Submitted:

07 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundation and Hypotheses

2.1. The Essence and Concept of Industry 5.0

2.2. The Level of Awareness Among Enterprises Regarding the Implementation of Industry 5.0 Principles

2.3. Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

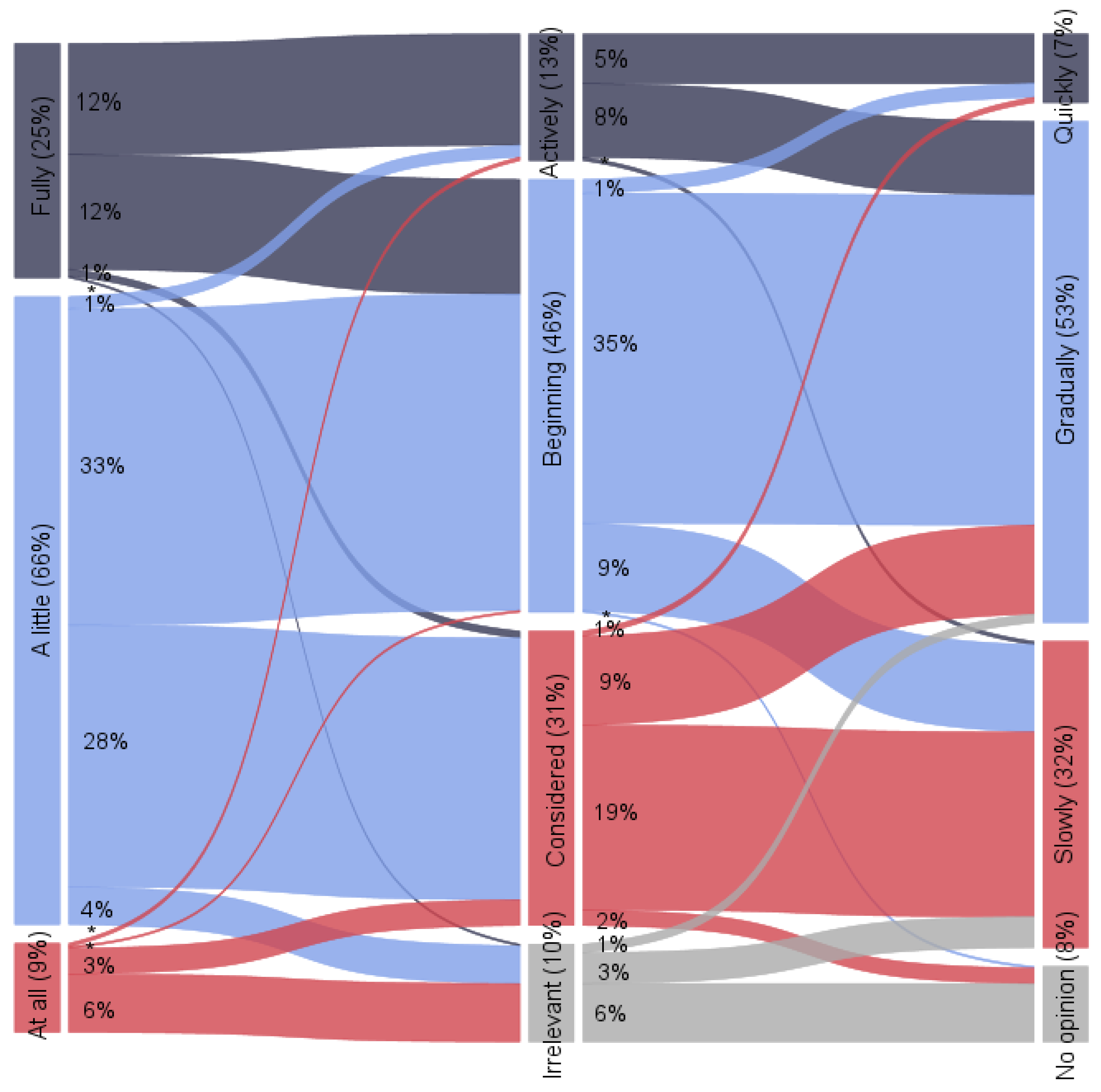

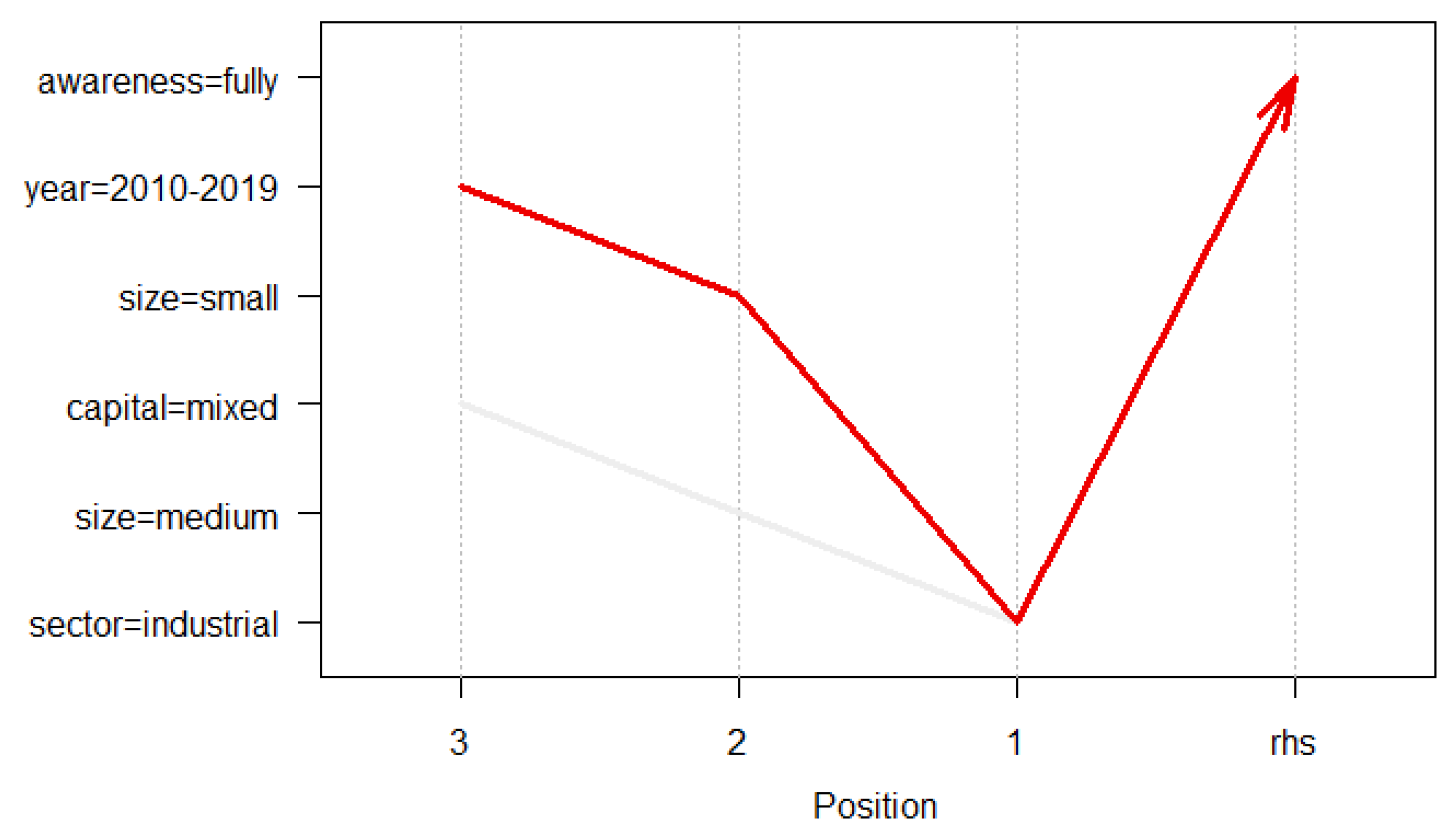

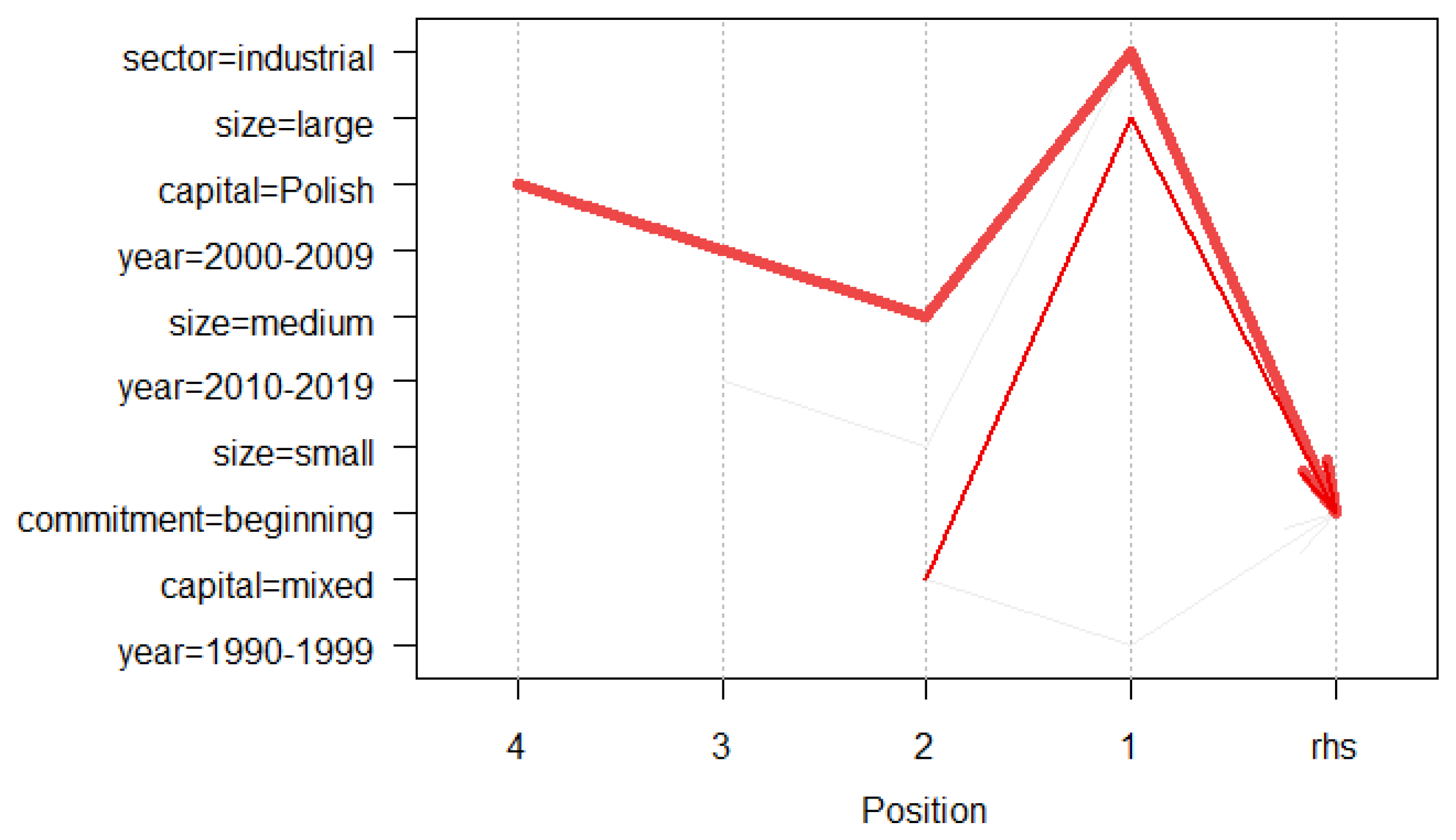

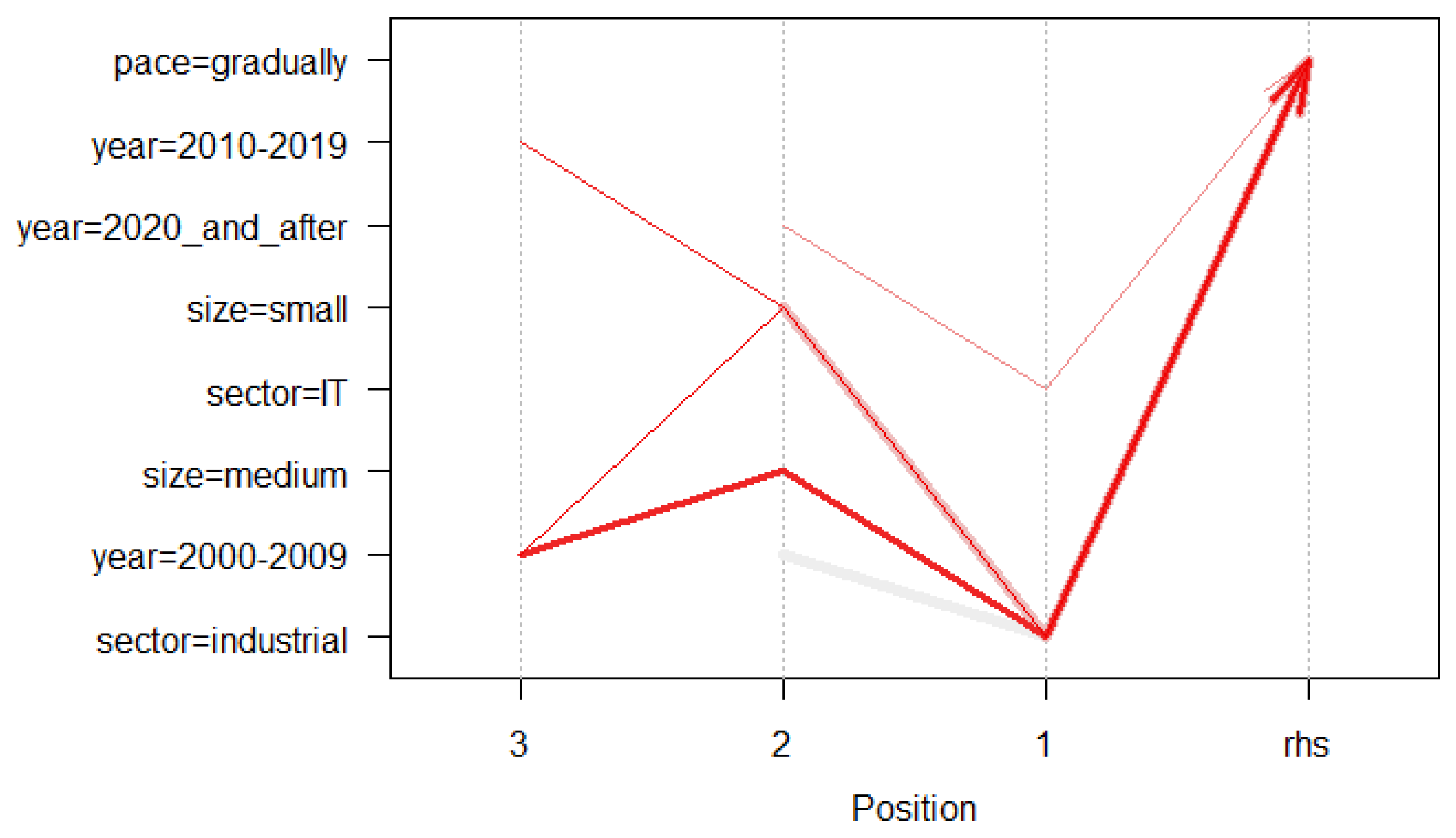

4.2. Awareness, Commitment, and Pace of Implementation of Industry 5.0

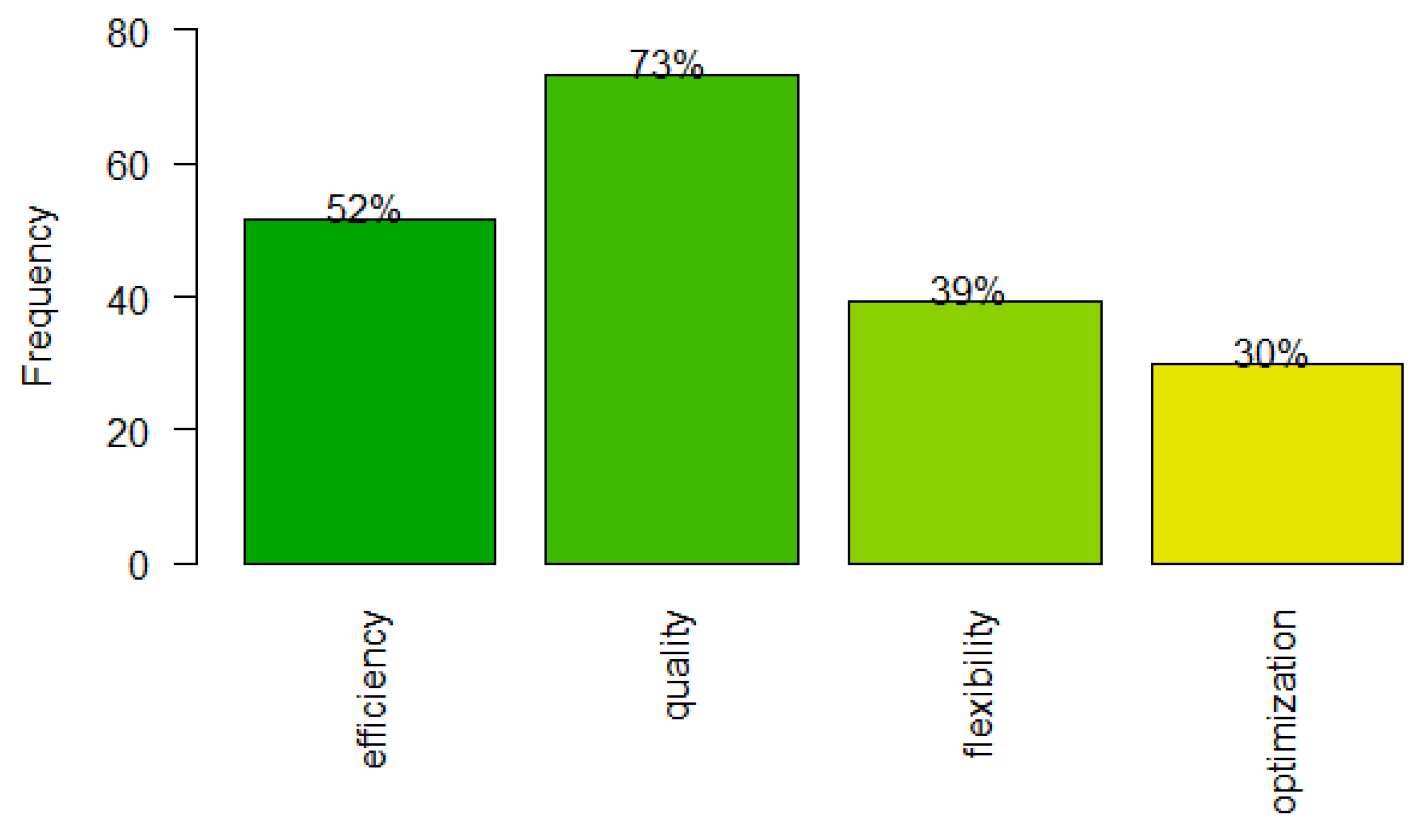

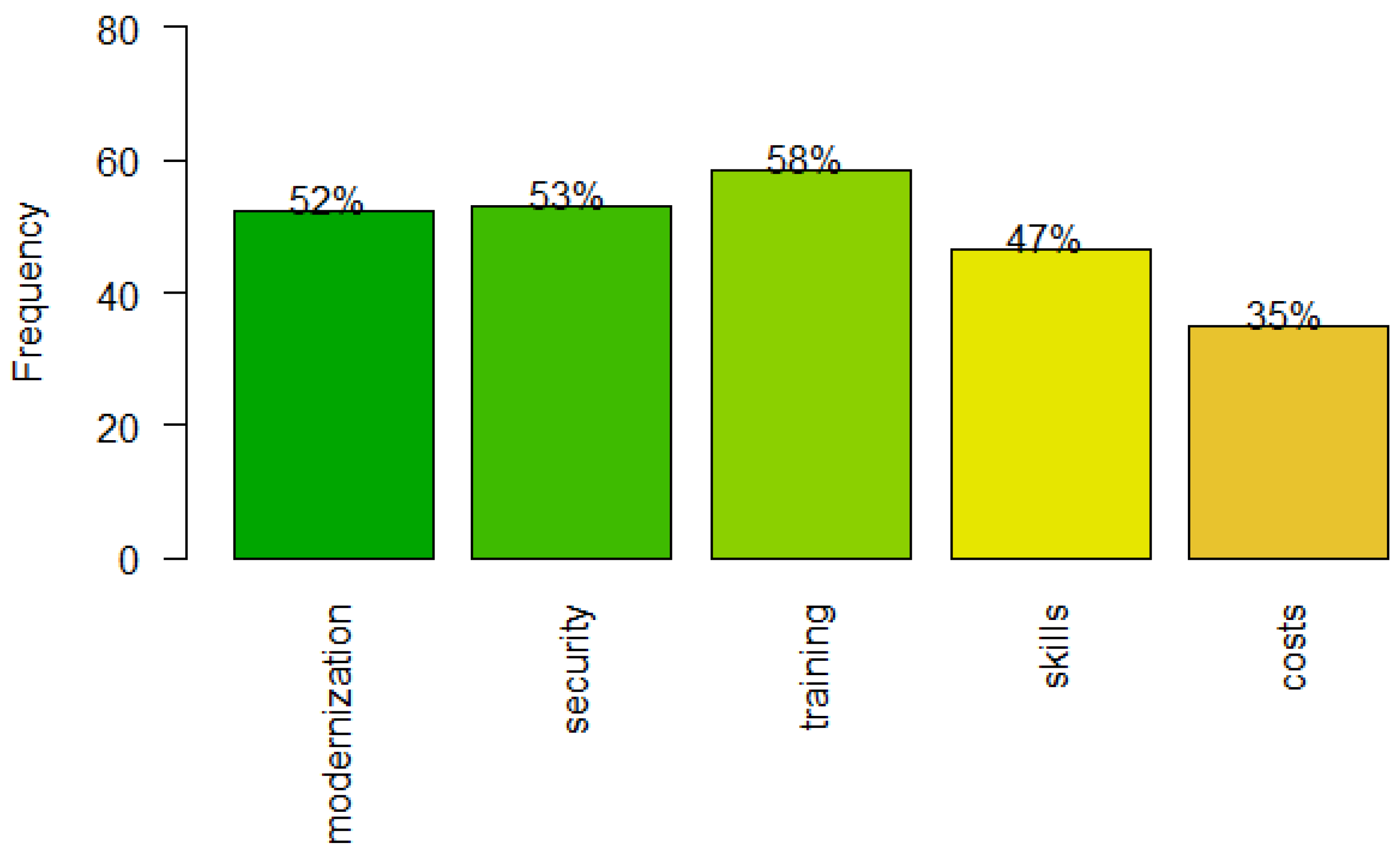

