Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

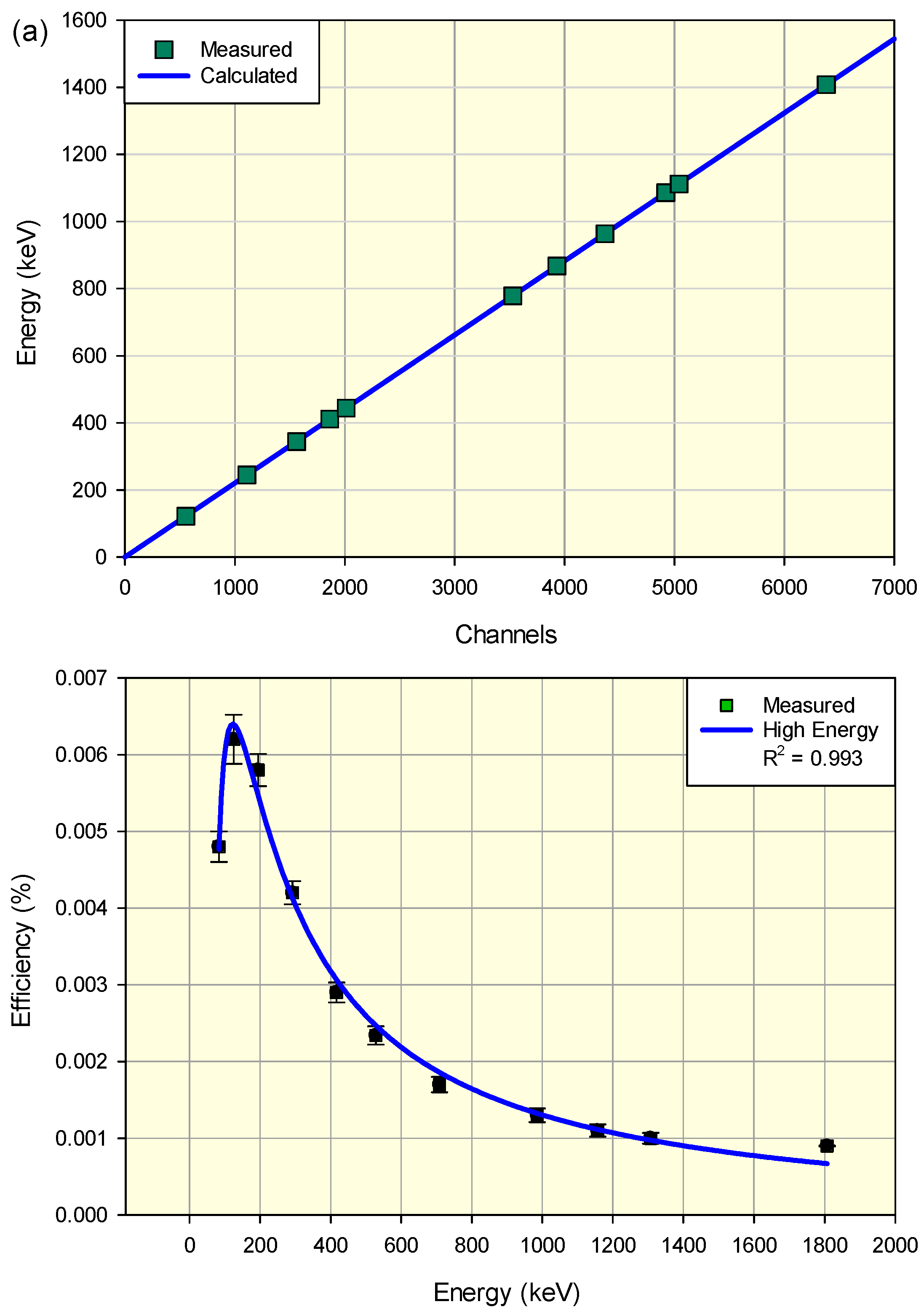

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Radioactivity Concentration of Radionuclides

