1. Introduction

Intrinsically disordered proteins and protein regions (IDPs, IDPRs)

1 challenge the classical structure-function paradigm of proteins, which posits that a protein's specific biological function is inherently linked to its unique, stable three-dimensional (3D) structure (Trivedi and Nagarajaram, 2022). This paradigm, deeply rooted in Anfinsen's thermodynamic hypothesis, has served as a foundational principle of structural biology (Dishman and Volkman, 2018). However, IDPs defy this classical view by existing as highly dynamic ensembles of interconverting conformations rather than adopting a single, stable structural state under physiological conditions (Kulkarni et al., 2022). The intrinsic disorder observed in IDPs is a consequence of their distinctive amino acid compositions. These proteins are typically enriched in polar and charged residues—such as serine, glutamine, and lysine—and are depleted in hydrophobic residues, which are essential for forming the stable hydrophobic cores characteristic of folded proteins (Uversky, 2013). The absence of such hydrophobic cores prevents the stabilization of a defined 3D structure, resulting in an ensemble of flexible, unstructured conformations (Orosz and Ovádi, 2011). This structural plasticity allows IDPs to explore a wide conformational landscape, which, in turn, enables functional versatility and adaptability. The dynamic nature of IDPs is central to their functional repertoire, particularly in cellular processes requiring molecular flexibility and promiscuous interactions (Aftab et al., 2024). IDPs mediate interactions with multiple molecular partners through mechanisms such as conformational selection and induced fit, enabling high specificity despite their structural heterogeneity (Arai et al., 2024). This adaptability is often modulated by post-translational modifications (PTMs), which act as molecular switches that fine-tune their interactions and activity (Bah and Forman-Kay, 2016). IDPs frequently serve as hubs or scaffolds in signal transduction pathways, where they coordinate the assembly and function of multi-protein complexes (Wright and Dyson, 2015). Their structural flexibility facilitates the simultaneous or sequential binding of diverse signaling molecules, ensuring efficient signal propagation and integration (Su et al., 2024). This ability to accommodate multiple partners is critical for forming dynamic, reversible interactions that are responsive to cellular stimuli (Kulkarni et al., 2021). In transcriptional regulation, IDPs play pivotal roles by modulating transcription factors and assembling transcriptional complexes (Tsafou et al., 2018). Their structural flexibility enables interactions with diverse DNA sequences and protein partners, facilitating dynamic responses to developmental and environmental cues (Bugge et al., 2020; Salladini et al., 2020).

However, the intrinsic flexibility presents significant challenges for traditional methods of structure determination, particularly in accurately sampling the diverse conformational landscapes of these proteins (Roca-Martinez et al., 2022). Conventional structural biology techniques, such as X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy, rely on the ability to capture proteins in a single, well-defined conformation to generate high-resolution structural data (Evans et al., 2023). The dynamic and heterogeneous nature of IDPs precludes the formation of the ordered crystals required for X-ray diffraction studies, as their lack of a stable tertiary structure prevents them from adopting the uniform conformations necessary for crystal lattice formation (Smyth and Martin, 2000). Moreover, techniques like nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), while more suitable for studying dynamic systems, face limitations when applied to IDPs. NMR spectroscopy can provide information on the ensemble-averaged properties of IDPs, but the rapid interconversion between conformations leads to broad and overlapping signals, complicating spectral interpretation and making it difficult to resolve individual conformational states (Maiti et al., 2024). Similarly, SAXS yields low-resolution data that represent an average overall conformation present in solution, which can obscure transient or low-population states that may be functionally relevant (Brosey and Tainer, 2019).

Traditional MD simulations, while valuable for exploring protein dynamics, are often insufficient on their own to fully capture the conformational landscapes of IDPs due to practical limitations in sampling efficiency and force field accuracy (Zhu et al., 2024a). Beyond these limitations, the sheer scale of the conformational space accessible to IDPs poses another challenge. As a result, there has been a burgeoning interest in leveraging AI-based methodologies to efficiently sample the conformational space in IDPs (Gupta et al., 2022). The advent of a data-rich era in molecular and structural biology, fueled by the exponential growth of high-throughput experimental techniques and computational simulations (Velankar et al., 2021), has provided unprecedented opportunities for the development of data-driven approaches to tackle longstanding challenges in the study of protein structural dynamics (Mura et al., 2018). In this data-rich landscape, DL approaches have demonstrated significant potential in modeling complex biological systems due to their ability to learn intricate, non-linear relationships from large datasets without explicit programming of physical laws (Patel and Tewari, 2022).

In this review, we summarize recent advancements in the application of DL methods to model the conformational ensembles in IDPs (Erdős and Dosztányi, 2024). By examining various DL architectures employed for the purpose, we highlight their potential in capturing the structural dynamics of IDPs that are crucial for understanding their multifaceted biological functions and roles in diseases (Brotzakis et al., 2023) (Ruzmetov et al., 2024). Additionally, we explore the integration of experimental data with computational models, emphasizing how interdisciplinary efforts are enhancing our ability to characterize IDP behavior (Zhang et al., 2023b; Liu et al., 2024). Furthermore, we also discuss the challenges faced by these generative models in the context of conformational sampling in IDPs and how incorporating physics-based constraints can help in overcoming the energy landscape in IDPs (Guan et al., 2024; Jing et al., 2024).

2. Limitations and Latest Advents of Molecular Dynamic Simulations in Sampling Conformational Ensembles in IDPs

MD simulations have been a fundamental tool in computational structural biology for decades, allowing researchers to explore the atomic-level motions of proteins and other biomolecules over time. In the context of globular proteins, MD simulations can provide detailed insights into the structural dynamics and conformational changes, often pertaining to their function (Hollingsworth and Dror, 2018). However, when applied to IDPs, MD faces several inherent limitations. One of the primary challenges is the sheer size and complexity of the conformational space that IDPs can explore (Bhattacharya and Lin, 2019). IDPs, by definition, do not adopt a single, well-defined structure; instead, they exist as an ensemble of nonconvertible conformations (Bandyopadhyay and Basu, 2020; Kulkarni et al., 2022). Capturing this diversity requires simulations that span long timescales—often microseconds (μs) to milliseconds (ms) — to adequately sample the full range of possible states. Furthermore, MD simulations often start production runs with different random seeds when assigning initial velocities to atoms, typically using a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, to ensure that the results are not biased by specific initial conditions (Roy et al., 2014, 2015). Such simulations are computationally intensive, requiring significant computational resources and time, which limits the practicality of MD for large-scale studies of IDPs (Shrestha et al., 2021). Moreover, even with extensive simulation times, MD may fail to sample rare conformations that are biologically relevant but occur only transiently. These rare states can be crucial for the functional role of IDPs in processes such as protein-protein interactions or the formation of transient complexes (Han et al., 2017; Roy et al., 2022). The inherent bias of MD simulations towards sampling states near the initial conditions further complicates the accurate representation of the full conformational ensemble (Sullivan and Weinzierl, 2020). To overcome these challenges, researchers have developed specialized MD techniques tailored to IDPs. Coarse-grained (CG) models, for instance, reduce the level of detail by grouping atoms into larger moieties, thereby lowering computational costs and enabling the simulation of longer timescales, which are critical for capturing the full range of IDP conformations (Hu et al., 2024). Additionally, enhanced sampling methods, such as replica exchange MD (REMD) and metadynamics, are designed to overcome the sampling bias of traditional MD by facilitating the exploration of the entire energy landscape (Han et al., 2017). These methods are particularly effective in identifying and characterizing rare conformational states that play key roles in the biological functions of IDPs (Gong et al., 2021).

A significant obstacle in MD simulations arises from the lack of a precise energy function to guide these methods, particularly in the context of IDPs. Traditional force fields, which are often optimized for globular proteins, may not adequately capture the unique dynamic properties of IDPs, leading to biased sampling and incomplete exploration of conformational space (Schlick et al., 2021). Traditional force fields, primarily developed and optimized for globular proteins, such as AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, and OPLS - all of which have an inherent bias towards well-defined secondary and tertiary structures (Guvench and MacKerell, 2008). To overcome this bias, researchers have developed IDP-specific force fields that are better suited to model the unique dynamic properties of disordered proteins (Mu et al., 2021). These force fields, such as CHARMM36m (Huang et al., 2017), ff14IDPSFF (Song et al., 2017), a99SB-disp (Robustelli et al., 2018), ESFF1 (Song et al., 2020), among others, have been designed with modified parameters (assigning appropriate weightages to the terms) to better account for the lack of stable secondary structures replaced by the malleable, fluid-like nature of IDPs. For example, IDP-specific force fields may reduce the bias towards forming helices and sheets, allowing the simulations to more accurately reflect the true conformational flexibility of IDPs (Song et al., 2020). AWSEM-IDP and MOFF are some CG force fields that were developed for IDP-specific simulation applications (Wu et al., 2018; Latham and Zhang, 2019). Additionally, the choice of solvent model can be just as important as the choice of force field (Fischer et al., 2024). Explicit solvent models like TIP4P/2005 or SPC/E are often preferred because they provide a more accurate representation of water’s dielectric properties and hydrogen-bonding capabilities, which are essential for capturing the highly dynamic and flexible nature of IDPs (Mu et al., 2021). Implicit solvent models, like ABSINTH (Choi and Pappu, 2019), use additional potentials rather than simulated models of water molecules to describe the influence of solvent (Mu et al., 2021; Janson et al., 2023). Addressing post-translational modifications (PTMs) are crucial in conformational sampling of IDPs because they can induce localized changes in charge distribution, hydrophobicity, and steric hindrance, which significantly alter the conformational landscape. These modifications can shift the equilibrium between different conformational states, wherein changes in surface properties modulate binding affinities with molecular partners. They can further create or disrupt transient structural motifs, thereby directly influencing the functional dynamics of IDPs in cellular processes. While several force fields, such as AMBER and CHARMM, have incorporated parameters for common PTMs like phosphorylation and glycosylation, these modifications are not yet fully optimized for IDPs (Mu et al., 2021). Also, MD simulations struggle to effectively integrate experimental data, such as distance restraints or chemical shifts from NMR, global structural features from SAXS, and volumetric density constraints from Cryo-EM to bias the conformational sampling towards experimental profiles. Without the ability to dynamically adjust simulation parameters based on real-time data, the generated ensembles may miss critical structural dynamics and functional states, leading to models that do not accurately reflect the biological reality of IDPs (Wang et al., 2019; Vani et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024a). As a result, while MD remains a valuable tool for studying specific aspects of IDP dynamics, its limitations underscore the need for alternative approaches like DL that can more effectively and efficiently sample the vast conformational landscapes of IDPs within feasible computational timescales (Yang et al., 2023).

