Cover Letter

Severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI) has been one of the most debated topics in recent decades among neurosurgeons and intensivists around the world, however, intracranial vascular trauma that may be part of the pathophysiological mechanisms involved, identification of the involvement of vascular injury in the symptomatic clinical evidence and prognosis, have not been sufficiently studied. Within this heading, trauma or traumatic injury of the basilar artery has been even less studied, which has also been described as being associated with mild head injuries in children and adults.

Introduction

Severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI) has been one of the most debated topics in recent decades among neurosurgeons and intensivists around the world, however, intracranial vascular trauma that may be part of the pathophysiological mechanisms involved, identification of the involvement of vascular injury in the symptomatic procession of clinical evidence and prognosis, have not been sufficiently studied. Within this heading, trauma or traumatic injury of the basilar artery has been even less studied, which has also been described as being associated with mild head injuries in children and adults [

1].

Traumatic injury to the basilar artery could be classified as primary, when the injury is due to direct transfixing or non-transfixing trauma, which causes vascular rupture, with direct bleeding of the artery or its branches [

2], a condition that is extremely rare. Non-transfixing vascular trauma is when the artery is directly traumatized but does not rupture, which would cause post-traumatic vasospasm, arterial occlusion with ischemia and associated infarction. Here, in this variant, arterial entrapments have been described with or without clivus fractures [

1,

3].

Basilar artery injury is classified as secondary, when post-traumatic bleeding occurs due to rupture of a pre-existing vascular lesion, known or unknown (saccular aneurysms of the main branches of the artery or fusiform aneurysms of the artery itself, mega dolico basilar artery, dissecting aneurysms, among others).

This section includes iatrogenic lesions of the basilar artery due to surgical trauma in the posterior fossa or in endoscopic endonasal approaches for pituitary adenomectomies or for resection of tumor lesions in the sellar and clivus regions. Bleeding from traumatic pseudoaneurysms is a described lesion [

4]. Hemorrhagic lesions of the brainstem can also occur due to bleeding from the perforating branches of the basilar artery, as a consequence of transtentorial herniation in patients with severe head injury (gTBI) with associated intracranial hypertension, known as Duret hemorrhages [

5].

Relevant Sections

Brief Microanatomical Description of the Basilar Artery

The basilar artery runs through the homonymous groove located in the midline of the ventral face of the brain stem, in most of the human brains studied postmortem [

6], although its arrangement can sometimes be tortuous. It is formed after the union of both vertebral arteries, left and right, at the level of the medulla-pontine junction. Excluding the postero-inferior cerebellar artery, whose origin is predominantly in the vertebral arteries, its main branches are the anterior-superior cerebellar artery, the superior cerebellar artery and at the level of the interpeduncular cistern it has its bifurcation in the posterior cerebral arteries [

6]. It is approximately 20-40 mm long and has a diameter between 2.5-3.5 mm. Each of the segments of the basilar artery has a considerable number of perforating branches, which makes its anatomy a "vascular complex".

Discussion

Clinical Picture

The clinical picture of the traumatic lesion of this arterial group can occur in isolation, which is rare, or associated with other traumatic lesions, skull base fractures, but more frequently they can be found as part of a complex symptomatic clinical status associated to polytrauma, with evidence of lesions in various organs and systems, including supratentorial or infratentorial cranial lesions of a greater or lesser extent, of a diverse nature, which make diagnosis difficult in most cases. In the reviewed literature there is evidence of the association between the presence of fractures in the skull base, predominantly in the clivus or the sphenoid sinus, and the entrapment of the basilar artery in the fracture [

7,

8].

Iatrogenic trauma to the basilar artery is an event feared by neurological surgeons and occurs mainly in surgeries for resection of tumors in the sellar region, or in endoscopic surgeries for third ventriculostomy, in triventricular hydrocephalus or in direct approaches to lesions in the posterior fossa. Currently, this fearsome complication has been reduced by the use of microvascular doppler probes, which allow insonating the arteries of the posterior fossa during the intraoperative period [

9].

The clinical evidence can vary from the absence of symptoms and signs, to a very florid picture with compromise of vital functions and death in a short period of time.

