Submitted:

08 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objectives

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.3. Selection Process

2.2.4. Data Collection Process

2.2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.2.6. Data Synthesis

2.2.7. Bias Assessment

3. Results

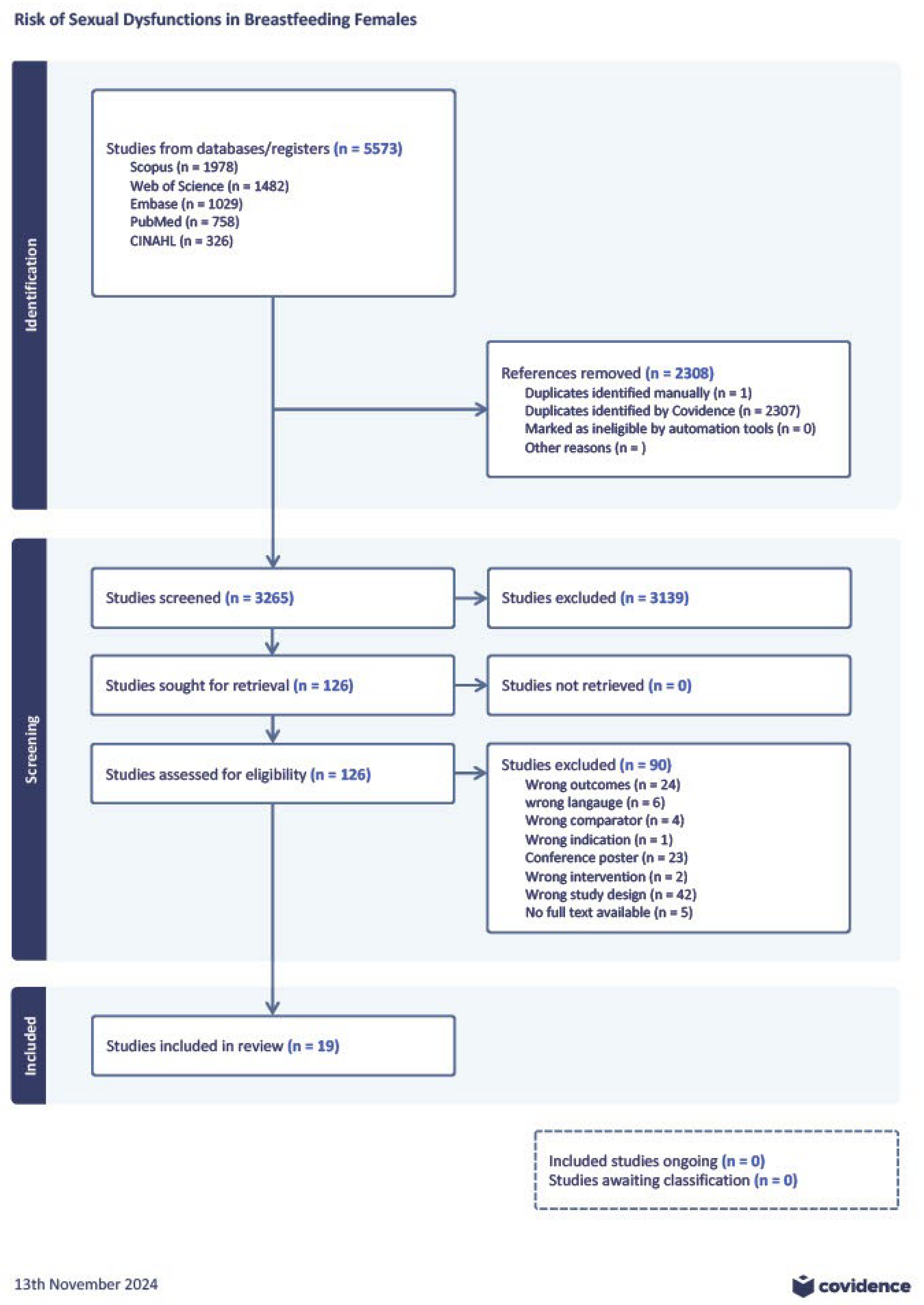

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Characteristics of Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis

