1. Introduction

New and revamped locomotives must undergo a process of certification and a safety-related point is the demonstration by testing of the compliance with a range of signalling systems in use in the country in which the locomotive will operate [

1,

2].

The tests must be exhaustive, covering normal and exceptional operating conditions (OCs): locomotive distortion changes with OCs (traction, cruising, coasting, braking) and operating point, OP (e.g. intensity of effort) [

3].

The track couples disturbance onto track circuits (TCs) and the return current distribution may vary due to many factors: connections and arrangement of the return circuit (number of conductors, transversal bonding, use of impedance bonds, etc.), rail and track longitudinal impedance, locomotive and traction power station (TPS) relative position, soil conditions and track-to-earth leakage that modify the line frequency response (LFR) [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. In other words the transfer function (TF) between the locomotive return current

Il,c through its axles and the track quantities (e.g. rail currents

Ir1,

Ir2 or rail-to-rail voltage

Vr12) is affected by such parameters. This coupling is called “cold path”, to distinguish it from the “hot path” of the TPS current flowing to the locomotive along the catenary (

Il,h). Also this TF is subject to variability caused by TPS impedance, locomotive-TPS distance, geometry of conductors, and track parameters [

4,

5].

Il,h can be measured more easily than

Il,c, so that, under worst-case assumptions for parameters, configurations and number of trains, it can be related to signalling disturbance. This is the approach commonly adopted by administrations to decide the limits to apply to rolling stock (RS).

Assessment of RS distortion against limits is subject to variability, not only for changing RS OCs and the multiple sources on-board, but also because of overlapping of relevant transients (such as pantograph bounces and inrush phenomena) that require special modelling [

10].

The work reviews in

Section 2 the main characteristics of signaling circuits and rolling stock, and their interaction, to better understand and discuss test results with procedures commented in

Section 3. Several cases of DC and AC rolling stock are in fact analyzed in

Section 4, analysing variability of measured results, including line impedance and position.

2. Rolling Stock Signalling Interaction

2.1. Rolling Stock

RS consists of a locomotive with coaches or multiple units (so called EMUs) and represents the source of disturbance, caused by traction and auxiliary converters, interfaced by the front-end converter, which for DC systems is a DC/DC buck converter (aka chopper) and for AC systems is a four-quadrant converter (4QC). The return current leaving the axles couples with the victim TC conductively, in differential mode [

11,

12], whereas the return current in principle flows out the axles symmetrically along the track (two running rails in electric parallel) in both directions. A certain deal of asymmetry exists in the rail-wheel contact resistances, in the coupling between rails of the same and adjacent tracks, and in distributed earthing terms, that transforms the common-mode return current into differential-mode rail current [

13]: common transformation values are not larger than 0.1 [

11] and this is a first important assumption when fixing safety margins and limits.

Distortion may occur on a broad frequency range depending on converter architecture and technology. In the last twenty years DC choppers were brought to operate at several hundreds Hz, possibly interleaved, reducing size and weight of inductors. The DC chopper lets distortion terms caused by traction and auxiliary inverters downstream to leak overlapping to the main chopper switching component. AC rolling stock instead is dominated by the 4QC switching scheme, usually located around 1-2 kHz by interleaving smaller modules.

Depending on modulation and loading in both cases lateral components are also present with variable height: whereas for AC vehicles they are at multiples (odd or even) of the fundamental [

14], for DC rolling stock there is no clear pattern and various inter-modulation patterns may arise [

2].

There is a great variety and variability of distortion patterns [

15] and transients (pantograph bounce, wheel slip, overvoltages) [

10,

16,

17], for which the set of tested OCs should be extensive, to plausibly comprehend all relevant scenarios. It is nevertheless important to understand also the variability in supposedly uniform (or identical) OCs. Both such points are discussed in

Section 4 based on real measurements.

