1. Introduction

Celiac disease (CelD) and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are gastrointestinal disorders, characterized by abnormal immune responses, resulting in disrupted immune pathways [

1].

CelD is triggered by gluten exposure in genetically susceptible population, HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 being the involved genotypes. The diagnosis is established characteristically within the first two years of life, after complementary feeding initiation, with another peak-onset later in life, in the second decade [

2,

3]. Diagnosis of CelD is confirmed upon European Society of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition’s (ESPGHAN) recommendations and is based on a combination of clinical, serologic and histopathological changes [

4]. Growth impairment is a well encountered manifestation in CelD. In a recent study, failure to thrive was the most prevalent symptom, reported in 31% of the cases at diagnosis by Almahmoud

et al. [

5]. It is well known that gluten-free diet (GFD) is, at this moment, the only treatment strategy for CelD patients, that being translated in major dietary limitations. [

6]. Dietary adherence in children ranges widely from 23-98%, regardless of the technique used to asses compliance [

7]. Existing research suggests that GFD is associated with potential risk factors like trace elements deficit, excessive carbohydrate and lipids intake and fatty liver disease [

8].

Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (pIBD) is the most common chronic gastrointestinal disorder taken care by pediatric gastroenterologists, with a marked increase in the incidence and prevalence globally in the last decades [

9,

10]. The main spectrum of pIBD includes three main entities: Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and inflammatory bowel disease - unclassified (IBD-U), according to European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Porto criteria [

11]. Based on current literature, diet plays a crucial role in IBD pathogeny and hence represents an encouraging target for therapeutic strategies, an increasing interest in researching this domain being lately observed. Recent reports by Gerasimidis

et al. suggest that with the exception of exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) indicated for active CD there is currently insufficient evidence to formulate other specific dietary recommendations for the management of pIBD [

12]. However, patients with IBD are frequently exposed to diet manipulation during the disease course, both in UC and CD whether as a specific intervention or as adjunct therapy, in order to enhance the response to standard medical regimens or in an effort to manage associated functional abdominal symptoms [

13].

Ishige

et al. report that at diagnosis, 3 to 10% of the children diagnosed with UC and 15 to 40% with CD associate growth failure [

14]. They further note that the risk is highest among patients with pre-pubertal onset CD, potentially resulting in a final adult height up to 8 cm lower than controls [

9]. Moreover, malnutrition may be the consequence of the combination between disease activity and dietary restrictions [

15].

Food and eating habits serve multiple purposes beyond their fundamental physiological functions. While essential for ideal growth and development and in their long-term health, food is involved also in our social life and also is capable to influence our emotions and our day-to-day living. These aspects collectively define food-related quality of life (FR-QoL). A diagnosis like IBD may disrupt these psychosocial components of eating, leading to an avoidance of different social, cultural or religious events involving food and moreover, shifting the perception, considering food and as much as shopping for grocery or preparing a meal a source of concern rather than enjoyment [

16].

To measure the FR-QoL in IBD, a specific questionnaire FRQoL-29 was developed and validated in adult patients with IBD which was used subsequently in numerous studies. An agreed conclusion is that patients with IBD experience decreased FR-QoL compared with healthy control, other chronic diseases like asthma or when compared to functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract [

17,

18].

For CelD, there is no formulated unidimensional instrument for specifically assessing the FR-QoL. HR-QoL was proposed to be evaluated with the specific Celiac disease Dutch Questionnaire (CDDUX) formulated in 2008 by van Doorn

et al. in a study population that included patients with CelD and a control group consisting of patients with asthma, rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes. The questionnaire includes 12 items divided into three different scales, scale “communication”, scale “having CelD” and scale “diet” [

19].

As stated above, although nutritional interventions are the only therapeutic intervention for CelD, this requires lifelong adherence to specific cautious and also challenging eating behavior. In comparison, most of pIBD patients, including UC are at one point in their evolution subjected to diet interventions either indicated by the treating physician or self-initiated.

Existing literature indicates that FR-QoL is impaired in children with CD when compared to healthy population. However, studies comparing FR-QoL between the two main types of IBD, or between IBD and other organic gastrointestinal disorders to our knowledge, are lacking.

Our aim is to evaluate the FR-QoL and compare its impact across UC and CD, as well as CelD, a condition where dietary management is the cornerstone.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional study including 51 children diagnosed with IBD and CelD followed in “Grigore Alexandrescu” Emergency Hospital for Children in Bucharest Romania, performed between April 2024 and November 2024. Study population was further divided in three subgroups, 17 children with CD, 17 children diagnosed with UC and 17 children with CelD. Children were included in the study if they were diagnosed with IBD at least 3 months prior to inclusion according to ESPGHAN guidelines [

20], while included patients with CelD had to be diagnosed at least 6 months before enrollment, according to ESPGHAN guidelines [

4]; all children were included in the study during their routine disease assessment, if they were 7 years or older. The exclusion criteria were: exclusive enteral nutrition, use of parenteral nutrition (total or partial) or surgery in the last 3 months for IBD subgroup and incomplete ESPGHAN criteria for diagnosis of CelD in this subgroup of patients. Consent from their legal guardian was obtained for all the children.

