Submitted:

06 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

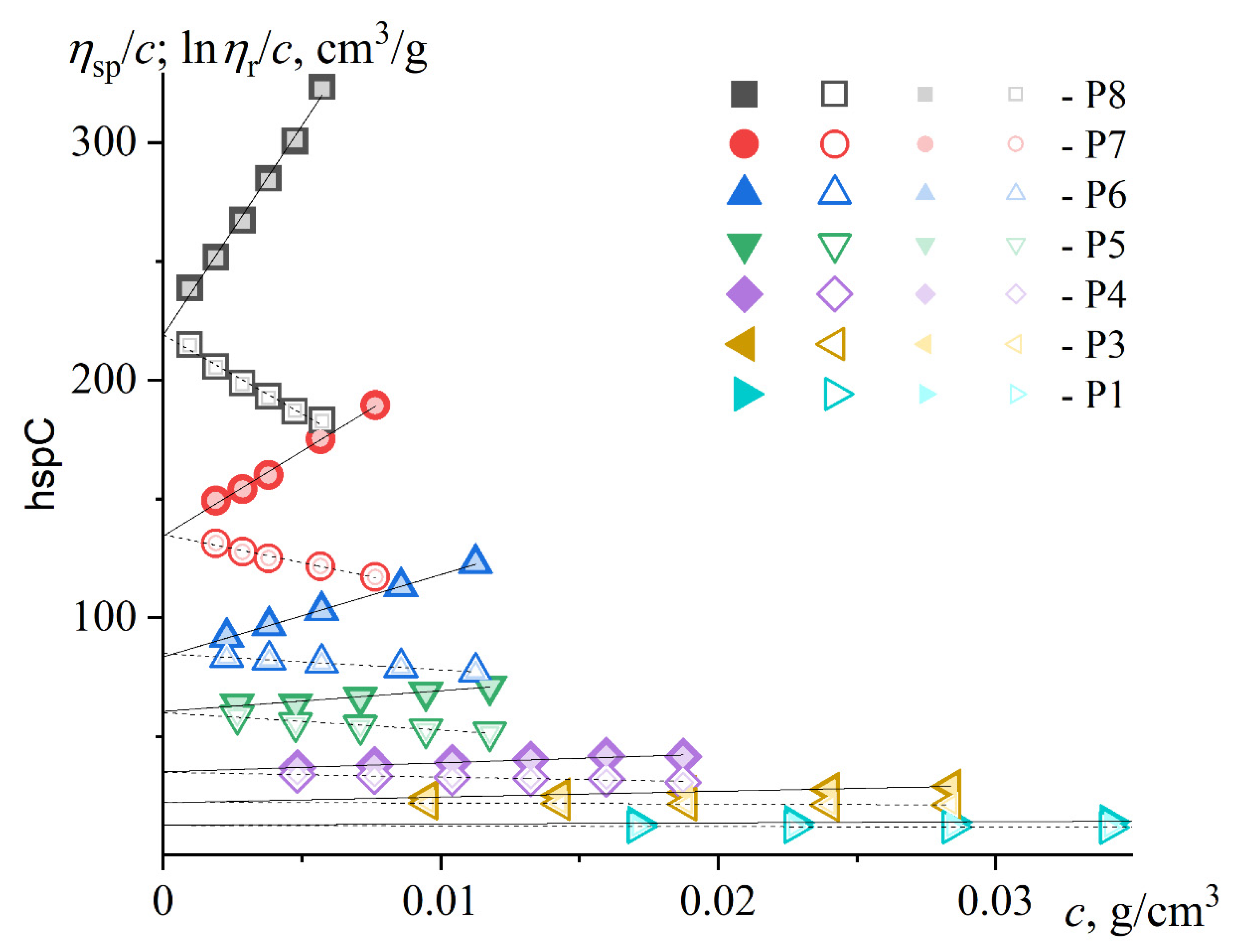

3.1. Viscometry

3.2. Densitometry

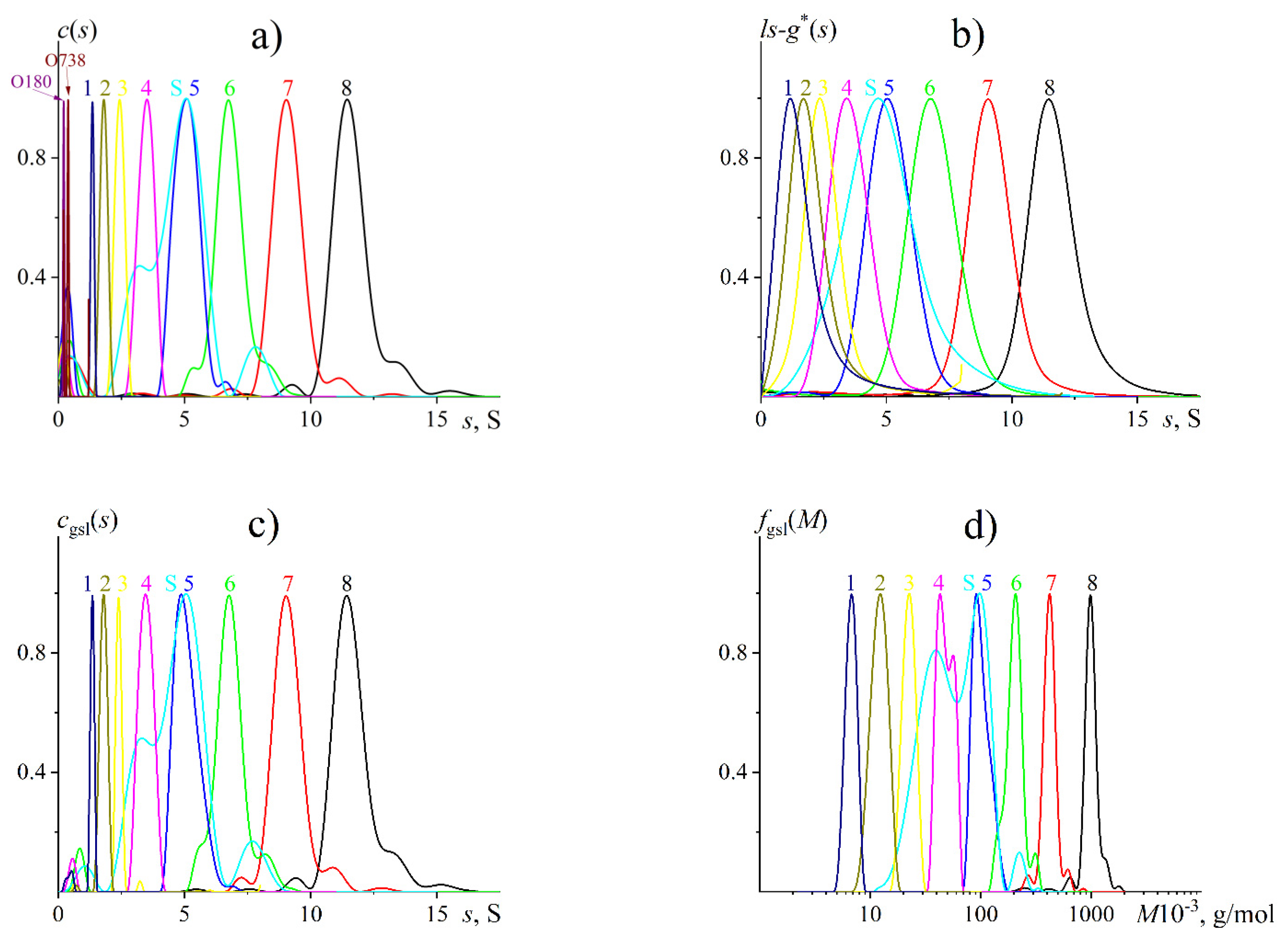

3.3. AUC

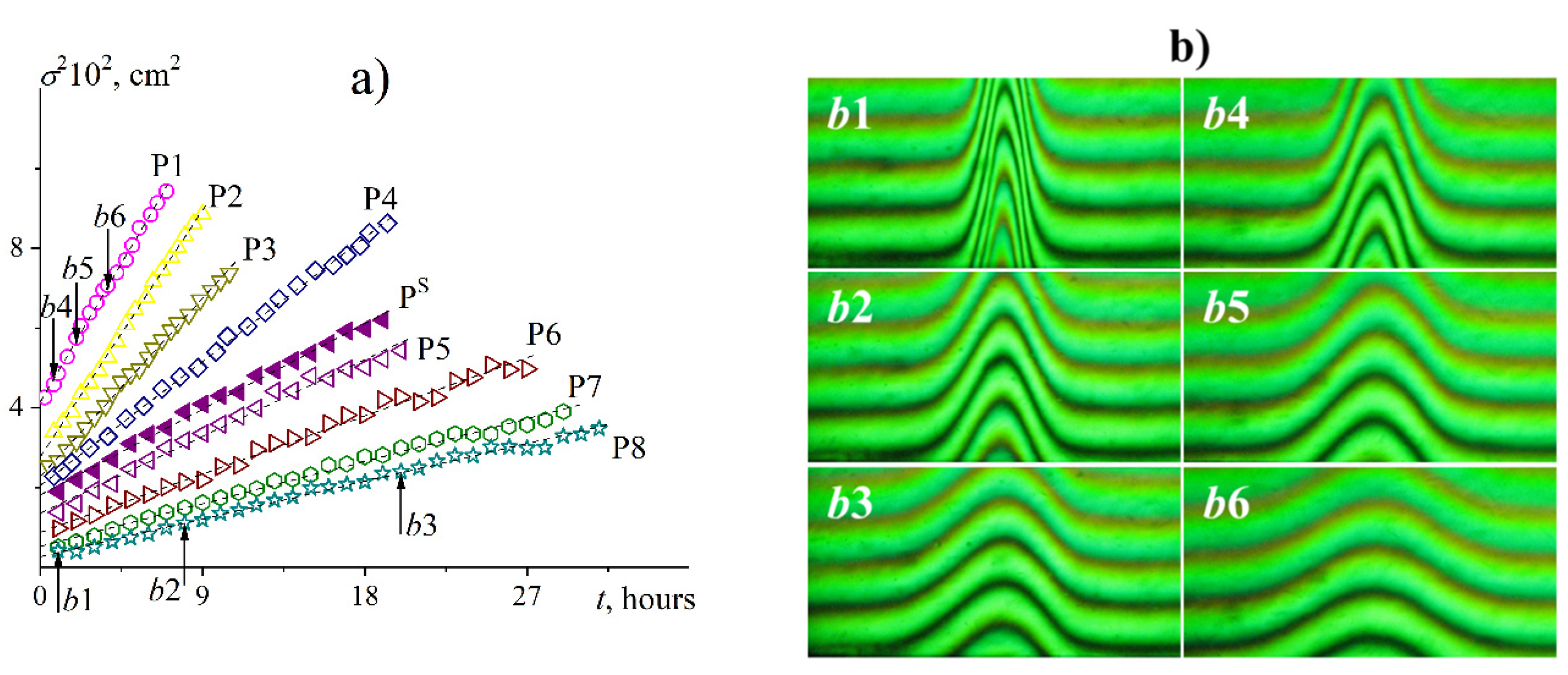

3.4. Diffusion Experiments and the Concept of Hydrodynamic Invariant

3.5. Refractive Index Increment

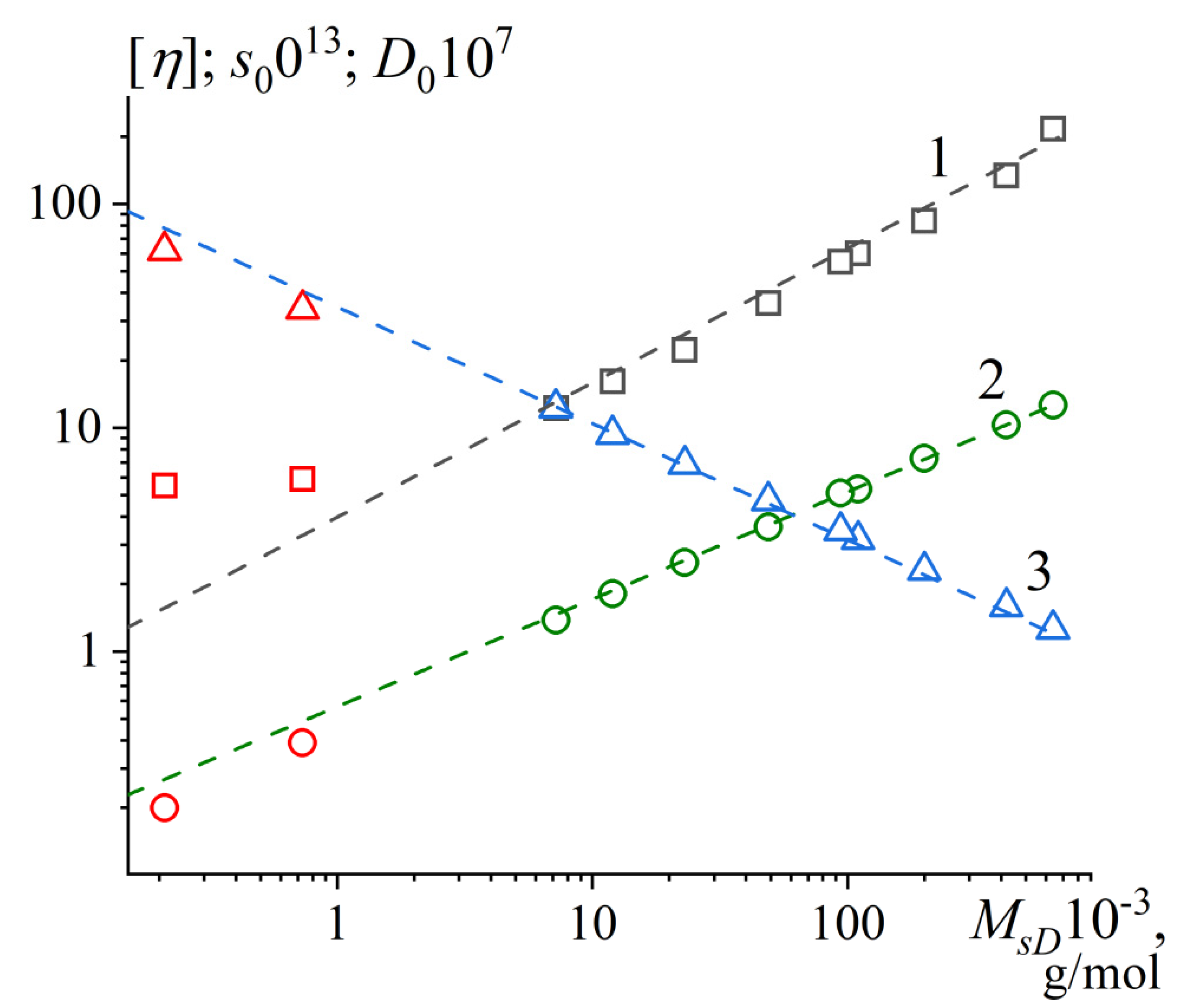

3.6. Hydrodynamic Scaling Relationships

| 1 | |||

| 0.62±0.02 | 0.044±0.009 | 0.9970 | |

| 0.49±0.01 | 0.017±0.001 | 0.9999 | |

| -0.51±0.01 | 1110±50 | -0.9998 |

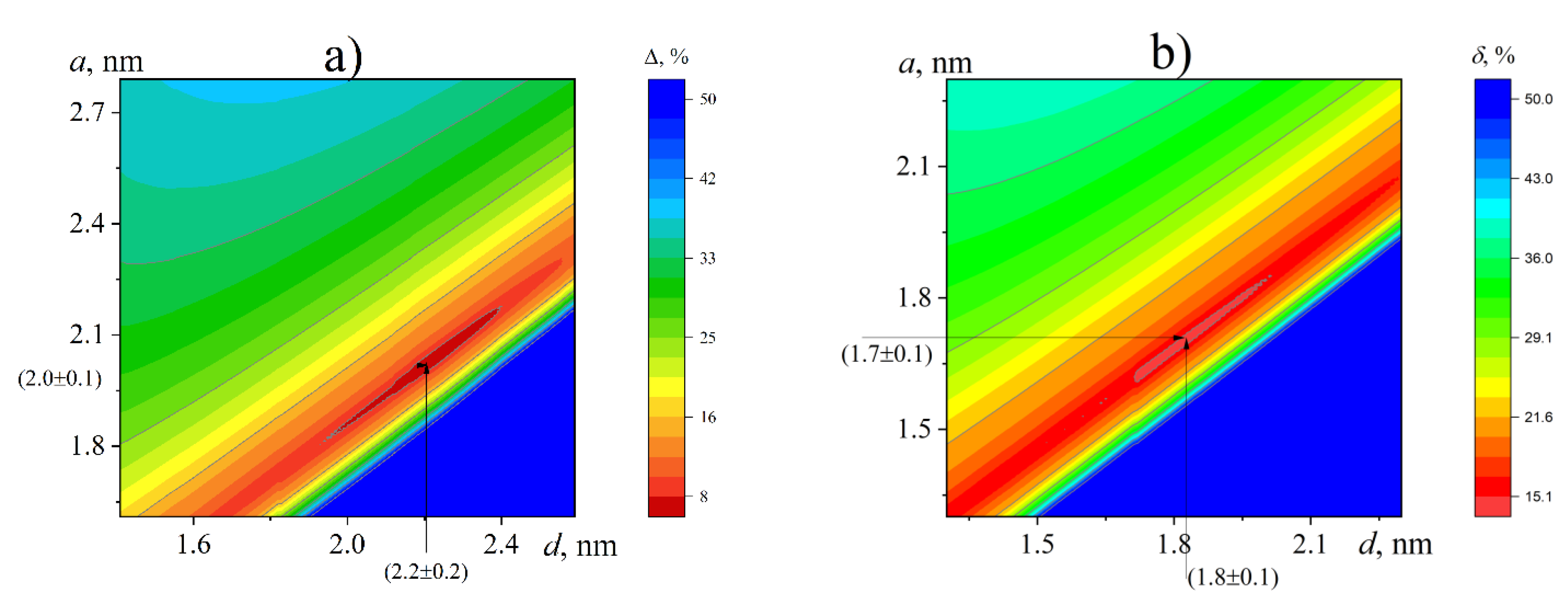

3.7. Determination of Conformational Parameters

3.8. Multi-HYDFIT Suite

| Solvent | Variables | Fixed values |

, nm |

, nm |

, g/(mol cm) |

Δ, % |

| DMF | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 1.2 | 12.7 | ||

| DMF | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 3.38 | 7.6 | ||

| H2O | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 14.8 | ||

| H2O | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 3.38 | 15.0 |

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leathers, T.D. Biotechnological production and applications of pullulan. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 62, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.S.; Kaur, N.; Singh, D.; Bajaj, B.K.; Kennedy, J.F. Downstream processing and structural confirmation of pullulan - A comprehensive review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 208, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, C.K.; Ghosh, T.; Lukhmana, N.; Tahiliani, S.; Priyadarshi, R.; Hoffmann, T.G.; Purohit, S.D.; Han, S.S. Pullulan as a sustainable biopolymer for versatile applications: A review. Materials Today Communications 2023, 36, 106477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R. Physiology of Dematium Pullulans de Bary. Zentralbl. Bacteriol. Parasitenkd. Infektionskr. Hyg. Abt. 2 1938, 98, 133–167. [Google Scholar]

- Bernier, B. THE PRODUCTION OF POLYSACCHARIDES BY FUNGI ACTIVE IN THE DECOMPOSITION OF WOOD AND FOREST LITTER. Can. J. Microbiol. 1958, 4, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Z. Polysaccharides-based nanoparticles as drug delivery systems. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2008, 60, 1650–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Budhwani, D.; Gurjar, P.; Telange, D.; Lambole, V. Pullulan based derivatives: synthesis, enhanced physicochemical properties, and applications. Drug Delivery 2022, 29, 3328–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danjo, T.; Enomoto, Y.; Shimada, H.; Nobukawa, S.; Yamaguchi, M.; Iwata, T. Zero birefringence films of pullulan ester derivatives. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 46342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.S.; Kaur, N.; Kennedy, J.F. Pullulan and pullulan derivatives as promising biomolecules for drug and gene targeting. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 123, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, L.M.; Oliveira, M.P.; Stapait, C.C.; Maric, M.; Santos, A.M.; Demarquette, N.R. Evaluation of different solvents and solubility parameters on the morphology and diameter of electrospun pullulan nanofibers for curcumin entrapment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 251, 117127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajalloueian, F.; Asgari, S.; Guerra, P.R.; Chamorro, C.I.; Ilchenco, O.; Piqueras, S.; Fossum, M.; Boisen, A. Amoxicillin-loaded multilayer pullulan-based nanofibers maintain long-term antibacterial properties with tunable release profile for topical skin delivery applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 215, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.H.Y.; Brameld, K.A.; Brant, D.A.; Goddard, W.A. Conformational analysis of aqueous pullulan oligomers: an effective computational approach. Polymer 2002, 43, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Moral, N.; Plankeele, J.-M.; Domoney, C.; Warren, F. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-size exclusion chromatography (UPLC-SEC) as an efficient tool for the rapid and highly informative characterisation of biopolymers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishinari, K.; Fang, Y. Molar mass effect in food and health. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 112, 106110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Okamoto, T.; Tokuya, T.; Takahashi, A. Solution properties and chain flexibility of pullulan in aqueous solution. Biopolymers 1982, 21, 1623–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, K.; Ohta, K.; Miyamoto, H.; Nakamura, S. Preparation and solution properties of pullulan fractions as standard samples for water-soluble polymers. Carbohydr. Polym. 1984, 4, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Katsuki, T.; Takahashi, A. Static and dynamic solution properties of pullulan in a dilute solution. Macromolecules 1984, 17, 1726–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buliga, G.S.; Brant, D.A. Temperature and molecular weight dependence of the unperturbed dimensions of aqueous pullulan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1987, 9, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, G.M.; Yevlampieva, N.P.; Korneeva, E.V. Flow birefringence of pullulan molecules in solutions. Polymer 1998, 39, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishinari, K.; Kohyama, K.; Williams, P.A.; Phillips, G.O.; Burchard, W.; Ogino, K. Solution properties of pullulan. Macromolecules 1991, 24, 5590–5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, G.M.; Korneeva, E.V.; Yevlampieva, N.P. Hydrodynamic characteristics and equilibrium rigidity of pullulan molecules. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1994, 16, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, S.; Patil, R.; Dubey, S.K.; Bahadur, P. Derivatization approaches and applications of pullulan. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 269, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorin, I.M.; Fetin, P.A.; Mikusheva, N.G.; Lezov, A.A.; Perevyazko, I.; Gubarev, A.S.; Podsevalnikova, A.N.; Polushin, S.G.; Tsvetkov, N.V. Pullulan-Graft-Polyoxazoline: Approaches from Chemistry and Physics. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.M. Synthesis of New Pullulan Derivatives for Drug Delivery. PhD Dissertation of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2013.

