Submitted:

09 December 2024

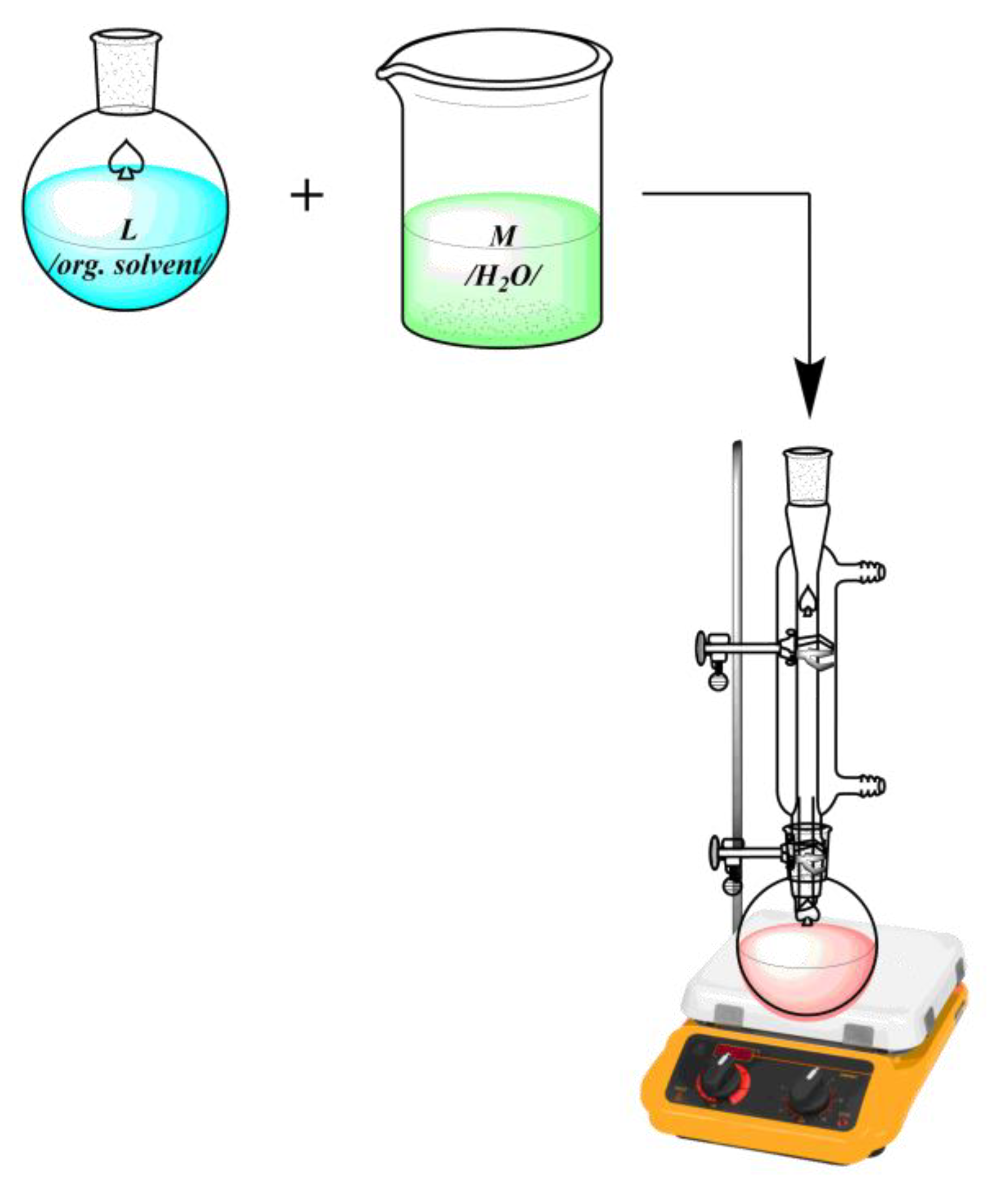

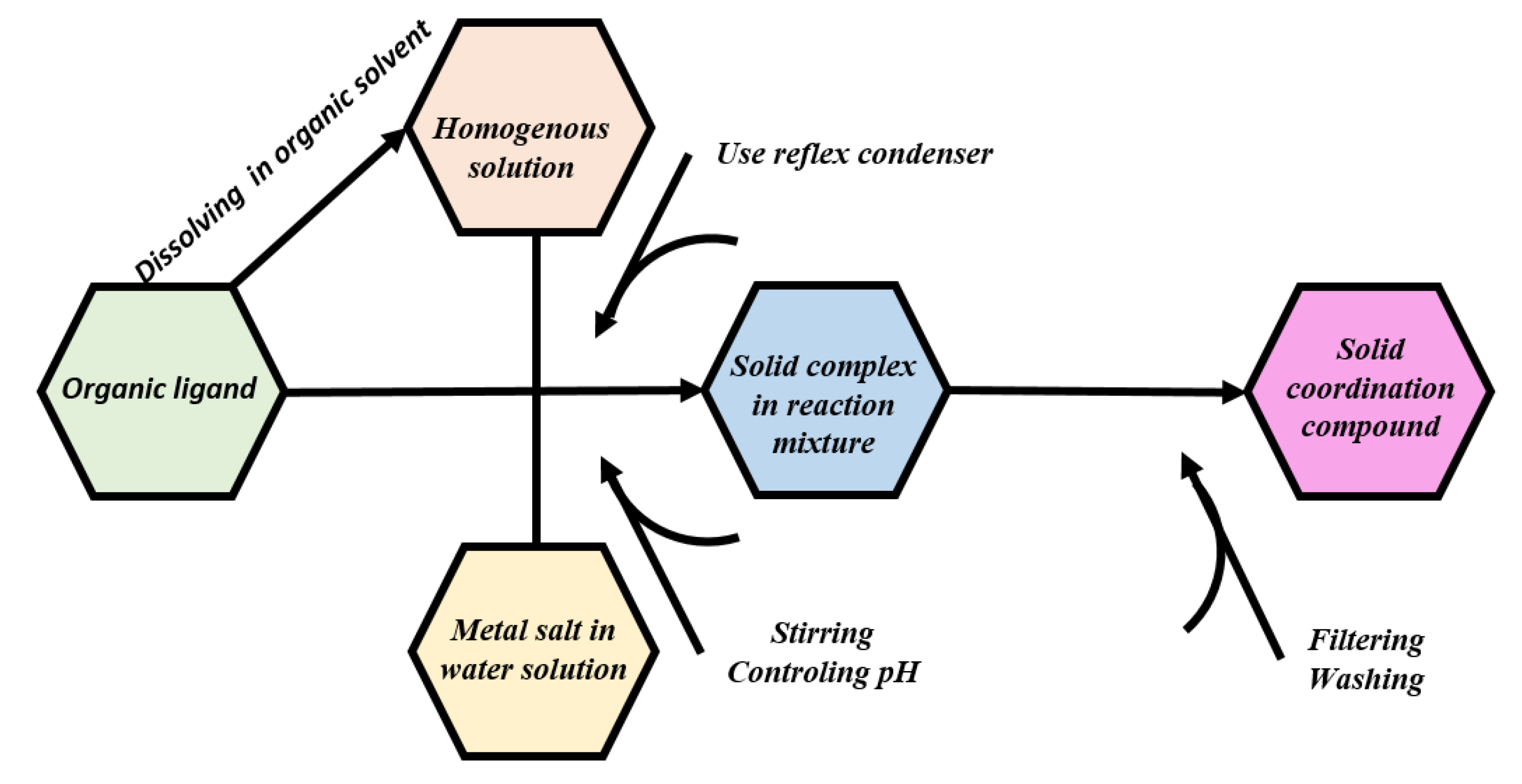

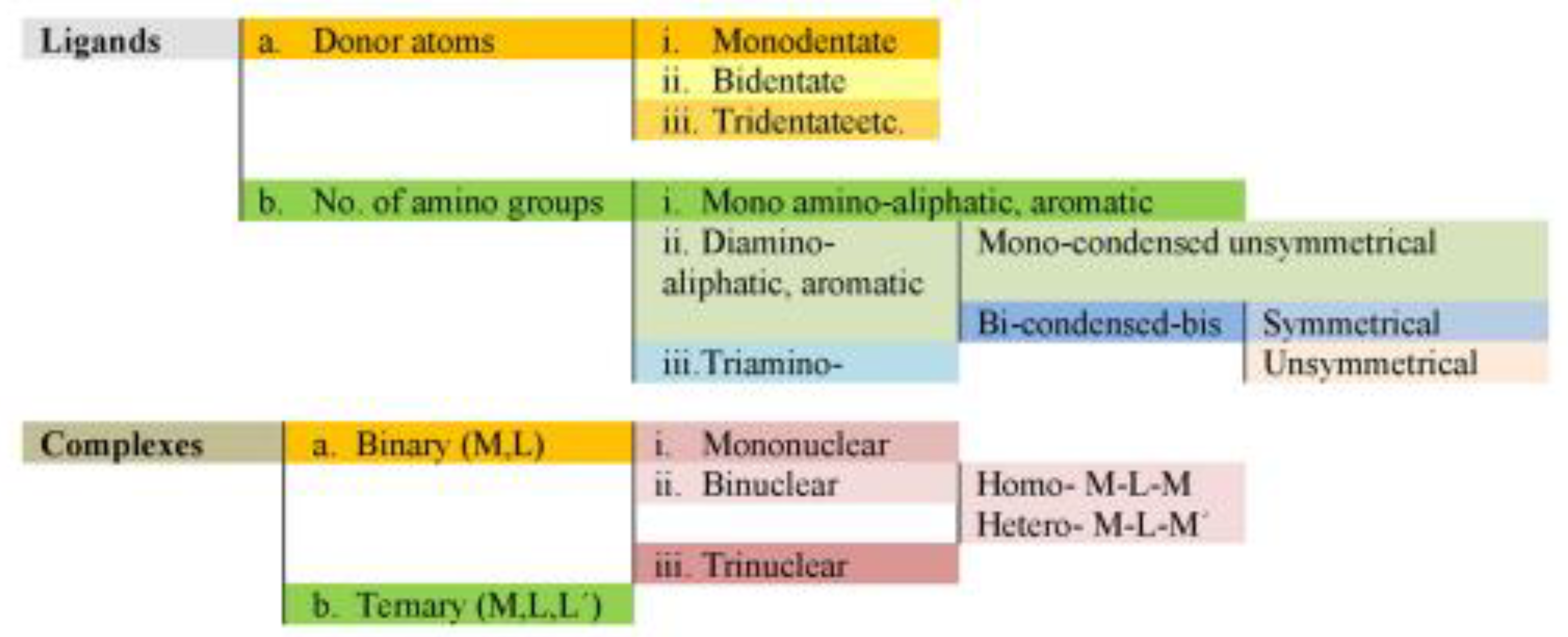

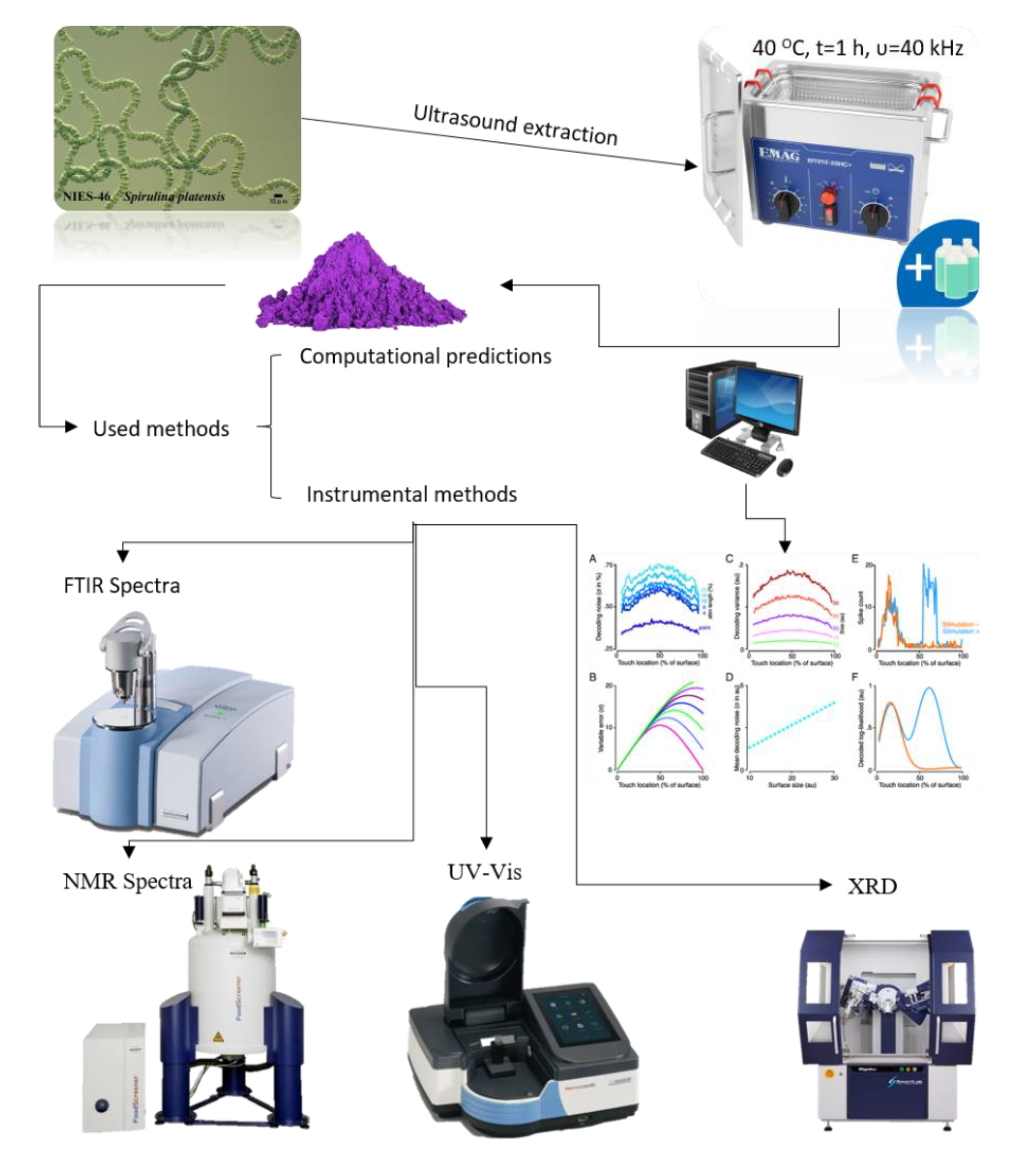

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Key Characteristics of Transition Metals and Their Complexes:

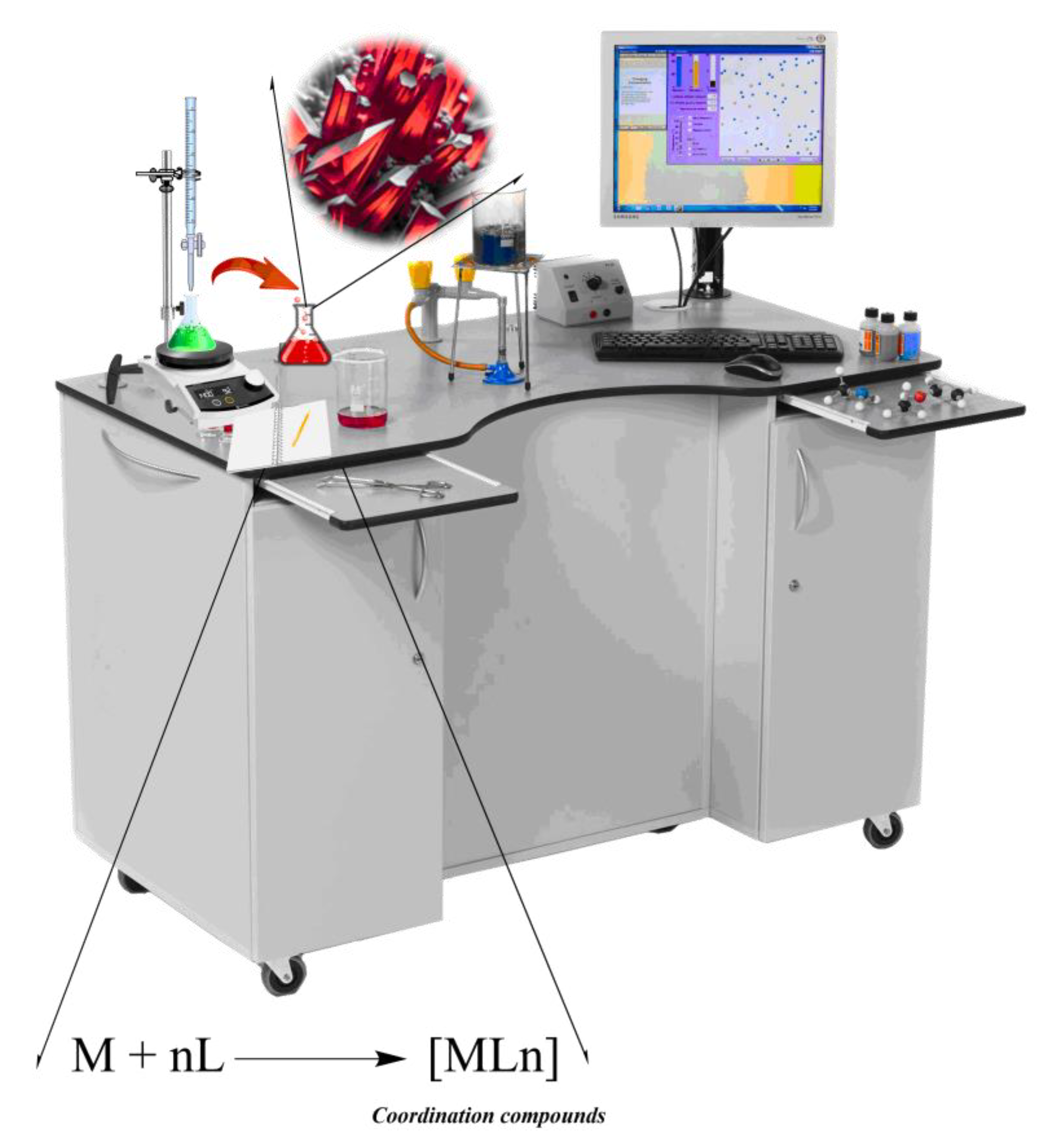

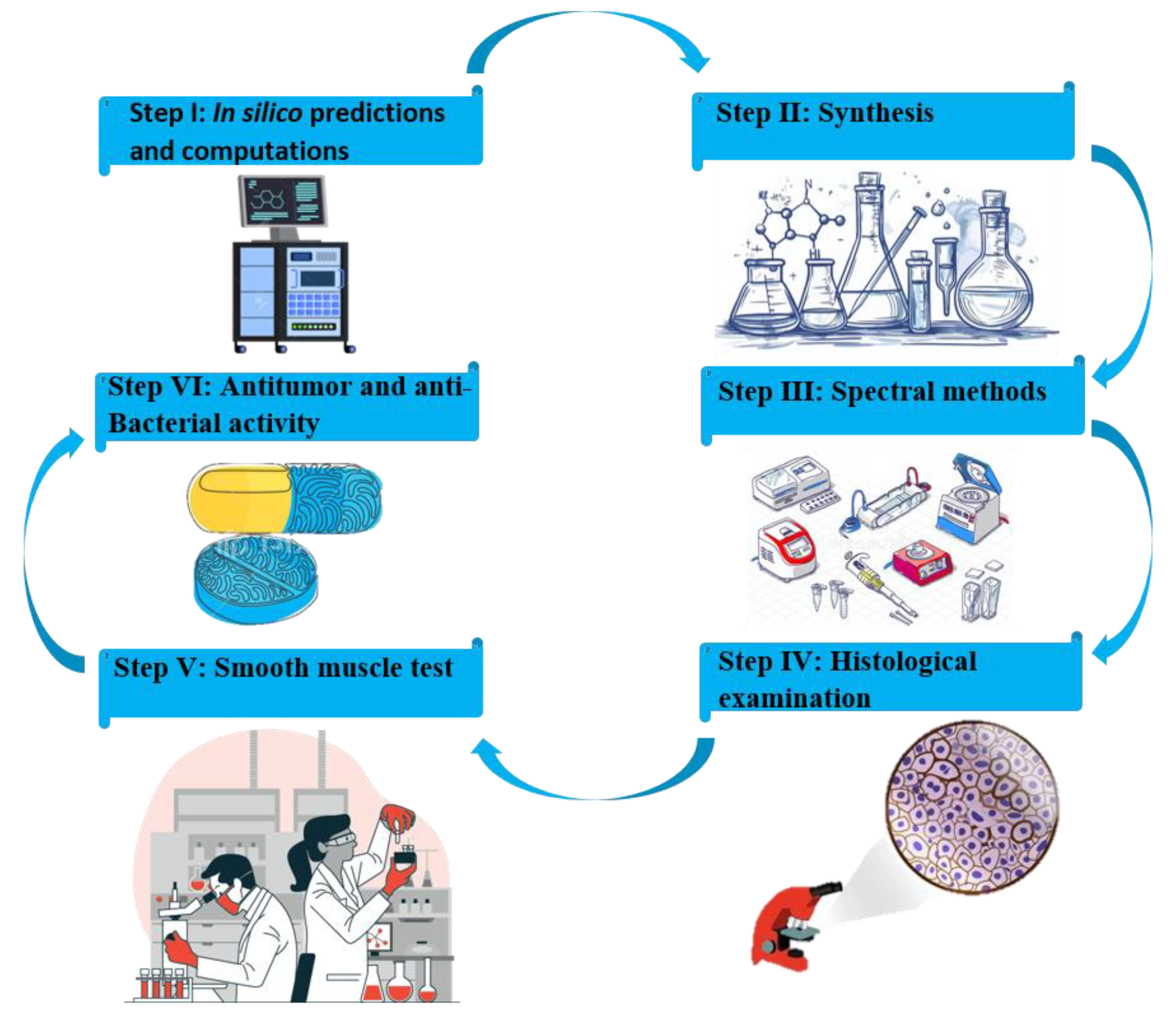

2. Methods for characterization of coordination compounds

3. Some Aspects of the Biological Significance of Coordination Compounds

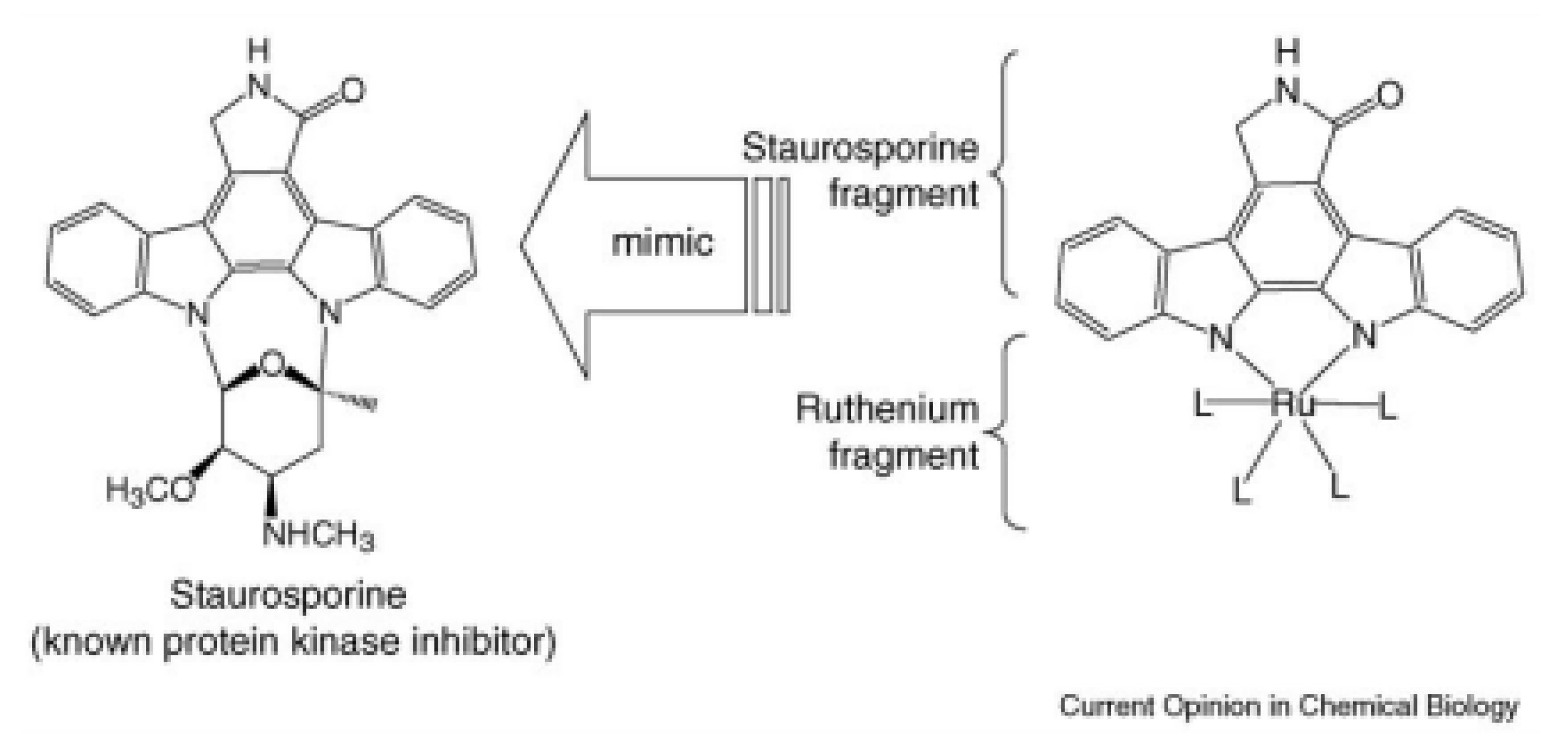

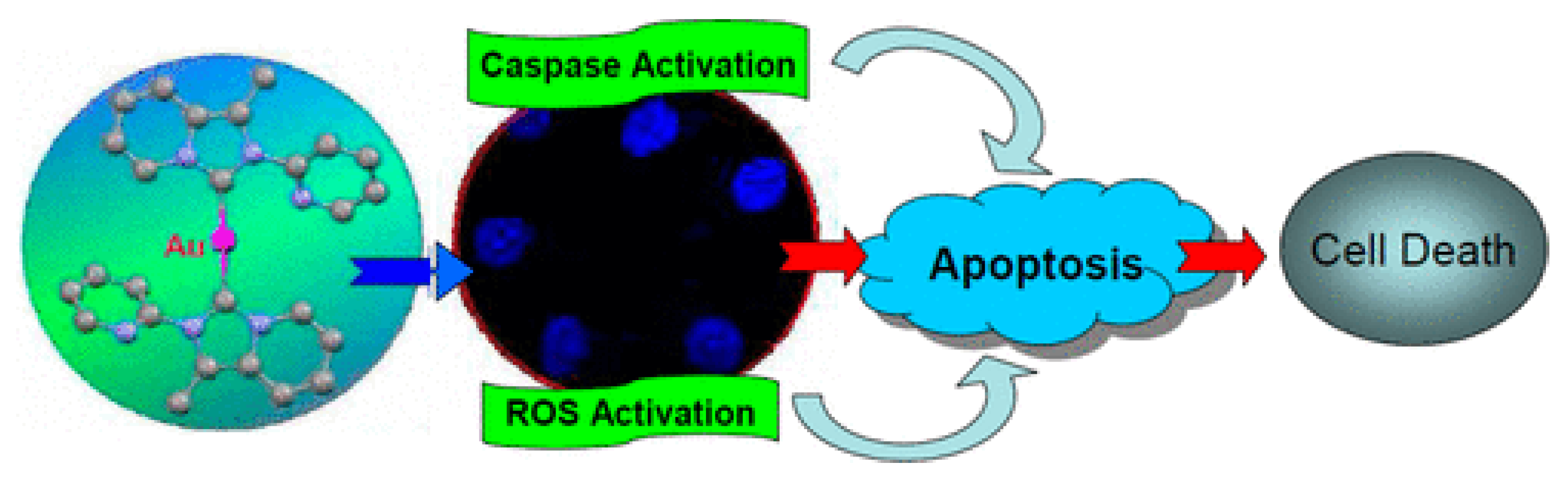

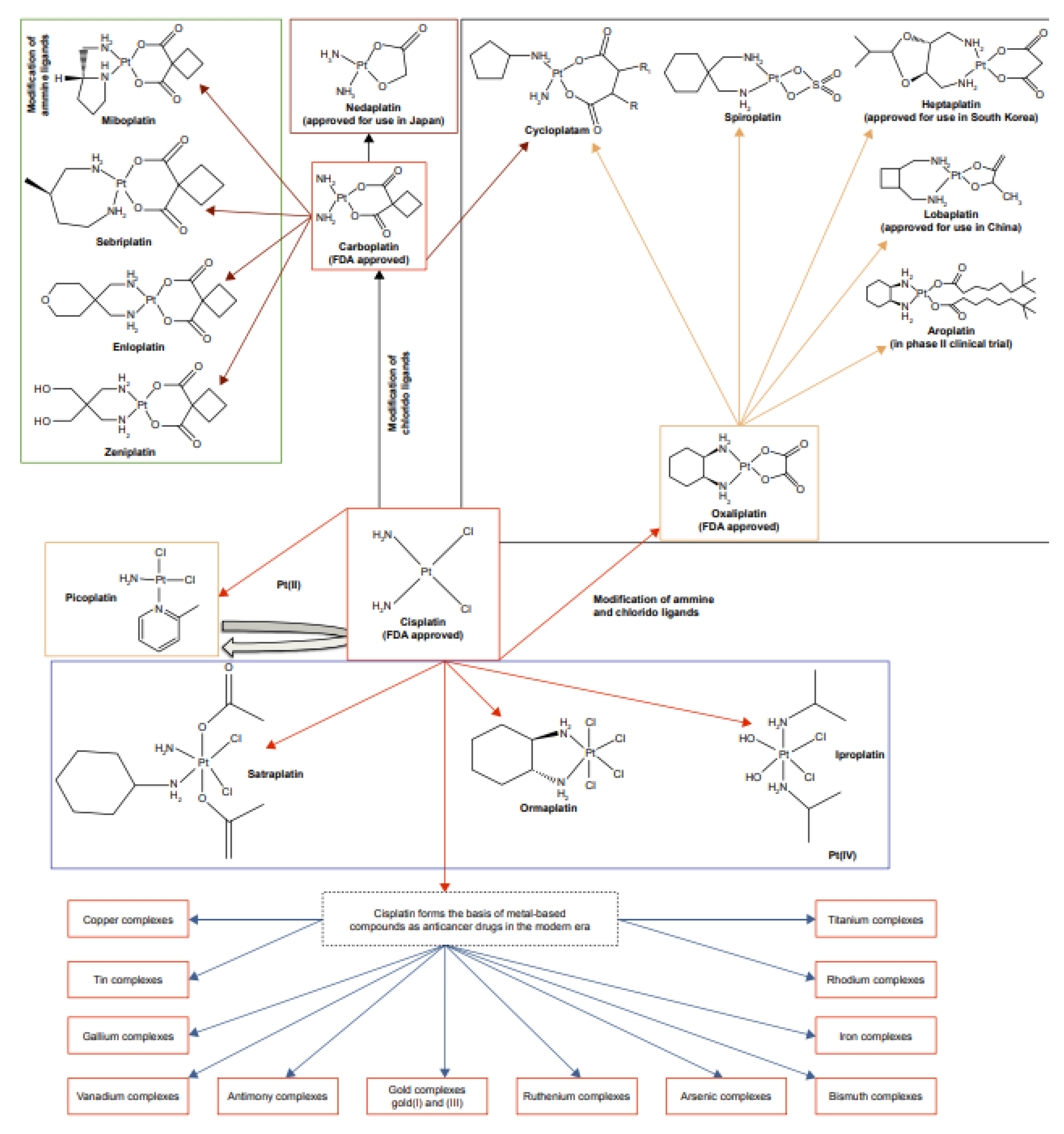

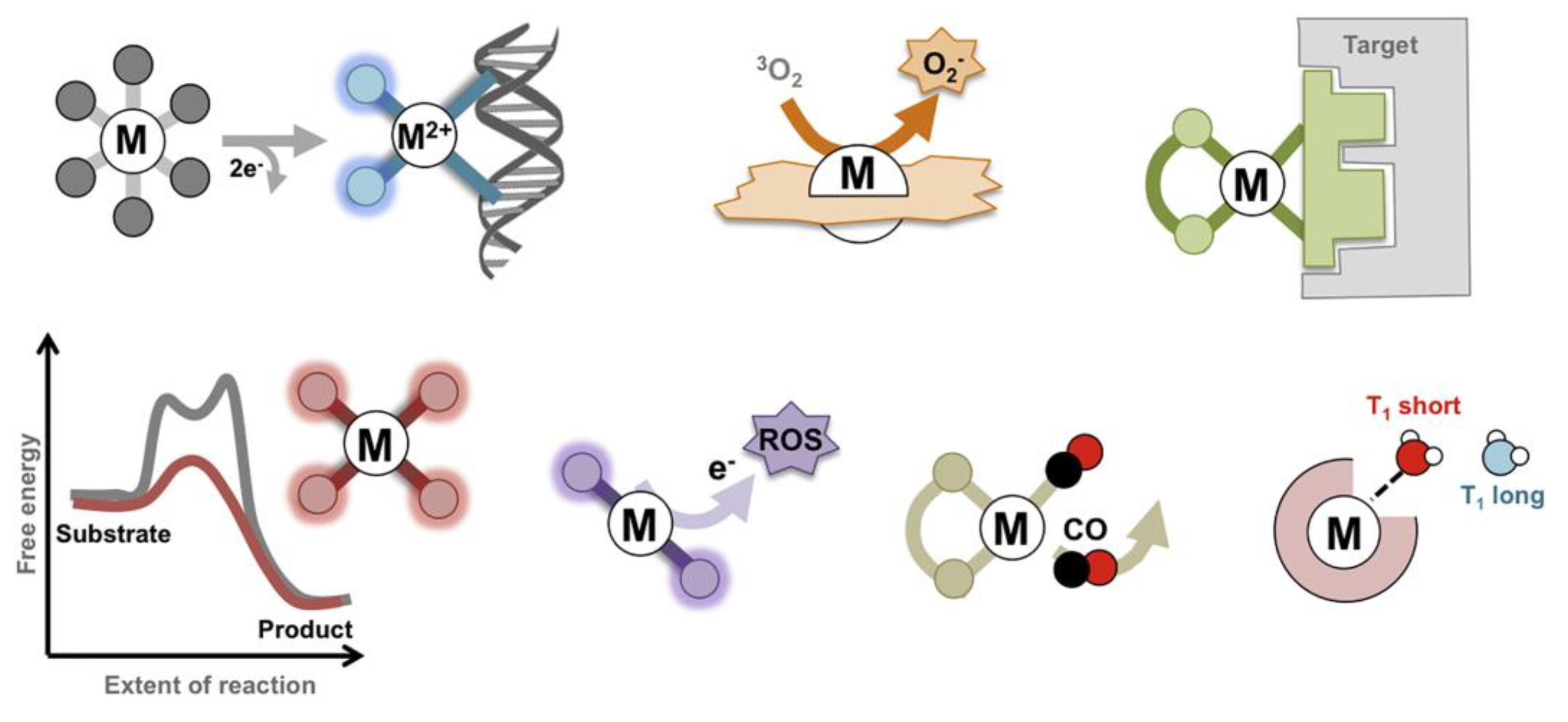

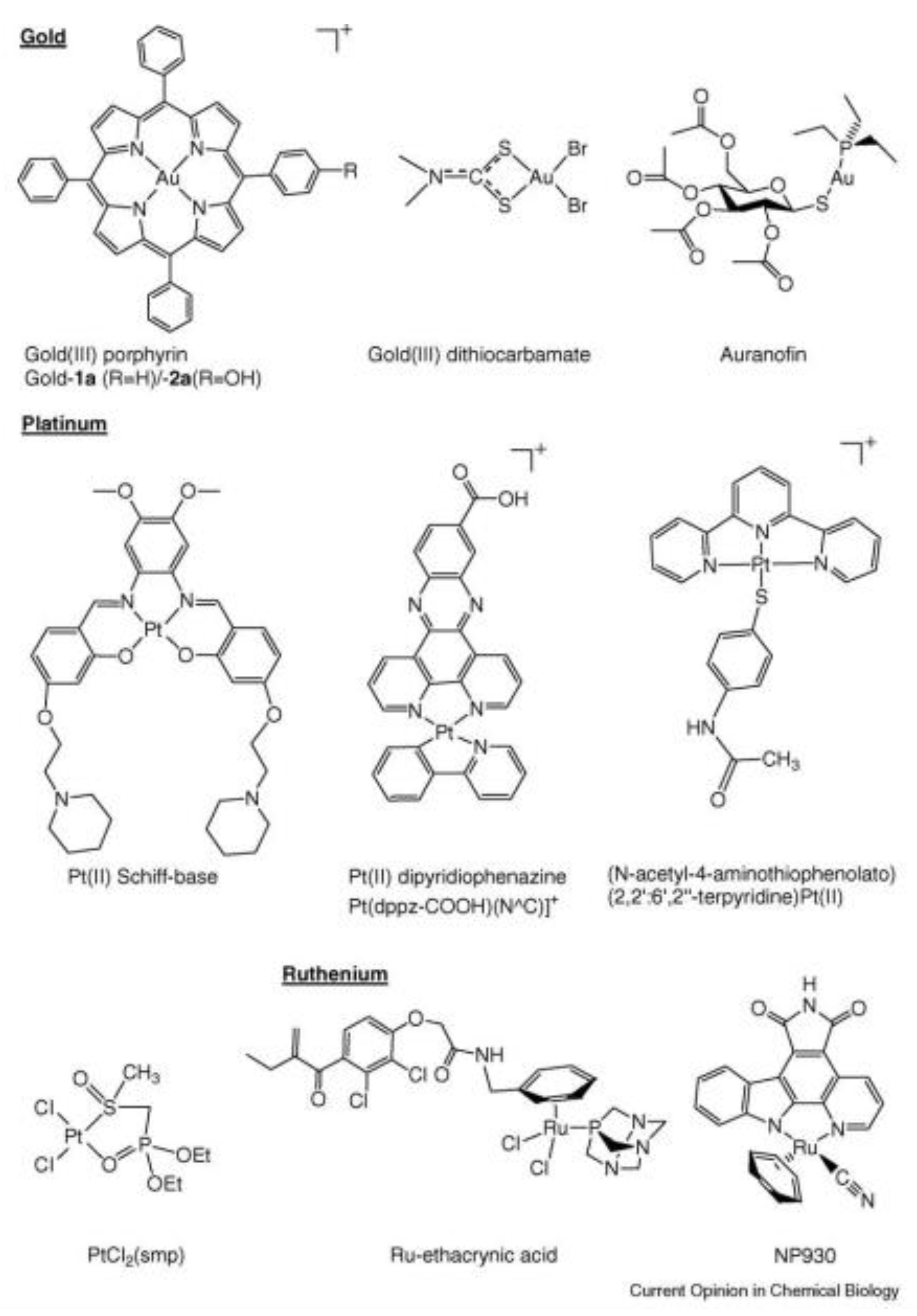

3.1. Anticancer Properties

- -

- Exhibit redox activity.

- -

- Form complexes targeting specific biomolecules.

- -

- Disrupt cellular mechanisms of proliferation.

