1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global public health challenge that tests the resilience of health systems worldwide and has been identified by the European Commission as one of the top three priority health threats in July 2022 [

1]. In addition, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized AMR as one of the top 10 global public health threats in 2019 [

2].

Infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria are often associated with poor clinical outcomes, including increased morbidity and mortality, longer hospital stays, and ultimately high healthcare costs [

3]. Among the Enterobacterales species,

Klebsiella pneumoniae is the predominant multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogen, with its resistant genes carried on plasmids are easily spread, especially in the hospital setting [

4]. The rate of carbapenem resistance among

Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) strains varies regionally. In Europe, the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) shows that the national percentages of CRKP isolates from invasive infections vary from 0% to over 60% [

5]. Specifically, the rate of CRKP isolates reached 69.7% in Greece in 2023 [

6]. Among the most clinically significant carbapenemases that hydrolyze carbapenems and have been reported globally are KPC, OXA-48 and the MBLs VIM, IMP, and NDM [

7]. An alarming increase in NDM carbapenemases has been observed in recent years, with co-occurrence of NDM with KPC and other serine beta-lactamases also being reported [

8]. Therapeutic options for the treatment of MDR and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Enterobacteriaceae infections are very limited [

9]. Currently, antibiotic options for treating of carbapenem-resistant

Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are limited, with polymyxins, tigecycline, fosfomycin, and aminoglycosides being the main stays of therapy. However, resistance to these antibiotics is increasing [

10]. Fortunately, the development of several new β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor (BLBLI) combinations, such as ceftazidime/avibactam (CZA), meropenem/vaborbactam (M/V), and imipenem/relebactam (I/R), offers alternative treatment options [

11]. CZA inhibits Ambler class A, C, and D β-lactamases, while M/V and I/R have an activity against class A and class C β-lactamases. However, these combinations are not effective against strains producing MBL, such as NDM, VIM, and IMP [

12,

13,

14]. Avibactam is a diazabicyclooctane molecule and a beta-lactamase inhibitor that protects ceftazidime from hydrolysis by serine beta-lactamases, such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL),

Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) and OXA-48-like. However, avibactam is not active against New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM) and other metallo-beta-lactamases (MBL) [

15]. Vaborbactam is a novel cyclic boronic acid inhibitor that restores meropenem activity against producers of numerous class A and C β-lactamases, but it is inactive against MBL and OXA-48 producers [

16].

Relebactam produces a dose-dependent synergy with imipenem against CRE-producing KPC or combinations of AmpC or ESBL with reduced permeability but is poorly effective against MBL and OXA-48 producers [

17]. I/R may also be active against CZA-resistant

Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates carrying a variant KPC-3 without major OmpK36 mutations [

18].

In conclusion, the management of CRKP infections, especially those caused by MBL-producing bacteria is extremely challenging because of limited treatment options. Investigating the synergistic potential of combination therapies in vitro may help identify regimens that could offer clinical benefits. Indeed, synergy testing methods have been utilized in several studies to assess the interaction of antibiotic combinations in vitro [

9,

13,

14]. Antibiotic combinations may provide a broader spectrum, not only in terms of coverage but also to overcome multiple resistance mechanisms and the limitations of individual drug classes. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that synergy-guided antimicrobial combination therapy against MDR Gram-negative bacteria was significantly associated with survival [

19].

Τhe objective of this study was to assess the in vitro synergy between the new antibacterial agents CZA, M/V and I/R combined with aztreonam (AZM), colistin (COL) and fosfomycin (FOS) against MBL producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. This was done to identify the most effective combination regimen that could offer alternative treatment options for infections caused by MBL carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae.

2. Materials-methods:

A total of 169 MBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae single clinical isolates (89 NDM, 66 NDM+KPC and 14 VIM) were included in the study, collected between 1 March 2023 and 30 September 2024. Of these, 86 were isolated from urine, 45 from blood, 27 from wound cultures and 11 from bronchoalveolar secretions. The samples were collected from the Internal medicine department (n=65), from the ICU unit (n=52), Surgery (n=25), Urology (n=21) and the Orthopedic clinic (n=6).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using the Vitek2 (bioMérieux, France), while colistin susceptibility was confirmed by the broth microdilution method (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Teramo). MIC test strips (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Teramo, Italy) were used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of six antimicrobial agents: AZM, FOS, COL, CZA, M/V and I/R. Antimicrobial resistance rates were calculated according to the EUCAST breakpoints v 12.0 (2022).

The interactions of antimicrobial agent combinations were determined based on the calculated fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) [

20].

We used AZM, FOS and COL as the primary antibacterial agents in combination with CZA, M/V and IR. Nine combinations were tested, including CZA+AZM, CZA+FOS, CZA+COL, M/V+AZM, M/V +FOS, M/V +COL, I/R+AZM, I/R+FOS and I/R+COL.