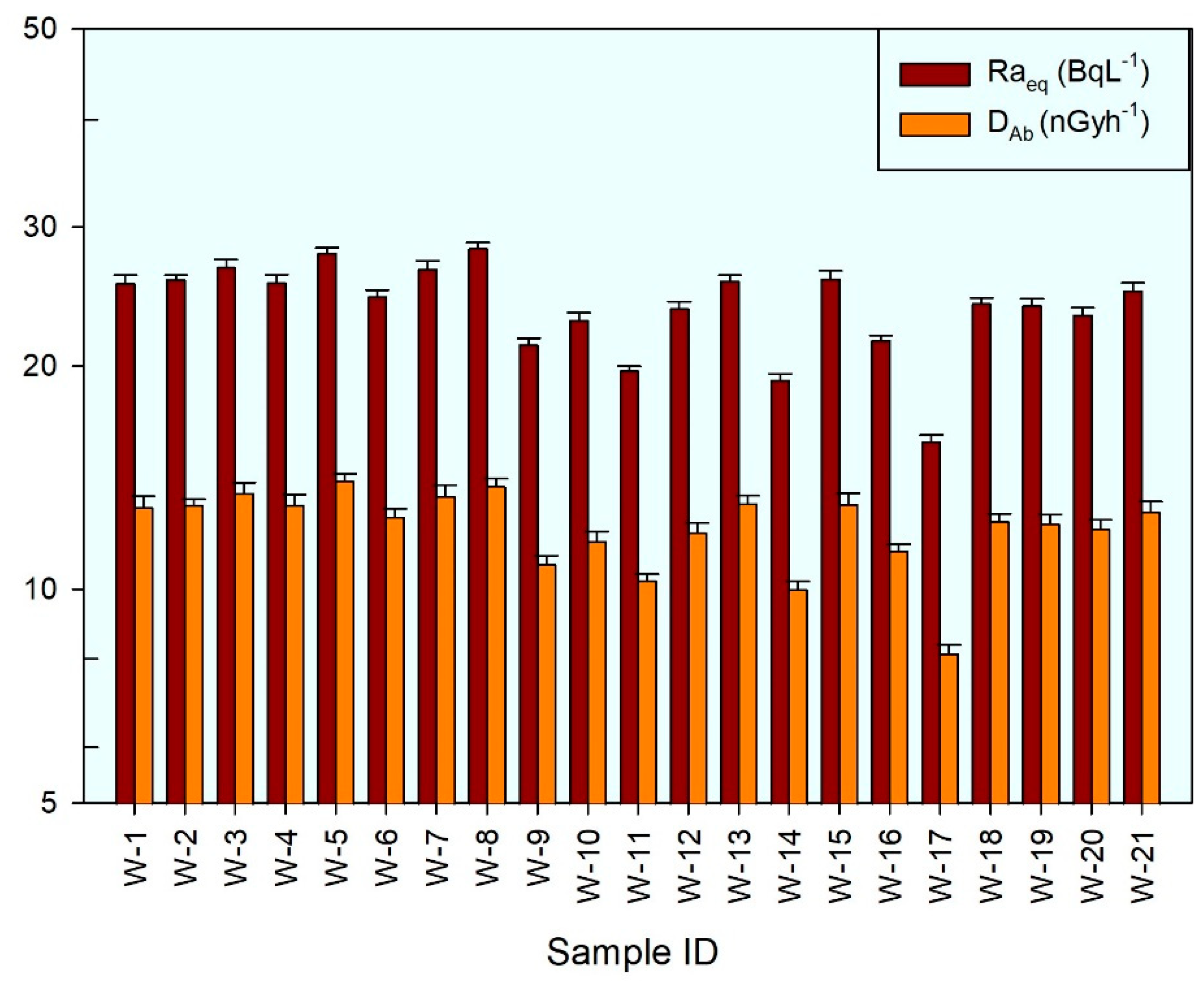

3.2. Radiun Equivalent and Absorbed Dose Rate

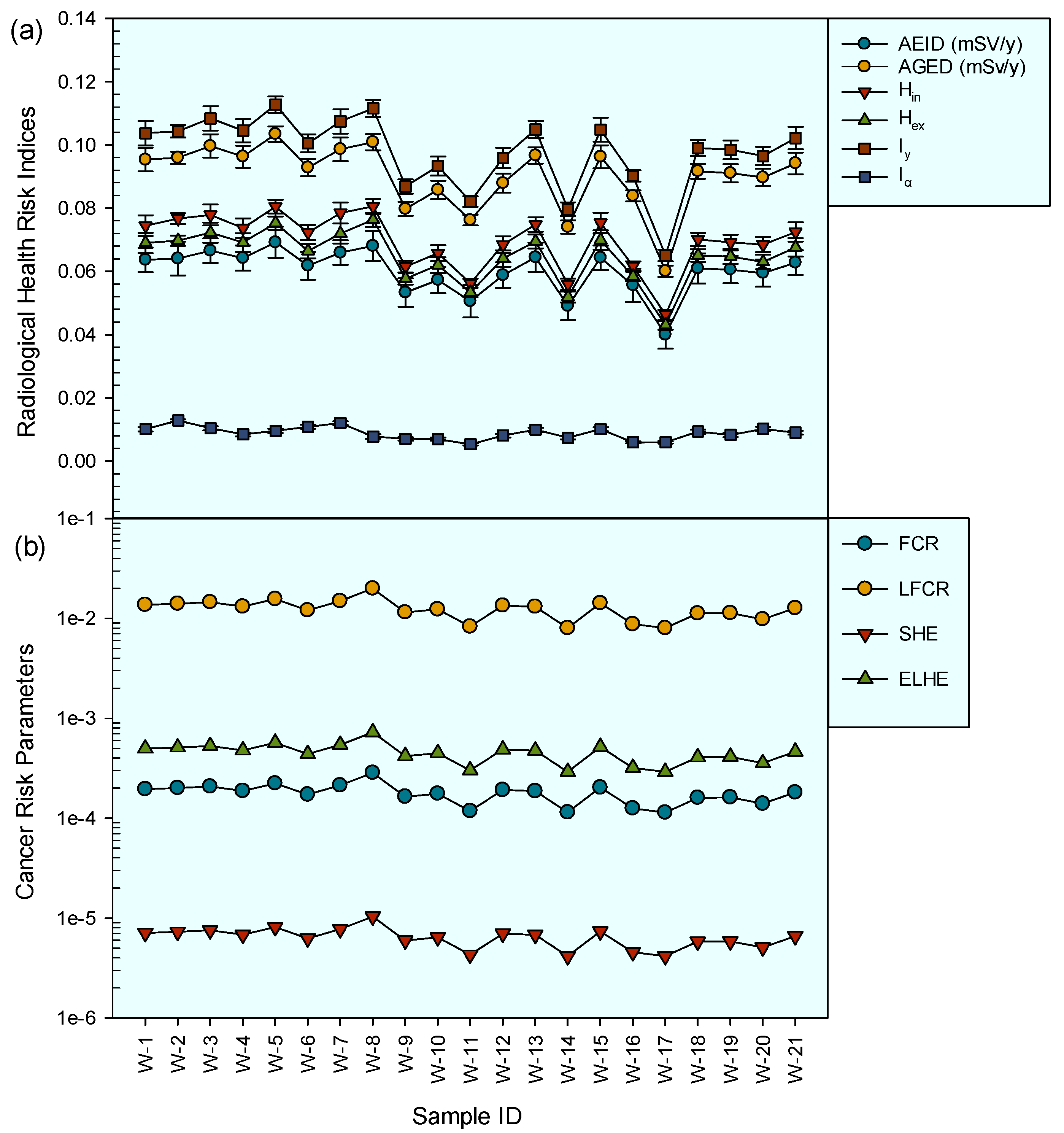

3.3. Annual Gonadal Equivalent Dose and Hazard Indices

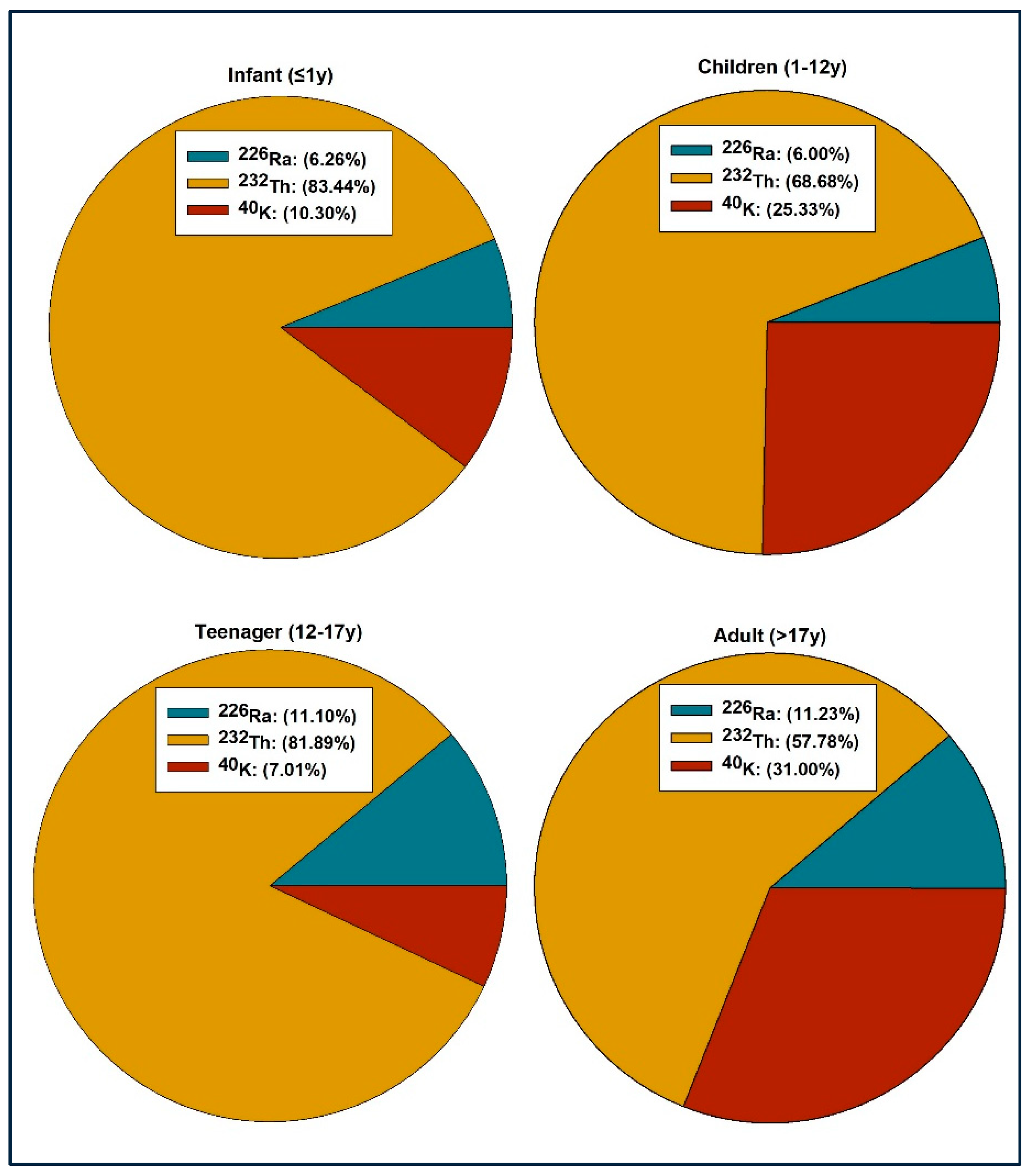