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity (Antibacterial and Antifungal)

3.2. Antioxidant Activity

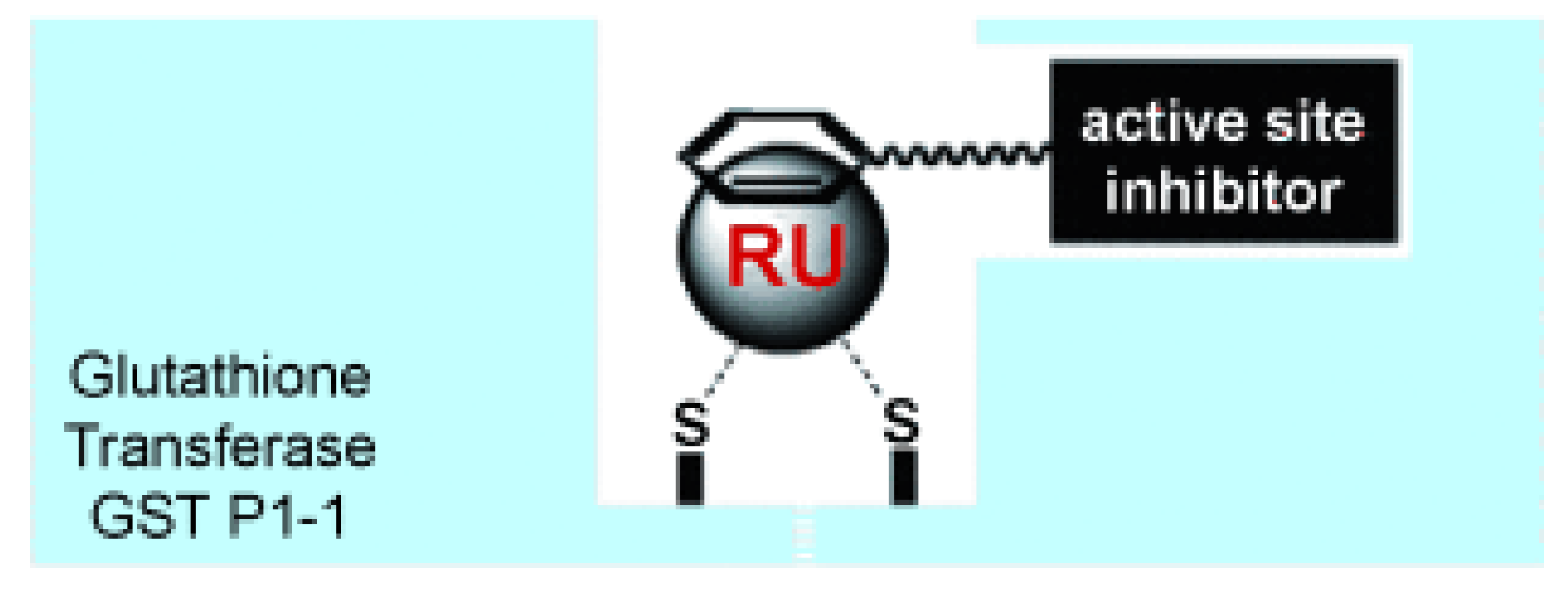

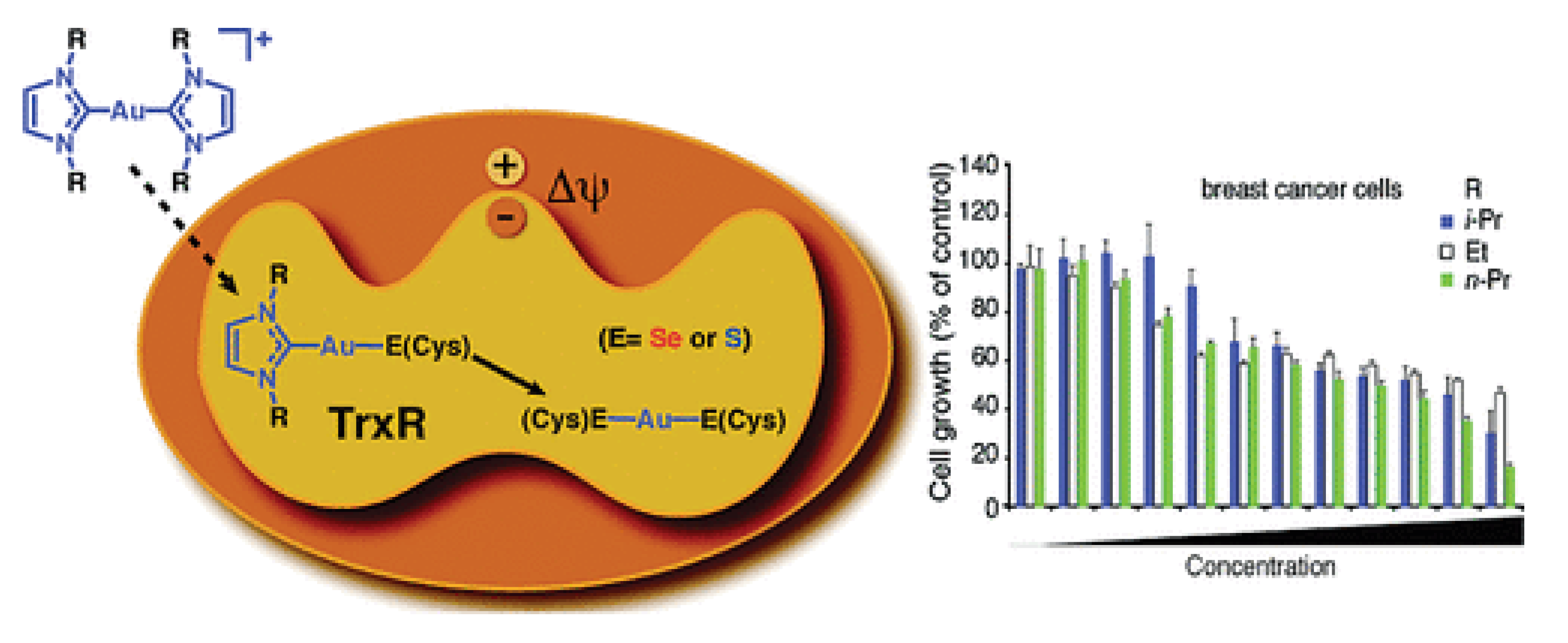

3.4. Enzyme-Inhibitory Activities

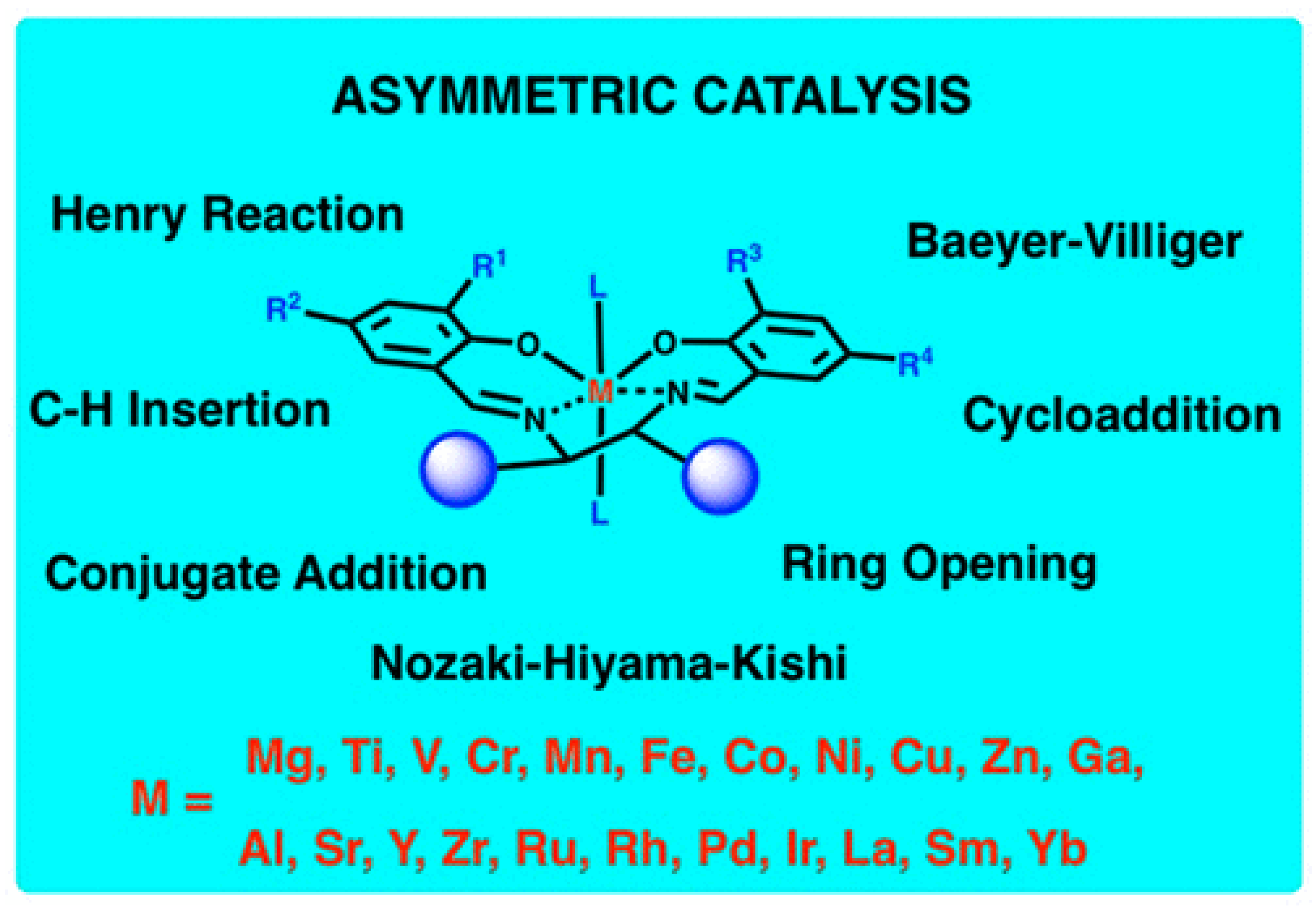

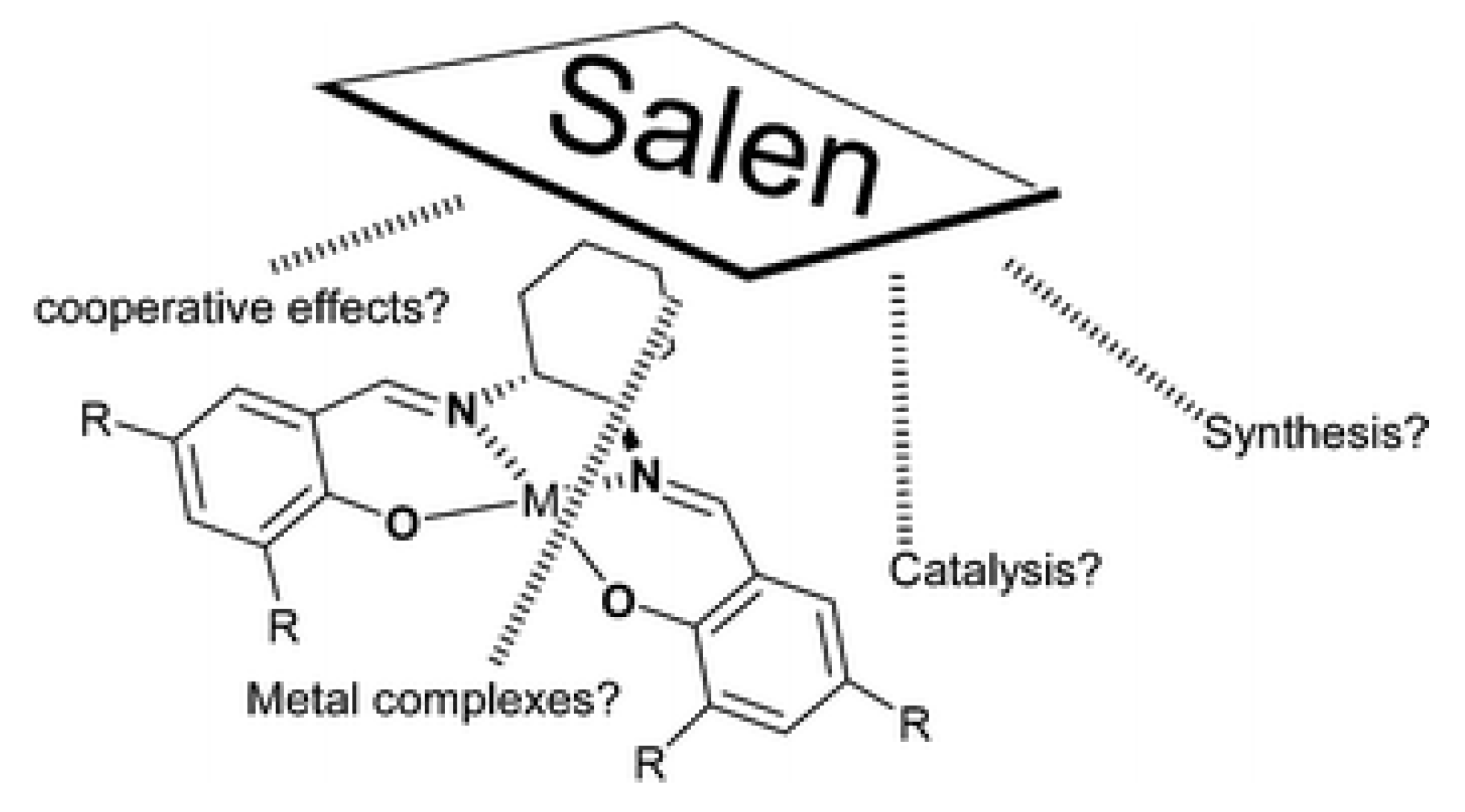

4. Schiff-Base Complexes as Catalysts

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmedova, A.; Marinova, P.; Paradowska, K.; Stoyanov, N.; Wawer, I.; Mitewa, M. Spectroscopic aspects of the coordination modes of 2,4-dithiohydantoins: Experimental and theoretical study on copper and nickel complexes of cyclohexanespiro-5-(2,4-dithiohydantoin), Inorg. Chim. Acta 2010, 363, 3919-3925. [CrossRef]

- Ahmedova, A.; Marinova, P.; Paradowska, K.; Marinov, M.; Wawer, I.; Mitewa, M. Structure of 2,4-dithiohydantoin complexes with copper and nickel – Solid-state NMR as verification method, Polyhedron 2010, 29, 1639-1645. [CrossRef]

- Ahmedova, A.; Pavlović, G.; Marinov, M.; Marinova, P.; Momekov, G.; Paradowska, K.; Yordanova, S.; Stoyanov, S.; Vassilev, N.; Stoyanov N. Synthesis and anticancer activity of Pt(II) complexes of spiro-5-substituted 2,4-dithiohydantoins”, Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 528, Article number 120605. [CrossRef]

- Ahmedova, A.; Marinova, P.; Paradowska, K.; Marinov, M.; Mitewa, M. Synthesis and characterization of Copper(II) and Ni(II) complexes of (9’-fluorene)-spiro-5-dithiohidantoin, J.Mol.Str. 2008, 892, 13-19. [CrossRef]

- Ahmedova, A.; Paradowska, K.; Wawer I. 1H, 13C MAS NMR and DFT GIAO study of quercetin and its complex with Al(III) in solid state, J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 110, 27-35. [CrossRef]

- Marinova, P.; Hristov,M.; Tsoneva, S.; Burdzhiev,N.; Blazheva, D.; Slavchev, A.; Varbanova, E.; Penchev, P. Synthesis, Characterization, and Antibacterial Studies of New Cu(II) and Pd(II) Complexes with 6-Methyl-2-Thiouracil and 6-Propyl-2-Thiouracil. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13150-13168. [CrossRef]

- Marinova, P.; Stoitsov, D.; Burdzhiev, N.; Tsoneva, S.; Blazheva, D.; Slavchev, A.; Varbanova, E.; Penchev, P. Investigation of the Complexation Activity of 2,4-Dithiouracil with Au(III) and Cu(II) and Biological Activity of the Newly Formed Complexes. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6601. [CrossRef]

- Marinova, P.; Burdzhiev, N.; Blazheva, D.; Slavchev, A. Synthesis and Antibacterial Studies of a New Au(III) Complex with 6-Methyl-2-Thioxo-2,3-Dihydropyrimidin-4(1H)-One. Molbank 2024, 2024, M1827. [CrossRef]

- Ahmedova, A.; Marinova, P.; Paradowska, K.; Tyuliev, G.; Marinov, M.; Stoyanov, N. Spectroscopic study on the solid state structure of Pt(II) complexes of cycloalkanespiro-5-(2,4-dithiohydantoins), Bulg. Chem. Communic., 2024, Vol. 56, Special Issue C, 89-95. [CrossRef]

- Altowyan, M.S.; Soliman, S.M.; Al-Wahaib, D.; Barakat, A.; Ali, A.E.; Elbadawy, H.A. Synthesis of a New Dinuclear Ag(I) Complex with Asymmetric Azine Type Ligand: X-ray Structure and Biological Studies. Inorganics 2022, 10, 209. [CrossRef]

- Zimina, A.M.; Somov, N.V.; Malysheva, Y.B.; Knyazeva, N.A.; Piskunov, A.V.; Grishin, I.D. 12-Vertex clo-so-3,1,2- Ruthenadicarba-dodecaboranes with Chelate POP-Ligands: Synthesis, X-ray Study and Electrochemical Properties. Inorganics 2022, 10, 206. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shboul, T.M.A.; El-khateeb, M.; Obeidat, Z.H.; Ababneh, T.S.; Al-Tarawneh, S.S.; Al Zoubi, M.S.; Alshaer,W.; Abu Seni, A.; Qasem, T.; Moriyama, H.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization, Computational and Biological Activity of Some Schiff Bases and Their Fe, Cu and Zn Complexes. Inorganics 2022, 10, 112. [CrossRef]

- P. Marinova, M. Marinov, M. Kazakova, Y. Feodorova, D. Blazheva, A. Slavchev, H. Sbirkova-Dimitrova, V. Sarafian, N. Stoyanov, Crystal Structure of 5'-oxospiro-(fluorene-9, 4'-imidazolidine)-2'-thione and biological activities of its derivatives. Russ J Gen Chem 2021, 91(5), 939-946. [CrossRef]

- P. Marinova, M. Marinov, M. Kazakova, Y. Feodorova, D. Blazheva, A. Slavchev, D. Georgiev, I. Nikolova, H. Sbirkova-Dimitrova, V. Sarafian, N. Stoyanov, Copper(II) complex of bis(1',3'-hydroxymethyl)-spiro-(fluorine-9,4'-Imidazolidine)-2',5'-dione, cytotoxicity and antibacterial activity of its derivative and crystal structure of free ligand, Russ J Inorg. Chem. 2021, 66(13), 1925-1935. ISSN 0036-0236.

- Anife Ahmedova, Gordana Pavlović, Marin Marinov, Petya Marinova, Georgi Momekov, Katarzyna Paradowska, Stanislava Yordanova, Stanimir Stoyanov, Nikolay Vassilev, Neyko Stoyanov. Synthesis and anticancer activity of Pt(II) complexes of spiro-5-substituted 2,4-dithiohydantoins. Inorganica Chimica Acta, 2021, 528, Article number 120605. [CrossRef]

- Petja Marinova, Marin Marinov, Danail Georgiev, Maria Becheva, Plamen Penchev, Neyko Stoyanov. Synthesis and antimicrobial study of new Pt(IV) and Ru(III) complexes of fluorenylspirohydantoins. Rev. Roum. Chim. 2019, 64(7), 595-601;. [CrossRef]

- P. Marinova, M. Marinov, M. Kazakova, Y. Feodorova, P. Penchev, V. Sarafian, N. Stoyanov, Synthesis and in vitro activity of platinum (II) complexes of two fluorenylspirohydantoins against a human tumor cell line, Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment, 2014, 28 (2), 316-321. [CrossRef]

- P. Marinova, M. Marinov, N. Stoyanov. New metal complexes of cyclopentanespiro-5-hydantoine. Trakia Journal of Sciences, “30 years higher medical education, Stara Zagora” 2012, Vol. 10, Supplement 1, 84-87.

- P. E. Marinova, M. N. Marinov, M. H. Kazakova, Y. N. Feodorova, V. S. Sarafian, N. M. Stoyanov. Synthesis and bioactivity of new platinum and ruthenium complexes of 4-bromo-spiro-(fluorene-9,4'-imidazolidine)-2',5'-dithione. Bulgarian Chemical Communications, 2015, 47, Special issue A, 75 -79.

- Anife Ahmedova, Petja Marinova, Marin Marinov, Neyko Stoyanov. An integrated experimental and quantum chemical study on the complexation properties of (9’-fluorene)-spiro-5-hydantoin and its thio-analogues. J Mol. Str. 2016, 1108, 602-610. [CrossRef]

- Petja Marinova, Slava Tsoneva, Maria Frenkeva, Denica Blazheva, Aleksandar Slavchev and Plamen Penchev. New Cu(II), Pd(II) and Au(III) complexes with 2-thiouracil: Synthesis, Characteration and Antibacterial Studies. Russ J Gen Chem, 2022, 92(8), 1578–1584. [CrossRef]

- Petja Marinova, Stoyanka Nikolova, Slava Tsoneva. Synthesis of N-(1-(2-acetyl-4,5-dimethoxyphenyl)propan-2-yl)benzamide and its copper(II) complex. Russ J Gen Chem 2023, 93(1), 161-165.

- A. Ahmedova, V. Atanasov, P. Marinova, N. Stoyanov, M. Mitewa, Synthesis, characterization and spectroscopic properties of some 2-substituted 1,3-indandiones and their metal complexes. Central European Journal of Chemistry, 2009, 7(3), 429-438. [CrossRef]

- A. Ahmedova, P. Marinova, S. Ciattini, N. Stoyanov, M. Springborg, M. Mitewa, A combined experimental and theoretical approach for structural study on a new cinnamoyl derivative of 2-acetyl-1,3-indandione and its metal(II) complexes, Strucural Chemisry, 2009, 20, 101–111.