The MIC strip of the first antimicrobial (antimicrobial agent A) was placed on a Mueller-Hinton agar plate at room temperature and removed after 1 hour. The MIC strip of the second antimicrobial (antimicrobial agent B) was then placed directly over the imprint of A with the highest concentrations coinciding. At the same time, plates with an MIC strip of each antimicrobial alone were prepared. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24hours, and the MICs of each drug alone, as well as the MICs of the drugs in combination, were assessed with the use of the respective MIC strip/scales. The results were interpreted using the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) [

21], calculated as:

FICI = FIC agentA + FIC agentB = MIC AB /MIC A + MIC BA /MIC B

The results were interpreted as follows: FICI ≤0.5 indicated synergy, >0.5–≤1 additivity, >1–≤4 indiffierence and FICI >4 antagonism [

22].

Detection of carbapenemases was performed using the immunochromatographic NG-Test/CARBA-5 method (NG-Biotech), while carbapenemases in blood and bronchoalveolar specimens were confirmed by the multiplex PCR BioFire FilmArray BCID2 and pneumonia systems, respectively.

3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis involved descriptive statistics along with relevant bar charts for the tabulation and graphical representation of frequencies for categorical outcomes. Pairwise comparisons for contingency tables were conducted via McNemar’s test. The chi-squared test was used for testing the hypothesis of independence between categorical variables. P-values less than 0.05 after adjusting for multiplicity via the Bonferroni method were considered statistically significant. Standard spreadsheet applications and R version 4.4.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) were used for data analysis.

4. Results

The isolates displayed high rates of resistance to major classes of tested antimicrobials, with 100% resistance to CZA, M/V and I/R. MIC values were ranging from 0.125–256 μg/ml and 1–256 μg/ml for AZM and FOS, respectively. For colistin MIC values ranged from 0.125 to 64 μg/ml (

Table 1).

