Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Defining a Rhodococcus (sensu lato) group

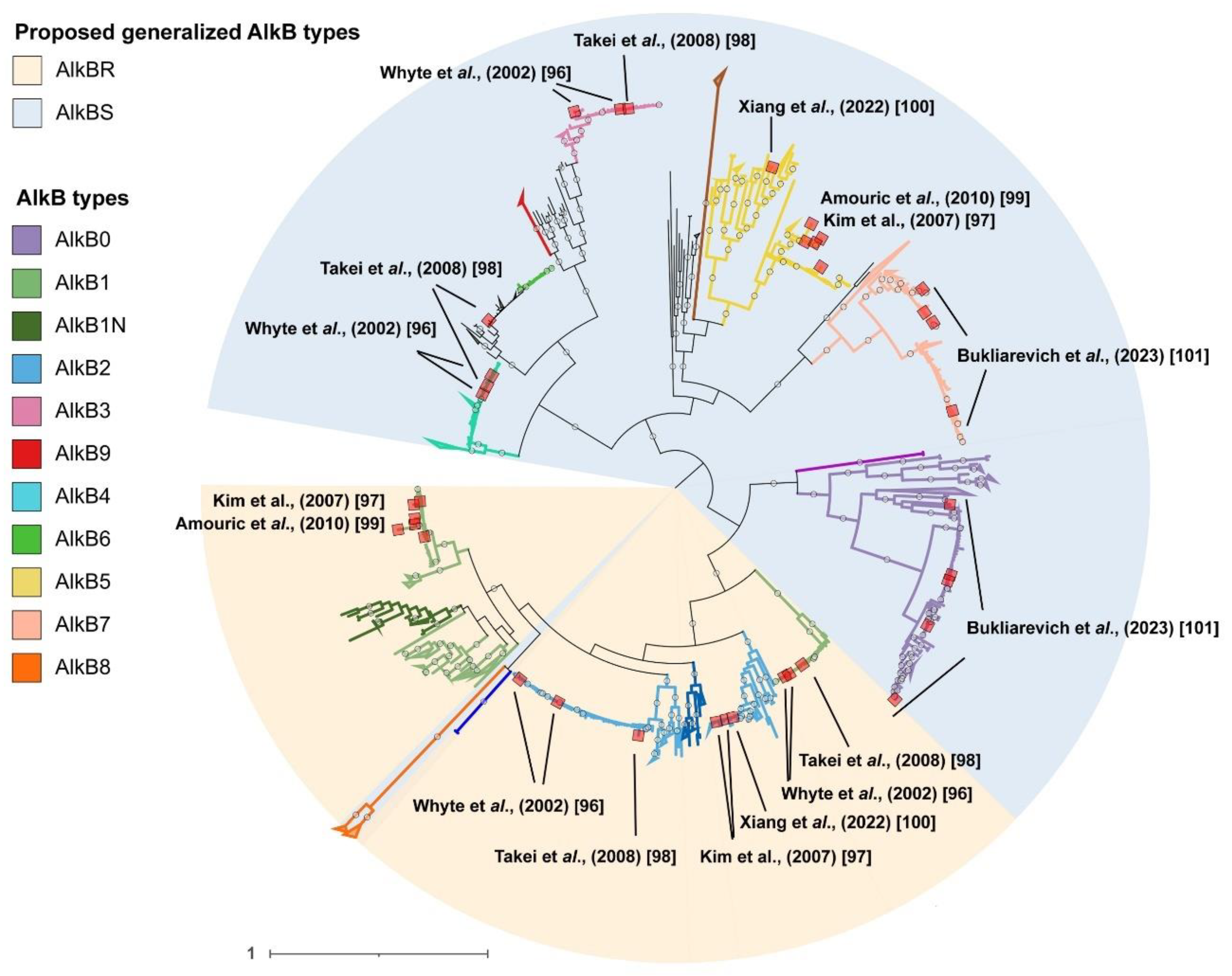

2.2. Phylogenetic analysis of AlkB sequences and examination of the genomic context