- A. Ahmedova, P. Marinova, G. Pavlović, M. Guncheva, N. Stoyanov, M. Mitewa. Structure and properties of a series of 2-cinnamoyl-1,3-indandiones and their metal complexes. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society, 2012, 9 (3), 297-306. [CrossRef]

- Iliana Nikolova, Marin Marinov, Petja Marinova, Atanas Dimitrov, Neyko Stoyanov. Cu(II) complexes of 4- and 5- nitro-substituted heteroaryl cinnamoyl derivatives and determining their anticoagulant activity. Ukrainian Food Journal 2016, 5(2), 326-349. doi. 10.24263/2304-974x-2016-5-2-12.

- P. E. Marinova, I. D. Nikolova, M. N. Marinov, S. H. Tsoneva, A. N. Dimitrov, N. M. Stoyanov. Ni(II) complexes of 4- and 5- nitro-substituted heteroaryl cinnamoyl derivatives. Bulgarian chemical communication 2017, 49, Special issue, 183-187.

- Frezza, M.; Hindo, S.; Chen, D.; Davenport, A.; Schmitt, S.; Tomco, D.; Dou Q. P. Novel metals and metal complexes as platforms for cancer therapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2010, 16(16), 1813–1825. [CrossRef]

- Haas, K.L.; Franz, K.J. Application of metal coordination chemistry to explore and manipulate cell biology. Chem Rev. 2010, 109(10), 4921–4960. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.K.; Melchart, M.; Habtemariam, A.; Sadler, P. J. Organometallic chemistry, biology and medicine: ruthenium arene anticancer complexes. Chem Commun. 2005,14(38), 4764–4776. [CrossRef]

- Salga, M.S.; Ali, H.M.; Abdulla, M.A.; Abdelwahab, S.I. Acute oral toxicity evaluations of some zinc(II) complexes derived from 1-(2- Salicylaldiminoethyl)piperazine schiff bases in rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2012, 13(2), 1393–1404. [CrossRef]

- Sekine, Y.; Nihei, M.; Kumai, R.; Nakao, H.; Murakami, Y.; Oshio, H. Investigation of the light-induced electron-transfer-coupled spin transition in a cyanide-bridged [Co₂Fe₂] complex by X-ray diffraction and absorption measurements. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 2014, 1(4), 540-543. [CrossRef]

- Matteppanavar, S.; Rayaprol, S.; Singh, K.; Raghavendra Reddy, V.; Angadi, B. Structural, magnetic, and dielectric properties of perovskite-type complex oxides La₃FeMnO₇ studied using X-ray diffraction. J. Mater. Sci., 2015, 50(13), 4980-4993. [CrossRef]

- Mustafin, E.S.; Mataev, M.M.; Kasenov, R.Z.; Pudov, A.M.; Kaykenov, D.A. Synthesis and X-ray diffraction studies of a new pyrochlore oxide (Tl₂Pb)(MgW)O₇. Inorganic Materials, 2014, 50(5), 672-675. [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.; Mostovoy, M. Multiferroics: a magnetic twist for ferroelectricity. Nature Materials, 2007, 6(1), 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Valencia, S.; Konstantinovic, Z.; Schmitz, D.; Gaupp, A. X-ray magnetic circular dichroism study of cobalt-doped ZnO. Physical Review B, 2011, 84, 024413. [CrossRef]

- Harder, R.; Robinson, I.K. Three-dimensional mapping of strain in nanomaterials using X-ray diffraction microscopy. New Journal of Physics, 2010, 12, 035019. [CrossRef]

- Newton, M.C.; Leake, S.J.; Harder, R.; Robinson, I.K. Three-dimensional imaging of strain in ZnO nanorods using coherent X-ray diffraction. Nature Materials 2010, 9, 120-125. [CrossRef]

- Cha, W.; Ulvestad, A.; Kim, J.W. Coherent diffraction imaging of crystal strains and phase transitions in complex oxide nanocrystals. Nature Communic. 2018, 9, 3422. [CrossRef]

- Diao, J.; Ulvestad, A. In situ study of ferroelastic domain wall dynamics in BaTiO₃ nanoparticles by X-ray diffraction microscopy. Physical Review Materials, 2020, 4, 053601. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Robinson, I.K. Real-time observation of defect dynamics during oxidation in Pt nanoparticles using coherent X-ray diffraction imaging. Nano Letters 2015, 15(7), 5044-5051. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, M.A.; Williams, G.J.; Vartanyants, I.A.; Harder, R.; Robinson, I.K. Three-dimensional mapping of a deformation field inside a nanocrystal using coherent X-ray diffraction. Nature 2006, 442, 63-66. [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Nam, D. Quantitative imaging of single, unstained viruses with coherent X-rays. Physical Review Letters, 2014, 101, 158101. [CrossRef]

- Prativa Shrestha, UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Principle, Parts, Uses, Limitations, 2023.

- Khalisanni Khalid, Ruzaina Ishak, Zaira Zaman Chowdhury, Chapter 15 - UV–Vis spectroscopy in non-destructive testing, Non-Destructive Material Characterization Methods, 2024, Pages 391-416. [CrossRef]

- Harris DC. Quantitative Chemical Analysis. 7th ed, 3rd printing. W. H. Freeman; 2007.

- Diffey BL. Sources and measurement of ultraviolet radiation. Methods. 2002;28(1):4-13. [CrossRef]

- Namioka T. Diffraction Gratings. In: Vacuum Ultraviolet Spectroscopy. Vol 1. Experimental Methods in Physical Sciences. Elsevier; 2000:347-377. [CrossRef]

- Mortimer Abramowitz and Michael W. Davidson. Photomultiplier Tubes. Molecular Expressions. Accessed April 25, 2021. https://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/primer/digitalimaging/concepts/photomultipliers.html.

- Picollo M, Aceto M, Vitorino T. UV-Vis spectroscopy. Phys Sci Rev. 2019;4(4). [CrossRef]

- What is a Photodiode? Working, Characteristics, Applications. Published online October 30, 2018. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://www.electronicshub.org/photodiode-working-characteristics-applications/.

- Amelio G. Charge-Coupled Devices. Scientific American. 1974;230(2):22-31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24950003.

- Hackteria. DIY NanoDrop. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://hackteria.org/wiki/File:NanoDropConceptSpectrometer2.png.

- Sharpe MR. Stray light in UV-VIS spectrophotometers. Anal Chem. 1984;56(2):339A-356A. [CrossRef]

- Liu P-F, Avramova LV, Park C. Revisiting absorbance at 230 nm as a protein unfolding probe. Anal Biochem. 2009;389(2):165-170. [CrossRef]

- Kalb V., Bernlohr R. A New Spectrophotometric Assay for Protein in Cell Extracts. Anal Biochem. 1977;82:362-371. [CrossRef]

- Bosch Ojeda C, Sanchez Rojas F. Recent applications in derivative ultraviolet/visible absorption spectrophotometry: 2009–2011. Microchem J. 2013;106:1-16. [CrossRef]

- Domingo C, Saurina J. An overview of the analytical characterization of nanostructured drug delivery systems: Towards green and sustainable pharmaceuticals: A review. Anal Chim Acta. 2012;744:8-22. [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad J, Sharma S, Hatware KV. Review on Characteristics and Analytical Methods of Tazarotene: An Update. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2020;50(1):90-96. [CrossRef]

- Gendrin C, Roggo Y, Collet C. Pharmaceutical applications of vibrational chemical imaging and chemometrics: A review. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;48(3):533-553. [CrossRef]

- Lourenço ND, Lopes JA, Almeida CF, Sarraguça MC, Pinheiro HM. Bioreactor monitoring with spectroscopy and chemometrics: a review. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404(4):1211-1237. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Rojas F, Bosch Ojeda C. Recent development in derivative ultraviolet/visible absorption spectrophotometry: 2004–2008. Anal Chim Acta. 2009;635(1):22-44. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson K, McVey AF, Clark IBN, Swain PS, Pilizota T. General calibration of microbial growth in microplate readers. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):38828. [CrossRef]

- Tadesse Wondimkun Z. The Determination of Caffeine Level of Wolaita Zone, Ethiopia Coffee Using UV-visible Spectrophotometer. Am J Appl Chem. 2016;4(2):59. [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Wang H, Zhan J, Huang W. Review of recent UV–Vis and infrared spectroscopy researches on wine detection and discrimination. Appl Spectrosc Rev. 2018;53(1):65-86. [CrossRef]

- Leong Y, Ker P, Jamaludin M, et al. UV-Vis Spectroscopy: A New Approach for Assessing the Color Index of Transformer Insulating Oil. Sensors. 2018;18(7):2175. [CrossRef]

- Brown JQ, Vishwanath K, Palmer GM, Ramanujam N. Advances in quantitative UV–visible spectroscopy for clinical and pre-clinical application in cancer. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009;20(1):119-131. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro HM, Touraud E, Thomas O. Aromatic amines from azo dye reduction: status review with emphasis on direct UV spectrophotometric detection in textile industry wastewaters. Dyes Pigm. 2004;61(2):121-139. [CrossRef]

- Kristo E, Hazizaj A, Corredig M. Structural Changes Imposed on Whey Proteins by UV Irradiation in a Continuous UV Light Reactor. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(24):6204-6209. [CrossRef]

- Lange R, Balny C. UV-visible derivative spectroscopy under high pressure. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. 2002;1595(1-2):80-93. [CrossRef]

- Tom J, Jakubec PJ, Andreas HA. Mechanisms of Enhanced Hemoglobin Electroactivity on Carbon Electrodes upon Exposure to a Water-Miscible Primary Alcohol. Anal Chem. 2018;90(9):5764-5772. [CrossRef]

- Patel MUM, Demir-Cakan R, Morcrette M, Tarascon J-M, Gaberscek M, Dominko R. Li-S Battery Analyzed by UV/Vis in Operando Mode. ChemSusChem. 2013;6(7):1177-1181. [CrossRef]

- Begum R, Farooqi ZH, Naseem K, et al. Applications of UV/Vis Spectroscopy in Characterization and Catalytic Activity of Noble Metal Nanoparticles Fabricated in Responsive Polymer Microgels: A Review. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2018;48(6):503-516. [CrossRef]

- Behzadi S, Ghasemi F, Ghalkhani M, et al. Determination of nanoparticles using UV-Vis spectra. Nanoscale. 2015;7(12):5134-5139. [CrossRef]

- Kazuo Nakamoto, Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds Part A: Theory and Applications in Inorganic Chemistry, Sixth Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, 2009.

- Kazuo Nakamoto, Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds Part B: Applications in Coordination, Organometallic, and Bioinorganic Chemistry, Sixth Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, 2009.

- Infrared Spectroscopy: Perspectives and Applications, Marwa El-Azazy, Khalid Al-Saad, Ahmed S. El-Shafie, Books on Demand, 2023, ISBN 1803562811, 9781803562810;

- James M. Thompson, Infrared Spectroscopy, 1st Edition, 2018, New York, . [CrossRef]

- Barbara H. Stuart, Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications, 2004, John Wiley & Sons ISBN:9780470854273. [CrossRef]

- Marwa El-Azazy, Ahmed S. El-Shafie and Khalid Al-Saad. Infrared Spectroscopy - Principles, Advances, and Applications, 2019, IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Robert T. Conley, Infrared spectroscopy, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, 1972.

- Brian C. Smith, Fundamentals of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, 2nd Edition, 2011, Boca Raton. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Reguant, A., Reis, H., Medveď, M., Luis, J. M., & Zaleśny, R. A New Computational Tool for Interpreting the Infrared Spectra of Molecular Complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 11658-11664. [CrossRef]

- Golea, C. M.; Codină, G. G.; Oroian, M. Prediction of Wheat Flours Composition Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry (FT-IR). Food Control 2023, 143, 109318. [CrossRef]

- Yaman, H.; Aykas, D. P.; Rodriguez-Saona, L. E. Monitoring Turkish White Cheese Ripening by Portable FT-IR Spectroscopy. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1107491. [CrossRef]

- Yeongseo An, Sergey L. Sedinkin and Vincenzo Venditti. Solution NMR methods for structural and thermodynamic investigation of nanoparticle adsorption equilibria. Nanoscale Adv., 2022, 4, 2583-2607. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohan, A. B. A. Andersen, J. Mareš, N. D. Jensen, U. G. Nielsen, J. Vaara. Unravelling the effect of paramagnetic Ni²⁺ on the ¹³C NMR shift tensor for carbonate in Mg₂₋ₓNiₓ Al layered double hydroxides by quantum-chemical computations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Uzal-Varela, F. Lucio-Martínez, A. Nucera, M. Botta, D. Esteban-Gómez, L. Valencia, A. Rodríguez-Rodríguez, C. Platas-Iglesias. A systematic investigation of the NMR relaxation properties of Fe(III)-EDTA derivatives and their potential as MRI contrast agents. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ö. Üngör, S. Sanchez, T. M. Ozvat, J. M. Zadrozny. Asymmetry-enhanced 59Co NMR thermometry in Co(III) complexes. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, H. T. Fei, G. T. Liu, W. Wang, Y. J. Sun, C. J. Wu. Exploring paramagnetic NMR and EPR for studying the bonding in actinide complexes. Dalton Transactions, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Göthner, K. Lehmann, D. Grote, A. L. Spek, J. P. Hill, M. Ikeda. NMR studies on manganese(II) complexes for enhanced relaxivity in MRI applications. Inorg. Chem., 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Shin, S. J. Lee, T. J. Kim, K. G. Lee, D. H. Kang, J. T. Son. Analyzing 31P NMR shifts in molybdenum phosphide nanoclusters. J. Mol.Str., 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Adams, C. J. Hines, M. L. Rodriguez. Utilizing high-field NMR for detection of low-spin iron(III) centers in bioinorganic complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem., 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Bai, A. Y. Lee, J. Chen, Z. Ma. Coordination dynamics in copper(I) complexes: A study through variable-temperature NMR. Inorg. Chem. Commun., 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. L. Brett, R. D. Armstrong, S. P. Thomas, C. J. McQueen. Exploring transition metal complex environments via 1H and 31P NMR spectroscopy. Chemistry - A European Journal, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Middleton, D.A., Griffin, J., Esmann, M., Fedosova, N.U. Solid-state NMR chemical shift analysis for determining the conformation of ATP bound to Na,K-ATPase in its native membrane. RSC Advances, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E., et al. Recent progress in solid-state NMR of spin-½ low-γ nuclei applied to inorganic materials. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., et al. Advanced Solid-State NMR Studies of Transition Metal Complexes. J. Americ. Chem.l Soc., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sahoo, S. K. Structural insights into metallocomplexes via SSNMR and DFT. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Pyykkö, P., et al. Analyzing the crystal lattice effects in inorganic complexes by MAS SSNMR. Dalton Transactions, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Saito, T. Exploring ligand field environments in metal complexes by SSNMR. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry, 2019. [CrossRef]

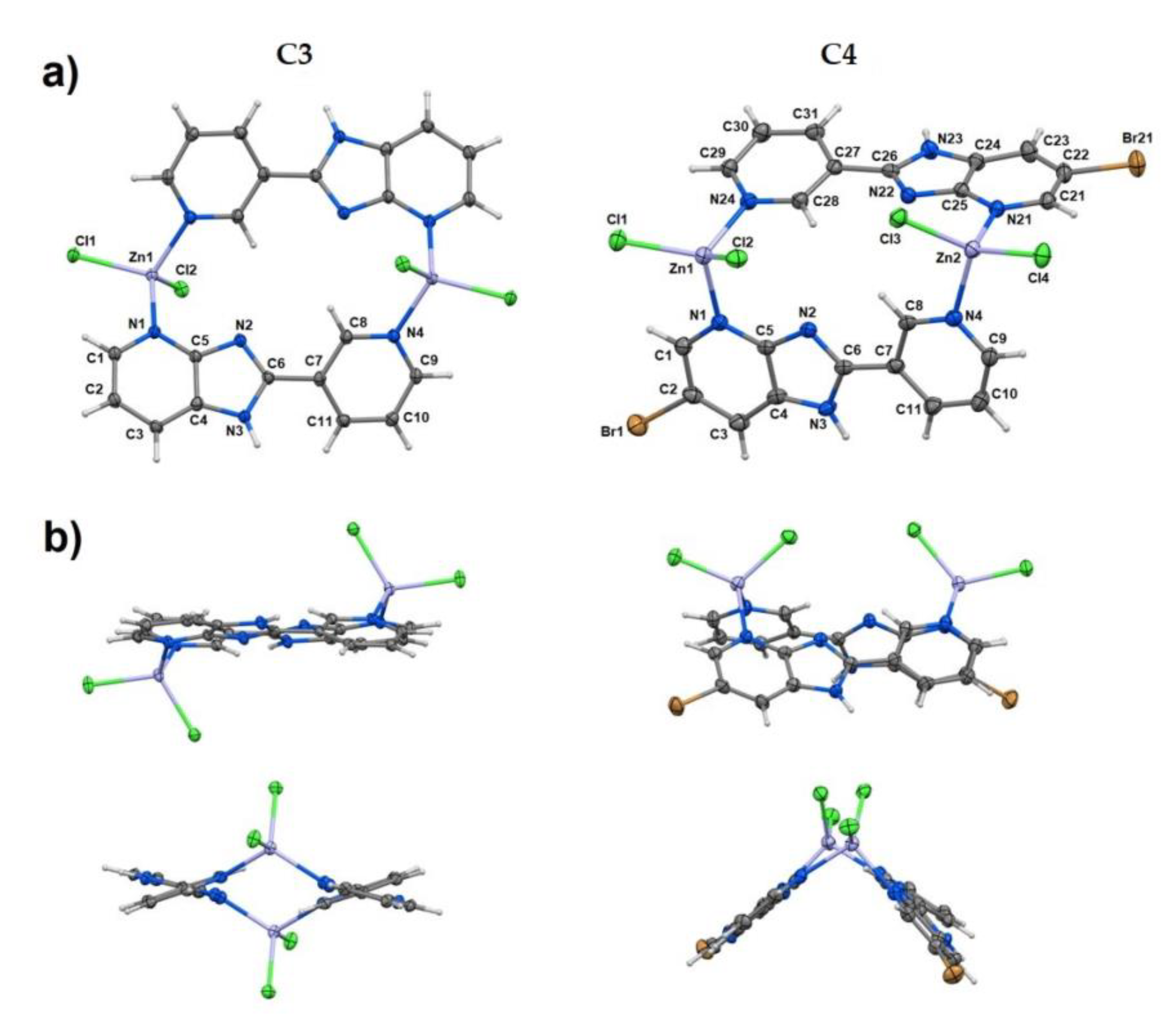

- Raducka, A.; Swi˛atkowski, M.; ´ Korona-Głowniak, I.; Kapro ´n, B.; Plech, T.; Szczesio, M.; Gobis, K.; Szynkowska-Jó ´zwik, M.I.; Czylkowska, A. Zinc Coordination Compounds with Benzimidazole Derivatives: Synthesis, Structure, Antimicrobial Activity and Potential Anticancer Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6595. [CrossRef]