3.3. Scores in FSFI Domains, Irrespective of Infant Feeding Practices

3.4. Scores in FSFI Subscales

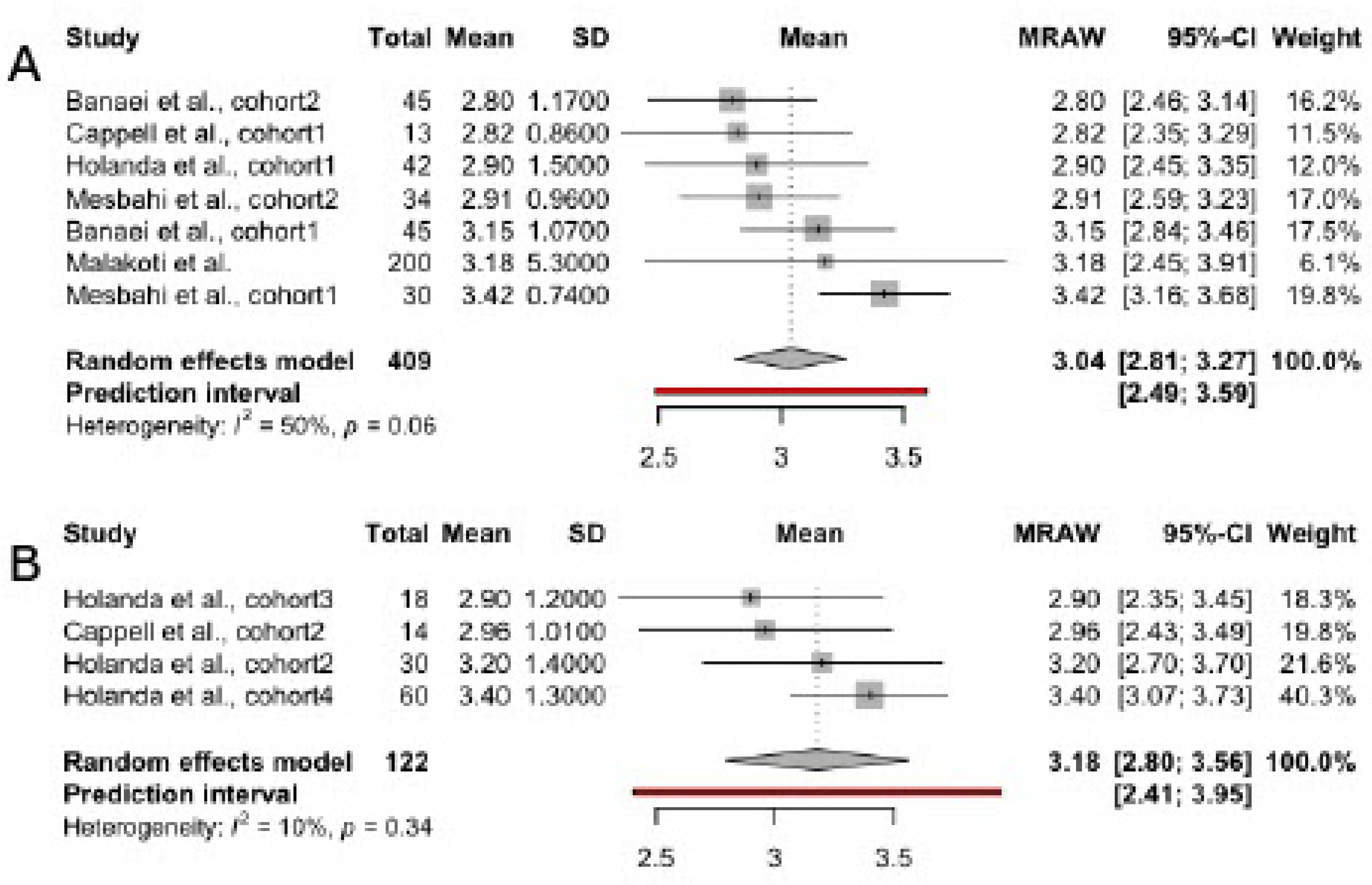

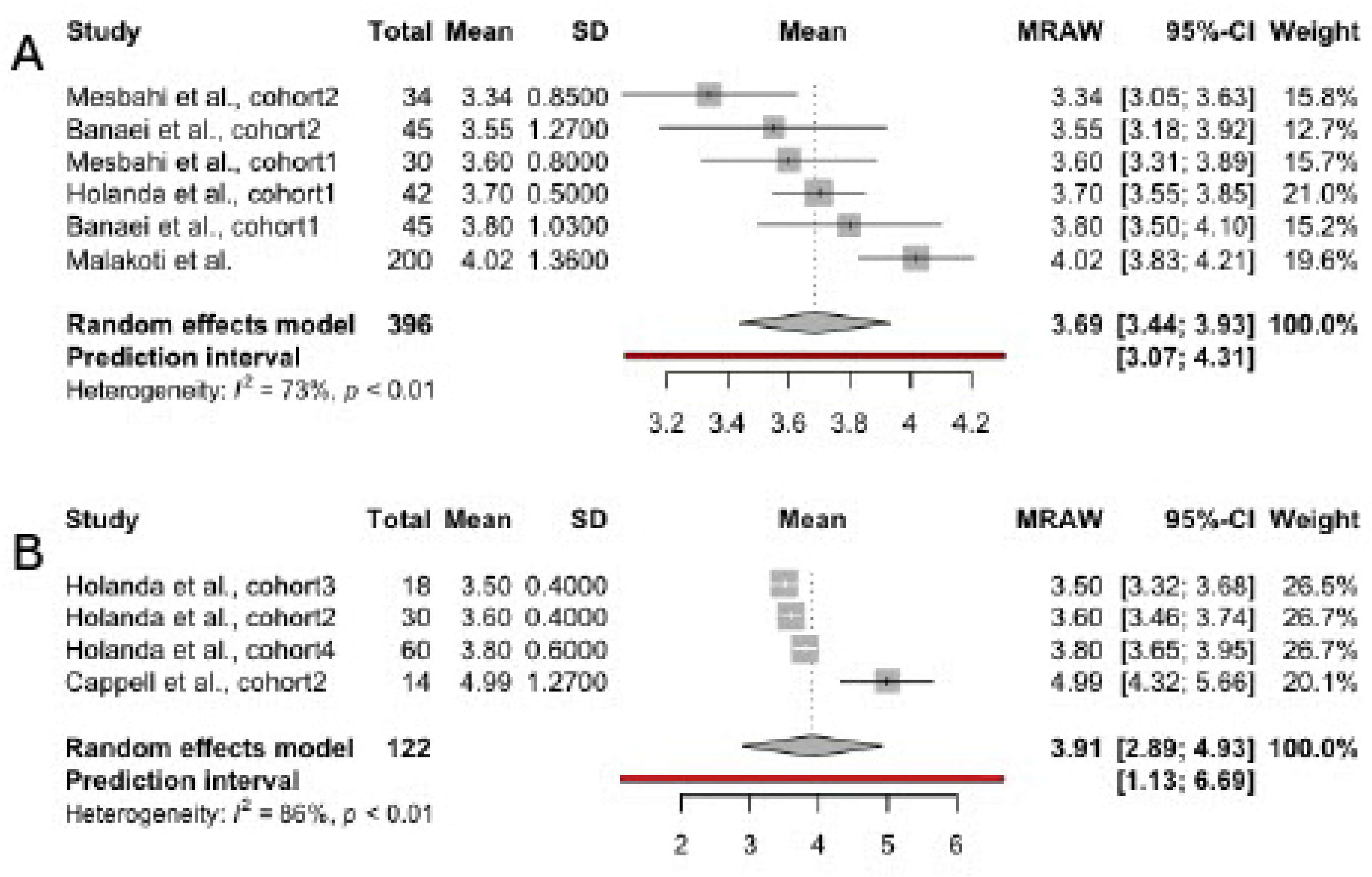

3.4.1. Desire

3.4.2. Arousal

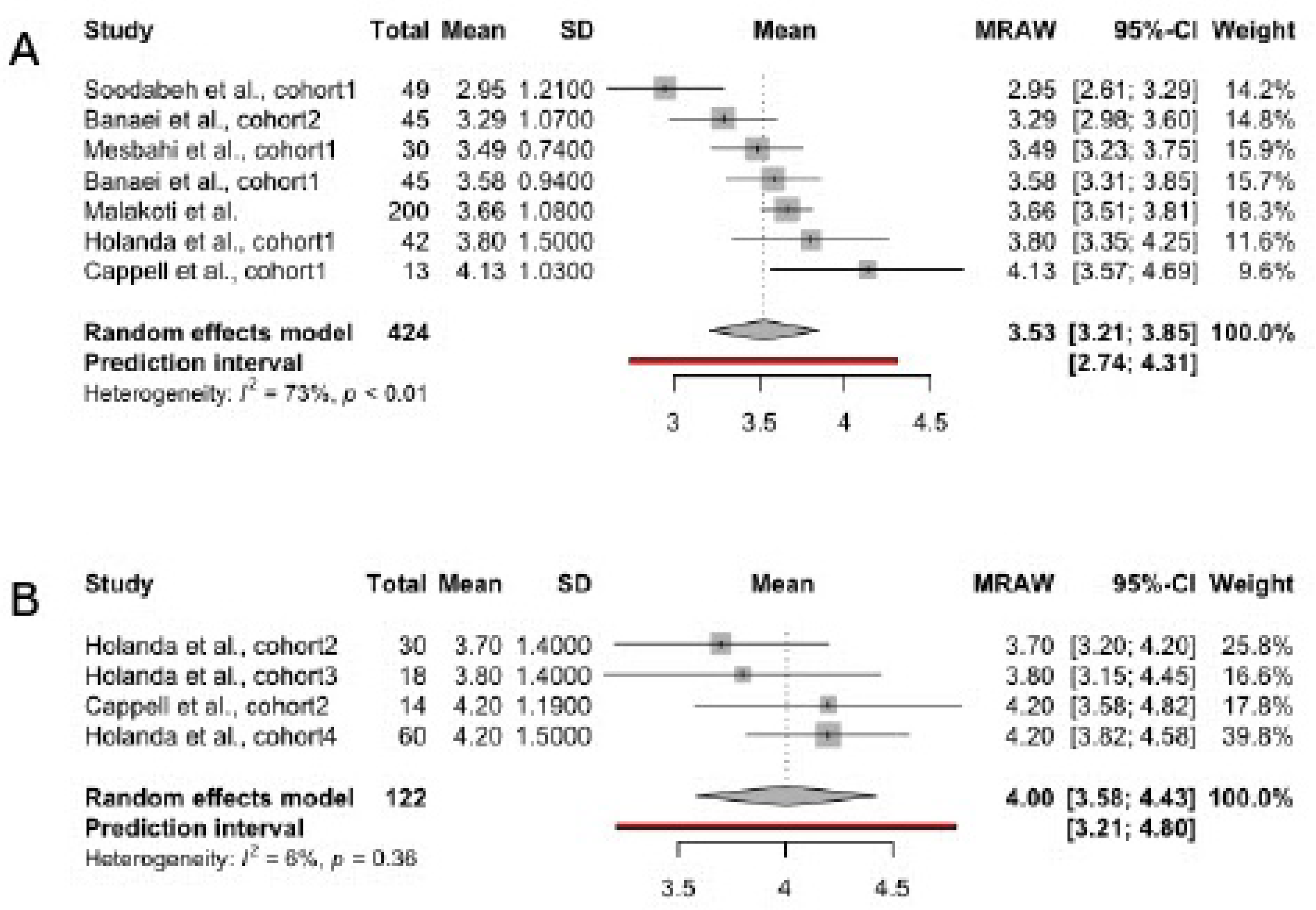

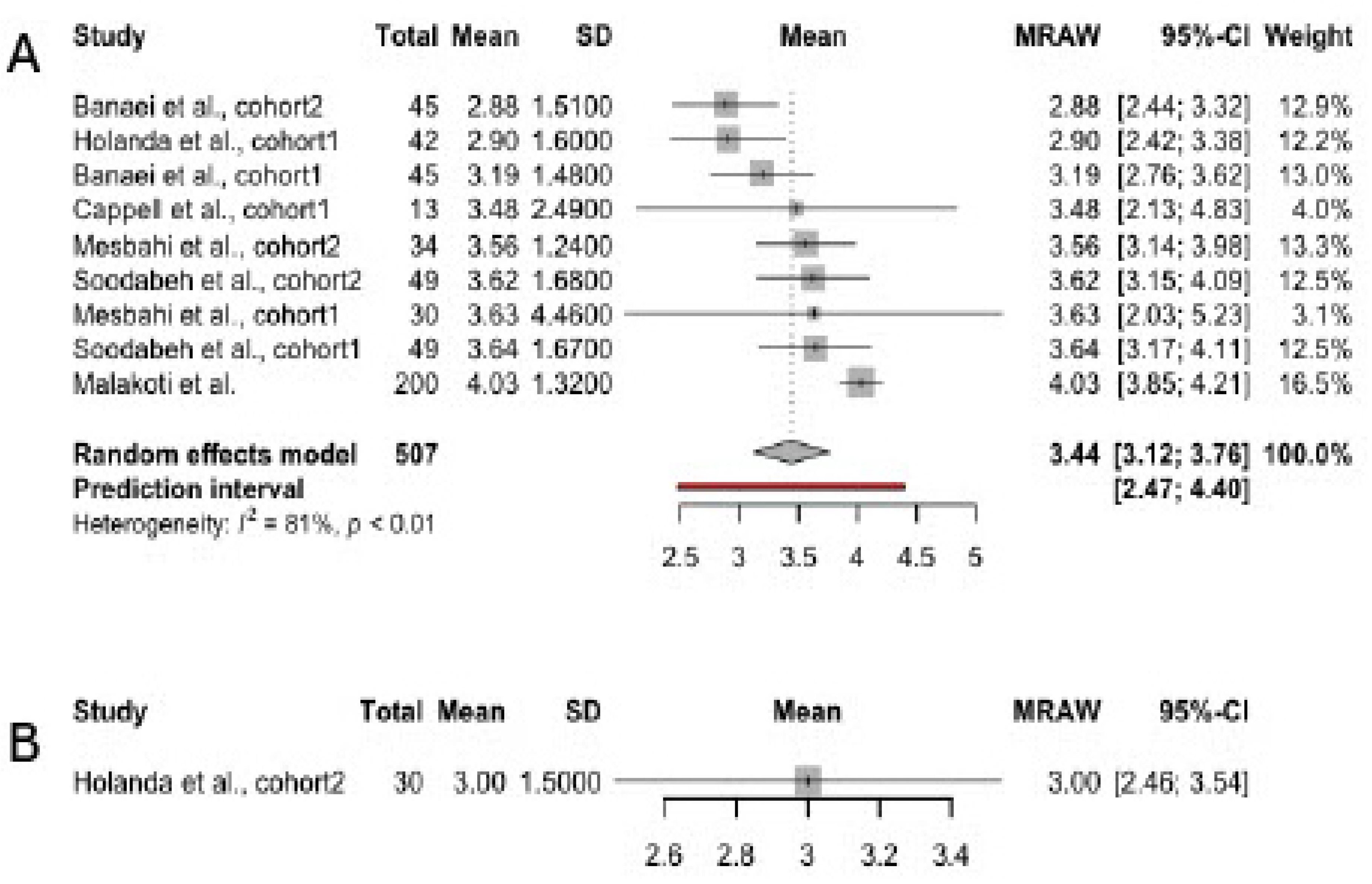

3.4.3. Orgasm

3.4.4. Lubrication

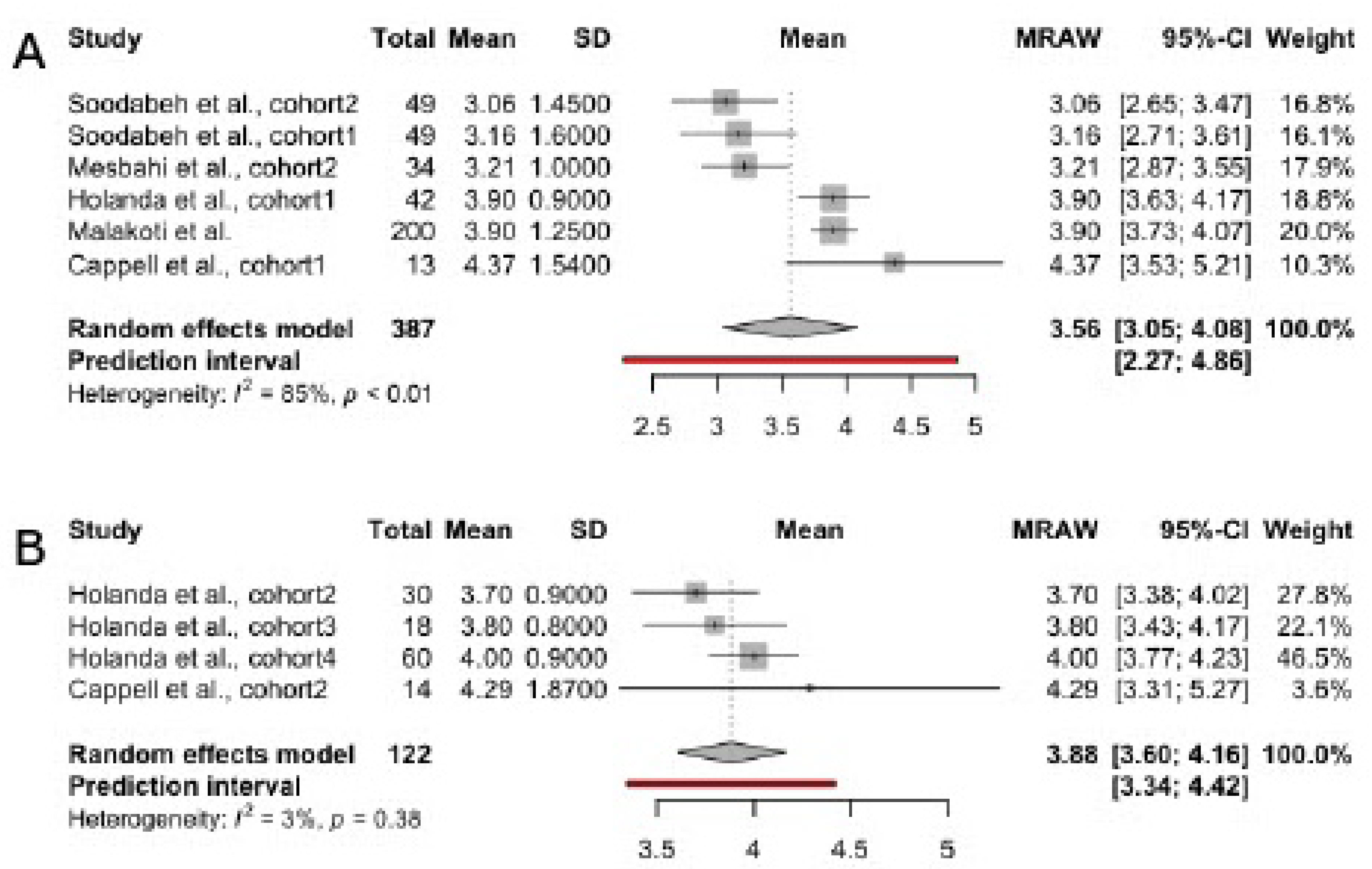

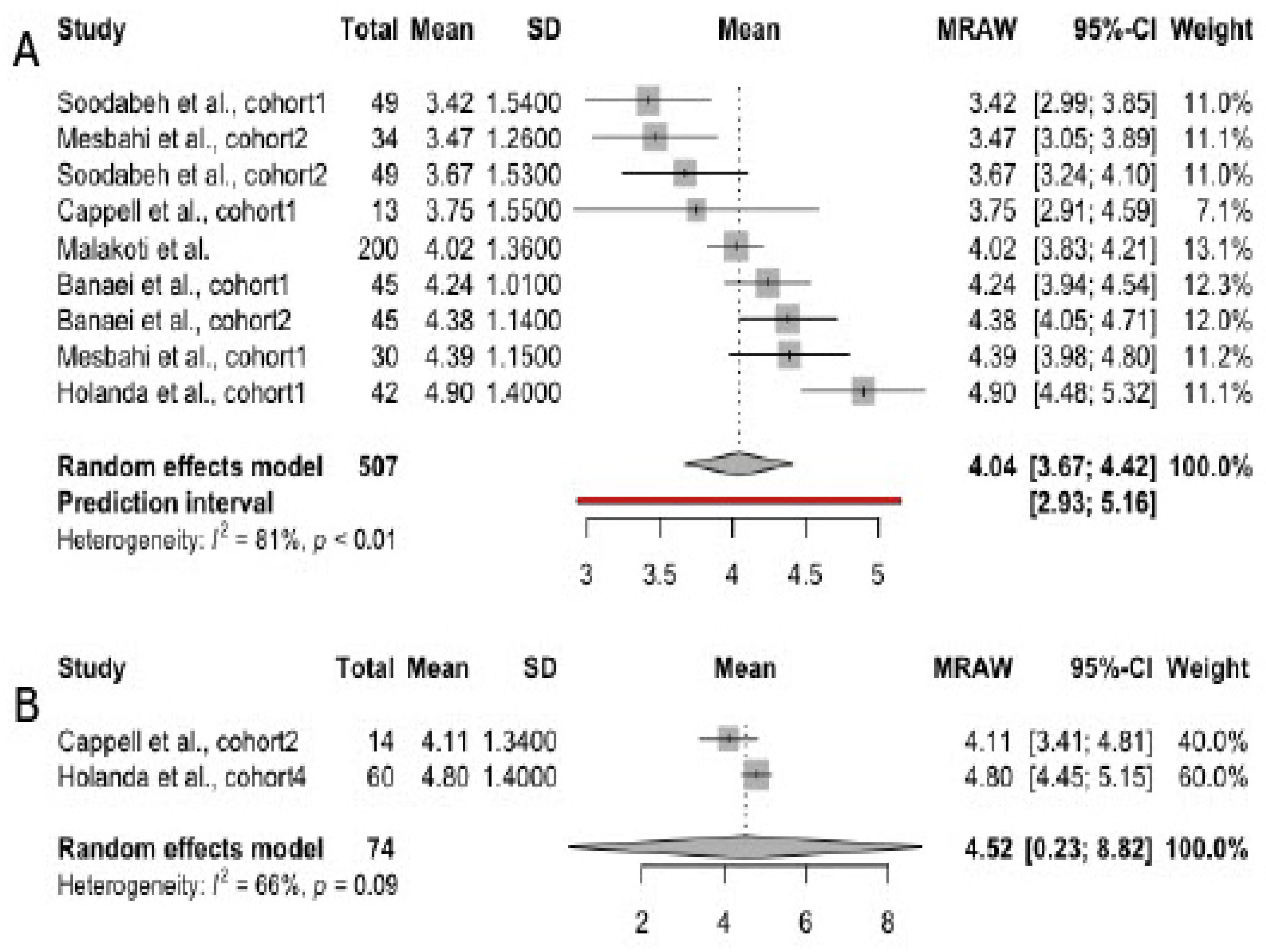

3.4.5. Pain

3.4.6. Satisfaction