- Ostwald, W.; Malss, H. Über Viskositätsanomalien sich entmischender Systeme, I. Über Strukturviskosität kritischer Flüssigkeitsgemische. Kolloid-Zeitschrift 1933, 63, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, V.N.; Eskin, V.E.; Frenkel, S.Y. Structure of Macromolecules in Solution; The National Lending Library for Science and Technology: Boston, 1971; p. 762. [Google Scholar]

- Šesták, J.; Ambros, F. On the use of the rolling-ball viscometer for the measurement of rheological parameters of power law fluids. Rheol. Acta 1973, 12, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, M.L. The viscosity of dilute solutions of long-chain molecules. I. J. Phys. Chem. 1938, 42, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, E.O. Molecular Weights of Celluloses and Cellulose Derivates. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1938, 30, 1200–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimm, B.H. Dynamics of Polymer Molecules in Dilute Solution: Viscoelasticity, Flow Birefringence and Dielectric Loss. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1956, 24, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, W.; Kuhn, H. Bedeutung beschränkt freier Drehbarkeit für die Viskosität und Strömungsdoppelbrechung von Fadenmolekellösungen I. Helv. Chim. Acta 1945, 28, 1533–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratky, O.; Leopold, H.; Stabinger, H. The determination of the partial specific volume of proteins by the mechanical oscillator technique. Methods Enzymol. 1973, 27, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedberg, T.; Pedersen, K.O.; Bauer, J.H. The Ultracentrifuge; Oxford University Press: New York, 1940; p. 478. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R.L.; Williams, J.W. Boundary spreading in sedimentation velocity experiments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950, 72, 4325–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgman, W.B. Some Physical Chemical Characteristics of Glycogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1942, 64, 2349–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H. Mathematical Theory of Sedimentation Analysis. 1962.

- Signer, R.; Gross, H. Ultrazentrifugale Polydispersitätsbestimmungen an hochpolymeren Stoffen. 95. Mitteilung über hochpolymere Verbindungen. Helv. Chim. Acta 1934, 17, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, W.F. Boundary analysis in sedimentation transport experiments: A procedure for obtaining sedimentation coefficient distributions using the time derivative of the concentration profile. Anal. Biochem. 1992, 203, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigon, R.P.; Timasheff, S.N. Magnesium-induced self-association of calf brain tubulin. I. Stoichiometry. Biochemistry 1975, 14, 4559–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, G.; Stafford, W.; Minton, A.P. Characterization of Heterologous Protein–Protein Interactions Using Analytical Ultracentrifugation. Methods 1999, 19, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachman, H.K. Ultracentrifugation in biochemistry; Elsevier: 1959.