2.2. Signalling Circuits

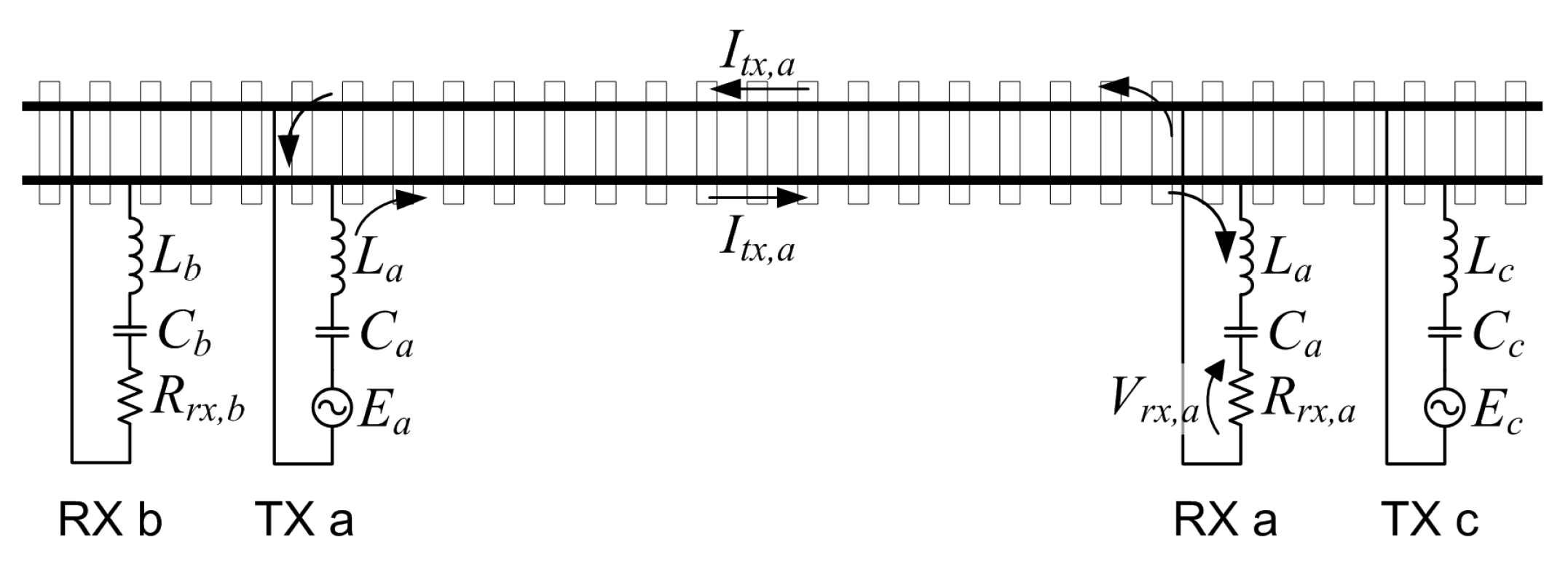

TCs use a modulated signal sent from a transmitter (TX) to one or two receivers (RX) over the track [

11,

12]. Track occupation is sensed by measuring the RX signal strength: the occupied status is detected when rails are shunted by the low-resistance axles of the entering RS and the RX signal drops below a threshold see

Figure 1. Operating frequency intervals range from some tens of Hz for power frequency TCs up to tens of kHz for audio-frequency (AF) TCs, with rare exceptions.

TX signals are nowadays always coded and modulated (using mostly Frequency Shift Keying, FSK, with a span of some hundreds Hz,

BRX), making them more robust against disturbance, in particular transients: limits are, however, specified mainly in amplitude vs. frequency assuming a steady disturbance, although the CLC/TS 50238-2 [

18] indicates also a more accurate assessment based on filter bank approach.

TCs are set up during commissioning to operate with a track voltage intensity that provides the desired flowing current Itx and signal-to-noise ratio at RX under a range of conditions:

2.3. Line Frequency Response

LFR has been extensively studied [

20,

21,

22], including sensitivity to geometrical and electrical parameters [

23]. For what regards this work, it is reminded that:

different line sections can show different frequency responses (shifted resonances of different amplitude);

anti-resonances are particularly important, as they amplify current components and they depend on train position, so they are variable during a test run [

24];

in particular, positioning RS in front of the TPS maximizes current emissions, as line length is minimized, but amplification due to anti-resonances is missed.

2.4. Emission Limit Masks

Limits may be specified for a single frequency (namely a narrow frequency band around the operating frequency of a given TC) or as a whole curve spanning over an extended frequency interval (e.g. covering all possible TC installations of an entire country [

25]).

Suitable limits are defined considering all factors discussed in the Introduction that cause TF variability; such limits may be deterministic (mostly) or statistic (so, allowing exceedance if occurring rarely). In the following limits are considered exact and measurement errors and uncertainty are evaluated forgetting about the underlying margins and assumptions.

3. Testing Methods

The selection of the railway line configuration and rolling stock OCs, first, are followed by the identification of the methods for the measurement, recording and post-processing of signals. It is reminded that at this point the TC is not part of the assessment process, being its behaviour synthesized in the limit mask with all assumptions on line configurations and transfer functions.

3.1. Railway Line and Rolling Stock Operating Conditions

A general attitude by administrations is using always the same line and implicitly comparing the behaviour of different rolling stock items through time. In reality a more solid technical justification would be preferable:

either the test line is very simple, so to reproduce a clear distribution of the return current (such as a single-track straight line with current flowing back in one direction only),

or it’s a long line reproducing many relevant cases of resonances and anti-resonances, of close proximity to the TPS, etc., with possible issues of mixed traffic.

