1. Introduction

The periodontal phenotype encompasses a biological system that includes the bone morphotype (representing the thickness of the buccal bone) and the gingival phenotype (comprising the width of keratinized tissue and gingival thickness). These three factors play a crucial role in the overall periodontal health. The significance of the gingival phenotype lies in its impact on treatment outcomes and tissue healing processes.

A thin gingival phenotype (GP) is associated with the development of mucogingival problems, compromised results following root coverage procedures, and impaired postoperative outcomes. It greatly influences restorative, prosthetic, and surgical treatments. Gingival thickness (GT) serves as an important predictor for aesthetic and implant treatment outcomes. Therefore, its pre-treatment assessment is essential, as it helps minimize postoperative treatment complications [

1,

2].

Prior to initiating any treatment, it is essential to assess the periodontal phenotype. The Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions in 2017 distinguishes three categories: thin-scalloped, thick-scalloped, and thick-flat periodontal phenotypes [

3,

4,

5]. Phenotype modification therapy (PhMT) is particularly necessary for patients with a thin scalloped gingival phenotype, where the delicate tissue predisposes to gingival recessions.

Surgical procedures such as coronally advanced flap with connective tissue graft and free gingival graft around natural teeth and implants are commonly employed in periodontal surgery, yielding undeniable clinical success [

6,

7]. Various clinical approaches utilizing allogeneic materials have been developed to avoid the need for a second surgical site (donor site) [

8]. Since the introduction of autologous blood products in oral and periodontal surgery, many surgical treatment modalities have been modified to explore their use in periodontal phenotype modification [

9].

2. Materials and Methods

The recent literature review was conducted utilizing well-established academic databases, including ResearchGate, EBSCO, and Google Scholar, to ensure a comprehensive and high-quality search of relevant studies. The search strategy employed a series of carefully selected keywords, namely: PRF, injectable PRF, periodontal phenotype, gingival phenotype, gingival phenotype enhancement, and gingival augmentation. These terms were chosen to encompass the breadth of topics related to the utilization of injectable PRF in the context of periodontal and gingival phenotype management.