- Schuster, T.M.; Toedt, J.M. New revolutions in the evolution of analytical ultracentrifugation. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 1996, 6, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford III, W.F. Sedimentation velocity spins a new weave for an old fabric. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 1997, 8, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuck, P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and Lamm equation modeling. Biophys. J. 2000, 78, 1606–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuck, P.; Rossmanith, P. Determination of the sedimentation coefficient distribution by least-squares boundary modeling. Biopolymers 2000, 54, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandrup, J.; Immergut, E.H.; Grulke, E.A. Polymer Handbook, 2 Volumes Set, 4-th ed.; Wiley: New York, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lamm, O. Die differentialgleichung der ultrazentrifugierung. Ark. Mat. Astr. Fys. 1929, 21B, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, D.L. A Technique for the Numerical Solution of Certain Integral Equations of the First Kind. J. ACM 1962, 9, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, S.E.; Schuck, P.; Abdelhameed, A.S.; Adams, G.; Kök, M.S.; Morris, G.A. Extended Fujita approach to the molecular weight distribution of polysaccharides and other polymeric systems. Methods 2011, 54, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, G.M.; Perevyazko, I.Y.; Okatova, O.V.; Schubert, U.S. Conformation parameters of linear macromolecules from velocity sedimentation and other hydrodynamic methods. Methods 2011, 54, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nischang, I.; Perevyazko, I.; Majdanski, T.; Vitz, J.; Festag, G.; Schubert, U.S. Hydrodynamic Analysis Resolves the Pharmaceutically-Relevant Absolute Molar Mass and Solution Properties of Synthetic Poly(ethylene glycol)s Created by Varying Initiation Sites. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubarev, A.S.; Monnery, B.D.; Lezov, A.A.; Sedlacek, O.; Tsvetkov, N.V.; Hoogenboom, R.; Filippov, S.K. Conformational properties of biocompatible poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)s in phosphate buffered saline. Polymer Chemistry 2018, 9, 2232–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrenko, V.P.; Gubarev, A.S.; Lavrenko, P.N.; Okatova, O.V.; Pavlov, G.M.; Panarin, E.F. Processing of Digital Interference Images Obtained on Tsvetkov Diffusometer. Ind. Lab. Materials Diagnostics 2013, 79, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Berne, B.J.; Pecora, R. Dynamic Light Scattering: With Applications to Chemistry, Biology, and Physics; Dover Publications, Inc.: N.Y, 1976; p. 376. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S.E. The intrinsic viscosity of biological macromolecules. Progress in measurement, interpretation and application to structure in dilute solution. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1997, 68, 207–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, G.M.; Gubarev, A.S. Intrinsic Viscosity of Strong Linear Polyelectrolytes in Solutions of Low Ionic Strength and Its Interpretation. In Advances in Physicochemical Properties of Biopolymers (Part 1), Masuelli, M., Renard, D., Eds.; Bentham Science Publishers: UAE, 2017; pp. 433–460. [Google Scholar]

- Gosteva, A.; Gubarev, A.S.; Dommes, O.; Okatova, O.; Pavlov, G.M. New Facet in Viscometry of Charged Associating Polymer Systems in Dilute Solutions. Polymers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perevyazko, I.Y.; Gubarev, A.S.; Pavlov, G.M. Analytical ultracentrifugation and combined molecular hydrodynamic approaches for polymer characterization. In Molecular Characterization of Polymers: A Fundamental Guide, Malik, M.I., Mays, J., Shah, M.R., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2021; pp. 223–257. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov, G.M.; Frenkel, S.Y. About the concentration dependence of macromolecule sedimentation coefficients (in Russian). Vysokomol. Soedin., Ser. B 1982, 24, 178–180. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov, G.; Frenkel, S. Sedimentation parameter of linear polymers. Analytical Ultracentrifugation 1995, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, G.M.; Korneeva, E.V.; Smolina, N.A.; Schubert, U.S. Hydrodynamic properties of cyclodextrin molecules in dilute solutions. Eur. Biophys. J. Biophys. Lett. 2010, 39, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuck, P.; Zhao, H.; Brautigam, C.A.; Ghirlando, R. Basic Principles of Analytical Ultracentrifugation; CRC Press: 2016.

- Kroe, R.; Laue, T. NUTS and BOLTS: Applications of fluorescence-detected sedimentation. Anal. Biochem. 2009, 390, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online:. Available online: www.nanolytics.com (accessed on Nov. 2024).

- Tsvetkov, V.N. Rigid-chain polymers; Consult. Bureau. Plenum.: London, 1989; p. 490. [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetkov, V.N.; Lavrenko, P.N.; Bushin, S.V. Hydrodynamic invariant of polymer molecules. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 1984, 22, 3447–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, G.M. The concentration dependence of sedimentation for polysaccharides. Eur Biophys J 1997, 25, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grube, M.; Cinar, G.; Schubert, U.S.; Nischang, I. Incentives of Using the Hydrodynamic Invariant and Sedimentation Parameter for the Study of Naturally- and Synthetically-Based Macromolecules in Solution. Polymers 2020, 12, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, G.M. Different Levels of Self-Sufficiency of the Velocity Sedimentation Method in the Study of Linear Macromolecules. In Analytical Ultracentrifugation: Instrumentation, Software, and Applications, Uchiyama, S., Arisaka, F., Stafford, W., Laue, T., Eds.; Springer Japan: Tokyo, 2016; pp. 269–307. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov, G.; Finet, S.; Tatarenko, K.; Korneeva, E.; Ebel, C. Conformation of heparin studied with macromolecular hydrodynamic methods and X-ray scattering. Eur Biophys J 2003, 32, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, H.B.; Bloomfield, V.A.; Hearst, J.E. Sedimentation Coefficients of Linear and Cyclic Wormlike Coils with Excluded-Volume Effects. J. Chem. Phys. 1967, 46, 1493–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, A.; de la Torre, J.G. Equivalent Radii and Ratios of Radii from Solution Properties as Indicators of Macromolecular Conformation, Shape, and Flexibility. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 2464–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós, D.; Ortega, A.; de la Torre, J.G. Hydrodynamic Properties of Wormlike Macromolecules: Monte Carlo Simulation and Global Analysis of Experimental Data. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 5788–5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, J.G. Single-HYDFIT, Multi-HYDFIT and HYDROFIT. Available online: http://leonardo.inf.um.es/macromol/programs/hydfit/hydfit.htm (accessed on Nov. 2024).