In general intense acceleration and braking are applied, but this does not ensure that spectral components at all frequencies would be maximal, only the overall current intensity is maximum; selected OPs could then be added to this aim.

Regarding how measurement results are then processed and used, a common attitude imposed by administrations is using the maximum envelope of measured spectra, in an attempt of providing additional margin leading to an undisputable worst case. The components maxima of course do not occur all at the same time and may belong to different OCs and OPs; in addition the resulting envelope spectra have poorer resolution and do not resemble those visible on instruments during tests, compromising physical significance, as a matter of fact. Carefully controlling OCs and OPs ensures that repeatability of results is not compromised. The use of max-hold envelopes in fact cannot be used as a blanket to hide poor similarity between otherwise identical OCs and OPs.

Repeatability and similarity are in fact an index of good quality of measurements to process variously. Repeatability can be made correspond to data dispersion taking repeated measurements under assumed same OCs and OPs, that means on the short time for adjacent time records or across controlled alike test runs. Similarity instead is a more subjective judgment that is necessary when a purely numeric measure of difference (dispersion) is ineffective, due e.g. to slight parametric changes of the curves (as caused by different line conditions or driving style) [

24,

26].

3.2. Measurement and Analysis of Pantograph Current

The spectrum of disturbance should be evaluated with a frequency resolution δf≤BRX (smaller frequency bins can be rms summed to cover BRX, larger ones have lost irretrievably the necessary resolution).

When analyzing data with the Short Time Fourier Transform (STFT), a large δf of tens of Hz (or even a hundred) ensures a shorter time window T=1/δf, and thus better time resolution, able to follow rapidly changing OPs. Single FFT spectra for each T can then be conveniently composed during post-processing, using the mentioned max-hold or other statistics.

To include the effect of transient signals in a broader perspective, a better approach would be moving from a spectrum oriented time-frequency analysis to a filter-bank based method, able to weight the incoming components within the TC bandwidth and their evolution along the time axis in a way as close as possible to the real TC behaviour [

18,

25].

4. Test Cases

Three different test cases have been analysed differing in terms of RS and supply system (