2.3. Distribution of AlkB types by species

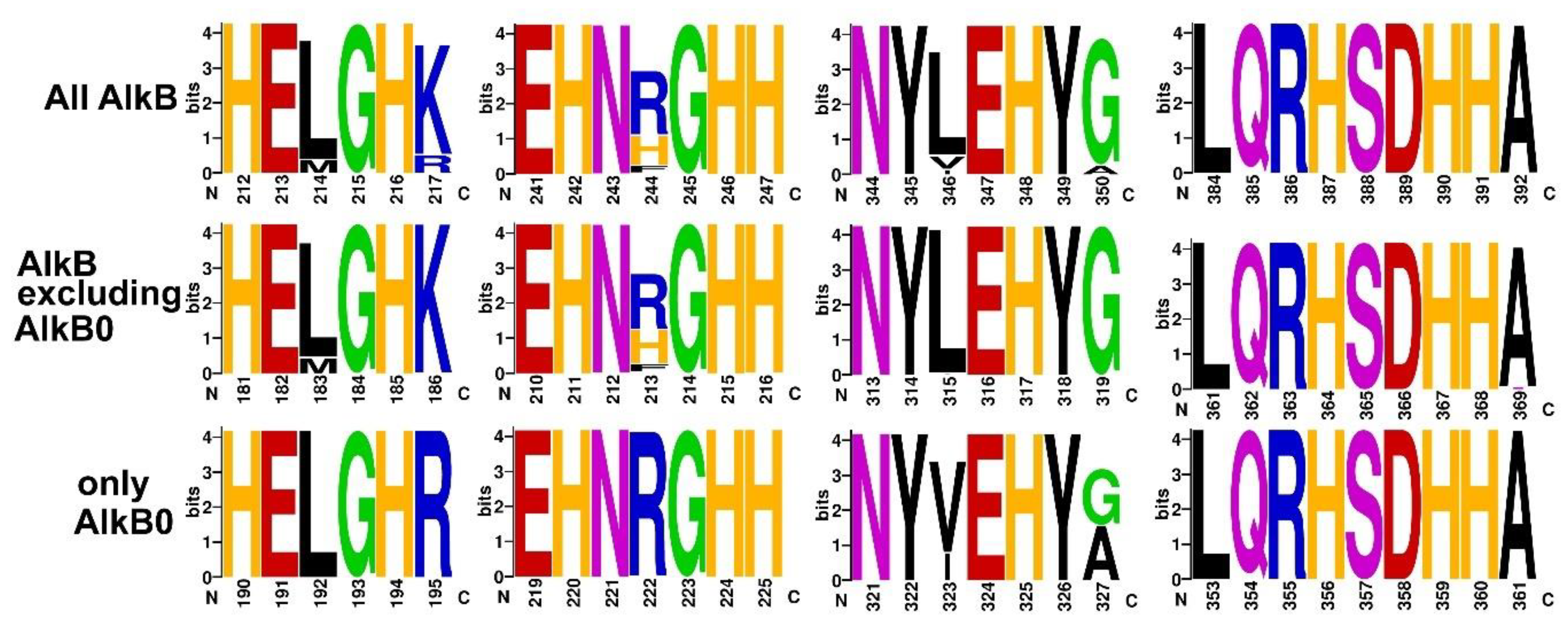

2.4. AlkB amino acid motifs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Phylogenetic analysis of sequences of alkane monooxygenases of the AlkB family