Participants were provided with the translated Romanian version of the questionnaire at the time of their evaluation and were asked to complete it at home, within a week at most. For the CelD patients, questionnaires were modified with “CelD” instead of “IBD”. The completed questionnaires were electronically returned for ease of collaboration. All children completed the survey by themselves except for one 8-years old patient in the IBD subgroup and two children, an 8 years-old boy and a 7 years-old girl with CelD who required assistance from their parents.

The self-reported FR-QoL-29 questionnaire comprises 29 items with a 5-point Likert response scale, ranging from 1 (

definitely agree) to 5 (

definitely disagree) evaluating different aspect of eating and drinking, in the last two weeks. Results range from a maximum score of 145 points, indicating unaffected FR-QoL, to 45 points denoting a substantial negative impact [

21]. Four questions (8, 9, 24, 25) have positive expressions so, when calculated, the score was reversed in order to associate the highest scores with a positive response and respectively, the lowest ones with a negative one for the accurate appreciation of internal consistency within the questionnaire.

Demographic and clinical data were collected. The disease extension and behavior for IBD patients were categorized according to EPSGHAN’s Paris classification [

20]. Additionally, history of surgery and medical treatment regimens were noted. For the CelD subgroup adherence to GFD was assessed using the tissue transglutaminase testing IgA or IgG in case of IgA specific deficit and patients’ self - reports.

Anthropometric (weight, height) data were collected and the nutritional status was appreciated using the conversion of the body mass index (BMI, kg/m

2) into standardized Z-scores and classified according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) references for children 2-20 years, as follows: BMI<5

th percentile – “underweight”, BMI ≤ 5

th to <85

th percentile –“healthy weight”, BMI ≤85

th percentile to <95

th percentile – “overweight”, BMI ≤95

th percentile to<120% of the 95

th percentile and <35 kg/m2 – “class I obesity”, BMI ≤120% to <140% of the 95

th percentile or ≤35kg/m2 (whichever is lower) – “class II obesity” and BMI ≤140% of the 95

th percentile or ≤ 40kg/m2 (whichever is lower) –“class III obesity” for a uniform assessment [

22]. For IBD patients, disease activity was evaluated using Physician Global Assessment (PGA) and the specific activity indexes like Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Index (PUCAI) for UC and weighted Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (wPCDAI) for CD. According to PGA, the overall disease activity was categorized into quiescent = 0, mild =1, moderate =2 and severe=3 [

23].

The wPCDAI is measured on a 0 to 125 scale, <12.5 points indicating remission, 12-40 points indicating mild activity, >40-57.5 points indicating moderate disease and scores higher than 57.5 up to the maximum of 125 being indicator of severe disease [

24]. The PUCAI score classifies UC as remission <10 points, mild activity 10 to 34 points, moderate activity 35 to 64 points and scores > 65 points (up to 85) indicating severe colitis [

25]. Treatment was categorized into: Crohn’s disease exclusion diet (CDED) in association with partial enteral nutrition (PEN), 5-aminosalicilates (5-ASA), immunomodulator (IMM, azathioprine), infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA) and strict GFD for CelD patients. Patients receiving more than one intervention were included in each corresponding category.

The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (# 43/31.10.2024).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS v26 (Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were computed for both continuous and categorical variables. Continuous variables were evaluated for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For continuous variables the mean/median with standard deviations (SD) or interquartile range (IQR) as appropriate were used, regarding their distribution. For categorical variables both the Chi-square test and Fisher’s Exact Test were performed. Fisher’s Exact Test was preferred in cases where sample sizes were small or where expected frequencies in contingency table cells were below 5, ensuring robustness and accuracy of the p-values. For the not normally distributed data, the Mann-Whitney U Test (a non-parametric test) was applied to compare medians between groups. To compare means of continuous variables between more than two groups, One-Way Anova was used for the normally distributed data and the Kruskal-Wallis one-way for the non-normally distributed data. Independent-T-test was used to compare means of normally distributed variables. Pearson and Spearman’s nonparametric correlation coefficient test were employed to assess relationships between different variables according to the type of data distribution. Post-hoc analysis was performed for ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis, when significant differences were found between groups. A p value < 0.05 was considered as the threshold for statistical significance. Internal consistency of the instrument was evaluated using Cronbach alpha. The accepted 0.7 threshold indicating a good internal consistency was used.

