Introduction

Cluster analysis is a fundamental tool in modern data science, providing critical insights during the preprocessing stage of large-scale data analysis. This technique is particularly valuable when dealing with high-dimensional datasets, which can consist of tens, hundreds, or even thousands of attributes. By organizing data samples into clusters based on their similarities, clustering allows researchers to uncover hidden patterns and relationships in unlabeled data. The core principle of clustering is to group samples with similar attributes into the same cluster while ensuring that samples in different clusters exhibit distinct characteristics [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Over the years, clustering has found applications across a diverse range of fields, including bioinformatics, pattern recognition, machine learning, data mining, and image processing [

3,

5,

6,

7].

Clustering plays a pivotal role in fields like bioinformatics, where gene expression data is often analyzed using clustering methods. By partitioning genes into clusters, researchers can infer relationships between genes, predict unknown functions, and better understand biological processes. For example, genes with similar functional roles or those participating in the same genetic pathways are typically grouped within the same cluster. This not only aids in exploring the genetic landscape but also facilitates advancements in precision medicine and disease diagnostics [

8].

Beyond bioinformatics, clustering serves as a cornerstone for analyzing unlabeled data in diverse contexts. Its importance can be summarized in five key areas [

9,

12]:

Facilitating Data Labeling: In many real-world scenarios, labeling datasets manually is prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. Clustering enables researchers to group similar data points, reducing the effort required for manual labeling.

Reverse Analysis: In data mining, clustering allows researchers to identify patterns and relationships in large, unlabeled datasets. Once clusters are identified, human observers can interpret and label the results for further analysis.

Adaptability to Change: In dynamic environments, such as seasonal food classification or adaptive recommendation systems, clustering can track evolving data attributes, ensuring that models remain relevant and accurate over time.

Feature Extraction: Clustering helps identify key attributes or features in datasets, enabling efficient data representation and improved performance in downstream machine learning tasks.

Structural Insight: By revealing the inherent structure and relationships within data, clustering provides valuable insights that inform decision-making and exploratory analysis.

With the explosion of big data across various domains, understanding and analyzing massive, high-dimensional datasets has become increasingly important. As a result, clustering has emerged as a crucial technique for making sense of complex data. However, the effectiveness of clustering largely depends on the choice of algorithm, which poses several challenges. Most existing clustering algorithms are broadly classified into hierarchical clustering and partitional clustering methods, each with its strengths and limitations [

10].

Hierarchical clustering organizes data into a tree-like structure, or dendrogram, which represents the nested relationships among data points. Clusters are formed by cutting the dendrogram at a specific level. This approach can be further divided into two strategies: divisive and agglomerative clustering [

11].

Divisive Clustering: Begins with all data points in a single cluster and iteratively splits them into smaller clusters until each point forms its own cluster.

Agglomerative Clustering: Starts with each data point as its own cluster and successively merges the closest clusters until all points are grouped into a single cluster.

While hierarchical clustering provides valuable insights into the data structure, it suffers from high computational complexity, making it unsuitable for large-scale datasets [

11].

Partitional clustering methods, such as k-means, k-medoids, Forgy, and Isodata, divide the dataset into a predetermined number of clusters based on distance metrics or optimization criteria [

13,

14]. Among these, k-means is widely used due to its simplicity, low computational cost, and ability to handle large datasets. However, k-means has several known limitations:

Sensitivity to Initialization: Poor initialization of cluster centroids can lead to suboptimal results.

Sensitivity to Outliers: Noise or outliers in the dataset can significantly skew clustering outcomes.

Input Layout Dependency: The algorithm’s performance depends heavily on the spatial distribution of data.

Result Variability: Different initializations may produce inconsistent clustering results.

Given these limitations, traditional clustering methods often struggle to address the complexities of high-dimensional and dynamic datasets.

Emergence of Ensemble Clustering

To overcome the inherent weaknesses of individual clustering algorithms, ensemble clustering has emerged as a robust alternative in recent years. Ensemble clustering combines the outputs of multiple clustering algorithms to generate more accurate and stable clustering results [

25,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. By leveraging the diversity of individual clustering solutions, ensemble methods reduce the biases and dependencies associated with single algorithms. Ensemble clustering typically involves two main stages:

Generation of Input Clusters: Produces a diverse set of clustering solutions using different algorithms or configurations [

30,

37].

Consensus Combination: Aggregates the input clusters to form a unified clustering result, minimizing inconsistencies and maximizing accuracy [

30,

37,

41,

42,

43,

44].

Despite its advantages, ensemble clustering faces challenges in effectively combining diverse input clusters, particularly when some inputs are highly inaccurate or contradictory. Addressing this limitation requires innovative methods to mitigate the dependency on input clusters while incorporating additional data-driven insights.