3. The Emergence of Deep Learning methods in Protein Structure Prediction

Deep Learning (DL) is a special kind of machine learning (ML) that utilizes artificial neural networks with multiple layers, often referred to as deep neural networks, to autonomously learn hierarchical representations from complex and large-scale datasets. In recent years, DL has emerged as a preferred tool in computational biology, particularly in the field of protein structure prediction (Pakhrin et al., 2021). Unlike traditional methods that rely heavily on physical principles or manual engineering of input feature vectors, DL models can automatically learn complex patterns and representations from large datasets (Ahmed et al., 2023). The success of DL in predicting the structures of well-folded proteins has been exemplified by groundbreaking projects such as AlphaFold (Ruff and Pappu, 2021) and RoseTTA fold (Baek et al., 2021), which demonstrated the potential of these models to achieve near-experimental accuracy in protein structure prediction (Elofsson, 2023). This success has naturally led to interest in applying similar techniques to the more challenging problem of predicting the conformational ensembles of IDPs.

DL models excel in capturing the intricate relationships between amino acid sequences and their corresponding structural features (Kumar and Srivastava, 2024). These models, particularly those based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and transformers, can process vast amounts of sequence and structural data, learning to predict not just a single static structure but an entire range of possible conformations (Ferruz et al., 2023). Transformers, a type of DL model originally developed for natural language processing, utilize self-attention mechanisms to weigh the relationships between all elements in a sequence simultaneously, making them particularly powerful for capturing complex dependencies across long protein sequences (Vaswani et al., 2017; Chandra et al., 2023). This ability is particularly advantageous for IDPs, whose structural flexibility results in a wide array of potential conformational states. By leveraging large-scale datasets, such as those available from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or specialized IDP databases like DisProt (Sickmeier et al., 2007), MobiDB (Piovesan et al., 2021), FuzDB (Hatos et al., 2022), and IDEAL (Fukuchi et al., 2012), DL models can be trained to recognize the diverse conformational patterns characteristic of IDPs. The Protein Ensemble Database (PED) is a primary resource deposit for structural ensembles of IDPs used to train DL models (Ghafouri et al., 2024). This data-driven approach allows DL to sample the conformational landscape of IDPs more comprehensively and efficiently than traditional MD simulations, making it a preferred method in modern structural biology research (Zhu et al., 2024a).

4. Deep Learning Models Employed in the Conformational Sampling of IDPs

To effectively sample the conformational ensembles of IDPs, DL models employ a variety of sophisticated techniques designed to model the high-dimensional and complex nature of IDP conformations. These models range from transformer-based architectures like AlphaFold (pipelines using AlphaFold and its extensions) (Brotzakis et al., 2023; Ghafouri et al., 2024) and variants (Chennakesavalu and Rotskoff, 2024), which leverage sequence-structure dependencies, to generative models such as variational autoencoders (VAEs) (Zhu et al., 2023), generative adversarial networks (GANs) (Janson et al., 2023), and diffusion probabilistic models (Janson and Feig, 2024; Zhu et al., 2024b), each uniquely suited to the conformational sampling challenges of IDPs. By utilizing vast data-driven frameworks, these DL approaches enable efficient and comprehensive exploration of IDP conformational space, often functioning independently of, or in conjunction with, traditional MD simulations. Additionally, certain DL models integrate energy-based principles (Patel and Tewari, 2022; Aranganathan et al., 2024), notably through Boltzmann Generators (BGs) (Patel and Tewari, 2022), to navigate free energy landscapes, reflecting the thermodynamic properties inherent to IDPs.

4.1. Generative Adversarial Networks

GANs were one of the first DL-based methods to be used to generate the conformational ensemble of IDPs (Erdős and Dosztányi, 2024). GANs employ a generator-discriminator architecture, where the generator synthesizes novel protein conformations by transforming random noise or latent variables into structural representations, while the discriminator evaluates their plausibility by comparing them against real data, such as contact maps or inter-residue distance distributions derived from experiments or simulations (Gui et al., 2020). The adversarial training process ensures iterative refinement, with the generator learning to produce increasingly realistic ensembles and the discriminator improving its ability to distinguish physically plausible conformations (Zheng et al., 2023).

By training on coarse-grained and all-atom MD simulations of IDPs with lengths from 20 to 200 residues, idpGAN learns the underlying distribution of protein conformations specific to different sequences. This approach allows idpGAN to generate rapidly generate accurate and diverse ensembles in a fraction of the computational time required by traditional MD simulations. IdpGAN can generate conformational ensembles for arbitrary IDP sequences that match properties like contact maps, radius of gyration distributions, and energy distributions of the training data (Janson et al., 2023).

4.2. Variational AutoEncoders

Another of the most promising approaches for generating IDP conformational ensembles is the application of Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) (Liu et al., 2023), which offer a robust framework for learning the underlying statistical distribution of protein conformations from training data (Janson et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2023). Designed as an extension of traditional (generative) autoencoders (AEs), VAEs employ a dual neural network architecture—a combination of an encoder and a decoder—to reduce the high-dimensional input data, such as protein structural coordinates, into a lower-dimensional latent space, which can then be reconstituted into the original structural format (Kingma and Welling, 2022). This latent space encodes a smooth distribution of conformations, such that novel and realistic protein structures can be generated by sampling from it, offering a means to access structural variations that extend beyond the training set (Chien, 2019). Specifically, for IDPs, VAEs have proven invaluable in capturing the flexibility and structural diversity inherent to these proteins, thereby facilitating the exploration of conformational ensembles that include rare or transient states (Zheng et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2023). VAEs trained on IDP data have shown a remarkable ability to generate high-quality, experimentally-consistent ensembles with fidelity levels that exceed traditional MD and even AlphaFold-based predictions (Mansoor et al., 2024). Here, protein backbone positions were encoded, providing a compressed yet information-dense representation that, upon decoding, could predict high-quality ensemble structures consistent with IDP conformational fluidity.

Phanto-IDP leverages an encoder-decoder architecture optimized for IDPs conformational sampling, specifically addressing IDPs' unique structural flexibility and complexity. The encoder utilizes a modified graph VAE to represent backbone atomic features as nodes and their interactions as edges. After encoding these features, the latent variables undergo variational inference, allowing for smooth distribution in latent space, conducive to diverse conformational generation. The decoder employs three transformer blocks, each integrating self-attention mechanisms and update layers, enabling the direct output of protein backbone Cartesian coordinates with high structural fidelity. The generated structures exhibited accurate radius of gyration distributions and secondary structure propensities, aligning with known experimental conformations (Zhu et al., 2024a).

The model described in Zhu et al. uses a VAE framework optimized to sample IDP ensembles more effectively than traditional methods. Here, short MD trajectories serve as training data, allowing the VAE to encode a comprehensive representation of IDP conformations. This latent space, modeled by a Gaussian distribution, facilitates smooth and realistic sampling of new conformations that correspond well with experimentally observed IDP properties, including Cα RMSD values and Spearman correlation coefficients that outperform standard AEs. Additionally, the generated conformations align well with experimental radius of gyration values and chemical shifts (Zhu et al., 2023).

The Internal Coordinate Net (ICoN) model offers another VAE-based framework for IDP ensemble generation, utilizing bond-angle-torsion (BAT) internal coordinates to represent conformational diversity efficiently. The encoder translates high-dimensional protein structural data into a compact, three-dimensional latent space, optimized to capture structural flexibility with minimal information loss. From this latent space, the decoder reconstructs atomistic-level structures, directly outputting new conformations based on smooth sampling from the latent distribution. By employing variational inference, ICoN generates conformations with low-energy, high-fidelity structural properties, enhancing the accuracy of conformational predictions beyond those captured by the original MD dataset (Ruzmetov et al., 2024).