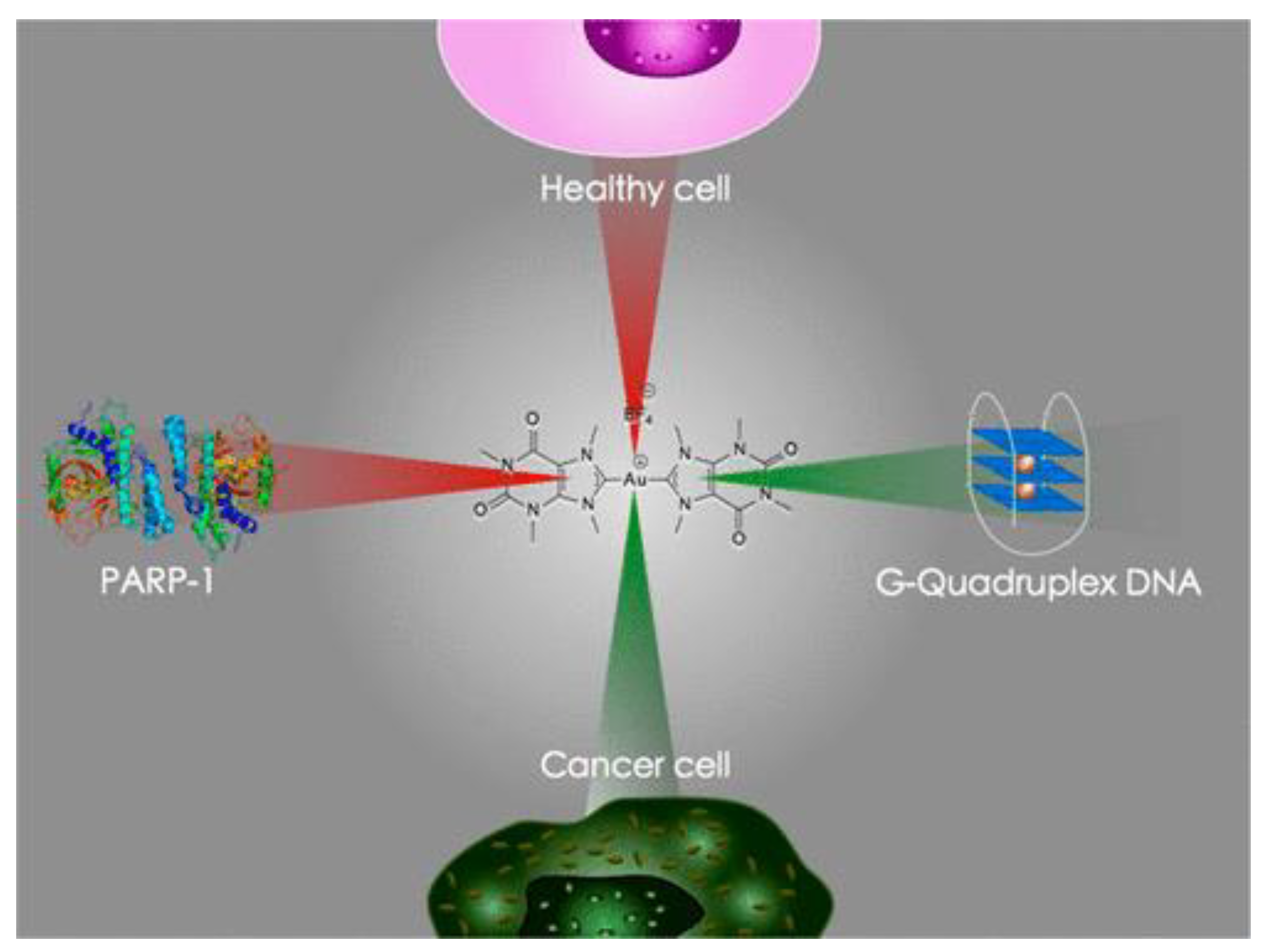

- Jing-Jing Zhang, Julienne K. Muenzner, Mohamed A. Abu el Maaty, Bianka Karge, Rainer Schobert, Stefan Wölfl and Ingo Ott. A Multi-target caffeine derived rhodium(I) N-heterocyclic carbene complex: evaluation of the mechanism of action. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45(33), 13161. [CrossRef]

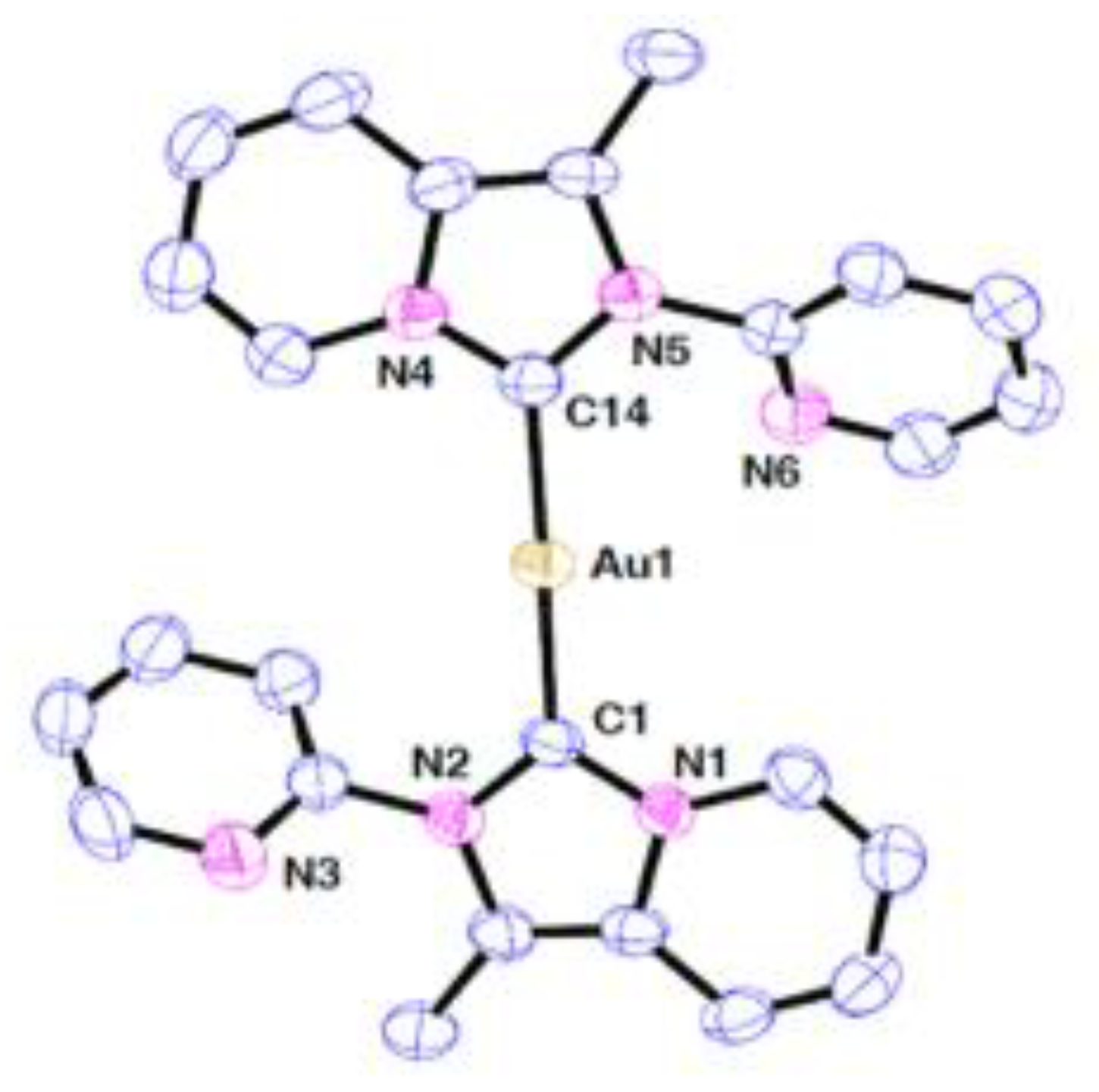

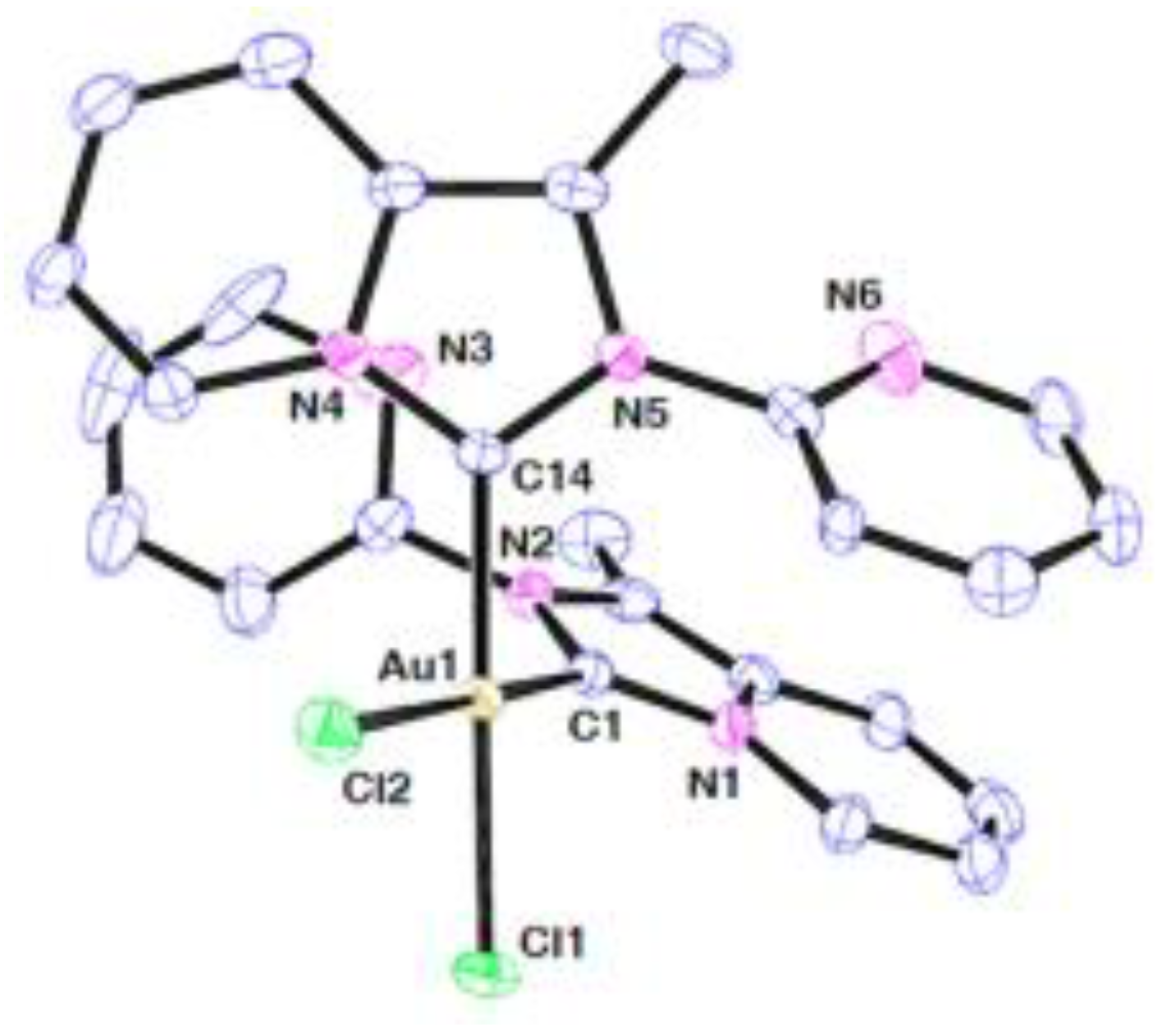

- Bidyut Kumar Rana, Abhishek Nandy, Valerio Bertolasi, Christopher W. Bielawski, Krishna Das Saha, Joydev Dinda Novel gold(I) − and gold(III) − N-heterocyclic carbene complexes: synthesis and evaluation of their anticancer properties. Organometallics 2014, 33(10), 2544–2548. [CrossRef]

- Maura Pellei, Valentina Gandin, Marika Marinelli, Cristina Marzano, Muhammed Yousufuddin, H V Rasika Dias, Carlo Santini. Synthesis and biological activity of ester- and amide-functionalized imidazolium salts and related water-soluble coinage metal N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. Inorg Chem. 2012, 51(18), 9873–9882. [CrossRef]

- Maroto-Díaz, M.; Elie, B.T.; Gómez-Sal, P.; et al. Synthesis and anticancer activity of carbosilane metallodendrimers based on arene ruthenium (II) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45(16), 7049–7066. [CrossRef]

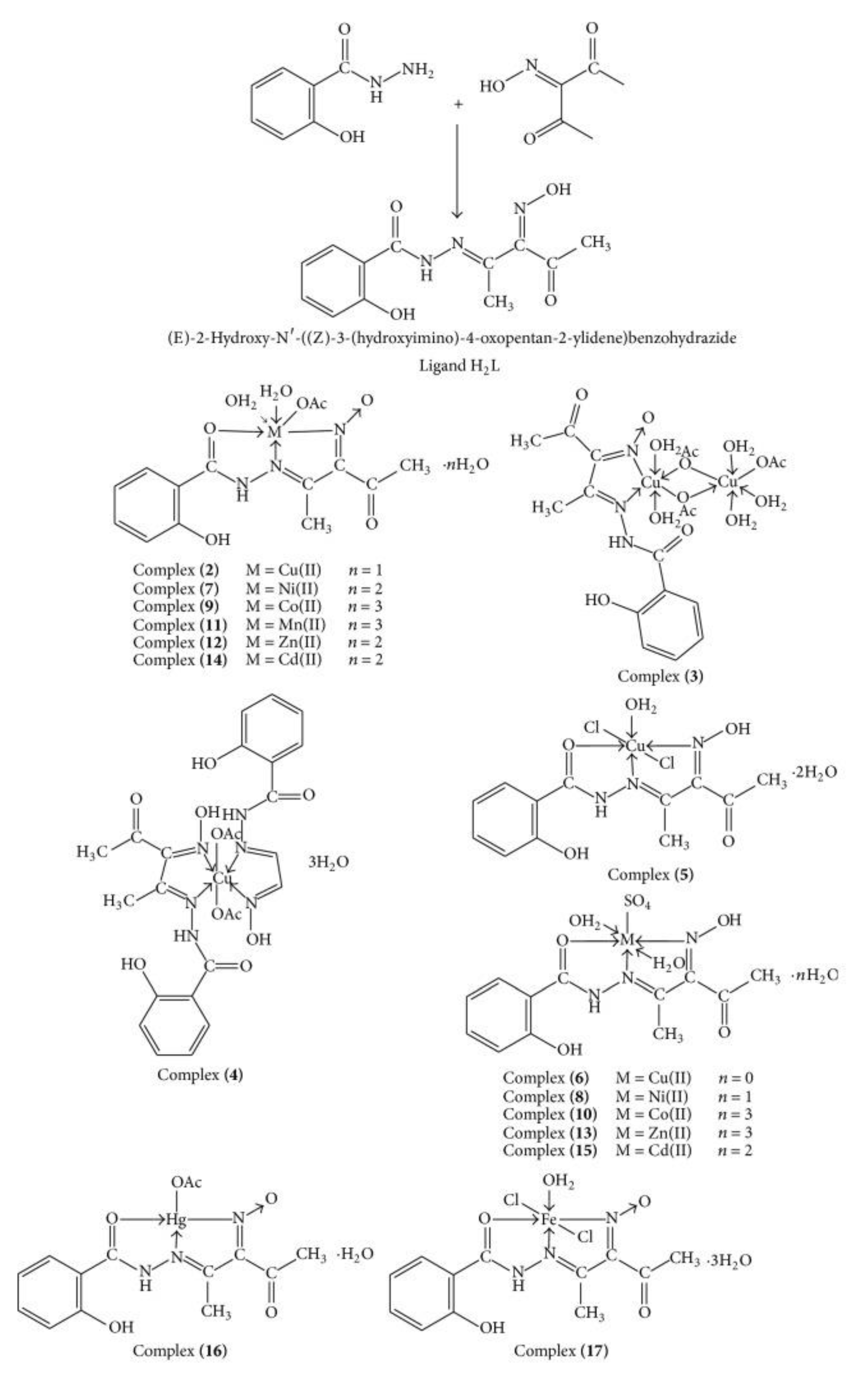

- El-Tabl A.S.; El-Waheed M.M.A.; Wahba, M.A.; El-Halim N. A.; El-Fadl A. Synthesis, characterization, and anticancer activity of new metal complexes derived from 2-Hydroxy-3-(hydroxyimino)-4-oxopentan-2-ylidene benzohydrazide. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2015, 1, 2–14. [CrossRef]

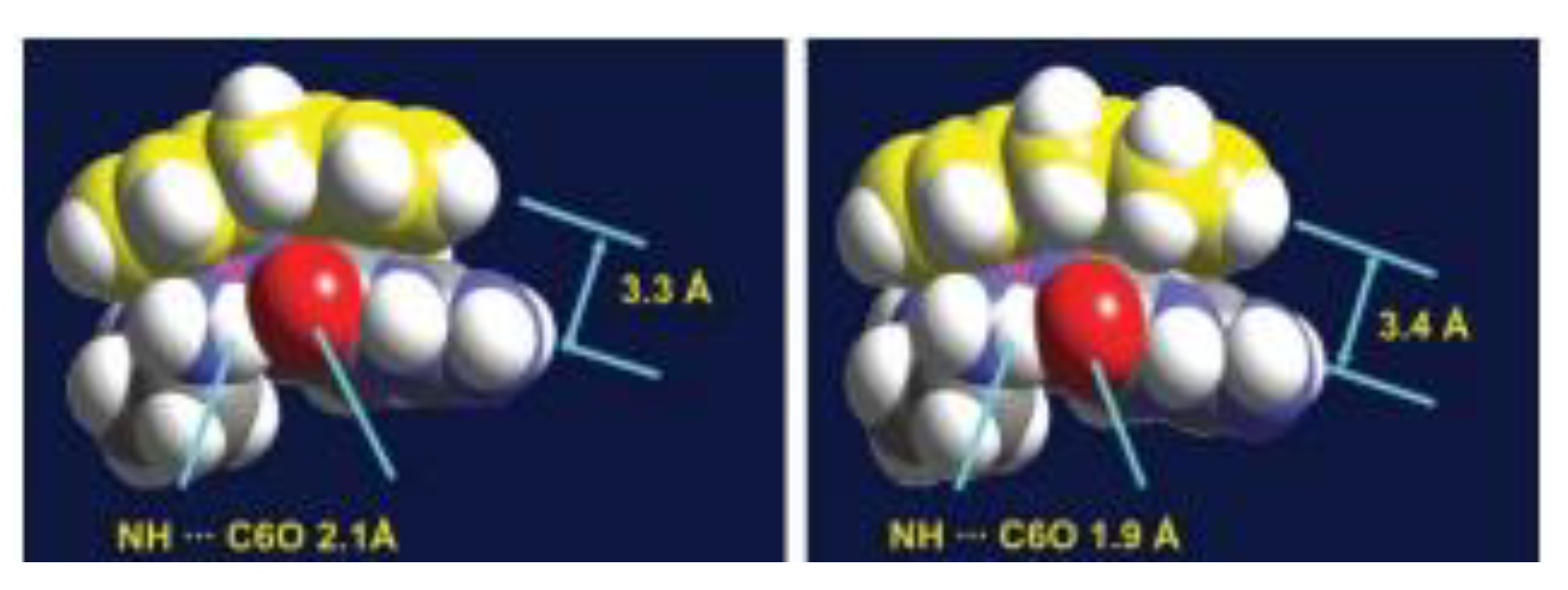

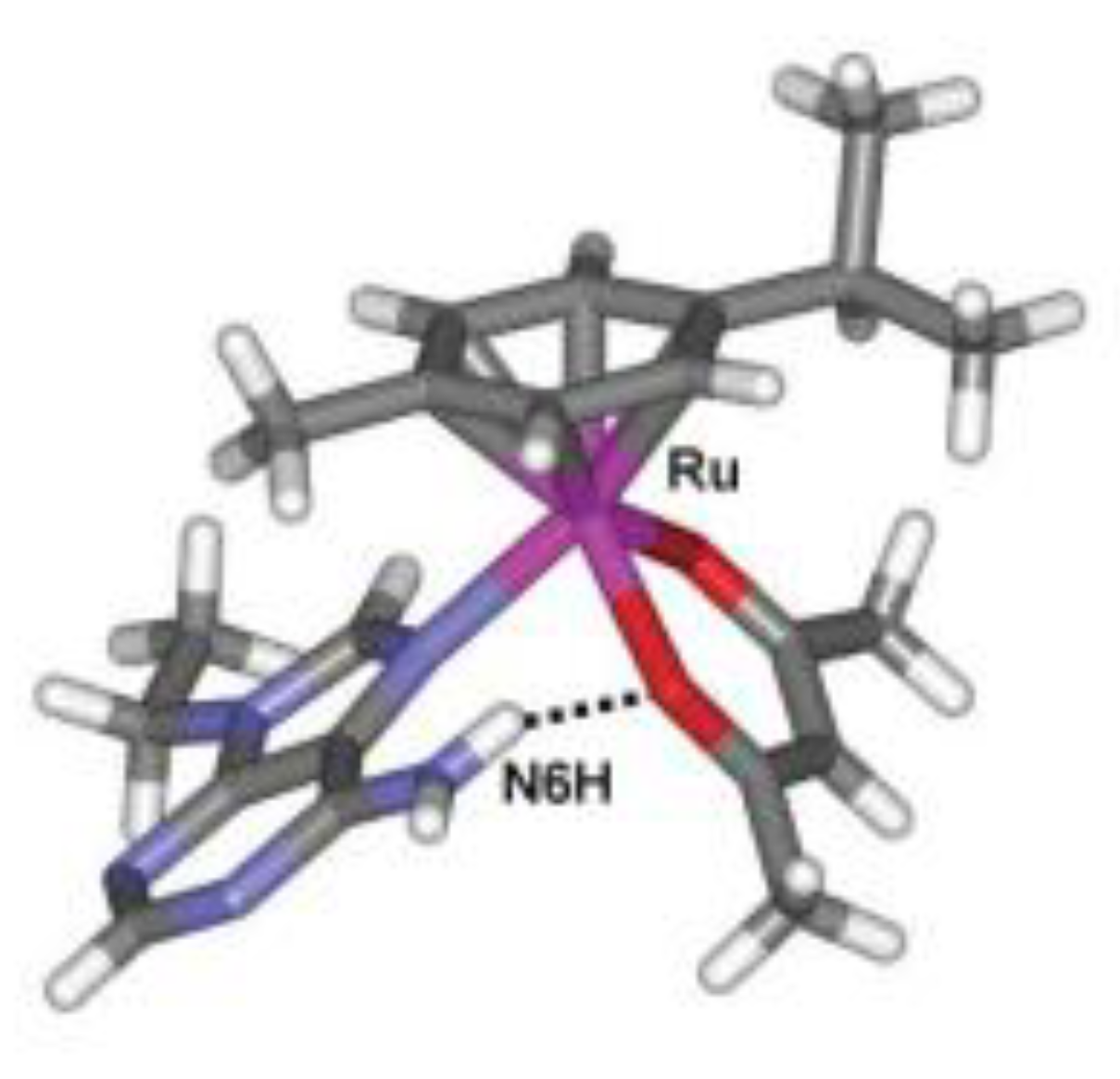

- H. Chen, J. A. Parkinson, S. Parsons, R. A. Coxall, R. O. Gould and P. J. Sadler, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 3064.