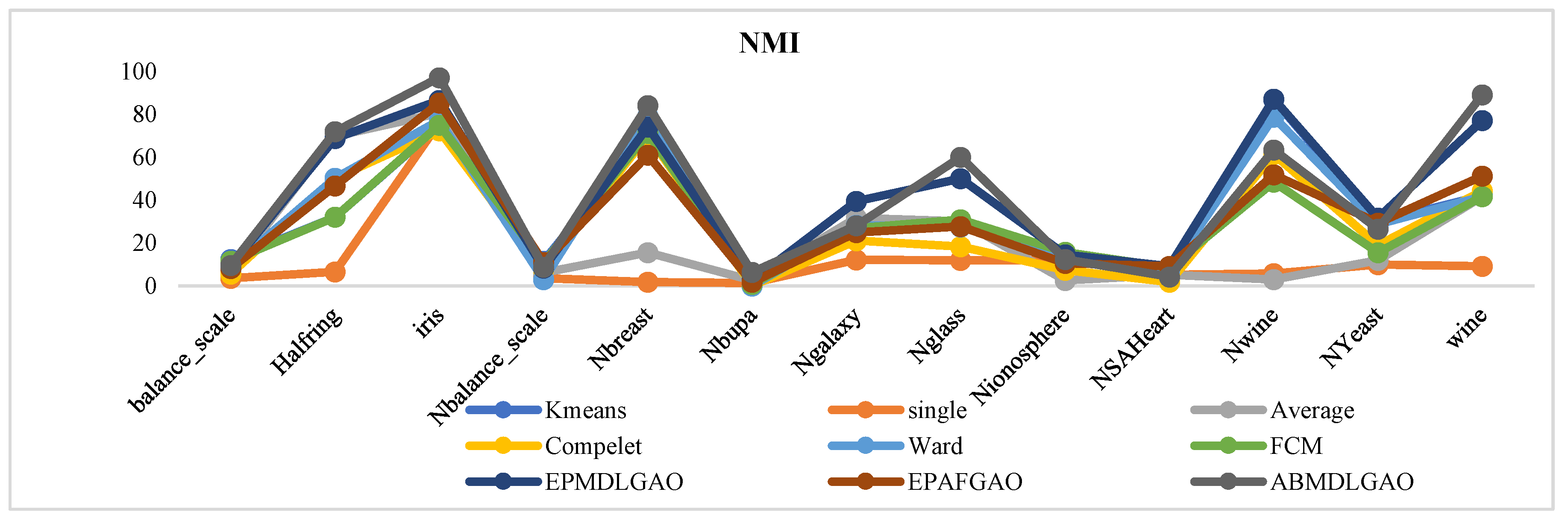

This study introduces a novel clustering approach that integrates the Minimum Description Length (MDL) principle with a genetic optimization algorithm to overcome the biases and limitations of existing methods. The proposed method begins with an initial solution generated through ensemble clustering. Using evaluation functions based on MDL and genetic optimization, the solution is iteratively refined to achieve more accurate and stable clustering results. Unlike traditional ensemble methods that rely solely on external input clusters, the proposed approach leverages both external information and intrinsic data properties, reducing dependency on initial inputs and enhancing robustness.

The proposed methodology has been evaluated on multiple standard datasets using comprehensive validation metrics, demonstrating its ability to produce high-quality clusters suitable for a wide range of applications.

The Proposed Method

In this study, we introduce a novel clustering method called Genetic MDL, which integrates the Minimum Description Length (MDL) principle with a genetic optimization algorithm to address the challenges of traditional clustering methods. The Genetic MDL framework aims to overcome the limitations of existing approaches by combining the strengths of MDL, which balances model complexity and data fidelity, with the adaptability and efficiency of genetic algorithms for optimization.