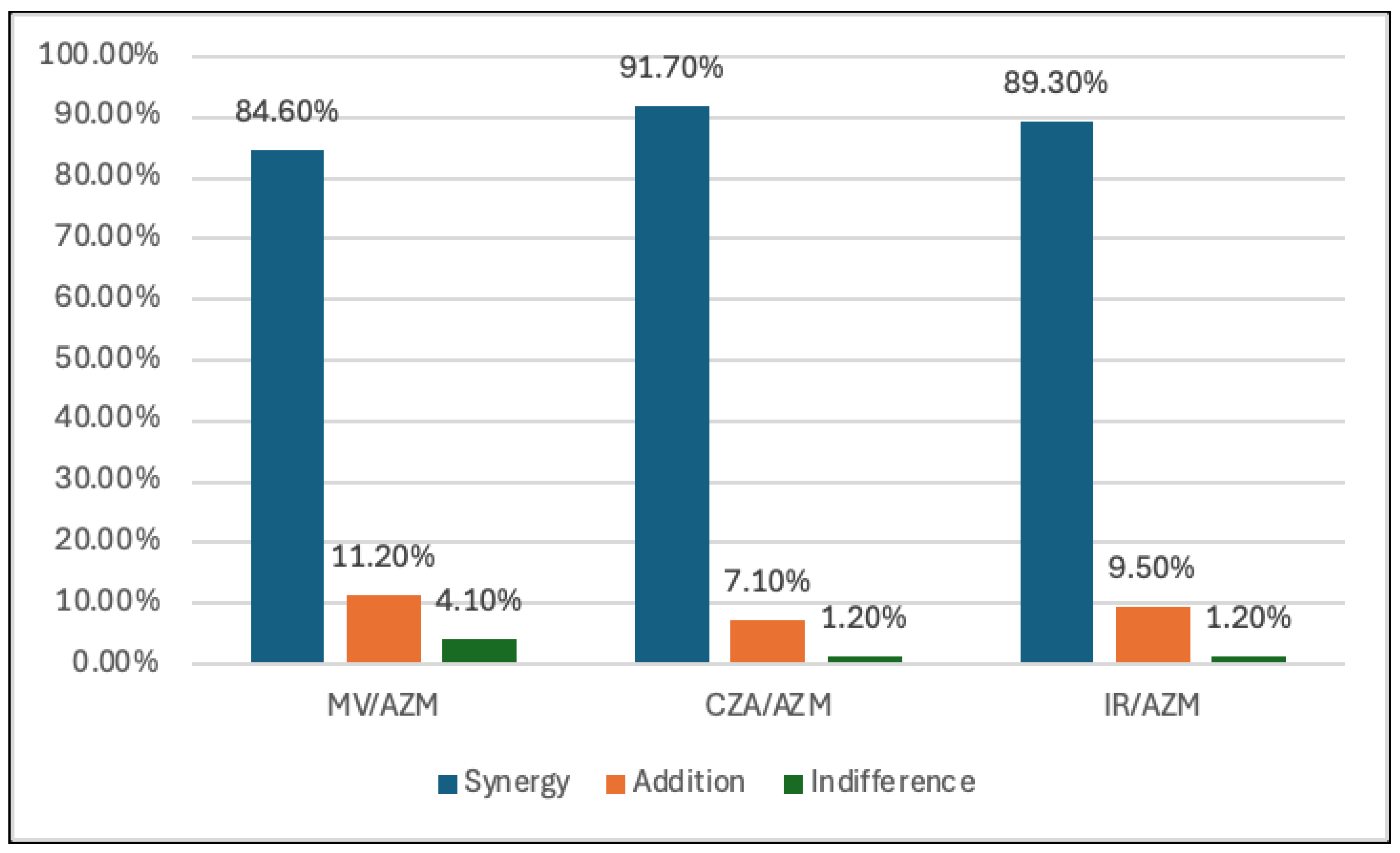

The broadest synergistic effect of the antibiotic combinations in 169 isolates was determined in combinations between CZA, M/V, I/R and AZM. (91.7%, 84% and 89.3%, respectively). (