4.3. Benefits and Challenges

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

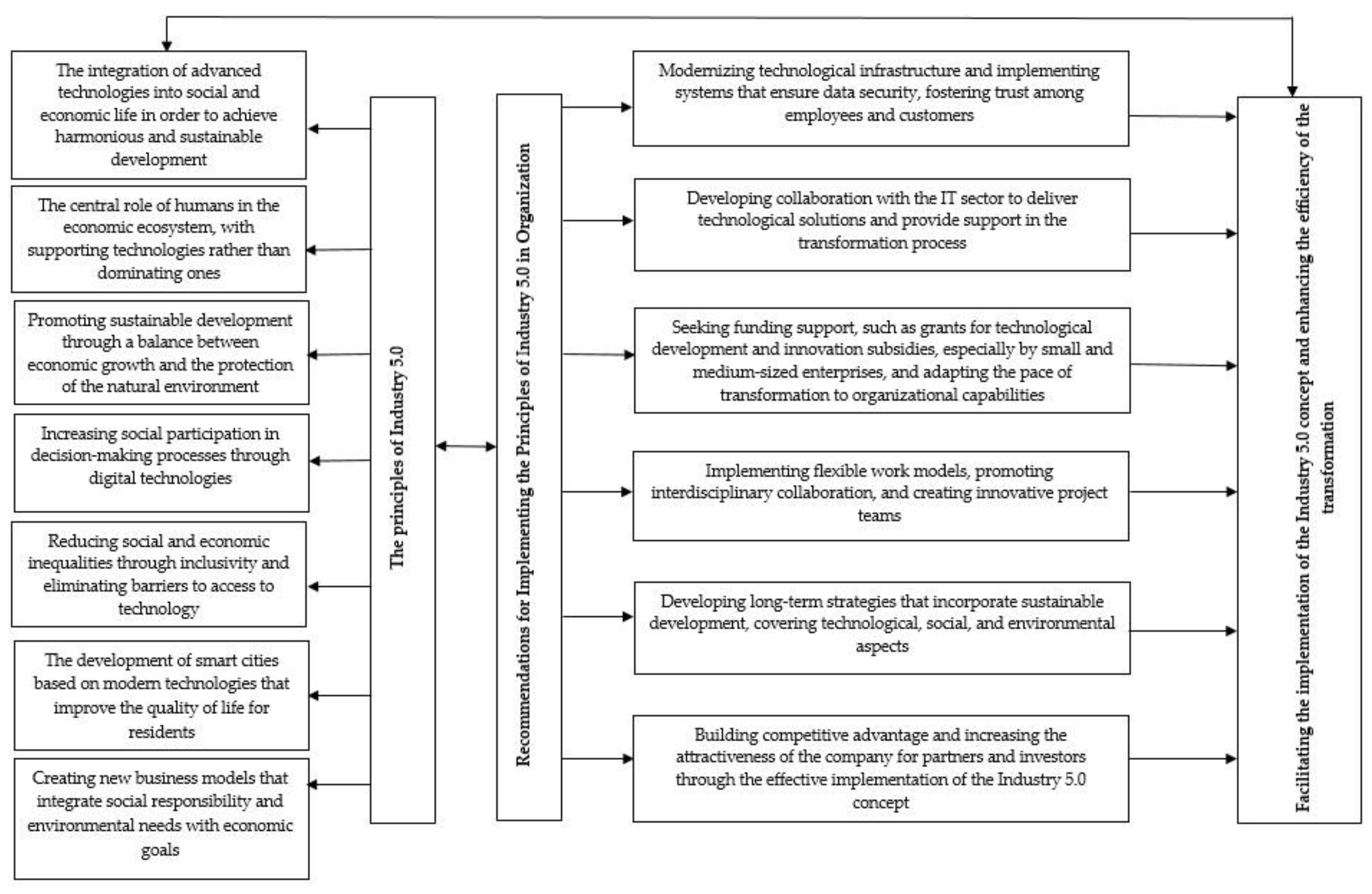

5.2. Theoretical Model

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maciejewski, R.; Knast, P. Podstawy teoretyczne i praktyczne rewolucji przemysłowej 4.0 i 5.0. Fundacja na rzecz Czystej Energii 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Kim, Y. Technologiczne innowacje i transformacje społeczne w kontekście Gospodarki 5.0. In Nowe horyzonty: Perspektywy na przyszłość gospodarki; Park, S., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Alfa, 2024; pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, K. The fourth industrial revolution; Crown Currency, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2018, https://psipp.itb-ad.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Francis-Fukuyama-Identity_-The-Demand-for-Dignity-and-the-Politics-of-Resentment-0-Farrar-Straus-and-Giroux.pdf.

