1. Introduction

In the early 1900s, Julius Bernstein focused on the membrane potential and the action potential [

1]. His hypothesis (BH) proposed that the high intracellular concentration of potassium ions drives the membrane potential by diffusing outward, resulting in a potential difference linked to the disparity in potassium levels inside and outside the cell. During this period, Walther Nernst was formulating a significant electrochemical equation [

2], which similarly hinged on concentration differences between two "cells".

We begin by comparing diffusion with the Nernst equation, initially in the context of chemistry and then in biology, in an effort to emphasize both similarities and distinctions.

2. Material

2.1. Notion of Entropy

Thermodynamic entropy is a crucial, nonconserved state function in both physics and chemistry. The concept of entropy emerged historically to explain why certain processes, allowed by conservation laws, occur spontaneously, while their reverse processes, although also permitted by these laws, do not occur; systems naturally evolve towards higher entropy states. In isolated systems, the entropy never decreases. This idea has several key scientific implications: first, it rules out the possibility of creating "perpetual motion" machines; second, it suggests that the direction of entropy aligns with the forward flow of time. An increase in total entropy within a system and its environment is associated with irreversible changes, as some energy is lost as waste heat, restricting the system’s ability to perform work [

3].

Before exploring the dual applications of this equation, it is wise to revisit some theoretical concepts of diffusion used within the realms of chemistry and biology.

2.2. Diffusion in Chemistry

In chemistry, molecular diffusion is a passive process that occurs without the aid of external energy, resulting in an even distribution of molecules in a system. This distribution is termed entropic and is deemed irreversible. The primary catalyst for diffusion is the thermal movement of molecules, referred to as Brownian motion. In addition, influenced by the concentration gradients in the system, diffusion slows as these gradients equalize. Molecules move from regions of higher concentration to regions of lower concentration. Molecular diffusion obeys Fick’s first law [

4] (Eq.

1).

The diffusion is directional, proportional to the concentration gradient (Eq.

2)

, and also the inverse of the size / mass of the molecule.

Therefore, if the diffusing molecules preexist within the system, both the electroneutrality and the chemical composition stay the same. However, in systems that feature multiple compartments, the chemical makeup can be modified when a product diffuses into a compartment or area where it was not originally found.

