Submitted:

12 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The city of Macapá in the Brazilian Amazon faces critical aquatic pollution challenges due to inadequate sanitation infrastructure, leading to heavy metal contamination in fish within its urban water bodies. This study evaluates concentrations of metals (Cu, Cd, Cr, Fe, Mn, Ni, Pb, Zn, Hg) in muscle tissues of fish from igarapés, floodplain lakes, and canals. Samples were collected from six sites to investigate the bioaccumulation of these metals and their potential human health risks. Using Atomic Absorption Spectrometry and Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry for Hg, metal levels were analyzed in three carnivorous and seven omnivorous fish species. Cd concentrations in several species exceeded safety thresholds for human consumption, while the estimated daily intake (EDI) of Hg also surpassed reference doses. Risk assessment combining the risk quotient (RQ) for individual metals and the risk index (RI) for metal mixtures indicated considerable health risks associated with consuming fish from these contaminated waters. These findings reveal concerning exposure to contaminants, underscoring the need for environmental management and ongoing monitoring to protect public health in vulnerable urban areas.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

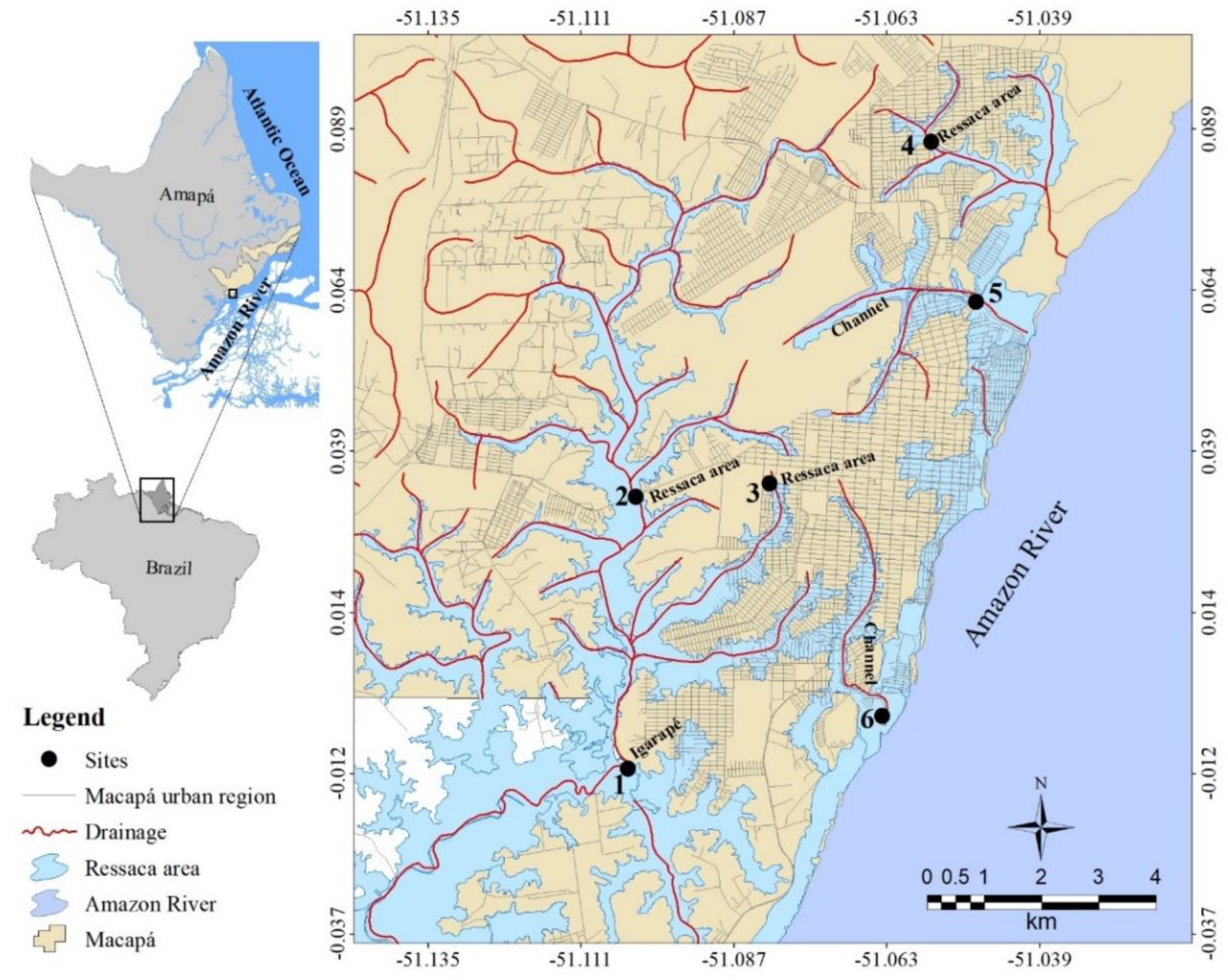

2.1. Sampling Sites