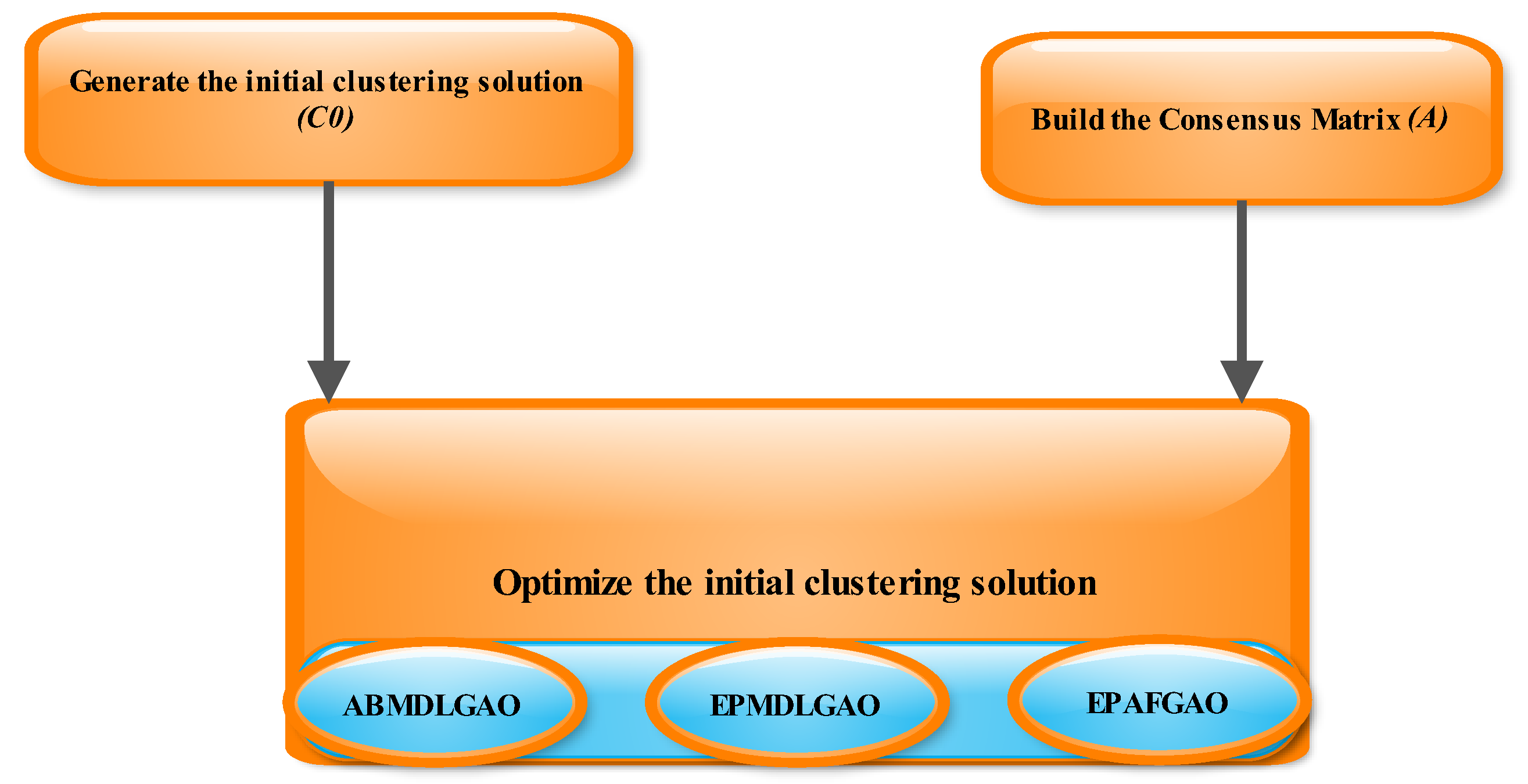

The Genetic MDL approach operates through three key optimization stages:

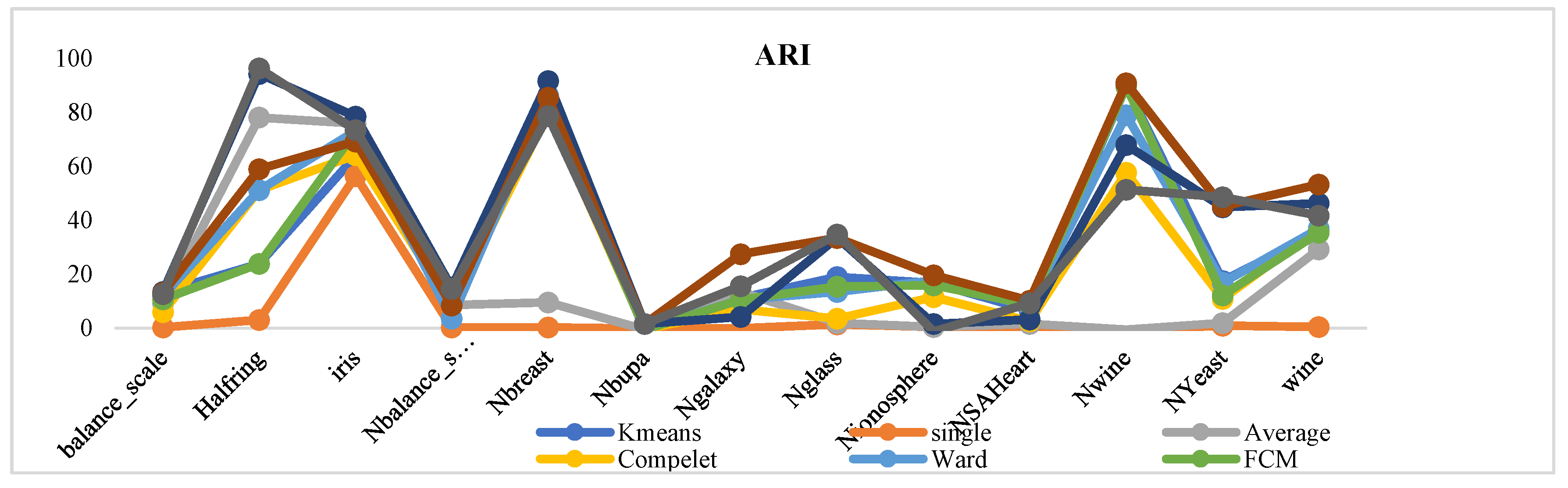

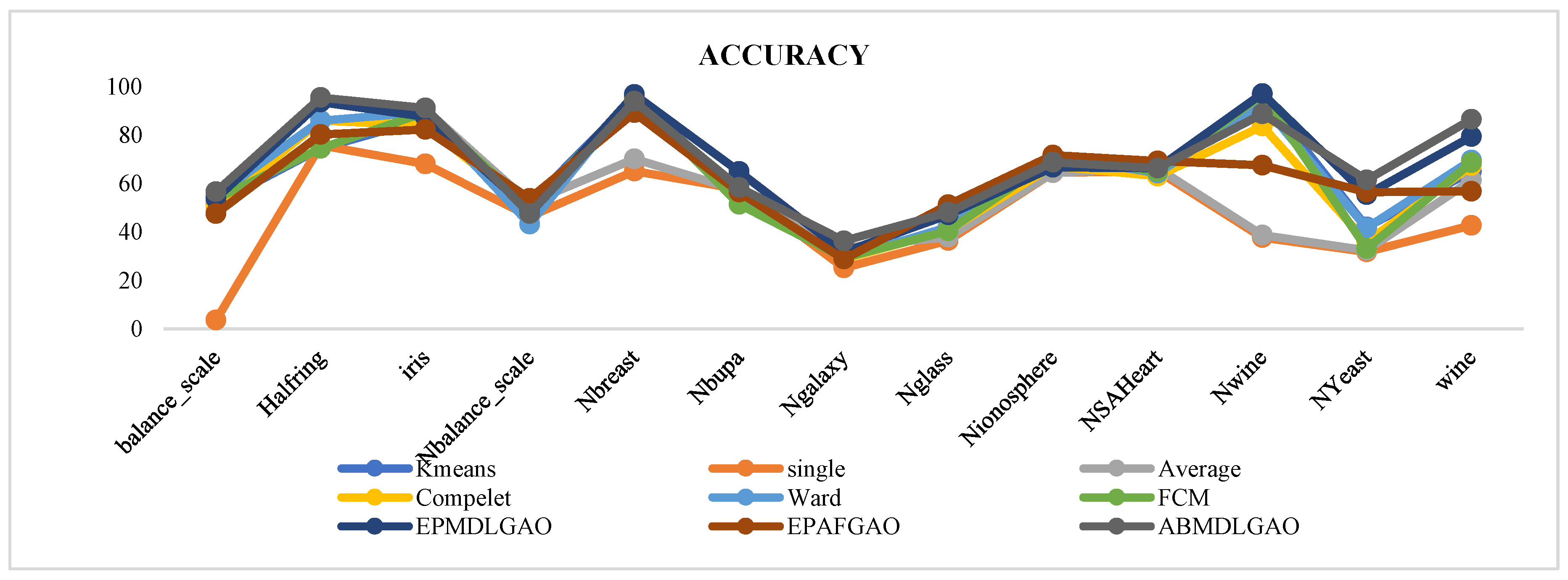

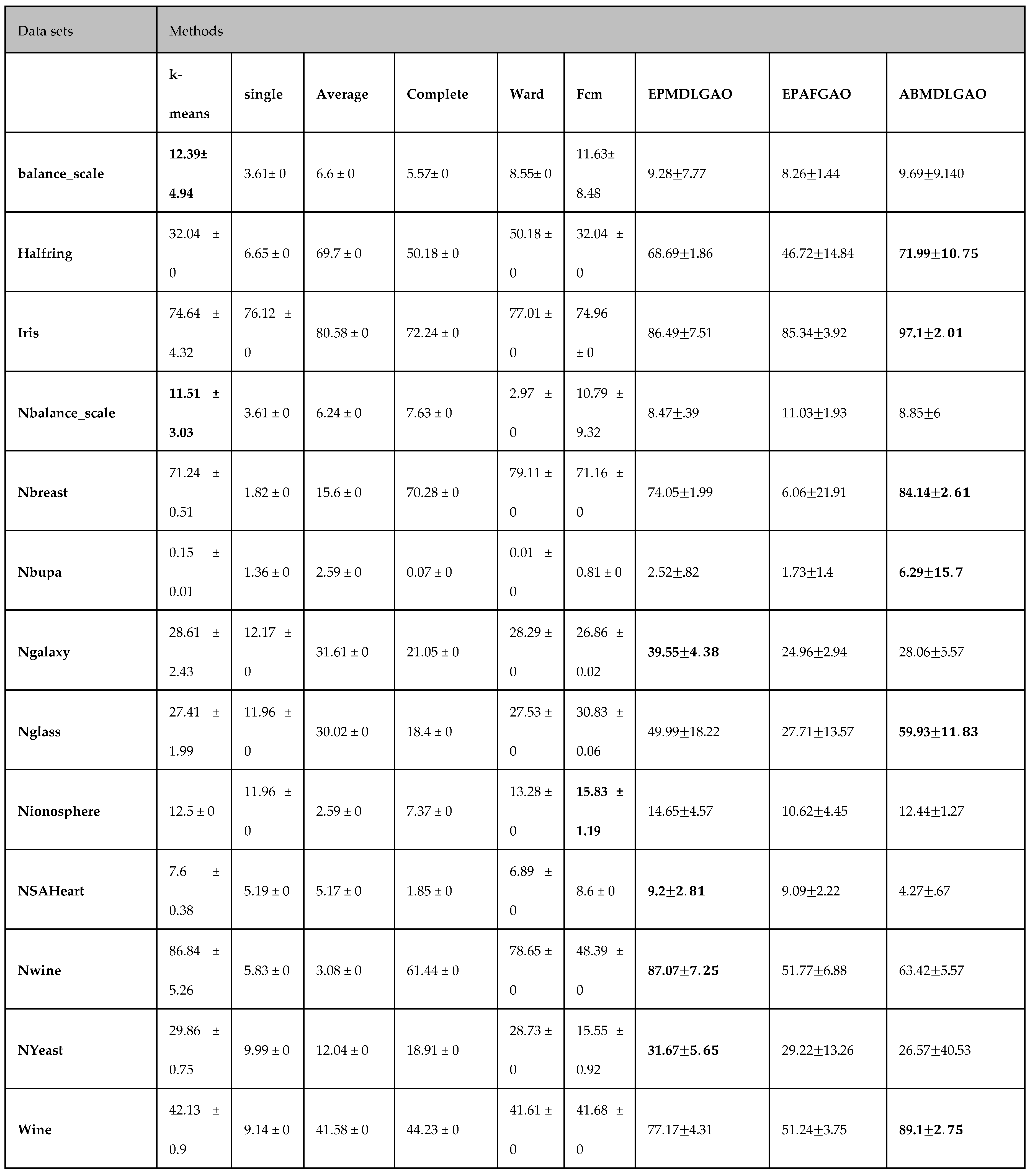

EPMDLGAO: This stage employs the MDL principle to evaluate and optimize partitioning solutions. It focuses on ensuring that the clustering result represents the data with minimal encoding cost, effectively balancing simplicity and accuracy.

ABMDLGAO: This stage applies MDL-based adjustments to the clustering model, further refining the cluster assignments to reduce redundancy and improve consistency across the dataset.

EPAFGAO: This stage incorporates an enhanced genetic algorithm to optimize cluster configurations, ensuring robust convergence to high-quality solutions.