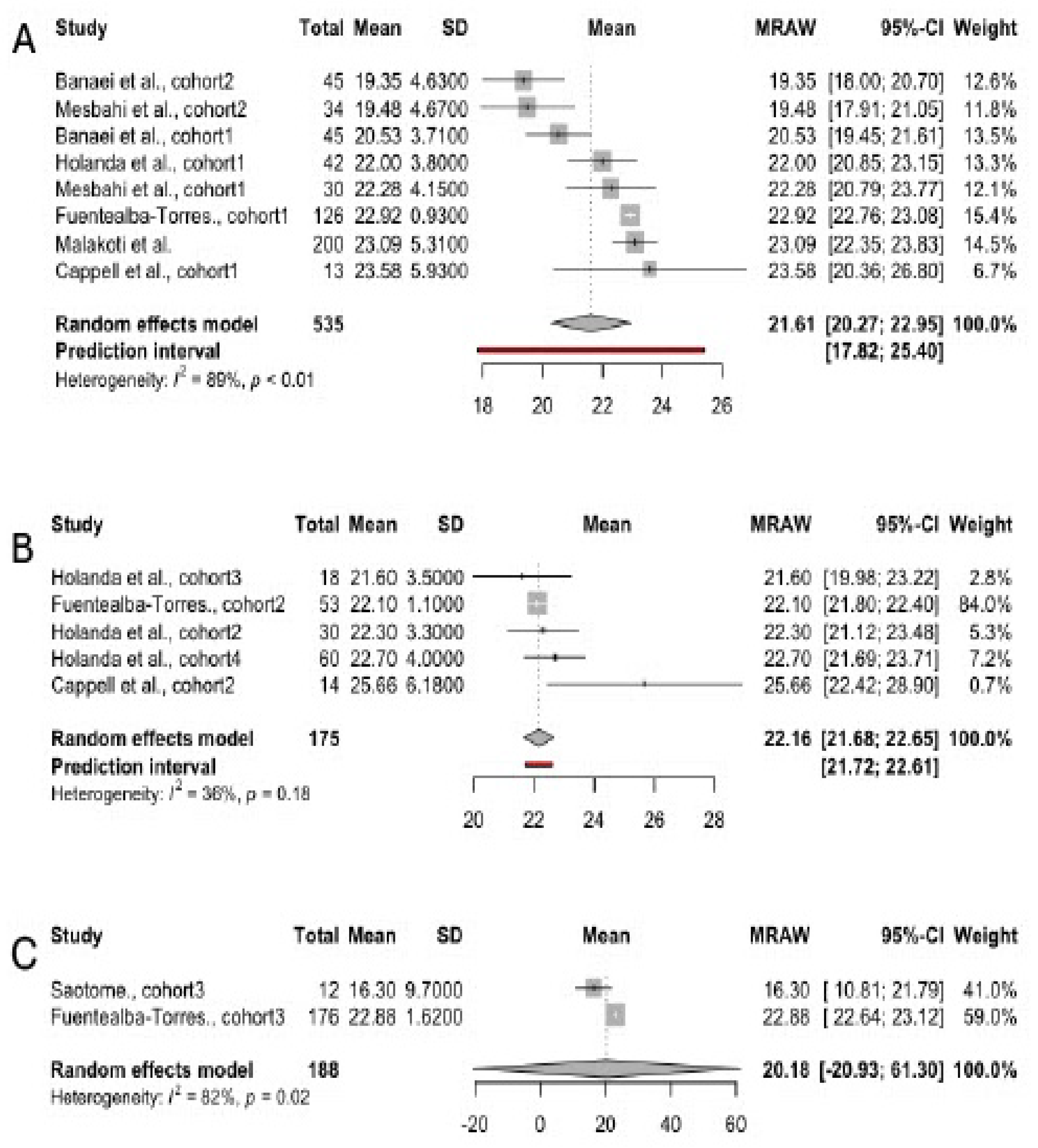

3.4.7. Overall Sexual Function

3.5. Description of Studies Included in a Systematic Review

3.6. Resumption of Sexual Intercourse

4. Discussion

Limitations

- The search strategy did not yield a sufficient number of publications reporting sexual dysfunctions among women resorting to bottle-feeding. Therefore, we did not calculate pooled scores in individual sexuality domains for this group of women.

- The initial analysis revealed a high heterogeneity index. To address significant between-study variability, we identified and removed outliers. Omitting studies with extreme values may reduce the generalisability of the study findings beyond the results of this work.

- Since the number of included studies was low, we could not adjust the findings for time since delivery. However, this information could provide valuable insight into the dynamics of sexual functioning in the postpartum period.

Strengths

- The work was prepared in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines and registered in the PROSPERO database.

- The research compiled aggregate scores across all areas of sexual functioning using the FSFI scale. Earlier systematic reviews and meta-analyses focused on overall sexual health data. Nevertheless, understanding changes within each domain is crucial for creating effective counseling approaches for couples expecting a baby.