3.4. Cancer Risks and Hereditary Effects

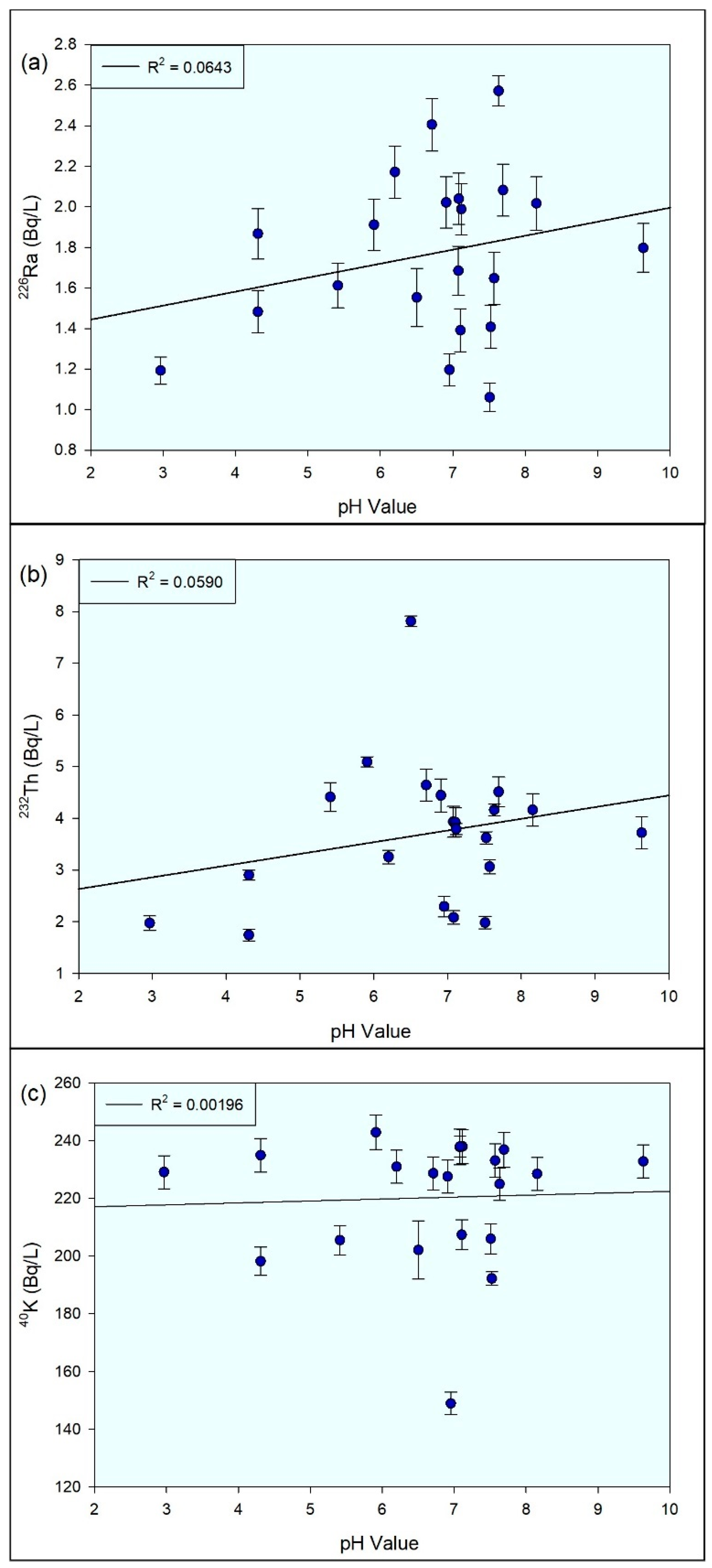

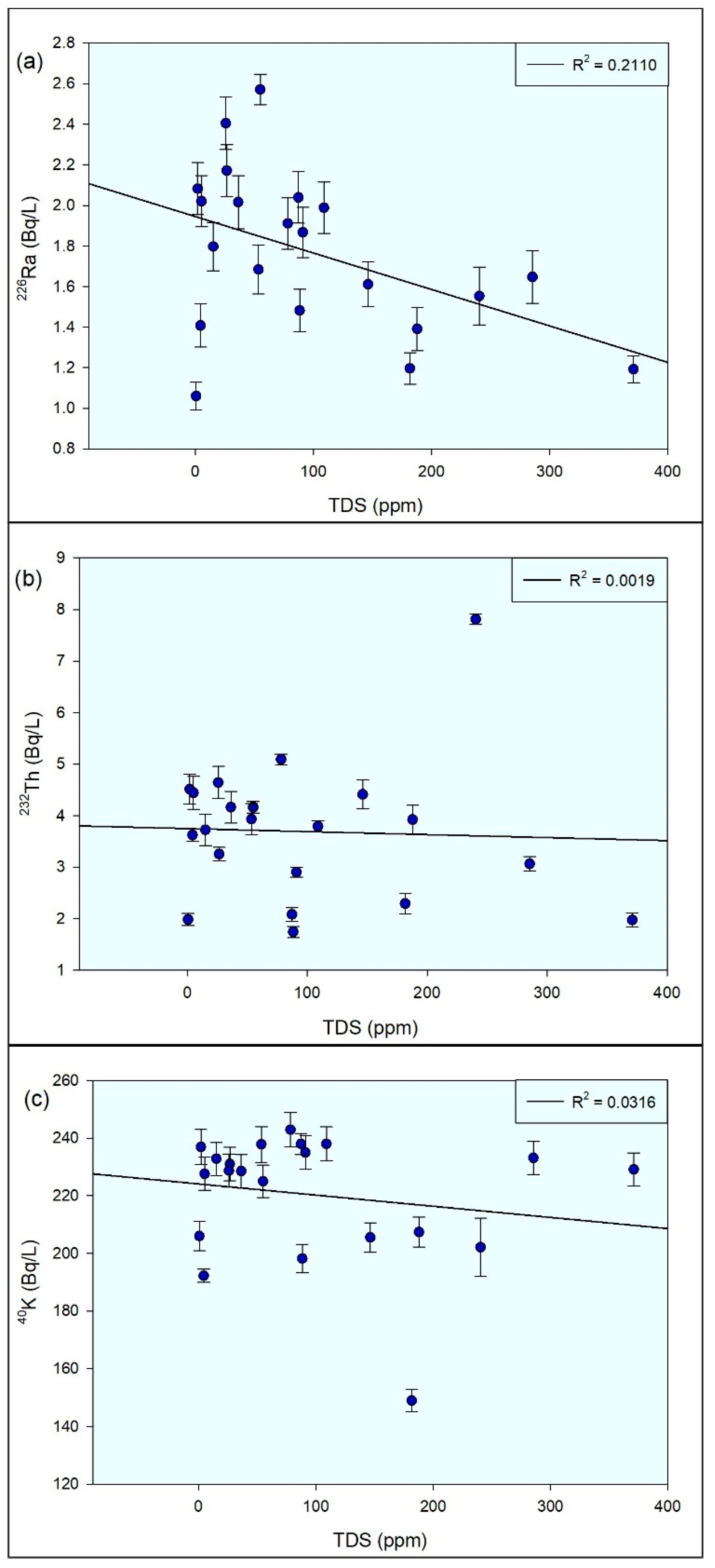

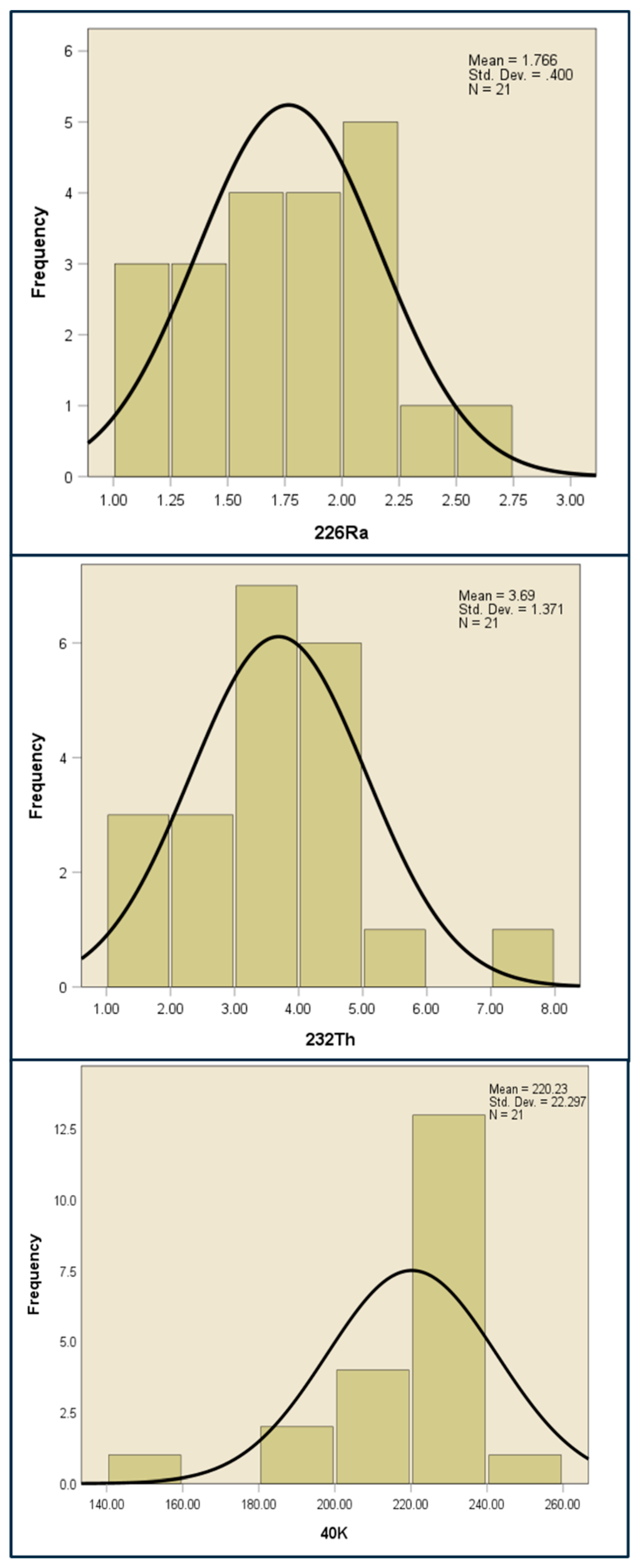

3.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohen A, Cui J, Song Q, Xia Q, Huang J, Yan X, Guo Y, Sun Y, Colford JM, Ray I: Bottled water quality and associated health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 years of published data from China. Environmental Research Letters 2022, 17(1). [CrossRef]

- DWAF: South African Water Quality Guidelines Volume 1 Domestic Use. In., vol. 1, 2nd edn. Pretoria: Department of Water Affairs and Forestry; 1996.