Table 2,

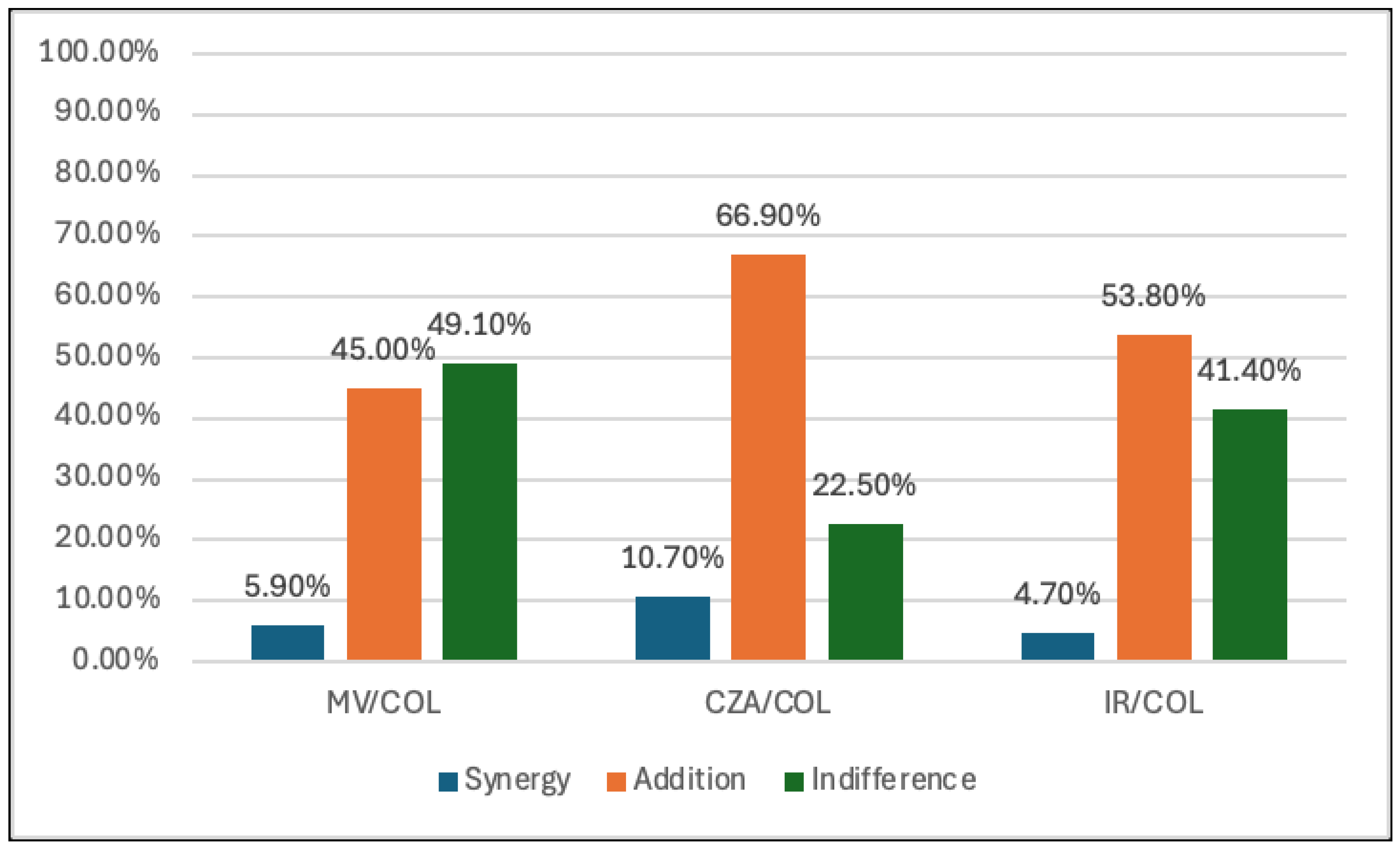

Figure 1). In contrast, the lowest synergy was observed in the combination of CZA, M/V, I/R and COL (10.7%, 5.9% and 4.7%, respectively). However, COL showed to have an additive effect with CZA, M/V and I/R. (66.9%, 45% and 53.8%, respectively). (

Table 2,

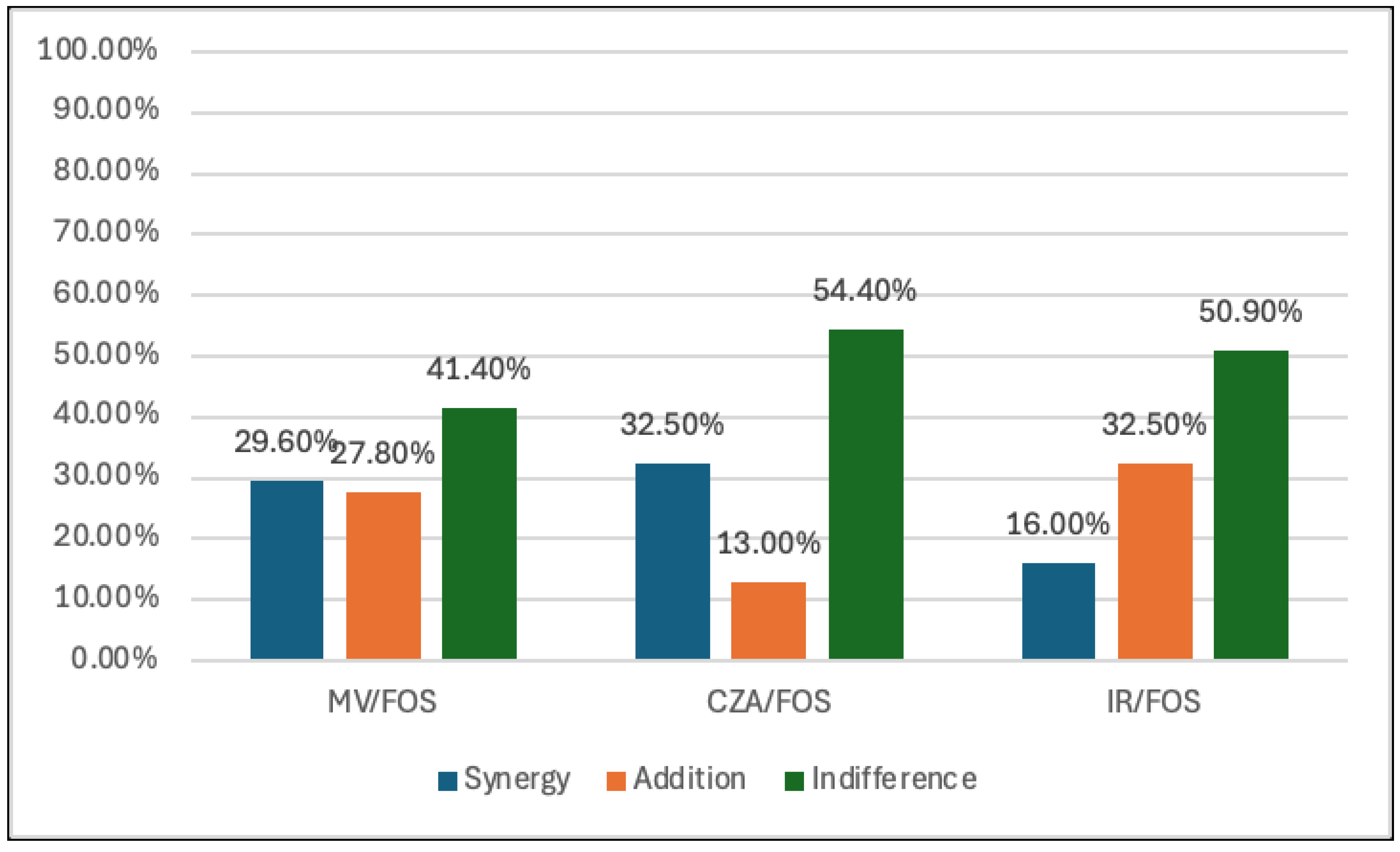

Figure 2). Fosfomycin displayed the highest synergy with CZA (32.5%) and M/V (29.6%), while the synergy with I/R was 16%. In addition, the additivity effect between FOS and CZA, M/V and I/R was 13%, 27.8% and 32.5%, respectively (

Table 2,

Figure 3). None of the combinations of AZM and COL displayed antagonism against any of the tested strains. Only two isolates demonstrate an antagonistic effect between FOS and M/V (1.2%) and one between FOS and I/R (0.6%).