3. Findings

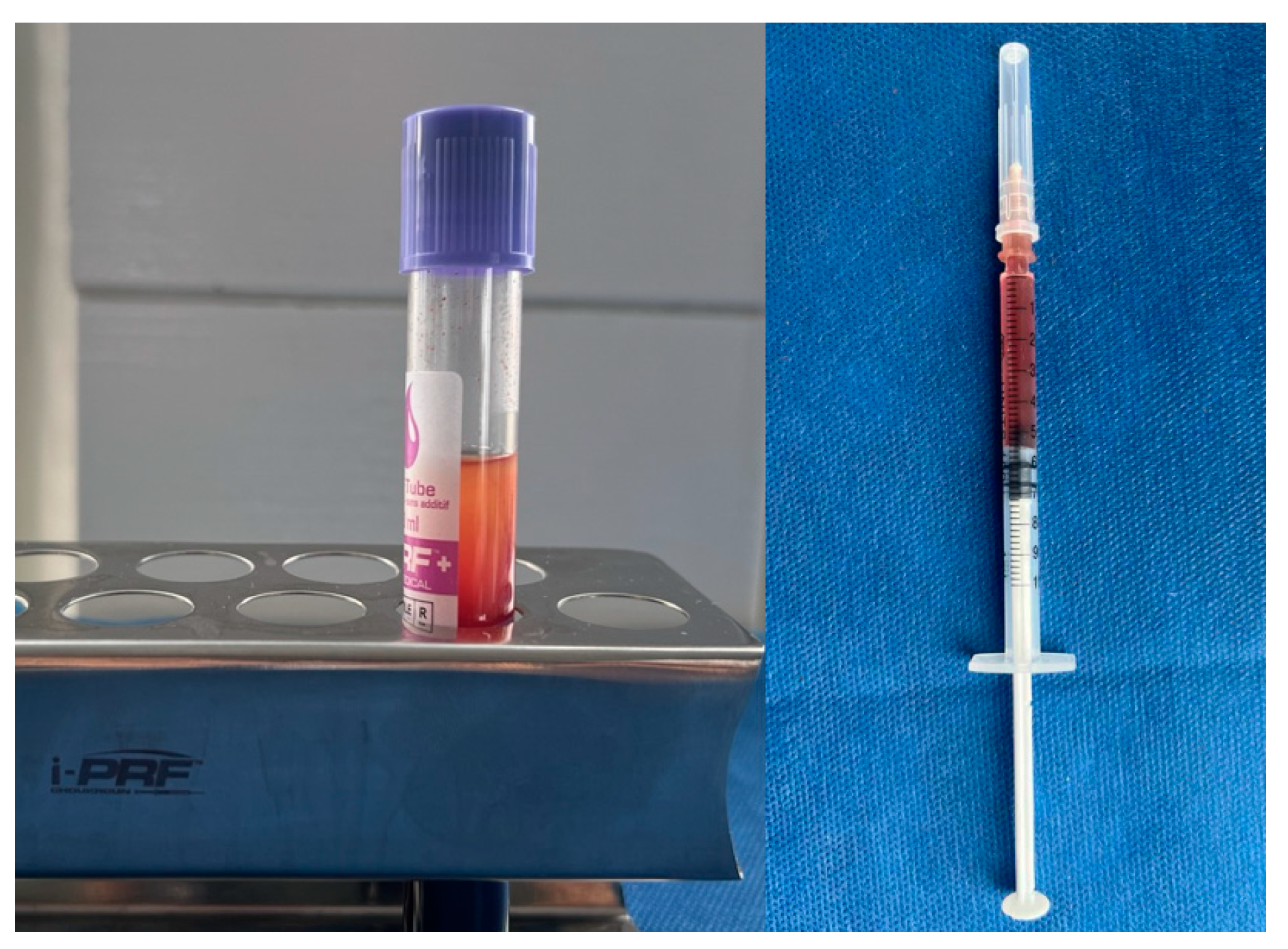

Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) is an autologous blood product widely used in various medical fields, particularly in dentistry. (

Figure 1) Its applications span dental surgery, implantology, periodontology, endodontics, and more. PRF is renowned for its regenerative potential, enhanced angiogenesis, anti-inflammatory properties, and biocompatibility, especially when used with bone grafts.

Recent advancements have improved the optimization of PRF through various centrifugation protocols. There's a growing relevance of increased gingival thickness to both periodontal and peri-implant health, prompting the exploration of minimally invasive methods to enhance the gingival phenotype. Injectable PRF (i-PRF) is a liquid blood product designed for tissue regeneration, offering a non-surgical method for augmenting gingival tissues. (

Figure 2) Its use, either alone or in conjunction with microneedling, has shown positive effects on gingival thickening. Ongoing developments in centrifugation protocols hold the promise of further optimizing PRF applications.

3.1. Characterization of i-PRF

With the increasing popularity of autologous blood products in various fields of dentistry, numerous modifications to the protocols have emerged. The administration of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) typically involves the use of anticoagulants, which can inhibit tissue wound healing and suppress tissue regeneration. This has prompted the exploration of various protocols for platelet-rich fibrin (PRF). The necessity of administering a blood product in liquid form, without the need for bovine thrombin and certain stabilizers, led to the development of a protocol for obtaining the so-called injectable PRF (i-PRF).

For the preparation of injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin (i-PRF), autologous peripheral blood is utilized. Typically, 10 mL tubes without any added biological agents are employed. The blood is centrifuged at a low speed (700 rpm) for 3 minutes (60×g) at room temperature. The supernatant obtained, which constitutes the i-PRF, contains platelets, leukocytes, cytokines, stem cells, and a fibrin matrix polymer. Compared to other autologous blood products, i-PRF has demonstrated an enhanced ability to release higher concentrations of various growth factors, as well as to promote greater fibroblast migration and increased expression of PDGF, TGF-β, and collagen type I. Furthermore, i-PRF is characterized by significantly higher levels of sustained release of PDGF-AA, PDGF-AB, EGF, and IGF-1 over 10 days, compared to Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP). [