The manifestations dependent on hemorrhagic events tend to have a more rapid evolution over time, while the manifestations dependent on ischemic events, whether due to vasospasm, occlusion of the basilar artery or its branches, incarceration within a diastatic fracture at the cranial base, or due to arterial dissection, usually take a little longer than hemorrhagic ones [

10].

In the brain stem there are several vital centers such as the respiratory center, the cardiac center, the vasomotor center, the medullary rhythmicity center, among others, so the main symptoms and signs secondary to a vascular traumatic injury at this level will be characterized by the presence of alteration in the level of consciousness, due to dysfunction in the cerebral cortex-relay axis in the diencephalon-ascending activating reticular formation, to which are associated alterations for the control of systemic arterial pressure, respiratory dysfunction, postural alterations, paralysis of cranial nerves, motor and sensory deficits in the extremities among other manifestations. The presence of cloistered man syndrome has been reported as a consequence and sequel of traumatic injury to the basilar artery [

11].

Complementary Exams

In addition to the entire battery of complementary sequenced hematological, electrolyte and gasometry tests that are indicated for all neurotrauma patients admitted to an intensive care unit, imaging tests are the ones that contribute the most to the diagnosis of a lesion of the vascular complex of the basilar artery. . Among them the most outstanding are:

Simple and contrasted CT scan of the skull.

Vascular opacification studies: (AngioTAC, Angio MRI, digital subtraction angiography).

Magnetic Resonance images.

Transcranial Doppler.