P-values less than 0.05 showcase disagreement of drug effects on the same subjects, revealing drug sensitivity differences and differences in synergistic effects. The McNemar test results reveal statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) across most of the drug comparisons (

Table 3). Τhe only combination in which no statistically significant difference was observed, was the one with COL plus M/V and I/R, where the p-value was 0.072.

5. Discussion

The rising number of CRKP, especially strains producing MBL, shows an urgent public health problem for the treatment of MDR infections. The results of our study show that MBL-producing CRKP strains exhibit resistance to AZM (92.3%) and FOS (85.2%). We also discovered a 100% resistance to CZA, M/V and I/R among isolates in our research sample group. During the shortage of AZM at our hospital, we decided to explore alternative antibiotic combinations. Our main goal was to investigate various antibiotic combinations that could work together effectively to address the resistance observed in these strains.

5.1. Aztreonam and Combinations

Interestingly, the combination of AZM with other antibiotics, particularly those targeting beta-lactamases, shows considerable promise. Specifically, the combination of AZM plus CZA showed the highest degree of synergy (91.7%), followed by AZM plus IR (89.3%) and AZM plus M/V (84.6%).

The synergy observed with the combination of AZM plus CZA, I/R and M/V in our research aligns with findings from other studies. These are the indicated effectiveness of AZM when combined with beta-lactamase inhibitors like avibactam, which neutralize the beta-lactamases produced by multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales [

23,

24,

25,

26], particularly CRKP [

27,

28] and MBL-producing

Klebsiella pneumoniae strains [

27,

29]. This combination helps in restoring susceptibility to aztreonam by protecting it from hydrolysis (30).

In a recent observational study by Falcone et al. [

23], it was found that the combination of CZA plus AZM provides a therapeutic advantage over other antimicrobial agents in patients with bloodstream infections caused by MBL-producing Enterobacterales, especially

K. pneumoniae strains. This combination is already considered one of the most effective options for treating MBL infections and warrants further investigation, particularly in the context of NDM-producing strains, where treatment choices are limited.

Li et al. [

31] observed that the combination of AZM plus CZA, M/V, or I/R demonstrated good antibacterial activity against CRKP strains co-producing MBL and KPC, with synergistic effects noted for AZM plus CZA or M/V. Notably, AZM plus M/V or I/R exhibited comparable bactericidal effects, achieving a reduction of bacteria >3.78 log10 CFU/mL, while more frequent dosing may be necessary to overcome bacterial regrowth observed in some strains at 24 hours. Additionally, Belati et al. [

32] have suggested in an observational study that the combination of AZM plus M/V could be an effective treatment option for severe CZA resistant

Klebsiella pneumoniae infections, as it has shown efficacy in both microbiological and clinical cure of MBL infections and provides an effective treatment for KPC infections.

According to these findings, aztreonam may play a critical role in combination therapies for CRE, mainly Klebsiella pneumoniae strains, providing hope for managing multidrug-resistant infections.

5.2. Fosfomycin and Combinations

In our study, the combination of FOS plus CZA, M/V and I/R showed variable synergy rates against CRKP strains. Specifically, the FOS plus CZA combination exhibited a synergy rate of 32.5%, while FOS plus M/V and FOS plus I/R showed synergy rates of 29.6% and 16%, respectively. These rates were lower than those observed for the combination of AZM plus CZA, M/V and I/R, which demonstrated more favorable synergy in our study.

Despite the relatively low frequency of synergy, FOS demonstrated superior synergistic activity compared to COL-based regimens. Interestingly, the combination of FOS plus I/R and M/V produced additive effects with rates of 32.5% and 27.8%, respectively. However, these combinations also exhibited moderate proportions of indifferent interactions, along with occasional low-level antagonism (1-2 cases). These findings suggest that while the synergy rates for FOS-based combinations may not always be strikingly high, they may still offer enhanced bactericidal activity compared to monotherapy.