The proposed framework leverages these three stages in sequence to iteratively refine the clustering process, ensuring that the final result is stable, accurate, and free from biases introduced by initial conditions or input clusters.

An outline of the Genetic MDL framework is provided in

Figure 1, which illustrates the interplay between the MDL principle and the genetic optimization algorithm in each stage.

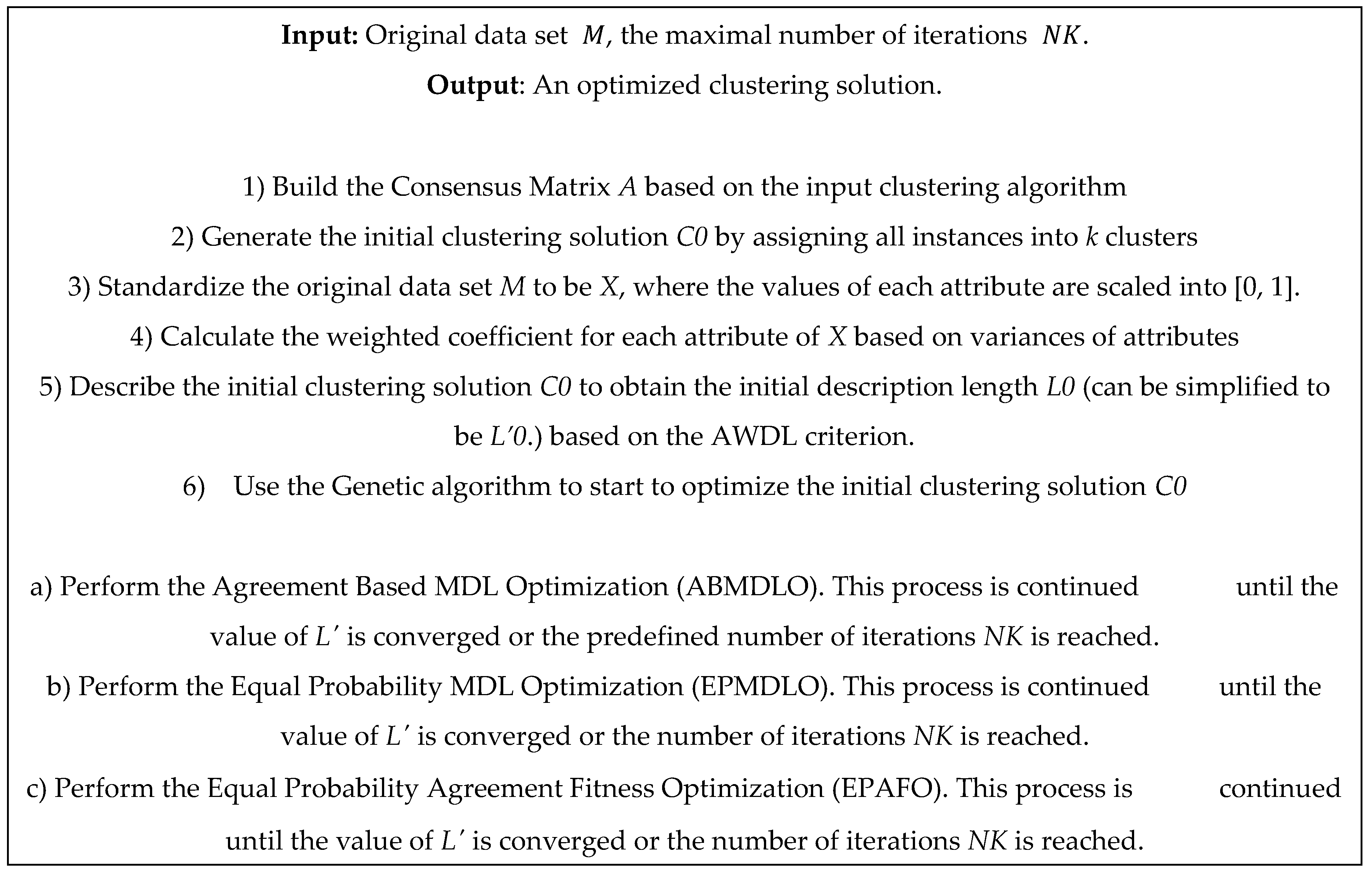

The quasi-code of the proposed method is shown in

Figure 2.

The Genetic MDL Framework

The Genetic MDL framework optimizes clustering by combining the Minimum Description Length (MDL) principle with genetic algorithms. It involves six key steps:

Formation of the Agreement Matrix (A): Constructs a matrix capturing consensus between clustering results from ensemble methods, forming the foundation for an initial solution.

Production of the Original Solution (C₀): Generates an initial clustering configuration by combining input clusters, ensuring diversity and robustness.

Normalization of Datasets: Scales data attributes to a uniform range, eliminating the influence of differing scales and ensuring consistent evaluation.

Calculation of Attribute Weight Coefficients: Assigns weights to attributes based on variance, prioritizing more informative attributes and reducing noise.

AWDL Description of the Original Solution: Evaluates the clustering solution using Attribute Weighted Description Length (AWDL) to balance model simplicity and data representation.

Genetic Algorithm Multiple Optimization (GAMO): Refines the clustering solution using genetic algorithm operations (selection, crossover, mutation) to achieve globally optimized, stable clusters.