2.2. Fish Sampling

2.3. Preparation of Fish Muscle Samples and Determination of Metals

2.4. Risk Assessment for Human Health from Fish Consumption and Estimation of Daily Intake (EDI)

3. Results

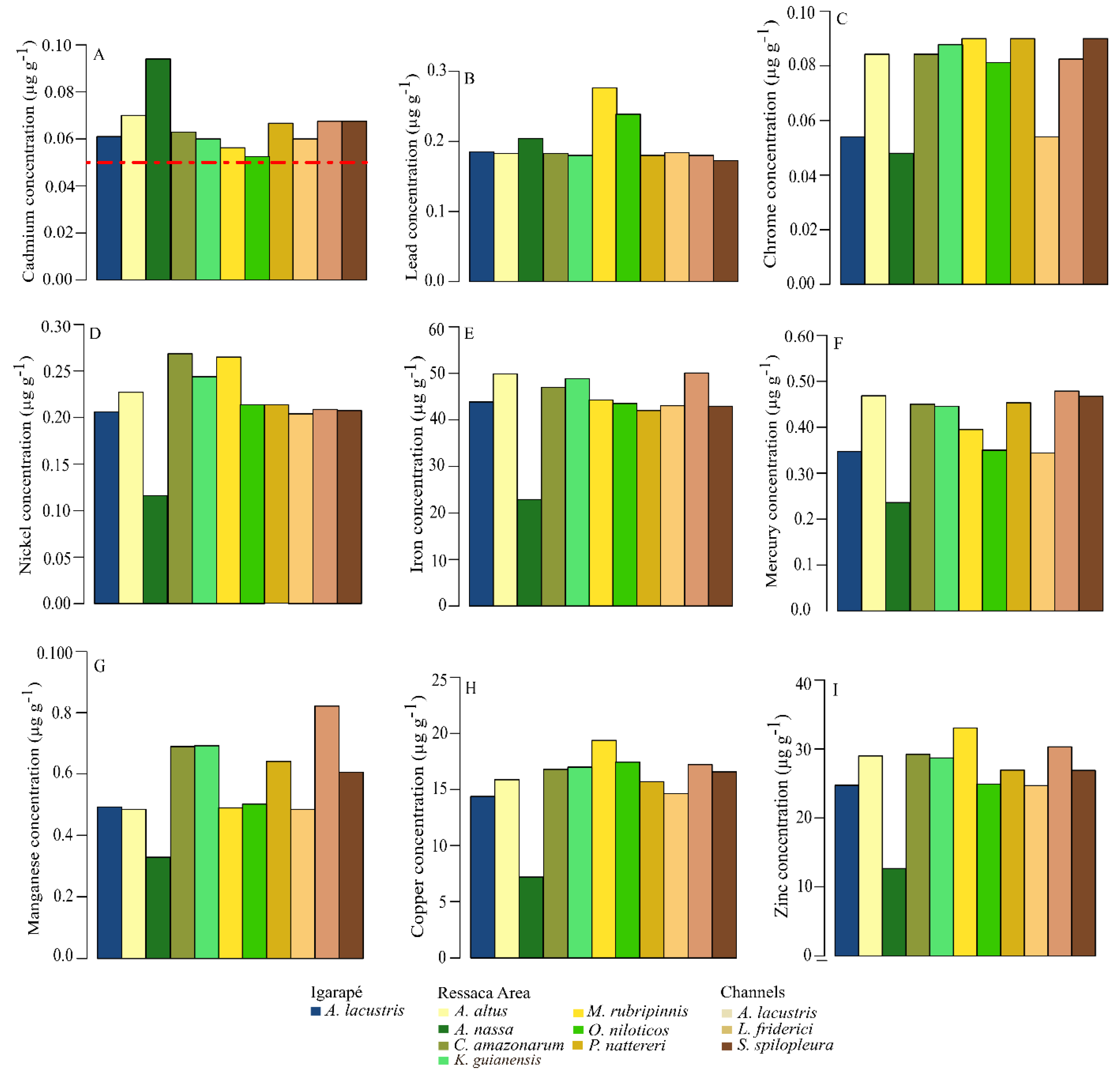

3.1. Metal Concentrations in Fish Species and Their Compliance with Legal Limits

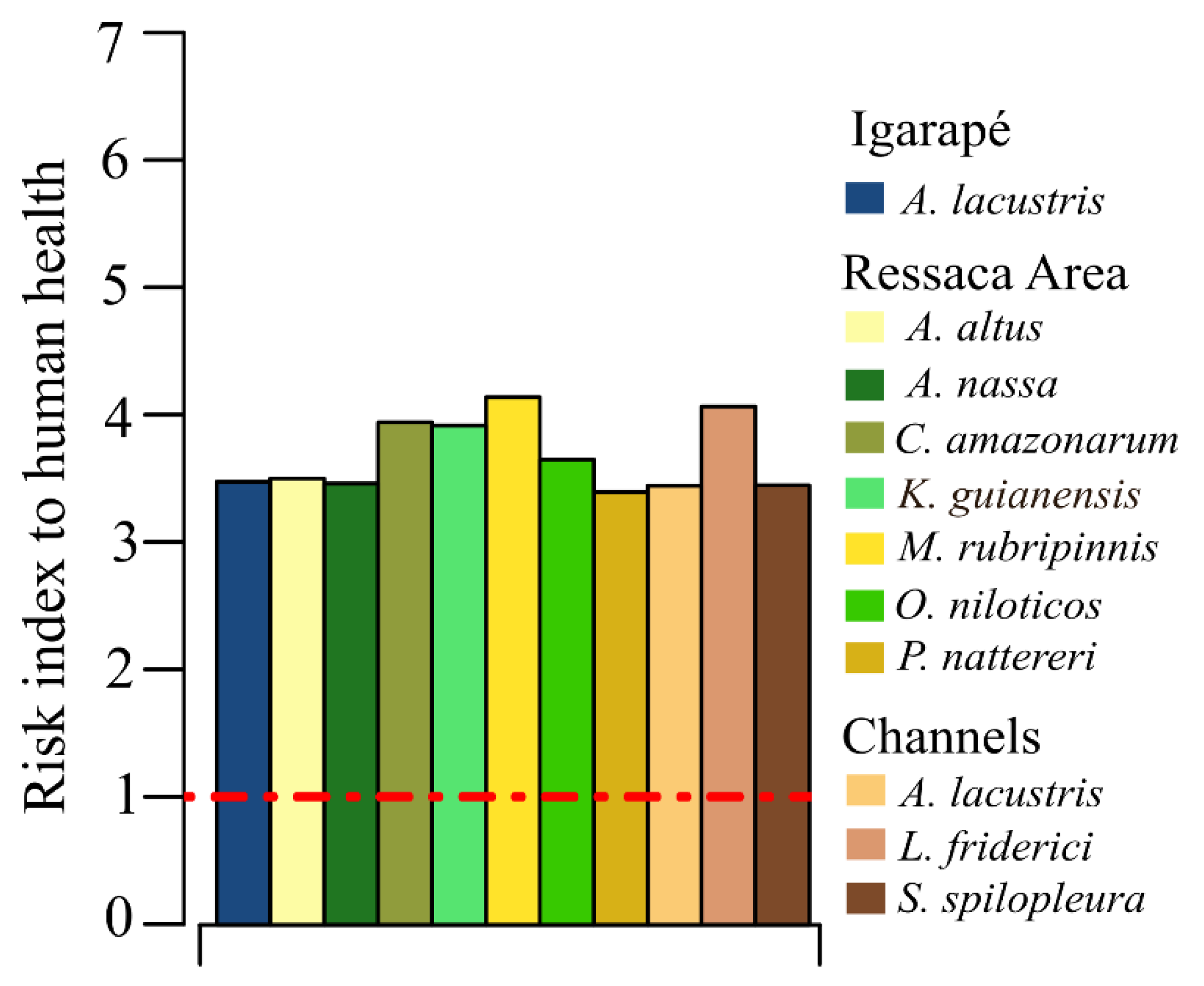

3.3. Human Health Risk Assessment from Fish Consumption

3.4. Estimation of Daily Intake (EDI)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IBGE: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, Population Estimates, Macapá. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/ap/macapa.html (accessed on day month year).