10,

11,

12]. Ghanaati et al. discovered that low-speed centrifugation of blood releases a higher number of leukocytes before clot formation. High-speed blood centrifugation typically causes cell populations to move from the top to the bottom of the tube. Therefore, it is hypothesized that decreasing centrifugation forces will result in cell populations remaining in the upper layer of the tube. This is significant because leukocytes found in this layer have the ability to regenerate tissue by attracting and directing different cell types through this process. Injectable PRF also induces higher fibroblast migration and demonstrates significantly higher mRNA levels of TGF-β at day 7, PDGF at day 3, and collagen type 1 expression at both days 3 and 7 post-administration compared to PRP [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

3.2. Clinical Application of i-PRF

The benefits of i-PRF application extend beyond periodontal regeneration to other procedures, including resective ones. Bahar et al. reported improved healing after gingivectomy and gingivoplasty procedures [

16,

17]. The procedure for preparing this blood product involves a specific centrifugation protocol. Mourao recommends drawing 9 to 10 ml of peripheral venous blood into a preservative-free tube and centrifuging it for 2 to 3 minutes at 3300 rpm [

15]. This protocol was modified to centrifugation at 700 rpm for 3 minutes. Injectable platelet-rich fibrin can be administered alone or in combination with a bone substitute for the purpose of bone regeneration [

18,

19].

Promising clinical results have been reported by Ucak Turer, who used i-PRF in conjunction with a coronally positioned flap and connective tissue graft for root coverage of Miller class I and II gingival recessions [

19]. In a clinical trial involving 40 sites with thin gingival phenotype, Fotani et al. drew 5 ml of peripheral blood from each participant. After centrifugation at 700 rpm for 3 minutes, they aspirated the yellow i-PRF layer and immediately injected it into the gingival sulcus. After 1 month and 3 months of follow-up, they observed a remarkable increase in gingival thickness and improvement in keratinized tissue width [

20,

21].

The clinical significance of the periodontal phenotype relates to both the risk of specific tissue problems and the effective resolution of pathological changes. Insufficient gingival thickness in the facial area is a known precursor to gingival recession, whether in the vicinity of natural dental crowns or in areas undergoing restorative, orthodontic, or implantological treatment, as well as in periodontal plastic surgery or non-surgical periodontal therapy [

22]. Therefore, the clinician's ability to recognize the thin gingival phenotype is crucial. Conversely, adequate gingival thickness and a sufficient width of keratinized gingival tissue have predictive value in the implementation of various treatment modalities [

23].

Studies have provided compelling evidence of the positive effects of applying i-PRF on cartilage and bone tissue, dental pulp, tissue healing, periodontal tissues, including parameters characterizing the gingival phenotype such as gingival thickness and keratinized gingival width. The application of i-PRF in dentistry is grounded in its biological effects, which include regenerative potential, increased synthesis of type 1 collagen, enhanced angiogenesis when used in conjunction with a bone graft, tripled osteoblastic proliferation and differentiation, increased cell migration, improved healing of both soft and mineralized tissues, enhanced osteogenic effect, reduced risk of postoperative recessions in coronally positioned flap procedures for deep gingival recessions, increased gingival thickness, periodontal pocket reduction, and loss of clinical attachment during periodontal regeneration procedures, as well as antibacterial activity against Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, among others [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

In the realm of phenotype modification therapy (PhMT), numerous therapeutic strategies have been developed. In recent years, approaches to augment gingival thickness using various injection techniques involving hyaluronic acid, i-PRF, and microneedling (MN) in combination with i-PRF have gained attention. One of the pioneering attempts to utilize i-PRF for papillary height restoration was described by Puri et al. In their study, selected patients were treated with an autologous blood product obtained by centrifuging 10 ml of venous blood for 3 minutes at 700 rpm. The product was then deposited in the desired locations using an insulin syringe. Due to the perishable liquid structure of i-PRF, it is advisable to inject it within 10 to 15 minutes. The protocol involves anesthetizing the treated area, followed by the introduction of the blood product 2-3 mm from the tip of the papilla at a 45-degree angle to the longitudinal axis of the tooth, with the beveled part of the needle directed apically. Results obtained 6 months after the clinical procedure showed a satisfactory filling of the interdental space at the tested sites (ranging from 100% to 66.6%) [

32].