- The FSFI scores were calculated separately for each type of feeding practice. The findings reflect a possible relationship between hormonal changes in lactating women and their sexual function postpartum.

- No significant publication biases were detected across the studies. The funnel plots were symmetric in all subgroups, indicating that the studies had similar effect sizes.

- The systematic review covered other possible changes in sexual health in breastfeeding females. The findings revealed a range of issues women face in the postpartum period that require attention from healthcare specialists.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Sexual Health and Well-Being. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research-(srh)/areas-of-work/sexual-health#:~:text=WHO%20defines%20sexual%20health%20as,of%20disease%2C%20dysfunction%20or%20infirmity (accessed on day month year).

- American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, 2013; p. 423; ISBN 0-89042-555-8.

- Aslan, E.; Fynes, M. Female Sexual Dysfunction. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2008, 19, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Skiba, M.A.; Bell, R.J.; Islam, R.M.; Davis, S.R. The Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunctions and Sexually Related Distress in Young Women: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, M.P.; Sharlip, I.D.; Lewis, R.; Atalla, E.; Balon, R.; Fisher, A.D.; Laumann, E.; Lee, S.W.; Segraves, R.T. Incidence and Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction in Women and Men: A Consensus Statement from the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine 2015. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolosi, A.; Laumann, E.O.; Glasser, D.B.; Moreira, E.D.; Paik, A.; Gingell, C. Sexual Behavior and Sexual Dysfunctions after Age 40: The Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Urology 2004, 64, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starc, A. Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction: A Cross-National Prevalence Study in Slovenia. Acta. Clin. Croat. 2018, 57, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, A. Female Sexual Dysfunction: Prevalence and Risk Factors. J. clin. diagn. res. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, N.N.; Jamani, N.A.; Abd Aziz, K.H.; Draman, N. The Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction among Postpartum Women on the East Coast of Malaysia. J. Taibah. Univ. Med. Sci. 2020, 15, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajehei, M.; Doherty, M.; Tilley, P.J.M.; Sauer, K. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Sexual Dysfunction in Postpartum Australian Women. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabiri, F.; Yabandeh, A.P.; Shahi, A.; Kamjoo, A.; Teshnizi, S.H. The Effect of Mode of Delivery on Postpartum Sexual Functioning in Primiparous Women. Oman. Med. J. 2014, 29, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentealba-Torres, M.; Cartagena-Ramos, D.; Fronteira, I.; Lara, L.A.; Arroyo, L.H.; Arcoverde, M.A.M.; Yamamura, M.; Nascimento, L.C.; Arcêncio, R.A. What Are the Prevalence and Factors Associated with Sexual Dysfunction in Breastfeeding Women? A Brazilian Cross-Sectional Analytical Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouéta, F.; Dao, L.; Dao, F.; Djekompté, S.; Sawadogo, J.; Diarra, Y.; Kam, K.L.; Sawadogo, A. Factors Associated with Overweight and Obesity in Children in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). Cahiers Santé 2011, 21, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaei, M.; Moridi, A.; Dashti, S. Sexual Dysfunction and Its Associated Factors After Delivery: Longitudinal Study in Iranian Women. Mater. Sociomed. 2018, 30, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Malley, D.; Higgins, A.; Smith, V. Exploring the Complexities of Postpartum Sexual Health. Curr. Sex. Health. Rep. 2021, 13, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A.; Fallahi, A.; Allahqoli, L.; Grylka-Baeschlin, S.; Alkatout, I. How Do New Mothers Describe Their Postpartum Sexual Quality of Life? A Qualitative Study. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buster, J.E. Managing Female Sexual Dysfunction. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutzeit, O.; Levy, G.; Lowenstein, L. Postpartum Female Sexual Function: Risk Factors for Postpartum Sexual Dysfunction. Sex. Med. 2020, 8, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florkiewicz-Danel, M.; Zaręba, K.; Ciebiera, M.; Jakiel, G. Quality of Life and Sexual Satisfaction in the Early Period of Motherhood-A Cross-Sectional Preliminary Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clephane, K.; Lorenz, T.K. Putative Mental, Physical, and Social Mechanisms of Hormonal Influences on Postpartum Sexuality. Curr. Sex. Health. Rep. 2021, 13, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, R.; Santoro, N.; Miller, K.K.; Parish, S.J.; Davis, S.R. Hormones and Female Sexual Dysfunction: Beyond Estrogens and Androgens—Findings From the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, R.E.; Di Ciaccio, S.; Genazzani, A.D. Prolactin as a Neuroendocrine Clue in Sexual Function of Women across the Reproductive Life Cycle: An Expert Point of View. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2021, 37, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, H.A.; James, T.W.; Ketterson, E.D.; Sengelaub, D.R.; Ditzen, B.; Heiman, J.R. Lower Sexual Interest in Postpartum Women: Relationship to Amygdala Activation and Intranasal Oxytocin. Horm. Behav. 2013, 63, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, H.L.; Olson, S.; Kwee, J.; Klein, C.; Smith, K. Women’s Postpartum Sexual Health Program: A Collaborative and Integrated Approach to Restoring Sexual Health in the Postpartum Period. J. Sex. Marital. Ther. 2017, 43, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alligood-Percoco, N.R.; Kjerulff, K.H.; Repke, J.T. Risk Factors for Dyspareunia After First Childbirth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alp Yılmaz, F.; Şener Taplak, A.; Polat, S. Breastfeeding and Sexual Activity and Sexual Quality in Postpartum Women. Breastfeed. Med. 2019, 14, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M.; Merghati Khoei, E.; Kiani Asiabar, A.; Khoei, E.M.; Heidari, M. What Happens To Sexuality Of Women During Lactation Period? A Study From Iran. PaK. J. Med. Sci. 2009, 25, 938–943. [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Sagie, A.; Amsalem, H.; Gutman, Y.; Esh-Broder, E.; Daum, H. Prevalence and Characteristics of Postpartum Vulvovaginal Atrophy and Lack of Association With Postpartum Dyspareunia. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2020, 24, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameshwaran, S.; Chandra, P.S. The New Avatar of Female Sexual Dysfunction in ICD-11—Will It Herald a Better Future? J. Psychosexual Health 2019, 1, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grussu, P.; Vicini, B.; Quatraro, R.M. Sexuality in the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Recommendations for Practice. Sex. Reprod. Health 2021, 30, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neijenhuijs, K.I.; Hooghiemstra, N.; Holtmaat, K.; Aaronson, N.K.; Groenvold, M.; Holzner, B.; Terwee, C.B.; Cuijpers, P.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)—A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triviño-Juárez, J.; Romero-Ayuso, D.; Nieto-Pereda, B.; Forjaz, M.J.; Oliver-Barrecheguren, C.; Mellizo-Díaz, S.; Avilés-Gámez, B.; Arruti-Sevilla, B.; Criado-Álvarez, J.; Soto-Lucía, C.; et al. Resumption of Intercourse, Self-reported Decline in Sexual Intercourse and Dyspareunia in Women by Mode of Birth: A Prospective Follow-up Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, E.; Gartland, D.; Small, R.; Brown, S. Dyspareunia and Childbirth: A Prospective Cohort Study. BJOG 2015, 122, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices Definitions and Measurement Methods. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240018389 (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Smetanina, D.; Awar, S. Al; Khair, H.; Alkaabi, M.; Das, K.M.; Ljubisavljevic, M.; Statsenko, Y.; Zaręba, K.T. Risk of Sexual Dysfunctions in Breastfeeding Females: Protocol for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e074630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porritt, K.; Gomersall, J.; Lockwood, C. JBI’s Systematic Reviews. AJN, Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghababaei, S.; Refaei, M.; Roshanaei, G.; Rouhani Mahmoodabadi, S.M.; Heshmatian, T. The Effect of Sexual Health Counseling Based on REDI Model on Sexual Function of Lactating Women with Decreased Sexual Desire. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaei, M.; Torkzahrani, S.; Ozgoli, G.; Azad, M.; Mahmoudikohani, F.; PormehrYabandeh, A. Addressing the Sexual Function of Women During First Six Month After Delivery: Aquasi-Experimental Study. Mater. Sociomed. 2018, 30, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakoti, J.; Zamanzadeh, V.; Maleki, A.; Farshbaf Khalili, A. Sexual Function in Breastfeeding Women in Family Health Centers of Tabriz, Iran, 2012. J. Caring. Sci. 2013, 2, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesbahi, A.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S.; Ghorbani, Z.; Mirghafourvand, M. The Effect of Intra-Vaginal Oxytocin on Sexual Function in Breastfeeding Mothers: A Randomized Triple-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holanda, J.B. de L.; Richter, S.; Campos, R.B.; Trindade, R.F.C. da; Monteiro, J.C. dos S.; Gomes-Sponholz, F.A. Relationship of the Type of Breastfeeding in the Sexual Function of Women. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2021; 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappell, J.; Bouchard, K.N.; Chamberlain, S.M.; Byers-Heinlein, A.; Chivers, M.L.; Pukall, C.F. Is Mode of Delivery Associated With Sexual Response? A Pilot Study of Genital and Subjective Sexual Arousal in Primiparous Women With Vaginal or Cesarean Section Births. J. Sex. Med. 2020, 17, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saotome, T.T.; Yonezawa, K.; Suganuma, N. Sexual Dysfunction and Satisfaction in Japanese Couples During Pregnancy and Postpartum. Sex. Med. 2018, 6, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alum, A.C.; Kizza, I.B.; Osingada, C.P.; Katende, G.; Kaye, D.K. Factors Associated with Early Resumption of Sexual Intercourse among Postnatal Women in Uganda. Reprod. Health. 2015, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, D.; Higgins, A.; Begley, C.; Daly, D.; Smith, V. Prevalence of and Risk Factors Associated with Sexual Health Issues in Primiparous Women at 6 and 12months Postpartum; A Longitudinal Prospective Cohort Study (the MAMMI Study). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rådestad, I.; Olsson, A.; Nissen, E.; Rubertsson, C. Tears in the Vagina, Perineum, Sphincter Ani, and Rectum and First Sexual Intercourse after Childbirth: A Nationwide Follow-Up. Birth 2008, 35, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, N.; Azadi, A.; Sayehmiri, K.; Valizadeh, R. Postpartum Sexual Functioning and Its Predicting Factors among Iranian Women. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 24, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, N.O.; Dawson, S.J.; Binik, Y.M.; Pierce, M.; Brooks, M.; Pukall, C.; Chorney, J.; Snelgrove-Clarke, E.; George, R. Trajectories of Dyspareunia From Pregnancy to 24 Months Postpartum. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 139, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamon, N.; Mohd Hashim, S.; Ahmad, N.; Wahab, S.; Malaysia, K.; Yaakob Latiff, J.; Tun Razak, B.; Lumpar, K.; Kesihatan Bandar Miri, K.; Kesihatan Malaysia, K. Sexual Dysfunction Among Women At Four To Six Months Postpartum: A Study In A Primary Care Setting. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2020, 20, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorello, L.B.; Harlow, B.L.; Chekos, A.K.; Repke, J.T. Postpartum Sexual Functioning and Its Relationship to Perineal Trauma: A Retrospective Cohort Study of Primiparous Women. In Proceedings of the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology; Mosby Inc., 2001; Vol. 184, pp. 881–890.