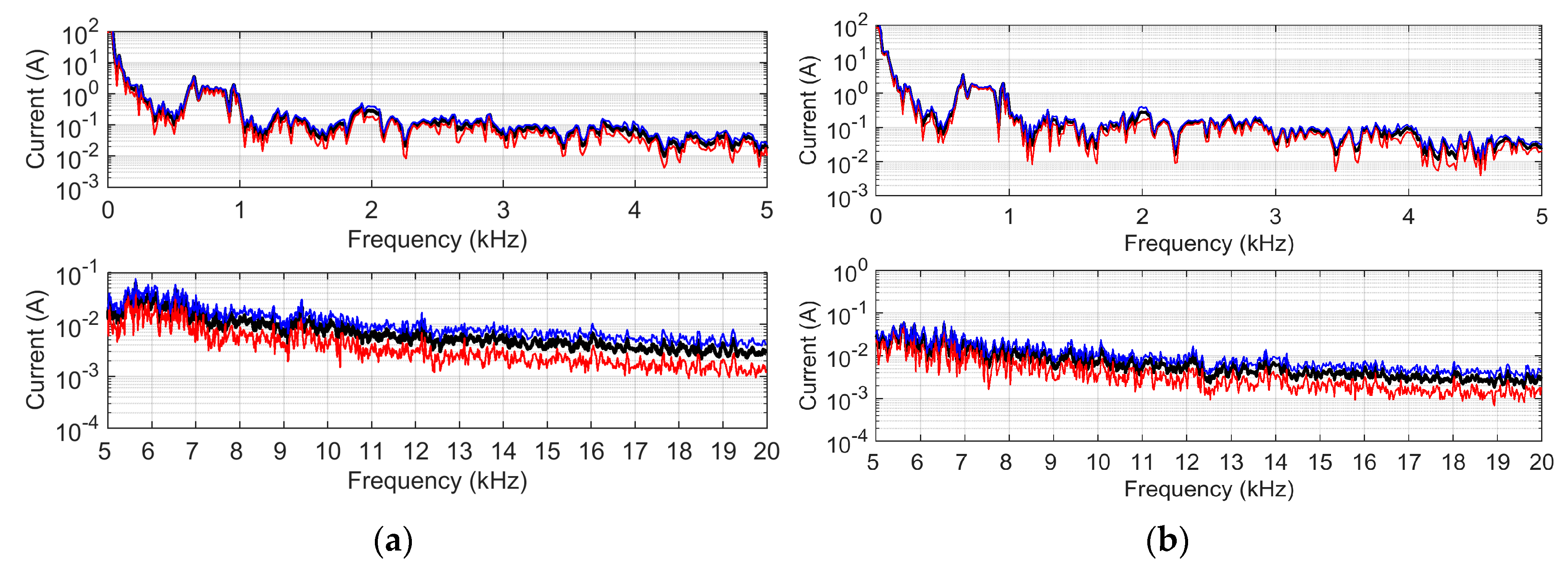

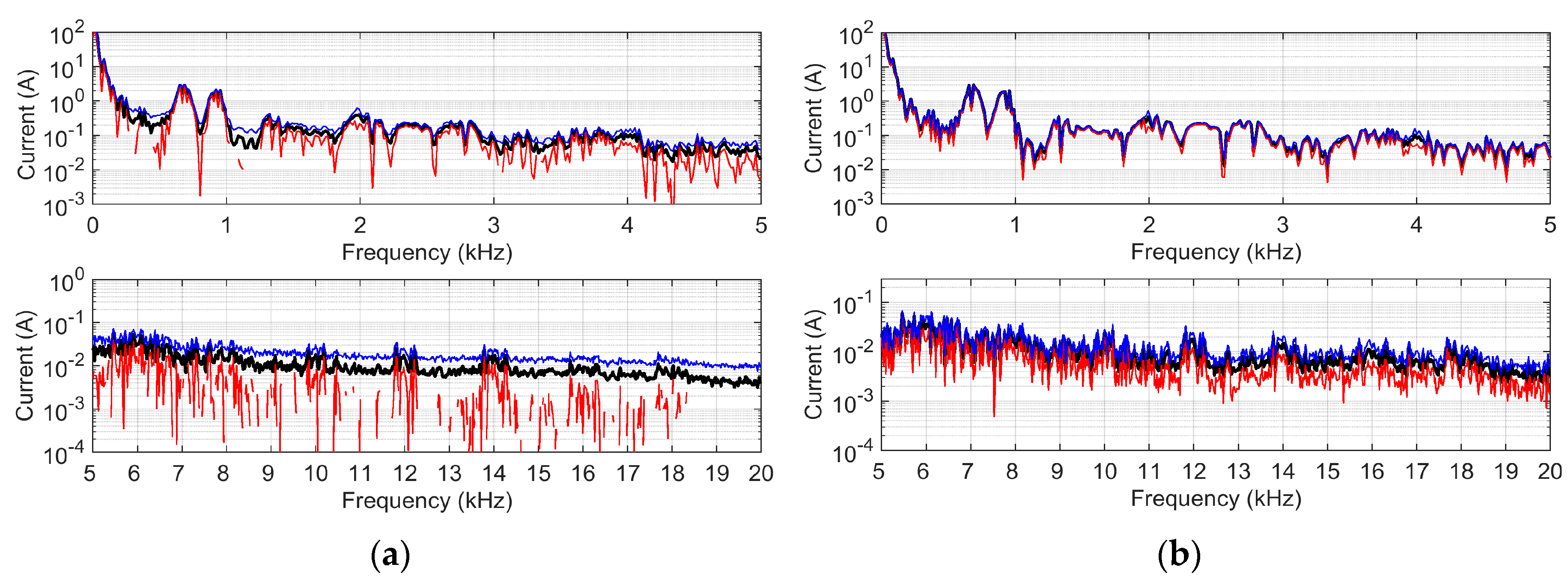

Table 1). Evaluation of repeatability is achieved by calculating the sample standard deviation σ and mean μ reported using a blue and red curve for ±1σ profiles around a thicker black curve for the mean.