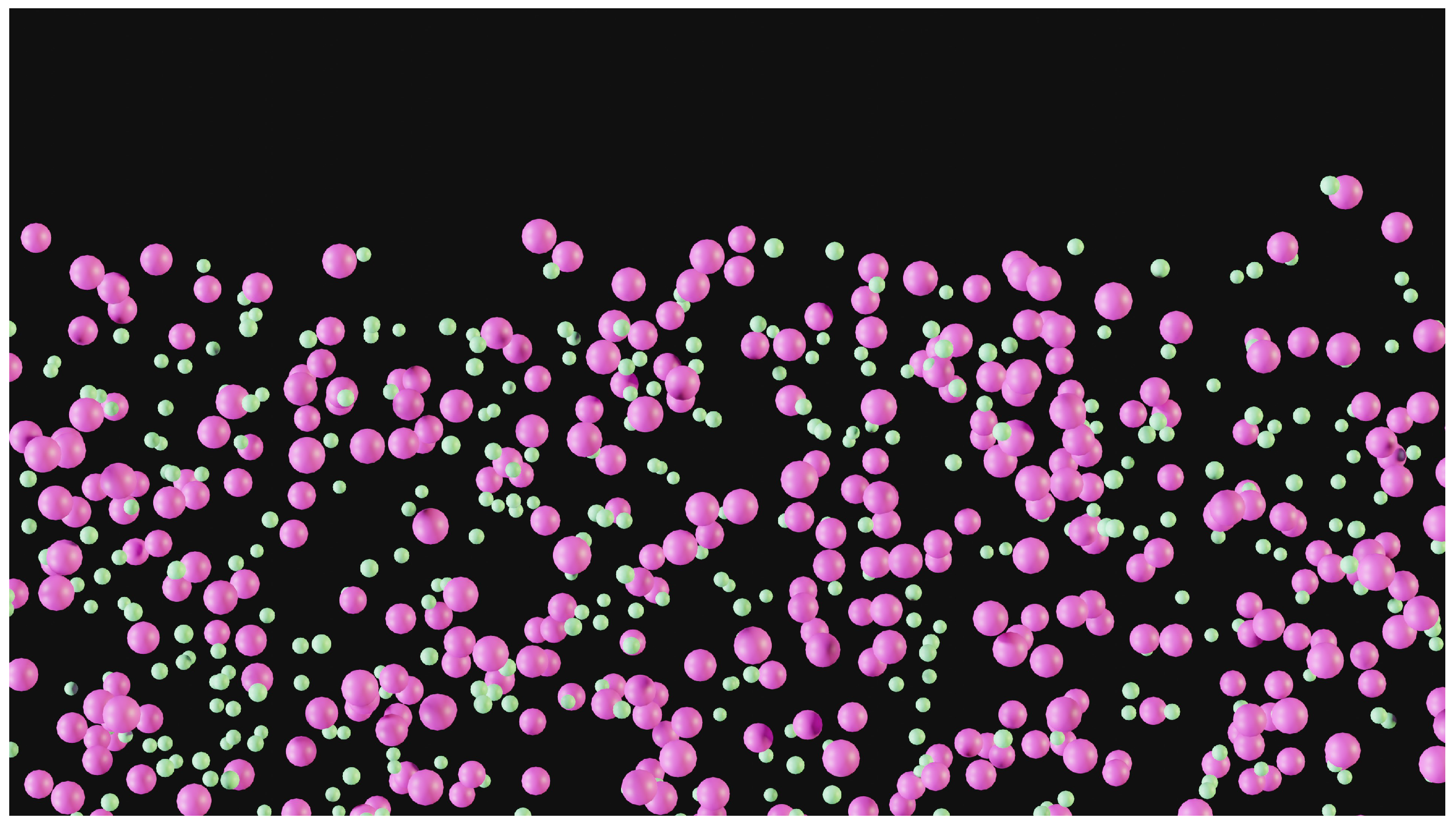

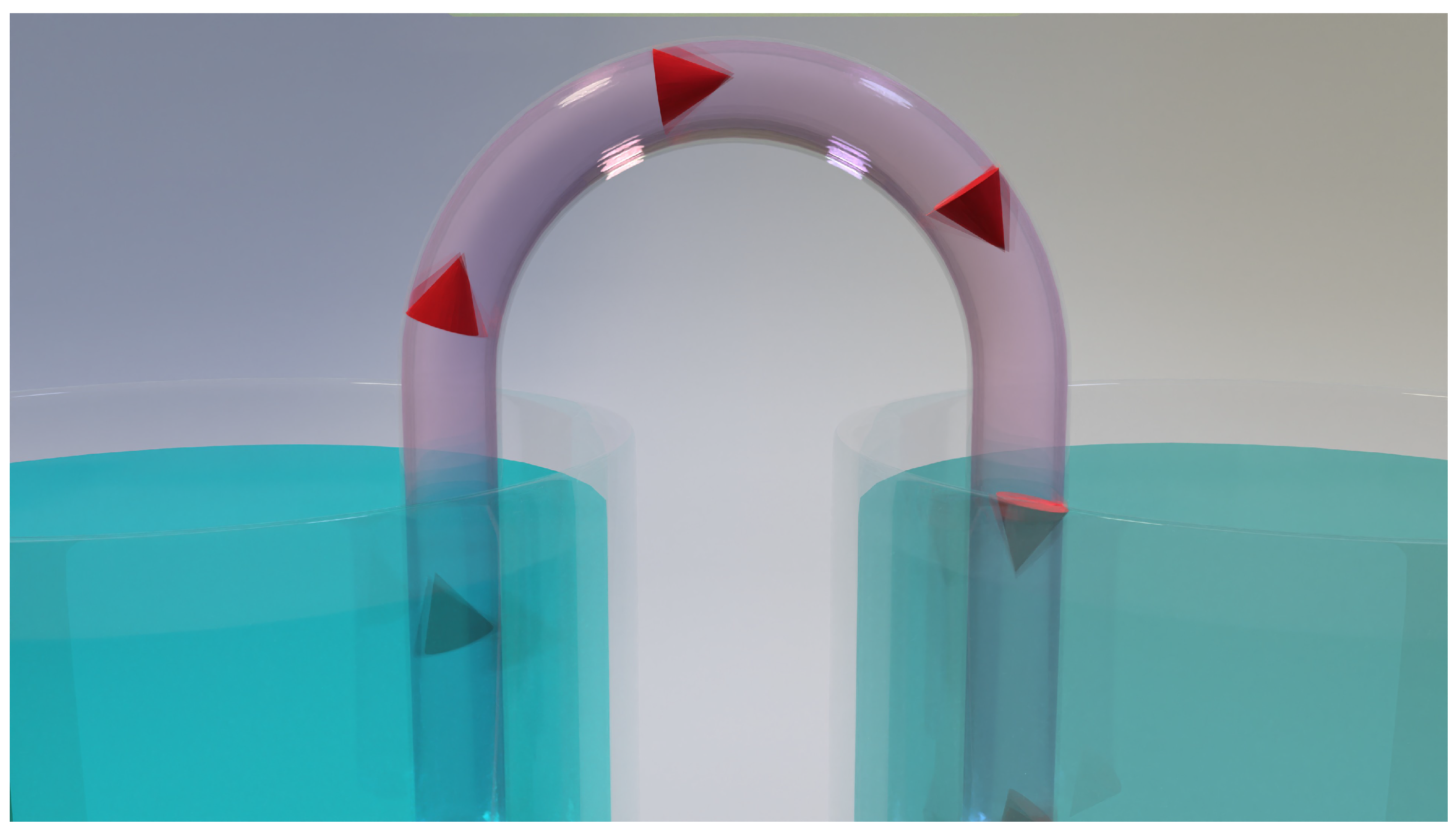

Diffusion can occur with different types of neutral or uncharged molecules, as well as with electrolytes made up of ions, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Electrolytes are formed by positive ions and an equal number of negative ions, which disperse when diluted. Water molecules interpose between these ions of opposite charges. For these ions, electroneutrality is typically observed and preserved because the velocities of positive and negative charges tend to be similar.

However, when a salt contains ions with significantly different diffusion rates, the ion with the highest diffusivity will diffuse more rapidly than the other [

5], although this diffusion is restricted by the formation of a local electric field. At the microscopic level, electroneutrality may be slightly disrupted; hydration diminishes and weakens the extent of this disturbance. Colloids uniquely form systems that maintain macroscopic electroneutrality, but can exhibit microscopically electrical irregularities [

6].

2.2.1. Facilitated Diffusion

Diffusion is considered improved when a particular molecule has a favorable edge in its spread over others. As an illustration, a material might be employed to obstruct the diffusion of particles that are larger in size than those intended to be prioritized.

Here, it acts as a sort of filtration process.

In the field of biology, the cell membrane may function as a barrier to ions. The movement of these charged particles is made easier by traveling through ion channels within the membrane. This mechanism typically favors the transport of specific ions over others.

Does it still qualify as diffusion if the solution components are divided? What happens to the products that do not undergo diffusion? For instance, if water molecules are left behind in this process, does this lead to a localized reduction in the concentration of the diffused product?

2.2.2. Mobility of Ions Under an Electric Field

Thermal agitation allows the ions to diffuse similarly to other molecules. However, the presence of an electric field alters this ionic motion. Specifically, positive ions are drawn to the negative pole of the field, whereas negative ions are drawn to its positive pole [

7]. The electric field can have various origins. In electrochemistry, this attraction is driven by an electromotive force from an energy source, which can be external or internal, yet it consistently surpasses the diffusion power.

The Ions Move in Correspondence with Their Charge, Always Towards the Electrodes

2.3. Diffusion in Biology

The traditional concept of molecular diffusion has been expanded and refined within biology to clarify how molecules move across cell membranes, bridging the internal and external environments of the cell. This movement is influenced by what is termed a concentration gradient, which is the variation in concentration between the cell’s exterior and interior. Within a dual-compartment setup, completing the diffusion process can result in changes to the chemical composition of one or both compartments, although these changes should not disturb electroneutrality unless entropy is overridden or energy is introduced.

Thus, from a theoretical standpoint, diffusion, a passive mechanism even within biological contexts, is largely restricted to alterations in electrolyte concentration or dilution. Can we still refer to diffusion when a substance within a compartment can be dissociated into its positive and negative components? The foundational diffusion theory does not cover this scenario, and it appears that the expansion proposed by biology is lacking in scientific precision.

2.4. The Nernst Equation in Chemistry

During Bernstein’s era, electrochemistry was still in its early stages. Nernst had yet to introduce his findings on the equation that has since been experimentally validated numerous times. It is likely that Bernstein believed that the Nernst equation could provide an answer to his question about membrane potential. An appropriate example of a potential mistake in the realm of biology is undoubtedly the concentration cell [

8].

It is important to recognize that the labels ’cell’ and ’concentration’ are generic terms shared by both chemistry and biology.

This might imply that their theories and applications are identical in both fields. To delve into this further, consider their similarities: In each situation, there are two compartments:

two chemical containers, or half-cells in chemistry.

Two compartments (intracellular and extracellular) for the cell model in biology.

