 7.22×10-14 | 2.43×10-13 | |||||||

| CaCl+ | 2.40×10-4 | 3.66×10-3 | CdOH+ | 8.06×10-10 | 1.45×10-9 | |||||||

| CaCl2 | 1.09×10-8 | 7.35×10-7 | Ni total | 0.00030 | 3.00×10-4 | 0.00028 | 2.80×10-4 | |||||

| CaF+ | 1.84×10-4 | 1.59×10-4 | Ni2+ | 3.00×10-4 | 2.80×10-4 | |||||||

| CaSO4 | 0.0336 | 0.429 | NiOH+ | 1.01×10-8 | 1.73×10-8 | |||||||

| В total | 0.0004 | 4.40×10-4 | 0.0042 | 4.22×10-3 | Pb (0.01) | 5.6×10-5 | 5.60×10-5 | 0.00013 | 1.30×10-4 | |||

| B(OH)3 | 2.51×10-3 | 0.0241 | Pb2+ | 2.15×10-5 | 3.29×10-5 | |||||||

| BO2- | 2.10×10-6 | 3.93×10-5 | PbOH+ | 3.73×10-5 | 1.05×10-4 | |||||||

| Fe total | 2.21 | 2.21 | 0.263 | 0.263 | PbO | 9.00×10-10 | 4.73×10-9 | |||||

| Fe2+ | 5.53×10-9 | 2.49×10-10 | PbCl+ | 4.18×10-8 | 2.77×10-7 | |||||||

| FeSO4+ | 7.48×10-8 | 6.68×10-9 | Cu total | 0.00060 | 6.00×10-4 | 0.00150 | 1.50×10-3 | |||||

| Fe(OH)3 | 0.148 | 0.0242 | Cu+ | 7.07×10-16 | 3.23×10-15 | |||||||

| Fe(OH)4- | 1.91×10-3 | 6.18×10-4 | Cu2+ | 5.87×10-4 | 1.44×10-3 | |||||||

| FeOH2+ | 2.50×10-3 | 1.14×10-4 | CuCl+ | 1.43×10-7 | 1.52×10-6 | |||||||

| FeOH+ | 5.97×10-12 | 4.97×10-13 | CuOH+ | 1.58×10-5 | 7.13×10-5 | |||||||

| FeO+ | 1.61 | 0.137 | CuF+ | 1.62×10-7 | 9.76×10-8 | |||||||

| FeSO4 | 2.44×10-11 | 3.88×10-12 | CuCl2- | 1.01×10-12 | 1.48E-16 | |||||||

| HFeO2 | 1.39 | 0.228 | HCuO2- | 1.36×10-12 | 2.18×10-11 | |||||||

| FeO2- | 6.23×10-4 | 2.02×10-4 | P total | 0.0020 | 2.00×10-3 | 0.0010 | 1.00×10-3 | |||||

| FeCl+ | 3.91×10-13 | 7.47×10-14 | PO43- | 8.78×10-10 | 1.51×10-9 | |||||||

| FeF+ | 1.29×10-12 | 1.39×10-14 | HPO42- | 8.13×10-4 | 7.04×10-4 | |||||||

| FeF2+ | 1.26×10-6 | 7.67×10-9 | H2PO4- | 5.44×10-3 | 2.42×10-3 | |||||||

| F- | 0.144 | 0.125 | 0.0409 | 0.0318 | Co total | 0.00011 | 1.10×10-4 | 0.00028 | 2.80×10-4 | |||

| HF | 7.29×10-5 | 9.52×10-6 | Co2+ | 1.10×10-4 | 2.80×10-4 | |||||||

| HF2- | 2.14×10-10 | 7.15×10-12 | CoO | 6.33×10-11 | 5.52×10-10 | |||||||

| K total | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.67 | 3.67 | CoCl+ | 4.12×10-8 | 4.54×10-7 | |||||

| K+ | 1.00 | 3.67 | HCoO2- | - | 5.19×10-16 | |||||||

| KCl | 3.06×10-7 | 4.96×10-6 | CoOH+ | 2.26×10-8 | 1.06×10-7 | |||||||

| KHSO4 | 6.87×10-13 | 4.80×10-12 | Cl total | 2.27 | 2.27 | 10.22 | 10.2 | |||||

| KOH | 8.06×10-9 | 5.73×10-8 | Cl- | 2.27 | 10.2 | |||||||

| KSO4- | 5.01×10-4 | 6.93×10-3 | HCl | 1.96×10-7 | 4.63×10-7 | |||||||

| Mg total | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.47 | 1.47 | Zr total | 0.00018 | 1.75×10-4 | 0.00079 | 7.90×10-4 | |||

| Mg2+ | 1.06 | 1.44 | HZrO3- | 1.37×10-4 | 8.08×10-4 | |||||||

| MgOH+ | 5.74×10-6 | 1.49×10-5 | ZrO2 | 1.16×10-4 | 3.57×10-4 | |||||||

| MgCO3 | 2.43×10-4 | 5.89×10-4 | U total | 0.00006 | 6.40×10-5 | 0.00008 | 7.90×10-5 | |||||

| Mg(HCO3)+ | 2.96×10-2 | 3.70×10-2 | HUO4- | 1.95×10-7 | 4.70×10-7 | |||||||

| MgCl+ | 1.19×10-4 | 7.00×10-4 | UO22+ | 3.33×10-7 | 1.23×10-7 | |||||||

| MgF+ | 2.69×10-4 | 9.00×10-5 | UO2OH+ | 3.90×10-6 | 2.64×10-6 | |||||||

| MgSO4 | 1.63×10-2 | 8.02×10-2 | UO42- | 4.95×10-15 | 2.33×10-14 | |||||||

| MgHSiO3+ | 3.02×10-6 | 4.19×10-6 | UO3 | 7.25×10-5 | 9.17×10-5 | |||||||

| Mn total | 0.033 | 0.0330 | 0.0110 | 1.10×10-2 | Li total | 0.0032 | 3.20×10-3 | 0.00023 | 2.30×10-4 | |||