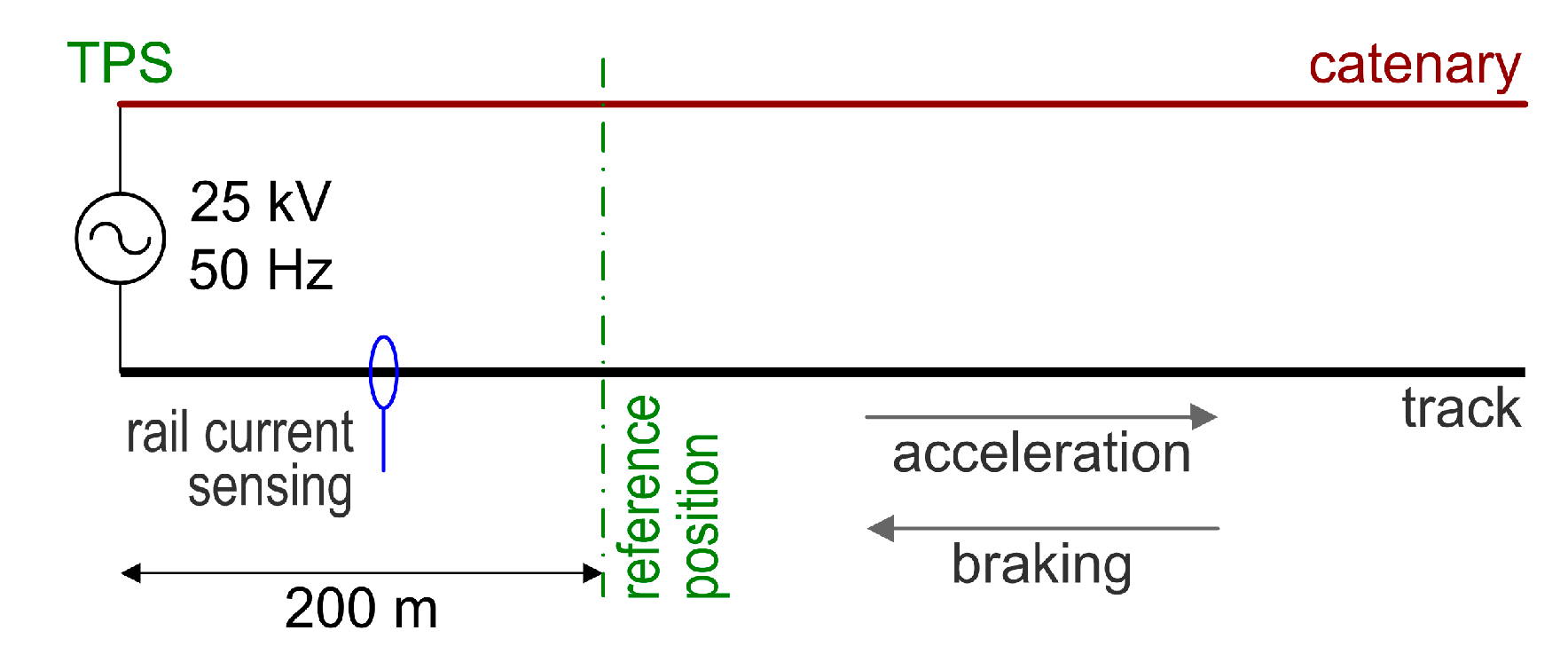

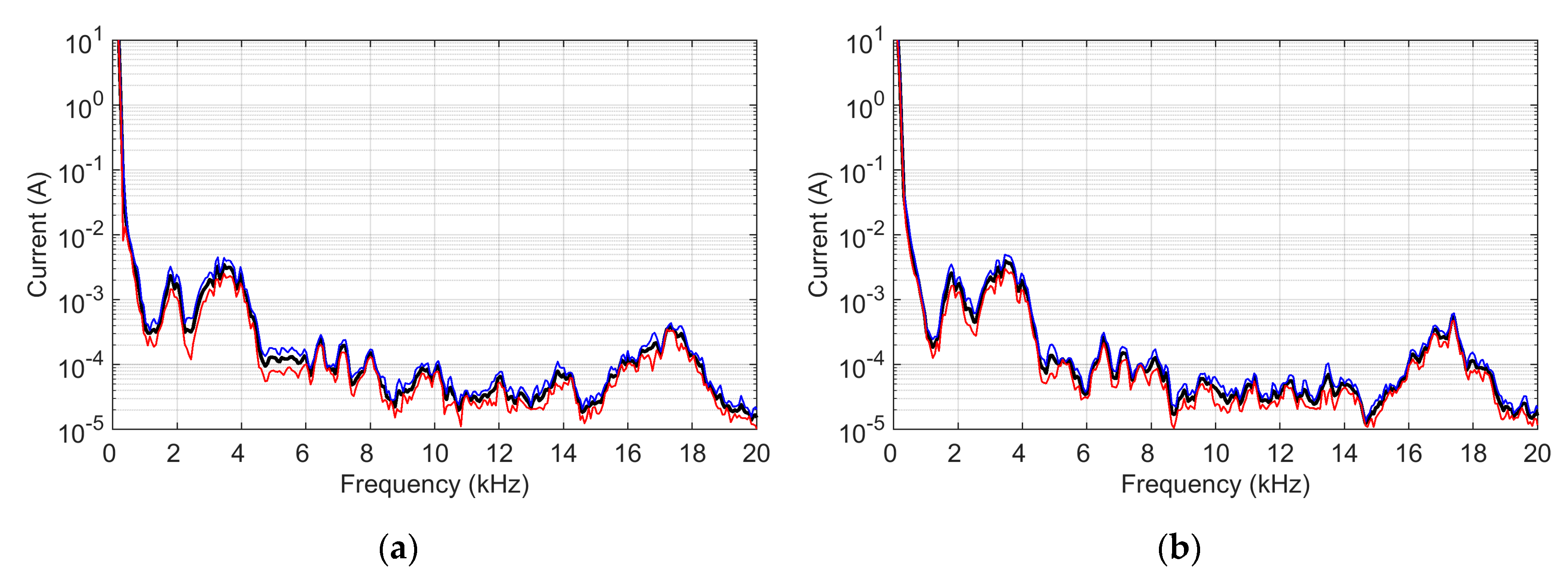

4.1. Single Track 25 kV 50 Hz

A light commuter train with 4 cars was tested under a 1x25 kV 50 Hz supply. The test track was supplied at one end by the Depot TPS and the train was departing from (ACC) or braking to (BRK) a specific reference point, leaving a distance of about 200 m from the TPS according to test set up shown in