In a study conducted by Ozsagir et al., the effectiveness of i-PRF and MN in combination with i-PRF was compared [

29]. Microneedling, also known as percutaneous collagen induction therapy, involves creating microchannels to facilitate the administration of different substances, thus increasing the contact area. When used concurrently with growth factors from stem cells or i-PRF, microneedling enhances the overall effectiveness of the procedure. Microneedling induces micro injuries in the treated areas, resulting in superficial bleeding, neoangiogenesis, neocollagenogenesis, and tissue regeneration activation [

32,

33]. Microneedling facilitates the penetration of active substances into the target tissue, thereby enhancing the efficacy of the applied substance.The technique was applied to augment the gingival phenotype in patients with thin gingival tissues. At monthly follow-ups over 6 months, the data indicated a statistically significant increase in gingival thickness. The research employed a split-mouth design, comparing areas treated with i-PRF alone to adjacent areas treated with MN in combination with i-PRF. A statistical difference in favor of the latter technique was observed in terms of increasing gingival thickness [

29,

34].

Tiwari et al. focused on the non-surgical modification of the gingival phenotype. They conducted a study on patients with a thin gingival phenotype, drawing 5 ml of peripheral venous blood into a glass tube without an anticoagulant. The tube was then centrifuged at 3300 rpm for 2 minutes. Following centrifugation, the upper yellowish layer containing i-PRF was immediately aspirated into a syringe. i-PRF was injected into the gingival sulcus at the selected site, and the procedure was repeated after 1 week and 2 weeks. Results regarding plaque and gingival index, gingival thickness, and width of keratinized gingiva were reported at the first and third months. A statistically significant increase in gingival thickness and width of keratinized gingiva was observed [

22].

Manasa et al. conducted a split-mouth randomized clinical study on 30 generally healthy participants with thin gingival phenotype, who were treated with i-PRF. i-PRF was injected into the attached gingiva in the tested site, while no procedure was performed in the control site. An increase in attached gingiva was observed after 3 and 6 months post-treatment in the tested sites [

35]. In line with these results, Akolu et al. conducted a clinical study applying i-PRF in 18 sites characterized by thin gingival phenotype and observed a statistically significant increase in both gingival thickness and width of keratinized tissue [

36].

Table 1.

Efficacy of i-PRF – from cell to tissue results.

Table 1.

Efficacy of i-PRF – from cell to tissue results.

| Authors |

Aim |

Results |

Miron et al., 2017 [11]

Karde et al., 2017 [25]

Wang et al.,2018 [26]

Kour et al.,2018 [27]

Xie et al.,2019 [28]

İzol et al.,2019 [29]

Ucak Turer et al.,2020 [30]

Ozsagir et al., 2020 [31]

Puri et al.,2022 [32]

Manasa et al., 2023 [36]

Akolu et al., 2023 [37]

Sidharthan et al.,2024 [32] |

Investigating the fibroblast biocompatibility at 24 h (live/dead assay); migration at

24 h; proliferation at 1, 3, and 5 days, and expression of

PDGF, TGF-β, and collagen 1 at 3 and 7 days by comparing standard PRP and i-PRF.

Evaluating the antimicrobial property, and platelet count of i-PRF compared to PRF, PRP and whole blood.

Comparing both PRP and i-PRF on

osteoblasts viability,

migration, adhesion, proliferation, differentiation and mineralization

when cultured with i-PRF.

Comparing PRP, PRF and I-PRF for their antibacterial effect against Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans.

Aiming to evaluate the regenerative effect of i-PRF on lateral sinus lift procedure.

Exploring the effect of effects of Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin (I-PRF) on root coverage of free gingival graft surgery.