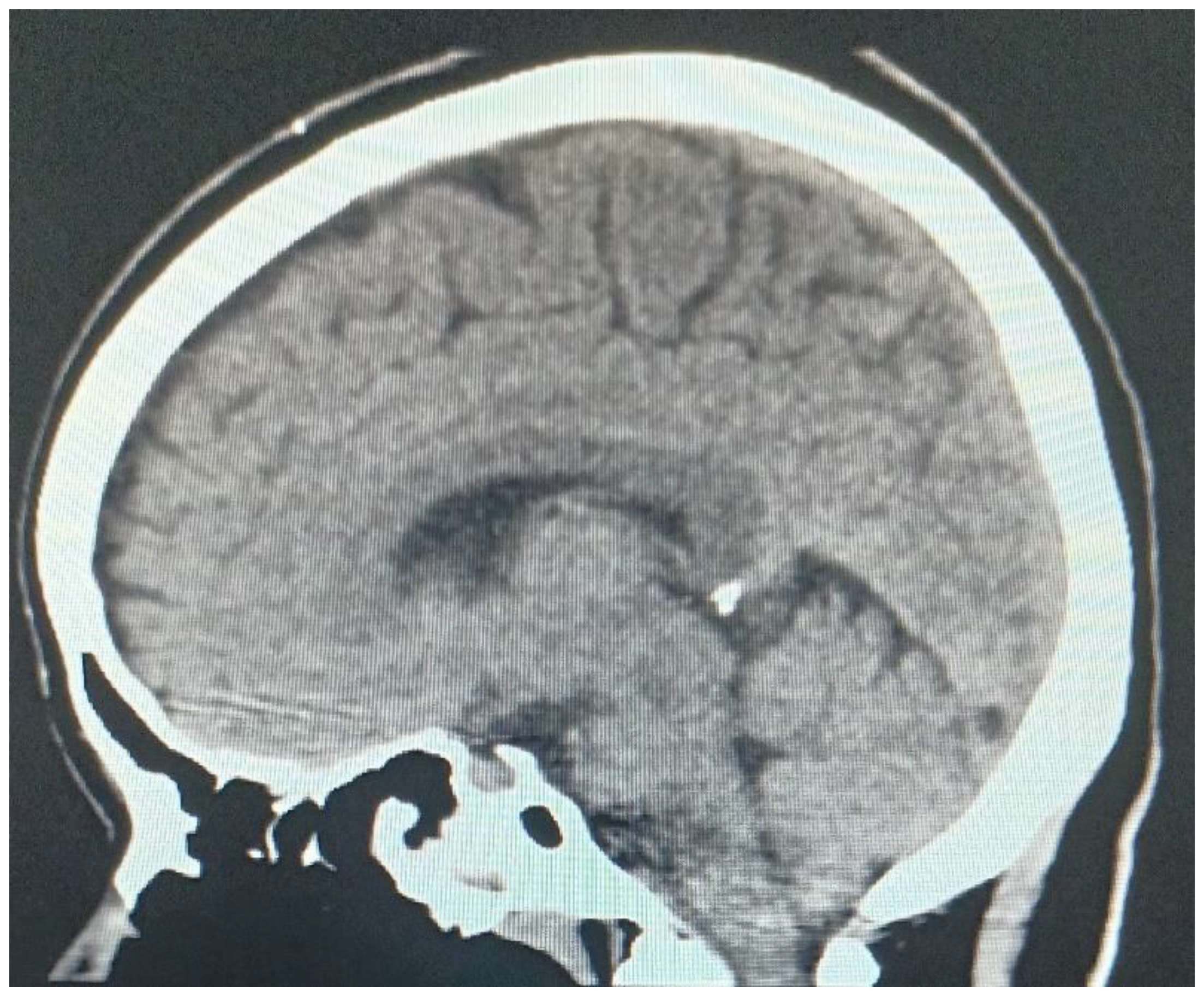

Simple and contrast-enhanced computed tomography is an examination that can help in the diagnosis in the acute phase between a hemorrhagic or ischemic vascular lesion (

Figure 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also contribute to the diagnosis of this type of injury.

Doppler is an examination that can be performed at the patient's bedside and can offer a lot of information in neurocritical or neurotraumatized patients in general. Through this test, intracranial pressure, cerebral perfusion pressure, the state of cerebral autoregulation can be estimated, and the presence or absence of vasospasm can be diagnosed [

12,

13].

The insonation of the basilar artery is through the foramen magnum to a depth of 70-120 mm [

13]. The presence of vasospasm of this arterial complex after head trauma is increasingly diagnosed.

Treatment

The treatment will be aimed at controlling the damage, controlling the coagulopathy of severely traumatized patients, with special attention to patients taking anticoagulants who suffer from head trauma and who require neurosurgical intervention [

14] to correct the primary lesion and interrupt the progression of cerebral physiopathological mechanisms towards the establishment of secondary damage [

5,

15,

16].

Among the most used procedures is the primary decompressive craniectomy [

14,

15] of both the supratentorial and infratentorial compartments.

The direct correction of the traumatic transection of the basilar artery is a complex procedure and generally the magnitude of the arterial bleeding does not allow it. When the physiological hemostatic mechanisms control bleeding, endovascular treatment has allowed the placement of flow diverters or stents in this type of lesion, as well as performing other maneuvers through this type of treatment [

4,

17].

The development of Ischemic patterns secondary to basilar artery lesions that have received endovascular treatment have been described, when clinical conditions have allowed it [

8,

18].

Finally, all treatment protocols are adjusted for patients with severe head trauma with associated intracranial hypertension.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Angel Jesús Lacerda Gallardo. Bibliographic review: Angel Jesús Lacerda Gallardo, Daysi Abreu Pérez, Miguel de Jesús Mazorra Pazos Data Curation: Angel Jesús Lacerda Gallardo, Daysi Abreu Pérez. Research: Angel Jesús Lacerda Gallardo, Daysi Abreu Pérez, Miguel de Jesús Mazorra Pazos. Methodology: Angel Jesús Lacerda Gallardo, Daysi Abreu Pérez. Validation: Angel Jesús Lacerda Gallardo, Daysi Abreu Pérez, Miguel de Jesús Mazorra Pazos. Original draft: Angel Jesús Lacerda Gallardo. Writing-review and editing: Angel Jesús Lacerda Gallardo, Daysi Abreu Pérez. The authors declare that we have no conflicts of interest and that we have not received funding to carry out the research.

References

- Yamaoka A, Miyata K, Bunya N, Mizuno H, Irifune H, Yama N et al. Traumatic Basilar Artery Entrapment without Longitudinal Clivus Fracture: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2018; 58: 362-367.

- Jha AK, Kumar J, Harsh V, Kumar A. Penetrating injury of the posterior cranial fossa by a stone. Neurol India [serial online] 2016 [cited 2023 May 26]; 64:1081-2. Available from: https://www.neurologyindia.com/text.asp? 2016/64/5/1081/190272.