Figure 2. The track was arranged removing cross bonding connections with the adjacent track, resulting in a single track configuration. Rail currents were measured in this short section knowing that track leakage was negligible thanks to the short length. The reason for measuring rail current rather than onboard pantograph current was the concomitant test of induction on wayside cables at the same location and a general difficulty of communication with personnel onboard.

The measurement setup was composed of two Rogowski coils for the two running rails connected to a HP 35670A FFT analyzer, providing data directly in one frequency domain spectrum that does not allow the analysis of variability in the short time over subsequent records.

Figure 3 shows the pantograph current measured in acceleration and braking conditions; variability was calculated collecting 3 test runs, in ACC and BRK, and the σ/μ ratio ranges between 1 % and 3 % for all components. It is noted that the frequency resolution limited by the available instrument 800 frequency bins helps smoothing the curves.

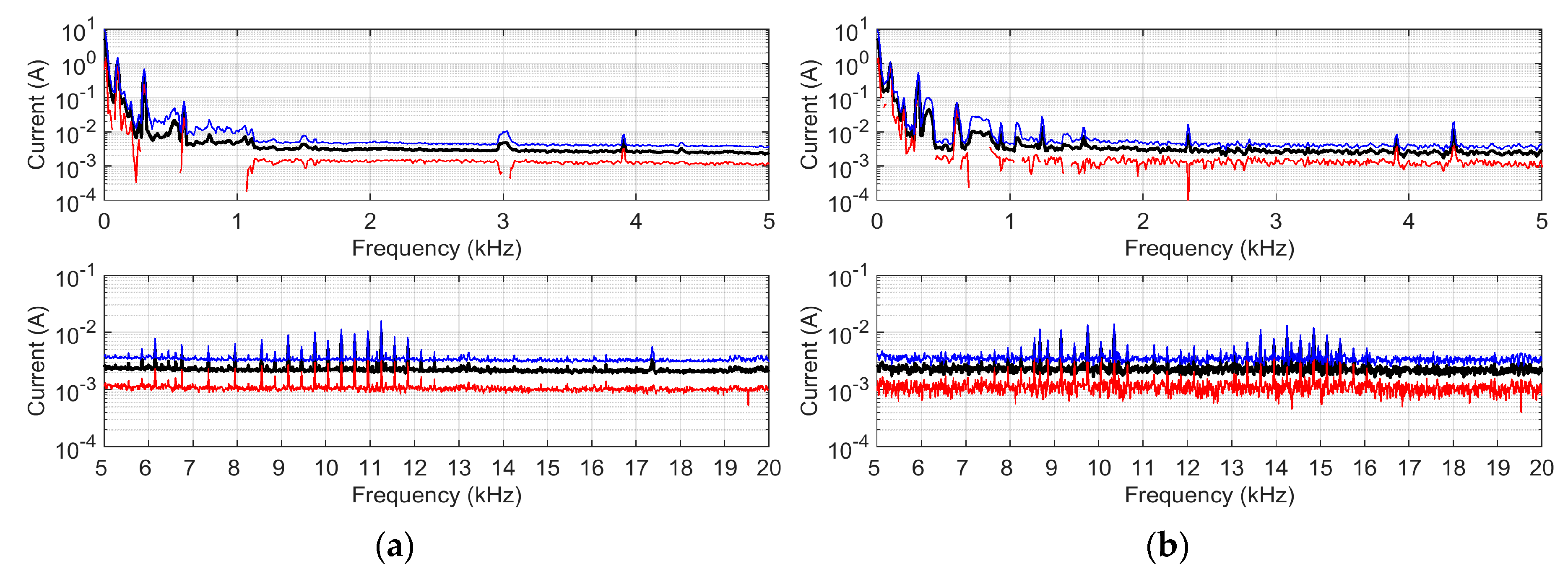

4.2. 3 kV DC Locomotive on Real Line

A 3 kV DC 3.5 MW locomotive was tested over about 100 km in Italy, allowing the recording of a wide range of testing conditions (traction, cruising and braking), but missing an accurate definition of infrastructure conditions met during locomotive runs. Measurements were carried out using a LEM Rogowski mod. R3030 located on the internal busbar near the main circuit breaker and a Picoscope mod. 4424 (12 bit), sampling at about 200 kHz.