In the study of Wu et al. [

27], a significant synergistic effect between the combination of FOS and CZA was demonstrated, particularly against MBL-producing CRKP strains, achieving a synergy rate exceeding 60%. Additionally, Ojdana et al. [

33] evaluated the synergistic effects of CZA in combination with tigecycline, ertapenem, and FOS against 19 CRKP strains using the E-test MIC ratio synergy method. They found that FOS combined with CZA showed the most significant synergistic effects, particularly against NDM-producing strains.

However, there is limited published research on the synergistic effects of FOS combined with CZA, M/V, or I/R specifically for NDM-producing CRKP strains. Most studies have focused on KPC-producing strains. Among them, Xu et al. [

34] highlighted that the combination of FOS plus I/R can be an effective alternative for treating carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative infections, including KPC-producing

Klebsiella pneumoniae and

Acinetobacter baumannii. Oliva et al. [

35] assessed the effectiveness of CZA monotherapy versus FOS plus CZA combination therapy in bloodstream infections caused by KPC-producing

K. pneumoniae. They found no significant differences in 30-day mortality (p = 0.807) or clinical cure rates (p = 0.120). However, in vitro, they demonstrated a high level of synergy between FOS and M/V, which may have contributed to the resolution of endovascular infections. Additionally, Fois et al. [

36] conducted a study comparing the efficacy of FOS plus CZA combination therapy versus monotherapy for treating nosocomial pneumonia. While no significant reduction in mortality was observed with combination therapy, they found that CRE (KPC, OXA-48) were more frequently treated with FOS plus CZA than with CZA alone (p = 0.03).

The findings from these studies reinforce the potential of FOS, especially when combined with newer β-lactams, as a promising treatment for resistant infections, warranting further investigation in clinical trials.

5.3. Colistin and Combinations

In our study, the combinations of COL plus CZA, M/V and I/R showed low synergy but exhibited a better additive effect than FOS pairings. Specifically, the combination of COL plus CZA showed a synergy rate of 10.7%, with the additive effect exhibiting 66.9% and an indifference effect rate of 22.5%. Similarly, the combination of COL plus M/V showed a synergy rate of 5.9%, with the majority of interactions being additive (45%) and a substantial portion showing indifference (49%). In the combination of COL plus I/R, the synergy rate was even lower at 4.7%, but additive effects still accounted for the majority, 53.8%, with indifference observed in 41.4% of the combinations.

There is no other published research on the synergistic effects of COL combined with CZA, M/V, or I/R for NDM-producing CRKP strains. The limited number of available in vitro studies has mainly focused on KPC-producing carbapenem-resistant strains using time-kill assays [

37,

38,

39]. One of these studies is by Shields et al. [

37], which is consistent with our results on synergistic effects. They found a 13% synergy rate and notable antagonism (46%) when combining COL plus CZA against CRE, but this combination did not provide any advantage over CZA alone. Wang et al. [

38] study similarly reported that the combination of COL plus CZA did not significantly improve antimicrobial activity in KPC-producing

Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. However, partial synergism of this combination was observed in 43% of isolates and additivity was found in 40% of isolates, as shown by FICI synergistic activity testing.

On the other hand, the study by Rogers et al. [

39] observed that the combination of COL plus CZA exhibited synergy in vitro, independent of the ompK36 genotype, with M/V killing activity enhanced by the addition of COL and FOS in the presence of porin mutations. Additionally, the synergy rates for the combination of COL plus M/V were significantly higher than for all other combinations combined (16%; p = 0.002) against KPC-producing

Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Despite these findings, the effectiveness of the combinations of COL plus CZA, M/V and I/R should be interpreted cautiously, as the observed rates of synergy tend to be low to modest, with additive effects often being more prominent. This suggests that while COL-based combinations show promise, they may not consistently provide enhanced antimicrobial activity across all strains. Furthermore, in vitro and clinical studies are needed to better understand the potential of COL-based combination therapies for managing resistant infections, especially those caused by strains such as NDM-producing carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae.

The McNemar test results reveal statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) across most of the drug comparisons (

Table 3), varying in how they classify the combinations of synergy, addition, and indifference with the exception of the combination of COL plus M/V and I/R, where the p-value is 0.072, indicating no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05).

A limitation of our study is the use of the FICI test based on MIC values to investigate synergy, rather than the time-kill assay, which provides information on bactericidal activity. Additionally, our analysis was conducted at a single site and involved only a limited number of MBL-producing CRKP strains, without including KPC-producing CRKP strains. Also, the observed in vitro synergy does not always translate to in vivo effects, highlighting the importance of conducting more clinical studies to determine the therapeutic efficacy and risks of such combinations.

6. Conclusions

In our study, the strongest synergistic effects were observed with the combination of AZM plus CZA, MV, and IR, followed by combinations of FOS plus CZA, MV, and IR, suggesting promising therapeutic options for MBL-producing CRKP infections. Additionally, COL-based combinations with CZA, MV, and IR provided a better additive effect, emphasizing the need for tailored therapeutic strategies. These combination therapies present promising new options for the treatment of MBL-producing CRKP infections; however, further clinical studies are required to confirm their efficacy and safety.