In both scenarios, the reaction is fundamentally driven by a concentration gradient. However, beyond this shared aspect, notable differences emerge. To grasp this concept, we must comprehend the function of concentration cells and their opposition to biological systems.

2.4.1. Set Up for a Concentration Cell

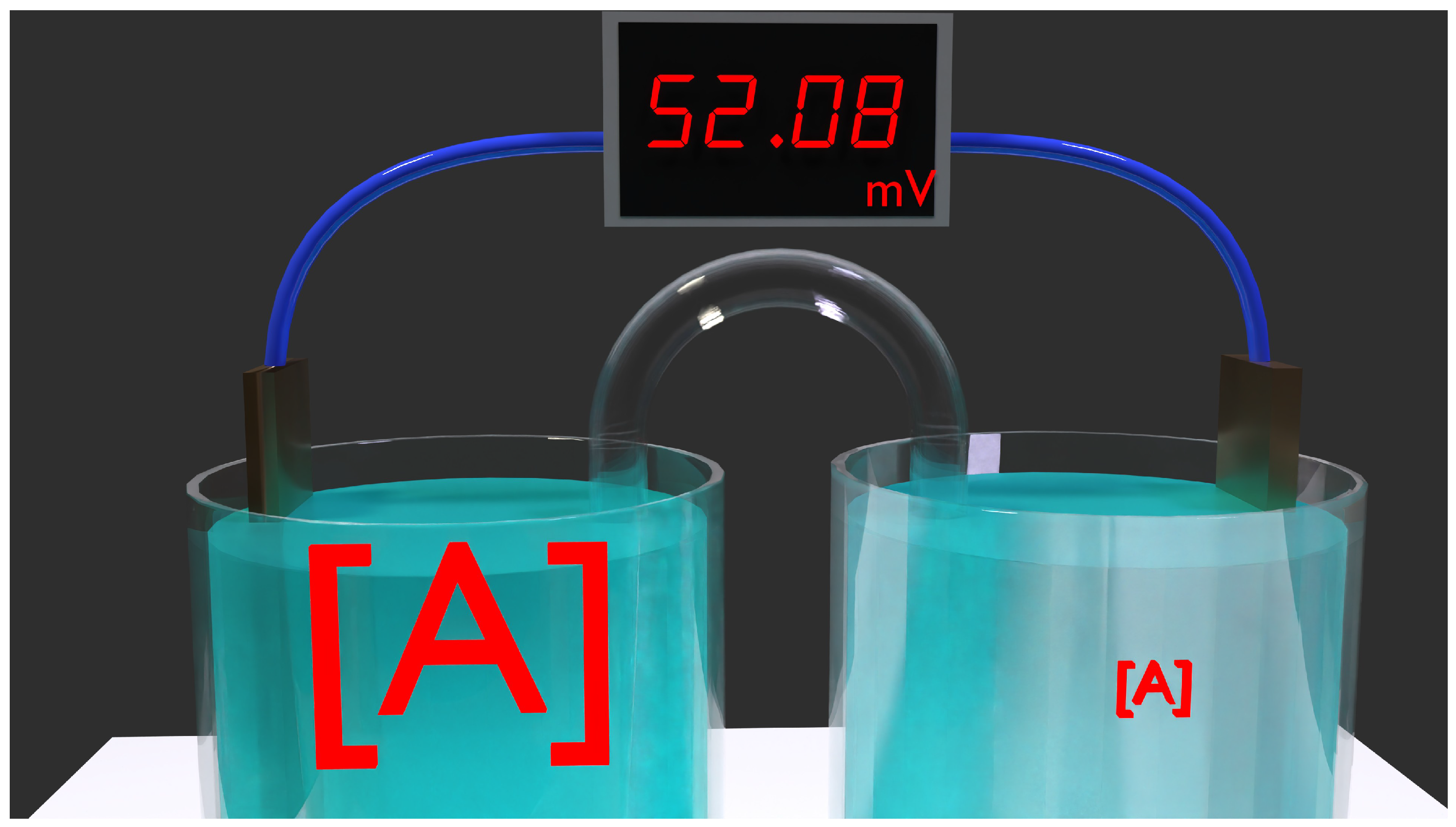

The experimental setup is described in

Figure 2:

There are two containers connected by two circuits; the first, an electrical circuit, is located outside the unit. The second is a water circuit (saline bridge) that connects the containers via an electrolyte that does not influence the chemical reactions occurring within the containers.

Each half-cell has the same volume and type of electrolyte but with varying concentration levels. The solution on the left is more concentrated than the one on the right. When the electrical circuit is connected, chemical reactions occur in both half-cells, specifically RedOx (oxidation reduction) reactions. In the left compartment, which contains the highest concentration of solution, a copper ion (

) acquires two electrons provided by the circuit to the electrode submerged in this solution.

Within the right compartment, containing the solution of the lowest concentration, a copper ion is introduced into the liquid. This ion supplies two electrons to the electrical circuit via the electrode immersed in this solution.