3. Results

A total of 51 children were enrolled, median age [IQR] at inclusion was 15 [12-17] years; 17 were diagnosed with CD, 17 with UC respectively and 17 patients were diagnosed with CelD, with 41.2% (n=21) boys in the entire study population. Median [IQR] age at diagnosis was 11 [4.3-14] years, significantly lower for CelD patients. Ileocolonic extension was the most frequent disease involvement for CD, with inflammatory (B1) behavior. For UC, pancolonic involvement was the most prevalent. The duration of evolution until enrollment was significantly longer in CelD subgroup. Strict GFD was the majority in CelD patients, 94.1% (n=16). Most of the patients were in the “normal weight” category. Patients’ characteristics are described in

Table 1.

To evaluate the internal consistency of the questionnaire items, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the 29 items responses. The analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of.0.910, indicating a high level of internal consistency. This suggests that the items are highly correlated and reliably measure the same underlying construct.

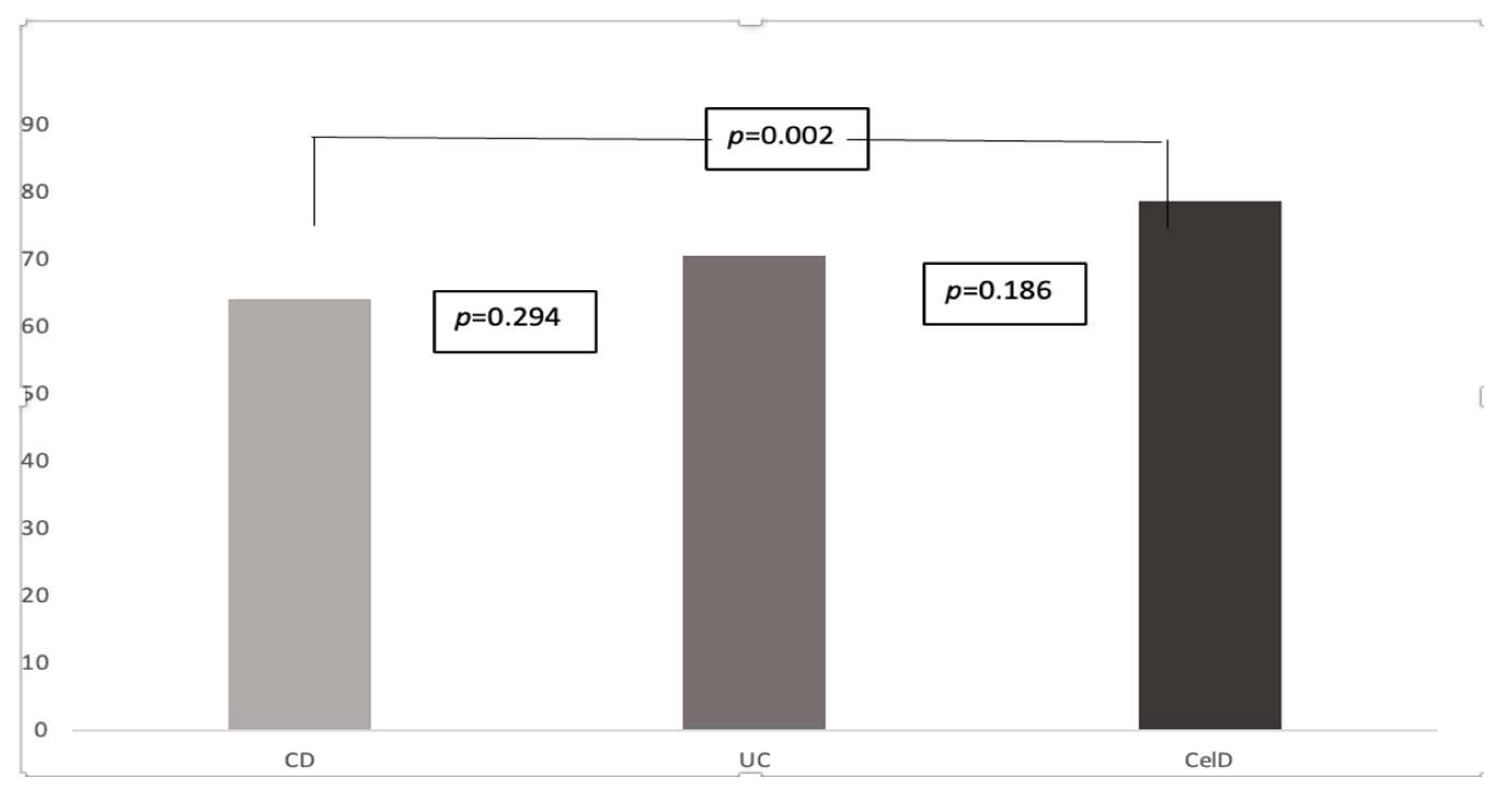

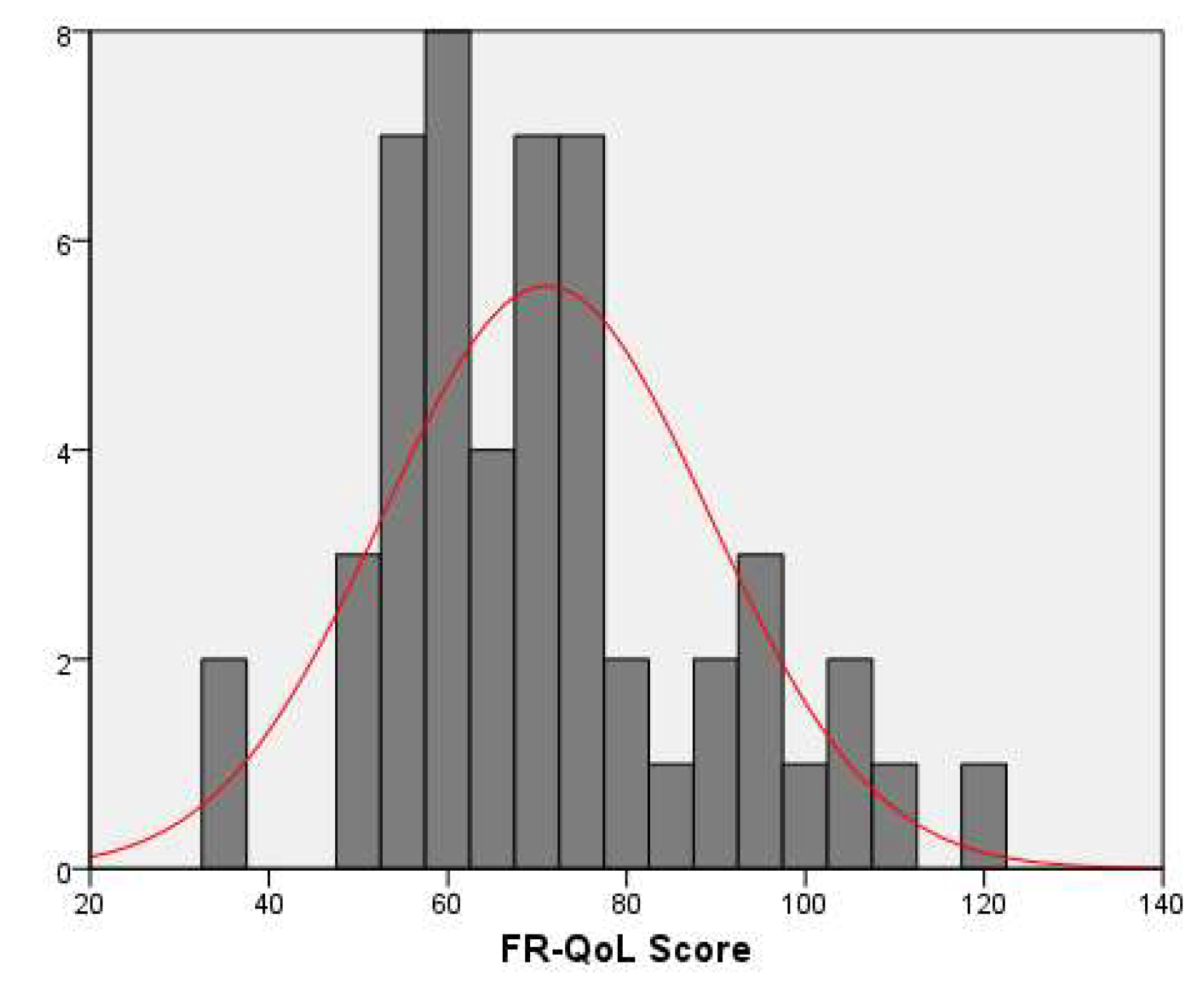

Overall, the entire study population associated a relatively low mean (SD) FR-QoL score of 71.03±18.3 (

Figure 1). Scores were similar between genders, 71.2±18.6 for girls and 70.9±18.3 for boys, p=0.953.

FR-QoL scores were negatively correlated with age at inclusion (Spearman’s ρ=-0.284, p=0.04) and with age at diagnosis (Spearman’s ρ=-0.291, p=0.038). No significant correlation was observed between the scores and duration of evolution, Spearman’s ρ=-0.170, p=0.234.

Most patients, both with CD and UC, were in remission (76.5%, n=26), according to specific activity scores. Median PUCAI was 0[0-40] while median wPCDAI was 5[0-7.5]. No differences were observed in the FR-QoL scores between the two subgroups (66.2±17.8 for the remission group and 77.25±15.2 for the active disease group, p=0.124). History of surgery did not influence the scores (61.83±7 for the positive history group vs. 70.32±18.9 for the negative group, p=0.291). Similar findings were observed when analyzing the extension or the behavior of the disease (

Table 2).