4.3. Transformers (AphaFold Pipelines)

Transformers excel by leveraging self-attention mechanisms that allow them to consider all residues in a sequence simultaneously (Wang and Li, 2024). This capability is essential for IDPs, where the interactions between distant residues — often characterized by high contact order — can significantly influence the overall conformation (Plaxco et al., 1998). The self-attention mechanism at the core of transformer models sets them apart from other DL techniques like CNNs and RNNs, by allowing it to dynamically weigh the influence of each residue in a sequence based on its transitory effect on every other residue, regardless of distance (Choi and Lee, 2023). This ability to capture long-range, non-linear interactions is particularly advantageous for IDPs, where such dynamic and non-local interactions are crucial for defining the protein’s conformational ensemble, leading to predictions that are both more comprehensive and reliable compared to traditional MD simulations or other DL models. Transformers can process entire protein sequences quickly and efficiently, generating a probabilistic distribution of possible conformations that reflects the inherent flexibility and diversity of IDPs (Ruff and Pappu, 2021). Moreover, transformers have a unique comparative advantage in their scalability and ability to learn from large, diverse datasets. Unlike RNNs, which may suffer from issues like vanishing gradients when dealing with long sequences, transformers maintain performance by processing sequences in parallel, making them highly scalable. AlphaFold (Jumper et al., 2021; Abramson et al., 2024) employs an advanced transformer architecture to capture complex sequence-structure dependencies, leveraging multi-head self-attention mechanisms to model the intricate spatial relationships among amino acid residues, thereby achieving unprecedented accuracy in predicting protein structure (Ruff and Pappu, 2021). Moreover, the advent of AlphaFold2 has fostered the development of various pipelines aimed at effectively modeling multiple conformational states or predicting conformational ensembles of both well-folded proteins and proteins exhibiting intrinsic disorder or intrinsic flexibility (Aranganathan et al., 2024; Fan et al., 2024; Ghafouri et al., 2024; Guan et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024).

A transformer-based model developed by Chennakesavalu and Rotskoff (2021) enhances the conformational sampling of IDPs by reconstructing atomic-resolution protein structures from backbone coordinates. The model integrates statistical side-chain conformations with a transformer architecture to generate realistic protein ensembles. Using a transformer that predicts side-chain configurations based on backbone dihedral angles, the model incorporates both local dihedral dependencies and global sequence-wide interactions. The model efficiently produces atomistic conformations consistent with MD simulations when applied to proteins like Chignolin and the IDR of the androgen receptor (AR-IDR) (Chennakesavalu and Rotskoff, 2024).

4.4. Diffusion Models

Diffusion models represent another class of DL-based approachs that are being used for generating conformational ensembles of IDPs, as opposed to relatively older models like GANs (Ho et al., 2020). They leverage a probabilistic generative framework to learn the inherent structural diversity of IDPs. Diffusion probabilistic models operate through a two-step process involving forward diffusion and reverse denoising. In the forward process, noise is incrementally added to the data, transforming the protein conformations into a noisy latent representation. The reverse process then employs a neural network, typically inspired by architectures like transformers, to denoise the latent space iteratively, reconstructing plausible protein conformations (Zhang et al., 2024). This framework enables the generation of diverse ensembles directly from input sequences, without relying on multiple sequence alignments or extensive experimental data.