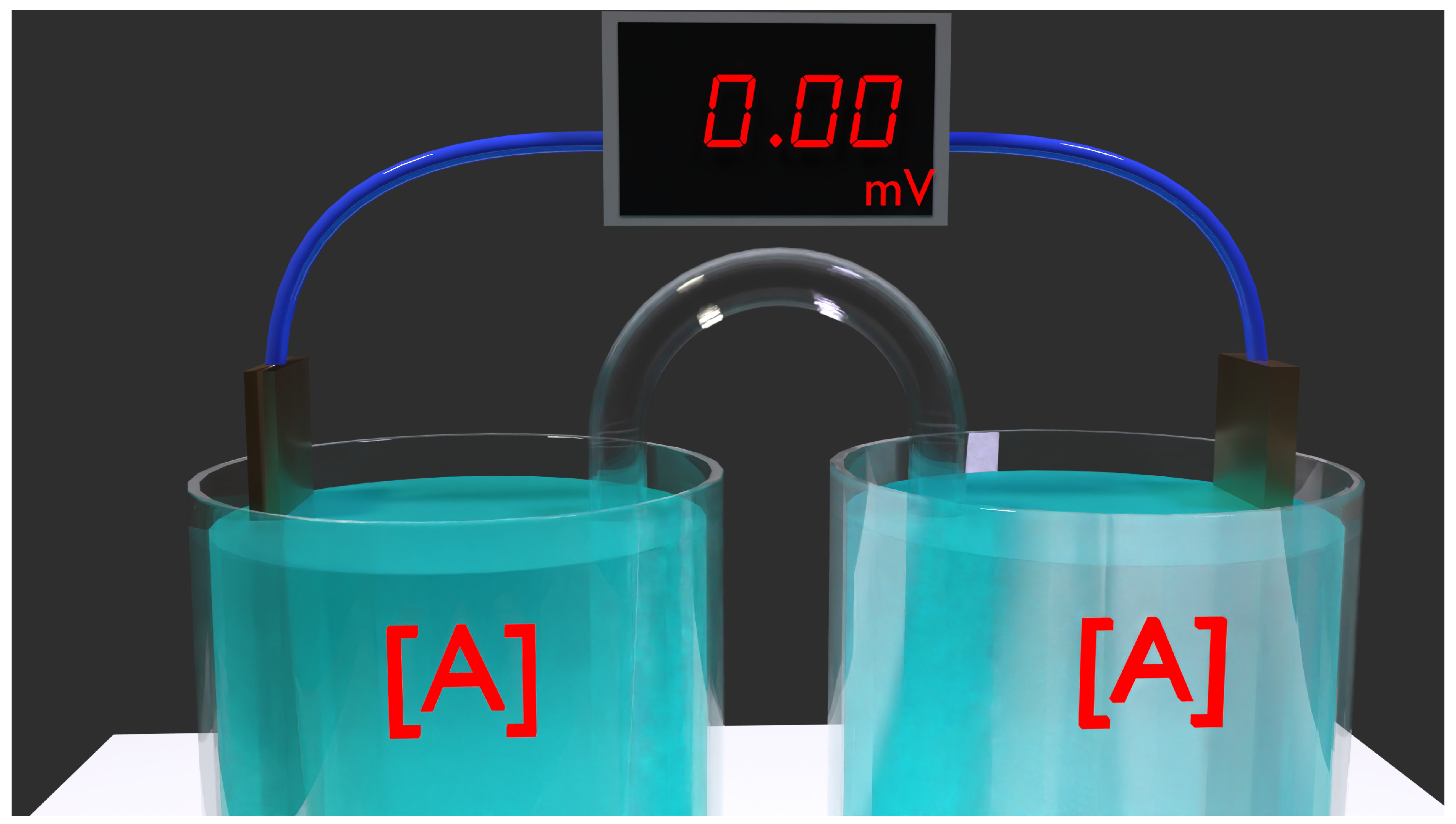

Electrons travel along the electrodes exclusively outside of the device. During the course of the experiment, the voltage reading on the digital voltmeter will gradually decrease to zero. Meanwhile, the concentrations will become stable and reach equilibrium as in

Figure 3.

These two chemical reactions consistently cause a disturbance of electroneutrality in each compartment. On the left, a ion is transformed into a metallic atom that becomes part of the electrode. In contrast, on the right, a ion is released from the electrode into the solution. If these reactions continued without control, the left compartment would gradually become more negative, whereas the right compartment would progressively gain a positive charge. This situation arises because of the role of the salt bridge: when a positive ion is depleted on the left side, the bridge compensates for this by delivering two positive ions (such as ions, as KCl is often used for the salt bridge). This means that two ions are added to the left to balance the reaction. Likewise, two ions are released on the right.

It should be noted that ions do not move from the region of higher concentration to the one of lower concentration through the bridge. Even if a simple tube replaced the bridge, ions would still come from the compartment with lower concentration.

Electroneutrality is thus always preserved.

The beauty of this process implies that all reactions take place within the beakers, while the external circuit primarily functions to monitor the chemical activities. The electrical circuit is not merely an element but essential for the experiment’s success.

The procedure is more complex than it seems: the ions at one electrode receive electrons, transform into metals, and decrease in concentration. In the opposite container, the metal transitions into ionic and liquid phases, sending electrons through the circuit to activate the other side.

The reaction stops when the concentration equilibrium and electron flow are disrupted, leading to weakening and eventual disappearance of the electromotive force. Notably, the ions responsible for the potential difference do not cross the salt bridge.

2.4.2. Experimental Constraints

To ensure that the system functions effectively, all components must be properly positioned and an electrical link must be established between the two compartments. Similarly, a salt bridge and metal electrodes are necessary.

-

What happens if the electrical circuit is cut or removed?

When an open circuit is introduced, the transfer of electrons between the two compartments halts. Although each electrode retains its potential (which cannot be directly measured), the electric field around each electrode prevents the oxidation-reduction reactions from taking place.

-

What happens if the electrodes are missing?

In the absence of electrodes, no chemical reactions take place, leading to no electron production. As a result, the system remains inactive and the electrolytes remain unchanged.

3. Discussion

3.1. Nernst Process in Biology

It is evident that the theoretical framework employed in biology diverges significantly from that in chemistry. In the biological context, the Nernst equation seems pertinent for simulating ion diffusion across compartments with differing concentrations. However, the diffusion model presented in the hypothesis is subject to many criticisms. The absence of metal electrodes and redox reactions undermines its applicability. Furthermore, no electrical circuit facilitates the movement of electrons. Thus, the electrochemical model is simplified by reductionism to encompass two compartments divided by a cell membrane, interconnected through "salt bridges," which in this scenario are ion channels.