Formation of Agreement Matrix (A)

The Agreement matrix is made on the basis of the results of input clustering which appears in the form of a one-dimensional vector and each of them forms a matrix row. These individual clusters are selected by qualified people. For any data set, the length of output vector of each individual clustering is equal to the total number of items in the data set that shows the number of each sample’s cluster. The Agreement Matrix is a square symmetric matrix with zero elements on the main diagonal. Each element of the Agreement matrix shows how many input clustering agreements agree with inserting two samples in a single cluster. Here the Agreement matrix is shown with variable A. A is the square symmetric matrix n × n, where n is the number of samples in the data set.

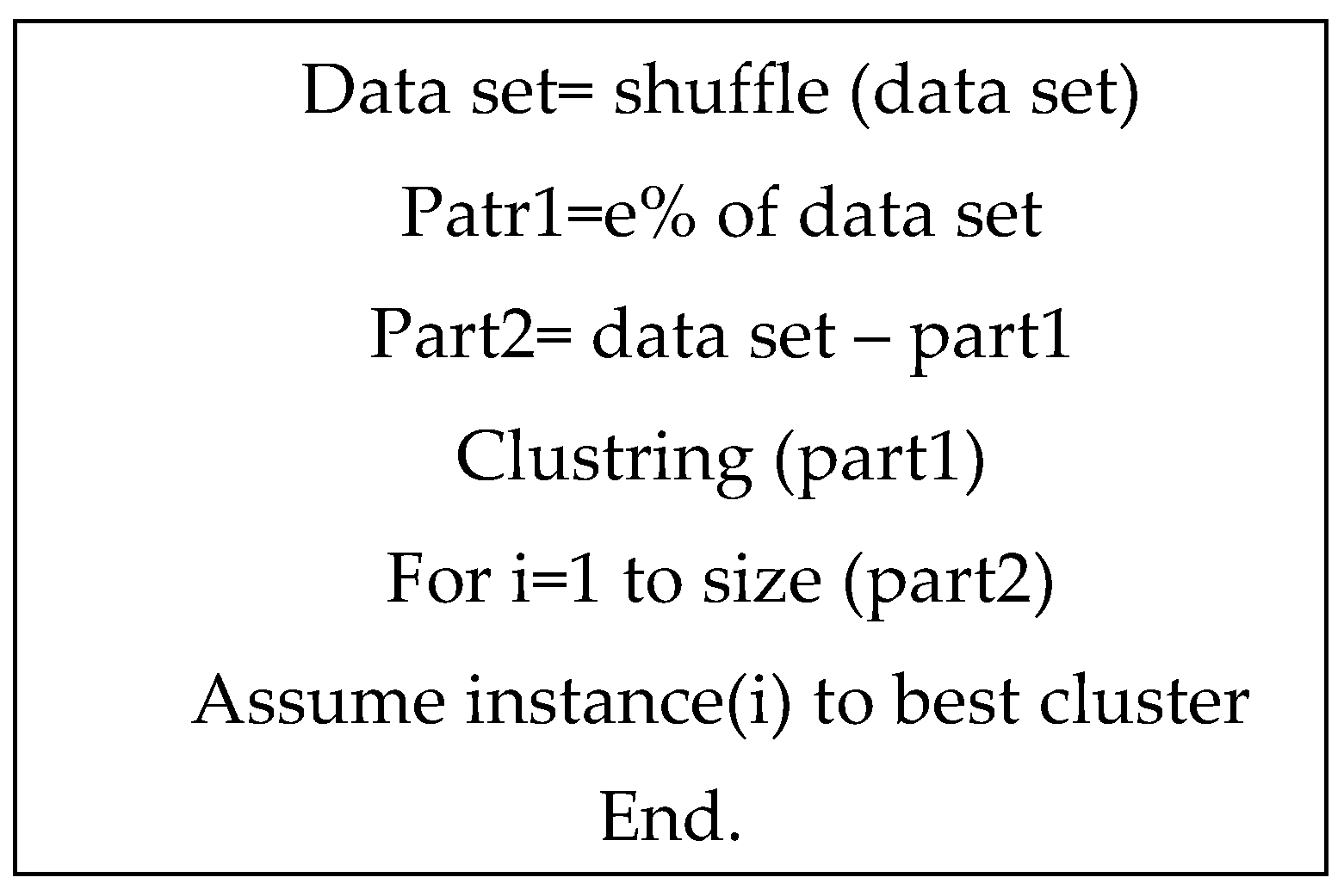

Figure 3 shows the Agreement matrix formation algorithm.

The formation of the Agreement Matrix (A) can be explained through an example. Consider three individual clustering algorithms: G1G_1G1, G2G_2G2, and G3G_3G3. Each algorithm clusters the dataset XXX, consisting of 10 samples, into three clusters. The clustering results are represented in vector form, where each element indicates the cluster assignment of a specific sample.

For instance, the clustering results are as follows:

Output G1 = {1 , 2, 1 , 1, 1, 3 , 3, 2 , 3, 1 }

Output G2 = {3 , 2, 3 , and 1, 2, 1 , 1, 3 , 2, 3 }

Output G3 = {2 , 1, 1, 3, 3 , 2, 1, 1, 2, 2 }

Results of G1, G2 and G3 clusters are displayed in the form of matrix Z. Then matrix Z is written in the form of matrix H.

The consensus matrix

A is obtained by equation 1.

In the above equation, H ‘ is the transpose of matrix H. In the above example, matrix A is equal to:

Production of the Original Solution (C0)

There are various techniques to produce the original solution, each offering distinct advantages depending on the characteristics of the dataset. One common approach involves running the K-means clustering algorithm multiple times (e.g., five iterations) and combining its results with hierarchical clustering methods such as Linkage Average, Linkage Complete, Linkage Ward, and Linkage Single, each executed once. The total number of iterations is set to an odd number to facilitate consensus in the final solution. After aligning the cluster labels from these methods, the results are aggregated through an ensemble process to determine the initial clustering solution.