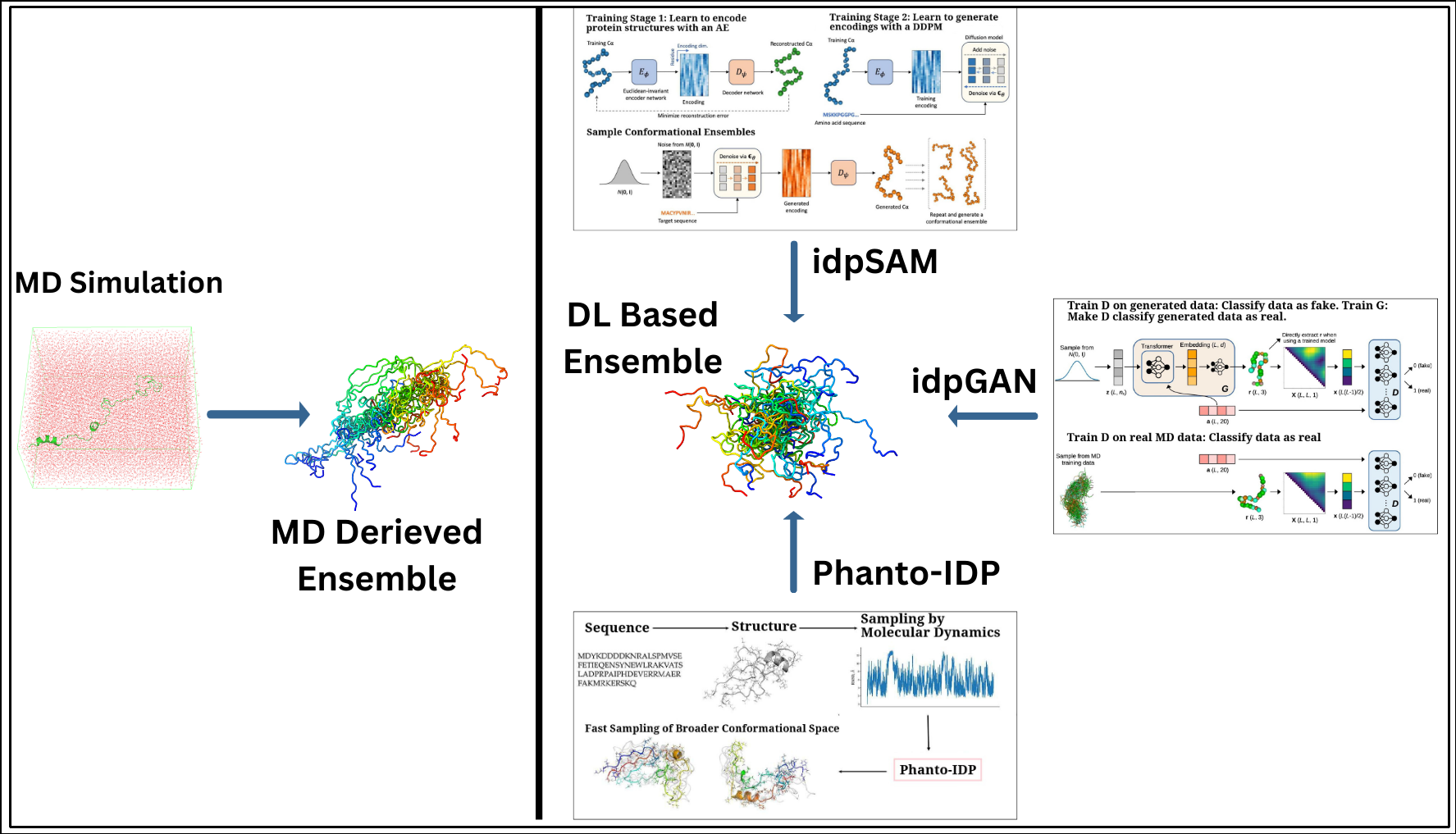

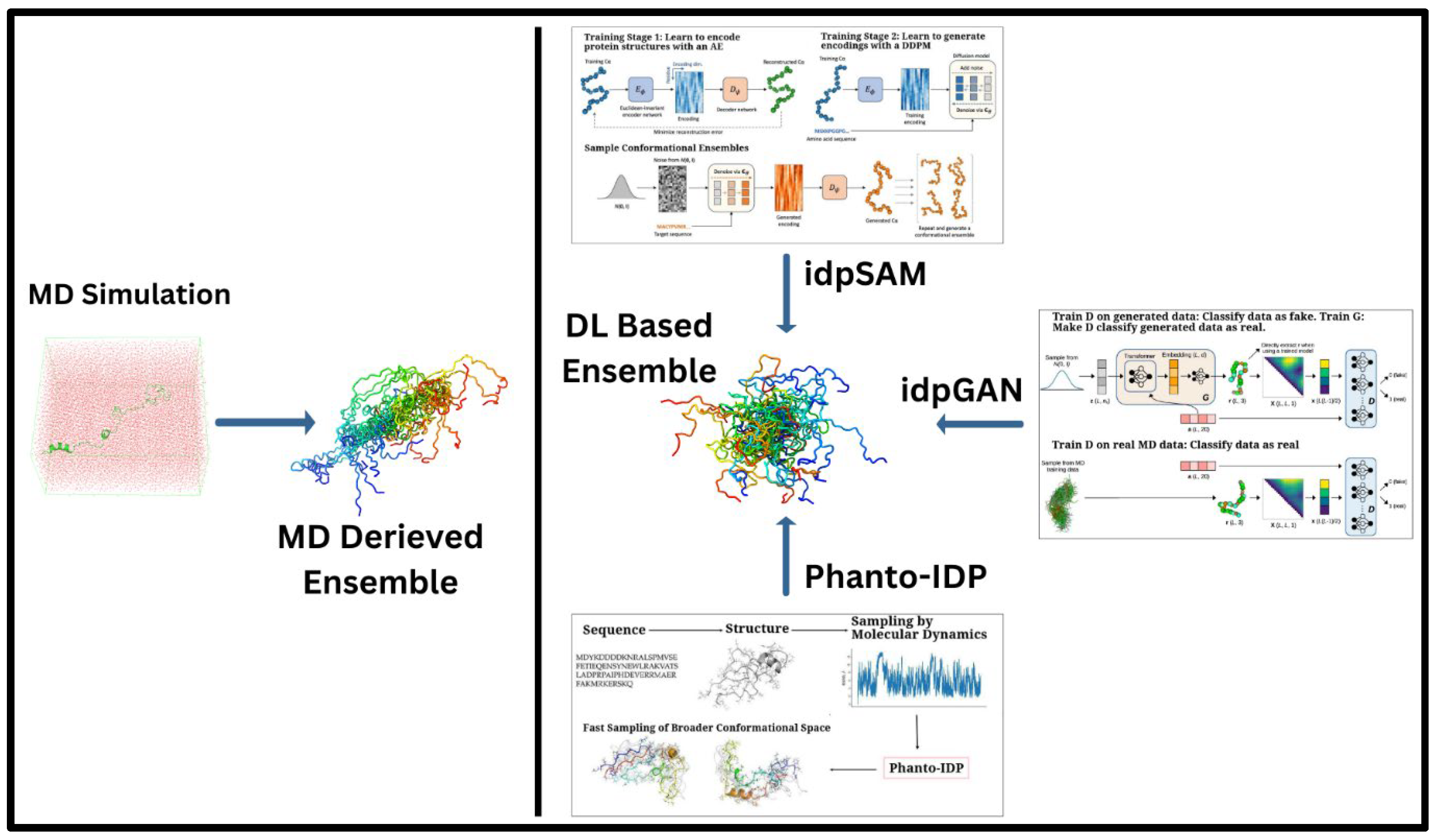

The idpSAM model is a significant advancement, evolving from the earlier idpGAN architecture. It integrates an AE and a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) to enhance the generation of protein conformations. The AE compresses the 3D structural information of protein Cα coordinates into a lower-dimensional latent space. The DDPM then iteratively refines these noisy encodings, learning their probability distribution and improving the quality of generated conformations. After training, a decoder reconstructs 3D structures from these refined encodings, allowing idpSAM to produce highly accurate models of IDPs, including those not present in the training dataset (Janson and Feig, 2024). An overall display of these models and methods as compared to MD simulation is portrayed in Figure 1.

The IDPFold model utilizes a conditional diffusion model framework to generate protein conformational ensembles directly from their sequences. This framework involves a forward diffusion process where noise is gradually added to real protein structures and a reverse diffusion process where a DL network is used for denoising. The denoising networks are constructed using DenoisingIPA Blocks, similar to the structural modules of AlphaFold2, to capture the chain-like structure within proteins and the rotational/translational state of each residue. To address the issue of insufficient data, IDPFold employs a hybrid dataset comprising crystal structures, NMR structures, and MD trajectories for training and evaluation. IDPFold predicted ensembles achieve accuracy levels that are comparable to traditional MD simulations, and sometimes even higher while not being restricted by energy barriers during sampling (Zhu et al., 2024b).

Taneja and Lasker devised a two-stage pipeline where supervised ML models first predict 2D properties of a sequence based on a closely related sequence's ensemble. Then, denoising diffusion models generate 3D coarse-grained ensembles based on these 2D predictions. This approach, trained on a dataset of coarse-grained MD simulations, demonstrated accurate 2D and 3D predictions (Taneja and Lasker, 2024).

Figure 1.

A comparative array of approaches of generating the conformational ensembles for IDPs. A. Traditional MD simulations, which provide detailed conformational sampling of IDPs and B. DL-based generative frameworks offering computationally efficient alternatives to derive IDP ensembles with comparable accuracy. Sub-images (boxes) in B. portray the graphical abstracts of a few highlighted DL-based methods (taken directly from the corresponding papers with appropriate copyright permissions), namely, (i) idpGAN (GAN-driven ensemble generation from MD-based and learned distributions) (Janson et al., 2023), (ii) idpSAM (autoencoder-Diffusion-based sampling of conformations) (Janson and Feig, 2024), and (iii) Phanto-IDP sequence-to-ensemble modeling leveraging MD sampling for broader conformational exploration) (Zhu et al., 2024a).

Figure 1.

A comparative array of approaches of generating the conformational ensembles for IDPs. A. Traditional MD simulations, which provide detailed conformational sampling of IDPs and B. DL-based generative frameworks offering computationally efficient alternatives to derive IDP ensembles with comparable accuracy. Sub-images (boxes) in B. portray the graphical abstracts of a few highlighted DL-based methods (taken directly from the corresponding papers with appropriate copyright permissions), namely, (i) idpGAN (GAN-driven ensemble generation from MD-based and learned distributions) (Janson et al., 2023), (ii) idpSAM (autoencoder-Diffusion-based sampling of conformations) (Janson and Feig, 2024), and (iii) Phanto-IDP sequence-to-ensemble modeling leveraging MD sampling for broader conformational exploration) (Zhu et al., 2024a).

5. Overcoming the Energy Landscape in IDPs

Effectively sampling the conformational space in IDPs requires overcoming large energy barriers that separate diverse conformational states (Do et al., 2014). Traditional methods like REMD address this challenge by simulating multiple replicas of the system at different temperatures, allowing exchanges between replicas to enhance sampling (Qi et al., 2018). However, REMD is computationally expensive, limiting its applicability to large IDPs or long simulation timescales. Deep generative models offer a promising alternative, as they are not restricted by the topology of the potential energy landscapes and can explore conformational spaces more efficiently (Anstine and Isayev, 2023). BGs are a class of generative models specifically trained to sample configurations directly from the system's energy function (Noé et al., 2019). Instead of explicitly learning the system's probability density function (such as from short MD trajectories), these models are designed to sample configurations from an equilibrium distribution by leveraging a dimensionless energy function u(x). They achieve this through a generative network paired with reweighting procedures. The generative network transforms samples from a simple prior distribution P(z) (e.g., a Gaussian) in latent space into high-probability configurations from the target distribution P(x)∝e−u(x) (Zheng et al., 2023). One significant limitation of BGs is their tendency toward mode collapse, focusing on a limited number of low-energy metastable states and failing to explore the broader conformational landscape characteristic of IDPs (Patel and Tewari, 2022). Sparse training data and the complexity of IDP free energy landscapes exacerbate this issue, as these models tend to neglect transient or high-energy states (Noé et al., 2019). Therefore, energy-only learning biases sampling toward stable regions and lacks the diversity needed for IDP modeling. It has been suggested that training solely on energy functions may be insufficient to capture the extensive conformational diversity of IDPs (Patel and Tewari, 2022; Aranganathan et al., 2024). Recent advancements to BGs encompass equivariant flow matching models (Klein et al., 2023b) and transferable BGs (Klein and Noé, 2024), which establish a framework for incorporating molecular topology and symmetries into the energy function of the biomolecular system. But the key drawback remains that massive training datasets are required to explore essential modes without suffering from mode collapse (Aranganathan et al., 2024). Following the achievements of AF2, the Str2Str model employs a heating-annealing training technique for a score-matching model, facilitating navigation across energy landscape barriers (Lu et al., 2024). This method is exclusively trained on crystal structures and enables the simulation of local fluctuations similar to those observed in microsecond-long MD simulations. AlphaFlow/ESMFlow (Jing et al., 2024) leverages the AF2 network within a flow-matching framework and has been trained on both PDB and short MD datasets of 100 nanoseconds to incorporate timescale information into its training regimen to effectively capture local fluctuations (Aranganathan et al., 2024). The ConfDiff model integrates a force-guided diffusion framework and enhances the generation of diverse and high-fidelity protein structures. The model employs a regular forward diffusion - reverse diffusion setup where a DL network utilizes an additional force guidance mechanism to prioritize conformations with lower potential energy. This unique approach allows ConfDiff to align generated structures more closely with the Boltzmann distribution, effectively addressing the limitations of existing score-based diffusion methods that often fail to incorporate essential physical knowledge (Wang et al., 2024b).

Integrating energy-based constraints or regularization terms into other deep generative models has proven successful (Li et al., 2023). For example, idpGAN incorporates energy distributions from MD simulations during training (Janson et al., 2023). This acts as an implicitly learned energy constraint, guiding the model to generate ensembles with realistic energy profiles, thereby improving the accuracy of the generated conformational ensembles. IDPFold captures Boltzmann distributions, ensuring diverse sampling beyond metastable states (Zhu et al., 2024b). Its hybrid training approach—pre-training on experimental structures and fine-tuning on MD trajectories—enhances structural fidelity and flexibility, effectively avoiding energy barriers that limit BGs. By filtering non-physical structures and aligning free energy distributions with MD data, ICoN achieves thermodynamically consistent ensembles (Ruzmetov et al., 2024). Looking forward, the authors have expressed their interest in exploring energy-based training methods for Phanto-IDP to further enhance its performance (Zhu et al., 2024a).