- Triviño-Juárez, J.M.; Romero-Ayuso, D.; Nieto-Pereda, B.; Forjaz, M.J.; Oliver-Barrecheguren, C.; Mellizo-Díaz, S.; Avilés-Gámez, B.; Arruti-Sevilla, B.; Criado-Álvarez, J.J.; Soto-Lucía, C.; et al. Resumption of Intercourse, Self-Reported Decline in Sexual Intercourse and Dyspareunia in Women by Mode of Birth: A Prospective Follow-up Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C.; Smith, J.P. The Visibility of Breastfeeding as a Sexual and Reproductive Health Right: A Review of the Relevant Literature. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Hamilton, F.; Dieter, A.A.; Budd, S.; Getaneh, F. The Effect of Breastfeeding on Postpartum Sexual Function: An Observational Cohort Study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canul-Medina, G.; Fernandez-Mejia, C. Morphological, Hormonal, and Molecular Changes in Different Maternal Tissues during Lactation and Post-Lactation. J. Physiol. Sci. 2019, 69, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariman, A.; Hanoulle, I.; Pevernagie, D.; Maertens, S.-J.; Dehaene, I.; Tobback, E.; Delesie, L.; Loccufier, A.; Van Holsbeeck, A.; Moons, L.; et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Sleep and Fatigue According to Baby Feeding Method in Postpartum Women: A Prospective Observational Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayner, C.E.; Zagar, J.A. Breast-Feeding and Sexual Response. J Fam Pract 1983, 17, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Basson, R. The Female Sexual Response: A Different Model. .J Sex. Marital. Ther. 2000, 26, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brotto, L.A.; Bitzer, J.; Laan, E.; Leiblum, S.; Luria, M. Women’s Sexual Desire and Arousal Disorders. J. Sex. Med. 2010, 7, 586–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battin, D.A.; Marrs, R.P.; Fleiss, P.M.; Mishell, D.R. Effect of Suckling on Serum Prolactin, Luteinizing Hormone, Follicle-Stimulating Hormone, and Estradiol during Prolonged Lactation. Obstet. Gynecol. 1985, 65, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pascoal, P.M.; Narciso, I. de S.B.; Pereira, N.M. What Is Sexual Satisfaction? Thematic Analysis of Lay People’s Definitions. J. Sex. Res. 2014, 51, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Józefacka, N.M.; Szpakiewicz, E.; Lech, D.; Guzowski, K.; Kania, G. What Matters in a Relationship—Age, Sexual Satisfaction, Relationship Length, and Interpersonal Closeness as Predictors of Relationship Satisfaction in Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2023, 20, 4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Kim, J.; Korst, L.M.; Hughes, C.L. Application of the Estrogen Threshold Hypothesis to the Physiologic Hypoestrogenemia of Lactation. Breastfeed. Med. 2015, 10, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, year | Country | Total sample size | Patient’s age | Time since delivery | Breastfeeding type | Studied FSFI domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soodabeh et al., 2020 [37] | Iran | 98 | 29.65±5.66 | 4.12±1.61 months | Exclusive | Total; Libido (desire); Arousal; Lubrication; Orgasm; Satisfaction; Pain |