Another method involves random sampling from the dataset. For instance, a subset of the samples (e.g., 80%) is randomly selected, and the K-means algorithm is applied to this subset to create initial clusters. The remaining samples are then assigned to these clusters based on their similarity to cluster centroids, often measured using a distance metric such as Euclidean distance. This method is particularly efficient for large datasets, as it reduces computational complexity while maintaining accuracy. This approach has been employed in the present study to generate the original solution. The algorithm for generating the initial solution is illustrated in

Figure 4.

Other techniques include density-based clustering, where methods like DBSCAN or OPTICS are used to identify dense regions in the data, which serve as initial clusters. Sparse points are treated as noise or assigned to the nearest cluster based on proximity. Additionally, model-based clustering, such as Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) or Expectation-Maximization (EM), can fit a probabilistic model to the data, providing cluster assignments as the initial solution. While effective for datasets with well-defined distributions, these methods may be computationally intensive for large datasets.

In this study, the random sampling with K-means clustering technique was selected due to its simplicity, efficiency, and ability to handle large datasets effectively, ensuring a robust starting point for subsequent optimization processes.

The following is an example to clarify this procedure.

Suppose that the data set A with 10 samples and the first part is equal to A '. After running the K-means algorithm on the data set A ', the clusters C1 and C2 are derived.

A = [1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8]

A '= [1; 2; 3; 5; 6; 7]

C1 = {1; 2; 3}

C2 = {5; 6; 7}

The remaining samples (e.g., samples 4 and 8) are then assigned to clusters C1C_1C1 and C2C_2C2, respectively, based on their proximity to the centers of these clusters. Proximity is typically measured using a distance metric, such as the Euclidean distance, ensuring that each sample is allocated to the cluster with the closest centroid.

Another approach, referred to as the third method, is similar to the second method but replaces the K-means algorithm with hierarchical clustering algorithms such as Linkage Average, Linkage Complete, Linkage Ward, and Linkage Single. The process proceeds in the same way as the second method, where a subset of the dataset is clustered first, and the remaining samples are subsequently assigned to the generated clusters based on their similarity to cluster centers.

The fourth method combines the strengths of the second and third methods. It uses both the K-means algorithm and hierarchical clustering algorithms (Linkage methods) to cluster the selected subset of samples. This hybrid approach ensures that the clustering leverages the diverse perspectives of both partitional and hierarchical methods, offering a more robust initial solution. By integrating the outputs of these algorithms, the fourth method provides a more comprehensive representation of the data structure, particularly for datasets with complex distributions.

These methods collectively offer flexibility and adaptability for producing the original clustering solution, depending on the characteristics and requirements of the dataset. In this study, the second method, involving random sampling with the K-means algorithm, was chosen for its simplicity, efficiency, and scalability.

Normalization of Data Sets

Before applying AWDL, the data set M should be normalized and standardized to X. in normalization, the value of each attribute is set between 0 and 1. Each row of the data set M is an example and each column is an attribute. Equation 2 shows the normalization.

In the above equation we have:

: represents the jth sample in the normalized data set X.

: represents the jth attribute of the ith sample in the main data set M.

n: is the total number of samples.

max () and min() are the highest and the lowest values in the jth attribute of the data set M.

Calculation of the Weight Coefficient of the Attributes

Variance measurement is the degree of variation (difference) between the values of a variable. A higher variance represents more differences between the values of a variable. The higher the variance of a variable, the more weight it would have. Here we use the variance as the weight of each attribute.

To calculate the weight of each attribute, equations 3 to 5 are used.

Dj: represents the variance of jth attribute for the samples of data set X.

n: is the number of samples in data set X.

Xij: represents the value of jth attribute of the ith sample.

: reflects the average value of jth attribute on n samples.

wj: represents the weight the jth attribute.

a: is the total number of attributes.

Description of the Initial Solution Based on the Attribute Weighted Description Length Criterion

In this study, we employ the Attribute Weighted Description Length (AWDL) criterion, which builds upon the foundational principles of the Minimum Description Length (MDL) framework. MDL is a modern and widely applicable approach for comparative inference, offering a general solution to model selection problems. Its core principle states that:

Any pattern or regularity in the data can be used for compression.

In other words, if a dataset exhibits a certain structure or pattern, fewer bits or samples are required to describe the data than would be needed for a dataset with no discernible structure. The extent to which data can be compressed is directly proportional to the amount of order or regularity within the dataset. The key strength of the MDL approach is its versatility, as it can effectively describe various types of data.

Grunewald et al. (2004) demonstrated that MDL is a comprehensive approach for inference and model selection, outperforming other well-known methods, such as Bayesian statistical approaches, in terms of effectiveness and general applicability [

40]. Today, MDL has been extended and applied in numerous research domains, including data clustering.

MDL in Clustering

The main concept behind using MDL in clustering is that the best clustering solution is the one that minimizes the description length of the dataset, rather than clustering solely based on similarity measures between samples. This approach ensures that clusters are formed in a way that optimally compresses the data, capturing its inherent structure.

To illustrate this concept, consider a dataset with NNN samples that need to be clustered into KKK clusters. The process involves two stages:

Formation of Initial Clusters: The KKK clusters are initialized, and the cluster centers are calculated based on the dataset.

Calculation of Distances: For each sample, the distance to the center of its assigned cluster is computed.