- Schneider, R.; Smith, J. Gospodarka 5.0: Nowy paradygmat zarządzania zasobami w erze cyfrowej. Journal of Economic Studies 2023, 10, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tawalbeh, L.a.; Muheidat, F.; Tawalbeh, M.; Quwaider, M. IoT privacy and security: challenges and solutions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moczydłowska J., M. Przemysł 4.0-Ludzie i technologie; Difin: Warszawa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Graczyk, M.; Stec, A. Blockchain technology in logistics and supply chain management. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Borzemski, L., Grzech, A., Świątek, J., Eds.; Springer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; West, J. (Eds.) New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Oxford University Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, K.; Makaju, S.; Ibrahim, R.; Missaoui, A. Current progress in nitrogen fixing plants and microbiome research. Plants 2020, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, P. Financial decisions based on zero-sum games: New conceptual and mathematical outcomes. International Journal of Financial Studies 2024, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, V.; Jackson-Nevels, B.; Reddy, V.V. Social, cultural, and economic determinants of well-being. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1183–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Jeong, S.; Moon, M.; Kim, D. Analysis of the dynamic behavior of multi-layered soil grounds. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keidanren, N. Toward Realization of the New Economy and Society. Reform of the Economy and Society by the Deepening of Society, 2016, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lasi, H.; Fettke, P.; Kemper, H.-G.; Feld, T.; Hoffmann, M. Industry 4.0. Business & Information Systems Engineering 2014, 6, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojko, A. Industry 4.0 concept: Background and overview. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies 2017, 11, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.D.; Xu, E.L.; Li, L. Industry 4.0: State of the art and future trends. International Journal of Production Research 2018, 56, 2941–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Industry 4.0: A survey on technologies, applications and open research issues. Journal of Industrial Information Integration 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Wang, X.; Hu, C.; Li, X. Rapid and high-performance analysis of total nitrogen in coco-peat substrate by coupling laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy with multi-chemometrics. Agriculture 2024, 14, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Quintero, J.C.; Yang, Z.; Ono, K. Assessment of user preferences for in-car display combinations during non-driving tasks: An experimental study using a virtual reality head-mounted display prototype. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2024, 15, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Imieliński, T.; Swami, A. Mining association rules between sets of items in large databases; SIGMOD Rec. 22, 2 June 1; 1993; pp. 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayardo, R.J.; Agrawal, R.; Gunopulos, D. Constraint-Based Rule Mining in Large, Dense Databases. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2010, 4, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, F.; Josse, J.; Pagès, J. Principal Component Methods Hierarchical Clustering Partitional Clustering: Why Would We Need to Choose for Visualizing Data? Unpublished Data. 2010.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Hahsler, M.; Buchta, C.; Gruen, B.; Hornik, K. arules: Mining Association Rules and Frequent Itemsets. R package version 1.7-8, 2024, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=arules.

- Hahsler, M. ArulesViz: Visualizing Association Rules and Frequent Itemsets. R package version 1.5.3. 2024. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=arulesViz.

- IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 29.0.2.0; Armonk, NY, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- SAP Polska. Jakie trendy będą napędzać biznes w 2024 roku? 2024. Available online: https://news.sap.com/poland/2024/01/jakie-trendy-beda-napedzac-biznes-w-2024-roku-dane-i-prognozy-sap/.

- Forbes Polska. Przemysł 4.0 i przemysł 5.0 zmieniają polską gospodarkę, 2024. Available online: https://www.forbes.pl/technologie/przemysl-40-i-przemysl-50-zmieniaja-polska-gospodarka/xzqbjmy.

- ElektroOnline. Przemysł 5.0 w Polsce – czy dogonimy Europę? 2024. Available online: https://elektroonline.pl/news/12402%2CPrzemysl-50-w-Polsce-czy-dogonimy-Europe.

- EY Polska. Business 5.0 – następny krok w biznesowej transformacji firm, 2024. Available online: https://www.ey.com/pl_pl/insights/consulting/business-5-0-nastepny-krok.

| Variable | Category | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sector | banking/finance | 18.5 |