| Banaei et al., 2018 [38] | Iran | 87 | 24.93±3.10 in the intervention group; 23.44±2.64 in the control group |

3.56±1.58 months in the intervention group; 3.56±1.80 months in the control group; |

Exclusive |

Total; Desire; Arousal; Lubrication; Orgasm; Satisfaction; Pain |

| Cappell et al., 2020 [42] | Canada | 27 | 31.45±4.35 | 310.26± 204.26 days | Exclusive; Not exclusive |

Total; Desire; Arousal; Lubrication; Orgasm; Satisfaction; Pain |

| Fuentealba-Torres et al., 2019[12] | Brazil | 355 | 26.5±6.68 | N/A | Exclusive; Predominant; Complimentary |

Total |

| Holanda et al., 2021 [41] | Brazil | 150 | 24.8±6.4 | 4.3±1.2 | Exclusive; Predominant; Complimented; Mixed | Total; Desire; Arousal; Lubrication; Orgasm; Satisfaction; Pain |

| Malakoti et al. 2013 [39] | Iran | 200 | 27.5±5.2 | 3-6 months | Exclusive | Total; Desire; Arousal; Lubrication; Orgasm; Satisfaction; Pain |

| Mesbahi et al., 2022 [40] | Iran | 64 | 31.2±5.1 in intervention group; 27.8±5.9 in control group | 4.18±1.88 months in intervention group; 3.87± 1.72 in control group | Exclusive | Total; Desire; Arousal; Lubrication; Orgasm; Satisfaction; Pain |

| Saotome et al., 2018 [43] | Japan | 84 | 32.8±4.4 | N/A | Exclusive; mixed; formula | Total |

| Author, year | Country | Sample size | Age of participants | Time since delivery | Target condition | Feeding practice | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alum et al., 2015 [44] | Uganda | 374 | Between 15 to 45 | N/A |

Resumption of sexual intercourse after 6 weeks. | Any type of breastfeeding vs. artificial feeding; Exclusive vs. non-exclusive breastfeeding. |

21.6% of participants resumed intercourse within 6 weeks after giving birth. The early resumption of intercourse was associated with socio-economic factors. |

| Heidari et al., 2009 [27] | Iran | 456 | Between 20 to 35 | 2 – 6 months | Resumption of sexual intercourse after 6 weeks; reduced desire; reduced satisfaction; Not experiencing orgasm. |

Breastfeeding vs. bottle-feeding. | Breastfeeding and bottle-feeding women did not have a significant difference in sexual health postpartum. |

| Lev-Sagie et al., 2020[28] | Israel | 329 | Between 23 to 40 | 3 – 16 weeks | Vulvovaginal atrophy. | Breastfeeding vs. non-breastfeeding (not specified) | Vulvovaginal atrophy was associated with breastfeeding status. |

| O’Malley et al., 2018 [15] | Ireland | 832 | 18 and above | 6 and 12 months | Lack of vaginal lubrication; Loss of interest in sexual activity. |

Breastfeeding vs. non-breastfeeding (not specified). | Breastfeeding and pre-existing dyspareunia were risk factors for issues in sexual health at 6 months postpartum. |

| Radestad et al., 2008 [46] | Sweden | 2342 | 15 and above | 12 months | Intercourse at: over 3 and over 6 months after giving birth. | Breastfeeding at 2 months and 6 months vs. not breastfeeding (not specified). | Breastfeeding women had 1.6 OR of resuming intercourse at over 3 months postpartum. |

| Rezaei et al., 2017[47] | Iran | 380 | 18 and above | 3 – 5 months | Total FSFI score. | Exclusive breastfeeding. |

Exclusive breastfeeding was significantly associated with sexual dysfunction (adjusted OR: 2.47, 95% CI: 1.21 – 5.03). |

| Rosen et al., 2022 [48] | Canada | 582 | 29±4.4 | Up to 2 years | Change from moderate to minimal dyspareunia. | Breastfeeding at 3 months (not specified). | Breastfeeding did not predict a dyspareunia class. |

| Salamon et al., 2020 [49] | Malaysia | 249 | 28.99±6.07 | 4 – 6 months | Overall sexual dysfunction | Breastfeeding (not specified). | Breastfeeding was a risk factor for sexual dysfunction (adjusted OR: 2.24, 95% CI: 1.03 – 4.85). |

| Signorello et al., 2001 [50] | USA | 615 | N/A | 8.1±3.5 weeks; 3 months; 6 months | Pain at the first postpartum sexual intercourse; Pain on sexual intercourse at 3 and 6 months postpartum. | Breastfeeding vs. non-breastfeeding (not specified). | Breastfeeding women were 4 times as likely to experience dyspareunia compared to non-breastfeeding mothers. |

| Triviño-Juárez et al., [51] | Spain | 552 | 32.18±5.36 | 6 weeks | Resumption of sexual intercourse at 6 weeks;Decline in sexual intercourse. | Breastfeeding (not specified). | Breastfeeding was a determinant of dyspareunia. However, nursing was not linked to the resumption of intercourse or a decline in sexual activity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).