References

- Aljeldah, M.M. Antimicrobial Resistance and Its Spread Is a Global Threat. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iftikhar, Qayum. Top ten global health threats for 2019: the WHO list. JRMI.

- Exner, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Christiansen, B.; et al. Antibiotic resistance: what is so special about multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria? GMS Hyg Infect.Control. 2017, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Algammal, A.; Hetta, H.F.; Mabrok, M.; Behzadi, P. Editorial: Emerging multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens “‘superbugs’”: A rising public health threat. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1135614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae,secondupdate–26September2019 https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/carbapenem-resistant-enterobacteriaceae-second-update.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control 2023. Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases. []. Available online: https://atlas.ecdc.europa.eu/public/index.aspx?Dataset=27&HealthTopic=4. (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Hammoudi Halat, D.; Ayoub Moubareck, C. The Current Burden of Carbapenemases: Review of Significant Properties and Dissemination among Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020, 9, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. Epidemiology of β-lactamase-producing pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00047–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakthavatchalam, YD.; Shankar, A. ; DPM, Sethuvel.; Asokan, K.; Kanthan, K.; Veeraraghavan, B. Synergistic activity of fosfomycin–meropenem and fosfomycin–colistin against carbapenem resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: an in vitro evidence. Future Sci, 2020; 6, 461–468. [Google Scholar]

- Giacobbe, D. R.; Del Bono, V.; Trecarichi, E. M.; De Rosa, F. G.; Giannella, M.; Bassetti, M.; et al. Risk factors for bloodstream infections due to colistin-resistant KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: results from a multicenter case-control-control study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015; 21, 1106, e1–1108.e1. [Google Scholar]

- Doi, Y. Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2019, 69, S565–S575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, RK.; Nguyen, MH.; Chen, L.; Press, EG.; Potoski, BA.; Marini, RV.; et al. Ceftazidime-Avibactam Is Superior to Other Treatment Regimens against Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, A.; Campanella, E.; Stracquadanio, S.; Calvo, M.; Migliorisi, G.; Nicolosi, A.; Cosentino, F.; Marletta, S.; Spampinato, S.; Prestifilippo, P.; et al. et al. Ceftazidime/Avibactam and Meropenem/Vaborbactam for the Management of Enterobacterales Infections: A Narrative Review, Clinical Considerations, and Expert Opinion. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023, 12, 1521. [Google Scholar]