Figure 4 shows the pantograph current measured in acceleration and braking conditions; DC traction current harmonics are more variable compared to AC, as no fundamental is available, except for the known TPS harmonics. The analysis is done then only for those components clearly correlated with RS emissions. Variability over 4 runs is 3-5 %, whereas values > 30 % may characterise uncorrelated components. A correlation analysis of

Ip and

Vp (not recorded), would have helped isolating RS emissions [

3,

27]. Pantograph voltage is, however, rarely measured, if not strictly necessary, due to safety issues of connecting to a high-voltage circuit. During recordings many out-of-scale were observed due to onboard filter oscillations [

16], making captured waveforms asymmetrical and causing spectrum leakage. Tapering windows may be used with moderate spectral leakage, but not when the low-frequency oscillation is much larger than the components subject to analysis, and such records must be discarded.

4.3. 15 kV AC Locomotive on Real Line

A 15 kV 16.7 Hz Swiss passenger train equipped with a Re460 locomotive was tested using a LEM Rogowski coil mod. R3030 (20 kHz bandwidth) and a 16-bit Dewetron data acquisition system sampling at 50 kHz [

28]. The big amount of usable data allowed in this case evaluating repeatability in various OCs and OPs at 4 different locations. The differences in terms of variability of measurement performed using same OCs in different locations along the line and using different OCs in the same location is shown both for acceleration (

Figure 5) and braking (

Figure 6) conditions.

The standard deviation is calculated for all frequency samples although it should be considered only for RS emission components. The FFT resolution is 16.7 Hz, focusing on the expected harmonics of the 4QC converter. Repeatability is some %, but data abundance allows these considerations:

Amplitude distribution is asymmetric, more compact at the highest levels of emission with a long tail towards very small values, so that dispersion does not transfer straightforwardly to an estimate of uncertainty;

Repeatability in ACC and BRK is in the order of 3 % for RS emission components with minimum influence of the infrastructure for most of them (so, for the same OP and same or different locations);

LFR resonances have a significant effect at high frequency, so that above 15 kHz repeatability worsens by an order of magnitude (about 30 %); this is also due to some movement between adjacent frequency bins due to slight fundamental instability.

5. Conclusions

The work has considered test methods for the assessment of rolling stock distortion with respect to interference with signalling circuits, and in particular track circuits. Two topics have been discussed: the railway line selection for tests and the operating conditions that should tested; the measurement setup and its accuracy, as well as suitable methods to assess compliance to interference limits, considering both spectrum- and filter-based methods.

Evaluation in DC system is strictly related to the correct identification of current emission of the vehicle. Considerations about characteristic switching frequency of the converter or correlation analysis with pantograph voltage might be useful for the purpose. The calculation of the variability of the standard deviation normalized for the average value of the specific components might be useful in order to identify coherent emissions.

Variability calculated for same OCs in acceleration and braking conditions is generally comparable.

Emission current variability distribution are generally asymmetric, being less widespread towards high emissions values that are those relevant for the analysis described.

In order to perform reliable evaluations against rolling stock emission limits care shall be taken to carefully select OCs and OPs, also considering that emission are influenced by line resonance conditions.

Low variability values are index of a good performance of emission measurements and of a good repeatability of measurement performed. An analysis in terms of data dispersion among various measurements allows to discard or deeply analyse measurements with outliers in order to improve accuracy of measurement emissions and evaluation against imposed limits.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- V. Havryliuk and T. Serdyuk, “Distribution of harmonics of return traction current on feeder zone and evaluation of its influence on the work of rail circuits,” in 18th Intern. Wroclaw Symp. and Exhib. on Electromagnetic Compatibility, Wroclaw, Poland, June 28−30, 2006, pp. 467-470.

- M. Steczek, A. Szelag, and D. Chatterjee, “Analysis of disturbing effect of 3 kV DC supplied traction vehicles equipped with two-level and three-level VSI on railway signalling track circuits”, Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci.: Tech. Sci., Vol. 65, no. 5, pp. 663−674, 2017.

- A. Mariscotti, “Non-Intrusive Load Monitoring Applied to AC Railways,” Energies, Vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 4141, 2022.

- J. Bongiorno and A. Mariscotti, “Variability of pantograph impedance curves in DC traction systems and comparison with experimental results,” Przegląd Elektrotechniczny, Vol. 90, no. 6, pp. 178−183, 2014.

- P. Ferrari, A. Mariscotti, and P. Pozzobon, “Reference curves of the pantograph impedance in DC railway systems,” in Proc. of IEEE Intern. Conf. on Circuits and Systems, Geneve, Switzerland, 28−31 May 2000.