4.2. Assessment of the taxonomy classification

4.3. Characterisation of the genomic context

4.4. Characterisation of amino acid motifs

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muthukumar, B.; Parthipan, P.; AlSalhi, M.S.; Prabhu, N.S.; Rao, T.N.; Devanesan, S.; Maruthamuthu, M.K.; Rajasekar, A. Characterization of Bacterial Community in Oil-Contaminated Soil and Its Biodegradation Efficiency of High Molecular Weight (>C40) Hydrocarbon. Chemosphere 2022, 289, 133168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzeszcz, J.; Steliga, T.; Ryszka, P.; Kaszycki, P.; Kapusta, P. Bacteria Degrading Both N-Alkanes and Aromatic Hydrocarbons Are Prevalent in Soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 31, 5668–5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehiosun, K.I.; Godin, S.; Urios, L.; Lobinski, R.; Grimaud, R. Degradation of Long-Chain Alkanes through Biofilm Formation by Bacteria Isolated from Oil-Polluted Soil. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 2022, 175, 105508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosai, H.B.; Panseriya, H.Z.; Patel, P.G.; Patel, A.C.; Shankar, A.; Varjani, S.; Dave, B.P. Exploring Bacterial Communities through Metagenomics during Bioremediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons from Contaminated Sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 842, 156794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, M.; Smith, A.F.; Rattray, J.E.; England, W.E.; Hubert, C.R.J. Potential for Natural Attenuation of Crude Oil Hydrocarbons in Benthic Microbiomes near Coastal Communities in Kivalliq, Nunavut, Canada. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 196, 115557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goveas, L.C.; Nayak, S.; Selvaraj, R. Concise Review on Bacterial Degradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons: Emphasis on Indian Marine Environment. Bioresour. Technol. Reports 2022, 19, 101136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanram, R.; Jagtap, C.; Kumar, P. Isolation, Screening, and Characterization of Surface-Active Agent-Producing, Oil-Degrading Marine Bacteria of Mumbai Harbor. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, X.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Luo, C.; Zhang, G. Synergism of Endophytic Microbiota and Plants Promotes the Removal of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons from the Alfalfa Rhizosphere. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.L.; Numan, M.; Bilal, S.; Asaf, S.; Crafword, K.; Imran, M.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Al-Sabahi, J.N.; Rehman, N. ur; A-Rawahi, A.; et al. Mangrove’s Rhizospheric Engineering with Bacterial Inoculation Improve Degradation of Diesel Contamination. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, H.; Tang, G.-X.; Huang, Y.-H.; Mo, C.-H.; Zhao, H.-M.; Xiang, L.; Li, Y.-W.; Li, H.; Cai, Q.-Y.; Li, Q.X. Response and Adaptation of Rhizosphere Microbiome to Organic Pollutants with Enriching Pollutant-Degraders and Genes for Bioremediation: A Critical Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góngora, E.; Chen, Y.-J.; Ellis, M.; Okshevsky, M.; Whyte, L. Hydrocarbon Bioremediation on Arctic Shorelines: Historic Perspective and Roadway to the Future. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 119247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, D.K.; Li, C.; Jiang, C.; Chakraborty, A.; Grasby, S.E.; Hubert, C.R.J. Natural Attenuation of Spilled Crude Oil by Cold-Adapted Soil Bacterial Communities at a Decommissioned High Arctic Oil Well Site. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez, S.; Monien, P.; Pepino Minetti, R.; Jürgens, J.; Curtosi, A.; Villalba Primitz, J.; Frickenhaus, S.; Abele, D.; Mac Cormack, W.; Helmke, E. Bacterial Communities and Chemical Parameters in Soils and Coastal Sediments in Response to Diesel Spills at Carlini Station, Antarctica. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 605–606, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dorst, J.; Wilkins, D.; Crane, S.; Montgomery, K.; Zhang, E.; Spedding, T.; Hince, G.; Ferrari, B. Microbial Community Analysis of Biopiles in Antarctica Provides Evidence of Successful Hydrocarbon Biodegradation and Initial Soil Ecosystem Recovery. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 290, 117977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea-Smith, D.J.; Biller, S.J.; Davey, M.P.; Cotton, C.A.R.; Perez Sepulveda, B.M.; Turchyn, A.V.; Scanlan, D.J.; Smith, A.G.; Chisholm, S.W.; Howe, C.J. Contribution of Cyanobacterial Alkane Production to the Ocean Hydrocarbon Cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 13591–13596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, S.; Giebler, J.; Chatzinotas, A.; Wick, L.Y.; Fetzer, I.; Welzl, G.; Harms, H.; Schloter, M. Plant Litter and Soil Type Drive Abundance, Activity and Community Structure of AlkB Harbouring Microbes in Different Soil Compartments. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1763–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, B.; Chen, J.-S.; Hsu, B.-M.; Chao, W.-C.; Fan, C.-W. Niche-Specific Modulation of Long-Chain n-Alkanes Degrading Bacterial Community and Their Functionality in Forest Habitats across the Leaf Litter-Soil Compartments. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 195, 105248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesenberg, G.L.B.; Lehndorff, E.; Schwark, L. Thermal Degradation of Rye and Maize Straw: Lipid Pattern Changes as a Function of Temperature. Org. Geochem. 2009, 40, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatiault, R.; Henry, P.; Loncke, L.; Sadaoui, M.; Sakellariou, D. Natural Oil Seep Systems in the Aegean Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 163, 106754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvenvolden, K.A.; Cooper, C.K. Natural Seepage of Crude Oil into the Marine Environment. Geo-Marine Lett. 2003, 23, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.A. General Characteristics of Petroleum Hydrocarbons Molecular and Group-Type Methods of Analysis and Classification. In Petroleum Hydrocarbons; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1987; pp. 4–26. [Google Scholar]