According to disease type, scores were significantly lower for the IBD subgroup, 67.3±16.1 for IBD vs.78.6±20.3 for the CelD patients, p=0.036. At a further post-hoc analysis, between all three diseases subtypes, only CD scores (64.1±13.4) differed significantly from the CelD results, p=0.02, with no statistically difference between IBD subgroups (70.5±18.2 for UC patients), p=0.294 nor between UC and CelD patients, p=0.186 (

Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Fr-QoL scores according to disease type. CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; CelD, celiac disease.

Figure 2.

Fr-QoL scores according to disease type. CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; CelD, celiac disease.

The majority (80.4%, n=41) of patients included in the study were categorized as “healthy weight”. Mean FR-QoL scores were similar between the “normal/overweight” and “underweight” groups, 70.3±17.9 vs. 74.1±20.3, p=0.560.

Interestingly, scores were negatively correlated with weight, Pearson’s r = -0.347, p=0.013 and with height, Spearman’s ρ=-0.364, p=0.009.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to address the evaluation of FR-QoL between two chronic gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric pathology, even more so in Romania. Although not designated for CelD, upon completion of the FR-QoL by CelD patients, some comparison can be made because of similar food-related concerns, in lack of a specific construct that addresses this issue entirely.

Several authors highlighted the aspect of living with CelD in recent papers. Besides the periodic medical assessments, potential complications and lifelong monitoring, CelD also implies a high level of dietary caution. Anxiety about cross-contamination of certain foods and the possible occurrence of digestive and also extraintestinal symptoms associated with ingesting gluten-contaminated food, represents a possibility for developing eating disorders. Constant checking ingredient lists, food menus and avoidance of public dining situations can limit socializing and exposure to potential beneficial experiences while increase the feeling of discrimination [

26,

27].

Because of lifelong, strict interventions in an area which is an essential part of day-to-day living, the GFD, in terms of quality of life (QoL) this burden becomes obvious and besides specific evaluation, patients with CelD need to be assessed from this point of view also [

28].

Family’s perception of CelD’s impact is different. Mothers report greater lifestyle changes and burden being challenged managing gluten-free diets while fathers are experiencing guilt for genetic contribution [

7].

In a recent study that analyzed the adjustments that children and adolescents with CelD make in order to take part in various activities including food, the author found that almost all patients “always” adhere to the diet and their actions involve cognitive strategies that extend well beyond simply refraining from gluten-containing food [

29].

The particular aspects of adolescence as a time of emotional transition, which coincides to the peak incidence of IBD, makes the diagnosis of a chronic illness in this time-period to have a significant impact from a psychosocial point of view, not only on patients but also on the family [

30,

31].

From the patient’s perspective, living with IBD implies lifestyle adjustments and behavior adaptation regimens. Daily medication, periodic medical assessments and last, but not least diet interventions which may vary roughly depending on the disease evolution and on the health-care provider, are common aspects among IBD patients [

32].

Patients often turn to the internet for dietary guidance when comprehensive advices from the treating physician on appropriate diets are lacking, which may be a source of misinformation [

33]. Diet became a major concern for patients with IBD, either because of the specific recommendations and restrictions or because they believe that this is safer than the medical therapies, with 60% of them reporting to control their symptoms and extend the periods of remission through manipulation of diet, mainly avoiding foods and drinks observed to trigger intestinal symptoms, an adaptation mechanism defined as perceptive eating [

32,

34,

35]. Finding what food they can and cannot tolerate is a process of “trial and error”, as suggested by de Vries

et al. [

34]. In order to limit their intestinal symptoms, guided by past experiences or driven by the anticipated fear of harmful effects, patients may even develop eating behaviors like Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorders (ARFID) [

36].

Following diagnosis, approximately half of the patients with IBD modify their dietary habits, implementing varying degrees of food restrictions, [

37] most adults avoiding spicy food and gluten while identifying rice as the primary dietary component believed to prevent flare-ups and alleviate symptoms [

38]. Children with IBD are reporting an avoidance behavior towards foods in approximately half of the cases. According to Diederen

et al., common avoided foods were, in descending order: spicy food, fat-dense products, dairies, cereal-based products, onion/leek, bell pepper, refined sweets, meat and sodas while their diet is rich in vegetables, monounsaturated, and poly-unsaturated fatty acids [

39]. In our study, we observe a tendency towards lower scores, irrespective of the disease. As reported recently by Subramanian

et al., both adults and children with autoimmune gastrointestinal diseases (CD, UC, CelD) are at risk for developing eating disorders, the risk in children being more than twice higher comparative with children with non-immune digestive disorders [

40]. These reports may underestimate the true prevalence of the wide range of possible eating disorders because the study takes into consideration only disorders diagnosed and classified according to ICD-9 codification.