6. Enhanced Conformational Sampling using AI in MD Simulation

Conformational sampling using AI-enhanced MD simulations marks a transformative advancement in structural biology by synergizing the precision of physics-based models with the computational efficiency of ML and DL strategies (Zhang et al., 2023a). Traditional MD simulations, governed by Newtonian mechanics, excel at providing atomistic insights into biomolecular dynamics but are intrinsically limited by their reliance on fine-grained time steps (Hollingsworth and Dror, 2018), which capture fast motions such as bond vibrations but fail to traverse biologically relevant timescales efficiently (Son et al., 2024). Enhanced sampling techniques, such as metadynamics, umbrella sampling, and replica exchange MD, aim to overcome these barriers by reweighting conformational distributions or sampling biased energy landscapes (Abrams and Bussi, 2014). However, these approaches often require detailed prior knowledge of the system, involve considerable computational expense, and are susceptible to missing critical transitions between metastable states. Integration of AI has contributed to the development of enhanced sampling techniques by addressing key limitations of the traditional methods (Prašnikar et al., 2024). For example, ML models trained to estimate free energy surfaces or bias potentials enable adaptive approaches to biased simulations, improving sampling efficiency (Galvelis and Sugita, 2017). Reinforcement learning algorithms have also been employed to optimize the initialization of sampling or the application of bias potentials (Shamsi et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). Learned Replica Exchange (LREX) approach, where BGs are used to directly map high-temperature configurations to target temperatures, effectively bypassing the need for multiple intermediate replicas (Invernizzi et al., 2022). However, these approaches do not fix the problem of needing to re-run simulations from scratch for altered parameters (Aranganathan et al., 2024).

Other than just AI-enhanced sampling procedures, other works have successfully integrated DL models into the MD simulation, such as DeepDriveMD (Lee et al., 2019), which is a deep convolutional variational autoencoder (CVAE) to cluster protein folding trajectories, all collated to a reasonably small number of conformational states. ITO (Implicit Transfer Operator) uses DDPMs to learn transition probabilities directly from MD data, enabling efficient simulation over larger time steps while preserving physical accuracy (Schreiner et al., 2023). Similarly, Timewarp is a normalizing flow-based generative model that learns to dynamically increase and optimize time steps upto a hundred femtoseconds at a time to accelerate the rate of MD when used for conformational sampling (Klein et al., 2023a). DiAMoNDBack employs a generative model to backmap coarse-grained protein structures to all-atom resolution. Using a diffusion-denoising process, it restores atomistic details while maintaining the integrity of the Cα trace to improve the resolution and accuracy of (Jones et al., 2023). Integrating AI methods directly into the MD engine enjoys the advantage of being transferable and well generalized across most large, complex, and novel biomolecular test systems (Aranganathan et al., 2024).

7. Comparative Efficiency: DL versus MD

While MD simulations provide detailed, physics-based insights into protein dynamics, they are notoriously resource-intensive. Simulating a single IDP to capture its complete conformational landscape can require continuous operation on high-performance computing (HPC) clusters for weeks or even months (Shaw et al., 2008; Hollingsworth and Dror, 2018). Studies have shown that adequately exploring the conformational space in IDPs via MD often demands several thousands of CPU hours. Despite the extensive computational resources involved, MD may still fail to capture rare but biologically significant conformational states, which are crucial for understanding the functional roles of IDPs in processes such as protein-protein interactions and the formation of transient complexes (Gopal et al., 2021). In contrast, DL models offer a scalable and far more time-efficient alternative, which are particularly evident in high-throughput analyses. After an initial training phase—which might require substantial computational power (hundreds of GPUs) over a period of many days (Cheng et al., 2023), particularly when processing large datasets like those from the PDB—DL models can predict IDP conformational states in seconds or minutes (Gupta et al., 2022). For instance, a recent study demonstrated that a DL model, trained on IDP conformations, could generate accurate ensemble of 300 conformations in under 20 minutes, a process that could take several days to achieve through MD simulations (Zhu et al., 2024c). The front-loaded computational cost of training DL models is offset by the remarkable speed of the inference phase, which can be executed on less powerful hardware, such as a standard GPU, significantly reducing ongoing computational demands (Alzubaidi et al., 2021).

Beyond their computational efficiency, DL models excel in adaptability and continuous improvement. They can be updated with new data as it becomes available, enhancing their accuracy without the need to rerun simulations from scratch (Taye, 2023). This is particularly advantageous when integrating new experimental data from cryo-EM, or NMR spectroscopy, or from curated IDP databases (Evans et al., 2023; Giri et al., 2023). Updating DL models involves fine-tuning the model parameters using optimization algorithms on new training data, allowing the model to adapt to changes without complete retraining (Prapas et al., 2021). This process typically utilizes transfer learning techniques, where pre-trained weights are adjusted based on new datasets, significantly enhancing prediction accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency (Koval et al., 2023). Such integration refines the model’s predictions and further enhances its utility, a capability that contrasts sharply with MD simulations, which typically require starting anew for each modification or new experimental condition. This adaptability makes DL models highly suitable for dynamic research environments where conditions and data are constantly evolving (Nikolados et al., 2022). The outputs from DL-based IDP conformational sampling tools typically include a set of predicted conformations along with their associated probability distributions, energy scores, and structural metrics to evaluate the relative stability and likelihood of different conformers (Teixeira et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2024).

8. Disadvantages of DL Over MD Simulations

Despite the numerous advantages of DL models in sampling conformational ensembles of IDPs, they also present several notable disadvantages compared to traditional MD simulations. Firstly, DL models are heavily dependent on the quality and diversity of the training data (Munappy et al., 2022). Inadequate or biased datasets can lead to models that fail to generalize well to novel or underrepresented IDP sequences, potentially missing critical conformational states. Secondly, the interpretability of DL models remains a significant challenge (Liu and He, 2024). Unlike MD simulations, which are grounded in physical principles and provide explicit insights into atomic interactions, DL models often operate as "black boxes," making it difficult to understand the underlying mechanisms driving their predictions (Samek et al., 2019). Thirdly, DL models require substantial computational resources and expertise for their development and training. Constructing and fine-tuning these models necessitates advanced knowledge in ML and access to powerful hardware, which may not be readily available to all research groups (Sarker, 2021). Additionally, DL models are susceptible to overfitting, especially when trained on limited datasets. Overfitting can result in models that perform exceptionally well on training data but poorly on unseen data, undermining their reliability for predictive applications (López et al., 2022). Lastly, the physical accuracy of DL-generated conformations can sometimes be compromised, as these models may prioritize statistical patterns over thermodynamic plausibility, leading to predictions that, while statistically likely, may not always reflect biologically relevant states (Wodak et al., 2023). While DL models offer several advantages in generating conformational ensembles of IDPs, including their computational efficiency and ability to predict a broad array of conformations from sequence data alone, it is important to recognize that these models cannot completely replace MD simulations (Gomes et al., 2020; Lindorff-Larsen and Kragelund, 2021). DL-based approaches often rely on training datasets derived from MD-generated conformational ensembles, and their accuracy is intrinsically linked to the quality and diversity of the data they are trained on (Zheng et al., 2023). Without continuous updates and supplementation with new experimental or simulated data, DL models risk generating outdated or biased predictions (Gichoya et al., 2023), particularly as they struggle to generalize well to novel protein sequences or biological conditions not represented in the training data (Janson et al., 2023; Janson and Feig, 2024; Ruzmetov et al., 2024).

9. Applications and Case Studies: Deep Learning in IDP Research

One significant advancement in the field of DL-based conformational ensemble generation for IDPs is the recent inclusion of ensembles generated by methods such as idpGAN and IDPConformerGenerator in the PED (Ghafouri et al., 2024). This marks a pivotal shift from the previous focus solely on ensembles derived from explicit experimental data, such as those obtained through MD simulations. These methods are particularly useful for disordered proteins like Amyloid-beta (Aβ) (Scollo and Rosa, 2020) and alpha-synuclein (Williams et al., 2018), which play key roles in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Aβ is a disordered peptide involved in Alzheimer's disease, and its structural ensemble has been extensively studied (Balupuri et al., 2020). In the case of Aβ, AlphaFold was utilized to predict inter-residue distances, which were then employed to refine MD-generated ensembles through a reweighting procedure (Brotzakis et al., 2023). This refinement results showed significant improvements in structural accuracy, with a reduction in the RMSD and negation of all distance violations, indicating that AlphaFold's predictions closely matched experimental data. To expedite the process, researchers used FoldingDiff, to rapidly approximate the conformational space of Aβ. Despite starting from ensembles of lower initial quality compared to MD simulations, the FoldingDiff-generated ensembles, when refined through reweighting, achieved biologically relevant conformations more efficiently than MD alone. This approach highlights how DL models can produce accurate and computationally efficient ensembles of disordered proteins. Similar to the approach used for Aβ, AlphaFold was employed to predict inter-residue distances in alpha-synuclein (Brotzakis et al., 2023), which were then used to refine an MD-generated ensemble through reweighting. The resulting ensemble of alpha-synuclein showed substantial improvements, with reduced RMSD and again a complete elimination of distance violations. The secondary structure predictions also showed minor shifts, with the AF-MD ensemble being slightly more α-helical and less β-sheet-like than the original MD ensemble.

In the study conducted by Ruzmetov et al., ICoN was introduced to effectively generate conformational ensembles for highly dynamic proteins such as the amyloid-β1-42 (Aβ42) monomer (Ruzmetov et al., 2024). The model learned the physical principles underlying protein motions from MD simulation data, leveraging this knowledge to rapidly identify new synthetic conformations of Aβ42. By interpolating data points in a learned latent space, ICoN was able to reveal novel conformational clusters that were not present in the training dataset, providing critical insights into the structural properties of Aβ42 involved in disease-related aggregation pathways. Importantly, ICoN demonstrated the ability to uncover distinct conformations that included key sidechain rearrangements and salt bridges, such as the Asp23-Lys28 interaction, that are critical for Aβ42 oligomerization and fibril formation. This approach offered a computationally efficient alternative to traditional MD simulations, enabling faster and broader sampling of conformational landscapes for IDPs.