- John SOO, Akpa TC, Onoja RA: Gross alpha and gross beta radioactivity measurements in groundwater from Nasarawa North district Nasarawa state Nigeria. Radiation Protection and Environment 2021, 44(1):3-11. [CrossRef]

- Kekes T, Tzia C, Kolliopoulos G: Drinking and natural mineral water: Treatment and quality–safety assurance. Water 2023, 15(13):2325. [CrossRef]

- Aslani, H.; Pashmtab, P.; Shaghaghi, A.; Mohammadpoorasl, A.; Taghipour, H.; Zarei, M. Tendencies towards bottled drinking water consumption: Challenges ahead of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) waste management. Health Promotion Perspectives 2021, 11, 60. [CrossRef]

- John, S.O.O.; Olukotun, S.F.; Kupi, T.G.; Mathuthu, M. Health risk assessment of heavy metals and physicochemical parameters in natural mineral bottled drinking water using ICP-MS in South Africa. Applied Water Science 2024, 14, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Younos, T. Bottled water: global impacts and potential. Potable Water: Emerging Global Problems and Solutions 2014, 213-227.

- Nuccetelli, C.; Rusconi, R.; Forte, M. Radioactivity in drinking water: regulations, monitoring results and radiation protection issues. Annali dell'Istituto superiore di sanità 2012, 48, 362-373. [CrossRef]

- Rožmarić, M.; Rogić, M.; Benedik, L.; Štrok, M. Natural radionuclides in bottled drinking waters produced in Croatia and their contribution to radiation dose. Science of the total environment 2012, 437, 53-60. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines for drinking-water quality, Fourth edition incorporating the first and second addenda. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. ed.; World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva.: 2022.

- John, S.O. Isotopic profiling of natural uranium mined from northern Nigeria for nuclear forensic application. South African Journal of Science 2022, 118, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Agbalagba, E.; Avwiri, G.; Ononugbo, C. Activity concentration and radiological impact assessment of 226Ra, 228Ra and 40K in drinking waters from (OML) 30, 58 and 61 oil fields and host communities in Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Journal of environmental radioactivity 2013, 116, 197-200. [CrossRef]

- IAEA. Measurement of Radionuclides in Food and the Environment. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency 1989.

- Bazza, A.; Rhiyourhi, M.; Marhou, A.; Hamal, M. Assessment of natural radioactivity in Moroccan bottled drinking waters using gamma spectrometry. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2023, 195, 1307. [CrossRef]

- Fatima, I.; Zaidi, J.; Arif, M.; Tahir, S. Measurement of natural radioactivity in bottled drinking water in Pakistan and consequent dose estimates. Radiation Protection Dosimetry 2007, 123, 234-240.

- Janković, M.M.; Todorović, D.J.; Todorović, N.A.; Nikolov, J. Natural radionuclides in drinking waters in Serbia. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2012, 70, 2703-2710. [CrossRef]

- John, S.O.O.; Usman, I.T.; Akpa, T.C.; Abubakar, S.A.; Ekong, G.B. Natural radionuclides in rock and radiation exposure index from uranium mine sites in parts of Northern Nigeria. Radiation Protection and Environment 2020, 43, 36-43. [CrossRef]

- Kamunda, C.; Mathuthu, M.; Madhuku, M. An assessment of radiological hazards from gold mine tailings in the province of Gauteng in South Africa. International Journal of environmental research and public health 2016, 13, 138. [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M. Radium equivalent activity in the light of UNSCEAR report. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2012, 184, 5663-5667. [CrossRef]

- UNSCEAR. Sources and effects of Ionizing Radiation. United Nations, New York 2000, I, 453-487.

- Jameel, A.N. Radioactivity Levels Determination and Radiological Hazards in the Drink and Well Water Samples in Baghdad. Al-Nahrain Journal of Science 2023, 26, 67-72. [CrossRef]

- ICRP. Compendium of Dose Coefficients based on ICRP Publication 60; In: ICRP publication. vol. 119, ICRP Publication 119. Ann. ICRP 41(Suppl.) edn:; International Commission on Radiological Protection: 2012.

- Agbalagba, E.O.; Agbalagba, H.O.; Avwiri, G.O. Cost-benefit analysis approach to risk assessment of natural radioactivity in powdered and liquid milk products consumed in Nigeria. Environmental forensics 2016, 17, 191-202. [CrossRef]

- El-Gamal, H.; Sidique, E.; El-Haddad, M.; Farid, M.E.-A. Assessment of the natural radioactivity and radiological hazards in granites of Mueilha area (South Eastern Desert, Egypt). Environmental earth sciences 2018, 77, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Guidelines for Water Reuse; U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Wastewater Management, Office of Water.: Washington, D.C., 2012.

- Ononugbo, C.; Nwaka, B. Natural radioactivity and radiological risk estimation of drinking water from Okposi and Uburu salt lake area, Ebonyi state, Nigeria. Physical Science International Journal 2017, 15, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- ICRP. Age-dependent doses to members of the public from intake of radionuclides. Part 5 compilation of ingestion and inhalation coefficients.; In., vol. 26, Publication 72 edn. International Commission on Radiological Protection: 1996.

- El Arabi, A.; Ahmed, N.; Salahel Din, K. Natural radionuclides and dose estimation in natural water resources from Elba protective area, Egypt. Radiation protection dosimetry 2006, 121, 284-292. [CrossRef]

- Kitto, M.E.; Kim, M.S. Naturally occurring radionuclides in community water supplies of New York State. Health Physics 2005, 88, 253-260.

- Soto, J.; Quindos, L.; Diaz-Caneja, N.; Gutierrez, I.; Fernández, P. 226Ra and 222Rn in natural waters in two typical locations in Spain. Radiation Protection Dosimetry 1988, 24, 109-111.