Evaluating the effect of combined connective tissue graft with i-PRF with coronally advanced flap for root coverage of deep Miller Class I or II gingival recessions compared with CTG alone with CAF.

Evaluating the effect of gingival thickness and keratinized tissue width using i--PRF alone and with microneedling in individuals with thin periodontal phenotypes.

Presenting the utilisation of i-PRF as a novel nonsurgical technique for papilla hight reconstruction.

Evaluating the efficacy of injectable platelet-rich fibrin for gingival phenotype modification.

Evaluating the effect of I-PRF on gingival thickness as a minimally invasive

procedure to enhance the periodontal phenotype.

Investigating the effect of micro needling (MN) on gingival thickness (GT) and keratinized tissue width (KTW) in individuals with thin gingival phenotypes, either with or without injectable platelet-rich fibrin (i-PRF). |

The centrifugation protocol is related to higher cell migration and mRNA expression of TGF-β, PDGF, and COL1a2; additional release of growth factors 10 days after application resulting in significantly higher levels of total long-term release of PDGF-AA, PDGF-AB, EGF, and IGF-1 after 10 days.

In vitro study comparing PRP and i-PRF demonstrates better regenerative potential of i-PRF; i-PRF has a significant inhibitory effect on growth of oral bacteria in comparison to other platelet concentrates.

The authors report that i-PRF has more significant influence on osteoblast migration, proliferation and differentiation of compared to PRP.

The authors compare the antimicrobial activity of three platelet concentrates - PRP, PRF, and i-PRF. The results show that PRP and i-PRF are more active as compared to PRF.

A pilot study demonstrating the utilisation of i-PRF as a reliable sinus lift material with potential to shorten the healing time and improving the osteogenesis.

The authors are treating 40 patients with gingival recessions Miller class I or II by dividing them in two equal groups using FGG in the test group and i-PRF additionally to FGG in the experimental group. The post treatment results showed that i-PRF in adjunction to FGG had a positive effect on root coverage in free gingival graft surgery.

The authors reported that the addition of i-PRF to the CAF+CTG gains benefits regarding to the keratinised tissue height and decreasing the recession depth.

The authors explored the utilisation of i-PRF alone and i-PRF with MN for enhancement of GT and observed a statistically significant increase in GT in both groups.

The authors explored the utilisation of i-PRF alone and i-PRF with MN for enhancement of GT and observed a statistically significant increase in GT in both groups at the sixth month.

The authors reported 100% papillary fill after 6 months of injection and reduction in the surface area of the black triangles.

The authors are reporting significant improvement of the GT after application of i-PRF, but they found no significant difference in the width of keratinized gingiva.

The authors reported significant increase of gingival thickness and keratinised width after application of i-PRF after 1 and 3 months after treatment.

The authors are comparing the effect of MN alone and MN with i-PRF for enhancing the GT and KTW. The results after their treatment show that the application of i-PRF in addition to MN demonstrates more favourable outcomes compared to using MN alone in enhancing tissue thickness. |

The application of i-PRF is gaining popularity in both facial and dental aesthetics. One common aesthetic challenge faced by clinicians is the presence of black triangles in the interdental space, often resulting from a reduction in the height of the coronal papillae. Various surgical techniques have been proposed for restoring reduced papillae, each with varying degrees of predictability regarding the final outcome. The search for a non-surgical solution to this problem has led to the use of agents such as hyaluronic acid and i-PRF.

In another study comparing microneedling alone with microneedling in combination with i-PRF, Sidharthan et al. investigated gingival thickness augmentation in 15 systemically healthy individuals. They induced superficial bleeding via a derma pen after applying an anaesthetic gel. i-PRF was then injected into the keratinized gingiva until tissue blanching occurred. The intergroup comparison revealed a statistically significant increase in the group treated with microneedling and i-PRF [

32].

4. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the invasive nature of the procedure, which involves drawing venous blood, and the need for multiple repetitions at regular intervals, this technique offers an alternative to procedures requiring flap preparation, suturing, suture removal, and potentially eliminates the need for a second surgical site - the donor bed of palatal mucosa. Additionally, it may reduce the lengthy recovery period often accompanied by limitations in daily activities and risks such as bleeding, compromised healing, and infection. However, the long-term durability of the results remains unexplored, posing a challenge in assessing the technique's effectiveness over time.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the evaluation of the periodontal phenotype holds extreme importance for periodontists, given the close relationship between periodontal treatment and orthodontic, prosthetic, implantological, and restorative interventions. To enhance clinical outcomes in patients with thin gingival phenotype, various minimally invasive procedures have been introduced, gaining popularity in modern dentistry, particularly in periodontology [

36].

The application of injectable PRF for gingival phenotype augmentation, whether alone or in combination with microneedling, shows promising results in improving gingival thickness and keratinized tissue width. Despite the limitations of i-PRF, such as the need for optimally centrifuged protocols, the method offers an alternative for achieving more predictable results, especially in surgical treatment outcomes where thick mucosal flaps tend to yield more predictable results compared to thin gingival tissues around natural teeth or implants [

38,

39].

Optimized PRF centrifugation protocols have led to the presentation of benefits associated with horizontal centrifugation, demonstrating the potential to achieve up to four times more cells, including leukocytes. The faster speed applied in horizontal centrifugation results in the formation of a buffy layer with an increased number of cells - concentrated PRF (C-PRF). The heightened amount of growth factors in C-PRF invokes greater potential for tissue regeneration and represents a novel field of interest for periodontal phenotype modification [

40]. The biological effects and safety of PRF use make its procedures reliable and efficient in terms of predictable soft tissue augmentation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.P.-T.; methodology, Z.P.-T.; software, Z.P.-T.; validation, Z.P.-T., A.M. and H.M.; formal analysis, Z.P.-T; investigation, Z.P.-T; resources, Z.P.-T...; data curation, Z.P.-T..; writing—original draft preparation, Z.P.-T..; writing—review and editing, Z.P.-T. A.M. and H.M.; visualization, Z.P.-T.; supervision, Z.P.-T., A.M. and H.M.; project administration, Z.P.-T.; funding acquisition, Z.P.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded by the project "Young scientists and postgraduate PhD students -2" First stage [2022-2023].

Data Availability Statement

All available data is published in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kao RT, Curtis DA, Kim DM, Lin GH, Wang CW, Cobb CM et al (2020) American Academy of Periodontology best evidence consensus statement on modifying periodontal phenotype in preparation for orthodontic and restorative treatment. J Periodontol 91(3):289–298. [CrossRef]

- Nagate, R. R., Chaturvedi, S., Al-Ahmari, M. M. M., Al-Qarni, M. A., Gokhale, S. T., Ahmed, A. R., ... & Minervini, G. (2024). Importance of periodontal phenotype in periodontics and restorative dentistry: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health, 24(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Malpartida-Carrillo V, Tinedo-Lopez PL, Guerrero ME, Amaya-Pajares SP, Özcan M, Rösing CK. Periodontal phenotype: a review of historical and current classifications evaluating different methods and characteristics. J Esthetic Restor Dentistry. 2021;33. [CrossRef]

- Babay N, Alshehri F, Al Rowis R. Majors highlights of the new 2017 classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions. Saudi Dent J. 2019 Jul;31(3):303-305. Epub 2019 Apr 23. PMID: 31337931; PMCID: PMC6626283. [CrossRef]

- Jepsen S, Caton JG, Albandar JM, et al. Periodontal manifestations of systemic diseases and developmental and acquired conditions: consensus report ofworkgroup 3 of the 2017WorldWorkshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol 2018;89(Suppl 1):S237-S248.