- R. Ferna´ndez, M. Melchart, A. Habtemariam, S. Parsons and P. J. Sadler, Chem. Eur. J., 2004, 10, 5173. http://pubs.rsc.org |. [CrossRef]

- Soroceanu, A.; Bargan, A. Advanced and Biomedical Applications of Schiff-Base Ligands and Their Metal Complexes: A Review. Crystals 2022, 12, 1436. [CrossRef]

- Ndagi, U.; Mhlongo, N.; Soliman, M. E. Metal complexes in cancer therapy - an update from drug design perspective. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017, 11, 599-616. [CrossRef]

- Juliana Jorge, Kristiane Fanti Del Pino Santos, Fernanda Timóteo, Rafael Rodrigo Piva Vasconcelos, Osmar Ignacio Ayala Cáceres, Isis Juliane Arantes Granja, David Monteiro de Souza, Tiago Elias Allievi Frizon, Giancarlo Di Vaccari Botteselle, Antonio Luiz Braga, Sumbal Saba, Haroon ur Rashid and Jamal Rafique, Recent Advances on the Antimicrobial Activities of Schiff Bases and their Metal Complexes: An Updated Overview, Current Medicinal Chemistry 2024, 31(17), 2330 – 2344. [CrossRef]

- Benoît Bertrand, Loic Stefan, Marc Pirrotta, David Monchaud, Ewen Bodio, Philippe Richard, Pierre Le Gendre, Elena Warmerdam, Marina H de Jager, Geny M M Groothuis, Michel Picquet, Angela Casini. Caffeine-based gold(I) N – heterocyclic carbenes as possible anticancer agents: synthesis and biological properties. Inorg Chem. 2014, 53(4), 2296–2303. [CrossRef]

- Hackenberg, F; Mueller-Bunz, H; Smith, R; Streciwilk, W; Zhu, X; Tacke, M . Novel ruthenium(II) and gold(I) NHC complexes: synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of their anticancer properties. Organometallics 2013, 32(19), 5551–5560. [CrossRef]

- Dragutan, I.; Dragutan, V.; Demonceau, A. Editorial of special issue ruthenium complex: the expanding chemistry of the ruthenium complexes. Molecules 2015, 20(9), 17244–17274. [CrossRef]

- Mélanie Chtchigrovsky, Laure Eloy, Hélène Jullien, Lina Saker, Evelyne Ségal-Bendirdjian, Joel Poupon, Sophie Bombard, Thierry Cresteil,Pascal Retailleau, Angela Marinetti. Antitumor trans-N-heterocyclic carbene-amine-Pt(II) complexes: synthesis of dinuclear species and exploratory investigations of DNA binding and cytotoxicity mechanisms. J Med Chem. 2013, 56(5), 2074–2086. [CrossRef]

- El-Tabl A.S.; El-Waheed M.M.A.; Wahba, M.A.; El-Halim N. A.; El-Fadl A. Synthesis, characterization, and anticancer activity of new metal complexes derived from 2-Hydroxy-3-(hydroxyimino)-4-oxopentan-2-ylidene benzohydrazide. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2015, 1, 2–14. [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, H. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Molybdenum Carbonyl Complexes and Their Peptide Conjugates [dissertation]. Julius Maximilians-Universität Würzburg. 2012, 6–137. https://opus.bibliothek.uni-wuerzburg.de/opus4-wuerzburg/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/5907/file/hendrikpfeifferdiss.pdf.

- Carter, R.; Westhorpe, A.; Romero, M.J.; Habtemariam, A.; Gallevo, C. R.; Bark, Y.; Menezes, N.; Sadler, P. J.; Sharma R. A. Radiosensitisation of human colorectal cancer cells by ruthenium (II) arene anticancer complexes. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 20569. [CrossRef]

- Raosaheb, G.; Sinha, S.; Chhabra, M.; Paira, P. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters synthesis of novel anticancer ruthenium – arene pyridinylmethylene scaffolds via three-component reaction. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2016, 26, 2695–2700. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qian, H.; Yiu, S.; Sun, J.; Zhu, G. Multi-targeted organometallic ruthenium (II) – arene anticancer complexes bearing inhibitors of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1: a strategy to improve cytotoxicity. J Inorg Biochem. 2014, 31, 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Marta Martínez-Alonso, Natalia Busto, Félix A Jalón, Blanca R Manzano, José M Leal, Ana M Rodríguez, Begoña García, Gustavo Espino. Derivation of structure−activity relationships from the anticancer properties of ruthenium(II) arene complexes with 2-aryldiazole ligands. Inorg Chem. 2014, 53(20), 11274–11288. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Hanif, Alexey A. Nazarov, Christian G. Hartinger, Wolfgang Kandioller, Michael A. Jakupec, Vladimir B. Arion, Paul J. Dyson and Bernhard K. Keppler. Osmium (II)– versus ruthenium (II)– arene carbohydrate-based anticancer compounds: similarities and differences. Dalton Trans. 2010;39(31):7345–7352. [CrossRef]

- Maroto, B. T. Elie, M. P. Gómez-Sal, J. Pérez, R. Gomez Ramirez, M. Contel and J. de la Mata, Ruthenium (II) complexes containing aroylhydrazone ligands. J Organomet Chem. 2016, 807, 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Millett, A. J.; Habtemariam, A.; Romero-Canelo, I.; Clarkson, G. J.; Sadler, P. J. Contrasting anticancer activity of half-sandwich iridium(III) complexes bearing functionally diverse 2-phenylpyridine ligands. Organometallics 2015, 34(11), 2683–2694. [CrossRef]

- Virtudes Moreno, Mercè Font-Bardia, Teresa Calvet, Julia Lorenzoc, Francesc X. Avilésc, M. Helena Garcia, Tânia S. Morais, Andreia Valente, M. Paula Robalo. DNA interaction and cytotoxicity studies of new ruthenium(II) cyclopentadienyl derivative complexes containing heteroaromatic ligands. J Organomet Chem. 2014, 105(2), 241–249. [CrossRef]

- Pedro R. Florindo, Diane M. Pereira, Pedro M. Borralho. Cecília M. P. Rodrigues, M. F. M. Piedade, Ana C. Fernandes. Cyclopentadienyl-ruthenium (II) and iron (II) organometallic compounds with carbohydrate derivative ligands as good colorectal anticancer agents. J Med Chem. 2015, 58(10), 4339–4347. [CrossRef]

- Qamar, B.; Liu, Z.; Hands-Portman, I. Organometallic iridium(III) anticancer complexes with new mechanisms of action: NCI-60 screening, mitochondrial targeting, and apoptosis. Chem Biol. 2013, 8(6), 1335–1345. [CrossRef]

- Wheate, N.J.; Walker, S.; Craig, G.E.; Oun, R. The status of platinum anticancer drugs in the clinic and in clinical trials. Dalton Trans. 2012, 39(35), 8113–8127. [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Emadi, A. Ruthenium-based chemotherapeutics: are they ready for prime time? Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010, 66(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Szymański, P.; Fraczek, T.; Markowicz, M.; Mikiciuk-Olasik, E. Development of copper based drugs, radiopharmaceuticals and medical materials. Biometals. 2012, 25(6), 1089–1112. [CrossRef]

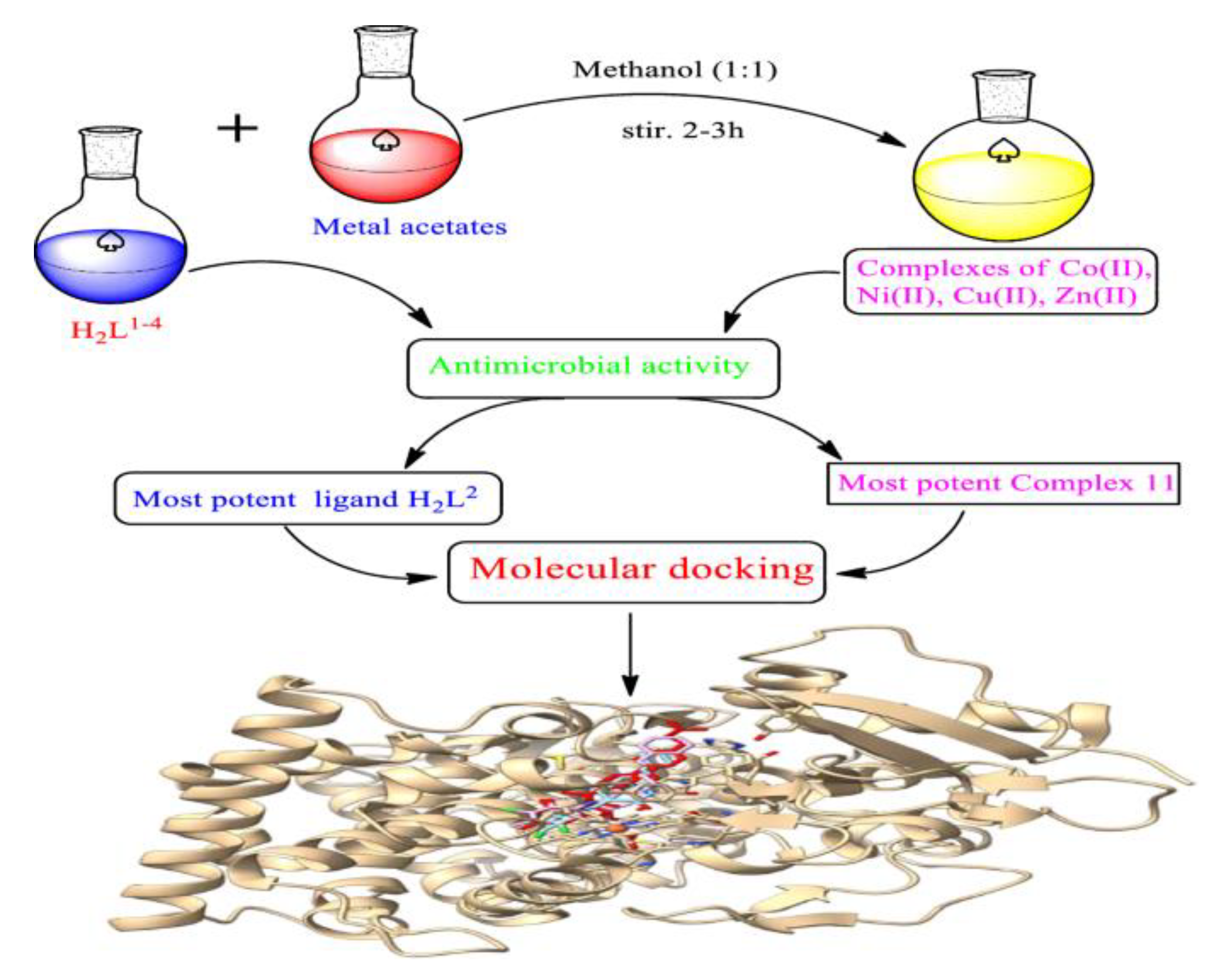

- Bansuri K Nandaniya, Siva Prasad Das, Divyesh R Chhuchhar, Mayur G Pithiya, Mayur D Khatariya, Darsan Jani and Kiran B Dangar. Schiff base metal complexes: Advances in synthesis, characterization, and exploration of their biological potential. International Journal of Chemical Studies 2024; 12(5): 131-134. P-ISSN: 2349–8528 E-ISSN: 2321–4902.

- Farrell, N. Transition metal complexes as drugs and chemotherapeutic agents. Met Complexes Drugs Chemother Agents. 1989, 11, 809–840.

- Uversky, V.N.; Kretsinger, R. H.; Permyakov, E. A. Encyclopedia of Metalloproteins. Vol. 1. New York: Springer; 2013, 1–89.

- Iakovidis, I.; Delimaris, I.; Piperakis, S. M. Copper and its complexes in medicine: a biochemical approach. Mol Biol Int. 2011, 2011, 594529. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M.R.; Vivas-Mejia, P.E. Nanoparticles as drug delivery systems in cancer medicine: emphasis on RNAi-containing nanoliposomes. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2013, 6(11), 1361–1380. [CrossRef]

- Ventola, C. L. The nanomedicine revolution: part 2: current and future clinical applications. P T. 2012, 37(10), 582–591. PMCID: PMC3474440 PMID: 23115468.

- Kargar, H.; Fallah-Mehrjardi, M.; Behjatmanesh-Ardakani, R.; Rudbari, H.A.; Ardakani, A.A.; Sedighi-Khavidak, S.; Munawarf, K.S.; Ashfaq, M.; Tahir, M.N. Synthesis, spectral characterization, crystal structures, biological activities, theoretical calculations and substitution effect of salicylidene ligand on the nature of mono and dinuclear Zn(II) Schiff base complexes. Polyhedron 2022, 213, 115636. [CrossRef]

- Nath, B.D.; Islam, M.; Karim, R.; Rahman, S.; Shaikh, A.A.; Georghiou, P.E.; Menelaou, M. Recent Progress in Metal-Incorporated Acyclic Schiff-Base Derivatives: Biological Aspects. Chemistry Select 2022, 7, e20210429. [CrossRef]

- Abid, K.K.; Al-Bayati, R.H.; Faeq, A.A. Transition metal complexes of new N-amino quinolone derivative; synthesis, characterization, thermal study and antimicrobial properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 6, 29–35.

- Abu-Dief, M.; Nassr, L.A.E. Tailoring, physicochemical characterization, antibacterial and DNA binding mode studies of Cu(II) Schiff bases amino acid bioactive agents incorporating 5-bromo- 2-hydroxybenzaldehyde. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2015, 12, 943–955. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13738-014-0557-9.

- Abdel-Rahman, L.H.; Abu-Dief, A.M.; Hashem, N.A.; Seleem, A.A. Recent advances in synthesis, characterization and biological activity of nano sized Schiff base amino acid M(II) complexes. Int. J. Nanomater. Chem. 2015, 1, 79–95. [CrossRef]

- Yousif, E.; Majeed, A.; Al-Sammarrae, K.; Salih, N.; Salimon, J.; Abdullah, B. Metal complexes of Schiff base: Preparation, characterization and antibacterial activity. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, 1639–1644. [CrossRef]

- Horozic, E.; Suljagic, J.; Suljkanovic, M. Synthesis, characterization, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of Copper (II) complex with Schiff base derived from 2,2-dihydroxyindane-1, 3-dione and Tryptophan. Am. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 9, 9–13. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Yamin, A.A.; Abduh, M.S.; Saghir, S.A.M.; Al-Gabri, N. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activities of New Schiff Base Compound and Its Lanthanide Complexes. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 454. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Sun, D.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Chen, L. Discovery of metal-based complexes as promising antimicrobial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 224, 113696. [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S.; Arjmand, F.; Zhang, Q.; Ahmad, M.; Khan, A.; Toupet, L. Molecular docking, DFT and antimicrobial studies of Cu(II) complex as topoisomerase I inhibitor. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 39, 2092–2105. [CrossRef]

- Lobana, T.S.; Kaushal, M.; Bala, R.; Nim, L.; Paul, K.; Arora, D.S.; Bhatia, A.; Arora, S.; Jasinski, J.P. Di-2-pyridylketone-N(1)- substituted thiosemicarbazone derivatives of copper(II): Biosafe antimicrobial potential and high anticancer activity against immortalized L6 rat skeletal muscle cells. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 212, 111205. [CrossRef]

- Halawa, A.H.; El-Gilil, S.M.A.; Bedair, A.H.; Shaaban, M.; Frese, M.; Sewald, N.; Eliwa, E.M.; El-Agrody, A.M. Synthesis, biological activity and molecular modeling study of new Schiff bases incorporated with indole moiety. Z. Naturforsch. 2017, 72, 467–475. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Singh, V.K.; Kumar, G. Synthesis, Antimicrobial Evaluation of Substituted Indole and Nitrobenzenamine based Cr(III), Mn(III) and Fe(III) Metal Complexes. Drug Res. 2021, 71, 455–461. [CrossRef]

- Al Zamil, N.O. Synthesis, DFT calculation, DNA-binding, antimicrobial, cytotoxic and molecular docking studies on new complexes VO(II), Fe(III), Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) of pyridine Schiff base ligand. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 065401. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.G.; Poojary, B. Synthesis of novel Schiff bases containing arylpyrimidines as promising antibacterial agents. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02318. [CrossRef]

- Benabid, W.; Ouari, K.; Bendia, S.; Bourzami, R.; Ali, M.A. Crystal structure, spectroscopic studies, DFT calculations, cyclic voltammetry and biological activity of a copper (II) Schiff base complex. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1203, 127313. [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, K.H.M.E.; Hashemi, M.; Hassan, M.; Kobarfard, F.; Mohebbi, S. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of Schiff bases of 5-substituted isatins. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2016, 27, 221–225. [CrossRef]

- El-Faham, A.; Hozzein, W.N.; Wadaan, M.A.M.; Khattab, S.N.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Fun, H.-K.; Siddiqui, M.R. Microwave Synthesis, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Activity of Some Novel Isatin Derivatives. J. Chem. 2015, 2015, 716987. [CrossRef]

- Dikio, C.W.; Okoli, B.J.; Mtunzi, F.M. Synthesis of new anti-bacterial agents: Hydrazide Schiff bases of vanadium acetylacetonate complexes. Cogent Chem. 2017, 3, 1336864. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hiyari, B.A.; Shakya, A.K.; Naik, R.R.; Bardaweel, S. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Schiff Bases of Isoniazid and Evaluation of Their Anti-Proliferative and Antibacterial Activities. Molbank 2021, 2021, M1189. [CrossRef]

- Fonkui, T.Y.; Ikhile, M.I.; Njobeh, P.B.; Ndinteh, D.T. Benzimidazole Schif base derivatives: Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity. BMC Chem. 2019, 13, 127. [CrossRef]

- Alterhoni, E.; Tavman, A.; Hacioglu, M.; Sahin, O.; Tan, A.S.B. Synthesis, structural characterization and antimicrobial activity of Schiff bases and benzimidazole derivatives and their complexes with CoCl2 , PdCl2 , CuCl2 and ZnCl2 . J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1229, 129498. [CrossRef]

- Kais, R.; Adnan, S. Synthesis, Identification and Studying Biological Activity of Some Heterocyclic Derivatives from 3, 5- Dinitrosalicylic Acid. IOP Conf. Ser. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1234, 01209.. [CrossRef]

- Govindarao, K.; Srinivasan, N.; Suresh, R. Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial Evaluation of Novel Schiff Bases of Aryl Amines Based 2-Azetidinones and 4-Thiazolidinones. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2020, 13, 168–172. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.; Behera, S.; Behura, R.; Shubhadarshinee, L.; Mohapatra, P.; Barick, A.K.; Jali, B.R. Antibacterial Activity of Thiazole and its Derivatives: A Review. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2022, 12, 2171–2195. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Teng, G.; Li, D.; Hou, R.; Xia, Y. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of novel Schiff bases of thiosemicarbazone derivatives with adamantane moiety. Med. Chem. Res. 2021, 30, 1534–1540. [CrossRef]

- Yakan, H. Preparation, structure elucidation, and antioxidant activity of new bis(thiosemicarbazone) derivatives. Turk. J. Chem. 2020, 44, 1085–1099. [CrossRef]

- Vimala Joice, M.; Metilda, P. Synthesis, characterization and biological applications of curcumin-lysine based Schiff base and its metal complexes. J. Coord. Chem. 2021, 74, 2395–2406. [CrossRef]

- Omidi, S.; Kakanejadifard, A. A review on biological activities of Schiff base, hydrazone, and oxime derivatives of curcumin. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 30186–30202. [CrossRef]

- Plumb, J.A. Cell sensitivity assays: Clonogenic assay. Methods Mol. Med. 2004, 88, 159–164. https://link.springer.com/protocol/10.1385/1-59259-687-8:17.