- M. Isam Salih, M.; BL Pettersson, H.; Lund, E. Uranium and thorium series radionuclides in drinking water from drilled bedrock wells: correlation to geology and bedrock radioactivity and dose estimation. Radiation protection dosimetry 2002, 102, 249-258.

- WHO. Guidelines for drinking-water quality. WHO chronicle 2011, 38, 104-108.

- Lin, C.-C.; Chu, T.-C.; Huang, Y.-F. Variations of U/Th-series nuclides with associated chemical factors in the hot spring area of northern Taiwan. Journal of radioanalytical and nuclear chemistry 2003, 258, 281-286.

| Radionuclide | Infant (≤1y) | Children (1-12y) | Teenager (12-17y) | Adult (>17y) |

| 226Ra | 4.2E-06 | 6.2E-07 | 1.5E-06 | 2.8E-07 |

| 232Th | 3.0E-05 | 3.4E-06 | 5.3E-06 | 6.9E-07 |

| 40K | 6.2E-08 | 2.1E-08 | 7.6E-09 | 6.2E-07 |

| Water intake (Lyear-1) | 182.625 | 365.250 | 730.500 | 730.500 |

| Sample ID | Activity Concentration of Radionuclide (BqL-1) | Total Annual Effective Ingestion Doses (TAEID) (mSvy-1) | |||||

| 226Ra | 232Th | 40K |

Infants (≤ 1 year) (x10-2) |

Children (1-12 years) (x10-3) |

Teenagers (12-17 years) (x10-2) |

Adults (> 17 years) (x10-3) |

|

| W-1 | 2.016 ± 0.131 | 4.164 ± 0.308 | 228.500 ± 57.100 | 2.713 | 7.380 | 1.960 | 3.546 |

| W-2 | 2.571 ± 0.075 | 4.156 ± 0.108 | 225.000 ± 56.700 | 2.752 | 7.469 | 2.016 | 3.639 |

| W-3 | 2.082 ± 0.128 | 4.506 ± 0.293 | 236.900 ± 60.930 | 2.916 | 7.884 | 2.104 | 3.770 |

| W-4 | 1.684 ± 0.121 | 3.931 ± 0.303 | 237.800 ± 61.800 | 2.567 | 7.087 | 1.838 | 3.403 |

| W-5 | 1.911 ± 0.126 | 5.090 ± 0.097 | 242.900 ± 59.700 | 3.228 | 8.617 | 2.315 | 4.057 |

| W-6 | 2.171 ± 0.128 | 3.253 ± 0.125 | 231.000 ± 57.690 | 2.230 | 6.303 | 1.626 | 3.129 |

| W-7 | 2.405 ± 0.129 | 4.644 ± 0.305 | 228.700 ± 56.700 | 3.010 | 8.066 | 2.188 | 3.869 |

| W-8 | 1.553 ± 0.143 | 7.807 ± 0.099 | 202.100 ± 10.120 | 4.639 | 11.597 | 3.305 | 5.168 |

| W-9 | 1.408 ± 0.106 | 3.615 ± 0.117 | 192.200 ± 23.020 | 2.319 | 6.282 | 1.661 | 2.981 |

| W-10 | 1.391 ± 0.106 | 3.915 ± 0.276 | 207.400 ± 51.530 | 2.499 | 6.768 | 1.783 | 3.197 |

| W-11 | 1.060 ± 0.069 | 1.982 ± 0.124 | 206.000 ± 51.890 | 1.410 | 4.281 | 0.998 | 2.149 |

| W-12 | 1.611 ± 0.110 | 4.412 ± 0.280 | 205.500 ± 51.240 | 2.788 | 7.420 | 1.999 | 3.484 |

| W-13 | 1.988 ± 0.126 | 3.787 ± 0.111 | 238.000 ± 58.870 | 2.515 | 6.979 | 1.816 | 3.393 |

| W-14 | 1.482 ± 0.104 | 1.736 ± 0.112 | 198.200 ± 49.250 | 1.303 | 4.012 | 0.945 | 2.076 |

| W-15 | 2.021 ± 0.126 | 4.440 ± 0.321 | 227.600 ± 56.920 | 2.863 | 7.717 | 2.067 | 3.682 |

| W-16 | 1.192 ± 0.067 | 1.973 ± 0.135 | 229.100 ± 57.160 | 1.443 | 4.477 | 1.022 | 2.276 |

| W-17 | 1.196 ± 0.078 | 2.290 ± 0.199 | 149.000 ± 38.480 | 1.526 | 4.258 | 1.100 | 2.074 |

| W-18 | 1.867 ± 0.124 | 2.899 ± 0.100 | 235.000 ± 58.360 | 2.015 | 5.825 | 1.457 | 2.907 |

| W-19 | 1.647 ± 0.129 | 3.059 ± 0.138 | 233.100 ± 57.870 | 2.081 | 5.959 | 1.494 | 2.934 |

| W-20 | 2.039 ± 0.127 | 2.078 ± 0.134 | 238.000 ± 36.730 | 1.583 | 4.868 | 1.160 | 2.542 |

| W-21 | 1.797 ± 0.120 | 3.721 ± 0.313 | 232.800 ± 57.490 | 2.456 | 6.813 | 1.767 | 3.297 |

| Range | 1.060 - 2.571 | 1.736 - 7.807 | 149.000 - 242.900 | 1.303 - 4.639 | 4.012 - 11.597 | 0.945 - 3.305 | 2.074 - 5.168 |