- Burgherr, P. In-Depth Analysis of Accidental Oil Spills from Tankers in the Context of Global Spill Trends from All Sources. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 140, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou Samra, R.M.; Ali, R.R. Tracking the Behavior of an Accidental Oil Spill and Its Impacts on the Marine Environment in the Eastern Mediterranean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 198, 115887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivshina, I.B.; Kuyukina, M.S.; Krivoruchko, A.V.; Elkin, A.A.; Makarov, S.O.; Cunningham, C.J.; Peshkur, T.A.; Atlas, R.M.; Philp, J.C. Oil Spill Problems and Sustainable Response Strategies through New Technologies. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2015, 17, 1201–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Yulisa, A.; Kim, S.; Hwang, S. Monitoring Microbial Community Structure and Variations in a Full-Scale Petroleum Refinery Wastewater Treatment Plant. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 306, 123178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, F.U.; Ejaz, M.; Cheema, S.A.; Khan, M.I.; Zhao, B.; Liqun, C.; Salim, M.A.; Naveed, M.; Khan, N.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; et al. Phytotoxicity of Petroleum Hydrocarbons: Sources, Impacts and Remediation Strategies. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, M.G.; Vivian, D.N.; Heintz, R.A.; Yim, U.H. Long-Term Ecological Impacts from Oil Spills: Comparison of Exxon Valdez, Hebei Spirit, and Deepwater Horizon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 6456–6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassalle, G.; Scafutto, R.D.M.; Lourenço, R.A.; Mazzafera, P.; de Souza Filho, C.R. Remote Sensing Reveals Unprecedented Sublethal Impacts of a 40-Year-Old Oil Spill on Mangroves. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 331, 121859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroope, S.; Slack, T.; Kroeger, R.A.; Keating, K.S.; Beedasy, J.; Sury, J.J.; Brooks, J.; Chandler, T. Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Exposures and Long-Term Self-Rated Health Effects among Parents in Coastal Louisiana. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2023, 17, e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemati, S.; Heidari, M.; Momenbeik, F.; Khodabakhshi, A.; Fadaei, A.; Farhadkhani, M.; Mohammadi-Moghadam, F. Co-Occurrence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Heavy Metals in Various Environmental Matrices of a Chronic Petroleum Polluted Region in Iran; Pollution Characterization, and Assessment of Ecological and Human Health Risks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, C.C.; Onyema, V.O.; Obi, C.J.; Moneke, A.N. A Systematic Review of the Impacts of Oil Spillage on Residents of Oil-Producing Communities in Nigeria. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 34761–34786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Yang, C.; Su, L.; Sun, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; Hao, Y.; Ma, H.; Chen, H.; et al. Interactions between Plants and Bacterial Communities for Phytoremediation of Petroleum-Contaminated Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 37564–37573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Huang, Q.; Cai, X.; Zhao, X.; Luo, C.; Zhang, G. Metabolic Characterization and Geochemical Drivers of Active Hydrocarbon-Degrading Microorganisms. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2024, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhuang, J.; Dai, T.; Zhang, R.; Zeng, Y.; Jiang, B.; Guo, H.; Guo, X.; Yang, Y. Enhancing Soil Petrochemical Contaminant Remediation through Nutrient Addition and Exogenous Bacterial Introduction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, F. Degradation of Alkanes by Bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 2477–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.C.; Austin, R.N. An Overview of the Electron-Transfer Proteins That Activate Alkane Monooxygenase (AlkB). Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R.; Rojo, F. Enzymes for Aerobic Degradation of Alkanes in Bacteria. In Aerobic Utilization of Hydrocarbons, Oils, and Lipids. Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology; Rojo, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hamamura, N.; Storfa, R.T.; Semprini, L.; Arp, D.J. Diversity in Butane Monooxygenases among Butane-Grown Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 4586–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ren, H.; Kong, X.; Wu, H.; Lu, Z. A Multicomponent Propane Monooxygenase Catalyzes the Initial Degradation of Methyl Tert -Butyl Ether in <i>Mycobacterium Vaccae</i? JOB5. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, E.; Di Benedetto, G.; Firrincieli, A.; Presentato, A.; Frascari, D.; Cappelletti, M. Unravelling the Role of the Group 6 Soluble Di-Iron Monooxygenase (SDIMO) SmoABCD in Alkane Metabolism and Chlorinated Alkane Degradation. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, P.-P.; Ding, X.-M.; Op den Camp, H.J.M.; Quan, Z.-X. Horizontal Gene Transfer of Genes Encoding Copper-Containing Membrane-Bound Monooxygenase (CuMMO) and Soluble Di-Iron Monooxygenase (SDIMO) in Ethane- and Propane-Oxidizing Rhodococcus Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funhoff, E.G.; Bauer, U.; García-Rubio, I.; Witholt, B.; van Beilen, J.B. CYP153A6, a Soluble P450 Oxygenase Catalyzing Terminal-Alkane Hydroxylation. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 5220–5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, S.; Julsing, M.K.; Volmer, J.; Riechert, O.; Schmid, A.; Bühler, B. Whole-Cell-Based CYP153A6-Catalyzed (S)-Limonene Hydroxylation Efficiency Depends on Host Background and Profits from Monoterpene Uptake via AlkL. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013, 110, 1282–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, E.; Park, B.G.; Yoo, H.-W.; Kim, J.; Choi, K.-Y.; Kim, B.-G. Semi-Rational Engineering of CYP153A35 to Enhance ω-Hydroxylation Activity toward Palmitic Acid. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Throne-Holst, M.; Wentzel, A.; Ellingsen, T.E.; Kotlar, H.-K.; Zotchev, S.B. Identification of Novel Genes Involved in Long-Chain n-Alkane Degradation by Acinetobacter Sp. Strain DSM 17874. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 3327–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Han, L.; Lee, J.; Williams, S.C.; Forsberg, A.; Xu, Y.; Austin, R.N.; Feng, L. Structure and Mechanism of the Alkane-Oxidizing Enzyme AlkB. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beilen, J.B.; Panke, S.; Lucchini, S.; Franchini, A.G.; Röthlisberger, M.; Witholt, B. Analysis of Pseudomonas Putida Alkane-Degradation Gene Clusters and Flanking Insertion Sequences: Evolution and Regulation of the Alk Genes. Microbiology 2001, 147, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.C.; Forsberg, A.P.; Lee, J.; Vizcarra, C.L.; Lopatkin, A.J.; Austin, R.N. Investigation of the Prevalence and Catalytic Activity of Rubredoxin-Fused Alkane Monooxygenases (AlkBs). J. Inorg. Biochem. 2021, 219, 111409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.C.; Luongo, D.; Orman, M.; Vizcarra, C.L.; Austin, R.N. An Alkane Monooxygenase (AlkB) Family in Which All Electron Transfer Partners Are Covalently Bound to the Oxygen-Activating Hydroxylase. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2022, 228, 111707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.-W.; Kim, J.; Patil, M.D.; Park, B.G.; Joo, S.; Yun, H.; Kim, B.-G. Production of 12-Hydroxy Dodecanoic Acid Methyl Ester Using a Signal Peptide Sequence-Optimized Transporter AlkL and a Novel Monooxygenase. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 291, 121812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanklin, J.; Achim, C.; Schmidt, H.; Fox, B.G.; Munck, E. Mössbauer Studies of Alkane-Hydroxylase: Evidence for a Diiron Cluster in an Integral-Membrane Enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997, 94, 2981–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, S.-H.; Parvez, S.; Pender-Cudlip, M.; Groves, J.T.; Austin, R.N. Substrate Specificity and Reaction Mechanism of Purified Alkane Hydroxylase from the Hydrocarbonoclastic Bacterium Alcanivorax Borkumensis (<i>Ab<i/>AlkB). J. Inorg. Biochem. 2013, 121, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss-Blanquet, S.; Benoit, Y.; Marechaux, C.; Monot, F. Assessing the Role of Alkane Hydroxylase Genotypes in Environmental Samples by Competitive PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, H.; Wang, Y.; Chang, S.; Liu, G.; Chen, T.; Huo, G.; Zhang, W.; Wu, X.; Tai, X.; Sun, L.; et al. Diversity of Crude Oil-Degrading Bacteria and Alkane Hydroxylase (AlkB) Genes from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Y.; Chi, C.-Q.; Fang, H.; Liang, J.-L.; Lu, S.-L.; Lai, G.-L.; Tang, Y.-Q.; Wu, X.-L. Diverse Alkane Hydroxylase Genes in Microorganisms and Environments. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Peng, Y.; Liao, J.; Liu, X.; Peng, J.; Wang, J.-H.; Shao, Z. Broad-Spectrum Hydrocarbon-Degrading Microbes in the Global Ocean Metagenomes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Révész, F.; Figueroa-Gonzalez, P.A.; Probst, A.J.; Kriszt, B.; Banerjee, S.; Szoboszlay, S.; Maróti, G.; Táncsics, A. Microaerobic Conditions Caused the Overwhelming Dominance of Acinetobacter Spp. and the Marginalization of Rhodococcus Spp. in Diesel Fuel/Crude Oil Mixture-Amended Enrichment Cultures. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guibert, L.M.; Loviso, C.L.; Marcos, M.S.; Commendatore, M.G.; Dionisi, H.M.; Lozada, M. Alkane Biodegradation Genes from Chronically Polluted Subantarctic Coastal Sediments and Their Shifts in Response to Oil Exposure. Microb. Ecol. 2012, 64, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sipilä, T.; Pulkkinen, P.; Yrjälä, K. Secondary Successional Trajectories of Structural and Catabolic Bacterial Communities in Oil-Polluted Soil Planted with Hybrid Poplar. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasmund, K.; Burns, K.A.; Kurtböke, D.I.; Bourne, D.G. Novel Alkane Hydroxylase Gene (AlkB) Diversity in Sediments Associated with Hydrocarbon Seeps in the Timor Sea, Australia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7391–7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagi, A.; Knapik, K.; Baussant, T. Abundance and Diversity of n-Alkane and PAH-Degrading Bacteria and Their Functional Genes – Potential for Use in Detection of Marine Oil Pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 810, 152238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Dubinsky, E.A.; Probst, A.J.; Wang, J.; Sieber, C.M.K.; Tom, L.M.; Gardinali, P.R.; Banfield, J.F.; Atlas, R.M.; Andersen, G.L. Simulation of Deepwater Horizon Oil Plume Reveals Substrate Specialization within a Complex Community of Hydrocarbon Degraders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 7432–7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Deng, Y.; Van Nostrand, J.D.; He, Z.; Voordeckers, J.; Zhou, A.; Lee, Y.-J.; Mason, O.U.; Dubinsky, E.A.; Chavarria, K.L.; et al. Microbial Gene Functions Enriched in the Deepwater Horizon Deep-Sea Oil Plume. ISME J. 2012, 6, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, W.C.; Butler, T.M.; Ghannam, R.B.; Webb, P.N.; Techtmann, S.M. Phylogeny and Diversity of Alkane-Degrading Enzyme Gene Variants in the Laurentian Great Lakes and Western Atlantic. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2020, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.B.; Tolar, B.B.; Hollibaugh, J.T.; King, G.M. Alkane Hydroxylase Gene (AlkB) Phylotype Composition and Diversity in Northern Gulf of Mexico Bacterioplankton. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, S.; Hatt, J.K.; Kim, M.; Spain, J.C.; Huettel, M.; Kostka, J.E.; Konstantinidis, K.T. A Novel, Divergent Alkane Monooxygenase (AlkB Clade) Involved in Crude Oil Biodegradation. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2021, 13, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, K.L.; Zaugg, J.; Mason, O.U. Novel, Active, and Uncultured Hydrocarbon-Degrading Microbes in the Ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Rosas Landa, M.; De Anda, V.; Rohwer, R.R.; Angelova, A.; Waldram, G.; Gutierrez, T.; Baker, B.J. Exploring Novel Alkane-Degradation Pathways in Uncultured Bacteria from the North Atlantic Ocean. mSystems 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Vargas, J.; Castelán-Sánchez, H.G.; Pardo-López, L. HADEG: A Curated Hydrocarbon Aerobic Degradation Enzymes and Genes Database. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2023, 107, 107966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, G.; Liao, Z.; Liu, T.; Ma, T. A Novel Alkane Monooxygenase (AlkB) Clade Revealed by Massive Genomic Survey and Its Dissemination Association with IS Elements. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampolli, J.; Zeaiter, Z.; Di Canito, A.; Di Gennaro, P. Genome Analysis and -Omics Approaches Provide New Insights into the Biodegradation Potential of Rhodococcus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.T.; Simon, V.; Machado, B.S.; Crestani, L.; Marchezi, G.; Concolato, G.; Ferrari, V.; Colla, L.M.; Piccin, J.S. Rhodococcus: A Promising Genus of Actinomycetes for the Bioremediation of Organic and Inorganic Contaminants. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 323, 116220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrova, A.A.; Trofimov, S.Y.; Kinzhaev, R.R.; Avetov, N.A.; Arzamazova, A.V.; Puntus, I.F.; Sazonova, O.I.; Sokolov, S.L.; Streletskii, R.A.; Petrikov, K.V.; et al. Development of Microbial Consortium for Bioremediation of Oil-Contaminated Soils in the Middle Ob Region. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2022, 55, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beilen, J.B.; Smits, T.H.M.; Whyte, L.G.; Schorcht, S.; Röthlisberger, M.; Plaggemeier, T.; Engesser, K.-H.; Witholt, B. Alkane Hydroxylase Homologues in Gram-Positive Strains. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 4, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Shan, G.; Shen, J.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Cui, C. In Situ Bioremediation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon–Contaminated Soil: Isolation and Application of a Rhodococcus Strain. Int. Microbiol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.; Sengupta, K. Computational-Based Insights into the Phylogeny, Structure, and Function of Rhodococcus Alkane-1-Monooxygenase. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Shao, Z. Diversity and Abundance of Oil-Degrading Bacteria and Alkane Hydroxylase (AlkB) Genes in the Subtropical Seawater of Xiamen Island. Microb. Ecol. 2010, 60, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A New Generation of Protein Database Search Programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 3389–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Lee, J.; Eusebi, A.; Niewielska, A.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Lopez, R.; Butcher, S. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher Sequence Analysis Tools Framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W521–W525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast Model Selection for Accurate Phylogenetic Estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (ITOL) v6: Recent Updates to the Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoch, C.L.; Ciufo, S.; Domrachev, M.; Hotton, C.L.; Kannan, S.; Khovanskaya, R.; Leipe, D.; Mcveigh, R.; O’Neill, K.; Robbertse, B.; et al. NCBI Taxonomy: A Comprehensive Update on Curation, Resources and Tools. Database 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, D.H.; Chuvochina, M.; Rinke, C.; Mussig, A.J.; Chaumeil, P.-A.; Hugenholtz, P. GTDB: An Ongoing Census of Bacterial and Archaeal Diversity through a Phylogenetically Consistent, Rank Normalized and Complete Genome-Based Taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D785–D794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS Is an Automated High-Throughput Platform for State-of-the-Art Genome-Based Taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumeil, P.-A.; Mussig, A.J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Parks, D.H. GTDB-Tk v2: Memory Friendly Classification with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 5315–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberto, J. SyntTax: A Web Server Linking Synteny to Prokaryotic Taxonomy. BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, C.L.M.; Booth, T.J.; van Wersch, B.; van Grieken, L.; Medema, M.H.; Chooi, Y.-H. Cblaster: A Remote Search Tool for Rapid Identification and Visualization of Homologous Gene Clusters. Bioinforma. Adv. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, C.L.M.; Chooi, Y.-H. Clinker & Clustermap.Js: Automatic Generation of Gene Cluster Comparison Figures. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2473–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val-Calvo, J.; Vázquez-Boland, J.A. Mycobacteriales Taxonomy Using Network Analysis-Aided, Context-Uniform Phylogenomic Approach for Non-Subjective Genus Demarcation. MBio 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangal, V.; Goodfellow, M.; Jones, A.L.; Schwalbe, E.C.; Blom, J.; Hoskisson, P.A.; Sutcliffe, I.C. Next-Generation Systematics: An Innovative Approach to Resolve the Structure of Complex Prokaryotic Taxa. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.; Cognat, V.; Goodfellow, M.; Koechler, S.; Heintz, D.; Carapito, C.; Van Dorsselaer, A.; Mahmoud, H.; Sangal, V.; Ismail, W. Phylogenomic Classification and Biosynthetic Potential of the Fossil Fuel-Biodesulfurizing Rhodococcus Strain IGTS8. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parte, A.C.; Sardà Carbasse, J.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Reimer, L.C.; Göker, M. List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) Moves to the DSMZ. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 5607–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyte, L.G.; Smits, T.H.M.; Labbé, D.; Witholt, B.; Greer, C.W.; van Beilen, J.B. Gene Cloning and Characterization of Multiple Alkane Hydroxylase Systems in Rhodococcus Strains Q15 and NRRL B-16531. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 5933–5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Engesser, K.-H.; Kim, S.-J. Physiological, Numerical and Molecular Characterization of Alkyl Ether-Utilizing Rhodococci. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1497–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, D.; Washio, K.; Morikawa, M. Identification of Alkane Hydroxylase Genes in Rhodococcus Sp. Strain TMP2 That Degrades a Branched Alkane. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008, 30, 1447–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amouric, A.; Quéméneur, M.; Grossi, V.; Liebgott, P.-P.; Auria, R.; Casalot, L. Identification of Different Alkane Hydroxylase Systems in Rhodococcus Ruber Strain SP2B, an Hexane-Degrading Actinomycete. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 108, 1903–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Liang, Y.; Hong, S.; Wang, G.; You, J.; Xue, Y.; Ma, Y. Degradation of Long-Chain n-Alkanes by a Novel Thermal-Tolerant Rhodococcus Strain. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukliarevich, H.A.; Gurinovich, A.S.; Filonov, A.E.; Titok, M.A. Molecular Genetic and Functional Analysis of the Genes Encoding Alkane 1-Monooxygenase Synthesis in Members of the Genus Rhodococcus. Microbiology 2023, 92, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanklin, J.; Whittle, E.; Fox, B.G. Eight Histidine Residues Are Catalytically Essential in a Membrane-Associated Iron Enzyme, Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase, and Are Conserved in Alkane Hydroxylase and Xylene Monooxygenase. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 12787–12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloos, K.; Munch, J.C.; Schloter, M. A New Method for the Detection of Alkane-Monooxygenase Homologous Genes (AlkB) in Soils Based on PCR-Hybridization. J. Microbiol. Methods 2006, 66, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenibo, E.O.; Selvarajan, R.; Abia, A.L.K.; Matambo, T. Medium-Chain Alkane Biodegradation and Its Link to Some Unifying Attributes of alkB Genes Diversity. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Táncsics, A.; Benedek, T.; Szoboszlay, S.; Veres, P.G.; Farkas, M.; Máthé, I.; Márialigeti, K.; Kukolya, J.; Lányi, S.; Kriszt, B. The Detection and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Alkane 1-Monooxygenase Gene of Members of the Genus Rhodococcus. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaouadi, S.; Mougou, A.H.; Wu, C.J.; Gleason, M.L.; Rhouma, A. Sequence Analysis of 16S RDNA, GyrB and AlkB Genes of Plant-Associated Rhodococcus Species from Tunisia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 6491–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnikova, M.S.; Titok, M.A. Molecular Genetic Markers for Identification of Rhodococcus erythropolis and Rhodococcus qingshengii. Microbiology 2020, 89, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beilen, J.B.; Wubbolts, M.G.; Witholt, B. Genetics of Alkane Oxidation by Pseudomonas Oleovorans. Biodegradation 1994, 5, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.-L.; Nie, Y.; Wang, M.; Xiong, G.; Wang, Y.-P.; Maser, E.; Wu, X.-L. Regulation of Alkane Degradation Pathway by a TetR Family Repressor via an Autoregulation Positive Feedback Mechanism in a Gram-Positive Dietzia Bacterium. Mol. Microbiol. 2016, 99, 338–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Guo, G.; McSweeney, S.M.; Shanklin, J.; Liu, Q. Structural Basis for Enzymatic Terminal C–H Bond Functionalization of Alkanes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beilen, J.B.; Smits, T.H.M.; Roos, F.F.; Brunner, T.; Balada, S.B.; Röthlisberger, M.; Witholt, B. Identification of an Amino Acid Position That Determines the Substrate Range of Integral Membrane Alkane Hydroxylases. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampolli, J.; Collina, E.; Lasagni, M.; Di Gennaro, P. Biodegradation of Variable-Chain-Length n-Alkanes in Rhodococcus Opacus R7 and the Involvement of an Alkane Hydroxylase System in the Metabolism. AMB Express 2014, 4, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Hong, S.; Xue, Y.; Ma, Y. Functional Analysis of Novel AalkB Genes Encoding Long-Chain n-Alkane Hydroxylases in Rhodococcus Sp. Strain CH91. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NCBI Taxonomy | LPSN status of NCBI Taxonomy | GTDB Taxonomy | TSGS Taxonomy |