| Mn2+ | 0.0329 | 1.09×10-2 | Li+ | 3.20×10-3 | 2.30×10-4 | |||||||

| MnOH+ | 1.62×10-6 | 1.02×10-6 | LiOH | 4.18×10-10 | 5.62×10-11 | |||||||

| MnO | 6.41×10-12 | 7.84×10-12 | Ce total | 0.00042 | 4.23×10-4 | 0.00513 | 5.13×10-3 | |||||

| HMnO2- | - | - | Ce3+ | 1.42×10-11 | 2.16×10-12 | |||||||

| MnSO4 | 1.32×10-4 | 1.59×10-4 | CeNO32+ | 6.09×10-4 | 7.40×10-3 | |||||||

| MnF+ | 2.13×10-6 | 1.73×10-7 | CeSO4+ | 1.71×10-12 | 8.11×10-13 | |||||||

| MnCl+ | 2.17×10-6 | 3.12×10-6 | CeOH2+ | 8.14×10-14 | 2.20×10-14 | |||||||

| CO32- | 4.64×10-3 | 4.33×10-3 | Cr total | 0.00008 | - | 0.00017 | - | |||||

| HCO3- | 46.2 | 2.01 | CrO42- | 7.23×10-5 | 2.31×10-4 | |||||||

| HSO4- | 6.65×10-5 | 1.22×10-4 | HCrO4- | 1.07×10-4 | 1.49×10-4 | |||||||

| SO42- | 1.95 | 1.91 | 7.52 | La total | 0.00031 | 3.05×10-4 | 0.00389 | 3.88×10-3 | ||||

| HNO3 | 4.87×10-9 | 2.12×10-7 | La3+ | 1.19×10-11 | 1.90×10-12 | |||||||

| NO3- | 0.35 | 0.346 | 3.11 | LaCO3+ | 8.67×10-12 | 2.11×10-12 | ||||||

| Na+ | 2.82 | 2.82 | 7.64 | 7.64 | LaF2+ | 5.14×10-13 | 1.89×10-14 | |||||

| NaOH | 4.98×10-8 | 2.68×10-7 | LaCl2+ | 1.71×10-15 | 1.09×10-15 | |||||||

| NaAlO2 | 2.31×10-7 | 4.42×10-6 | LaNO32+ | 4.41×10-4 | 5.62×10-3 | |||||||

| NaCl | 7.34×10-5 | 8.60×10-4 | LaOH2+ | 4.11×10-14 | 1.17×10-14 | |||||||

| NaF | 3.20×10-6 | 2.16×10-6 | LaSO4+ | 1.44×10-12 | 7.18×10-13 | |||||||

| NaSO4- | 1.38×10-3 | 1.36×10-2 | Zn2+ | 7.00×10-4 | 6.85×10-4 | 3.10×10-3 | 2.98×10-3 | |||||

| NaHSiO3 | 3.62×10-5 | 1.04×10-4 | ZnOH+ | 1.82×10-5 | 1.46×10-4 | |||||||

| O2 | 8.04 | 4.96 | ZnCl+ | 7.78×10-8 | 1.41×10-6 | |||||||

| CO2 | 14.7 | 6.88 | ZnF+ | 7.90×10-8 | 8.21×10-8 | |||||||

| VO2+ | 7.71×10-8 | 0.00021 | 6.53×10-9 | Y total | 0.00037 | 3.65×10-4 | 0.0040 | 3.98×10-3 | ||||

| VO43- | 0.0012 | 7.55×10-11 | 1.02×10-10 | Y3+ | 3.55×10-4 | 3.78×10-3 | ||||||

| HVO42- | 6.95×10-4 | 4.55×10-4 | YO+ | 3.50×10-8 | 1.22×10-6 | |||||||

| H3VO4 | 1.09×10-4 | 1.80×10-5 | YOH2+ | 1.24×10-5 | 2.35×10-4 | |||||||

| Nd | 0.00033 | 3.25×10-4 | 0.00478 | 4.78×10-3 | Pr | 0.00006 | 6.25×10-5 | 0.00106 | 1.06×10-3 | |||

| Nd3+ | 7.71×10-12 | 5.93×10-12 | Pr3+ | 2.08×10-12 | 4.41×10-13 | |||||||

| NdNO32+ | 4.65×10-4 | 6.84×10-3 | PrNO32+ | 9.00×10-5 | 1.52×10-3 | |||||||

| Object | ToC | MnO2 | FeO(OH) | Msc | Apt | Mnt | SiO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well | |||||||

| mol | 20 | 2.00×10-4 | 4.71×10-3 | 2.08×10-7 | 9.86×10-6 | 1.56×10-3 | - |

| % | 1.72 | 41.29 | 0.01 | 0.49 | 56.5 | - | |

| mol | 3 | 2.00×10-4 | 4.71×10-3 | 1.21×10-3 | 9.93E×10-6 | - | 0.0481 |

| % | 0.44 | 10.7 | 14.84 | 0.13 | - | 73.89 | |

| Ponoy | |||||||

| mol | 20 | 6.01×10-4 | 0.0395 | - | 5.31×10-6 | 7.15×10-4 | 0.0511 |

| % | 0.76 | 50.91 | - | 0.04 | 3.81 | 44.48 | |

| mol | 3 | 6.01×10-4 | 0.0395 | 4.87×10-7 | 9.93×10-6 | - | 0.0481 |

| % | 0.42 | 28.21 | - | 0.13 | - | 69.25 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).