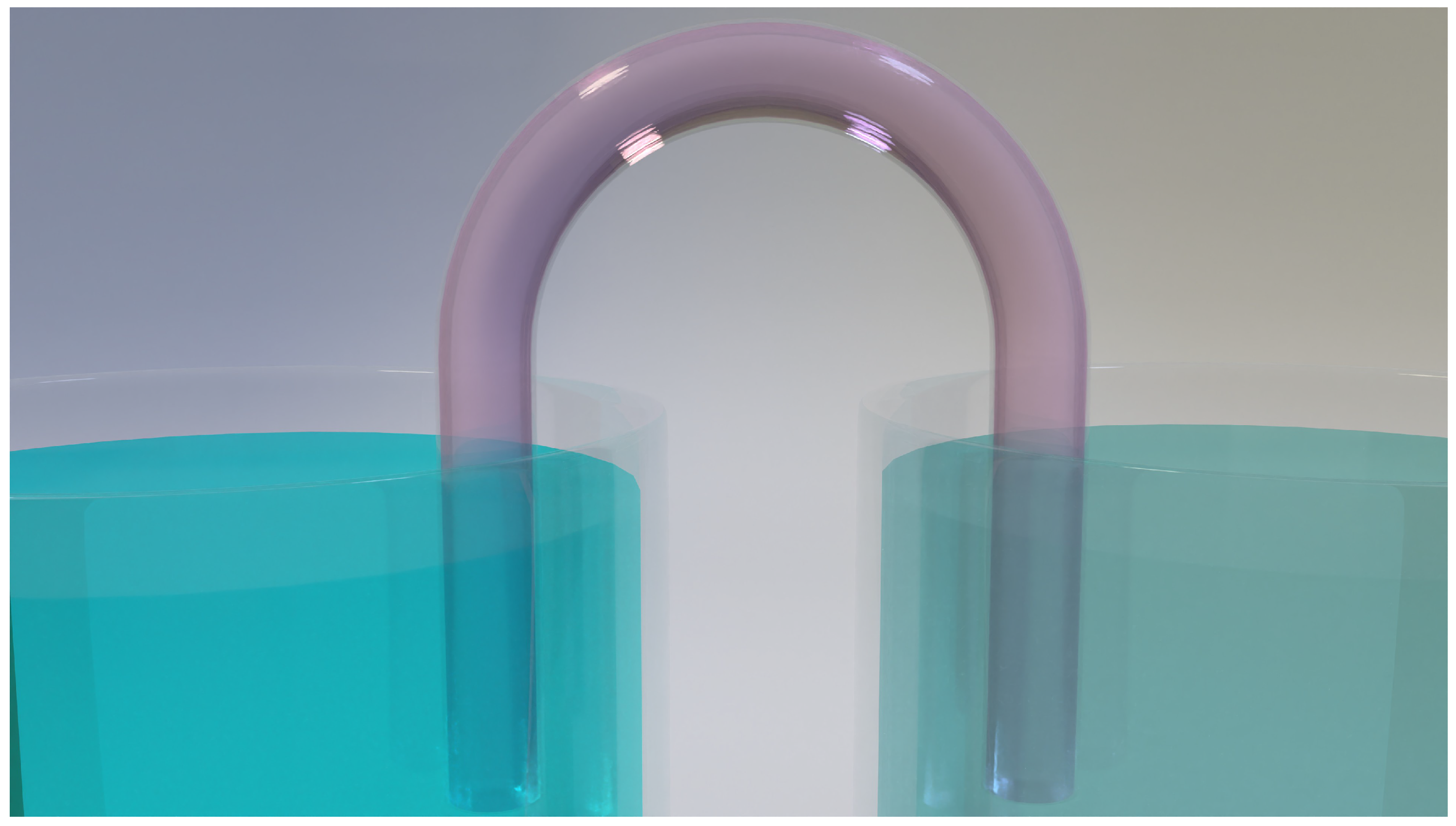

Figure 4 demonstrates an analogous system that uses a chemical apparatus. The membrane is assumed to be semipermeable and is depicted as a salt bridge, permitting only specific ions to cross the ion channels.

3.2. Functioning of the Biological System

The mechanism appears to be fairly consistent: differences in concentrations between two sections drive the transfer of dissolved substances. This unequal concentration initiates a one-way movement from the area of higher concentration to the lower volume, as illustrated in

Figure 5. When charged particles migrate from one section to another, they create a potential difference as a result of the uneven distribution of electrical charges between the compartments. As this potential difference increases, it opposes the chemical diffusion gradient and ultimately stabilizes, as described by the Nernst equation. It is crucial to understand that diffusion continues; however, the flows reach an equilibrium that prevents any change in the potential difference. This is a widely accepted theory.

3.3. Problem of "Ionic" Diffusion in Biology

Although diffusion is frequently apparent, accurately measuring it, particularly within biological contexts, poses certain difficulties. This phenomenon has mainly been assessed and quantified with neutral substances, since their lack of charge does not interfere with the charges of various subsystems. When neutral materials are transitioned between compartments, they maintain the charge and chemical properties of the solutions, except for shifts in concentration. In contrast, the complexity is heightened when diffusion involves ions or charged molecules, as their movement between compartments generally causes disruptions. Biological systems employ various mechanisms to counteract these disruptions.

-

Ion independence.

Hille had already hypothesized ionic independence in the biological scenario [

9]. When ions of opposite charges are sufficiently separated, the electrostatic force is negligible. This assumption can be validated through calculations. The distance between these charges always remains smaller than the thickness of the membrane. This situation does not occur, rendering the intercompartment interaction impractical. Furthermore, how could ions in one compartment influence ions in another if both are free? This assumption of electrostatic independence among ions has not been confirmed under these conditions.

-

Insulation by water molecules.

Moreover, several layers made up of electrically neutral molecules serve to physically isolate these ions, shielding them from both electrostatic and electrical forces. It is known that water molecules exhibit polar properties, which enhance the ion’s range because of hydration layers. The concept of an insulating layer of water has not yet been tested.

-

Electrical independence.

The original form of the Nernst equation applies only to a single type of ion, allowing a straightforward calculation of the membrane potential once the chemical composition and concentrations within the compartments are known. To perform any calculation, one must be aware of the full elemental makeup of each compartment, a requirement not accommodated by the biological hypothesis. The Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation (GHK) is intended to address this issue, but it introduces complications with its dependence on permeability. Membrane permeability assigns a variable valence to an ion, which is determined based on the ion’s concentration in the opposing compartment. Additional challenges arise with the GHK equation [

10]. In chemistry, charges within each compartment are fixed and it is impractical to apply a modifiable factor to these charges because valence cannot be arbitrarily assigned.

In both chemistry and biology, it is essential to consider existing electrical charges. The idea that some ions are electrically neutral while being present yet inactive, or that ions can have variable valence, is not substantiated and is absent from physics or chemistry textbooks.

3.4. System Evolution

Having an equation that defines the behavior of a system is very advantageous. It enables monitoring and predicting the system’s evolution over time. This concept also applies to the chemical model, where the potential difference is highest at the beginning of the experiment and decreases to zero as the concentrations reach equilibrium. Although there may be slight variances, the behavior can generally be anticipated through computation.

One might expect similar outcomes in biology, since the same equation is used to model the same physical phenomenon. However, this is not the case: Each biological representation starts with no potential difference and slowly attains the equation’s value when chemical equilibrium is achieved. Therefore, it is entirely possible to demonstrate that the changes in potential do not correspond to concentration variations. Nernst’s equation fails to adequately describe the phenomena observed in biology.

3.5. Problem of Electroneutrality

In a chemical experiment involving electrodes and surrounding electrolytes, if the electroneutrality is slightly disturbed, the system will eventually adjust to restore balance. Specifically, when a positive ion moves to the metal in the compartment with higher concentration, making it more negative, positive ions traverse the salt bridge to rectify the imbalance. However, when a positive ion exits the metal electrode in the second container, negative ions move through the bridge to maintain balance.

This mechanism is powered by entropic influences, resulting in zero net energy change at the end of the process. In the end, the electrical and chemical forces find equilibrium, maintaining electroneutrality.

Within the bicompartmental cellular model, a distinct breach of electroneutrality arises. Initially, the extracellular and intracellular fluids are treated as electrically neutral because there is no potential difference. However, ions migrate from a region of higher concentration to form a membrane potential, hindering further diffusion. The theory suggests that the diffusion gradient remains nearly unchanged because the number of ions contributing to the potential is small, maintaining minimal concentration variation.