In another study focused on three IDPs—polyglutamine Q15, Amyloid-beta 40 (Aβ40), and ChiZ from Mycobacterium tuberculosis—researchers employed DL-based AEs to generate conformational ensembles (Gupta et al., 2022). The AEs were trained on a limited dataset from short MD simulations, minimizing training time while maintaining the quality of the resulting conformations. The AEs demonstrated a marked ability to generate full conformational ensembles that accurately reproduced the experimental data and covered all conformations sampled in long MD simulations. For Q15 and Aβ40, the multivariate Gaussian model applied in the latent space enabled high-quality conformational reconstructions, with RMSD of around 5 Å and 6 Å, respectively. The generated ensembles effectively captured the diversity of the MD-sampled conformations, particularly in the smaller IDPs like Q15. Despite the challenges presented by larger proteins like ChiZ, where reconstruction RMSDs were higher (~7 Å), the generative AE approach still outperformed traditional MD simulations by rapidly expanding the conformational space without extensive computational overhead. The results were validated through SAXS profiles and NMR chemical shifts, further highlighting the potential of DL in mining the conformational landscapes of complex IDPs.

10. Discussion and Future Directions

Recent breakthroughs in AI has shifted the status quo in protein structure and function prediction. The 50 year old problem of predicting proteins’ complex structures has largely been addressed by the likes of AlphaFold, RoseTTA Fold and others and the field has been awarded a part of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2024. However, most of the work in this field has largely been on well defined structured proteins and IDPs remain largely unexplored (Trivedi and Nagarajaram, 2022). Studying conformational ensembles of IDPs remain crucial to understanding their intrinsic flexibility allowing them to engage in a variety of biological functions such as signalling and molecular recognition, which are often mediated transient interactions with other biomolecules (Krieger et al., 2014). Additionally, aberrant behavior of IDPs is often linked to various diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders and cancers (Martinelli et al., 2019). Understanding the conformational dynamics of IDPs can help elucidate the molecular basis of these diseases and identify potential therapeutic targets (Abyzov et al., 2022). Traditional MD simulations and their various modifications have been extensively used for sampling the conformational ensembles of IDPs, however their shortcomings stand bold and clear (Zhu et al., 2023; Janson and Feig, 2024). Use of AI based tools in generating or sampling the various conformational states of IDPs has emerged as a key new frontier with distinguished advantages (Zhu et al., 2024c). For this, AI methods have been integrated in enhanced sampling techniques from MD simulations, as well as, integrated directly into the MD engines (Aranganathan et al., 2024; Prašnikar et al., 2024). Much effort has been dedicated to generative models such as GANs, VAEs, diffusion models, and others (Ruzmetov et al., 2024). Many methods have also been devised to sample IDP conformational states using AlphaFold pipelines (Ghafouri et al., 2024). Sampling most of the possible biologically relevant conformations of IDPs just from their protein sequence as an input is the ultimate goal but a gargantuan task. But already we have seen steady progress in this endeavour (Zheng et al., 2023). A common objective of most generative models, employed for the generation of the conformational states of IDPs, is to learn a low-dimensional latent representation of the high-dimensional conformational space of proteins to efficiently generate realistic and diverse conformational ensembles (Zhu et al., 2024a). (Janson and Feig, 2024; Zhu et al., 2024b). Incorporating physics-based calculations into generative DL models is increasingly recognized as essential for developing approaches that yield predictions with higher accuracy and biological relevance (Raissi et al., 2019; Jagtap et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020, 2022).

Although DL models can efficiently predict protein conformations and improve the speed of conformational ensemble generation, they remain limited by their reliance on pre-existing datasets (Vignesh et al., 2024). As a result, while DL models are a powerful tool for exploring protein conformational landscapes, they should be considered complementary to, rather than a replacement for, traditional MD simulations. AI-based conformational studies of IDPs, such as alpha-synuclein, Tau protein, and amyloid-β, hold significant promise for elucidating the molecular basis and pathophysiology of diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's (Sengupta and Kayed, 2022; Brotzakis et al., 2023). These studies can also aid in modelling novel and targeted therapeutic approaches, enhancing drug discovery efforts (Joshi and Vendruscolo, 2015). Future efforts should focus on integrating thermodynamic constraints directly into generative models to improve the accuracy and biological relevance of the generated conformations, since it has already be shown that learning the energy function along is not enough (Zheng et al., 2023). Most of the models today are capable of accurately sampling only relatively smaller IDP sequences. Larger IDP (including IDRs in large proteins) sequences can form non-trivial local structures which show transient long-range interactions within its sequence which are essential in understanding the underlying phenom ena (Wohl and Zheng, 2023). Future research should explore scaling generative models to larger IDPs, (also pertaining to the IDRs present in large proteins and their intramolecular interactions) potentially by using hierarchical approaches that break down long sequences into smaller segments.

Most of the DL based tools made to predict the conformational ensembles of IDPs rely on training on simulated data i.e. CG or all-atom MD simulations and then validation via experimental data (Janson et al., 2023). While this paradigm has shown significant progress and promise, the other avenue i.e., training both on simulated data and experimental observables have been relatively less explored (Liu et al., 2024). DynamICE is another AI based tool developed that learns the probability of succeeding residue torsions from the preceding residue of the input sequence by employing a generative recurrent neural network (GRNN) model to build new conformational states of an IDP ensemble (Zhang et al., 2023b). DynamICE (dynamic IDP creator with experimental restraints) distinguishes itself by taking advantage of experimental data types such as three-bond J-couplings (JCs), nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs), and paramagnetic resonance enhancements (PREs) from NMR spectroscopy to bias the probability distributions of torsions of the GRNN (Lincoff et al., 2020). It evolves the structural ensembles dynamically by refining conformations through reward-based feedback, ensuring consistency with experimental data, rather than reweighting pre-existing static pools. ExEnDiff is a model that employs an experiment-guided diffusion framework, where a stochastic differential equation is utilized to perturb protein data distributions towards a Gaussian distribution. By integrating experimental measurements from techniques such as NMR and SAXS, ExEnDiff corrects the sampling process to ensure that generated conformations align with physical realities and the Boltzmann distribution (Liu et al., 2024). Future efforts should explore to incorporate experimental constraints directly into DL pipelines to gradually evolve the structural ensemble prediction based on both simulated data and experimental observables. Further comparative studies on biological accuracy, thermodynamic relevance, and performance across the two broad paradigms will be crucial in determining whether a balanced reliance on both experimental and simulated data is most effective, or if prioritizing one data type over the other is more beneficial for generating accurate IDP conformational ensembles. Apart from iterative improvement of existing AI based models and using newer learning methods, it is hard to foresee how the generative ML models of predicting conformational ensembles of IDPs will evolve, or how generally applicable these models will be to the full range of protein behaviours critical to biological processes. Additionally, the transferability of generative models to novel sequences or different environmental conditions remains an open question. Even though this field of research is relatively new, there is no doubt that the further development of AI tools and their subsequent application will revolutionise the conformational sampling of IDPs both by enhancing MD simulation strategies and conformational ensemble prediction by generative methods (Ruzmetov et al., 2024).

Funding

The project was self-funded.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Acknowledgments

SB acknowledges the support from Research and Development Cell, Asutosh College, Kolkata, India.

Author’s Contribution

SB conceptualized and designed the review, SS did most part of literature survey with help from ID. SS compiled the disposition of the manuscript and wrote its first draft. ID compiled the graphical abstract (

Figure 1). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

- Abrams, C. , and Bussi, G. (2014). Enhanced Sampling in Molecular Dynamics Using Metadynamics, Replica-Exchange, and Temperature-Acceleration. Entropy. [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J. , Adler, J., Dunger, J., Evans, R., Green, T., Pritzel, A., et al. (2024). Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. ( 2024). Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500. [CrossRef]

- Abyzov, A. , Blackledge, M., and Zweckstetter, M. (2022). Conformational Dynamics of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Regulate Biomolecular Condensate Chemistry. ( 2022). Conformational Dynamics of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Regulate Biomolecular Condensate Chemistry. Chem Rev 122, 6719–6748. [CrossRef]

- Aftab, A. , Sil, S., Nath, S., Basu, A., and Basu, S. (2024). Intrinsic Disorder and Other Malleable Arsenals of Evolved Protein Multifunctionality. J Mol Evol. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. F. , Alam, Md. S. B., Hassan, M., Rozbu, M. R., Ishtiak, T., Rafa, N., et al. (2023). Deep learning modelling techniques: current progress, applications, advantages, and challenges. Artif Intell Rev, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L. , Zhang, J., Humaidi, A. J., Al-Dujaili, A., Duan, Y., Al-Shamma, O., et al. (2021). Review of deep learning: concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. Journal of Big Data. [CrossRef]

- Anstine, D. M. , and Isayev, O. (2023). Generative Models as an Emerging Paradigm in the Chemical Sciences. ( 2023). Generative Models as an Emerging Paradigm in the Chemical Sciences. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8736–8750. [CrossRef]