- Santos, C.M.B.; Nery, C.H.S. Análise do atual sistema de esgotamento sanitário da cidade de Macapá em conjuntura com realização de estudo de caso do sistema de esgoto encontrado no bairro central. Rev. Mult. CEAP 2022, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, C.C.S.; Santos, L.G.G.V.; Santos, E.; Damasceno, F.C.; Corrêa, J.A.M. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments of the Amazon River Estuary (Amapá, Northern Brazil): Distribution, Sources and Potential Ecological Risk. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 135, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, T.S.; Viegas, C.J.T.; Cunha, H.F.A.; Cunha, A.C.D. Drainage and Preliminary Risk of Flooding in an Urban Zone of Eastern Amazon. GEP 2023, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.C.; Samora, P. Formas Urbanas Para Áreas de Conflito Socioambiental Em APP’s: Modelos Para Os Desafios Das Áreas de Ressaca de Macapá-AP. Rev Morfologia Urbana 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takiyama, L.R.; Silva, U.R.L.; Jimenez, E.A.; Pereira, R.A. Zoneamento ecológico-econômico urbano das áreas úmidas de Macapá e Santana, Estado do Amapá. Amapá, OLAM - Ciência & Tecnologia 2013, 1, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, C.A.R.; Cunha, A.C.; Cunha, H.F.A. Modelagem de lixiviados e compostos gerados em sistema de bdrenagem de aterro controlado de Macapá/Brasil. Revista Ibero-americana de Ciências Ambientais 2022, 12, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bega, J.M.M.; Zanetoni Filho, J.A.; Albertin, L.L.; Oliveira, J.N.D. Temporal Changes in the Water Quality of Urban Tropical Streams: An Approach to Daily Variation in Seasonality. Integr Envir Assess & Manag 2022, 18, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carim, M.D.J.V.; Torres, A.M.; Takyiama, L.R.; Silva Junior, O.M.D.; Souza, M.O.D.; Souto, F.A.F.; Baia, M.; Barata, J.B.; Souza, A.J.B.D.; Correa, P.R.D.S. Impactos Da Disposição de Resíduos Sólidos Urbanos No Solo e Água Nos Municípios de Macapá e Santana – Amapá. RSD 2022, 11, e37111528211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, F.E.A.; Herrero-Latorre, C.; Miranda, M.; Barrêto Júnior, R.A.; Oliveira, F.L.C.; Sucupira, M.C.A.; Ortolani, E.L.; Minervino, A.H.H.; López-Alonso, M. Fish Tissues for Biomonitoring Toxic and Essential Trace Elements in the Lower Amazon. Environmental Pollution 2021, 283, 117024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.D.S.; Fontes, M.P.F.; Pacheco, A.A.; Lima, H.N.; Santos, J.Z.L. Risk Assessment of Trace Elements Pollution of Manaus Urban Rivers. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 709, 134471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Dai, S.; Yin, Z.; Lu, H.; Jia, R.; Xu, J.; Song, X.; Li, L.; Shu, Y.; Zhao, X. Toxicological Assessment of Combined Lead and Cadmium: Acute and Sub-Chronic Toxicity Study in Rats. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2014, 65, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, L.F.; Súarez, Y.R.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Crispim, B.D.A.; Grisolia, A.B.; Lima-Junior, S.E. Mutagenic and Genotoxic Effects and Metal Contaminations in Fish of the Amambai River, Upper Paraná River, Brazil. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2017, 24, 27104–27112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E. Bioaccumulation of Non-Essential Hazardous Heavy Metals and Metalloids in Freshwater Fish. Risk to Human Health. Environ Chem Lett 2018, 16, 903–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagosta, F.C.P.; Pinna, M.D. The Fishes of the Amazon: Distribution and Biogeographical Patterns, with a Comprehensive List of Species. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, F.E.A.; Minervino, A.H.H.; Miranda, M.; Herrero-Latorre, C.; Barrêto Júnior, R.A.; Oliveira, F.L.C.; Sucupira, M.C.A.; Ortolani, E.L.; López-Alonso, M. Toxic and Essential Trace Element Concentrations in Fish Species in the Lower Amazon, Brazil. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 732, 138983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, S.L.M.; Almeida, O.T.D.; Torres, P.C.; De Moraes, A.; Chacón-Montalván, E.; Parry, L. Urban Amazonians Use Fishing as a Strategy for Coping with Food Insecurity. The Journal of Development Studies 2022, 58, 2544–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacon, S.D.S.; Oliveira-da-Costa, M.; Gama, C.D.S.; Ferreira, R.; Basta, P.C.; Schramm, A.; Yokota, D. Mercury Exposure through Fish Consumption in Traditional Communities in the Brazilian Northern Amazon. IJERPH 2020, 17, 5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L.F.; Kummrow, F.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; De Lima, N.A.; Solórzano, J.C.J.; Crispim, B.D.A.; Barufatti, A.; Florentino, A.C. High Concentrations of Metals in the Waters from Araguari River Lower Section (Amazon Biome): Relationship with Land Use and Cover, Ecotoxicological Effects and Risks to Aquatic Biota. Chemosphere 2021, 285, 131451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.S.; Viana, L.F.; Lima Cardoso, C.A.; Gonar Silva Isacksson, E.D.; Silva, J.C.; Florentino, A.C. Landscape Composition and Inorganic Contaminants in Water and Muscle Tissue of Plagioscion Squamosissimus in the Araguari River (Amazon, Brazil). Environmental Research 2022, 208, 112691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L.F.; Kummrow, F.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; De Lima, N.A.; Do Amaral Crispim, B.; Barufatti, A.; Florentino, A.C. Metal Bioaccumulation in Fish from the Araguari River (Amazon Biome) and Human Health Risks from Fish Consumption. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 4111–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L.F.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Oliveira, M.S.B.; Lima-Junior, S.E.; Kummrow, F.; Florentino, A.C. Metals Bioaccumulation in Fish Captured from Araguari River Upper Section (Amazon Biome), and Risk Assessment to Human Health Resulting from Their Consumption. Journal of Trace Elements and Minerals 2024, 7, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martoredjo, I.; Calvão Santos, L.B.; Vilhena, J.C.E.; Rodrigues, A.B.L.; De Almeida, A.; Sousa Passos, C.J.; Florentino, A.C. Trends in Mercury Contamination Distribution among Human and Animal Populations in the Amazon Region. Toxics 2024, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Rodrigues, C.C.; Santos, L.G.G.V.; Santos, E.; Damasceno, F.C.; Corrêa, J.A.M. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments of the Amazon River Estuary (Amapá, Northern Brazil): Distribution, Sources and Potential Ecological Risk. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 135, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.M.; Juras, A.A.; Mérona, B.; Jégue, M. Peixes do baixo rio Tocantins. 20 anos depois da Usina Hidrelétrica Tucuruí. Eletronorte. Brasília, 2004.