Solidifying the membrane potential does not necessarily mean diminishing the diffusion gradient; diffusion is believed to persist consistently. Over time, an equilibrium state is anticipated to develop until stability is reached. Although electroneutrality is temporarily disrupted, this disturbance is hypothesized to be minimal and localized to the membrane’s external surface. Electrochemical studies suggest that there is no change in the electrical neutrality of the extracellular fluid. Recall: An electromotive force arises without requiring any energy input beyond mere concentration differences. Another way to describe this in electrochemical terms is as follows. The membrane cell replenishes without external energy input. The principle of electroneutrality is violated and expected thermodynamic behaviors are not observed.

3.6. Problem with Concentrations

While concentration values can be substituted by activity coefficients , their use is limited. The concentration of active ions should remain less than . In biological contexts, exceeding this limit is frequent, causing significant errors that limit their applicability. Biological systems frequently do not adhere to the constraints of the Nernst equation.

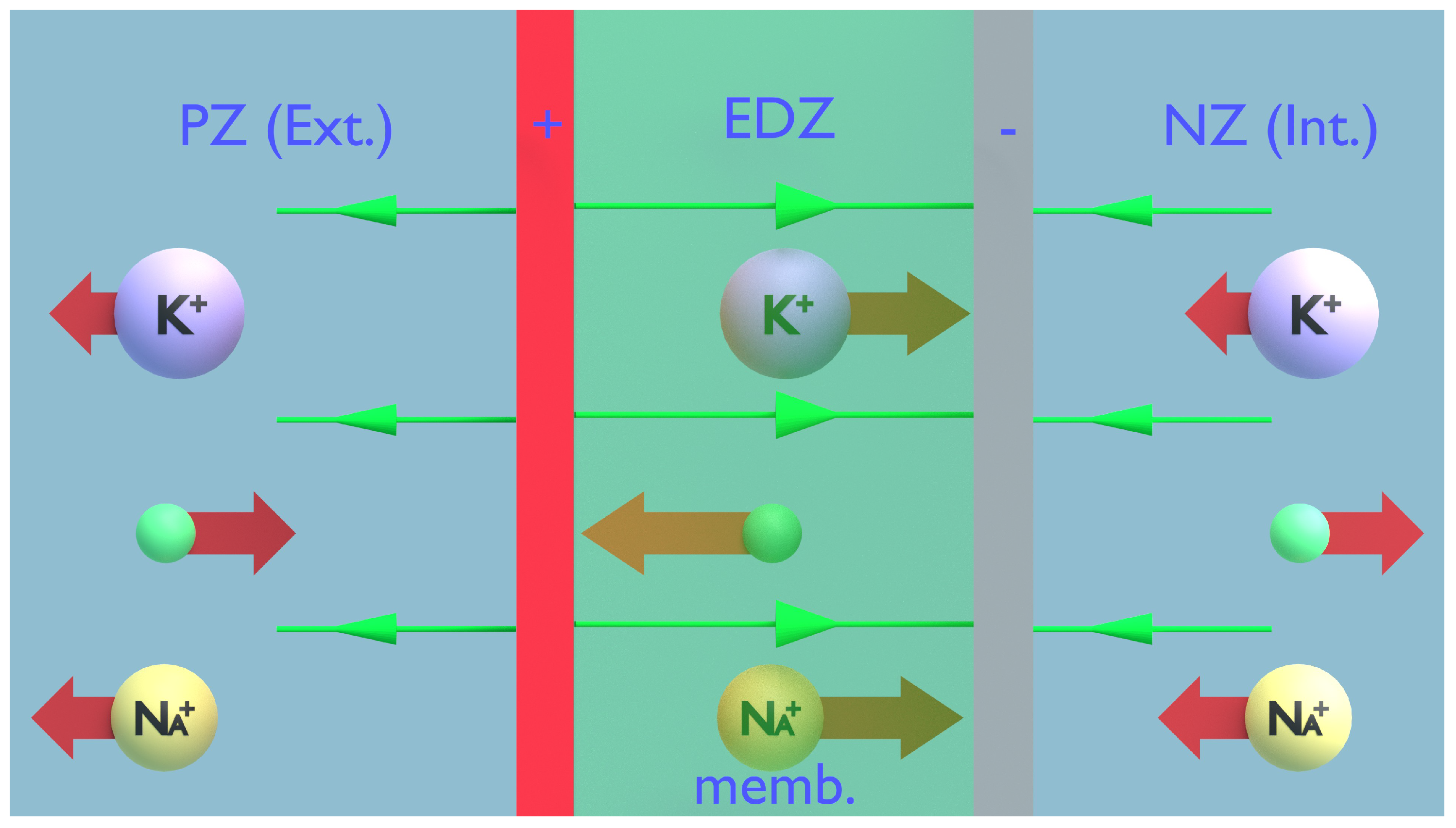

3.7. Constant Electric Field Problem

The detection of a potential difference between the interior and exterior of a cell signifies an electric field created by two hypothetical electrodes: positive ions that have moved outside and negative ions inside the cell (

Figure 6). This is called constant electric field theory [

11]. This theory is crucial for explaining not only the resting potential but also the propagation of action potentials. Additionally, while diffusion attempts to explain particle motion driven by thermal agitation and concentration gradients, electro-diffusion introduces an electric field that organizes these movements and curbs random motion.

As a result, charged particles align themselves with the electric flow: positive ions are attracted to the negative electrode, whereas negative ions are pulled toward the positive electrode.

Biological theory generally emphasizes positive ions such as potassium, sodium, and calcium, often neglecting the dynamics of negatively charged ions.

Figure 6 depicts the biological configuration with a focus on

. The Nernst equation establishes a link between the two compartments on the basis of ion concentrations, without suggesting any mechanism or theory indicating the presence of an electric field, even though such a field exists at every electrode. Biological observations and experiments demonstrate that ions are amassed on the surface or within the membrane.

However, diffusion between the two compartments is clearly impossible.

The electric field surrounding the membrane is located between these compartments and is crucial for diffusion, as it promotes movement or the attraction of ions with opposite charges. There are no barriers to the dispersion of electrodes, which consist of ions. The logic of the model is flawed: a positive ion must first traverse the negative electrode but is eventually attracted by the electric field’s influence.

Once this obstacle is surpassed, the ion is attracted back by the same electrode that was reinforced by its earlier movement. The positive electrode repels it in two instances: first, by propelling it back toward the negative electrode, and then, if it succeeds in passing by the positive electrode, by pushing it outwards into the extracellular space. Similarly, all moving negative ions face comparable obstacles. These negative ions are attracted to the positive ions at the positive electrode, which contributes to their reduction or even elimination. As a result, negative ions become impossible to cross the membrane. Without a doubt, the most remarkable feature is the theory’s "constancy," which appears to contradict the laws of thermodynamics. Intuitively, one would expect the available energy to diminish as the potential difference grows, or some form of decline to occur! However, the diffusive force, driven entirely by the random motion of the particles, invariably prevails over the increasing electrical force, which is generally used to regulate the chaotic movements of the particles [

12,

13]. One could propose a more elegant alternative hypothesis by suggesting a reduction in the influence of diffusive forces as the potential difference intensifies.