- Sundriyal, S.; Sharma, R.K.; Jain, R. Current advances in antifungal targets and drug development. Curr. Med. CChem. 2006, 13, 1321–1335. [CrossRef]

- Enoch, D.A.; Yang, H.; Aliyu, S.H.; Micallef, C. Human Fungal Pathogen Identification; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1508.

- Allen, D.; Wilson, D.; Drew, R.; Perfect, J. Azole Antifungals: 35 Years of Invasive Fungal Infection Management. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2015, 13, 787–798. [CrossRef]

- Ejidike, I. Cu(II) Complexes of 4-[(1E)-N-{2-[(Z)-Benzylidene-amino]ethyl}ethanimidoyl]benzene-1,3-diol Schiff base: Synthesis, spectroscopic, in-vitro antioxidant, antifungal and antibacterial studies. Molecules 2018, 23, 1581. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, N.; Tu, J.; Ji, C.; Han, G.; Sheng, C. Discovery of Simplified Sampangine Derivatives with Potent Antifungal Activities against Cryptococcal Meningitis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019, 5, 1376–1384. [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, M.; Toreyhi, H.; Firoozpour, L.; Akbarzadeh, T.; Amini, M.; Hosseinzadeh, E.; Hashemzadeh, M.; Peyton, L.; Lotfali, E.; Foroumad, A. Design, Synthesis, and In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of Novel Fluconazole-Based Compounds with Promising Antifungal Activities. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 24981–25001. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Han, L.; Huang, X. Potential Targets for the Development of New Antifungal Drugs. J. Antibiot. 2018, 71, 978–991. [CrossRef] 104. Montoya, M.C.; Didone, L.; Heier, R.F.; Meyers, M.J.; Krysan, D.J. Antifungal Phenothiazines: Optimization, Characterization of Mechanism, and Modulation of Neuroreceptor Activity. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 499–507. [CrossRef]

- Montoya, M.C.; Didone, L.; Heier, R.F.; Meyers, M.J.; Krysan, D.J. Antifungal Phenothiazines: Optimization, Characterization of Mechanism, and Modulation of Neuroreceptor Activity. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 499–507. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Lone, S.A.; Gull, P.; Dar, O.A.; Wani, M.Y.; Ahmad, A.; Hashmi, A.A. Efficacy of Novel Schiff base Derivatives as Antifungal Compounds in Combination with Approved Drugs Against Candida Albicans. Med. Chem. 2019, 15, 648–658. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Tan, W.; Zhang, J.; Mi, Y.; Dong, F.; Li, Q.; Guo, Z. Synthesis, Characterization, and Antifungal Activity of Schiff Bases of Inulin Bearing Pyridine ring. Polymers 2019, 11, 371. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.P.; Wang, Z.F.; Huang, X.L.; Tan, M.X.; Shi, B.B.; Liang, H. High in Vitro and in Vivo Tumor-Selective Novel Ruthenium(II) Complexes with 3-(20 -Benzimidazolyl)-7-fluoro-coumarin. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 936–940. [CrossRef]

- Pahontu, E.; Julea, F.; Rosu, T.; Purcarea, V.; Chumakov, Y.; Petrenco, P.; Gulea, A. Antibacterial, antifungal and in vitro antileukaemia activity of metal complexes with thiosemicarbazones. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015, 19, 865–878. [CrossRef]

- Boros, E.; Dyson, P.J.; Gasser, G. Classification of Metal-based Drugs According to Their Mechanisms of Action. Chem 2020, 6, 41–60. [CrossRef]

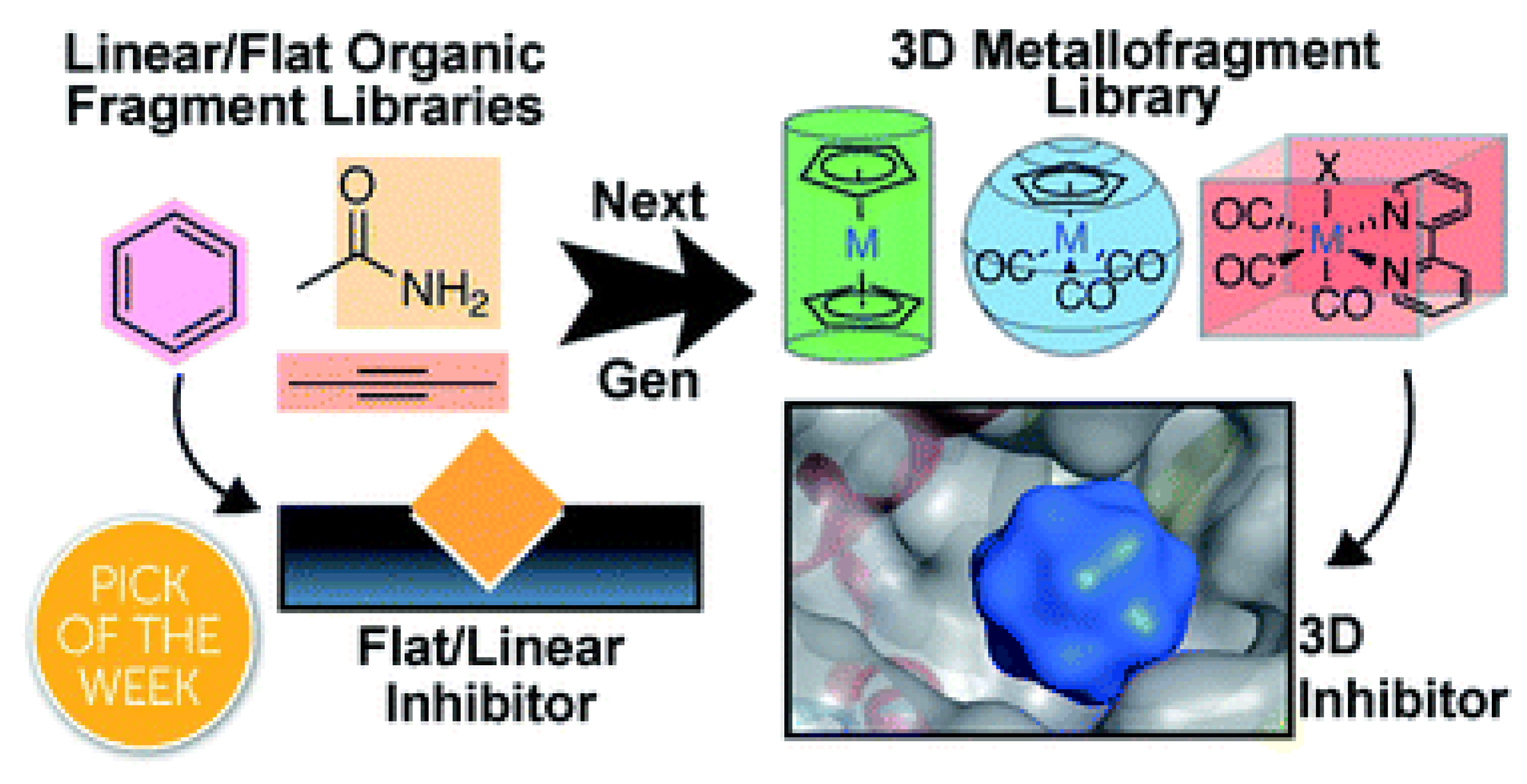

- Morrison, C.N.; Prosser, K.E.; Stokes, R.W.; Cordes, A.; Metzler-Nolte, N.; Cohen, S.M. Expanding medicinal chemistry into 3D space: Metallofragments as 3D scaffolds for fragment-based drug discovery. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 1216–1225. [CrossRef]

- Frei, A.; King, A.P.; Lowe, G.J.; Cain, A.K.; Short, F.L.; Dinh, H.; Elliott, A.G.; Zuegg, J.; Wilson, J.J.; Blaskovich, M.A.T. Nontoxic Cobalt(III) Schiff Base Complexes with Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 2021–2029. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Betts, H.; Keller, S.; Cariou, K.; Gasser, G. Recent developments of metal-based compounds against fungal pathogens. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 10346–10402. [CrossRef]

- Gehad, G.; Mohamed, M.M.; Omar, M.; Yasmin, M. Metal complexes of Tridentate Schiff base: Synthesis, Characterization, Biological Activity and Molecular Docking Studies with COVID-19 Protein Receptor. J. Inorg. Gen Chem. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2021, 647, 2201–2218. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Dief, A.M.; Mohamed, I.M.A. A review on versatile applications of transition metal complexes incorporating Schiff bases. Beni Suef. Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2015, 4, 119–133. [CrossRef]

- Devi, J.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, B.; Asija, S.; Kumar, A. Synthesis, structural analysis, in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial activity and molecular docking studies of transition metal complexes derived from Schiff base ligands of 4-(benzyloxy)-2- hydroxybenzaldehyde. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2022, 48, 1541–1576. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Ahmed, S.S.; Alam, S.M.R. REVIEW: Biomedical applications of Schiff base metal complexes. J. Coord. Chem. 2020, 73, 3109–3149. [CrossRef]

- Borase, J.N.; Mahale, R.G.; Rajput, S.S.; Shirsath, D.S. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of heterocyclic methyl substituted pyridine Schiff base transition metal complexes. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 197. [CrossRef]

- Inan, A.; Ikiz, M.; Tayhan, S.E.; Bilgin, S.; Genç, N.; Sayın, K.; Ceyhan, G.; Kose, M.; Dag, A.; Ispir, E. Antiproliferative, antioxidant, computational and electrochemical studies of new azo-containing Schiff base ruthenium (II) complexes. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 2952–2963. [CrossRef]

- Kizilkaya, H.; Dag, B.; Aral, T.; Genc, N.; Erenler, R. Synthesis, characterization, and antioxidant activity of heterocyclic Schiff bases. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2020, 67, 1696–1701.

- Chi-Ming Che and Fung-Ming Siu. Metal complexes in medicine with a focus on enzyme inhibition. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2010, 14, 255–261. [CrossRef]

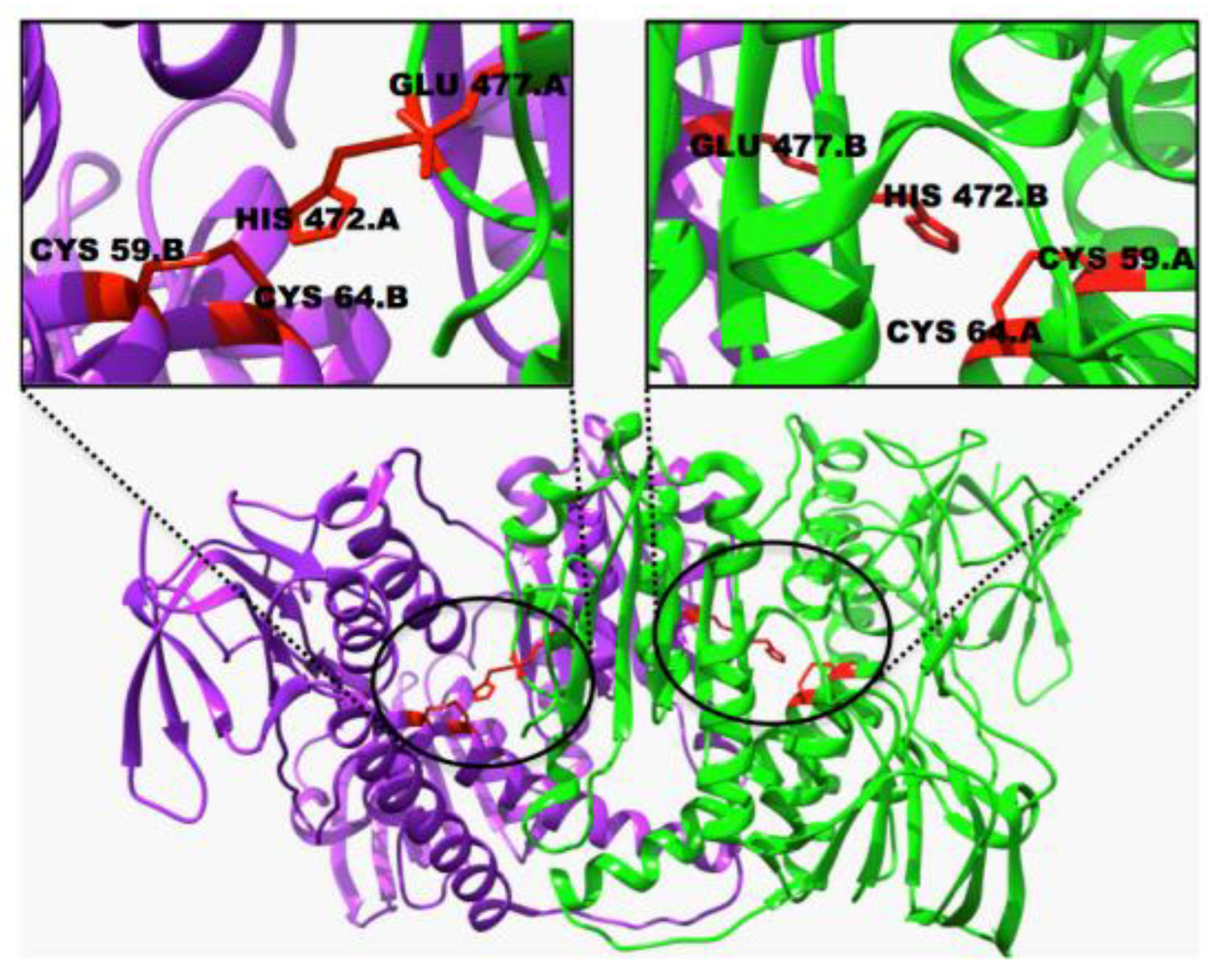

- Angelucci, F.; Sayed, A.A.; Williams, D.L.; Boumis, G.; Brunori, M.; Dimastrogiovanni, D.; Miele, A.E.; Pauly, F.; Bellelli, A. Inhibition of Schistosoma mansoni thioredoxin glutathione reductase by auranofin: structural and kinetic aspects. J Biol Chem 2009, 284:28977-28985. [CrossRef]

- Mirabelli, C.K.; Johnson, R.K.; Sung, C.M.; Faucette, L.; Muirhead, K.; Crooke, S.T. Evaluation of the in vivo antitumor activity and in vitro cytotoxic properties of auranofin, a coordinated gold compound, in murine tumor models. Cancer Res 1985, 45, 32-39.

- Ott, I.; Qian, X.; Xu, Y.; Vlecken, D.H.; Marques, I.J.; Kubutat, D.; Will, J.; Sheldrick, W.S.; Jesse, P.; Prokop, A. et al.: A gold(I) phosphine complex containing a naphthalimide ligand functions as a TrxR inhibiting antiproliferative agent and angiogenesis inhibitor. J Med Chem 2009, 52, 763-770. [CrossRef]

- Milacic, V.; Chen, D.; Ronconi ,L.; Landis-Piwowar, K.R.; Fregona, D.; Dou, Q. P. A novel anticancer gold(III) dithiocarbamate compound inhibits the activity of a purified 20S proteasome and 26S proteasome in human breast cancer cell cultures and xenografts. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 10478-10486. [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; Herold-Mende, C.; Park, J.J.; Lowe, G.; Schirmer, R.H. Human thioredoxin reductase is efficiently inhibited by (2,2’:6’,2’’-terpyridine)platinum(II) complexes. Possible implications for a novel antitumor strategy. J Med Chem 2001, 44, 2784-2792. [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.C.; Ko, T.P.; Su, W.C.; Su, T.L.; Wang, A.H.J. Terpyridine-platinum(II) complexes are effective inhibitors of mammalian topoisomerases and human thioredoxin reductase 1. J Inorg Biochem 2009, 103, 1082-1092. [CrossRef]

- Arnesano, F.; Boccarelli, A.; Cornacchia, D.; Nushi, F.; Sasanelli, R.; Coluccia, M.; Natile, G. Mechanistic insight into the inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases by platinum substrates. J Med Chem 2009, 52(23), 7847-7855. [CrossRef]

- Ang, W.H.; Parker, L.J.; De Luca, A.; Juillerat-Jeanneret, L.; Morton, C.J.; Lo Bello, M.; Parker, M.W.; Dyson, P.J. Rational design of an organometallic glutathione transferase inhibitor. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2009, 48, 3854-3857. [CrossRef]

- Hickey, J.L.; Ruhayel, R.A.; Barnard, P.J.; Baker, M.V.; Berners-Price, S.J.; Filipovska, A. Mitochondria-targeted chemotherapeutics: the rational design of gold(I) N-heterocyclic carbene complexes that are selectively toxic to cancer cells and target protein selenols in preference to thiols. J Am Chem Soc 2008, 130, 12570-12571. [CrossRef]

- Montana, A.M.; Batalla, C. The rational design of anticancer platinum complexes: the importance of the structure–activity relationship. Curr Med Chem 2009, 16:2235-2260. [CrossRef]

- Zoubi, W.A.; Ko, Y.G. Schiff base complexes and their versatile applications as catalysts in oxidation of organic compounds: Part I. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 31, e3574. [CrossRef]

- Balas, M.; KBidi, L.; Launay, F.; Villanneau, R. Chromium-Salophen as a Soluble or Silica-Supported Co-Catalyst for the Fixation of CO2 Onto Styrene Oxide at Low Temperatures. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 765108. [CrossRef]

- North, M.; Quek, S.C.Z.; Pridmore, N.E.; Whitwood, A.C.; Wu, X. Aluminum(salen) Complexes as catalysts for the Kinetic Resolution of Terminal Epoxides via CO2 Coupling. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 3398–3402. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Osma, J.A.; Lamb, K.J.; North, M. Cr(salophen) Complex Catalyzed Cyclic Carbonate Synthesis at Ambient Temperature and Pressure. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5012–5025. [CrossRef]

- Tuna, M.; Tu ˘gba U ˘gur, T. Investigation of The Effects of Diaminopyridine and o-Vanillin Derivative Schiff Base Complexes of Mn(II), Mn(III), Co(II) and Zn(II) Metals on The Oxidative Bleaching Performance of H2O2. SAUJS 2021, 25, 984–994. OI:10.16984/saufenbilder.948657.