- Sleen, P.V.; Albert, J.S. Field guide to the fishes of the Amazon, Orinoco, and Guianas; Princeton University Press: New Jersey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Viana, L.F.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Lima-Junior, S.E.; Súarez, Y.R.; Florentino, A.C. Bioaccumulation of Metal in Liver Tissue of Fish in Response to Water Toxicity of the Araguari-Amazon River, Brazil. Environ Monit Assess 2020, 192, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, P.; Pla, A.; Hernández, A.F.; Barbier, F.; Ayouni, L.; Gil, F. Determination of Toxic Elements (Mercury, Cadmium, Lead, Tin and Arsenic) in Fish and Shellfish Samples. Risk Assessment for the Consumers. Environment International 2013, 59, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgano, M.A.; Gomes, P.C.; Mantovani, D.M.B.; Perrone, A.A.M.; Santos, T.F. Níveis de Mercúrio Total Em Peixes de Água Doce de Pisciculturas Paulistas. Ciênc. Tecnol. Aliment 2005, 25, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANVISA: Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária do Brasil, Portaria nº 685 de 27 de agosto de 1998, Brasília. https://www.univates.br/unianalises/media/imagens/Anexo_XI_61948_11.pdf. (accessed on day month year).

- ANVISA: Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária do Brasil, Legislação brasileira, resolução nº 42 de 29 de agosto de 2013, Brasília. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2013/rdc0042_29_08_2013.html. (accessed on day month year).