| Mean | 1.766± 0.399 | 3.688 ± 1.371 | 220.229 ± 22.297 | 2.422 ± 0.768 | 6.669 ± 1.771 | 1.745 ± 0.549 | 3.218 ± 0.749 |

| DWAF, 1996 | 0 – 0.42 | 0 - 0.228 | - | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Worldwide | 35 | 30 | 400 | 0.2-1 | 0.2-1 | 0.2-1 | 0.1-1 |

| Parameter | No | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Stdev | Range | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| 226Ra | 21 | 1.060 ±0.067 | 2.571 ± 0.143 | 1.766 | 0.398 | 1.511 | 0.1598 | 0.07099 | -0.47215 |

| 232Th | 21 | 1.736 ± 0.097 | 7.807 ± 0.321 | 3.688 | 1.371 | 6.071 | 1.879 | 1.069 | 2.922 |

| 40K | 21 | 149.0 ± 10.120 | 242.9 ± 50.931 | 220.229 | 22.297 | 93.9 | 497.161 | -1.816 | 4.029 |

| Raeq | 21 | 15.929 ± 0.268 | 28.252 ± 0.613 | 23.976 | 3.033 | 12.323 | 9.201 | -1.056 | 1.144 |

| TAEID Infants | 21 | 0.013 | 0.046 | 0.024 | 0.008 | 0.033 | 5.894E-05 | 0.874 | 2.243 |

| TAEID Children | 21 | 0.004 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 3.137E-06 | 0.698 | 1.726 |

| TAEID Teenagers | 21 | 0.009 | 0.033 | 0.017 | 0.005 | 0.024 | 3.017E-06 | 0.799 | 1.992 |

| TAEID Adults | 21 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 5.609E-07 | 0.430 | 1.012 |

| Parameter | 226Ra | 232Th | 40K | Raeq | TAEID Infant (≤1y) | TAEID Children (1-12y) | TAEID Teenager (12-17y) | TAEID Adult (>17) | FCR | LFCR | SHE | ELH |

| 226Ra | 1 | 0.331 | 0.598 | 0.684 | 0.389 | 0.428 | 0.414 | 0.496 | 0.496 | 0.496 | 0.496 | 0.496 |

| 232Th | 1 | 0.137 | 0.767 | 0.998 | 0.991 | 0.996 | 0.977 | 0.977 | 0.977 | 0.977 | 0.977 | |

| 40K | 1 | 0.733 | 0.194 | 0.259 | 0.203 | 0.327 | 0.327 | 0.327 | 0.327 | 0.327 | ||

| Raeq | 1 | 0.805 | 0.843 | 0.812 | 0.881 | 0.881 | 0.881 | 0.881 | 0.881 | |||

| TAEID Infant (≤1y) | 1 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.989 | 0.989 | 0.989 | 0.989 | 0.989 | ||||

| TAEID Children (1-12y) | 1 | 0.998 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | |||||

| TAEID Teenager (12-17y) | 1 | 0.991 | 0.991 | 0.991 | 0.991 | 0.991 | ||||||

| TAEID Adult (>17) | 1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||||

| FCR | 1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| LFCR | 1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| SHE | 1 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| ELH | 1 |

| Origin | 226Ra (BqL-1) | 232Th (BqL-1) | 40K (BqL-1) | TAEID (mSvy-1) | Reference |

| South Africa | 1.766 ± 0.399 | 3.688 ± 1.371 | 220.229 ± 22.297 | 0.01275 ± 0.004 | Present study |

| Iraq | 1.19 ± 0.5 | 0.96 ± 0.2 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 0.015 ± 0.0025 | [20] |

| Morocco | 0.00194 | 0.00246 | 0.2366 | 0.991E-03 | [12] |

| Egypt | 1.6-11.1 | 0.21-0.97 | 9.1-23.0 | 0.67 | [27] |

| USA | 0.052 | 0.052 | - | 0.027 | [28] |

| Croatia | 0.0422 ± 0.0032 | 0.0219 ± 0.0035 | - | 0.0016-0.0115(NSW); 0.0109-0.0183(MW) | [6] |

| Nigeria | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 28.5 ± 3.0 | 3.3 | [10] |

| Spain | 0.02-4.0 | - | - | 0.5 | [14,29] |

| Pakistan | 0.0113 ± 0.0023 | 0.0052 ± 0.0004 | 0.140 ± 0.0306 | 0.0041 | [13] |

| Sweden | 4.9 | 1.6 | - | 0.45 | [30] |

| Serbia | <0.070 | <0.050 | <0.250 | 0.0092 | [14] |

| Poland | 0.0008-0.437 | - | 0.157-10.064 | - | [14] |

| France | 0.007-0.70 | - | - | - | [14] |

| Germany | 0.00085-0.35 | - | [14] | ||

| Hungary | 0.0043-0.910 | - | - | - | [14] |

| Saudi Arabia | (0.105-0.568)E-03 | (0.016-0.382)E-03 | 18.84E-03 | - | [12] |

| Malaysia | (0.7-7.03)E-03 | (0.55-8.64)E-03 | (22-53)E-03 | - | [12] |

| SAWQG | 0 – 0.42 | 0 - 0.228 | - | 0.3 | [8] |

| Worldwide | 35 | 30 | 400 | 0.2-1 | [19] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).