- Sculean A, Romanos G, Schwarz F, Ramanauskaite A, Leander KP, Khoury F, et al. Soft-tissue management as part of the surgical treatment of periimplantitis: a narrative review. Implant Dent. 2019;28. [CrossRef]

- Barootchi S, Tavelli L, Zucchelli G, Giannobile WV, Wang HL. Gingival phenotype modification therapies on natural teeth: a network meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2020;91. [CrossRef]

- Chambrone L, Garcia-Valenzuela FS. Periodontal phenotype modification of complexes periodontal-orthodontic case scenarios: a clinical review on the applications of allogenous dermal matrix as an alternative to subepithelial connective tissue graft. J Esthetic Restor Dentistry. 2023;35. [CrossRef]

- Santamaria P, Paolantonio M, Romano L, Serroni M, Rexhepi I, Secondi L, et al. Gingival phenotype changes after different periodontal plastic surgical techniques: a single-masked randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Choukroun J, Ghanaati S. Reduction of relative centrifugation force within injectable platelet-rich-fibrin (PRF) concentrates advances patients’ own inflammatory cells, platelets and growth factors: the first introduction to the low-speed centrifugation concept. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018 Feb; 44:87–95.

- Miron RJ, Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Hernandez M, et al. Injectable platelet rich fibrin (i-PRF): opportunities in regenerative dentistry? Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21(8):2619-2627. [CrossRef]

- Crisci A, Manfredi S, Crisci M. Fibrin rich in Leukocyte-Platelets (L-PRF) and Injectable Fibrin Rich Platelets (I-PRF), two opportunity in regenerative surgery: Review of the sciences and literature. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) 2019, 18(4), 66-79.

- Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence to support its use. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery: official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons 2004;62: 489–496.

- Ghanaati S, Booms P, Orlowska A, Kubesch A, Lorenz J, Rutkowski J, Landes C, Sader R, Kirkpatrick C, Choukroun J. Advanced platelet-rich fibrin: a new concept for cell-based tissue engineering by means of inflammatory cells. The Journal of oral implantology 2014; 40:679–689. [CrossRef]

- Bielecki T, Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Everts PA, Wiczkowski A (2012) The role of leukocytes from L-PRP/L-PRF in wound healing and immune defense: new perspectives. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 13: 1153–1162.

- Gollapudi M, Bajaj P, & Oza RR. Injectable platelet-rich fibrin-a revolution in periodontal regeneration. Cureus 2022;14(8). [CrossRef]

- Bahar Ş Ç, Karakan NC, & Vurmaz A. The effects of injectable platelet-rich fibrin application on wound healing following gingivectomy and gingivoplasty operations: single-blind, randomized controlled, prospective clinical study. Clinical Oral Investigations 2024;28(1), 85. [CrossRef]

- Mourão CF de AB, Valiense H, Melo ER, Mourão NBMF, Maia MD-C: Obtention of injectable platelets rich-fibrin (i-PRF) and its polymerization with bone graft: technical note. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2015, 42:421-3. [CrossRef]

- Ucak Turer O, Ozcan M, Alkaya B, Surmeli S, Seydaoglu G, Haytac MC. Clinical evaluation of injectable platelet-rich fibrin with connective tissue graft for the treatment of deep gingival recession defects: A controlled randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(1):72-80. [CrossRef]

- Fotani S, Shiggaon LB, Waghmare A, Kulkarni G, Agrawal A, & Tekwani R. Effect of injectable platelet rich fibrin (i-PRF) on thin gingival biotype: A clinical trial. J Appl Dent Med Sci 2019; 5(2), 9-16.

- Malpartida-Carrillo V, Tinedo-Lopez PL, Guerrero ME, Amaya-Pajares SP, Özcan M, Rösing CK. Periodontal phenotype: A review of historical and current classifications evaluating different methods and characteristics. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2021;33(3):432-445. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari V, Agarwal S, Goswami V, Gupta B, Khiraiya N & Soni V R. Effecton injectable platelet rich fibrin in augmentation of thin gingival biotype: A clinical trial. International Journal of Health Sciences 2022; 6(S1), 640-648. [CrossRef]

- Blog, I. T. I. Why we should assess gingival phenotypes in daily practice–gingival phenotype assessment tools & gingival phenotype classifications revisited.

- Miron RJ, Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Hernandez M, et al. Injectable platelet rich fibrin (i-PRF): opportunities in regenerative dentistry? Clin Oral Investig 2017; 21: 2619-27.