| IT | 21.9 | |

| automotive | 20.0 | |

| industrial | 18.3 | |

| service | 21.2 | |

| Size | 10-49 employees (small) | 69.6 |

| 50-249 employees (medium) | 21.2 | |

| 250 and more employees (large) | 9.2 | |

| 1989 and before | 8.1 | |

| Year | 1990-1999 | 18.0 |

| 2000-2009 | 31.3 | |

| 2010-2019 | 36.0 | |

| 2020 and after | 6.7 | |

| Capital | Polish | 89.4 |

| foreign | 4.0 | |

| mixed | 6.7 |

| Variables | p-value | df |

|---|---|---|

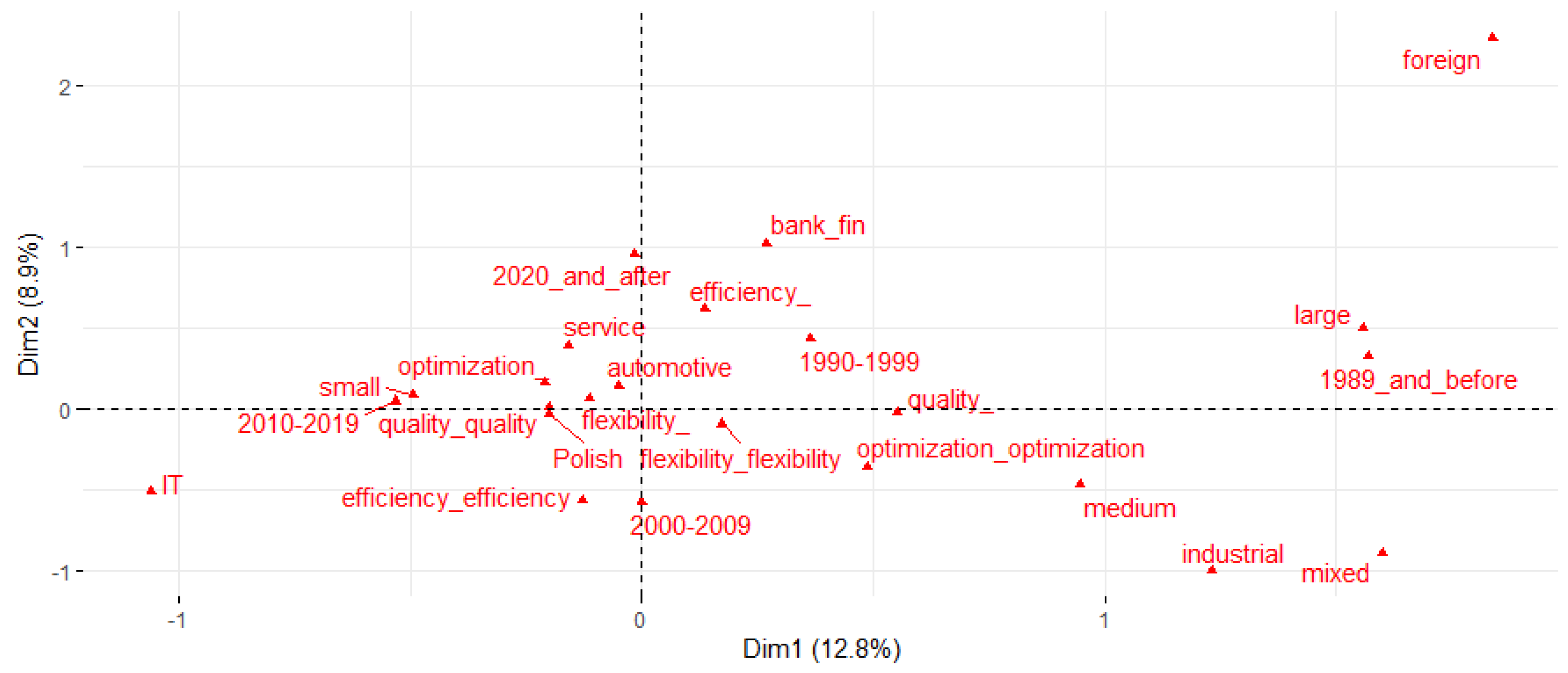

| sector | <0.001 | 8 |

| size | <0.001 | 4 |

| efficiency | <0.001 | 2 |

| capital | <0.001 | 4 |

| year | <0.001 | 8 |

| optimization | <0.001 | 2 |

| quality | <0.001 | 2 |

| flexibility | <0.001 | 2 |

| Cluster | Cla/Mod | Mod/Cla | p-value | v-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cluster 1 sector=IT size=small efficiency=efficiency_efficiency optimization=optimization_ year=2010-2019 capital=Polish quality=quality_quality flexibility=flexibility_ |

91.803 34.884 40.070 34.134 41.000 27.364 28.922 29.080 |

82.353 99.265 84.559 91.912 60.294 100.000 86.765 72.059 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.002 |

18.975 10.125 9.152 6.935 6.668 5.596 4.233 3.172 |

|

Cluster 2 sector=service efficiency=efficiency_ sector=automotive size=small capital=Polish sector=bank_fin year=1990-1999 |

95.763 73.234 79.279 58.398 54.125 67.961 62.000 |

40.357 70.357 31.426 80.714 96.071 25.000 22.143 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.010 |

12.028 10.591 6.952 5.759 5.266 3.970 2.564 |

|

Cluster 3 sector=industrial size=large size=medium capital=mixed year=1989_and_before optimization=optimization_optimization capital=foreign flexibility=flexibility_flexibility efficiency=efficieny_efficiency quality=quality_ |

92.157 86.275 59.322 89.190 73.333 38.922 68.182 32.877 31.010 33.108 |

67.143 31.429 50.000 23.571 23.571 46.429 10.714 51.429 63.571 35.000 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.001 0.011 |