Our results indicate that FR-QoL scores were increasing as the age at inclusion and age at diagnosis were lower. We speculate this may indicate that in younger ages, the family may take-over the burden of the diet, especially in this time-frame when social activities including food are not yet intensely and independently explored. Parents of IBD patients regard diet as a challenging situation after IBD diagnosis; they are dissatisfied by the lack of personalized dietary interventions and by the inconsistences of provided nutritional advices [

41]. Furthermore, younger ages at diagnosis allow patients to get accustomed with a specific diet intervention that become a default way of living. This is contrary to what Brown

et al. observed in their study that included pediatric CD patients and their healthy siblings, that the FR-QoL scores increased as the age was older, suggesting developing of coping techniques in relation to their eating behavior over time [

42].

Factors that influence FR-QoL were analyzed in a recent systematic review by Zhu

et al. that comprised five studies, The authors report a positive correlation in children with CD between FR-QoL and age, wight, height, BMI. They also observed that patients in remission presented with higher FR-QoL scores than patients with active disease [

43]. Furthermore, Jiang

et al. report in a study comprising adults with IBD that for UC the activity and endoscopy scores indicating active disease, correlated with lower FR-QoL scores [

44].

In the current study, we did not observe any correlation between disease activity and FR-QoL scores, most probably because most patients were in clinical remission. Further analysis including endoscopic scores or mucosal inflammation markers, like fecal calprotectin, may be needed in order to precisely evaluate the FR-QoL in relation to disease activity, in larger populational samples.

Our results show significant lower FR-QoL in patients with CD when compared with UC group and CelD. These are in concordance to previous reports of a reduced impact of diet in patients with UC, compared to CD [

37]. Previous studies in adults, indicate that once adherence to GFD is achieved, HR-QoL shows improvement at the same or even higher level than the general population [

18]. These last observations could be attributed to the increased accessibility of gluten-free products. Gluten-free products market worths almost seven billion dollars and is expected to grow up to 14 billion in the next 10 years [

45]. Also, better tasting of such products has been attained. Together, these achievements transformed GFD in an easier to bear dietary interventions [

46]. Furthermore, despite the significant dietary modifications and adjustments required in food-related situations, children with CelD report medium to high HR-QoL [

47].

Counterintuitive at first sight, we report negatively correlations between FR-QoL scores in CD patients and anthropometric indices like weight, height and BMI, but not with the Z-score for BMI, contrary to the findings of Brown

et al. which reported positive correlations [

42]. One possible explanation for our observations may be the fact that most patients in our study were within normal weight range and we did not identify any correlation with disease activity, which may be a potential co-founder.

Limited research exists on FR-QoL in pediatric patients, with most comparisons drawn from adult populations. However, various observations provide more accurate insights into the diversity of factors that may influence FR-QoL.

Although valuable to the not so well-known general picture of FR-QoL in children with chronic gastrointestinal diseases, our study has some limitations. First of all, we are facing a relatively small sample size of the study population in each subgroup. The self-report nature of the assessment can entail validity issues, as exaggerating or underreporting symptoms, dependent on the patient’s disposition at the time of completing the questionnaire, or as described in the medical literature because of a behavior similar to the “Hawthorne effect” [

48], which may be a source of biased responses caused by change in children’s attitude in the context of a medical evaluation. A longitudinal evaluation through repeated questionnaires at different times would be more accurate in evaluating the FR-QoL. Also, we did not take into account patient’s intellectual limitations nor psychological and emotional aspects.

5. Conclusions

In line with current dietary guidelines and due to the relapsing nature of CD and unpredictable flares of activity, is not surprisingly that the burden of IBD is higher for the CD patients, regardless of their disease activity when compared with UC and CelD patients. Although CelD involves life-long GFD diet, symptoms from small-quantities, accidental gluten ingestions, may be mild and overlooked by patients. Furthermore, the development of gluten-free products industry has made these products extremely accessible with a considerable variability, making CelD more “manageable”. These so-called advantages of GFD upon a specific CD diet are responsible for the reduced impact on social aspects associated with food and eating in CelD patients like meeting with peers, overnight staying and preparing a meal.