- A. Dolara, M. Gualdoni, and S. Leva, “EMC disturbances on track circuits in the 2×25 kV high speed AC railways systems,” in IEEE PES Trondheim PowerTech 2011, Trondheim, Norway, Jun. 19−23, 2011.

- W. Huang, Z. He, H. Hu, and Q. Wang, “Study on Distribution Coefficient of Traction Return Current in High-Speed Railway,” Energy and Power Eng., Vol. 5, pp. 1253–1258, 2013.

- R.K. Nair., D.K. Saini, and M. Jayaraju, “Dynamism of Parasite Capacitance of AC Electric Traction Line Inside the Railway Tunnels”, IETE J. Res., Vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 1358–1365, 2022.

- A. Mariscotti, “Impact of Rail Impedance Intrinsic Variability on Railway System Operation, EMC and Safety,” Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng., Vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 17–26, 2021.

- J. Bongiorno “Induced touch voltage in wayside cables of AC railways caused by traction supply transients”, Electr. Eng., Vol. 105, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2023.

- A. Mariscotti, M. Ruscelli, and M. Vanti, “Modeling of Audiofrequency Track Circuits for validation, tuning and conducted interference prediction,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Sys., Vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 52−60, 2010.

- L. Zhao and M. Li, “Probability Distribution Modeling of the Interference of the Traction Current in Track Circuits,” J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol., Vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 125−131, 2012.

- S. Razghonov, V. Kuznetsov, O. Zvonarova, and D. Chernikov, “Track circuits adjusting calculation method under current influence traction interference and electromagnetic compatibility,” Mat. Sci. Eng., Vol. 985, 2020.

- A. Mariscotti, “Results on the Power Quality of French and Italian 2x25 kV 50 Hz railways”, I2MTC 2012, Graz, Austria, May 13-16, 2012.

- R.S. Salles, R.A. De Oliveira, S.K. Rönnberg, and A. Mariscotti, “Analytics of Waveform Distortion Variations in Railway Pantograph Measurements by Deep Learning,” IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas., Vol. 71, pp. 1–11, 2022.

- A. Mariscotti and D. Giordano, “Experimental characterization of pantograph arcs and transient conducted phenomena in DC railways,” Acta Imeko, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 10–17, 2020.

- P.M. Nicolae, M.S. Nicolae, I.D. Nicolae, and A. Netoiu, “Overvoltages Induced in the Supplying Line by an Electric Railway Vehicle,” in IEEE Intern. Joint EMC/SI/PI and EMC Europe Symp., Raleigh, NC, USA, July 26−Aug. 13, pp. 653−658, 2021.

- Railway applications — Compatibility between rolling stock and train detection systems — Part 2: Compatibility with track circuits, CENELEC Standard CLC/TS 50238-2, 2015.

- A. Mariscotti and P. Pozzobon, “Experimental results on low rail-to-rail conductance values,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Techn., Vol. 54, no. 3, pp. 1219−1222, 2005.

- A. Dolara, M. Gualdoni, and S. Leva, “Impact of High-Voltage Primary Supply Lines in the 2×25 kV – 50 Hz Railway System on the Equivalent Impedance at Pantograph Terminals,” IEEE Trans. Pow. Del., Vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 164−175, 2012.

- M. Ceraolo, “Modeling and Simulation of AC Railway Electric Supply Lines Including Ground Return,” IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif., Vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 202−210, 2017.

- T. Serdiuk and K. Serdiuk, “Mathematic modeling of distribution of traction current harmonics,” in Joint IEEE Intern. Symp. on Electromagnetic Compatibility Signal and Power Integrity, and EMC Europe, EMC/SI/PI/EMC Europe, pp. 659–662, July 2021.

- R. Garg, P. Mahajan, and P. Kumar, “Sensitivity Analysis of Characteristic Parameters of Railway Electric Traction System,” Int. J. Electron. Electr. Eng., Vol. 2, no. 1, 2014.

- J. Bongiorno and A. Mariscotti, “Experimental validation of the electric network model of the Italian 2x25 kV 50 Hz railway”, in 20th IMEKO TC4 Symposium on Measurements of Electrical Quantities, pp. 964–970, 2014.

- Railway applications — Interference limits of existing track circuits used on European railways, CENELEC Standard CLC/TR 50507, 2007.

- J. Bongiorno and A. Mariscotti, “Robust estimates for validation performance indexes of electric network models”, International Review of Electrical Engineering, Vol. 10, no 5, pp. 607−615, 2015.

- J. Bongiorno and A. Mariscotti, “Recent results on the power quality of Italian 2x25 kV 50 Hz railways”, 20th IMEKO TC4 Symposium on Measurements of Electrical Quantities, pp. 953–957, 2014.

- A. Mariscotti, “Data sets of measured pantograph voltage and current of European AC railways,” Data In Brief, Vol. 30, id 105477, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).