16.445 9.679 9.076 8.488 7.065 4.759 4.264 3.331 3.272 2.540 |

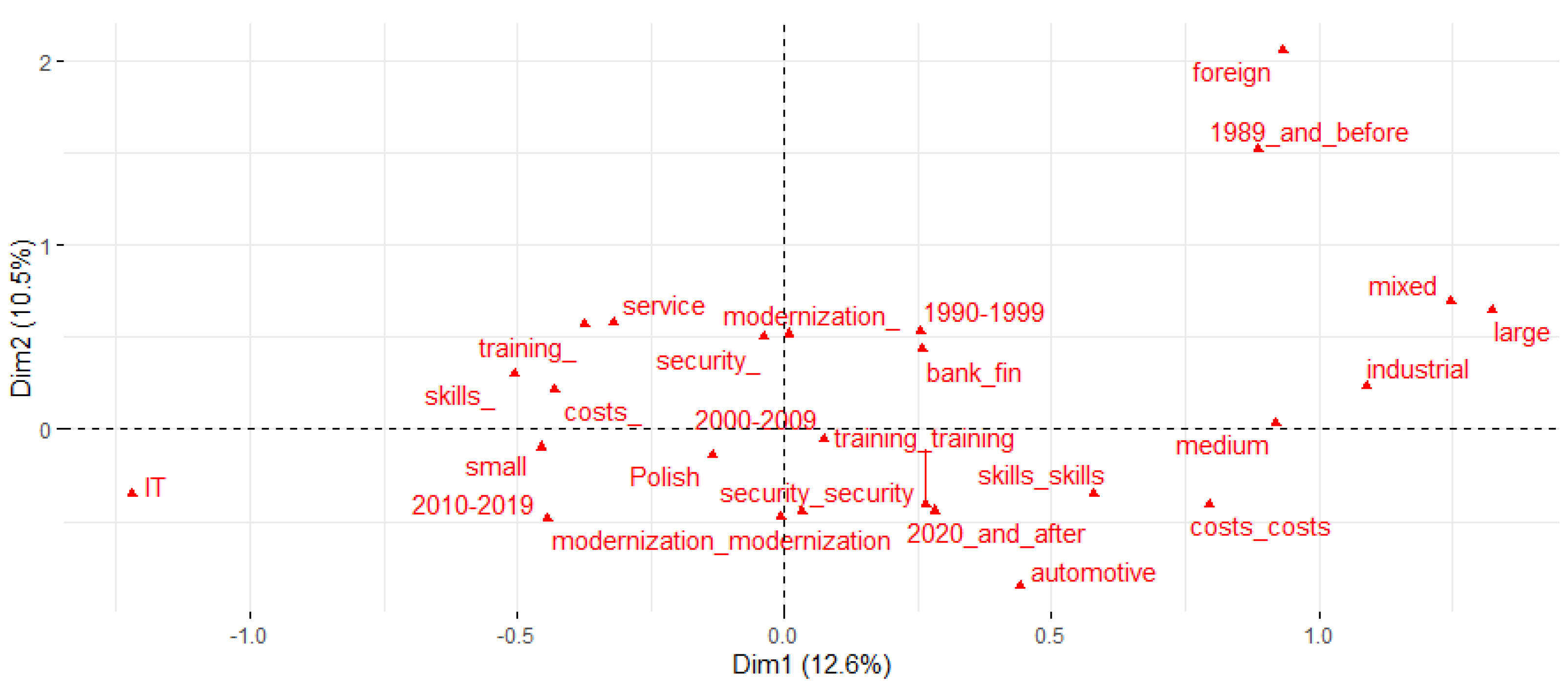

| Variables | p-value | df |

|---|---|---|

| sector | <0.001 | 12 |

| size | <0.001 | 6 |

| capital | <0.001 | 6 |

| modernization | <0.001 | 3 |

| skills | <0.001 | 3 |

| costs | <0.001 | 3 |

| year | <0.001 | 12 |

| security | <0.001 | 3 |

| training | <0.001 | 3 |

| Cluster | Cla/Mod | Mod/Cla | p-value | v-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cluster 1 sector=IT skills=skills_ costs=costs_ modernization=modernization_modernization size=small year=2010-2019 capital=Polish security=security_security training=training_ |

81.148 40.067 33.518 37.113 30.749 36.000 24.346 29.492 27.707 |

81.818 98.347 100.000 89.256 98.347 59.504 100.000 71.901 52.893 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.005 |

16.955 12.488 10.802 9.677 8.984 5.966 5.197 4.742 2.834 |

|

Cluster 2 modernization=modernization_ sector=service security=security_ size=small capital=Polish year=1990-1999 training=training_ sector=bank_fin costs=costs_ |

67.170 88.983 59.387 49.612 42.455 59.000 47.186 51.456 42.659 |

82.028 48.387 71.429 88.479 97.235 27.189 50.230 24.424 70.968 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.005 0.017 |

13.328 12.729 9.337 8.056 5.143 4.443 3.307 2.823 2.390 |

|

Cluster 3 costs=costs_costs skills=skills_skills training=training_training modernization=modernization_modernization sector=automotive size=medium security=security_security sector=industrial capital=Polish |

57.949 47.876 39.385 38.488 54.054 51.395 37.288 52.941 26.962 |

80.142 87.943 90.780 79.433 42.553 43.262 78.014 38.298 95.035 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.008 |

12.878 11.802 9.618 7.626 7.331 7.023 7.013 6.675 2.635 |

|

Cluster 4 year=1989_and_before size=large capital=foreign capital=mixed sector=industrial size=medium sector=bank_fin training=training_ skills=skills_ costs=costs_ modernization=modernization_ |

73.333 60.784 90.909 70.270 38.235 28.814 28.155 19.481 17.172 16.066 16.981 |

42.857 40.260 25.974 33.766 50.649 44.156 37.662 58.442 66.234 75.325 58.442 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.001 0.015 0.038 0.043 |

9.673 8.352 8.283 8.212 7.052 4.904 4.291 3.194 2.430 2.080 2.026 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).