The quality of clustering is determined by the description length of the dataset. A clustering solution that minimizes the description length provides the best representation of the dataset. This methodology shifts the focus from traditional similarity-based clustering to a more holistic and information-theoretic perspective.

Attribute Weighted Description Length Criterion

The Attribute Weighted Description Length criterion is an extension of MDL, designed to incorporate attribute weighting into the clustering evaluation. Unlike standard MDL, which treats all attributes equally, AWDL assigns weights to attributes based on their variance, ensuring that more informative attributes contribute proportionally to the clustering process.

To calculate AWDL, the criterion LLL is applied, which consists of three components. The mathematical formulation of LLL is provided in Equation (6) and integrates the attribute weights, cluster structure, and overall dataset representation. The three components are:

Cluster Formation Cost: Captures the cost of forming clusters, including initializing cluster centers.

Cluster Assignment Cost: Represents the cost of assigning each sample to its respective cluster, considering its distance from the cluster center.

Compression Cost: Accounts for the compression achieved by clustering, balancing between simplicity and accuracy.

The AWDL criterion ensures that the clustering process is driven not only by the structural relationships within the data but also by the contribution of individual attributes, leading to a more robust and nuanced clustering solution.

In equation 6, W = [w1, w2, wa] is a vector that includes the weight of all attributes and since the vector W is always constant, AWDL can be easily expressed on the basis of criteria L ' and according to equation 7.

Sm and Sd are described in the following.

Sm: represents the sum of the average value of all clusters of a partition and is defined based on Equation 8.

To describe Sm in equation 8 we have:

: is the number of attributes (features) of the data set, and k is the number of clusters.

: represents the average value of jth attribute of the pth cluster.

: is the weight jth attribute of the data set.

: is defined according to equation 9 and represents the weighted average deviation for all samples of each cluster in a partition. Here the standard deviation was used to measure the difference between the average and value of each sample in the cluster.

In the above equation we have:

a: is the number of attributes ( features ) of the data set, k is the number of clusters and T is the number of samples in each cluster.

: represents the average value of jth attribute of the pth cluster.

: is the value of jth attribute of the qth sample in pth cluster .

Genetic Algorithm Multiple Optimization Framework (GAMO)

GAMO framework consists of three separate optimization phases:

MDL optimizer based on Agreement Based MDL Genetic Algorithm Optimization (ABMDLGAO).

Equal Probability MDL Genetic Algorithm Optimization (EPMDLGAO).

Equal Probability Agreement Fitness Genetic Algorithm Optimization (EPAFGAO).

The performance each phase is investigated in the following.

The Optimization Function ABMDLGAO

Displacing the samples within clusters, this tries to find the best cluster to embed any sample so that the criterion gets minimized (the criterion was described above). The probabilities of sample selection for the displacement are not the same. To evaluate the probability of each sample’s displacement, equations 10 to 13 are used. This process will continue until the value of L ' will converge or the iteration end condition will be reached.

Displacing the samples within clusters is a critical step in optimizing the clustering solution. This step aims to find the optimal cluster for each sample such that the criterion—as described earlier—is minimized. By minimizing , the clustering process ensures that the overall description length of the dataset is reduced, leading to a more efficient and accurate representation of the data.

To achieve this, samples are iteratively evaluated for potential displacement to a different cluster. However, the probabilities for selecting samples for displacement are not uniform. Instead, they are determined based on their likelihood of improving the clustering solution, which is calculated using Equations (10) to (13). These equations incorporate factors such as the distance of a sample to the cluster centers and the contribution of its displacement to minimizing . This probability-based selection ensures that the optimization process focuses on the most impactful samples, reducing unnecessary computations and enhancing convergence speed.

The displacement process continues iteratively, with each iteration re-evaluating the clustering configuration. This iterative adjustment persists until one of two conditions is met:

Convergence of : The value of stabilizes, indicating that further sample displacements will not significantly reduce the description length.

End Condition Reached: A predefined iteration limit or computational threshold is achieved, ensuring that the process terminates within practical runtime constraints.

By iteratively optimizing the placement of samples, this approach ensures a refined clustering solution that effectively balances accuracy, simplicity, and computational efficiency.

In the above equations we have:

: the Consensus Matrix.

: integrated agreement rate

: agreed value of sample pairs that include sample i and are in the cluster q.

(): maximum agreed value of : the number of maximum agreed value in .

: the agreed value of all sample pairs that include sample : is the number of maximum values in .

(): is the maximum agreed value of .

: is the simple agreed value

: The number of input clusters

: the sample’s probability of not being selected to be displaced

: the sample’s probability of being selected to be displaced

The Optimization Function EPMDLGAO

Similar to the ABMDLGAO function, this function aims to optimize sample placement within clusters to minimize the L′L'L′ value. However, unlike ABMDLGAO, the probabilities for sample displacement are uniform.

The Optimizer Function EPAFGAO

The objective function EPAFGAO serves as an agreed evaluation function, designed to identify solutions that maximize the value of the agreement objective function. The agreement function is mathematically defined using Equations (14) to (17).

In the above equations we have:

: The Consensus Matrix

(Consensus Threshold): reward for the clusters whose agreement values are higher than B, and punishment for the clusters whose agreement values are less than B.

and are respectively the maximum and minimum values in matrix .

: weighted agreement matrix obtained by the reduction of value from the consensus matrix and its main diagonal is zero.

: the evaluation function of ith cluster of the total clusters of the initial solution.

: the evaluation function of the initial solution.

: the number of samples in the ith cluster. If a cluster has only one sample (i.e. ), the evaluation function of the cluster will be zero.

: the kth element of the ith cluster.