- Ullah, A.K.M.A.; Maksud, M.A.; Khan, S.R.; Lutfa, L.N.; Quraishi, S.B. Development and Validation of a GF-AAS Method and Its Application for the Trace Level Determination of Pb, Cd, and Cr in Fish Feed Samples Commonly Used in the Hatcheries of Bangladesh. J Anal Sci Technol 2017, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Risk based Concentration Table; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Philadelphia, PA; Washington DC, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Duffus, J.H.; Duffus, J.H.; Nordberg, M.; Templeton, D.M. Glossary of Terms Used in Toxicology, 2nd Edition (IUPAC Recommendations 2007). Pure and Applied Chemistry 2007, 79, 1153–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, V.J.; Almeida, M.C.; Giarrizzo, T.; Deus, C.P.; Vale, R.; Klein, G.; Begossi, A. Food Consumption as an Indicator of the Conservation of Natural Resources in Riverine Communities of the Brazilian Amazon. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2015, 87, 2229–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Araujo, J.D.; Hussey, N.E.; Hauser-Davis, R.A.; Rosa, A.H.; Lima, M.D.O.; Giarrizzo, T. Human Risk Assessment of Toxic Elements (As, Cd, Hg, Pb) in Marine Fish from the Amazon. Chemosphere 2022, 301, 134575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANVISA: Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária do Brasil, Nota Técnica nº 8/2019/SEI/GEARE/GGALI/DIRE2/ ANVISA. Processo nº 25351.918291/2019–53, Avaliação de Risco: Consumo de pescado proveniente de regiões afetadas pelo rompimento da Barragem do Fundão/MG. Available online: https://sanityconsultoria.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/nota-tecnica-anvisa-pescado-rio-doce-junho-2019.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- FAO/WHO. Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants. Seventy-third report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Musarrat, M.; Ullah, A.K.M.A.; Moushumi, N.S.; Akon, S.; Nahar, Q.; Saliheen Sultana, S.S.; Quraishi, S.B. Assessment of Heavy Metal(Loid)s in Selected Small Indigenous Species of Industrial Area Origin Freshwater Fish and Potential Human Health Risk Implications in Bangladesh. LWT 2021, 150, 112041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naka, K.S.; De Cássia Dos Santos Mendes, L.; De Queiroz, T.K.L.; Costa, B.N.S.; De Jesus, I.M.; De Magalhães Câmara, V.; De Oliveira Lima, M. A Comparative Study of Cadmium Levels in Blood from Exposed Populations in an Industrial Area of the Amazon, Brazil. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 698, 134309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico, A.; De Oliveira, R.; De Souza Nunes, G.S.; Rizzi, C.; Villa, S.; López-Heras, I.; Vighi, M.; Waichman, A.V. Pharmaceuticals and Other Urban Contaminants Threaten Amazonian Freshwater Ecosystems. Environment International 2021, 155, 106702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Ahmed, M.K.; Habibullah-Al-Mamun, M.; Masunaga, S. Assessment of Trace Metals in Fish Species of Urban Rivers in Bangladesh and Health Implications. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2015, 39, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizwan, K.M.; Thirukumaran, V.; Suresh, M. Assessment and Source Identification of Heavy Metal Contamination of Groundwater Using Geospatial Technology in Gadilam River Basin, Tamil Nadu, India. Appl Water Sci 2021, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanakumar, S.; Solaraj, G.; Mohanraj, R. Heavy Metal Partitioning in Sediments and Bioaccumulation in Commercial Fish Species of Three Major Reservoirs of River Cauvery Delta Region, India. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2015, 113, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Reynolds, M. Cadmium Exposure in Living Organisms: A Short Review. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 678, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, P.; Zhao, F.-J. Dietary Cadmium Exposure, Risks to Human Health and Mitigation Strategies. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2023, 53, 939–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, C.D.; Liu, J.; Diwan, B.A. Metallothionein Protection of Cadmium Toxicity. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2009, 238, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, D.; Słowik, J.; Chilicka, K. Heavy Metals and Human Health: Possible Exposure Pathways and the Competition for Protein Binding Sites. Molecules 2021, 26, 6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Dai, S.; Yin, Z.; Lu, H.; Jia, R.; Xu, J.; Song, X.; Li, L.; Shu, Y.; Zhao, X. Toxicological Assessment of Combined Lead and Cadmium: Acute and Sub-Chronic Toxicity Study in Rats. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2014, 65, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anyanwu, B.; Ezejiofor, A.; Igweze, Z.; Orisakwe, O. Heavy Metal Mixture Exposure and Effects in Developing Nations: An Update. Toxics 2018, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewe, S.; Muischnek, H. Über Kombinationswirkungen: Mitteilung: Hilfsmittel der Fragestellung. Archiv f. experiment. Pathol. u. Pharmakol 1926, 114, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, O.; Scholze, M.; Ermler, S.; McPhie, J.; Bopp, S.K.; Kienzler, A.; Parissis, N.; Kortenkamp, A. Ten Years of Research on Synergisms and Antagonisms in Chemical Mixtures: A Systematic Review and Quantitative Reappraisal of Mixture Studies. Environment International 2021, 146, 106206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurnjak Bureš, M.; Cvetnić, M.; Miloloža, M.; Kučić Grgić, D.; Markić, M.; Kušić, H.; Bolanča, T.; Rogošić, M.; Ukić, Š. Modeling the Toxicity of Pollutants Mixtures for Risk Assessment: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 2021, 19, 1629–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Da Silva, S.; De Oliveira Lima, M. Mercury in Fish Marketed in the Amazon Triple Frontier and Health Risk Assessment. Chemosphere 2020, 248, 125989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Levy, I.E.; Van Damme, P.A.; Carvajal-Vallejos, F.M.; Bervoets, L. Trace Element Accumulation in Different Edible Fish Species from the Bolivian Amazon and the Risk for Human Consumption. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L.F.; Súarez, Y.R.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Crispim, B.D.A.; Grisolia, A.B.; Lima-Junior, S.E. Mutagenic and Genotoxic Effects and Metal Contaminations in Fish of the Amambai River, Upper Paraná River, Brazil. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2017, 24, 27104–27112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fish species | Igarapé | Ressaca areas | Channels | Standard length (cm) | Total weight (g) | Feeding habits | Habitats | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 | Site 6 | |||||

| A. altus | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.02±0.72 | 18.18±3.41 | Carnivore | Benthopelagic |

| P. nattereri | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.84±1.66 | 37.56±20.76 | Carnivore | Pelagic |

| S. spilopleura | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7.25±0.31 | 12.80±2.20 | Carnivore | Benthopelagic |

| A. lacustris | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 8.50±0.85 | 20.01±6.75 | Omnivore | Benthopelagic |