- Bulduruna, K.; Özdemir, M. Ruthenium(II) complexes with pyridine-based Schiff base ligands: Synthesis, structural characterization and catalytic hydrogenation of ketones. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1202, 127266. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.; White, J.D. Asymmetric Catalysis Using Chiral Salen–Metal Complexes: Recent Advances. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9381–9426. [CrossRef]

- Cozzi, P.G. Metal-salen Schiff base complexes in catalysis: Practical aspects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004, 33, 410–421. [CrossRef]

- Racles, C.; Zaltariov, M.F.; Iacob, M.; Silion, M.; Avadanei, M.; Bargan, A. Siloxane-based metal–organic frameworks with re markable catalytic activity in mild environmental photodegradation of azo dyes. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 205, 78–92. [CrossRef]

- Maharana, T.; Nath, N.; Pradhan, H.C.; Mantri, S.; Routaray, A.; Sutar, A.K. Polymer-supported first-row transition metal schiff base complexes: Efficient catalysts for epoxidation of alkenes. React. Funct. Polym. 2022, 171, 105142. [CrossRef]

- Salman, A. T.; Ismail, A. H.; Rheima, A. M.; Abd, A. N.; Habubi N. F.; Abbas Z. S. Nano-Synthesis, characterization and spectroscopic Studies of chromium (III) complex derived from new quinoline-2-one for solar cell fabrication. The International Conference of Chemistry 2020 Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1853 (2021) 012021 IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

| technique | donor atom | metal | structure | references |

| 13C CPMAS NMR, IR and FAB-MS and theoretical DFT studies | N3^S4-bridging coordination | Cu(I) and Ni(II) | dimeric structures | [1] |

| 13C CPMAS NMR and theoretical DFT studies | N3^S2-bridging coordination for L1 with Cu(I); monodentate coordination (N3- and S2- ) of two non-equivalent ligand molecules for L2 with Cu(I); N3^S4- bridging way for Ni(II) |

Cu(I) and Ni(II) | dimeric structure for Cu(I) with L1; square planar for Ni(II) with L1 and L2 |

[2] |

| IR and 13C CPMAS NMR and theoretical DFT studies | N and S | Pt(II) | square planar | [3] |

|

13C-NMR-CP-MAS, EPR, IR and quantum-chemical (DFT/B3LYP-6-31G (d,p)) methods |

N for Cu(II) and N3 and S2 for Ni(II) | Cu(II) and Ni(II) | distorted tetrahedral for Cu(II) and square planar for Ni(II) | [4] |

| 13C CPMAS NMR and theoretical DFT studies, X-ray | O, Cl | Al(III) | six-membered chelate rings | [5] |

| melting point analysis, MP-AES for Cu and Pd, UV-Vis, IR, ATR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR and Raman, Solid-state NMR spectroscopy | O,S for L1 and S for L2 with Cu(II); N, S, O with Pd(II) |

Cu(II) and Pd(II) | tetrahedral for Cu(II) with L1 and octahedral for L2; chelate for Pd(II) with L1 and L2 |

[6] |

| MP-AES for Cu and Au, ICP-OES for S, ATR, solution and solid-state NMR, and Raman spectroscopy | N,S for Au(III) and O,S for Cu(II) | Au(III) and Cu(II) | chelate structure |

[7] |

| UV-Vis, IR, ATR, 1H NMR, HSQC, and Raman, solid-state NMR spectroscopy | O, S | Au(III) | tetrahedral |

[8] |

| IR, FAB-MS, XPS, solid-state NMR spectroscopy and theoretical DFT studies | N, S | Pt(II) | dimer, chelate structure | [9] |

| X-ray | O, N | Ag(I) | dinuclear complex, chelate structure | [10] |

| X-ray, ESR, MALDI mass-spectrometry, NMR spectroscopy | P, O, P | Ru(II) and Ru(III) | chelate structure | [11] |

| X-ray and 1H-, 13C-NMR, IR and UV-Vis spectroscopy and elemental analysis and theoretical DFT studies | O, N | Cu(II), Fe(II) and Zn(II) | chelate structure | [12] |

| elemental analysis, FAAS, FT-IR, MS, TG methods and X-ray for C3 and C4 | N, Cl | Zn(II) | tetrahedral geometry, dinuclear coordination compounds | [102] |

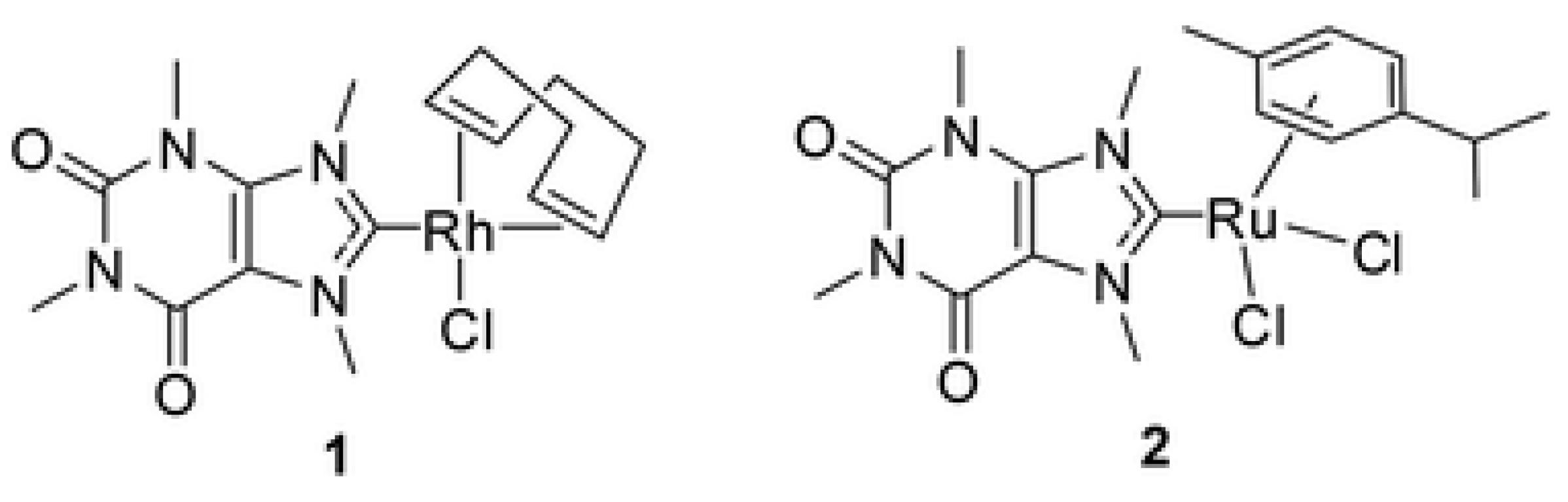

| Elemental analysis, NMR and ESI-MS | C, Cl | Rh(I) and Ru(II) | Tetrahedral or square planar | [103] |

| X-ray and 1H-, 13C-NMR, IR and UV-Vis spectroscopy and elemental analysis | C, Cl | Au(III) | square planar | [104] |

| NMR and mass spectroscopy, X-ray | C, Cl | Au(I) and Ag(I) | Liner | [105] |

|

Metal complexes |

Molecular formula | Proposed mechanism of action | Target enzymes/cell lines/ therapeutic indications | IC50 range (μM) | Reference |

| Carbene–metal complexes and related ligands | |||||

| Novel gold(I) and gold(III) NHC complexes | C52H44Au2N12P2F12 | Induction of apoptosis Inhibition of TrxR Induction of ROS |

TrxR A549, HCT116, HepG2, MCF7 Chemotherapy of solid tumors |

C52H44Au2N12P2F12 5.2±1.5 (A549) 3.6±4.1 HCT-116) 3.7±2.3 (HepG2) 4.7±0.8 (MCF7) |

[104] |

| C26H24AuCl2OF6N6P | C26H24AuCl2OF6N6P 5.2±3.0 (A549) 5.9±3.6 (HCT-116) 5.1±3.8 (HepG2) 6.2±1.4 (MCF7) |

[104] | |||

| Caffeine-based gold(I) NHCs | [Au(Caffeine-2-yielding)2][BF4 ] | Inhibition of protein PARP-I | DNA A2780, A2780R, SKO3, A549 HK-293T |

0.54–28.4 (A2780) 17.1–49 (A2780/R) 0.75–62.7 (SKO3) 5.9–90.0 (A549) 0.20–84 (HK-293T) | [113] |

| Ester- and amidefunctionalized imidazole of NHC complexes | {[ImA]AgCl} {[ImA]AuCl} {[ImB]2AgCl} {[ImB]AuCl} HmACl = [1,3-bis (2-ethoxy-2-oxoethyl)-1Himidazol-3-ium chloride] HmBCl={1,3-bis[2(diethylamino)-2-oxoethyl]-1H-imidazol-3-ium chloride} |

Inhibition of tyrosine by gold(I) NHC ligands, thereby targeting TrxR CuNHC cell cycle arrest progression in G phase Anticancer activity of Ag1 NHC is based on highly lipophilic aromaticsubstituted carbenes |

TrxR A375, A549, HCT-15 and MCF7 Human colon adenocarcinoma Leukemia and breast cancer |

{[ImA]AgCl} 24.65 (A375) 22.14 (A549) 20.32 (HCT-15) 21.14 (MCF7) {[ImA]AuCl} 44.64 (A375) 42.37 (A549) 41.33 (HCT-15) 38.53 (MCF7) {[ImB]2AgCl} 24.46 (A375) 16.23 (A549) 14.11 (HCT-15) 15.31 (MCF7) |

[105] |

| Novel Ru(II) NHCs83 | η6-p-cymene)2Ru2(Cl2)2]NHC | Mimic iron Interact with plasmidic DNA |

DNA as target Caki-1 and MCF7 Chemotherapy of solid tumor |

13–500 (Caki-1) 2.4–500 (MCF7) | [114,115] |

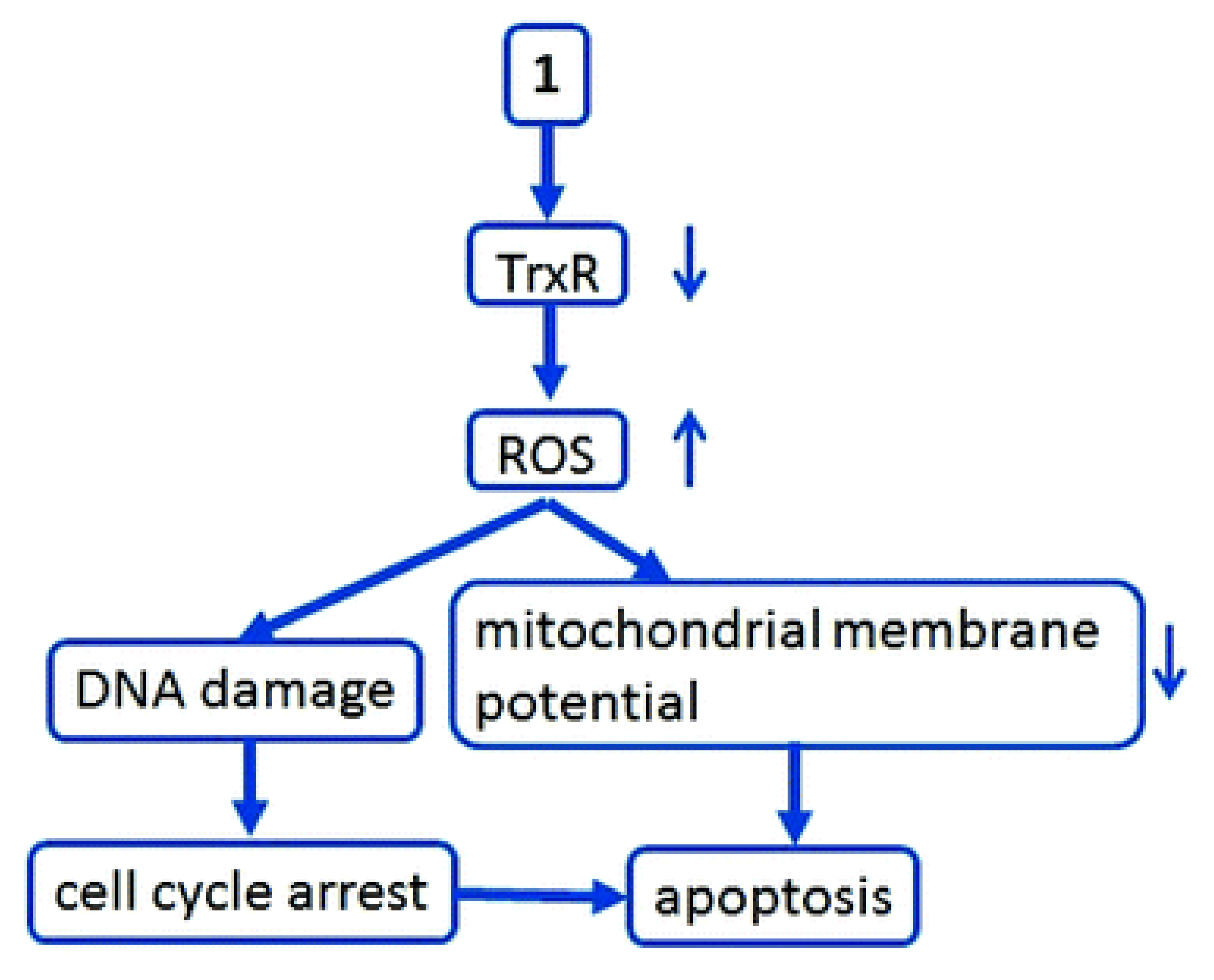

| Caffeine-derived rhodium(I) NHC complexes | [Rh(I)Cl(COD)(NHC)] complexes | Inhibition of TrxR Increase in ROS formation DNA damage Cell cycle arrest Decrease in mitochondria membrane potentia |

TrXR MCF7, HepG2 MDA-MB-231, HCT-116, LNCaP, Panc-I and JoPaca-I Chemotherapy of solid tumor85 |

84 (HepG2) 20 (HCF-7) 23 (MDA-MB-231) 35 (JoPaca-I) 49 (Panc-I) 80 (LNCaP) 9.0 (HCT-116 |

[103] |

| NHC–amine Pt(II) complexes | NHC (PtX2)–amine complexes | Nuclear DNA platination | Target DNA KB3-1, SK-O3, OCAR-8, M-4-11, A2780 and A2780/ DPP Chemotherapy of solid and non-solid tumors |

2.5 (KB3-1) 4.33 (SK-O3) 1.84 (OCAR-8) 0.60 (M-4-11) 4.00 (A2780) 8.5 (A2780/DPP) |

[116] |

| 2-Hydroxy-3-[(hydroxyimino)-4- oxopentan-2-ylidene] benzohydrazide derivatives | [(HL)Cu(OAc)(H2O)2]⋅H2OC14H21N3O9Cu | Bind to DNA | Target DNA HepG2 Chemotherapy of solid tumors |

2.24–6.49 (HepG2) | [117] |

| Molybdenum(II) allyl dicarbonate complexes | [Mo(allyl)(CO)2 (N-N)(py)]PF6 | DNA fragmentation Induction of apoptosis |

Target DNA NALM-6, MCF7 and HT-29 Chemotherapy of solid and non-solid tumors |

1.8–13 (NALM-6) 2.1–32 (MCF7) 1.8–32 (HT-29) | [118] |

| Metal-arene complexes and other ligands | |||||

| Ru(II)–arene complex | [(η6-arene)Ru(II)(en)Cl]+ | DNA damage Cell cycle arrest Induction of apoptosis |

Target DNA AH54 and AH63 Chemotherapy of colorectal cancer |

C15H18ClF6N2PRu 16.6 (AH54) C16H2OClF6N2PRu 10.9 (AH63) |

[119] |

| Novel ruthenium– arene pyridinyl methylene complexes | [(η6-p-cymene)RuCl(pyridinylmethylene)] | DNA binding | Target DNA MCF7 and HeLa Chemotherapy of solid tumor |

07.76–25.42 (MCF7) 07.10–29.22 (HeLa) | [120] |

| Multi-targeted organometallic Ru(II)–arene | [(η6-p-cymene)RuCl2]2-PARP and PARP-I inhibitors | DNA binding PARP-I inhibition Transcription inhibition |

Target DNA A549, A2780, HCT-116, HCC1937 and MRC-5 Chemotherapy of solid tumors |

85.1–500 (A549) 38.8–500 (A2780) 46.0–500 (HCT-116) 93.3–500 HCC1937) 143–500 (MRC-5) | [121] |

| Ru(II)–arene complexes with 2-aryldiazole ligands | [(η6-arene)RuX(k2 -N,N-L)]Y | DNA binding Inhibition of CDK1 |

Target DNA A2780, A2780cis, MCF7 and MRC-5 Chemotherapy of solid tumors |

11–300 (A2780) 11–34 (A2780cis) 26–300 (MCF7) 25–224 (MRC-5) | [122] |

| Osmiun(II)–arene carbohydrate base anticancer compound | Osmium(II)-bis [dichloride(η6-p-cymene)] | DNA binding | Target DNA CH1, S480 and A549 |

50–746 (CHI) 215–640 (S480) 640 (A549) |

[123] |

| Ru(II)–arene complexes with carbosilane metallodendrimers | Gn-[NH2Ru(η6-p-cymene)Cl2]m | Interaction with DNA Interaction with HSA94 Inhibition of cathepsin B |

Target DNA HeLa, MCF7, HT-29 MDAMB-231 and HK-239T Chemotherapy of solid and non-solid tumors |

6.3–89 (HeLa) 2.5–56.0 (MCF7) 3.3–41.7 (HT-29) 4–74 (MDA-MB-231) 5.0–51.9 (HK-239T) | [106] |

| Ru(II) complexes with aroylhydrazone ligand | [Ru(η6-C6H6)Cl(L)] | Induction of apoptosis Fragmentation of DNA |

Target DNA MCF7, HeLa, NH-3T3 Chemotherapy of solid tumor |

10.9–15.8 (MCF7)95 34.3–48.7 (HeLa) 152.6–192 (NH-3T3) | [124] |

| Cyclopentadienyl complexes and other ligands | |||||

| Iridium(III) complexes with 2-phenylpyridine ligand | [(η5-Cp*)r(2-(R′-phenyl)-Rpyridine)Cl] | Interaction with DNA nucleobases Catalysis of NADH oxidation |

Target DNA A2780, HCT-116, MCF7 and A549 Chemotherapy of solid tumor |

1.18–60 (A2780) 3.7–57.3 (HCT-116) 4.8–28.6 (MCF7) 2.1–56.67 (A549) | [125] |

| New iron(II) cyclopentadienyl derivative complexes | [Fe(η5-C5H5)(dppe)L][X] | Interaction with DNA Induction of apoptosis |

Target DNA HL-60 Chemotherapy of non-solid tumors |

0.67–5.89 (HL-60) | [126] |

| Ru(II) cyclopentadienyl complexes with carbohydrate ligand | [Ru(η5-C5H5)(PP)(L)][X] | Induction of apoptosis Activation of caspase-3 and -7 activity |

HCT116CC, HeLa Chemotherapy of solid tumors |

0.45 (HCT116CC) 3.58 (HeLa) | [127] |

| Ru(II) cyclopentadienyl complexes with phosphane co-ligand | [Ru(η5-C5H5)(PP)(L)][X] | Induction of apoptosis | HeLa Chemotherapy of solid tumo |

2.63 (HeLa) | [128] |

| Organoiridium cyclopentadienyl complexes | [(η5-Cpx)r(L^L′)Z] | Intercalation of DNA Coordination with DNA guanine |

HeLa Chemotherapy of solid tumor |

0.23 (HeLa) | [129] |

| Abbreviations: IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; NHC, N-heterocyclic carbene; TrxR, thioredoxin reductase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PARP-1, Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1; CDK1, cyclin-dependent kinase 1; HSA, human serum albumin; ADP, adenosine diphosphate. | |||||

| Drug name | Developers | Phase of clinical trial | Indications | Reference |

| Picoplatin (JM473) | Pionard | Phase I | Treatment of colorectal cancer in combination with 5-FU and leucovorin | [129] |

| Lipoplatin™ (Nanoplatin™, Oncoplatin) | Regulon | Phase II and phase III clinical in different cancer cells | Treatment of locally advanced gastric cancer/ squamous cell carcinoma of head and nec | [129] |

| ProLindac™ (AP5046) | Access Pharm | Phase I, II ad III trials | Advanced ovarian cancer68 and head and neck cancers | [129] |

| Satraplatin (JM216) | Spectrum Pharm and Agennix AG | Phase I, II ad III trials | Treatment of colorectal cancer in combination with 5-FU and leucovorin, treatment of prostate cancer in combination with docetaxel and treatment of a patient with progressive or relapse NSCLC68 | [129] |

| NAMIA-A | – | Phase I | Metastatic tumor (lung, colorecta, melanoma, ovaria and pancreatic) | [130] |

| KP1019 | – | Phase II | Advanced colorecta cancer | [130] |

|

64Cu-ATSM |

– |

Phase II |

PET/CT monitoring therapeutic progress in patient with cervica1 |

[131] |

| Ligand | Pa | Pi | Cell-Line Name | Tissue | Tumor Type |

| L3 | 0.587 | 0.029 | Oligodendroglioma | Brain | Glioma |

| L3 | 0.538 | 0.010 | Colon adenocarcinoma | Colon | Adenocarcinoma |

| L3 | 0.490 | 0.022 | Non-small-cell lung carcinoma | Lung | Carcinoma |

| L3 | 0.475 | 0.009 | Pancreatic carcinoma | Pancreas | Carcinoma |

| L3 | 0.439 | 0.043 | Pancreatic carcinoma | Pancreas | Carcinoma |

| L4 | 0.559 | 0.006 | Pancreatic carcinoma | Pancreas | Carcinoma |

| L4 | 0.554 | 0.009 | Colon adenocarcinoma | Colon | Adenocarcinoma |

| L4 | 0.415 | 0.038 | Cervical adenocarcinoma | Cervix | Adenocarcinoma |

| L4 | 0.426 | 0.099 | Oligodendroglioma | Brain | Glioma |

| Complex | T98G | SK-N-AS | A549 | CCD-1059-Sk |

| L1 | 41.25 ± 2.30 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| C1 |

32.22 ± 0.92 | 35.59 ± 1.03 | 33.51 ± 1.29 | 18.42 ± 0.37 |

| L2 |

34.98 ± 1.44 | 81.35 ± 3.31 | 43.08 ± 2.17 | >100 |

| C2 |

24.29 ± 0.11 | 33.72 ± 0.39 | 34.44 ± 0.75 | 27.27 ± 1.05 |

| L3 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| C3 |

46.54 ± 1.86 | 41.60 ± 1.93 | 41.34 ± 2.17 | 30.84 ± 1.11 |

| L4 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| C4 |

30.05 ± 1.81 | 36.17 ± 0.44 | 35.01 ± 0.86 | 33.62 ±0.85 |

| Etoposide |

>100 | 67.83 ± 2.03 | >100 | >100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).