Extension of this research hopefully will improve our understanding of the impact of food and eating behaviors on the patients’ well-being which can lead to a more tailored dietary approach and better communication with the patient in order to improve the compliance to such restrictive diets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M., C.B. and A.-M.D.; methodology R.M., C.B. and A.-M.D.; software, R.M.; validation, R.M., C.B., A.-M.D.; formal analysis, R.M.; investigation, R.M.,A.-M.D. and C.B.; resources, A.M.I. and D.P.; data curation, A.M.I. and D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-M.D., A.M.I. and D.P.; writing—review and editing, R.M., C.B.; visualization, R.M., C.B. and A.-M.D.; supervision, R.M., C.B. and A.-M.D.; project administration, R.M. and C.B.; funding acquisition, R.M. and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of “Grigore Alexandrescu” Emergency Hospital for Children, Bucharest, Romania, with the approval number 43 from 31 October 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, thorugh the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vuyyuru, S.K.; Kedia, S.; Sahu, P.; Ahuja, V. Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract: Beyond Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. JGH Open 2022, 6, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, Y. Celiac disease in children: A review of the literature. World J Clin Pediatr 2021, 10, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caio, G.; Volta, U.; Sapone, A.; Leffler, D.A.; De Giorgio, R.; Catassi, C.; Fasano, A. Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC Med 2019, 17, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.; Kurppa, K.; Mearin, M.L.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; Christensen, R.; Dolinsek, J.; Gillett, P.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Koltai, T.; Maki, M.; Nielsen, S.M.; Popp, A.; Størdal, K.; Werkstetter, K.; Wessels, M.; European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Guidelines for Diagnosing Coeliac Disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2020, 70, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahmoud, E.; Alkazemi, D.U.Z.; Al-Qabandi, W. Growth Stunting and Nutritional Deficiencies among Children and Adolescents with Celiac Disease in Kuwait: A Case–Control Study. Children 2024, 11, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mędza, A.; Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz, A. Nutritional Status and Metabolism in Celiac Disease: Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, C.; Wolf, R.L.; Leichter, H.J.; Lee, A.R.; Reilly, N.R.; Zybert, P.; Green, P.H.R.; Lebwohl, B. Impact of a Child’s Celiac Disease Diagnosis and Management on the Family. Dig Dis Sci 2020, 65, 2959–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto-Sanchez, M.I.; Blom, J.J.; Gibson, P.R.; Armstrong, D. Nutrition Assessment and Management in Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology 2024, 167, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.J.; Dhawan, A.; Saeed, S.A. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children and Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr 2015, 169, 1053–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, D.; Wang, C.; Huang, Y.; Mao, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Changing epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. Int J Colorectal Dis 2024, 39, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.; Koletzko, S.; Turner, D.; Escher, J.C.; Cucchiara, S.; de Ridder, L.; Kolho, K.L.; Veres, G.; Russell, R.K.; Paerregaard, A.; Buderus, S.; Greer, M.L.; Dias, J.A.; Veereman-Wauters, G.; Lionetti, P.; Sladek, M.; Martin de Carpi, J.; Staiano, A.; Ruemmele, F.M.; Wilson, D.C.; European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014, 58, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerasimidis, K.; Godny, L.; Sigall-Boneh, R.; Svolos, V.; Wall, C.; Halmos, E. Current recommendations on the role of diet in the aetiology and management of IBD. Frontline Gastroenterol 2021, 13, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, S.L.; Day, A.S.; Bryant, R.V.; Halmos, E.P. Revolution in diet therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. JGH Open 2024, 8, 13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishige, T. Growth failure in pediatric onset inflammatory bowel disease: mechanisms, epidemiology, and management. Transl Pediatr 2019, 8, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashash, J.G.; Elkins, J.; Lewis, J.D.; Binion, D.G. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diet and Nutritional Therapies in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czuber-Dochan, W.; Morgan, M.; Hughes, L.D.; Lomer, M.C.; Lindsay, J.O.; Whelan, K. Perceptions and psychosocial impact of food, nutrition, eating and drinking in people with inflammatory bowel disease: A qualitative investigation of food-related quality of life. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet 2019, 33, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, L.D.; King, L.; Morgan, M.; Ayis, S.; Direkze, N.; Lomer, M.C.; Lindsay, J.O.; Whelan, K. Food-related Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Development and Validation of a Questionnaire. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2015, 10, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagnoli, L.; Mutlu, E.A.; Doerfler, B.; Ibrahim, A.; Brenner, D.; Taft, T.H. Food-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res 2019, 28, 2195–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, R.K.; Winkler, L.M.; Zwinderman, K.H.; Mearin, M.L.; Koopman, H.M. CDDUX: a disease-specific health-related quality-of-life questionnaire for children with celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2008, 47, 147–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.; Griffiths, A.; Markowitz, J.; Wilson, D.C.; Turner, D.; Russell, R.K.; Fell, J.; Ruemmele, F.M.; Walters, T.; Sherlock, M.; Dubinsky, M.; Hyams, J.S. Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011, 17, 1314–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.D.; King, L.; Morgan, M.; et al. Food-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: development and validation of a questionnaire. J Crohn’s Colitis 2016, 10, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/measurement-of-growth-in-children?source=history_widget#H3606347, accessed on the 11th of November 2024.

- https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/Pediatric%20Assessment%20Tools%20-%20Feb.%202023.pdf, accessed on the 11th of November 2024.