| Antrihabitans cavernicola | correct name, synonym: Rhodococcus cavernicola |

Rhodococcus_E cavernicola | Rhodococcus cavernicola |

| Prescottella agglutinans | correct name | Rhodococcus agglutinans | Rhodococcus agglutinans |

| Prescottella defluvii | correct name |

Rhodococcus defluvii, Rhodococcus defluvii_A |

Rhodococcus defluvii |

| Prescottella equi | correct name |

Rhodococcus equi, Rhodococcus equi_A |

Rhodococcus equi |

| Prescottella soli | synonym, correct name: Rhodococcus soli | absent | Rhodococcus soli |

| Prescottella subtropica | synonym, correct name: Rhodococcus subtropicus | Rhodococcus subtropicus | Rhodococcus subtropicus |

| Rhodococcoides corynebacterioides | synonym, correct name: Rhodococcus corynebacterioides |

Rhodococcus corynebacterioides, Rhodococcus corynebacterioides_A |

Rhodococcus corynebacterioides |

| Rhodococcoides fascians | synonym, correct name: Rhodococcus fascians |

Rhodococcus fascians, Rhodococcus fascians_E |

Rhodococcus fascians |

| Rhodococcoides kroppenstedtii | synonym, correct name: Rhodococcus kroppenstedtii | Rhodococcus kroppenstedtii | Rhodococcus kroppenstedtii |

| Rhodococcoides kyotonense | synonym, correct name: Rhodococcus kyotonensis |

Rhodococcus kyotonensis, Rhodococcus kyotonensis_B |

Rhodococcus kyotonensis |

| Rhodococcoides trifolii | synonym, correct name: Rhodococcus trifolii |

Rhodococcus trifolii | Rhodococcus trifolii |

| Rhodococcoides yunnanense | synonym, correct name: Rhodococcus yunnanensis |

Rhodococcus yunnanensis | Rhodococcus yunnanensis |

| Rhodococcus antarcticus | correct name | Rhodococcus_D antarcticus | Rhodococcus antarcticus |

| Rhodococcus baikonurensis | synonym, correct name: Rhodococcus erythropolis |

Rhodococcus qingshengii | Rhodococcus baikonurensis |

| Rhodococcus chondri | correct name | absent | Rhodococcus chondri |

| Rhodococcus indonesiensis | correct name | Rhodococcus sp030360185 | Rhodococcus indonesiensis |

| Rhodococcus olei | correct name | absent | Rhodococcus olei |

| Rhodococcus qingshengii | synonym, correct name: Rhodococcus erythropolis |

Rhodococcus qingshengii, Rhodococcus qingshengii_B |

Rhodococcus qingshengii |

| Rhodococcus sovatensis | correct name | absent | absent |

| Rhodococcus tibetensis | not validly published | Rhodococcus sp024438035 | Rhodococcus tibetensis |

| Suggested namea | Genomic context if available | Protein GenBank ID | Strain | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlkB1 | AlkB, RubA, RubA, RubB, AlkU | CAB51053.2 | R. erythropolis NRRL B-16531 | [96] |

| AlkB2 | cationic transporter†, AlkB, RubA, RubA, AlkU† | CAC37038.1 | ||

| AlkB3 | (putative) exported protein†, alkB | CAC40953.1 | ||

| AlkB4 | AlkB, glutamil t-RNA synthetase | CAC40954.1 | ||

| AlkB1 | AlkB, AubA, RubA, RubB, AlkU | AAK97448.1 | Rhodococcus sp. Q15 | |

| AlkB2 | cationic transporter†, AlkB, RubA, RubA, AlkU | AAK97454.1 | ||

| AlkB3 | — | AAK97446.1 | ||

| AlkB4 | — | AAK97447.1 | ||

| AlkB5 | — | ABI13998.1† | R. rhodochrous 116 | [97] |

| AlkB7 (AlkB1) | — | ABI13999.1† | Rhodococcus sp. DEE5151 | |

| AlkB5 | — | ABI14000.1† | Rhodococcus sp. DEE5301 | |

| AlkB7 (AlkB1) | — | ABI14001.1† | Rhodococcus sp. DEE5311 | |

| AlkB5 | — | ABI14002.1† | Rhodococcus sp. DEE5316 | |

| AlkB6 (AlkB2) | — | ABI14003.1† | Rhodococcus sp. DEOB100 | |

| AlkB7 (AlkB1) | — | ABI14004.1† | Rhodococcus sp. MOB100 | |

| AlkB6 (AlkB2) | — | ABI14005.1† | Rhodococcus sp. MOP100 | |

| AlkB7 (AlkB1) | — | ABI14006.1† | Rhodococcus sp. THF100 | |

| AlkB1 | — | BAG06232.1† | Rhodococcus sp. TMP2 | [98] |

| AlkB2 | — | BAG06233.1† | ||

| AlkB3 | — | BAG06234.1† | ||

| AlkB4 | — | BAG06235.1† | ||

| AlkB5b (AlkB6) | — | BAG06236.1† | ||

| AlkBa (AlkB1) | RubA, RubA, RubB† | ACX30747.1 | R. ruber SP2B | [99] |

| AlkBb (AlkB5) | — | ACX30751.1† | ||

| AlkBa (AlkB1) | — | ACX30755.1 | R. ruber DSM 43338 | |

| AlkBb (AlkB5) | — | ACX30752.1† | ||

| AlkB2 | ManA, AlkB, RubA, RubA, TetR, AhcY | WP_241385946.1 | Rhodococcus sp. CH91 | [100] |

| AlkB new (AlkB5) | aminotransferase, cold-shock protein, AlkB, AbiEi family protein | WP_241384812.1 | ||

| AlkB7 | alpha/beta hydrolase | AMY23060 | Rhodococcus fascians PBTS 2 | [101] |

| AJW41446 | Rhodococcus sp. B7740 | |||

| QII08422 | Rhodococcus fascians A25f | |||

| QIH99153 | Rhodococcus fascians A2ld2 | |||

| AlkB8 (AlkB0) | ManA, AlkB, AhcY | AYJ49258 | Rhodococcus sp. PI Y | |

| AMY51400 | Rhodococcus fascians D188 | |||

| AMY24665 | Rhodococcus fascians PBTS 2 | |||

| AJW39705 | Rhodococcus sp. B7740 | |||

| QII00755, QII06794c | Rhodococcus fascians A2ld2, Rhodococcus fascians A25f |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).