- Arai, M. , Suetaka, S., and Ooka, K. (2024). Dynamics and interactions of intrinsically disordered proteins. ( 2024). Dynamics and interactions of intrinsically disordered proteins. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 84, 102734. [CrossRef]

- Aranganathan, A. , Gu, X., Wang, D., Vani, B., and Tiwary, P. (2024). Modeling Boltzmann weighted structural ensembles of proteins using AI based methods. [CrossRef]

- Baek, M. , DiMaio, F., Anishchenko, I., Dauparas, J., Ovchinnikov, S., Lee, G. R., et al. (2021). Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science. [CrossRef]

- Bah, A. , and Forman-Kay, J. D. (2016). Modulation of Intrinsically Disordered Protein Function by Post-translational Modifications. J Biol Chem, 6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balupuri, A. , Choi, K.-E., and Kang, N. S. (2020). Aggregation Mechanism of Alzheimer’s Amyloid β-Peptide Mediated by α-Strand/α-Sheet Structure. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A. , and Basu, S. (2020). Criticality in the conformational phase transition among self-similar groups in intrinsically disordered proteins: Probed by salt-bridge dynamics. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics, 4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S. , and Lin, X. (2019). Recent Advances in Computational Protocols Addressing Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. ( 2019). Recent Advances in Computational Protocols Addressing Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Biomolecules 9, 146. [CrossRef]

- Brosey, C. A. , and Tainer, J. A. (2019). Evolving SAXS versatility: solution X-ray scattering for macromolecular architecture, functional landscapes, and integrative structural biology. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. [CrossRef]

- Brotzakis, Z. F. , Zhang, S., and Vendruscolo, M. (2023). AlphaFold Prediction of Structural Ensembles of Disordered Proteins. 2023.01.19.524720. [CrossRef]

- Brown, B. P. , Stein, R. A., Meiler, J., and Mchaourab, H. S. (2024). Approximating Projections of Conformational Boltzmann Distributions with AlphaFold2 Predictions: Opportunities and Limitations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugge, K. , Brakti, I., Fernandes, C. B., Dreier, J. E., Lundsgaard, J. E., Olsen, J. G., et al. (2020). Interactions by Disorder – A Matter of Context. Front. Mol. Biosci. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A. , Tünnermann, L., Löfstedt, T., and Gratz, R. (2023). Transformer-based deep learning for predicting protein properties in the life sciences. eLife. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S. , Zhao, X., Lu, G., Fang, J., Yu, Z., Zheng, T., et al. (2023). FastFold: Reducing AlphaFold Training Time from 11 Days to 67 Hours. [CrossRef]

- Chennakesavalu, S. , and Rotskoff, G. M. (2024). Data-Efficient Generation of Protein Conformational Ensembles with Backbone-to-Side-Chain Transformers. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, J.-T. (2019). “Chapter 7 - Deep Neural Network,” in Source Separation and Machine Learning, ed. J.-T. Chien (Academic Press), 259–320. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-M. , and Pappu, R. V. (2019). Improvements to the ABSINTH forcefield for proteins based on experimentally derived amino-acid specific backbone conformational statistics. Journal of chemical theory and computation. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. R. , and Lee, M. (2023). Transformer Architecture and Attention Mechanisms in Genome Data Analysis: A Comprehensive Review. Biology (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Dishman, A. F. , and Volkman, B. F. (2018). Unfolding the Mysteries of Protein Metamorphosis. F. ( 2018). Unfolding the Mysteries of Protein Metamorphosis. ACS Chem Biol 13, 1438–1446. [CrossRef]

- Do, T. N. , Choy, W.-Y., and Karttunen, M. (2014). Accelerating the Conformational Sampling of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. ( 2014). Accelerating the Conformational Sampling of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 5081–5094. [CrossRef]

- Elofsson, A. (2023). Progress at protein structure prediction, as seen in CASP15. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. [CrossRef]

- Erdős, G. , and Dosztányi, Z. (2024). Deep learning for intrinsically disordered proteins: From improved predictions to deciphering conformational ensembles. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. [CrossRef]

- Evans, R. , Ramisetty, S., Kulkarni, P., and Weninger, K. (2023). Illuminating Intrinsically Disordered Proteins with Integrative Structural Biology. ( 2023). Illuminating Intrinsically Disordered Proteins with Integrative Structural Biology. Biomolecules 13, 124. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. , Li, Z., Alcaide, E., Ke, G., Huang, H., and Weinan, E. (2024). Accurate Conformation Sampling via Protein Structural Diffusion. 2024.05.20.594916. [CrossRef]

- Ferruz, N. , Heinzinger, M., Akdel, M., Goncearenco, A., Naef, L., and Dallago, C. (2023). From sequence to function through structure: Deep learning for protein design. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.-L. M. , Tichy, A., Kokot, J., Hoerschinger, V. J., Wild, R. F., Riccabona, J. R., et al. (2024). The Role of Force Fields and Water Models in Protein Folding and Unfolding Dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuchi, S. , Sakamoto, S., Nobe, Y., Murakami, S. D., Amemiya, T., Hosoda, K., et al. (2012). IDEAL: Intrinsically Disordered proteins with Extensive Annotations and Literature. Nucleic Acids Research. [CrossRef]

- Galvelis, R. , and Sugita, Y. (2017). Neural Network and Nearest Neighbor Algorithms for Enhancing Sampling of Molecular Dynamics. ( 2017). Neural Network and Nearest Neighbor Algorithms for Enhancing Sampling of Molecular Dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 2489–2500. [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri, H. , Lazar, T., Del Conte, A., Tenorio Ku, L. G., PED Consortium, Tompa, P., et al. (2024). PED in 2024: improving the community deposition of structural ensembles for intrinsically disordered proteins. Nucleic Acids Research. [CrossRef]

- Gichoya, J. W. , Thomas, K., Celi, L. A., Safdar, N., Banerjee, I., Banja, J. D., et al. (2023). AI pitfalls and what not to do: mitigating bias in AI. Br J Radiol, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, N. , Roy, R. S., and Cheng, J. (2023). Deep learning for reconstructing protein structures from cryo-EM density maps: recent advances and future directions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.-N. W. , Krzeminski, M., Namini, A., Martin, E. W., Mittag, T., Head-Gordon, T., et al. (2020). Conformational ensembles of an intrinsically disordered protein consistent with NMR, SAXS and single-molecule FRET. J Am Chem Soc, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X. , Zhang, Y., and Chen, J. (2021). Advanced Sampling Methods for Multiscale Simulation of Disordered Proteins and Dynamic Interactions. ( 2021). Advanced Sampling Methods for Multiscale Simulation of Disordered Proteins and Dynamic Interactions. Biomolecules 11, 1416. [CrossRef]

- Gopal, S. M. , Wingbermühle, S., Schnatwinkel, J., Juber, S., Herrmann, C., and Schäfer, L. V. (2021). Conformational Preferences of an Intrinsically Disordered Protein Domain: A Case Study for Modern Force Fields. J. Phys. Chem. B. [CrossRef]

- Guan, X. , Tang, Q.-Y., Ren, W., Chen, M., Wang, W., Wolynes, P. G., et al. (2024). Predicting protein conformational motions using energetic frustration analysis and AlphaFold2. ( 2024). Predicting protein conformational motions using energetic frustration analysis and AlphaFold2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, e2410662121. [CrossRef]

- Gui, J. , Sun, Z., Wen, Y., Tao, D., and Ye, J. (2020). A Review on Generative Adversarial Networks: Algorithms, Theory, and Applications. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. , Dey, S., Hicks, A., and Zhou, H.-X. (2022). Artificial intelligence guided conformational mining of intrinsically disordered proteins. ( 2022). Artificial intelligence guided conformational mining of intrinsically disordered proteins. Commun Biol 5, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Guvench, O. , and MacKerell, A. D. (2008). Comparison of protein force fields for molecular dynamics simulations. D. ( 2008). Comparison of protein force fields for molecular dynamics simulations. Methods Mol Biol 443, 63–88. [CrossRef]

- Han, M. , Xu, J., and Ren, Y. (2017). Sampling conformational space of intrinsically disordered proteins in explicit solvent: Comparison between well-tempered ensemble approach and solute tempering method. J Mol Graph Model. [CrossRef]

- Hatos, A. , Monzon, A. M., Tosatto, S. C. E., Piovesan, D., and Fuxreiter, M. (2022). FuzDB: a new phase in understanding fuzzy interactions. Nucleic Acids Research. [CrossRef]

- Ho, J. , Jain, A., and Abbeel, P. (2020). Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, S. A. , and Dror, R. O. (2018). Molecular dynamics simulation for all. O. ( 2018). Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron 99, 1129–1143. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z. , Sun, T., Chen, W., Nordenskiöld, L., and Lu, L. (2024). Refined Bonded Terms in Coarse-Grained Models for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Improve Backbone Conformations. J. Phys. Chem. B, 6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. , Rauscher, S., Nawrocki, G., Ran, T., Feig, M., de Groot, B. L., et al. (2017). CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat Methods. [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, M. , Krämer, A., Clementi, C., and Noé, F. (2022). Skipping the Replica Exchange Ladder with Normalizing Flows. ( 2022). Skipping the Replica Exchange Ladder with Normalizing Flows. J Phys Chem Lett 13, 11643–11649. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, A. D. , Kharazmi, E., and Karniadakis, G. E. (2020). Conservative physics-informed neural networks on discrete domains for conservation laws: Applications to forward and inverse problems. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, G. , and Feig, M. Transferable deep generative modeling of intrinsically disordered protein conformations. 2024.02.08.57 9522. [CrossRef]