- Pavlov, G.M.; Panarin, E.F.; Korneeva, E.V.; Kurochkin, C.V.; Baikov, V.E.; Ushakova, V.N. Hydrodynamic properties of poly(1-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) molecules in dilute solution. Makromolek. Chemie 1990, 191, 2889–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, H. Modern Theory of Polymer Solutions; Harper and Row: New York, 1971; p. 434. [Google Scholar]

- Gubarev, A.S.; Okatova, O.V.; Kolbina, G.F.; Savitskaya, T.A.; Hrynshpan, D.D.; Pavlov, G.M. Conformational characteristics of cellulose sulfoacetate chains and their comparison with other cellulose derivatives. Cellulose 2023, 30, 1355–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, T.; Norisuye, T.; Fujita, H. Dilute Solution of Bisphenol A Polycarbonate. Polym. J. 1975, 7, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Batch No. | , g/mol | Ɖ | , g/mol |

| P8 | 20908-3 | 788 | 1.23 | 640 |

| P7 | 20907-2 | 404 | 1.13 | 420 |

| P6 | 20906-2 | 212 | 1.13 | 200 |

| P5 | 20905-2 | 112 | 1.12 | 110 |

| PS* | P4516 | 100 | - | 94 |

| P4 | 20904-2 | 47.3 | 1.06 | 49 |

| P3 | 20903-2 | 22.8 | 1.07 | 23 |

| P2 | 20902-2 | 11.8 | 1.1 | 12 |

| P1 | 20901-2 | 5.9 | 1.09 | 7.2 |

| O730 | 20910-1 | 0.738 | 1 | 0.73 |

| O180 | 20909-1 | 0.180 | 1 | 0.21 |

| Sample | Ostwald viscometer | Höppler viscometer | ,% | ||||

| ,cm3/g | ,cm3/g | ||||||

| P8 | 213 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 219 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 2.8 |

| P7 | 133 | 0.4 | 0.13 | 135 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 1.5 |

| P6 | 84 | 0.47 | 0.11 | 84 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0 |

| P5 | 59.2 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 60.2 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 1.7 |

| PS | 55 | 0.45 | 0.11 | 54 | 0.55 | 0.08 | -1.8 |

| P4 | 36.9 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 34.9 | 0.31 | 0.17 | -5.4 |

| P3 | 21.4 | 0.46 | 0.09 | 22.1 | 0.51 | 0.08 | 3.3 |

| P2 | 15.8 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 16.3 | 0.42 | 0.12 | 3.2 |

| P1 | 11.9 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 12.5 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 5 |

| Sample |

, cm3/g |

, cm2/s |

, s |

, cm3/g |

, mol-1/3 |

, cm2g/ (s2K mol1/3) |

, g/mol |

|

| P8 | 216 | 1.26 | 12.6 | 230 | 1.4 | 3.78 | 640 | 760 |

| P7 | 134 | 1.59 | 10.3 | 198 | 1.3 | 3.53 | 420 | 490 |

| P6 | 84 | 2.31 | 7.3 | 93 | 1.2 | 3.46 | 200 | 240 |

| P5 | 60 | 3.17 | 5.3 | 47 | 1.1 | 3.43 | 110 | 130 |

| PS | 55 | 3.47 | 5.1 | 60 | 1.2 | 3.49 | 94 | 110 |

| P4 | 36 | 4.73 | 3.6 | 25 | 1.0 | 3.32 | 49 | 58 |

| P3 | 22.2 | 6.86 | 2.5 | 27 | 1.1 | 3.20 | 23 | 28 |

| P2 | 16.1 | 9.37 | 1.8 | 3.18 | 12 | 15 | ||

| P1 | 12.2 | 12.27 | 1.38 | 3.17 | 7.2 | 9 | ||

| O730 | 5.9 | 34 | 0.39 | 3.22 | 0.73 | 0.9 | ||

| O180 | 5.5 | 62 | 0.2 | 3.77 | 0.21 | 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).