- Turner, D.; Griffiths, A.M.; Walters, T.D.; Seah, T.; Markowitz, J.; Pfefferkorn, M.; Keljo, D.; Waxman, J.; Otley, A.; LeLeiko, N.S.; Mack, D.; Hyams, J.; Levine, A. Mathematical weighting of the pediatric Crohn’s disease activity index (PCDAI) and comparison with its other short versions. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012, 18, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Otley, A.R.; Mack, D.; Hyams, J.; de Bruijne, J.; Uusoue, K.; Walters, T.D.; Zachos, M.; Mamula, P.; Beaton, D.E.; Steinhart, A.H.; Griffiths, A.M. Development, validation, and evaluation of a pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index: a prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 423–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, L.; Catarino, M.; Festas, C.; Alves, P. Vulnerability in Children with Celiac Disease: Findings from a Scoping Review. Children 2024, 11, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C.D.; Berry, N.; Vaiphei, K.; Dhaka, N.; Sinha, S.K.; Kochhar, R. Quality of life in celiac disease and the effect of gluten-free diet. JGH Open 2018, 2, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcomer, A.L.; de Lima, B.R.; Farage, P.; Fabris, S.; Ritter, R.; Raposo, A.; Teixeira-Lemos, E.; Chaves, C.; Zandonadi, R.P. Enhancing life with celiac disease: unveiling effective tools for assessing health-related quality of life. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1396589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S. Promoting Effective Self-Management of the Gluten-Free Diet: Children’s and Adolescents’ Self-Generated Do’s and Don’ts. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 14051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, M.K. Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Special Considerations. Surg Clin North Am 2019, 99, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, M.W.; Kuenzig, M.E.; Mack, D.R.; et al. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: children and adolescents with IBD. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2019, 2 (Suppl. 1), S49–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowlin, S.; Manning, L.; Keefer, L.; Gorbenko, K. Perceptive eating as part of the journey in inflammatory bowel disease: Lessons learned from lived experience. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2021, 41, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, K.I.; Promislow, S.; Carr, R.; Rawsthorne, P.; Walker, J.R.; Bernstein, C.N. Information needs and preferences of recently diagnosed patients with in- flammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011, 17, 590e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, J.H.M.; Dijkhuizen, M.; Tap, P.; Witteman, B.J.M. Patient’s Dietary Beliefs and Behaviours in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis 2019, 37, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabino, J.; Lewis, J.D.; Colombel, J.F. Treating Inflammatory Bowel Disease With Diet: A Taste Test. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, T.; Tu, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, M.; Huang, L.; Zhang, S.; Xu, G. Risk of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: predictive value of disease phenotype, disease activity and food literacy. J Eat Disord 2023, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limdi, J.K.; Aggarwal, D.; McLaughlin, J.T. Dietary Practices and Beliefs in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2016, 22, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khemiri, W.; Ayari, M.; Ghannouchi, A.; Mtir, M.; Abdelaali, Z.E.I.; Douggui, M.H.; Taieb, J. P980 Dietary perceptions and practices in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2024, 18, i1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederen, K.; Krom, H.; Koole, J.C.D.; Benninga, M.A.; Kindermann, A. Diet and Anthropometrics of Children With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comparison With the General Population. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018, 24, 1632–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, L.; Coo, H.; Jane, A.; Flemming, J.A.; Acker, A.; Hoggan, B.; Griffiths, R.; Sehgal, A.; Mulder, D. Celiac Disease and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Are Associated With Increased Risk of Eating Disorders: An Ontario Health Administrative Database Study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2024, 15, e00700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, K.; Byham-Gray, L.; Rothpletz-Puglia, P. Characterizing the Parental Perspective of Food-Related Quality of Life in Families After Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Diagnosis. Gastroenterology Nursing 2021, 44, E69–E77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.C.; Whelan, K.; Frampton, C.; Wall, C.L.; Gearry, R.B.; Day, A.S. Food-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents With Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2022, 28, 1838–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.D.; Li, J.; Hou, S. Factors influencing food-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Godoy-Brewer, G.; Rodriguez, A.; Graff, E.; Quintero, M.A.; Leavitt, J.; Lopez, J.; Goldberg, D.S.; Damas, O.M.; Whelan, K.; Abreu, M.T. Food-Related Quality of Life Is Impaired in Latinx and Non-Latinx Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastro Hep Adv 2024, 3, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.thebrainyinsights.com/report/gluten-free-products-market-13892, accessed on the 11th of November 2024.

- Iorfida, D.; Valitutti, F.; Vestri, A.; Di Rocco, A.; Cucchiara, S.; Lubrano, R.; Montuori, M. Dietary Compliance and Quality of Life in Celiac Disease: A Long-Term Follow-Up of Primary School Screening-Detected Patients. Front Pediatr 2021, 9, 787938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S.; Monachesi, C.; Barchetti, M.; Lionetti, E.; Catassi, C. Cross-Cultural Participation in Food-Related Activities and Quality of Life among Children with Celiac Disease. Children 2023, 10, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhout, C.; Berbra, O.; Favre, J.; Collins, C.; Calafiore, M.; Peremans, L.; Van Royen, P. Defining and evaluating the Hawthorne effect in primary care, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med 2022, 9, 1033486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).