- Moyer JD, Dioguardi Burgio M, Abback PS, Gauss T. Isolated basilar artery dissection following blunt trauma challenging the Glasgow coma score: A case report. Am J Emerg Med 2021 Sep;47: 347.e1-347.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.03.008. [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas Ruiz-Valdepeñas E, Kaen A, Tirado-Caballero J, Di Somma A, Iglesias Pais M, Vázquez Domínguez M et al. Basilar Artery Injury During Endonasal Surgery: Stepwise to Control Bleeding. Oper neurosurg (hagerstown) . 2021 feb 16;20(3):282-288. [CrossRef]

- Beucler N, Cungi PJ, Dagain A. Duret Brainstem Hemorrhage After Transtentorial Descending Brain Herniation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg . 2023 May;173:251-262.e4. https://doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.02.110. Epub 2023 Mar 2. [CrossRef]

- Rhoton AL. The cerebellar arteries. Neurosurgery 2000; 47 Suppl 3: S29-68.

- Kliesch S, Bauknecht C, Bohner G, et al. BMJ Case Rep 2016 Published online: [7 de Julio del 2023] doi:10.1136/bcr-2016- 012558. [CrossRef]

- Balshaw J, Nicholls M, Tsai Y, Chaganti J. Post traumatic herniation of basilar artery into sphenoid sinus with preserved arterial flow-an unusual complication. Interdisciplinary Neurosurgery: Advanced Techniques and Case Management 2021; 25: 101268.

- Schmidt RH. Use of a microvascular doppler probe to avoid basilar artery injury during endoscopic third ventriculostomy. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1999 Jan;90(1):156-9. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.1.0156. PMID: 10413172. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laing BR, Hedayat HS. Basilar artery incarceration secondary to a longitudinal clivus fracture: A rare and favorable outcome of an often devastating injury. Surg Neurol Int 2022;13:107.

- Lagrand TJ, Bruijnes VAJ, Van der Stouwe AMM, Deckers EA, Mazuri A et al. Locked-In Syndrome after Traumatic Basilar Artery Entrapment within a Clivus Fracture: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Neurotrauma Reports 2020; 1.1: 73–77. DOI:10.1089/neur.2020.00015. [CrossRef]

- Piriz Assa AR, Abdo-Cuza A, De la Cruz De la Cruz HR. Ecografía Doppler transcraneal para estimar la presión intracraneal y presión de perfusión cerebral en pacientes pediátricos neurocríticos. Rev Cuban Pediatr. [Internet]. 2022 mar [citado 2022 abr 19];94(2):e1597. Disponible en: http://www.revpediatria.sld.cu/index.php/ped/article/view/1597.

- Camilo N. Rodríguez and Ryan Splittgerber Transcranial Doppler (TCD) and Trancranial Color-Coded Duplex Sonography (TCCS): Applied Neuroanatomy.. In: Rodríguez CN, Baracchini C, Mejía Mantilla JH, Czosnyka M, Suárez JI, Csiba L, Pupo C, Bartels E, editors. Neurosonology in Critical Care. Cham 7: Springer; 2022: 905-19.

- Puzio TJ, Murphy PB, Kregel HR, Ellis RC, Holder T, Wandling MW et al. Delayed Intracranial Hemorrhage Following Blunt Head Trauma While on Direct Oral Anticoagulants: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2021 June ; 232(6): 1007–1016.e5. Disponible en: doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.02.016. [CrossRef]

- Lacerda Gallardo AJ, Abreu Pérez D. Craniectomía descompresiva en el neurotrauma grave. An Acad Cienc Cuba [internet] 2022 [citado en día, mes y año]; 12(3):e1185. Disponible en: http://www.revistaccuba.cu/index.php/revacc/article/view/1185.

- Rubiano AM, Maldonado M, Montenegro J, Restrepo CM, Khan AA, Monteiro R et al. The Evolving Concept of Damage Control in Neurotrauma: Application of Military Protocols in Civilian Settings with Limited Resources. World Neurosurg. 2019; 125: e82-e93.

- Ahmed SU, Kelly ME, Peeling L. Endovascular retrieval of bullet fragment from the basilar artery terminus. J Neurointerv Surg. 2022 Oct;14(10):1042-1044. Disponible en: doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2022-018751. Epub 2022 Apr 22. [CrossRef]

- Kanamori F, Yamanouchi T, Kano Y, Koketsu N. Endovascular intervention in Basilar Artery Entrapment within the Longitudinal Clivus Fracture: A Case Report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2018; 58: 356–361.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).