| A. nassa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4.50±1.13 | 6.00±4.24 | Omnivore | Benthopelagic |

| C. amazonarum | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.10±0.88 | 61.62±27.58 | Omnivore | Benthopelagic |

| K. guianensis | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.16±0.99 | 63.80±40.54 | Omnivore | Benthopelagic |

| L. friderici | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9.02±2.67 | 23.87±14.82 | Omnivore | Benthopelagic |

| M. rubripinnis | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.55±1.66 | 42.21±15.40 | Omnivore | Benthopelagic |

| O. niloticus | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23.28±2.46 | 512.57±166.44 | Omnivore | Benthopelagic |

| Total | 17 | 20 | 34 | 3 | 5 | 14 | ||||

| Risk assessment to human health | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish species | Sites | Cd | Pb | Cr | Ni | Hg | Cu | Zn |

| A. lacustris | Igarapé | 1.22 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.04 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.49 |

| A. altus | Ressaca areas | 1.37 | 0.60 | 0.84 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.58 |

| A. nassa | Ressaca areas | 1.88 | 0.68 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| C. amazonarum | Ressaca areas | 1.26 | 0.62 | 0.84 | 0.05 | 0.91 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| K. guianensis | Ressaca areas | 1.25 | 0.60 | 0.88 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.56 | 0.57 |

| M. rubripinnis | Ressaca areas | 1.12 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.66 |

| O. niloticus | Ressaca areas | 1.05 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.50 |

| P. nattereri | Ressaca areas | 1.33 | 0.60 | 0.90 | 0.04 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.54 |

| A. lacustris | Channels | 1.20 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.04 | 0.69 | 0.49 | 0.49 |

| L. friderici | Channels | 1.35 | 0.60 | 0.82 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.57 | 0.60 |

| S. spilopleura | Channels | 1.35 | 0.57 | 0.90 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.54 |

| Fish species | Sites | Element daily intake (EDI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | Pb | Cr | Ni | Fe | Hg | Mn | Cu | Zn | ||

| A. lacustris | Igarapé | 0.42 | 1.28 | 0.37 | 1.43 | 304.34 | 2.41 | 3.41 | 99.75 | 171.59 |

| A. altus | Ressaca areas | 0.47 | 1.26 | 0.58 | 1.58 | 346.72 | 3.25 | 3.36 | 111.07 | 201.17 |

| A. nassa | Ressaca areas | 0.65 | 1.41 | 0.33 | 0.80 | 158.80 | 1.64 | 2.28 | 49.86 | 87.75 |

| C. amazonarum | Ressaca areas | 0.44 | 1.29 | 0.58 | 1.87 | 329.23 | 3.17 | 4.78 | 116.48 | 202.67 |

| K. guianensis | Ressaca areas | 0.43 | 1.25 | 0.61 | 1.70 | 339.20 | 3.09 | 4.80 | 117.90 | 200.12 |

| M. rubripinnis | Ressaca areas | 0.39 | 1.92 | 9.22 | 1.84 | 307.36 | 2.74 | 3.37 | 134.44 | 229.37 |

| O. niloticus | Ressaca areas | 0.36 | 1.65 | 0.56 | 1.48 | 301.30 | 2.48 | 3.48 | 120.93 | 172.91 |

| P. nattereri | Ressaca areas | 0.46 | 1.25 | 0.62 | 1.48 | 291.54 | 3.15 | 4.44 | 108.93 | 186.86 |

| A. lacustris | Channels | 0.41 | 1.27 | 0.37 | 1.41 | 298.72 | 2.39 | 3.36 | 101.47 | 171.37 |

| L. friderici | Channels | 0.47 | 1.25 | 0.57 | 1.45 | 347.55 | 3.32 | 5.70 | 119.45 | 210.41 |

| S. spilopleura | Channels | 0.47 | 1.20 | 0.62 | 1.44 | 297.96 | 3.24 | 4.20 | 114.98 | 186.63 |

| RfD | 0.83a | 1.2b | 45.00a | 1000.00a | 3470.00 a | 0.57a | 2300.00a | 6935.00a | 23,500.00a | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).