Evidently, the ions slow down and eventually stop as a result of the increased electrical force, leading to the obstruction of the system.

The establishment of a potential difference removes any possibility of diffusion and ionic movement, while ensuring a stable condition. However, it is clear that interactions occur and that they must comply with the laws of physics and thermodynamics, as physics is unyielding. The coexistence of diffusion with a constant electric field positioned between two diffusion compartments is not possible.

Table 1 presents an overview of the commonalities and distinctions identified in this study. These elements are emphasized in red.

"Equation"

5 illustrates how the GHK equation is derived from the BH model, which in turn relies on an inaccurate application of diffusion principles. It is apparent that if any single component of this theoretical framework is disproven, the entire structure is compromised.

Thus, a thorough re-evaluation of our strategy for understanding membrane potential generation is imperative. Our findings indicate that ion diffusion is infeasible. A constant electric field impedes any exchange. Biology’s disregard for the essential conditions of the Nernst equation renders its application invalid.

Moreover, the existing theory fails to propose a satisfactory hypothesis that explains the potassium concentration disparity, with cells having nearly 40 times more potassium than their external environment [

14,

15,

16]. A scenario not supported by diffusion. Consequently, we must devise a scientifically sound model that aligns with fundamental principles. It is evident, with numerous examples to study, that proteins are significantly influential [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

There are lessons to be learned from cell division. There are also lessons to be learned from the past, which may offer theories of little use, but which have much more solid and verified scientific foundations [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

4. Conclusions

For more than a century, biology has incorrectly employed the Nernst equation from chemistry despite its inapplicability due to the fact that the necessary conditions for its application are not met in either strict or biological terms.

Consequently, Bernstein’s theory lacks a solid foundation, as the underlying hypothesis is flawed.

Bernstein’s hypothesis contradicts the principle of electroneutrality found in all biological specimens.

In addition, no chemical equation has an electrogenic role.

Moreover, there is no metal suitable for a phase transition that donates electrons.

This also means that the GHK equation, which depends on Bernstein’s hypothesis, cannot be considered valid. According to standard scientific principles, biology should reevaluate one of its foundational tenets when it is broadly called into question.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D. and H.T. and V.M.; investigation, B.D.; writing—original draft preparation, B.D. and H.T. and V.M; writing—review and editing, B.D. and H.T. and V.M; visualization, B.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was not subsidized.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bernstein, J. Untersuchungen zur Thermodynamik der bioelektrischen Ströme. Pflüger Archiv für die Gesammte Physiologie des Menschen und der Thiere 1902, 92, 521–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nernst, W. Begründung der Theoretischen Chemie: Neun Abhandlungen, 1889-1921, 1. aufl ed.; Number Bd. 290 in Ostwalds Klassiker der exakten Wissenschaften, Verlag Harri Deutsch: Frankfurt am Main, 2003. OCLC: ocm52218139.

- Wehrl, A. General properties of entropy. Reviews of Modern Physics 1978, 50, 221–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, A. Ueber Diffusion. Annalen der Physik 1855, 170, 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maex, R. On the Nernst–Planck equation. Journal of Integrative Neuroscience 2017, 16, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoharan, V.N. Colloidal matter: Packing, geometry, and entropy. Science 2015, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laidler, K.J.; Meiser, J.H. Physical chemistry; Benjamin/Cummings Pub. Co: Menlo Park, Calif, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bockris, J.O.; Reddy, A.K.N. Modern Electrochemistry; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hille, B. Ion channels of excitable membranes, 3rd ed ed.; Sinauer: Sunderland, Mass, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Y. The Goldman-Hodgkins-Katz Equation, Reverse-Electrodialysis, and Everything in Between 2024. [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/2411.03342].

- Goldman, D.E. POTENTIAL, IMPEDANCE, AND RECTIFICATION IN MEMBRANES. The Journal of General Physiology 1943, 27, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, A.L.; Keynes, R.D. The potassium permeability of a giant nerve fibre. The Journal of Physiology 1955, 128, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. L. Hodgkin, P. Howrowicz. The influence of potassium and chloride ions on the membrane potential of single muscle fibers. J. Physiol. 1959, 148, 127–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallin, B.G. The Relation between External Potassium Concentration, Membrane Potential and Internal Ion Concentrations in Crayfish Axons. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 1967, 70, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, P.S.; Vandavasi, V.G.; Weiss, K.L.; Afonine, P.V.; el Omari, K.; Duman, R.; Wagner, A.; Coates, L. Anomalous X-ray diffraction studies of ion transport in K+ channels. Nature Communications 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert Ling. MAINTENANCE OF LOW SODIUM AND HIGH POTASSIUM LEVELS IN RESTING MUSCLE CELLS. J. Physiol. 1978, 280, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, L.M.; Liu, X.; Verheul, J.; Egan, A.J.; Vollmer, W.; den Blaauwen, T. Cell division cycle fluctuation of Pal concentration in Escherichia coli. Access Microbiology 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouaux, E.; MacKinnon, R. Principles of Selective Ion Transport in Channels and Pumps. Science 2005, 310, 1461–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, S.; Bhat, A.; Kusumi, A. A Survey of Models of Cell Membranes: Toward a New Understanding of Membrane Organization. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2023, 15, a041394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, R.; Escribá, P.V. Structural Basis of the Interaction of the G Proteins, Gαi1, Gβ1γ2 and Gαi1β1γ2, with Membrane Microdomains and Their Relationship to Cell Localization and Activity. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, O.A.; Disalvo, E.A. A new model for lipid monolayer and bilayers based on thermodynamics of irreversible processes. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0212269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delalande, B.; Tamagawa, H.; Matveev, V. Membrane Potential: The Enigma of Ion Pumps. [CrossRef]

- Delalande, B.; Tamagawa, H.; Matveev, V. Membrane Potential: Any Diffusion? [CrossRef]

- Laurent Jaeken. The neglected functions of intrinsically disordered proteins and the origin of life. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2017, 126, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent Jaeken. The Greatest Error in Biological Sciences, Started in 1930 and Continuing Up to Now, Generating Numerous Profound Misunderstandings. Current Advances in Chemistry and Biochemistry 2021, 5, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert N. Ling. Life at the Cell and Below-Cell Level: The Hidden History of a Fundamental Revolution in Biology; Pacific Press, New York, 2001.