- Janson, G. , Valdes-Garcia, G., Heo, L., and Feig, M. (2023). Direct generation of protein conformational ensembles via machine learning. ( 2023). Direct generation of protein conformational ensembles via machine learning. Nat Commun 14, 774. [CrossRef]

- Jing, B. , Berger, B., and Jaakkola, T. (2024). AlphaFold Meets Flow Matching for Generating Protein Ensembles. [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. S. , Shmilovich, K., and Ferguson, A. L. (2023). DiAMoNDBack: Diffusion-Denoising Autoregressive Model for Non-Deterministic Backmapping of Cα Protein Traces. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P. , and Vendruscolo, M. (2015). Druggability of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. ( 2015). Druggability of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Adv Exp Med Biol 870, 383–400. [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J. , Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. ( 2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589. [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D. P. , and Welling, M. (2022). Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. [CrossRef]

- Klein, L. , Foong, A. Y. K., Fjelde, T. E., Mlodozeniec, B., Brockschmidt, M., Nowozin, S., et al. (2023a). Timewarp: Transferable Acceleration of Molecular Dynamics by Learning Time-Coarsened Dynamics. [CrossRef]

- Klein, L. , Krämer, A., and Noé, F. (2023b). Equivariant flow matching. [CrossRef]

- Klein, L. , and Noé, F. (2024). Transferable Boltzmann Generators. [CrossRef]

- Koval, A. , Sharif Mansouri, S., and Kanellakis, C. (2023). “Chapter 10 - Machine learning for ARWs,” in Aerial Robotic Workers, eds. G. Nikolakopoulos, S. Sharif Mansouri, and C. Kanellakis (Butterworth-Heinemann), 159–174. [CrossRef]

- Krieger, J. M. , Fusco, G., Lewitzky, M., Simister, P. C., Marchant, J., Camilloni, C., et al. (2014). Conformational Recognition of an Intrinsically Disordered Protein. ( 2014). Conformational Recognition of an Intrinsically Disordered Protein. Biophys J 106, 1771–1779. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P. , Achuthan, S., Bhattacharya, S., Jolly, M. K., Kotnala, S., Leite, V. B. P., et al. (2021). Protein conformational dynamics and phenotypic switching. Biophys Rev, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P. , Leite, V. B. P., Roy, S., Bhattacharyya, S., Mohanty, A., Achuthan, S., et al. (2022). Intrinsically disordered proteins: Ensembles at the limits of Anfinsen’s dogma. Biophys Rev (Melville). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N. , and Srivastava, R. (2024). Deep learning in structural bioinformatics: current applications and future perspectives. Brief Bioinform. [CrossRef]

- Latham, A. P. , and Zhang, B. (2019). Improving Coarse-Grained Protein Force Fields with Small-Angle X-ray Scattering Data. J. Phys. Chem. B, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. , Turilli, M., Jha, S., Bhowmik, D., Ma, H., and Ramanathan, A. (2019). DeepDriveMD: Deep-Learning Driven Adaptive Molecular Simulations for Protein Folding., (IEEE Computer Society), 12–19. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. , Beaudoin, C., and Ghosh, S. (2023). Energy-based generative models for target-specific drug discovery. Front. Mol. Med. [CrossRef]

- Li, S. , Li, M., Wang, Y., He, X., Zheng, N., Zhang, J., et al. (2024). Improving AlphaFlow for Efficient Protein Ensembles Generation. [CrossRef]

- Lincoff, J. , Haghighatlari, M., Krzeminski, M., Teixeira, J. M. C., Gomes, G.-N. W., Gradinaru, C. C., et al. (2020). Extended experimental inferential structure determination method in determining the structural ensembles of disordered protein states. Commun Chem. [CrossRef]

- Lindorff-Larsen, K. , and Kragelund, B. B. (2021). On the Potential of Machine Learning to Examine the Relationship Between Sequence, Structure, Dynamics and Function of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. B. ( Dynamics and Function of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology 433, 167196. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. , Yang, Z., Yu, Z., Liu, Z., Liu, D., Lin, H., et al. (2023). Generative artificial intelligence and its applications in materials science: Current situation and future perspectives. Journal of Materiomics. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. , Yu, Z. 2024.10.04.61 6517. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. , and He, K. (2024). A Decade’s Battle on Dataset Bias: Are We There Yet? [CrossRef]

- López, O. A. M. , López, A. M., and Crossa, D. J. (2022). “Overfitting, Model Tuning, and Evaluation of Prediction Performance,” in Multivariate Statistical Machine Learning Methods for Genomic Prediction [Internet], (Springer). [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. , Zhong, B., Zhang, Z., and Tang, J. (2024). Str2Str: A Score-based Framework for Zero-shot Protein Conformation Sampling. [CrossRef]

- Maiti, S. , Singh, A., Maji, T., Saibo, N. V., and De, S. (2024). Experimental methods to study the structure and dynamics of intrinsically disordered regions in proteins. ( 2024). Experimental methods to study the structure and dynamics of intrinsically disordered regions in proteins. Current Research in Structural Biology 7, 100138. [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, S. , Baek, M., Park, H., Lee, G. R., and Baker, D. (2024). Protein Ensemble Generation Through Variational Autoencoder Latent Space Sampling. ( 2024). Protein Ensemble Generation Through Variational Autoencoder Latent Space Sampling. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 2689–2695. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, A. H. S. , Lopes, F. C., John, E. B. O., Carlini, C. R., and Ligabue-Braun, R. (2019). Modulation of Disordered Proteins with a Focus on Neurodegenerative Diseases and Other Pathologies. ( 2019). Modulation of Disordered Proteins with a Focus on Neurodegenerative Diseases and Other Pathologies. Int J Mol Sci 20, 1322. [CrossRef]

- Mu, J. , Liu, H., Zhang, J., Luo, R., and Chen, H.-F. (2021). Recent Force Field Strategies for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. ( 2021). Recent Force Field Strategies for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. J Chem Inf Model 61, 1037–1047. [CrossRef]

- Munappy, A. R. , Bosch, J., Olsson, H. H., Arpteg, A., and Brinne, B. (2022). Data management for production quality deep learning models: Challenges and solutions. Journal of Systems and Software, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, C. , Draizen, E. J., and Bourne, P. E. (2018). Structural biology meets data science: does anything change? Current Opinion in Structural Biology. [CrossRef]

- Nikolados, E.-M. , Wongprommoon, A., Aodha, O. M., Cambray, G., and Oyarzún, D. A. (2022). Accuracy and data efficiency in deep learning models of protein expression. Nat Commun. [CrossRef]

- Noé, F. , Olsson, S., Köhler, J., and Wu, H. (2019). Boltzmann generators: Sampling equilibrium states of many-body systems with deep learning. Science, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orosz, F. , and Ovádi, J. (2011). Proteins without 3D structure: definition, detection and beyond. Bioinformatics, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhrin, S. C. , Shrestha, B., Adhikari, B., and KC, D. B. (2021). Deep Learning-Based Advances in Protein Structure Prediction. Int J Mol Sci. [CrossRef]

- Patel, Y. , and Tewari, A. (2022). RL Boltzmann Generators for Conformer Generation in Data-Sparse Environments. Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/2211.10771 (Accessed , 2024). 28 October.

- Piovesan, D. , Necci, M., Escobedo, N., Monzon, A. M., Hatos, A., Mičetić, I., et al. (2021). MobiDB: intrinsically disordered proteins in 2021. Nucleic Acids Research. [CrossRef]

- Plaxco, K. W. , Simons, K. T., and Baker, D. (1998). Contact order, transition state placement and the refolding rates of single domain proteins1. ( transition state placement and the refolding rates of single domain proteins1. Journal of Molecular Biology 277, 985–994. [CrossRef]

- Prapas, I. , Derakhshan, B., Mahdiraji, A. R., and Markl, V. (2021). Continuous Training and Deployment of Deep Learning Models. ( 2021). Continuous Training and Deployment of Deep Learning Models. Datenbank Spektrum 21, 203–212. [CrossRef]

- Prašnikar, E. , Ljubič, M., Perdih, A., and Borišek, J. (2024). Machine learning heralding a new development phase in molecular dynamics simulations. ( 2024). Machine learning heralding a new development phase in molecular dynamics simulations. Artif Intell Rev 57, 102. [CrossRef]

- Qi, R. , Wei, G., Ma, B., and Nussinov, R. (2018). Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics: A Practical Application Protocol with Solutions to Common Problems and a Peptide Aggregation and Self-Assembly Example. Methods Mol Biol. [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M. , Perdikaris, P., and Karniadakis, G. E. (2019). Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics. [CrossRef]

- Robustelli, P. , Piana, S., and Shaw, D. E. (2018). Developing a molecular dynamics force field for both folded and disordered protein states. E. ( 2018). Developing a molecular dynamics force field for both folded and disordered protein states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E4758–E4766. [CrossRef]