- Biagi, M.; Lee, M.; Wu, T.; Shajee, A.; Patel, S.; Deshpande, L. M.; Mendes, R. E.; & Wenzler, E.; Wenzler, E. Aztreonam in combination with imipenem-relebactam against clinical and isogenic strains of serine and metallo-β-lactamase-producing enterobacterales. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2022, 103, 115674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. B-lactams and B-lactamase inhibitors: An overview. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a025247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, L.A.; Henig, O.; Patel, T.S.; et al. Overview of meropenem-vaborbactam and newer antimicrobial agents for the treatment of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae Infect Drug Resist. 2018; 11, 1461–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Lucasti, C.; Vasile, L.; Sandesc, D.; et al. Phase 2, Dose-ranging study of relebactam with imipenem-cilastatin in subjects with complicated intra-abdominal infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6234–6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidar, G.; Clancy, CJ.; Chen, L.; et al. Identifying spectra of activity and therapeutic niches for ceftazidime-avibactam and imipenem-relebactam against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00642–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardakas, K.Z.; Athanassaki, F.; Pitiriga, V.; Falagas, M.E. Clinical relevance of in vitro synergistic activity of antibiotics formultidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections: A systematic review. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 17, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laishram, S.; Pragasam, A.K.; Bakthavatchalam, Y.D.; Veeraraghavan, B. An update on technical, interpretative and clinical relevance of antimicrobial synergy testing methodologies. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2017, 35, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.K.; Moellering, R.C.; Eliopoulos, G.M. Antimicrobial combinations. In Antimicrobials in Laboratory Medicine, 5th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA. 2005; pp. 365–435. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, T.; Cai, Y.; Liang, B.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. In vitro activities of combinations of rifampin with other antimicrobials against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015, 2015 59, 1466–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; Daikos, GL.; Tiseo, G.; Bassoulis, D.; Giordano, C.; Galfo, V.; Leonildi, A.; Tagliaferri, E.; Barnini, S.; Sani, S.; et al. Efficacy of Ceftazidime-avibactam Plus Aztreonam in Patients With Bloodstream Infections Caused by Metallo-β-lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales. Clin Infect Dis. 2021, 72, 1871–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauncajs, M.; Bielec, F.; Malinowska, M.; Pastuszak-Lewandoska, D. Aztreonam Combinations with Avibactam, Relebactam, and Vaborbactam as Treatment for New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales Infections—In Vitro Susceptibility Testing. Pharmaceuticals. 2024, 17, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, M.; Wu, T.; Lee, M.; Patel, S.; Butler, D.; Wenzler, E. Searching for the Optimal Treatment for Metallo- and Serine-β-Lactamase Producing Enterobacteriaceae: Aztreonam in Combination with Ceftazidime-avibactam or Meropenem-vaborbactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01426–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, R.; Kader, O.; Shawky, S.; Rezk, S. Ceftazidime-Avibactam plus aztreonam synergistic combination tested against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales characterized phenotypically and genotypically: a glimmer of hope. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2023, 22, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, W.; Chu, X.; Zhang, J.; Jia, P.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Q. Effect of ceftazidime-avibactam combined with different antimicrobials against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiol Spectr. 2024, 12, e0010724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayol, A.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L.; Dubois, V. Ceftazidime/avibactam alone or in combination with aztreonam against colistin-resistant and carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018, 73, 542–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraki, S.; Mavromanolaki, VE.; Moraitis, P.; Stafylaki, D.; Kasimati, A.; Magkafouraki, E.; Scoulica, E. Ceftazidime-avibactam, meropenen-vaborbactam, and imipenem-relebactam in combination with aztreonam against multidrug-resistant, metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021, 40, 1755–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sy, S. K.; Beaudoin, M. E.; Zhuang, L.; Löblein, K. I.; Lux, C.; Kissel, M.; Tremmel, R.; Frank, C.; Strasser, S.; Heuberger, J. A.; et al. In vitro pharmacokinetics/ pharmacodynamics of the combination of avibactam and aztreonam against MDR organisms. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2016; 71, 1866–1880. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Long, W.; Liang, X.; Yang, Y.; Gong, X.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X. Activities of aztreonam in combination with several novel β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains coproducing KPC and NDM. Front Microbiol. 2024, 15:1210313.

- Belati, A.; Bavaro, DF.; Diella, L.; De Gennaro, N.; Di Gennaro, F.; Saracino, A. Meropenem/Vaborbactam Plus Aztreonam as a Possible Treatment Strategy for Bloodstream Infections Caused by Ceftazidime/Avibactam-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: A Retrospective Case Series and Literature Review. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022, 11, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojdana, D.; Gutowska, A.; Sacha, P.; Majewski, P.; Wieczorek, P.; Tryniszewska, E. Activity of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Alone and in Combination with Ertapenem, Fosfomycin, and Tigecycline Against Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb Drug Resist. 2019, 25, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Liao, W.; Fang, R.; Chen, L.; Zhou, T. In vitro activity of imipenem-relebactam alone and in combination with fosfomycin against carbapenem-resistant gram-negative pathogens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2022, 103, 115712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, A.; Curtolo, A.; Volpicelli, L.; Cogliati Dezza, F.; De Angelis, M.; Cairoli, S.; Dell'Utri, D.; Goffredo, BM.; Raponi, G.; Venditti, M. Synergistic Meropenem/Vaborbactam Plus Fosfomycin Treatment of KPC Producing K. pneumoniae Septic Thrombosis Unresponsive to Ceftazidime/Avibactam: From the Bench to the Bedside. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021, 10, 781.

- Fois, M.; De Vito, A.; Cherchi, F.; Ricci, E.; Pontolillo, M.; Falasca, K.; Corti, N.; Comelli, A.; Bandera, A.; Molteni, C.; Piconi, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Alone versus Ceftazidime-Avibactam Plus Fosfomycin for the Treatment of Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia and Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: A Multicentric Retrospective Study from the SUSANA Cohort. Antibiotics (Basel). 2024, 13, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, RK.; Nguyen, MH.; Hao, B.; Kline, EG.; Clancy, CJ. Colistin Does Not Potentiate Ceftazidime-Avibactam Killing of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae In Vitro or Suppress Emergence of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01018–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Zhou Q, Yang X, Bai Y, Cui J. Evaluation of ceftazidime/avibactam alone and in combination with amikacin, colistin and tigecycline against Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae by in vitro time-kill experiment. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0258426.

- Rogers, TM.; Kline, EG.; Griffith, MP.; Jones, CE.; Rubio, AM.; Squires, KM.; Shields, RK. Mutations in ompK36 differentially impact in vitro synergy of meropenem/vaborbactam and ceftazidime/avibactam in combination with other antibiotics against KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2023, 5, dlad113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).