- Karde PA, Sethi KS, Mahale SA, Khedkar SU, Patil AG, Joshi CP. Comparative evaluation of platelet count and antimicrobial efficacy of injectable platelet-rich fibrin with other platelet concentrates: An in vitro study. J Indian Soc Periodontol 2017; 21:97-101. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Zhang Y, Choukroun J, Ghanaati S, Miron RJ. Effects of an injectable platelet-rich fibrin on osteoblast behavior and bone tissue formation in comparison to platelet-rich plasma. Platelets 2018; 29:48-55. [CrossRef]

- Kour P, Pudakalkatti PS, Vas AM, Das S, Padmanabhan S. Comparative evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of platelet-rich plasma, platelet-rich fibrin, and injectable platelet-rich fibrin on the standard strains of porphyromonas gingivalis and aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Contemp Clin Dent 2018; 9:325-30. [CrossRef]

- Xie H, Xie YF, Liu Q, Shang LY, Chen MZ. Bone regeneration effect of injectable-platelet rich fibrin (I-PRF) in lateral sinus lift: A pilot study. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue 2019; 28, 71–75.

- İzol B S & Üner D. A New Approach for Root Surface Biomodification Using Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin (I-PRF). Medical Science Monitor. 2019; 25, 4744–4750. [CrossRef]

- Ucak Turer O, Ozcan M, Alkaya B, Surmeli S, Seydaoglu G, Haytac MC. Clinical evaluation of injectable platelet rich fibrin with connective tissue graft for the treatment of deep gingival recession defects: A controlled randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2020; 47:72-80 İzol B S & Üner D. A New Approach for Root Surface Biomodification Using Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin (I-PRF). Medical Science Monitor. 2019; 25, 4744–4750. [CrossRef]

- Ozsagir ZB, Saglam E, Sen Yilmaz B, Choukroun J, Tunali M. Injectable platelet-rich fibrin and microneedling for gingival augmentation in thin periodontal phenotype: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 489–499. [CrossRef]

- Puri K, Khatri M, Bansal M, Kumar A, Rehan M, Gupta A. A novel injectable platelet-rich fibrin reinforced papilla reconstruction technique. J Indian Soc Periodontol 2022; 26:412-7. [CrossRef]

- Sidharthan S, Dharmarajan G, Iyer S, Poulose M, Guruprasad M, & Chordia D. Evaluation of microneedling with and without injectable-platelet rich fibrin for gingival augmentation in thin gingival phenotype-A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research 2024;14(1), 49-54. [CrossRef]

- Alster TS, Graham PM. Microneedling: a review and practical guide. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Mar 1;44(3):397–404. [CrossRef]

- Ozsagir ZB, Tunali M. Injectable platelet-rich fibrin: a new material in medicine and dentistry. Mucosa 2020; 3:27-33. [CrossRef]

- Manasa B, Baiju KV, & Ambili R. Efficacy of injectable platelet-rich fibrin (i-PRF) for gingival phenotype modification: a split-mouth randomized controlled clinical trial. Clinical Oral Investigations 2023; 27(6), 3275-3283. [CrossRef]

- Akolu P, Lele P, Dodwad V, Khot T, Kundoo A, & Bhosale N. COMPARATIVE EVALUATION OF THE EFFECT OF INJECTABLE PLATELET RICH FIBRIN (I-PRF) ON GINGIVAL THICKNESS IN INDIVIDUALS WITH THIN PERIODONTAL PHENOTYPE–A CLINICAL STUDY. Eur. Chem. Bull. 2023, 12(Special Issue 6), 6520-6530.

- Hwang D, Wang HL. Flap thickness as a predictor of root coverage: A systematic review. J Periodontol 2006; 77:1625-34.

- Puisys A, Linkevicius T. The influence of mucosal tissue thick..ening on crestal bone stability around bone-level implants. A prospective controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res 2015; 26:123-9.

- Miron RJ, Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Sculean A, Zhang Y. Optimization of platelet-rich fibrin. Periodontol 2000. 2023; 00:1-13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).