- Hirohisa Tamagawa, Sachi Morita. Membrane Potential Generated by Ion Adsorption. Membranes 2014, 4, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. Tamagawa, K. Ikeda. Another interpretation of Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation based on the Ling’s adsorption theory. Eur. Biophys. J. 2018, 47, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Tamagawa, T. Mulembo, B. Delalande. What can S-shaped potential profiles tell us about the mechanism of membrane potential generation? Euro. Biophys, J. 2021.

- Vladimir Matveev. Comparison of fundamental physical properties of the model cells (protocells) and the living cells reveals the need in protophysiology. International Journal of Astrobiology 2017, 16, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimir Matveev. Cell theory, intrinsically disordered proteins, and the physics of the origin of life. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2019, 149, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Depiction of potassium chloride salt diffusion (potassium atom in pink, chloride in green). The atomic sizes are accurate, but not the quantity. The solvent, water, is not shown, although it plays a crucial role, as water molecules are capable of forming hydration layers around each ion. This formation, along with water molecule aggregation around ions, extends the electric charge range of the ion, while diminishing its amplitude. On a macroscopic scale, it is evident that the area where KCl is diffusing lacks homogeneity. Hence, it can be inferred that the diffusion equation does not apply at this scale.

Figure 1.

Depiction of potassium chloride salt diffusion (potassium atom in pink, chloride in green). The atomic sizes are accurate, but not the quantity. The solvent, water, is not shown, although it plays a crucial role, as water molecules are capable of forming hydration layers around each ion. This formation, along with water molecule aggregation around ions, extends the electric charge range of the ion, while diminishing its amplitude. On a macroscopic scale, it is evident that the area where KCl is diffusing lacks homogeneity. Hence, it can be inferred that the diffusion equation does not apply at this scale.

Figure 2.

Depiction of an early-stage concentration cell in action. The compartment on the left holds the highest concentration solution, while the right contains the lowest concentration. The concentration gradient provides the free energy source, yet it is the chemical reactions and phase transformations that are occurring. A copper ion is formed from the copper electrode on the right and donates 2 electrons to the electrical circuit. On the left, these 2 electrons are utilized to convert a ion into metal, a crucial part of the reaction. At the experiment’s onset, the potential difference is at its peak level. The significance of concentration is highlighted by the font size.

Figure 2.

Depiction of an early-stage concentration cell in action. The compartment on the left holds the highest concentration solution, while the right contains the lowest concentration. The concentration gradient provides the free energy source, yet it is the chemical reactions and phase transformations that are occurring. A copper ion is formed from the copper electrode on the right and donates 2 electrons to the electrical circuit. On the left, these 2 electrons are utilized to convert a ion into metal, a crucial part of the reaction. At the experiment’s onset, the potential difference is at its peak level. The significance of concentration is highlighted by the font size.

Figure 3.

At the conclusion of the experiment, the concentration cell’s representation shows that both the left and right compartments now possess identical concentrations. The potential difference has reached its lowest point. The equality of concentrations is accentuated by the font size.

Figure 3.

At the conclusion of the experiment, the concentration cell’s representation shows that both the left and right compartments now possess identical concentrations. The potential difference has reached its lowest point. The equality of concentrations is accentuated by the font size.

Figure 4.

The biological model of the Nernst equation involves two compartments linked by a salt bridge serving as an ion channel. This setup facilitates diffusion from left to right, resulting in a potential difference. Notably, there are no electrodes, metals, or chemical reactions involved.

Figure 4.

The biological model of the Nernst equation involves two compartments linked by a salt bridge serving as an ion channel. This setup facilitates diffusion from left to right, resulting in a potential difference. Notably, there are no electrodes, metals, or chemical reactions involved.

Figure 5.

The Nernst equation’s biological model comprises two separate areas connected via a salt bridge that functions as an ion channel. It presumes that positive ions move from the compartment with higher concentration to the one with lower concentration.

Figure 5.

The Nernst equation’s biological model comprises two separate areas connected via a salt bridge that functions as an ion channel. It presumes that positive ions move from the compartment with higher concentration to the one with lower concentration.

Figure 6.

PZ refers to the positive zone, which is the cell’s external (Ext.) surface layer. NZ indicates the negative zone, representing the inner (Int.) layer of the cell. EDZ, or the electrical diffusion zone, is situated within the membrane (memb.). Assuming there is an electric field influencing ion movements across the membrane, it becomes apparent that ion movement is not the primary focus of the hypothesis. It is clear that potassium and sodium ions are unable to penetrate the cell since they are repelled by the positive external layer. Similarly, they cannot exit as they are drawn in by the negatively charged inner layer. Consequently, we should disregard any uniform or constant fields.

Figure 6.

PZ refers to the positive zone, which is the cell’s external (Ext.) surface layer. NZ indicates the negative zone, representing the inner (Int.) layer of the cell. EDZ, or the electrical diffusion zone, is situated within the membrane (memb.). Assuming there is an electric field influencing ion movements across the membrane, it becomes apparent that ion movement is not the primary focus of the hypothesis. It is clear that potassium and sodium ions are unable to penetrate the cell since they are repelled by the positive external layer. Similarly, they cannot exit as they are drawn in by the negatively charged inner layer. Consequently, we should disregard any uniform or constant fields.

Table 1.

Comparative table highlighting the distinctions between various diffusion types and the Bernstein (BH) and GHK theories. Notably, it’s significant that Nerst’s approach (as demonstrated with a concentration cell) does not rely on diffusion. It is evident that biologists’ concept of diffusion for a single type of ion, whether positive or negative, conflicts with the principles of entropy and electromotive forces. Thus, this form of diffusion also deviates in terms of electroneutrality. Since it has not been confirmed through scientific validation, the GHK model, which is derived from the BH model stemming from an electrically characterized diffusion model, is deemed invalid.

Table 1.

Comparative table highlighting the distinctions between various diffusion types and the Bernstein (BH) and GHK theories. Notably, it’s significant that Nerst’s approach (as demonstrated with a concentration cell) does not rely on diffusion. It is evident that biologists’ concept of diffusion for a single type of ion, whether positive or negative, conflicts with the principles of entropy and electromotive forces. Thus, this form of diffusion also deviates in terms of electroneutrality. Since it has not been confirmed through scientific validation, the GHK model, which is derived from the BH model stemming from an electrically characterized diffusion model, is deemed invalid.

| prop. / theor. |

neutral |

salt |

ion + ⊕ - |

Nersnt |

BH |

GHK |

| diffusion |

YES |

YES |

YES |

NO |

YES |

YES |

| entropic |

YES |

YES |

NO |

YES |

NO |

NO |

| potential |

NO |

NO |

YES |

YES |

YES |

YES |

| RedOx |

NO |

NO |

NO |

YES |

NO |

NO |

| scientific |

YES |

YES |

NO |

YES |

NO |

NO |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).